10. Building agricultural resilience to drought in Turkey

Turkey is exposed to multiple natural hazard-induced disasters (NHID) and has experience in managing the associated risks. Among these, drought has significant impacts on Turkey’s agricultural sector, and its frequency is expected to increase due to climate change. Turkey has established processes to manage natural hazards affecting agriculture, including drought, with governance and policy frameworks that seek to ensure that the agricultural sector is better prepared for adverse events and can respond effectively when these occur. While these mechanisms contribute to improved resilience, further opportunities exist to improve policy processes, in particular through increased farmer and private sector participation.

Droughts are increasingly observed in many of Turkey’s agricultural regions and their frequency and severity are expected to increase due to climate change. As the country’s largest water user, the sector’s resilience to drought requires action to solve the “water conundrum” of securing access to an increasingly rare and unpredictable resource while, at the same time, easing the demand pressure.

Government is central to planning for drought and crisis management, including through setting-up drought action plans, and basin-based drought and water management plans. Government also invests in data infrastructure and research.

Agricultural policies prioritise improving the capacity of the country’s farmers to produce and participate in markets through investment and development, including through support for new irrigation infrastructures, through farm programmes that encourage commodity output, including the production of strategic crops, and, more recently, through support for insurance take up. At the same time, in the absence of strong water allocation and enforcement programmes, these measures maintain the demand pressure on the water resource.

Efforts should now aim to (i) streamline government programmes, including water governance and policies; (ii) strengthen links with farmers and the food industry in the policy process; (iii) facilitate access to information systems on farm damages and losses from natural hazards; and (iv) overcome the skill and knowledge gap<!!Best practice on key box (unnumbered): Essential information ‒ such as key messages, recommendations, findings, calls for action ‒highlighting the main text. Ideally, no more than one page long.

Turkey is exposed to earthquakes, floods, drought, frost and avalanches, as a result of the country’s climatic and geographic diversity. Droughts, the focus of this case study, are increasingly common and of particular concern as they have an outsized effect on the livelihoods of farmers and the rural poor, in addition to their impact on the country’s market and export oriented value chains. Climate change is expected to increase the frequency and intensity of drought, emphasising the importance of strengthening the sector’s resilience to droughts. But improving the resilience of Turkey’s agricultural sector is complicated as many of the country’s farmers are not integrated into modern value chains, the farming structure is fragmented, there are significant regional income disparities, and the dissemination of technology and innovation is hindered by the generally low-skilled economy (OECD, 2016[1]; 2021[2]). The combination of these factors undermines farm productivity and resilience by limiting access to capital, services and knowledge.

The agricultural sector is the largest water user in Turkey (OECD, 2020[3]). Given the sector’s exposure to droughts, water infrastructure such as dams and irrigation are critical for the sector. Agricultural policies emphasise irrigation as a means of increasing and stabilising farm output, and irrigation projects account for more than half of public expenditure on general services for the sector (OECD, 2020[3]). At the same time, illegal groundwater abstractions for agricultural use are a growing problem, particularly when implementing basin-based water management.

The challenge for the agricultural sector is to strike a balance between economic development, and encouraging adaptation that builds the sector’s resilience to drought and other natural hazards. There is thus a need to improve the capacity of the country’s farmers to produce and participate in markets through investment and development, while ensuring that current investments and expenditures do not exacerbate future water stress conditions.

Four governance areas influence how natural hazard risks in the agricultural sector – including drought – are managed in Turkey, including disaster response plans, overall plans for economic development, agricultural policy frameworks (including specific sectoral plans for drought), and water governance frameworks. Disaster response in Turkey covers large-scale and mostly life-threatening critical risks, including floods, landslides, storms, wildfires and earthquakes. The Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (AFAD) has primary authority for disaster risk reduction, co-ordinating the preparation and implementation of disaster risk reduction plans which include both ex ante measures and ex post responses (AFAD, 2019[4]).

