4. Ensuring that training is of high quality and aligned with skill needs

In order for training to be effective and attain the desired objectives it needs to be of high quality and aligned with skills needs. This chapter analyses the extent to which training programmes provided by or available to SMEs are useful, of high quality, and aligned with labour market needs. The chapter also provides examples of national policies implemented in Korea to promote training quality and presents international good practice examples from OECD countries.

High training quality is key to ensure that SMEs and SME workers can make the most of adult learning programmes. This chapter analyses whether training is useful, of high quality, and aligned with labour market needs. The key findings of this chapter can be summarised as follows:

-

The usefulness of training could be improved in Korea. Only a third of SME workers find their formal or non-formal job-related training activity very useful for their job – well below the OECD average of 53% and lower than any OECD country except for Japan.

-

Training is associated with positive wage returns for SME workers in Korea, suggesting potential gains in productivity. SME workers’ participation in formal and non-formal training is associated with higher wages (8% and 10% more respectively). For workers in larger firms, wage returns are virtually inexistent, probably reflecting seniority-wage practices rather than low-quality training.

-

More could be done to build the capacity of SMEs to provide training that addresses their skill gaps. The key challenge is that Korean SMEs often lack the capacity to assess their skill needs beyond the short-term. In Korea, 28.3% of small firms, 24.6% of medium-sized firms, and 17% of large firms do not at all review the skills and competences required by employees based on the business environment and company strategy.

-

Korea has a plethora of Skills Assessment and Anticipation (SAA) information, which is used by policy makers to design adult learning strategies, develop training programmes, and determine whether subsidies should be allocated to adult learning programmes/providers or not. However, SAA information could be better leveraged to help SME workers make informed career decisions. Indeed, SAA information is often scattered, delinked, and dispersed across different online platforms, making it difficult to use.

-

The recent development of National Competency Standards is an important step forward to make skills development more aligned with labour market needs. However, there are implementation challenges, including the mismatch between NCSs and industry needs; the rapid obsolescence of the NCSs framework; as well as the lack of expertise of teachers and lecturers in adopting NCSs.

-

Digital skills are crucial in the context of the 4th industrial revolution. Yet, some 72% of workers in micro-firms have low problem-solving skills in technology-rich environments, a rate that declines evenly to 50% in large firms. Despite this challenge, IT-related training is the least frequently provided training in SMEs. What is more, publicly financed training programmes related to the 4th industrial revolution are scant. Industry 4.0 training programmes are typically more expensive than more traditional courses, and public subsidies are often insufficient to cover such costs.

-

Adult learning teachers should be better prepared to teach the skills needed for a changing world of work. Adult learning teachers do not participate enough to refresher training, partly reflecting the fact that continuous training is not mandatory to continue teaching.

Introduction

In order for training to be effective it needs to be of high quality and aligned with skills needs. Indeed, increasing participation is unlikely to have the desired impact on skills if training is of low quality. This chapter analyses the extent to which training programmes provided by SMEs and/or attended by SME workers are useful, of high quality, and aligned with needs.

This chapter is structured as follows. Section 4.1 presents subjective and objective indicators of training quality, drawing from international data sources and placing Korea in the international context. Section 4.2 discusses how to build the capacity of SMEs to train for a changing world of work. Section 4.3 presents how skills assessment and anticipation (SAA) information is collected and used to align training with labour market needs. Section 4.4 discusses existing adult learning monitoring and quality assurance mechanisms. Section 4.5 discusses how training programmes are kept up to date, particularly in the context of the 4th industrial revolution.

4.1. Is training of good quality?

Measuring training quality is not an easy task, as quality is multi-dimensional in nature and is often subjective. This section discusses two specific aspects of training quality, drawing upon internationally comparable data: 1) usefulness of training; and 2) wage returns to training. While these dimensions reflect important aspects of the quality of adult learning programmes, they do not provide a full picture. Additional information is needed to draw a more complete picture of adult learning quality in Korea in comparison to other OECD countries.

4.1.1. Usefulness of training

One way to measure training quality is to assess whether workers perceive training as being useful for their job. The self-reported usefulness of training reflects a personal judgement of the training content, and as such, it reveals one subjective aspect of training quality.

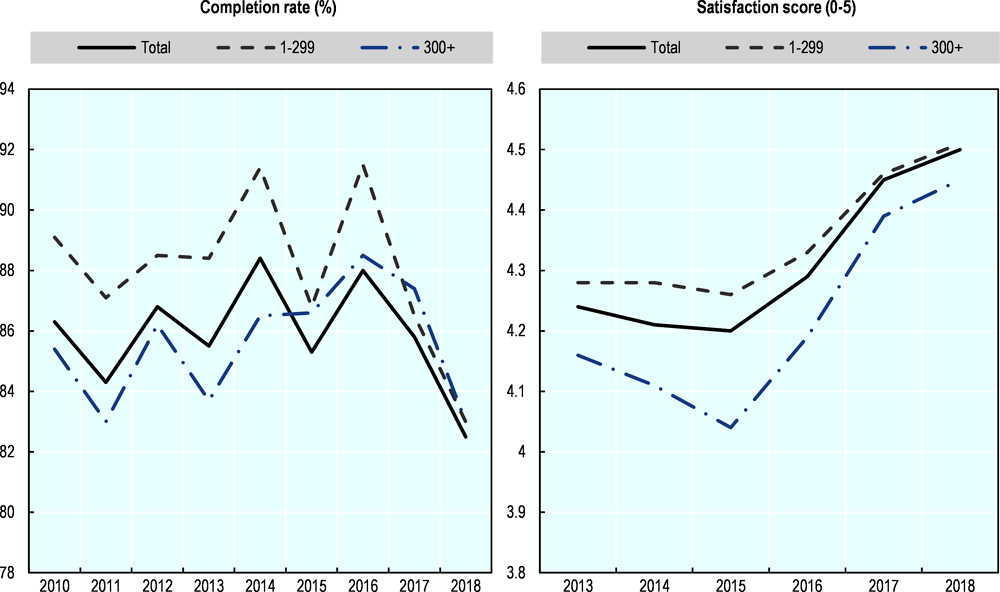

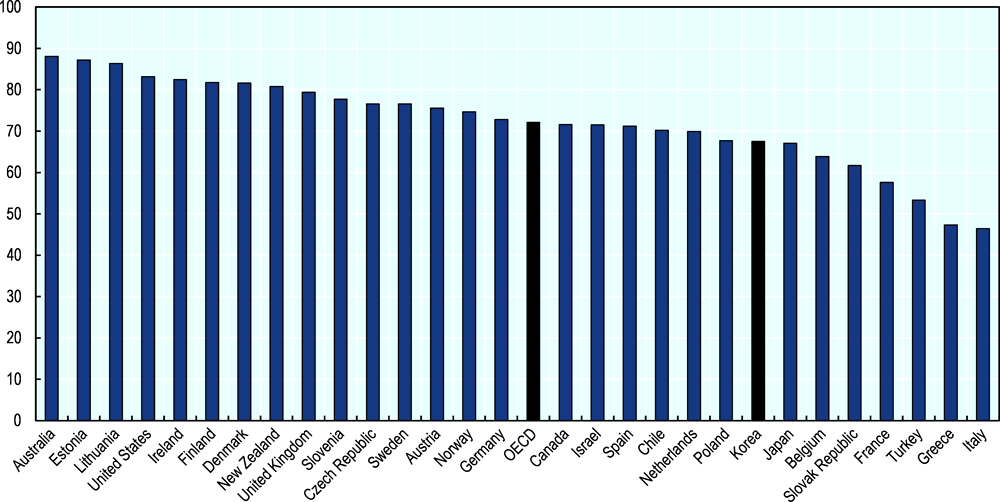

In Korea, SME workers seem to be much less satisfied with training than their peers in other OECD countries (OECD, 2019[1]), according to data from the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC). Only a third of SME workers found their formal or non-formal job-related training activity very useful for their job – well below the OECD average of 53% and lower than any OECD country except for Japan (Figure 4.1).

