1. Trends shaping early childhood education and care

This report is based on findings from the Quality beyond Regulations policy review, which was initiated to support countries and jurisdictions in understanding and enhancing quality in early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings. This chapter introduces the findings from the policy review and provides context for the results presented in subsequent chapters by summarising key issues and trends in the field of ECEC. Focus is given to curriculum and pedagogy, and to workforce development as key policy levers to enhance quality, with attention to three additional policy levers: governance, standards and funding; data and monitoring; and family and community engagement.

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) can give a strong start to all children by providing equitable opportunities and experiences that support development. Participation in ECEC is typical and universal, or near-universal, in several OECD countries, for children aged 3 to 5 years.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic may exacerbate inequitable enrolment in ECEC and mean that more children miss opportunities to participate in ECEC. Children from socio-economically disadvantaged families continue to be less likely than their more advantaged peers to participate in ECEC. In addition, although enrolment of children under age 3 in ECEC is increasing, it is still more variable than participation of older children.

There is more variability in approaches to ECEC governance, oversight and funding than at most other levels of education. The 26 countries and 41 jurisdictions that participated in the Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire reported on 56 different curriculum frameworks. They provided information on staff training requirements and working conditions across more than 120 different types of ECEC settings.

Despite growing ECEC enrolment and recognition of the value of high-quality ECEC, investments in this sector remain below public spending for later stages of education.

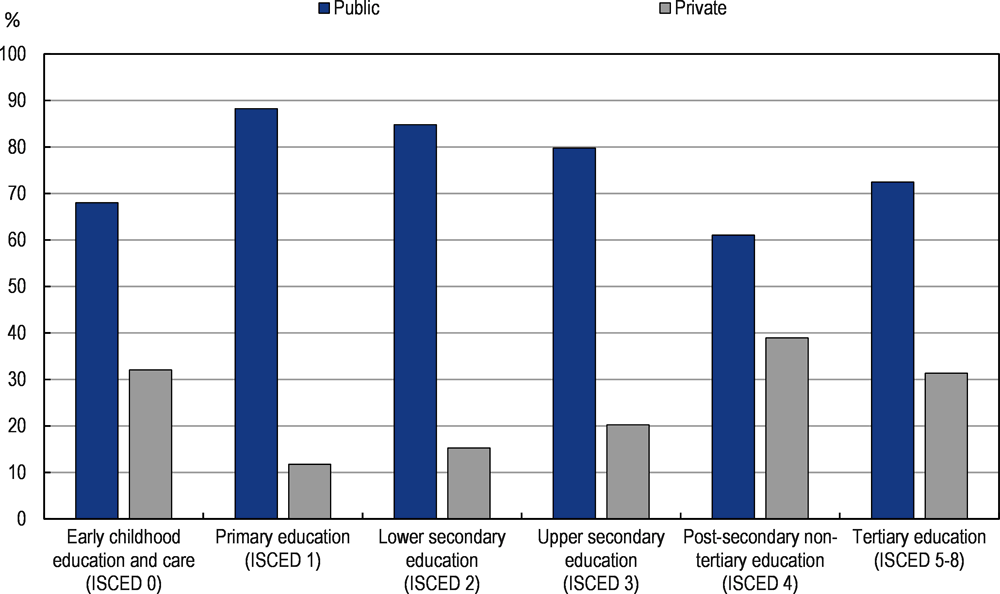

Approximately one-third of children attending ECEC in OECD countries are in private institutions, whereas public institutions are more common at other levels of education.

The concept of quality in ECEC is multidimensional. Children’s daily interactions through their ECEC settings, including with other children, staff and teachers, space and materials, their families and the wider community, reflect the quality of ECEC they experience. Together, these interactions are known as process quality, and are key to supporting children’s learning, development and well-being.

Curriculum frameworks support process quality through several mechanisms, including their content, routines, activities, resources and encouragement of interactions. Articulating a curriculum framework and its links to pedagogy are important policy strategies for enhancing process quality in ECEC.

Curriculum is a powerful tool to create alignment and encourage co-ordination across stages of education. A majority of the curricula covered in Quality beyond Regulations include facilitation of continuity and transitions among their goals. However, with the exception of providing information materials for parents on transitions, fewer than half of ECEC settings covered by the data systematically employ strategies to support transitions.

ECEC staff need strong initial preparation, opportunities to participate in ongoing professional development and supportive working conditions to engage in high-quality interactions with young children. ECEC leaders play an important role in shaping organisational conditions and strategies for ensuring quality, and they themselves need access to appropriate training and support structures to be most effective.

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) holds tremendous potential for children, families and societies when it is of high quality. With expanding access to ECEC, policy makers, practitioners and researchers alike are shifting their focus from expanding the sector's size to ensuring that all children are in settings that support their development, learning and well-being. The benefits of high-quality ECEC are wide-ranging, as are the policy approaches needed to equitably support this sector, which sits at the intersection of education, labour, health and social welfare.

The COVID-19 pandemic underscores the myriad ways in which ECEC matters for individuals and societies. Even as schools closed to limit the spread of COVID-19, in many places, ECEC continued to operate, providing ongoing services at least for children of essential workers (OECD, 2021[1]). Discussions about re-opening economies hinge on the capacity of ECEC systems to support parents’ participation in the labour force. In this context, continuing government commitment to quality is imperative to promote children’s development, learning and well-being throughout and following the crisis, in addition to supporting parental employment.

International comparisons of ECEC systems provide rich information to inform policy developments and meet the rising demand and expectations for ECEC services. The Quality beyond Regulations project was launched to support countries and jurisdictions to better understand different dimensions of quality in ECEC and the policies that can enhance quality, going beyond minimum standards and requirements. The project and this publication focus on two policy areas within ECEC – curriculum and pedagogy and workforce development – that offer strong opportunities for countries to learn from one another, even in the context of highly heterogeneous ECEC systems. Moreover, these policy areas represent core aspects of children’s daily experiences in ECEC, making them important for understanding quality beyond the complex governance and regulatory systems surrounding ECEC.

Research innovations and social changes over recent decades have converged to make policy attention to ECEC widespread. Factors driving this attention include a recognition of the role of ECEC in supporting young children’s rights and well-being, commitments to equal opportunities for women in the labour force and clear evidence from fields as diverse as neuroscience and economics that demonstrates the benefits of high-quality early childhood experiences. Policy makers worldwide recognise the myriad advantages of ECEC, and in this context, enrolment in ECEC is growing. Among children aged 3 to 5 years, participation in ECEC is typical, and universal or near-universal, in several OECD countries (Figure 1.1).

Young children are developing and learning rapidly, setting the foundations for their understanding of the world. ECEC can give a strong start to all children by providing equitable opportunities and experiences that support development, promote well-being and connect families to one another and to resources in the community. Participation in ECEC is linked with both short- and long-term benefits that range across domains. In the short term, these benefits include providing children with opportunities to enjoy exploring their own interests and growing capabilities while developing a sense of belonging. In addition, ECEC helps ensure children have the skills and confidence to transition smoothly into primary school. Families and society also benefit from ECEC in the short term, notably through stronger parental labour market participation.

Children’s early learning and development is closely connected across domains. Cognitive, social and emotional, and self-regulatory skills grow together during early childhood, with gains in one area contributing to concurrent and future growth in other areas (OECD, 2020[3]). Participation in high-quality ECEC supports children’s development in all of these areas, with implications for learning beyond early childhood. For example, children in Denmark who participated in higher quality ECEC performed better on a written exam at the end of lower secondary schooling (ten years after their ECEC participation) than their peers whose ECEC experiences were of lower quality (Bauchmüller, Gørtz and Rasmussen, 2014[4]). Similarly, findings from the United Kingdom show that participation in higher quality ECEC is associated with stronger performance at the end of compulsory schooling, enough to imply a 4.3% increase in gross lifetime earnings per individual (Cattan, Crawford and Dearden, 2014[5]). In addition to educational and economic benefits, quality ECEC can support social and emotional well-being: in a sample from the United States, at age 15, adolescents reported fewer behavioural and emotional problems when they had participated in higher quality ECEC (Vandell et al., 2010[6]).

