4. Governance architecture and policy tools for Fiji’s sustainable ocean economy

The interconnected nature of marine resources and the economic sectors they support means that more holistic approaches are needed to ensure policy coherence, identify and manage trade-offs between the sectors, and take advantage of synergies where policies can deliver benefits to multiple sectors. This chapter examines ocean policy governance in Fiji, including efforts to develop a National Ocean Policy for a more strategic, co-ordinated and integrated approach. It looks specifically at policy instruments in marine protection, sustainable fisheries management, maritime transport, living and non-living marine resources, and tourism.

The ocean is a central resource in Fijian society and cultural affairs, and well represented in many of the ministerial mandates (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]). Nearly all of the ministries of Fiji hold some form of mandate relevant to the ocean. The primary ocean management areas include fisheries, waste management, tourism, shipping, environmental protection, maritime/marine pollution, non-living marine resources, coastal infrastructure and cultural resources (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]). Many of these issues are managed by a number of stakeholders, as shown in the matrix below (Figure 4.1).

The fragmentation of ocean responsibilities, globally, has led to ineffective management and an accumulation of pressures upon natural resources that underpin much of the core ocean economic interests, including tourism and fisheries. Integrated ocean management is the most effective approach to account for the many ocean stakeholders and resource interests whilst accounting for external pressures such as climate change (Underdal, 1980[2]). The management approach is a core tenet of the headline commitment to sustainably manage 100% of the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) made by the members of the Ocean Panel, including Fiji (Ocean Panel, 2020[3]; Ocean Panel, 2021[4]).

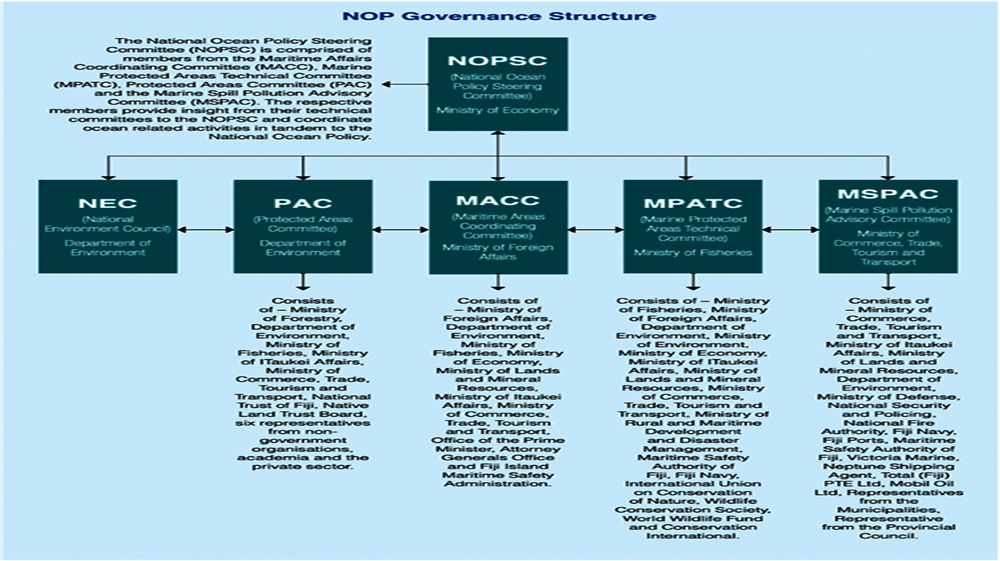

In 2020, the Ministry of Economy established the National Ocean Policy Steering Committee (NOPSC) to support a more strategic, co-ordinated and ultimately integrated approach to ocean governance. The committee seeks to steer the political and economic ocean agenda in a participatory manner (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]). However, this group does not replace the ocean-related ministerial mandates or technical committees. Instead, it aims to create coherence between ministerial priorities towards sustainable ocean management.

The National Ocean Policy (NOP) and the NOPSC at large provides a structure to organise the previous policy mandates and technical committees under a single co-ordinating body (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]). Within the NOPSC, the various ministerial actors retain their leaderships of, and positions within, committees established by previous legislative mandates. This approach to governance provides the potential to focus these groups and mandates towards national targets that account for the ocean more holistically, agreed by a super majority of the NOPSC members. The technical committees under the NOPSC are focused on thematic interests at the core of the mandates of their ministerial leads and participants.

The Protected Area Committee (PAC), headed by the Ministry of Environment, was formed under the Environment Management Act 2005 (Republic of Fiji, 2005[5]).The committee is composed of ministerial actors that hold mandates for sustainable environmental management and protection from the land to the ocean. It includes non-governmental NGO stakeholders and has a marine-specialist working group focussed on protected areas. This working group leads identification of potential marine protected areas (MPAs) through the application of marine spatial planning processes. The work of the PAC is channelled through the National Environment Council before the Cabinet ultimately makes decisions.

The Marine Protected Areas Technical Committee (MPATC), headed by the Ministry of Fisheries, is formalised by the Offshore Fisheries Management Decree 2012 (Republic of Fiji, 2012[6]). This committee brings together ministerial stakeholders required to achieve its mandate for the sustainable management of the marine area under national jurisdiction. This includes the identification and implementation of MPAs.

The Maritime Areas/Affairs Coordinating Committee (MACC) is led by the Ministry of Commerce, Trade, Transport and Tourism. It includes many of the ministerial stakeholders that operate offshore, as well as members of the Geoscience Division of the The Pacific Community. As one of its primary working areas, the MACC has focussed on formalising the country’s maritime boundaries. This includes negotiating treaties between neighbouring countries to resolve disputes and arrange for the submission of claims to extend the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) to the limit of the continental shelf. The MACC also reviews legislation that affects the management of marine resources, ranging from The Continental Shelf Act 1970 (Republic of Fiji, 1970[7]) through to the National Ocean Policy (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]).

The Marine Spill Pollution Advisory Committee is led by the Ministry of Commerce, Trade, Transport and Tourism. It includes ministerial stakeholders and a number of private industry representatives from the shipping and oil and gas sectors. It was established under the Maritime Transport Decree 2013, which domesticated Fiji’s obligations under the Conventions of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) (International Maritime Organization & International Conference on Training and Certification of Seafarers, 1993; International Maritime Organisation, 1992 and 1999). The committee primarily manages the National Oil Pollution Pool, a fund created by levies collected from actors that could potentially produce marine spills.

The National Environment Council (NEC), led by the Ministry of Environment, was established under the Environment Management Act 2005 (Republic of Fiji, 2005[5]). The NEC co-ordinates the formulation of policies and planning documents related to the environment, including but not limited to the ocean. In particular, the NEC ensures that environmental plans and policies include the perspectives of resource users, whether from private industry or the public.

Marine protection and sustainable management

The ocean can provide the energy, food, and cultural connections that humans require, but it requires effective protection and sustainable management. Fiji and the rest of the South Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICTs) have long been advocates for the sustainable management and protection of the ocean.