However, SME workers in Korea seem to be slightly more satisfied with training compared to workers in larger companies. The gap between workers in larger companies and SME workers in Korea is 5 percentage points – well above the OECD average (0.6 percentage points) and above some OECD countries where the gap is negative (Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Turkey) or less marked (Figure 4.1).

It is noteworthy that there might be a link between quantity and perceived quality of training. For example, the fact that in Korea SME workers are more satisfied with training than workers in larger companies, can be due to the fact that they train considerably less than workers in larger companies (see Chapter 2), and as a result that they value more the few training programmes they pursue.

4.1.2. Wage returns to training

Wage returns assess the extent to which workers’ training participation leads to higher wages. To the extent that wages increases are aligned with increases in the participant’s productivity, they can be interpreted as a proxy for training quality.

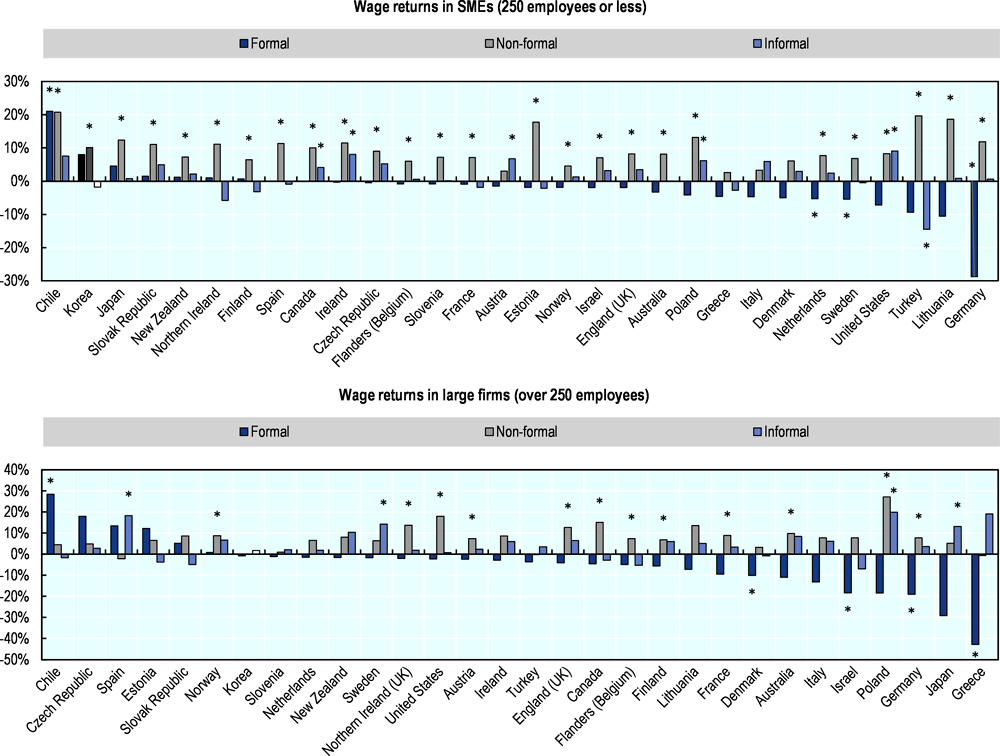

Using the framework developed by Fialho, Quintini and Vandeweyer (2019[2]), and exploiting PIAAC data, it is possible to estimate the wage returns to training in Korea and other OECD countries. The analysis distinguishes between returns to formal, non-formal and informal training, controlling for a range of individual, job and firm characteristics. The analysis presented in this chapter also disentangles results between SME workers and workers in larger firms.

As shown in Figure 4.2, in Korean SMEs, workers’ participation to formal and non-formal training is associated with higher wages, while informal training (i.e. learning by doing the job, learning from others, or learning new things at work at least once a week) negatively correlates to wages. More specifically, formal training participants earn approximately 8% more than non-participants with similar characteristics and in similar jobs and firms, the second highest wage return in the OECD after Chile. Non-formal training participants earn 10% more, just above the OECD average of 9.6%. Conversely, workers exposed to informal learning at least once a week earn approximately 1.7% less than workers not exposed to it. However, the results are statistically significant only for non-formal training.

Interestingly, a completely different picture emerges when looking at workers in larger firms, where wage returns are virtually inexistent regardless of the type of training considered (Figure 4.2). These results could be explained by the fact that larger firms in Korea often adopt seniority-wages, where pay increases are related to workers’ seniority rather than productivity and performance (see Chapter 3). It is important to note that for Korea, the results for workers in large firms are not statistically significant regardless of the type of training considered.

It is noteworthy that wage returns might reflect factors unrelated to training quality, and therefore results should be taken with caution. For example, wage returns may reflect the degree of flexibility in the wage-setting process. Most importantly, low wage returns may reflect the appropriation by firms of the returns to training.1 Or, workers may be sent on a training course by their employers to prepare them for a promotion, in which case the wage increase would take place irrespective of productivity gains. Finally, wage returns could also reflect the types of training programmes typically pursued by workers. Indeed, some courses (e.g. health and safety training) are by definition not intended to have any impact on wages. For these courses, low wage returns are unlikely to reflect low training quality.

4.2. Building the capacity of SMEs to train for a changing world of work

SMEs – and firms more generally – have an interest in keeping the skills of their employees up to date, so that they can introduce new technologies and work-organisation methods and stay competitive.

To achieve this objective, SMEs need to understand what skills they need for the development of their businesses. Although SMEs can partly rely on SAA information to understand the training needs of their sector (see Section 4.3), companies also need to improve the assessment of their own skill needs.

In Korea, firms, and especially SMEs, often lack the capacity to assess their skill needs beyond the short-term. They may not have the technical capacity, the financial resources, or the time to undertake such assessments. As a result, many firms (especially smaller firms) do not conduct skills assessment and anticipation analysis on a regular basis.

In Korea, 28.3% of small firms, 24.6% of medium-sized firms, and 17% of large firms do not at all review the skills and competences required by employees based on the business environment and company strategy – according to Workplace Panel Survey (WPS) 2015 data. Only between 14% and 23% of firms, depending on firm size, review the required skills and competences of their employees on a regular basis (Figure 4.3). The remainder of firms carry out such analysis only on an irregularly.

On top of improving the assessment of their skills needs, firms also need to be able to provide relevant training that addresses skill gaps and prepares employees for the future. However, employers do not always provide training on the skills they need the most.

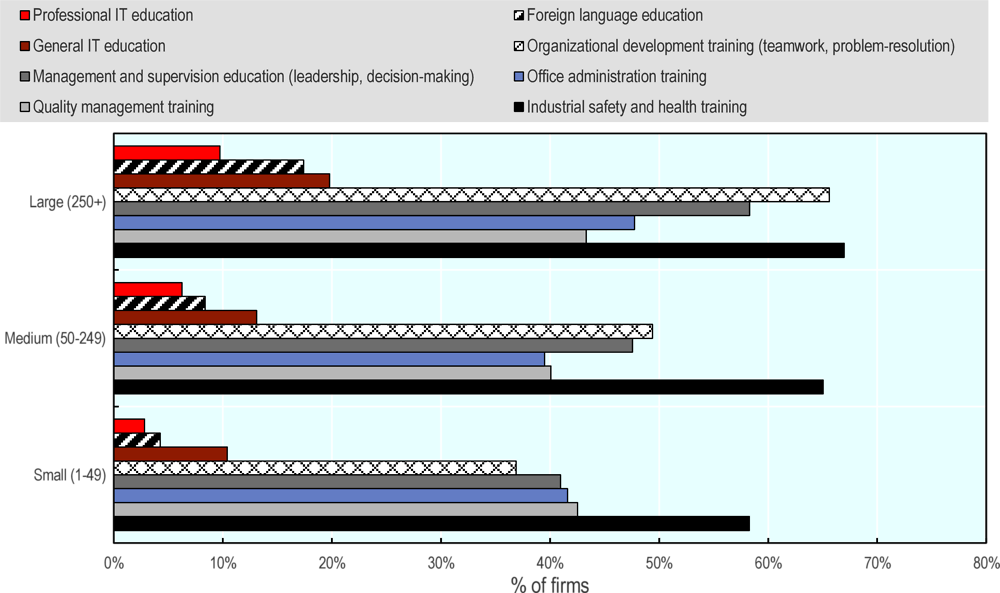

One key challenge is that Korean SMEs often provide only or mainly mandatory training. Industrial safety and health training is the training programme most frequently provided by SMEs (as well as larger firms), as shown in Figure 4.4. And as discussed in Chapter 3, some 53.7% of small firms and 44.2% of medium-sized firms provide only mandatory training to their workers. While knowledge on health and safety is certainly important to reduce work accidents, it does not help in addressing skill gaps or preparing the workforce for emerging skill needs.2

