Chapter 3. Strengthening the employability of Peruvian youth

This chapter discusses the role of labour market and social policies in increasing the employability of young people in Peru and assesses the impact of skills mismatches on school-to-work transitions. The key challenges it identifies include: the ability of the public employment services to deliver effective activation to vulnerable youth; the capacity of the current social protection system to provide them with adequate income support; and ensuring that youth are provided with the right qualifications to match the needs of the labour market. The chapter provides a set of policy options that may help address each of these issues. It also points to the important role that broader policies to foster the diversification of the economy can play to support the demand of quality jobs for Peruvian youth.

3.1. Introduction

Improving the employability of youth in Peru entails bringing as many young job seekers and inactive people into the labour force and into jobs. Engaging youth in (formal) labour market involves ensuring that they have the incentives to seek employment thanks to the supportive role of: (i) high quality public employment intermediation services and active labour market programmes; and (ii) unemployment insurance and social assistance schemes at least partly conditioned on active job search in the formal sector. Additionally, it requires a set of policies to avoid misalignment between the supply and demand for skills. The skills mismatch indeed hampers the smooth integration in the labour market of job seekers, on top of generating substantial productivity losses due to misallocation of workers to jobs.

This chapter provides a comprehensive analysis of all three aforementioned components. It points to the following challenges:

-

Much can be done to strengthen the still limited, capacity of the public employment services (PES) to provide effective activation of unemployed or inactive youth. PES are severely understaffed in Peru and the country invests too little in Active Labour Market Programmes (ALMPs).

-

Unemployment insurance is missing in Peru and social assistance does not compensate for this absence. The unemployment benefit system currently in force, which relies on severance payments (provided the dismissal is judged as unfair) and compensation for length of service (the so-called CTS introduced in Chapter 2), does not provide adequate support to unemployed workers. While severance payments are not automatic, recent regulatory changes have dampened the capacity of the CTS to work as a safety net during unemployment. Additionally, low coverage and low levels of social assistance exacerbate the risk that unemployed Peruvian youth fall into poverty. Finally, access to the unemployment benefits is not conditioned on active job search, which reduces the incentives unemployed workers have to rely on PES.

-

The Peruvian labour market is characterized by substantial over-qualification and field-of-study mismatch. Peru has experienced a dramatic increase in school enrolment and educational attainments. Yet, the quality of education has not kept up with the pace of change, suggesting that graduates’ qualifications overestimate the actual skills acquired.

-

The demand for high-skilled labour remains sluggish. Many low-skilled positions continue to prevail among the occupations that are in short supply. At the same time, the demand for several high-skilled professions that require specific specializations and therefore do not leave much space for substitution with graduates of different field-of-study, is also becoming increasingly important.

Box 3.1 sets out the policy recommendations to help address the above challenges and better integrate Peruvian youth in the labour market.

To eliminate the barriers hampering the employability of Peruvian youth the OECD suggests to:

Increase resources and staff for Public Employment Services (PES)

-

Expand and increase the efficiency of PES by strengthening recruitment and training programmes for caseworkers.

-

Widen the range of modern outreach methods to engage with the most deprived NEETs. The recent experience of the OECD-EU countries suggests that a key to reach out to the NEETs population is by bringing PES services closer to the places where the NEETs meet.

-

Compatible with the resources that PES can display, strengthen the efforts to provide the NEETs with tailored job placement and intermediation services relying on personalised approaches.

Enhance ALMP provision

-

Remove current administrative barriers that hamper the engagement of the Peruvian business sector in on-the-job training programmes.

-

Strengthen the training component of public work programmes. Further to providing income support, public work programmes have the potential to improve skills and therefore promote labour force participation. Trabaja Perù could benefit from a strong training component.

-

Make employment support measures, such as temporary jobs in the non-market sector or hiring subsidies in the market sector, conditional upon getting a certification of skills at the end of the employment period, at least for previously unskilled youth.

-

Support the development of an impact evaluation culture. For example, the Ministry of Labour and Employment Promotion could build on the experience of the Ministry of Education that launched the MineduLAB in 2016. A similar approach could be used to assess the performance of ALMPs.

Re-design the unemployment benefit system

-

Improve the effectiveness of the unemployment benefit system. An immediate solution would involve strengthening restrictions on CTS withdrawals until the event of unemployment.

-

As a long term strategy, consider re-designing the current unemployment benefit scheme. This could be achieved by drawing, for example, on the strengths of the Chilean system that combines a system of individual saving accounts with a common solidarity fund and encourages job search.

Target social assistance to unemployed people

-

Tackle social assistance programmes to make them better geared to the needs of jobless youth deprived of unemployment benefit, while at the same time making recipiency conditional upon active job search. This may require introducing a Jobseeker Allowance, in the form of a non-contributory unemployment benefit conditional upon registering with PES and intensely engaging in job search. Adding conditionality to Juntos transfer obliging capable beneficiaries to participate in a comprehensive activation strategy could be a viable alternative.

-

Take measures to increase access to affordable digital infrastructure, especially in remote rural areas. An immediate solution that could ease the lack of access to Internet could consist in the creation of toll-free kiosks with PC terminals in regional offices of the Centro de Empleo.

Continue efforts to reduce the prevalence of over-qualification and field-of-study mismatch

-

Strengthen the role of existing web portals, such as the Ponte en Carrera observatory and other instruments, such as SOVIO and Proyecta tu Futuro, to ensure that they can support students with effective information about available study options and professional career paths after graduation.

-

Develop skills assessment and anticipation exercises to provide guidance on future skills demands as tools to mitigate the incidence of skills shortages and mismatches. In addition, a regular assessment framework would allow tracking progress towards the achievement of policy objectives.

-

Strengthen the role of policy co-ordination to achieve better skills outcomes through expanding horizontal collaborations among ministries and vertical collaborations across levels of government.

-

Continue efforts to foster the role of collaborations between public and private sector actors with a stake in, and an influence on, skills outcomes. Stronger partnership can increase the relevance of skills developed in VET and higher education.

-

Similarly, consider measures to engage the business sector in the design and implementation of ALMPs. Their involvement in training and activation could enhance the skills impact of these programmes and their attractiveness to those searching for jobs.

Strengthen the demand for quality jobs for youth as recommended by the OECD Multi-dimensional Review of Peru

-

In depth analysis using the OECD’s Skills for Job Indicators, confirms the importance for policy makers to factor in the complementary role of pro-growth policies, which are essential to sustain the creation of more and better quality jobs. In line with the recommendations of the OECD Multi-dimensional Review of Peru, this highlights the importance of maintaining the focus on the broad mix of macroeconomic and structural reform policies that have the highest potential to set Peru on path of more diversified and inclusive long-term economic growth. Important as they are the policies to strengthen employability and to support the supply of qualifications and skills will hardly be enough, if left alone, to boost youth employment in Peru.

3.2. Delivering public employment services that work for youth

Activating the human capital of 1.7 million Peruvian NEETs critically requires the support of PES. The first role PES system plays in tackling youth inactivity is that of labour market intermediary. Namely, it can help increase the efficiency of the job matching process by reducing transaction costs of job search and diminishing information asymmetry. Secondly, PES has a role to play in redressing skill imbalances and labour market flaws, provided that it is supported by a wide array of ALMPs. Thanks to their ability to secure work-to-work transition and to insure labour income, PES and ALMPs are essential pillars to build resilient and adaptable labour markets.

In line with the objective set out in the Constitution to promote effective employment policies, the Peruvian Ministry of Labour and Employment Promotion (MTPE) has been implementing a series of measures since the mid-90s to boost employment outcomes for the most vulnerable people. Reforming the provision of public employment services was a landmark in this process. In 2012, the decentralized network of intermediation centres at the national level, CIL-Proempleo, was put under the umbrella of a new body for the coordination of employment services – Centro de Empleo (Employment Centre, initially referred to as a Single Window for the Promotion of Employment, Ventanilla Única de Promoción del Empleo).

