Chapter 2. Fostering markets for SME finance: Matching business and investor needs

This chapter focuses on key demand- and supply-side barriers that currently limit SMEs’ access to non-bank finance instruments. It reviews recent trends in policy measures to support the development of such alternative finance instruments, including SME investor-readiness and financial literacy programmes, as well as ways to incentivise institutional investors, retail investors and other potential market participants to enter SME equity markets, with the objective to identify good practices and policy recommendations.

Introduction

The financial crisis had a profound impact on the availability of bank credit. Lending to SMEs often declined dramatically in the years following the crisis, and there continues to be a financing shortfall in many countries. Although this slump was in part caused by a decline in the demand for credit, banks have also become more reluctant to lend, and thus loans have been more difficult to obtain for SMEs and entrepreneurs.

The effects of the crisis and its aftermath were especially pronounced for SMEs for several reasons. First, SMEs are much more dependent on bank lending than large firms, so a decline in the availability of bank loans is much more likely to impact their investment and growth prospects. This situation has been particularly damaging to European SMEs that rely more on bank finance than their US counterparts, where non-bank credit channels have considerably mitigated the impact of the drought of straight bank debt (Véron, 2013). Second, credit to entrepreneurs and SMEs is likely to be disproportionately impacted by the subsequent financial reforms. Among SMEs, start-ups, micro-enterprises and firms with innovative, but unproven business models already faced significant barriers to accessing finance before the crisis, and thus continue to be the most likely to be cut off from external financing given their risk profile. Third, SMEs’ profitability suffered under the worsening economic climate. This not only compounded their difficulties in obtaining bank lending, but also made it more difficult to replace external sources of finance with internal ones.

Moreover, traditional bank lending may not always be the most appropriate form of finance for certain SMEs and entrepreneurs. In particular, debt financing is often ill-suited to the needs of start-ups, highly innovative or fast-growing firms. Although these firms form only a small minority of all SMEs, they account for a significant share of jobs created and are key players in achieving inclusive economic growth, and in contributing to innovation. Given the higher risk-return profile of these enterprises, their growth depends more on well-functioning capital markets, and less on the conditions in the credit market. Similar equity gaps also exist for firms undergoing an important transition, such as a change in ownership, a restructuring of activities, entry into foreign markets, and so on. Other finance instruments, often equity-based, may therefore be more suitable for these firms.

Challenges in developing non-bank finance instruments for SMEs

The scoreboard data illustrate that, although financial instruments other than bank lending have been gaining traction in some countries, they have not been able to compensate for the credit shortfalls observed in many countries. Likewise, the cyclicality of bank finance has proven particularly problematic in countries with less developed financial markets. There is evidence that countries with bank-oriented systems face greater impacts of a crisis than those with a market-oriented financial structure (Gambacorta et al., 2014). This, in turn, suggests that SMEs which are less reliant on bank finance are less likely to be vulnerable to cyclical effects.

At the same time, there is clear potential to further mobilise financial markets as a source of finance for SMEs. Although many of the obstacles to the development and uptake of non-bank finance instruments are common for most of the instruments across the risk-return spectrum, they are most acute for high-risk, high-return equity-type instruments on the right of Table 2.1.

An additional reason to focus primarily on high-risk, high-return instruments is that these instruments mainly cater to innovative and high-potential SMEs and start-ups, where traditional finance gaps are most acute. This firm segment is often not well served by the banking sector, because of its riskiness and opacity, and thus relies more on the development of alternative financing instruments. A recently published report by the British Business Bank (2016) highlights that both scale-up and established SMEs are more likely to see their new loan application approved (with success rates around 60%), while start-ups are more likely to be unsuccessful. When considering new overdrafts applications, a similar trend is evident, where scale-up and established SMEs have proven to be more successful.

The difficulties in developing alternative instruments stem to a significant extent from demand-side challenges, including the lack of financial knowledge of many entrepreneurs and business owners, who are sometimes unaware of the existence of alternatives to bank lending and, even if they are, are very often unable or unwilling to comply with the requirements of professional investors. Insufficient financial knowledge also often prevents SMEs from seeking out the instruments which are most suited to their needs. Unfavourable tax treatment of some of these alternatives may also be an obstacle to their expanded use. On the supply side, despite many government initiatives to develop the use of equity-type instruments for SMEs, (institutional) investors remain hesitant to invest in small firms because of large information asymmetries, a scarcity of transparent credit data, regulatory obstacles such as the asymmetric treatment of equity and debt financing, as well as insufficient investment opportunities.

The rationale for public policy to take an active role in removing barriers to the development of alternative finance instruments for SMEs is thus two-fold. First, the financing gap faced by SMEs has been widely identified as stemming from a market failure, resulting in economic inefficiencies. A second argument for intervention relates to the positive spill-over effects that the development of alternative finance instruments generates for the broader economy, especially those targeting fast-growing firms that contribute disproportionately to job growth. It is against this backdrop that many governments have stepped in to make alternative financial instruments more available to small businesses.

The role of public policy in fostering markets for SME finance

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, policy attention focussed mainly on sustaining bank finance, most often by expanding and/ or improving existing credit guarantee schemes or developing new ones. Although these initiatives provided necessary breathing room for many SMEs in need of finance, they also contributed to perpetuating SME over-reliance on straight debt. While policies to facilitate bank lending have often remained in place and are in many instances now being modified in line with evolving needs, an additional recent policy shift towards alternative finance instruments can be discerned. Indeed, over the last few years, many new initiatives to foster sources of finance other than straight debt have been introduced, notably with respect to equity-type instruments, often alongside a focus on innovative and high-potential SMEs. These initiatives range from introducing tax incentives for investors in SME markets, the implementation of more effective regulation (of particular note in this respect are the recently adopted regulatory frameworks for crowdfunding activities in several countries), to the exploration of public-private partnerships for equity investments within the capital market. Box 2.1 explores the potential of capital markets to finance SMEs in greater detail.

The past three decades have seen a shift in financing from the banking system to the capital market. However, unlike larger companies, SMEs continue to turn to banks, which usually remain the least expensive form of funding for these types of firms.

Banks face losses when borrowers cannot repay loans, but derive few additional benefits when the borrower is very profitable. Therefore, banks will often pass up potentially lucrative but risky proposals, and prefer companies with steady cash flows and collateral. The situation is different when the firm embarks on an innovative project or structural transformation, such as increasing the scale of operations, introducing new products or expanding geographically. In those circumstances, a possible solution for an SME is to forge a partnership with a capital market intermediary that specialises in analysing and accepting the risks of corporate transformation. The capital market intermediary can structure a financing vehicle that distributes risk and reward between the owners of the firm and outside investors.

When discussing capital markets, a basic distinction must be made between public and private markets. A private capital market is open only to certain categories of investors, designated as “qualified”, i.e. exempt from the full range of investor protection laws and regulations. Private markets are frequently less liquid and transparent than the public markets and companies are usually not subject to public disclosure requirements, meaning that information may be shared on a confidential basis among “insiders” such as owners, managers, financial intermediaries and investors. Investors in the private capital market, who are considered professional or sophisticated, waive the full range of investor protection regulation in order to invest in restricted market niches.

The private capital market instrument that most closely resembles a bank credit is the private debt fund (“alternative lender”), in which institutional investors create a fund that operates outside the banking system and offers debt financing for SMEs. The private debt market has expanded steadily in recent years, with no visible slackening during the crisis. The largest single market is the United States with around 60% of the world total, but the fastest growth is occurring in Europe, whose share since 2010 has grown from 10% of the world market to 30%. Private equity represents the second component of the private capital market and a well-established vehicle for financing potential high growth SMEs. In both, private equity and private debt, the level of “dry powder”, i.e. funds that have been committed by investors but not yet invested, is near all-time highs. In its current state, the private capital market may thus have huge potential resources available for further investment (see Table 2.2).

