Assessment and recommendations1

Spain’s economic recovery, underway since 2013, has been one of the strongest in the OECD thanks to a wide-ranging agenda of structural reform (Box 1), highly expansionary euro area monetary policy, easier fiscal policy, and significant repair of the banking system. Dynamic growth and wage moderation have led to strong employment gains, bringing down unemployment from very high levels and providing consumers with more income. Exports have grown strongly despite weak global markets, reflecting improving wage competitiveness and have helped turn a current account deficit into a surplus. Further economic growth at a pace above 2% annually is likely in the short term.

Banking sector

To restore financial stability, the authorities launched a reform programme with the support of the European Union (EU) in 2012, including a EUR 100 billion loan facility (of which only EUR 40 billion was used). The programme identified weak banks via a comprehensive asset quality review and independent stress tests, required banks to address their capital shortfalls (restructuring them if needed), and shifted state-aided banks’ real estate loans to a newly created asset management company (SAREB). The assets transferred to SAREB accounted for 10% of GDP and 3% of banking assets (Medina Cas and Peresa, 2016) and reduced the aggregated banks’ non-performing loan (NPL) ratio by around 1 percentage point. The programme also reinforced financial sector regulation, supervision and bank resolution to facilitate a more orderly clean-up and better promote financial stability.

Labour market

The 2012 labour market reform reduced the stringency of job protection legislation for permanent workers. It aimed to define more clearly the criteria justifying fair dismissal and reduced the amount of compensation following unfair dismissal. The 2012 reform gave priority to firm-level collective agreements over collective agreements at higher levels and relaxed the conditions for firms to opt-out more easily from higher level collective agreements (OECD, 2014a).

Product market

The Market Unity Law, adopted in 2013, aims to harmonise business regulation across all regions and create a truly single market. It simplifies business licensing requirements by increasing the use of notification procedures, reducing the need for prior authorisations, and ensuring that permits issued in one region will automatically be valid for other regions (OECD, 2014a).

Education

The Organic Law for Improvement of the Quality of Education (LOMCE), approved in 2013 and gradually implemented since the school year 2014/15, aims to reduce early school leaving and improve educational outcomes. It adopts new national external assessments of students; grants greater autonomy to schools in exchange for accountability, and modernises and develops the Vocational Education and Training (VET) system. In 2012, a new dual VET system was introduced which develops a model for certificates from the Ministry of Labour and another model for a degree from the Ministry of Education. National standardised exams have two positive goals: in primary education the aim is to identify students that face difficulties in order to provide additional support. At the end of compulsory education and upper secondary, the aim is to define the standards that students have to achieve in order to obtain a national degree.

Tax

The 2014 tax reform reduced the statutory income tax rates, in particular, for low-paid workers and simplified different deductions on labour earnings, reducing the tax wedge and the tax burden on labour. It eliminated distortive income tax benefits, like the house buying tax exemption. Also, it reduced the general corporate income tax rate from 30% to 25%. A tax on fluorinated gases was introduced in 2014. Some changes to the reform of the corporate income tax were approved in December 2016, as discussed below.

Pension

The 2011 and 2013 reforms raised the retirement age and reduced the replacement rate. Following the reforms, the pensionable earnings reference was revised and the amount of pension benefits will be linked to life expectancy in the future (OECD, 2015a).

Public administration

The commission on the Reform of the Spanish Public Administration (CORA) was established in 2012, to improve public-sector efficiency at all levels – central, regional and local – (OECD, 2014b). The reform, together with the Law for Rationalisation and Sustainability of the Local Administration in 2013, led to a large-scale drive to clarify the allocation of responsibilities across levels of government, reduce duplication and overlap across jurisdictions and limit the creation of new public entities or agencies at local level. The number of agencies (i.e. Entidades Dependientes del Sector Público) in the regional administration has been reduced by 34% between 2012 and 2016. A recent OECD report suggests that Spain has made progress in implementing the OECD recommendations from the first OECD Public Governance Review on the CORA (OECD, 2016a).

Looking ahead, maintaining the current pace of growth and increasing living standards will require continued reforms to consolidate the recovery of the economy and to improve the economy’s growth potential, which has fallen substantially. With public debt around 100% of gross domestic product (GDP) and with the deficit still close to 5% the scope for fiscal expansion is limited, which means that new spending measures should be as fiscally neutral as possible. It is nevertheless important to stimulate growth and productivity by shifting spending towards growth enhancing items, such as education, active labour market policies and research and development (R&D) which are all below peer countries and have substantially fallen since the crisis. Productivity gains, if shared via higher wages, will be instrumental for improving the well-being of all Spanish citizens and to make growth more inclusive.

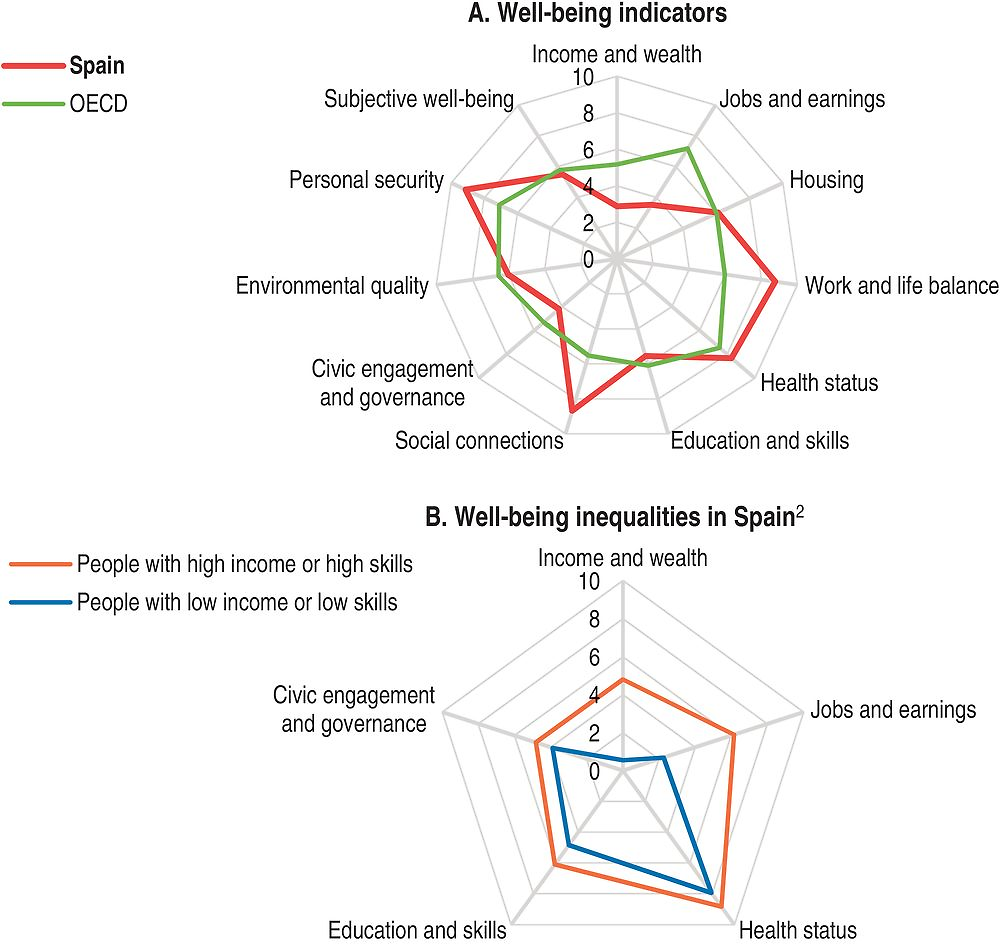

Spanish people enjoy very good social connections, good work-life balance, personal security and health conditions (Figure 1, Panel A). However, there are wider gaps in well-being relative to other countries in key areas including income, jobs, and education. Behind these averages there is also substantial heterogeneity with some groups of the population fairing considerably worse than others, especially in key areas including income and jobs (Figure 1, Panel B).

← 1. Each well-being dimension is measured by one to four indicators from the OECD Better Life Index set. Normalised indicators are averaged with equal weights. Indicators are normalised to range between 10 (best) and 0 (worst) according to the following formula: (indicator value – minimum value)/(maximum value – minimum value) × 10.

2. The panel shows well-being outcomes in various dimensions for people in Spain with different socio-economic background. In the dimensions of “income and wealth”, “health” and “civic engagement and governance” data refer to people with an income belonging to the top (/bottom) quintile of the income distribution. In “jobs and earnings” data refer to people with the highest (/lowest) educational attainment (i.e. ISCED 5/6 versus ISCED 0/1/2) or with gross earnings belonging to the top (/bottom) quintile of the distribution. In “education and skills” data refer to people with a score belonging to the top (/bottom) quintile of the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status. Outcomes are shown as normalised scores on a scale from 0 (worst condition) to 10 (best condition) computed over OECD countries, Brazil and the Russian Federation.

Source: OECD (2016), OECD Better Life Index, www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org.

The crisis has left scars that hurt well-being, the most visible being still very high unemployment, poverty and inequality. Bringing more people back to work is crucial, but Spain has also to focus on the quality of jobs created to ensure that the benefits of growth are more widely shared and to create better opportunities for new generations. The labour market is characterised by a high share of temporary workers, mostly youth and many with low wages. Youth and the low-skilled suffer especially from unemployment, and long-term unemployment is very high. These factors risk entrenching inequalities, hurting future growth and social cohesion.

Against this background the main messages of this Survey are:

-

The Spanish recovery has taken hold, but further sustained rises in living standards will depend on improving investment, skills, and productivity. Policies need to ensure that the benefits of the recovery are enjoyed by all, and the reform momentum should continue to achieve that goal.

-

Low productivity reflects in part poor skills, overreliance on temporary workers, low business innovation, inefficient allocation of capital to low productivity firms, and high barriers to starting and growing a business.

-

The crisis and the ensuing high unemployment have resulted in poverty and income disparities. Making growth more inclusive will require further reducing unemployment, better policies to reduce poverty and improving the quality of jobs via better skills, training and job matching.

The economic recovery is set to continue at a healthy pace

Spain recorded very robust GDP growth of 3.2% in 2015, up from 1.4% in 2014, supported by expansionary monetary policy, low oil prices, a looser fiscal stance and the depreciation of the euro. The banking sector reform helped to stabilise the financial sector contributing to a pick-up in credit growth by improving banks access to market funding and by avoiding a disruptive and disorderly unwind of a significant part of the financial sector (Box 1). A relaxation of the fiscal stance in 2015-16 supported demand.

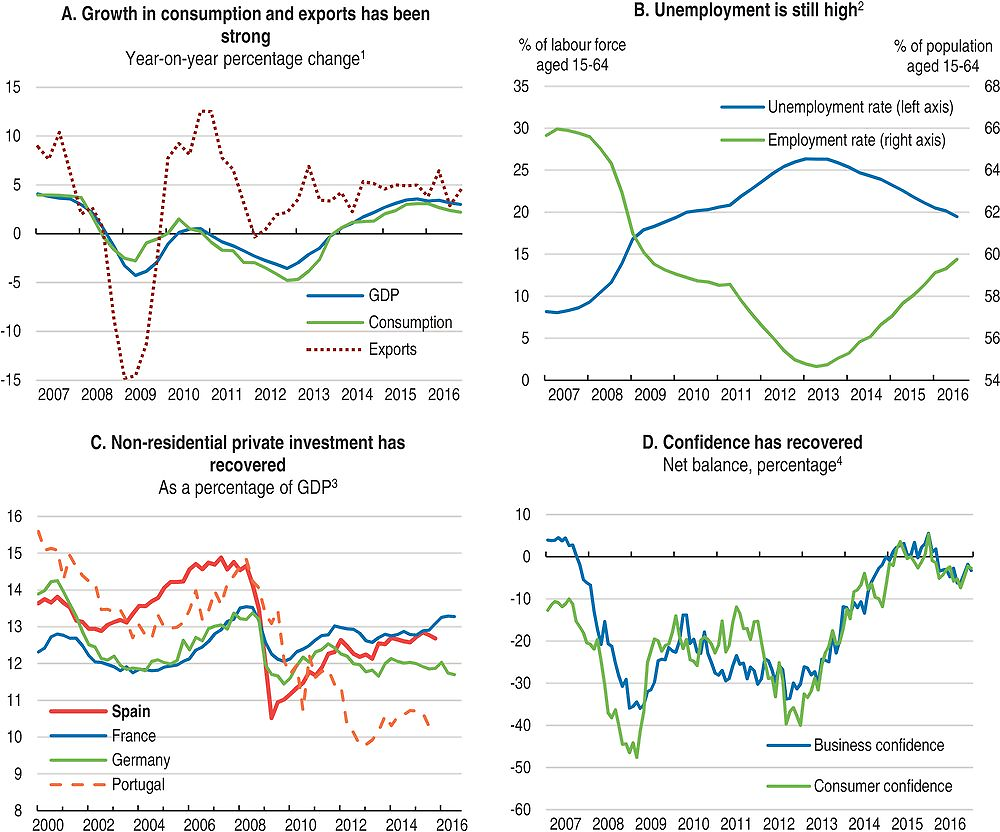

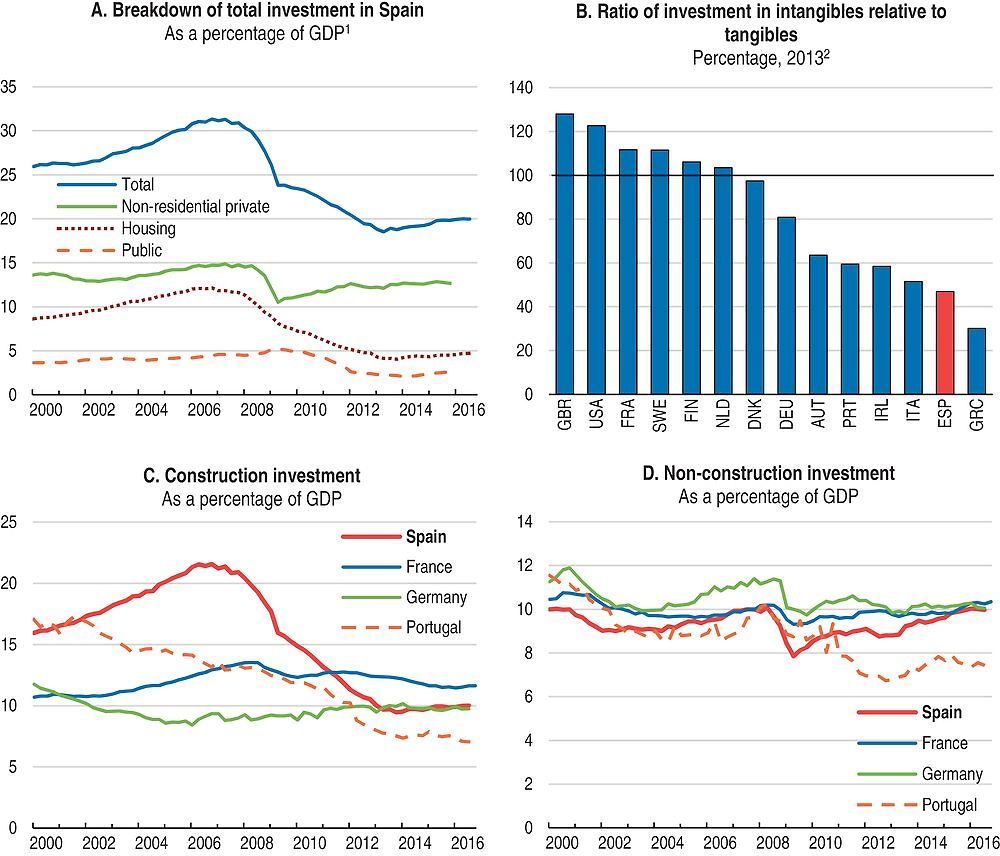

Consumption has been particularly strong, boosted by rising real disposable incomes, led by employment gains, tax reductions, falling prices, low oil prices and easy financial conditions (Figure 2, Panels A and B). Investment has picked up as financing conditions have kept improving and confidence strengthened (Figure 2, Panels C and D). Although total investment remains below pre-crisis levels, it is mainly due to a substantial fall in construction investment and to a lesser extent falls in public investment (Figure 3). On the other hand, equipment investment has been very dynamic in recent years and is already very close to pre-crisis levels. Exports are benefitting from gains in international competitiveness.

