Chapter 4. Enhancing trust in the digital economy

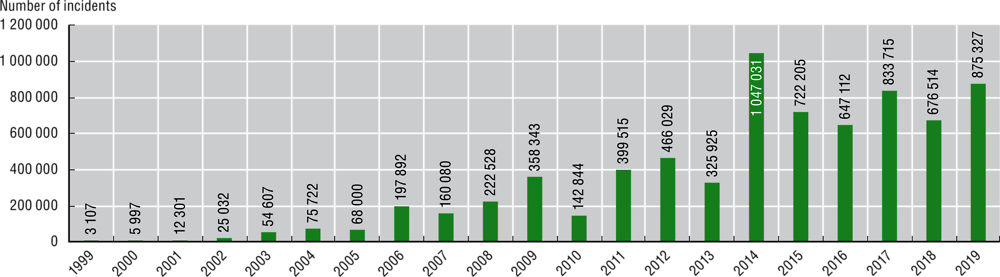

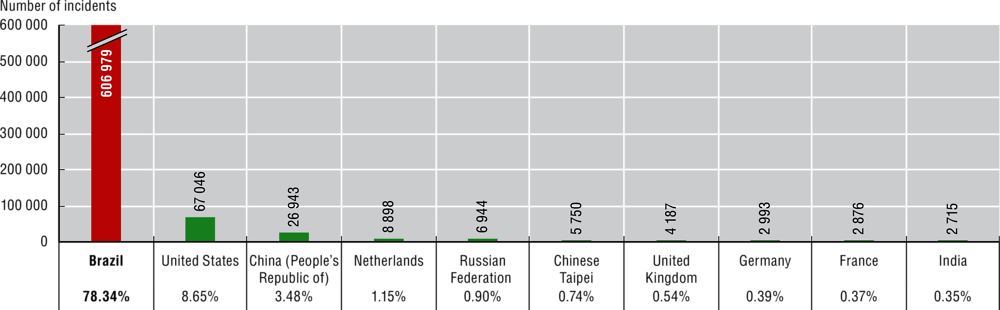

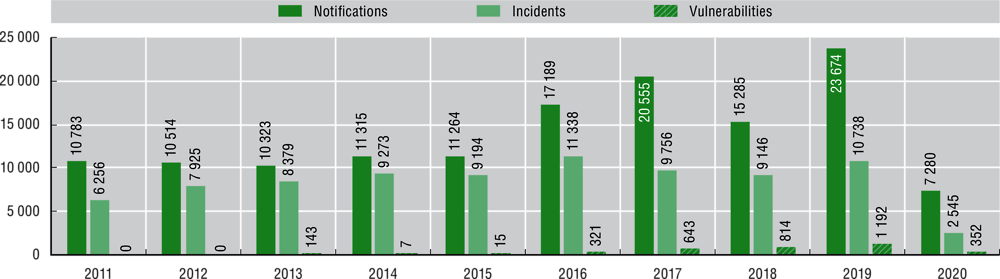

Brazil is increasingly being targeted by digital security attacks. CERT.br, the private sector Brazilian National Computer Emergency Response Team (Centro de Estudos, Resposta e Tratamento de Incidentes de Segurança no Brasil) maintained by the executive branch of the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee (Núcleo de Informação e Coordenação, NIC.br), received over 875 000 incident notifications in 2019, 78% of which originated from Brazil (Figures 4.1 and 4.2). The Brazilian Government Computer Security Incident Response Team (Centro de Tratamento e Resposta a Incidentes Cibernéticos de Governo, CTIR) also reports an increasing number of incidents (Figure 4.3). A brief analysis of data from other sources confirms this situation. In 2018, EUROPOL found that Brazil is both a leading target and source of attacks in Latin America, and further noted that 54% of digital security attacks reported in Brazil originate from within the country (EUROPOL, 2018) According to the LexisNexis Threatmetrix (2019), Brazil is the sixth country from which attacks originate globally (in volume).

The 2018 Norton Survey showed that 89 million Brazilians have been a victim of cybercrime, with 70.4 million in the last year alone (Norton, 2018). A Ponemon Institute’s 2017 survey of 36 Brazilian companies in 12 sectors showed that they suffered an average of USD 1.1 million in losses for each digital security attack (Ponemon, 2017). The Marsh JLT13 Cyber Review 2019 survey, conducted with 200 medium and large Brazilian companies, found that 55% of these companies are totally dependent on the use of technology in their activities and that 35% may suffer severe downtime in the event of a technology-related problem (Insurancecorp, 2019).

However, 44% of companies surveyed did not have contingency plans or budgets to combat incidents and did not foresee, in their budgets, a response to a possible crisis.Eighty per cent of respondents estimated that a digital security incident would have significant operational impact across the enterprise (Insurancecorp, 2019). According to a survey of ICT practices in the health sector by Cetic.br (2018), only 23% of public and private health establishments had a document defining an information security policy in 2018.

To address this issue, Brazil is in the process of developing a broad digital security framework, starting with the adoption of its first National Cybersecurity Strategy.

