1. Assessment and recommendations

Indonesia has made remarkable economic, political and social progress over the past two decades, as the government has embarked on ambitious reforms to modernise the country. A founding member of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and of the G20, which it will chair in 2023, Indonesia plays an ever more influential role in the regional and global landscape. While it was slowly on the road to become a high-income economy, the COVID-19 pandemic has plunged Indonesia into a major crisis.

Sound macroeconomic policies and progress to develop the social protection system have allowed the country to increase living standards and reduce poverty in both rural and urban areas. Underpinned by prudent macroeconomic policies, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita has risen by 70% during the past two decades with a GDP growth of approximately 5% per year since 2013 (OECD, 2018a). Recognising that the private sector is essential for prosperity and development, measures to improve the business environment have also been high on the agenda of successive governments.

Meanwhile, the health crisis spurred by the COVID-19 outbreak is generating dramatic economic and social turmoil. Growth projections for 2020 have been significantly revised downwards by the government and international organisations. The OECD expects a severe recession with GDP projected to contract by 3.3% in 2020 (OECD, 2020a). Amid social containment measures, in April 2020 economic activity dramatically contracted and the recovery has been very slow and incomplete. Tourism and manufacturing are the most affected sectors and job losses have exceeded 2.8 million since mid-March (OECD, 2020b). The government took a series of well-coordinated monetary and policy measures to respond to the crisis, although their impact has been less supportive than expected.

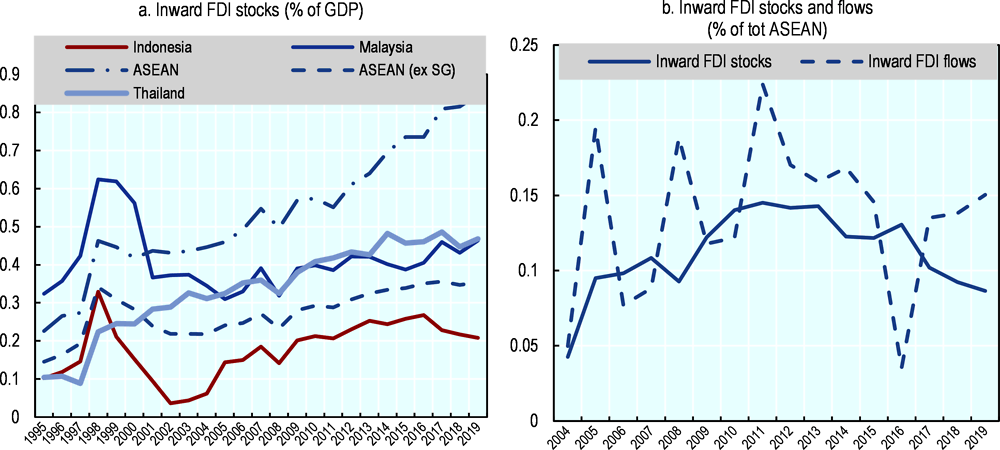

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has traditionally played a key role in raising employment and productivity and in generating exports in Indonesia, which has historically been a relatively important FDI destination in ASEAN. The largest share of FDI during 2009-18 went to manufacturing, although the share is declining and services have received increasing flows. The primary sector also attracts a large share of FDI due to the country’s rich endowment of natural resources. Yet, already before the pandemic, the authorities’ efforts to improve the investment climate were not sufficient to fully exploit the country’s FDI potential. FDI inflows have recently declined as a share of GDP and Indonesia’s share in FDI flows into ASEAN has fallen in the past few years. Additionally, with global FDI flows expected to plummet by more than 30% in 2020 (OECD, 2020c), Indonesia has not been spared. Cross-border equity flows have already dropped significantly during 2020 relative to 2019, as companies have put merger and acquisition (M&A) deals and greenfield projects on hold due to rising uncertainty.

Private investment, both foreign and domestic, will need to play an important role in the recovery. Before the pandemic outbreak and following President Joko Widodo’s re-election in 2019, the government set ambitious targets for the year 2045 when Indonesia will celebrate its 100th anniversary as an independent nation. It aims at breaking out of the middle-income trap, to become a developed economy and enter the world’s top five economies with a GDP worth over USD 7 trillion, while also substantially reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In order to achieve these goals, the government has placed private sector development at the centre of its reform agenda and identified the following priorities for the next five years: infrastructure development; human capital development; simplification of regulations; bureaucratic reforms; and economic transformation.

The Indonesian government has an opportunity to further strengthen its reform efforts, in order to build a sound and transparent investment environment that supports a sustainable and inclusive economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on an updated version of the Policy Framework for Investment, this second OECD Investment Policy Review of Indonesia identifies several potential areas for reform and provides policy recommendations for the government to consider. After an overarching background of Indonesia’s development path and summary of the main findings and recommendations (Chapter 1), the review analyses the trends and impacts of FDI on the Indonesian economy and society (Chapter 2), options to re-think the country’s FDI regime (Chapter 3), investment protection and dispute settlement (Chapter 4), policies to promote and enable responsible business conduct (Chapter 5), measures and institutions to promote and facilitate investment, including tax incentives (Chapter 6) and investment policy and regional development in decentralised Indonesia (Chapter 7).

The Policy Framework for Investment (PFI) helps governments to mobilise private investment in support of sustainable development, thus contributing to the prosperity of countries and their citizens and to the fight against poverty. It offers a list of key questions to be examined by any government seeking to create a favourable investment climate. The PFI was first developed in 2006 by representatives of 60 OECD and non-OECD governments in association with business, labour, civil society and other international organisations and endorsed by OECD ministers. Designed by governments to support international investment policy dialogue, co-operation, and reform, it has been extensively used by over 25 countries as well as regional bodies to assess and reform the investment climate. The PFI was updated in 2015 to take this experience and changes in the global economic landscape into account.

The PFI is a flexible instrument that allows countries to evaluate their progress and to identify priorities for action in 12 policy areas: investment policy; investment promotion and facilitation; trade; competition; tax; corporate governance; promoting responsible business conduct; human resource development; infrastructure; financing investment; public governance; and investment in support of green growth. Three principles apply throughout the PFI: policy coherence, transparency in policy formulation and implementation, and regular evaluation of the impact of existing and proposed policies.

The value added of the PFI is in bringing together the different policy strands and stressing the overarching issue of governance. The aim is not to break new ground in individual policy areas but to tie them together to ensure policy coherence. It does not provide ready-made reform agendas but rather helps to improve the effectiveness of any reforms that are ultimately undertaken. By encouraging a structured process for formulating and implementing policies at all levels of government, the PFI can be used in various ways and for various purposes by different constituencies, including for self-evaluation and reform design by governments and for peer reviews in regional or multilateral discussions.

The PFI looks at the investment climate from a broad perspective. It is not just about increasing investment but about maximising the economic and social returns. Quality matters as much as the quantity as far as investment is concerned. It also recognises that a good investment climate should be good for all firms – foreign and domestic, large and small. The objective of a good investment climate is also to improve the flexibility of the economy to respond to new opportunities as they arise – allowing productive firms to expand and uncompetitive ones (including state-owned enterprises) to close. The government needs to be nimble: responsive to the needs of firms and other stakeholders through systematic public consultation and able to change course quickly when a given policy fails to meet its objectives. It should also create a champion for reform within the government itself. Most importantly, it needs to ensure that the investment climate supports sustainable and inclusive development.

The PFI was created in response to this complexity, fostering a flexible, whole-of-government approach which recognises that investment climate improvements require not just policy reform but also changes in the way governments go about their business.

For more information on the PFI, see: www.oecd.org/investment/pfi.htm.

Democratisation and decentralisation have progressed albeit not without challenges

Since the end of the Suharto regime in 1998, Indonesia has been a transparent and accountable democracy. The presidential election held in 2019 was the largest ever, recording an 81% participation rate and the decentralisation process is also continuing with regional development policies now very much in the hands of the four sub-national tiers of government.