The Employment Centre, like many other PES authorities across the LAC region, is organized as a line department of the Ministry of Labour, rather than as a separate public agency reporting to the government (IDB, WAPES and OECD, 2015). It has a ‘territorial hierarchical structure’ spanning three levels: national, regional and local. At the national level, the MTPE sets the direction of labour policy for the country. The regional authorities assume responsibility for providing services through the offices of the Employment Centre (Centros de Empleo). The local governments support the operation of employment services through the network of Employment Offices (referred to as Officinas de Empleo). Currently, service delivery of the Peruvian PES is operated by 33 Employment Centres and 29 Employment Offices, which work as a one-stop-shop, a single contact point where jobseekers can receive employment support free of charge. Several services are intermediated through an online national jobs portal http://senep.trabajo.gob.pe:8080/empleoperu/Pedido.do?method=inicio. Activities of the Employment Centre are funded from public sources and donors; in 2016 its budget amounted to PEN 8 650 000 (i.e. USD 2.6 million or EUR 2.3 million), which constitutes a tiny, 0.0015%, share of GDP. For comparison, OECD countries spend on average 0.05% of their GDPs for placement and related services only.

As of 2017, the Employment Centres provide twelve types of services for both jobseekers and employers (See Box 3.2 for details). In principle, this service structure should enable the Centres to play a key job broker role in Peru, offering vacancy databases and referrals of candidates. The Centre is also the primary government institution for implementing ALMPs dedicated to youth and vulnerable populations. In practice, however, few unemployed young people rely on public employment services in Peru.

Targeted to individual jobseekers

1. Bolsa de Trabajo (Employment exchange) - This is a job broking service that provides labour intermediation between job seekers and companies, matching candidates to available vacancies in PES job bank. The job bank can be accessed following two modalities: in-person at employment centre offices and employment offices, or virtually through the Employment Centre web portal (http://senep.trabajo.gob.pe:8080/empleoperu/Pedido.do?method=inicio). The service targets the youth population, for the main.

2. Asesoría para la Búsqueda de Empleo (Advisory service of job search) - This employment search counselling service provides advice and guidance on effective strategies and techniques to successfully undergo a personnel evaluation process. The service is targeted in particular at young individuals. It aims to improve chances of getting and retaining a job. The series of internal and external workshops as well as personalized advice can be accessed through the employment promotion offices of the Employment Centres.

3. Certificado Único Laboral (Single labour certificate) - The aim of this fast-track procedure is to provide a unified document, which integrates and verifies information typically required by employers during the recruitment process that would otherwise be sparsely collected: identity documents, police record, education and training authentication and labour career. The service is targeted at individuals aged18-29 and is free of charge.

4. Empleo Temporal (Temporary employment) - As part of the Trabaja Perú programme, this service offers temporary public work jobs in various social and economic infrastructure projects. It is targeted at unemployed people with families, giving priority to: heads of household who have at least one child under 18 years of age; single mothers; people with disabilities; young people between 18 and 29 years of age who assume family responsibilities without being parents.

5. Capacitación Laboral (Job training) - Provided through the programmes Jóvenes Productivos and Impulsa Perú, this facility aims at improving employability and labour productivity of job seekers and workers, through a range of labour training courses strongly focussed on the acquisition of practical skills. In addition, beneficiaries receive guidance on the preparation of their curriculum vitae and advice on how to prepare for a job interview. It is targeted at young people aged 15-29 who are unemployed and live in poverty or extreme poverty, as well as people over 29 who are unemployed, or workers at risk of losing job.

6. Certificación de Competencias Laborales (Labour skills certification) - Through the programme Impulsa Perú this facility addresses dependent and independent workers who want to formally evaluate and recognize the labour competences that they have acquired through work experience. The programme aims to enhance career perspectives, self-esteem and motivation of workers with possible returns on their productivity and the competitiveness of companies. The labour competences assessment process can be carried out in the same place of work or in a certified evaluation centre.

7. Información del Mercado de Trabajo (Labour market information) - This service targets individuals who look for information on the labour market at the national, regional and local levels. The service provides comprehensive information on 1) occupational profiles and characteristics of job seekers and companies; 2) average wages by occupation; and 3) most demanded occupations. It supports job counselling and the employment exchange services.

Targeted to youth still in education

8 Orientación Vocacional e Informacion Ocupacional (Vocational guidance and occupational information) – These services are implemented under the SOVIO initiative which provides guidance to young people aiming to facilitate the choice of professional, technical or occupational career and to assist school to work transitions. The service offered by the Employment Centre consists of three stages: orientation and information talk, evaluation with psychological tests and delivery of vocational report accompanied by advice on the subject.

Targeted to job seekers wishing to become entrepreneurs

9 Orientación para el emprendimiento (Guidance for entrepreneurship) - This program is aimed at individuals who look for information and guidance on possibilities of starting own business. Advice provided by the Centro de Empleo (Employment Centre) relies on the Geographical Information System for Entrepreneurs provided by the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics, which allows visualizing the degree of concentration of the businesses, annual volume of sales of these, characteristics of the population among others.

10 Capacitación para el emprendimiento (Training for entrepreneurship) - This programme provides training and advisory courses to help develop and carry out business ideas and plans. Applicants of the best business plans receive a start-up kit to facilitate the start of their business. The courses are targeted at young people between 15 and 29 years old, with little or no work experience, in a situation of poverty or extreme poverty, as well as unemployed and underemployed people. The service is offered through Jóvenes Productivos and Impulsa Peru programmes.

Targeted to companies

11 Acercamiento Empresarial (Business approach services) - These services are directed to formal companies to help them addressing staffing needs in three ways: personnel supply through job exchange channel, provision of labour training and certification of labour competences of workers.

Targeted to migrants

12 Orientación Migrante (Migrant orientation services) - These services target citizens who search for information and guidance on labour migration process or assistance when returning from migration. The service provides also training on productive use of remittances.

Source: MTPE Policy Questionnaire, Centro de Empleo web site, http://empleos.trabajo.gob.pe:8080/empleoperu/portal/quienessomos.jsp

3.2.1. Few unemployed youth use the public employment intermediation services

Public employment intermediation aims to increase the efficiency of job searching and the quality of the related job matching, through services such as counselling, mentoring, monitoring and assistance in the development of a job career plan. The Peruvian PES offers three main options of intermediation targeted at youth jobseekers (see points 1 to 3 in Box 3.2): the Employment exchange (matching job seekers with job vacancies), the Advisory service of job search (counselling involving support in preparing CV and job interviews) and the Single labour certificate (a fast-track free-of-charge procedure, introduced in 2010, to help young people gathering a defined set of official documents, typically requested by employers in the formal sector).

In 2016, only around 5.5% of unemployed Peruvian youth in the age range between 15 and 29 years old sought work through referring to PES (Ministerio de Trabajo y Promoción del Empleo, MTPE, 2016). This figure cannot be easily evaluated in the international context, reflecting the fact that institutional characteristics and the resources each country can make available for PES vary. Nonetheless, the comparison between Peru and a selection of European OECD member countries suggests that the share of unemployed young people who are served by PES is significantly lower in Peru (Figure 3.1). For the European OECD countries shown by Figure 3.1, it ranges between 13.5% (Iceland) and close to 94% (Belgium), with the sample average being 47.6%.

ENAHO survey figures shed interesting light on the key drivers behind the low take up by unemployed youth of the services provided by PES (Figure 3.2). These figures clearly point to the role of the social network (through friends and relatives) and reaching out directly to employers as the two most preferred job-search options used by the youth. The two approaches account for roughly two-thirds of the total number of answers collected through the survey. Many workers (especially those who are relatively low skilled) do not need to refer to the labour intermediation institutions because they look for a job in the informal sector.