In the longer term, participation in ECEC positively predicts well-being across a range of indicators in adulthood, including physical and mental health, educational attainment and employment (Belfield et al., 2006[7]; Campbell et al., 2012[8]; García et al., 2020[9]; Heckman and Karapakula, 2019[10]; Heckman et al., 2010[11]; Karoly, 2016[12]; Reynolds and Ou, 2011[13]). In addition to these benefits for individuals, societies benefit in the long term through greater labour market participation and earnings, better physical health and fewer healthcare costs, and lower involvement in criminal activity throughout the life course of individuals who participate in high-quality ECEC (Box 1.1).

Decades of research demonstrate the short- and long-term benefits of high-quality early childhood education and care (ECEC). Although no single study can answer all relevant questions about ECEC and children’s development, learning and well-being, evidence from different types of studies provides a robust picture of the outcomes associated with participation in ECEC. The research summarised here gives examples of different methodological approaches to studying ECEC and children’s outcomes, highlighting studies that have been influential for informing policy.

Longitudinal studies: The Effective Pre-school, Primary and Secondary Education (EPPSE) Project

More than 3 000 children, their families and schools participated in this longitudinal study in United Kingdom (England) that began in 1997. Children were sampled from a range of ECEC settings where information on quality was collected through observations. A comparison group of children who did not attend ECEC was recruited upon school entry. Researchers followed the entire sample of children through age 16. Findings show the enduring importance of ECEC experiences throughout childhood and adolescence: any participation in ECEC, longer duration of ECEC participation and better quality of ECEC settings all strengthen children’s holistic learning, development and well-being, beyond individual and family background characteristics (Sylva et al., 2004[14]). For example, attending ECEC for longer was associated with students being more than four times as likely to pursue a higher academic education versus a vocational training pathway at the end of compulsory schooling (Taggart et al., 2015[15]). Importantly, EPPSE findings show that despite some fadeout in the advantage of ECEC participation for test scores during intermediate levels of schooling, individuals who attended higher quality ECEC programmes showed stronger academic performance and better social and emotional skills at age 16 (Cattan, Crawford and Dearden, 2014[5]). Although results are strictly correlational, longitudinal studies like EPPSE are important for understanding how families with different characteristics engage with ECEC systems and subsequent developmental trajectories of children.

Random assignment studies: Perry preschool

The Perry Preschool Project was implemented in the United States in the 1960s and involved 123 low-income African-American children. Of these children, 58 were randomly assigned to receive a high-quality preschool programme as well as home visits. Despite the small sample, this study is notable for several reasons. First, the study participants are still being followed, providing a long-term perspective on participation in ECEC. Second, the programme used an experimental design, with random assignment of children to the treatment and control groups. This research design allows strong conclusions about the causal effects of ECEC on outcomes later in life. Although the study participants had many experiences between early childhood and the assessments in adulthood, the one factor that systematically distinguishes them is their status in the treatment versus control groups. Analysis of outcomes for study participants at age 40 suggests that the programme's return-on-investment is USD 7-12 for each dollar invested at age 4. These returns reflect that children who participated in the high-quality preschool programme subsequently had less participation in special education programmes, greater educational attainment, greater employment and earnings and less reliance on social benefits, as well as less engagement in criminal activity (Heckman et al., 2010[11]). Notably, participation in high-quality ECEC also appears to transfer to the second generation, with children of programme participants benefiting as well (Heckman and Karapakula, 2019[16]).

Natural experiments: A meta-analysis

Researchers in the Netherlands conducted a meta-analysis of studies evaluating the effects of universal ECEC on children’s outcomes conducted between 2005 and 2017 in Australia, Canada, United Kingdom (England), France, Germany, Spain and the United States (Van Huizen and Plantenga, 2018[17]). The studies included in the analysis all took advantage of natural experiments, for example, by using regional variation in the timing of ECEC expansion or by comparing children who participated a year earlier than closely aged peers due to strict age-eligibility thresholds. This research approach better accounts for family selection into ECEC (i.e. all families are not equally likely to enrol their children in ECEC) than is possible in correlational studies such as EPPSE, for example. It also gives an assessment of the value of universal ECEC, rather than targeted programmes (i.e. programmes that serve only some segments of the population by design) such as Perry Preschool. Results from this analysis highlight the heterogeneity in findings from studies of universal ECEC, and in particular show mixed findings on the importance of ECEC starting age. However, the results also show that high-quality ECEC (defined by staff-to-child ratios and staff educational requirements) and public provision of ECEC (versus private) consistently lead to stronger outcomes for children. In addition, children from socio-economically disadvantaged households show greater gains from participation in universal ECEC than their more advantaged peers.

Source: Cattan, S., C. Crawford and L. Dearden (2014[5]), “The economic effects of pre-school education and quality”, https://doi.org/10.1920/re.ifs.2014.0099; Heckman, J. and G. Karapakula (2019[16]), “Intergenerational and intragenerational externalities of the Perry Preschool Project”, hceconomics.org; Heckman, J. et al. (2010[11]), “The rate of return to the HighScope Perry Preschool Program”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.11.001; Sylva, K. et al. (2004[14]), “The Effective Provision of Pre-school Education (EPPE) Project: Findings from Pre-school to end of Key Stage 1”, https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/18189/2/SSU-SF-2004-01.pdf; Taggart, B. et al. (2015[15]), Effective Pre-school, Primary and Secondary Education Project (EPPSE 3-16+): How Pre-school Influences Children and Young People's Attainment and Developmental Outcomes Over Time, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/455670/RB455_Effective_pre-school_primary_and_secondary_education_project.pdf.pdf; Van Huizen, T. and J. Plantenga (2018[17]), “Do children benefit from universal early childhood education and care? A meta-analysis of evidence from natural experiments”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.08.001.

Despite growing ECEC enrolment and recognition of the value of high-quality ECEC, investments in this sector remain below those for later stages of education. On average in 2017, OECD countries spent 0.86% of gross domestic product (GDP) on ECEC compared with 1.46% and 1.95% of GDP on primary and secondary education, respectively (OECD, 2020[2]). In some countries, pre-primary education has a shorter duration than primary education, potentially justifying lower overall expenditures; however, the proportion of private spending in total spending is higher for pre-primary education than for primary education, highlighting the gap between funding that is needed in the sector and public investments. Moreover, following rising investments in ECEC during around the turn of the 21st century, expenditures on ECEC levelled off, or even decreased in many countries, between 2013 and 2017 even in the context of overall economic growth during this period (OECD, 2006[18]; 2020[2]). As policy makers commit to implementing high-quality ECEC by building systems that go beyond regulating basic features of ECEC, these issues of spending will require ongoing attention.

The prominent role of private institutions in the ECEC sector further highlights differences with later stages of education. Approximately one-third of children attending ECEC in OECD countries are in private institutions, whereas public institutions are more common at all other levels of education (except post-secondary non-tertiary education; Figure 1.2). The reliance on private institutions to provide ECEC can permit faster expansion of the supply of ECEC settings than would be possible for governments on their own. At the same time, the monitoring and governance of private settings can present challenges for ensuring equitable, affordable access to high-quality ECEC for all children, even when private institutions receive public funding.

The average percentage of children in ECEC in private settings in OECD countries hides important variation both within levels of ECEC and across countries. Regarding levels of ECEC, children under age 3 years are much less likely to attend public ECEC settings than children in pre-primary education. However, in countries that rely heavily on private provision of ECEC, the private sector is also responsible for most pre-primary education as well. For example, more than three-quarters of children attending pre-primary education are in private settings in Australia, Ireland, Japan, Korea and New Zealand (OECD, 2020[2]).