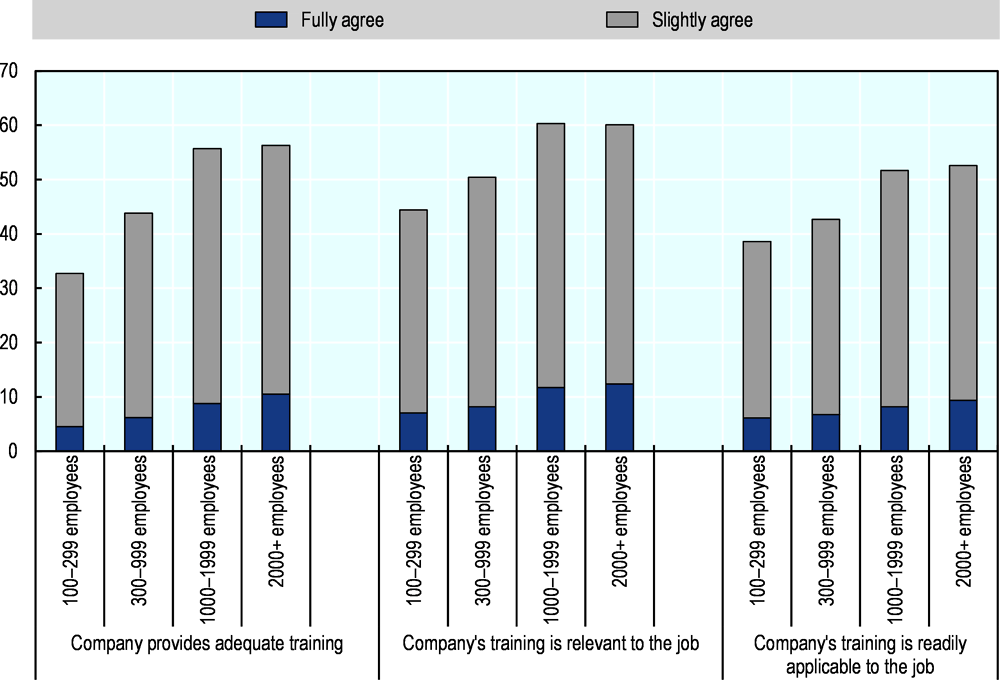

Another challenge is that training (beyond mandatory) is not always of the highest quality, particularly in SMEs. Looking at national employers and employees’ surveys, it seems evident that SMEs (and their workers) are not as positive as large firms (and their workers) about the quality, usefulness, and results of company’s official training.3 This is not so surprising, considered that SMEs rarely have the facilities, infrastructures, as well as the financial and human capital resources to provide high-quality training (see Chapter 3).

For example, according to the Human Capital Corporate Panel Survey (HCCP) (2017) data, only 32.7% of workers in SMEs “fully” or “slightly” agree that their company provides adequate training, 44.4% agree that their company’s training is relevant for the job, and 38.6% that their company’s training is readily applicable to the job (Figure 4.5). These rates are systematically higher in larger firms.4

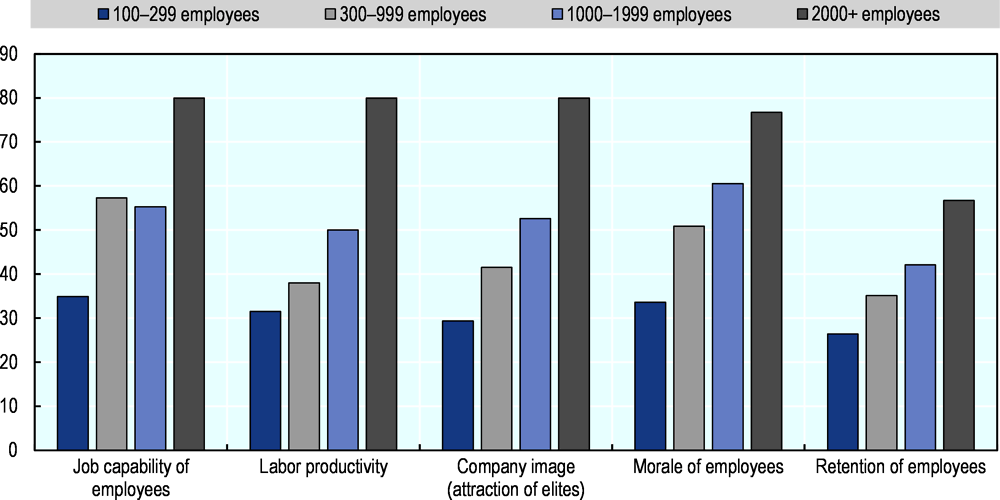

Similarly, SMEs themselves seem to be less satisfied about the impact that their training has on their workers. According to the HCCP data, only 35% of medium-sized firms in 2017 reported that training “highly” or “somewhat” improved the job capability of employees. A minority of medium-sized firms reported that training improved labour productivity (32%), company image (29%), morale of employees (34%), and retention of employees (26%) (Figure 4.6). These rates are systematically lower than rates observed in larger companies.

Firms should also monitor the quality of the training offered to their workers. This monitoring can allow firms to identify the impacts of training on staff’s performance, and adjust future training choices accordingly. Yet, many Korean companies still do not monitor whether their training has reached the desired objectives and brings effective outcomes (EPF, 2017[3]). This is particularly true among SMEs. According to WPS data, some 66% of small firms, 55% of medium-sized firms and 29% of large firms did not implement any evaluation of training in the year preceding the survey (Figure 4.7). Unlike what happens in Korean SMEs, most large companies seem to conduct, at least, a trainee satisfaction survey.

Korea has already implemented several projects to support SMEs to better understand their training needs and offer training accordingly, in line with good practices in OECD countries. These projects include the SME training (support) centres, the S-OJT project, and the ‘Subsidies for Learning Organisations’ (see Chapter 3 for a full description of these programmes):

-

SME Training (Support) Centres aim to tackle the lack of HRD capabilities of SMEs, by supporting business guidance, company diagnosis, as well as training programme design in SMEs. In 2019, operation institutions include Chambers of Commerce and Industry, employers association, Korea Tech and other institutions. The amount of support for each centre is KRW 600 million (approximately EUR 460 000).

-

S-OJT project. This is a subsidy that covers the cost of training, job analysis/module development, training delivery, and assessment of results. The average annual support for each company is KRW 24 million in 2019 (approximately EUR 18 500).

-

Subsidies for Learning Organisations provides SMEs with financial support to hire external consultants to analyse the company’s training needs, build the capacity of the CEO and managers, and accompany the process of becoming a learning organisation.5 The subsidy covers 70% of the cost of hiring an external consultant, up to a maximum of KRW 3 million per firm (approximately EUR 2 265).