“Fijians have been at the forefront of ocean action and leadership because it is our responsibility as an oceanic people. Our very culture, our traditions, values and customs are intimately linked to the marine ecosystems that have sustained us since time immemorial. As a “large ocean state” it is our right and our privilege to be stewards of our exclusive economic zone of approximately 1.3 million square kilometers.” Hon. Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum (Republic of Fiji, 2021, p. 6[1])

Putting this cultural ethos in action, the country has recently taken two key policy actions that have reaffirmed Fiji’s position as a global leader in ocean affairs. First, as a member of the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, it made the headline commitment of sustainably managing 100% of its EEZ guided by an overarching policy document, the Sustainable Ocean Plan (SOP) (Ocean Panel, 2021[4]). Second, it produced a new NOP that outlines national priorities, such as 100% sustainable management and protecting 30% of the ocean by 2030 (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]).

The NOP covers many ocean policy positions, but it is rooted in one key goal: the co-ordinated 100% sustainable management of the ocean area under national jurisdiction (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]). The creation of the policy and the earlier establishment of the NOPSC institutionalised the Ocean Panel headline commitment. In addition, producing the NOP through an inclusive and participatory process led the Ocean Panel secretariat to recognise the policy as a suitable SOP (Ocean Panel, 2021[4]).

The NOP, the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2020-2025, and the preceding Green Growth Framework have outlined a staged and multistakeholder approach to protect 30% of Fiji’s EEZ by 2030 (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]; Department of Environment, Government of Fiji, 2020[8]; Ministry of Strategic Planning, National Development and Statistics, 2014[9]). The responsibility for implementing and managing MPAs lies primarily with the Ministries of Fisheries with support from the Ministry of Environment; Fiji Policy Force; Ministry of Defence and National Security; and the Ministry of iTaukei Affairs. Each stakeholder plays an essential role in marine protection through its existing policy mandates, which the NOP has aggregated into an integrated strategy.

MPA identification and implementation

The Ministry of Fisheries through the Offshore Fisheries Management Decree 2012 assumes responsibility for the designation of protected areas. The Permanent Secretary ultimately designates MPAs. However, the Director of Fisheries identifies and recommends specific areas within the country’s marine area under national jurisdiction (EEZ), from the coastline to the maritime boundary (Republic of Fiji, 2012[6]).

The Ministry of Fisheries co-ordinates with the PAC – established under the Environment Management Act 2005 – and leads the MPATC in identifying appropriate areas that can be protected to maximise the benefits of meeting this target. Both the PAC and the MPATC are organised under the NOPSC (Figure 4.2). In pursuit of protecting 30% of the EEZ, the Ministry of Fisheries/MPATC began by engaging the PAC to review marine areas that had previously been recognised as significant. This effort expands upon the prior inventory of marine sites of ecological, geological, biological, landscape, recreational and/or geomorphological significance that were identified as a part of the National Environment Strategy (Fiji and IUCN, 1992[10]). The MACBIO programme has accelerated identification of priority areas for protection. A MACBIO report (Sykes et al., 2018[11]), identified “Special, Unique Marine Areas” (SUMAs) that contribute significantly to marine biodiversity in the country. These SUMAs update and expand the inventory of important marine areas. However, they are not a list of areas that should or will necessarily be protected. Rather, they are a set of priority areas with a ranking between 5 and 12, with higher ranks indicating a greater priority for management.

Expanding the inventory of priority areas based on a set of criteria that recognises attributes that make them unique. This process is one small part of the exercise to identify areas that should be protected based on their role as biodiversity hotspots, climate regulation and nutrient cycling, among many other services. The country has undertaken a data-driven process to identify the ultimate MPA network that will make up 30% of the EEZ. It is pursuing this goal with the assistance of stakeholders, including the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). The SUMAs were identified as one of more than 100 data layers to identify priority areas for protection. The process is based on a wide range of criteria to ensure that marine areas of national significance are protected. At the same time, it seeks to maintain access to important sustainably managed resources, including the tuna fishery.

The identified network of areas, which is undergoing rounds of public consultation, would be a roadmap for the protection of 30% of the EEZ by 2030. The NOP outlines key milestones (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]) for the designation of 5% of the EEZ by 2023 and 10% by 2025. The plan would be implemented gradually, giving Fiji eight years to achieve its 30% target. It would become an example of best practice to guide other countries pursuing similar targets for marine protected areas.

MPA challenges: Monitoring and enforcement

The primary governance challenge inherent to this commitment is the surveillance and monitoring of the area-based management tools, and the enforcement of the MPA regulations. The EEZ of Fiji is about 1.29 million km2 – an approximate figure due to disputed boundaries and ongoing claims to extend the EEZ due to the continuity of the continental shelf in the north and south of the country. Protecting 30% of this total area equates to the management of 387 000 km2; or, an increase in MPA coverage of about 375 000 km2 over that which is currently protected under an internationally recognised designation. Such a scaling-up requires an evolution in the capacity and resources available to the National Environment Security Taskforce (NEST) and Ministry of Defence and National Security at large to conduct monitoring and enforcement as mandated by the NOP.

Other countries with large coastal areas and total EEZ have focused on leveraging the tourism assets of the protected seascapes to generate the revenue necessary for monitoring and enforcement – whether for vessel procurement and maintenance, or legal representation. In the Philippines, this model, in the form of the National Implemented Protected Area System (NIPAS) Act (Republic of the Philippines, 1992[12]), also known as Republic Act 7586, has proven to be successful. In this case study, large seascapes have been protected and, where possible, marketed as national tourism hotspots in collaboration with the national tourism agency and regional tourism associations. The revenue generated is centralised into the national Department of Environment and Natural Resources and disbursed to Protected Area Management Bureaus associated with each of the NIPAS areas. This provides a relatively stable source of finance for monitoring and enforcement for these areas. Otherwise, they would struggle to generate enough baseline funding for management.

The MPA management funding model could be replicated to some extent in Fiji to leverage the value of tourism assets in the more accessible of the proposed areas. Such leveraged assets could generate revenue to help the Ministries of Economy and Defence and the NEST acquire and maintain the necessary technology and resources. The primary challenge of this approach in Fiji is the offshore MPA strategy, with the distance from shore and the depth of ecosystems being prohibitive to tourism access. Coastal biodiversity and protected areas may provide an opportunity to generate revenue in collaboration with local communities that are integrated into coastal zone management. However, generating revenue at the scale necessary from coastal assets, and in an equitable manner, remains a challenge.

The NOP outlines an updated approach to raise capacity to ensure the protected areas are well managed and that the entire EEZ is sustainably managed:

Increase national maritime domain awareness among national agencies (such as the Ministry of Fisheries, Maritime Safety Authority of Fiji, Water Police and Fiji Navy), private sector (such as tourism operators and shipping lines) and local communities, as well as relevant regional and international partners and governments to further embed multidimensional security into the 100% sustainable management of areas within national jurisdiction.

Enhance inter-agency information management and work delivery across multidimensional security issues.

Expand co-ordination among agencies to safeguard the ocean from land-based threats through establishment of a protocol and communication procedure through a national focal point.

Increase enforcement through surveillance of the ocean, including designated area-based management tools and fishing hotspots, and ensure compliance of all marine activities.

Strengthen regulations and mandated legislative powers where necessary, including for emergencies and use all available means to legally pursue all infringements.