Past empirical analysis reveals that trust in the services provided by PES is fairly limited in Peru (e.g., Vera, 2005). Nevertheless, considerable progress has been achieved during the past years to address challenges and to increase the capacity of the Employment Centre to reach out to young people. This has been helped by the creation of a new online platform providing broader access to some services and the introduction of the Single Labour Certificate service. Progress is visible from the fact that the total number of youth clients that PES was able to serve was roughly three times higher in 2016 than in 2010. Much of the progress achieved rests on the introduction of the Single Labour Certificate service, whose main objective has been the simplification of administrative procedures.1

3.2.2. And few unemployed youth participate in other types of Active Labour Market Programmes

Other than intermediation services, such as job matching and counselling, for example, one important aspect characterising the activities of the Employment Centre is the focus on the activation of vulnerable populations and youth. In the OECD countries Active Labour Market Programmes (ALMP) involve various mechanisms, ranging from training (in classroom and/or on-the-job) and direct job creation services (in the public sector), to employment incentives (i.e. the payment of a portion of the worker’s salary or reductions in employers’ social security contributions over a specified period of time) and start-up incentives. In some countries, they can also include subsidies to the employment of people with disability and a long-term incapacity to work, vocational rehabilitation and sheltered employment programmes. As far as Peru is concerned, the main programmes implemented through PES are focussed on training (Jóvenes Productivos and Impulsa Perú) and public works (Trabaja Perú). Neither employment incentives, nor sheltered employment are part of the ALMP provided by the Ministry of Labour and Employment Promotion or the Ministry of Production (see Box 3.3).

One primary objective of ALMPs in the OECD countries is to improve the employability of jobseekers and to reduce aggregate unemployment. However in many LAC countries, including Peru, ALMPs tend to address simultaneously several other long-term objectives on top of employability (Kluve, 2016). For example, public works programmes are often used as forms of social protection, becoming a viable alternative to passive social assistance measures, such as cash transfers. Community benefits resulting from public works programmes make them the most socially accepted form of support to the poorest populations.

Between 2011 and 2016 the three main programmes coordinated by the MTPE benefited around 165 000 youth. The country’s flagship ALMP that specifically targets the youth, Jóvenes Productivos reached roughly 100000 jobseekers, while Trabaja Perú and Impulsa Perú assisted around 38 000 and 26 000 young people, respectively. The international comparison suggests that participation in ALMPs remains significantly less frequent in Peru than in OECD countries. Taken as a percentage of the total labour force, in 2015 the share of Peruvians who participated in ALMP was as small as 0.2%, while the same rate for OECD on average exceeded 4% (Figure 3.3).

Programmes coordinated by the Ministry of Labour and Employment Promotion

Jóvenes Productivos (Productive Youth, continuation of Jóvenes a la Obra) is the flagship Peruvian ALMP programme focused specifically on youth. It targets in particular vulnerable population living in poverty and extreme poverty. Its objective is to facilitate access to the labour market and support entrepreneurial activities of young people. It involves two training programmes, for job placement and for the self-employed.

Trabaja Perú (Work Peru, continuation of Construyendo Perú) is a public work programme that aims to alleviate poverty through creating short-term employment opportunities for unskilled labour force. The activities supported by the programme focus on the construction of new infrastructures, such as schools, healthcare centres and roads, for example. Although the programme targets individuals aged 18-64, 25% of participants were youth (18-29) during the period between 2011 and 2016. More than two-thirds of overall participants are women. The job opportunities offered lack a training component.

Impulsa Perú (Boost Peru, continuation of Vamos Perú) targets the population aged 18-64, seeking to promote employment, improve job skills and increase employability levels. It includes three pillars: 1) training for job placement; 2) training for self-employment, and 3) certification of labour competences. The first two pillars focus on the unemployed and underemployed population, along with workers at risk of job loss, between 30 to 59 years. Both are complemented by a Labour Competences Certification component (targeted at individuals aged 18 to 59), which aims to validate and acknowledge capabilities of individuals acquired through work experience. The programme recognises work competences of candidates my means of the issuance of a certificate.

Perú Responsable (Responsible Peru) aims to promote Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Its three lines of action are: 1) employment promotion with emphasis on young people, people with disabilities and female heads of household; 2) strengthened employability through enhancing the competencies of the beneficiary population, including by means of vocational training centres; and 3) entrepreneurship promotion by means of the creation of opportunities for self-employment and initiatives of productive and formal entrepreneurship. Moreover the programme promotes the registration and the certification of companies that adopt social responsibility practices.

Fortalece Perú (Strengthen Peru) is a new labour intermediation programme launched in 2016. It focuses on disadvantaged regions (Arequipa, Ica, Lambayeque, La Libertad, Piura and San Martín, along with Metropolitan Lima). It aims to improve efficiency and pertinence of intermediation services offered by the Employment Centre.

Programmes coordinated by the Ministry of Production

MiEmpresa Propia (My own company) is a programme directed to foster entrepreneurship and includes services to support the expansion of small firms and the formalization of small- and micro-enterprises. These services comprise guidance and advice, the referral to a "one-stop shop" for formalization, advice regarding registration and taxation, and the provision of training vouchers for enterprises. MiImpresa Propia includes the New Entrepreneurial Initiatives (NIEs), a programme specifically targeted to start-up businesses. It offers training and advice to assist the development of new business ideas.

Start-up Perú is a new initiative targeted at entrepreneurs. It aims to stimulate the launch of new companies that offer innovative products and services with high technological content. A long term goal of the programme is to generate quality jobs and to reach out to foreign markets.

Innóvate Perú (the National Innovation Programme for Competitiveness and Productivity) aims to foster the adaptation of companies to technological change and to stimulate innovative entrepreneurship.

Source: MTPE’s answers to OECD Policy questionnaire, MTPE web service http://www2.trabajo.gob.pe/, PRODUCE web service http://www.produce.gob.pe/ and ILO Compendium of ALMP in LAC.

3.2.3. Factors explaining the limited capacity of PES to support activation

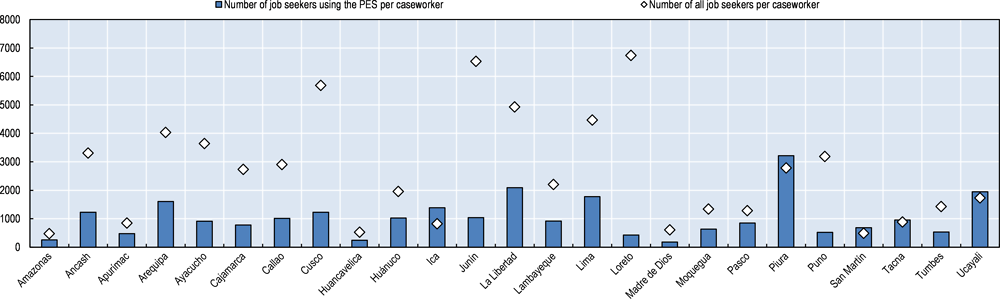

One important explanation of the limited capacity of Peruvian PES to boost the impact of activation policies is to be found in the fact that PES are severely understaffed by international standards. As of 2016, PES counted only 221 caseworkers, corresponding to a caseload rate of 1 300 PES users per caseworker. Although the average figure hides significant variations across regions (Figure 3.4), it makes for a very low number by international standards. For example, the average caseworker provides services to 202 jobseekers among OECD countries for which data are available (France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Spain and United Kingdom).

Furthermore, the international comparison shows that spending on ALMPs is very low to generate a significant impact (see Figure 3.5). In 2015, spending for the three largest Peruvian programmes (Jóvenes Productivos, Trabaja Perú and Impulsa Perú) amounted to around PEN 300 million (USD 90 million or EUR 80 million), corresponding to 0.05% of its GDP. As a benchmark, the OECD countries devote on average 0.4% of their GDP to labour market activation policies.

Further hindering the effectiveness of ALMPs in Peru, the limited human and financial resources available are not directed towards the programmes characterised by the highest potential to raise youth employability. The evidence available for the Latin American countries suggests that training programmes are particularly well suited to strengthen the integration of youth workers in the formal labour market (Escudero et. al., 2017). However, the largest share of spending for ALMPs (approximately 75%) is used for public works programmes that typically do not have a training vocation in Peru. Only 25% of this spending is destined to support the implementation of training programmes. By contrast, OECD countries mainly focus on training and employment/wage subsidies programmes that, at least in the OECD region, appear to work as a better option for re-integrating people who are at highest risk of exclusion from the labour market (Card, Kluve and Weber (forthcoming)).

3.2.4. Policy options for improving the role and attractiveness of employment services

Strengthening the capacity to reach out to young NEETs

The recent experience of several OECD-EU countries that have undertaken measures to widen the outreach activities of PES, with a view to strengthen the support provided to the most deprived low-skilled NEETs, would be beneficial for Peru to consider. This experience suggests the relevance of bringing PES services closer to the places where the NEETs meet. To this end, the European Network of Public Employment Services has proposed a strategy in four dimensions: i) Communication (disseminating information on PES offer); ii) Collaboration (building networks with partners); iii) Multichannelling (Providing new points of entry to PES through digital services); and iv) Low thresholds (One-stop-shops in easy access spaces) (EC, 2016 and EU 2015).