These programmes provide targeted coaching to companies to identify their skill needs, and offer financial incentives alongside advice and guidance, in line with international best practices (OECD, 2019[4]). However, take-up remains low. For example, the S-OJT programme is still at its early stage of development and today remains quite small scale, with only 122 selected companies in 2018. Similarly, in 2018, only 91 SMEs were supported from the Subsidies for Learning Organisations programme. To increase take up, Korea could task Regional and Industry Skills Councils with administering the programmes or informing firms about the existence of these programmes. Box 4.1 provides good practice international examples that Korea could learn from.

Korea should encourage SMEs to conduct an analysis of their training needs on a regular basis. For this to happen, Korea should increase the take-up of programmes that aim to help SMEs to better understand their training needs and offer training accordingly. Korea could task Regional and Industry Skills Councils with administering these programmes or informing firms about the existence of these programmes.

Finland

Finland has a financial incentive that goes hand-in-hand with building the capacity of companies to identify their training needs and deliver training. The Joint Purchase Training (Yhteishankintakoulutus) supports employers who want to retrain existing staff or set-up training programmes for newly recruited staff. Offered by the Public Employment Services (PES), it supports employers to define their training needs, select the appropriate candidates for training and find an education provider to deliver the tailored training. The PES also part-finances the training.

Germany

In Germany, the initiative ‘Securing the skilled labour base: vocational training and education (CVET) and gender equality (Fachkräfte sichern: weiterbilden und Gleichstellung fördern)’ supports social partners in increasing adult learning participation and gender equality at work. This initiative funds 93 projects. For example, one project aims to create staff development structures in utility companies in the three German cities of Coburg, Kronach and Lichtenfels. Companies receive coaching and training for key staff on analysing their skill and training need, practical ways of introducing staff development structures and working with partners.

Source: OECD (2019[4]), Getting Skills Right: Creating responsive adult learning systems, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/adult-learning-systems-2019.pdf.

4.3. Assessing and anticipating changing skills needs

Skills assessment and anticipation (SAA) exercises are tools used to collect information on current and future skills needs. SAA exercises collect information on where (i.e. in what economic sectors, occupations, or geographic areas) and when (i.e. now, in the future) the demand and supply of skills are misaligned (OECD, 2016[5]). In adult learning, this information can be used to guide policy makers, training providers, firms, and adults on what training programmes to provide and/or choose. This section looks at 1) the collection of skills assessment and anticipation (SAA) information; 2) the use of SAA in adult learning policy; and 3) how SAA can be used to help (SME) workers make informed training decisions.

4.3.1. Collecting skills assessment and anticipation analysis

In Korea, there is a plethora of SAA exercises to monitor current and future labour force supply and demand. These exercises pursue different objectives, are conducted by different (mainly institutional) organisations, present information at different levels of granularity/aggregation, use different time horizons (current, future), and adopt different dissemination practices to make the results publicly available. The most important SAA exercises include:

-

Occupational Labour Force Survey at Establishments. The survey is conducted every six months by the MoEL. The purpose of the survey is to collect information on current labour demand and shortages. Indicators collected include the current number of employees, number of new hires, number of vacancies, scheduled number of employees to be hired, reasons for not hiring. Indicators are disaggregated by occupation, industry, firm size, region, and skill level.6 The results of the survey are available on a dedicated website and are published in a report twice a year (see Chapter 1).

-

Medium- to Long-Term Labor Demand and Supply Forecast. This forecast exercise is conducted every year by the Korea Employment Information Service (KEIS). It identifies and anticipates long-term skills supply and demand at the macro level, covering a time-span of ten years. Results are disaggregated at the industry, occupation, and skills level. The results of the forecast are available on a dedicated website, they are published in an annual report, and micro-data are also accessible.

-

Regional and Industry Skills Councils Surveys. Since 2013, Skills Councils conduct an annual survey on training and skills demands for each region and sector of the economy, on around 2 500 companies. The results of the analysis are published in an annual report and is available on a dedicated website, and micro-data are also available.

-

Labor Supply and Demand Forecast Caused by the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Conducted every year by the MoEL, the exercise aims to forecast industry-specific growth, looking at the number of employees by industry and occupations on a time-horizon of about 15 years. The results of the survey are available on a dedicated website, and they are also published in an annual report.

Table 4.1 provides a summary of these and other SAA exercises available in Korea.7 On top of these institutional assessments, training providers sometimes also independently conduct skills needs surveys to better understand the training needs of firms and develop an adequate training offer. For example, in order to develop training programmes aimed at improving the job competencies of workers,8 several Korean Polytechnic Universities conduct a demand survey among enterprises at the end of each year.

4.3.2. Making use of SAA information

The collection of skill assessment and anticipation (SAA) information is not a self-serving tool. Its key purpose is to inform policy-makers, firms, training providers, and individuals, so that they can provide/access appropriate adult learning programmes that address current and emerging skill gaps.

Like in other OECD countries, SAA information in Korea is used in a number of policy fields, including adult learning (OECD, 2016[5]). One of its main uses is to develop adult learning programmes that respond to the needs of firms. To give one example, the results of Surveys on Regional Workforce and Vocational Training Need and the Industry Skills Councils Surveys are used to develop region/industry-customised training programmes (HRD Korea, 2017[6]). This information is also used by the MoEL to shape public adult learning programmes (e.g. Work-Study Dual System) and by the Public Employment Services to identify their training offer.

SAA information is also used to determine whether financial subsidies should be allocated to adult learning programmes/providers or not. For example, in the National HRD Consortium Programme (see Chapter 3), demand surveys are conducted via e-mail, and several stakeholders – e.g. firms, employers’ organisations, and other government-recommended associations – are consulted to evaluate whether training corresponds with their needs. Training programmes that are based on demand surveys are more likely to receive government funding, and surveys that are poorly conducted can lead to disqualification.

On top of guiding training providers, SAA information is also used by policy makers to design national strategies/policies on adult learning. To give one example, the results of the 5th Science and Technology Foresight analysis fed into the ‘4th Master Plan for Science and Technology’ (2018-2022) (Ministry of Science and ICT, 2017[7]). Similarly, the “The Innovation Plan for Vocational Competency Development in response to labour market changes” developed by the MoEL in 2019 reflects the results of “Labor Supply and Demand Forecast Caused by the Fourth Industrial Revolution’’.

4.3.3. Helping workers make informed training choices

SAA information should also be leveraged to help workers make informed career decisions – e.g. through career guidance that makes full use of SAA information. Training choices have important implications for workers’ lives. They can influence their income, well-being, job-security, and career progression opportunities. However, it can be difficult for workers to understand which occupations and skills are most in demand in the labour market. It is also a challenge for them to identify whether their skills are up to date and are still relevant for their jobs/occupations. Hence, tailored information on training must be available to all workers. As discussed in Chapter 3, in Korea SAA information is often scattered, delinked, and dispersed across different online platforms. Many users may find it difficult to navigate the existing SAA exercises and may struggle to find the information they are looking for. As suggested in Chapter 3, going forward Korea should create a one-stop-shop solution to career guidance, in line with practices already adopted in other OECD countries.

4.4. Monitoring and ensuring high-quality adult learning programmes

The Korean adult learning system is characterised by a large number of training programmes, delivered by a multitude of training providers, including government bodies, public and private training providers, and firms’ in-house training.9 In such a large and scattered market, ensuring that training meets basic quality standards is key to ensure that workers and firms have access to good quality options.

In Korea, two national bodies are responsible for assessing and monitoring the quality of the adult learning system: the Korean Skills Quality Authority (overseeing public and private training provision) and HRD Korea (overseeing firms’ in-house training) (see Annex 4.A).

The Korean Skills Quality Authority (KSQA), established in April 2015 under the responsibility of the MoEL, is the national body dedicated to quality assurance in the adult learning sector (excluding firms’ in-house training). The KSQA is in charge of providing accreditation to training providers, assessing their effectiveness and quality, and detecting fraudulent practices (see Annex 4.A for a description).