The capacity enhancement process prioritises distributed awareness of the regulations, strengthened cross-ministry information management and sharing, and enhanced technology and capacity for surveillance, and adopts a more litigious and resourced stance towards rule breakers. The key challenges in this set of objectives, for the area represented by 30% of the EEZ, is surveillance and compliance. All the objectives require investment, whether in communications technology or in-house legal representation. However, given the scale of the area, surveillance and compliance will require innovative applications of technology and vessel co-ordination. To date, the Ministry of Defence is already using a number of remote sensing technologies. This includes Vessel Monitoring Systems coupled with use of technology such as Geofencing and Global Fishing Watch as a means to co-ordinate response. A deeper evaluation is needed to create cost-effective processes for co-ordinating vessels responses through a larger space based on vessel tracking and behavioural alerts.

Informal marine protection

The NOP recommits to the goal of protecting 30% of the EEZ by 2030, and progress has been made towards that end through the efforts of the Ministry of Fisheries, the MPATC and external partners. However, the country also has a large area of informally protected marine areas throughout the coastal zone. These could be leveraged for more equitable and inclusive benefits in achieving the national target of marine protection. The coastal zone in Fiji is managed by several different stakeholders:

The Ministry of Environment, through the Environment Management Act 2005 (Republic of Fiji, 2005[5]), is responsible for reducing environmental pollutions and pursuing legislative action to compensate those affected by environmental degradation caused by pollution.

The Ministry of Fisheries, through the Offshore Fisheries Management Decree 2012 (Republic of Fiji, 2012[6]), is responsible for the development and sustainable management of the fishery, including the regulation of commercial fishing enterprise through a licensing programme.

The Ministry of iTaukei Affairs advocates for the traditional and cultural rights of Indigenous Peoples of Fiji, the iTaukei. It pursues these objectives through the iTaukei Lands and Fisheries Commission (TLFC), a composite statutory body formed under the iTaukei Land Act 1905 (Republic of Fiji, 1905[13]), and The Fisheries Act 1941 (Republic of Fiji, 1941[14]). It advocates for maintaining the many natural access rights, including the right to access and subsist off coastal resources through non-commercial enterprises.

The Ministry of Local Government and the Local Councils are responsible for managing waste and providing the necessary services for the removal and processing of waste to prevent environment degradation through pollution.

The primary synergies are between the Ministry of Environment and Local Government Councils. These groups work together to ensure that infrastructure is sufficient to prevent land-based sources of pollution driving coastal degradation. While potentially contrary management responsibilities exist between the Ministry of Fisheries, which has a mandate to regulates the extraction of living coastal and marine resources and the Ministry of iTaukei Affairs, which maintains an unrestricted – though limited to coastal areas adjacent to communities – traditional access right to the fishery for the iTaukei people.

The iTaukei people have held a customary marine tenure, which includes coastal living resources, for millennia. This right is a shared community resource, wherein fisherfolk harvest marine resources for the subsistence of their families or for community functions where required. The goods are not sold throughout the community instead, being shared as a community resource. Each village maintains a social and cultural association with nature, including the marine and coastal areas adjacent to their community. This area is managed by groups of related communities, and the Ministry of iTaukei Affairs represents these rights in the formation of policy and planning documents at the national level (Republic of Fiji, 1941[14]).

This distribution of responsibility creates a challenge in protecting marine areas to a degree recognised by international standards such as the typology created by the IUCN (IUCN, 2013[15]) – namely the aim to establish areas from which no resources can be extracted. It is not possible to create a “fully protected area” or a permanent “no-take zone” and maintain the cultural access right to resources for subsistence, unless it is the community that closes the area. However, it is possible to create effective area-based management tools that regulate when fishing occurs, the species targeted and the technology that can be applied. This can include temporary or permanently protected areas, should the community choose. These area-based management tools, applied at a very local level, usually by engaging local leaders as the project proponent/ resource owner, are often referred to as Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMA) (Govan et al., 2008[16]).

Fiji has been an early adopter and successful case study of the LMMA. A review of the extent of the coastal zone covered by LMMAs found (Govan et al., 2009[17]) that LMMAs had been implemented over ~10 000 km2, covering 22% of the coastal zone. Of this figure, at the time, 600 km2 of the total were community designated ‘tabu’, or no-take areas. 1

Fiji’s network of LMMAs makes a small contribution towards protecting 30% of the EEZ. However, it is the most effective way to represent local community needs in marine management and potentially leverage these assets for the further enrichment of coastal communities. Yet, the LMMA is not eligible in accounting towards international targets, including Aichi Target 11, or the potential “30 by 30” target in the Post-2020 Biodiversity Framework Zero Draft for negotiation at the Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD) Conference of Parties in 2022.

LMMAs could potentially be counted as “Other Effective Conservation Measures” towards targets established under the CBD. However, the communities that are a part of the LMMA network would first need to be consulted and build consensus on whether there was a local desire for their efforts to contribute towards national and international targets. The contributions of LMMAs and other indigenous systems of management in national accounting can bring many benefits, including enhancing community resilience to environmental and social disasters.

Waste management

The pollution of the coastal zone and the movement of pollution from the coast into the open ocean is one of the most significant and long-standing threats to ecological health and the social well-being that relies upon it. Pollution comes in many forms and from many sources, which places it among the most difficult of the many ocean management challenges.

Fiji has developed many policies to manage pollution, in collaboration with regional partners that have held a primary target of managing pollution. These include partners such as the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) - with ongoing work through the PacWastePlus project (SPREP, 2020[18]). Waste in Fiji comes from many sources, with different land uses often associated with different waste management challenges. The growing urban population in Fiji, for example, generates a challenge across the waste management process, including industrial waste, solid and liquid and a small range of hazardous waste.

The NOP notes that challenges to effective waste management processes that can limit the quantity of waste moving into the coastal zone is one of five major threats to the ocean identified by stakeholders and assessments (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]). The policy recognises that better co-ordination and awareness of how waste enters and affects the ocean will be required to change the behaviours driving this problem. Of particular importance is the use of the legislative tools to enforce compliance through the Environment Management Act 2005 (Republic of Fiji, 2005[5]) and the Litter Act 2008 (Republic of Fiji, 2008[19]). The Clean Environment Policy, launched in 2019, will be a key tool to proactively raise awareness among the public about how behaviours relate to the pollution of the marine environment.

Marine pollution is a pervasive issue that spreads throughout the country’s EEZ and beyond, requiring integration and co-operation, even across borders, to resolve. The Environment Management Act 2005 (Republic of Fiji, 2005[5]) is the central policy document to address waste management and pollution control measures. Working through the Marine Spaces Act 1977 (Republic of Fiji, 1977[20]), it introduces measures that encompass the entire EEZ. Within waste management, the policy landscape includes a number of cross-ministerial action areas and policy measures:

The Fiji National Solid Waste Management Strategy 2011-2014 (Republic of Fiji, 2011[21]),

National Plan for the Implementation of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in Fiji Islands (2006),

Climate Change and Health Strategic Action Plan 2016-2020 (Republic of Fiji, 2016[22]): Recognising waste management as a strategy to reduce disease risk,

Environment and Climate Adaptation Levy Act (Republic of Fiji, 2015[23]): With specific regulations/levies around the use of plastic bags,

iTaukei Affairs Act (Republic of Fiji, 1944[24]): Allowing local councils to create bylaws for the management of waste,

National Liquid Trade Waste Policy (Republic of Fiji, 2017[25]).

