2. Multilateral development finance in context

The multilateral development system is under stress from the combined effect of successive crises, an increasingly polarised geopolitical landscape and growing challenges to the rules-based multilateral order. While multilateral development organisations channelled a large share of the international response to the COVID-19 pandemic, their ability to continue providing exceptional levels of financing is constrained by their current funding and operating models, as well as by the growing complexity and fragmentation of the multilateral architecture. Multilateral organisations are expected to help address a growing list of development challenges, including global and regional public goods, which often compete with their original mandates and stretch their capacities further. The urgent nature of these crises also risks diverting attention away from much-needed reform efforts to build a resilient multilateral development system that can support the recovery in developing countries effectively while addressing mounting global challenges.

2.1.1. The multilateral development system is a major component of the development co-operation landscape

The multilateral development system is at the heart of development co-operation. Since its inception, the multilateral development system has not ceased to expand in scope, mandate and size. The previous edition of the Multilateral Development Finance Report (OECD, 2020[1]) outlined the creation, over a 75-year period, of a constellation of United Nations (UN) agencies, funds and programmes; multilateral development banks (MDBs); and vertical funds, in response to successive crises and development challenges. Today the system encompasses more than 200 multilateral entities conducting work of a development-related nature.

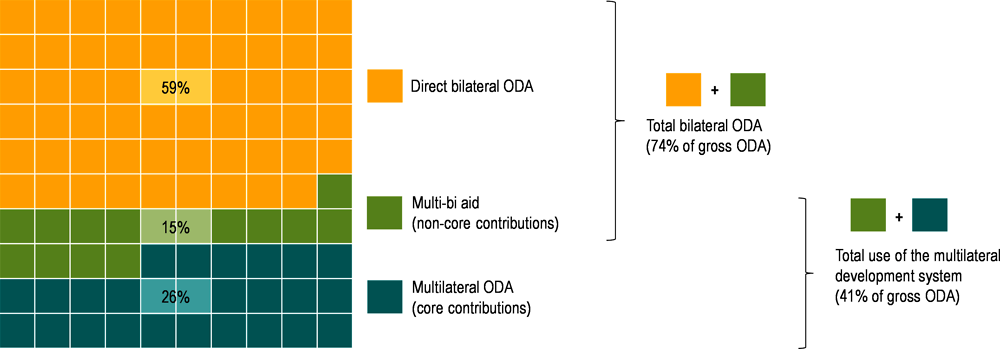

The multilateral development system channels a large and growing share of total official development assistance (ODA). The volume of unearmarked and earmarked ODA channelled through the system – i.e. the total use of the multilateral development system – amounted to USD 78.6 billion in 2020, or 41% of total ODA (Figure 2.1). This represents a three-percentage point increase since 2018 (38%). Official providers’ contributions to the multilateral development system can be divided into two types. The first, multilateral ODA, consists of core contributions that multilateral organisations can incorporate into their financial assets and allocate as they see fit, within the limits prescribed by their mandates. The second, multi-bi aid (non-core, or earmarked, contributions), corresponds to bilateral funding earmarked through multilateral development organisations for specific purposes1. While smaller in volume and share, multi-bi aid has been rising steadily over the last two decades, while the share of core contributions has remained constant.

Multilateral ODA is fundamental to the proper functioning of the multilateral development system. These core, unearmarked contributions to multilateral development organisations are a key resource for the multilateral development system. Unlike multi-bi aid, which is earmarked by donors for specific purposes, multilateral ODA can be used to finance both the development activities and the core functions of multilateral development organisations. However, the share of multilateral ODA in multilateral development organisations’ funding mix varies greatly across entities. In fact, Chapter 3 shows that some entities in the UN Development System (UNDS) receive most of their funding as non-core contributions.

The multilateral development system can have a significant multiplier effect on Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members’ multilateral contributions. Thanks to their capacity to leverage and mobilise financing from multiple sources, multilateral development organisations play a major role in financing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For example, the volume of financing provided or mobilised by multilateral development organisation (USD 193.1 billion on average between 2019 and 2020) far exceeds the volume of multilateral contributions provided by DAC members (USD 73.5 billion over the same period) (Figure 2.2). This means that, for each dollar invested by DAC members through the multilateral development system, multilateral development organisations are able to provide almost 3 dollars for sustainable development.

This multiplier effect of multilateral ODA is made possible by three sources that complement DAC members’ multilateral contributions: (i) the funding obtained from other official (non-DAC countries) and non-official (e.g. philanthropies) sources; (ii) the financing raised by multilateral development organisations from capital markets; and (iii) the amounts of private finance mobilised by the multilateral development system. The relative importance of each of these sources varies significantly across multilateral development organisations according to their business models. UNDS entities derive the majority of their funding from UN member states (although Chapter 3 shows this is gradually changing); multilateral development banks (MDBs) have the comparative advantage of being able to raise financing from capital markets and act as a catalyst for other private actors to finance development projects; and vertical funds (global financing mechanisms focusing on specific issues, such as the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria) have traditionally been able to mobilise more funding from private sector sources.

In addition to their financing function, multilateral development organisations also play a key role in facilitating policy dialogue and aid co-ordination, and providing technical assistance. Thanks to their global or regional reach, wide-ranging expertise and convening power, multilateral development organisations are able to support the global development agenda in various ways beyond financing. International financial institutions (IFIs) such as the MDBs and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) engage in regular policy dialogue with developing countries and civil society, and support policy reform, including through development policy loans or conditional lending. The convening power of multilateral development organisations also allows them to support co-ordination efforts at the country level. One example is the UN Resident Co-ordinator (UNRC) system, which aims to lead and co-ordinate the operational efforts of all UN humanitarian and development actors to help countries implement the 2030 Agenda.

In addition, multilateral organisations provide governments with tools to enhance the mobilisation and co-ordination of multiple financing sources. The World Bank and several other MDBs, for example, promote the creation of country platforms to facilitate policy co-ordination among governments of developing countries and potential financiers, including official development partners, non-traditional donors and the private sector. The UN, on the other hand, assists governments to develop and implement country-led integrated national financing frameworks, or INFFs (Box 2.1). Finally, multilateral organisations are also increasingly recognised as a source of knowledge, solutions and best practices on development and financial innovation.

Since 2015, the UN has played a leading role in implementing the holistic vision of SDG financing laid out in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA). The AAAA called for the development of INFFs to bring together all financing sources – domestic and international, public and private – to support the SDGs. Eighty-six countries are currently in the process of developing their INFFs, and more than 20 UN agencies are engaged at the country level alongside IFIs and a growing range of bilateral partners. The Inter-Agency Task Force (IATF) on Financing for Development, led by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, has developed and maintains INFF guidance materials. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is supporting governments in more than 70 countries in the design and implementation of their INFFs. Following the endorsement of the G20 Framework of voluntary support to INFFs by G20 leaders in October 2021, UNDP, UN DESA, the OECD, the European Union (EU), Italy and Sweden launched the INFF Facility, which brokers support in response to country demand for technical assistance on INFFs.

Further dialogue is required to ensure greater co-ordination with the initiatives promoted by international financial institutions (IFIs). At present, IFIs participate in INFF processes in more than 50 countries, both as members of INFF oversight committees and through their engagement in financing dialogue. They feed in technical inputs to INFF processes through SDG costing assessments, public expenditure and financial accountability processes, and public expenditure reviews. The World Bank, for example, is currently engaged in INFF processes in more than 40 countries, while the IMF is engaged in INFFs in more than 25 countries and participates alongside the EU, UNDP and UN DESA in country-focused dialogues to co-ordinate technical assistance. Other MDBs, including the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) and African Development Bank (AfDB), are engaged in INFFs in more than 30 countries. However, there is scope to increase the depth and the systematic character of this co-ordination to ensure it goes beyond light touch involvement, such as data and knowledge sharing, and that countries receive coherent and complementary advice from the different multilateral partners.

