Italy

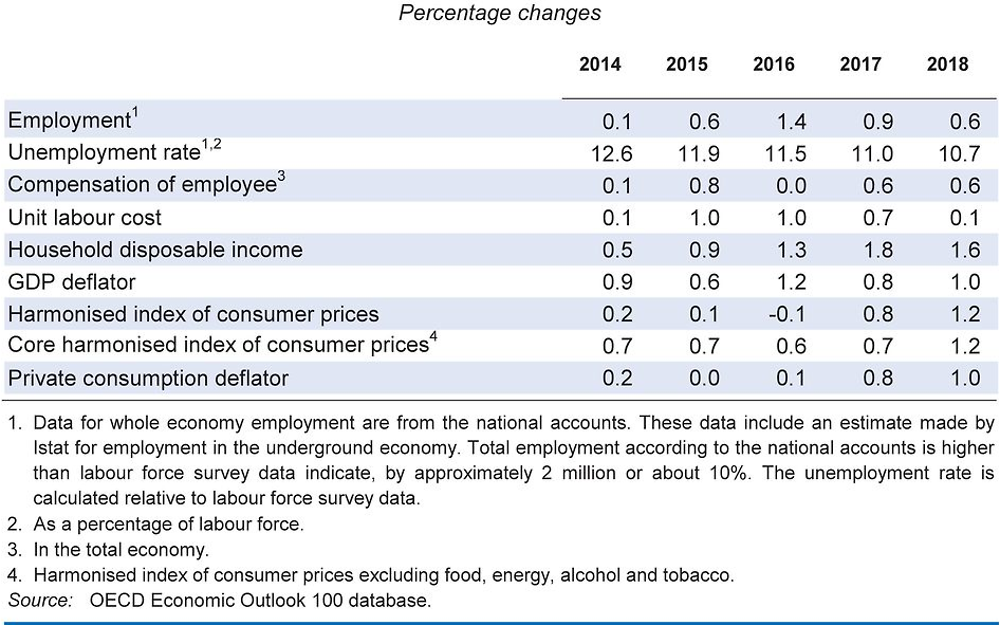

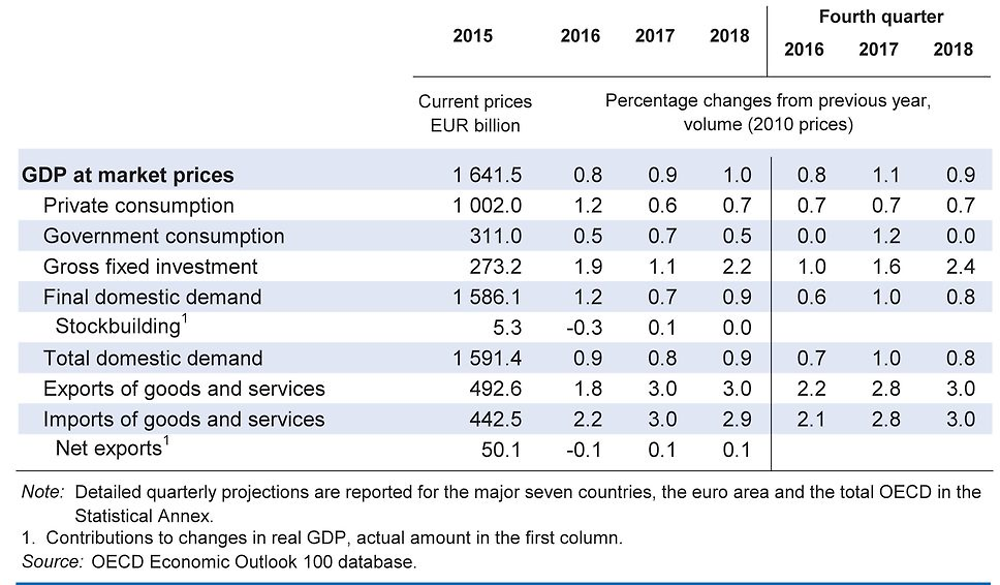

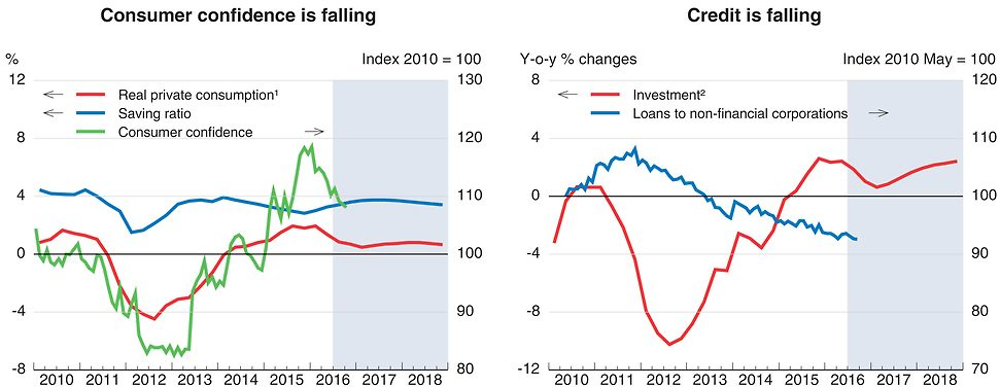

The economy will grow by 0.9% in 2017 and 1% in 2018. Despite stronger job gains, private consumption growth has weakened following rising uncertainty and declining consumer confidence. The large stock of non-performing loans and the uncertain recovery keep hampering banks' loan disbursements, hindering the recovery of investment. Low growth in Italy’s export markets and geopolitical tensions are restraining exports.

Accommodative euro-area monetary conditions are supporting the moderate recovery. The 2017 budget will appropriately support growth, and a further fiscal easing is assumed in 2018. Nonetheless, lower interest payments will help keep the budget deficit stable. The government is making progress on structural reforms, including active labour market policies, the public administration and the school system. The planned constitutional reform, subject to a referendum in December, would be a further step forward in the reform process and would enhance political and economic governance.

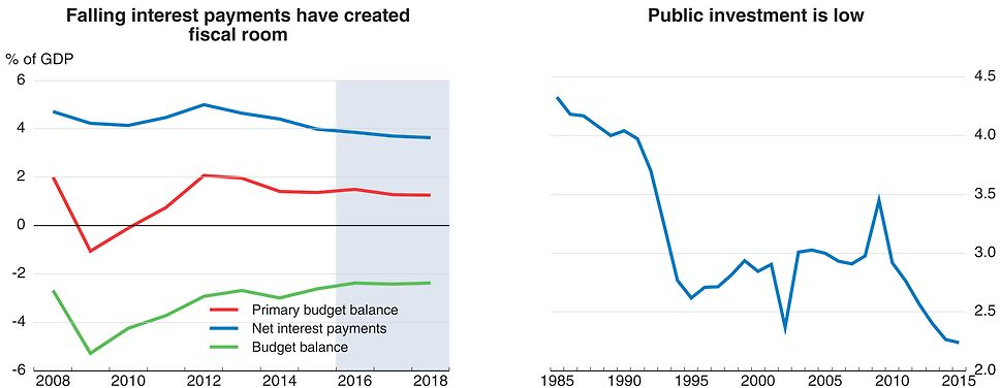

Since 2012, yearly interest payments have declined by more than EUR 15 billion (nearly 1% of GDP), generating fiscal space. The authorities need to use it to raise public investment, enhance targeted programmes to fight poverty and raise labour market participation, especially among women and the young, and encourage innovation.

Rising uncertainty has slowed household consumption growth

The self-reinforcing cycle of higher employment, household income and private consumption that began in early 2015 due to the Jobs Act, social security contribution exemptions and fiscal easing has weakened because of rising uncertainty and weaker consumer confidence. Employment has continued to expand, and this has drawn more workers, in particular women, into the labour market. Increasing labour market participation has prevented a faster decline in the unemployment rate. Real wages have risen thanks to persistently low consumer price inflation stemming from still sizeable economic slack. Further positive developments in the labour market will be key to more inclusive and stronger growth going forward.

1. Year-on-year percentage changes.

2. Real gross fixed capital formation.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 100 database; and Bank of Italy.

