Strategic public procurement

Governments continue to use public procurement to pursue secondary policy objectives while delivering goods and services necessary to accomplish their missions in a timely, economical and efficient manner. The high relevance of public procurement for economic outcomes and sound public governance, as implied by its large volume, makes governments use public procurement as a strategic policy lever for achieving additional policy goals, which aim to address environmental, economic and social challenges according to national priorities.

Environmental considerations continue to be the key policy objectives that are addressed through public procurement. Almost all OECD countries surveyed (29 countries) support green public procurement through various policies and strategies at the central level and those developed by specific procuring entities. In comparison to 2014, two more countries (Estonia and the Slovak Republic) have developed policies to support green public procurement. Central policies are often accompanied by detailed guidance on how to implement them, such as those developed by the Ministry of Environment in Estonia and by the Environmental Protection Agency in Ireland. Specific legislative provisions also require countries to take into consideration energy efficiency, environmental considerations and life-cycle costs in procurement.

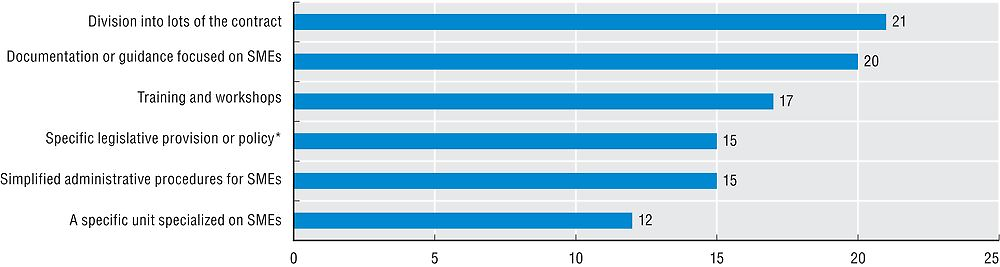

Public procurement policies and strategies are increasingly used in OECD countries to incorporate economic policies, in particular, fostering participation and development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). While division of the contract into lots is the most widely used approach to support SMEs in the majority of the OECD countries (21 countries), more than half of them, such as Australia, Israel and Korea, also use guidelines (20 countries), and training and workshops (17 countries) to support SMEs in public procurement. In particular, member countries of the European Union (EU) reinforced the strategic use of public procurement through the transposition of the 2014 public procurement EU directives. The transposition of the directives facilitated SMEs’ access to public procurement through more simplified and flexible procedures and by encouraging partitioning contracts into lots.

As one of the main demand-side innovation policies, public procurement is used in the majority of OECD countries (24 countries) to support innovative goods and services, except for Chile, Greece, Iceland, Israel, Japan and the Slovak Republic. Various measures exist to support strategic innovation procurement. They range from legal instruments and more comprehensive government programmes to non-legal instruments, such as guidance, which is the most widely used approach (16 countries). Less often, specific legislative provisions and policies stipulate preferences for innovative goods and services through set-aside and bid preferences, such as in Austria, Latvia and Turkey, and sometimes even preferential treatments including waiving fees and quotas for innovative firms, such as in Mexico and Spain. There are also government programmes that support pre-commercial procurement to help late-stage innovative products and services to enter the market. Examples include Canada’s Build in Canada Innovation Program and Denmark’s Market Development Fund.

Data were collected through the 2016 OECD Survey on Public Procurement, which focused on strategic public procurement, e-procurement, central purchasing bodies, public procurement at sub-central levels and infrastructure projects. A total of 30 OECD countries responded to the survey, as well as 3 OECD accession countries (Colombia, Costa Rica and Lithuania) and 1 OECD key partner country, India. Respondents to the survey were country delegates responsible for procurement policies at the central government level and senior officials in central purchasing bodies.

Green public procurement is defined by the European Commission as “a process whereby public authorities seek to procure goods, services and works with a reduced environmental impact throughout their life cycle when compared to goods, services and works with the same primary function that would otherwise be procured.”

Strategic use of public procurement for innovation is defined as any kind of public procurement practice that is intended to stimulate innovation through research and development and the market uptake of innovative products and services.

Further reading

OECD (2017), Public Procurement for Innovation: Good Practices and Strategies, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2015a), “Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement”, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/OECD-Recommendation-on-Public-Procurement.pdf.

OECD (2015b), “Procurement - Green procurement”, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/green/.

Figure notes

9.5: Australia’s ICT Sustainability Plan expired in June 2015 but Australia’s Commonwealth Procurement Rules require that officials consider the relevant financial and non-financial costs of each procurement, including but not limited to environmental sustainability of the proposed goods and services. In Norway, the first national action plan, Environmental and Social Responsibility in Public Procurement, was adopted in 2007 and then rescinded.

9.6: Specific legislative provisions include set-aside and bid preferences.

Source: OECD (2016), Survey on Public Procurement, OECD, Paris.