The practice to improve PES communication involves, among others, designating youth outreach workers and organising publicity campaigns. At the same time, the effectiveness of PES efforts to communicate with the NEETs could be strengthened by reinforcing the cooperation with the institutions that bring together young people. Intensive collaborations between PES, the schools and teachers, youth organizations and social activists can be instrumental to identifying school drop-outs and youth at risk of becoming NEETs. Examples of “detached” outreach models can be found in Sweden and UK, which have appointed ‘street marketers’ to provide direct street-based outreach to youth. Among the OECD countries, Italy and Norway have introduced innovative models of cooperation between PES and schools that help monitoring the attachment of young people to the labour market and enable early intervention. In addition, the Belgian Le Forem and German BIZ-mobil provide successful examples of multi-channelling, which uses a wide range of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tools to advertise PES services and organize ‘low threshold’ PES units, capable of implementing out field campaigns in remote areas using mobile centres. These experiences are summarised in (Box 3.4).

Tailoring services better to specific needs

More could be done to gear the assistance currently provided by the Peruvian Employment Centre towards the specific needs of the most disadvantaged youth. For the main, counselling and advice rely on group workshops in Peru. Recent steps to enable Jóvenes Productivos to select training centres for the implementation of specified curricula and to facilitate the intermediation between youth and the firm sector go in the right direction. SOVIO offers access to personalised career guidance. These experiences could be used to inform the development of a new model of personal guidance, aimed at labour market integration of disadvantaged youth.

Greater capacity will be essential to deliver effective employment services

The implementation of personalised services on a larger scale will require the support of adequate measures to expand the number of PES offices, as well as staffing levels. In considering these measures, priority should be given to the most remote regions, where shortages in infrastructure and human resources are largest. Moreover, since the recruitment and the training of new staff to equip them with the skills needed to operate effectively may require some time, partnerships with private employment agencies could be a viable option to alleviate capacity constraints of the Employment Centre in the short- to medium-term.

1. Unga-In - Sweden

The project was implemented between June 2012 and May 2014 in selected cities. It focussed on the creation of new outreach practices to communicate with the NEETs. As one key measure, it involved a team of young “marketers” supposed to reach out to vulnerable youth directly in the places most likely to be frequented by them (concerts, festivals and sport events). The programme was extensively advertised through multiple communication channels and was run in close cooperation with the schools.

2. Gang Advisers - UK

The initiative was designed by the UK PES in 2011, as part of the broader programme Ending Gang and Youth Violence. The strategy aims to engage vulnerable youth who are most at risk of becoming involved in gang activities. To this end, it uses a network of specialized outreach social workers, equipped with adequate skills to spot and reach out to the youth in their own environments. Such ‘Gang advisors’ provide a set of tailored advices with the ultimate goal being to succeed in getting them into education, training or employment.

3. Cooperation with education institutions - Italy

Italy has designed an innovative model of cooperation between schools and PES, which relies on data sharing between institutions. Twice per year the schools provide information to PES on early school dropouts. PES contacts the concerned youth directly to inform them about available support services and to encourage registration in PES.

4. Cooperation with education institutions - Norway

Norway has recently implemented a pilot programme to strengthen the effectiveness of the cooperation between the national public welfare agency (NAV) and the schools. Designated youth specialists are placed in high schools four days a week to provide vocational guidance and support to youth with a view to facilitating their transition from school to work.

5. Le Forem - Belgium

In Belgium the Walloon Office for Vocational Training and Employment, known as Le Forem, employs broad social media facilities to communicate with young people and disseminate various dimensions of its outreach strategy. It uses extensively Facebook, YouTube and Twitter to promote PES services and advertise job and training opportunities.

6. BiZ-Mobil - Germany

The German PES has introduced mobile career information centres to reach out to individuals who are not yet PES clients. The BiZ Mobil runs field campaigns visiting schools, training institutions and job fairs. In addition to distributing information folders and brochures on all issues related to the application, training, learning and work, it organizes film and slide shows. It provides access to special applications through the internet allowing the identification of individual interests and predisposition and the creation of potential career profiles.

Source: EC (2015) “PES practices for the outreach and activation of NEETs”; OECD (2016) “Society at a glance”.

To broaden the job opportunities for youth candidates, the Employment Centre should also increase the number of offers in the job bank. Analysis of the job bank and the posts available at the central web portal of PES shows that as of November 2017 there were no more than 6 500 vacancies. Moreover, most job offers are targeted at medium-skilled or high-skilled professionals with secondary or even tertiary education, which shows that PES does not provide many opportunities for the most disadvantaged low-skilled youth. As a way of upgrading the vacancy bank, private employers should be encouraged to place more job advertisements on the platform. To this effect, employers could be granted free access to the database of youth candidates in exchange for advertising vacancies on PES platform.

Strengthening the training component of youth ALMPs

Recent studies on ALMPs in Latin America have pointed to the positive impact of dual training-with-apprenticeship programmes on the probability for youth participants to find a job in the formal sector (Escudero et. al, 2017; OECD, CAF and ECLAC, 2016). These studies also show that much of the success of on-the-job training depends upon the capacity to engage the employer sector. Countries typically have a range of employment and/or wage subsidies in place to reinforce such an engagement and Peru is no exception. As part of Jóvenos Productivos, for example, the Peruvian business sector already participates in the design and implementation of training in close collaboration with the authorised training centres and the government.

Nevertheless, the evidence available is that firms in Peru make little use of the apprenticeship incentives provided to them. The factors behind this little traction include the obligation to use the tax benefits exclusively for employees listed in the electronic payroll system of the company. Since many youth candidates to become training apprentices do not have a job contract, they do not appear in the electronic payroll and therefore are not eligible for the tax benefit. In addition, the tax authority can apply considerable discretion when it decides which parts of the training expenses are eligible for the tax benefits. Given that this discretionary power is not precisely defined, firms prefer to err on the side of caution, which results in an underinvestment in training for fear of being declared ineligible for the benefit.

Public work programmes to boost incomes and work experience

Besides providing income support, public works programmes have been argued to bring a number of other benefits (Subbarao et al., 2013). Because they provide individuals with work experience, they help maintain and/or improve skills and therefore promote labour force participation and more permanent pathways out of poverty than simple cash transfer programmes. They can be particularly helpful for groups at the margins of the labour market, such as women, youth and the low-skilled, and help them raise their bargaining power by guaranteeing work at the minimum wage rate and, therefore, enforcing a minimum wage rate on all casual work. Public works also tend to rely on self-selection as the primary targeting mechanism with the central parameter being the wage at which the work is rewarded. The wage for such programmes has to be set at a level low enough to attract only those in need of temporary work, but high enough to provide an adequate source of income.

In addition, public work programmes have a number of secondary benefits, including the creation of public goods and the promotion of social cohesion. In some countries, they have also been used for environmental (e.g. generation of water storage, afforestation, and compost generation) and social purposes (running child care centres, nursing homes, school kitchens, etc. see Lieuw-Kie-Song et al., 2010).

More recently, some programmes have also been moving beyond the mere provision of temporary work by providing training opportunities to prepare participants for possible longer-term employment, self-employment, or further education and training. The basic motivation behind this is to provide individuals with a more permanent pathway out of workfare and poverty. The type of training provided can include vocational training, basic skills training (literacy and numeracy) as well as entrepreneurship training. These considerations suggest that Trabaja Perù could benefit from a strong training component.

The supportive role of certification

In order to strengthen the labour market prospects of youth, on-the-job training experiences should be certified by an independent certification body. Recent work by Cahuc, Carcillo and Minea (2018) sheds new light on the effects of individual pathways with various forms of labour market experience for youth who have dropped out of high school. Building on information collected through a field randomized experiment (i.e. after sending fictitious résumés to real job postings), their results indicate that the likelihood of receiving a call-back from employers sharply improves when youth get a certification of their skills. Other pathways in the labour market without skills certification seem unable to improve the employment outlook of unskilled youth. Notably subsidized or non-subsidized work experience, either in the market or non-market sector, even for a few years does not significantly improve the chances to be contacted by employers compared with an unemployment spell of the same duration. These results suggest that accruing work experience, even in the market sector, is not always sufficient to get more frequently call-backs. Employment support measures, such as temporary jobs in the non-market sector or hiring subsidies in the market sector, should be conditional on getting a certification of skills at the end of the employment period, at least for previously unskilled youth.