The country has made significant progress recently to enhance the policy foundation for actions to reduce plastic waste pollution, including the following:

the plastic bag levy and 2020 ban legislated through the Environment Management Act 2005 (Republic of Fiji, 2005[5]),

the styrofoam/polystyrene ban, covering the use, import and manufacture of expanded polystyrene.

Plastic levies and bans are critical steps in managing solid waste. However, the challenge of waste management is significantly larger than that of plastic waste. Using plastic as an international rallying point will help resolve challenges in solid waste management at large. However, liquid and hazardous waste produce many of the most significant waste-related impacts upon marine ecosystems. These affect water quality habitat viability is affected itself (IRP, 2021[26]). While the policy landscape is robust and covers many waste sources, major challenges lie in developing the distribution and density of waste management infrastructure. This includes incentivised recycling centres and water treatment plants (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]); (SPREP, 2020[18]).

The management of waste and its impact upon the coastal zone and beyond can be managed through mitigation and prevention. Towards those ends, Fiji is relatively advanced through its adoption and institutionalisation of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) approaches. ICZM is a systems-based management practice that covers a range of approaches that vary globally with the ecological and social contexts. ICZM aims to identify the many stakeholders connected to the coastal zone, and the connectivity between land and ocean biomes. In this way, it helps harmonise sustainable and prosperous practices across the land-sea interface (Thia-Eng, 1993[27]). Fiji established its ICZM Framework in 2011 and has used much of the framework’s language and aims to develop the NOP’s integrated ocean management principles (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]). The WCS has spearheaded some of the major ICMZ-based successes in the country. It has worked extensively on watershed management, ridge to reef approaches, and on ICZM plans to enhance environmental management, including the mitigation of pollution (Makino et al., 2013[28]).

Sustainable fisheries management

Fisheries are a core resource derived from the ocean and tidal areas around the world. The content for fisheries herein encompasses both catch fisheries by vessels in the coastal and open ocean, and aquaculture and mariculture practices that occur in or adjacent to the tidal area and coastal zone.

The Ministry of Fisheries, established in 2018 as an independent ministerial entity, holds a mandate for the sustainable management and protection of the marine and coastal resources. Its strategic objectives include sustainable harvest fisheries from the coastal and offshore zones; aquaculture development; and research and innovation. The ministry administers the Offshore Fisheries Management Decree 2012. It also develops new policies and development plans for the industry (Republic of Fiji, 2012[6]), including the forthcoming National Fisheries Policy (Republic of Fiji, 2020[29]).

Offshore fisheries

Fiji, the South Pacific High Seas Pocket, and many of the Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICTs) are home to the world’s largest tuna fishery. Management of offshore fisheries, primarily focused on tuna, is governed directly by the Offshore Fisheries Management Decree 2012 (Republic of Fiji, 2012[6]).

Fiji has the most developed fisheries capacity in the region, allowing it to access and utilise the fisheries resources to a higher degree than many of the other PICTs. In 2020, Fiji maintained 86 longline vessels as part of its national fleet. However, the ministry caps licences for the right to fish within the EEZ to 60 vessels. Of the remaining, 20 vessels fish exclusively in the high seas (High Seas Pocket and international waters), with 6 licensed to fish in Fiji’s archipelagic and territorial seas (Hare et al., 2021[30]) Those fishing within the High Seas Pocket are regulated under the Regional Fisheries Management Organisation: the Western Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, with co-operation from the Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) (WCPFC, 2000[31]).

The greatest challenge of the ministry in offshore fisheries management is monitoring and surveillance of illegal, unregulated, and unreported fisheries (IUU) to ensure IUU practices are not degrading the health of the fish stock. To this end, it has put in place several measures and partnerships, including greater representation of observers on vessels; and a collaboration with the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), the FFA and the Fiji Fishing Industry Association that has led to re-establishment of Fiji’s Marine Stewardship Certification in 2018 (Akroyd and McLoughlin, 2017[32]).

Inshore fisheries

The Offshore Fisheries Management Decree 2012 includes provisions for the management of the inshore fishery through a licensing programme. However, there is a distinction between fisheries activities and their practitioners, and the licensing requirements (Republic of Fiji, 2012[6]). The ministry registers each fisher that extracts marine living resources with the intent to sell them (Republic of Fiji, 2012[6]). There is a distinction between those that sell resources, and those that use them for subsistence and cultural purposes. This distinction divides line between the licensing responsibility of the ministry and the rights of the iTaukei people to utilise marine and coastal resources (Republic of Fiji, 1941[14]).

The regulatory line between subsistence and commercial purposes is occasionally crossed, and a licensing process is proactively pursued to ensure that penalties against indigenous communities are avoided, as was observed during the COVID19 pandemic. During the pandemic, many citizens returned to the coastal zone, relying upon coastal resources to ensure food and economic security. This led to the sale of living resources collected from coastal areas by those with access rights. Observers reported this practice to the Ministry of Fisheries triggered a licensing process and reform – characterised by the lifting of the licence fee for a period of three years for small-scale operators.

Aquaculture (including mariculture)

Aquaculture is in its nascence in Fiji; however, the industry has been recognised as a potential source of food security and a significant opportunity for sectoral growth in Fiji’s 5-year and 20-year National Development Plan (Ministry of Economy, 2017[33]). While the sector is a target for growth, the Ministry of Economy has recognised the industry has observed slow growth to date (Ministry of Economy, 2017[33]). The forthcoming National Fisheries Policy is expected to provide the necessary guidance to support investment and expansion.

The country holds two major emerging policy tools to develop the sector: the 2016 Aquaculture Bill (Republic of Fiji, 2016[34]), and the forthcoming National Fisheries Policy (Republic of Fiji, 2020[29]). The draft National Fisheries Policy draws much of the aquaculture bill under its remit. It will act as the primary policy instrument to guide development of the sector in alignment with the National Development Plan (Ministry of Economy, 2017[33]) and the Strategic Development Plan 2019-2029 (Ministry of Fisheries, 2019[35]).The goal for aquaculture is to use the industry as a means for economic growth and a stable source of nutrition. Targets will be primarily focused in the tidal zone for brackish water production (Ministry of Fisheries, 2019[35]).

Coastal efforts are focused on fish aggregation and the identification of successful, scalable enterprises, while work is ongoing in the tidal zone to build capacity for the larger scale production of tilapia and shrimp (Ministry of Fisheries, 2019[35]). Development of coastal products may include increasing pearl production, identifying opportunities for seaweed production, and sea cucumber harvesting and processing (bêche-de-mer). However, unsustainable extraction of high-value sea cucumber species (H. scabra, sandfish) led to a species-specific export ban in 1988 (Pakoa et al., 2013[36]), a broader prohibition of compressors or SCUBA gear in harvesting in 2016 and a total commodity export ban in 2017.

