copy the linklink copied!2. Understanding recent trends in cardiovascular disease mortality in European countries

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in Europe. Previous declines in cardiovascular disease mortality have played a vital role in improving life expectancy in European countries. However, since 2010, several countries are experiencing a levelling out of the rate of decline in cardiovascular mortality in populations aged below 65, while a few countries are experiencing increases in mortality rates. This calls for urgent action in monitoring closely recent trends in mortality and incidence, and identifying the underlying causes. Currently, unhealthy diets make the largest contribution to the population-level CVD mortality burden, with over 40% of CVD deaths being attributed to dietary factors, and prevalence of overweight, obesity and diabetes is on the rise. In other words, we have not reached the point where no more gains can be achieved in cardiovascular mortality, and especially in premature mortality.

This article is based on a presentation made by Susanne Løgstrup, Director of the European Heart Network (EHN). All data presented are published in European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics, 2017 edition, published by the European Heart Network (Wilkins et al., 2017[1]).

copy the linklink copied!European cardiovascular disease statistics

Since 2000, the European Heart Network (EHN) has published five editions of European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics. The most recent edition was published in 2017.

The report provides data on both mortality and morbidity. It also provides data on treatment and determinants of cardiovascular disease, including diet, smoking, physical activity, alcohol, blood pressure, blood cholesterol, overweight and obesity, and diabetes. These data are collected from international sources, including the World Health Organisation, the Global Burden of Disease Project (IHME) and the OECD.

In addition, the report includes a section on economic cost which is based on original research. It covers only the European Union (EU data in this chapter refers to EU28 member states).

copy the linklink copied!Burden of cardiovascular disease in Europe

Mortality

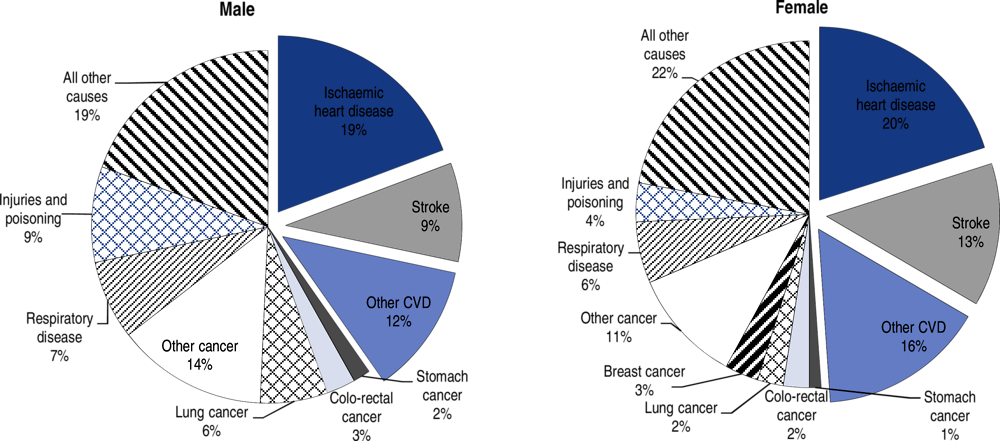

CVD is the leading cause of death in Europe1 causing 3.9 million deaths every year, 45% of all deaths. In the EU, CVD is also the leading cause of death accounting for over 1.8 million deaths every year, which corresponds to 37% of all deaths (Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2).

CVD is also the leading cause of premature death (death before age 65 years) in Europe, accounting for close to 670 000 deaths (29% of all deaths) every year. In the EU, CVD claims more than 190 000 deaths per year at ages under 65 years (22% of all deaths).

The main forms of CVD are ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke. In Europe, IHD is the single largest cause of death, responsible for more than 860 000 deaths among men (19% of all deaths) and almost 880 000 (20% of all deaths) among women each year. Stroke is the second largest single cause of death in Europe, accounting for 405 000 deaths in men (9% of all deaths) and over 580 000 deaths in women (13%) each year.

