Chapter 19. New Zealand

Support to agriculture

Since its reform of agricultural policies in the mid-1980s, production and trade distorting policies have almost disappeared in New Zealand, and the level of support to farmers has been the lowest among OECD countries, accounting for less than 1% of farm receipts. Practically all prices are aligned with world market prices. Exceptions are fresh poultry and table eggs (as well as some bee products) which cannot be imported to New Zealand due to the absence of Import Health Standards (required for risk products to be allowed for imports) for these products. Some support for on-farm services mainly related to animal health, and for disaster relief, provide additional farm support to a small extent.

Agricultural policies in New Zealand predominantly focus on animal disease control, relief payments in the event of natural disasters, and the agricultural knowledge and information system. The government also provides support to large-scale off-farm investments in irrigation systems. Over the past decades, the share of agricultural land under irrigation was significantly expanded. Overall, for most of the past two decades, more than 70% of all support was through general services.

Main policy changes

Policies often respond to specific and acute problems. Key policy changes thus comprise a set of detailed measures, relating notably to disaster relief, biosecurity, and investments in the environmental sustainability performance of the land-use sector.

In 2018, several medium-scale adverse events have triggered government support for the Enhanced Task Force Green programmes and Rural Assistance Payments. These programmes provide funding for clean-up and recovery work, and relief to farmers in hardship, respectively.

In response to the 2017 discovery of the bacterial infection mycoplasma bovis, a biosecurity response was declared. Government and sector leaders agreed to work towards eradication of the disease, 68% of the cost of which is to be borne by public funding.

With the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a tenth New Zealand Free Trade Agreement entered into force, covering nearly one-fourth of New Zealand’s goods and services trade and almost a fourth of its agro-food exports.

Assessment and recommendations

-

New Zealand’s agricultural sector remains open and focused towards foreign markets and trade, as underlined by the country’s low level of producer support. Its export orientation is supported by New Zealand’s engagement in numerous free trade agreements, the tenth of which being the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which has just entered into force.

-

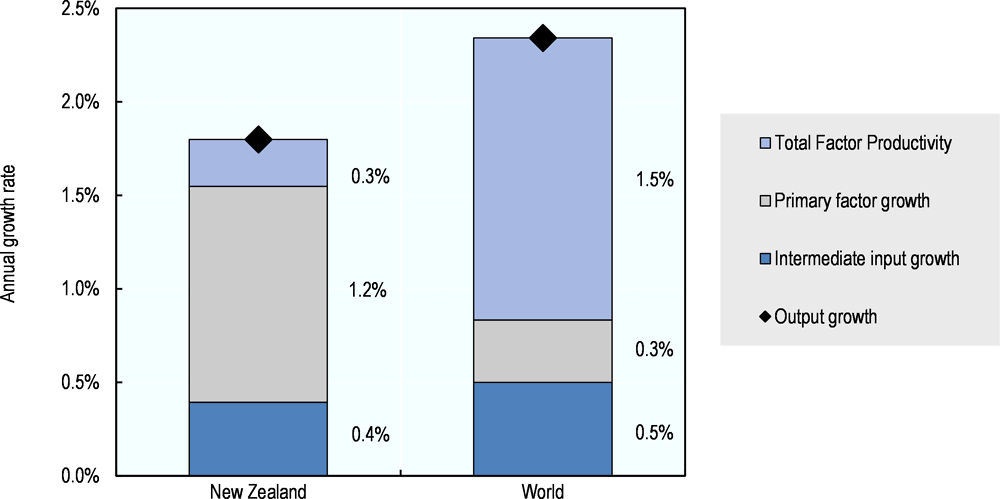

New Zealand’s policy mix rightly focusses on key general services and, notably, its agricultural knowledge and innovation system. Investments in these areas should help improve agricultural productivity growth which, in recent years, has been comparatively low. Overall, public expenditures for general services are often complemented by mandatory funding from private investors which can help to ensure effective allocation of general services investments.

-

New Zealand’s Import Health Standards (IHS), a key tool to ensure the country’s biosecurity vis-à-vis imported products, present an exception to this open-market principle. While required for all risk products to be importable, no IHS are in place for some livestock products, including eggs, fresh chicken meat and honey, and these products therefore cannot be imported into New Zealand. While representing only a small share of New Zealand’s agricultural output, this deprives consumers of lower prices and larger choices. The development of relevant IHS would hence benefit consumers while ensuring required biosecurity standards.