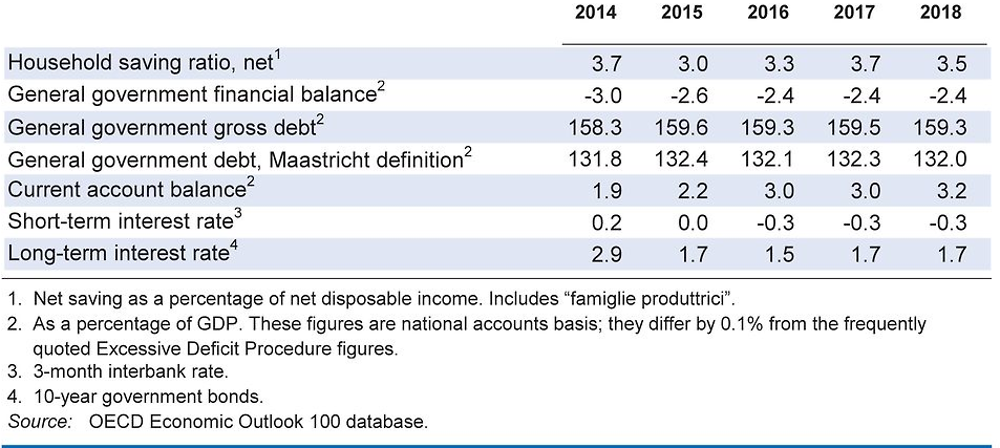

Investment growth remains lower than in previous recoveries. Credit to firms has been shrinking for some time as uncertain economic prospects and excess capacity have cut firms’ demand for credit. Also, the still high stock of bad loans (about 18% of all loans to non-financial corporations) restricts credit supply.

Growth-enhancing fiscal policy is needed to complement structural reforms

The government budget deficit is estimated to decline to 2.4% of GDP in 2016 from 2.6% in 2015. The 2017 budget provides a range of incentives to boost investment and innovation and lowers the corporate income tax rate from 27.5 to 24%. It also extends for two years social security contribution exemptions for new permanent contracts, but limits them to newly-hired students who have completed internships at the firm. It also raises spending on low pensions and, to a much lesser extent, family benefits and the income-support scheme for the poor. The government plans to negotiate with the European Union a fiscal leeway amounting to about 0.4% of GDP on the ground of exceptional economic circumstances linked to the recent earthquake, the refugee crisis and infrastructure investment. Lower interest payments and the mild economic expansion will keep the headline budget deficit at 2.4% of GDP in 2017 and 2018. This fiscal stance is broadly appropriate provided that the available fiscal space is used to finance policies leading to faster and more sustainable growth.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 100 database.

Lower interest payments, linked to very low interest rates, have generated substantial fiscal space. Since 2012 the effective interest rate on the public debt has declined by around a third, to about 3%, cutting interest payments by about 20%. The authorities should use this room to restore public investment, which has dropped in nominal terms by more than 30% since the start of the crisis, to 2.2% of GDP, the lowest level in more than 25 years. Raising public investment will accelerate growth and help reduce the debt ratio. Priorities could include a multi-year programme to make buildings earthquake proof and promoting decarbonisation of the economy in line with the COP21 goal. In addition, education spending and family benefits, which are low for an OECD country, should be raised to increase productivity and alleviate poverty.

Continuing and deepening structural reforms will be fundamental to raising living standards for all Italians. The constitutional reform that will be subject to a referendum in December would be a step forward as it would streamline the legislative process and clarify the division of responsibilities between the central and local governments that has hindered public and private investment. More can be done to make the taxation system fairer and more effective, primarily by permanently cutting social security contributions on lower income and shifting taxation towards consumption and immovable property. Fighting high poverty among families with children through a targeted national programme should be a priority. Strengthening the provision of good quality care for children and the elderly would help permanently raise labour market participation among women.

The economy will continue to expand moderately

GDP growth is estimated to be 0.8% in 2016, and is projected to edge up to 1% by 2018. Uncertainties concerning the banking sector and the effect of Brexit will moderate private consumption growth in 2017. In 2018, the expiration of social security contribution exemptions will mitigate employment growth. The moderate economic expansion and credit supply constraints linked to bad loans will curb private investment. Low growth in the euro area and other main trading partners will keep restraining sales abroad.

The resolution of uncertainties surrounding the banking sector and Brexit could help restore consumer confidence, leading to faster private consumption growth than expected. Faster progress on reducing bad loans would mitigate credit supply constraints. The planned increase in public investment could also be faster and more effective than anticipated, although implementation delays would have the opposite effect. Exports may benefit more than envisaged from expansionary policies in large non-EU economies. On the other hand, renewed financial market turmoil in the euro area or an aggravation of banks' balance sheet problems could drive risk spreads higher, raise debt financing costs and require a fiscal retrenchment. The refugee crisis could again intensify, straining government finances and capacity to deal with a larger influx of immigrants. Higher oil and energy prices would diminish household purchasing power, lowering private consumption. A new wave of trade protectionism would hinder exports to non-EU countries.