This section provides an overarching description of digital security policies in Brazil and discusses their strengths and limitations from the perspective of the 2015 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Security Risk Management for Economic and Social Prosperity (hereafter “Security Risk Recommendation”) (OECD, 2015) and the 2019 Recommendation of the Council on Digital Security of Critical Activities (OECD, 2019b). Unless specified otherwise, “digital security” refers to the management of economic and social risks resulting from breaches of availability, integrity and confidentiality of hardware, software, networks and data. This chapter does not cover policies directly related to criminal law enforcement (i.e. cybercrime), national defence or national security.

The emergence of digital security policy in Brazil

Digital security is not a new policy area in Brazil. Since 2000, digital security policy has been evolving along three main phases.

2000-12: The first steps of digital security policy in Brazil

This period was characterised by the establishment of the fundamental building blocks focusing on digital security in the public administration (Box 4.1). In 2000, the government established an information security policy for the federal public administration and created and Information Security Management Committee (Comitê Gestor da Segurança da Informação, CGSI) tasked with advising the Executive Secretariat of the National Defence Council about its implementation.1 The Brazilian Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) was created in 2001 (ICP-Brasil). The Government Computer Emergency Response Team (CITR Gov) was established in 2004. As of 2006, the Institutional Security Cabinet of the Presidency of the Republic (Gabinete de Segurança Institucional/Presidência da República, GSI/PR) was designated as the primary agency for digital security matters and, over the years, adopted 3 general instructions and 22 supplementary standards (as of 2019). The Federal Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União, TCU) monitored their implementation by the federal public administration through surveys followed by recommendations. The 2010 GSI/PR Green Paper on Cybersecurity in Brazil (GSI/PR, 2010), which included recommendations for the establishment of a national cybersecurity policy, can be viewed as the first attempt to approach digital security policy from a holistic and strategic perspective.

2000: Establishment of an information security policy for the public administration and creation of the Information Security Management Committee (CGSI), co-ordinated by the Institutional Security Cabinet of the Presidency of the Republic (GSI/PR).

2001: Creation of the Brazilian PKI (ICP-Brasil).1

2003: Creation of the Internet Steering Committee in Brazil (CGI.br).

2004: Creation of the Government Computer Network Incident Handling Team (CTIR.Gov).

2005: First Government Security Conference.

2006: Creation of the Department of Information and Communications Security (DSIC) within the GSI/PR; creation of a partnership led by the GSI/PR to facilitate the co-ordination of various public sector bodies, including public companies (e.g. Petrobras, Bank of Brazil, etc.), and adoption of a budget to facilitate information security training in the public administration.

2008: First survey of digital security in the public administration and recommendations by the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU). Adoption of the National Defence Strategy, which establishes the “cybersector” as one of the three strategic sectors considered essential for national defence.

2008-18: Publication by the GSI of 3 general instructions and 22 supplementary standards for digital security in the public administration, covering various topics such as risk management methodology, business continuity management, use of cryptography, biometrics, cloud computing technologies and procurement of secure software.

2009: Establishment of a “Cyber Security Technical Group” to propose guidelines and strategies for cybersecurity.

2010: Second TCU survey. Publication of the GSI/PR Green Paper on Cybersecurity in Brazil.

2011: Law on Access to Information, which establishes a principle of transparency of information within the public administration (entering into force in 2012).

2012: TCU publishes recommendations.

← 1. https://www.iti.gov.br/icp-brasil/icp-brasil-18-anos.

Source: GSI (2015), Estratégia de Segurança da Informação e Comunicações e de Segurança Cibernética da Administração Pública Federal 2015-2018, http://dsic.planalto.gov.br/legislacao/4_Estrategia_de_SIC.pdf/view.

2012-17: Increased attention to and focus on national security aspects

As of 2012, key events created the conditions for increasing the country’s operational digital security capacity while emphasising the national security dimension of digital security and raising awareness about privacy and civil liberties related to the Internet.

Between 2012 and 2016, the government significantly expanded its operational digital security capacity to protect several mega-events hosted in Brazil, such as the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20 in 2012), World Youth Day (2013), the football Confederations Cup (2013) and the World Cup (2014), and the Olympics and Paralympics (2016). The Ministry of Defence played an important operational role, including by establishing a Cyber Monitoring Centre (Demetrio, 2012), and co-operating with several agencies as well as public and private incident response teams to successfully manage the situation (Hurel and Cruz Lobato, 2018).

In 2013, revelations of foreign espionage activities affecting Brazil led to the creation of a Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry on Espionage (CPI da Espionagem), which underlined weaknesses in the country’s cybersecurity from a national security perspective. The committee’s final report recommended the development of a National Cybersecurity Strategy, the adoption of measures to co-ordinate public and private actions in this area, and the creation of a cybersecurity agency within the federal public administration to address the issue in an overarching and more effective manner.