Expenditure per child in pre-primary education is similar to spending per student in primary school but lower than spending per student at higher levels of education across OECD countries (OECD, 2020[2]). Stronger per-child investments enable conditions that support high quality but must be weighed against the number of children served in the ECEC system (Bowne et al., 2017[19]). For example, smaller class sizes and more favourable child-staff ratios can support staff to interact effectively with individual children. However, the costs of increasing staffing need to be balanced with other strategies to enhance quality, such as investments in staff training and professional development.

Per-child expenditures in pre-primary education vary greatly across OECD countries (Figure 1.3). Several countries, notably Nordic countries, combine strong investments per child with widespread access to ECEC (OECD, 2020[20]). However, differences in per-child expenditures on ECEC across countries do not necessarily reflect lower prioritisation of this sector as a whole. For example, Israel’s per-child expenditures on ECEC are below the OECD average, but their expenditure on pre-primary education was 0.96% of GDP in 2017, well above the OECD average of 0.63% (OECD, 2020[2]). The lower per-child expenditures in Israel reflect widespread enrolment of young children in ECEC, particularly among children under age 3. Countries need different policy and investment approaches to ensure high-quality ECEC, considering relevant contexts and related policies, such as women’s labour force participation and access to parental leave.

Policy makers want to better understand the successes of public investments in the early years and also identify areas for improvement. Research consistently underscores the importance of ensuring ECEC is of high quality to support children’s well-being and to realise the numerous benefits of focusing on this period of the life course. Although the concept of quality in ECEC is multidimensional, convergence in research findings from multiple countries suggests some core aspects of quality (Edwards, 2021[21]; OECD, 2018[22]; Melhuish et al., 2015[23]). Specifically, children’s daily interactions through their ECEC settings, including with other children, staff and teachers, space and materials, their families and the wider community, reflect the quality of ECEC they experience. Together, these interactions are known as process quality.

Process quality in ECEC settings is directly linked to children’s development, learning and well-being (OECD, 2018[22]). However, process quality depends on multiple factors, presenting challenges for regulation and policy solutions. Aspects of ECEC quality that are traditional targets of policy, such as child-staff ratios, group sizes, the physical size of settings, curriculum frameworks and minimum staff qualifications, create conditions to support good process quality (Burchinal, 2018[24]; OECD, 2018[22]; Pianta, Downer and Hamre, 2016[25]). These aspects of ECEC quality, often known as structural quality, are not, on their own, sufficient to ensure high process quality and promote children’s development, learning and well-being. In addition to structural aspects of ECEC quality, factors that shape children’s interactions in their ECEC settings include staff’s capacity to adapt to individual children’s needs and interests, engagement in different types of activities throughout the day, continuity of staff members throughout the day and year, and characteristics of children themselves, such as temperament, that matter for how individual children experience the same classroom or playgroup. With all of these factors contributing to children’s daily experiences, process quality can be hard to assess and quantify, especially on a large-scale basis, making it difficult to identify policy levers that best support process quality.

The complex nature of quality in ECEC requires multifaceted policy solutions. This report builds on a conceptual framework to analyse the main drivers of process quality summarised in Figure 1.4. Policies instrumental for building ECEC systems that can foster process quality are grouped into five broad areas: governance, standards and funding; curriculum and pedagogy; workforce development; data and monitoring; and family and community engagement (OECD, 2012[26]). The Quality beyond Regulations project focuses on key aspects of curriculum and pedagogy (curriculum frameworks and goals; curriculum design and implementation; pedagogical approaches) and workforce development (delivery of staff training; working conditions; content of staff training) that closely support high-quality interactions in ECEC settings. The cross-cutting importance of family and community engagement, and of monitoring and data is noted in many of the specific policies investigated through the project.

Although governance, standards and funding are not an explicit focus of the Quality beyond Regulations project, they are considered the foundation for all other policies to support quality in ECEC. Without a strong foundation, the broad scope of policies necessary to enhance process quality and foster children’s well-being are unlikely to be sustainable and successful. For example, ensuring consistent funding for ECEC services allows growth in other policy areas, such as around delivering staff training. Understanding the basis for ECEC policy through governance, standards and funding is essential for ensuring that other policy levers successfully support process quality. This aspect of ECEC policy is also critical for comparing other policy approaches across jurisdictions and countries, given the wide variation in ECEC systems.

The Quality beyond Regulations policy review was initiated to support countries and jurisdictions to better understand the different dimensions of quality in early childhood education and care (ECEC), focusing on process quality in particular. The first phase of the project culminated in a literature review and meta-analysis of the links between different dimensions of quality and children’s learning, development and well-being, published under the title Engaging Young Children (OECD, 2018[22]).

The second phase of the project builds from this research base to address the overarching question: How can policies enhance process quality and child development and what are good examples of these policies? To address this question, countries in the OECD’s Early Childhood Education and Care Network were invited to share information on relevant policies by completing a questionnaire. Twenty-six countries responded to this invitation, resulting in a rich database of information on ECEC systems around the world and their efforts to promote high-quality ECEC as of the year 2019.

In addition, six countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland, Japan, Luxembourg and Switzerland) participated in the Quality beyond Regulations project by completing in-depth country background reports. These reports were undertaken by national governments, as well as provincial governments in Canada. The reports were based on a common framework developed by the OECD to facilitate comparative analysis and maximise the opportunities for countries and jurisdictions to learn from each other. The country background reports are complementary to the information collected in the policy questionnaire. Together, these two sources provide the data for the main analyses presented in this publication.

Ensuring that ECEC systems provide high quality to meet growing demand and address the needs of different segments of the population is a challenge for governments. The needs of diverse families, including those with very young children, children with special education or additional needs, immigrant, refugee and language-minority families, and families of different socio-economic backgrounds, span multiple policy areas. Innovative strategies are required to promote coherence and co-ordination across policies and services. Beyond providing a sufficient supply of ECEC to meet demand, the sector must also deliver these services in a holistic way that is responsive to the diversity of children and families.

Partnering with families and communities to identify needs and barriers to participation in ECEC is key to successfully meeting the challenges of serving increasingly diverse children. Parents are children’s first teachers, and strong partnerships between families and ECEC promote children’s social and cognitive development (Cadima et al., 2020[27]). The capacity of educational settings to support family engagement is also closely linked with children’s learning and well-being (Ma et al., 2016[28]). Although essential throughout children’s educational trajectories, co-operation between families and ECEC is especially important in the early years.

