1. General Assessment of the Macroeconomic Situation

Prospects for the global economy have improved considerably, but to a different extent across economies. In the advanced economies, the progressive rollout of an effective vaccine has begun to allow more contact-intensive activities − held back by measures to contain infections − to reopen gradually. At the same time, additional fiscal stimulus this year is helping to boost demand, reduce spare capacity and lower the risks of sizeable long-term scarring from the pandemic. Some moderation of fiscal support appears likely in 2022 on current plans, but improved confidence and fewer public health restrictions should encourage households to spend. However, in many emerging-market economies, slow vaccination deployment, further infection outbreaks, and associated containment measures, will continue to hold down growth for some time, especially where scope for policy support is limited.

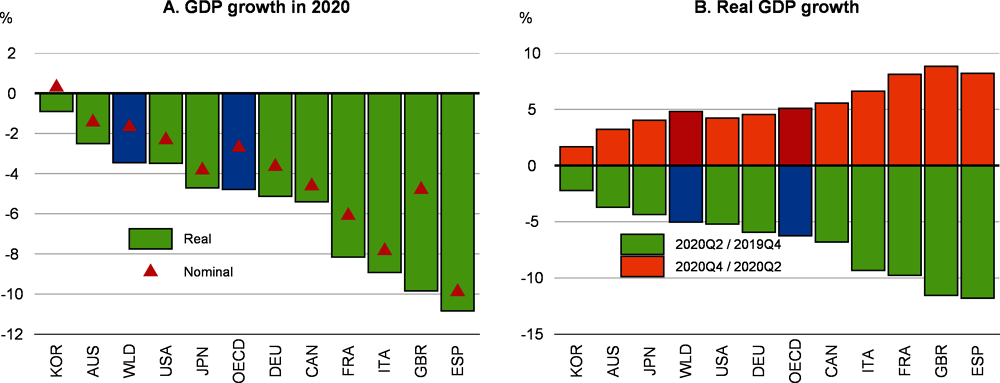

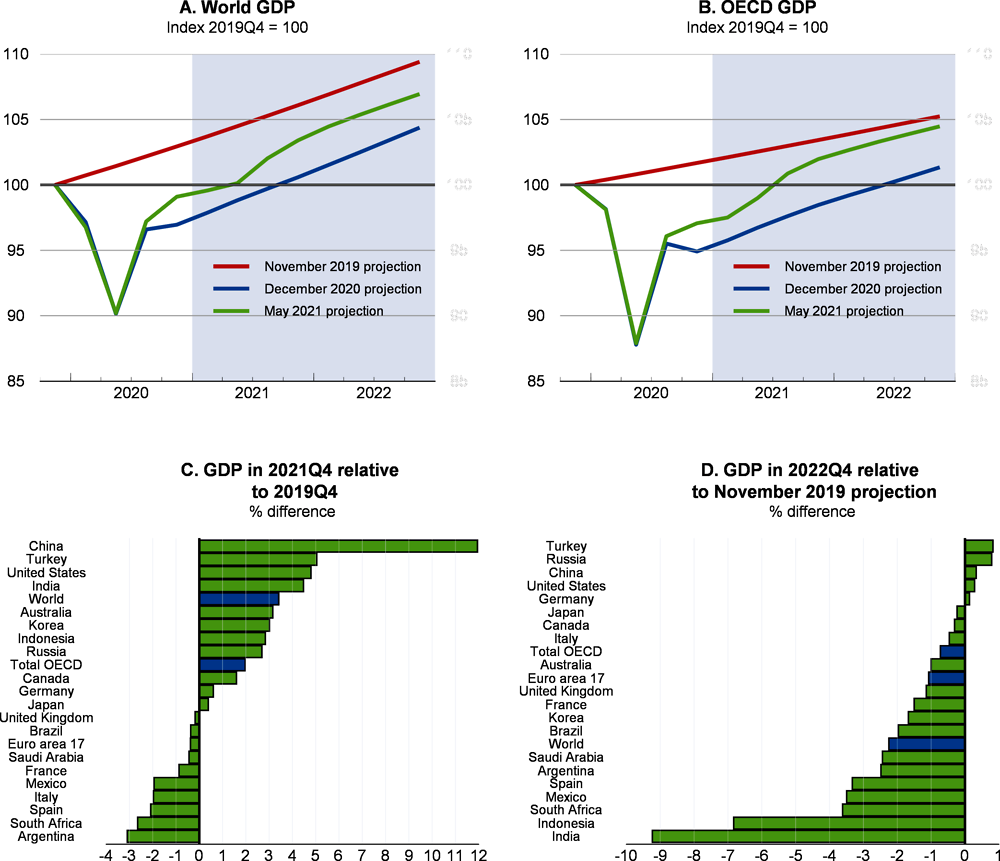

Global GDP is projected to rise by 5¾ per cent in 2021 and close to 4½ per cent in 2022 (Table 1.1). The world economy has now returned to pre-pandemic activity levels, but will remain short of what was expected prior to the crisis by end-2022. Growth in the OECD area could rise to 5¼ per cent in 2021, led by a strong upturn in the United States, and then ease to 3¾ per cent in 2022, with strong private spending helping to ensure that the GDP level returns close to the path expected before the pandemic in most countries. Output in China has already caught up with this path and is set to stay on this trajectory in 2021 and 2022. Some other emerging-market economies, including India, may continue to have large shortfalls in GDP relative to pre-pandemic expectations and are projected to grow at robust rates only once the impact of the virus fades.

Signs of higher input cost pressures have appeared in recent months, but sizeable spare capacity throughout the world should prevent a significant and sustained pick-up in underlying inflation. The recent upturn in headline inflation rates reflects the recovery of oil and other commodity prices, a surge in shipping costs, the normalisation of prices in hard-hit sectors as restraints are eased, and one-off factors such as tax changes, and should ease in the near term. With unemployment and employment rates unlikely to attain their pre-pandemic levels until after end-2022 in many countries, there should be only modest pressures on resources over the coming 18 months.

This benign outlook is subject to significant upside and downside risks related to developments of the virus, household saving and conditions in emerging-market economies and developing countries:

Substantial uncertainty remains about the evolution of the virus. There is a possibility of new more contagious and lethal variants that are more resistant to existing vaccines, unless effective vaccinations are quickly and fully deployed everywhere. This would necessitate the reimposition of strict containment measures, with associated economic costs related to lower confidence and spending. On the upside, faster-than-assumed inoculation and effective efforts to supress the virus before vaccinations are complete would strengthen the recovery in all economies.

Household saving developments are an upside risk, independently of the evolution of the virus, especially in the advanced economies. The financial assets acquired due to higher household saving last year could be used to finance pent-up demand instead of being retained, as assumed in the projections, or used to pay back debt. Given the amounts involved, the spending of only a fraction of accumulated “excess” saving would raise GDP growth significantly, with ensuing price pressures as spare capacity is used up. Households could also normalise their saving rates in 2021 and 2022 faster than assumed.

The materialisation of this upside risk for advanced economies could add to inflation and in turn put vulnerable emerging-market economies and developing countries under financial pressure. Capital outflows and significant repricing of assets, including currencies, could require policy tightening to regain investor confidence. The increased indebtedness of some emerging-market economies and developing countries during the COVID-19 crisis has arguably made these economies more vulnerable to external financial shocks of this kind. At the same time, the emerging-market economies would benefit from stronger demand from the advanced economies, offering some offset to tighter financial conditions.

In this uncertain and unprecedented environment, policy makers will have to continue to be flexible and policies should be contingent on economic developments.

An absolute policy priority is to ensure that all resources necessary are used to deploy vaccinations as quickly as possible throughout the world to save lives, preserve incomes and limit the adverse impact of containment measures. Stronger international efforts are needed to provide low-income countries with the resources needed to vaccinate their populations for their own and global benefits. The sharing of knowledge, medical and financial resources, and avoidance of harmful bans to trade, especially in healthcare products, are all essential to address the challenges brought by the pandemic.

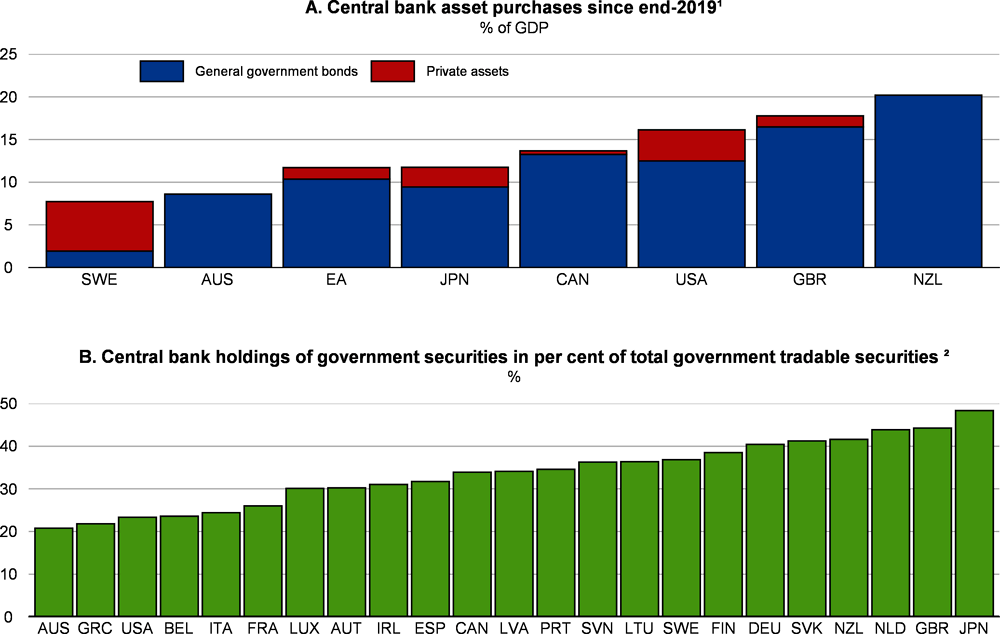

The current very accommodative monetary policy stance should be maintained in the advanced economies, and temporary overshooting of headline inflation should be allowed provided underlying price pressures are contained. Macroprudential policies should be deployed where necessary to ensure financial stability in a prolonged environment of low interest rates and high liquidity.

Continued income support for households and companies is warranted until vaccination allows a significant easing of restraints on high-contact activities. Such measures should be focused on helping people and supporting companies, particularly in sectors still affected by public health restrictions, through grants and equity rather than debt. Even after restraints on activities have been eased, the legacy of the crisis, including over-indebted companies and displaced workers, will require targeted support to avoid excessive insolvencies and scarring. Stronger public investment in health, digital and energy infrastructure will also be needed to enhance resilience and improve the prospects for sustainable growth.

Fiscal policy support should be contingent on the state of the economy. Given the extent of spare capacity at present, the strong fiscal policy stimulus being implemented this year is appropriate. Some moderation in support appears likely in 2022, but in part this reflects the planned end of crisis-related support schemes as the economy reopens, and is warranted provided the recovery evolves as projected. If upside risks were to materialise, with unexpectedly strong improvements in the labour market, fiscal support should be eased, and the opposite should occur if downside risks were to materialise. Ensuring debt sustainability will be a priority only once the recovery is well advanced, but planning for management of the public finances that leaves space for public investment should start now.

Macroeconomic policy support needs to be accompanied by structural reforms that strengthen resilience and economic dynamism, and mitigate climate change. Together, these can help to foster the reallocation of labour and capital resources towards sectors and activities with sustainable growth potential, raising living standards for everyone.