1. In real terms.

2. Data refer to population aged between 15 and 64.

3. Data refer to total investment minus government and housing investment. Since data for housing investment for Spain and Portugal may also include government housing, the series for non-residential private investment may be underestimated.

4. Net balance of answers to surveys taking the value between -100% (unfavourable) and +100% (favourable). Business confidence is calculated as an unweighted average of the confidence indicators for manufacturing, construction, retail trade and services (excluding retail trade).

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), February; OECD (2017), OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database), February; and OECD (2017), Main Economic Indicators (database), February.

← 1. The OECD aggregate is calculated as the unweighted average of the data shown.

Source: OECD (2016), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), December.

The job market was devastated during the crisis, but is gradually recovering. Employment is rising at about 3% a year. The unemployment rate has come down substantially from its peak of 26% in 2013, but it remains high at nearly 19%; youth unemployment is double than that (42.7%). Long-term unemployment has also come down rapidly from its 2014 peak, but is still high. Persistent unemployment may be eroding skills and increasing social alienation. The labour market is characterised by a high share of temporary workers (25.7% in 2015) and part-time work increased during the crisis and currently stands at 15.2%, more than half of it being involuntary. Temporary and part-time workers suffer from periods of unemployment and under employment, which reduces their incomes and raises poverty (OECD, 2015b).

Economic growth is projected to reach 3.2% in 2016 and then continue at an annual pace above 2% in 2017 and 2018 (Table 1). Domestic demand will continue leading the recovery. Private consumption is set to remain strong on the back of further employment gains, as the reforms from previous years continue to bear fruit. Continued favourable financing conditions will extend the nascent pick up in business and housing investment. Inflation will pick up but pressures should remain moderate due to still high unemployment. Growth is set to somewhat slow in 2017 and 2018 as the pace of growth of domestic demand eases, and some factors that have contributed to boost consumption, such as low oil prices and lower taxes, recede. Export growth is expected to somewhat moderate due to weak demand in export markets and anaemic world trade.

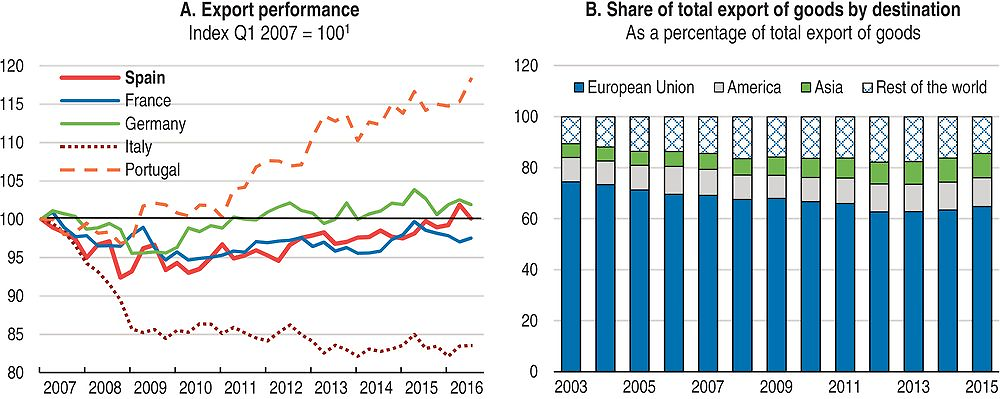

Risks stem from internal and external factors. Domestically, it may be difficult for the minority government to legislate further bold reforms needed to boost growth sustainably. Slowing global trade growth (Haugh et al., 2016) could further undermine exports, which have been an important driver of the economic recovery, especially if Spain’s international competitiveness were to erode. Renewed turbulence in international financial markets could damp private sector confidence and raise the cost of public-debt servicing. Spain exposure to “Brexit” (i.e. the exit of the United Kingdom from the EU) is estimated to be moderate (OECD, 2016b). Stronger demand from Europe, Spain’s main export destination, could boost growth more than projected, as could higher construction investment, which has so far been tepid in the wake of the housing collapse. Economic prospects are also subject to medium-term uncertainties, the probabilities and consequences of which are difficult to quantify in terms of risks to the projections (Box 2).

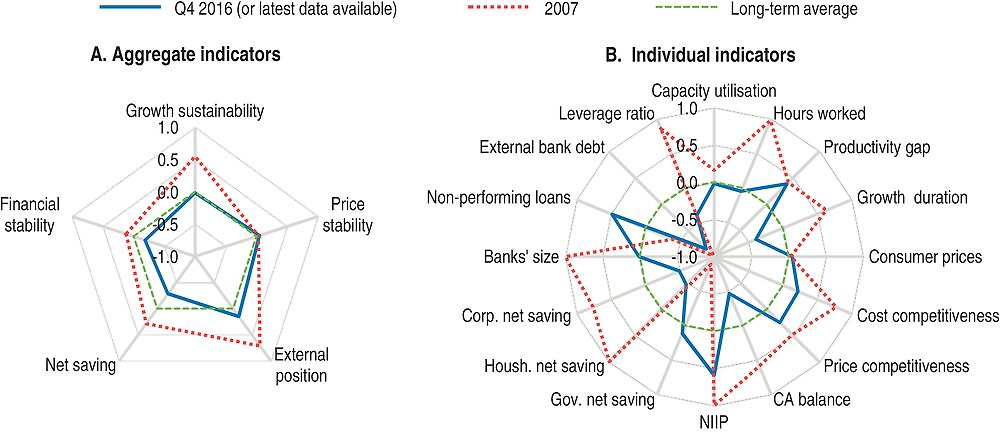

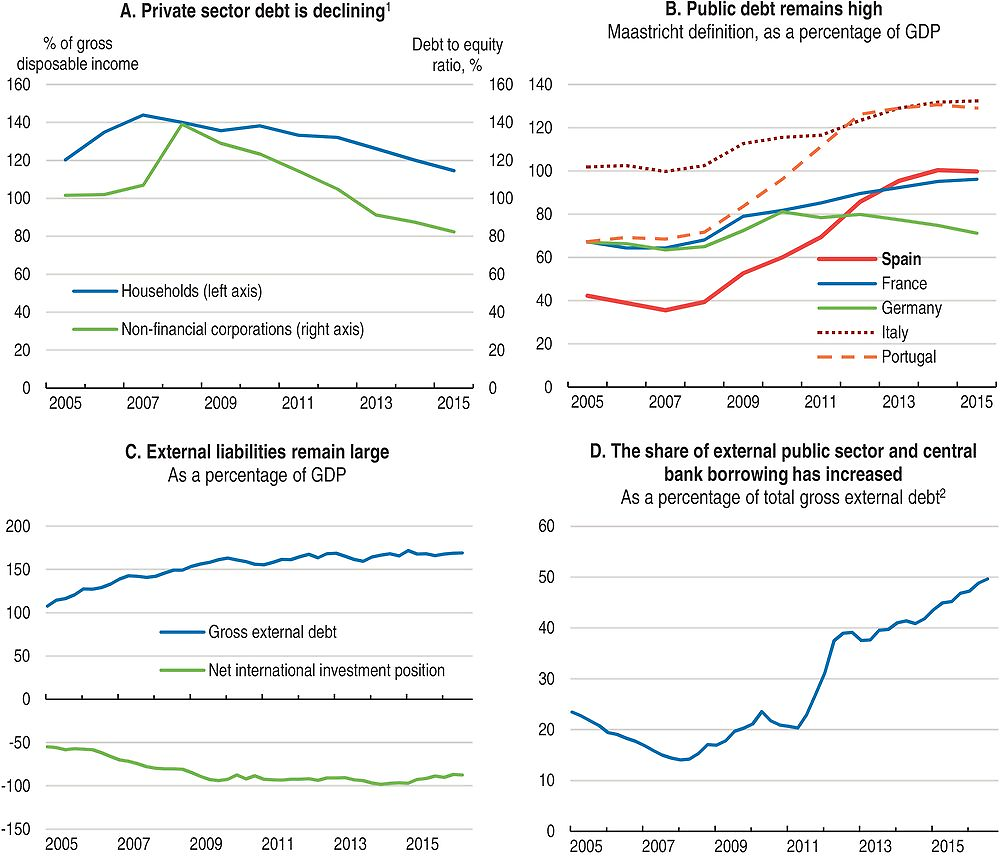

Macro-financial vulnerabilities have decreased since 2007 (Figure 4). The banking sector has become significantly stronger and private sector indebtedness is declining (Figure 5, Panel A). However, Spain faces high public and external debt (Figure 5, Panels B and C). In particular, Spain’s negative net international investment position at nearly 90% of GDP is large in historical and international perspective (Banco de España, 2016a). The bulk of the external liabilities is public debt and central bank borrowing, but risks are mitigated as public debt is mainly long-maturity (Figure 5, Panel D).

1. Each aggregate macro-financial vulnerability indicator is calculated by aggregating (simple average) normalised individual indicators. Growth sustainability includes: capacity utilisation of the manufacturing sector, total hours worked as a proportion of the working-age population (hours worked), difference between GDP growth and productivity growth (productivity gap), and an indicator combining the length and strength of expansion from the previous trough (growth duration). Price stability includes headline and core inflation (consumer prices), and it is calculated by the following formula: absolute value of (core inflation minus inflation target) + (headline inflation minus core inflation). External position includes: the average of unit labour cost based real effective exchange rate (REER), and consumer price based REER (cost competitiveness), relative prices of exported goods and services (price competitiveness), current account (CA) balance as a percentage of GDP and net international investment position (NIIP) as a percentage of GDP. Net saving includes: government, household and corporate net saving, all expressed as a percentage of GDP. Financial stability includes: banks’ size as a percentage of GDP, the share of non-performing loans in total loans, external bank debt as percentage of total banks’ liabilities, and capital and reserves as a proportion of total liabilities (leverage ratio).

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2017), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), February; OECD (2017), Main Economic Indicators (database), February; OECD (2017), OECD National Accounts Statistics (database), February; Banco de España (2017), “Statistical Bulletin, 01/2017”, January; and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

1. Debt is calculated as the sum of the following liability categories, whenever available/applicable: currency and deposits, securities other than shares (except financial derivatives), loans, insurance technical reserves and other accounts payable. Households also include non-profit institutions serving households.

2. Public sector borrowing refers to general government debt.

Source: OECD (2017), “Financial Dashboard”, OECD National Accounts Statistics (database), February; OECD (2017), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), February; and Banco de España (2017), “Statistical Bulletin, 01/2017”, January.

The current account improvement in recent years is in part structural, due to improved competitiveness, a greater internationalisation of Spanish firms and wider geographical diversification of exports (Figure 6), but is also due to temporary factors, such as depressed domestic demand in the recession, especially investment and lower oil prices (Banco de España, 2016a; European Commission, 2016a). Moreover, there has been a reduction in the net international debt position as a share of GDP, albeit moderate, due to an increase in the market price of external liabilities. A prolonged period of large current account surpluses will be needed to put it on a firmly declining path. This adjustment will depend on sustained competiveness gains stemming from faster productivity growth, innovation and attracting more foreign direct investment (Chapter 2).

1. Export performance is the ratio of export volumes to export markets for total goods and services.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), February; and INE (2017), “Main foreign trade results”, INEbase, National Statistics Institute, January.