The past three decades have seen a shift in financing from the banking system to the capital market. However, unlike larger companies, SMEs continue to turn to banks, which usually remain the least expensive form of funding for these types of firms.

Banks face losses when borrowers cannot repay loans, but derive few additional benefits when the borrower is very profitable. Therefore, banks will often pass up potentially lucrative but risky proposals, and prefer companies with steady cash flows and collateral. The situation is different when the firm embarks on an innovative project or structural transformation, such as increasing the scale of operations, introducing new products or expanding geographically. In those circumstances, a possible solution for an SME is to forge a partnership with a capital market intermediary that specialises in analysing and accepting the risks of corporate transformation. The capital market intermediary can structure a financing vehicle that distributes risk and reward between the owners of the firm and outside investors.

When discussing capital markets, a basic distinction must be made between public and private markets. A private capital market is open only to certain categories of investors, designated as “qualified”, i.e. exempt from the full range of investor protection laws and regulations. Private markets are frequently less liquid and transparent than the public markets and companies are usually not subject to public disclosure requirements, meaning that information may be shared on a confidential basis among “insiders” such as owners, managers, financial intermediaries and investors. Investors in the private capital market, who are considered professional or sophisticated, waive the full range of investor protection regulation in order to invest in restricted market niches.

The private capital market instrument that most closely resembles a bank credit is the private debt fund (“alternative lender”), in which institutional investors create a fund that operates outside the banking system and offers debt financing for SMEs. private equity and private debt, the level of “dry powder”, i.e. funds that have been committed by investors but not yet invested, is near all-time highs. In its current state, the private capital market may thus have huge potential resources available for further investment (see Table 2.2).The private debt market has expanded steadily in recent years, with no visible slackening during the crisis. The largest single market is the United States with around 60% of the world total, but the fastest growth is occurring in Europe, whose share since 2010 has grown from 10% of the world market to 30%. Private equity represents the second component of the private capital market and a well-established vehicle for financing potential high growth SMEs. In both,

On the other hand, the public capital market is subject to the full set of regulations prescribed by an officially designated supervisory authority concerning disclosure and other investor protection requirements. Within the public capital market, the main way in which retail investors can invest in SMEs is through the use of collective investment vehicles.

Collective investment has become the main channel though which individuals participate in this market segment in OECD countries. Collective investment vehicles are legally recognised investment instruments that assemble portfolios of claims on SMEs (debt or equity) for investment by retail investors, i.e. persons who do not qualify as “high net worth individuals” and may only purchase publicly offered securities. These instruments enable individual investors to take advantage of opportunities available in the public capital market, even if they lack the requisite skills to invest profitably and cannot afford sufficiently diversified portfolios or efficiently execute investment strategies. Collective investment vehicles that specialise in financing SMEs are found in a limited number of OECD countries. In particular in the United States, assets of Business Development Companies (BDCs) have tripled in size in the past decade, with notable growth since the crisis, and have become a significant feature of the SME financing landscape.

Although the data remain patchy, available evidence suggests that capital markets are already making a contribution to the financing of SMEs in some OECD countries and have the potential to contribute to reducing the SME financing gap, particularly for start-ups, fast-growing ventures or established firms which undergo a major transition such as a change in ownership. The private capital market offers advantages to SMEs looking for finance, mainly through its flexible form and conditions, usually complementing rather than replacing bank financing. However, the opacity and illiquidity in the SME segment, the high costs to SMEs of compliance with investor protection regulations, and the costs to investors of monitoring SMEs, represent a serious obstacle to SMEs access to public markets. Against this backdrop, collective investment vehicles may represent a suitable instrument to facilitate SME participation in this market segment.

Source: OECD (forthcoming), “Alternative Financing Instruments for SMEs and Entrepreneurs: The Case of Capital Market Finance”.

Transnational initiatives have also been undertaken to support the development of a diverse range of financing options for SMEs (see Box 2.2).

Such developments demonstrate that SMEs remain high on the political agenda. The OECD is currently supporting governments in their implementation of the G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing, including the development of effective approaches to implement the Principles in individual countries, and monitor their implementation. The sections below provide an overview of the main types of relevant policy initiatives, many of which are in line with the G20/OECD High Level Principles on SME Financing.

On a transnational level, the Capital Markets Union (CMU) represents a pan-European approach with the aim of supporting the development of alternative sources of finance complementary to bank-financing, and to thereby better connect SMEs with a wider range of funding sources at different stages of their development, as well as to ensure that capital can move freely across borders in the Single Market.

On 30 September 2015, the Commission adopted an Action Plan on a CMU. The Action Plan sets out a programme of 33 actions and related measures, which aim to establish the building blocks of an integrated capital market in the European Union by 2019. This includes in particular the launch of a package of measures to support venture capital and equity financing and promote innovative forms of business financing, such as crowd-funding, private placements, and loan-originating funds in the EU. In addition, the Plan comprises measures for catalysing private investment using EU resources through pan-European funds-of-funds, regulatory reform, and the promotion of best practice on tax incentives.

Source: European Commission.

Designing an effective regulatory framework

The design and implementation of effective regulation that supports a range of financing instruments for SMEs, while ensuring financial stability and investor protection, is a key enabler to the greater use of alternative finance techniques and frequently identified as an important obstacle by entrepreneurs and SMEs (OECD, 2015a). Against this backdrop, several countries have recently overhauled their regulation to allow for the further expansion of alternative financing instruments. In 2012, for instance, Turkey adopted a mechanism to license business angels in order to professionalise the business angel industry. Furthermore, it makes business angel investments an institutionalised and trustworthy financial market and eligible for state support, mainly under the form of tax deductions for angel investors. In March 2014, Chile launched a set of measures titled the “Agenda of Productivity, Innovation and Growth.” One of the key initiatives on the agenda is a modification of the existing regulation related to financial instruments with the aim of increasing access of new alternative instruments of finance for SMEs and entrepreneurs.

A Belgian law promulgated in 2013 (Loi relative à diverses dispositions concernant le financement des petites et moyennes entreprises) relates to credit contracts and the obligation for possible credit providers to provide sufficient and transparent advice on what kind of credit might be most suitable for a certain SME (and if the information is not well provided, the SME can later on reverse the contract). The law also includes the provision that most firms can cancel their credit contract at any time, with a maximum fine of six months interest. Although the law is limited to credit contracts, it is an example of how a government can try to make the financing market more transparent for SMEs via regulation, which may also be applicable in the context of alternative financing instruments.

Another example of recent progress is the creation of a number of growth markets dedicated to financing and promoting small and midsized stocks. These include London’s Alternative Investment (AIM) market, AIM Italia, NYSE Euronext’s Enternext, the Frankfurt Stock Exchange’s Entry market, Nasdaq’s First North serving the Nordic markets, Spain’s Alternative Stock Market and Turkey’s Emerging Companies Market of Borsa Istanbul. Across France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom, over 1 500 companies are listed on growth exchanges or multilateral trading facilities, representing nearly EUR 126 billion (AFME, 2015).

The Chilean Commodities Exchange (Bolsa de Productos de Chile – BPC) is a demutualised entity regulated by Law and supervised by the Securities and Insurance Commission (SVS). Its purpose is to offer public auction platforms for the trading of commodities, contracts, receivables and their derivatives. Through this initiative, Chile managed to develop a public market for receivables for the exchange of receivables issued by certain big (and certified) buyers to their suppliers which essentially works like an equity market. SMEs make use of this market to obtain cash flow advances in exchange for these receivables (just like for factoring). In fact, factoring companies themselves sell a portfolio of receivables in this market.