Source: UNDP (2022[3]), The State of INFF.

2.1.2. Multilateral development has become a complex and diverse ecosystem

The multilateral development system is in constant evolution, although changes to its architecture occur relatively slowly. Changes to the multilateral architecture tend to take place through incremental adjustments and additions to existing multilateral frameworks. Occasionally, however, significant changes are made to the multilateral architecture, often resulting in the creation of new multilateral entities. These can be formal institutions with their own bureaucracies and operational capacities, or financing mechanisms with no implementing capacity that rely on other multilateral development organisations to deliver their activities. The creation of the two new BRICS-led MDBs (the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, or AIIB, and the New Development Bank, or NDB) in the 2010s is an example of the former, while most vertical funds created in the 1990s and early 2000s are examples of financing mechanisms (OECD, 2020[1]).

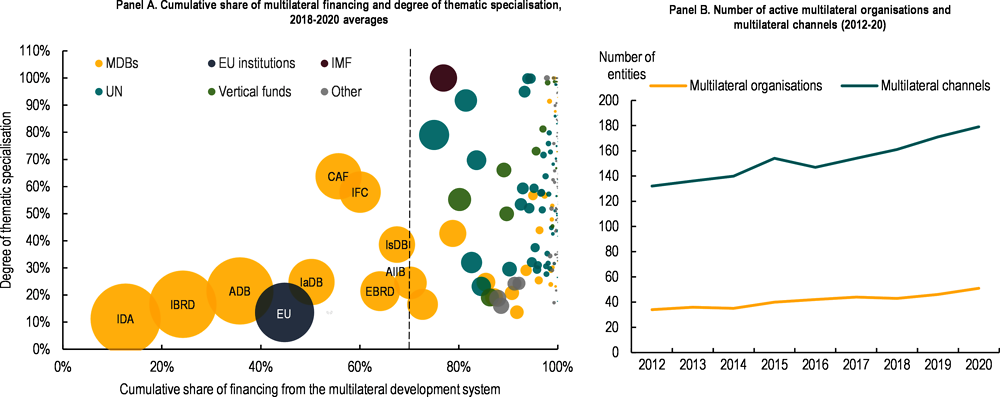

The centre of gravity of the multilateral development system remains in a handful of multilateral organisations. Ten multilateral development organisations, out of more than 200, account for 70% of the outflows from the multilateral development system (Figure 2.3, Panel A). The main MDBs are overrepresented among these “vital few”, which also include the EU institutions. While the large volume of financing of the main MDBs denotes their influence in the multilateral development finance landscape, many multilateral development organisations also play important roles in other areas, such as norms-setting, policy analysis, or technical assistance, which are not adequately reflected by their financing volume.

The multilateral development system also includes a multitude of smaller and more specialised entities. UN funds and programmes, UN agencies and vertical funds account for a large share of the entities within the remaining 30% of multilateral outflows. This part of the system is characterised by greater fragmentation, featuring entities with smaller portfolios and greater thematic specialisation and which often channel funds earmarked by bilateral providers. The analysis shows that the number of active multilateral channels receiving earmarked funds from bilateral partners is growing steadily, and more quickly than the number of multilateral organisations providing multilateral outflows (Figure 2.3, Panel B). If this fragmentation continues, it risks undermining systemic coherence and accountability in the long run, especially if new ad hoc structures are created and superimposed on the pre-existing multilateral architecture.

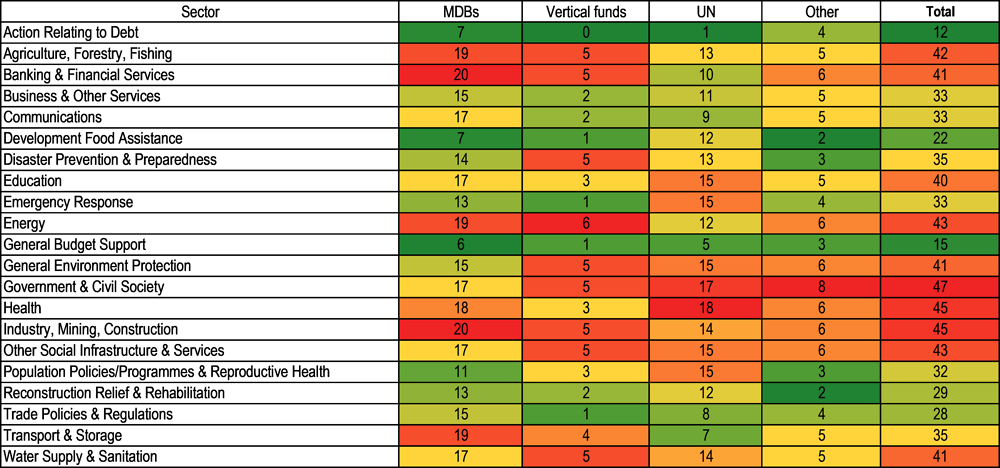

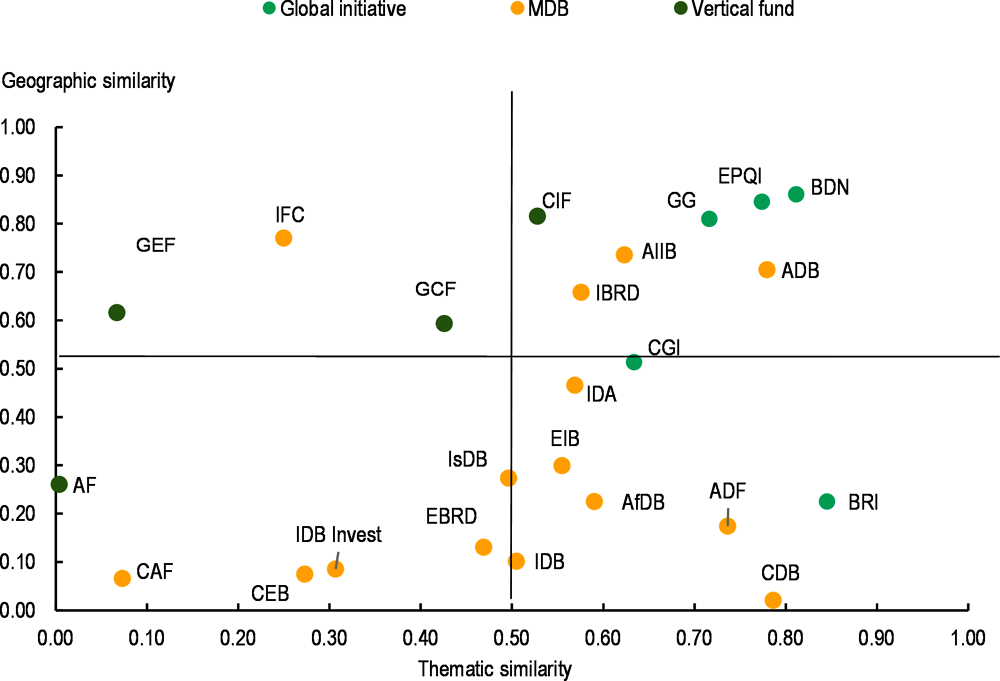

The large number of organisations that constitute the multilateral development system has resulted in a multifaceted and versatile architecture. Rather than a monolithic structure, the multilateral development system is an intricate institutional patchwork of entities with diverse constituencies (global, regional or South-South), geographic scope (regional or global), thematic focus (single-focus or wide-ranging), financing instruments (grants, concessional and non-concessional loans, equity, guarantees) and operational models (banks, funds, agencies). A closer look at the aid portfolios of the main multilateral development organisations reveals interesting patterns across the different types of multilateral institutions (Figure 2.4). The portfolios of the MDBs, although originally focused on infrastructure financing, now span multiple sectors. Due to this generalist profile, the portfolio of these institutions are quite similar thematically. Vertical funds, on the other hand, which were created to address specific development challenges, tend to have a very narrow thematic focus although some present high thematic similarity, like the Global Climate Fund (GCF) and Climate Investment Funds (CIF). UNDS entities are also highly specialised thematically, although their portfolios sometimes overlap with those of other UNDS entities or vertical funds (e.g. the United Nations Environment Programme, UNEP, and the Global Environment Facility, GEF; or the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, FAO, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development, IFAD).