The KSQA provides accreditation to training providers that meet certain minimum quality standards. After a thorough assessment of training outcomes (such as completion rates, satisfaction surveys), and of the adequacy of on-site operations and facilities (such as trainers, facilities and equipment) the KSQA provides a score (up to 100 points) that reflects overall performance (Table 4.2). If the training provider receives a score inferior to 60, the request for accreditation is rejected.

The KSQA-accreditation is valid for a period of 1, 3 or 5 years, depending on overall performance. In 2018, 26% of training providers were not given/renewed accreditation because they did not meet minimum quality criteria. 1-year accreditation was granted to 62.5% of the training providers assessed, 3-year accreditation was given to 10%, and 5-year accreditation was given to only 0.8% (Table 4.3).

But the work of the KSQA goes beyond accreditation. As described in detail in Annex 4.A, accredited training providers are monitored on a regular basis by KSQA, the performance of their training offer is assessed regularly, and they are audited to ensure that they do not engage in fraudulent practices.

KSQA’s assessments and evaluations are used in several important ways to improve the quality of the Korean adult learning system. For example, they are used to:

-

Establish the level of government financial support. Korea adopts a performance-based funding system, whereby the outcomes of KSQA accreditation processes and audits are directly reflected in government funding decisions as well as the extent of administrative support provided by the government. For example, training providers that do not manage to receive KSQA accreditation are not entitled to receive any government financial support. 10

-

Provide excellence labels for best performing training providers. Training providers with good performance assessment results can participate to a call for best practice tender and be designated as ‘organisation of excellence’.

-

Inform individuals/firms about the quality of each training provider/training course. The results of KSQA assessments and evaluations are available on HRD-net (see Chapter 3). By allowing individuals and employers to have access to relevant and up-to-date information on the quality of different training providers, the KSQA helps users to make informed choices about which training to invest in. Indirectly, this also creates a virtuous circle of competition among training providers that drives quality up.

HRD Korea’s branch offices are responsible for conducting regular evaluations of firms’ in-house training (e.g. training provided by the firm). Employers can apply for approval of a training course up until 5 days before the start of the training, and Korea’s branch offices decide whether to approve or reject the applications.

Basic requirements for approval include adequate training space and minimum training hours. For example, the training course is disqualified if it does not provide a dedicated learning space. Minimum training hours for employer-provided training should be at least 16 hours for 2 days (for SMEs, at least 8 hours for one day). Training content should also comply with minimum standards. For example, the training should be job-relevant and appropriate teaching staff should be provided. Training courses for hobbies, entertainment, sports, and classes to prepare for foreign language tests are rejected, and so are mandatory training courses (e.g. occupational health and safety, sexual harassment prevention, personal information protection).

During the training period, HRD Korea monitors training delivery to identify fraudulent or poor training practices. To do that, HRD Korea uses data collected from HRD-Net and other relevant databases, and carries out on-site visits. When on-site visits are not possible (e.g. because training takes place during the week-end or at night time), phone calls are conducted to check trainees’ attendance. Moreover, after the end of the firms’ in-house training, participants are asked to complete a survey designed to assess satisfaction with the operation and management of the training programmes, the on-the-job application of what was learned during the training, and skills improvement levels.

HRD Korea regional offices/branches are responsible for providing advice and guidance to companies that offer in-house training for the first time, e.g. on how to prevent fraud and low-quality training. Moreover, regional offices/branches collect information on training programmes and providers operating at the regional level, and report it to the headquarters every two months. The Training Quality Improvement Centre in the headquarters assembles this information in a comprehensive report that allows regions to benchmark themselves with one another.

HRD Korea headquarters also conduct a performance evaluation of their regional offices/branches. The evaluation assesses their performance based on a number of criteria, such as training completion rates; to what extent SMEs provide in-house training; whether regional offices/branches provide support for firms’ in-house training (e.g. competency-building training for in-house training staff; consultation prior to training); and whether regional offices/branches monitor training to prevent fraud.

As of today, for each training provider/training course, HRD-net includes information on quality. Quality indicators include completion rates, satisfaction of participants, and acquisition of units of competences based on the National Competency Standards (NCSs).11 As shown in Figure 4.8, completion rates of training programmes for employees have decreased in Korea over the past years, and particularly so among workers in SMEs. In 2010, 89% of workers in SMEs completed their training, a rate that decreased to 83% in 2018. Completion rates for workers in large firms have dropped by only 2 percentage points in the same period. On the other hand, satisfaction scores have increased for all training participants, including SME workers.

According to stakeholders interviewed in the context of this project, the indicators used to measure the quality of training for incumbent workers (e.g. completion rates; satisfaction rates) could be expanded and improved. Collecting adequate indicators on the quality of training providers/programmes is challenging, especially when it comes to training for incumbent workers (see Chapter 3).12 Perhaps Korea could learn from countries that collect more detailed indicators on training quality. In Singapore, for example, SkillsFuture SG has developed a Training Quality and Outcomes Measurement (TRAQOM) Survey Initiative that gather feedbacks from all training participants on quality and outcomes – at the end of the training as well as six months afterwards. The indicators include detailed satisfaction scores for quality (trainer and course content, learning, customer service), and outcomes (ability to apply learning; better job performance; expanded job scope).13

4.5. Keeping training content up-to-date

To keep abreast of changing skill needs in the labour market, adult learning systems need to dynamically respond to changes. Korea must put in place structures and mechanisms that allow for the continuous review of the training offer, the content of training and the delivery methods. This section discusses 1) the use of National Competency Standards in adult learning; 2) how to ensure that adult learning teachers are well-prepared; 3) the ability of the adult learning system to provide the skills for the 4th industrial revolution.

4.5.1. Using National Competency Standards in adult learning

Since 2013, Korea has been working on the development of a National Competency Standards (NCS) framework – in a joint initiative between the Ministry of Employment and Labour (MoEL) and the Ministry of Education (MoE). The framework defines a set of competencies (e.g. knowledge, skills, and attitudes) required to effectively perform a job or task in each industry (OECD, 2019[9]). A total of 1 001 NCSs have been developed by 2019.

With a strong push from the government, diverse groups of stakeholders – e.g. Industry Skills Councils, sectoral associations, corporates, and academia – participated in designing the NCS for all types of occupations.

The development of the NCSs is an important step forward to make skills development more aligned with labour market needs. For example, NCSs could be used to minimise the discrepancies between what training providers offer (and therefore what workers learn) and what industries need. Also, NCSs could prove an effective tool for recognising and validating the skills that workers have acquired throughout their careers, posing the basis for the development of a strong system of Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) (see Chapter 3).14 Further, NCSs could be used to conduct more accurate and granular skills assessment and anticipation (SAA) analysis – encouraging different actors to adopt the same definitions of skills. When used in recruitment practices, NCSs could encourage firms to focus on candidates’ practical skills and performance rather than their qualifications – a practice which could potentially help mitigate skills mismatches, and reduce biases in hiring. Finally, NCSs could support Korean transition away from seniority-wages and towards more job-oriented wage-setting practices, for example by linking jobs to a set of competencies in a clearer and more transparent way – which could have indirect consequences on workers’ motivation to train.

The government is already operationalising and promoting the effective use of the NCS in adult learning. For example, certain adult learning programmes (e.g. the Work and Study Dual System) are already developing around NCSs units. Public training institutions, such as Korean Polytechnics, are gradually developing/adjusting their curricula to integrate NCSs. Also private training providers are increasingly incentivised to use NCS-based modules. For example, the use of NCSs is one of the key criteria used by the KSQA to provide accreditation to, and assess the performance of, training providers (see Annex 4.A).15 All in all, among the 948 NCSs developed by 2018, 934 (98.5%) have been applied in vocational training and qualifications.