The establishment of Bolsa de Productos has been made possible because of a recent law (Law 19.220), which provides unique legal safeguards for investors that acquire invoices through the exchange, protecting them from any encumbrance that may affect an invoice. The invoices remain under legal and material custody of the BPC from the beginning of the operation to the payment by the debtor of the invoice, thus assuring that they are out of reach from potential creditors. In 2007, the law was modified so as to include invoices among the products that BPC can operate.

Advantages of this mechanism include, inter alia, the concentration of payments into one single entity, without limiting suppliers’ access to the market. BPC thus supports suppliers growth, allowing them to finance their working capital at buyers risk related rates and also allows them to get better, tax-free, faster and cheaper rates for their working capital. This ultimately results in an extension of payment terms of payable accounts (DPO, days of payment outstanding) without the use of banking credit lines.

Bolsa de Productos began trading in 2005 and has operated to date over USD 6 billion in assets, growing by a compounded annual rate of 40% in receivables trading from 2012 to 2015. In 2015, BPC traded around USD 900 million, mainly from the mining and agro-industry sector, although most economic sectors are represented, along with different durations, depending on payers’ economic activity. The average monthly discount rate at the exchange was approximately 0.8% (including broker fees), compared to rates over 1% from banking factorings and 1.8% from non-banking factorings. 63% of companies that sold their invoices at the exchange were SMEs. Currently, Bolsa de Productos has 12 operating brokers responsible for the fulfilment of the contracts agreed upon through their intermediation - most of them non-banking institutions.

Source: Bolsa de Productos de Chile (presentation at the OECD and written exchanges).

Tax incentives

A 2015 OECD study on the taxation of SMEs found that many of the examined tax systems included certain features that inadvertently put SMEs at a disadvantage relative to larger enterprises. These features included the asymmetric treatment of profits and losses, as well as higher fixed costs associated with tax and regulatory compliance regimes (OECD, 2015b). A further key issue identified in this study, as well as in other papers, refers to the existing tax bias towards debt over equity, which in combination with other factors such as lower liquidity, affects SMEs more than large enterprises.

The provision of tax incentives, usually via tax deductibility of interest payments, is therefore a widely used instrument to lift barriers for equity investments in SMEs, and several countries have experimented with the introduction of tax deductibility of notional interest paid on equity, so as to level the playing field on the tax treatment of debt and equity financing. Tax incentives are sometimes also directed at the demand side, under the form of support for innovative start-ups, tax deductibility of entrepreneurship training or participation in incubator programmes. According to a survey conducted in 2012 in 32 OECD countries, policy interventions in this area have generally expanded since the financial crisis (OECD, 2013c).

Turkey has recently adapted its tax regulation to make equity investments more attractive for businesses. Since July 2015, businesses can deduct cash capital increases from the companies’ paid or issued capital amounts, or from the cash amount of the paid capital of the newly established capital companies. In addition, licensed business angel investors can deduct 75% of the capital they invest in innovative and high growth SMEs whose shares are not traded at the stock market from their annual income tax base. The 75% deduction rate will be increased to 100% for those investors investing in SMEs whose projects were supported by the Ministry of Science, Industry and Technology, the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBITAK) and the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Organisation (KOSGEB) in the last five years.

In 2010, the Portuguese Government put in place a tax relief for business angels, allowing them to deduct 20% of the amount they invest in start-ups, with a cap of 15% of the business angel income tax amount. There are some restrictions in terms of start-up activities (real estate, financial companies are not eligible); investment in start-ups must be in equity, not loans; the maximum investment period is ten years; and angels cannot invest in relatives’ (family) companies. Similarly, in Sweden, a tax break for private business angel investors was launched in December 2013. The tax break allows for a tax relief on the capital income tax up to 15% of the investment. Private individuals purchasing shares in a small company can deduct up to 50% of the investment from the capital income tax owed, up to a yearly limit of SEK 650 000 and to a total maximum of SEK 1.3 million. A number of different conditions have to be met by the target firm, the investor and the investment for the deduction to be available, such as a minimum holding period of five years. Similar tax incentives exist in number of further countries (OECD, 2016).

In 2015, the Australian Government announced the National Innovation and Science Agenda which includes a suite of tax and business incentives, including tax concessions for early stage investors in innovative start-ups. Eligible investors can claim a 20% non-refundable, carry forward tax offset, capped at AUD 200 000 per investor per year, as well as a capital gains tax exemption, provided investments are held for at least 12 months. Another new measure is the introduction of a 10% non-refundable tax offset for capital invested in new Early Stage Venture Capital Limited Partnerships (ESVCLPs), and an increase in the cap on committed capital from AUD 100 million to AUD 200 million for new and existing ESVCLPs. Similarly, Spain launched a national tax incentive scheme to encourage direct investment by third parties in small, early stage companies already in 2011. Hereunder, third parties investing in shares of unlisted companies are exempt from capital gains. In addition, registered venture capital companies only have to pay a 1% corporate income tax in Spain (OECD, 2015b).

A notional interest deduction scheme was introduced in Belgium in 2005 at the interest rate on ten year government bonds. Italy launched a similar regime in March 2012, allowing an income deduction for equity investments made after 2010 at a fixed rate of 3%. Brazil and Latvia have similar schemes in place (de Mooij and Devereux, 2011). Evidence from Belgium, where the tax deductibility scheme has been in place for a decade now, suggests that this tax reform has had a pronounced impact on the debt-capital structure, as the average debt ratio for Belgian SMEs declined from 0.61% in 2005 to 0.57% in 2008 (Kestens et al., 2012). A significant downside of this tax scheme, and similar ones in other countries, is its cost in terms of foregone earnings: its budgetary impact is estimated to have increased from EUR 1.8 billion in 2006 to EUR 6.2 billion in 2011. Although this estimate does not take into account the likely positive effects on economic activities, the costs of tax deductibility schemes for equity investments seem to be significant and an important deterrent to their wider adoption (Zangari, 2014).

Developing a credit information infrastructure

One of the main difficulties faced by SMEs in accessing financial markets is related to information deficiencies. SMEs are known to be opaque, often lacking audited financial statements or other credible credit data that would allow investors to reliably assess the risks and potential benefits from investing in them. Moreover, the data available are not always standardised or easily comparable, partly because SMEs are inherently diverse and their characteristics relatively hard to capture in a few quantitative indicators. As a result, assessing the creditworthiness of a business is costly, and these costs generally do not scale up in a linear way with the size of the enterprise or its financing needs. Firms with relatively modest financing needs are therefore most at risk of being excluded from the banking sector and from financial markets.

The development of a credit risk assessment infrastructure plays a crucial role in overcoming existing information asymmetries and improving transparency in SME finance markets. Credit registries, credit bureaus and supplier networks, in particular, can provide information on SMEs’ creditworthiness by disclosing data on the liabilities of SMEs and their repayment record. A meta-analysis of the literature concludes indeed that the existence of credit registries and bureaus is positively associated with the size of the credit market and stronger repayment performance (OECD, 2012a). The establishment of such institutions can thus address the information asymmetries that are central to the reluctance of banks to lend to certain businesses and for encouraging investors to participate in SME markets, by providing evidence on on-time payments, late payments/arrears, defaults, bankruptcies on previous contractual financial obligations, etc.