During the same period, a considerable amount of public attention was dedicated to privacy and civil liberties issues related to the Internet, in particular through the public consultations for and adoption of the Internet Civil Legal Framework (Marco Civil da Internet), establishing principles, guarantees, rights and duties for the use of the Internet in Brazil (April 2014).2

However, in 2014, the results of an audit carried out by the TCU emphasised a relatively low level of implementation of existing digital security requirements by the federal public administration. According to the TCU, most of the federal public administration was not aware of its exposure to IT risks, the likelihood of their occurrence or their possible impact on the achievement of their objectives, and many public organisations, despite being aware of IT risks, did not keep them at acceptable levels or costs by treating them appropriately. The TCU stressed the low level of maturity with respect to the risk management process in the public administration. The TCU underlined that this situation increased the likelihood of IT not delivering results to business in the agreed time, cost and level of quality, consequently affecting the achievement of the business objectives of the entities. For example, only 25% of audited organisations had established guidelines for the management of IT risks, and only 8% were fully aligned with existing requirements. Only 13 out of 355 audited organisations had formally defined their acceptable levels of IT security risk (i.e. risk appetite).3

In this context, the GSI/PR developed the Strategy for Information and Communications Security and Cybersecurity in the Federal Public Administration, 2015-2018. After describing the background and context, this document set the strategic mission and vision, defined 7 strategic values, 11 guiding principles, and 10 strategic objectives with targets to be reached by 2018.

2018 to present: Digital security in the context of the digital transformation of Brazil

A new phase started in March 2018 with the publication of the Brazilian Digital Transformation Strategy (see Chapter 1), which includes a thematic axis focusing on “building trust and confidence in the digital environment”, with the objective of “making the Internet a safe and reliable environment that enables services and business transactions while respecting citizens’ rights”. This thematic axis addresses “defence and security in the digital environment” and the “protection of rights and privacy”.

According to the Digital Transformation Strategy, important progress in the area of “cyber defence” has been accomplished over the years, but Brazil still needs to improve its regulatory and institutional framework to match the challenge of digitalisation of the society and economy. The strategy claims that digital security should be regarded as a national priority and that a comprehensive “strategy for cybersecurity and defence” should be developed. The Digital Transformation Strategy points out that co-operation between the public and the private sectors is a crucial factor for the effectiveness of the actions envisaged in the future strategy and plans. It identifies several strategic actions, including the need to enhance digital security in the public administration; protect national critical infrastructure; raise the awareness of the population; enhance digital security skills in the public and private sectors; invest in research and development; develop metrics and information sharing models; as well as increase international co-operation.

In December 2018, the government published a decree establishing the National Information Security Policy (Política de Segurança da Informação, PNSI).4 Developed by the GSI/PR, this decree sets out 16 principles and 7 objectives. It establishes the legal basis for the development of a national information security strategy and of national plans detailing its implementation, such as planning, organisation, use of resources and attribution of responsibilities. The PNSI also includes measures related to roles and responsibilities with respect to information security within the public administration (see below).

In 2019, the GSI/PR started a process to draft the National Cybersecurity Strategy called for in the PNSI. To inform the development of the strategy, it organised a consultation process inspired by the one carried out for the digital strategy. The process included a 7-month, 31 meeting-long consultation of 40 experts from government agencies, businesses and academia gathered into 3 working groups. Based on this input, the GSI/PR developed a draft National Strategy for Cybernetic Security – E-Ciber, released in September 2019 for a 20-day public consultation through the participative government platform.5 Forty-one participants, including 31 individuals and 10 organisations, posted a total of 166 comments on the platform. The final strategy was adopted on 5 February 2020.6

The strategy’s vision is for Brazil “to become a country of excellence in cybersecurity”. The objectives of the strategy are to: make Brazil more prosperous and reliable in the digital environment; increase Brazilian resilience to digital security threats; and strengthen Brazil’s performance in cybersecurity in the international scene.

The strategy focuses on the following ten actions:

1. Strengthening digital security risk management governance in public and private sector organisations. This action includes holding fora, establishing minimum requirements in contracts with the public sector, promoting GSI/PR standards and norms, promoting international standards for security by design and default, nominating a chief information security officer, recommending digital security certification in accordance with international standards, etc.

2. Establishing a centralised governance model at the national level. A national digital security system will be created to promote co-ordination of actors beyond the federal administration, promote the joint analysis of the challenges faced in combating cybercrime, assist in the formulation of public policies, create a national cybersecurity council, create discussion groups in different sectors, etc.

3. Promoting a collaborative, participatory, reliable and secure environment involving the public sector, private sector and society. This action aims to encourage information sharing about incidents and vulnerabilities, carry out exercises, strengthen the national CERT (CTIR Gov), issue alerts and recommendations, encourage the use of cryptography, etc.

4. Raising the level of government protection, including by encouraging the use of secure communication devices, keeping information systems’ security up to date, recommending the use of backup mechanisms, including digital security requirements in privatisation processes, etc.

5. Raising the level of protection of national critical infrastructures by promoting interactions between sectoral regulatory agencies, encouraging the adoption of enhanced digital security policies by operators of critical infrastructures, encouraging their participation in exercises and the notification of incidents to CTIR Gov.

6. Enhancing the legal framework on digital security, including by reviewing the existing framework, modifying the penal code to include cybercrimes, creating incentives to reduce the cybersecurity skills shortage, preparing a draft law on cybersecurity.

7. Encouraging the design of innovative digital security solutions in order to align academic projects with the economic demand. For example, include digital security in research programmes, encourage the creation of research and development centres on digital security, stimulate the creation of digital security start-ups, encourage the adoption of global standards to facilitate international interoperability, establish minimum requirements for 5G technology.