Despite NCSs’ potential benefits, and their ongoing implementation in adult learning, several stakeholders claim that the Korean adult learning system is not yet ready to make full use of NCSs. First, there seems to be a mismatch between NCSs and industry needs. Stakeholders consulted for the initial development of the NCS were not representative of all sectors in the economy, and industry involvement was relatively passive, with a weak mutual feedback system in place (Choi, 2015[10]).

Another key challenge is to update the NCSs framework to keep up with technology advances, especially in some sectors where new technologies are being introduced rapidly. With the rapid introduction of new technologies and in the context of rapidly changing labour markets, the NCSs gets outdated relatively quickly.16 In addition, as argued by several training providers, NCSs do not capture the skills taught in new, more innovative, training programmes – e.g. training that develops the skills needed for the 4th industrial revolution (see Section 4.5).

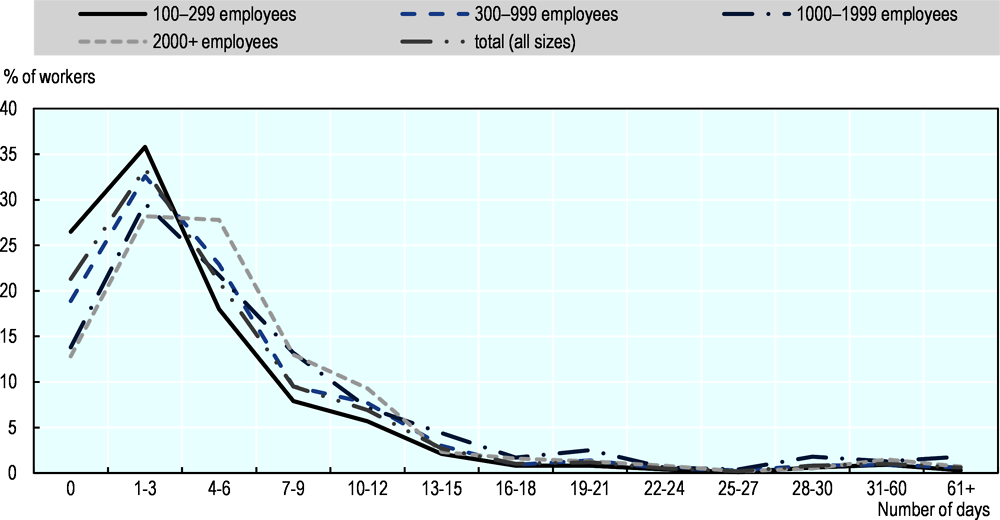

Another issue is training duration. Each NCS competency unit requires a different number of training hours17, and most require between 30 and 50 hours of training. However, adult learning courses typically last much less long than this, especially when offered by SMEs. For example, according to WPS data, for the vast majority of firms (59% of SMEs and 49% of larger firms), the average annual training time per person is 16 hours or less (Table 4.4). Elaborations of the HCCP data (2017) confirms that most training lasts between 1 and 3 days (Figure 4.9). To address this issue, Korea gives the training institution the flexibility to increase the training hours by up to 50% or reduce it to at least one hour for each unit.

Another challenge is that training providers are facing several obstacles to implement NCSs. The lack of expertise of teachers and lecturers in adopting NCSs, the increased workload related to learner evaluation, and demotivation due to frequent performance assessments – seem to be some of the strongest obstacles faced by training providers (Choi, 2015[10]).

Successful implementation of NCSs will also depend on the involvement of firms and workers, which will need to use the NCS in developing lifelong career paths and managing hiring and promotion. However, today workers/labour unions are not particularly interested in the NCS, given the firmly ingrained seniority-based wage system. Employer associations and firms are also not particularly interested in the NCSs unless they are given a strong incentive to recruit, train and assess workers based on these standards (OECD, 2015[11]).

The government is already implementing positive steps to favour a better implementation of the NCSs. For example, competency-based hiring and blind recruitment have been introduced into public sector firms since July 2017. Further, consulting on NCS-based hiring and personnel management has been provided to SMEs, with a total of 1 044 benefitting from the programme in 2018. In addition, in April 2019, the MoEL announced an innovation plan for NCS quality management, which will assess the status of the NCS and propose future directions for improvement.

In a view to enhance the adoption of NCSs by firms and training providers, Korea should:

-

Improve the process of developing/updating NCSs, ensuring that users’ views are fully reflected in the process. In particular, it will be crucial to expand the roles of industry and labour representatives in updating current NCSs and developing new ones. This will ensure that NCSs are aligned with industry needs.

-

Monitor the implementation of NCSs through dedicated assessments. These surveys should assess whether NCSs are being used by firms and training providers, and what challenges they are facing. The results should be used to review NCS-related processes accordingly.

-

Applying NCSs to training institutes in a more flexible way. For example, minimum NCS adoption standards for training should be eased. Training providers should be given greater autonomy in the provision of short-term (less than 40 hours) NCS-based training.

4.5.2. Preparing adult learning teachers

Ensuring that adult learning teachers are well prepared is key for training quality and for keeping training content up-to-date. Teachers need to participate in adult learning in order to keep pace with new emerging skills needs and the introduction of new technologies.

In Korea, training options for adult learning teachers exist but are not mandatory, and several observers argue that there is a need to develop adult learning teachers’ skills even after they have acquired the certificate to become a lifelong learning educator (NILE, 2015[12]; Yang and Yorozu, 2015[13]). A recent survey on the perception of refresher training shows that 58.1% of teachers and instructors agree or completely agree that they need refresher training (KoreaTech HRDI, 2019[14]).

According to PIAAC data, Korean teachers (including adult learning teachers) participate in training much less than teachers in other OECD countries. In Korea 67.5% of teachers participate in formal and non-formal job-related training in a given year, well below the majority of OECD countries and below the OECD average of 72.1% (Figure 4.10).

Another issue is that adult learning teachers generally face poor working conditions in Korea – with low and stagnating wages, and poor career advancement opportunities. This may make the profession little attractive and may also reduce teachers’ willingness to retrain and advance in their careers.

Korea could learn from the experience of neighbouring countries that have been taking positive steps in adult learning teachers’ continuous skills development. For example, in Singapore, SkillsFuture SG has put in place an Adult Education Network, i.e. a professional membership scheme that enhances professionalisation and continual skills development of adult educators. It offers a series of continuing professional development programmes and access to rich resources. To provide incentives to high-quality teaching, SkillsFuture SG also identifies adult educators recognised for pedagogical and professional excellence (SkillsFuture SG, 2019[15]).

Korea is already taking steps in the right direction. In January 2019, a bill on provision of regular refresher training for vocational teachers and instructors was brought to motion. The revision entails that vocational teachers shall regularly (every three years) attend vocational skill development projects such as refresher training provided by the MoEL. A plan announced in April 2019 aim to expand participation to refresher training from 13 000 in 2019 to 35 000 by 2020 (KoreaTech HRDI, 2019[14]).

To ensure the high quality of adult learning teachers, Korea should:

-

Make refresher training mandatory for adult learning teachers, as is currently being discussed by the government.

-

Enhance working conditions and wages of adult learning teachers as a way to make the profession more attractive and increase teachers’ willingness to train and upskill.

4.5.3. Providing the skills for the 4th industrial revolution

Digital devices and software are introduced and updated with increasing frequency. In Korea like in other OECD countries, adult learning systems need to provide training that develops and maintains (especially SME) workers’ ICT skills, help them work with new technologies, and prepare them for the needs of the 4th industrial revolution18 (OECD, forthcoming[16]).

There is a high and growing demand for digital skills among Korean firms. For example, a survey of 800 firms (including SMEs) conducted in 2014 by the Federation of Korean Industries (FKI), shows that for 77.5% of respondents, IT skills are the most needed skills in the world of work (FKI, 2014[17]).

Supply and participation to 4th Industrial Revolution training has increased in the past years, especially among SME workers. According to Seol (2019[18]), the number of SME workers that participated to 4th Industrial Revolution training (e.g. 3D print, big data, AI, smart manufacturing) went from over 70 000 in the first half of 2013 to over 136 000 in the second half of 2017.