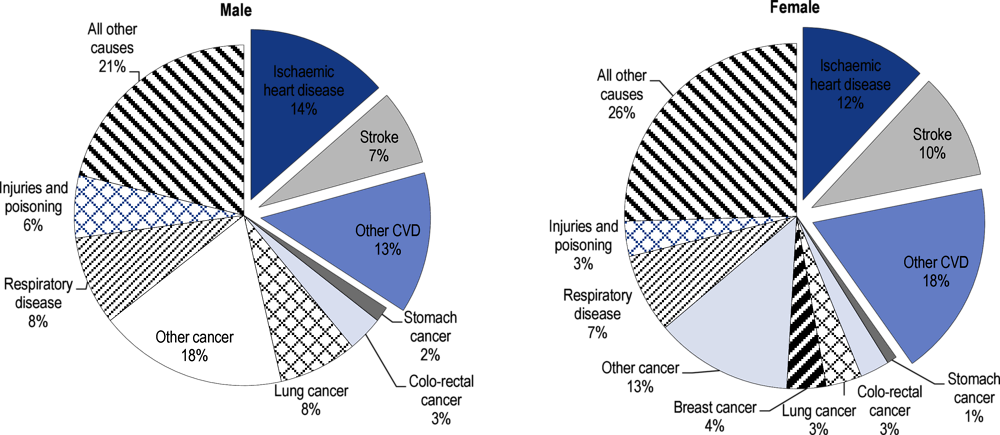

As in Europe, IHD and stroke are, respectively, the first and second most common single causes of death in the EU. IHD is responsible for over 335 000 (14%) of all deaths among men and close to 300 000 (12%) among women. Stroke accounts for over 175 000 (7%) male deaths and just under 250 000 (10%) female deaths.

Costs

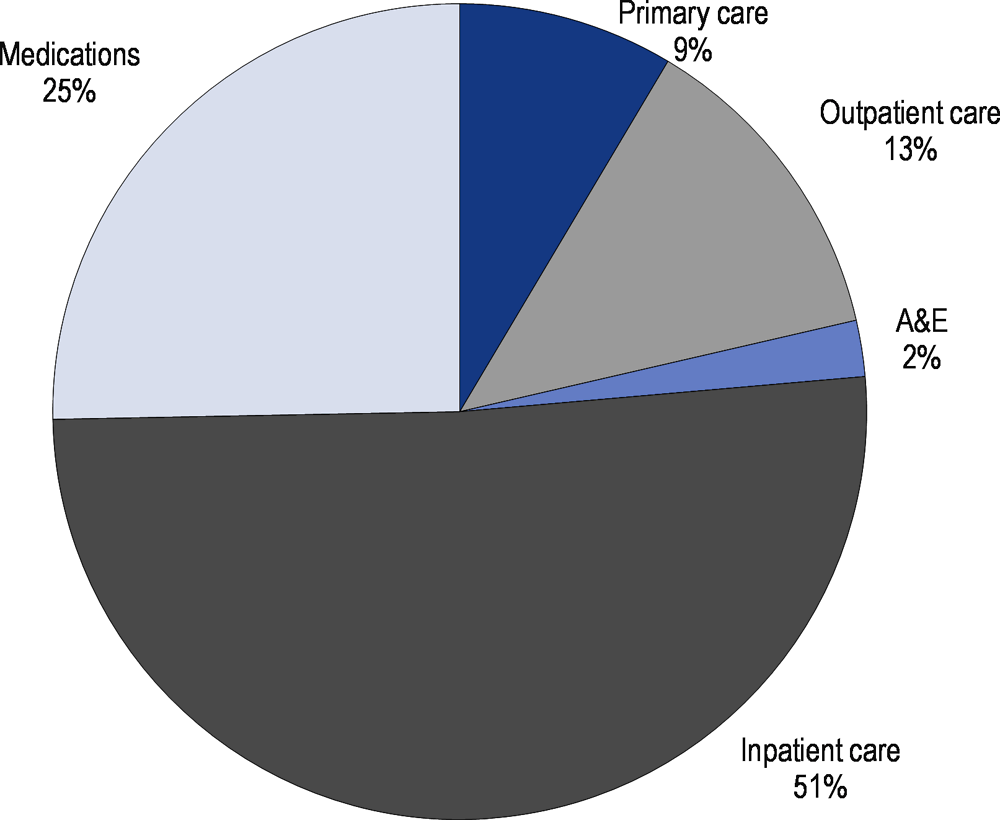

CVD is estimated to cost the economies of the EU around EUR 210 billion per year (2015 figures). Of this total cost, just over half (EUR 111 billion) is spent on health care (Figure 2.3). Lost productivity accounts for 26% of total costs, or EUR 54 billion; and informal care costs amount to EUR 45 billion (21% of total costs).

copy the linklink copied!Variations in cardiovascular disease mortality in Europe