Turkey’s Eleventh five-yearly Development Plan (2019-23) sets development targets for all sectors, including for agriculture, as well as targets for strengthening the economy’s capacity to adapt to climate change (SBB, 2019[5]). The Development Plan seeks to increase the irrigation rate as a means to increase agricultural production. Turkey’s National Climate Change Action Plan (2011-2023) also prioritises strengthening the agricultural sector’s capacity to adapt to climate change. Specifically, the Action Plan requires agriculture to increase its capacity to act as a carbon sink; limit greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions; and develop its climate information infrastructure to adapt to and combat climate change (CSB, 2010[6]).

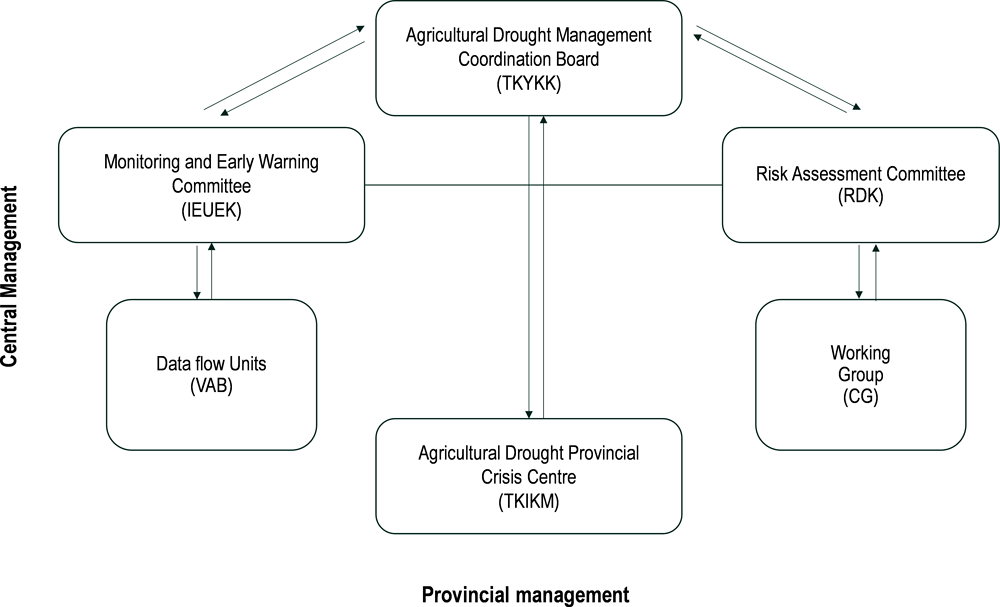

Turkey’s Strategy for Combatting Agricultural Drought and Action Plan (hereafter the “Drought Strategy”) aims to minimise the effects of droughts on agriculture by emphasising increased use of irrigation and water resources, and through risk assessment via the monitoring activities of the Agricultural Drought Management Coordination Board (TKYKK) (Figure 2). The Drought Strategy is implemented at the provincial level through Provincial Agricultural Drought Action Plans, which bring together local stakeholders under the lead of provincial governors. The action plans facilitate data collection and the implementation of response measures when an early warning is triggered. Turkey’s agricultural disaster risk management (DRM) frameworks for droughts, including the Drought Strategy, are mostly under the General Directorates (GD) of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF), as shown in Figure 10.1.

Recent institutional changes have attached directorates for water infrastructure (DSI), water management (SYGM), and meteorology (MGM) to the MAF, and hence strengthened MAF’s faculty to oversee critical areas for managing natural hazard and climate-related risks in agriculture. More generally, MAF shapes agricultural policy and oversees its implementation. Agricultural policy influences day-to-day farm management decisions and ultimately on-farm resilience. The current agricultural policy framework encourages commodity output and facilitates access to irrigation through infrastructure investments and a water price structure that does not internalise the full cost of the resource.

While each of the governance frameworks has its own target objectives, farmers and sector stakeholders make their decisions taking into account the entire policy environment. Accordingly, activities at all stages of the risk management cycle (risk identification, assessment and awareness; prevention and mitigation; preparedness; response and crisis management; and recovery and reconstruction) are considered holistically to better understand conditions, good practices, challenges and opportunities for the Turkish agricultural sector with respect to natural hazard risk management. In the case of drought, Turkey’s policy approach has long emphasised water investment and its management.