The Strategic Plan 2019-2029 and the 5-year & 20-year National Development Plan highlight a rapid growth strategy for the industry (Ministry of Fisheries, 2019[35]; Ministry of Economy, 2017[33]). Growth, as highlighted in the 5-year & 20-year National Development Plan, will be catalysed by providing support in:

promoting for private sector investment (through public-private partnership, tax incentives and research and development),

incentivising commercial-scale developments for commodities, including prawn/shrimp, tilapia and seaweed,

providing support to grow small-scale aquaculture enterprises to enhance the role of the industry as a source of food and economic security,

improving access to training, advice, quality seed and feed, and financial support,

upgrading support facilities that provide brood and feed stocks and evaluating the fee structure for these resources,

evaluating the aquaculture value chain of specific species to identify value-adding techniques and processes and to create marketing strategies, including further exploring the potential to develop capacity in niche markets such as sea cucumber, sea grapes and marine fish culture.

The development trajectory targets both commercial-scale growth and small-scale producers as a source of sectoral growth and food/economic security, respectively. The commodities targeted as the drivers for industry development, shrimp/prawn and tilapia, utilise either ponds and/or tanks (Ministry of Fisheries, 2019[35]). Both the pond and tank approaches require a cross-ministry approach for management due to the distribution of responsibilities for coastal land-use change and waste management. Pond aquaculture is typically concentrated in low-lying tidal plains with regular tidal inundation and hydrological inputs from the land, creating a brackish environment (Boyd and Tucker, 2012[37]). These tidal areas are often occupied by salt marsh and mangrove ecosystems (Spalding, 2010[38]), which are frequently converted into ponds for aquaculture. Mangrove and marsh conversion into aquaculture ponds has been the primary driver of the decline of mangroves in the Asia-Pacific region for the past 70 years (Goldberg et al., 2020[39]).

In Fiji, mangroves are managed by three ministries: Lands and Mineral Resources, Forests, and Environment. Fiji’s tidal area and foreshore are classified as state land and fall into the management jurisdiction of the Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources. Mangroves, occupying the tidal area and foreshore, therefore fall into the remit of the Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources (Republic of Fiji, 1945[40]); however, the Ministry of Forests can still designate appropriate mangrove areas as forest reserves and license commercial extractive activities (Republic of Fiji, 1992[41]). The Ministry of Forests licensing process protects mangrove ecosystems by requiring licences for activities that degrade the forest, including the felling of trees. However, these regulations do not extend to subsistence use of forest goods (Republic of Fiji, 1992[41]). The Ministry of Environment, through the Environment Management Act 2005, requires that developers of areas occupied by mangrove forests conduct an environmental impact assessment (EIA) prior to converting land or commencing construction. They must then present results to nearby communities for consultation (Republic of Fiji, 2005[5]).

A Mangrove Management Plan, was drafted in 1985 as an ecosystem evaluation and management framework, but never institutionalised as law in Fiji (Watling, 1985[42]). An update was drafted in 2013 but was not institutionalised either. The draft Mangrove Management Plan 2013 aims to ensure that mangroves are managed through a robust EIA process. This should allow for development and mangrove conversion but only after an accepted and consultative EIA and mitigation process (Watling, 2013[43]). As such, to create fishponds and grow the pond-based industry at large, the Ministry of Fisheries would be required to support small-scale practitioners navigate this process to obtain conversion licences for pond aquaculture where necessary. However, in 2012, the Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources called for a hold on developments that would affect mangroves until after consultations on the Mangrove Management Plan 2013.

The forthcoming National Fisheries Policy aims to centralise some of the aquaculture establishment process, specifically regarding licensing (Republic of Fiji, 2020[29]). It is unclear whether the Ministry of Fisheries will create a Fishpond Lease Agreement mechanism, prevalent in many Southeast Asian (SEA) countries with large and distributed aquaculture industries (Adan, 2000[44]). The policy aims to:

“Ensure legislation provides an effective permit and licensing system for the administration and control of the aquaculture industry, and that provides secure tenure” (Republic of Fiji, 2020, p. 14[29]).

The tenure element suggests a process to centralise some of the land zoning and management responsibility for coastal areas which is held within the Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Lands. Without centralising, a stakeholder would be required to apply for a land conversion licence with the Ministry of Lands. This, in turn, would be contingent upon an approved EIA with the Ministry of Environment to obtain a licence and/or tenure for aquaculture from the Ministry of Fisheries. These regulatory barriers would stifle the growth of the industry, especially at the small-medium enterprise level. Consequently, efforts to generate policy coherence while retaining environmental standards for aquaculture has been identified as a key policy mechanism for industry growth (Beveridge et al., 2010[45]).

An additional governance barrier to pond aquaculture growth is the right of the Traditional Fishing Rights Owner (TRFO), established under Cabinet Paper 74(204) – registered by the iTaukei Fisheries Commission in the Register of iTaukei Customary Fishing Rights (Republic of Fiji, 1941[14]). The TRFO instituted the right for traditional rights owners to receive compensation for the loss of fishing rights that could occur through the degradation of natural resources which underpin the health of local fisheries. Mangroves contribute significantly to the health of nearby fisheries (O’Garra, 2012[46]). As such, each conversion would result in some form of damages to nearby rights holders. These would need to be factored into the mitigation strategies of the EIA and licence arrangements for aquaculture ponds.

Tank-based aquaculture requires co-ordination with the Ministry of Local Government and the Local Councils where the enterprise is established. This is primarily for the management of liquid waste that builds up in tanks due to unused feed and excrement. This waste, with high concentrations of nutrients, can be an environmental toxin (Dauda et al., 2019[47]). Water treatment facilities and waste transport must be co-ordinated with the local councils, which hold a jurisdiction-based responsibility to manage liquid and solid waste.

Waste management is a core demand in aquaculture and mariculture and has been a global challenge for the industry as investment has fuelled its growth (Dauda et al., 2019[47]). The concentration of living resources in relatively small spaces generates a variety of waste pollutants. Of particular significance to the nearby environment is the localised eutrophication potential that a high density of live organisms can generate through leftover feed and excrement. In addition, other waste, including medications, antifoulants and disinfectants can enter the environment and affect local ecosystems. Their impacts depend upon the concentration and volume of chemicals and the volume of the polluted waterbody (Dauda et al., 2019[47]).

Maritime transport

The Pacific is the largest ocean on Earth, with the EEZs of the PICTs alone representing a significant proportion of the world’s ocean area under national jurisdiction. The “small” island states of the South Pacific are ocean states with immense ocean jurisdictions. The ocean connects each of the countries and the islands within. Moreover, the entire region relies heavily on maritime transport in the same way that many continents and countries rely on land transport for national and cross-border trade.

In the region, Fiji acts as a major transport hub with a relatively developed port infrastructure for short- and long-distance shipping of goods. Additionally, maritime transport is a critical transport and trade link between Fijian islands, particularly where the end destination does not yet have airport infrastructure.

The maritime transport sector is governed by the Ministry of Transport, situated within the Ministry of Commerce, Trade, Tourism and Transport. The Ministry of Transport administers the Maritime Transport Act 2013 (Republic of Fiji, 2013[48]), and guides development in accordance with the Maritime Transport Policy 2015 (Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, 2015[49]). The primary goals of the policy are to:

Reduce the environmental impacts of the industry, particularly with regards to greenhouse gas emissions from vessels and infrastructure.