-

Kiwifruit exports to markets other than Australia continue to be regulated by requiring authorisation by Kiwifruit New Zealand for third-country exports by groups other than Zespri. New Zealand should aim to change these restrictions which burden the participation in kiwifruit exports by other firms wishing to do so and hence reduce competition and efficiency in this trade activity.

-

The enforcement of the Overseas Investment Amendment Act 2018 adds further restrictions on foreign investment in New Zealand’s in agricultural land. While its impact will depend on the actual implementation of the Act, attention should be given to not discourage valuable foreign investment that could enhance productivity and competitiveness of the farm sector.

-

While several of New Zealand’s agricultural sectors, including meat and dairy processors, nitrogen fertiliser manufacturers and imports, and live animal exporters, have reporting obligations under the New Zealand Emissions Trading System, agricultural greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are neither constrained nor taxed. The agriculture sector accounts for half the country’s GHG emissions. Ambitions to reduce such emissions, in line with New Zealand’s commitment to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, are pursued mainly through its support to a number of research activities at both national and international levels.

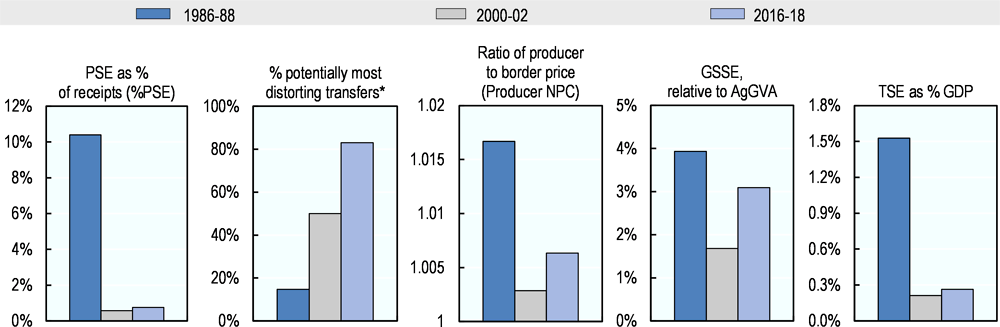

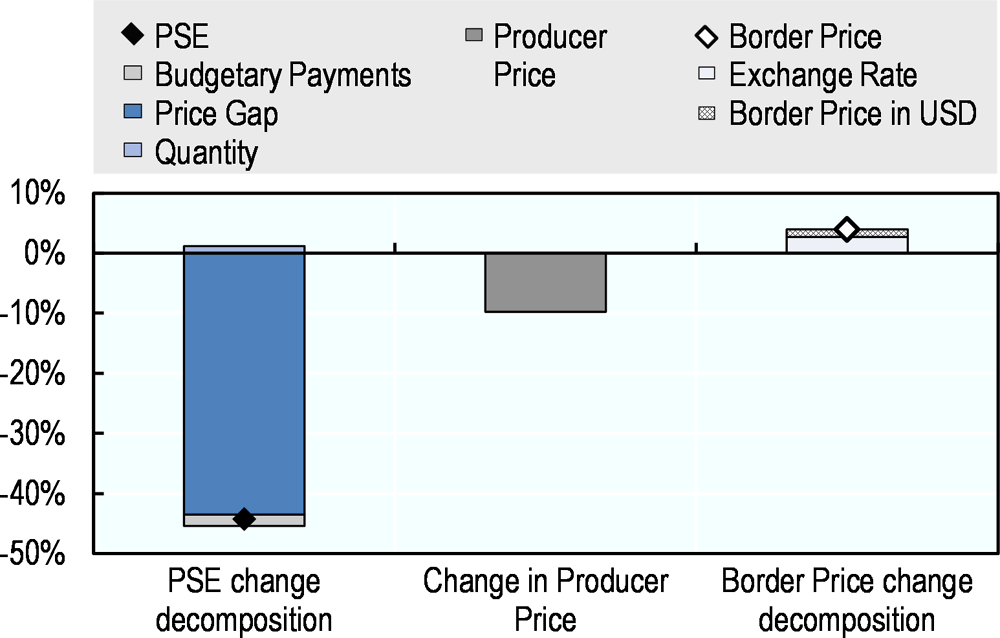

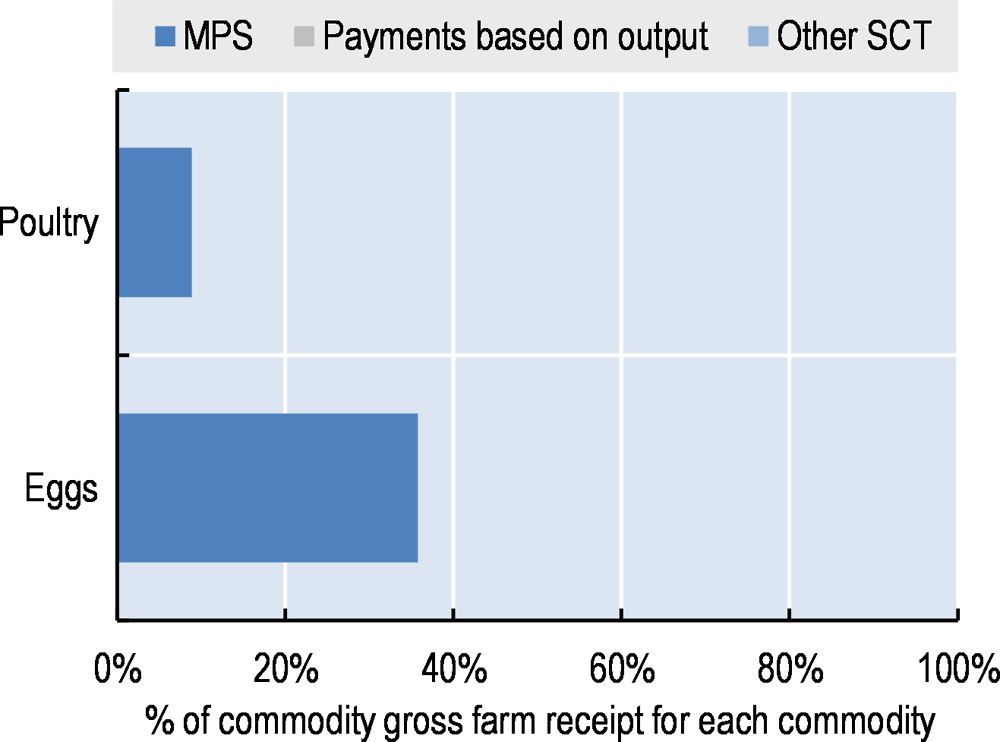

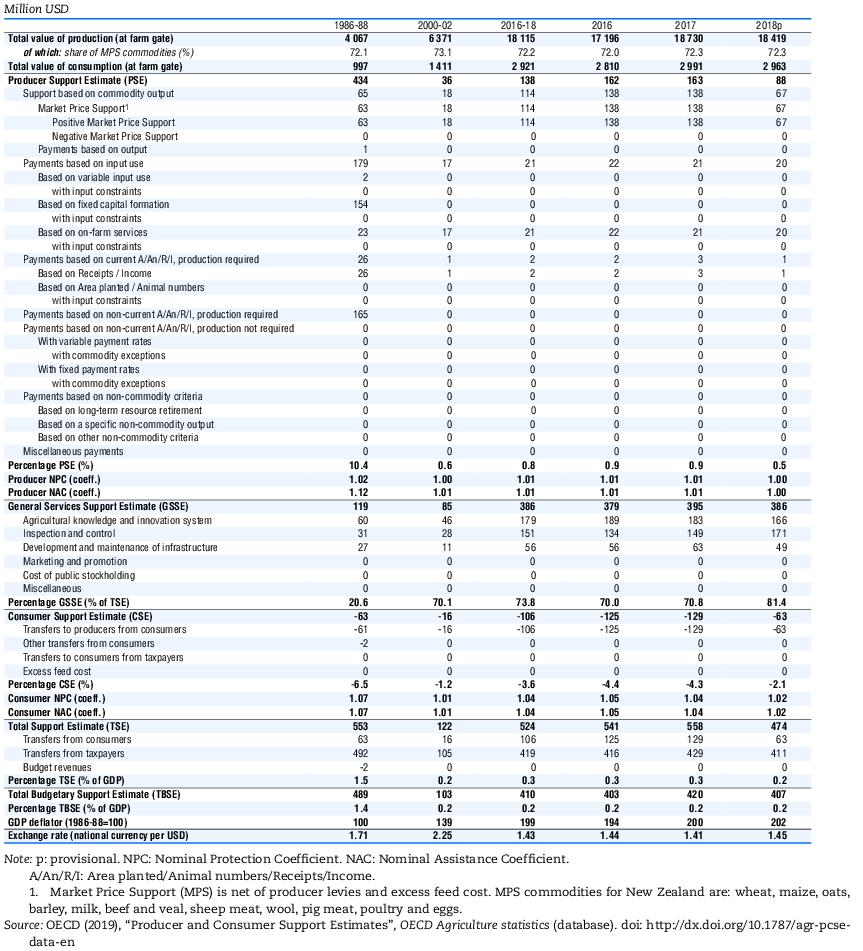

Support to producers (%PSE). After the reforms in the mid-1980s and the corresponding sharp decline of the support to producers, the %PSE has remained at levels below 2% of gross farm receipts; during 2016-18, it averaged 0.8%. Most of this (very low) support to producers is provided through some market price support (MPS), one of the potentially most distorting forms of support and arising from SPS-related import restrictions (Figure 19.1). This creates some Single Commodity Transfers (SCT) for poultry meat and eggs, corresponding to 9% and 36% of commodity-specific gross farm receipts, respectively (Figure 19.3). Other than those, domestic prices are aligned with world prices, resulting in an average price ratio between domestic and reference levels (NPC) of less than 1.01. Overall, total support to agriculture (TSE) represents less than 0.3% of GDP. Most of the support is provided for general services, focusing mainly on the knowledge and information system and on biosecurity-related measures (Figure 19.1). In 2018, the low PSE further declined as price gaps in poultry and egg markets narrowed, both due to higher world prices and lower domestic ones (Figure 19.2).

Contextual information