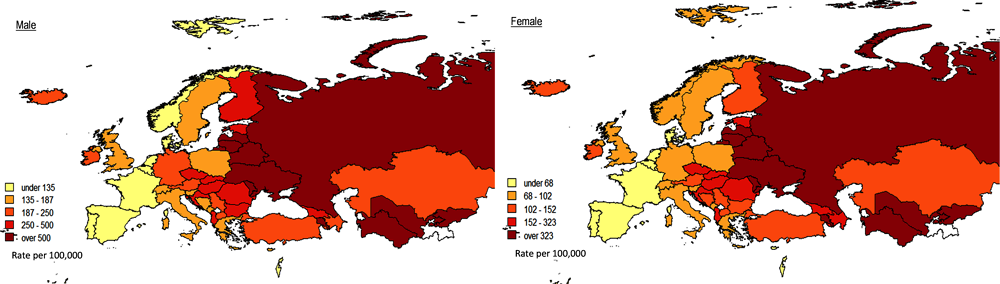

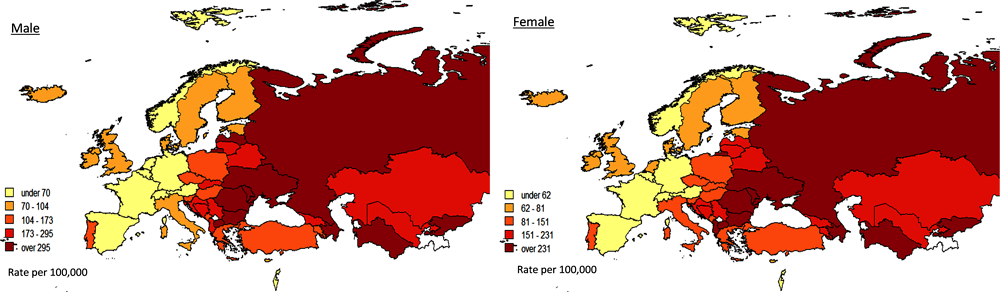

There are wide geographical disparities across Europe in age-standardised mortality rates2 for CVD.

High rates are observed in Eastern and Central European countries, particularly post-Soviet states, compared to rates in Northern, Southern and Western regions of Europe. This pattern is observed for both IHD and stroke (Figure 2.4 and Figure 2.5).

In the EU, the lowest age-standardised mortality rate for IHD is found in France, with 77 deaths per 100 000 in males and 32 deaths per 100 000 in females, and the highest in Lithuania with 700 deaths per 100 000 in males and 429 deaths per 100 000 in females – a nine-fold difference in men and a 13-fold difference in women. The lowest age-standardised mortality rate for stroke in men in the EU is found in France and Luxembourg with 53 deaths per 100 000 and the highest in Bulgaria with 353 deaths per 100 000. In females, the lowest rate is also found in France with 42 deaths per 100 000, and the highest again in Bulgaria with 281 deaths per 100 000 – a six-fold difference in both men and women.

In European countries that are not members of the EU, the lowest age-standardised mortality rate for IHD is found in Israel, with 115 deaths per 100 000 in males and 67 deaths per 100 000 in females, and the highest in Ukraine with 1 102 deaths per 100 000 in males and 727 deaths per 100 000 in females – an almost 10-fold difference in men and an almost 11-fold difference in women. The lowest age-standardised mortality rate for stroke is found in Switzerland with 51 deaths per 100 000 in males and 47 deaths per 100 000 in females, and the highest in Macedonia with 383 deaths per 100 000 in males and 345 deaths per 100 000 in females – a 7-fold difference in both men and women.