The primary environmental/sustainability outcomes of the policy are generated through the domestication of IMO policies, which include provisions to reduce marine and port sources of pollution; and the goal to reduce the climate impacts of the shipping industry, which highlights the importance of low carbon fuel substitutes and improving energy efficiency and the potential for a shift toward renewable energy sources in alignment with the Green Growth Framework (Ministry of Strategic Planning, National Development and Statistics, 2014[9]) and the National Energy Policy (Republic of Fiji, 2013[50]).

Growth in the sector will require two major streams of work: developing port infrastructure further for international and regional trade; and enhancing inter-island connectivity to link more of the nation’s distributed communities to trade opportunities. Both of these efforts require cross-ministerial and public-private collaboration, as the ports are managed by a separate entity. Fiji Ports, first established under the Ports Authority of Fiji Act 1985 (Republic of Fiji, 1985[51]), was later incorporated as Fiji Port Corporation Limited under the Seaports Management Act 2005 (Republic of Fiji, 2005[52]). The Government of Fiji and the National Provident Fund, holds the majority stake in the corporation but it is a private enterprise. The entity owns and operates Fiji’s four major ports and identifies development opportunities separate from, though in alignment with, the Ministry of Commerce, Trade, Tourism and Transport. As such, reducing the carbon footprint of the sector will require collaboration with, and incentivisation of, the private port stakeholder and the private entities that operate within its remit.

The key lever towards sustainable and transformative growth in the sector is the commitment to reduce its carbon footprint by incentivising and encouraging the uptake of low-carbon technologies. The policy does not commit to a zero-carbon target, gross or net, or the complete decarbonisation of the industry. Instead, its language suggests an aim to reduce the carbon intensity of the sector at large, and invest in, identify, and develop low-carbon technologies. The policy does not offer an indicator at which emissions reduction would be achieved. However, it does commit the country to developing capacity and technology to monitor emissions. It also loosely commits the government to evaluate and produce requirements to address fuel emissions from ships in alignment with MARPOL Convention Annex VI (International Maritime Organization, 1992; Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, Government of Fiji, 2015).

The key challenge in reducing the carbon footprint of the sector, while enhancing connectivity is the subsidies required to maintain services along non-profitable routes. The current fuel-focussed subsidy structure could be reformed and applied as a direct subsidy per passenger transport. This approach would retain an incentive for innovation, in the form of the input costs of fuel, though should only be pursued once there are available and competitive technologies in the region for low carbon or zero carbon transport. The carbon footprint could still be reduced along profitable routes where the government has committed to remove public competition to private services and support the development of private sector capacity. In addition, the Maritime Transport Policy recognised that price control should be a last resort (Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, 2015[49]). The National Ocean Policy (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]) does not build upon the stance towards price control or subsidies for the transport sector. It offers only a commitment to reduce harmful subsidies in the offshore fishing sector to reduce the artificially inflated capacity to fish.

The National Ocean Policy (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]) emphasises the country’s commitment to reduce emissions from the sector, and outlines specific indicators that align with the Maritime Transport Act 2013 (Republic of Fiji, 2013[48]). These indicators focus on mitigating the effects of pollutants with collaboration across the NOPSC. They also draw on contributions of the Ministry of Commerce, Trade, Tourism and Transport to enhancing security, including indirect actions that enhance protected area management and the broader goal of sustainable managing 100% of the EEZ (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]). Six key outputs of the National Ocean Policy Strategy are noted below:

Output 2.8: “Constantly review and update Fiji’s catalogue on dangerous synthetic chemical and pollutants for farming/industrial use and implement a phase-out of these pollutants” (Republic of Fiji, 2021, p. 53[1]).

Output 3.1: “Increase national maritime domain awareness among national agencies (such as the Ministry of Fisheries, Maritime Safety Authority of Fiji, Water Police and Fiji Navy), private sector (such as tourism operators and shipping lines) and local communities, as well as relevant regional and international partners and governments to further embed multidimensional security into 100% sustainable AWNJ management.” (Republic of Fiji, 2021, p. 54[1]).

Output 3.2: “Enhanced inter-agency information management and work delivery across multidimensional security issues” (Republic of Fiji, 2021, p. 55[1]).

Output 3.3: “Expand co-ordination among agencies to safeguard the ocean from land-based threats through establishment of a protocol and communication procedure through a national focal point” (Republic of Fiji, 2021, p. 56[1]).

Output 3.4: “Increase enforcement through surveillance of the ocean, including designated area based management tools and fishing hotspots, and ensure compliance of all marine activities” (Republic of Fiji, 2021, p. 57[1]).

Output 3.5: “Strengthen regulations and mandated legislative powers where necessary, including for emergencies and use all available means to legally pursue all infringements” (Republic of Fiji, 2021, p. 58[1]).

Mineral and non-living marine resources

Mineral resources on the seafloor have become among the more discussed and contentious topics of the decade. The most commonly discussed minerals centre around three primary interests:

manganese nodules that primarily exist within abyssal plains,

seafloor massive sulphides (SMS), which accrete near to hydrothermal vents,

cobalt crusts, which are found in seamounts (Herzig, 1999[53]).

These minerals are available on land, though the high social and environment costs of mining and the costs required for mineral imports have shifted a portion of national exploratory interests offshore (ISA, 2021[54]). Terrestrial mining has a broad footprint with the mine sites themselves representing extensive land conversion and the distribution infrastructure including road networks, port infrastructure adding to the land conversion pressure. However, many of the environmental and health risks of terrestrial mining come from the use and, often unintended, release of chemicals into the nearby environment, including those with head neurological degenerative effects such as mercury and lead, and others that are toxic including arsenic (Worlanyo and Jiangfeng, 2021[55]). From a social perspective the challenges are concentrated in the land rights and the equitable distribution of the benefits of mining a countries natural resources, with local labour often not being engaged and compensated to the same extent as foreign labour and child labour being prevalent in the mining industry in the developing world (Mancini and Sala, 2018[56]). The interest in mining these minerals is due to the key roles they play in renewable energy technologies primary in the production of batteries for the storage of power from renewable energy sources and for electric cars (Ecorys, 2012[57]); and as a source of base metals including gold, copper, and zinc, in the case of SMS (Van Dover, 2010[58]).

In the context of a SIDS, minerals that make up part of the supply chain of key technologies for the future represent a significant opportunity for economic growth. Yet, the terrestrial deposits of minerals such as cobalt are not evenly distributed around the world. Much of the activity is concentrated in reclaiming cobalt from tailings in Central African mines. Ocean deposits of cobalt represent an entry point for many countries into the market, removing the barriers of high costs for mineral imports (ISA, 2021[54]). However, the environmental cost of mining does not go away when extraction is shifted offshore (Stratmann and et al, 2018[59]), due to the concentration of minerals near key biodiversity hotspots and the impacts that disturbing the seabed can have on benthic habitats and vulnerable marine ecosystems. Nor does the practice resolve equitability issues or align with social values either, with key challenges identified in ensuring that revenue generation is equitably distributed and that the industry accounts for and builds local capacity and skills, and additional challenges in respecting traditional values held in the integrity of the seabed (Feichtner, 2019[60]); (Folkersen, Fleming and Hasan, 2019[61]).

