Surgical complications

Patient safety remains one of the most prominent issues in health policy and public debate. Evidence suggests that over 15% of hospital expenditure and activity in OECD countries can be attributed to treating safety failures, many of which are preventable (OECD, 2017a; OECD, 2017b). In the United States an estimated USD 28 billion has been saved between 2010 and 2015 by systematically improving safety (AHRQ, 2016).

Robust comparison of performance with peers is fundamental to securing improvement. Two types of patient safety event can be distinguished for this purpose: sentinel or “never” events that should never occur such as failure to remove surgical foreign bodies at the end of a procedure; and adverse events, such as post-operative sepsis, which can never be fully avoided given the high-risk nature of some procedures, although increased incidence at an aggregate level may indicate a systemic failing.

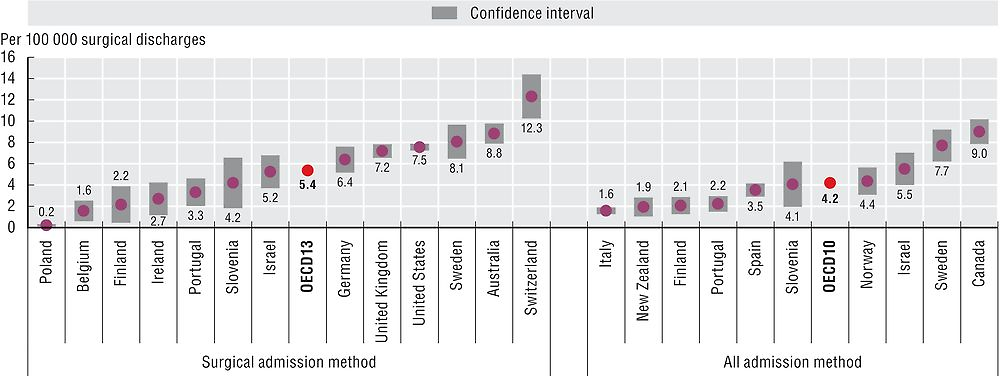

Figure 6.24 illustrates a never event, rates of foreign body left in during procedure. The most common risk factors for this never event are emergencies, unplanned changes in procedure, patient obesity and changes in the surgical team; preventive measures include counting instruments, methodical wound exploration and effective communication among the surgical team.

Note: Given very low incidence of events, 95% confidence intervals have been calculated for all countries as represented by grey areas.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017.

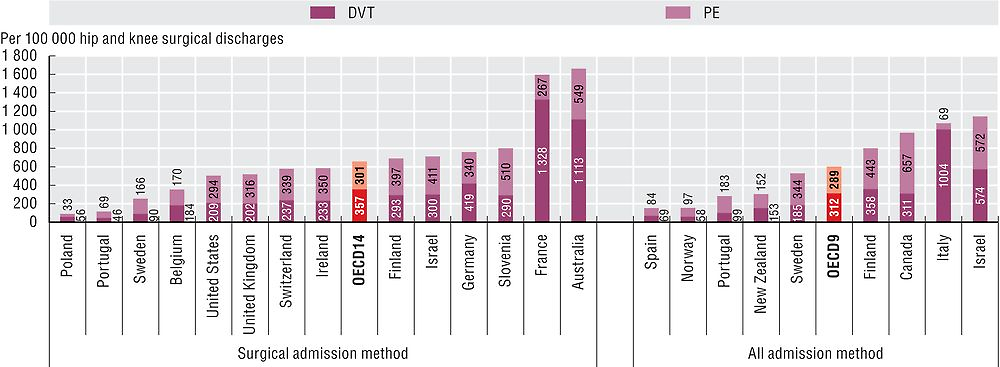

Figure 6.25 shows rates for two related adverse events, pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) after hip or knee replacement surgery. PE and DVT cause unnecessary pain and in some cases death, but can be prevented by anticoagulants and other measures before, during and after surgery. Large variations in rates are observed, with nearly a 20-fold variation in DVT. Variations in DVT rates may be influenced by differences in diagnostic practices across countries, with evidence that routine ultrasound screening can significantly increase the detection of DVT (Kodadek, 2016).