copy the linklink copied!Trends in CVD mortality in Europe

Historic

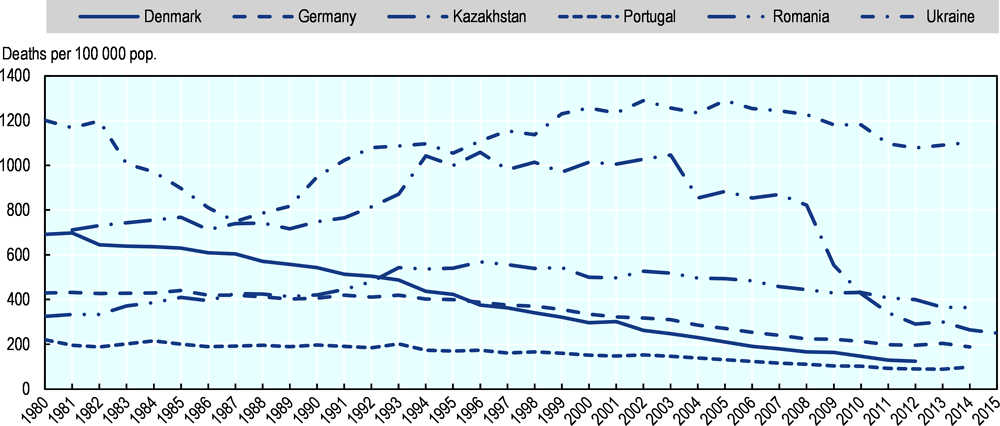

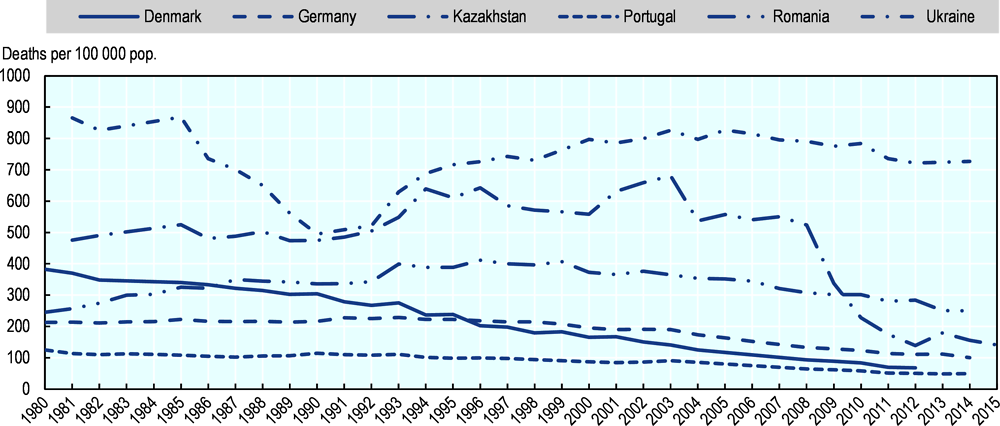

Over the past 30 to 50 years, mortality rates from IHD have been declining in most Northern and Western European countries in both males and females. Long-term trends in Central and Eastern European countries have been less consistent with sharp decreases followed by sharp increases and then further decreases in countries such as, for example, Ukraine.

However, since around the period 2000-2005, age-standardised mortality rates from IHD have been falling in the majority of European countries, including Central and Eastern European countries. Nevertheless, the rate of decline in mortality has been highly variable. In the EU, the percentage rate of decline from 2003 to the most recent year varied from 13% (Czech Republic) to 53% (The Netherlands) in men, and from 8% (Czech Republic) to 57% (Estonia) in women.

Recent evidence

In the first decade of the 21st century, evidence that IHD mortality rates were beginning to plateau in younger age groups had been demonstrated to varying extents and at differing time points in England, Wales, Scotland, United States and Australia (Nichols et al., 2013[2]).

On this basis, we analysed trends in age-specific IHD mortality in the EU over three decades (1980-2009). The results, which were published in 2013 (Nichols et al., 2013[2]), found little evidence to support the hypothesis that there had been a consistent pattern of recent plateaus in CHD mortality rates, or that any plateaus have occurred largely or exclusively in younger age groups. In the majority of countries, the research found that most recent reductions in average annual percentage changes in CHD mortality were as great as, or greater than, they had been previously.

It further found that substantial heterogeneity exists across the EU, and when individual countries were examined, there were some countries with cause for concern, where rates of decrease in IHD mortality appeared to have slowed, including in the United Kingdom. In addition, there were two countries, Greece and Lithuania, in which IHD mortality rates had begun to significantly increase at younger ages in recent years.

The trend from 1980-2009 in the United Kingdom seems to continue for individuals aged under 65. For men aged under 65, the death rate from IHD fell from 2010 to 2013 but remained the same in 2012 and 2013; the mortality rate from stroke flattened completely with no reductions between 2011 and 2013. For women in the United Kingdom, however, there has been no reduction in mortality rates from IHD between 2010 and 2013; and we see similar trends for stroke.

With respect to Greece, the findings from the 2013 study seem to be confirmed by more recent data. In men under 65, the mortality rate for IHD was fluctuating with the latest year (2012) showing an increase on the previous year. The mortality rate from stroke increased in men between 2010 and 2012. For women aged under 65 in Greece, mortality rates from both IHD and stroke are not decreasing.

The trends for Lithuania, however, have improved with reductions in mortality rates from IHD and stroke in both women and men under 65 since 2010.

In several Southern European countries, with traditionally low CVD mortality rates, we observe little to no reductions in mortality rates from IHD and stroke in people aged under 65 since 2010. In Spain, the mortality rate from IHD in men under 65 is vacillating between no reduction and an increase; and for stroke, there has been no reduction in mortality rates since 2010 until the latest year (2014). In Spain, in women aged under 65 there has been no reduction in mortality rates from either IHD or stroke since 2010 until the latest year (2014). In Portugal, mortality rates from IHD in men aged under 65 increased in 2013 and 2014; while for stroke mortality rates have fallen slightly following three years of no reduction in mortality rates. For Portuguese women aged under 65, mortality rates from IHD remained the same from 2010 to 2013 and an increase was observed in 2014. From 2011-14, there have been no reductions in mortality rates for stroke in women aged under 65 in Portugal.