A study from the World Bank reveals that 31 out of 34 OECD countries have a functioning credit bureau or credit registry (or both), covering at least 5% of the adult population (World Bank, 2014b). The regulatory and practical design of these institutions matter for their performance, with wide cross-country differences with respect to historical information on repayments, inclusion of balance sheet data, reporting requirements and so on (OECD, 2012a). In addition, credit registries are often used for regulatory purposes rather than to provide information on creditworthiness. However, a study in six European countries showed that, even within this limited subset of countries, large differences persist in the rigour and comprehensiveness of credit reporting systems. Annual accounts are often only available with significant time lags of up to 18 months, not audited and not easy to assess, partly because of privacy concerns, data protection and confidentiality laws. Portuguese banks, for example, can only access information on the current credit position of a potential client and not on historical data (Bain & Company and IIF, 2013).

In this context, the Banque de France’s model stands out with its FIBEN (Fichier bancaire des entreprises) service, gathering a relatively comprehensive set of data on SMEs. The FIBEN database integrates all available financial information about an individual firm, provides a score for a fee, and is accessible to banks operating in France. The Banque de France also performs an independent risk analysis of French enterprises, allowing banks to assess credit risks of potential clients at low costs, thereby contributing to SMEs’ access to bank finance. In 2014, nearly 300 000 French companies, the vast majority of them SMEs, were covered in the FIBEN database. Credit information is, up to now, only available for banks operating in France and, more recently, also for insurance companies. Access to these data by a wider range of market constituencies, such as institutional investors, might encourage the development of alternative finance instruments. The recent experience of the Euro Secured Notes Issuer (ESNI) initiative, which aims to stimulate a SME securitisation market, illustrates the potential of FIBEN (and other similar databases) for non-bank providers of external finance to SMEs (see Box 2.4).

A well-functioning securitisation market for SME assets allows banks to refinance themselves on financial markets, using SME loans as collateral. This would not only spur bank lending by transferring credit risk and relieving their balance sheet, but would also allow for SME access to the capital market and enable institutional and long-term investors to participate in SME financing on a larger scale. The securitisation of SME assets remains underdeveloped compared to other asset classes such as mortgage loans, however, in large part due to the lack of standardised and reliable data on credit risk of SME loans.

The ESNI initiative aims to overcome these information asymmetries in France by making use of both the Banque de France’s credit assessment of nonfinancial companies, as well as internal ratings from banks. The ESNI was set up in March 2014 by private banking groups and with support from the Banque de France as a Special Purpose Vehicle, with the first securities issuance taking place one month later for an amount of for EUR 2.65 billion. The securities, regulatory and banking supervisory authority ensures that this scheme is compliant with existing regulation

The provision of information from the central bank to a broad spectrum of financial institutions and market constituents on the credit quality of SME loans, complemented by internal ratings from the banking system, is crucial for the success of this instrument. It allows for issuances independent of rating agencies. The ESNI is thus a simple and transparent instrument that could potentially be replicated in other jurisdictions.

Source: French Banking Federation.

The Credit Risk Database (CRD) in Japan provides another example of a relatively comprehensive and large-scale credit risk database (see Box 2.5).

Japan established its Credit Risk Database (CRD) in 2001, led by the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Small and Medium Enterprise Agency (SMEA). The CRD provides credit risk scoring, data sampling, statistical information and related services. The database therefore does not only facilitate SMEs’ direct access to the banking sector, but also smooths access to the debt market by enabling the securitisation of their claims.

The database covers financial and non-financial information, such as

-

data on sales and profits;

-

information on investments and inventories;

-

ratios such as the operating and ordinary profits to sales;

-

ratios expressing SMEs’ net worth, as well as their liquid, fixed and deferred assets and liabilities;

-

interest and personnel expenses; and

-

default information (covering three months or more arrears, subrogation by credit guarantee corporations, bankruptcies and de facto bankruptcies).

Data on about half of all Japanese SMEs are collected and consolidated from credit guarantee corporations, government-affiliated financial institutions, and private financial institutions and then made available to CRD members who submit data to the platform.

In sum, the CRD offers high-precision scoring models constructed from its large database, to evaluate SMEs’ credit risk and to facilitate their direct access to the banking sector. Furthermore, the scoring models can also be used for loan securitisation, as well as for credit evaluation in rating pooled for securitisation. . Investors can then refer to the scores based on the models for decision making in investing securities. In addition and similar as in France, access to this database by a broader range of market participants active or potentially active in the SME finance market, could facilitate overall more investments in the SME sector.

Source: Yoshino and Taghizadeh-Hesary, 2014 and written exchanges with Japanese officials.

Most credit registries and bureaus offer credit scoring, where information from several creditors and other sources are pooled. In short, a credit score summarises the available data in a single number reflecting the probability of repaying a debt. While credit scoring methods were originally designed to handle consumer loans, they have proven to be effective for predicting the potential delinquency of loans to SMEs. A study by the Small Business Administration (SBA) in the United States illustrates that business credit scoring has made credit more available to small businesses, especially for relatively risky loans at the margin (SBA, 2014). Credit scoring is offered in 24 out of 31 OECD countries which have a functioning credit bureau or credit registry (World Bank, 2014b).

Czech SMEs, for instance, can buy a rating for around CZK 5 000 (i.e. EUR 200) at the Prague Chamber of Commerce, which is based on quantitative information and similar to a credit rating performed by large banks, and use this information to obtain finance from different sources. Similarly, Peru introduced an innovative credit information scheme akin to the installation of a credit bureau, which uses a large technology platform to process and analyse repayment data held by suppliers. This platform contains reliable information on how diligently suppliers have been paid, and firms that participate in this scheme can use their past repayment record as proof of their credit worthiness and reliability.

However, privacy concerns, data protection and confidentiality laws limit the availability of information about credit risks to a wide range of market participants beyond the banking sector in many countries. For this reason, some alternative providers of finance, such as suppliers of trade credit, often do not have access to credit risk information. This, combined with the incomplete coverage and the question of reliability of the information gathered on SMEs, severely restricts the usefulness of credit reporting systems for alternative providers of external finance. This contrasts with relevant data on large corporations and on individuals, which are, by and large, widely available in most advanced economies. Recently, there have been efforts in a number of countries to increase the quality of credit risk assessments and make them available to a wider constituency of market participants by proposing concrete actions that relevant authorities and policy makers could undertake to address current shortcomings (World Bank, 2014a).

Direct investments through funds, co-investment funds and funds-of-funds

Direct investments by governments through funds, co-investment funds and funds-of-funds have been identified as an effective and popular means of addressing supply-side gaps in the availability of start-up and early stage capital. These initiatives have become more widely used in the aftermath of the financial crisis as private equity financing dried up significantly (OECD, 2015a). If successful, these initiatives can increase the scale of SME markets, enhance networks and catalyse private investments that would not have materialised in the absence of public support. At the same time, however, some studies appear to suggest that government-backed venture capital schemes perform more poorly than their private sector counterparts (see for example Preqin Global Private Equity and Venture Capital Reports for more detailed evidence). Recent evidence suggests that governmental VC schemes are more successful when they act alongside private investors, for example through governmental fund-of-funds rather than through direct public investments. Indeed, the focus of support instruments “has shifted from government equity funds investing directly to more indirect models such as co-investments funds and fund-of-funds” in OECD countries (EIF, 2015).

In the early 1990s the Israeli government set up Yozma, a programme, today frequently associated with the development of Israel’s vibrant venture capital industry. Founded with a budget of USD 100 million in 1993, it initially established 10 venture capital funds, contributing up to 40% of government funds towards the total capital investment. The rest was provided by foreign investors, who were incentivised to invest in selected start-ups by risk guarantees. Nine of the 15 companies that received Yozma investment went public or were acquired and only a few years later, in 1997, the funds were privatised and the government received a return on its original investment with 50% interest (OECD, 2011).