Risk identification, assessment and awareness

The public sector undertakes many of the risk identification, assessment and awareness activities in Turkey. Risk assessment has been prioritised as an integral component of Turkey’s Drought Strategy. Overall drought vulnerability assessments are conducted under Drought Action Plans by the Agricultural Drought Management Coordination Board. Awareness of drought risk is particularly high among agricultural agencies, which use an established methodology for analysing and monitoring drought. Agricultural drought management functions, and their linkages across the national and provincial levels, are illustrated in Figure 10.2.

The Climate Change Action Plan strengthens information systems to support the sector’s capacity to adapt to and mitigate the projected effects of climate change (CSB, 2010[6]). The plan identifies information systems that should be prioritised in the context of climate change adaptation in areas of specific relevance to agriculture, including erosion risk maps; land degradation with a soil and land database and inventory; carbon content mapping and monitoring; a land use and land use change database; a water resources database for assessing quality and capacity; and agricultural yields monitoring. The plan emphasises the promotion of sustainable agriculture techniques and soil management, including protecting soil and water resources and sequestering carbon.

Government agencies carry out and support research and development activities to analyse the effects of drought on plant growth. They also provide weather observations, early warning systems, and modelling and projections on weather and climatic events that adversely affect human, plant and animal health. Government agencies also prepare climate change adaptation and mitigation studies and projections that are used as inputs into climate change impact assessments as foreseen in the Climate Change Action Plan. However, efforts to anticipate the likely effects of climate change are scattered, while whole-of-economy risk reduction action plans have not yet been developed (OECD, 2019[8]).

Turkey has several data repositories on agricultural damage and losses, including an inventory of insured events and their cost to individual farms. Currently, data on farm losses are limited to use by policy makers and insurers, for loss compensation support or insurance pay-outs, and are not available to private sector stakeholders. The potential exists to improve private sector stakeholders access to farm loss data through available repositories, to increase awareness of the sector’s exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards, and inform investments to mitigate those risks (Box 10.1).

The TABB is an online platform providing harmonised evidence on natural and human-induced events going back to 1900 and is available to the public. TABB features an analysis module where individual events are recorded and a library module where disaster related resources are stored in electronic form or their location references. Recorded disaster events can be visualised in tabular form as well as maps. In the absence of economic information, a simple count of agricultural events registered in the TABB database highlights a relatively high frequency of floods and droughts.

Risk prevention and mitigation

Ex ante investments in measures to prevent or mitigate disaster risk can reduce the cost of disaster response and recovery, by addressing underlying vulnerabilities and reducing natural hazard exposure. Government policies and programmes can also encourage stakeholders to identify disaster risks to their own assets, and address gaps in their resilience levels. In Turkey, the risks identified in the agricultural DRM frameworks are the basis of agricultural prevention and mitigation measures for natural hazard risks, including:

Disaster Risk Reduction Plans (TARAP and IRAP). The national Disaster Risk Reduction Plan (TARAP) is pending while the first provincial Disaster Risk Reduction plan (IRAP) is published. The IRAP, published for the Kahramanmaraş Province, prioritises investments in risk mitigation and prevention to protect lives and properties, including to mitigate the effects of climate change on floods and excessive heat. Six other IRAPs are planned for publication in 2021.

Surface and groundwater infrastructures, which are managed by Turkey’s central water infrastructures agency (State Hydraulics Works; DSI). The agency is responsible for constructing and maintaining irrigation and drainage infrastructure, with the operation and maintenance of canals gradually being decentralised and transferred to water users’ organisations and municipalities. The development of new irrigation infrastructures, with pressurised piped irrigation systems and the installation of centralised water measuring instruments, aims to renew the ageing infrastructure, expand the irrigated area, increase water use efficiency and reduce water loss. However, about 80% of groundwater wells are informal (IBRD, 2016[9]).