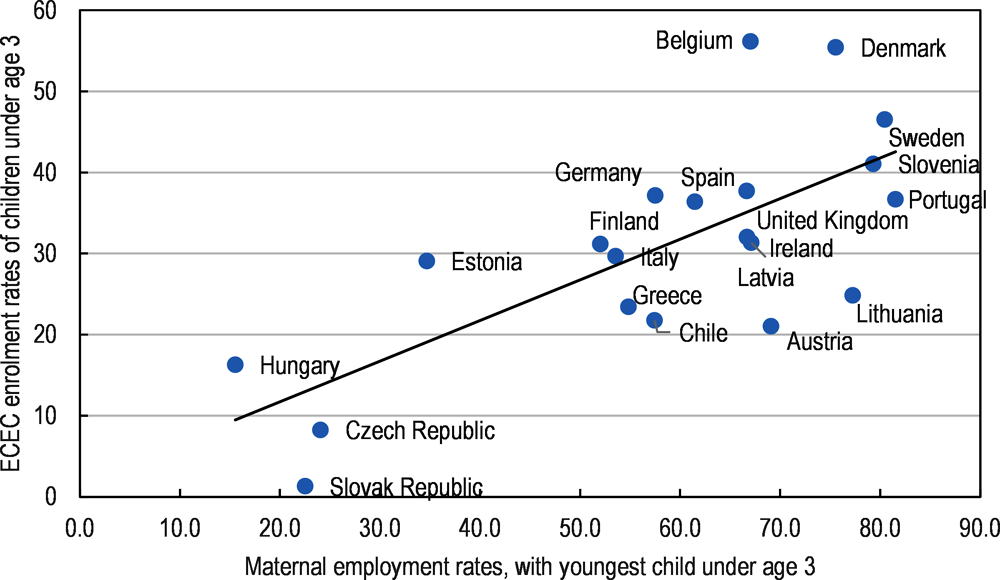

The ECEC sector for children under age 3 years highlights, in particular, the intersection of policies around parental labour market participation and the benefits of education and care beyond the family for very young children. Enrolment of children under age 3 in ECEC is increasing across OECD countries (Figure 1.5). Although still more variable than participation of children ages 4 or 5 years, the growth in ECEC enrolment among children under age 3 can place strain on systems that are funded and designed to engage mainly with pre-primary age children. Children under age 3 are growing and learning at a faster rate than at any other time in their lives, including acquiring early language skills and developing independent mobility. The rapid changes characteristic among this age group require that ECEC settings be specifically adapted to the evolving needs of these children. At this age, the integration of care and education is paramount, as routine caregiving activities (e.g. meals, diaper changes) require significant time but are meaningful occasions to support children’s well-being, positive development and early learning (Cadima et al., 2020[27]). Well-trained ECEC staff with appropriate space and adequate resources can provide rich environments and interactions through which very young children have opportunities to develop across sensorimotor, language and social domains.

Even with increasing enrolment, demand for ECEC for this young age group can outpace supply, resulting in waiting lists for services (OECD, 2020[29]). As a result, families often must choose between forgoing labour force participation or placing children in settings of uncertain quality, including informal or unregulated settings (OECD, 2020[20]). Yet, public investments are disproportionately made for pre-primary education compared with education and care for children under age 3 (OECD, 2020[2]). To ensure all children under age 3 have equitable access to high-quality ECEC, governments increasingly need strategies and investments that are adapted to developing a robust sector of services for the full age range of children prior to primary school. The ECEC sector is comprised of many different types of services, such as centre-based programmes, services provided in the home of a caregiver/educator, paid services in the home of a child, as well as informal arrangements with family, friends or neighbours. This range of services can enable families to find options that fit best with their preferences and needs; however, these services come with a range of public funding and regulations, meaning that quality is also variable. Countries and jurisdictions must work within existing structures and strengths of this mixed delivery system to enhance quality while further developing the supply of ECEC for children under age 3 years.

High-quality ECEC is well-positioned to identify children with, or at risk for, physical, mental, emotional, social, or learning impairments and assist families in accessing early intervention services. Intervening early can eliminate or mitigate the challenges children with special education or additional needs face as they progress through education systems and find their roles in society. At the same time, ensuring children with special education or additional needs have a place in ECEC has not always been at the forefront of ECEC policy. However, the importance of inclusive education systems more generally is gaining visibility (Brussino, 2020[30]). With this growing attention, it is not surprising that in many countries, working with children with special education and additional needs is the area reported by the largest share of staff as being of high need for ongoing professional development (OECD, 2019[31]).

ECEC is also a powerful way to support immigrant, refugee and language-minority families, in terms of parents’ transition into the labour force, familiarisation with systems and culture in the receiving country and support for children’s learning, development and well-being. Migration into OECD countries is increasing and reflects a heterogeneous population from all over the world with varying levels of human capital (OECD, 2019[32]; 2019[33]). On average, between 2003 and 2015, the population of 15-year-old students with an immigrant background grew by more than 6% in OECD countries (OECD, 2019[32]). In addition, the number of children in the world who are refugees more than doubled between 2005 and 2015 (UNICEF, 2016[34]).

Data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) show that participation in at least one year of ECEC is associated with stronger performance in science at age 15 among students from immigrant families, and the benefits of earlier participation in ECEC is particularly strong for immigrant, compared to native, students (OECD, 2017[35]; Shuey and Kankaras, 2018[36]). Similarly, multilingualism can be a valuable asset, but for young children, a home language that is different from that of the schooling sector and ECEC also has important implications for their ability to interact with their peers and teachers and demonstrate mastery of emerging skills. The OECD’s International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study, which collected data in Estonia, the United Kingdom (England) and the United States, found that children who are learning a different language at home compared with school or ECEC had lower scores on early literacy, numeracy and self-regulation tasks at age 5 compared to their peers whose home language matched that of their ECEC or school setting (OECD, 2020[3]). The growing numbers of children from diverse migration and language backgrounds, coupled with the importance of ECEC for these children in particular, underscores the critical role of ECEC systems that are prepared to work effectively with language and cultural diversity.

Families of different socio-economic backgrounds represent yet another type of diversity in ECEC settings. On average, in OECD countries, one in seven children lives in poverty, increasing their risk of material deprivation, including poor nutrition and unstable housing (OECD, 2019[37]). In addition, children from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds hear, on average, fewer words in their home environments compared to their more advantaged peers (Rowe, 2017[38]). These early differences matter for how children adapt to and engage in their ECEC settings. ECEC staff must be attuned to the different early experiences of children in their classroom or playgroup and recognise how these differences may shape individual children’s needs, behaviours and well-being. To this point, evidence from France demonstrates that within an ECEC system with strong regulations, children who participate in centre-based ECEC have an early advantage in language skills compared to their peers who do not participate in this type of ECEC. Importantly, the positive impact of centre-based ECEC on language skills is particularly concentrated among children from disadvantaged backgrounds (Berger, Panico and Solaz, 2020[39]).

Many children and families represent multiple domains of diversity and may fall into several of the categories described in this section, as well as others (e.g. family gender composition, ethnic group membership). The intersectionality across different domains of diversity requires ECEC staff and leaders to engage in continuous learning to work with families that may differ from their own or who may be minorities in the local or national context.

ECEC is a powerful policy tool to reduce inequalities and help all children have strong foundations for learning and well-being. Much of the policy attention on ECEC in recent years stems from an interest in breaking intergenerational cycles of poverty by engaging more parents in the labour force and helping all young children develop a sense of connection and belonging, a love of learning and abilities that will support them to engage in their own education. With the increasing diversity of children and families, countries and jurisdictions are aware of the need to continue focusing on equitable access to the benefits of high-quality ECEC.

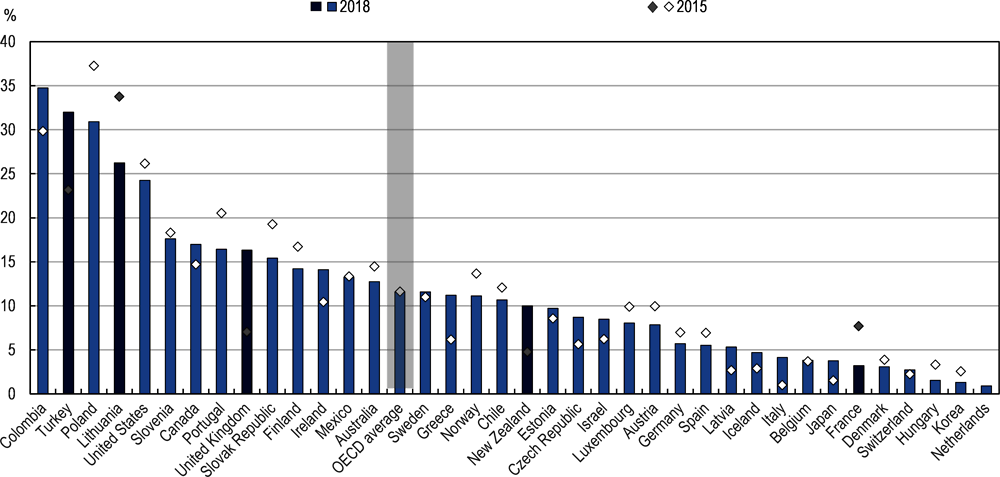

In general, children from socio-economically disadvantaged families are less likely than their more advantaged peers to participate in ECEC (OECD, 2017[35]). This difference in ECEC access compounds with other sources of family, neighbourhood and societal disadvantage, creating gaps between children of different backgrounds that widen as they advance through school (OECD, 2017[40]). Among students who participated in PISA in 2018, the vast majority reported having attended ECEC, and the typical number of years of participation increased in most countries between PISA 2015 and PISA 2018 (OECD, 2020[41]). However, gaps in ECEC participation persist based on students’ socio-economic background. The PISA 2018 data show that, on average across OECD countries, 86% of students from socio-economically advantaged backgrounds attended ECEC for at least two years, whereas this was the case for 74% of their less advantaged peers. There is substantial variation in this gap across countries, although this problem of equitable enrolment in ECEC is common (Figure 1.6). Importantly, the gap in ECEC participation between students of different socio-economic backgrounds did not change much on average across OECD countries between PISA 2015 and PISA 2018, suggesting that despite overall trends of growing participation in ECEC, equity remains an issue.