The authority responsible for minerals at large is the Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources. Under the Mining Act 1965 (Republic of Fiji, 1965[62]), which was amended in 2010 to allow for the exploration of deep-sea minerals, the ministry can grant licences to industry stakeholders with capacity to explore the seabed. In Fiji, the primary mineral interest is in SMS. These mineral resources within Fiji’s EEZ are, under international law, available for extraction by the nation and its partners (UNGA, 1982[63]). Fiji has granted three exploration licences, although it has cancelled one of them.

The legality of deep-sea minerals within an EEZ lies with the country, but the president of Fiji imposed a ten-year moratorium on the extraction of mineral resources from the ocean for 2020-30. The moratorium will allow the licence holders to explore the EEZ for minerals. However, they cannot test any technologies on the collection of those minerals until the moratorium lapses or is overturned.

Once the moratorium period ends, the NOP outlines a requirement for economic sectors and opportunities to mitigate or reduce the effects of their activities on the ocean. This strategy comes with a strategic indicator that would mandate ministries to identify seabed mining exclusion areas, and a dedicated sustainability indicator:

“Ensure that all seabed mineral activities within and beyond national jurisdictions comply with robust environmental standards.” (Republic of Fiji, 2021, p. 61[1])

As there are no national definitions of environmental standards for deep-sea mineral extraction, or science-based consensus feeding into internationally accepted standards, the future of deep-sea mining is unclear. Environmental standards will need to be developed to guide future mineral extraction enterprises. With the current state of mining technologies and likely proximity of mineral interests to environmental resources, the regulation of activities within targets for sustainable ocean management and environmental standards will be a key barrier to industrial growth.

Tourism

Tourism is the primary driver of Fiji’s economy, which inevitably means coastal tourism with the vast majority of infrastructure and hotspots located close to the ocean. The development of the industry was guided by Fiji Tourism 2021, administered by the Ministry of Tourism within the Ministry of Commerce, Trade, Tourism and Transport. The Ministry of Tourism is, as of writing, undergoing a strategic development process. It expects to produce an updated tourism management and development framework with a longer-term focus (over five to ten years).

The most detailed tourism plans from the government are in the 5-year and 20-year National Development Plan (Ministry of Economy, 2017[33]). The National Development Plan outlines two aims: expand the range of tourism products and market Fiji as a provider of niche, high-value tourist opportunities including diving; and enhance access to the tourism market among local communities.

Tourism in Fiji is dominated by large-scale operators, and the NOP recognises the need to help local communities enter and claim some of the market share (Republic of Fiji, 2021[1]). The NOP identifies tourism as a major development opportunity, and a central contribution to the country’s economy. It has two primary goals: mitigate the environment impacts of tourism; and develop sustainable tourism opportunities that are inclusive.

The inclusivity of the tourism industry in Fiji has been recognised as a challenge since the redevelopment of the sector and production of the Tourism Development Plan in 2003 while the industry was growing rapidly (Levett and McNally, 2003[64]). The strategic environmental assessment of the plan found that, among many challenges, a critical limitation to the equitable benefit from the tourism industry in the country was the effective utilisation of governmental instruments to ensure that tourism developments were inclusive. This finding is encapsulated in the NOP’s strategic outputs and indicators for the industry:

Strategic Output 5.2, Indicator 3: “Develop inclusive sustainable tourism that addresses climate change and pollution, regenerates ecosystems, builds resilience and reduces inequality” (Republic of Fiji, 2021, p. 61[1]).

Strategic Output 5.2, Indicator 4: “Strengthen participatory local and international stakeholder engagement in tourism management systems to improve environmental and social outcomes” (Republic of Fiji, 2021, p. 61[1]).

References

[44] Adan, R. (2000), “Requirements for fishpond lease: Things you need to know and do”, SEAFDEC Asian Aquaculture, Vol. 22/2, pp. 13-14, http://repository.seafdec.org.ph/bitstream/handle/10862/1652/Adan2000-requirements-for-fishpond-lease.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[32] Akroyd, J. and K. McLoughlin (2017), “MSC sustainable fisheries certification – Fiji albacore and yellowfin tuna longline: Final report”, report commissioned by Fiji Fishing Industry Association MSC, Acoura, January.

[45] Beveridge, M. et al. (2010), “Barriers to aquaculture development as a pathway to poverty alleviation and food security”, OECD Workshop Paris, 12-16 April, Worldfish Center, https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/fisheries/45035203.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[37] Boyd, C. and C. Tucker (2012), Pond Aquaculture Water Quality Management..

[47] Dauda, A. et al. (2019), “Waste production in aquaculture: Sources, components and managements in different culture systems”, Aquaculture and Fisheries, Vol. 4/3, pp. 81-88, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AAF.2018.10.002.

[8] Department of Environment, Government of Fiji (2020), National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2020–2025, Department of Environment, Government of Fiji, Suva, https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/fj/fj-nbsap-v2-en.pdf.

[57] Ecorys (2012), Blue Growth - Scenarios and Drivers for Sustainable Growth from the Oceans and seas, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/maritimeforum/system/files/Subfunction%203.6%20Marine%20mineral%20resource_Final%20v120813.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

[60] Feichtner, I. (2019), “Sharing the Riches of the Sea: The Redistributive and Fiscal Dimension of Deep Seabed Exploitation”, European Journal of International Law, Vol. 30/2, pp. 601-633, https://doi.org/10.1093/EJIL/CHZ022.

[10] Fiji, R. and IUCN (1992), National Environment Strategy.

[61] Folkersen, M., C. Fleming and S. Hasan (2019), “Depths of uncertainty for deep-sea policy and legislation”, Global Environmental Change, Vol. 54, pp. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2018.11.002.

[39] Goldberg, L. et al. (2020), “Global declines in human-driven mangrove loss”, Global Change Biology, Vol. 26/10, pp. 5844-5855, https://doi.org/10.1111/GCB.15275.

[16] Govan, H. et al. (2008), “Locally managed marine areas: A guide to supporting community-based adaptive management”, Locally-Managed Marine Area Network, https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=GB2013203237.

[17] Govan, H. et al. (2009), Status and potential of locally-managed marine areas in the Pacific Island Region: meeting nature conservation and sustainable livelihood targets through wide-spread implementation of LMMAs, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46446261_Status_and_potential_of_locally-managed_marine_areas_in_the_Pacific_Island_Region_meeting_nature_conservation_and_sustainable_livelihood_targets_through_wide-spread_implementation_of_LMMAs (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[30] Hare, S. et al. (2021), The western and central Pacific tuna fishery: 2020 overview and status of stocks..

[53] Herzig, P. (1999), “Economic potential of sea-floor massive sulphide deposits: Ancient and modern”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, Vol. 357/1753, pp. 861-875, https://doi.org/10.1098/RSTA.1999.0355.

[26] IRP (2021), “Governing coastal resources: Implications for a sustainable blue economy”, Report of the International Resource Panel, United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/en/publications/governing-coastal-resources-implications-for-a-sustainable-blue-e.

[54] ISA (2021), Small Island Developing States and the Law of the Sea, https://isa.org.jm/files/files/documents/SIDs_and_the_law_of_the_sea.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[15] IUCN (2013), “Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories”, webpage, http://www.iucn.org/pa_guidelines (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[64] Levett, R. and R. McNally (2003), A Strategic Environmental Assessment of Fiji’s Tourism Development Plan, WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

[28] Makino, A. et al. (2013), “Integrated planning for land–sea ecosystem connectivity to protect coral reefs”, Biological Conservation, Vol. 165, pp. 35-42, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320713001778.