From the early 2000s, Indonesia embarked upon a profound and long-lasting decentralisation process, which involved transferring both decision-making and financial resources for the delivery of basic services, such as the provision of transport infrastructure, to local governments. Policymaking started to be shared vertically between central and local governments and decision-making on health, primary and middle-level education, public works, environment, transport, agriculture, and manufacturing shifted to the local level (OECD, 2010).

The speed of the devolution has meant that the required accompanying skills, technical capacities, resources and oversight have sometimes been lacking. As a result, while good progress has been made nationally along a number of dimensions, outcomes in health, education, infrastructure, good governance and the provision of other social services have not improved as quickly as was expected, and the variance in results across regions has been enormous (OECD, 2018a). Conflicting and overlapping laws and regulations across levels of government are also inhibiting regional development by obstructing private business development and investment.

Indonesia has been actively fighting corruption since the early 2000s and good governance has gradually improved as a consequence, but it remains a massive endeavour. Indonesia ranked 85th out of 198 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index in 2019, gradually improving its position from 137th in 2005, 110th in 2010 and 88th in 2015. The Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) was created in 2002 to investigate and prosecute corruption cases and to monitor the governance of the state. Although KPK’s resources and institutional capacities are largely concentrated at the national level, thus leaving the fight against local corruption primarily in the hands of local governments, it has enjoyed a significant degree of autonomy and has been recognised as a leading and successful player in reducing corruption. A new KPK law was passed in September 2019, however, which has the potential to jeopardise the influence and independence of the commission.

Until the pandemic, economic growth had been solid and steady

Until the COVID-19 outbreak, Indonesia’s economic growth record had been strong over the past decades and achieved a significant degree of stability. GDP growth averaged 7% between 1966 and 1996 and approximately 5% in the 2000s and since the global financial crisis (Hill, 2018).

Prudent macroeconomic policies and progress in structural reforms have been driving this strong and continued economic growth. Following the 1998 Asian financial crisis, the government pressed on with economic reforms without resorting to protectionist responses. The number of laws introduced after the crisis was unprecedented. Beyond those covering regional autonomy, new laws were introduced in almost all areas of economic activity, including: investment, labour, arbitration, bankruptcy, company law, competition, tax administration, human rights, mining, oil and gas, geothermal and other energy, and in other infrastructure sectors (OECD, 2010). GDP started to recover in 2000, admittedly less than other Asian countries such as India (7.2%) or Viet Nam (6.5%), accelerating from 2001 to 2005, and then fluctuating until reaching a peak in 2007.

The 2008 global financial crisis did not significantly affect the country, as the growth rate decreased to 4.6% in 2009 but quickly recovered in 2010 to reach 6.2% (Figure 1.1). The remarkable macroeconomic stability since then was possible thanks to a strong macroeconomic policy framework implemented by the government. Prudent fiscal policy has been underpinned by a commitment to a fiscal deficit of no more than 3% of GDP and public debt no higher than 60% of GDP (OECD, 2018a). Bank Indonesia has the mission to stabilise the value of the rupiah and pursue its inflation target, which has until recently been low, maintained at around 3%.

Macroeconomic stability is also dependent on the capacity to finance its current account deficit, which has been a challenge for Indonesia. The current account has been in deficit since 2012, averaging 2.5% of GDP over 2012-19. Tax revenues remain low, including due to the large informal economy (see below) with one of the lowest tax/GDP ratio across countries of the same income category (OECD, 2018a). Low government revenues limit spending, notably on education, health and social protection.

While national and international observers announced encouraging growth prospects for 2020, notably due to the gradual easing of international trade tensions and the renewed political stability, the sudden and dramatic outbreak of the COVID-19 is taking a heavy toll on the world economy, thus affecting Indonesia’s development outlook. The government has mentioned two possible scenarios: a baseline one with GDP growth down to 2.3% and a worst-case scenario with a contraction of 0.4%. The OECD estimates that a severe recession will affect the country with GDP projected to contract by 3.3% in 2020 (OECD, 2020a).1 Employment and income losses are holding back consumption and the socio-economic consequences of the crisis are severe for lower middle class groups. The hardest hit sectors are tourism, retail trade and manufacturing.

As in many OECD countries and beyond, the government swiftly responded with comprehensive and substantial policy actions during the first half of 2020 to support purchasing power and businesses. Bank of Indonesia decided to cut interest rates and the President signed on 1 April a regulation lifting a Constitutional cap on the budget deficit for three years. Successive stimulus packages included the expansion of social protection schemes, strengthening the health sector, food assistance and electricity tariff discounts, tax breaks and incentives for industries, capital injections to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and liquidity support for the banking industry, among others.

The manufacturing sector has been steadily declining as a share of GDP, but there is a gradual shift from the extractive industry to services

The evolving structure of the economy reflects the country’s natural resource endowment and its current development path. Despite a faster growth of services compared to the primary and secondary sectors, the Indonesian economy is still characterised by a low share of services: 43.4% of national value added in 2018, compared to 70.7% in OECD countries (in 2017) and 53.8% of GDP in other middle-income countries. Industry – including construction, manufacturing and mining – accounted for almost 39% in 2019.

Indonesia is a natural resources rich economy and agriculture thus remains a key contributor to GDP, accounting for 13% in 2019. With 30% of the total workforce, the primary sector remains the greatest employer (Lewis, 2020). Indonesia is the world’s largest producer of palm oil and provides about half of the world’s supply. It is also the second-largest rubber producer in the world. When counting mining products as well (e.g. coal, copper, oil), natural resources accounted for 20% of GDP and 50% of exports in 2017 (OECD, 2019a). Both the productivity level and productivity growth rate in the primary sector are low, however.

The value added of manufacturing2 in Indonesia steadily increased from 1985 until the Asian financial crisis, thanks to the government’s efforts to stimulate investment, including FDI, which generated strong economic growth (ADB, 2019a). The sector then suffered from the crisis, unlike in some other ASEAN countries and its contribution to GDP has thus been declining since then (Figure 1.2). It dropped from over 27% of GDP in 2005 to less than 20% in 2018, which represents an important drop for a middle-income economy. As the manufacturing sector is still undiversified, the country exports relatively few products with comparative advantage (ADB, 2019a). Currently, the manufacturing sector – particularly the textile industry – is one of the most hit by the COVID-19 crisis. In April 2020, only one third of manufacturing firms and workers were operational (OECD, 2020b). Throughout all economic sectors, job losses since mid-March have exceeded 2.8 million.

Indonesia’s exports are driven by minerals and food products, as well as textiles and apparel. Exports have stagnated since 2007, both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP, and represent a declining segment of the economy.3 In the face of the pandemic, international trade figures are not as alarming as in other countries, as Indonesia is less exposed to the disruption of global value chains. Manufacturing companies are, however, heavily reliant on inputs imported from China (OECD, 2020b).

Manufacturing growth is also hampered by the comparatively small size of firms in Indonesia. The majority of firms are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (92-99%), which employ the bulk of the domestic workforce (58-91%). Yet they represent only about a third of total value added and their contribution to trade remains limited (Lopez-Gonzalez, 2017). The number of large enterprises in Indonesia (5 066 in 2016) is low given the size of the economy, contrasting with 7 156 large enterprises in Thailand and 13 813 in Malaysia (OECD, 2018b). This is even stronger in the manufacturing sector – 99% of manufacturing firms being micro and small enterprises – which is an impediment to the technological transformation of the Indonesian economy, as such firms suffer lower productivity and have little capability to adopt and use new and digital technologies (ADB, 2019b).