Sectoral Water Allocation Plans prepared by the GD Water Management (SYGM) are based on sectoral demands and water needs, but there is no accounting of farmers’ water use in the absence of meters, and agricultural needs are estimated based on crop cover area and crop water needs. The allocations are indicative, with no enforcement mechanisms.

Agricultural insurance under TARSIM offers a variety of products to mitigate the financial impacts of natural hazards on agriculture. Insurance subscription is supported by premium subsidies and the portfolio of insurance products was enlarged to include drought insurance while digitally enabled tools accelerate compensation payments (TARSIM, 2020[10]). Among crops insured, the largest coverage is for wheat, but all crops and geographic locations can be insured and there are no exclusions based on dry area farming. Under these conditions, there are few incentives for farmers themselves to adopt prevention and mitigation measures.

R&D efforts to alleviate pressure on water resources and to enhance the sustainable management of water are undertaken by the Turkish Water Institute (SUEN) to provide science-based advice to support planning and formulation of water policies and strategies. The network of public agricultural research centres (TAGEM) carries out research and data collection on drought resistant crop varieties and animal breeds, and effective soil and water management is a priority of the National Strategy on Climate Change (CSB, 2010[11]).

Extension services and farmer field schools, operated by TAGEM, disseminate drought resilient farming practices and contribute to raising farmers’ awareness on the effects of climate change. However, farm-level uptake of prevention and mitigation activities is uneven, and the provision of extension services remains critical for sustainable productivity growth.

Risk preparedness

Ex ante disaster preparedness and planning are crucial for effective crisis management – by public and private stakeholders with a role in disaster response, and on farms. Risk preparedness in Turkey is supported by established natural hazard monitoring programmes that inform public agencies about developing risks. These include watershed monitoring, drought monitoring, flood monitoring and monitoring of weather and other risks.

Turkey’s DSI collects estimates of irrigation water needs through Irrigation Declarations from all irrigated farms. The declaration provides information on the location, amount of irrigation needed, crop and type of land to be irrigated during the irrigation season, through comparing estimates of irrigation water demand with the existing water resource potential and system capacity.

MGM provides agricultural weather forecasts and monitors weather-related risks, and issues early warnings for adverse weather events that can be used to inform crop-planting and animal husbandry decision-making. However, the extent to which farmers make use of these tools and services, and their take-up rates in the sector, are not clear.

Research into risk preparedness for the agricultural sector in Turkey is carried out in co-operation with international research networks (Box 10.2). In addition, the extension service helps to build farmers’ capacity to manage the effects of climate change on the sector.

Turkey’s public research centres (TAGEM) engage in international research networks, including by participating in regional or thematic co-operation and projects. The benefits of international research co-operation are numerous. Projects mutualise and strengthen research capacity, improve access to research outputs and accelerate the dissemination of knowledge and results. They ease access to funds and mobilise individual expertise of each institution to generate knowledge that can be widely disseminated.

Disaster response and crisis management

Effective crisis management and response in the event of an emergency hinge on all actors knowing their responsibilities and communicating effectively, with the public sector taking a leadership role when the private sector is unable to cope. The role of government is central in Turkey in co-ordinating disaster response with AFAD co-ordinating the preparation and implementation of disaster risk reduction plans and interagency co-ordination (AFAD, 2019[4]).

In the event of droughts, early warnings are addressed to local Agricultural Drought Provincial Crisis Centres that manage the local response. They declare the state of emergency and assign response tasks among agencies and provide guidance for planting alternative crops and taking sanitary and phytosanitary measures to avoid pests and diseases, while ex post they evaluate and communicate on-farm damages for central government compensation. In the event of product loss or damage to agricultural equipment due to risks that are not covered by the agricultural insurance scheme (TARSIM) or are of an exceptional scale, farmers’ losses may be compensated by the government (TRGM).

Recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction

Following a natural hazard induced disaster, recovery and reconstruction efforts offer an opportunity for public and private stakeholders to “build back better” by addressing underlying gaps in resilience, and building the capacities needed to manage natural hazards in the future. This requires all stakeholders – including producers – to learn from natural hazard induced disasters in order to adjust DRM frameworks, policy measures and on-farm strategies forming long-term resilience.