Nurturing a monitoring culture

Developing an impact evaluation culture is also critical. One key challenge in Peru relates to the limited access to data and information on the outcomes of ALMPs; for example, information from randomized experiments about these outcomes are scarce in Peru. To fill this gap, the Ministry of Labour and Employment Promotion could build on the experience of the Ministry of Education, which launched MineduLAB in 2016. Working in partnership with regional arm of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL LAC) and Innovation for Poverty Action Peru, MineduLAB is actively engaged in evaluating the effectiveness of innovative education policies to improve children’s learning in the country. To this effect, it makes extensive recourse to randomized controlled trial field experiments. A similar approach could be used to assess the performance of ALMPs.

Youth guarantees to re-engage NEETs in employment, education or training

Many OECD countries have recently committed themselves – through so-called “youth guarantees” – to providing all young NEETs with a suitable employment and/or educational offer, with a prominent example being the European Union’s Youth Guarantee scheme, introduced in 2013. It is meant to ensure that all young people under the age of 25 – whether registered with employment services or not – receive a good-quality offer of employment, continued education, an apprenticeship or a traineeship within four months of leaving formal education or becoming unemployed. Such initiatives can be a valuable tool to help improve young jobseekers’ employment prospects. Their success relies, however, on effective outreach to inactive and disconnected youth. The quality of options offered, moreover, is important, and solutions must be tailored to young jobseekers’ individual needs.

3.3. Strengthening income support to unemployed youth, conditional on active job search in the formal sector

Welfare systems based on the provision of a balanced mix between social insurance and social assistance are a key to reconcile flexibility of labour markets with income security. Social safety nets act as an insurance mechanism to help the jobless overcoming liquidity constraints and protect them from falling into poverty upon loss of labour income (OECD, 2016a). They are of utmost importance for young people on the way to self-sufficiency.

Recent analysis by the International Labour Office points the accent on the extension of social security coverage, the institutionalization of the contributory unemployment insurance, (complemented by social and labour integration policies) and the improvement of the coordination between contributory and non-contributory policies, which are important priorities for Peru to tackle (Casalí et. al, 2015). In line with this diagnosis, several initiatives have been undertaken by the Peruvian government in recent years to broaden the coverage and strengthen the generosity of social protection. In the process, the related public spending reached over USD 2.5 billion in 2015 (1.4% of country’s GDP).

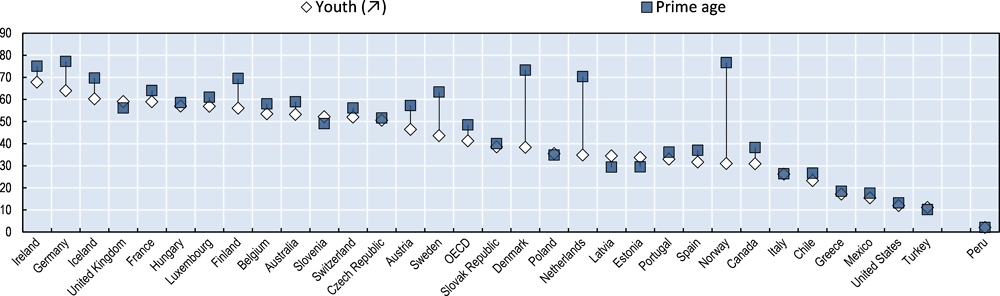

Figure 3.6 displays the share of the working age population (youth aged 15-29, in the comparison with prime age workers 30-64) that would be poor if they did not receive social protection payments, such as unemployment benefits, social assistance, family allowances or disability benefits. OECD countries on average protect around 40% of the youth and 50% of prime age individuals (30-64) from falling below national poverty lines, thanks to social transfers. In Peru, the proportion of people effectively protected from (relative) poverty through provisions from the social protection system equals around 2% for both age groups.

3.3.1. Unemployment insurance is not fully developed

Adequate support during unemployment spells provides an essential replacement of lost income to smooth consumption. It can also help enhancing job quality by lessening the constraint on the unemployed to accept first job offers to cover subsistence needs. In emerging economies, where informality is widespread, unemployment insurance may additionally bring important macroeconomic gains through fostering labour force participation and formalization.

As a counterpart to the abolition of the severance pay in the occurrence of justified dismissals, Peru established a system of Unemployment Insurance Savings Accounts (UISAs) in the early 1990s, at a time when other Latin American countries were undertaking similar initiatives (Brazil, 1989, and Colombia, 1990). Up until then there used to be a tenure bonus, which became the Compensation for the Length of Services (Compensación por Tiempo de Servicios, henceforth CTS, introduced in Chapter 2). This individual saving scheme is financed by the employer with a deposit equivalent to half of the employee’s monthly salary payable every six months (May and December). The scheme is intended for private employees not covered by other special regimes. Each worker can choose the financial institution where to deposit the fund. Employers and employees can through a private arrangement agree that the employer is responsible for the deposit.

Important amendments introduced since 1996 have considerably diluted the capacity of the CTS to protect the employees against the risk of unemployment. In particular, workers have been allowed to withdraw all or part of their CTS deposits in case of an emergency other than unemployment (for instance to cancel loans and debts incurred with financial institutions), or at cases to help “stimulate domestic demand”. They were also allowed to use the funds as loan guarantees against the purchase or construction of a property, a renovations or the acquisition of land. According to the latest law adjustments (Emergency Decree 001-2014), workers can withdraw 100% of their contributions above four monthly gross salaries accumulated in the CTS. This means that an equivalent of only four gross monthly salaries must be kept in the individual’s CTS deposit to prepare for the eventuality of unemployment.

For youth jobseekers, the limited capacity of the Peruvian unemployment benefit system to work as a safety net is compounded by two additional factors. First, more precarious employment conditions for youth workers than adult workers mean that their contribution records are relatively more volatile, which prevents them from accumulating enough savings in their CTS account. Second, young people are disproportionately hired by small and microenterprises, which are exempt from the payment of the CTS (cfr., Chapter 2, Box 2.2). The combinations between these factors means that merely one in ten youth employees have their CTS accounts contributed parallel to the payment of their wage bill.

In principle, severance pay remains an option in the event of unjustified dismissal. As an alternative to the constitutionally backed right of reinstatement, dismissed workers can choose a termination payment equal to 1.5 monthly salary per each full year of service (if employed under a permanent contract) and 1.5 monthly salary per each full month of remaining service up to a maximum of an annual salary (if the work agreement was fixed-term). In practice, however, OECD calculations based on ENAHO figures suggest that in 2015, the severance indemnity was paid to less than 1% of dismissed youth.

3.3.2. Lack of social assistance targeted at unemployed people

Within the Strategy for National Social Development and Inclusive Growth, since 2011 MIDIS has carried out an articulated programme to strengthen income security for all. This strategy relies on a life-cycle approach, embracing five strategic axes dedicated to populations at different stage of live: nutrition and early childhood development targeted at children aged 0-3; integral development of childhood and adolescence for the 6-17 years old; economic inclusion for working age population 18-64; and protection of the older adults (65+).

Although the strategy is not specifically intended to provide assistance to the unemployed, it includes schemes that indirectly support youth jobseekers. For example, unemployed youth can take advantage of Juntos, a conditional cash transfer programme, when living in a poor household where a child under 19 attends school. Or, they can indirectly benefit Pensión 65, a social pension programme, when part of a household with older relatives entitled to the social pension (Box 3.5). In 2016 just about 7% of unemployed youth were living in households benefiting from social assistance -- receiving on average PEN 115 per month (equal to USD 35 or EUR 30). The great majority of them received support from Juntos. Pensión 65 covered only around 1% of households with an unemployed youth – although many of them were receiving the Juntos allocation, at the same time.