Recognising the challenges of the manufacturing sector and the opportunities provided by new technologies, the government recently developed a strategy called Making Indonesia 4.0 aimed at revamping the industrial sector and increasing labour productivity. It focuses on technology and productivity upgrades in five manufacturing industries: food and beverages, textiles and garments, automobiles, electronics, and chemicals. With the service sector gradually playing a more important role, Indonesia seeks to increase the digitalisation of all economic sectors and to position itself as a regional hub for the digital economy. This has become an even stronger trend in the context of the COVID-19 crisis.

Continued growth has reduced poverty, but improving the quality and competitiveness of human resources is necessary

Indonesia’s recovery from the 1997 Asian financial crisis and its solid growth since then has led to an impressive reduction in poverty. Poverty rates fell sustainably from 19% of the population in 2000 to just over 9% in 2019 (World Bank, 2019b). A significant improvement in living standards has also been recorded since the Asian crisis, as GDP per capita has risen by 70% during the past two decades and per capita income has increased by almost 4% annually (OECD, 2018a). Efforts by the government to expand social assistance programmes, deployed since 2000, also contributed to those achievements.

The decline in poverty slowed significantly after 2010, however, with 38% of the population remaining poor or vulnerable in 2016 (OECD, 2019c). Inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, also rose over the past decades, from 30 points in 2000 to 41 in 2015, then declining to 38.2 at the beginning of 2019 (World Bank, 2019a). Despite this recent slight decline, Indonesia continues to record greater inequalities than Thailand (36.4 in 2018) and Viet Nam (35.7). Regional inequalities are also significant in Indonesia, as the five poorest provinces are located in the east, and their poverty rates in 2016 were, on average, 18 percentage points higher than the average for the five wealthier provinces (OECD 2019c). These inequalities in population and regions are likely to increase due to the COVID-19 crisis.

The Indonesian economy remains dominated by a large informal sector accounting for approximately 70% of national employment and more than 90% of total businesses (OECD, 2018b). While labour productivity is above the ASEAN average,4 the extent of the informal sector leads to low quality jobs with lower productivity. Informal workers (and their families) often find themselves in the “missing middle” of social protection coverage, whereby they are ineligible for poverty-targeted social assistance but excluded from employment-based contributory arrangements.

While Indonesia’s elderly population is expected to grow rapidly, its youthful population is an opportunity. Half of the population is under 30 years old and the demographic dividend is still adding to economic growth. Since 2002, Indonesia embarked on a deep reform of the educational system. Indonesia’s spending on education has been increasing over time (from 2.8% GDP in 2010 to 3.6% in 2015 according to UNESCO) and is now comparable to other emerging markets such as Malaysia, South Africa and Thailand. Indonesia is approaching universal completion of primary school (OECD, 2018a).

Despite those achievements in terms of coverage, low quality of education remains a concern, as it is holding back growth in Indonesia, with many students lacking basic skills. The OECD’s 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results put Indonesia near the bottom, with a deterioration compared to 2015 (OECD, 2019b). Indonesian 15 year-old students ranked in the bottom 10 out of the 79 countries tested in mathematics, reading and science. Teachers are often poorly qualified and absenteeism is high. Unemployment rates of medium and high-skilled 20-29 year-olds are 6 percentage points higher than for the low skilled. This can be largely explained by the poor quality of education (OECD, 2016; OECD/ADB, 2015). It contributes to informality, as workers do not have the skills for higher-paying formal sector jobs, which is also fuelled by the relatively strict employment regulation. In this context, the government recently passed the Omnibus Law on Job Creation, which, among other objectives, seeks to introduce more flexibility in the labour market; however, its concrete implementation and outcomes remain uncertain. It will be particularly important to consider social impacts of business operations in the context of the new Omnibus Law on Job Creation as well (see below).

Improving the business environment stands high on the government’s agenda

Indonesia has been seeking to make the private sector, both domestic and foreign, the engine of growth and sustainable development. The government has been active in improving the business environment since the late 1990s – and increasingly so since President Widodo took office. In the 2000s, efforts focused predominantly on legislative changes. The number of new laws increased dramatically in all economic areas, including investment. The 2007 Investment Law unified the previously distinct foreign and domestic investment laws and increased the transparency of Indonesia’s policy framework for investment, including by clarifying which sectors are closed to foreign or domestic investors (OECD, 2010).

More recently, since President Widodo’s re-election in 2019, there is an even bigger push for business climate improvements, as the simplification of regulations and de-bureaucratisation have been placed among the top five priorities of the newly-formed Cabinet. Recognising that high administrative costs reduce productivity and are an avenue for corruption and informality, the government initiated business licensing and investment facilitation reforms aiming at easing the process of starting and operating a firm. Successive measures were implemented to improve transparency, streamline licences and facilitate the process to start a company.

The establishment of regional one-stop integrated services centres (i.e. PTSPs), and, later on, the introduction of the Online Single Submission (OSS) system were steps in the right direction to improve the business licensing process throughout the country. The authorities also took measures to improve regulations related to business competition, including through the Indonesian Competition Commission (KPPU). In 2019, KPPU focused on reforming procedural law, easing notification of merger and acquisition transactions, and improving legal protection for SMEs. Reflecting these improvements, the country ranked 73rd out of 190 economies on the World Bank Ease of Doing Business indicator in 2020. Its position in the Starting a Business category remained much lower, however, at 140th place.

In October 2020, the Parliament enacted the Omnibus Law on Job Creation, which aims to streamline the current regulatory framework for investment and includes key measures ostensibly lifting restrictions and conditions placed on FDI, centralising and simplifying business licensing and land acquisition procedures, significantly reforming Indonesia’s labour market and relaxing certain environmental regulations. The law, which is repealing 76 laws and over 1000 articles, is perceived by the government as critical to strengthen economic competitiveness, revitalise the manufacturing sector and ultimately pave the way for Indonesia to avoid the so-called ‘middle income trap’.

While it is premature to analyse the full impact of the law until implementing regulations are finalised, the law encompasses significant business-friendly reforms, such as liberalising FDI and easing the process to start and operate a business. It has nevertheless also drawn criticism from environmental and social groups about its effects on the environment and the labour market, including concerns about how environmental permits would be structured as well as the extent of deregulation affecting working conditions and pay. In addition to non-governmental organisations and trade unions, some institutional investors called on the government to support the conservation of forests and peatlands; uphold human rights and customary land rights of indigenous peoples; hold proper consultations with environmental and civil society groups and investors on the law and its implementation; and take a long-term approach to recovery from the pandemic.

The government seeks to addresses infrastructure gaps impeding business environment improvements

Infrastructure gaps remain a major development challenge in Indonesia and rank high on the government’s agenda. According to the previous medium-term plan (2015-19), infrastructure needs are equivalent to 7% of GDP each year. Indonesia ranks 72 out of 141 countries in terms of infrastructure development in the World Economic Forum (WEF)’s Global Competitiveness Report 2019, behind other ASEAN countries including Singapore (1st), Malaysia (35th) and Thailand (71st) (WEF, 2019). This index reveals large gaps in various types of infrastructure: road connectivity is very poor (109th) and so is utility infrastructure (89th). On the other hand, air transport infrastructure performs well (5th in terms of airport connectivity), although the capacity at the two main airports is fully utilised. Access to electricity is still constrained and gaps also remain in waste, water, sanitation and sewerage facilities.

The government is aware of the importance of the quality and quantity of infrastructure in fostering inclusive growth. It set targets in the 2020-24 plan in terms of infrastructure for drinking water, sanitation facilities as well as infrastructure to support economic development (toll roads, roads, bridges) and to improve connectivity. In Jakarta, infrastructure improvement actions are being implemented to ease congestion and reduce pollution, such as the March 2019 inauguration of the first metro line.

Although the government puts both infrastructure development and the improvement of the business environment high on its agenda, the private sector does not yet play an important role in filling the infrastructure gap (OECD, 2018a, 2019a). Infrastructure investment relies heavily on public finance, with the government accounting for 55% of total infrastructure investment in 2015 while the private sector contribution declined to 9% over 2011-15 (OECD, 2019a).