Many emerging-market economies and developing countries have been hit particularly hard by the pandemic. In some cases, extensive borrowing abroad to cushion the blow has added to existing challenges from high sovereign or corporate debt prior to the crisis. While official creditors in the G20 economies have suspended debt service for the poorer countries temporarily, debt restructuring for some of the emerging-market economies and developing countries is likely in the coming years in the absence of debt relief. This process would be facilitated by increased transparency about the full extent of indebtedness, including contingent liabilities and opaque bilateral loans. Stronger international co-operation remains necessary to build on the G20 efforts to address debt problems of emerging market-economies and developing countries.

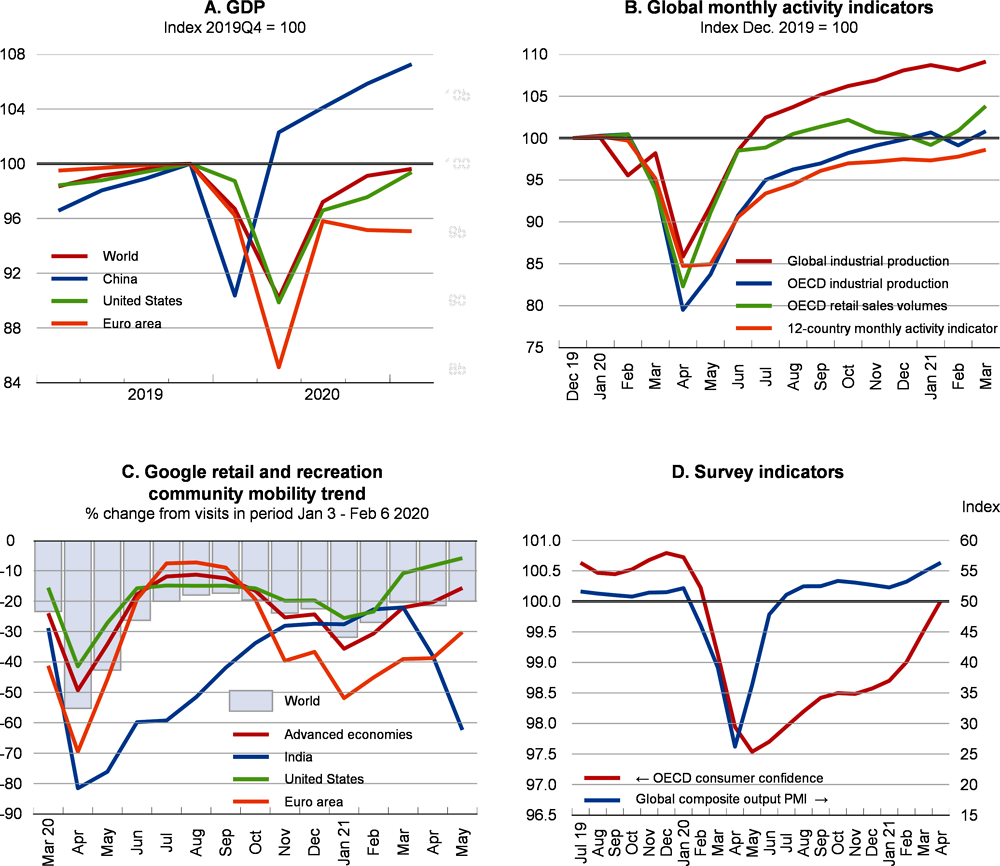

Prospects for a lasting global recovery continue to improve, helped by the gradual deployment of effective vaccines, continued macroeconomic policy support and signs that economies are now coping better with measures to supress the virus. In many countries, the scale of the economic disruption from the pandemic has been exceptionally large, and the recovery is likely to be prolonged. Global GDP declined by around 3½ per cent in 2020, and OECD GDP by around 4¾ per cent, substantially larger falls than in the global financial crisis. Output in some European countries and emerging-market economies declined particularly sharply, reflecting the challenges in controlling the pandemic and the importance of travel and tourism in many economies (OECD, 2021a). Other countries, including many in the Asia-Pacific region, saw only mild output declines in 2020, helped by strong and effective public health measures to supress or eliminate the virus spread, and the regional uplift provided by the rapid recovery in China. In all countries, the burden of the crisis fell disproportionately on the poorest and most vulnerable.

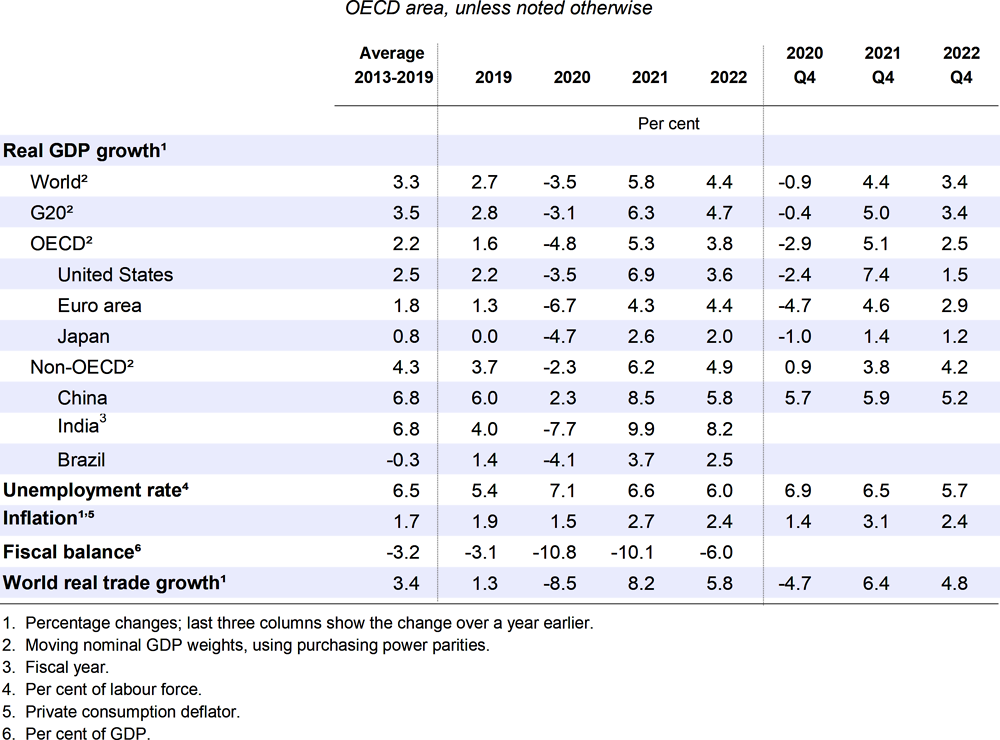

The economic upturn since mid-2020 has been uneven and remains far from complete (Figure 1.1). For the world as a whole, GDP in the fourth quarter of 2020 was still 4% lower than expected a year earlier prior to the pandemic, representing a real income shortfall of close to USD 5 trillion (in PPP terms). Differences in statistical procedures have contributed to the cross-country variation in GDP outcomes, but their effects generally appear to be modest (Box 1.1). The pace of the global recovery moderated in the first quarter of 2021, with increasing signs of divergence across and within countries, reflecting different progress in vaccination deployment and renewed virus waves in some economies.

Global GDP growth is estimated to have eased to around 0.5% in the first quarter of 2021 (quarter-on-quarter, non-annualised) (Figure 1.1, Panel A). Momentum strengthened in the United States, helped by policy stimulus and rapid progress with vaccinations, but renewed output declines occurred in a number of economies, including the euro area and Japan. Growth also moderated in China, with gradual policy normalisation now beginning. In aggregate, amongst the countries with monthly economy-wide estimates of economic activity, output in March 2021 remained around 1½ per cent below the pre-pandemic level (Figure 1.1, Panel B)

Global mobility, measured using the Google location-based measures of retail and recreation mobility, improved in both February and March but stalled in April (Figure 1.1, Panel C). Mobility rose in the advanced economies, particularly those where containment measures are being eased such as the United States, Israel and, from April, the United Kingdom. In contrast, renewed declines in mobility have occurred in parts of Europe until recently, as well as Latin America and India, reflecting more stringent containment measures to address renewed virus surges.

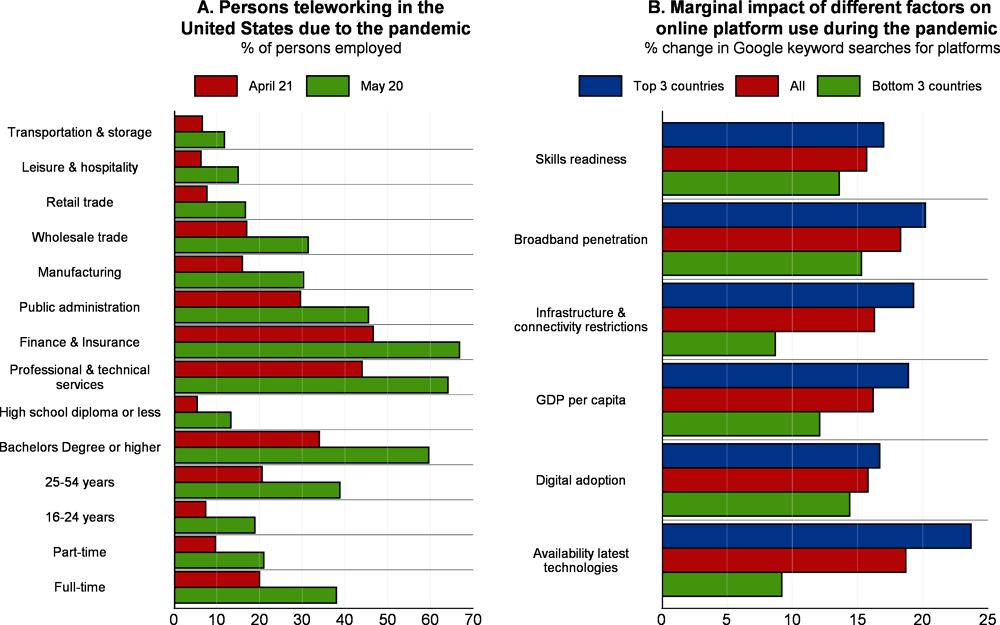

Public health measures to reduce the spread of the virus, and the associated declines in mobility, are now having a smaller adverse impact on activity than in the early stages of the pandemic (OECD, 2021b). Containment policies are more carefully targeted, and businesses and consumers have adapted to changes in working arrangements and sanitary restrictions.

Global industrial production has continued to strengthen this year. Global trade in goods has surpassed pre-pandemic levels (see below), supported by the strong demand for IT equipment and medical supplies (Figure 1.1, Panel B). However, supply shortages in the semiconductor sector due to the exceptionally strong demand for IT equipment during the pandemic, and temporary disruptions to the output of some major producers, are now beginning to constrain output in some industries, particularly car production.1

Global retail sales volumes have now picked up again, after remaining unchanged for several months (Figure 1.1, Panel B). Many service sector activities are still affected by health-related restrictions, and cross-border services trade remains extremely weak, but the gradual reopening of economies and support from fiscal policy have strengthened demand. Household saving rates remain above pre-pandemic levels (see below), providing scope for future spending, but consumer confidence is recovering (Figure 1.1, Panel D).

Business confidence has continued to improve (Figure 1.1, Panel D). In April, the global composite output PMI rose to its highest level since mid-2010. Manufacturing and, to a lesser extent, services indicators both strengthened, although not in all major economies.