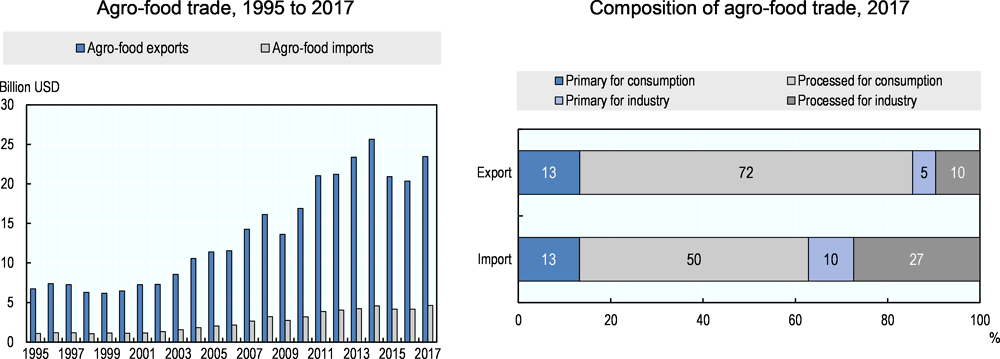

New Zealand is a relatively small and thinly populated economy with a per capita GDP slightly above the OECD average, but well above the average of all countries covered by the report. Its market openness is related to its high dependency on international trade. Agriculture’s importance in the total economy is higher than in most other countries covered in this report: the sector accounts for about 6% in both GDP and employment. Moreover, agro-food products account for almost two-thirds of the country’s total exports. With little arable land, grass-fed livestock products represent the backbone of the agricultural sector, making New Zealand the world’s largest exporter of dairy products and sheep meat. Fruit and horticultural products also contribute significantly to the country’s agriculture and food exports.

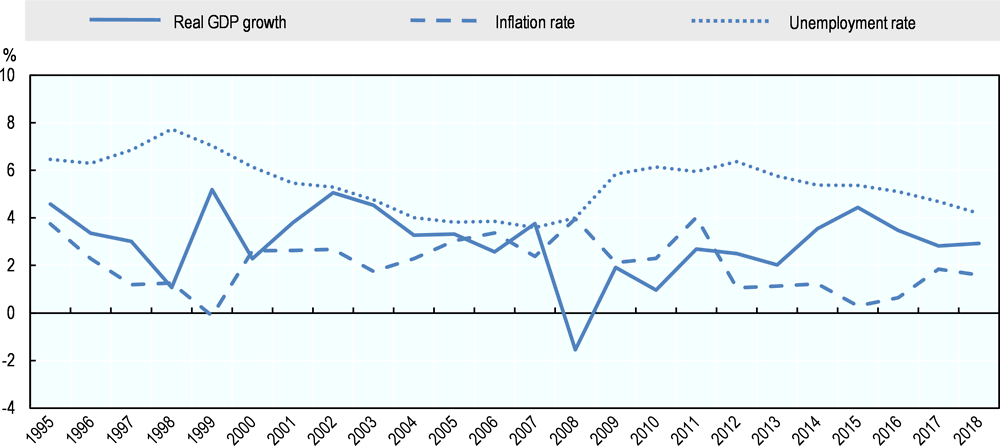

New Zealand has a stable economy having featured robust growth and a relatively low inflation rate for most of the past decade. It shows consistent and growing net exports of agricultural products, which after some drops in 2015 and 2016 due to, among others, lower dairy prices, have picked up again in 2017. Most of New Zealand’s agro-food trade, particularly of its exports, is processed food for final consumption. On the import side, intermediary products represent more than a third of the trade basket.