Findings from PISA provide valuable insight into the links between students’ socio-economic background and participation in ECEC in a comparable manner across countries. However, students participating in PISA in 2018 attended ECEC settings more than a decade ago. The landscape of ECEC services has shifted to varying degrees across participating countries in the intervening time. In addition, PISA findings rely on students’ memories of their ECEC participation. Thus, although the PISA data are an important indicator of how ECEC is associated with later stages of education systems internationally, findings must be interpreted with these caveats in mind.

More recent European data confirm that in many countries, young children from socio-economically disadvantaged families and those with less-educated mothers are less likely to participate in formal ECEC than their peers from more advantaged or educated families (Adema, Clarke and Thévenon, 2016[42]). These disparities in access to ECEC based on family background create a situation whereby families lose opportunities to raise their socio-economic profiles through parental participation in ongoing education or the labour market, and children simultaneously are not afforded the benefits of participating in high-quality ECEC.

One reason children from socio-economically disadvantaged families are less likely to participate is the costs associated with ECEC. Although parents have access to help with childcare costs in all OECD countries, the extent and type of support are highly variable. As a result, for many lower-wage workers, forgoing labour market participation and keeping young children at home can make financial sense (OECD, 2020[20]). The quality of ECEC opportunities may be a contributing factor in whether families access these programmes. Quality can be lower in areas where socio-economically disadvantaged families live, especially when private versus public provision dominates, but socio-economic segregation can occur even in contexts with substantial public investments (Drange and Telle, 2021[44]; Hatfield et al., 2015[45]; Vandenbroeck, 2015[46]). To the extent that families are concerned with the quality of available ECEC, they may choose, or feel compelled, to keep their children at home or seek informal childcare arrangements.

Strategies to equitably increase participation in ECEC include increasing the provision of free ECEC, for at least some hours, ages or targeted population groups. Universal free access to at least one year of ECEC is now common across OECD countries, and having readily available, high-quality ECEC can encourage broad participation from diverse families. However, universal free access to ECEC is typically targeted to pre-primary education, potentially limiting the available public resources to support the learning, development and well-being of children under age 3 years (OECD, 2017[35]). Countries and jurisdictions must carefully balance their investments to increase access to high-quality ECEC for children throughout the full age range of early childhood. Universal free access helps ensure ECEC can meet its goal of reducing inequalities by improving both affordability and accessibility for the most disadvantaged families. It is one tool governments can use along with others, such as regulatory frameworks, to foster high-quality ECEC across settings that are both publicly and privately managed, or mechanisms to adapt ECEC settings to the needs and preferences of more disadvantaged families to encourage their participation in particular (OECD, 2020[20]; Blanden et al., 2016[47]).

The COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate inequitable enrolment in ECEC and mean that more children miss opportunities to participate in ECEC. Not only is the pandemic deepening existing economic inequalities, but providing continuity of opportunities to support the education and development of this age group is even more challenging than at later stages of education. Young children require close contact with others to meet their basic needs, ensure their safety and promote their learning and well-being: these functions of ECEC cannot be replaced by even the best distance learning platforms.

Unequal participation in ECEC according to children’s socio-economic backgrounds is likely to be intensified by rising unemployment due to the pandemic, with women experiencing some of the steepest job losses (OECD, 2020[48]). Between unemployment, reduced availability of ECEC and health risks of engaging in low-wage work outside the home, more disadvantaged families are likely to decide that caring for children at home makes health and economic sense.

Before the pandemic, mothers’ labour market participation and enrolment rates in ECEC were closely linked (Figure 1.7). Government support is needed to ensure that children can continue to engage in ECEC despite the current growth in unemployment, for example, by expanding the provision of free or subsidised ECEC to more children, including targeting families who have income losses due to furloughs or unemployment. Financial supports that are provided to families to access ECEC also need to meet families’ needs in a timely fashion, at the time they are required to pay for ECEC, rather than relying exclusively on tax-based measures that may provide support only on an annual basis (OECD, 2020[20]).

Women who are more educated and those who are employed before the birth of their children already enrol their children in ECEC at higher rates than those who are less-educated or unemployed (Adema, Clarke and Thévenon, 2016[42]). These are also critical determinants of household economic resources. Higher-income families tend to provide more stimulating and responsive interactions in the home-learning environment (Burchinal et al., 2015[49]). These interactions foster children’s early cognitive skills as well as their socio-emotional skills (OECD, 2020[3]). Emerging evidence suggests job and income losses during the pandemic are associated with negative parent-child interactions among socio-economically disadvantaged families; however, for parents who lost jobs without losing income, parent-child interactions were more positive (Kalil, Mayer and Shah, 2020[50]). Finding ways to support less affluent parents as early teachers is an important policy direction that is amplified in the context of job losses and ECEC closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Furthermore, parents’ time and capacity to engage in home-learning activities are likely strained through the pandemic. Estimates based on the OECD Survey of Adult Skills, a product of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), suggest that approximately 31% of workers on average in OECD countries could feasibly work from home, with large disparities based on education and skills (Espinoza and Reznikova, 2020[51]). For workers with lower education and skills, this difference means an increased likelihood of unemployment in sectors where in-person work is limited during the pandemic (e.g. hospitality) or an ongoing need for high-quality ECEC to ensure children’s development, learning and well-being when parents must continue going to work outside the home. Continuing employment outside the home throughout the pandemic may be detrimental to children's well-being to the extent parents are risking exposure to COVID-19, reinforcing the need for high-quality ECEC services to support both children and their parents (Kalil, Mayer and Shah, 2020[50]). For parents who are able to telework, balancing children’s care and education at home is creating a new set of demands and ways of managing work and family responsibilities. For families in all of these situations, access to high-quality ECEC continues to be a necessity.

Curriculum frameworks support process quality through several mechanisms, including their content, routines, activities, resources and encouragement of interactions (Edwards, 2021[21]). Curriculum frameworks can vary greatly, particularly in ECEC compared with other levels of education, where the need for a structured approach to learning and to teaching is well accepted (Nesbitt and Farran, 2021[53]). Yet, curriculum frameworks adapted to the settings in which they are employed, including to the ages of children, are a key support to orient staff in their practices and a way to build shared goals across different types of provision within the ECEC system.

Pedagogy can be a set of foundational beliefs that underpin a curriculum or specific practices that emerge through the implementation of the curriculum (Edwards, 2021[21]). Articulating a curriculum framework and its links to pedagogy are important policy strategies for enhancing process quality in ECEC as this process makes explicit the values and beliefs embedded in the system, for instance, related to children’s rights, to enriching experiences, or to expectations for short- or longer-term learning outcomes. As such, a curriculum framework is an important tool to support quality across the full age range covered by ECEC, including children under age 3 years (Chazan-Cohen et al., 2017[54]). However, the Quality beyond Regulations data show that several countries do not have curriculum frameworks that cover this early period of the life course. In other countries, the curriculum frameworks for this age group are not mandatory (Chapter 2). These findings underscore the need for a better understanding among policy makers of the meaning and importance of curriculum and pedagogy for this age group.