The pandemic affected all countries’ GDP in 2020 but with some noticeable disparities (Figure 1.2, Panel A), including sizeable differences across countries in the relative declines of nominal and real GDP, and implicitly in the GDP deflator. Cross-country variation in observed GDP outcomes arises from many different sources, including the timing and severity of the pandemic and the associated policy responses, the different sectoral mix of economic activities in each country, and differences in statistical procedures. This box explores the extent to which one particular statistical difference – the treatment of non-market services – accounts for some of the variation in real GDP growth across countries during 2020. While marked differences can be seen in the contributions from non-market services across countries, these are generally small relative to the overall changes in GDP and make little difference to the relative GDP declines across countries. These issues will remain pertinent in 2021, given the renewed shutdowns and subsequent reopenings that are occurring.

Estimating the volume of output in the health and education sectors is challenging as output is often supplied without charge or at prices that are not economically significant. Different conventions exist across national statistical institutes (NSIs) to compute the volume of non-market services: using deflated measures of input values, or direct volume measures of either inputs (such as the number of employees or hours worked) or outputs (such as the number of students or number of patients treated) (OECD, 2020a).

The COVID-19 pandemic has added to these longstanding issues, with both sectors heavily affected by restrictions. For instance, workers may be paid as before during shutdowns but provide a reduced volume of services. This results in differences between approaches that deflate input costs (such as the wage bill, which did not change) or measure the volume of activities via inputs (such as the number of teachers, which did not change) or outputs (such as the number of students coming to school, which did change). Services may also be delivered in different ways, such as the partial replacement of school-provided education, which is included in GDP, with unpaid home schooling, which is not. Adjustments may also be needed to capture new activities, such as the introduction and rapid expansion of test, track and trace services, and more recently vaccinations, with associated technical issues of whether the weights given to these new activities are appropriate. The pandemic also temporarily revamped many health services from traditional to COVID-19-related care. All these factors may have reduced the comparability of economic outcomes across countries.

The UK Office for National Statistics is one of the few major NSIs to follow the volume indicator approach for most health and education outputs (ONS, 2021), which is recommended by the European System of National Accounts (Eurostat, 2020a). Other statistical agencies, including the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, have made ad-hoc adjustments to their standard approaches to try to capture particular aspects of changes due to the pandemic (BEA, 2020). Although different statistical methods may have led to some divergence in reported output declines during the pandemic, the return to normal should reverse such divergence, with larger output gains from reopenings in those countries that use specific output-based measures of the volume of services. Countries that experienced the largest GDP contractions during the first half of 2020 typically had a stronger rebound in the latter half of the year (Figure 1.2, Panel B).

The extent to which these statistical factors can help to account for observed cross-country differences in real GDP growth during the pandemic can be assessed by looking at the contribution to real GDP growth either from government consumption (expenditure approach) or from the output of non-market services (output approach). These two approaches are related, but distinct, given that there are differences across countries in the mix of publicly and privately provided non-market services (with private consumption the main expenditure counterpart to the latter). A comparison using annual growth rates for 2020,1 instead of specific quarters or semesters, reduces the risk of bias from distinct outbreak timings (including for the different waves). Looking across countries:

Using the expenditure approach, the contribution from government consumption is the most negative for the United Kingdom (about 1.5 percentage points) and the most positive for Australia (about 1.5 percentage points) (Figure 1.3, Panel A). Nonetheless, the countries with the largest GDP declines typically also had the largest negative contributions from expenditure excluding government consumption.

The gross value added breakdown shows the relatively large negative contribution from non-market services for Chile (1.9 percentage points) and the United Kingdom, but a positive contribution in a few countries (Figure 1.3, Panel B). However, as with the expenditure approach, the countries with the largest declines in total real value-added output typically had the largest negative contributions from output excluding health, education and public administration.

Overall, differences in government consumption and non-market output account for only a small part of the cross-country variation in annual GDP growth in 2020.

← 1. An alternative exercise using the growth rate over 2019Q4-2020Q4 reaches a similar conclusion.

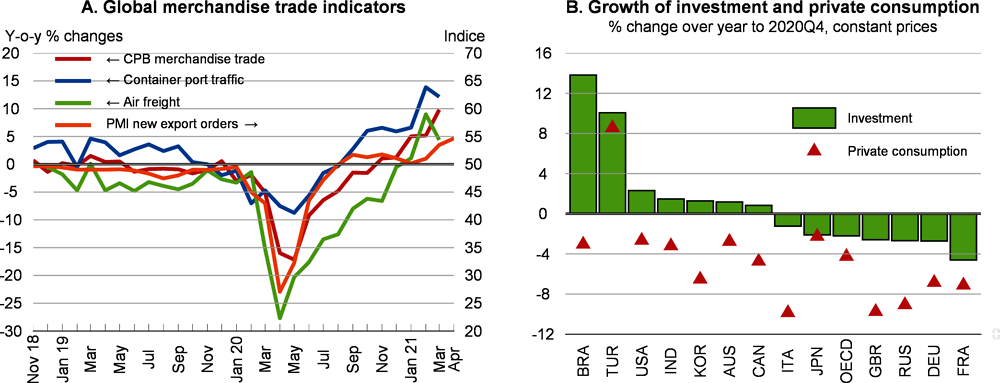

Global merchandise trade indicators continue to rebound (Figure 1.4, Panel A), helped by stronger global demand for personal protective equipment and IT goods, and the gradual release of pent-up demand for durable goods in some advanced economies. Container port traffic and total merchandise trade volumes are now above 2019 levels, helped by the strong trade rebound in Asia. In contrast, services trade remains soft, particularly air traffic, with total commercial flights in April around 32% lower than on average in 2019, and international air passenger traffic revenue in March still 88% lower than two years earlier.

Despite continued uncertainty, investment has rebounded in many economies since mid-2020, helping to underpin the trade upturn (Figure 1.4, Panel B). In the fourth quarter of 2020, aggregate investment in the G7 economies was unchanged from a year earlier, whereas private consumption remained almost 4½ per cent lower than prior to the pandemic, and investment surpassed the pre-crisis level in several large economies, including the United States, Turkey and Brazil. Business equipment investment has been spurred by new investments in the equipment and systems needed for remote working and, in some emerging-market economies, low real interest rates and quasi-fiscal credit supply. Housing investment has also picked up, especially in North America, helped by favourable financing conditions and only limited restrictions on construction activities. Substantial government support has also enabled many firms to stay in business and helped to ensure the continued availability of external finance (see below).

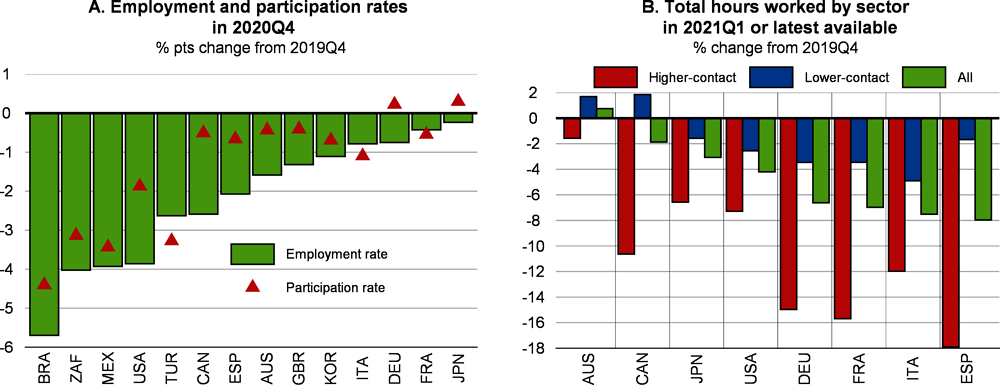

Across the OECD economies, around 7½ million more people than prior to the crisis remained unemployed in March, inactivity rates have risen and aggregate employment rates have declined. Women, youth and low-income workers have been particularly exposed to the risk of job losses during the pandemic. In the fourth quarter of 2020, the labour force participation rate and the employment rate in the median OECD economy were 0.3 and 1 percentage point lower respectively than a year earlier (Figure 1.5, Panel A). Relatively large declines occurred in the United States and many emerging-market economies, but job retention measures, such as short-time work schemes and wage subsidies, continued to help preserve employment in Europe and Japan. In developing countries, substantial job losses have increased poverty and deprivation for millions of people.

Many jobs remain precarious. In most major economies, even those in which employment has been preserved, total hours worked in customer-facing service sectors remain well below the pre-pandemic level (Figure 1.5, Panel B). Aggregate hours worked in these sectors account for between 25-30% of total economy-wide hours worked in most economies, and over 35% in Italy and Spain. In Australia, Canada and the United States, where aggregate labour market conditions and hours worked continued to improve in the first quarter of 2021, shortfalls in hours worked still remained in the most affected sectors.

However, new job opportunities have begun to appear in most countries, despite continued containment measures. This is reflected in rising online job postings (Figure 1.6), though the gains remain uneven. Job growth is largely concentrated in healthcare and the production sector, with job postings in several service sectors remaining below the immediate pre-pandemic level. Survey evidence in the United States also shows signs of skills shortages for small businesses, possibly reflecting lower labour force participation and the separation of some employer-employee job matches during the early months of the pandemic.

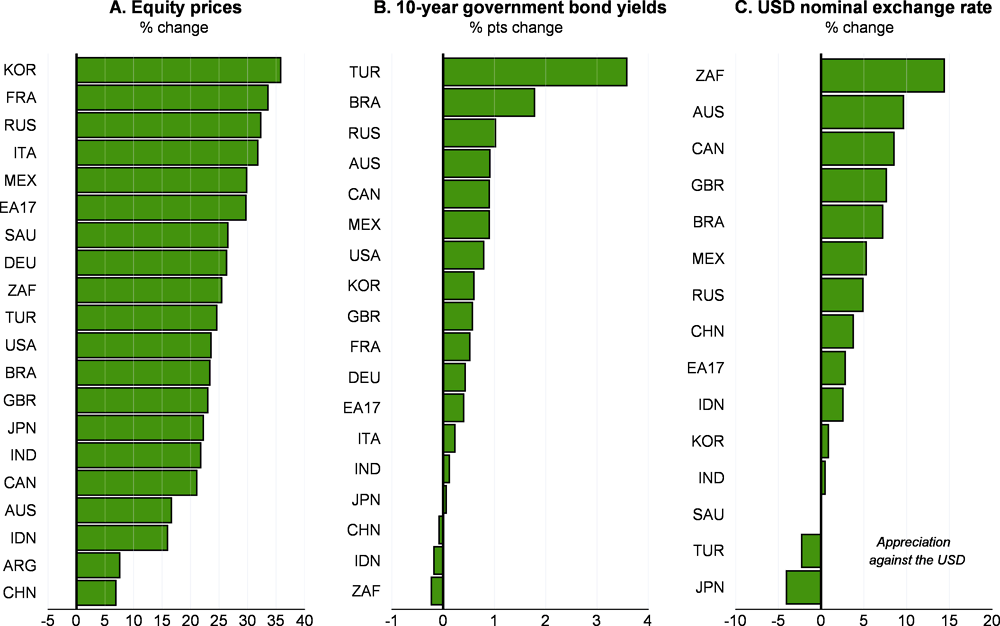

Financial conditions have evolved differently among asset classes and large economies since late last year (Figure 1.7). Equity prices have increased strongly in most large advanced and emerging-market economies, driven by anticipation of a faster recovery due to vaccinations and increased government support in a number of countries. A better economic outlook and expectations of higher inflation, particularly in the United States, have boosted 10-year government bond yields in advanced economies. This bond yield increase has been smaller in the euro area. In several large emerging-market economies the decline in government bond prices (which move inversely to yields) also reflected a reversal in global risk appetite and domestic policy and economic challenges, though many currencies have recently appreciated against the US dollar (see below).