8. Expanding Brazil’s international co-operation on digital security. This includes promoting discussions in international groups of which Brazil is a member, expanding relations in Latin America, promoting international events and exercises, expanding co-operation agreements, etc.

9. Expanding digital security partnerships between the public sector, the private sector, academia and society. Possible actions include partnerships to encourage private investments in digital security, meetings with leading digital security actors, etc.

10. Raising the level of digital security maturity in society. For example, carrying out public awareness initiatives; encouraging public and private sector organisations to carry out internal awareness-raising campaigns; integrating digital security in basic education; encouraging the creation of higher education courses; creating professional training courses; improving mechanisms for integration, collaboration and incentives between universities, institutes, research centres and the private sector, etc.

The strategy includes a diagnostic distinguishing between thematic and transformative axes:

Thematic axes: national cybersecurity governance, incident management and strategic protection, i.e. protection of the government and critical infrastructures identified in the National Policy for the Security of Critical Infrastructures (telecommunications, energy, transport, water, finance).

Transformative axis: normative dimension, research, development and innovation, international dimension and strategic partnerships, and education.

In July 2019, the government expressed its intention to adhere to the Convention on Cybercrime (Budapest Convention). In December 2019, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe invited Brazil to join the Convention (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2019).

Governance

According to the PNSI, the GSI/PR is the primary government body in charge of digital security in Brazil, a role it has been playing since 2000. According to the 2020 National Cybersecurity Strategy, the GSI/PR will continue to co-ordinate digital security at the national level.

The GSI/PR is at the centre of digital security governance

The GSI/PR’s responsibility covers three areas:

Information security standards and their implementation: establishing information security risk management standards for federal government agencies and entities; approving guidelines, strategies, norms and recommendations; and elaborating and implementing information security programmes aimed at raising awareness and training for the public administration and society.

Public policy: following the doctrinal and technological evolution at national and international levels; elaborating and publishing the National Information Security Strategy, in collaboration with the Inter-ministerial Committee for Digital Transformation (see below); supporting the elaboration of national plans related to the National Information Security Strategy; establishing criteria for evaluating the execution of the PNSI; and proposing the publication of the normative acts necessary for its execution.

Products: establishing minimum security requirements for the use of products incorporating information security features, which are binding for the federal administration; these requirements are not binding for the wider Brazilian market and only serve as a recommendation.

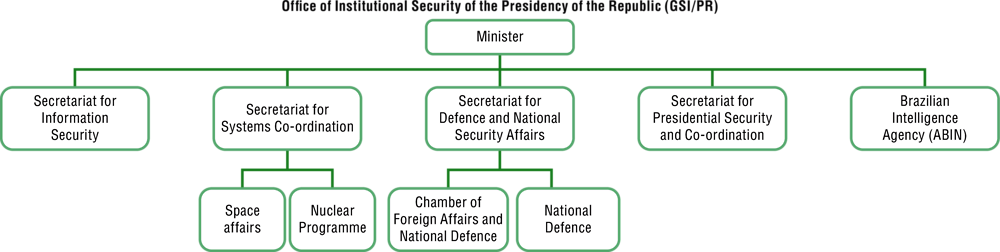

The GSI/PR is one of the organs of the Presidency of the Republic. It is led by a minister who reports directly to the President, as do all other Brazilian ministers. The Institutional Security Cabinet is responsible for analysing and monitoring issues related to potential risks of institutional stability; co-ordinating federal intelligence activities, and providing advice on military and security issues, in addition to other supporting functions for the President.7 Until 2019, digital security matters were addressed by the GSI/PR’s Department of Information and Communications Security (Departamento de Segurança da Informação e Comunicações, DSIC), within the Secretariat for Systems Coordination, which also addresses nuclear and space issues.

In 2019, the DSIC was elevated from a department to a secretariat. In contrast with a department, a secretariat reports directly to the minister, manages its own budget and has more resources. Figure 4.4 shows where the Secretariat for Information Security stands within the broader structure of the GSI/PR. This important evolution reflects the increased awareness of the importance of digital security in the government. With a budget of USD 433 000 (BRL 1.7 million), the secretariat comprised 30 staff in January 2020 (including 8 working for CTIR.gov, see below), which represents a 100% increase compared to the previous year.

Most senior positions in the GSI/PR are held by high-ranking military officers.8 The GSI/PR also hosts the Brazilian Intelligence Agency (Agência Brasileira de Inteligência, ABIN) and the Secretariat for Defence and National Security Affairs addresses issues related to the security of critical infrastructures, co-ordinates crisis management and carries out actions related to crisis prevention. However, many of the newly created positions created at the Secretariat for Information Security are filled by staff from other ministries, Anatel and public companies.

The Secretariat for Information Security is responsible for:9

planning and supervising information security within the federal public administration, including incident management, data protection,10 security accreditation and the handling of confidential information

formulating and implementing the public administration’s information security policies

elaborating normative and methodological requirements related to information security in the federal public administration

managing the government CSIRT (CTIR.Gov), co-ordinating and carrying out actions for the management of incidents, and co-ordinating the network of government agencies’ and entities’ CSIRTs

proposing and participating in international treaties, agreements or acts related to information security

acting as a central security accreditation body for the treatment of classified information

supervising the security accreditation of individuals, companies, agencies and entities for the treatment of confidential information

co-ordinating with the state, municipal and Federal District’s governments; civil society; and organs and entities of the federal government, for the establishment of guidelines for information security policies for the public sector.