At the other end of the spectrum in terms of the availability of curriculum frameworks, many countries and jurisdictions participating in Quality beyond Regulations have multiple different curriculum frameworks in place for the same or overlapping age groups. This situation reflects the complexity of services and settings within the ECEC sector but also creates challenges for staff to navigate and align resources in practice. Furthermore, different curriculum frameworks for different ECEC settings can contribute to uneven quality throughout the sector, potentially reinforcing inequitable access to high-quality ECEC for some children.

In addition to supporting ECEC staff in their work with children, curriculum frameworks can support staff to engage with families, as well as support families to create home environments conducive to children’s learning, development and well-being. Participation in high-quality ECEC is associated with greater parental warmth, provision of developmental stimulation, school involvement, and less use of physical discipline, highlighting the potential for ECEC staff to support interactions between children and their families (Love et al., 2005[55]; Mersky, Topitzes and Reynolds, 2011[56]; Zhai, Waldfogel and Brooks-Gunn, 2013[57]). Curriculum frameworks can help ECEC staff foster interactions with families by setting expectations around this engagement and providing examples of strategies to foster such engagement. Importantly, curriculum frameworks can also be targeted to families, and in this way, encourage connections and continuity between the home and ECEC environments, contributing to children’s social-emotional skills and early learning outcomes (OECD, 2020[3]).

ECEC does not operate in isolation for children and families, nor should it be viewed as entirely separate from later stages of education. Curriculum is a powerful tool to create alignment and encourage co-ordination across stages of education, whether within ECEC (i.e. between settings for children under age 3 years and pre-primary education) or across levels of education. These transition points offer opportunities to ensure the benefits of high-quality ECEC endure beyond early childhood and to improve equity in educational outcomes (OECD, 2017[58]).

The fact that young children are developing rapidly and learning new things through all of their daily experiences creates specific challenges for defining goals in curriculum frameworks for this age group, as well as for alignment with later stages of education. Yet, curriculum frameworks provide an opportunity to identify cultural and ideological values around learning and teaching that are relevant across multiple phases of the educational continuum (Edwards, 2021[21]). This process of identifying key values can situate ECEC as a fundamental component of education systems, for example, by defining overarching goals relevant throughout the system, such as respect for diversity or promoting well-being and belonging.

Broad goals and principles are useful for developing curriculum frameworks that are relevant and adaptable to the wide age and developmental ranges covered by ECEC. However, the impact of such high-level frameworks can be difficult to assess, particularly compared to more skills-specific curricula that have clear links to discrete child outcomes (Jenkins and Duncan, 2017[59]). The pressures of “school readiness” rhetoric can push responsible authorities to adopt curriculum frameworks for ECEC that emphasise learning areas similar to those in later stages of education. This, in turn, raises concerns about the “schoolification” of ECEC if children’s holistic development and well-being, including the fundamental role of play, are not also clearly supported through the curriculum framework (Needham and Ülküer, 2020[60]). Nevertheless, providing content-specific material and goals in curriculum frameworks can help ensure that staff have ample opportunities for rich interactions with children, creating higher quality environments (Denny, Hallam and Homer, 2012[61]; Wysłowska and Slot, 2020[62]). As such, countries and jurisdictions must strike a balance in their curriculum frameworks to support specific areas of learning and engagement between children and staff while keeping a holistic approach to children’s development and being adaptable to the ages and stages of young children.

Among countries and jurisdictions participating in Quality beyond Regulations, the alignment of ECEC curricula with traditional learning areas is most evident in curricula for pre-primary education, compared with curricula that span a wider age range or those for children aged 0 to 2 years. The developmental or learning goals of curriculum frameworks for pre-primary education more often focus on traditional learning areas, whereas the goals of frameworks for younger children or a broader age group are more often framed around broad strands of concepts and competencies and principles and values (Chapter 2). Strengthening the use of shared goals across levels of ECEC and into later stages of education can facilitate continuity and support transitions for children as they grow. This does not depend on ECEC curriculum frameworks replicating or becoming a downward extension of primary education. Rather, a focus on transitions underscores the place of ECEC as part of the continuum of education with shared goals across levels while recognising important and unique features of the early childhood period.

A majority of the curricula covered in Quality beyond Regulations includes facilitation of continuity and transitions among their stated goals (see Table C.2.2). Nonetheless, the specific strategies that are required or are common practice in countries and jurisdictions to support children’s transitions are somewhat limited (Figure 1.8). With the exception of providing information materials for parents on transitions, fewer than half of settings covered by the data systematically employ strategies to support transitions. This is an area where countries and jurisdictions can implement policies to improve quality, such as by building systems for ECEC settings to share child records with one another, with families and with primary schools.

Continuity across curriculum frameworks from ECEC to primary school and beyond not only supports smooth transitions. It can also ensure the focus of learning approaches is well-suited to children’s level of development and that content builds, rather than repeats, from one stage to another. Creating this type of progression from ECEC to primary school may address the criticism that learning gains from ECEC “fade out” as children grow, by avoiding overlaps in material presented to children at these two levels of education (Jenkins and Duncan, 2017[59]). Whereas in the past, compulsory education typically coincided with the start of primary school, a growing number of countries mandate participation in at least some pre-primary education (OECD, 2020[2]). These changes are often an effort to improve equity by ensuring access to ECEC for children from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds. However, they may fail to support longer-term learning goals if progression and alignment in curriculum frameworks are insufficient.

Approaches to children’s learning, development and well-being in primary schools also need to adapt to reflect the needs of cohorts of children who have increasingly had access to ECEC. The Heckman Curve (Heckman, 2006[63]) is often cited to advocate for increased government expenditures in early childhood: it argues that the rates of return to human capital investment diminish throughout the life course, meaning that ECEC investments will yield better societal and economic returns than investments in later stages of education. However, critiques of the Heckman Curve caution that more research is needed on the specific types of investments needed to ensure ECEC delivers high rates of return and demonstrate that investment in high-quality education at later stages can also be cost-effective (Rea and Burton, 2020[64]; Whitehurst, 2017[65]). With this perspective, governments must continue to examine how best to integrate ECEC into their educational systems, with attention to investments in primary school and beyond as well. ECEC systems have many strengths that can inform improvements to other stages of education, such as tailoring activities to the needs and interests of different children, engaging with families, and addressing children’s learning from a holistic perspective that includes well-being and socio-emotional development, alongside traditional academic learning areas.

The ECEC workforce is central to ensuring high-quality ECEC for all children. However, in part due to historical views of childcare as unpaid women’s work, this essential workforce is not always regarded in light of the professionalism required for the sector. With research demonstrating the importance of well-educated ECEC staff for providing high-quality ECEC, policy makers are giving greater attention to the minimum qualifications of this workforce (Manning et al., 2017[66]; OECD, 2018[22]). ECEC staff need strong preparation to engage in high-quality interactions with multiple young children simultaneously, as well as to support children’s interactions among each other and with materials in the ECEC setting. In addition, building strong relationships with families to promote continuity across ECEC and home environments can be supported through initial and ongoing staff training.

Across countries, the most prevalent qualification for ECEC teaching staff is a tertiary qualification (OECD, 2020[2]). However, educational requirements for ECEC staff vary substantially within countries. For example, within countries, staff credentialing in different types of ECEC settings can be subject to different regulatory requirements. This situation can create sharp divides within the sector, with some ECEC staff having educational background similar to that of primary school teachers and others having markedly less formal education. These gaps can correspond to differences in the pre-primary sector versus settings for children under age 3 years, with lower educational requirements for staff in the latter group in particular. The differences in staff educational attainment at these two levels of ECEC reflect the different value placed on education versus care, despite their interwoven nature in ECEC settings. This distinction also comes into play in different training profiles among teachers and assistants, even within the pre-primary sector (Van Laere, Peeters and Vandenbroeck, 2012[67]).