Additionally, while SOEs operate in almost all sectors of the economy – ranging from manufacturing and construction to agriculture and finance – they play a particularly important role in infrastructure, notably transport (OECD, 2018a). Listed SOEs represent almost one-quarter of equity market capitalisation. SOEs have been hard hit by the pandemic and the National Economic Recovery programme includes new injections of capital into certain SOEs, including SOEs operating in infrastructure, to prevent them from defaulting on their debt obligations.

As Indonesia addresses the infrastructure gap, it will also be important to integrate due consideration of possible negative environmental and social impacts of projects in the risk calculus, and not only remain at the level of financial risks. Responsible business conduct principles and standards are of particular relevance in this regard.

Despite a recent reduction of the deforestation rate, pollution and deforestation still threaten sustainability

As the most populous country and the largest economy in Southeast Asia, Indonesia faces the complex challenge of improving living conditions for its growing population while addressing environmental pressures that, if left unchecked, could deter growth and development (OECD, 2019a). Indonesia faces serious environmental challenges related to air and water pollution, waste management, climate change, biodiversity loss and depletion of natural resources, which result from its rapid economic development, urbanisation and the rising global demand for commodities. While private investment – both domestic and foreign – can, in some cases, be at the source of pollution problems, especially if conducted without due diligence, it can also be a significant conduit for the transition to a low-carbon and energy efficient economy. In this context, it will be important to consider environmental impacts of business operations in the context of the new Omnibus Law on Job Creation.

Although deforestation has slowed since 2015 in Indonesia, intensive fires in peat lands continue to be used to clear large tracts of forest, including for the development of oil palm plantations, pulp and paper industry as well as logging. This has contributed to Indonesia losing forest cover rapidly, declining by 7% between 2005 and 2015, the second highest forest loss worldwide after Brazil (OECD, 2019a). A moratorium on new concessions for plantations and logging of primary forests and peatlands has been in place since 2011, but experts consider that it has not been fully effective (Austin et al., 2017; Busch et al., 2015). In 2018, the President signed a three-year moratorium on new licences for oil palm plantations. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has been worsening deforestation in Indonesia, as the lockdown did not allow sufficiently active forest monitoring and management. It is estimated that 1300 square kilometres of forests were lost in March 2020, an increase by 130% as compared to the average of the March months in 2017-19 (WWF, 2020).

Indonesia is among the world’s ten largest greenhouse gas emitters and its emissions continue to be on the rise (OECD, 2019a). The government aims to play an important role in addressing climate change. Nevertheless, the current five-year plan (2020-24) sets the targets for greenhouse gas emissions: 29% unconditional reduction and 41% reduction relative to baseline with international support by 2030. Transport, especially by road, and coal-fired power generation are major drivers of the surge in emissions (Yudha, 2017). The number of vehicles in use almost tripled over 2005-15 while Jakarta has become the third-most congested city in the world (OECD 2019a). Rapid deforestation is also exacerbating greenhouse gas emission, as the land-use sector accounted for about half of the country’s total emissions over the past decade.

Marine plastic waste has also increased markedly. Indonesia is the second largest contributor to seaborne plastic pollution and 70% of its coral reefs (18% of the world total) are in moderate (35%) or bad (35%) condition (OECD, 2019a). Additionally, the high concentration of population and economic activity on the island of Java (around 56% of the population and 7% of the land area) creates environmental and infrastructure challenges. Excessive subterranean water extraction in Jakarta is causing land subsidence and increasing the risk of flooding; traffic jams and urban air pollution are amongst the worst in the world (OECD, 2019a). This has prompted the government to embark upon the ambitious project to move the capital city from Jakarta to Kalimantan.

Besides providing a source for financing, FDI may bring significant advantages to the host country. It can raise productivity, support integration in global value chains (GVCs), create decent jobs, contribute to the development of human capital and the diffusion of cleaner technologies, and bring gender-inclusive work practices. Recognising the specific role played by foreign investment in economic development, the government of Indonesia has been increasingly seeking to attract FDI to respond to the country’s most pressing needs in terms of unemployment, regional disparities, infrastructure, human resource development and economic transformation.

Indonesia has the potential to be a key FDI destination in ASEAN, but investment climate reforms will make it more competitive

FDI as a share of GDP in Indonesia has fluctuated over time, reflecting changes in both domestic and external conditions. Since 2004, FDI as a share of GDP has grown significantly, although it has declined recently. Being by far the region’s largest economy, Indonesia has historically been a relatively important FDI destination in ASEAN, however its share in the region’s FDI inflows has fallen in the past few years (Figure 1.3). Rising global uncertainties have contributed to lower FDI inflows, which are expected to decline further due to the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing global economic crisis. Cross-border equity flows in Indonesia have already dropped significantly during 2020 relative to 2019, as companies have put some M&A deals and greenfield projects on hold due to rising uncertainty.

The largest share of FDI during 2010-19 went to manufacturing, although the share is declining and services have received increasing flows (Figure 1.4). The primary sector also attracts a large share of FDI due to the country’s rich endowment of natural resources. Greenfield FDI projects are prevalent in manufacturing, while M&A deals are mainly concluded in the primary and services sectors. The bulk of FDI to Indonesia originates in Singapore and Japan. Investment from Singapore is, however, likely to be inflated, as foreign enterprises, including from OECD countries, may choose to invest through their Singapore affiliates.

FDI contributes to sustainable development but its impact can be enhanced

The first OECD Investment Policy Review of Indonesia released in 2010 showed that FDI played a major role in raising employment and productivity and in generating exports in Indonesia prior to the global financial crisis. FDI could thus make an important contribution to a sustainable and inclusive recovery of Indonesia in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting social and economic crisis. Long term development priorities to build a more resilient and sustainable economy include boosting productivity and innovation; strengthening skills; creating more and better jobs; enhancing gender parity; and the transition to a low-carbon and energy efficient economy.

This second OECD Investment Policy Review of Indonesia finds that foreign firms directly contribute to several sustainable development objectives of Indonesia. They are more productive, have higher employment ratios, and pay higher wages than Indonesian firms. They also export a higher share of their production and generate important multiplier effects on the domestic economy.

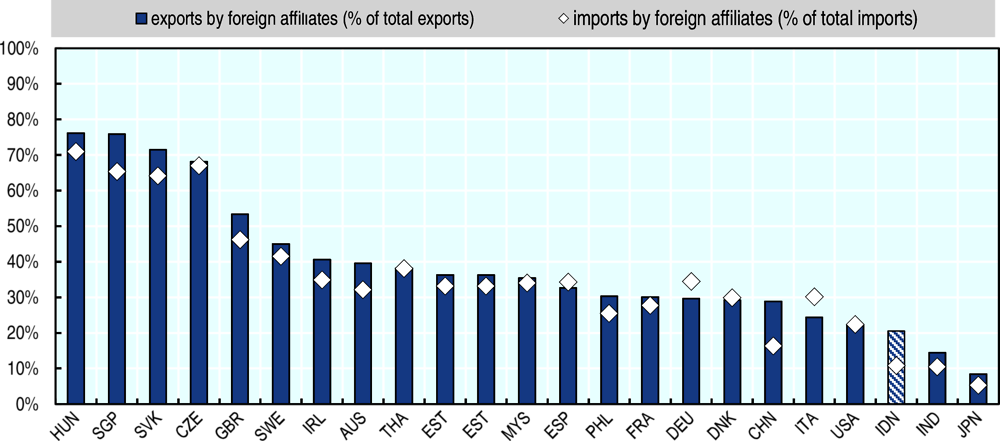

While foreign firms usually participate in GVCs, Indonesia is less integrated in GVCs than other countries in the region. It has a lower export orientation and a lower share of foreign value added in gross exports, and foreign firms contribute less to domestic value added relative to other countries. Its level of GVC participation is nevertheless similar to that of other economies with large domestic markets, such as India, China and the United States, or rich in natural resources like Australia. Additionally, foreign firms in Indonesia contribute less to gross exports and imports in comparison with other countries in the region (Figure 1.5). This is due to fact that Indonesia attracts a large share of resource-based and market-seeking, as opposed to export-oriented, FDI.