The secretariat includes three major branches:

1. The General Coordination of Security and Accreditation Centre (Coordenação-Geral do Núcleo de Segurança e Credenciamento, CGNSC),11 which addresses issues related to information classification in the government.

2. The General Coordination of Information and Communications Security Management (Coordenação-Geral de Gestão da Segurança da Informação e Comunicações, CGSIC),12 which elaborates proposals for information security guidelines, strategies, norms and recommendations; develops proposals for the National Information Security Plan; monitors its execution; plans and co-ordinates measures to guide information security implementation, such as for raising awareness and training; and monitors the doctrinal and technological evolution of activities related to information security at the national and international levels.

3. The General Coordination of Government Network Incident Handling Centre (CTIR.Gov), the government CSIRT13 (described below).

The CGSI, gathering 21 ministries and government bodies covering a very large part of the federal public administration, provides advice to the GSI/PR. It meets at least twice a year and may establish up to four temporary sub-groups that cannot have more than seven members. The GSI/PR serves as the executive secretariat of the CGSI.14 The further operationalisation of this committee and the creation of working groups is one of the secretariat’s main objectives in 2020. For example, a working group within the Ministry of Economy is exploring the economic aspects of digital security in Brazil.

In November 2018, the Brazilian government published Decree 9.573 establishing the National Policy for the Security of National Critical Infrastructures. The policy aims to ensure the security and resilience of the country’s critical infrastructure and the continuity of services. The policy’s principles are: prevention and precaution; integration between government levels and branches, the private sector, and other segments of society; cost reductions benefiting the society resulting from investments in security; and safeguarding defence and national security. It also establishes the Integrated Critical Infrastructure Security Data System, the National Critical Infrastructure Security Strategy and the National Critical Infrastructure Security Plan. To address the complexity of digital security of critical infrastructures, a central organisation is expected to be established in order to co-ordinate all of the actors involved, public or private, as well as to call for accountability and action.

Each public sector entity is responsible for its digital security

The PNSI establishes a general principle whereby each organ and entity of the public administration is responsible for managing digital security in its own scope of action, including through the elaboration of its information security policy, designation of an internal information security manager, establishment of an information security committee, training, etc.15

The Ministry of Transparency and the Union Comptroller Office is tasked with auditing the implementation of the PNSI’s activities under the responsibility of federal organisations and entities.

Central Bank of Brazil

In April 2018, the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) published a resolution16 to provide for the digital security policy and requirements on data processing and storage, including cloud computing. Such requirements shall be observed by financial institutions and other organisations authorised by BCB to operate in the financial market.

Financial institutions should implement and maintain a policy framework for digital security, respecting principles and guidelines for confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information systems and data.

The policy framework must include: the institution’s digital security objectives; procedures and controls to reduce the institution’s vulnerability; classification of data and information by relevance; definition of parameters to be used to assess incidents; mechanisms for dissemination of digital security culture in the institution; and information-sharing initiatives on relevant incidents.

BCB made other requirements, such as digital security policy disclosure to all employees; incident response and action plans; adoption of hard safety issues when contracting data-processing, storage and cloud-computing processes; and setting up monitoring and control mechanisms to ensure the implementation and effectiveness of the digital security policy.

BCB may rule out or restrict data-processing, storage and cloud-computing services contracts whenever it detects non-compliance with the provisions of the resolution or other BCB regulations. BCB may then establish a deadline for compliance.

BCB’s technical digital security expertise relies in part on its CSIRT, which serves the financial sector and is in contact with large banks in the country.

ComDCiber (Ministry of Defence)

Issues related to national security and cyber defence, which are not in the scope of this section, are under the responsibility of the Cyber Defence Command (ComDCiber) and the Cyber Defence Centre (CDCIber), both specialised command bodies part of the Brazilian army. However, it is important to highlight the role played by ComDCiber, which has significantly more resources and staff than the GSI/PR, in particular at the technical level, and can take initiatives beyond the strict protection of the defence domain, such as the Cyber Guardian Exercise.

The second edition of the Cyber Guardian Exercise took place on 2-4 July 2019 at ComDCiber in Brasilia. About 200 members from 40 organisations participated in this simulated digital security exercise, including representatives from the financial, nuclear, electrical and telecommunications sectors. ComDCiber conducted the simulated training in a shared environment with other agencies. The initiative fostered collaborative action between government agencies, academia, private sector organisations, and the wider security and defence community.

The virtual simulation used the Cyber Operations Simulator (SIMOC) programme, which emulated computer systems used by participating agencies and companies. The constructive simulation used information technology, media, legal and senior management crisis offices, which provided solutions for security events which could impact those organisations. Discussions in crisis offices resulted in action at the decision-making and management level (crisis management) as well as at the technical level (incident response). Through SIMOC, attack situations against critical infrastructures were reproduced in electrical, telecommunications, financial and nuclear environments.