The complexity of the multilateral architecture obscures the division of labour across multilateral organisations, as well as between multilateral and bilateral aid. The institutional and operational diversity observed among multilateral organisations offers versatility and allows them to make meaningful contributions in multiple areas of the global development agenda. However, the fact that the multilateral architecture is becoming increasingly crowded also makes it difficult to obtain a clear understanding of the division of roles and potential overlaps across multilateral development organisations’ portfolios. For example, a total of 18 entities from the UNDS are active in the health sector (Figure 2.5). In addition, 18 MDBs, 3 vertical funds and 6 other multilateral entities are also active in the health sector, making it one of the most crowded sectors in the multilateral development system. It should be noted that the number of active entities does not necessarily reflect the amount of funding available in each thematic area, meaning that some areas can have several entities competing for a small piece of the pie. As discussed in a recent analysis (OECD, 2022[4]), this complexity is even greater when taking into account both multilateral and bilateral aid portfolios, making it difficult to identify areas of complementarity or duplication.

The complex multilateral architecture contributes to the lack of collective governance and accountability of the multilateral development system. While multilateral organisations are called on to play an increasingly central role to help address development challenges requiring a coherent global response, there is currently no governance or accountability mechanism in place to monitor and assess the system’s overall coherence or performance. Over time, the growing expansion and fragmentation in the multilateral system is likely to add to this challenge by further diluting responsibility across a constellation of entities with their own governance frameworks.

Safeguarding the coherence of the multilateral architecture is key to ensuring multilateral effectiveness. The previous edition of the Multilateral Development Finance report (OECD, 2020[1]) pointed out that successive crises could either lead to a consolidation of the system or exacerbate the trend towards increasing fragmentation. The recent creation of new multilateral channels, such as the Pandemic Preparedness and Response Fund (PPR) hosted by the World Bank and the UN-led COVID-19 Multi-Partner Trust Fund, suggests that the system continues to adapt to new challenges by superimposing new entities on top of the existing architecture, rather than prompting a profound reform of the system. From the perspective of developing countries, while a diverse offer could be useful to ensure healthy competition, raise multilateral standards and incentivise multilateral organisations to pay greater attention to the demands and needs of developing countries, it can also increase their transaction costs due to the need to engage with many stakeholders. For example, the previous edition of this report showed that there are on average 20 active multilateral entities in each ODA-eligible developing country.

Ultimately, the multilateral architecture evolves in reaction to the global context and through successive cycles of adaptation. The next two sections in this chapter examine how the challenging global context is influencing and reshaping the multilateral development system (Section 2.2.), and how the system is constantly attempting to adapt to shifting conditions and growing expectations through constant, but too often partial, reform efforts (Section 2.3.).

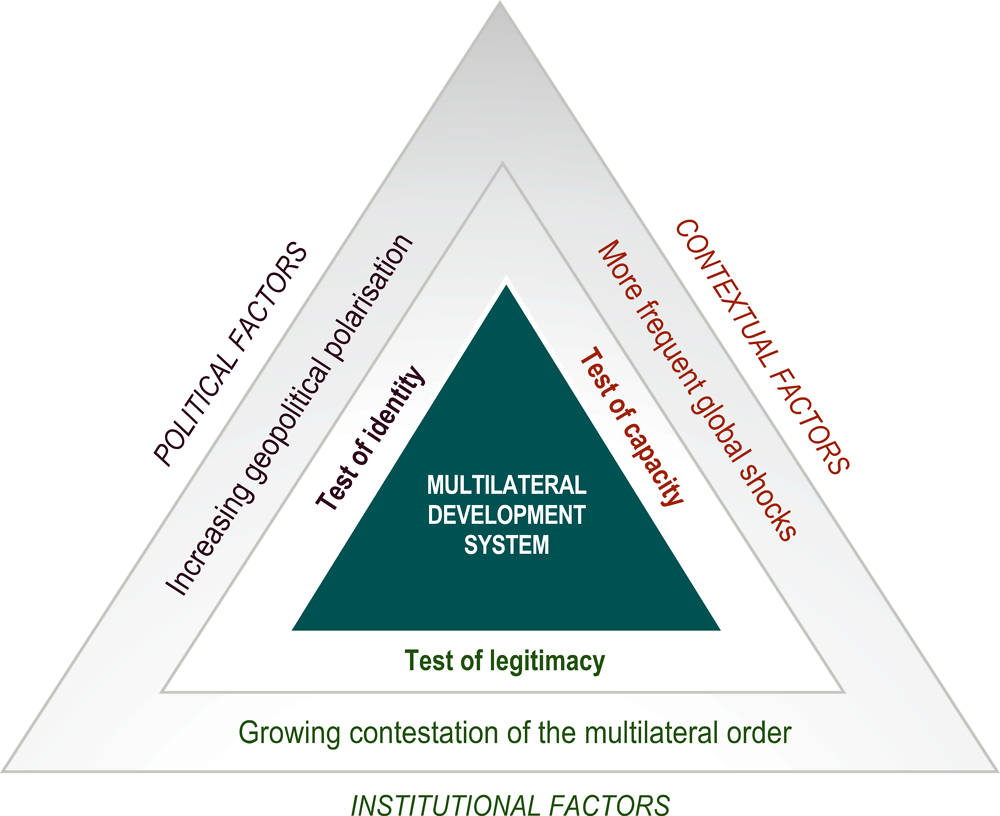

A combination of three forces (contextual, institutional and political) is putting the multilateral development system to the test (Figure 2.6). First, successive crises are stretching multilateral resources across an ever-increasing list of development priorities and testing its capacity to remain relevant in a more shock-prone world. Second, growing geopolitical polarisation is affecting the multilateral space, and may result in tensions between diverging and competing values and priorities. Third, the legitimacy of the rules-based multilateral order inherited from the period following the Second World War is increasingly challenged, facing mounting contestation and criticism. Failure to adjust to these forces could put the multilateral development system on the verge of a triple crisis of capacity, legitimacy and identity.

2.2.1. A more shock-prone world tests the relevance and capacity of multilateral models

Multilateral organisations are expected to help tackle an ever-increasing number of humanitarian and development challenges. The world is facing the most challenging confluence of crises in contemporary history, jeopardising decades of progress in the fight against poverty, gender equality, access to quality health and education and other global goals. As described in the Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2023 (OECD, 2022[5]), the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a multidimensional crisis, taking the form of cascading and mutually reinforcing waves. The health emergency, which caused the loss of millions of lives globally, also spawned a major economic crisis, which in turn prompted a reversal of hard-won development gains, including in the fight against poverty. The social dimension of the crisis is now being compounded by the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the threat of new global shocks due to soaring energy and food prices.

The COVID-19 crisis stretched the capacity of the multilateral development system. The pandemic represented a challenge of unprecedented proportions since the creation of the multilateral development system in the aftermath of the Second World War. Thanks to their global reach, multilateral organisations played a key role in the initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic, channelling record-levels of resources to address the immediate impact of the crisis in developing countries (as discussed further in Chapters 3 and 4). However, the COVID-19 crisis also exposed the limitations of the multilateral development system. Two independent reviews of the international response to the COVID-19 crisis conducted in 2021 found that, at the onset of the crisis, the multilateral system was not adequately mandated, prepared or equipped to prevent or respond to the risk of pandemics (G20 HLIP, 2021[6]) (Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, 2021[7]). In order to respond to the increased financing needs of developing countries, some organisations had to repurpose and frontload their available financing, quickly exhausting their available resources. This was the case for the World Bank Group, for example, which had to bring forward by one year the replenishment date of its concessional window, the International Development Association (IDA). While the G20 has now launched a new vertical fund (PPR) with funding of USD 1.3 billion to help fill financing gaps in pandemic preparedness and response, this falls far short of the estimated funding gap of USD 10 billion. In addition, proposed reforms to enable surge capacity and improved co-ordination between key actors are yet to be implemented.

The knock-on effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are putting an additional strain on multilateral development finance. The war in Ukraine has ended all hope of a prompt recovery from the COVID-19 crisis in developing countries and is exacerbating its impact. The war, which produced 7.5 million refugees in its first six months and could push an additional 40 million people into extreme poverty globally (Center for Global Development, 2022[8]), is resulting in increased financing needs for humanitarian and development-related interventions (OECD, 2022[9]). Due to the weight of Russia and Ukraine as exporters of key commodities, the war has also aggravated global inflationary pressures. This puts official development finance under increased pressure by simultaneously increasing the needs of the most vulnerable while reducing the purchasing power of ODA. The World Food Programme (WFP), for example, estimates that the cost of its operations has increased by a staggering 44% since 2019 due to the combined impact of the successive crises and the rise of global inflation (WFP, 2022[10]). Several multilateral development organisations were also directly affected by the international sanctions imposed against Russia. The World Bank and the AIIB, for example, announced that they were putting on hold all activities related to Russia and Belarus (Subacchi, 2022[11]). The New Development Bank (NDB), however, arguably suffered the largest impact. In March 2022, Fitch downgraded its rating from stable to negative, citing both the bank’s exposure to Russia (13% of its loans as of end 2021) and the risk inherent in having the country as a large shareholder (19% of NDB’s capital) (Fitch Ratings, 2022[12]).

Multilateral development finance is called on to play an increasingly important role in the provision of global and regional public goods. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a stark reminder of the disastrous impact of global shocks, and the need for joint approaches to prevent and address them. Due to their intrinsic nature, based on overarching principles of collective action and cross-border collaboration, multilateral organisations are often presented as ideally positioned to support the provision of global and regional public goods in areas such as health, climate, biodiversity, financial stability, and peace. Yet, many of the legacy multilateral institutions, such as the Bretton Woods institutions (World Bank and International Monetary Fund), did not have the provision of global and regional public goods in their original mandates. Hence, while multilateral organisations may indeed have the potential to be an effective conduit to support the provision of public goods, these institutions are not necessary currently structured, tooled or financed in a way that allows them to deliver on this agenda while continuing to fulfil their original mission. In the absence of a global governance framework for the provision of global and regional public goods, the division of labour and the roles of different multilateral entities in this area also remain unclear and risk adding to the complexity of the multilateral architecture.

The prospect of new and recurrent global shocks will also require the multilateral development system to step up its contribution to the fight against poverty and inequality. The pandemic and the war in Ukraine have put an end to the two decades of decrease in extreme poverty and set back progress to end global poverty. Moreover, the successive crises have also increased cross-country and within-country inequalities, with developing countries often bearing the brunt of impacts. For example, recent analysis shows that low-income countries were among the hardest hit by the rise in extreme poverty (World Bank Group, 2021[13]). At the country level, the impacts of successive crises are disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable, and exacerbating inequalities – including gender based – in income, and in access to employment, health care, education and housing. As discussed in Chapter 4, sustained multilateral support to the fight against poverty and inequality will be key both to support the recovery from recent crises in developing countries and to ensure their resilience to future ones. This entails increasing multilateral organisations’ focus on poverty and inequality within the scope of their existing mandates and areas of expertise. For MDBs, this could be achieved through increased investments in the development of social protection systems, for example.

Maintaining the countercyclical role of multilateral development finance in an era of global shocks will require substantial improvements to current multilateral models. Historically, multilateral development organisations have always provided countercyclical support to help developing countries cope with the impact of crises (see Chapter 4). The entry into a more shock-prone world raises a serious challenge of ensuring that the multilateral development system retains sufficient surge capacity to respond to more frequent shocks. Recent efforts to increase the financial capacity of multilateral development organisations, further described in Chapter 3, are heading in this direction. Nevertheless, further reflection is needed on the role of multilateral development finance in a world increasingly prone to global adverse shocks (Box 2.2).

Multilateral organisations have been on the front line in the international response to major crises. The COVID-19 crisis has confirmed that MDBs are well positioned to support developing countries in troubled times thanks to their ability to tap into capital markets when many countries lose their access to finance, or experience rising borrowing costs. The demand for multilateral support is likely to remain elevated as the risk of adverse shocks increases due to a combination of new and emerging threats. These include the risk of new pandemic outbreaks, the rise of global poverty and inequality (including gender-based), the spike in food and energy prices, and the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.

However, heightened uncertainty and financial instability resulting from a more shock-prone world pose new challenges to multilateral action. At the height of the COVID-19 crisis, the large and growing number of developing countries facing balance of payment issues raised questions about the role of multilateral development finance in times of crises. The main MDBs, for example, declined to participate in the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) spearheaded by the G20, arguing the need to preserve their triple-A credit rating. Instead, MDBs chose to provide fresh financing to their client countries by frontloading resources and repurposing parts of their existing portfolios. More recently, the leaders of some developing countries have called on the G20 to agree on a more ambitious debt service suspension initiative including MDB loans to low-income countries (Government of Barbados, 2022[14]).

Multilateral organisations have begun integrating developing countries’ heightened financial risk into their operational policies. A significant share of multilateral development finance is provided to developing countries as loans, raising questions over its role to support countries facing financial liquidity or solvency issues. A key challenge is the need to reconcile the seemingly contradictory objectives of responding to countries financing needs generated by successive crises in the short term while ensuring countries’ debt sustainability in the longer term. In 2017, the G20 devised a set of operational guidelines for sustainable borrowing (G20, 2017[16]), as well as a set of principles for co-ordination between the IMF and the MDBs for countries requesting financing while facing macroeconomic vulnerabilities (G20, 2017[17]). The World Bank and the African Development Bank have also developed new sustainable borrowing policies to ensure their lending activities take the debt profile of developing countries better into account (World Bank Group, 2020[18]) (African Development Bank, 2022[19]). While very timely, these new policies need good co-ordination to ensure, for example, that their compliance mechanisms are not impaired by a race to the bottom among multilateral and bilateral lenders.

2.2.2. Geopolitical polarisation could generate tensions in the multilateral development system between competing values and priorities

The shift towards a multipolar world marks the return of great power rivalry in international relations. The world has experienced a significant transformation in the last three decades, going from a geopolitical landscape dominated by a hegemonic power to a multipolar world characterised by growing technological, economic and political competition. In recent years, this rivalry has taken the form of trade disputes and antagonistic rhetoric on topics ranging from human rights to global governance. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has increased the impression of a growing divide between competing blocs. As a result of the war, the Geopolitical Risk Index (GRI) reached its highest level in almost two decades in the first semester of 2022 (Caldara, Dario and Matteo Iacoviello, 2022[20]).

The multilateral development system is not immune to the geopolitical turmoil. Tensions in the geopolitical space have been quick to transfer to the multilateral development system. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, the World Health Organisation (WHO) was at the centre of a controversy, with the government of the United States publicly criticising the organisation for being too slow to respond to the threat, and too trusting of The People’s Republic of China. The previous edition of the Multilateral Development Finance Report (OECD, 2020[1]) discussed some of the immediate implications of this dispute, including the announcement by the United States – then the top funder of the WHO – of its decision to withdraw from, and cut all funding to, the organisation.

The emergence of competing global initiatives in the development co-operation landscape raises concerns about their impact on multilateral development finance (Table 2.1). Launched in 2013, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was the first multinational infrastructure initiative since the 1948 Marshall Plan to draw global attention (E3G, 2022[21]). It was followed in 2016 by Japan’s Expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (EPQI), and in 2019 by the trilateral Blue Dot Network (BDN) founded by Australia, Japan, and the United States, initiatives that fit under the umbrella of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific. More recently, the COVID-19 crisis and COP26 have triggered new announcements of global initiatives, including the US and G7-led Build Back Better World (B3W), announced in 2021; the EU’s Global Gateway (GG), launched in 2021; and the Global Development Initiative (GDI), unveiled by China in 2022. While mostly relying on bilateral engagement, these global initiatives interface and collaborate with multilateral development organisations, extending the growing geopolitical tensions and some of its associated risks to the multilateral development system (Box 2.3).

Recent years have seen a proliferation of global values-based initiatives in the development co-operation landscape. These initiatives come in a variety of formats, but share a strong focus on infrastructure, as well as mandates that crossover between development, economic diplomacy and geostrategic influence.

Global infrastructure initiatives offer a unique opportunity to fill the unmet infrastructure financing needs of developing countries but present some risks for the multilateral development system. With the global infrastructure financing gap estimated at USD 15 trillion to 2040 (G20, 2022[29]), new donor commitments in this area are welcome, especially at a time of heavy budget constraints in both donor and recipient countries. In theory, the potential for collaboration among these global infrastructure initiatives and multilateral organisations is promising. It could: (i) help leverage greater synergies and complementarities between bilateral and multilateral programmes; (ii) allow sound multilateral lending policies and practices to influence bilateral ones; and (iii) raise standards through healthy competition. Yet, the proliferation of competing initiatives also poses three key challenges to the multilateral development system:

1. Fragmentation: the divergence of values promoted by these initiatives risks pulling the multilateral development system in different directions. While the BRI model favours low-cost, turn-key, infrastructure projects and claims non-interference in the internal affairs of partner countries, the B3W, EPQI, and BDN share a commitment to principles of transparency, good governance, economic viability, and alignment with international standards (OECD, 2022[30]). Implementing modalities are another source of divergence: in contrast to BRI’s strong reliance on China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs), B3W promotes a model based on the use of official finance to mobilise private capital. Ultimately, there is a risk that competing donor values and priorities – rather than actual development needs – will increasingly determine the investment decisions and modalities of individual multilateral organisations.

2. Duplication and gaps: due to their strong focus on infrastructure, the global initiatives compete in a field traditionally dominated by the MDBs. In fact, a portfolio similarity analysis of the major global initiatives points to high levels of thematic and geographic similarity between their portfolios and those of the main MDBs (Figure 2.8). If MDBs and global initiatives focus on the same areas that generate higher investment and political returns (e.g. economic infrastructure in middle-income countries), this could ultimately result in duplications and financing gaps, and other less profitable geographic and thematic areas could be left behind. In the long term, the proliferation of global initiatives could also require costly and lengthy co-ordination among a multitude of government agencies and multilateral organisations (European Parliament, 2021[31]).

3. Funding: the funding modalities of the main global initiatives remain unclear. Since its inception, the BRI has drawn criticism for its opaque project-financing model, but more recent initiatives such as B3W are also ambiguous about the source of their funding, and whether it is additional or repurposed from existing aid portfolios. One potential threat to the existing system is that these global initiatives could end up diverting resources from the multilateral development system if they encourage bilateral providers to deliver infrastructure financing through bilateral channels rather than through contributions to the MDBs, which have traditionally been the main source of official development finance in this area (Kenny and Morris, 2022[32]).

2.2.3. Multilateral approaches and institutions are increasingly contested

In the years before the COVID-19 pandemic, multilateralism had become the object of mounting criticism. The decade of the 2010s saw growing disparagement against the rules-based multilateral order, in what has often been depicted as a ‘crisis of multilateralism’. This situation, stemming in part from a certain disillusionment with globalisation – and its political exploitation by some governments – was perhaps best illustrated by the return of unilateralism and protectionism in international affairs. As geopolitical tensions transferred to the global governance and trading systems, supranational institutions were often used as scapegoats for failing to deliver inclusive economic prosperity. In reaction to increasingly vocal criticism of the rules-based multilateral order, in 2017 several middle powers, led by France and Germany, launched an Alliance for Multilateralism with the aim of defending the importance of multilateral solutions to confront global challenges.

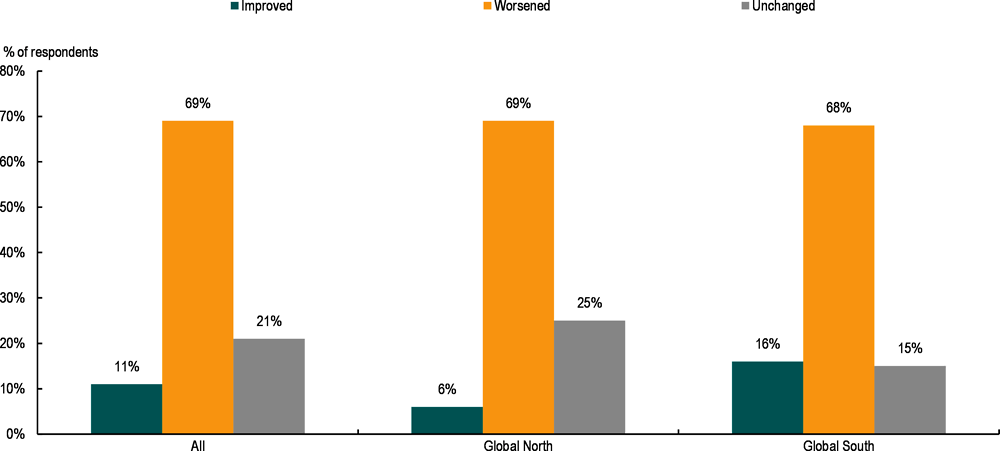

Despite growing recognition of the need for effective multilateralism, public perception of the multilateral system has worsened globally. In a recent survey involving 250 participants from academia, government, multilateral organisations and the private sector, the overwhelming majority of respondents (81%) stated that the need for effective multilateralism has increased over the last two decades (Brookings, 2021[34]). However, respondents perceived the current multilateral system to be relatively ineffective (4.7/10) and a large majority (69%) believed its effectiveness had worsened over the last two decades – a perception shared by respondents from both developed and developing countries (Figure 2.9). These results should however not be interpreted as implying lesser effectiveness from multilateral aid channels compared to bilateral ones. In fact, several studies suggest that multilateral organisations tend to perform well in comparison with bilateral development partners (Custer et al., 2021[35]) (Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation, 2018[36]).

Perceptions of multilateral effectiveness vary across the different areas of the global development agenda. According to the above-mentioned survey, gender equality is one of the areas in which multilateral effectiveness was deemed to be the lowest, followed by climate and environment. On the other hand, perceptions of multilateral effectiveness seemed to be more positive on topics such as global poverty and development, even though there was no domain in which a majority of respondents believed the multilateral system was working even somewhat effectively.

During the COVID-19 crisis, the multilateral system came under heavy fire for its incapacity to help avert the pandemic. Multilateral institutions attracted significant criticism for failing to muster the broad-based co-ordination required to contain the spread of COVID-19 and its evolution into a pandemic. As explained above, the WHO was criticised by some of its member states for its poor handling of the crisis. The episodes of vaccine nationalism observed in subsequent years further eroded the trust in multilateral approaches. For example, many high-income countries (and some upper-middle income countries, like Russia) opted out of the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) equitable distribution scheme and instead engaged in bilateral agreements or implemented export bans. This allowed them to hoard enough vaccine doses to vaccinate their population several times over while poorer countries were unable to vaccinate the most vulnerable among their citizens. It is now widely acknowledged that the largely uncoordinated purchase of vaccine doses hindered international efforts to support developing countries’ access to vaccines through the COVAX facility (WHO, 2021[37]).

Concerns about multilateral organisations’ lack of representativeness and efficiency are feeding the mistrust in the multilateral system. A common criticism of the current multilateral order is that the governance of legacy multilateral institutions is outdated, not sufficiently inclusive, and reflects the power balance that prevailed in the aftermath of the Second World War. This has led to the creation of new multilateral institutions, such as the AIIB and the NDB, founded and led by emerging countries. In recent years, however, some legacy multilateral organisations have also attracted criticism from former champions of the multilateral system for failing to demonstrate value for money. In rarer cases, some institutions have been exposed for failures in their financial practices and management, which often end up tarnishing the reputation of the multilateral system as a whole. The most recent example is the financial scandal involving an alleged misuse of funds by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS), which led to the resignation of its Executive Director in May 2022 (UNOPS, 2022[38]) and prompted some donors to freeze their contributions to the United Nations.

Without a course correction, growing scepticism over multilateral approaches risks undermining the willingness of national governments to continue supporting multilateral solutions and institutions. Failure to acknowledge and confront the system’s shortcomings and excesses could trigger a crisis of legitimacy of the multilateral system, putting at risk its resilience and capacity to contribute to the global development agenda. Even in normal times, multilateral approaches involve difficult trade-offs for national governments, such as partial renouncement of their sovereignty, as well as costly and time-consuming co-ordination with other stakeholders. The current economic situation, which adds pressure on donors’ ODA budgets, will likely translate into greater donor scrutiny and demands for accountability and clarity on the results and returns of their multilateral contributions. In this context, the capacity of multilateral organisations to demonstrate how they add value to bilateral aid will be critical to ensure strong and durable support from donors.

The new global context calls for reassessing the adequacy of the current multilateral architecture and governance. Multilateral reform refers to the introduction of formal changes in the architecture, mandate, funding modalities, operational model, financial capacity and ways of working of multilateral organisations with a view to improving their effectiveness or efficiency. Since its inception in 1945, the multilateral development system has mostly adapted to the shifting environment by adding new entities to the existing multilateral architecture inherited from the Second World War. Examples include the creation of vertical funds in the 1990s and early 2000s, driven by increased attention paid to global challenges; and the establishment of the AIIB and NDB in the 2010s, reflecting the increasing weight of emerging countries in the global economy. In contrast, there have been rarer attempts at deepening multilateral co-operation or at consolidating and rationalising the multilateral aid architecture.

2.3.1. Recent crises have drawn attention on the need to adequately resource the multilateral development system, but other aspects of multilateral reform have lagged behind

Recent crises have revealed the importance of a well-resourced multilateral system to address global challenges. The triple crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the threat of climate change has exposed some key shortcomings of the multilateral development system, and underlined the need to better equip its organisations. For example, despite the significant contribution they made to the COVID-19 crisis response in developing countries, the volumes extended by multilateral organisations at the height of the crisis were often deemed insufficient to meet the magnitude of the challenge faced by developing countries, leading to renewed calls for scaling up multilateral development finance. Chapter 3 describes the ongoing efforts to do so by multilateral stakeholders, such as the creation of new multilateral financing mechanisms, the launch of new funding appeals, and calls for replenishment of concessional windows. It also examines initiatives such as the recent discussions on the optimisation of MDBs’ balance sheets and the commitment by the G20 to re-channel USD 100 billion in IMF Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to developing countries through multilateral channels.

While efforts to scale up multilateral development finance are laudable, the focus on emergency response during crises may be at the expense of broader multilateral reform. Faced with the need to frontload resources to address multidimensional crises, multilateral stakeholders have focused a great deal of their efforts since 2020 on maximising the contribution of the multilateral development system to the COVID-19 crisis response in developing countries. As described in Chapter 4, this resulted in a record volume of financing extended by the multilateral development system in 2020. However, the emergency generated by the successive crises also diverted attention away from other key parts of the multilateral reform agenda.

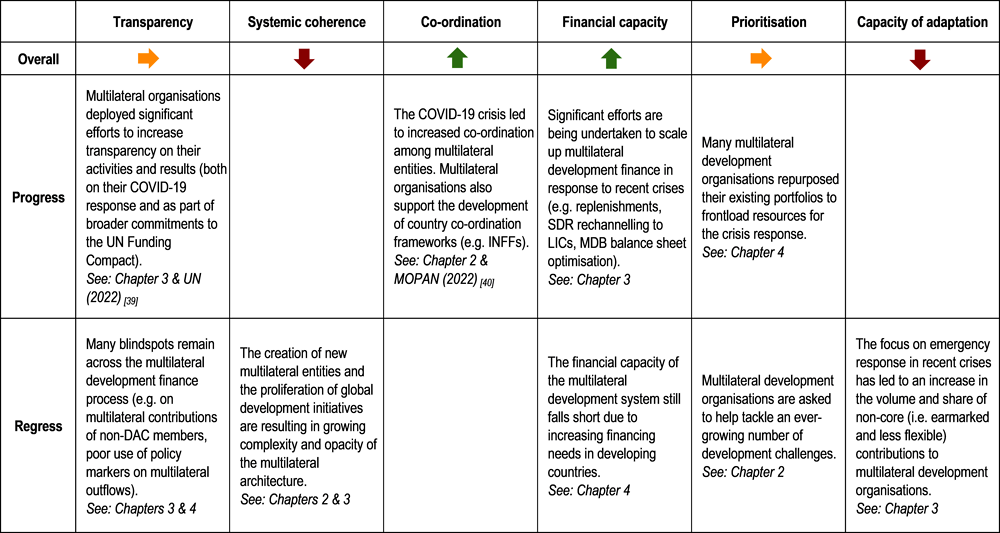

Progress has been uneven across the six building blocks of multilateral reform. The previous edition of this report proposed three key reform areas and six building blocks to adapt multilateral development finance to 21st century development challenges (OECD, 2020[1]). A review of progress on ongoing reform efforts reveals a mixed picture (Figure 2.10). While greater attention has been drawn to the need to scale up multilateral development finance, some parts of the reform agenda appear to have lost steam, and others have been set back. In particular, the focus on emergency response seems to be at the expense of reforms to clarify the multilateral architecture (coherence building block) or increasing investments in the core functions of the system to build resilience in the face of future crises (capacity of adaptation).

Learning the lessons from the multilateral response to recent crises is necessary to ensure a strong contribution of the multilateral development system to the challenges of the recovery. Important lessons can be drawn from the success achieved in some key areas of multilateral reform, such as the scaling up of the financial capacity of multilateral organisations (further examined in Chapter 3) or the improvements observed in the co-ordination among multilateral stakeholders during the COVID-19 crisis, which have been analysed in a recent MOPAN study (Box 2.4). Equally important will be to look at those areas of multilateral reform in which progress has been slow to materialise, but which hold significant potential to increase multilateral effectiveness. This is the case for reform efforts to bring greater transparency to multilateral development finance, and to clarify the mandates of, and division of labour among, multilateral development organisations.

COVID-19 has highlighted the importance of co-ordination among multilateral organisations as they seek to address the multidimensional impacts of global challenges. Co-ordination entailed both scaling-up existing co-ordination activities and convening new fora and partnerships to address the diverse challenges and impacts of the pandemic. In general, these activities promoted greater policy and operational coherence as well as joint programming from multilateral organisations in responding to COVID-19.

UNDS entities scaled up existing co-ordination mechanisms through three global frameworks addressing the health, socioeconomic and humanitarian impacts of the pandemic: the WHO’s Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan (SPRP), the UN Framework for the Socioeconomic Response to COVID-19 and the Global Humanitarian Response Plan (GHRP). These frameworks leveraged existing global policy platforms, such as the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) and the UNSDG, and they were implemented in countries by the Resident Coordinator System, humanitarian teams and WHO country representatives. The MDBs co-ordinated themselves alongside the WHO and IMF to ensure that the support provided aligned with the WHO’s SPRP. Partnerships with regional organisations such as the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and Africa CDC, and UN agencies such as WHO and UNICEF, played an important role in MDBs’ capacity to reach beneficiaries and address health impacts.

New partnerships and co-ordination fora were convened to address the diverse challenges posed by COVID-19. The Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), for example, brought diverse multilateral organisations together to promote the accelerated development, scaled-up production and equitable delivery of counter measures, including vaccines, diagnostics and therapeutics. As a platform for technical and strategic dialogue, ACT-A enabled organisations to align their operations around a limited number of common objectives without having to create a formal co-ordination body, which was not feasible during an emergency.

Although co-ordination among UN entities, MDBs and the IMF was scaled-up to respond to the pandemic, important barriers limit joint planning and programming. Despite the increase in coordination, UN, MDB and IMF operations still tend to be planned and implemented in parallel. For example, UN Socioeconomic Response Plans (SERPs) made an important contribution to promoting inter-agency co-ordination; however, evidence of operational coherence and joint programming with MDB partners was more limited. Similarly, the UN tends not to be involved directly in MDB-IMF co-ordination for development policy operations. Barriers to deeper co-ordination stem partly from differences in business models, fiduciary policies and financial instruments. Furthermore, UN entities, MDBs and the IMF each tend to work with different partners and have different entry points in working with national governments.

Fragmentation in resource mobilisation contributed to competition among multilateral organisations, worked against joint programming, and undermined the achievement of collective outcomes. Given the limited flexible funds available to support an emergency response, new resource mobilisation mechanisms were designed, including the Solidarity Response Fund (SRF) and the Response and Recovery MPTF. These funds competed against multiple individual agency appeals. For example, the GHRP and ACT-A helped promote policy and planning coherence, but did not consolidate resource mobilisation, with partners launching their own appeals. Furthermore, there has been limited progress in diversifying resource mobilisation away from a small group of traditional donors who themselves faced socioeconomic impacts from the crisis. As a result, many pooled funds and appeals remained considerably underfunded, including those meant to help scale joint programming.

Source: (MOPAN, 2022[40]).

2.3.2. There are tensions and trade-offs between the various objectives of multilateral reform

In the years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns over the adequacy of current multilateral frameworks had already spurred several reform drives, with the most recent being the UN Funding Compact and the World Bank Trust Fund reform (OECD, 2020[1]). The UN Funding Compact, launched by the UN Secretary-General in 2019, aims to address the deteriorating quality of funding received by UN entities, as well as the growing fragmentation of the UNDS. In return, the UN committed to increasing transparency and accountability over their expenditure and results. The World Bank, on the other hand, has been engaged in a series of reforms to enhance the management of its trust funds since 2001. The latest phase of this reform, which started in 2017, aims to reduce the fragmentation of its portfolio of trust funds and financial intermediary funds (FIFs), and align them with the organisation’s priorities.

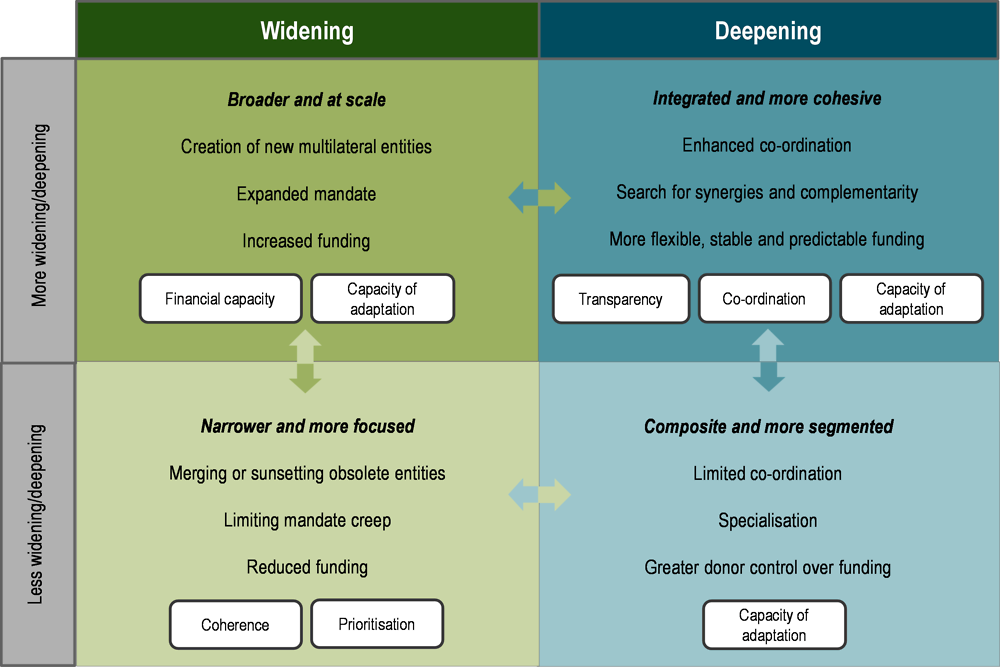

Due to the complexity of undertaking multilateral reforms, the evolution of the system to date has been characterised by continuous expansion and fragmentation rather than integration and consolidation. While system-wide reforms, such as the UN Funding Compact, are necessary, they are extremely difficult to carry out in practice due to pervasive political, economic and bureaucratic rigidities. To get round this, multilateral stakeholders tend to use their influence, leverage and agency to advance smaller ad hoc solutions, often leading to a piecemeal reform approach and resulting in a further expansion and fragmentation of the multilateral development system (Figure 2.11). Meanwhile, efforts to deepen the integration and co-operation among multilateral stakeholders have largely lagged behind. The slow pace of reform observed to date contrasts with growing calls to retool the multilateral development system. For example, during the 2022 UN General Assembly, global climate leaders called for an overhaul of the multilateral financial architecture, pushing in for a rethink of the roles of international financial institutions (IFIs) established as part of the Bretton Woods agreement to ensure their fitness for purpose in the 21st century (Financial Times, 2022[41]).

There are constant tensions and trade-offs between the short and long-term objectives of multilateral reform. The stalemate often observed in multilateral reform stems partly from the fact that, far from being a straightforward path, reforms often involve prioritising between multiple contradictory priorities and interests, including between short and long-term objectives. For example, the COVID-19 crisis showed that efforts to rapidly scale up multilateral development finance (financial capacity building block in Figure 2.11) in response to new emergencies often conflict with efforts to consolidate and rationalise the multilateral development system (systemic coherence). Similarly, the creation of new multilateral entities, which may help the system adapt to face new challenges, appears at odds with calls to limit the ever-expanding mandates of the multilateral development system (prioritisation) and can make co-ordination more difficult by increasing the fragmentation of the system.

In some cases, consensus on the objective of multilateral reform may hide discrepancies in the best approach to achieve it. For instance, while all multilateral stakeholders may agree on the need to make the system more resilient to future crises (capacity of adaptation), this objective can be pursued through multiple – and sometimes contradictory – approaches, such as: (i) expanding the mandate, funding and architecture of the system (widening); (ii) providing flexible (e.g. core) funding to multilateral development organisations to enable them to repurpose their existing portfolios in case of emergency (deepening); or (iii) opting for funding modalities that allow for greater donor control (e.g. non-core or earmarked contributions) to ensure alignment of multilateral portfolios with donors’ shifting priorities.

Looking forward, the three forces in the global context described earlier in the chapter may further complicate the pursuit of multilateral reform. First, as already observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, more frequent crises are likely to increase the short-term focus of policymakers on emergency response at the expense of longer-term investments to strengthen the system, and the increased financing needs from successive shocks risk translating into further expansion of the multilateral system, resulting in a more complex architecture. Second, the shift to a more polarised geopolitical order makes it ever more difficult to achieve the level of consensus required to undertake fundamental reforms. Finally, growing contestation of multilateral institutions and reduced trust in multilateral approaches could end up reducing the willingness of member states to invest in strengthening and integrating the existing system. Addressing these potential obstacles to multilateral reform requires a clear understanding of the recent evolution of the system and key trends in multilateral development finance.

The next two chapters illustrate how recent evolutions of the system and reform efforts are materialising across the two key phases of the multilateral development finance process: (i) inflows to, and (ii) outflows from, the system. Chapter 3 focuses on key trends in multilateral organisations’ funding (multilateral inflows), especially in light of recent efforts to diversify their funding sources and optimise their funding structures. Chapter 4 analyses key trends in the development activities financed by multilateral organisations (multilateral outflows), highlighting their collective contribution to recent crises and exploring how to position them to help address emerging challenges.

References

[19] African Development Bank (2022), Bank Group Sustainable Borrowing Policy, African Development Bank, Abidjan, https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/bank-group-sustainable-borrowing-policy.

[33] AidData (2022), Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 2.0, https://china.aiddata.org/ (accessed on August 2022).

[34] Brookings (2021), Global Governance after COVID-19: Survey Report, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Global-Governance-after-COVID-19.pdf.

[20] Caldara, Dario and Matteo Iacoviello (2022), “Measuring Geopolitical Risk”, American Economic Review, https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/gpr.htm (accessed on 20 July 2022).

[8] Center for Global Development (2022), Extreme Poverty Estimate Following Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine, https://cgdev.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/background%20price%20spike%20analysis.pdf.

[26] China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2019), The Belt and Road Initiative Progress, Contributions and Prospects, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/cese/eng/zgxw/t1675676.htm (accessed on 23 July 2022).

[35] Custer, S. et al. (2021), Listening to Leaders 2021: A report card for development partners in an era of contested cooperation, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/listening-to-leaders-2021.

[21] E3G (2022), One Vision in Three Plans: Build Back Better World & The G7 Global Infrastructure Initiatives, https://www.e3g.org/publications/one-vision-three-plans-build-back-better-world-g7-global-infrastructure-initiatives/.

[25] European Commission (2021), EU Global Gateway Homepage, https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway_en (accessed on 23 July 2022).

[31] European Parliament (2021), Towards a joint Western alternative to the Belt and Road Initiative?, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/698824/EPRS_BRI(2021)698824_EN.pdf.

[24] FCDO (2021), PM launches new initiative to take Green Industrial Revolution global, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-launches-new-initiative-to-take-green-industrial-revolution-global#:~:text=To%20support%20the%20Clean%20Green,a%20new%20Climate%20Innovation%20Facility. (accessed on 23 July 2022).

[41] Financial Times (2022), “Global climate leaders push for overhaul of IMF and World Bank”, Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/e0f65580-8d84-49ec-82b7-47c1b06563b0.

[12] Fitch Ratings (2022), Fitch Revises Outlook on New Development Bank to Negative; Affirms at ’AA+’, https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/fitch-revises-outlook-on-new-development-bank-to-negative-affirms-at-aa-17-03-2022.

[29] G20 (2022), Global Infrastructure Hub, https://outlook.gihub.org/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

[17] G20 (2017), Coordination Between the International Monetary Fund and Multilateral Development Banks on Policy-Based Lending, https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/EN/Standardartikel/Topics/world/G7-G20/G20-Documents/g20-principles-for-effective-coordination-between-the-imf-mdbs.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1.

[16] G20 (2017), G20 Operational Guidelines for Sustainable Financing, https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/EN/Standardartikel/Topics/world/G7-G20/G20-Documents/g20-operational-guidelines-for-sustainable-financing.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1.

[6] G20 HLIP (2021), A Global Deal for Our Pandemic Age, G20 High Level Independent Panel on Financing the Global Commons for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, https://pandemic-financing.org/report/.

[36] Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (2018), 2018 Global Partnership Monitoring Round, https://www.effectivecooperation.org/content/gpedc-monitoring-excel-database.

[14] Government of Barbados (2022), The 2022 Bridgetown Agenda for the Reform of the Global Financial Architecture, https://www.foreign.gov.bb/the-2022-barbados-agenda/.

[15] IMF (2022), Debt Sustainability Analysis Low-Income Countries, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/DSA.

[7] Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (2021), Make it the last pandemic, https://theindependentpanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/COVID-19-Make-it-the-Last-Pandemic_final.pdf.

[28] Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2017), White Paper on Development Cooperation 2016: Japan’s International, https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/page22e_000815.html (accessed on 23 July 2022).

[32] Kenny, C. and S. Morris (2022), “America Shouldn’t Copy China’s Belt and Road Initiative”, Foreign Affairs, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2022-06-22/america-shouldnt-copy-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative.

[40] MOPAN (2022), COVID-19 study.

[4] OECD (2022), Comparing multilateral and bilateral aid: a portfolio similarity analysis, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/2022-mdf-comparing-multilateral-bilateral-aid.pdf.

[2] OECD (2022), “Creditor Reporting System”, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1.

[9] OECD (2022), Development Co-operation Profiles, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2dcf1367-en.

[5] OECD (2022), Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2023: No Sustainability Without Equity, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fcbe6ce9-en.

[30] OECD (2022), The Blue Dot Network: A proposal for a global certification framework for quality infrastructure investment, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/daf/blue-dot-network-proposal-certification.pdf.

[1] OECD (2020), Multilateral Development Finance 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e61fdf00-en.

[27] OECD (2018), “The Belt and Road Initiative in the global trade, investment and finance landscape”, in OECD Business and Finance Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bus_fin_out-2018-6-en.

[22] PwC (2016), China’s new silk route: the long and winding road, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/growth-markets-center/assets/pdf/china-new-silk-route.pdf.

[11] Subacchi, P. (2022), “Is Asia’s development machine stuttering?”, International Politics and Society, https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/foreign-and-security-policy/is-asias-development-machine-stuttering-6055/.

[39] UN (2022), “Funding Compact Indicator Table”, United Nations, Geneva, https://www.un.org/ecosoc/sites/www.un.org.ecosoc/files/files/en/qcpr/2022/Annex-FundingCompact-IndicatorsTable-Ver2b-25Apr2022.pdf.

[3] UNDP (2022), The State of INFF, United Nations Development Programme, New York.

[38] UNOPS (2022), “Statement in response to media coverage on UNOPS S3I and related matters”, United Nations Office for Project Services, Copenhagen, https://www.unops.org/news-and-stories/news/statement-on-unops-sustainable-infrastructure-investments-and-innovation-s3i-initiative-and-related-matters (accessed on 18 July 2022).

[23] US State Department (2021), FACT SHEET: President Biden and G7 Leaders Launch Build Back Better World (B3W) Partnership, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/06/12/fact-sheet-president-biden-and-g7-leaders-launch-build-back-better-world-b3w-partnership/ (accessed on 23 July 2022).

[10] WFP (2022), WFP urges G7: ‘Act now or record hunger will continue to rise and millions more will face starvation’, World Food Programme, Rome, https://www.wfp.org/stories/wfp-urges-g7-act-now-or-record-hunger-will-continue-rise-and-millions-more-will-face.

[37] WHO (2021), WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at 148th session of the Executive Board, World Health Organisation, Geneva, https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-148th-session-of-the-executive-board.

[13] World Bank Group (2021), Poverty, Median Incomes, and Inequality in 2021: A Diverging Recovery, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/936001635880885713/pdf/Poverty-Median-Incomes-and-Inequality-in-2021-A-Diverging-Recovery.pdf.

[18] World Bank Group (2020), Sustainable Development Finance Policy, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/967661593111569878/sustainable-development-finance-policy-of-the-international-development-association.

Note

← 1. Non-core, or earmarked, contributions to multilateral organisations are resources channelled through multilateral organisations over which the donor retains some degree of control in decisions regarding disposal of the funds. Such flows can be earmarked for a specific country, project, region, sector or theme, and they technically qualify as bilateral ODA.