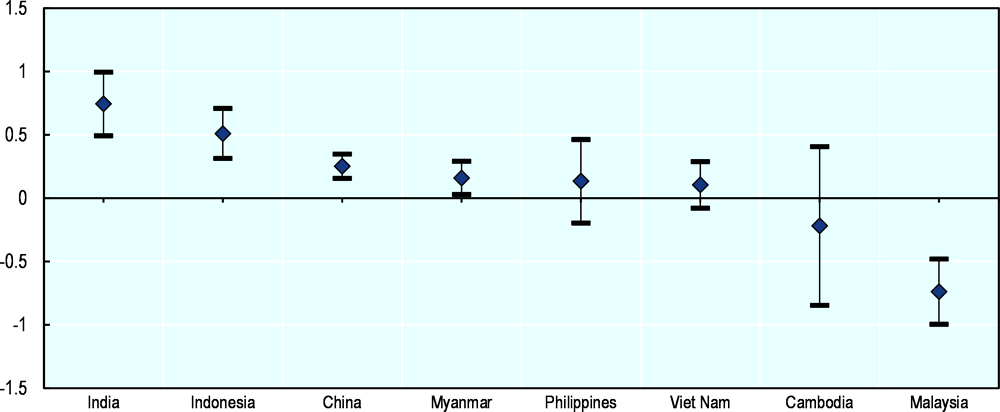

FDI supports productivity gains within the economy. It is concentrated in sectors that are relatively more productive, namely mining, energy, transport services and chemicals. Across most sectors, foreign firms are more productive and are more likely to invest in research and innovation (R&D) or to introduce a new product or process innovation relative to their domestic peers (Figure 1.6). While this confirms the direct contribution of FDI to sustainable development, it also points to gaps in domestic capabilities, which reduce the chances for technology transfer from foreign to domestic firms and positive productivity spillovers. On the other hand, business linkages between foreign and domestic firms are significant. Although the large extent of linkages observed in Indonesia is partly explained by local content requirements in a variety of sectors, including mining, transport equipment and electronics, this could suggest that the potential for productivity spillovers is high.

FDI influences different labour market outcomes in opposite ways. FDI is concentrated in sectors with relatively higher wages (mining, energy, transport services), but with lower levels of female participation. In most sectors, foreign firms pay higher salaries than domestic firms (Figure 1.7). They are also more gender-inclusive, as they employ a larger share of female workers and are more likely to be run or owned by women. Foreign and domestic firms employ comparable levels of skilled labour and report similar difficulties in hiring qualified labour.

FDI also contributes to Indonesia’s environmental targets in contrasting ways. Foreign investors tend to locate in sectors that are more polluting in terms of CO2 emissions, but they are more energy-efficient than domestic firms (Figure 1.8). While the share of FDI in renewable energy is still comparatively low, inflows in clean energy infrastructure are increasing rapidly.

Considerable and steady economic and social progress has been achieved in recent years. This has laid the foundation for further steps to foster investment climate reforms in support of Indonesia’s ambitious national development targets and to achieve a resilient economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. But these policies have yet to demonstrate the intention to establish a clear role for FDI in Indonesia’s economic, social and environmental development ambitions, and make it an attractive destination for investors in the aftermath of the pandemic. This is a similar story when it comes to private sector contributions to the sustainable development goals.

Divergent forces are trying to influence the policy choices. On the one hand, there is a desire to protect the local economy from foreign investment, on the other a willingness to undertake deep reforms to further benefit from FDI. Resource nationalism is still prevalent in public opinion, and SOEs continue playing an important role in economic development.5 Government efforts on transparency, the rule of law and the quality of institutions have been notable, but they have not been sufficiently consistent to improve investors’ confidence and ensure responsible business practices by both foreign and domestic companies. Roles and responsibilities across ministries on investment issues tend to be unclear and sometimes lack co-ordination. The decentralisation dimension makes it even more challenging to conduct consistent and efficient investment policymaking, as well as to address the environmental and social impacts of business operations.

Based on an updated version of the Policy Framework for Investment, this second OECD Investment Policy Review of Indonesia identifies several potential areas for reform to build a sound and transparent investment environment to support a resilient recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. The section that follows summarises the findings and assessments from each of the subsequent policy chapters of this Review. The numerous policy options mix concrete measures that can be implemented relatively quickly and more aspirational recommendations, which will require more fundamental changes in the way the government goes about its business. Some measures can only be implemented over a long time horizon, while the government is already considering others. The aim is to provide a list of policy options for the Indonesian government to consider as it reforms it investment climate.

Indonesia’s approach towards FDI needs to be more open

Indonesia has a number of attributes that makes it a naturally coveted destination for FDI: the largest consumer market of Southeast Asia in one of the world’s fastest-growing regions, abundant natural resources and a large and relatively young workforce. Yet, it has never really taken off as a leading location for FDI, especially considering the increasing importance of Southeast Asia as a global investment destination. Foreign investors have been somewhat timorous of Indonesia’s complex business environment, not least because of remaining FDI restrictions and entry conditions. The recent Sino-US trade tensions, which led to the relocation of some export-oriented investments out of China, once again drew attention to Indonesia’s challenges in attracting FDI although more recently some factories have announced plans to relocate production to Indonesia (JETRO, 2020; Nomura, 2019; Jakarta Post, 2020a, 2020b). The situation prompted a strong reaction from President Joko Widodo, who called out members of his cabinet for the country’s failure to capture a ‘fair share’ of such relocations (Jakarta Globe, 2019; Katadata, 2019).6

Increasing foreign investments and improving the ease of doing business became a key priority for the current administration, which enacted in October 2020 the Omnibus Law on Job Creation aimed at streamlining and repealing dozens of overlapping regulations considered to be hampering investments and job creation. The law was passed despite strong opposition by labour unions, regional administrations and civil society, who expressed concerns over the law’s amendments to the 2003 Labour Law, the recentralisation of administrative power in the hands of the executive and the lack of public hearings among other things – seeks to lift restrictions and conditions placed on FDI, centralise and streamline business licensing and land acquisition procedures, including by adopting a risk-based approach to business licensing and making it a more transparent and fully online process, and significantly reform Indonesia’s labour market. Implementing such an ‘all-in-one’ law reform package will be a challenge, and possibly not all of its content is truly desired (see also Chapter 5) despite the compelling arguments for revising the current FDI regulatory regime once the pandemic is controlled.

Over time, Indonesia has significantly liberalised its foreign investment regime, although it is still one of the most restrictive countries to FDI as measured by the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, with many primary and services sectors still partly off limits to foreign investors (e.g. agriculture, fisheries, oil & gas, power, construction, hospitality, distribution, transport, telecommunications insurance and other financial services). Beyond extensive sector-specific foreign equity restrictions, it maintains a range of discriminatory policies that apply across the board, such as higher minimum capital requirements for foreign-invested companies, stringent conditions on the employment of foreigners in key management positions, limitations on branching and access to land by foreign legal entities and preferential treatment accorded to Indonesian-owned entities in public procurement. Indonesia also makes extensive use of local content requirements, which add to the hurdles of carrying out foreign investments in Indonesia. It remains to be seen how the recently enacted Omnibus Law on Job Creation will change the situation.