For example, the nuclear exercise comprised three groups working in co-operation: the crisis cabinet, the nuclear regulatory framework implementation team and digital systems test team. The digital systems test team used a simulator to test digital systems installed in nuclear plants, which serves as a cyber training tool. The simulator is part of a project by the National Atomic Energy Agency, developed by the Navy Technology Centre in São Paulo and the University of São Paulo. It is used by 17 institutions from 13 countries.

Participants acted collaboratively to prevent and resolve incidents involving information assets relevant to national defence. With this exercise, ComDCiber aims to integrate government, the private sector and academia in enhancing the protection of the national cyberspace.

Other actors of Brazil’s digital security governance

The National Institute of Information Security

The National Institute of Information Security (Instituto Nacional de Tecnologia da Informação, ITI) maintains and implements the policies of the Brazilian public key infrastructure (ICP-Brasil), including the operation of Brazil’s root Certification Authority. The ITI is also in charge of accrediting, discrediting, supervising and auditing the other participants in the trust chain.17 The ITI is a federal agency linked to the Chief of Staff of the Presidency of the Republic (Casa Civil). It follows the operating rules established by the ICP-Brasil Steering Committee, whose members are nominated by the President of the Republic and include representatives of public authorities, civil society and academia.18 The ICP-Brazil’s Steering Committee, the ITI and accredited entities perform audits of the Brazilian PKI.19 There are currently 17 first-level certification authorities in Brazil,20 and 8 time-stamping service providers.21

Anatel, the telecommunications regulator

As Brazil’s telecommunications regulator, Anatel also plays a role with respect to digital security in the country. Currently, there is limited co-operation and information sharing within the private sector on digital security, apart from trusted personal relationships between key individuals. Until now, security in the telecommunications sector is mainly self-regulated. Anatel started to focus on this issue through a public consultation launched at the end of 2018, which may result in the establishment of a committee of experts composed of all actors (e.g. operators, equipment providers, etc.) to share experiences, collectively discuss possible issues to be addressed, identify minimum requirements and best practices, etc. Anatel is responsible for certifying telecommunications equipment, including with respect to security requirements.

Anatel has adopted regulation with respect to protecting critical infrastructure and co-operates with the Ministry of Defence on exercises (cf. Cyber Guardian).

Computer emergency response teams and computer security incident response teams

There are over 40 computer emergency response teams (CERTs) and computer security incident response teams (CSIRTs) in Brazil, which can be grouped into 8 categories: 1) national responsibility; 2) international co-ordination; 3) critical infrastructures; 4) corporate; 5) providers; 6) academic; 7) government; 8) military. They co-operate in a broad ecosystem with a mix of institutional and personal trusted relationships. Two of them have a national responsibility and act as international contact points: CTIR.gov (mentioned above) for the federal government and CERT.br for the private sector.

CERT.br is maintained by NIC.br, the executive branch of the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee (CGI). It is responsible for:

Handling voluntary computer security incident reports and activity related to Brazilian networks connected to the Internet. CERT.br collects incident reporting from any organisation and citizens. It provides a focal point for incident notification in the country, as well as co-ordination and support for organisations involved in incidents.

Increasing security awareness. Together with NIC.br and CGI.br, CERT.br contributes to the portal internetsegura.br, which provides a wide array of educational material for various target audiences (children, teenagers, teachers, the elderly, etc.). The portal also provides links to many other awareness-raising and educational activities carried out by other entities in Brazil.22

Carrying out network monitoring and trend analysis activities, including by maintaining an early warning project to identify new trends and correlating security events, as well as alerting Brazilian networks involved in malicious activities. CERT.br is an Anti-Phishing Working Group Research Partner, and a member of the Honeynet Project, with the HoneyTARG Chapter.

Training and capacity building. CERT.br helps new CSIRTs to establish their activities in the country and delivers training for public and private sector information security professionals.23

Participating in international CSIRTs fora. CERT.br leads LACNIC CSIRT initiatives that foster co-operation in the Latin American region. It also participates in the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST) as a member and through initiatives to improve global incident handling capabilities. CERT.br’s general manager served as a member of the FIRST Board in 2012/13 and CERT.br staff currently take part in three FIRST working groups (CSIRT Services Framework, Membership Committee and Ethics SIG).

The Brazilian Government Response Team for Computer Security Incidents – CTIR.Gov, a division of the Institutional Security Cabinet of the Presidency of the Republic – addresses incidents on federal administration networks in Brazil. CTIR.Gov acts on the implementation of co-operation agreements with other federal incident handling teams, as well as with other national and international public and private CSIRTs, aiming at technical co-operation and mutual assistance on treating security incidents. CTIR.Gov provides:

Reactive services initiated as soon as a notification arrives, followed by proper analysis of the incident and interactions with the originator. Patterns and tendencies revealed by continuous event observation serve as input to security recommendations issued to the concerned entities.

Proactive services designed to prevent incidents or to reduce the impact of supervening events. These services are composed of information assets analysis and constitutive structures from different information technology environments in the federal administration, and provide a broad view of the available resources, their values, and associated risks.

CERT.br and CTIR have respectively a staff of ten and eight. CTIR doubled its staffing in 2019. Both CERTs work co-operatively with other trusted CERTs in Brazil and abroad. The National Education and Research Network has its own Security Incident Response Centre (CAIS).24 With over 20 years of experience, CAIS was one of the first security incident response groups to operate nationally in the detection, resolution and prevention of incidents on the academic network.