In Denmark, Danish Growth Capital (Dansk Vækst Kapital, DGC), seeks to improve the access to risk capital for entrepreneurs and SMEs by creating a fund-of-funds that invests in small cap-, mid cap-, venture- and mezzanine funds. The capital base – a total of DKK 4.8 billion – has been sourced entirely from the Danish pension funds. One-quarter is invested directly in DGC by the pension funds, and three quarters are provided as a loan to the Danish public investment fund, The Growth Fund (Vækstfonden), which subsequently invests it for equity in DGC. This essentially creates two asset classes and alleviates the risk-based funding requirements of the pension funds. The interest rate of the loan is the government bond rate plus an illiquidity premium. Accordingly, The Growth Fund bears the risk of three-quarters of the fund-of-funds’ investments.

In Chile, the development agency CORFO currently operates two programmes that support the VC industry: The Early Stage Fund (Fondo de Etapa Temprana, FT) and The Development and Growth Fund (Fondo de Desarrollo y Crecimiento, FC). The Early-Stage Fund (FT) is designed to foster the creation of new investment funds that provide high-growth, innovative small and medium sized firms with financing. The investment fund managers acquire stake in SMEs and get involved in the operations of the firm. The Development and Growth Fund (FC) programme is aimed at promoting the creation of investment funds that invest in firms with a maximum initial equity of USD 9 million with high-growth potential, which are currently at an expansion stage.

In Turkey, the Turkish Investment Initiative (TII) founded in 2007 is Turkey’s first ever dedicated fund of funds and co-investment programme. TII currently has two sub-funds: The Istanbul Venture Capital Initiative (iVCi) and the Turkish Growth and Innovation Fund (TGIF). iVCi was established to provide access to finance to SMEs by acting as a catalyst for the development of the venture capital industry in Turkey through investments in independently-managed funds and via co-investments. For the time being, iVCi has signed ten commitments including one co-investment, and reached a total of 57 companies. The new sub-fund TGIF will focus on investing in private equity and venture capital funds that aim to invest in SMEs which have high growth potential, high rates of return and a competitiveness advantage in their respective sector.

Box 2.6 below provides another example of a government-funded equity investment fund from the United Kingdom that recently underwent an evaluation. However, to date, there is overall little evidence concerning the effectiveness, impact and additionality of these programmes, mainly because formal impact evaluations remain relatively scarce. The OECD (2013c) has identified some key recommendations that should be considered in order for direct public funds to be successful. It is for instance crucial that these funds do not crowd out private investments, that they are channelled through existing, market-based systems and that they aim at leveraging private sector funding. In short, they should complement private market initiatives, rather than replace them.

Enterprise Capital Funds (ECFs) are financial schemes established by the UK Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) to address market failures in the provision of equity finance to SMEs. Government funding is used alongside private sector funds to establish funds that operate within the “equity gap”; providing finance to small firms where an investment has the potential to provide a good commercial return.

A recently published study assesses the impact of ECFs in the United Kingdom and positively rates its overall impact, the main finding being that ECFs indeed manage to address the sub-GBP 2 million equity gap faced by young, potential high-growth businesses requiring investments, and have evolved over time so as to adapt to meet the challenges associated with changing UK early stage entrepreneurial financing requirements in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

The UK Government introduced the ECF schemes in 2006. Entailing a significant increase in the size and scale of available funding, notably with regard to the previous small-scale, public-led Regional Venture Capital Funds, this move was first and foremost intended as a concerted effort to develop private, VC-led co-investment funds. The funds require a minimum share of one third private investment and restrict private individual investment to 50% of the private funding contribution to simultaneously broaden the private investment base. Between 2000 and 2012, the BIS placed GBP 600 million in 34 VC funds, financing over 1 000 businesses.

The objectives of the ECFs were mainly twofold: first, they were intended to provide gap funding for potential high-growth SMEs, mainly in seed and early stage development requiring funding between GBP 250 000 and GBP 2 million; and second, they were designed as a demonstration model for early stage institutional VCs, with the longer-term goal of establishing a UK early stage VC ecosystem that encourages new private fund managers into the market.

Particular success factors include avoidance of duplication or displacement of private initiatives in addressing the existing equity gap, along with the progressive development of innovative strategies for inter-regional and international investing that increase syndication and investor networking, diversify portfolios, spread risk, and improve planning for follow-on funding and exits. However, as also outlined in the study, while the ECF scheme aimed to establish a sustainable private seed and early stage VC market in the United Kingdom and then withdraw, persistently poor exit markets in the post-2007 period have prevented both a recycling of investment funds, as well as a signaling of widespread encouragement of private VCs into these markets. As a result, the author finds that there is currently no evidence of the scheme withdrawing, and it may be likely to have an increasing presence in follow-on investments upstream into later phases in order to generate optimal exits.

Source: Baldock, 2016.

Financial literacy programmes

In contrast to large enterprises, small businesses usually lack the resources to hire a dedicated financial professional. Although the financial knowledge of business owners and entrepreneurs on the use of financing instruments is currently underexplored, there is some evidence that their financial knowledge is limited. The shortcomings in entrepreneurs’ financial literacy, in turn, are a likely to be a main cause for the overreliance of many businesses on overdrafts, short-term bank credit and credit card debt, even when other finance instruments might be more appropriate. These weaknesses may also lead to the misuse of costly financial products. In addition, the lack of financial knowledge frequently limits entrepreneurs and business owners to make full use of available government support. A recent survey conducted among UK SMEs indeed shows that government initiatives usually only reach a minority of businesses, and often only those who are already relatively well-informed about potential alternatives to straight debt.

Against this backdrop, a report by the OECD International Network on Financial Education (INFE), welcomed by the G20 Global Partnership on Financial Inclusion (GPFI) in September 2015, underlines the broader role of financial education in supporting SME access to finance. The report outlines the specific issues financial education support for small enterprises should address, and how education programmes may fit into national policy frameworks. In addition, it identifies appropriate target groups, scope and delivery methods, and proposes tools, in particular an internationally comparable, SME-tailored questionnaire, that can help policy makers better address existing gaps (OECD/INFE, 2015).

While many countries have a national strategy in place to foster financial literacy, only some of them have a specific focus on SMEs, even though financial literacy needs of entrepreneurs go much beyond those of the general population. Entrepreneurs have to be able to disentangle their personal and business finances, keep records, be able to use financial statements and financial ratio’s to assess the health of their business, identify and approach providers of finance and investors, have a grasp of financial risk and cash flow management, and understand the economic and financial landscape of relevance for businesses (Atkinson, 2015). This calls for an adapted curriculum in these programmes.

Some countries have developed financial education programmes for entrepreneurs and would-be entrepreneurs. Although the evidence base regarding the effectiveness of these programmes should be improved, most research suggests that these programmes may indeed produce beneficial results and that they are a relatively cost-effective way to boost business performance and growth. Financial education is also often provided as part of more general services to support entrepreneurial learning, often targeted at specific groups in society such as young people or women (Cho and Honorati, 2013).

Table 2.3. provides some examples of topics covered in programmes that target entrepreneurs and owners of small businesses. Although there are some differences in the curricula, an understanding of financial and risk management, record keeping and compliance, along with knowledge about the main finance providers and their requirements are commonly covered (the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, 2014). More research is required to identify the impact of these programmes as well as their cost effectiveness.

In addition, financial education is often provided by the private or non-for profit sector. A meta-analysis of research on the effectiveness of such programmes in emerging economies illustrates that the involvement of the private sector in government-backed programmes often increases their effectiveness (Cho and Honorati, 2013).