In 2016 one in eight youth in Peru were receiving directly or benefiting indirectly from Juntos. While this places Peru well compared to the OECD average (equal to 8%), the coverage of Juntos remains limited relative to the needs of the country. Unlike other regional partners - Mexico and Brazil, for example - Peru lags behind in providing assistance to the poorest quintile of the population, as recommended by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The coverage of Juntos slightly exceeds half that of Mexico’s Prospera (Figure 3.7). Moreover, there are large disparities in numbers of youth beneficiaries between the regions and urban-rural areas. While around 30% of rural unemployed youth live in households receiving the transfer, less than 5% of urban unemployed youth benefit from it (Figure 3.8).

Juntos, a conditional cash transfer programme, is the main social assistance tool available in Peru to target vulnerable populations. Since its creation in 2005, it seeks to alleviate poverty and extreme poverty through a multi-dimensional approach that tackles simultaneously nutrition, health, and education issues. The programme focuses on districts with high levels of poverty (40%, or more) and indigenous communities regardless of their placement. The target units are poor and extremely poor households with children up to 19 years old or with pregnant women. The programme’s aim is to break intergenerational poverty by putting children from poor households in a poverty alleviation trajectory (i.e. not just immediate alleviation, but creating the conditions for sustainably escaping poverty). In 2016, participating households received a cash transfer of PEN 200 every two months, regardless to the size of the family. Conditions for receiving the transfers are that families take care of monitoring health and ensuring school attendance of children, while pregnant women have the obligation to undergo regular check-ups.

Randomized evaluations of Juntos have shown that the programme has positive welfare effects in terms of income and consumption and has significantly contributed to poverty reduction. It also contributes to increase the utilization of health services by women and children (Perova and Vakis, 2009), and is seen to positively affect nutritional outcomes (Sanchez, Melendez, and Behrman, 2016, Sánchez and Jaramillo, 2012, and Andersen et al., 2015). Moreover, studies find significant effects on women empowerment, specifically on economic household decision-making, self-esteem and perceptions of life (Alcazar et.al, 2016).

Programa Nacional de Asistencia Solidaria – Pensión 65 is a social pension programme targeted to individuals aged 65 and over, living in conditions of extreme poverty and not eligible to receive a pension from the contributory system. Beneficiaries are entitled to a monthly transfer of 250 soles. The goal of this non-contributory pension plan is to alleviate poverty and reduce vulnerability of older populations. It is part of the Peruvian social inclusion model, whose long-term objective is to ensure that individuals from vulnerable groups can access a full range of integrated social services during their old age.

3.3.3. Policy options for devising an income support scheme for unemployed youth that encourages job search

Improving the unemployment benefit system

As a short-term solution, Peru could consider strengthening the requirements for CTS withdrawals in the event of unemployment. For example, the threshold above which employees are allowed to withdraw 100% of the CTS funds could be raised to six monthly gross salaries from the current level of four monthly salaries. This means that the equivalent of at least six gross monthly salaries would have to be kept in the individual’s CTS account to prepare for the eventuality of unemployment, corresponding to an increase of 50% from today’s threshold. In addition, access to the core part of the CTS account could be made at least partly contingent upon the jobseeker’s active job search in the formal sector.

A more ambitious approach would involve re-designing the current unemployment insurance system possibly combining a system of individual saving accounts with a common solidarity fund and including elements that encourage job search. This two-tier approach could draw inspiration from the model set up in Chile. Under the first pillar, individual savings accounts for each worker would be financed by contributions from the worker and the employer in the case of open ended contracts, and only by the employer in the case of workers with atypical contracts. The second pillar would rely on the creation of a solidarity fund (Fondo de Cesantía Solidario in the Chilean UISA scheme), financed by the employers and from the government budget. Unemployed workers would only receive payments from the solidarity fund if their own savings are insufficient to cover their period of unemployment.2 Also, the number of payments from the solidarity fund would be limited – for example, payments can be withdrawn at most twice over a five-year period in the Chilean system.

On top of the inclusion of the solidarity fund, another salient characteristic that sets the Chilean model apart from other unemployment insurance systems in Latin America is the incorporation of a strong link to labour market activation (Sehnbruch and Carranza, 2015). For example, registration with PES is automatic under the Chilean UISA. This ensures that unemployed workers receiving insurance payments and made redundant for economic reasons benefit from preferential access to the vocational education and training programmes provided by the country’s national training and employment service. At the same time, insurance payments are contingent upon the worker’s acceptance of a place in the publicly provided vocational training programme. Similarly, the unemployed cannot decline without justification a job offer by PES that would have rewarded him an earning at least equal to 50% of the last earning.

A number of potential strengths of the Chilean UISA system could appeal Peru (Ferrer and Riddell, 2009; Huneeu, Leiva and Micco, 2012; Sehnbruch and Carranza, 2015):

-

First, the combination between individual savings accounts with pooled risk sharing provides for a more adequate insurance against unemployment risks than the blend of CTS and severance pay.

-

At the same time, the individual savings accounts help containing the risk of adverse selection typically stemming from the fact that only those workers likely to become unemployed contribute -- a situation that could lead to undermine the long term sustainability of the system. In fact, the prospect to defer the use of the deposits to after retirement, not only raises the attractiveness of the scheme to a much wider pool of contributors. It also generates an incentive to avoid falling in long-term unemployment since the individual has an interest to accumulate as much as possible funds to increase old-age income. Furthermore, the presence of strong mutual obligation requirements helps reducing concerns about moral hazard that characterise the traditional unemployment insurance systems.

-

Finally, the findings of new analysis suggest that affiliation may support job quality. These results point to a small difference between wages prior and after the unemployment spell for workers affiliated to the Chilean UISA. It also finds no difference in contract types (Nagler, 2016).

In thinking about the implementation of a system modelled along the Chilean UISA, some decisions would have to be taken and policy makers will face some key implementation challenges. One challenge relates to the existing high level of turnover induced by the extensive use of temporary contracts in a context of strong labour market duality. The other challenge stems from the extent of the administrative and budgetary efforts required to implement effectively strong mutual obligation requirements in an economic environment characterised by a sizeable informal sector, which implies that abuses may be difficult to monitor. These considerations suggest that initially it might be more prudent to keep replacement rates relatively low and benefits durations short. From a broader strategic perspective, they underscore the importance of following an integrated policy approach that takes into account the policies discussed in Chapters 2 and 3. The policy insights of Chapter 2 precisely aim to reduce labour market duality. The previous sections of Chapter 3 provide useful insights as to how to improve the effectiveness of activation.

Targeting social assistance at NEETs who actively search a job in the formal sector

The Peruvian government could also take steps to better gear the provisions of social assistance to the needs of jobless youth who, reflecting their very short, or even lacking, work histories, do not qualify for the unemployment benefits. Implementing a mean tested Jobseeker Allowance (henceforth JA) that provides financial support to unemployed persons not eligible for any kind of benefits, could represent a desirable option. A salient feature of a JA scheme is that, as a counterpart to the unemployment subsidy, candidates would be mandated to register with PES and to engage intensely in job search. Beneficiaries would not be in a position to reject suitable job offers.

Conceived in this way, the JA scheme is very similar to the non-contributory component of the Chilean UI system. However, qualification criteria are typically less restrictive since they do not require an earlier work history, implying that first-time job seekers can also apply for benefits. The scheme can thus be particularly appealing for attracting Peruvian NEETs into labour markets. Since the costs of implementing the JA on a universal scale can be significant, it could exclusively target the NEETs as a way of containing the expenses.

An alternative solution would involve subordinating access to existing social assistance transfers (i.e., Juntos) to the effort to actively search for a job. Obliging capable members of families receiving the subsidy to register with PES and to participate in activation could be a viable way to motivate youth to search for a job. Roughly 10% of Peruvian NEETs, i.e. 180 000 youth, live in households entitled to the Juntos transfer. At the same time, Peru could also use Juntos as a tool to reward achievements. For example, the Chilean programme Ingreso Ético Familiar (Ethical Family Income provides an extra support to beneficiaries who have integrated the formal sector after obtaining an educational degree (See Box 3.6 for details).