Bolstering the financial sector to raise credit growth

The banking system is stronger, but some challenges remain

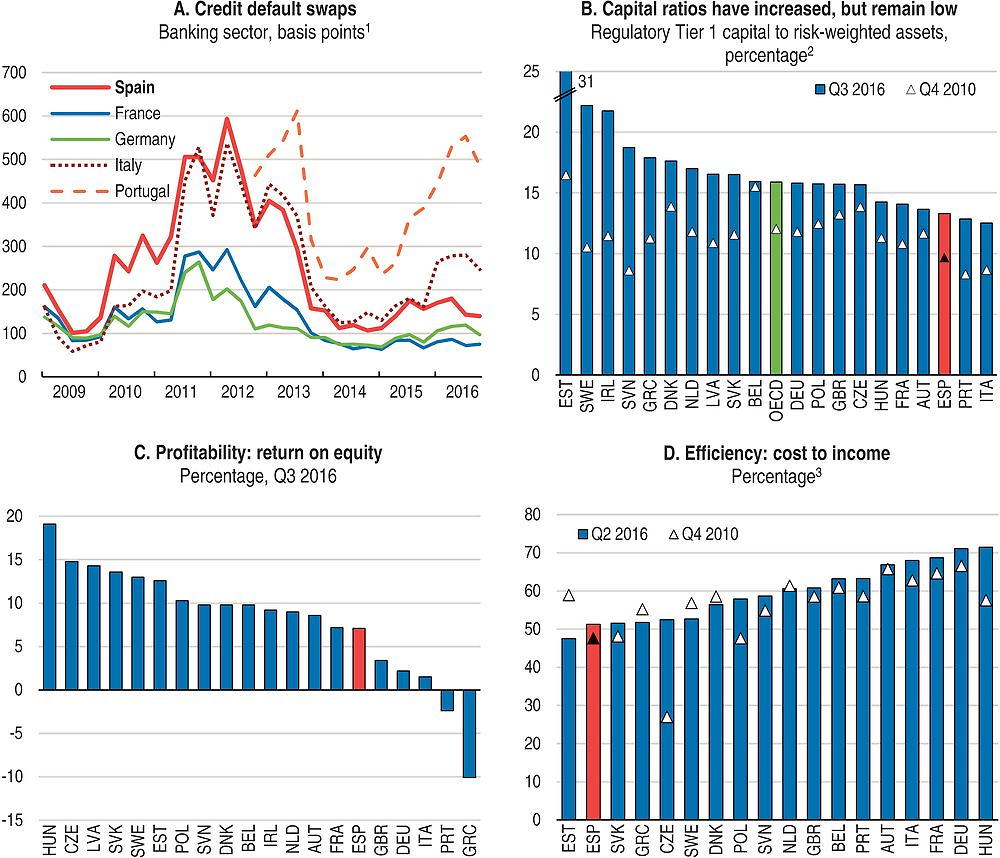

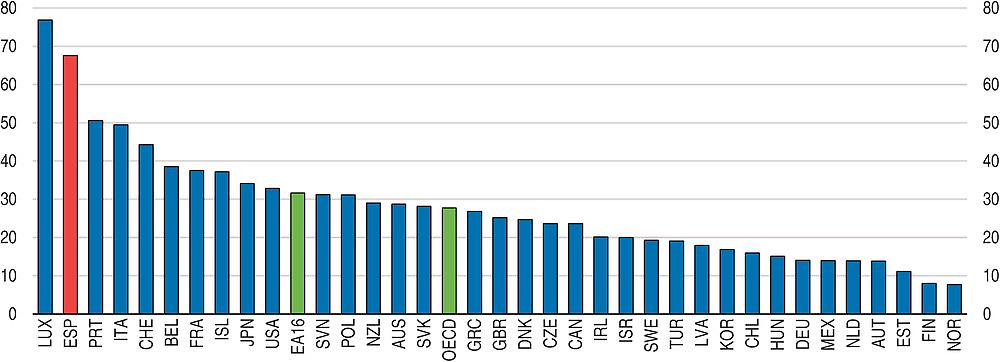

Substantial restructuring and the economic recovery have materially strengthened the banking system. In the European Banking Authority (EBA) stress tests of July 2016 the six largest Spanish banking groups comfortably met capital requirements. Credit default swaps have fallen sharply since the peak, but are above those in France and slightly above those in Germany; capital ratios have risen, but are still below OECD average; and profitability is low as in the other euro area countries (Figure 7, Panels A, B and C). Cost-to-income ratios are low and have fallen, following the downsizing of infrastructure and staff (Figure 7, Panel D), but there is still scope for some consolidation to support profitability. Spanish banks still have a large number of bank branches (Figure 8).

1. Five-year senior debt, mid-rate spreads between the entity and the relevant benchmark curve; end of quarter data. For Spain the series shown is an average of three banks – Banco Popular Español, Banco Santander and BBVA; for other countries the number of banks used in the calculation depend on data available.

2. Q2 2016 instead of Q3 2016 for France, Greece, Italy and the United Kingdom. The OECD aggregate is an unweighted average of the latest data available for 33 OECD countries.

3. Data refer to domestic banking groups and stand-alone banks.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream; IMF (2017), Financial Soundness Indicator (database), International Monetary Fund, February; EBA (2017), “Risk Dashboard: Data as of Q3 2016”, European Banking Authority, January; and ECB (2017), “Supervisory and prudential statistics: Consolidated banking data”, Statistical Data Warehouse, European Central Bank, February.

← 1. 2013 for the United Kingdom. The euro area aggregate (EA16) refers to euro area countries that are also OECD members and it is calculated as an unweighted average. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average of the data shown.

Source: World Bank (2017), World Development Indicators (database), February.

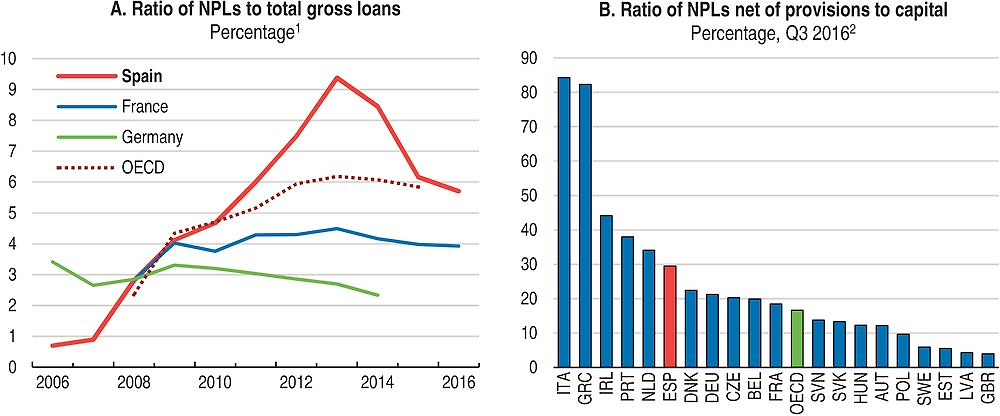

Non-performing loans (NPLs) have been declining as a share of total loans (Figure 9, Panel A), but are still somewhat above the OECD average. NPLs net of provisions amount to 30% of banks’ capital (Figure 9, Panel B) which is above the OECD average. Foreclosed assets, mostly also from the construction sector as a legacy of the crisis, still weigh on banks’ balance sheets and have slightly declined since 2012 (Banco de España, 2016b). The government and the Bank of Spain have put in place a number of measures to reduce non-productive assets from banks’ balance sheets, including transfer of NPLs to an asset management agency (OECD, 2014a and Box 1). They also increased provisioning requirements, imposed stricter criteria on forbearance and reformed the insolvency framework. Reforms in 2014 and 2015 to facilitate the restructuring of corporate and household debt (see below) should help to reduce further these unproductive assets in the medium term. NPLs are likely to continue to decline, but if they don’t further action may be needed to strengthen banks’ balance sheets.

1. Data for 2016 refer to Q3 2016 for Spain and Q2 2016 for France. As the OECD aggregate is an unweighted average of the data available at each data point, the countries included in the OECD aggregate vary over time.

2. Q2 2016 for France, Greece, Italy and the United Kingdom. 2014 for Germany. The OECD aggregate is an unweighted average of the latest data available for 33 OECD countries.

Source: IMF (2017), Financial Soundness Indicators (database), International Monetary Fund, February.

Credit growth is still weak

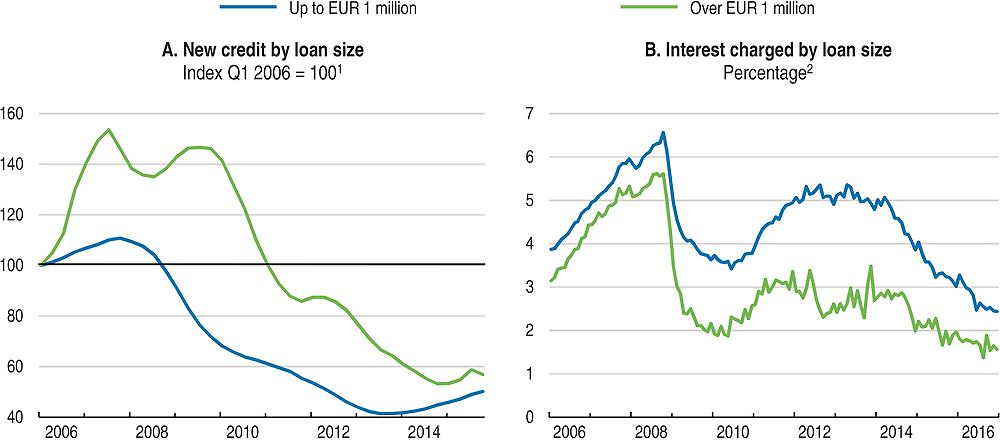

Lending to the domestic private sector fell substantially during the crisis and continued declining during the recovery, but it is now recovering (Figure 10, Panel A). Lending rates for all loan categories have fallen too (Figure 10, Panel B). Gross credit flows have shown positive growth rates in most segments since early 2014. One exception is new lending to large companies, which has declined recently. This reflects that large companies rely now more on market financing as the cost of market-based debt has declined more significantly than the cost of bank lending, in part thanks to the ECB asset purchase programme.

1. Quarterly figures are calculated as 12-month moving average of monthly data.

2. Data refer to new business loans other than revolving loans and overdrafts, convenience and extended credit card debt.

Source: Banco de España; and ECB (2017), “Financial markets and interest rates: Bank interest rates”, Statistical Data Warehouse, European Central Bank, February.

While access to finance for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) has eased significantly since 2013 both in terms of costs and the availability of funds as indicated by surveys on the access to finance by enterprises (ECB, 2016a), new loans to SMEs remain well below historical averages. Evidence from the Bank of Spain suggests lending is flowing to a greater extent than it did before the crisis to financially sounder and more productive firms (Banco de España, 2015; European Investment Bank, 2016). This is a welcome development. To strengthen future productivity lending needs to flow to newer, innovative and fast growing companies that often face additional constraints in accessing lending because of their lack of collateral or track record.

The Law on the Promotion of Business Financing adopted in 2015 aims to improve access to bank credit for SMEs and to develop alternatives to bank funding. As regards bank financing, the law seeks to strengthen the position of SMEs towards banks and to improve the regime of mutual guarantee funds. To mitigate information asymmetries, from now on banks have to notify SMEs at least three months in advance if a credit line is going to be cancelled or significantly reduced, as well as provide an assessment of the financial position of the SME and its creditworthiness to facilitate their search for alternative sources of financing. SMEs have also the right to request a credit assessment from their lenders. The law also intends to improve access to capital markets, principally the alternative stock market (MAB) and the alternative fixed-income securities market (MARF), which is welcome. Other measures to broaden the role of capital markets and help the banking and capital markets work more in tandem, as discussed below, could also help to improve the flow of credit to firms of all sizes and stages of development.

Access to credit by SMEs would be further improved by facilitating the assessment of their creditworthiness. In the context of the Law on the Promotion of Business Financing, the Bank of Spain has developed a standardised credit assessment for SMEs, as recommended in the 2014 OECD Economic Survey, which commercial banks are required to use when making their assessment of SMEs creditworthiness. In addition, SMEs have the right to demand this assessment. Commercial banks should be required to publish prominently that SMEs have the right to demand this assessment. These measures will allow SMEs to provide relevant standardised credit information to alternative lenders, reducing information asymmetries, and will facilitate their access to alternative sources of financing.

Fiscal policy

Managing limited fiscal space

Spain has made a considerable effort to reduce public deficits from 2012, when the deficit peaked at 10.5% of GDP, including financial assistance. This has resulted in substantial progress. The budget deficit is expected to decline to 4.6% of GDP in 2016 from 5.1% in 2015. The deficit reduction was driven by dynamic growth and some consolidation measures, including expenditure cuts for the central and regional government and recent amendments to the corporate income tax to make up for a loss in revenue. On the basis of current government plans, the fiscal deficit will be reduced below 3% by 2018. This fiscal path will provide modest support in 2017 and 2018 and debt will stabilise at around 100% by end-2018. While more demand is needed to raise growth further and reduce unemployment significantly, high debt and deficits limit the scope for further fiscal expansion.

Prudent fiscal management should be combined with reforms of the tax structure that raise long-term growth. There is room to improve the tax mix, as the structure of taxation remains tilted towards labour income which penalises growth and employment, as discussed below. Greater expenditure efficiency, as the government has recently committed to would also be welcome. The fiscal council will carry out a review of the general government spending in 2017. Moreover, a new public administration reform programme would yield EUR 900 million in savings over 2017-19. These measures could help to finance current spending needs, such as labour market programmes to effectively fight youth and long term unemployment.

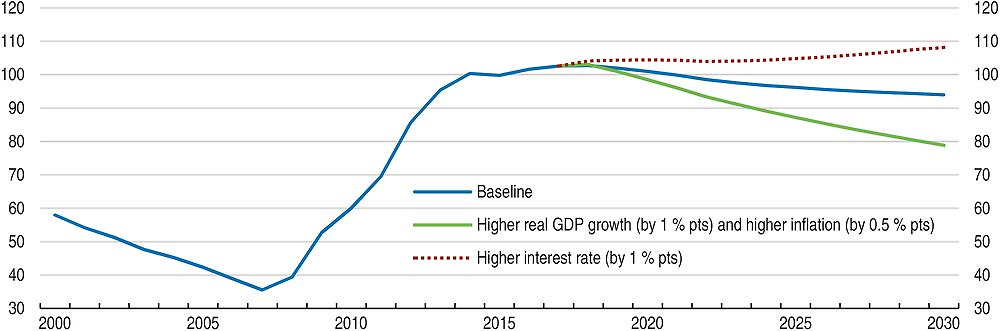

The new government should stick to its medium-term fiscal targets to allow a steady reduction of the debt ratio. Under current government plans, which assume medium-term nominal GDP growth of 3% a year from 2018 onwards and a primary surplus of 0.9% of GDP by 2022, public debt is projected to decline very slowly to 94% of GDP by 2030 (the baseline in Figure 11). In a positive scenario of higher growth, the debt ratio would fall further to 79% of GDP. However, the decline in public debt would not materialise and debt could reach close to 110% by 2030 (Figure 11) in an adverse alternative scenario where interest rates were one percentage point higher than the baseline assumptions. As noted above, renewed turbulence in international financial markets could damp private sector confidence and conceivably raise the cost of public-debt servicing.

← 1. The baseline consists of the projections for the Economic Outlook No. 100 until 2018. Thereafter assumptions are: real GDP growth progressively closing the output gap and from 2023 growing by 0.9% corresponding to the potential growth rate; a primary balance gradually reaching a surplus of 0.9% of GDP by 2022 as set out in the national reform programme and remaining constant thereafter; inflation rising progressively to 2% by 2030 and an average effective interest rate of 2.7% from 2018. The “higher inflation and higher GDP growth” scenario assumes higher inflation by 0.5 percentage point and higher real GDP growth by 1 percentage point per year, both from 2019. The “higher interest rate” scenario assumes higher interest rate by 1 percentage point from 2019.

Source: Calculations based on OECD (2016), “OECD Economic Outlook No. 100, Volume 2016 Issue 2”, OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), November.

The 2012 Law on Budgetary Stability and Financial Sustainability strengthened the fiscal framework by putting in place explicit deficits, debt and expenditure targets for each level of government and setting up procedures for annual budgetary objectives, monitoring and sanctions in case of non-compliance. These mechanisms have been bolstered by the creation of a fiscal council in 2013. The implementation of the stability law has faced some challenges with deficit and spending targets often missed. In 2016 additional corrective measures were applied, such as additional conditionality when accessing liquidity and budget appropriation cuts of EUR 1.5 billion to meet the deficit targets.