New Zealand’s average growth in total factor productivity (TFP) is estimated at less than 0.3% per year over the 2006-15 period, the lowest value across countries covered by this report and well below the growth rate during the 1990s.

New Zealand’s agricultural sector is the country’s prime consumer of freshwater and has strongly expanded its irrigated land as a response to climate related uncertainties. Nonetheless, its overall level of water stress is limited. Agriculture is also the main source of GHG emissions, due to the high importance of grass-fed livestock production. For the same reason, the country’s nutrient surpluses are well above the respective OECD averages.

Description of policy developments

Main policy instruments

New Zealand largely limits its agricultural support to expenditures on general services, such as agricultural research and bio-security controls for pests and diseases. A significant share of the costs of regulatory and operational functions, including for border control, is charged to beneficiaries (primary sector businesses) or those who create risks (primary sector businesses and exporters).

Practically all of New Zealand’s agricultural production and trade is free from economic regulations. Since the phasing out of restrictions for dairy exports to specific tariff quota markets by the end of 2010, such export rights are now allocated to dairy companies on the proportion of milk-solids collected. Export regulations continue to exist for kiwifruit: the New Zealand company Zespri has the default right to export kiwifruit to all markets other than Australia, although not the exclusive one. Other traders can export kiwifruit to markets other than Australia in collaboration with Zespri, subject to approval by Kiwifruit New Zealand, the relevant regulatory body. Kiwifruit exporters to Australia are required to hold an export licence under the New Zealand Horticulture Export Authority Act 1987 which provides for multiple exporters to that market.

The 2017 amendments to the Kiwifruit Export Regulations 1999 allow Zespri shareholders to consider setting rules around maximum shareholding and eligibility for dividend payments; clarify the activities Zespri can undertake as a matter of core business; and enhance the independence and transparency of Kiwifruit New Zealand.

The Dairy Industry Restructuring Act 2001 (DIRA) was established to promote the efficient operation of the New Zealand dairy industry. In particular, it aims at ensuring that farmers can freely enter and exit the Fonterra Co-operative, and that other processors can obtain raw milk necessary for them to compete in dairy markets. A review of the DIRA, launched in May 2018, includes the open entry and exit obligations, the farm gate milk price settings, contestability for farmers’ milk, the risks and costs for the sector, and the incentives or disincentives for dairy to move to sustainable, higher-value production and processing.

The Food Act 2014, in force since 1 March 2016 with a three-year transition period, aligns the domestic food system with the risk-based approach of other New Zealand food statutes that have more of an export focus. New Zealand’s food system aligns with international trends in food regulation that have shifted to using a risk-based approach that focuses on the outcome of providing safe and suitable food, rather than using prescriptive regulation.

Import Health Standards (IHS) are documents issued under the Biosecurity Act 1993. They state the requirements that must be met before risk goods can be imported into New Zealand. Risk goods can only be imported if an IHS is in place for the product, and if all relevant IHS measures have been met. For some products (table eggs, uncooked chicken meat, and honey) no IHS is in place. These products therefore cannot be imported, leading to some market price support as their domestic prices are above the world market level.

“Industry good” activities1 (such as research and development, forming and developing marketing strategies, and providing technical advice) previously undertaken by statutory marketing boards are now managed through producer levy-funded industry organisations under the Commodity Levies Act 1990. Under this legislation, levies can only be imposed if they are supported by producers, and producers themselves decide how levies are spent. With a very limited number of exceptions, levy funds may not be spent on commercial or trading activities. The levying organisations must seek a new mandate to collect levies every six years through a referendum of levy payers.

The New Zealand government continues to engage with industry and stakeholders to build biosecurity readiness and response capability. The Government Industry Agreement for Biosecurity Readiness and Response (GIA) has established an integrated approach to preparing for and effectively responding to biosecurity risks, through partnerships between the government and primary industry sector groups. Signatories share decision making, costs and responsibility in preparing for and responding to biosecurity incursions. In 2018, Horticulture NZ, DairyNZ, and Beef+Lamb New Zealand signed the GIA deed, bringing to 20 the number of industry groups that have joined with the Ministry for Primary Industries under GIA. Participation in GIA is voluntary.