Recovery and reconstruction activities for natural hazards in Turkey range from large economy-wide projects to repair damaged infrastructure, to programmes that support the financial recovery of farmers. Recovery from drought events largely happens on farms and is predicated on a return to “normal” rainfall levels. Government involvement in on-farm drought recovery in Turkey mostly consists of the provision of inputs, financial compensation, and activities under the Drought Strategy to better prepare the agricultural sector for the next drought. Other government funded instruments supporting recovery and reconstruction include credit subsidies and repayment deferrals, direct payments, technical assistance and support for repairing equipment.

Effective on-farm drought recovery underscores the imperative of longer-term improvement in water resource availability through infrastructure rehabilitation and more efficient farm-level utilisation of available water resources. In general, Turkey’s approach puts a strong emphasis on irrigation and support to commodity output. But, most importantly, the sector’s use of irrigation reflects the water price structure that does not internalise the full cost of the resource.

Insurance indemnities are typically an effective coping tool, and agricultural insurance programmes in Turkey are improving, for example through efforts to accelerate compensation payments. Government compensation is foreseen for damages to agricultural products or equipment that result from risks that are not insurable. However, the conditions of compensation, including timing and scale, are not announced in advance.

Turkey’s Drought Strategy recognises the role of evaluating existing processes as a way to inform and shape future policy developments. But it is not clear if post-event evaluation and assessment of drought events is undertaken, if they involve private sector stakeholders, or, if such assessments have led to improved future preparedness.

In line with the four principles for resilience to natural hazard-induced disasters in agriculture (Chapter 3), Turkey’s systems for natural hazard risk management – and drought management in particular – demonstrate a number of positive developments and good practices, as well as some challenges that provide opportunities for future improvement.

An inclusive, holistic and multi-hazards approach to natural disaster risk governance for resilience

An all-hazards approach to natural hazard risk must be implemented in agriculture. AFAD implements a whole of government response to large scale, and mostly sudden and life-threatening hazards, but does not include droughts. Moreover, agricultural DRM frameworks in Turkey are mainly shaped by agricultural policy. A co-ordinated and integrated approach to prepare for and manage the adverse effects of droughts should be integrated in an inclusive, holistic and multi-hazards approach.

Efforts and reforms conducted over the decades have resulted in a multiplicity of frameworks with potential duplication. Efforts to integrate risk management principles and plans for readiness for drought into national programmes and joint action plans of the central and provincial governments offer opportunities to further progress towards a more holistic approach by linking together and aligning existing policy components in a cohesive way. Diffuse governance among multiple agencies results in a lack of coherence and consistency and weakens policy outcomes. Turkey should harness the benefits of recent changes in MAF’s structure that now include wider policy areas that are all critical for risk management for the agricultural sector.

Risk governance in Turkish agriculture would benefit from a more explicit identifications of roles and responsibilities of each actor in natural disaster risk management. In Turkey, the government formulates and implements agricultural DRM strategies for drought but clear conditions for policy response would enhance farmers’ engagement in risk reduction and incentivise farm-level adaptation to hazards that will be exacerbated by climate change. The involvement of stakeholders is still limited to a consultative role and more frequent interactions between local, regional, and national authorities on the one hand, and farmers on the other, would help create a culture of awareness of the risks as well as provide a clearer demarcation of roles and responsibilities. In addition, current policies have a potential to crowd out farmers’ own initiatives, as they do not consider their role and responsibility to prevent, prepare for, and respond to risk. The Drought Strategy should delineate clearly the roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder beyond government to ensure that the impacts of droughts are effectively minimised.

Eliminating barriers to stakeholder participation in DRM would demonstrate a more inclusive multi-hazard risk reduction approach at the national and the provincial level. Turkey’s Drought Strategy focuses on local level involvement in the agricultural sector, while Agricultural Drought Provincial Crisis Centres are a valuable interface between the national and local government when planning drought response.

A shared understanding of risk based on the identification, assessment and communication of hazards, vulnerability and resilience capacities

Investments in strengthening risk identification and assessment are public goods that raise stakeholder awareness of exposure to risks and inform actions.