Despite positive improvements observed in the past years, more could be done. The first challenge in Korea will be to equip SME workers with at least basic ICT skills and close the gap with large companies. As discussed in Chapter 1, some 72% of workers in micro-firms have low problem-solving skills in technology-rich environments, a rate that declines evenly to 50% in large firms – according to PIAAC data.

Another challenge is to encourage SMEs to provide digital skills training. Today, IT-related training remains the least frequently provided training in SMEs – according to WPS data (see Figure 4.4). In a given year, professional IT education is provided only by 3% of small firms, 6% of medium-sized firms, and 10% of large firms. Similarly, general IT education is provided only by 10% of small firms, 13% of medium-sized firms, and 20% of large firms.

Another challenge is that publicly financed training programmes related to the 4th industrial revolution exist but are scant, according to several stakeholders. The demand is too high compared to the offer, and as a result there are long waiting lists to access such programmes.

Another issue is training cost. Industry 4.0 training programmes, particularly specialist training courses, are typically more expensive than more traditional courses, and public subsidies are often insufficient to cover such costs. This is partly due to the fact that training cost are linked to (and increase with) training duration, and 4th industrial revolution training programmes typically have a longer duration. For example, according to Seol (2019[18]), in the period 2013-17, the average hours of 4th-industrial-revolution-related training is 43 hours compared to less than 30 hours for other types of training. Another issue is the hourly training cost – which tends to be higher in innovative sectors where teachers are paid higher wages. For example, the hourly wage of block chain instructors is KRW 200 000-400 000, which is well above what government subsidies typically cover. New machinery and equipment facilities can be costly as well.

The Korean government already recognises the need to equip workers with the skills needed for the 4th industrial revolution. Various ministries have developed adult learning strategies that aim to achieve this objective, e.g. the MoEL with the ‘3rd basic plan for vocational skills development’, and the Ministry of Sciences and ICT with the ‘4th Master plan for Science and Technology (2018-2022)’ (Ministry of Science and ICT, 2017[7]; MoEL, 2018[19]). Social partners are also taking steps. The Economic, Social and Labor Council (ESLC) finalised a tripartite framework agreement in February 2018 on the 4th Industrial Revolution, and adult learning is part of the framework.

On top of these strategic efforts, concrete policy measures have also been put in place. For example:

-

Local lifelong learning systems are offering basic digital literacy training for vulnerable adults, such as the middle-aged and women after career breaks.

-

MoEL has allocated, since September 2019, KRW 5 billion (about EUR 4 million) to provide financial incentives to firms providing new technology training – which cover three times of current NCS unit costs.

-

In 2017, the Ministry of SMEs and Startups together with The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, have established the SMEs Programme for Smart Manufacturing. This project aims to provide financial support to help cover large scale infrastructure investments often needed for SMEs to fully engage in the digital transformation. The programme finances up to 50% of the costs of digital technology adoption (OECD, 2019[20]). The goal is to have more than 30 000 smart factories operating with the latest digital and analytical technologies by 2025. As a complement to this measure, the government will provide support to help train 100 000 skilled workers to operate fully automated manufacturing sites through various educational programmes. Some initial impact evaluation analysis shows productivity improvement signals in firms using smart factory programmes (MSS, 2019[21]).

Korea needs to put in place a broad set of measures that aims to tackle the challenges highlighted above. These include policies to:

-

Continue providing free or subsidised basic ICT training programmes, particularly to at-risk population groups. Basic ICT courses could be targeted to SME workers, or to vulnerable groups who are over-represented in SMEs (e.g. older workers; low-qualified).

-

Continue channelling financial incentives to innovative training options. For example, Korea should continue providing more generous financial incentives for training programmes in emerging industries/sectors.

-

Expand the training offer of Industry 4.0 training programmes by, for example, making these programmes more widely available and reducing waiting lists.

-

Develop new National Competency Standards (NCSs) to cover emerging sectors. Ensure that all relevant stakeholders are involved in the process in a timely manner. The process for adding new NCSs could be made shorter so NCSs are more responsive to changing needs.

References

[10] Choi, D. (2015), A study on Establishment of Quality Management System for National Competency Standards(NCS)-based VET Curriculum, Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training, Seoul, http://www.krivet.re.kr/eng/eu/ec/euABAVw.jsp?pgn=1&gk=&gv=&gn=M05-M052010314.

[3] EPF (2017), The Role of the Private Sector in VET, EPF Working Paper, https://www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/epf_the_role_of_the_private_sector_in_vet_official.pdf.

[2] Fialho, P., G. Quintini and M. Vandeweyer (2019), “Returns to different forms of job related training: Factoring in informal learning”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 231, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b21807e9-en.

[17] FKI (2014), Perceptions of employment of college graduates Workers Survey, The Federation of Korean Industries, http://www.fki.or.kr/FkiAct/Promotion/Report/View.aspx?content_id=f6b08182-ac93-4da3-960b-f86ec5cf0f94&cPage=1&search_type=3&search_keyword=%b0%ed%bf%eb.

[6] HRD Korea (2017), 35 Years of HRD Korea: Together with the Korean People toward the World, HRD Korea, http://www.hrdkorea.or.kr/design/image/eng/HRD_35years_Eng.pdf.

[14] KoreaTech HRDI (2019), Facilitation of refresher training for vocational teachers and instructors, KoreaTech Human Resources Develoment Institute.

[8] KSQA (2019), KSQA Introduction.

[7] Ministry of Science and ICT (2017), The 5th Science and Technology Foresight (2016-2040): Discovering Future Technologies to Solve Major Issues of Future Society, Korean Ministry of Science and ICT.

[19] MoEL (2018), The Employment Insurance White Paper, Korean Ministry of Employment and Labor.

[23] MoEL (2016), A Proposal for the Reform of the Vocational Competency Development Training System in preparation for the 4th Industrial Revolution.

[21] MSS (2019), Results of Performance Analysis of Smart Factory Support Project.

[12] NILE (2015), Lifelong Learning Educator in Korea, National Institute for Lifelong Education, http://cradall.org/sites/default/files/2015_Lifelong_Learning_in_Korea_Vol.2_0.pdf.

[4] OECD (2019), Adult Learning in Italy: What Role for Training Funds ?, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264311978-en.

[20] OECD (2019), Digital Innovation: Seizing Policy Opportunities, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a298dc87-en.

[1] OECD (2019), Individual Learning Accounts: Panacea or Pandora’s Box?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/203b21a8-en.

[9] OECD (2019), Investing in Youth: Korea, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4bf4a6d2-en.

[22] OECD (2019), OECD Skills Outlook 2019: Thriving in a digital world, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/df80bc12-en.

[5] OECD (2016), Getting Skills Right: Assessing and Anticipating Changing Skill Needs, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252073-en.

[11] OECD (2015), OECD Skills Strategy Diagnostic Report: Korea, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264300286-en.

[16] OECD (forthcoming), OECD Economic Survey: Korea 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[18] Seol, G. (2019), The Fourth Industrial Revolution and Workers in SMEs: Korean case, Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training (KRIVET).

[15] SkillsFuture SG (2019), TVET 2019: Open the future.

[13] Yang, J. and R. Yorozu (2015), Building a Learning Society in Japan, the Republic of Korea and Singapore, UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED564132.pdf.

The Korean Skills Quality Authority (KSQA), established in April 2015 under the umbrella of the Ministry of Employment and Labour, is the national body dedicated to quality assurance in the adult learning sector (excluding firms’ in-house training). The activities of the KSQA are five-folds: 1) training organisation assessment (accreditation); 2) training evaluation; 3) training performance assessment; 4) trainee evaluation; 5) fraud investigation.

Training organisation assessment (accreditation)

Through the training organisation assessment, KSQA provides accreditation to training providers that meet certain minimum quality standards. KSQA first checks the provider’s appropriateness, i.e. it monitors whether the training provider complies with existing regulation and assesses its financial soundness (e.g. whether it respects national and local tax legislations).