Key findings and challenges

Brazil reached a turning point in 2018-19 with the adoption of its Digital Transformation Strategy and National Information Security Policy, as well as the preparation of its National Cybersecurity Strategy. A review of existing policy documents combined with elements collected during interviews reveal several key findings.

Brazil’s primary digital security focus on national security is evolving to include economic and social aspects

The focus of digital security policies in Brazil has evolved from a technical dimension in 2000-11, to a national security dimension in 2012-18, driven in part by the organisation of mega-events and the revelations by Edward Snowden about cyberespionage by the United States. The overarching mission of the Strategy for Information and Communications Security and Cyber Security in the Federal Public Administration 2015-2018, which was to “ensure and defend the interests of the state and society for the preservation of national sovereignty”, illustrates this evolution.

The 2018 Digital Transformation Strategy, which aims to “embrace digital transformation as an opportunity for the entire nation to take a leap forward”, is the first Brazilian policy document to address digital security as part of a broad prosperity agenda and not solely from the national security perspective. Digital security is presented as part of an enabling thematic axis on “trust and confidence” and the recommended strategic actions primarily focus on measures that can support the digital transformation in Brazil from an economic and social perspective. The thematic axis also addresses the “protection of rights and privacy”, echoing the trust policy dimension of the OECD Going Digital Integrated Policy Framework (OECD, 2019a). The Digital Transformation Strategy can therefore be viewed as a first step towards broadening the scope of Brazilian digital security policies to economic and social prosperity.

Nevertheless, the PNSI, published later in 2018, includes national sovereignty and human rights as the first and second principles, but does not consider economic and social prosperity as an objective of digital security.

A comparison of these two documents shows that this evolution is progressive. It is likely that each document reflects the perspective of the bodies that have developed it, namely the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovations and Communications for the Digital Transformation Strategy, and the GSI/PR for the PNSI. The content of the National Cybersecurity Strategy and the consultation process carried out by the GSI/PR for its development demonstrate that Brazil is heading towards a more holistic approach to digital security, placing more emphasis on the economic and social dimension.

Brazil is at an early stage of promoting digital security across society

The general perception among experts in Brazil is that the government is starting to elevate digital security as a priority for the economy and society and that, apart from very large firms and some specific public sector bodies, most public and private stakeholders are not giving enough attention and resources to this issue.

In addition, over time, policy documents in Brazil have been using different concepts and terms to cover different aspects of digital security, including information security, cybersecurity, cyber defence, data protection, as well as related terms such as information assets, critical infrastructure, cyberspace, etc. Where available, definitions have not always been consistent over time, which can be explained by many factors, including that the approaches themselves have been evolving. However, definitions are sometimes confusing. For example, the PNSI defines information security as including cybersecurity, cyber defence, physical security and protection of organisational data; as well as actions to ensure the availability, integrity, confidentiality and authenticity of information (Article 2). This suggests that actions to ensure availability, integrity, confidentiality and authenticity are different from cybersecurity and cyber defence, which themselves are not defined.25

In addition, interviews carried out for this Review have shown that, beyond a circle of “information security” experts, there is widespread confusion between digital security and “data protection” (i.e. privacy protection). Many actors do not distinguish between the two areas and do not understand their relationship, including how they can strengthen or undermine each other. This situation is likely to evolve following the full implementation of the data protection law in Brazil.

This shows that the conceptual basis for approaching digital security policy in Brazil has considerably evolved over the last decade and is entering a new phase with the adoption of the National Cybersecurity Strategy.

At this juncture, a key challenge for Brazil is to recognise that, although in theory, “cybersecurity” (or “information security”, depending on terminological preferences) can be viewed as a monolithic challenge, it is in reality a multidimensional policy area. In practice, it can cover at least four dimensions: 1) national security; 2) economic and social prosperity; 3) technology; and 4) law enforcement ( Figure 4.5).

Actors and communities addressing each dimension have different cultures, backgrounds and objectives and can sometimes converge, overlap or compete, depending on the context and precise issue. Cryptography policy is a typical example of competing objectives, with businesses, organisations and consumers promoting the unregulated use of cryptography to support trust and facilitate e-commerce, digital governments and innovation on line, while law enforcement and intelligence call for more regulation to facilitate access to encrypted data in order to combat criminals and terrorists. Digital security of critical activities and infrastructure is another example where tensions can appear between economic and social prosperity and national security objectives, depending on the situation.

Ideally, terminology should reflect distinctions between the dimensions of digital security. For example, to reduce confusion and potential misunderstandings, the 2015 Security Risk Recommendation uses the term “digital” instead of the prefix “cyber”. The term “digital” is consistent with expressions that characterise the economic and social perspective of ICT policy, as in “digital economy”, “digital transformation”, “digitalisation”, etc. It is also common in business environments. In contrast, the prefix “cyber” is often used in relation to law enforcement (cybercrime) as well as national/international security (cyber warfare, cyber defence, cyber espionage, cyber command, etc.). The Security Risk Recommendation also uses the expression “digital environment” instead of “cyberspace”, which is common in military doctrines as a domain of operations in addition to air, sea and land.