Drought is a slow-onset hazard and Turkey’s National Climate Change Action Plan recognises the importance of monitoring weather conditions. Analysing agricultural droughts and prioritising data collection and drought monitoring and assessment activities involves multiple actors. It is important that these assessments are accessible to all levels of government and stakeholders, in order to inform the decision making process and actions taken.

Ex post information on agricultural economic losses is held in several repositories, but not generally available to private sector stakeholders. Through insurance schemes and MAF’s provincial directorates, Turkey assesses agricultural damages and losses as a result of natural hazards. But assessments are not publicly available and none of the public repositories contain critical economic loss data that would enable analysis of their impacts. The information base should be strengthened by including economic variables in repositories, to identify priority policy areas, and tailor and target risk management policies.

Turkey has the opportunity to strengthen links with farmers and stakeholders to improve communication about risk. While the public sector undertakes many of these risk identification and assessment activities, links with the private sector and farmers are weak and stakeholders point to the lack of access to information on their exposure to climate related risks. The role of the government in disseminating relevant data and information is central in enabling evidence-based and risk-informed decisions to strengthen resilience.

An ex ante approach to natural hazard-induced disaster risk management

Government agencies recognise the importance of implementing an ex ante approach to disaster risk management. Public funding supports conventional and modernised irrigation infrastructure which can increase water use efficiency. Public research activities – with regional and international collaboration – on topic such as heat tolerant breeds and crop varieties, smart technologies for irrigation, drought adapted soil management, are examples of ex ante approaches that support on farm risk management practices. Finally, support to agricultural insurance take up can help improve farmers’ risk recovery from NHIDs.

Turkey invests in structural and non-structural measures to mitigate and prevent drought risks but water policies need be strengthened. Agriculture is Turkey’s largest water user, but most of the country’s irrigated lands use potentially inefficient irrigation methods or facilities. Investment in irrigation infrastructure is critical but needs to be accompanied by a strong water allocation and enforcement programme, including the phasing out of informal wells. Implementation of water allocation systems, including water pricing, should also be flexible enough to respond to and mitigate drought impacts.

Turkey’s public research initiatives on climate change adaptation and on disaster risk help the agricultural sector prepare, plan for, and more successfully adapt and transform in response to droughts and contribute to sector productivity and sustainability. While research enhances Turkey’s adaptation and mitigation measures, there is little evidence on farm level awareness and adaptive practices, aggravated by the generally low-skilled economy, which hinders the dissemination of technology and innovation. Training programmes and capacity building, including access to extension services to ease on-farm take-up of water saving techniques, are necessary to reduce vulnerability to drought.

Turkey’s reform of agricultural insurance has provided farmers more options for ex-ante risk management tools. Take up of insurance by farmers is low but growing in response to insurance premium subsidies and a high-tech web-based system. However, ex post public compensation criteria should be announced in advance, conditional on insurance take-up, and limited to catastrophic events.

Adapting crops to climate and soil conditions can build drought resilience, but farmer uptake of preventative or mitigating measures may be hindered by an agricultural policy that encourages commodity output. Efficient water use requires a shift away from output-based support towards support conditional on more sustainable and water efficient production methods.

An approach emphasising preparedness and planning for effective crisis management, disaster response, and to “build back better” to increase resilience to future natural hazard-induced disasters:

Government is at the centre of disaster response and more could be done to ensure farm sector participation, to support on-farm response capacities, and recovery

Turkey’s adaptation and restructuring of its government agencies helped to better respond to emergency situations. The establishment of AFAD by bringing together key agencies for emergency crisis management improved the effectiveness of crisis management and disaster response. Similarly the recent changes in MAF’s structure to include wider policy areas that are all critical for risk management in the agricultural sector could be harnessed to increase the sector’s resilience to future NHID.