OVERSEER is a nutrient management tool used for setting and managing nutrients within environmental limits. It helps farmers and growers improve their productivity, reduce nutrient leaching into waterways, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The intellectual property of OVERSEER is jointly owned by the Ministry for Primary Industries, AgResearch Limited, and the Fertiliser Association of New Zealand. The tool is increasingly being used by regional councils that are implementing the National Policy Statement on Freshwater Management. Additional funding of NZD 5 million (USD 3.5 million) between 2019 and 2022 aims at quicker adoption of environmentally friendly farm practices, the inclusion of a wider range of land types and farming systems, and a more user-friendly interface.

Pastoral Genomics is a New Zealand consortium for forage improvement through biotechnology. It is funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), DairyNZ, Beef+Lamb New Zealand, Grasslands Innovation, NZ Agriseeds, DEEResearch, AgResearch, and Dairy Australia. The consortium aims to generate better forage cultivars that will increase productivity, profitability and environmental sustainability of New Zealand’s pastoral farming systems. The New Zealand Government is investing NZD 7.3 million (USD 5.5 million)2 between 2015 and 2020 through the MBIE partnerships scheme; this funding will be matched by industry funding. The partnership has specifically chosen genomic selection as it is a non-regulated technology enabling more rapid uptake by the partner seed companies.

Sustainable Food and Fibre Futures (SFF Futures) is the consolidation of two previous investment programmes: the Sustainable Farming Fund and the Primary Growth Partnership, which consequently both closed to new applications. With an increased emphasis on sustainability, SFF Futures funds innovative projects that will create more value and improved sustainability for the food and fibre industries. SFF Futures has a budget of NZD 40 million (USD 28 million) per year and provides a single gateway for farmers, growers, harvesters and industry to apply for investment in a range of projects that deliver economic, environmental and social benefits. Projects can range from small, one-off initiatives to long-running multi-million dollar partnerships. Community projects will require co-investment from the partner organisation of at least 20 percent of costs. Profit-driven projects will require co-investment of at least 60% of costs. Applications for SFF Futures funding opened in October 2018.

In ratifying the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, New Zealand has committed itself to a Nationally Determined Contribution of reducing emissions on an economy-wide basis to 30% below 2005 levels over the period 2021-30 (-11% below 1990 levels by 2030). The commitment includes all sectors and all gases, with no specific targets or commitments set for the agricultural sector. New Zealand is on track to achieve its current target under the UNFCCC (-5% below 1990 levels by 2020).

The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS), New Zealand's primary policy response to climate change, imposes reporting obligations on agriculture, including meat processors, dairy processors, nitrogen fertiliser manufacturers and importers, and live animal exporters, although some exemptions apply. The NZ ETS also imposes an emissions cost on the transport fuels, electricity production, synthetic gases, waste and industrial processes sectors.

The New Zealand Government continues to research and develop mitigation technologies to reduce agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. It does so through the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC), the Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium (PGgRc), and in co-ordination with the 52 member countries of the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases (GRA).

The NZAGRC, funded by the Ministry for Primary Industries, brings together nine organisations that conduct research to reduce New Zealand’s agricultural greenhouse gas emissions.3 Research is focused on finding practical ways of reducing on-farm methane and nitrous oxide emissions while improving productivity and sequestering soil carbon.

The PGgRc is a partnership, funded 50:50 by Government and industry,4 that aims to provide livestock farmers with the information and means to mitigate their greenhouse gas emissions. The PGgRc mainly focuses on research to reduce methane emissions in ruminant animals.

The GRA, of which New Zealand hosts the Secretariat, was established in 2009. Its member countries collaborate on the research, development and extension of technologies and practices that can deliver more climate-resilient food systems without growing greenhouse gas emissions. New Zealand also hosts the GRA Special Representative and leads the GRA’s Livestock Research Group. In 2017, a new scholarship programme was established to build global expertise on climate change, agriculture, and food security, with the purpose of boosting New Zealand’s contribution to agricultural greenhouse gas research. The scholarship programme is a joint initiative of the GRA and the climate change programme of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). New Zealand funding is to support around 40 recipients to be hosted in research centres of the CGIAR and GRA member countries and partners within three years.

The Afforestation Grant Scheme is a NZD 19.5 million (USD 13.5 million) programme to establish 15 000 hectares of new forest plantations between 2015 and 2020, providing funds to farmers and land owners. New planting aims at increased erosion control, improved water quality, reduced environmental impacts following flooding, and reduced GHG emissions. The 2018 funding round, worth around NZD 6.1 million (USD 4.2 million), saw 6 123 hectares contracted to plant new forests in winter 2019. Future afforestation applications are to be funded through the One Billion Trees programme (see below).