The global recovery is projected to strengthen as vaccination deployment becomes widespread

The emergence of effective vaccines has improved prospects for a durable economic recovery provided such vaccines can be deployed rapidly throughout the world and supportive fiscal and monetary policies continue to underpin demand. However, considerable uncertainty remains about near-term developments, with high levels of infections still occurring in some countries, and the pace at which the most heavily affected economies and sectors can recover. It will take some time before production can be raised sufficiently and vaccines distributed to all in need, and risks remain from potential mutations of the virus resistant to current vaccines. Vaccination campaigns are proceeding at different rates around the world (Figure 1.8), often starting more slowly than initially planned, and the scale of policy support and sectoral specialisation differ considerably across economies. Some targeted restrictions on mobility and activity may still need to be maintained for some time, particularly on cross-border travel. This will affect the prospects for a full recovery in all countries, even ones in which vaccinations are proceeding quickly or in which the incidence of the virus is very low.

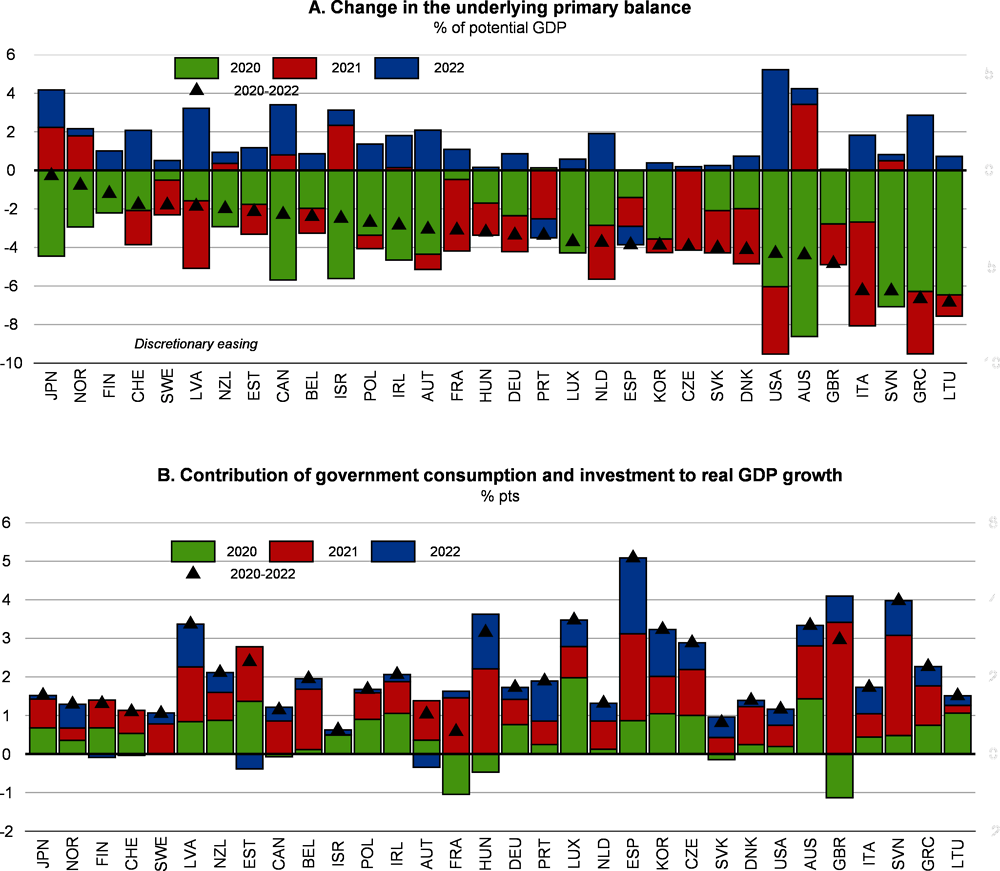

Many countries have announced new fiscal measures or prolonged emergency support schemes in recent months. As a result, there is more fiscal support this year than had seemed likely late last year, reducing the risk of lasting costs from a prolonged recovery.2 The impact of stronger fiscal support will depend in part on the measures undertaken. Stronger government consumption and investment will feed through to final demand directly, but additional household income support may be saved or used for debt repayments by some households, especially while containment measures are in place (see below).

The large fiscal stimulus in the United States this year will help to strengthen the global recovery. In particular, the American Rescue Plan of USD 1.9 trillion could raise US output by between 3-4% in the first full year following implementation (the four quarters to 2021Q1), and global output by around 1% (OECD, 2021b). All economies benefit from stronger demand from the United States, with output rising by between ½-1 percentage point in Canada and Mexico, both close trading partners, and between ¼-½ percentage point in the euro area, Japan and China.

The balance between the key factors shaping the projections differs across economies:

In the advanced economies, the progressive rollout of an effective vaccine is assumed to be completed by the autumn of 2021, and much earlier in some countries, allowing restrictions on contact-intensive activities to be rolled back. New fiscal measures will also support demand in the near term in several countries, with the impact of income support for households on spending gaining traction as economies reopen. Improvements in confidence and labour market conditions and a decline in household saving ratios are also expected to help maintain spending growth in 2022, offsetting a moderation in fiscal support.

Prospects for early completion of vaccinations are limited in many emerging-market economies, with Chile a notable exception. Current and further virus outbreaks in some countries are assumed to require tighter public health measures to be maintained in the near term. Scope to provide additional macroeconomic policy support is also limited in many countries. Commodity exporters should benefit from high commodity prices and the revival of global merchandise trade, but tourism-dependent economies face a slow recovery, and household real incomes will be adversely affected by higher energy and food costs.

Based on the assumptions set out above, the global recovery is projected to strengthen gradually, particularly in the latter half of this year, with global GDP projected to pick up by 5¾ per cent in 2021, and close to 4½ per cent in 2022 (Table 1.1; Figure 1.9). OECD GDP is projected to rise by around 5¼ per cent in 2021 and 3¾ per cent in 2022. Output in some countries, notably China, has already surpassed the pre-pandemic level, and by mid-2021 global GDP and US output should do so as well. Other countries are recovering more slowly, including many in Europe (Figure 1.9, Panel C). Considerable heterogeneity in near-term developments is likely to persist, both between advanced and emerging-market economies and between wider regions. The risk of lasting costs from the pandemic also remains high, with global output projected to remain weaker at the end of 2022 than expected prior to the pandemic (Figure 1.9, Panel D). This is particularly the case in many emerging-market economies, with the output shortfall in the median economy at the end of 2022 projected to be around 3½ per cent, more than twice that in the median advanced economy.

Near-term developments and prospects differ substantially between economies over the next 18 months.

In the United States, GDP growth is projected to be close to 7% in 2021, before easing to around 3½ per cent in 2022. Fiscal support is providing a considerable boost for growth and confidence and labour market indicators are improving, helped by the gradual reopening of the economy and the relatively advanced pace of vaccinations. Accommodative monetary policy should continue to support investment, particularly in the housing market, and a gradual return of the household saving rate towards pre-pandemic norms should support private consumption as the impact of fiscal support wanes next year. The American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan are not incorporated in the projections, but if implemented would boost growth in 2022.

The recovery in Japan has slowed, with GDP declining in the first quarter of 2021. Strong external demand is helping to support manufacturing activity, but public health measures are checking private consumption and service sector output. Economy-wide activity should gradually pick up through 2021-22 as the vaccine rollout gains pace, with GDP projected to rise by 2½ per cent this year and 2% in 2022. The fiscal stance is set to tighten this year and in 2022, but strong public investment and external demand will help to underpin activity, along with reductions in the household saving rate.

Euro area output declined in the first quarter of 2021, with private consumption and service sector activity held back by stringent containment measures. However, strong external demand is boosting manufacturing activity and short-time work schemes have preserved employment. Activity is expected to strengthen through 2021 as vaccination deployment gains momentum and restrictions are lifted progressively, with GDP rising by just over 4¼ per cent this year, and close to 4½ per cent in 2022. Fiscal policy is expansionary this year and mildly restrictive in 2022, with Next Generation EU funds assumed to help support investment during the projection period and some crisis-related measures being phased out as the recovery strengthens. Accommodative monetary policy should help business investment recover gradually, and private consumption should be boosted by pent-up demand and a decline in household saving rates.

Robust growth is expected to continue in China, with GDP rising by around 8½ per cent this year and 5¾ per cent in 2022. Export growth is buoyant, pushing up the current account surplus, and monetary policy remains accommodative, but some fiscal policy support is being withdrawn this year and credit growth is moderating gradually. Progress in rebalancing the economy from industrial production and investment to services and private consumption has been interrupted by the pandemic, but should resume as the vaccination rollout gains pace and confidence improves. Significant financial risks remain, particularly from elevated corporate sector debt.

In India, the rapid rebound in activity since mid-2020 has paused, with the resurgence of the pandemic and renewed localised containment measures raising uncertainty and hitting mobility. Higher commodity prices have also pushed up inflation, reducing household real incomes. Monetary policy remains accommodative, with plans for gradual normalisation being put on hold, but scope for additional fiscal support is limited. Provided the pandemic can be contained quickly, GDP growth could still be around 10% in FY 2021-22 and 8¼ per cent in FY 2022-23, with pent-up consumer demand, easy financial conditions and strong external market growth helping the recovery to gain momentum.

In Brazil, the resurgence of the virus, renewed local mobility restrictions and the slow vaccination rollout have checked the momentum of the recovery and hit confidence. Policy interest rates have begun to rise, due to higher inflation, although real interest rates are still low. Fiscal space is limited, but some support for incomes is provided by the new temporary programme of emergency benefits. Provided the pandemic can be controlled, and the pace of vaccinations improved, GDP is projected to rise by around 3¾ per cent in 2021 and 2½ per cent in 2022. Strong external demand is helping to maintain export growth, and domestic demand – particularly household consumption – should pick up gradually from the latter half of 2021.

Labour market conditions are projected to improve gradually. The unemployment rate in the OECD economies is expected to fall by around 1 percentage point over the projection period, from just under 6¾ per cent in the first quarter of 2021 (Figure 1.10, Panel A). This will still leave unemployment above pre-crisis rates in many countries, with continued labour market slack containing wage growth in 2021-22. Employment growth is projected to recover steadily, rising by around 1¾ per cent per annum in 2021-22 in the OECD economies. In the United States, strong job creation is projected this year, helped by the impetus provided by the American Rescue Plan, with employment rising by over 3½ per cent and the unemployment rate declining by 1½ percentage points over the year to the first quarter of 2022. Smaller improvements are projected in the euro area and Japan, reflecting the successful preservation of jobs through policy support. Companies in many countries have considerable scope to meet improved demand by expanding hours worked per employee, rather than the overall size of their workforce.

By the end of the projection period, the employment rate in the median OECD economy is projected to still be below that at the end of 2019 (Figure 1.10, Panel B), with diverse outcomes across countries. The employment rate is projected to recover fully, on average, in those countries with relatively high employment rates prior to the crisis. In contrast, the employment rate is projected to remain well short of pre-pandemic levels in some countries with comparatively low pre-pandemic employment rates. Participation rates also remain below the pre-pandemic level in many countries at the end of 2022, including in the United States. In part, these gaps may reflect the sectoral mix of activities, but they also point to the need for enhanced reforms to improve activation and job creation in many countries.