The additional conditionality on accessing liquidity is welcome since regional liquidity mechanisms in the form of conditional loans at low interest rates from the central government have helped regions, but could lead also to risky fiscal behaviour (Banco de España, 2016a; IMF, 2015; Cuenca and Ruiz Almedral, 2014). Transparency has improved with the monthly publication since 2016 of the actions to comply with the expenditure rule, which has been missed by all levels of government in the past, and regions adjustment plans to meet their targets.

Dealing with spending pressures due to aging

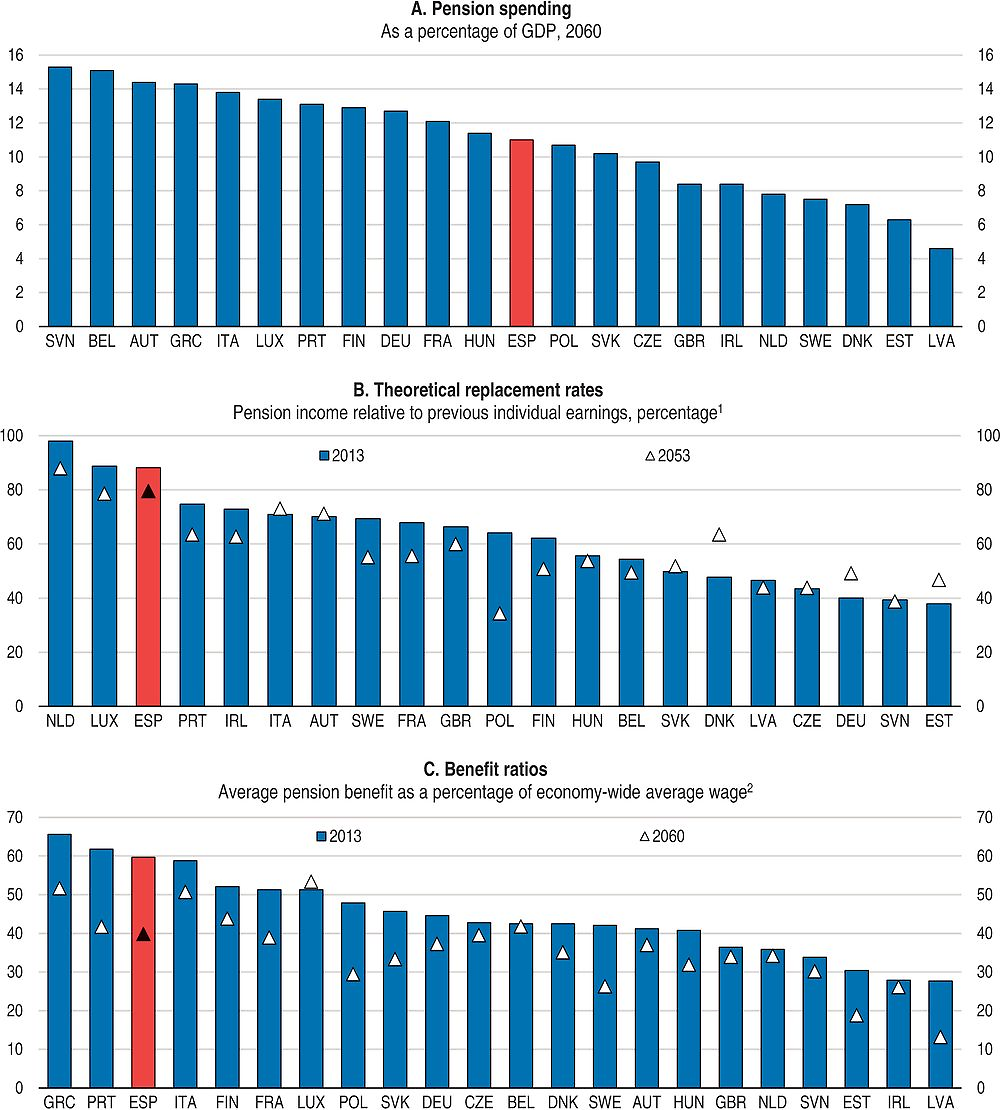

Fiscal sustainability could also be negatively impacted by contingent liability risks, such as high pension spending. Spain’s social security regime faces the impact of population ageing and the legacy of the crisis, which has cut revenues. The problem has been crystallised in the public debate by the prediction that the pension Reserve Fund will be exhausted by end-2017. Important pension reforms in 2011 and 2013 (Box 1) will help dampen the increase in aging-related spending in the longer-term. The government estimates that these reforms will result in 2.5% of GDP lower spending by 2060 (Government of Spain, 2016). As a result pension spending is expected to be 11% of GDP in 2060 (Figure 12, Panel A), slightly decreasing from 11.8% of GDP in 2013 (European Commission, 2015). These projections suggest that the reforms substantially reduce fiscal sustainability risks in the long-term (European Commission, 2015).

1. Level of pension income in the first year after retirement as a percentage of individual earnings at the moment of retirement. Data refer to those men who contributed to the pension system for 40 years up to the standard pensionable age.

2. The average pension is calculated as the ratio of public pension spending relative to the number of pensioners, whereas the average wage is proxied by the change in the GDP per hours worked. The ratio of these two indicators is intended to provide an estimate of the overall generosity of pension systems.

Source: European Commission (2015), “The 2015 Ageing Report”, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, March; and European Commission (2015), “The 2015 Pension Adequacy Report”, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, October.

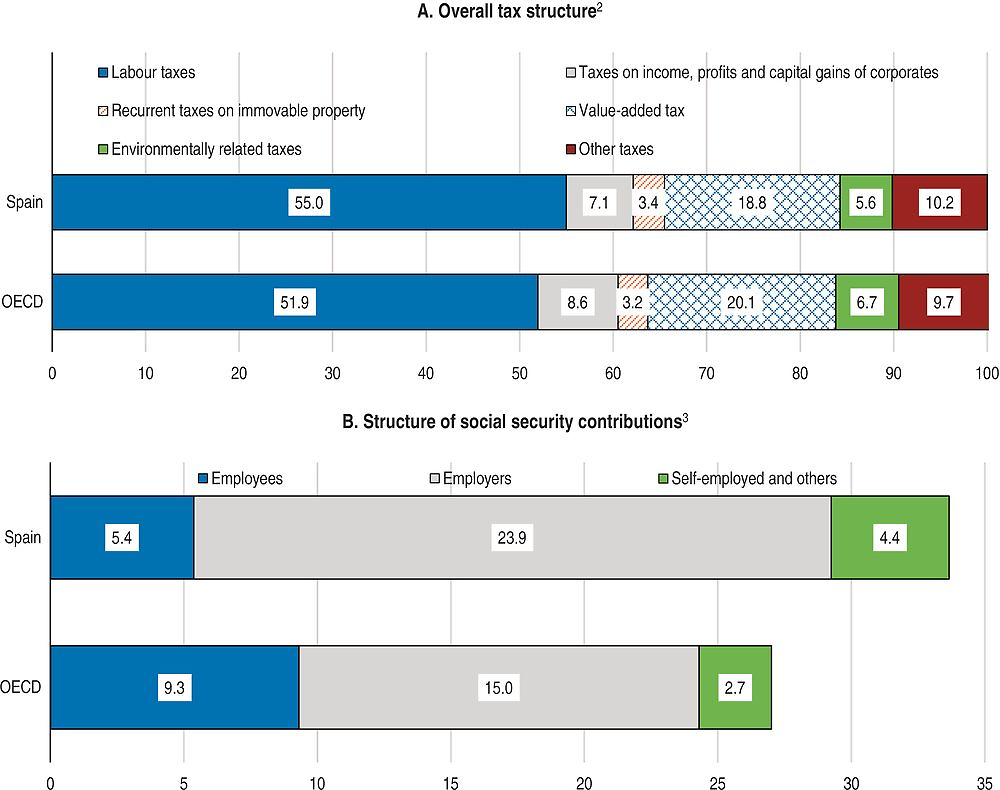

Such projections are subject to considerable uncertainty, though, which may require further reforms. Social security contributions are already high (28% of labour costs compared with an OECD average of 22.4%) and increasing them further to pay for pensions could undermine employment and international competitiveness. Instead, pension financing should be considered in the context of a broader tax reform (see next section), with a view to raising any needed funds in the most efficient way. The theoretical replacement ratio for those with a full career remains very high even after the reform (Figure 12, Panel B). This contrasts with one of the largest reductions in the benefit ratio – the average benefit among all pensioners – among European countries as of 2060 (Figure 12, Panel C). This reflects the effect of shorter contribution periods that is comparatively higher in Spain relative to other EU countries (European Commission, 2015) because of long unemployment spells. The reduction in the benefit ratio calls for reducing unemployment and temporary jobs further (as discussed below) to ensure the adequacy of pensions for as many people as possible. Finally, survivors’ pension benefits could be limited to cases of need, as recommended in previous OECD Surveys (OECD, 2010).

Tax reform to promote growth, employment and environmental quality

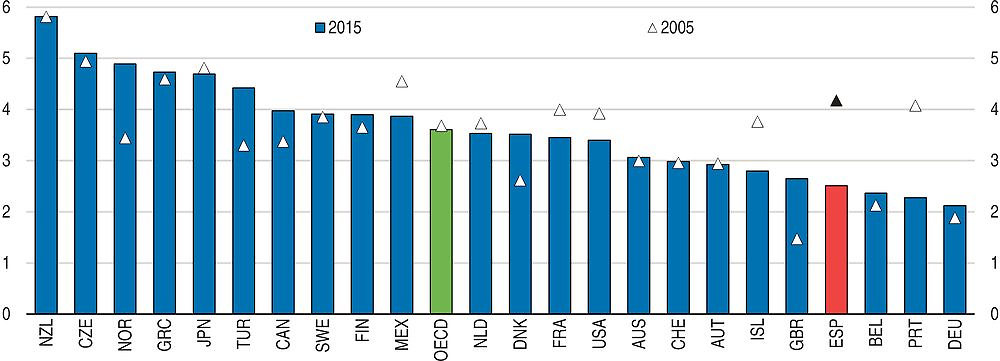

Spain implemented a reform in 2015 and 2016 to make the tax system more redistributive and conducive to growth, including by reducing the tax wedge on labour (OECD, 2014a, Box 1). The share of labour taxation has declined. However, the structure of taxation remains tilted towards labour income which penalises growth and employment (Johansson et al., 2008). In contrast, less distortive recurrent taxes on residential immovable property, value-added tax (VAT) and environmentally-related taxes are somewhat under-exploited (Figure 13). Also, narrow tax bases, in particular for the VAT and the corporate income tax, generate distortions and complexity at the same time as they reduce revenues.

← 1. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average and due to data availability it does not include Australia, Greece, Japan, Latvia, Mexico and Poland.

2. Labour taxes are calculated as the sum of taxes on income, profits and capital gains of individuals, social security contributions and taxes on payroll and workforce. Other taxes include all other taxes on property except for recurrent taxes on immovable property, such as recurrent taxes on net wealth, estate, inheritance and gift taxes, taxes on financial and capital transactions and other recurrent and non-recurrent taxes on property as well as all other taxes on goods and services except for value-added tax.

3. Self-employed and others include social security contributions of self-employed and other tax revenues that are unallocable between employees, employers and self-employed.

Source: OECD (2016), “Revenue Statistics: Comparative tables”, OECD Tax Statistics (database), December; and OECD (2016), “Green Growth Indicators”, OECD Environment Statistics (database), December.

The 2014 personal income tax reform reduced the tax wedge by exempting income up to EUR 12 000 and lowering personal income tax rates, likely contributing to boost labour supply, especially among those with low skills. However, the main focus should remain on creating permanent and quality jobs. A temporary measure to boost permanent jobs between February 2015 and August 2016 temporarily reduced social security contributions (SSCs) for employers by exempting the first EUR 500 of workers’ salaries employed on all new permanent contracts for two years. To further support job creation, the government should build on this cut in employer SSCs, making it permanent and also restricting it to low-wage workers. This will have more long lasting positive effects on employment among low-skilled workers, where the need to stimulate labour demand is largest. Such a reduction in employer SSCs should be considered in the context of a broader tax reform to improve the tax structure which is currently titled towards labour income which penalises growth and employment.

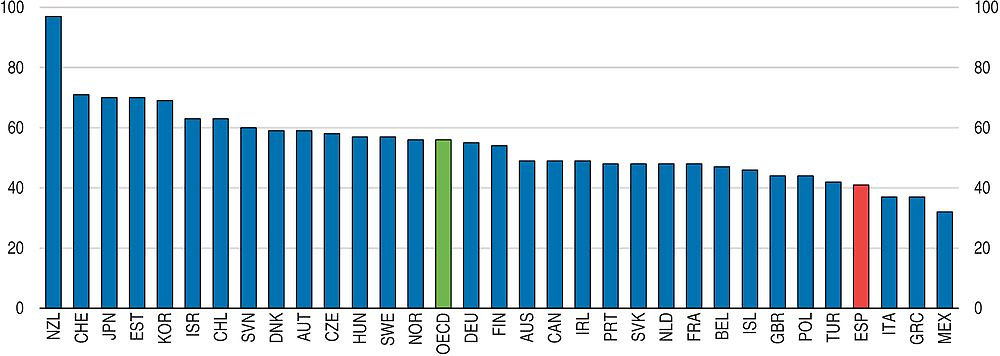

Exemptions and reduced rates significantly reduce VAT revenue and are the main factor behind Spain’s poor efficiency in VAT collection (Figure 14). Reduced rates on fresh food and other basic necessities are generally redistributive, albeit poorly targeted, but other reduced rates tend to benefit richer households the most (OECD, 2014c). The authorities should reassess the merits of reduced VAT rates and eliminate those which mainly benefit the rich.

← 1. The VAT revenue ratio (VRR) is defined as the ratio between the actual value-added tax (VAT) revenue collected and the revenue that would theoretically be raised if VAT was applied at the standard rate to all final consumption. This ratio gives an indication of the efficiency of the VAT regime in a country compared to a standard norm. It is estimated by the following formula: VRR = VAT revenue/[(consumption – VAT revenue) × standard VAT rate]. VAT rates used are standard rates applicable as at 1 January of each year. The fact that public consumption is VAT-exempt under EU rules places an upper bound on the attainable VRR, especially in countries with a large public sector, such as Spain. For Canada, the VRR calculation includes federal VAT only. For Japan, given the substantial VAT rate hike on 1 April 2014, an average VAT rate was used to calculate the VRR for 2014. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average of the data shown.

Source: OECD (2016), Consumption Tax Trends 2016: VAT/GST and excise rates, trends and policy issues.

There is also scope to improve VAT revenues via better administration and enforcement. Early detection of organised VAT fraud was reinforced in 2015. A new electronic VAT filing system for invoices is foreseen for 2017. The government should continue these efforts. Addressing non-compliance will help to broaden the VAT base and improve public acceptance and trust in the tax system. Excise duties on tobacco and alcohol were recently raised but are still below EU average and could be increased further. In this respect, new measures taken by the government in December 2016 to increase taxes on alcohol, tobacco, as well as creating a new tax on sugary drinks are welcome.

The personal income tax base is eroded by generous deductions and exemptions. Besides lowering revenue, these items make the tax system more complex to manage. As discussed in Haugh and Martínez Toledano (2017), a number of tax exemptions are particularly regressive, including the exemptions on the interest from investing in the primary residence, on renting the primary residence and the deductions for contributions to personal pension plans. Deductions for contributions to personal pension plans were tightened in 2015. While the tax deduction for investing in the primary residence was recently eliminated, the transitory regime is still benefitting all those who purchased their house before 2013. This credit is expected to cost EUR 1.2 billion in 2016 (Ministerio de Hacienda y Administraciones Públicas, 2016) and tends to benefit higher income households. Removing these exemptions provides an opportunity to improve the equity and efficiency of the tax system.

The recent reduction in the standard corporate income tax rate from 30% in 2014 to 25% in 2016 – aligning the tax rate for all firms – is welcome, as evidence suggests that high corporate taxes are relatively harmful for growth (Johansson et al., 2008). However, more could be done to broaden the corporate income tax base. For instance, making depreciation allowances more neutral across asset types and businesses by aligning tax depreciation with the economic depreciation of assets could also contribute to broaden the base and help reduce distortions to capital allocation (OECD, 2014d).

The government has introduced in December 2016 a number of measures to broaden the corporate income tax base affecting large companies that is expected to raise EUR 4.6 billion. Most notably, the measures include limiting how much companies can deduct past losses (25% for companies with net revenues above EUR 60 million and 50% for companies with net revenues between EUR 20 and EUR 60 million). It also further limits the deductibility of impairment losses – i.e. losses that arise because tangible or intangible goods loose value. The government should carefully monitor the impact of these measures. Given the deep economic downturn many businesses have made losses, which they will now partly loose. Such measures might reduce firms’ incentives to take risks in the future and could also significantly reduce the attractiveness of Spain as a location for investment.

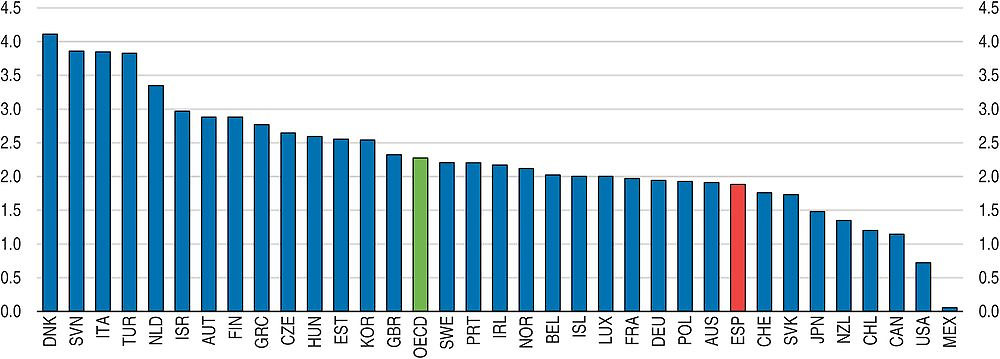

Spain has considerable scope to make the tax system more environmentally friendly, as environmental tax revenue as a share of GDP is low compared to most OECD countries (Figure 15). There is scope to raise tax rates on fuel for road transport, which are below OECD average. Moreover, diesel is under-taxed relative to gasoline encouraging consumers to buy diesel cars despite diesel cars produce more CO2 emissions per litre than gasoline, and diesel cars emit more health damaging air pollutants per kilometre driven. The government should increase taxation per litre of diesel to at least the level of taxes on gasoline, and should increase diesel prices further if differences in local pollution costs are to be reflected in fuel prices. Simulations suggest that additional EUR 4 billion of revenues could be raised by taxing diesel at the same rate in energy terms as gasoline (OECD, 2014d). OECD research shows that carbon prices are not likely to change the competitiveness of affected firms; higher energy prices also do not raise particularly strong distributional concerns (Flues and Thomas, 2015; OECD, 2016c). There is also scope to reduce exemptions to broaden the environmental tax base, as some users in agriculture, mining, aviation, navigation and railway transport are exempted from fuel tax or the excise duty on electricity (OECD, 2015c).

← 1. 2013 for Poland. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average of the data shown.

Source: OECD (2016), “Green Growth Indicators”, OECD Environment Statistics (database), December.

Making growth more inclusive by reducing unemployment and improving job quality

Improving the functioning of the labour market and strengthening the skills of Spanish workers will be paramount to make growth more inclusive and raise well-being. The labour market faces several problems, the most important of them being very high unemployment, a low level of skills, and the high share of long-term unemployed (47.8% of all unemployed in the fourth quarter of 2016).

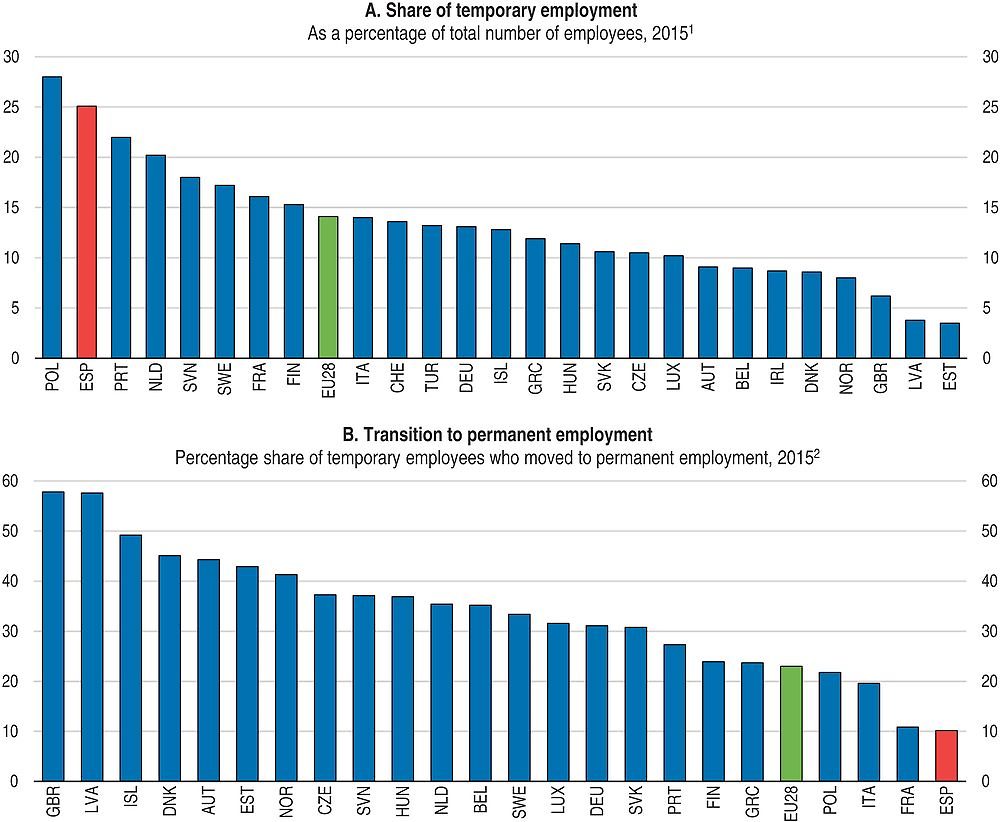

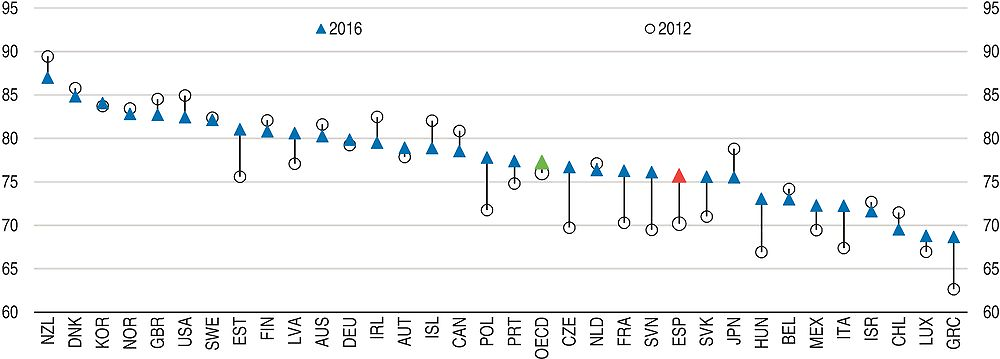

Moreover, job quality, which deteriorated in the wake of the crisis, needs to improve to make growth inclusive. Job quality, in the form of earnings, labour market security and the quality of the working environment, is important for well-being and productivity (OECD, 2014e; Cazes et al., 2015). Spanish workers faced the highest probability of becoming unemployed in the OECD in 2013, mainly as a result of massive job separation from temporary contracts. Once unemployed, the expected length of unemployment spells was also very high by OECD standards. This is likely to have improved somewhat since then given the labour market recovery, as outflows to unemployment have fallen. However, one quarter of all employees is on temporary jobs, the highest share in the OECD after Poland (Figure 16, Panel A). In addition, Spain also shows the lowest rate of transition from temporary workers into permanent employment (Figure 16, Panel B). Average earnings are also comparatively low reflecting weak worker skills and poor firm productivity (Chapter 1). Finally, job demands on workers such as time pressure or physical health risks are excessive compared to the resources they have, including weak access to training.

1. Data refer to those aged 15 years and over.

2. 2014 for Germany, Greece, the United Kingdom and the European Union (EU28) aggregate.

Source: Eurostat (2016), “Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey)”, Eurostat Database, December.

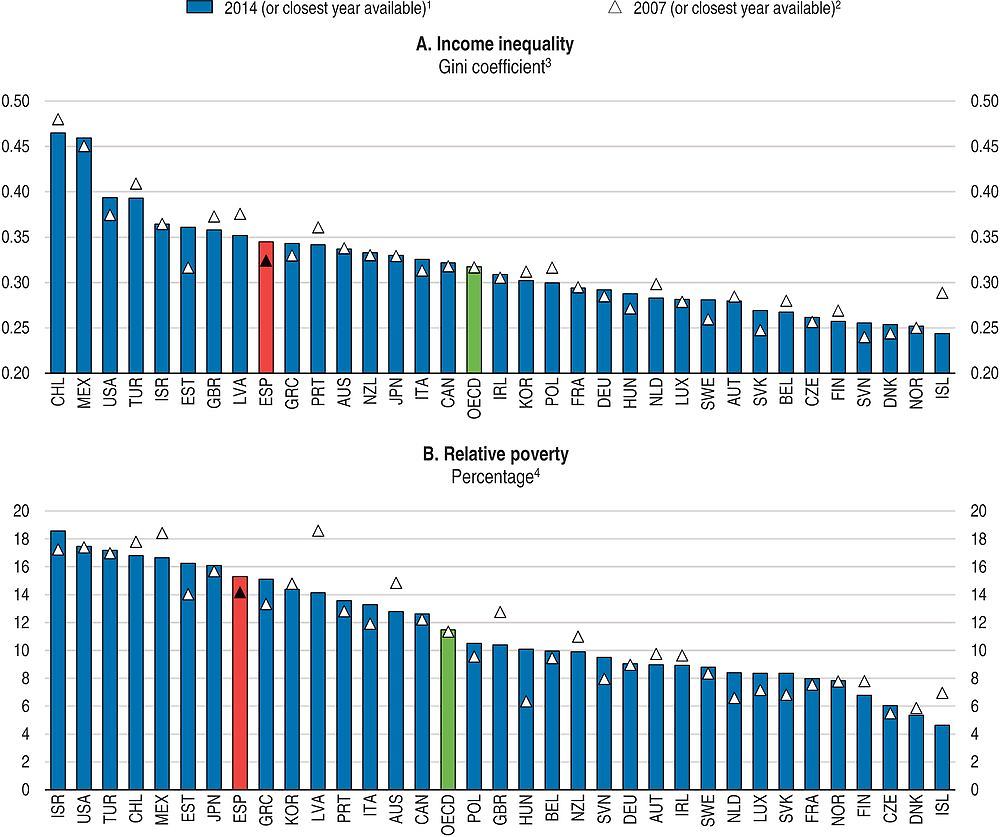

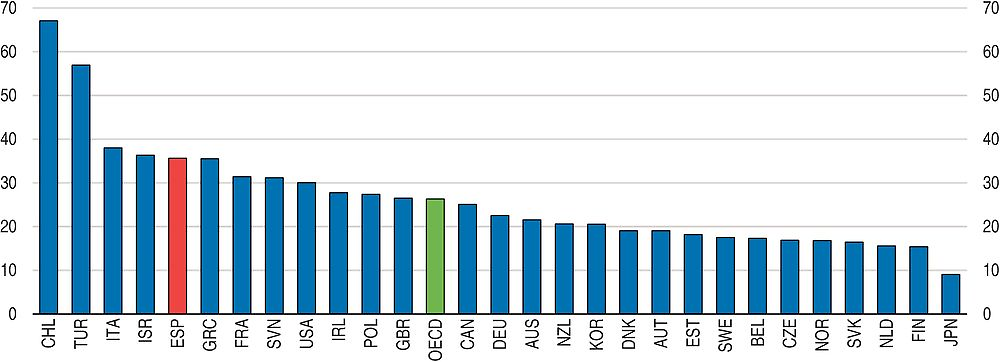

The steep rise in joblessness in the wake of the crisis and, to a lesser extent, higher disparity in annual earnings, raised income inequality (Figure 17, Panel A). Jobless people and temporary workers are at the bottom of the income distribution. The poverty rate – measured by the share of households living with less than 50% of the median household disposable income – remains high (Figure 17, Panel B), despite declining somewhat in 2014, and it is likely to have continued declining since given the improvement in the labour market. Poverty is particularly high among jobless households, especially those with children, as reflected by a high child poverty rate of 23.4% compared to an OECD average of 13.3% in 2013.

1. Data refer to 2014 for Australia, Finland, Hungary, Israel, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, Spain and the United States; to 2012 for Japan and New Zealand; and to 2013 for all other countries.

2. Data refer to 2008 for Australia, France, Germany, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and the United States; to 2006 for Japan; and to 2009 for Chile; and to 2007 for all other countries.

3. The Gini coefficient is calculated for household disposable income after taxes and transfers, adjusted for differences in household size and it has a range from zero (when everybody has identical incomes) to one (when all income goes to only one person). Increasing values of the Gini coefficient thus indicate higher inequality in the distribution of income. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average of the data shown.

4. The relative poverty rate is defined as the share of people living with less than 50% of the median disposable income (adjusted for family size and after taxes and transfers) of the entire population. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average of the data shown.

Source: Provisional data from the OECD Income Distribution Database.

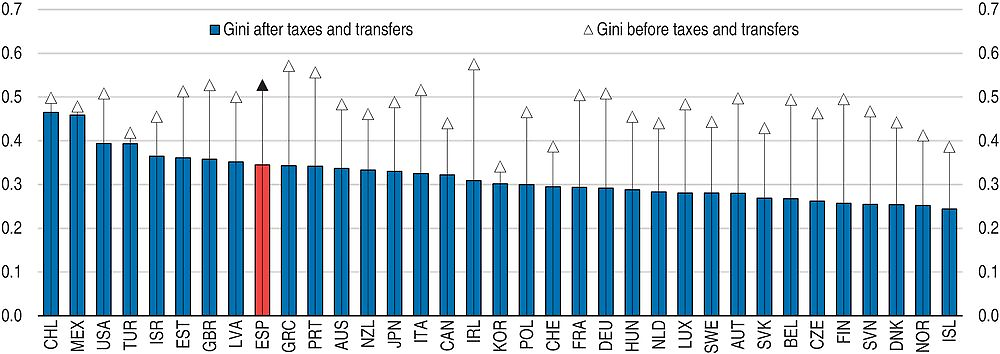

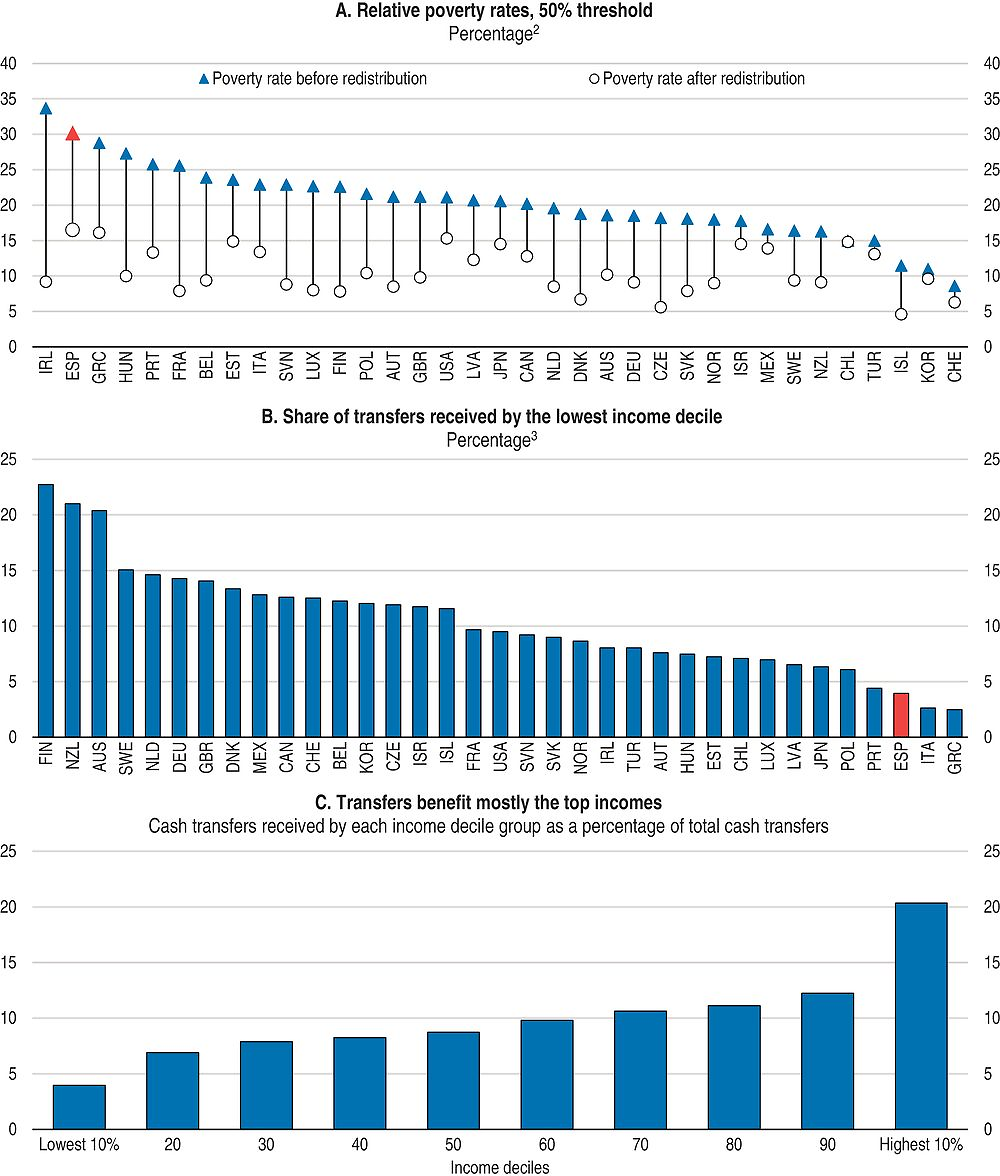

The tax and transfer system does help to reduce income inequality and poverty (Figure 18) and there is some evidence that suggests that the 2014 tax reform might have contributed to lowering inequality (Instituto de Estudios Fiscales, 2015), but more can be done. Transfers help to reduce poverty, but are low and benefit the better-off (Figure 19). Public support for families is weak in general. Social spending per child is below the OECD average and is particularly low for early childhood, resulting from low spending on family cash benefits and on public childcare services. Family cash benefits accounted for only 0.5% of GDP in 2013, much below the OECD average of 1.2%, and can be enhanced given the high child poverty rate. Reinforcing public childcare services will not only help to alleviate child poverty by reducing childcare costs for poor households, but will also help reconcile work and family life, supporting female labour force participation and encouraging early childhood education – whose benefits in terms of subsequent school attainment are well documented (OECD, 2011; Heckman et al., 2010).

← 1. Data refer to 2014 for Australia, Finland, Hungary, Israel, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, Spain and the United States; to 2012 for Japan and New Zealand; and to 2013 for all other countries. The Gini coefficient has a range from zero (when everybody has identical incomes) to one (when all income goes to only one person). Increasing values of the Gini coefficient thus indicate higher inequality in the distribution of income.

Source: Provisional data from the OECD Income Distribution Database.

← 1. 2014 for Australia, Hungary and Mexico. 2012 for Japan and New Zealand.

2. The relative poverty rate is defined as the share of people living with less than 50% of the median disposable income (adjusted for family size) of the entire population.

3. Current transfers received from public social security.

Source: Calculations based on the OECD Income Distribution Database.

Strengthening social support and getting more people into good jobs

Many unemployed people have exhausted their benefits and thus are at risk of poverty and social exclusion. Social protection for those of working age in Spain consists not only of unemployment insurances and other programmes managed by the central government, but also of minimum income supports schemes run by regional authorities. The regional minimum income schemes are generally weak and with limited coverage and effectiveness. Only 1.5% of households received minimum income support in 2014 from the regional schemes. The Renta Mínima de Inserción (RMI) is the most common income support scheme for those who are not eligible for unemployment benefits. However, potential beneficiaries of the Renta Mínima de Inserción usually need to go through long and cumbersome procedures to qualify. Simplifying these procedures should help improve access and coverage for those eligible.

Basic support programmes to address poverty should be rethought. The schemes should be streamlined, and coverage and the amount of support should be raised, especially for families with children. Importantly, the social benefits for jobless people should be strictly conditional on active job search which helps the beneficiaries to stay connected to the labour market through public employment services. Finding a job is the best way to get out of poverty durably. The income support system should also be better co-ordinated with public employment services so that stronger links between protection and activation are built into the system. The benefit should also be withdrawn more gradually as earned income rises, instead of one-for-one reductions in the benefit as it is the case currently, in order not to blunt financial incentives to work.

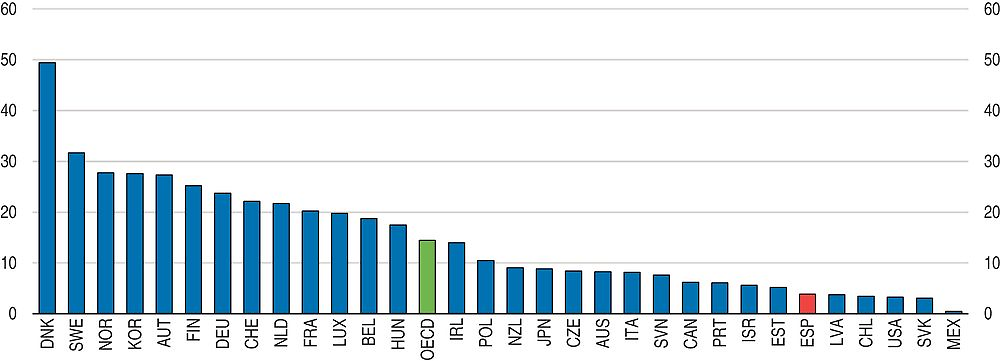

Policies to get people back into jobs are also critical. Spending on active labour market measures – such as training and job placement – has increased (Table 4). Also, funding from the central government is increasingly conditional on the performance in moving people into work at the regional level, where the programmes are administered. However, spending remains low (Figure 20) and public employment services still struggle to be effective in finding jobs for the unemployed. Recent initiatives have been developed to better profile and serve job seekers and to employ more specialised counsellors. However, the sheer number of unemployed and the multiple barriers they face require more targeting, more efficient use of resources and lower caseloads for staff. In providing support to the long-term unemployed, the regional public employment services should upgrade their services by improving their profiling tools and the co-ordination with social services in providing support. Greater digitalisation could help to improve performance in particular by streamlining processes whilst keeping costs down.

← 1. The OECD aggregate is calculated as an unweighted average of the data shown.

Source: OECD (2016), “Labour market programmes: expenditure and participants”, OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database), December.

The long-term unemployed need better targeted and more effective programmes. The existing programmes, Renta Activa de Inserción (RAI), Programa de Recualificación Profesional (PREPARA) and Programa de Activación para el Empleo, (PAE) launched at different stages and with different targets could be better co-ordinated or streamlined to become more effective. The PAE – a major package of income support and training targeted at the long-term unemployed with dependants – has helped 15% of its participants find work, which is relatively successful compared with similar programmes in other countries (Card et al., 2015). The experience with this programme on intensified assistance and strict requirements for active job search could be extended more generally. Besides, the financial support of the existing programmes – currently around EUR 400 per month – could be increased, as far as the budget allows, making the programme more effective.

Job search requirements attached to unemployment benefits are an important tool to get people back to work (OECD, 2015b). These exist but the criteria on active job search are not necessarily clear, including those on a suitable job offer which jobseekers have to accept (OECD, 2014a). Moreover, the sanction on non-fulfilment rarely applies. Greater co-ordination between the central government responsible for unemployment benefits and regional authorities in charge of local public employment services is needed, since conditionality of active job search needs to be applied. Progress towards a more integrated support for jobseekers, particularly for the long term unemployed, including a single point of contact for all services and assistance, could help.

Strengthening skills

Strengthening the relatively poor skills of the Spanish workforce will be crucial to get them into good jobs and to boost Spain’s growth potential (Figure 21 and Table 5). Monetary support in the programmes for the long-term unemployed should be coupled more closely to re-training in collaboration with vocational education and training (VET) schools or “Adult Education” programmes. Most of the long-term unemployed lack basic skills and recognisable diplomas and substantive retraining could help them gain relevant skills to find new jobs. Spain has a relatively extensive offer of “Adult Education” programmes and these programmes could be reoriented towards work-based training for the long-term unemployed.

← 1. 2015 for Chile, Greece, Israel, New Zealand, Slovenia and Turkey. Low-performing adults are defined as those who score at or below Level 1 in either literacy or numeracy. The OECD aggregate refers to the unweighted average of the 28 OECD countries that participated in the OECD Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). Data for Belgium refers to Flanders. Data for the United Kingdom refer to England.

Source: OECD (2016), Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills.

The Youth Guarantee scheme is meant to promote vocational guidance, labour information and assistance in job seeking, and hiring, notably. However, although Spain has received the highest share in the total funding by the European Union to implement the guarantee, the programme had a slow start and is not reaching yet as many youth “not in education, employment, or training” (NEETs) as it should. Recent measures adopted in December 2016 that imply that youth registered with the public employment services will automatically be registered with the youth guarantee system may help boosting registration and increase the number of NEETs receiving help.

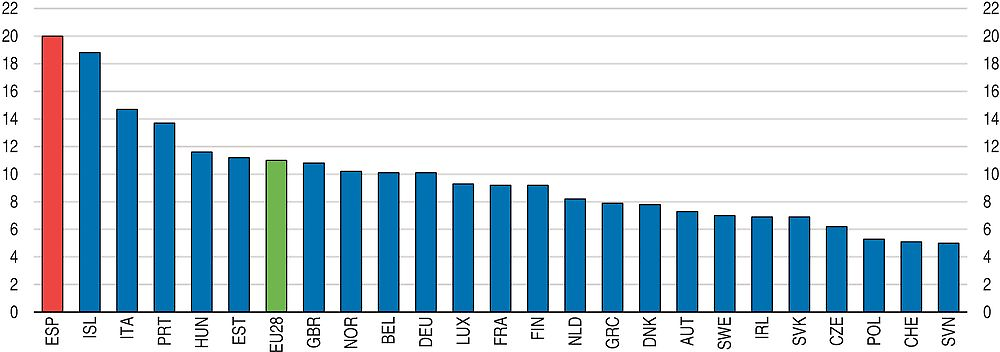

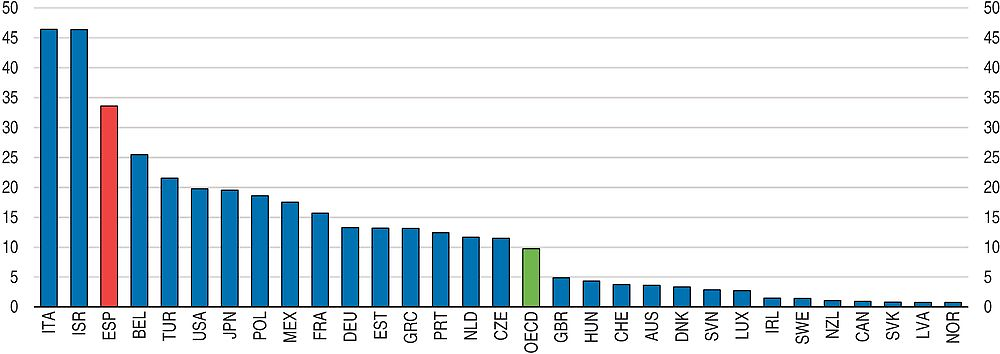

There is also a need to improve compulsory education. The incidence of early school leave has significantly fallen in recent years (from 26.3% in 2011 to 19.9% in 2015). Nevertheless, Spain still has the highest incidence of early school leave in the EU (Figure 22) and educational outcomes are poor (OECD, 2015d). This is explained by a number of factors: good employment opportunities for low qualified youth in some regions, reduced number of pathways to upper-level secondary education or the perceived lower labour market value of some secondary vocational education and training (VET) degrees. The Organic Law for the Improvement of Educational Quality (LOMCE) has been gradually rolled out since 2014 with one of its aims being to tackle early drop-out rates (OECD, 2014a, Box 1). For example, the law created a new Basic VET that will provide a new path to upper secondary education and provides some tools for improving upper secondary VET degrees by regions and schools. While it is too early to evaluate the impact of the law, given its broad scope and uneven implementation across regions, its objectives go in the right direction, with an increased focus on competencies and skills.

Source: Eurostat (2016), “Early leavers from education and training”, Eurostat Database, December.

However, more needs to be done to improve teaching quality and educational outcomes. OECD evidence shows that Spanish teachers are less likely to benefit from on the job support programmes than teachers in other OECD countries, and that the support they receive is not very effective (OECD, 2015d). Teachers also lack incentives and support to participate in development activities. To effectively implement the new pedagogical approaches in the law and help low achievers, teachers need better training and guidance if the reform is to improve educational outcomes and reduce early drop-outs. Measures to enhance the quality of teaching include improving university training, a better selection process, and effective on-the-job training. Moreover, regions should evaluate how their spending is currently being allocated in order to more effectively reduce early drop-out rates.

Vocational education and training (VET) can facilitate the transition from school to work. The Organic Law for the Improvement of Educational Quality introduced the new Basic VET, a fall-back programme for the least performing students which leads them to obtaining a certificate recognised by the European Union, which apparently has helped to reduce the early school leave rate. The Organic Law, in its primal objective for the VET reform, made the upper-secondary VET more attractive to students and employers: by redesigning upper-secondary VET courses to adapt them to labour market needs, increasing training at the work-place, strengthening the teaching of foundation skills and making the transition between upper secondary and tertiary VET easier. More funding has also been allocated. Despite this progress, few students are enrolled in secondary-level VET, although graduation rates have increased, and these programmes remain not sufficiently work-oriented and generally do not lead to tertiary-level VET.

More efforts are needed to consolidate the dual VET system, which combines work and school learning. The use of apprenticeship and training contracts has grown substantially since 2012, but only 2% of students in upper-secondary school are enrolled. A major challenge to expanding it further is securing commitment from firms to provide training: most firms in Spain are micro-enterprises that do not have sufficient financial and human resources to collaborate with VET programmes. Against such constraints, the authorities are trying to develop wider co-operation among stakeholders. The Chambers of Commerce, in co-operation with the business and labour unions take an important role to support collaboration between firms and educational institutions. Such co-operation could be further facilitated by building on the experience of some regions where clusters of firms with a shared need for workers with certain VET qualifications work together (as Grupo de Iniciativas Regionales de Automoción in Cantabria, Northern Spain). A more active role of employers in designing the curricula by ensuring that the skills being developed meet companies’ skill needs would help strengthen co-operation.

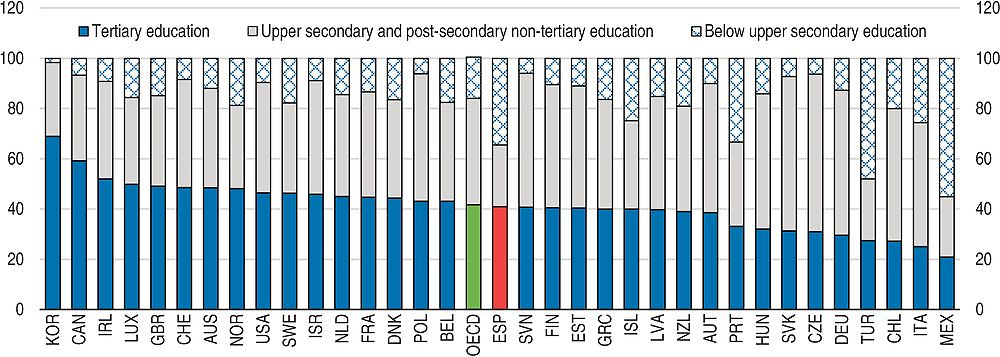

While upper secondary education attainment is well below the OECD average (Figure 23), tertiary educational attainment is now on a par with many other OECD countries. However, the skills of tertiary graduates are among the lowest in the OECD suggesting a low quality of university education (OECD, 2015d) compounded with a deterioration of skills once in the labour market. A complex set of factors explain the low skills Spanish students acquire at university (OECD, 2014a), including funding formulas based almost exclusively on the number of students, governance systems with insufficient external accountability, selection procedures that promote inbreeding and very low mobility of students and teachers.

← 1. 2013 for Chile. 2014 for France.

Source: OECD (2016), “Education at a glance: Educational attainment and labour-force status”, OECD Education Statistics (database), December.

Reducing labour market duality

More needs to be done to reduce labour market duality to improve job quality. Temporary workers particularly suffer from labour market insecurity, which reduces their earnings (sometimes putting them at risk of poverty), the possibility of training and future job prospects. The 2012 labour market reform reduced severance payments for permanent contracts, provided hiring subsidies for new permanent workers and reinstated statutory limitations on the use of temporary contracts. The reform also aimed to define more clearly the criteria under which dismissals would be considered fair, with the aim of reducing firms’ costs of firing and, therefore, facilitate hiring (OECD, 2014g; García-Pérez, 2016). However, uncertainty regarding labour court decisions remains high and many firms still continue to opt for accepting up front that the dismissal may be considered unfair although it is more costly. Despite the reform, the share of temporary jobs in overall employment remains steady at around 25% and the duration of contracts is often very short.

Out-of-court procedures, such as conciliation, mediation and arbitration to settle disputes about dismissals could help to further reduce uncertainty. The use of conciliation procedures has been on the rise over the past four years, which could be developed further to enhance dialogue and provide a quicker and more effective response to litigation. Finally, the costs of dismissing a permanent worker are still substantially higher than those for a temporary one. As recommended in the 2014 OECD Economic Survey, greater convergence of termination costs between permanent and temporary contracts could further help to reduce duality.

Improving medium-term sustainable growth

Fostering productivity

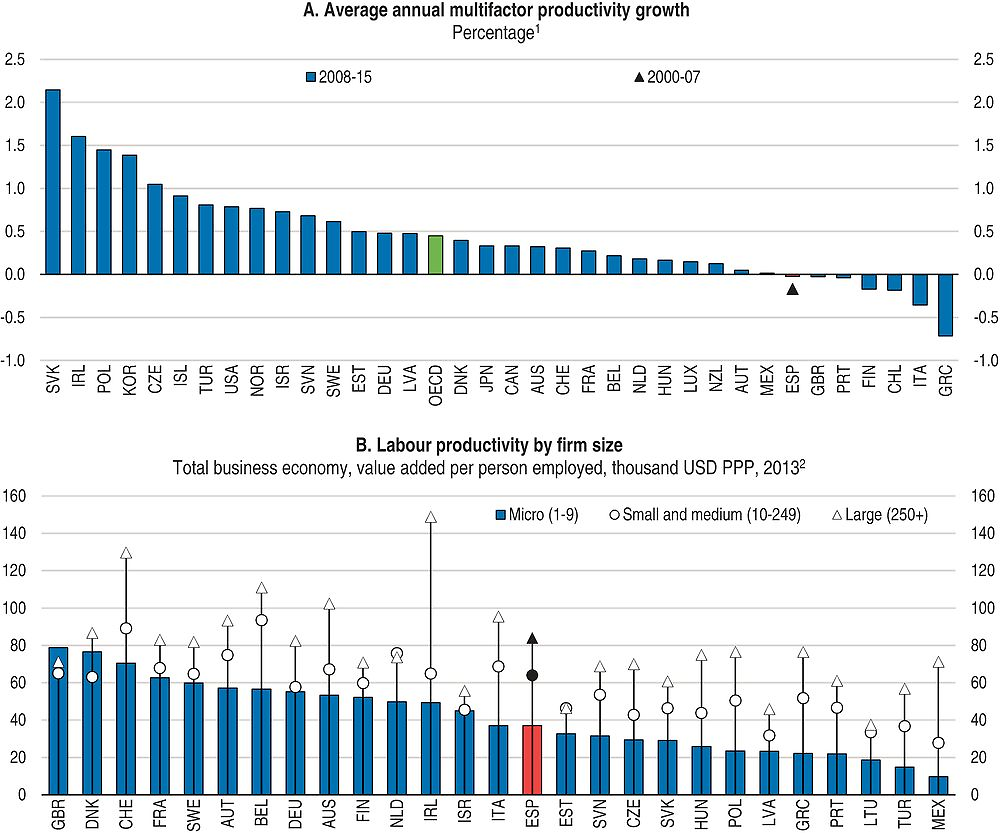

As previous OECD Surveys have noted, raising per capita GDP and wellbeing, particularly via productivity increases, is Spain’s most fundamental medium-term economic challenge (Table 6). Productivity growth has improved slightly post-crisis, in part due to the reduced share of the low productivity construction sector, but it remains low, averaging around 0% from 2008 to 2015 (Figure 24, Panel A). The business sector is characterised by a high share of low productivity micro-enterprises (1-9 employees) and small enterprises (Chapter 2 and Figure 24, Panel B).

1. The OECD aggregate is calculated as the unweighted average of the data shown.

2. 2014 for Mexico. 2012 for Israel. 2011 for Ireland. Firm size classes based on the number of persons employed. For Australia, the size class “1-9” refers to “1-19”, “10-249” refers to “20-199” and “250+” refers to “200+”. For Mexico, “1-9” refers to “1-10”, “10-249” refers to “11-250” and “250+” refers to “251+”. For Turkey “1-9” refers to “1-19” and “10-249” refers to “20-249”. Data for Switzerland and the United States refer to employees. Data for Mexico are based on establishments and not on enterprises. Data for the United Kingdom exclude an estimate of 2.6 million small unregistered businesses; these are businesses below the thresholds of the value-added tax regime and/or the “pay as you earn (PAYE)” (for employing firms) regime. Data for the United Kingdom exclude an estimate of 2.6 million small unregistered businesses; these are businesses below the thresholds of the value-added tax regime and/or the “pay as you earn (PAYE)” (for employing firms) regime. PPP: purchasing power parities.

Source: OECD (2016), “OECD Economic Outlook No. 100, Volume 2016 Issue 2”, OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), November; and OECD (2016), Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2016.

Productivity is held back by high barriers to starting and growing a business, low business innovation and high skill mismatch among others (OECD, 2014a; Haugh and Westmore, 2014; Mora-Sanguinetti and Fuentes, 2012). Increasing productivity involves tackling several challenges. Upskilling and activating the huge pool of unemployed and improving the quality of education that has impeded a greater contribution of human capital to growth, as discussed above, will be essential. Reducing regulatory barriers that restrain competition, encouraging innovation, and ensuring that capital goes to a wider set of innovative firms will also help to boost productivity. Indeed, there is a growing body of evidence that an important contributor to low productivity in Spain is misallocation of capital to low productivity firms within all sectors and under-investment in knowledge-based capital (Figure 25, Chapter 2), while misallocation of capital across sectors plays a more minor role (Mora-Sanguinetti and Fuentes, 2012; García-Santana et al., 2016).

1. Data for non-residential private investment refer to total investment (i.e. total gross fixed capital formation) minus government and housing investment. Since data for housing investment for Spain and Portugal may also include government housing, the series for non-residential private investment may be underestimated.

2. Data refer to business sector excluding real estate [i.e. all activities except for real estate activities (L), public administration and defence, compulsory social security (O), education (P) and human health and social work activities (Q)]. Investment refers to gross fixed capital formation. Investment in intangibles refers to all knowledge-based capital (KBC) assets. KBC assets that are consistent with the definition in the System of National Accounts (SNA) 2008 include: software, R&D, entertainment, literary and artistic originals, and mineral exploration. Other KBC assets include: design, new product developments in the financial industry, brands, firm-specific training and organisational capital. Investment in tangibles refers to gross fixed capital formation in construction and machinery and equipment.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), February; OECD (2017), OECD National Accounts Statistics (database), February; OECD (2015), OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2015: Innovation for growth and society; Corrado, C., J. Haskel, C. Jona-Lasinio and M. Iommi, (2012), “Intangible Capital and Growth in Advanced Economies: Measurement Methods and Comparative Results”, Working Paper, June (available at www.intan-invest.net).

Reducing regulatory barriers that restrain competition

An efficient regulatory framework that supports competition and innovation is crucial to boost productivity. The country has made progress in improving product market regulations and converging towards best practices, which is a significant incentive for firms to innovate and become more productive. The government continues to make progress in implementing the 2013 Market Unity Law to improve business regulations across the 17 regions and thereby create a truly single market in Spain. An important step in this direction has been setting up a process where the government promptly considers complaints from anyone about new laws and regulations inconsistent with the Market Unity Law. However, doing business is still perceived to be more difficult in Spain than in other OECD economies (Figure 26). The central government and the regions reached an agreement in January 2017 to foster greater co-operation on ensuring market unity and implementing better-regulation principles. This is a welcome move and the central government and the regions should continue to maintain momentum in implementing the Market Unity Law to ensure that the obstacles businesses face keep falling and that regulatory reform has visible effects on productivity.

← 1. The distance to best practice frontier score helps assess the absolute level of regulatory performance over time. It measures the distance of each economy to the “frontier”, which represents the best performance observed on each of the indicators across all economies in the Doing Business sample since 2005.

Source: World Bank (2016), Doing Business 2017: Equal Opportunity for All.

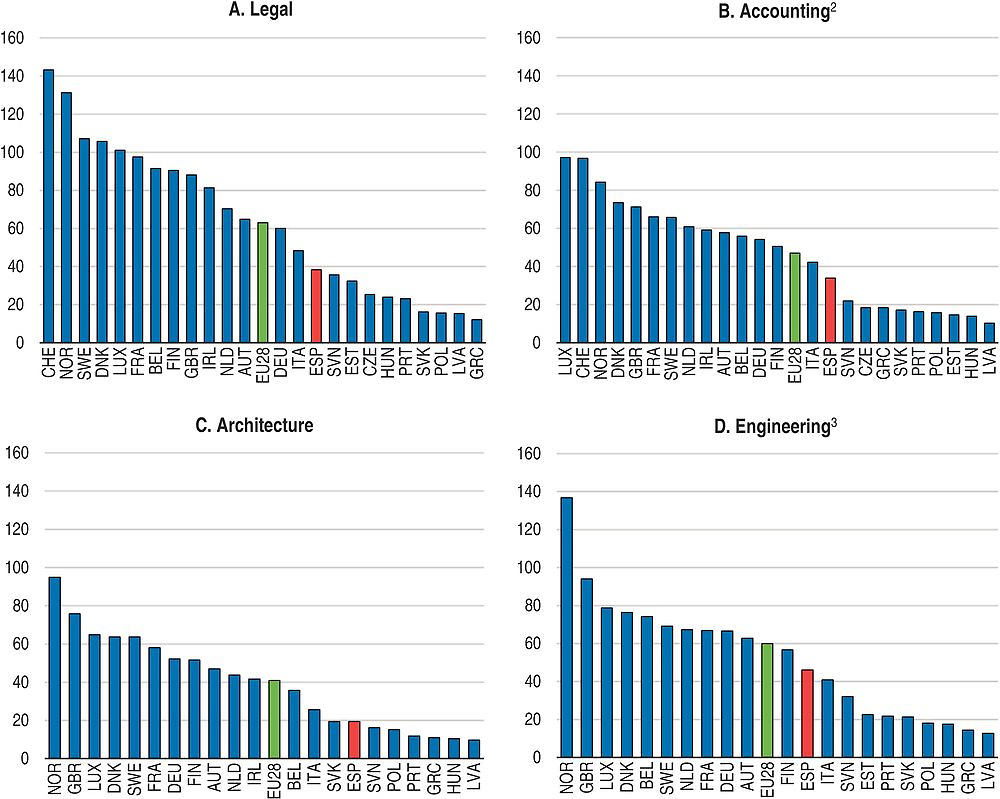

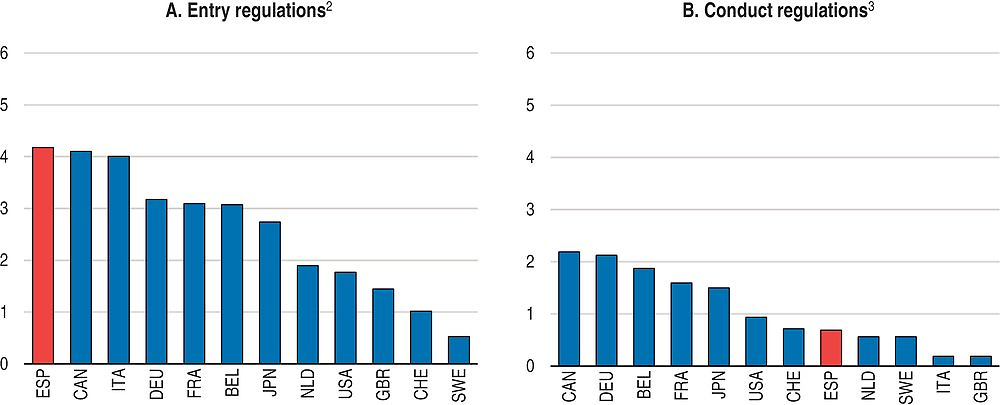

Competition is still rather weak in sectors that supply inputs to the business sector, most notably in the professional service sector. Professional services – which account for 75% of business services – are markedly less productive in Spain than in other European economies (González Pandiella, 2014 and Figure 27). Professional services are subject to entry requirements in Spain that are higher than those in most other OECD countries (Figure 28). Opening up these services to competition would increase productivity, reduce prices, improve the quality of services and provide more job opportunities. The authorities should adopt the reform of the liberalisation of professional services that has been planned for some time, but is still pending, that would facilitate access to and the exercise of professional services, as well as increase the accountability of professional bodies.

← 1. 2012 for Ireland.

2. Accounting, bookkeeping and auditing; tax consultancy.

3. Including related technical consultancy.

Source: Eurostat (2017), “Structural business Statistics – Services”, Eurostat Database, February.

← 1. Professional services cover four sectors: accounting services, legal services, engineering services and architectural services. For further details see Koske, I., I. Wanner, R. Bitetti and O. Barbiero (2015), “The 2013 update of the OECD product market regulation indicators: policy insights for OECD and non-OECD countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1200.

2. Entry regulations cover exclusive or shared exclusive rights, education requirements, compulsory chamber membership and quotas.

3. Conduct regulations cover regulations on prices and fees, regulations on advertising, regulations on the form of business and inter-professional co-operation.

Source: OECD (2013), OECD Product Market Regulation Database.

The Spanish wage bargaining system has been essentially characterised by collective bargaining at the sector level for long time. The extension of collective agreements at the sector level is automatic across the country, regardless of the representativeness of parties involved in collective bargaining. Such collective agreements then bind not only wages but also other employment conditions such as working time and shifts, unless firm-level agreements exist. The 2012 reform gave priority to firm-level collective agreements and relaxed the conditions for firms to opt-out (OECD, 2014g). The reform contributed to wage moderation (OECD, 2014g; Doménech et al., 2016; García-Pérez, 2016), but firm-level agreements have been concluded essentially only in large firms, and less than five per cent of all firms, many large ones, have opted-out. The authorities should reconsider the conditions under which the statutory collective agreements are extended, in particular, by gradually requiring higher and stricter representativeness of business associations and by checking that such representativeness applies. This would help avoid the situation that collective agreements are driven excessively by a limited number of the best performing firms.

Strong contract enforcement, efficient civil justice and timely bankruptcy procedures are important to encourage the growth of productive start-ups that generate a high share of new employment (OECD, 2016d). An efficient insolvency regime encourages entrepreneurs to take the risk to start a new business and is positively associated with entrepreneurship development and productivity growth (de Serres, 2006; OECD, 2016d). It also allows entrepreneurs to move on quickly to try again if they fail. The efficiency of both personal and corporate insolvency regimes has increased with reforms in 2014 and 2015, but there is room for improvement. Spain has introduced a “fresh start”: the exemption of future earnings from obligations to repay past debt following bankruptcy. If certain conditions, including the repayment of a certain percentage of debt, are fulfilled entrepreneurs are immediately exempt from repaying debt from future earnings. However, when this payment threshold is not met, the debtor has to commit to a five year payment plan for the debt exempt from immediate discharge, which remains high in international perspective (Carcea et al., 2015). In cases when debt forgiveness is not automatic, reducing the period during which bankrupt entrepreneurs are required to repay past debt would make it possible for entrepreneurs to start over and begin hiring and producing sooner.

Boosting innovation, and ensuring that capital goes to a wider set of innovative firms

Spanish firms invest little in knowledge assets, not only R&D but also other innovation and business capabilities that matter for innovation (OECD, 2015e). The state provides dedicated public financing for innovation investments in the business sector via R&D tax credits and government direct funding programmes. Spain’s R&D tax credit system is generous in international comparison, but few firms use the system in part because of complex procedural requirements. To boost take up, the procedures should be simplified and well publicised. Moreover, in the past few years, a significant part of the government budget for innovation was not spent because it was allocated to loans to firms for R&D but the loans were not taken up. To improve the effectiveness of R&D support, the government should favour the financing of performance based grants and public-private collaborative projects to increase firms’ R&D and to slow the very high brain drain of talented researchers over the financing of repayable loans.

To foster firm productivity it will be important to ensure that financing goes to the most promising projects. The successful recapitalisation of the banking system following the crisis has laid the foundations for a better allocation of capital in Spain. The authorities have also taken measures to expand capital market finance, introducing an alternative fixed-income securities market, MARF, and an alternative stock market, MAB. Both are expanding, but to gain access to the market a firm still has to be reasonably large with an average bond issue size on the MARF of EUR 20 million (Guijarro and Mañueco, 2013).

Improving the flow of capital to a wider class of new innovative firms requires more education for entrepreneurs on how to access finance. It also requires making banking and capital markets work more in tandem to combine banks’ in-depth knowledge of individual clients with the capacity of capital markets to spread risk widely. This is especially important for SMEs, which have more difficulties than large firms accessing either of these channels because their high riskiness impedes their access to bank finance and a lack of information and their size impedes them from accessing capital markets.

To increase the flow of funds to SMEs more can be done to tailor securitisation and mutual guarantee schemes to make it more attractive to list and buy securitised SME debt on MARF or MAB. The government could introduce risk sharing mechanisms, such as providing guarantees to SME bond funds that purchase either loans securitised by banks or smaller bonds issued directly by small firms. To reduce financial risks, the banks originating the loans should be required to retain a stake and the loans should be mutually guaranteed by the banks themselves, as is done in France with bond issues as low as EUR 500 000 (OECD, 2015f).

State funding for firms can be better prioritised. The state-owned bank Instituto de Crédito Oficial (ICO) provides second-floor facilities funds to SMEs where commercial banks assume the credit risk of the loan. In addition ICO provides direct financing activities directed to large projects in different economic sectors. ICO should encourage banks to focus more on lending to innovative companies. ICO also provides equity capital via several instruments. One of these is a “fund of funds” public venture capital fund, Fond-ICO Global, introduced in 2013. Fond-ICO Global should put emphasis at the early and late stages of the venture capital cycle, where there is less provision of private capital.

The public national innovation company (ENISA) helps to finance early stage start-ups, allowing them to establish a long enough track record to convince private venture capitalists to invest. ENISA’s funding is very modest, though has increased recently. The government should consider further increasing ENISA’s funding subject to the overall expenditure review because it plays a complementary role to market finance. It funds early stage start-ups that would not be financed by the private sector, allowing these firms to establish a long enough track record to convince private venture capitalists to invest.

Centro de Desarrollo Tecnológico Industrial (CDTI) is the main public actor funding business R&D and innovation projects in Spain. The “Innvierte” programme of CDTI aims to promote business innovation by supporting venture capital investment in technology based and innovative companies and to foster the entry of private venture capital to support their technological activities and internationalisation. The CDTI’s share of funding available for grants has declined over time and there should be a partial shift of loan funding towards grants, especially to SMEs with technological and innovative development projects.

Making growth greener

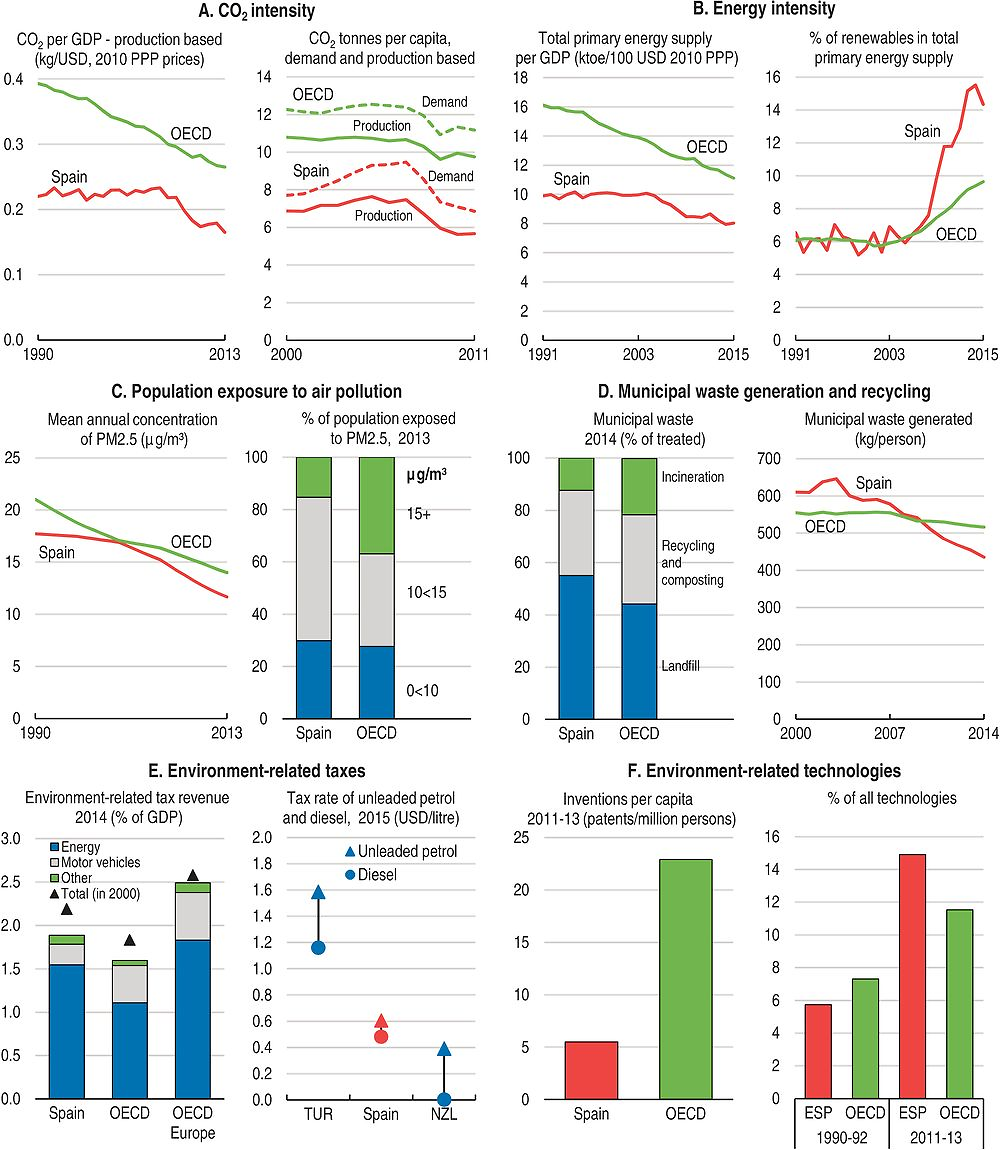

Over the past decade, Spain reduced the carbon, energy and resource intensity of its economy despite the financial crisis and following recession and significantly expanded protected natural areas (OECD, 2015f). Yet, important environmental pressures remain (Figure 29). Spain is committed to fulfil jointly with other EU member states the 2020 target of reducing GHG emissions by 20% from 1990 levels. Moreover, Spain aims to reduce its non-ETS GHG emissions by 10% from 2005 levels by 2020. Making the tax system more environmentally friendly, on which there has been little progress recently (Table 7), would help to reach that goal. Spain remains less successful than many countries in making use of waste either by recycling or recovering energy in incineration; landfill remains the main treatment method for municipal waste and its share has increased in recent years.

Source: OECD (2016), Green Growth Indicators (database). For detailed metadata, see http://stats.oecd.org/wbos/fileview2.aspx?IDFile=02a134e1-c3ec-4c5c-9a05-4ebb41a60539.