Co-ordination mechanisms for implementing integrity policies

Public integrity systems are composed of a multitude of actors responsible for various specific policy areas. Furthermore, these actors span both central and sub-national (i.e. regional and local) levels of government. Mechanisms for vertical and horizontal inter-institutional co-ordination are therefore crucial to ensure effective implementation throughout the whole of government, as well as to prevent duplication or fragmentation which can lead to waste of public resources and/or ineffective policies.

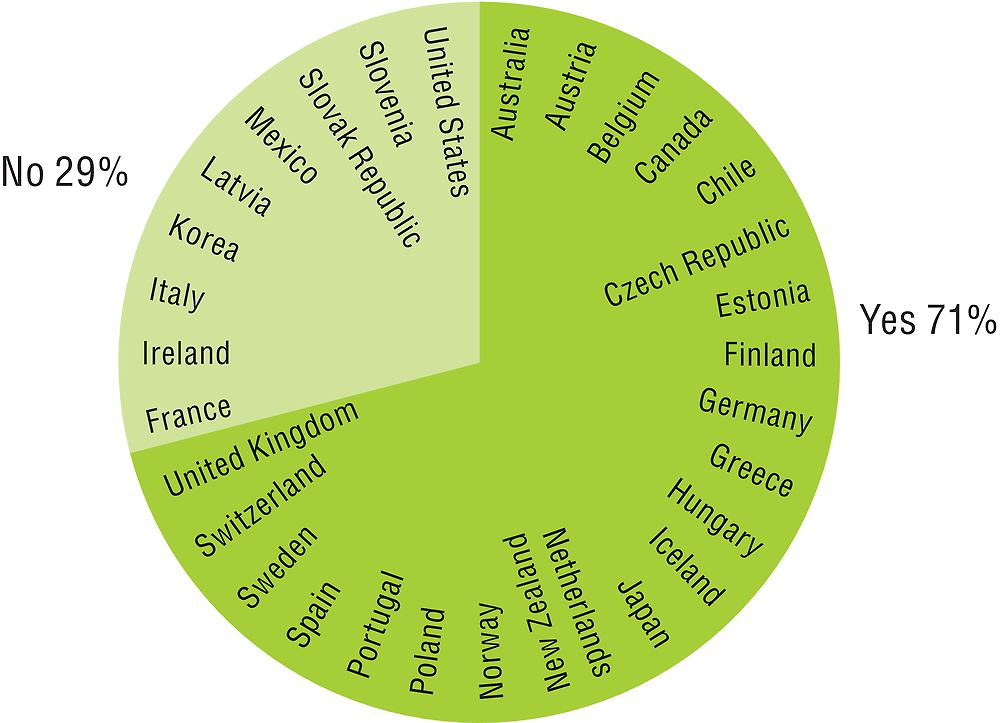

Many integrity systems are decentralised. In 71% of countries (22 countries), state or local governments are considered autonomous and able to determine their own integrity policies. This includes many (but not all) OECD federal and quasi-federal countries such as Belgium, Spain and Switzerland. Indeed, the notion of local integrity systems makes sense in many countries, given that integrity risks can vary considerably across territories and administrative jurisdictions, and one-size-fits all approaches would likely be ineffective. For instance, state and local governments may have comparatively greater competencies for the delivery of public services, resulting in higher interactions with citizens and firms, which can create opportunities for corruption. They may also have higher levels of at-risk expenditure such as social spending or public procurement contracts, which require additional measures of control. For instance, in 2015 in the OECD, 63% of public procurement spending occurred at sub-central level.

Even where state and local governments are autonomous in the design and implementation of integrity policies, they are often supported by the central level through co-ordination mechanisms. Indeed, only few countries (3 countries) do not have in place any co-ordination mechanism. The most common forms of support are guidance by a central government integrity body (9 countries), regular meetings in a specific integrity committee or commission (11 countries), and involvement of state and local governments in the design of the policies themselves (7 countries).

Other countries have adopted more formal approaches to co-ordination. In Estonia, Japan, Mexico and New Zealand, for instance, legal agreements or contracts between central and sub-national governments are utilised. Unlike other methods, such agreements may bind actors to comply with agreed-upon objectives and initiatives. Overall, however, few countries reported adopting many co-ordination tools simultaneously. This could be reflective of such commonly cited challenges as high fluctuation of staff, high administrative burdens associated with co-ordination, and a fear by subnational levels that co-ordination would encroach on their decision-making powers.

Co-ordination is similarly important across line ministries and departments to mainstream policies across policy sectors and ensure compliance. Normative requirements are therefore the most common tool (29 countries), followed by ongoing guidance by a central government body or unit (22 countries). Many countries (17 countries) also require that line ministries have their own integrity units in place. This greatly facilitates co-ordination since it identifies a concrete focal point that can be held accountable for results. In Austria, Canada and Germany for example, ethics officers and contact points in line ministries have established networks for exchanging good practices and seeking advice.

Data were collected through the OECD 2016 Survey on Public Sector Integrity from 31 OECD countries and 6 non OECD countries. Survey respondents were public officials responsible for integrity policies in their respective central/federal governments.

Central government is often called federal or national government, depending on the country. For the purposes of this survey, the central government consists of the institutional units controlled and financed at the central level plus those non-profit institutions that are controlled and mainly financed by central government. For purposes of the survey, only the executive branch of central government was considered.

Sub-national governments refer to state (regional) or local (municipal) government administrations. For the purposes of the survey, only the executive branch was considered.

Further reading

OECD (2017),Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, OECD, Paris.

OECD (2017), “OECD Integrity Review of Peru”, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2017), “OECD Integrity Review of Mexico”, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Figure notes

Data on Argentina, Brazil and Peru were included on an ad-hoc basis.

7.2: In France, autonomous bodies, under national legislation, are in charge of integrity policies at both national and sub-national level. Within the legally defined framework, sub-national bodies are furthermore free to independently adopt their own implementation mechanisms.

7.3: In Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway and the U.S., central and sub-national bodies engage in informal co-ordination on many of the subject specific elements of an integrity system.

Source: OECD (2016), Survey on Public Sector Integrity, OECD, Paris.