Although the projected pace of the recovery has improved from what appeared likely a few months ago, with business investment growth in the OECD economies now projected to average 4¾ per cent per annum in 2021-22, the risks of permanent costs from the pandemic remain high in many countries. Weaker capital accumulation, lower employment rates, reduced participation rates, and some reductions in skills and business efficiencies have all contributed to downward revisions to conventional but uncertain potential output growth estimates since the start of the pandemic. A similar pattern is apparent in downward revisions to consensus expectations for the level of output in the medium term (Box 1.2).

GDP plummeted in 2020 in most countries, following the COVID-19 outbreak, and restoring pre-crisis GDP levels will take time in many of them. A key issue is the extent to which shortfalls may persist into the medium term through reductions in supply potential. As past crises have shown, such reductions can be substantial (Ollivaud and Turner, 2014). This box sets out the differences between the current OECD potential output growth estimates for 2019-22 and the estimates made prior to the onset of the pandemic. Although inherently uncertain at this stage of the recovery, the revisions suggest some scarring from the pandemic in almost all economies.

The OECD estimates of potential output – a measure of what the economy can produce abstracting from temporary cyclical fluctuations – are derived using an aggregate Cobb-Douglas production function with three key factors, potential employment, the productive capital stock and trend labour efficiency (EFF) (Chalaux and Guillemette, 2019). Evaluating potential output during the pandemic requires some difficult judgements. The enforced closure of businesses due to containment measures can be viewed as a reduction in supply that is reversed subsequently once they are permitted to reopen. A related approach, reflected in the OECD estimates, is that the pandemic involves a large adverse shock to demand, with government support programmes for jobs and incomes helping to preserve much of potential output while containment measures are in force. This second approach reduces the cyclicality in potential output estimates, but still allows for possible reductions in supply from factors such as lower capital accumulation, longer spells of unemployment, skills loss, supply-chain adjustments, business failures and changes in competitive pressures.

Though highly uncertain and subject to future revision, current estimates suggest that average annual global potential output growth from 2019 to 2022 could now be over 0.5 percentage point weaker than estimated prior to the pandemic (Figure 1.11, Panel A).1 If this lasts, and there are no offsetting policies, global real output will be 3% lower than projected prior to the pandemic after five years, and about 5½ per cent lower after a decade. These differences are distributed unevenly across countries, with small losses in most advanced economies and some emerging-market economies, but sizeable losses in a number of large emerging-market economies. The approach also reflects some changes to potential output estimates that are not directly related to COVID-19, but these are generally small for most countries.2

Annual potential growth over 2019-22 in the median advanced and emerging-market economy could have declined by 0.3 and 0.4 percentage point, respectively, implying an output loss of about 1.6% and 2.2% respectively after five years. Larger OECD countries appear more resilient in that regard, with emerging-market economies tending to have the largest estimated negative impacts.

Amongst the major advanced economies, losses are estimated to be relatively small in Japan, Canada and the United States. Declines in potential output growth in major euro area members could be 0.3 percentage point per annum on average over 2019-22. The United Kingdom could suffer the biggest reduction amongst G7 countries (a decline of 0.5 percentage point per annum), in part reflecting the additional adverse supply-side effects from 2021 following Brexit (Kierzenkowski et al., 2016; OECD, 2020b).

For the major emerging-market economies, the estimated reduction in potential output growth is smaller for Brazil (0.2 percentage point per annum) and China. Most other countries appear to face larger losses, especially India, Saudi Arabia and Argentina.

A cross-check on the possible medium-term implications of the pandemic can be obtained by looking at how longer-term consensus forecasts have evolved since the pandemic began. Annual GDP growth forecasts can be cumulated to obtain an implicit GDP level over time. Revisions to long-term growth projections from Consensus Economics between January 2020 and April 2021 for selected countries also imply that the GDP level in 2025 is now expected to be lower than prior to the pandemic in most major countries, with the exception of the United States (Figure 1.11, Panel B). Again, G7 countries usually lose less than large G20 emerging-market economies.

Looking in detail at the sources of the changes in OECD potential output growth estimates shows the following:

Weaker capital stock growth accounts for about one-third (0.1 percentage point) of the revision to the median advanced OECD country potential output growth estimates. The investment gap is usually more pronounced for emerging-market economies, notably for Mexico and India.

The contribution from weaker sustainable employment growth is 0.1 percentage point for the median advanced OECD country, and larger for Brazil (0.5), Italy (0.2) and the United Kingdom (0.2). For Brazil and other emerging-market economies, this comes from weaker trend labour force participation rates.

The decline in EFF growth accounts for the remaining part (0.1 percentage point) for the median advanced OECD country. It is the main factor when the revision is large, notably for Argentina, India and Saudi Arabia. The concentration of revisions to EFF growth in some countries reflects the difficulty of projecting underlying EFF growth when observed output falls sharply relative to observed factor inputs, as in 2020. Changes in hours worked per employee and the technologies used, organisational efficiencies, the sectoral mix of activities, and competitive pressures at home and abroad are all incorporated in this factor.

← 1. Revisions to potential output growth in 2019 are included in the calculation as the filter-based estimates of the underlying trends for employment and labour efficiency that year are partly affected by the inclusion of the data for 2020.

← 2. An alternative computation, looking at the difference between the pre-pandemic estimate of the change in average annual potential output between 2015-18 and 2019-22 and the current estimate of this change, yielded broadly similar results.

Inflation is expected to increase temporarily but the longer-term outlook remains uncertain, with upside risks

In most advanced and emerging-market economies, inflation has picked up since the last year in line with the rise in oil and other commodity prices (Figure 1.12, Panel A), though it remains below pre-pandemic levels. Temporary supply shortages in specific sectors, including semiconductors and shipping, and signs of skills shortages for some small businesses, are also contributing to the higher input cost pressures apparent in business surveys (Figure 1.12, Panel B; Box 1.3).3 In emerging-market economies, the past depreciation of currencies and increases in indirect taxes and regulated electricity prices have also added to price pressures. The improved prospects for a sustained global recovery have also pushed up expectations of future inflation, particularly in financial markets.

Prices (especially of energy and food) have been volatile due to specific crisis-related factors and measurement issues, making the identification of underlying price pressures difficult. Uncertainty about underlying inflation has been high in all economies as collecting data on the prices of some services has been complicated by containment measures, necessitating their extrapolation by statistical offices. In 2020, in some cases, this led to an upward bias in inflation (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020; Eurostat, 2020b; O’Brien et al., 2021). In contrast, significant temporary changes to consumption patterns, which were not reflected in weights used to calculate the consumer price index, resulted in an underestimation of inflation. This may be reversed in 2021 and 2022, as activity reopens where it is currently restrained.4 Moreover, the altered timing of seasonal sales and temporary VAT changes (for instance in Germany and several other euro area countries) added to inflation volatility.5

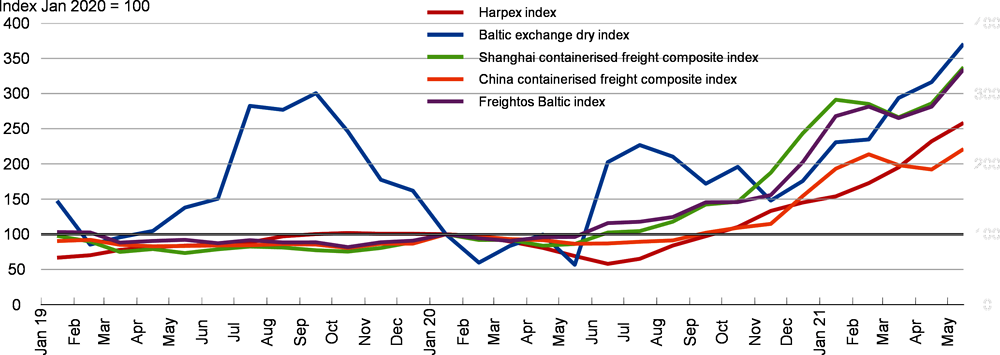

Shipping cost rates have soared in recent months due to the conjunction of booming demand for consumer durables from Asia and supply-side bottlenecks created by sanitary restrictions in ports and terminals. These have slowed loading and unloading operations and crew changes. Prices of containerised freight started to rise in the second half of 2020 and rose further in the first quarter of 2021, when the average quarterly increase across the main indices of global shipping costs ranged between 30% and 65% (Figure 1.13).

On the demand side, the pandemic led to a global demand drop at the start of 2020, followed by a faster-than-expected recovery at the end of 2020. Pent-up demand caused by lockdowns in the first half of 2020, shifts in consumption patterns towards durable goods, and government income support all strengthened demand for goods when transportation services were still limited.

On the supply side, multiple factors are compounding shipping delays. Vessels are currently used at full capacity with a rather low idle rate of 1.5%, but containers remain scarce. Congestion at ports and lower productivity at terminals and inland depots have also led to bottlenecks. Distancing rules and reinforced hygiene standards have increased delays between crew shifts. These have prolonged processing times at ports, hampered the return of containers to Asia and generated delays along the entire shipping chain. The March blockage in the Suez Canal also added to shipping disruption and delays.

This atypical situation is expected to persist for a few more months. Port congestion continues to be a big bottleneck in the United States, where all loading/unloading slots for cargoes from/to Asia are fully booked throughout the second quarter of 2021. The reopening of European economies is also impacting supply and demand. In this context, industry experts do not foresee any normalisation of prices before the end of 2021.

Rising shipping costs will boost consumer price inflation temporarily

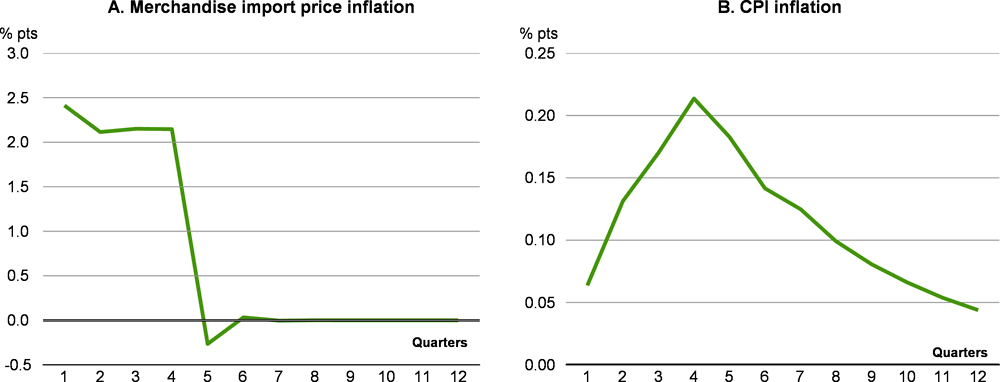

The overall effect of the recent rise in shipping costs on consumer price inflation in OECD countries depends on the impact of a change in shipping costs on merchandise import price inflation1 and the pass-through from merchandise import price inflation to consumer price inflation.2 Empirical OECD estimates of these two relationships can be used to assess the implication for inflation of the average 50% rise in container prices observed in the first quarter of 2021.

Assuming that shipping costs stabilise at their current level for the rest of 2021, the key results are:

In the short run, the rise of 50% in shipping costs observed in the first quarter of 2021 is estimated to raise quarter-on-quarter import price inflation by 2.5 percentage points. After one year, merchandise import price inflation is estimated to rise by 2 percentage points (Figure 1.14, Panel A).