Then, KSQA carries out an evaluation19 that assesses the performance of the training provider based on a number of dimensions and provides a score (up to 100 points) that reflects overall performance. In this evaluation, KSQA assesses training outcomes (60 points) such as courses completion rates, satisfaction surveys, and trainee evaluation results.

KSQA also carries out an on-site assessment (40 points) which evaluates other organisational aspects, such as facility and equipment, trainers, and trainee management. The final score determines whether the training provider is entitled to receive the accreditation, as well as the duration of validity of such accreditation.

If the training provider receives a score inferior to 60, accreditation is rejected. Conversely, training providers that receive at least 60 points receive accreditation. The validity of such accreditation is 1, 3 or 5 years, depending on overall performance. Only accredited training providers are allowed to receive financial support from the government, and preferential support is given to best performers.

Training evaluation

After being accredited, training providers are assessed on a regular basis by KSQA. KSQA adopts a different evaluation procedure for assessing collective training (i.e. class-based; face-to-face training) and distance training.

-

Collective training: The quality of collective training is assessed using a number of criteria, including compliance with NCSs, training hours, facilities, as well as training assessment strategies. The evaluation is conducted by an evaluation committee composed of thematic experts.20 Around 30 000 collective training courses are assessed every year. The results of the assessment are displayed in HRD-net; and a report is published on an annual basis and is available to the general public.

-

Distance training: distance training includes internet-based training, smart training (e.g. delivered through virtual reality), and mail-based training – delivered by private training providers, by the national HRD consortium and by corporate universities. The quality of distance training is assessed based on a variety of criteria, such as skills development/improvement. The results of the evaluation are summarised in a final grade (A, B, C) that reflects the quality of the e-learning training provider. Better grades give training providers access to more generous government subsidies. Around 20 000 distance training courses are assessed every year by the KSQA.

Training performance assessment

The training performance assessment evaluates the performance of central and regional government VET projects, as well as the HRD Consortium, and Work-Learning Dual System. It looks for potential duplication/overlaps among training programmes and reviews the alignment of training courses with skills needs. It also selects training providers suitable to develop talent in the context of the 4th industrial revolution.

Trainee evaluation

Through the trainee evaluation, KSQA evaluates the achievement level of trainees. Among other dimensions, the trainee evaluation assesses whether the participants who completed training courses have acquired the expected skills as measured by the NCSs. The results of the trainee evaluation are used in different ways: they are directly communicated to training providers, in a view to encourage them to improve the quality of their services; they are used to help KSQA decide whether accreditation should be renewed; they are used to determine the level of government financial support.

Fraud investigation

The KSQA has a Fraud Investigation Centre that systematically investigates and prevents fraudulent practices among training providers. The Fraud Investigation Centre has different functions: i) it detects suspicious training providers, by analysing big data patterns and conducting audits/investigations; ii) it prevents fraud, by providing prevention training, as well as by disseminating casebooks, flyers and other prevention material to training providers; iii) it provides incentives to training providers to comply with rules, by integrating the results of fraud investigations into certification procedures and training evaluations.

Notes

← 1. Thus, indirectly, workers pay for their training, as their wages do not increase in line with the productivity gain by the firm.

← 2. A similar challenge is found in OECD European countries, where on average 21% of training hours are spent on compulsory training – according to the Continuing Vocational Training Survey (CVTS).

← 3. Including both in-house training and entrusted training.

← 4. Differences between Figure 4.1 and Figure 4.5 reflect the fact that the former includes all job-related training, including training initiated voluntarily by the worker, while the latter includes only training initiated by the firm. Differences may also reflect the different definitions of SME workers: in Figure 4.1 a SME worker is defined as an employee working for a firm with 250 employees or less, while in Figure 4.5 a SME worker is defined as an employee working for a firm with 100-299 employees.

← 5. Further subsidies are available for setting up learning groups and to fund staff responsible for managing these groups. Funds can be also used to provide training to CEOs and staff responsible for learning activities. The final set of subsidies allows companies to take part in peer-learning activities and share their experience of building a learning organisation.

← 6. The skill level classification employed in the Occupational Labour Force Survey at Establishment classifies the skill level by five categories with regards to work experience, educational attainment and certificates: skill level 1 refers to an occupation with no requirement for experience, diploma, and certificate; skill level 2-1 refers to an occupation that requires less than a year of experience or craftsman certificate or educational attainment of high school graduate; skill level 2-2 refers to an occupation that requires one to two years of experience or industrial engineer certificate or educational attainment of two-year college graduate; skill level 3 refers to an occupation that requires two to ten years of experience or engineer certificate or educational attainment of university graduate or master degree; skill level 4 refers to an occupation that requires more than ten years of experience or professional engineer certificate or educational attainment of doctoral degree.

← 7. Additional SAA studies are conducted on a more ad-hoc basis. For example, in 2014 the Federation of Korean Industries (FKI) conducted a survey on 800 Employees (including SMEs) to assess the skills required in the Digital Economy.

← 8. Called “enhancement training programmes”.

← 9. Various adult learning programmes are implemented by national, regional, and local governments. In the public sector, 40 Korean Polytechnic University campuses offer courses for adults and 26 universities have instituted adult learning centres. 16 Regional and 17 Industry Skills Councils are have started to deliver their own training programmes, in line with regional and industry needs. The private sector also plays an important role in delivering adult learning programmes. There are around 7 000 private training providers in Korea. Large companies (such as Samsung, LG, and Hyundai) have established their own closed employee training system. On top of traditional courses, distance learning is also expanding: the offer of cyber and open universities can be found alongside thousands of e-learning courses offered by online portals such as K-MOOC and Neulbaeum (see Chapters 2 and 3).

← 10. Since 2019, the Korean government has fully abolished government subsidies for non-job-related mandatory training, and has reduced support for job-related mandatory training from 100% to 50% of training costs. This is a step in the right direction: using the public purse to finance compulsory training risks generating large deadweight losses (i.e. financing training that would have taken place even in the absence of the subsidy), on top of representing a missed opportunity to provide workers with the skills needed to adapt to future labour market challenges.

← 11. For jobseekers’ training, the KSQA uses other indicators to assess training quality, such as employment rates after training.

← 12. Training quality is particularly hard to measure when it comes to workers’ training, as opposed to training for the unemployed, for which indicators such as employment rates, wages, employment retention period after training, can be used.

← 13. Similarly to what happens in Korea, the aggregated results are published online while the detailed results are shared with training providers.

← 14. The Learning Experience Recognition System was made institutionary possible through the revision of the law in 2017, but there have been no cases of recognition for work experience.

← 15. The ratio of NCS-based courses out of the total number of training programmes provided, is one of the criteria used to receive certification by the KSQA. For continuous assessment of training providers, KSQA requires 40% of curricula compliance with NCS.

← 16. NCSs framework is updated every three years.

← 17. For example, in the case of big data analysis (NCS), the training time is different for each unit, e.g. visualisation of big data analysis results (40 hours), building data for analysis (20 hours) and data analysis based on machine learning (80 hours).

← 18. To reflect the demand for new industries and new technologies, the Korean government launched the training programme for nurturing pioneers for the 4th Industrial Revolution in 2017. This programme defines eight training areas for the 4th Industrial Revolution, which include smart factory and robot, IoT (Internet of Things), big data and AI (Artificial Intelligence), information security, bio-chemical innovation, finance and technology, unmanned aerial vehicle, and AR (Augmented Reality) or VR (Virtual Reality) (MoEL, 2016[23]).

← 19. Organisation Competency Assessment.

← 20. Experts are called Subject Matter Experts.

This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Extracts from publications may be subject to additional disclaimers, which are set out in the complete version of the publication, available at the link provided.

https://doi.org/10.1787/7aa1c1db-en

© OECD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.