Non-financial services and support measures

Evidence indicates that complementing financial support for SMEs with non-financial elements such as counselling and monitoring provides good results. For instance, credit guarantee schemes typically offer assistance in the preparation of accounting statements and information on financial markets, and even consultancy-type services, aimed at improving firm competitiveness and productivity (OECD, 2012b). A study by the European Commission summarising results from 12 counterfactual impact evaluations, illustrates the effectiveness in combining financial innovation support for SMEs, such as the provision of grants and loans, with non-financial elements like business advice or network opportunities for the beneficiaries of the programme. Programmes that combine financial and non-financial elements thus seem to contribute to the impact of the policy initiative and to significantly improve the long-term survival chance of business start-ups (Mouqué, 2012).

Similarly, in 2013, BDC, Canada’s development bank, requested an independent, quantifiable assessment of whether the financing and consulting services it was providing actually helped accelerate the success of entrepreneurs. To this end, Statistics Canada developed a longitudinal database of BDC clients (the “study group”) and non-clients (the “comparison group”) and then compared their performance in each year over the 2001-10 period. The statistical analysis revealed that BDC had a positive impact on all examined performance indicators, but most notably when financing and consulting services were used in combination, where sales growth was 8% to 25% greater for BDC clients compared to the performance of non-clients.

In emerging economies, where informal entrepreneurship by business owners with poor financial knowledge is generally more entrenched, complementing financial support with the provision of financial education seems to work especially well. For instance, the Credit Guarantee Corporation (CGC) in Malaysia was established as early as 1972. The lack of knowledge on the working of the financial system, the inability to produce a business plan and to make credible financial projections, or even to conduct proper financial record-keeping were quickly identified as major impediments to the successful development of businesses and the repayment of the guaranteed loan. CGC therefore also offers advisory services on financial and business development in order to help beneficiaries of their programmes make better use of their sources of finance. These advisory services on financial and business development matters were considered to be very successful and have been significantly expanded over time. In addition, the CGC offers credit information through the Credit Bureau Malaysia Sdn Bhd to collect and provide reliable credit information on SMEs and rating services that goes beyond collateral and historical financial information (Credit Guarantee Corporation Malaysia Berhad, 2012).

Business incubators also typically help their clients to access finance, from the banking sector and beyond, and provide advice and consulting to improve accounting and financial management. In the United States, where business incubation support falls under the remit of state governments, initiatives to support the development of these institutions have proliferated since 2000 (NBIA, 2008).

Investor-readiness programmes

Equity-type instruments tend to require a higher level of financial sophistication on the part of the business owner or entrepreneur seeking finance. Professional equity investors usually need an elaborate and detailed business plan, in-depth financial information and seek investments that comply with their due diligence requirements, which may pose difficulties to some entrepreneurs and business owners. In the literature, this is referred to as investor-readiness, i.e. the ability of meeting the requirements of external investors. In an overview of the literature on investor readiness programmes, Mason and Kwok (2014) conclude that “there is considerable evidence, particularly amongst the business angel community, that investors are frustrated by the low quality of the investment opportunities that they see and so are unable to invest as frequently or as much as they would like.” The three main reasons why projects had been refused were: weaknesses of the management team and/or entrepreneur, flawed or incomplete marketing strategies and flawed financial projections.

Investment readiness programmes for entrepreneurs are supported in a number of countries. Their central aim is to raise the quality of investment opportunities by addressing the shortcomings outlined above. One aspect of such programmes usually consists of providing information on the requirements of investors, while another provides concrete support for meeting these standards (see Box 2.7 for an example from Ireland). A 2012 OECD financing questionnaire showed that many countries have investor readiness programmes for entrepreneurs and that, overall, support for these programmes increased between 2008 and 2012. These programmes typically focus on access to equity financing and on helping entrepreneurs understand the specific needs of these investors (OECD, 2013c). As a relatively novel form of intervention, frequently developed with a specific focus on fast growing, innovative SMEs, these programmes have not been the subject of systematic policy evaluation, however.

InterTradeIreland is a cross-border trade and business development body funded by the Department of Enterprise Trade and Investment (DETI) and the Department of Jobs Enterprise and Innovation (DJEI). Its goal is to support Irish SMEs by helping them explore new cross-border markets, develop new products, processes and services and become investor ready.

In acknowledgment of the fact that one of the biggest challenges for equity raising businesses is to become “investor ready”, the organisation offers varied support measures in order to increase Irish SMEs’ chances of success when seeking venture finance. Programmes and services typically target more established SMEs that already have a satisfactory trading record. Offered services to foster investor readiness include, among other things:

-

One-on-one counselling interviews with an advisor specialised in equity, venture capital and business development, providing guidance to early stage, high growth ventures that intend to raise funds in the next 12 months. He advises on the firm’s fundraising requirements and assesses its “investor readiness” by acting as a sounding board for the SME management team before they approach the investment community to seek capital.

-

A series of free, monthly clinics and regional workshops are held at various locations across the island each month for established local SMEs who are interested in learning about new and alternative sources of finance for their business and that fulfil certain eligibility criteria. The events aim to encourage SMEs seeking finance to do so in a strategic manner with a well-prepared business plan and to explore all finance options available to them.

-

The Seedcorn Investor Readiness Competition mirrors the real life investment process and aims at improving firms’ ability to attract investment. The competition is aimed at early and new start companies that have a new equity funding requirement and has a total cash price fund of EUR 280 000.

-

An annual venture capital conference and regular “Meet the Funder” events aimed at companies with growth ambitions, providing information on and access to a range of funding providers, and advice on how to approach the funding process. At the events companies are also given opportunity to network with funding providers.

In addition, InterTradeIreland offers Funding Advisory Services, mostly in the form of online material that firms can download from the organisation’s website. The materials include guidance on how venture funding works, what investors are looking for, a breakdown of all the venture funds and business angel networks on the island and their contact details in one searchable database, as well as hints and tips on refining the business plan and tailoring it to specific investor needs.

Source: www.intertradeireland.com/.

France Angels, for instance, was established in 2001 by five Business Angel networks. Its goal was originally to promote BA investments, to recruit new investors and to professionalise the industry. To do so, the organisation develops tools, posts them on its website available for every member, and gathers useful business documents for network management and deal flow processing. It also created a forum to quickly answer to a variety of questions. Moreover, France Angels provides national and regional support and service by creating partnership and co-investment with seed and VC funds. France Angels organises around 40 events with over 3 000 participants a year and is also responsible for collecting data on the angel market in France (OECD, 2016).

In Germany, BAND (Business Angels Netzwerk Deutschland) is the recognised umbrella organisation of German Business Angels and their networks, funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. For sustained professionalisation of the German business angels market, BAND organises training events (BANDacademy) and offers practical assistance (BAND Best Practice Case and BANDquartel) in areas such as idea generation, writing a business plan, support/coaching the entrepreneur in starting up and financing, informal studies, stakeholder brainstorming, and other useful tools for entrepreneurs. Plans are underway to train the stakeholder groups – business angels, investors and entrepreneurs (European Commission, 2006).

Support to industry networks, associations and the facilitation of links between entrepreneurs and investors

The majority of OECD countries have programmes in place to develop “social networks” linking entrepreneurs seeking finance with investors, for example by providing support to business angel networks (BANs). These networks often also aim to connect investors with other financial players in the financial eco-system, such as government agencies, stock exchanges, financial consultants, venture capital associations, banks, incubators and crowdfunding platforms. The creation of links between investors, entrepreneurs and larger companies, are of particular importance, since they can potentially lead to an increase of successful exits of investments (see Box 2.8 for an example from New Zealand). Matchmaking services are often complemented by additional support and mentoring services, both for (potential) investors and entrepreneurs and SMEs (OECD, 2013c).

“Better by Capital” is a programme developed by New Zealand Trade and Enterprise (NZTE), the government’s international business development agency. Launched in July 2013, it is one of the numerous initiatives in the Building Capital Markets of the Government’s Business Growth Agenda and run in partnership with New Zealand and international financial institutions, intermediaries, banks and investor networks.