In addition to diverting potential FDI away from Indonesia and depriving the country of a relatively more stable source of capital and foreign exchange for financing a structural current account deficit than is provided by portfolio investments, these restrictions contribute to holding back potential economy-wide productivity gains (OECD, 2018c; Duggan et al., 2013; Rouzet and Spinelli, 2016). As can be seen in Chapter 3, manufacturing industries in Indonesia are among the most affected worldwide by restrictions to FDI in services sectors. By limiting competition and contestability, notably in services sectors, they prevent access to world class services inputs by downstream industries and consumers. In the modern context of intensified regional and GVCs, FDI policies can no longer treat services and manufacturing separately.

Beyond these more fundamental reasons, tapping into a larger pool of FDI than previously the case might be ever more critical for the economic recovery following the pandemic, which is projected to significantly weaken Indonesia’s real GDP growth (see Figure 1.1). Typically larger and more geographically diversified and productive, foreign-owned firms are overall more resilient to crisis. Therefore, they could potentially be an asset to reignite recovery earlier or faster. In addition, at a time of record-high portfolio capital outflows from emerging markets, FDI could help to ease any possible financing pressure on Indonesia’s current account deficit, which is projected to widen once again on the back of sluggish tourism exports and commodity markets.

A comprehensive overhaul of Indonesia’s FDI regime may not be easy to achieve, but only a bold and comprehensive reform package would allow Indonesia to significantly reduce barriers to FDI and increase its relative attractiveness as an investment destination. Out of six hypothetical FDI reform scenarios simulated using the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, only the elimination of all sector-specific foreign shareholding restrictions, all other restrictions held constant, could bring Indonesia significantly closer to OECD levels of openness. The impact of substantial FDI liberalisation can be sizeable (Mistura and Roulet, 2019). Indonesia’s inward FDI stocks, for instance, could be 25% to 85% higher if it were to reduce the level of FDI restrictiveness to the 50th and 25th percentile levels of the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, all else held equal. Stringent barriers to FDI also imply that reforms which ease the costs of doing business may not bring about the intended benefits.

While revisiting the FDI regime is certainly warranted, the Omnibus Law on Job Creation should also ensure that past achievements are preserved. The transparency of Indonesia’s policy framework for investment improved with the adoption, pursuant to the 2007 Law on Investment, of a ‘negative list’ approach for listing sectors that remained closed or open with certain conditions to foreign or domestic investors. A shift to a ‘positive list’, as it has sometimes been reported by the media, would represent a setback to transparency and on-going and future efforts of maintaining an open business environment if technically implemented. The authorities, however, have confirmed during this review that the ‘negative list’ approach will continue to be used for the regulation of market access. Improvements could thus be considered on the institutional setting and procedures for its formulation. Greater transparency and technical support, as well as a more inclusive consultation and institutional setting could help to broaden the information-base supporting discussions and deliberations in this regard.

The current global economic downturn might perhaps work in favour of pushing reforms forward. The pace of Indonesia’s FDI reforms has historically been largely shaped by crises. If it were not for the current unique situation, past perspectives about FDI liberalisation reforms would be comforting in suggesting a pick-up in FDI activity. But this time, even holding on to existing FDI may prove difficult given the expected negative impact of the pandemic on global FDI activity (see Chapter 2). ASEAN as region is likely to remain well positioned to compete for investments, which could also benefit Indonesia. Without reforms, however, Indonesia remains at a relative disadvantage and the chances of attracting needed FDI in the aftermath of the pandemic may be slim.

Main policy recommendations

In view of Indonesia’s ample list of activities restricted to foreign investment: undertake a comprehensive regulatory impact assessment of existing restrictions on FDI, including assessments of potential alternative, non-discriminatory policies where relevant, and subject the assessment to ample stakeholder scrutiny to identify priority areas for reform and inform policymaking in the context of the omnibus reform on job creation and further implementing regulations.

In advancing FDI reforms, consider prioritising further liberalisation of FDI in services sectors due to their economy-wide productivity implications. In the current context of GVCs and the intensified ‘servicification’ of manufacturing activities, restrictions on FDI in service sectors end up discriminating against domestic manufacturing producers and consumers, who may have to pay relatively higher prices for quality-adjusted services inputs. Accompanying reforms to behind-the-border services regulations should go hand in hand with FDI liberalisation for these to fully bring about their potential benefits.

Eliminate discriminatory requirements against foreign direct investors in horizontal regulations to support enhanced competitiveness and efficiency and ensure a level playing field for all investors in Indonesia. In this respect:

Align the general minimum capital requirement for foreign-invested companies with capital requirements for domestic investors. The current discriminatory minimum capital policy is particularly stringent for investors in less-capital intensive activities. Worldwide, where minimum capital requirements still exist, they are rarely discriminatory – in 2012 only eight countries out of 98 assessed in the World Bank’s Investing Across Borders imposed a discriminatory minimum capital requirement – and typically much lower than what is required from foreign investors in Indonesia (about 17 times lower for the average OECD economy). This is the case even across economies with a level of income per capita much greater than that of Indonesia.

Promote a more level playing field in public procurement for foreign direct investors by eliminating preferential treatment accorded to Indonesian-owned entities, notably in the procurement of services. According preferential treatment to resident enterprises in public procurement is relatively common, but discriminating against foreign-owned firms established in the procuring jurisdiction is rather exceptional. As for other discriminatory measures, these might hinder competition and contestability in the affected markets and may drive up costs of goods and services procured by the government.

Reconsider the use of local content requirements for developing local industries and supporting domestic investors. Stringent local content requirements in some sectors add to the hurdles of carrying out foreign investments in Indonesia. By establishing hard to achieve local requirements, it may restrain competition and potential short-term gains in targeted industries and can act as a drain on the rest of the economy. In pursuing such objectives, horizontal policies addressing deficiencies of the business and regulatory environment, trade and investment barriers, innovation policy, and infrastructure development, can offer an alternative to local content policies and have less negative economy-wide effects on output, exports and jobs.

Preserve and improve Indonesia’s current ‘negative list’ approach to regulating market access and treatment accorded to foreign investment in the on-going Omnibus law reform. Such an approach provides greater clarity and security for investors than the alternative ‘positive list’ approach sometimes mentioned in the context of the on-going reform. Investors have at times expressed discontent with the pace of liberalisation in past years and questioned the capacity of the ‘negative list’ revision process to encourage liberalisation, but this would likely be more challenging under the alternative ‘positive list’ proposal. Improvements could be considered, instead, on the institutional setting and procedures for the regular revision of such a ‘negative list’. In these respects:

Continue to allow foreign investment without discrimination unless designated as restricted in a separate ‘negative list’ indicating a complete list (without carve-outs and exceptions) of activities closed to private investment (foreign or domestic), activities closed only to foreign investors, and activities where foreign investment is permitted under discriminatory conditions. Such a list should be clear and concise, describing any imposed condition with clarity and specifying where appropriate the relevant underlying provisions in national laws and regulations. Explicit reference to an international standard industry classification (on top of Indonesia’s standard industrial code (KBLI) as currently the case) for accurate documentation of closed or restricted activities is also recommended. As currently the case, it should continue to be placed in an executive-level order for ease of amendments over time. It should also be immediately updated whenever any relevant underlying legislation is introduced or modified to make sure every new or modified restriction and condition is not enforceable until appropriately reflected in the ‘negative list’.

Strengthen the process for assessing and revising the ‘negative list’ on a regular basis including by consulting more amply and systematically with relevant stakeholders, relying more on technical assessments by independent qualified institutions and publicising relevant documents supporting deliberations. A broader involvement of relevant stakeholders, as well as more transparency and technical inputs to the formulation of the ‘negative list’ would help to broaden the information-base supporting discussions and deliberations and facilitate dialogue with interested stakeholders, ultimately contributing to improved policy-making.

Indonesia’s investment protection and dispute resolution have improved but need further reforms to build investor confidence

Rules that create restrictions on establishing and operating a business in Indonesia are an important part of the broader legal framework affecting investors. Protections for property rights, contractual rights and other legal guarantees, as well as efficient enforcement and dispute resolution mechanisms, are equally important elements.