The Ministry for Primary Industries’ General Export Requirements for Bee Products strengthen traceability across the supply chain and provide a scientific definition of mānuka honey that can be used to identify and authenticate mānuka honey from New Zealand. Based on a combination of five attributes (comprising four chemicals and one DNA marker from mānuka pollen), the requirements aim to give consumers and trading partners confidence that all mānuka honey exported is true to label.

With the overall goal of adding value to exports, the Ministry for Primary Industries’ programme, Māori Agribusiness: Pathway to Increased Productivity (MAPIP), focuses on Māori primary sector assets under collective ownership. The MAPIP framework supports Māori primary sector asset owners who seek to sustainably increase the productivity of their primary sector assets, including land, agriculture, horticulture, forestry, and seafood.

On climate change adaptation, the New Zealand Government has established a Technical Working Group to look at how to build resilience to the effects of climate change, while ensuring sustainable economic growth. Members of the Group represent various economic sectors, including agriculture.

New Zealand currently has ten Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) in force, which account for approximately two-thirds of the value of New Zealand’s total exports and 70% of its agro-food exports. As a trade dependent economy, and being geographically distant from export markets, FTAs are one way through which the New Zealand government aims at supporting improved productivity, value-added, and export earnings in the primary sector. Two additional agreements are concluded but not yet in force – the New Zealand-Gulf Cooperation Council FTA (involving Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates), and the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA).5

Domestic policy developments in 2018-19

Farmers and growers faced three medium-scale adverse events in 2018 – flooding/storm damage in Taranaki & Tasman, flooding in Gisborne, and drought in both the North and South Islands (noting this began in 2017 for some regions). Across these events the Rural Support Trusts claimed NZD 195 000 (USD 135 000) in costs from the New Zealand Government. Rural Support Trusts are a nationwide network that directly assists rural communities and individuals affected by adverse events. The support provided is primarily aimed at, but not limited to, primary producers and can extend beyond physical damages.

The New Zealand Government made NZD 750 000 (USD 520 000) available for Enhanced Task Force Green (ETFG) programmes as part of flood recovery measures in Tasman and Gisborne. ETFG programmes allow hiring workers and acquiring relevant equipment to help with clean-up and recovery after emergency events having caused significant damage.

Rural Assistance Payments (RAPs) were made available and utilised as a result of the drought. RAPs are available to farmers in real hardship. RAPs cover essential living costs for those farmers whose income is severely impacted by a medium-scale (or greater) adverse event and they have no other means of supporting the family.

In July 2017, the bacterial infection Mycoplasma bovis was found in cattle in South Canterbury. This was the first detection of Mycoplasma bovis in New Zealand and the Ministry for Primary Industries declared a biosecurity response. Mycoplasma bovis presents no food safety or human health risks, but can cause serious health problems in cattle, which do not respond to treatment, and hence adversely affects both productivity and animal welfare. Affected farmers can apply for compensation from the Ministry for Primary Industries, under the Biosecurity Act 1993, where they have suffered a verifiable loss as a result of damage to, or destruction of, property (including stock and equipment destroyed in an attempt to limit the spread of the bacteria) as a result of the exercising of powers under the Act, or as a result of restrictions imposed on the movement or disposal of goods.

In May 2018, Government and agricultural sector leaders agreed to work towards eradication of Mycoplasma bovis from New Zealand to protect the national herd and long-term productivity of the farming sector. A Strategic Science Advisory Group is expected to provide international expertise on a range of science matters, to identify any potentially useful research and emerging technologies, and to provide assurances that the eradication research efforts continue to be fit for purpose. The government projects the full cost of phased eradication over 10 years at NZD 886 million (USD 613 million). Of this, NZD 16 million (USD 11 million) is loss of production borne by farmers, and NZD 870 million (USD 602 million) is the cost of the biosecurity response (including compensation to farmers). Government will meet 68% of this cost, with the two industry groups DairyNZ and Beef+Lamb New Zealand to meet the remaining 32%. An additional NZD 30 million (USD 21 million) over two years in funding for scientific research will support the eradication programme.

Changes to the Animal Welfare Act 1999, in May 2015, gave the Ministry for Primary Industries the ability to make animal welfare regulations. The regulatory programme is being developed and implemented in three tranches. As an initial set of regulations, the Young Calf and the Export of Livestock for Slaughter regulations were released in July 2016. A further set of regulations came into effect on 1 October 2018. These regulations related to stock transport, farm husbandry, companion and working animals, pigs, layer hens, rodeos, surgical or painful procedures, inspection of traps, and crustaceans. The final substantive package of regulations focuses on significant surgical procedures and is due to be completed in early 2020.