The estimated short-run pass-through of import price inflation to consumer price inflation is modest: assuming an increase in goods import price inflation of 10 percentage points, the quarter-on-quarter consumer price inflation rate would rise by only 0.26 percentage point.

The estimated initial increase in import price inflation would lead to an overall rise in year-on-year consumer price inflation by about 0.2 percentage point after a year (Figure 1.14, Panel B). It would recede gradually thereafter, reflecting long dynamics in the relationship.

In an alternative scenario in which shipping costs gradually decline to a price level slightly higher than prior to the pandemic starting from the second half of 2021, merchandise import price inflation would be raised by 0.6 percentage point after one year, while consumer price inflation would increase by 0.2 percentage point. The order of magnitude is very similar to the original estimate because the impact is mostly driven by the rise in import prices in the first quarter following the initial shock. The long-lasting, but very small, impact on consumer price inflation in the following quarters stems from the lagged effect of past inflation.

← 1. Besides changes in shipping costs, the estimated quarterly regression accounts for changes in the competitive pressure from domestically produced goods and services (proxied by the domestic demand deflator) and costs abroad (proxied by the trade-weighted sum of export prices in trading partners). Exchange rate effects are already included in price indices expressed in US dollars. Notwithstanding the fact that each shipping cost index, evaluated singularly, has a positive and statistically significant impact on merchandise import price inflation, the Harpex index is used for the analysis due to its better predictive performance.

← 2. The quarterly Phillips curve specification includes the output gap, real merchandise import price inflation (measured as the difference between import price growth and GDP deflator growth) and a dummy variable to correct for changes in standard VAT rates in specific quarters. The same panel equation has been estimated without the VAT dummy in order to include the United States in the sample, as no standard VAT rate exists for the country as a whole.

In the short term, the 12-month inflation rate is projected to increase significantly due to the past rise in commodity prices, in particular oil, and some one-off effects related to the crisis (Figure 1.15). For instance, inflation is likely to go up temporarily as prices in hard-hit activities reverse their decline last year with the easing of restraints.6 However, there are several upside risks. A combination of possible negative supply-side effects (for instance related to higher operating costs due to virus containment regulations, shortages of key components, such as semiconductors, due to disruptions to global value chains, a desire to make up for past losses in revenues, or muted competition as a result of increased bankruptcies) could push up inflation by more than projected. Similarly, if private consumption increases more quickly than expected in many economies (for instance due to consumption out of accumulated saving – see below, or large fiscal stimulus, particularly in the United States), the resulting demand pressures, including on commodity prices that are assumed to remain unchanged in the projections (Annex 1.A.), could push inflation significantly higher than projected. In emerging-market economies, upside risks to inflation include further exchange rate depreciations and food and energy price increases that could de-anchor inflation expectations, especially in countries where central bank credibility has already been weakened.

In the longer term, inflation developments will depend on monetary policy actions and the structural factors that prevailed prior to the crisis. Prolonged high or rising inflation is unlikely if central banks take necessary measures to keep inflation expectations anchored at target and if structural changes that limited pressures on aggregate inflation in the advanced economies during the past three decades continue. These changes relate to the production and distribution of goods and services, firms’ business models and demand structure (OECD, 2020c). There is large uncertainty about their future evolution. In the absence of protectionist policies or a large-scale reshoring of manufacturing production motivated by strategic considerations, globalisation forces are likely to continue limiting upward pressures on prices in the advanced economies. However, the COVID-19 experience may encourage some reshoring.

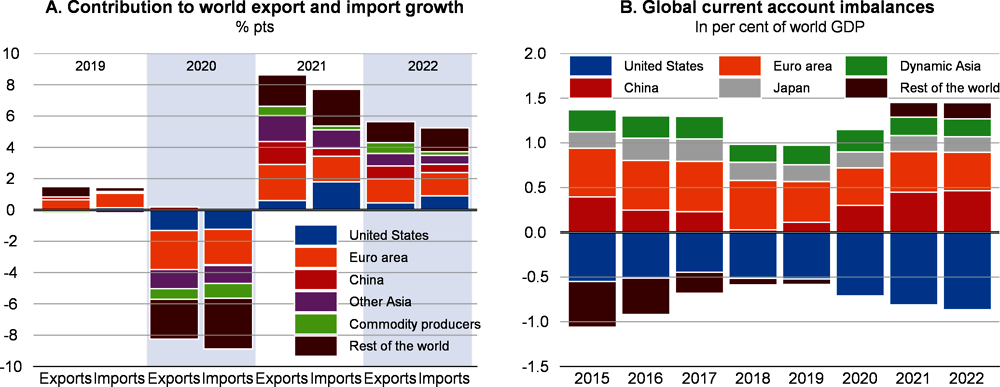

Trade prospects are improving, but imbalances may widen

World trade is projected to strengthen in 2021 despite persistently weak services trade. As long as the pandemic still requires sanitary restrictions and undermines travellers’ confidence, trade in services will remain subdued. However, merchandise trade should recover steadily. Overall, world trade volumes are projected to increase by close to 8¼ per cent in 2021, after falling by 8½ per cent in 2020, and by just under 6% in 2022 (Figure 1.16, Panel A). The booming demand for durable goods, combined with supply-side bottlenecks in international transportation, has pushed shipping costs up since June 2020 (Box 1.3). These cost pressures are expected to wane towards the end of 2021 as both demand and supply factors normalise due to the widespread rollout of vaccines. The demand for durable goods is likely to moderate once mobility restrictions will be eased and consumption patterns revert towards services. Bottlenecks in ports and terminals should also be relieved as sanitary restrictions are lifted. Global current account balances are projected to widen slightly over the projection period, but to remain moderate by historical standards (Figure 1.16, Panel B). The strong boost to domestic demand in the United States this year is expected to push up the current account deficit, from just over 3% of GDP in 2020 to around 4% of GDP in 2022. Higher commodity prices could also improve the external positions of many commodity producers, particularly if higher export revenues are only spent on imports slowly. National saving is projected to remain high in many countries in Europe and Asia with a long-standing external surplus, with the current account surplus in China rising to 2¾ per cent of GDP in 2022 from 2% of GDP in 2020.

There are significant upside and downside risks to the projections outlined above. Key uncertainties include: the epidemiological outlook and the pace of vaccine deployment; the extent to which household saving rates are normalised and accumulated “excess” savings in 2020 are spent; the health of companies once government support is scaled down; and the vulnerabilities that persist in many emerging-market economies and developing countries. In addition to these risks, which are discussed below, there are other long-standing issues that could affect the outlook. These include the potential implications of excessive risk-taking and private debt accumulation if adverse shocks occur, and the extent to which British and EU companies successfully adapt to the changes brought about by the free trade agreement between the European Union and the United Kingdom concluded in end-2020.

Significant uncertainty remains about the pace of vaccine deployment and the evolution of the virus

The baseline projections are conditional on the evolution of the pandemic, the pace at which vaccines are deployed throughout the world, and the economic impact of a gradual reopening of economies over time. The distribution of risks around these projections has become better balanced in recent months following the successful development and ongoing rollout of vaccines, but significant uncertainty remains.

On the upside, faster progress in deploying effective vaccines around the world and more effective efforts to suppress the virus before vaccinations are completed would enhance the pace at which containment measures can be relaxed and provide a stronger boost to the confidence and spending of consumers and companies. In a scenario of this kind, starting from the latter half of 2021, with household saving rates reduced by over 2 percentage points in the typical advanced economy, global output could be brought close to the path expected prior to the pandemic (Figure 1.17, Panel A). Global GDP growth would be raised substantially, to around 6½ per cent and between 5¾-6 per cent in 2021 and 2022 respectively.

On the downside, the key risk is that the speed of vaccine production and deployment will not be fast enough to stop the transmission of the virus or prevent the emergence of more contagious variants of concern that require new or modified vaccines. In such circumstances, confidence and private sector spending would be weaker than in the baseline, with some capital being scrapped. Stricter containment measures could need to be used again during the latter half of 2021, and substantial repricing could occur in global financial markets due to higher risk aversion (OECD, 2020d), pushing down equity and commodity prices and raising risk premia for emerging-market economies. In such a scenario, output would remain weaker than the pre-crisis path for an extended period, raising the chances of long-lasting costs from the pandemic (Figure 1.17, Panel A). World GDP growth could be lowered by close to ¾ percentage point in 2021 and 1½ percentage points in 2022, taking it to 5% and 3% respectively.

By the end of 2022, global real income in the downside scenario would be around USD 5 trillion lower than in the upside scenario, highlighting the substantial cost of failing to ensure rapid and complete vaccination around the world.

There are potential differences across countries and regions in the effects of these shocks (Figure 1.17, Panel B). In particular, the direct impact on domestic demand could be smaller in Asia-Pacific countries that have kept domestic COVID-19 cases at very low levels and maintained strict control of international borders, including Australia, China, New Zealand and some other small Asian economies. However, these countries remain exposed to fluctuations in world demand and financial market sentiment, and will benefit if borders can be reopened earlier for international travel.7 A second potential cross-country difference is between advanced and emerging-market economies. On the upside, the scope to spend from accumulated household saving is relatively high in many advanced economies, particularly the United States (see below). On the downside, the effects of a slower-than-expected vaccine rollout and risk repricing in financial markets are particular concerns in those emerging-market and developing economies in which vaccination deployment is not well advanced, including many in Latin America.

Policy settings also affect the impact of the shocks in the two scenarios. The upside scenario is conditional on the assumption that policy interest rates remain at their baseline levels and that there is no additional removal of discretionary fiscal support beyond that assumed in the baseline, although the automatic fiscal stabilisers are allowed to operate fully in all countries. Stronger growth helps to ease government debt burdens, with the government debt-to-GDP ratio declining by around 5 percentage points in the median advanced economy by the end of 2022. The downside shocks are cushioned by macroeconomic policies. The automatic fiscal stabilisers are allowed to operate fully in all countries, and policy interest rates are allowed to decline in many countries, although there is assumed to be a binding zero lower bound with policy rates remaining unchanged where they are already negative, and no additional unconventional policy measures are assumed. This affects the cross-country impact of the shocks, with real long-term interest rates declining in many emerging-market economies (despite higher risk premia), but rising in many advanced economies due to unchanged nominal interest rates and declining inflation.

Excess saving poses upside risks to household consumption

The projected sizeable increase in private consumption in 2021, partly reflecting pent-up demand from the last year, and sustained consumption growth in 2022 are predicated on projections of robust disposable income growth and, in many countries, on the gradual normalisation of saving rates towards pre-crisis levels (Figure 1.18, Panel A). In the OECD countries as a whole, private consumption is projected to rise by around 5½ per cent this year and 4¾ per cent in 2022. The near-term projected increase in consumption is consistent with survey evidence of rising household spending intentions (Figure 1.19) and improving consumer confidence. In Canada, spending growth is expected to outstrip income growth over the next 12 months by all income groups, with the gap between spending and income wider than typically seen prior to the pandemic. In the euro area, plans to make major purchases have risen in recent months, but – with the exception of the highest income quartile – the plans remain below pre-pandemic levels; plans to save over the next 12 months by all income quartiles also remain higher than prior to the crisis.