Other countries in the EU where a slowdown has been observed in mortality rates from IHD in men aged under 65 since 2010 include Cyprus, Denmark, and France. In Luxembourg, we observe an increase in death rates from IHD in men under 65 in 2013 and 2014. In women under 65, a slowdown is observed in mortality rates from IHD in Denmark, Finland, France, Italy and Malta, the latter with increases in mortality rates in women since 2010.

With regard to stroke in men aged under 65, mortality rates have been at the same levels since 2010 in Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands and Sweden. In the Netherlands, mortality rates have also been at the same levels since 2010 in women aged under 65 and this is also the case for France.

We underline that the trends observed are over a three- to five-year period depending on countries. Some countries report their data more regularly.

copy the linklink copied!Conclusion

The data available for Europe suggest that, since the beginning of the past decade (2010), several countries in the EU are experiencing a levelling out of the rate of decline in CVD mortality in people aged under 65 (based on data for IHD and stroke), and a few countries are experiencing increases in mortality rates. An in-depth analysis is beyond the scope of this article.

Given that CVD is the leading cause of death in Europe, and that previous declines in CVD mortality have played a vital role in improving life expectancy in European countries, we recommend monitoring closely recent trends in overall and premature CVD mortality, among men and women, and identifying the underlying causes.

It is also important to monitor incidence. It is noteworthy that in France, the declines in incidence rates of coronary events have been more modest than those in mortality and were driven mainly by strong downward trends in the oldest age group, 65-74 years, whereas no change was seen among younger men and women aged 35-64 years (Salomaa, 2020[3]; Gabet et al., 2017[4]). Similar findings are reported for Finland, Australia and United States, and suggest that preventive measures need to be strengthened. To monitor risk factor levels and incidence adequately, countries need to develop comprehensive morbidity surveillance systems, including the effective use of electronic health information systems.

Even if some countries have reached relatively low CVD mortality rates, especially in the younger populations, it should not be concluded that they cannot reduce mortality further. At least 50% of the reductions in mortality achieved in the past can be attributed to behavioural risk factors, including smoking and high salt intake. While smoking rates have gone down across Europe, prevalence of overweight, obesity and diabetes has increased.

Currently, unhealthy diets make the largest contribution to the population-level CVD mortality burden, with over 40% of CVD deaths being attributed to dietary factors. It is crucial to introduce policies that promote healthier diets and discourage unhealthy diets – including both the supply and the demand side, see for example EHN’s 2017 paper on Transforming European food and drink policies for cardiovascular health (European Heart Network, 2017[5]).

There is also a need for continued investment in treatment of cardiovascular patients. There is a concern that few new treatment options are in the pipeline.

In other words, we have not reached the point where no more gains can be achieved in cardiovascular mortality, and especially in premature mortality.

Acknowledgements: EHN would like to thank Nick Townsend, Senior Lecturer, Department for Health, and University of Bath for his help in writing this paper.

References

[5] European Heart Network (2017), Transforming European food and drink policies for cardiovascular health, European Heart Network, Brussels, http://www.ehnheart.org/publications-and-papers/publications/1093:transforming-european-food-and-drinks-policies-for-cardiovascular-health.html (accessed on 6 February 2020).

[4] Gabet, A. et al. (2017), “Acute coronary syndrome in women: rising hospitalizations in middle-aged French women, 2004–14”, European Heart Journal, Vol. 38/14, pp. 1060-1065, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx097.

[2] Nichols, M. et al. (2013), “Trends in age-specific coronary heart disease mortality in the European Union over three decades: 1980–2009”, European Heart Journal, Vol. 34/39, pp. 3017-3027, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht159.

[3] Salomaa, V. (2020), Worrisome trends in the incidence of CHD events among young individuals, SAGE Publications Inc., https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319896051.

[1] Wilkins, E. et al. (2017), European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2017, European Heart Network, Brussels, http://www.ehnheart.org/images/CVD-statistics-report-August-2017.pdf.

Notes

← 1. When we refer to Europe, we refer to the 53 member states of the World Health Organization’s European Region.

← 2. Rates are age-standardised to the 2013 European Standard Population.

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/47a04a11-en

© OECD and The King's Fund 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.