The programme Ingreso Ético Familiar, IEF; Ethical Family Income) was launched in 2013. This innovative antipoverty programme combines unconditional and conditional transfers. The programme is tailored to the extreme poor and vulnerable populations, seeking to develop skills that place the families on stable, long-term production and employment pathways. By 2015, it was serving 137 000 families, or around 549 000 individuals, with an annual budget of 232 billion Chilean pesos (USD 360.25 million), representing 0.16% of Chile's gross domestic product (GDP).

The programme supports families through a package of subsidies organized into three pillars: Dignity, Duties and Achievements. The Dignity pillar is unconditional and the subsidies are paid for a maximum period of 24 months to families whose income falls below the extreme poverty line. The second pillar, Duties, targets families with children up to 18 years old and is conditioned on fulfilling co-responsibilities related to school attendance and routine check-ups of the health of children. The pillar Achievement provides an extra support to families that attain outstanding results. These can include a School Achievement Bonus, provided to students under age 24 who demonstrate outstanding academic performance; a Female Employment Subsidy, aimed at encouraging the engagement of women in formal work; a Secondary School Graduation Bonus provided to students who earn a high school diploma at an institution accredited by the Ministry of Education; and a Formal Employment Subsidy to promote formal work among those participating in the IEF’s social and occupational support programme. It is a one-time subsidy given once the individual has made four consecutive health, pension, or unemployment insurance contributions.

Since the programme is still relatively new, the impact has yet to be fully studied. However, reflecting its innovative design, the project has the potential to generate important effects on beneficiaries’ income school achievements, employability and formalization.

Source: IADB Conditional Cash Transfers Toolkit : https://www.iadb.org/en/toolkit/conditional-cash-transfer-programs

Using ICT to leverage the development of social protection

ICT can provide a useful support to the development of social protection transfers. For example, it can facilitate the identification of individuals registered with PES and at the same time are beneficiaries of welfare programmes. This could help conditioning the transfer of unemployment benefits on active participation in PES services.

Recourse to systems of unique identification number and unified contribution collections has been marked across LAC countries. The establishment of Brazil’s database Cadasdro Unico dates back to 2001. It was built on the initial data collection efforts for Bolsa Família (the flagship Brazilian cash transfer programme) and now covers more than 20 million households and is used to coordinate several different social safety programmes. Chile’s Integrated System for Social Information (SIIS) is an ICT platform conceived to link many databases belonging to public entities through the internet. SIIS is often cited as one of the most advanced example of integrated data management across the social protection sector and beyond (Barca and Chirchir, 2014). In Peru, the civil identification system, Reniec, allows social security services to reach out to remote populations in the Andean and Amazonian areas and to indigenous communities (Reuben and Carbonari, 2017). The benefits of these practices to the population are visible in terms of reduced fragmentation of services and reduced administrative costs and errors. At the same time, the administrations gain in terms of improved data exchanges across institutions and reduced abuses.

Overall, these advantages mean that ICT can play an important role to help strengthening institutional coordination of the system of social protection. Yet, the digital divide remains strong in Peru, where 34% of NEETs still declared non-use of the internet in 2016. Increasing access to an affordable digital infrastructure, especially in remote rural areas, is a key to strengthening regional development and improving the integration of disadvantaged youth into labour markets. An intermediate solution that could ease the lack of access to the internet, while at the same time attracting youth to PES, could be through promoting the wider dissemination of toll-free kiosks with PC terminals in the regional offices of Employment Centre.

3.4. Reducing the skill mismatch

Skill mismatch hampers the smooth integration in the formal labour market of youth job seekers, which in turn has an impact on their job satisfaction, motivation and self-esteem. At the macroeconomic level, it can induce substantial productivity losses due to misallocation of workers to jobs, with over-skilling and over-qualification -- which happens when the individual is hired in a job that requires lower skills proficiency or a lower education level than the one acquired -- being particularly costly.

From a dynamic perspective, the demand for skills by the business sector is in continuous evolution, driven by economic development. Adjustment costs may be significant and are more likely to be borne by the least skilled and the most disadvantaged youth. Combined with rapid technological progress, demographic change and increased globalisation, these trends may lead to exacerbate income inequalities. Moreover, the new forms of work that are emerging raise serious concerns about the quality of jobs that are created.

What is important in this context is to build resilient and adaptable labour markets that allow workers to manage the transition with the least possible disruption, while maximising the potential benefits offered.

3.4.1. High prevalence of over-qualification and field-of-study mismatch

Skill mismatch may arise along two dimensions, a vertical dimension that relates to qualification, or a horizontal dimension, related to field-of-study. Qualification mismatch arises when workers have an educational attainment that is higher or lower than that required by their occupation. If their education level is higher than the requisite, workers are over-qualified; if it is lower, they are under-qualified. Field-of-study mismatch arises, instead, when workers are employed in a different field than what they have specialized in.

To improve the understanding about the interplay between skill supply and skill demand, the OECD has developed a new methodology that allows gauging country-specific Skills for Jobs Indicators (OECD, 2017). The qualification mismatch is obtained by comparing individuals’ qualification levels with the qualification requirements specific to a given occupation. Such requirements are approximated by the most common (modal) educational level of workers employed in a given occupation. On the other hand, the field-of-study mismatch is evaluated by comparing the actually pursued occupation against the discipline of education. The reminder of this section applies the new methodology to the case of Peru, with Box 3.7 providing a description of the indicators used.

The OECD Skills for Jobs Indicators include, among others, two indicators of skill mismatch: qualification mismatch and field-of-study mismatch.

The qualification mismatch index estimates the share of workers in each occupation that are under- or over-qualified to perform a certain job. This is obtained by computing the modal (i.e. most common) educational attainment level for each occupation (as classified by the 2-digit ISCO codes) and using this as a benchmark to measure whether individual workers’ qualifications match the typical education requirement of the occupation. Over-qualification appears when the highest level of education achieved by an individual worker in an occupation is above the modal level for all workers in that occupation, while under-qualification appears when individual’s education falls below the modal level.

The field-of-study mismatch index is calculated following Montt’s (2015) methodology, which assumes that certain fields of study (ISCED) prepare workers to participate in certain occupations (ISCO). As a result, individuals are considered well matched if they work in the occupation that is considered to be a good fit for their field of study and mismatched otherwise.

Source: OECD, 2017.

Analysis of the two indicators suggests that skill mismatches are pervasive in Peru, both in terms of misalignment of education levels with respect to jobs that are in demand and field-of-study. Nearly 38% of Peruvians aged 15-64 are employed in jobs that require different qualification level and almost 50% (of those aged 15-34) are mismatched by the field of study (Figure 3.9).3

Whereas the overall degree of qualification misalignment in Peru is in line with the OECD average, the nature differs. Unlike in OECD countries, where under-qualification tends to be more prevalent, in Peru roughly three-quarters of qualification mismatch is due to over-qualification. About 28% Peruvians work in jobs that require lower educational levels than they hold, while around 8% perform jobs without sufficient qualifications. Over-qualification seems to be a feature common to different LAC countries. For example, Mexico and Chile, whose over-qualification rates equal 38% and 30% respectively, score worse than Peru, while Argentina does slightly better (27%).

Field-of-study mismatch fuels additional skill imbalances in Peru. With virtually half of graduates working in a different profession than the one for which they pursued education, Peru lags far behind the OECD countries. This means that obtaining a tertiary level education, or specialized secondary education, does not necessarily help smoothing the transition to the labour market since the field of study is not well aligned with labour market needs. It is important to underline that the field-of-study mismatch is not necessarily a reflection of the qualification mismatch. 56% of cases of field-of-study mismatch are associated with over-qualifications. The remaining 44% of cases are individuals employed in jobs at the adequate level, though in a field that does not correspond to the profession learned.

Important heterogeneities in terms of skill imbalances exist among different age groups, occupations and educational profiles of job candidates. Young workers are more prone to qualification mismatches than workers of prime age. Roughly 35% of all employed Peruvian youth aged 15-29 do jobs that require a lower education and around 10% are underqualified. The field-of-study mismatch for the cohort aged 15-29, equal to 51%, is also somewhat higher than for the entire group of reference (15-34).

