United Kingdom

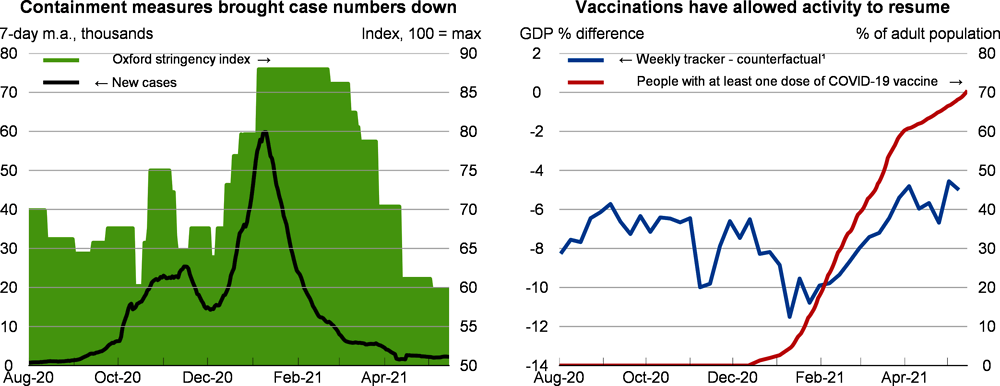

Strong GDP growth of 7.2% in 2021 and 5.5% in 2022 is projected as a large share of the population is vaccinated and restrictions to economic activity are progressively eased. Growth is driven by a rebound of consumption, notably of services. GDP is expected to return to its pre-pandemic level in early 2022. However, increased border costs following the exit from the EU Single Market will continue to weigh on foreign trade. Unemployment is expected to peak at the end of 2021 as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme is withdrawn. Inflation is set to increase due to past increases in commodity prices and strong GDP growth, but should remain below the 2% inflation target.

Fiscal and monetary policies should stay supportive until the recovery firmly takes hold, facilitating structural change as support to existing firms and jobs is scaled down. Public investment should address long-term challenges, notably reducing greenhouse gas emissions and boosting digital infrastructure. Extending higher levels of cash support beyond current plans and continuing to boost training programmes can help affected households. Keeping up the pace of vaccinations and responding to emerging virus mutations are key challenges going forward.

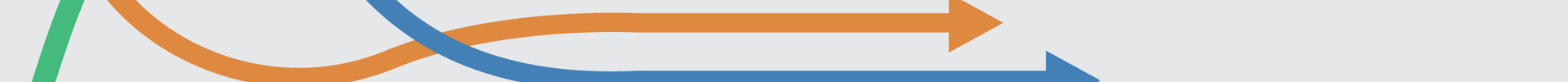

A high rate of vaccinations allows a gradual return to normal

National containment measures combined with a successful vaccination campaign have brought confirmed cases of COVID-19, hospitalisations and deaths down to levels last seen during the summer of 2020. Everyone aged 50 or above and people at increased risk had been offered a first dose of vaccine by mid-April. In England, this has allowed the easing of restrictions according to a four-step roadmap that started with the reopening of schools in March, followed by retail and outdoor hospitality services from April, with most businesses allowed to reopen subject to distancing rules from May. Devolved administrations in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales are all progressively lifting COVID-19-related restrictions towards the summer.

Services sectors are bracing for take-off

GDP contracted in January 2021 on the back of tightened restrictions, although less than widely anticipated as the economy showed increased resilience to containment measures. High frequency data indicate accelerating growth as restrictions have been lifted progressively, and GDP rose in both February and March. Services sector activity remains considerably below the pre-pandemic level, and is lagging behind the construction and manufacturing sectors. The labour market is also stabilising. Employment is on the rise, while unemployment and the number of furloughed employees have fallen since January. A rising number of vacancies is concentrated in accommodation and food services and wholesale and retail trade, the sectors with the largest cumulative job losses since the start of the pandemic.

Policy will remain accommodative in the short term

Fiscal policy will remain accommodative well beyond the phasing out of most containment measures, with stable cyclically adjusted net lending over the projection period. The Office for Budget Responsibility estimates that discretionary spending to support businesses and households and strengthen healthcare and testing capacity amounted to approximately 17% of GDP in the fiscal year 2020-21. The take-up of support policies is set to fall and tax revenues increase as services sectors gradually reopen. A further strengthening of the budget balance is expected when the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS), the Self Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) and the GBP 20 a week increase to the Universal Credit are discontinued after September, along with a number of other crisis supports. In the March budget, the government extended and adjusted the economic support measures put in place early in the crisis and introduced new measures to bring investments forward. The government has signalled tax increases from 2022, when income tax brackets will be frozen, and from 2023, when an increase in corporate income tax is planned. Government-guaranteed loan facilities, which have played an important role in allowing banks to lend to firms without tying up regulatory capital, were replaced by a new facility, the Recovery Loan Scheme, in April. Going out of the crisis, the government’s Plan for Jobs will subsidise jobs for young people and tailor support to the unemployed.