[56] Mancini, L. and S. Sala (2018), “Social impact assessment in the mining sector: Review and comparison of indicators frameworks”, Resources Policy, Vol. 57, pp. 98-111, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESOURPOL.2018.02.002.

[33] Ministry of Economy (2017), 5-Year & 20-Year National Development Plan, Ministry of Economy, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://www.fiji.gov.fj/getattachment/15b0ba03-825e-47f7-bf69-094ad33004dd/5-Year-20-Year-NATIONAL-DEVELOPMENT-PLAN.aspx (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[35] Ministry of Fisheries (2019), Strategic Development Plan 2019 – 2029, Ministry of Fisheries, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://www.fisheries.gov.fj/images/STRATEGIC_PLAN_2019-_2029.pdf.

[49] Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport (2015), Maritime Transport Policy, Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[9] Ministry of Strategic Planning, National Development and Statistics (2014), A Green Growth Framework for Fiji, Ministry of Strategic Planning; National Development; Statistics, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[4] Ocean Panel (2021), 100% Sustainable Management: An Introduction to Sustainable Ocean Plans, report commissioned for High Level Panel on a Sustainable Ocean Economy.

[3] Ocean Panel (2020), Integrated Ocean Management, webpage, http://www.oceanpanel.org/blue-papers/integrated-ocean-management (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[46] O’Garra, T. (2012), “Economic valuation of a traditional fishing ground on the coral coast in Fiji”, Ocean & Coastal Management, Vol. 56, pp. 44-55, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OCECOAMAN.2011.09.012.

[36] Pakoa, K. et al. (2013), “The status of sea cucumber resources and fisheries management in Fiji”, Secretariat of the Pacific Communiity, Noumea (New Caledonia), https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=XF2016002122.

[1] Republic of Fiji (2021), National Ocean Policy 2020-2030, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://library.sprep.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/Fiji-National-Ocean-policy-2020-2030.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[29] Republic of Fiji (2020), National Fisheries Policy, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://www.fisheries.gov.fj/images/National_Fisheries_Policy_draft_June_2020.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[25] Republic of Fiji (2017), National Liquid Trade Waste Policy – For Discharges to Wastewater Systems Owned and Operated by Water Authority of Fiji, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[34] Republic of Fiji (2016), Aquaculture Bill 2016, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[22] Republic of Fiji (2016), Climate Change and Health Strategic Action Plan, https://www.health.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Climate-Change-and-Health-Strategic-Action-Plan-2016-2020.pdf.

[23] Republic of Fiji (2015), Environment and Climate Adaptation Levy Act 2015, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[50] Republic of Fiji (2013), Fiji National Energy Policy 2013-2020, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[48] Republic of Fiji (2013), Maritime Transport Act, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://laws.gov.fj/Acts/DisplayAct/2799 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[6] Republic of Fiji (2012), Offshore Fisheries Management Decree, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[21] Republic of Fiji (2011), National Solid Waste Management Strategy, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[19] Republic of Fiji (2008), Litter Act 2008, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://www.laws.gov.fj/Acts/DisplayAct/725 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[5] Republic of Fiji (2005), Environment Management Act, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[52] Republic of Fiji (2005), Sea Ports Management Act, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[41] Republic of Fiji (1992), Forest Act 1992 – Laws of Fiji, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://www.laws.gov.fj/Acts/DisplayAct/636 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[51] Republic of Fiji (1985), Ports Authority of Fiji Act, Republic of Fiji, Suva, http://www.paclii.org/fj/legis/consol_act_OK/paofa281/.

[20] Republic of Fiji (1977), Marine Spaces Act, Republic of Fiji, Suva.

[7] Republic of Fiji (1970), Continental Shelf Act 1970 - Laws of Fiji, https://www.laws.gov.fj/Acts/DisplayAct/752.

[62] Republic of Fiji (1965), Mining Act 1965 – Laws of Fiji, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://www.laws.gov.fj/Acts/DisplayAct/3039 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[40] Republic of Fiji (1945), State Lands Act 1945 – Laws of Fiji, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://www.laws.gov.fj/Acts/DisplayAct/354 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[24] Republic of Fiji (1944), iTaukei Affairs Act 1944 – Laws of Fiji, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://laws.gov.fj/Acts/DisplayAct/3252 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[14] Republic of Fiji (1941), Fisheries Act 1941 - Laws of Fiji, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://www.laws.gov.fj/Acts/DisplayAct/628 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[13] Republic of Fiji (1905), iTaukei Lands Act 1905 – Laws of Fiji, Republic of Fiji, Suva, https://www.laws.gov.fj/Acts/DisplayAct/400 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[12] Republic of the Philippines (1992), Republic Act No. 7586, Republic of the Philippines, Manila, https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1992/06/01/republic-act-no-7586/.

[38] Spalding, M. (2010), World Atlas of Mangroves, Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849776608/WORLD-ATLAS-MANGROVES-MARK-SPALDING.

[18] SPREP (2020), Stocktake of Existing and Pipeline Waste Legislation: Republic of Fiji, 16 March, Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme, https://www.sprep.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/waste-legislation-fiji.pdf.

[59] Stratmann, T. and et al (2018), “Abyssal plain faunal carbon flows remain depressed 26 years after a simulated deep-sea mining disturbance”, bg.copernicus.org, https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/15/4131/2018/ (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[11] Sykes, H. et al. (2018), Biophysically Special, Unique Maine Areas of Fiji, MACBIO (GIZ, IUCN, SPREP), Wildlife Conservation Society and Fiji’s Protected Area Committee (PAC), Suva, http://macbio-pacific.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Fiji-SUMA-digital-small.pdf.

[27] Thia-Eng, C. (1993), “Essential elements of integrated coastal zone management”, Ocean & Coastal Management, Vol. 21, pp. 81-108, http://seaknowledgebank.net/sites/default/files/essential-elements-of-integrated-coastal-zone-management_0.pdf.

[2] Underdal, A. (1980), “Integrated marine policy: What? Why? How?”, Marine Policy, Vol. 4/3, pp. 159-169, https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-597X(80)90051-2.

[63] UNGA (1982), United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, United Nations General Assembly, New York.

[58] Van Dover, C. (2010), “Mining seafloor massive sulphides and biodiversity: What is at risk?”, ICES Journal of Marine Science, Vol. 68/2, pp. 341-348, https://doi.org/10.1093/ICESJMS/FSQ086.

[43] Watling, D. (2013), Mangrove Management Plan for Fiji 2013, report commissioned by the National Mangrove Management Committee.

[42] Watling, D. (1985), Mangrove Management Plan 1985..

[31] WCPFC (2000), Convention on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, Western & Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, https://www.wcpfc.int/doc/convention-conservation-and-management-highly-migratory-fish-stocks-western-and-central-pacific.

[55] Worlanyo, A. and L. Jiangfeng (2021), “Evaluating the environmental and economic impact of mining for post-mined land restoration and land-use: A review”, Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 279, p. 111623, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2020.111623.

Note

← 1. ‘Tabu’ is an expression in the local language and it stands for no take areas.