Amendments to the Misuse of Drugs (Industrial Hemp) Regulations 2006 and the Food Regulations 2015 came into effect in November 2018, allowing hulled, non-viable and qualifying low THC hemp seed to be treated as any other edible seed. Growing, possession and trade of whole seeds still require a licence from the Ministry of Health.

The Extension Service Model is a pilot initiative to support farmers in improving their environmental performance and value creation. It builds on existing programmes to ensure farmers use information on environmental sustainability and value creation as part of their farm planning. The Extension Service Model will be rolled out over four years from 1 July 2018 with funding of NZD 3 million (USD 2.1 million) from SFF Futures.

Both the Ministry for Primary Industry’s Irrigation Acceleration Fund (IAF) and the Crown Irrigation Investments Limited (CIIL) are currently winding down. With the exception of three schemes under the CIIL, no further projects will be funded. These three schemes, to be funded for their construction phases due to their advanced states, include the completion of Central Plains Water Stage 2 (Canterbury plains); construction of the Kurow-Duntroon scheme (Kurow, South Canterbury); and construction of the Waimea Community dam (Nelson/Tasman). Funding support for community-based water management and storage projects or smaller-scale, locally run and environmentally sustainable water storage projects may be considered against the criteria for investment within the Provincial Growth Fund, a newly established economy-wide fund.

The One Billion Trees Fund, launched in November 2018, is a step towards achieving the goal of planting at least one billion trees by 2028, and towards lifting annual planting rates (including re-planting following harvest and new planting) from about 60 million trees in 2018 to about 100 million per year within 2-3 years. The Fund provides NZD 118 million (USD 82 million) for grants to landowners and organisations to plant trees for a variety of purposes, including erosion control, carbon sequestration, timber and biodiversity. It also provides NZD 120 million (USD 83 million) for partnership projects to reduce barriers to tree planting through innovation, research and sector development initiatives.

The Overseas Investment Amendment Act 2018 came into force in October 2018, and brought residential and lifestyle land under the definition of “sensitive” land. The key change was replacing the large farm directive with a broader, rural land directive which applies to all rural land larger than five hectares, other than forestry. As a result, most New Zealand land is now “sensitive”, meaning that the consent of the Overseas Investment Office is required for transactions of such land involving “overseas persons” as defined under the Act. The Amendment Act also places conditions on overseas investors – they must now demonstrate how their investment will benefit the country.

Trade policy developments in 2018-19

With the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP),6 a tenth New Zealand Free Trade Agreement entered into force on 30 December 2018. It covers nearly one-fourth of New Zealand’s good and services trade and almost a fourth of its exports of agro-food products.

New Zealand continues negotiations in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).7 Negotiations between New Zealand and the countries of the Pacific Alliance8 started in October 2017, while those for a New Zealand-European Union FTA were launched in September 2018. Negotiations to upgrade the New Zealand-China FTA are ongoing, while those on the New Zealand-Singapore Closer Economic Partnership (CEP) were substantially concluded in 2018.

References

[2] NZIER (2007), “Productivity, profitability and industry good activities”, a report to Dairy Insight, New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, https://nzier.org.nz/publication/productivity-profitability-and-industry-good-activities.

[1] OECD (2019), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Notes

← 1. Activities “beneficial to the industry, but whose benefits cannot be captured by those who fund or provide the activity”, or “long-term investments in the industry made with the expectation of accelerating delivery of better technology and products for the industry” (NZIER, 2007[2]).

← 2. All values in this policy description use the 2018 exchange rate for monetary conversion.

← 3. The seven member Crown research institutes and universities are: AgResearch, Landcare Research, Lincoln University, Massey University, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Plant Food Research and Scion. The two other organisations involved are DairyNZ and the Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium.

← 4. Industry partners are DairyNZ, Beef+Lamb New Zealand, DEEResearch and Fertiliser Research.

← 5. Other ACTA signatories include Australia, Canada, the European Union and 22 of its Member States, Korea, Japan, Mexico, Morocco, Singapore, and the United States.

← 6. Other CPTPP countries include Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Singapore, and Viet Nam.

← 7. Other RCEP participants include the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet Nam), Australia, the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”), India, Japan, and South Korea.

← 8. Pacific Alliance countries include Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru.