United Kingdom

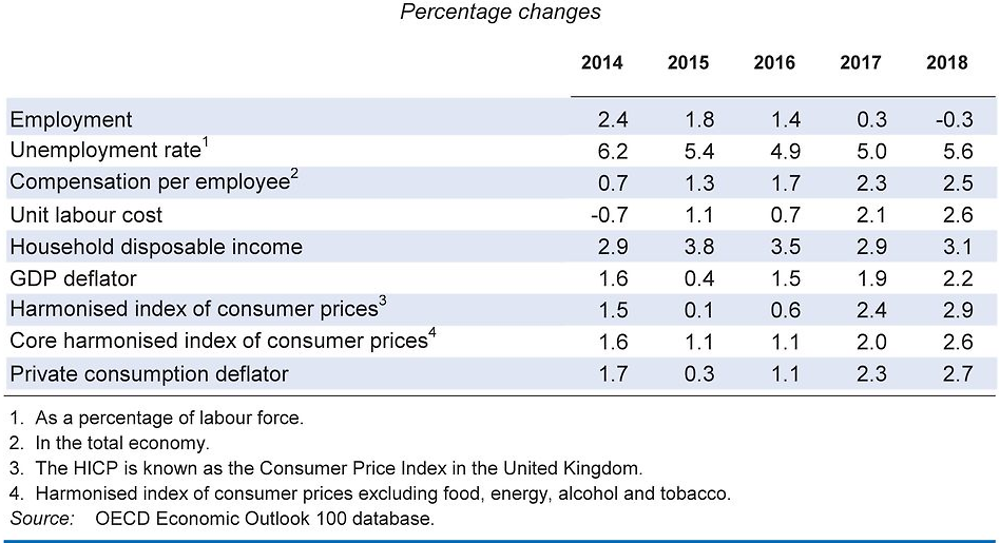

The Brexit referendum vote has reduced growth prospects and increased volatility, as reflected by the large currency depreciation. Monetary policy has mitigated the immediate impact of the shock by stabilising financial markets and shoring up consumer confidence. This projection assumes the United Kingdom will operate with a most favoured nation status after 2019, but there is considerable uncertainty about this, which will increasingly weigh on growth, and in particular private investment, including foreign direct investment. Higher inflation is projected to hit households’ purchasing power and to reduce corporate margins, weakening private consumption and investment. As growth slows, the unemployment rate is projected to rise.

Macroeconomic policies need to be expansionary. Inflation is set to exceed the target of 2%, but the monetary policy stance is expected to be unchanged as the inflationary impact of currency depreciation should be temporary. The latest government plans released in the Autumn Statement indicate a slower pace of fiscal consolidation and some increase in public investment. A more significant increase in public investment would support demand in the near term and boost supply in the longer term. With a weak economic outlook, further raises in the minimum wage should be considered prudently.

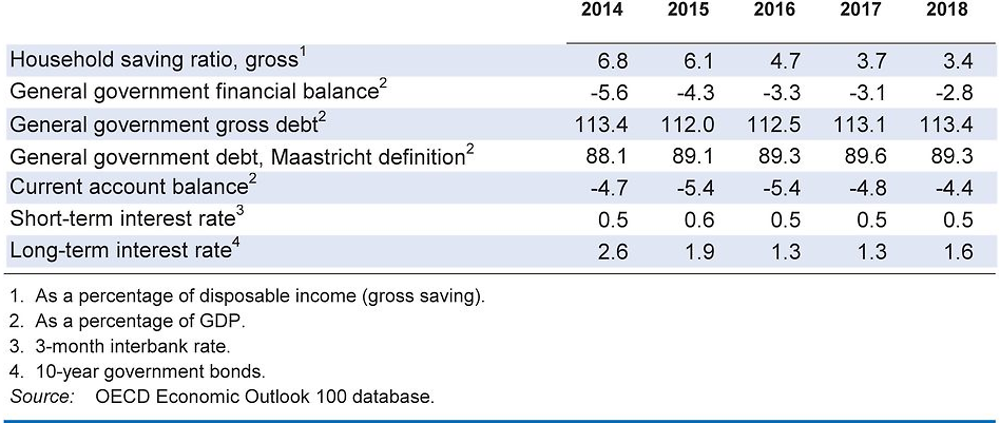

Despite recent increases, long-term interest rates remain low, creating fiscal space as debt service obligations fall. Reducing tax expenditures and adopting a single VAT rate would improve both efficiency and fairness, but would require flanking policies to protect the poor. More spending on physical infrastructure and skills in regions lagging behind would raise productivity and wages, making fiscal policy more inclusive.

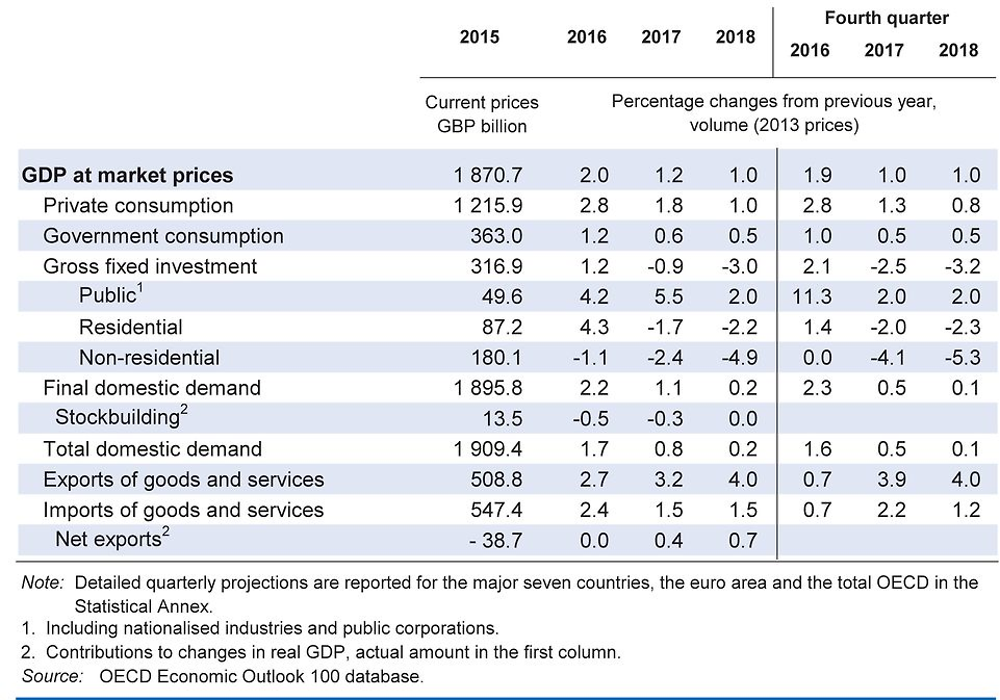

Economic activity has weakened

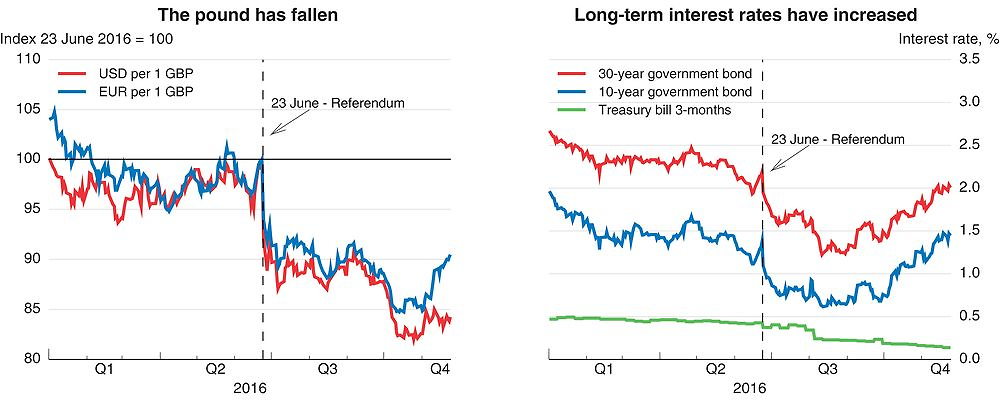

Growth momentum was strong in the run-up to the European Union referendum but has since weakened. Monetary stimulus has, however, eased the near-term drag on growth from the decision to leave the European Union. Consumer confidence has rebounded, but businesses have revised down significantly their outlook for hiring, capital expenditure and discretionary spending. Uncertainty about the United Kingdom’s relationships with the rest of the world is high, and the risk of exit from the European Union’s single market and customs union has pushed the exchange rate to new lows and lifted long-term interest rates.

Source: Thomson Reuters.

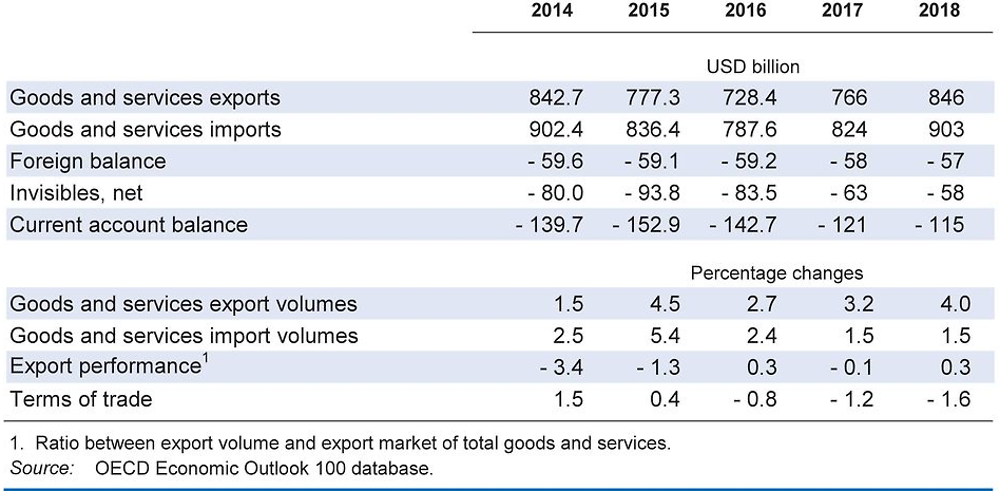

Trade data suggest that currency depreciation has supported exports, but imports have fallen. The current account deficit remains sizeable, at 5¾ per cent of GDP, driven by lower returns on external assets relative to the return on domestic assets held by foreigners, and by exports which have been growing less than UK export markets.

The labour market has been resilient, with the unemployment rate inching down to 4.8%, although job creation has moderated. Real wages have been growing at a time of low inflation, but the fall of the exchange rate has started to increase price pressures. Caution is needed with the implementation of the policy to raise the National Living Wage to 60% of median hourly earnings by 2020. The effects on employment need to be carefully assessed before any further increases are adopted, especially as growth slows and labour markets weaken. Rolling out the universal credit should sharpen work incentives, but better skills are also needed to create better jobs. The planned introduction of an apprenticeship levy on large businesses will be an important step to support the development of vocational skills across all firms. Higher spending on active labour market policies would help upskilling and the reallocation of labour from the non-tradable to the tradable sectors underpinned by a weaker exchange rate, which should enhance productivity over time.

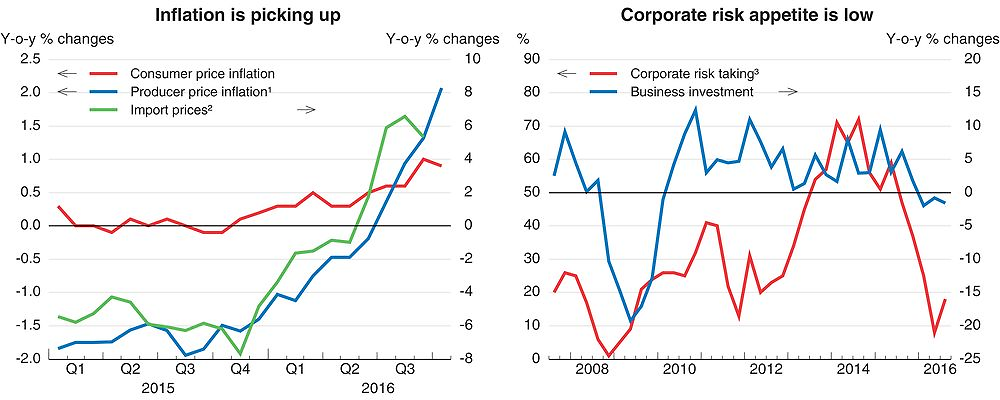

1. Net sector output prices of manufactured products.

2. Import prices of total trade in goods.

3. Percentage of CFOs who think this is a good time to take greater risk onto their balance sheets. The survey was conducted between 12 and 26 September.

Source: Office for National Statistics; and Deloitte.

The macroeconomic policy stance needs to be expansionary

Fiscal space has increased, as very low interest rates have reduced debt-service costs, and to the extent that interest payments collected by the Bank of England under its quantitative easing measures are transferred to the budget. The government has appropriately indicated that it is no longer targeting a budget surplus by the end of the decade and has signalled that the automatic stabilisers will be allowed to work. Some discretionary fiscal measures will be used to increase infrastructure spending, which should support short-run economic activity and enhance long-term growth, but further fiscal tightening is planned overall by the authorities.

The Bank of England has taken a number of measures to support liquidity and lending in the aftermath of the EU referendum, including long-term refinancing operations and the reduction of the counter-cyclical capital buffer to 0%. In early August, the Bank cut the policy rate by 25 basis points to 0.25%, adopted a Term Funding Scheme to further lower refinancing costs for banks that lend, and restarted its quantitative easing programme with the purchase of GBP 70 billion (3.5% of GDP) of assets. Inflation is expected to exceed the 2% inflation target, but the extent of monetary stimulus should be maintained to ease the cost of economic adjustment to the departure from the European Union.

There is room to make the tax system more efficient. Income tax expenditures are large and reducing them in certain areas would improve resource allocation and productivity. Removing preferential and zero value-added tax rates would also reduce distortions and in some cases make the system fairer (many favoured items are consumed by the rich), although this would require adjustment to welfare programmes to combat inequality.

Growth is projected to slow down

Growth is set to weaken significantly. Private investment is expected to contract amid large uncertainty. Private consumption growth is projected to slow, as the currency depreciation that has already taken place reduces real earnings growth. Export growth is projected to pick up, driven by a weaker exchange rate, allowing some gains in market share, and the current account deficit will narrow gradually. Weaker growth should raise the unemployment rate to above 5%.

The unpredictability of the exit process from the European Union is a major downside risk for the economy. Uncertainty could hamper domestic and foreign investment more than projected and the pass-through of currency depreciation to prices could be larger, deepening the extent of stagflation. Subdued world trade growth could limit the effect of depreciation on exports. The large current account deficit may be harder to finance, although weaker-than-projected consumption and imports would reduce the deficit eventually. Improved prospects of an orderly exit from the European Union while retaining strong trade linkages with the bloc would support near-term growth more than projected.