In addition, many countries face shortages of ECEC staff, which creates challenges for raising educational requirements or enforcing existing standards. For example, in Iceland, pre-primary teachers are required to have training at a master’s level, but a shortage of qualified staff means that in practice, nearly half of staff have secondary schooling as their highest level of education (OECD, 2019[31]). Data from the Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS Starting Strong) show that novice (i.e. those who have been in the field for three years or less) and more experienced ECEC staff have similar profiles of initial education (OECD, 2020[68]). This finding suggests that enhancing initial education may be an area where changes in policy or greater attention to implementation can impact ECEC quality through the workforce of the future. The breadth of training of ECEC staff is particularly important to consider, as staff whose training included a greater number of thematic areas reported a stronger sense of self-efficacy; when coupled with breadth in ongoing professional development as well, staff reported using more practices that engage children according to their individual backgrounds, interests and needs (OECD, 2020[68]).

Professional development opportunities help staff with different levels of education and experience adapt to changing needs of children and families, keep abreast of best practices in the field and generally engage in the rich interactions that constitute process quality. Research demonstrates that professional development can improve process quality and support children’s learning, development and well-being (Egert, Fukkink and Eckhardt, 2018[69]; OECD, 2018[22]). However, more than half of staff participating in TALIS Starting Strong reported that a barrier to participating in professional development was not having enough staff to compensate for their absence (OECD, 2019[31]). With tight budget constraints in addition to staff shortages, ECEC settings may be ill-equipped to help their staff members access ongoing professional development. Moreover, on average across OECD countries, pre-primary staff spend more time in direct contact with children than teachers at other levels of education, leaving less time for professional development (OECD, 2020[2]). For these reasons, professional development strategies for ECEC staff must include opportunities for on-site learning and informal collaboration, in addition to building capacity for staff to engage in more traditional professional development activities.

Despite relatively high educational requirements for staff in some segments of the ECEC sector and expectations of participation in ongoing professional development, salaries have not necessarily kept pace. Per net hour of contact time with children, salaries of pre-primary teachers are below those of their colleagues teaching in primary schools in many OECD countries (OECD, 2020[2]). Improving salaries and opportunities for career progression can be a long-term objective for the ECEC sector as governments continue to focus on strategies to ensure high-quality ECEC for all children. This objective is a way to improve staff retention and the capacity of the ECEC sector to attract good candidates, as well as a strategy to support process quality. TALIS Starting Strong data show that staff have generally high satisfaction with their jobs, but low satisfaction with their salaries, and that staff who feel more valued by society also report adapting their practices more often to meet the needs and interest of individual children (OECD, 2019[31]). Striking the right balance between initial education requirements, participation in continuous professional development and elevating the professional status of ECEC staff with salaries commensurate to their education and training is a central policy challenge moving forward.

ECEC leaders can create organisational conditions that support process quality and thereby children’s learning, development and well-being (Douglass, 2019[70]). Leaders’ responsibilities, and their training and support to successfully engage in all aspects of their jobs, vary within countries, particularly related to the size of the ECEC settings in which they work (OECD, 2020[68]). Both within and across countries, leaders’ authority and locus of control to manage their administrative and pedagogical work have important implications for the scope of influence they have in working with staff and with children and families.

Findings from TALIS Starting Strong highlight the importance of the content of leaders’ initial education: in general, leaders whose education and training included a course on early childhood reported spending more time on pedagogical leadership (OECD, 2020[68]). This aspect of leadership includes observation of staff practices with children, providing effective feedback to staff based on these observations, establishing a collaborative culture among staff, as well as building positive relationships with families and community organisations. These practices are important for supporting process quality and for enabling staff to continue developing their skills and knowledge as part of their regular work duties.

Leadership can be exercised in more formal, hierarchical ways or in a more distributive, shared manner. Distributed leadership structures can help ECEC leaders fulfil their many job functions as well as motivate and retain staff by giving them a sense of ownership over their work. Data from TALIS Starting Strong suggest that staff who perceive more opportunities for participating in centre decisions tend to engage more frequently in professional collaborative practices and to report higher levels of job satisfaction. However, from the perspective of staff, distributed leadership structures are not always well established in different countries and could be further developed. Policy makers can support distributed leadership in ECEC by encouraging the development of specific middle leadership positions with differentiated pedagogical or administrative roles, which, combined with related preparation and training, can establish an effective leadership pipeline (OECD, 2020[68]).

Countries and jurisdictions have taken very different approaches to the continuity of ECEC during the COVID-19 pandemic. These approaches range from closing the ECEC sector completely, to restricting in-person programming to children of essential workers, to requiring ECEC staff to provide pedagogical continuity through distance learning (OECD, 2020[68]). The policy responses for pre-primary education are less consistent than those for primary education: whereas a majority of primary school teachers in 34 countries were required to continue teaching (remotely/online) during school closures, only 42% of these countries required pre-primary staff to continue teaching (OECD, 2021[1]). Similarly, remote learning tools to support teachers during this pandemic, including online, TV, radio and paper-based take-home materials, are less available at the level of pre-primary education compared to primary and higher levels of education, according to data from 118 countries (Alban Conto et al., 2020[71]).

Policy responses also vary in terms of whether they support ECEC settings and staff or whether they are directed to families (NCEE, 2020[72]). Regardless of the specific measures, COVID-19 is placing steep demands on the ECEC workforce, with yet unknown implications for the lasting impacts on this sector. Particularly in countries that rely heavily on private providers of ECEC, many ECEC settings are at risk of permanent closure due to forced closures in the short term and fears among families about the safety of continuing to access these settings during the health crisis (Friendly et al., 2020[73]; National Day Nurseries Association and Education Policy Institute, 2020[74]; OECD, 2020[68]; Zhang, Sauval and Jenkins, 2021[75]).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, ECEC leaders already reported a shortage of staff, which aligns with a shortage of ECEC settings to meet the demand from families in many places. In turn, ECEC staff reported that extra duties due to absent colleagues or having too many children in their classroom/playroom are top sources of stress in their work. Along these same lines, staff indicated that reducing group sizes by recruiting more staff was a top priority if the budget for the ECEC setting was to be increased (OECD, 2019[31]) (OECD, 2020[29]). With these existing pressures on the ECEC sector, any loss of staff related to the economic or health consequences of the pandemic could be deleterious for the availability and quality of ECEC in the coming years.

ECEC staff are meeting the challenges of working in new ways, adapting to changing requirements around health precautions when working in person and finding innovative ways to connect with young children and their families when working remotely (Franchino, 2020[76]; Pramling Samuelsson, Wagner and Eriksen Ødegaard, 2020[77]). However, the myriad challenges of shifting work with young children to the COVID-19 context takes a toll on the well-being of the ECEC workforce, including among staff who are working remotely and navigating the limits of technology for this field (Friendly et al., 2020[73]; Nagasawa and Tarrant, 2020[78]; Pramling Samuelsson, Wagner and Eriksen Ødegaard, 2020[77]). The ECEC workforce can address these challenges through identifying and implementing best practices given the evolving contexts of their work, participating in professional development and training opportunities, and developing communities of practice to support one another both within and across ECEC settings. Countries and jurisdictions can support ECEC staff to engage in these professional activities by ensuring that relevant materials and opportunities are available and that infrastructure is in place for such activities (e.g. adequate Internet access). More investment in the sector might be needed in countries where ECEC staff’s working conditions were already low before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Innovations in curriculum frameworks can help address the ongoing demands of the COVID-19 crisis, as well as prepare ECEC systems to flexibly adapt to new demands of the post-pandemic world and potential future shocks to the system. Related to ECEC closures in Hong Kong (China) in 2003 due to the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic, the government responded quickly to release a special curriculum for children ages 3 to 6 years (Rao, 2006[79]). This curriculum included lessons on various aspects of SARS and personal hygiene, supporting ECEC staff to share information with children related to the changing circumstances and routines in their centres (e.g. increased hand-washing, more limited opportunities for children’s social interactions). Although more supports or guidance for simultaneously adhering to health protocols and facilitating children’s social interactions may have proven useful in the context of this epidemic, the availability of curriculum documents tailored to this epidemic was an important strategy to help staff.