The programme’s overarching goal is to render the capital raising process more transparent and improve SMEs’ chance of accessing the right type of funding that corresponds to the firm’s stage in its lifecycle. It seeks to accelerate the ability of companies to access alternative capital markets, improve their capacity to be “match fit” when sourcing new capital, and shift their marketability away from traditional, more standard financial instruments to better support firm growth.

The programme consists of three-stages that first help companies understand their capital options (Orientation), subsequently improve their investment proposition (Readiness), and ultimately ensure companies attract the right capital, from the right providers at the right time (Connections). Since New Zealand-based and international investment managers administer the programme, which is delivered in partnership with private sector specialists with capital raising experience, a core element of the programme is to help SMEs build key relationships by facilitating introductions to targeted investors and networks.

In addition, NZTE also runs a series of annual investment showcases to present investment deals to international and domestic investors.

Source: www.nzte.govt.nz/en/.

Increased support for business angel networks is a good example of a ‘demand-side’ policy that seeks to improve the exposure of high-quality firms available to these investors. Currently, angel markets in many countries are essentially constituted by anonymous individuals operating within a fragmented system. For these investors to be in a position to make sizeable initial investments and undertake appropriate follow-on investments in a manner that mirrors the professionalism of institutional venture capital investors, markets would have to evolve considerably toward an increasingly co-ordinated network of professionally organised groups. Improving the flow of high quality deals from such networks to venture capital funds should thus be a priority for policy makers (Nesta/ BVCA, 2009).

With regard to the provision of general networking opportunities and exchange of knowledge among peers, SME Corp Malaysia, the Malaysian SME agency, has developed a number of programmes to support small firms. In recognition of the value of systematic and intelligent networking, which allows for the identification of synergies and the establishment of linkages between SMEs and large companies, the agency designed its Business Linkage (BLing) Programme to create such opportunities through Business Matching Sessions conducted at annual flagship events, as well as leveraging on various other platforms and opportunities. As of 31 December 2014, the programme had generated a total of RM 428.6 million in potential sales through 536 sessions involving 303 SMEs. In addition, SME Corp. Malaysia organises the SME Annual Showcase – SMIDEX, an annual event that showcases capabilities and capacities of Malaysian SMEs in offering products, services and technologies for the global market. SMIDEX also provides Business Matching Sessions with the aim of assisting SMEs to establish strategic business partnerships and business linkages, as well as to facilitate meaningful exchange of functional knowledge with large enterprises.

Conclusions and policy implications

Since credit is and will remain the main source of finance for SMEs, it is important to stress the complementarity of bank lending and alternative financing tools. This fact is also underscored in the G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing, which advocate a two-pronged approach to improve access to credit on the one hand, and develop a more diversified financial offer for SMEs on the other. This is all the more important given that some SMEs are not appropriate candidates for debt financing, owing e.g. to their lack of collateral or positive cash flows, their need for longer maturities to finance capital expenditure and investment, or other impediments to servicing debt, such as irregular cash flow generation. Available evidence suggests that there is an equity gap for risk financing, which is particularly pronounced for fast-growing companies. Yet it is precisely these types of instruments which, if developed further, could play an important role in funding the firms which have the greatest potential to grow and create jobs. Broadening the range of financing instruments is therefore essential to address diverse financing needs along the firm’s life cycle. However, SME funding continues being viewed as an overall difficult business, mainly because the segment as a whole is characterised by low survival rates and large heterogeneity, which makes it considerably more challenging to assess risks or gauge the potential for positive returns on investment (Nassr and Wehinger, 2016).

Challenges in the provision of finance to small firms can be motivated by both supply-side and demand-side factors. In addition, there is a complex interaction of both structural and cyclical variables that needs to be addressed through a holistic approach. However, disentangling these variables is often difficult, since changes in demand and supply are generally contemporaneous. In this context, so called “thin markets”, where a limited number of investors and entrepreneurial high-growth firms have difficulty finding and contracting with each other at reasonable costs, stem from the difficulty of matching supply and demand efficiently due to the highly uncertain and complex nature of these markets, which are comprised of a range of different institutions. Moreover, these markets are knowledge intensive and usually have to operate over long periods of time before clear results on performance become available.

As a result, financial markets for SMEs often remain fragmented and underdeveloped. Their small scale and liquidity further limits the interest from potential entrants, most notably professional investors which, in turn, also limits the entrance of intermediaries and other participants in the financial ecosystem, such as brokers, market-makers, advisors, researchers, platforms (Nesta/ BVCA, 2009).

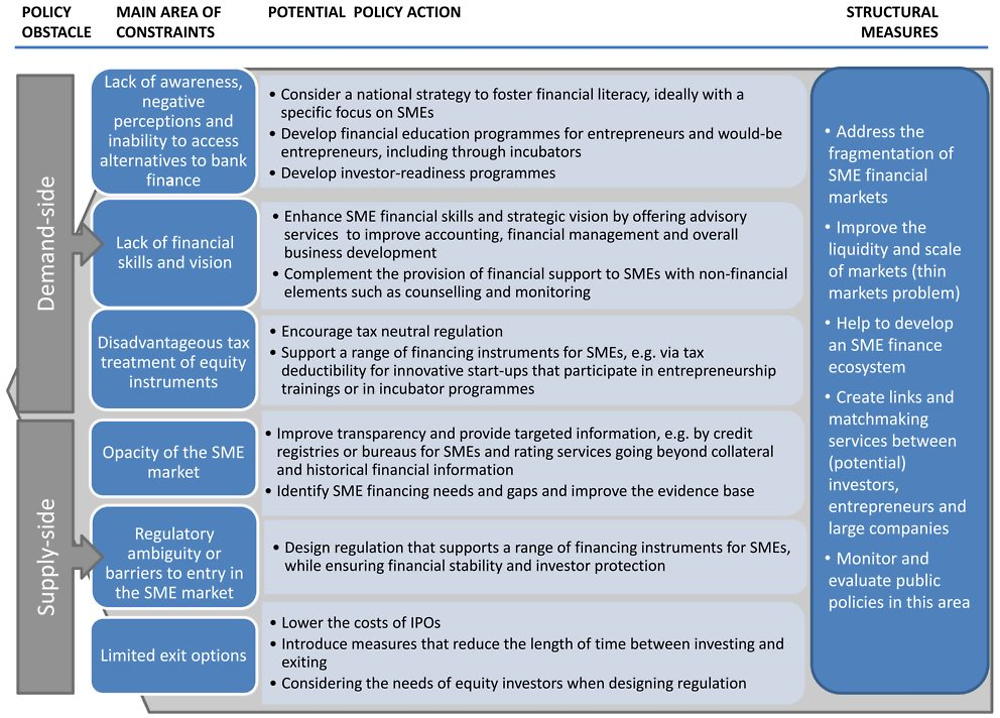

In recent years, many new initiatives with the explicit aim to encourage equity investments in innovative and high-potential SMEs have seen the light. Available evidence suggests that capital markets are already making a substantial contribution to the financing of SMEs in some OECD countries, particularly the United States, and have the potential to contribute more in other regions of the world. The private capital market, in particular, offers advantages to SMEs, mainly through its flexible form and conditions. Collective investment vehicles constitute another instrument that may have the potential to render the public segment of the capital market more accessible to SMEs. The momentum to develop these markets is thus building, and there is a growing need to share policy experiences and identify good practices that have the potential to address the above-mentioned challenges. Figure 2.1 provides a summary of the types of approaches used to address specific challenges.