Indonesian law provides a number of core protections to investors relating to non-discrimination, expropriation and free transfer of funds. Most of them are found in the Investment Law (Law 25/2007) and have not changed significantly in recent years. These protections are generally in line with similar provisions found in other regional investment laws and provide clear rights that should instil investor confidence to the extent that enforcement mechanisms are also seen to be robust. Some incremental improvements may be possible to bring these provisions closer in line with international good practices, including further specification of the provisions on expropriation.

Clarifications may also improve the existing legal frameworks to protect investors’ intellectual property and land tenure rights, which are comprehensive in many respects. The government has not made significant updates to land laws in Indonesia in several decades. While foreigners are now able to own land, these rights are relatively limited and interactions between formal land laws and customary land rights remain complex and subject to interpretation. Initiatives to accelerate land registration and the use of electronic databases for land administration have yielded promising initial results but sustained momentum is needed for these changes to be durable in the long term. Investors also report some issues with the legal framework for intellectual property rights, notably with respect to restrictive patentability criteria, but in the main these laws are well-developed, have been periodically improved through amendments and comply with international standards in five core areas: trademarks, patents, industrial designs, copyrights and trade secrets. Some problems nonetheless persist in practice. Online piracy and counterfeiting are widespread, and efforts to implement and enforce laws is poor or inconsistent in several areas. The government is pursuing a range of different initiatives that seek to address these well-known shortcomings.

In terms of dispute resolution, the Indonesian courts have a reasonable record concerning the rule of law and contract enforcement when compared to similar economies. Despite important reforms to establish an independent judiciary and improve court services, however, some stakeholders still cite concerns with the lack of transparent and fair treatment in the Indonesian court system. The effectiveness of the courts is hampered by some long-standing negative perceptions. For these reasons, many firms prefer to use alternative dispute resolution rather than litigation to settle their disputes. Law 30/1999 on Arbitration and Alternative Dispute Resolution provides a solid framework to support arbitration in Indonesia and works reasonably well in practice. The government is not considering any major reform proposals in this area but it may wish to investigate amending some provisions of the law to improve legal certainty.

Other areas attracting attention from the top levels of government are data protection and cybersecurity, the fight against corruption and public sector reforms. The government has taken significant strides towards making cybersecurity a national policy priority. It established a national cybersecurity agency in 2017 and stepped up its international engagement on these issues, but there is still no overarching regulatory framework in Indonesia for cybersecurity or data protection. Fighting corruption in all levels of society has also been a top priority for many years. KPK has played a major role in building public awareness and trust through impressive results, including conviction of high-ranking government officials. A wide range of public sector reforms introduced in recent years to improve transparency, reduce bureaucracy, and encourage public engagement in the policy cycle are also contributing to strengthening public integrity. The causes of corruption are deep-rooted, however, and may only be overcome in the long term, which the government recognises and seeks to address.

The government has also substantially revised its investment treaty policies in recent years. Indonesia’s investment treaties grant protections to certain foreign investors in addition to and independently from protections available under domestic law to all investors. Domestic investors are generally not covered by these treaties. Indonesia is a party to 37 investment treaties in force today. Like investment treaties signed by many other countries, these treaties typically protect investments made by treaty-covered investors against expropriation and discrimination. Provisions requiring “fair and equitable treatment” (FET) are also common, providing a floor below which government behaviour should not fall. While there are some significant recent exceptions, investment treaties often enforce these provisions through access to investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms that allow covered investors access to impartial international arbitration that awards monetary damages in an effort to depoliticise such disputes.

Investment protection provided under investment treaties can play an important role in fostering a healthy regulatory climate for investment. Expropriation or discrimination by governments does occur. Investors need some assurance that any dispute with the government will be dealt with fairly and swiftly, particularly in countries where investors have concerns about the reliability and independence of domestic courts. Government acceptance of legitimate constraints on policies can provide investors with greater certainty and predictability, lowering unwarranted risk and the cost of capital. Investment treaties are also frequently promoted as a method of attracting FDI which is an important goal for many governments. Despite many studies, however, it has been difficult to establish strong evidence of impact in this regard (Pohl, 2018). Some studies suggest that treaties or instruments that reduce barriers and restrictions to foreign investments have more impact on FDI flows than bilateral investment treaties (BITs) focused only on post-establishment protection (Mistura et al., 2019). These assumptions continue to be investigated by a growing strand of empirical literature on the purposes of investment treaties and how well they are being achieved.

The government’s comprehensive review of its investment treaties in 2014-16 led to the termination of at least 23 of its older investment treaties. But like many other countries, Indonesia still has a significant number of older investment treaties in force with vague investment protections that may create unintended consequences. Many countries, including Indonesia, have substantially revised their investment treaty policies in recent years in response to these concerns as well as increased public questioning about the appropriate balance between investment protection and sovereign rights to regulate in the public interest and the costs and outcomes of ISDS. The government is well aware of these ongoing challenges. It is taking a leading role in multilateral discussions on ISDS reform in UNCITRAL’s Working Group III and updating its model investment treaty in light of recent treaty practices. Experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic may further shape how the government views key treaty provisions or interpretations and how it assesses the appropriate balance in investment treaties.

Notwithstanding the potential benefits of having signed international investment agreements, they should not be considered as a substitute for long-term improvements in the domestic business environment. Any active approach to international treaty making should be accompanied by measures to improve the capacity, efficiency and independence of the domestic court system, the quality of a country’s legal framework, and the strength of national institutions responsible for implementing and enforcing such legislation.

Main policy recommendations for the domestic legal framework

Amend Article 7 of the Investment Law to provide further specification on investor rights to protection from unlawful expropriation and the government’s right to regulate. Issues for possible clarification include whether investors are protected from indirect expropriation, exceptions to protect the government’s right to regulate in the public interest, and the valuation methodology for determining market value of expropriated property. This is not necessarily urgent but the government may wish to identify an appropriate opportunity to propose incremental improvements to this and other aspects of the Investment Law.

Consider updating and modernising existing land laws. Land policy is one of the few areas affecting investors where the government has not enacted significant new legislation in recent decades. The existing system for land tenure is based primarily on legislation enacted in 1960. New laws could clarify existing categories of land tenure rights and reduce conflicts between customary and formal laws. Efficient land administration services go hand-in-hand with clear legal rights. The government should also allocate sufficient funds, institutional capacity and political backing to consolidate on early successes for ongoing initiatives to achieve universal land registration, improve the quality of land data and expand digital solutions and online accessibility for land administration.

Continue to prioritise efforts to improve the regime for intellectual property (IP) rights, especially enforcement measures. Investors continue to report concerns with widespread online piracy and counterfeiting, long-standing market access issues for IP intensive sectors, high numbers of bad faith registrations of foreign trademarks by local companies and restrictive patentability criteria that make effective patent protection particularly challenging. The government is well aware of these concerns and is designing initiatives to address them. Improvements in implementation and IP enforcement measures will help to build overall investor confidence in this area.

Rethink existing approaches to reforming the court system. The government and the Supreme Court have taken significant strides towards ensuring judicial independence, creating specialised courts and judges, establishing a system for legal aid and expanding e-court services. Bold thinking may be required to dismantle certain negative perceptions regarding the effectiveness of the courts and revitalise the core institutions. The government may wish to consider commissioning a thorough review of the existing civil procedure rules, redesigning the system for judicial appointments to ensure integrity and encouraging the Supreme Court to propose, in consultation with civil society organisations and other stakeholders, more wide-ranging initiatives to promote transparency and greater public scrutiny of court functions.

Evaluate potential amendments to Law 30/1999 on Arbitration and Alternative Dispute Resolution. It may be prudent for the government to take stock of court decisions and user experiences under the law over the past two decades to assess the merits of potential amendments to improve legal certainty, user experiences and the attractiveness of arbitration in Indonesia. Areas for possible legislative clarification include the scope of the law vis-à-vis international arbitrations conducted in Indonesia, whether contract disputes involving claims based on tort or fraud are arbitrable and the public policy ground for refusing enforcement of an arbitral award under Article 66 of the law.