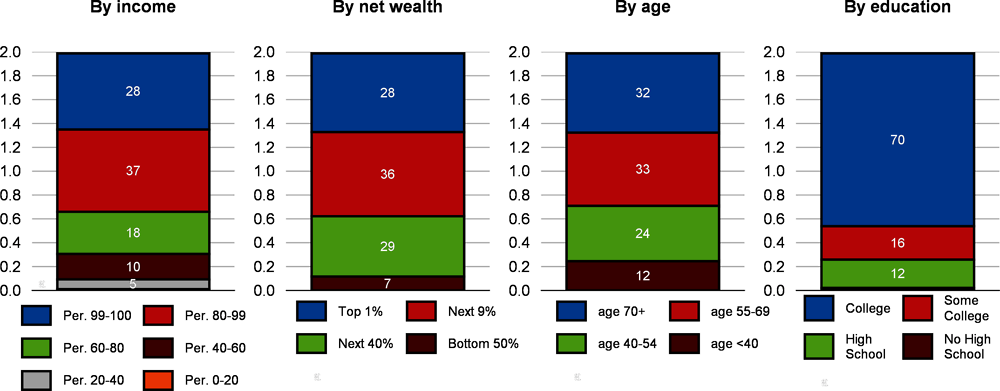

The accumulation of excess savings in 2020 poses an upside risk to global growth. In 2020, household disposable income declined by less than GDP, and even increased in some countries due to extraordinary government support, while consumption of many services was restricted.8 Consequently, household saving rates increased to record highs in most OECD countries (Figure 1.18, Panel A) and households accumulated large sums of bank deposits well above past deposit accumulation trends (Figure 1.18, Panel B).9 Even using only a tenth of these “excess” savings to fund additional private consumption in 2021 could boost GDP growth in this year by between ⅓-¾ percentage point in the G7 economies and the euro area as a whole.

However, there are several reasons why the accumulation of household financial assets last year may have only a limited impact on private consumption (as assumed in the projections discussed above). The overall propensity to consume out of wealth, which includes bank deposits, is not very high. It tends to be even lower for wealthy and high-income people (Armpudia et al., 2020; Fisher et al., 2020), who have largely driven excessive savings in 2020. In the United States, the largest increase in bank deposits was among high-income, wealthy and older individuals, even though people from the middle and lower parts of income and wealth distributions also increased their bank deposits (Figure 1.20).10 Similar patterns are observed in the large European economies.11 High-income and wealthy households are more likely to use accumulated deposits to invest in bonds, equities or real estate rather than to spend on consumer goods and services, especially if the increase in deposits resulted from the sale of assets during the pandemic. If this were to be the case on a large scale, asset prices would be more likely to increase further than consumption. In the case of many services, including travel, bars and restaurants, tourism and entertainment, possibilities to make up foregone consumption in a given period are limited, even though households can buy higher-quality services. Thus, it is unlikely that strong growth in demand would be sustained for a prolonged time. Also, high-income households, whose consumption declined the most in 2020, could sustain consumption of such services out of their future income. Finally, some households could chose to pay back debt from accumulated assets rather than to increase consumption.

Companies have resisted well, but performance has varied across sectors and company sizes

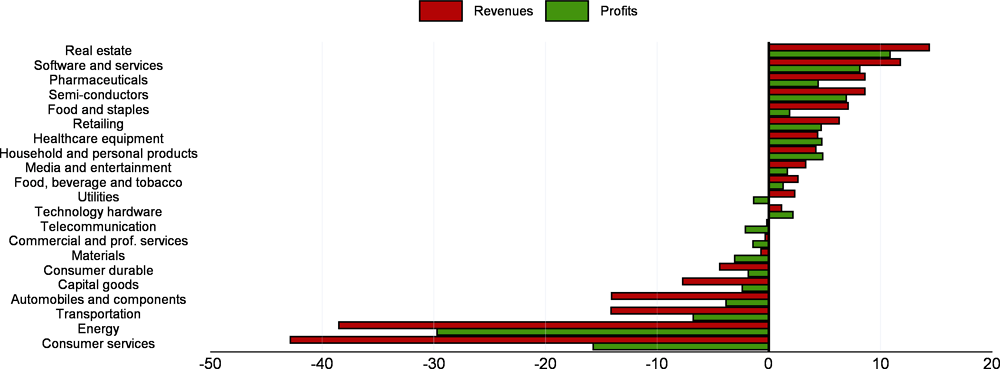

The COVID-19 shock has had a negative impact on corporate profitability and leverage. A preliminary analysis based on a large sample of non-financial companies in OECD and major non-OECD emerging-market economies suggests that revenues and profits dropped by 2% for the median firm, debt and leverage ratios increased, and the interest coverage ratio (ICR), a key solvency metric, declined by roughly 2% (Figure 1.21, Panel A).12 However, the (effective) interest rates paid on debt by companies decreased and debt maturity increased slightly, suggesting that monetary and prudential policy support was effective in keeping debt servicing costs low and stable for relatively large corporations. There was also a sharp increase in short-term assets, of a magnitude close to the observed growth in debt. This suggests that a sizeable portion of the funds raised by firms currently sits on corporate balance sheets as liquid, short-term investments (cash or equivalent).

This general picture conceals significant heterogeneity across different sectors and types of firms. Revenues and profits dropped sharply for firms operating in the energy sector, reflecting depressed oil prices during most of 2020, and in contact-intensive consumer services, such as hotel and restaurant chains, casinos and gaming, and cruise lines (Figure 1.22).13 In those industries, the median firm lost up to 30% in revenues and 50% in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) compared with fiscal year (FY) 2019. The income shock was also sizeable in the transportation and automobile sectors. As a result, the evolution of profits, leverage and solvencies for firms in those sectors was much more dramatic than for the median firm in the economy (Figure 1.21, Panel B). In contrast, firms operating in software services, pharmaceuticals, healthcare or retailing expanded substantially in FY 2020, in terms of both revenues and profits. The performance of firms also varied with the size of firms, with preliminary evidence suggesting that smaller firms suffered more than larger ones (see below).

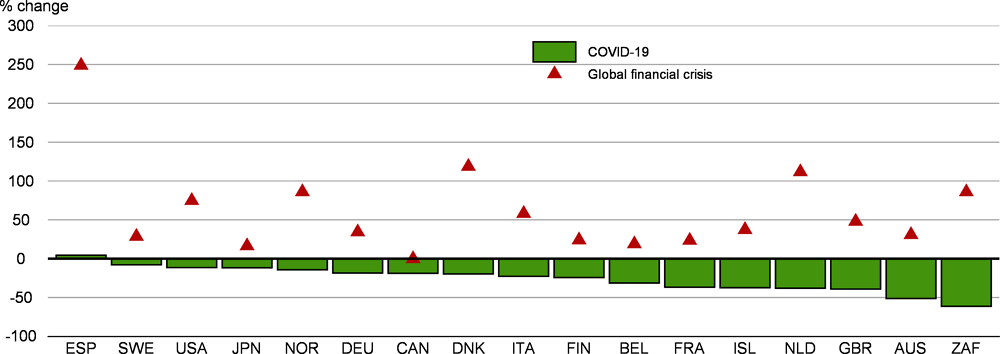

Financial stress has been contained, for now. The sectoral asymmetry of the shock, along with the ability of firms to raise cash quickly, has limited the level of financial stress in the corporate sector. In spite of the strength of the COVID-19 shock, the number of firms “in distress” – measured by the share of firms with either negative equity or an ICR below 1 in the sample – has been stable.14 This finding is in line with the general slowdown in bankruptcies among both large and small firms observed in OECD countries, helped by public sector support through loans, credit guarantees and tax deferrals, and temporary changes to insolvency regimes (Djankov and Zhang, 2021).15 So far, the number of bankruptcies has remained lower than in the global financial crisis (Figure 1.23), and, in some advanced economies, it was even lower than in the years preceding the COVID-19 crisis.

It is too early to tell whether this relatively benign picture will persist. The sample of firms for which up-to-date financial information is available currently tilts towards medium-sized and large firms, with sizeable buffers and a stable access to credit.16 A complete picture will be available only once more firms, in particular smaller and more fragile firms, report their financial statements. Other important challenges, related to debt sustainability, debt overhang and corporate “zombification”, could also arise in the longer term (Box 1.4). Still, this “hibernation” already contrasts sharply with previous crisis episodes, and hints at the effectiveness of policy support when it comes to avoiding excessive corporate stress in the short run (Cros et al., 2021). Although the channels through which policy intervention ultimately supported the non-financial corporate sector remain to be clarified, there seems to be a negative correlation between estimates of fiscal policy support and the increase in the number of firms in distress at the country level.17

Considerable uncertainty surrounds the situation of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which account for the bulk of the employment in OECD countries and are over-represented in contact-intensive industries. Preliminary evidence suggests that SMEs have been more affected by the effects of COVID-19 than other firms (Chetty et al., 2020), and that policy support has been crucial in keeping them afloat (OECD, 2020e; Gourinchas et al., 2020). Nevertheless, little is known about their actual financial position. Most of the analysis on SMEs currently relies on simulations and points to larger liquidity and solvency issues for small firms than for large ones, and to a potentially large number of near-term insolvencies (Diez et al., 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic raises three medium-term challenges for the corporate sector: (i) the debt overhang problem, and its consequence for corporate investment; (ii) the financial stability implications of the rapid debt build-up; and (iii) the emergence of so-called “zombies” in the corporate sector. This box discusses them briefly.

Debt overhang and investment

The debt overhang is a key source of concern as high corporate debt tends to reduce investment in the aftermath of economic crises, with negative implications for the recovery (Kalemli-Özcan et al., 2019; Barbiero et al., 2020; Demmou et al., 2021). In the sample of mostly medium-sized and large firms used for the analysis (see the main text), the aggregate level of capital expenditures decreased by almost 7% in fiscal year (FY) 2020 compared to FY 2019, in line with the aggregate business (non-residential) investment slowdown observed in advanced and emerging-market economies (Figure 1.24). Investment in sectors that were hit hard (energy, consumer services and transportation) contracted drastically. In contrast, firms operating in healthcare equipment, utilities, software services, telecommunications and pharmaceuticals expanded capital expenditures.1 On average, a percentage point increase in the equity (asset) leverage ratio between 2019 and 2020 was associated with a 2% (5%) drop in capital expenditures, suggesting that the persistence of a debt build-up strategy will ultimately weigh on investment in the medium term.