The role of digital technologies in ECEC is an emerging area for both research and policy. Whether or not curriculum frameworks explicitly address strategies to foster interactions between staff and children using digital technologies, staff need dedicated training on best practices around engaging with technology. Such training can help staff further their own professional learning and identify best practices around the use of technologies to support children and families, even in the context of in-person ECEC.

Countries and jurisdictions acknowledge the importance of engaging families as a tool for enhancing quality in ECEC and supporting children; however, only about one-half of the curricula included in responses to the Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire included families in their development process (Chapter 2). Given the importance of the home-learning environment, ECEC curriculum frameworks must strive to build links between these two settings where young children spend most of their time, identifying ways to support families as a key mechanism to support children’s learning, development and well-being. During the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong (China), centre leaders reported better communication with families as they worked to provide ongoing learning opportunities and then adapt to new ways of working in person when centres re-opened (Rao, 2006[79]). As ECEC staff around the world are now also expanding their approach to working with families, taking lessons from these experiences in order to continue strong partnerships following the pandemic is important (Box 1.3).

Researchers in Norway, Sweden and the United States conducted interviews in early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, offering a snapshot into the day-to-day strategies, opportunities and concerns across the three countries (Pramling Samuelsson, Wagner and Eriksen Ødegaard, 2020[77]). Differences in the experiences of staff, children and parents in these countries are interpreted with respect to the social and political contexts. In Norway and Sweden, ECEC is considered a right for children and parents, while in the United States, ECEC closures and re-openings were viewed primarily from an economic (i.e. parental labour force participation) perspective. The Nordic perspective meant ECEC settings were expected to remain open to the greatest extent possible, with ministry directives emphasising the importance of children’s attendance, unless ill. For staff, this became a matter of professional ethics, balancing their obligation and commitment to society with the stress from associated health risks of continuing in-person instruction.

Despite these different contexts, ECEC staff reported similar experiences across the three countries. Staff quickly adopted strategies to engage with children remotely, for example, creating private YouTube channels with personalised videos or daily online lesson plans consistent with children’s usual routines, including music and storytime. Yet, staff consistently reported that they felt ill-prepared for the technological demands and found remote teaching draining. Additionally, as these virtual interactions relied heavily on parents having enough time to assist with the implementation, consistent attendance was complicated, particularly for children of working parents.

In ECEC settings that remained open in Norway and Sweden, staff also experienced high-stress levels when continuing their work in person, due to the health risks. However, new health protocols also meant smaller group sizes were required. Staff noted that they could interact more frequently with each child and follow up with their interests in tailored lessons, a change they hope to continue post-pandemic. A strategy for staff to mitigate stress involved regular staff meetings, which were an opportunity for reflection, to talk openly about their experiences and feelings, participate in further in-service trainings, discuss strategies to meet children’s needs and support one another. These types of peer support and learning opportunities can be facilitated outside the context of the pandemic to promote staff well-being. Similarly, stronger communication with parents was noted in all three countries, which is another practice that can be supported following the pandemic to enhance ECEC quality.

Source: Pramling Samuelsson, I., J. Wagner and E. Eriksen Ødegaard (2020[77]), “The coronavirus pandemic and lessons learned in preschools in Norway, Sweden and the United States: OMEP Policy Forum”, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00267-3.

There is more variability in approaches to ECEC governance, oversight and funding than at most other levels of education. The 26 countries and 41 jurisdictions that participated in the Quality beyond Regulations policy questionnaire reported on 56 different curriculum frameworks. They provided information on staff training requirements and working conditions across more than 120 different types of ECEC settings. This vast array of dimensions of ECEC represent networks that address different developmental stages of young children and various needs of families, adapted to local policy contexts. Yet, there are many parallels and areas of similarity across systems. Nonetheless, the complexity of ECEC systems creates challenges, from families attempting to navigate these systems on behalf of their children, to policy makers trying to develop and implement effective policies to support equitable access to high-quality ECEC for all children.

Making international comparisons on policies beyond regulations, those to support process quality, requires situating these policies in the context of the ECEC systems in which they operate. This publication highlights examples of country and jurisdiction efforts to enhance process quality through curriculum and pedagogy (Chapter 2) and through workforce development (Chapter 3). In addition, a multidimensional map of policy levers for quality in ECEC is available on line, making available the breadth and depth of policy information that underpins the findings described in this publication. This multidimensional map uses the project’s conceptual framework (Figure 1.4) to organise data around the five policy levers: governance, standards and funding; curriculum and pedagogy; workforce development; data and monitoring; and family and community engagement.

Although not an explicit focus of this publication, data and monitoring strategies are tightly linked with the policy levers of curriculum and pedagogy and workforce development. Monitoring systems often focus on compliance with regulations, as opposed to focusing on interactions in ECEC settings and emphasising quality improvement. Countries and jurisdictions need to examine the extent to which their monitoring systems are able to collect and track information on process quality in order to inform policies for ongoing quality improvement.

The benefits of international comparisons of policies to support process quality are strong, despite the challenges of understanding the complexities and specific contexts of ECEC systems. As governments work to expand access to ECEC and simultaneously ensure high quality across all settings, the pace of changes means there are many opportunities to use examples from other countries/jurisdictions and adapt them for use in a particular policy context. The information and examples provided in this publication and the accompanying website offer policy makers opportunities to examine the place and priority of ECEC in their local contexts, to re-examine definitions of quality and move towards comprehensive approaches for building quality in ECEC settings through policy.

References

[42] Adema, W., C. Clarke and O. Thévenon (2016), “Who uses childcare? Background brief on inequalities in the use of formal early childhood education and care (ECEC) among very young children”, Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/els/family/Who_uses_childcare-Backgrounder_inequalities_formal_ECEC.pdf.

[71] Alban Conto, C. et al. (2020), “COVID-19: Effects of school closures on foundational skills and promising practices for monitoring and mitigating learning loss”, Innocenti Working Paper, No. 2020-13, UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti, Florence.

[4] Bauchmüller, R., M. Gørtz and A. Rasmussen (2014), “Long-run benefits from universal high-quality preschooling”, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol. 29/4, pp. 457-470, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.05.009.

[7] Belfield, C. et al. (2006), “The High/Scope Perry Preschool Program”, Journal of Human Resources, Vol. XLI/1, https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.XLI.1.162.

[39] Berger, L., L. Panico and A. Solaz (2020), “The impact of center-based childcare attendance on early child development: Evidence from the French Elfe Cohort”, No. 254, INED, https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/30325/working_paper_2020_254_childcare_collective.childcare.fr.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2021).

[47] Blanden, J. et al. (2016), “Universal pre‐school education: The case of public funding with private provision”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 126/592, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12374.

[19] Bowne, J. et al. (2017), “A meta-analysis of class sizes and ratios in early childhood education programs: Are thresholds of quality associated with greater impacts on cognitive, achievement, and socioemotional outcomes?”, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, Vol. 39/3, https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373716689489.

[30] Brussino, O. (2020), “Mapping policy approaches and practices for the inclusion of students with special education needs”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 227, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/600fbad5-en.

[24] Burchinal, M. (2018), “Measuring early care and education quality”, Child Development Perspectives, Vol. 12/1, pp. 3-9, https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12260.

[49] Burchinal, M. et al. (2015), “Early child care and education”, in Lerner, R., M. Bornstein and T. Leventhal (eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science: Ecological Settings and Processes in Developmental Systems, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

[27] Cadima, J. et al. (2020), “Literature review on early childhood education and care for children under the age of 3”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 243, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a9cef727-en.

[8] Campbell, F. et al. (2012), “Adult outcomes as a function of an early childhood educational program: An Abecedarian Project follow-up.”, Developmental Psychology, Vol. 48/4, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026644.