Maintain data protection and cybersecurity as a national policy priority. Comprehensive laws that draw on international good practices need to be enacted and effectively implemented in these areas. As with all legislation, the government should consult widely on the existing drafts of these laws and encourage input from business and civil society organisations. The government should also account for considerable, additional work once laws are in place to raise awareness among the private sector and other users, and nurture effective mechanisms to deal with security and data breaches.

Sustain momentum for building a culture of integrity in the public sector and throughout all levels of society. Among other initiatives, the KPK has made significant inroads into concerns regarding corruption through some impressive results, which have transformed it into an important symbol of the government’s commitment to fighting corruption. The government should continue to allocate sufficient resources to the KPK and other anti-corruption institutions and vigorously defend their independence.

Main policy recommendations for investment treaty policy

Continue to reassess and update priorities with respect to investment treaty policy. An important issue for period reassessment is how the government evaluates the appropriate balance between investor protections and the government’s right to regulate, and how to achieve that balance in practice. Indonesia’s model BIT, which the government is currently updating, should reflect the government’s current assessment of the appropriate balance and inform negotiations for new investment treaties. It is more difficult for governments to update their existing treaties to reflect current priorities. Depending on whether the parties wish to clarify original intent or revise a provision, it may be possible to clarify language through joint interpretations agreed with treaty partners. If revisions, rather than clarifications of original intent are desired, then treaty amendments may be required. Replacement of older investment treaties by consent may also be appropriate in some cases.

Continue to participate actively in inter-governmental discussions on investment treaty reforms at the OECD and at UNCITRAL. Many governments, including major capital exporters, have substantially revised their policies in recent years to protect policy space or to ensure that their investment treaties create desirable incentives. Consideration of reforms and policy discussions on frequently-invoked provisions such as FET are of particular importance in current investment treaty policy. Emerging issues such as the possible role for trade and investment treaties in fostering responsible business conduct as well as ongoing discussions about treaties and sustainable development also merit close attention and consideration.

Conduct a gap analysis between Indonesia’s domestic laws and its obligations under investment treaties with respect to investment protections. There are differences between the Investment Law and Indonesia’s investment treaties in some areas. Identifying these differences and assessing their potential impact may allow policymakers to ensure that Indonesia’s investment treaties are consistent with domestic priorities.

Continue to develop ISDS dispute prevention and case management tools. Whatever approach the government adopts towards international investment agreements, complementary measures can help to ensure that treaties are consistent with domestic priorities and reduce the risk of disputes leading to international arbitration. The government should continue to participate actively in the work of UNCITRAL’s Working Group III, the OECD and other multilateral fora on these topics. It may also wish to consider ways to promote awareness-raising and inter-ministerial co-operation regarding the government’s investment treaty policy and the significance of investment treaty obligations for the day-to-day functions of line agencies. Developing written guidance manuals or handbooks for line agencies on these topics could encourage continuity of institutional knowledge as personnel changes occur over time.

Embracing promotion of responsible business conduct can lead to far-reaching and strategic successes in attracting FDI and promoting a more sound and sustainable investment climate

Promoting and enabling responsible business conduct (RBC) is of central interest to policy-makers wishing to attract and keep investment and ensure that business activity contributes to broader value creation and sustainable development. RBC expectations are prevalent throughout global value chains and refer to the expectation that all businesses – regardless of their legal status, size, ownership structure or sector – avoid and address negative consequences of their operations, while contributing to sustainable development where they operate. RBC is an entry point for any company that wishes to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or to achieve specific economic and sustainability outcomes.

The COVID-19 crisis has exposed significant vulnerabilities in company operations in global value chains, including as related to disaster preparedness and supply chain continuity and resilience. Evidence has already shown that companies that are responsible have been better able to respond. An RBC lens can help them make more balanced decisions, while ensuring that further risks to people, planet and society are not created or contribute to further destabilising supply chains down the line.

Indonesia has historically promoted corporate social responsibility (CSR) and was one of the first countries to integrate CSR and corporate philanthropy within the legal framework during the previous decade. Recent efforts have looked to expand more toward RBC, notably in sustainable finance and business and human rights. A notable effort has also been Indonesia’s ambition to introduce transparency of beneficial ownership information. RBC-related activities in Indonesia have also been undertaken by the private sector and civil society.

These activities are positive and should be encouraged; however, a more strategic and coherent approach to promoting implementation of RBC across sectors by the government may be warranted, particularly in light of the heavy social impact COVID-19 has had on Indonesia’s manufacturing sector and the high environmental costs that growth so far has brought. International RBC standards, which address responsibility throughout the whole supply chain, can provide a useful framework for finding solutions to mitigate the worst impacts of COVID-19 in the short term and to help stakeholders avoid making harmful unilateral decisions. In the medium- and long-term, benchmarking sustainability efforts with international RBC standards can lead to more clarity in the market and promote trade and investment.

The Review suggests a bold policy direction where RBC can help ensure ongoing industrial strategies are stronger and fit-for-purpose for today’s global economy; reframe the conversation around existing business operations in sectors where risks are high; help re-orient the financial sector toward sustainable finance; give a signal to the market by directing SOEs on RBC and ensuring future growth does not exacerbate existing challenges; lead by example in key structural sectors like infrastructure; and fighting corruption and promoting integrity.

Main policy recommendations on responsible business conduct

Promote RBC and communicate clearly to businesses and investors government expectations on RBC in the context of the main national policies such as the 2015-2035 Master Plan of National Industrial Development and the efforts to promote the SDGs (in particular the follow up efforts to the 2019 Voluntary National Review and actions by the National Coordination Team for SDGs Implementation).

Promote broad dissemination and implementation of the practical RBC tools and instruments, such as the OECD due diligence guidances which were designed to support businesses. Support and facilitate collaborative industry and stakeholder initiatives on RBC.

Integrate explicit references to and expectations on RBC due diligence in Making Indonesia 4.0 strategy (including as related to the implementation of sectoral objectives) and promote industry alignment with global practice through the cross-sectoral national initiative to improve sustainability standards.

Ensure that the implementing regulations for the Omnibus Law on Job Creation include due consideration of environmental and social impacts of business operations and that streamlining of administrative procedures does not come at the expense of labour and environmental protection and an inclusive and sustainable development pathway. Consider making RBC due diligence a standard operating procedure in this context. Broad consultations with a wide range of stakeholders and at national and regional levels, including trade unions, civil society, affected stakeholders, and academia in addition to the business community, should be early, systemic, meaningful, and transparent.

Prioritise action on RBC in key sectors, notably agriculture, mining and garment and footwear sectors. Consider undertaking an alignment assessment of the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil standard with the OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains.

Accelerate efforts to promote environmental, social and governance (ESG) and RBC in the financial sector in line with international standards. Assess in particular the extent of barriers for integrating these factors in the market, notably when it comes to long-termism and quality of reporting and rating frameworks.

Pursue the development of the National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights in line with international best practice and with inter-ministerial involvement and consultation. Ensure that the scope of the plan is broad enough to capture the most relevant RBC-related issues. Ensure that the process supports a wide consultation with stakeholders.

Direct SOEs to establish and undertake RBC due diligence, publicly disclose these expectations and establish mechanisms for follow-up.

Lead by example and ensure integration of RBC in the high-profile Indo-Pacific Infrastructure and Connectivity strategic objectives. RBC due diligence should be a baseline and entry point for businesses wishing to participate in these efforts.

Strengthen implementation of the UN Convention against Corruption and closer alignment with the OECD Convention on combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions by criminalising bribery of foreign public officials and enacting corporate liability for corruption offences.