Moreover, the mismatch is more common in less demanding occupations, which absorb the surplus of (over-)educated individuals. Like in the OECD countries, in professions that strictly require formal education, such as medical doctors or lawyers, the mismatches are low. Conversely, in typical medium- and low-skilled occupations such as vendors, construction workers or workers in mining, manufacturing and elementary occupations, up to 60% of the employed hold higher qualifications than necessary for the job.

3.4.2. Reasons behind Peru’s skill mismatch

In principle, a persistent skill mismatch may be the outcome of two acting forces. Either, on the supply side of the labour market, workers do not adjust fast enough to changes in skills demand by acquiring the right skills or, on the demand side, the business sector is unable to keep up with changes in skills levels by creating jobs that use the skills available (Rathelot and Van Rens, 2017). In practice, the explanation of the skill mismatch reflects a combination of both acting forces.

Higher school enrolment and educational attainments but low quality education

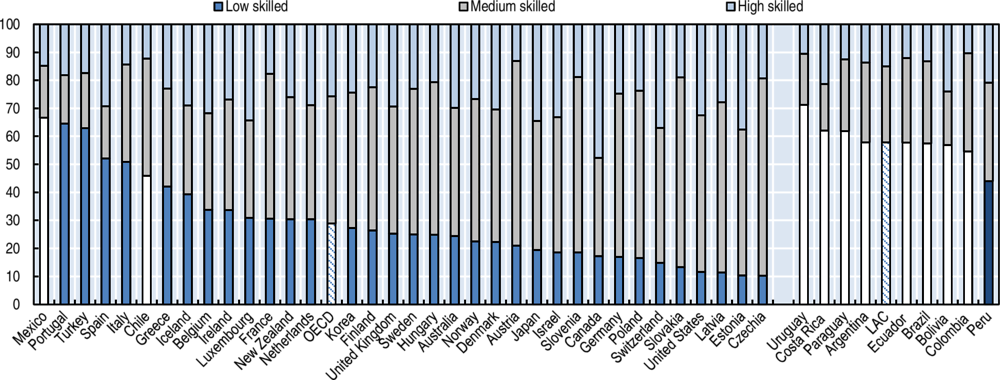

Over the past decade Peru made remarkable progress in terms of school enrolment and educational attainments. UNESCO data show that the country is well on the way to creating a highly educated labour force. With 21% of population aged 25 and over holding a tertiary degree, and 35% holding an upper-secondary degree, Peru outranks many countries from both LAC and OECD regions in terms of human capital endowments (Figure 3.10). At the same time, youth attain systematically higher educational levels than their peers did not long ago. With primary schooling being virtually universal today, 80% of adolescents continue education at a secondary level and nearly 35% of youth aged 18-21 enrol in post-secondary education. Consequently, more youth than ever before are graduating from tertiary level educational institutions.

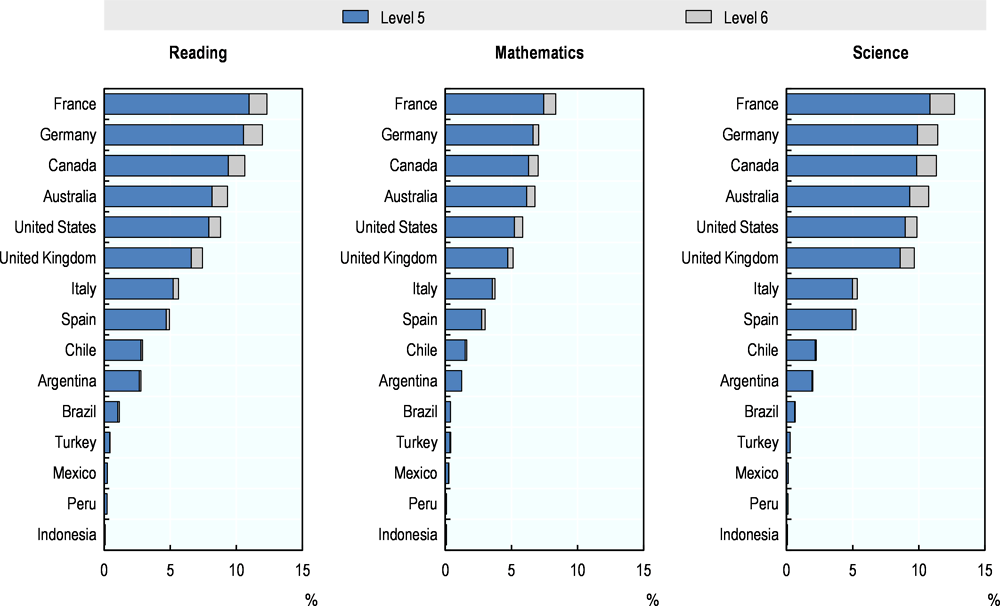

Despite the improvement in enrolment and schooling attainments, there is still scope to enhance the quality of the educational system in Peru. The OECD Programme for International Students Assessment shows that Peruvian high school students not only lag far behind their counterparts from the best performing countries, but also score systematically worse than students from other LAC countries participating in the survey. The share of Peruvian pupils who in the latest edition of the test achieved one of the top two proficiency levels (level 5 or 6) in any of the three core competences, i.e. reading, mathematics or science, is negligible (Figure 3.11). Roughly one in two Peruvian students scored below level 2 in all three subjects, which means that almost half of the 15-year olds were unable to solve even simple tasks requiring straightforward reasoning. The small share of top performers combined with excessively high proportion of low achievers places Peru at the bottom of the international comparison, suggesting that the schooling system does not provide students with the basic foundation and cognitive skills that are commonly taught in schools.

Gaps in proficiency accrued earlier in the lifecycle are likely to be transmitted to higher stages of education and to take a toll on working careers in adulthood. Without addressing issues undermining quality of both elementary and secondary level education, successful decent tertiary level education becomes more difficult. Yet, deficiencies in educational background of students are only one of the many challenges facing tertiary education in Peru. As referred to in Chapter 1 (Box 1.1), one of the country’s biggest problems lies in the relatively uncontrolled increase of privately owned post-secondary educational institutions -- itself rooted in the approval of Law N° 882, better known as “Law to promote investment in Education” of 1996. There is a growing concern that the significant expansion of tertiary education that has been achieved has not been matched by a parallel increase in service quality (Espinoza and Urzua, 2015). Many of the privately owned institutions provide skills of little relevance and low marketability, which undermines the value of tertiary education and likely affects the returns to education.

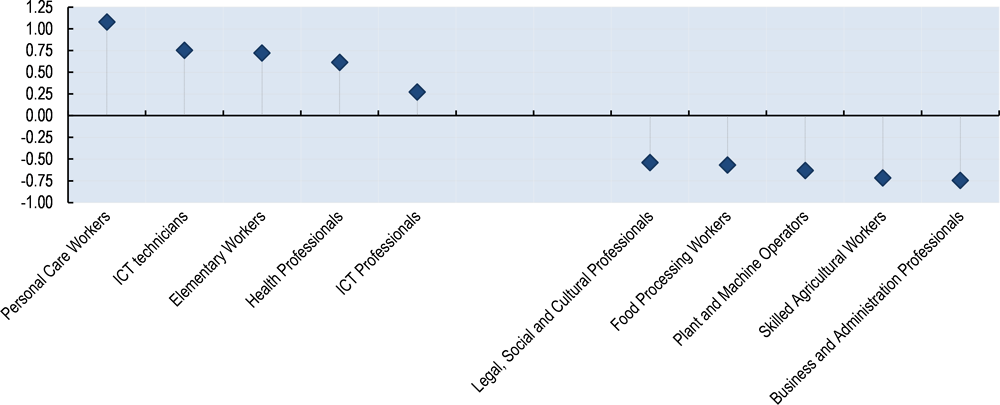

According to the OECD Skills Strategy Diagnostic Report the reasons behind this situation are manifold (OECD, 2016a). Firstly, the growing number of private schools has led to relax admission requirements, in turn lowering the average skill levels of students. Secondly, the limited availability of university professors and lecturers has accentuated the reliance on part-time teaching agreements, with staff originating from external educational institutions. This might have led to a deterioration of both the quality of teaching provided and courses content (OECD, 2016a; Castro and Yamada, 2013). Furthermore, financial incentives driving the choice of private university curricula imply that the programmes offered are highly concentrated in a few fields of study, mostly revolving around Business and Finance (Figure 3.12).