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017.

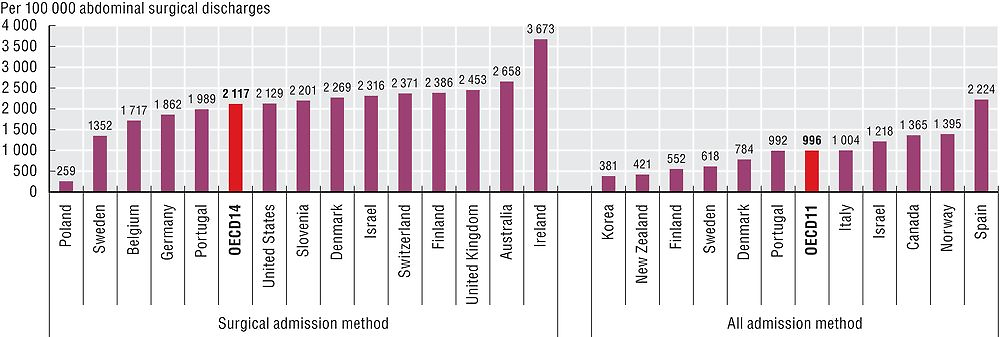

Figure 6.26 shows rates for another adverse event, sepsis after abdominal surgery. Likewise, sepsis after surgery, which may lead to organ failure and death, can in many cases be prevented by prophylactic antibiotics, sterile surgical techniques and good postoperative care.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2017.

The left panel of Figures 6.24, Figure 6.25 and 6.26 shows the rate of the three respective postoperative complications based on the “surgical admission”, the hospital admission where the surgery took place. The right panel of these figures shows rates based on not only the surgical admission but all subsequent re-admissions to hospital within 30 days, whether at the same hospital or in another hospital.

Caution is needed in interpreting the extent to which these indicators accurately reflect international differences in patient safety rather than differences in the way that countries report, code and calculate rates of adverse events (see “Definition and comparability” box).

Two methods of calculating surgical complications are presented. The surgical admission-based method uses unlinked data to calculate the number of discharges with ICD codes for the complication in any secondary diagnosis field, divided by the total number of discharges for patients aged 15 and older. The all admission-based method uses linked data to extend beyond the surgical admission to include all subsequent related re-admissions to any hospital within 30 days. While the all admission-based method is considered more robust and is less affected by variations in the length of stay and hospital transfer practices, it requires a unique patient identifier and linked data which is not available in all countries. While the all admission-based method strengthens identification of valid complications, the impact on indicator rates is unclear given only one admission per patient is counted when multiple qualifying admissions are identified.

A fundamental challenge in international comparison of patient safety indicators centres on differences in the underlying data. Variations in how countries record diagnoses and procedures and define hospital admissions can affect calculation of rates. In some cases, higher adverse event rates may signal more developed patient safety monitoring systems and a stronger patient safety culture rather than worse care. There is a need for greater consistency in reporting of patient safety across countries and significant scope exists for improved data capture within national patient safety programmes.

References

AHRQ (2016), “National Scorecard on Rates of Hospital-Acquired Conditions 2010 to 2015: Interim Data From National Efforts to Make Health Care Safer”, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/quality-patientsafety/pfp/2015-natlscorecard-hac-rates.pdf, accessed 26.01.2017.

Kodadek, L.M. and E.R. Haut (2016), “Screening and Diagnosis of VTE: The More You Look, The More You Find?”, Current Trauma Reports, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 29–34.

OECD (2017a), Tackling Wasteful Spending on Health, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264266414-en.

OECD (2017b), The Economics of Patient Safety: Strengthening a Value-Based Approach to Reducing Patient Harm at a National Level Publishing, OECD, Paris, available at http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/The-economics-of-patient-safety-March-2017.pdf.