Monetary policy remains accommodative, easing financial stress and supporting demand. The Bank of England has maintained the Bank rate at 0.1% and increased its bond purchasing programme over the course of the crisis to reach a total of GBP 895 billion (more than 40% of 2019 GDP). The pace of bond purchases was slowed in May within an unchanged target stock of total purchases.

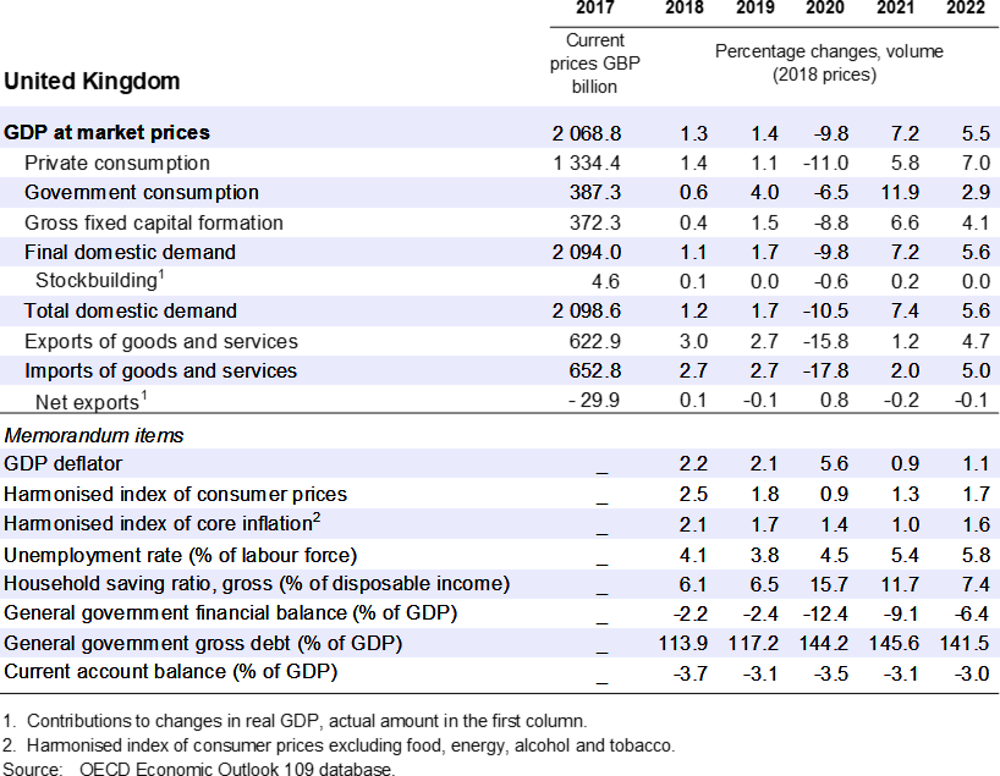

Reopening services will drive a sharp re-bound

The progressive easing of public health restrictions will allow for a solid rebound. Output is projected to grow by 7.2% in 2021 and 5.5% in 2022. Consumption will bounce back sharply as hard-hit hospitality services and retail trade reopen. Public and housing investments are set to continue to hold up well. Business investment is set to accelerate in 2022 as uncertainty is reduced and spare capacity falls, further boosted by an increased deduction for some types of investments. Household saving is forecasted to return to pre-crisis levels in aggregate, as opportunities to consume return. Some additional spending by wealthier households with secure jobs and excess savings during the crisis is projected to be counterbalanced by households in lower income brackets who saved less during the crisis and are set to be more affected by a weak labour market and the winding-down of COVID-19 supports. Trade contracted in early 2021 as a consequence of leaving the EU Single Market and containment measures, but will recover slowly. The unemployment rate is projected to peak at 6.1% at the end of 2021 as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme is phased out. The general government financial deficit will come down to 6.4% of GDP in 2022, and gross public debt is set to peak at 146% of GDP in 2021.

The projection is contingent on the continued success of the vaccination programme in immunising the population, also against emerging virus strains. Supply bottlenecks could hold back consumption and increase inflation beyond what is projected if businesses fail to reopen or cannot attract the necessary staff after the pandemic due to net out-migration. Higher-than-expected consumption if households run down excess savings more than assumed could boost growth considerably, while weaker than forecasted consumption and higher savings could lead to lower growth. A closer trade relationship with the European Union than expected, notably encompassing services, would improve the economic outlook in the medium term.

Policies for a sustainable and inclusive recovery

Monetary policy should not tighten until there are clear signs of price pressures. Fiscal policy should also remain supportive until the recovery is firmly underway, supporting the reallocation of resources towards firms and sectors with better growth prospects. Extending the GBP 20 increase to the Universal Credit, along with upskilling and job placement efforts, would reduce hardship for displaced and low-skilled workers and speed up structural change, but would involve a fiscal cost. Reducing out-of-pocket costs of childcare further would help parents, notably mothers, to increase hours in paid employment and training. Public investment should address long-term challenges, notably reducing greenhouse gas emissions, investing in skills and boosting digital infrastructure.