Recognising the need for better access of SMEs to capital markets, there is a clear role for policy to catalyse institutional long-term investor participation. High monitoring costs, absence of track record and other information asymmetries can be addressed through measures and tools that improve transparency. The creation of an improved credit information infrastructure, for instance, is an element now widely recognised as central for the development of an efficient SME financing ecosystem. Furthermore, governments can help bridge the educational gap of SMEs by raising their awareness of available capital market financing options and enabling them to gain the skills required to tap these markets. A co-ordinated approach on regulation, including a neutral tax framework, which reduces asymmetric treatment of debt and equity, can help avoid distortions in risk pricing and stimulate investor appetite. Finally, the need for improving the evidence base on SME debt and non-debt financing should be recognised. The lack of hard data on SME access to diverse financing instruments represents an important limitation for the design, implementation and assessment of policies in this area. Overall, a better understanding of the challenges associated with SMEs’ access to finance is called for. In order to develop complementary finance instruments for small firms, demand-side and supply side barriers need to be addressed in tandem. Even if supply-side barriers are lifted, alternative sources of finance will remain underdeveloped as long as entrepreneurs continue to turn to bank lending as their default option when seeking finance. Conversely, tackling demand-side barriers will lead to limited success if supply-side issues continue to be a bottleneck. At the same time, an integrated market perspective should also take account of cyclical and structural issues, along with the time needed to put in place the various conditions for a well-functioning frameworkfor SME financing. Thus, a comprehensive approach to SME financing is needed when seeking to address existing obstacles. The OECD and the SME financing scoreboard will continue advance the state of knowledge of these issues and identify emerging trends and opportunities for well-functioning markets for SME finance.

References

AFME (2015), “Why equity markets matter. The heart of Europe’s economy”, December 2015, www.afme.eu/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=13535.

The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (2014), “Financial education for entrepreneurs: What’s next?”, www.accaglobal.com/content/dam/acca/global/PDF-technical/small-business/pol-tp-fefe.pdf.

Baeck, Collins and Zhang (2014), “Understanding alternative finance: The UK finance alternative finance industry report 2014”, Nesta/University of Cambridge, November 2014, www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/understanding-alternative-finance-2014.pdf.

Bain & Company and IIF (2013), “Restoring financing and growth for European SMEs: Four sets of impediments and how to overcome them”, www.bain.com/Images/REPORT_Restoring_financing_and_ growth_to_Europe’s_SMEs.pdf.

Baldock, R. (2016), “An assessment of the business impacts of the UK’s Enterprise Capital Funds”, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, January 18, 2016, http://epc.sagepub.com/content/early/2016/01/14/0263774X15625995.full.pdf+html.

British Business Bank (2016), “Small Business Finance Market 2015/16”, British Business Bank Plc, February 2016, http://british-business-bank.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/British-Business-Bank-Small-Business-Finance-Markets-Report-2015-16.pdf.

Business Development Bank of Canada (2013), “Manufacturers: Accessing to financing and specific needs, BDC viewpoints study- May 2013”, www.bdc.ca/EN/Documents/analysis_research/manufacturing_ survey.pdf.

Cho and Honorati (2013), “Entrepreneurship Programs in Developing Countries; A meta regression analysis”, The World Bank Human Development Network Social Protection and Labor Unit, http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/1813-9450-6402.

Credit Guarantee Corporation Malaysia Berhad (2012), “Catalysing SME growth”, www.cgc.com.my/wp-content/themes/crystalline/doc/CGC_Info%20Booklet.pdf.

de Mooij, R.A. and M.A. Devereux (2011), “Alternative Systems of Business Tax in Europe: An applied analysis of ACE and CBIT Reforms”, International Tax and Public Finance, February 2011, Volume 18, Issue 1, pp 93-120, http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10797-010-9138-8#.

European Commission (2015), “Survey on the access to finance of enterprises (SAFE)”, Analytical Report 2015, http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/7504/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

European Commission (2014), “Directive 2014/65/EU on markets in financial instruments”, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0065&from=EN.

European Commission (2006), “Investment readiness: Summary report of the workshop, Brussels, 28 November 2006”, http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/newsroom/cf/_getdocument.cfm?doc_id=1170.

European Investment Fund (2015), “European Small Business Finance Outlook”, December 2015, Working Paper 2015/32, www.eif.org/news_centre/publications/eif_wp_32.pdf.

G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing, 2015, www.oecd.org/finance/G20-OECD-High-Level-%20Principles-on-SME-Financing.pdf.

Gambacorta, L., J. Yang and K. Tsatsaronis (2014), “Financial structure and growth”, BIS Quarterly Review, March.

Giovannini, A., C. Mayer, S. Micossi, C. Di Noia, M. Onado, M. Pagano and A. Polo 2015, “Restarting European Long-Term Investment Finance”, A Green Paper Discussion Document, CEPR Press and Assonime, January.

Government of Canada (2002), “Gaps in SME Financing: An Analytical Framework”, SME financing data initiative, prepared for Small Business Policy Branch, Industry Canada, by Equinox Management Consultants Ltd., February 2002, www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/061.nsf/vwapj/FinancingGapAnalysisEquinoxFeb 2002_e.pdf/$FILE/FinancingGapAnalysisEquinoxFeb2002_e.pdf.

Intuit Canada (2014), “Bridging the gap, How boosting financial literacy leads to small business success”, http://intuitglobal.intuit.com/delivery/cms/prod/sites/default/intuit.ca/downloads/quickbooks/bridging_the_gap.pdf.

IOSCO (2015), “SME Financing through Capital Markets”, The Growth and Emerging Markets Committee of the International Organization of Securities Commissions, Final Report, July 2015, www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD493.pdf.

Kestens, K., P. Van Cauwenberge and J. Christiaens (2013), “The effect of the notional interest deduction on the capital structure of Belgian SME”, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 2012, Volume 30, pages 228-247, www.envplan.com/fulltext_temp/0/c1163b.pdf.

Lusardi and Mitchell (2014), “The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 52(1), pp. 5-44, March, www.nber.org/papers/w18952.

Mason and Botelho (2014), “The role of the exit in the initial screening of investment opportunities: The case of business angel syndicate gatekeepers”, to be published in International Small Business Journal, 34, March 2016, www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_302905_en.pdf.

Mason and Kwok (2014), “Facilitating access to finance: Discussion paper on investment readiness programmes”, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/investment/psd/45324336.pdf.

Mouqué (2012), “What are counterfactual impact evaluations teaching us about enterprise and innovation support?”, European Commission Regional Focus 02/2012, http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/focus/2012_02_counterfactual.pdf.

Myers, S.C. (1984), “The Capital Structure Puzzle”, The Journal of Finance 39 (3), pp. 575-592.

NBIA (2008), National Business Incubation Association, “Across state lines: U.S. incubators report how state governments support business incubation”, www.nbia.org/resource_library/review_archive/0807_01.php#.

Nassr, I.K. and G. Wehinger (2016), “Opportunities and limitations of public equity markets for SMEs”, OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends, Vol. 2015/1, https://doi.org/10.1787/fmt-2015-5jrs051fvnjk.

NESTA/BVCA (2009), “From Funding Gaps to Thin Markets: UK Government Support for Early Stage Venture Capital”, (Nightingale, Murray, Cowling, Baden, Mason, Siepel, Hopkins and Dannreuther), http://admin.bvca.co.uk/library/documents/Thin_Markets_report_-_Final.pdf.

OECD (2016), “Financing SMEs and entrepreneurs 2016: An OECD Scoreboard”, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fin_sme_ent-2016-en.

OECD (2015a), “New approaches to SME and entrepreneurship finance: Broadening the range of instruments”, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264240957-en.

OECD (2015b), “Taxation of SMEs in OECD and G20 Countries”, OECD Tax Policy Studies, No. 23, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264243507-en.