Droughts have a disproportionate impact on the livelihoods of subsistence farmers and the rural poor, given their limited capacity to manage risk. Effective integration of farmers into networks for disaster risk management can help mitigate their impacts. Farmers’ integration in local networks can help cushion the immediate adverse effects of NHIDs while access to extension services can help longer term capacity building. Both dimensions can be served by the Drought Strategy as it may serve to build capacities and networks that are necessary when disasters occur, by defining stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities in advance, as is the case under the AFAD’s emergency response. Support trigger criteria should be defined in advance and clearly communicated to farming communities so that farmers can make better DRM decisions.

Ex post assessment of drought impacts is an important step in the process for strengthening resilience and building back better. However, it is not clear that post-disaster assessments are undertaken regularly in Turkey or that they cover not only the impacts of adverse events on the farm business, farmers’ livelihoods, and farm facilities, but also assess governance and the functioning of the social systems.

Turkey has established processes to manage natural hazards affecting agriculture, including drought, which contribute to the sector’s resilience. Turkey’s governance and policy frameworks seek to ensure that the agricultural sector is better prepared for adverse events and can respond effectively when these occur. But there is an opportunity for public and private stakeholders to:

Enhance on-farm preparedness and adaptation to drought risks by improving data access and private sector participation in the policy planning process. Ex post information on agricultural economic losses are held in several repositories, but they are not available to private sector stakeholders. Improved access to farm loss data would increase awareness of the sector’s exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards, and inform investments to mitigate risks.

Invest in training and extension services that are tailored to the needs and capacities of farming population. It is important to minimise the knowledge gap and accelerate on-farm adoption of more efficient irrigation systems and water saving techniques.

Encourage more efficient water management so as to mitigate and prevent drought impacts. Turkey should strengthen local water allocation regimes and incentivise water saving. Water fees should be used to cover the operation and administration costs of irrigation networks. Investing in the gradual implementation water metering and use-monitoring, including by bringing illegal wells into formality, combined with the provision of water related extension services is an important step in this direction.

Closer attention should be paid to the linkages and trade-offs between agricultural policy that supports specific commodity production and sustainable water use. Commodity payments can incentivise water use and water stress. The transition away from commodity support to the provision of sector-wide services that enhance the sector’s capacity to prepare, prevent, absorb and reconstruct are necessary steps in the direction of sustainable productivity growth.

References

[4] AFAD (2019), Strategic Plan 2019-2023, Ministry of Interior, https://en.afad.gov.tr/kurumlar/en.afad/e_Library/plans/AFAD_19_23-StrategicPlan_Eng.pdf.

[6] CSB (2010), Republic of Turkey Climate Change Action Plan 2011-2023, https://policy.asiapacificenergy.org/sites/default/files/National%20Climate%20Change%20Action%20Plan%202011-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2020).

[11] CSB (2010), Turkey’s National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy 2010-2023, https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/iklim/editordosya/iklim_degisikligi_stratejisi_EN(2).pdf (accessed on 7 November 2020).

[9] IBRD (2016), Valuing Water Resources in Turkey, The World Bank, http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/600681476343083047/pdf/AUS10650-REVISED-PUBLIC-Turkey-NCA-Water-Valuation-Report-FINAL-CLEAN.pdf.

[2] OECD (2021), OECD Economic Surveys: Turkey 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/2cd09ab1-en.

[3] OECD (2020), Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/928181a8-en.

[8] OECD (2019), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Turkey 2019, OECD Environmental Performance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264309753-en.

[1] OECD (2016), Innovation, Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability in Turkey, OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264261198-en.

[5] SBB (2019), “Presidency of Strategy and Budget”, Eleventh Development Plan (2019-2023), http://www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Eleventh_Development_Plan-2019-2023.pdf (accessed on August 2020).

[10] TARSIM (2020), 2019 Annual Report, https://web.tarsim.gov.tr/havuz/dokumanGoster.doc?_key_=588A0CCE2D31D152E41507A43EF483DC60580037HJH2V33IL4PV28V07109012021 (accessed on 29 April 2021).

[7] TKYKK (2013), “Agricultural Drought Management Coordination Board”, National Drought Management Policies - Activities for combatting agricultural drought in Turkey, https://www.droughtmanagement.info/literature/UNW-DPC_NDMP_Country_Report_Turkey_2013.pdf.