Level and quality of corporate credit

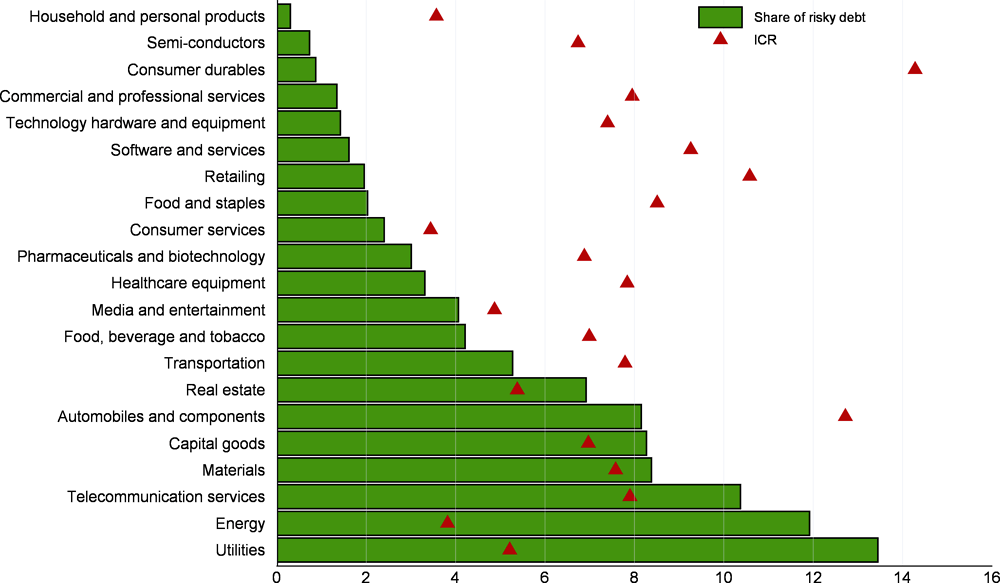

Rising and lower quality corporate credit in many advanced and emerging-market economies was already a cause for concern before the COVID-19 crisis (OECD, 2020f). Although swift and strong policy support has allowed firms to borrow extensively, it has also amplified debt concerns. Around 30% of the non-financial corporate debt stock currently rated by S&P sits in entities rated as “speculative”, and 40% in entities with only a BBB rating, the lowest rating in the investment grade category (around USD 5 and 8 trillion, respectively; Figure 1.25).2 Mirroring the resilience observed in the broader sample of firms, the share of distressed firms in the analysed sample of rated firms has also remained low and stable. In particular, the COVID-19 shock has had a limited impact on the sectors that have contracted most of the risky debt at the global level, such as utilities and telecommunications (Figure 1.25).3 The consumer services sector, which has taken the hardest hit and reported the lowest median interest coverage ratio (ICR) in FY 2020 among all industries, also represents only a small portion of the lower quality debt stock. Still, solvency challenges remain in several industries, especially with much corporate debt due to mature in 2024, at a time when policy interest rates may be higher than when some of the outstanding debt was issued.

“Zombification” in the corporate sector

The efficiency and size of public support to firms in the COVID-19 crisis has also reignited fears of “zombification”. By being too generous, policy support might actually keep some unviable firms alive – the so-called “zombies”, and valuable resources away from viable ones. Ultimately, this tendency could hinder the Schumpeterian creative destruction process and depress innovation, investment and growth. Preliminary evidence for France suggests that this concern has not yet materialised, and that the normal pattern of firm failures was unchanged in 2020 in spite of the support from policy (Cros et al., 2021).4 The peculiar nature of the COVID-19 crisis also implies that many firms could temporarily be classified as zombies, when they are in fact viable (Laeven et al., 2020). In the sample of mostly larger firms, the number of firms with an ICR below one – a standard criteria in the literature – is still relatively low.5 This backward looking analysis, however, does not preclude the future rise of new zombies, especially if consumer demand shifts permanently away from some goods and services but governments are reluctant to let some companies fail.

← 1. The investment increase in the retail industry is almost entirely due to the “internet and direct marketing retail” sector, and Amazon in particular.

← 2. The analysis here restricts attention to the 2 800 public and private non-financial companies operating in OECD countries and major (non-OECD) emerging-market economies with an active S&P issuer rating. The sample consists mainly of large publicly listed firms incorporated in advanced economies, but also includes private firms (30%) and/or firms in emerging-market economies (13%). Collectively, these firms represent USD 20 trillion of non-financial corporate debt. US firms account for 40% and firms in emerging-market economies for 20% of the USD 13 trillion of non-financial corporate debt currently rated either as speculative or BBB.

← 3. A notable exception to this pattern is the energy (i.e. oil) sector, which has suffered heavy losses and which accounts for most of the rating downgrades and debt restructuring deals over the past year (OECD, 2020f).

← 4. Using data on French firm failures in 2020, Cros et al. (2021) find that the same factors that predicted firm failures in 2019 – primarily low productivity and debt – were at work in 2020.

← 5. The inability to make interest payments from operating income – or an ICR below one – is a standard proxy used to identify zombies (Adalet McGowan et al., 2018; Acharya et al., 2019). Less than 2% of firms in the sample currently fall in this category (i.e. around 800 firms), and only 20% of those actually entered the pandemic as “zombies” (i.e. with an ICR that was already below one both in 2018 and 2019). In addition, the number of potential zombie firms, as well as the size of debt currently sitting in those entities, is limited.

Pandemic-related risks are still high in some emerging-market economies

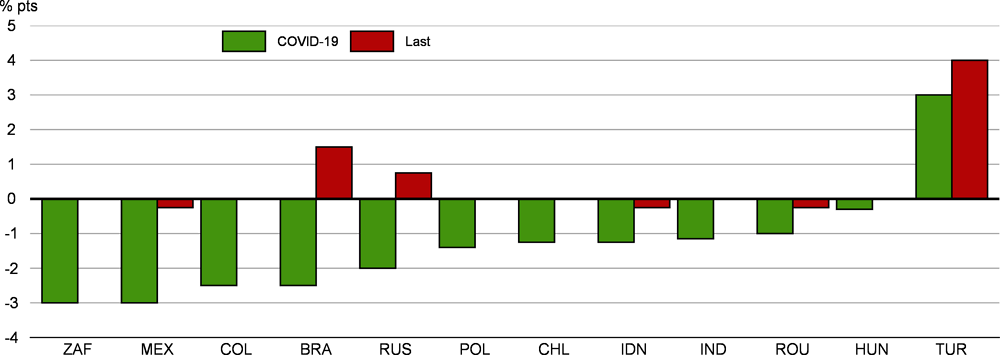

A pick-up in COVID-19 infections, the slow and uneven pace of vaccination, and the ensuing prolongation or strengthening of confinement measures have all weighed on economic activity in many emerging-market economies and aggravated existing vulnerabilities. While financial market stress is lower than a year ago in the majority of emerging-market economies and capital flows have largely reverted to pre-crisis levels, a number of internal and external risks remain.

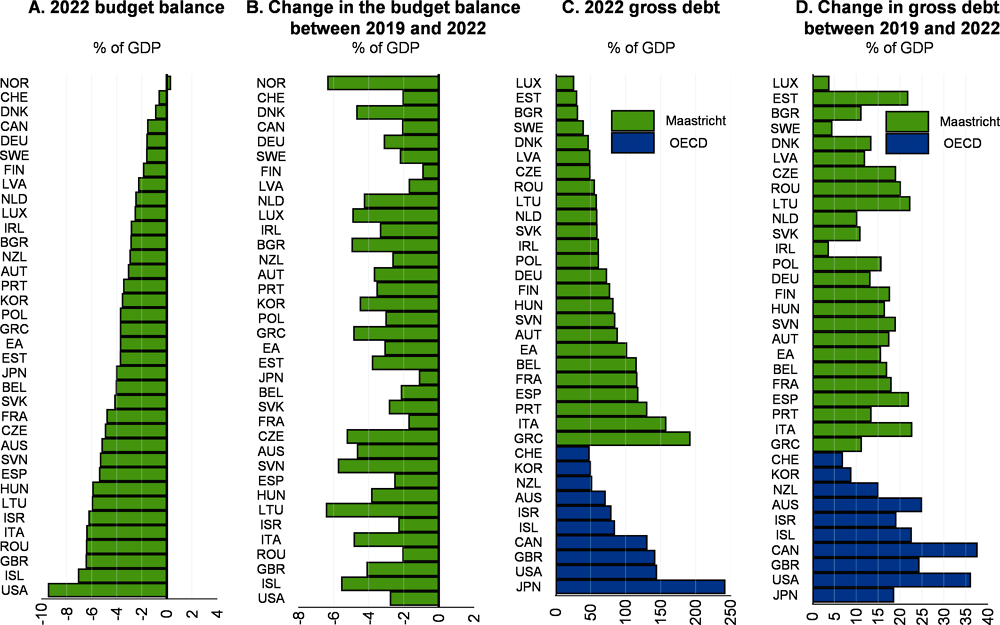

Government deficits and debt increased sharply in many emerging-market economies in 2020, primarily due to reduced tax revenues. Despite this fiscal deterioration, major emerging-market economies managed to issue more than USD 3.4 trillion debt in 2020 and sovereign ratings have been stable with a few exceptions (OECD, 2021c).18 Emerging-market economies in Asia, in particular China, India and Indonesia, accounted for about half of total emerging-market economy sovereign debt issuance in 2020, helped by their recovery and stronger fundamentals. However, low and lower-middle-income countries have continued to experience financing stress, leading to the extension until the end of 2021 of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative, the G20 effort to address debt problems in vulnerable economies. In several emerging-market economies, corporate debt has also increased substantially, in particular in China where it reached more than 160% of GDP in 2020.

The deterioration of the fiscal situation exposes emerging-market economies to the risk of a surge in borrowing costs, the associated tightening of credit conditions, and exchange rate depreciations. Such risks differ, however, among emerging-market economies. In Brazil, the continuing need to provide support to hard-hit sectors despite limited fiscal space may increase financial market volatility. The increased exposure of the domestic banking system to government debt in South Africa may reduce credit supply for businesses and households, with ensuing negative implications for private investment. Negative effects for credit conditions and financial stability could be amplified by rising non-performing loans, following the end of the temporary easing of prudential regulations (for instance, in India and Mexico). In Argentina and Turkey, further weakening of the macroeconomic and institutional frameworks could elevate financial market stress.19

Emerging-market economies remain exposed to global shocks. Expectations of rising growth and inflation if upside risks materialise in the United States could push US bond yields higher, triggering capital outflows from emerging-market economies and increasing currency volatility, as seen in past episodes such as the “taper tantrum” in 2013. Rapidly increasing sovereign debt in Brazil and South Africa, and the large foreign ownership of corporate and public debt in Indonesia, make some sectors of these economies vulnerable to such capital flow reversals. However, a generally increasing share of local-currency bonds in total sovereign debt over the past decade reduces the exchange rate exposures of many emerging-market economies.20 Still, the large presence of foreign investors in these bond markets makes emerging-market economies sensitive to swings in global risk sentiment, as was observed at the peak of the COVID-19 crisis (Figure 1.26, Panel A; Borri, 2018; Bertaut et al., 2021). In countries such as India, where current account deficits as a share of GDP declined, external debt is low and international reserves are high, future capital outflows should have less negative effects than during the “taper tantrum” (Figure 1.26, Panel B).21 Sound monetary policy frameworks, flexible exchange rate regimes and access to liquidity buffers provided by international financial institutions also continue to reduce the vulnerability of emerging-market economies to external financial shocks.22 In this context, the proposed Special Drawing Rights allocation of USD 650 billion by the IMF would buttress the global safety net and help countries with high external financing needs.

If an eventual rise in US interest rates is accompanied by stronger economic growth in the United States and other large economies, any negative financial market spillovers could be offset, at least partially, by stronger global trade demand. Mexico and other Latin American economies would benefit in particular from growing import demand from the United States given their strong trade links (Figure 1.26, Panel C). In addition, Colombia, Costa Rica, Turkey and other emerging-market economies relying heavily on tourism and services exports would benefit from an earlier-than-expected reopening of borders enabled by improved vaccination coverage. An increase in commodity prices associated with stronger global growth, particularly led by China, would put pressure on the external balances of net commodity importers such as India and Turkey, with opposite effects on net commodity exporters, including Brazil, Chile, Russia and South Africa.

The top policy priority is to ensure that all resources necessary are used to produce and fully deploy vaccinations as quickly as possible throughout the world to save lives, preserve incomes and limit the adverse impact of containment measures on well-being. International policy co-ordination is essential to increase the gains from national policy actions to tackle the pandemic, enhance resilience and ensure a strong and inclusive recovery.