The main priority for Brazil is to raise awareness and promote the adoption of good digital security practices by all stakeholders

Brazil has made an important step forward with the acknowledgement of digital security as an enabler of economic prosperity in its Digital Transformation Strategy. In line with the first principle of the OECD Security Risk Recommendation (Box 4.2), the next step is to raise the awareness of businesses, public sector organisations and individuals about the importance of digital security to foster trust and support digital transformation; and to encourage them to adopt good digital security practices, enhance their digital security skills and empower them to manage digital security risk.

The 2015 Security Risk Recommendation includes eight principles that describe how to approach digital security without inhibiting the economic and social benefits from digital technologies. It is based on the understanding that the overarching objective of digital security is to increase the likelihood of success of an economic and social activity rather than to create a state of security, i.e. entirely eliminating the risk. Security is an enabler for prosperity, not an end in itself, which is why it should be a business-driven rather than a technology-driven process. Decision makers in organisations should manage the economic opportunities and security risks from using digital technologies in tandem. To take the most appropriate risk management decisions from a business perspective, leaders and decision makers should own digital security risk management rather than delegating it to technical digital security experts. They should, however, work with them to understand the threats and vulnerabilities as well as the options to reduce the risk.

General principles

1. Awareness, skills and empowerment. All stakeholders should understand digital security risk and how to manage it.

2. Responsibility. All stakeholders should take responsibility for the management of digital security risk.

3. Human rights and fundamental values. All stakeholders should manage digital security risk in a transparent manner and consistently with human rights and fundamental values.

4. Co-operation. All stakeholders should co-operate, including across borders.

Operational principles

5. Risk assessment and treatment cycle. Leaders and decision makers should ensure that digital security risk is treated on the basis of continuous risk assessment.

6. Security measures. Leaders and decision makers should ensure that security measures are appropriate to and commensurate with the risk.

7. Innovation. Leaders and decision makers should ensure that innovation is considered.

8. Preparedness and continuity. Leaders and decision makers should ensure that a preparedness and continuity plan is adopted.

Source: OECD (2015), Digital Security Risk Management for Economic and Social Prosperity: OECD Recommendation and Companion Document, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264245471-en.

To do so, it is important to understand that, in organisations, digital security is primarily an economic and social challenge rather than only a technical issue and why digital security risk management should be a business, as opposed to a technical, process.

First, digital security incidents due to insufficient digital security risk management will potentially harm an organisation’s economic and social objectives, operations, competitiveness, and reputation, as well as its customers’ and users’ trust and, potentially, privacy. Therefore, ensuring effective digital security risk management should be a business (as opposed to a technical) leadership’s responsibility. To the extent that it can threaten the organisation as a whole, it should be owned by the highest level of leadership and followed at board level in an organisation-wide manner.

Second, although digital security measures aim to protect economic and social activities, they can also inhibit them by increasing costs, reducing performance and the openness and dynamic nature of the digital environment, which are essential to realising the full benefits of digital transformation. Business (as opposed to technical) decision makers should own digital security risk related to their business activities rather than delegate it to technical security experts. While technical security experts understand the technical aspects of digital security risk, they cannot assess the possible business impact of security measures on every line of their organisation’s business and support activities. They should, however, support business decision makers as best they can to ensure their informed risk management decisions.

For example, one option to eliminate a virus from a system might be to shut down that system, clean it and turn it back on. While this may sound like a technical decision, it is in fact a business decision, because there might be negative business consequences in interrupting that system, such as stopping a production line or preventing customers from placing orders, etc. The decision maker owning the responsibility for shutting down the system should also own the responsibility for the possible negative consequences of doing it. S/he relies, however, on technical experts to most appropriately assess the technical risk and take the best-informed risk management decision.

Last, although they aim to create trust, digital security measures can also undermine confidence by raising suspicion related to human rights and fundamental values, in particular privacy. Digital security and privacy protection can reinforce or undermine each other depending on how they are managed. It is therefore essential that digital security and privacy protection be approached in a coherent manner, including from a legal and ethical perspective.

As a result, leaders and decision makers in organisations need to adopt a business-driven (as opposed to a technology-driven) approach that leads to the most appropriate selection and management of digital security measures, in light of the economic and social activities at stake as well as the need for trust and confidence. They should understand and be responsible for digital security risk and work in co-operation with technical security experts to take digital security decisions.

This means that public policies aiming at encouraging businesses and public sector organisations to step up their digital security should target leaders and decision makers as well as ICT professionals and experts, instead of only the latter.

Brazilian policies promote a risk management approach to digital security (e.g. the PNSI, Article 3-VIII) and encourage the implementation of information security risk management standards in the public administration. However, they primarily focus on the protection of information systems, networks and data rather than on the economic and social activities that rely on them. In other words, they approach digital security as a technical rather than as an economic and social matter. Most countries have followed the same steps, at different paces, and many are struggling to shift from a technical to an economic and social digital security approach. The development of the National Cybersecurity Strategy provides an opportunity for Brazil to make progress in this area.

Brazil should establish more robust and better resourced governance for digital security

The Digital Transformation Strategy, the PNSI and the National Cybersecurity Strategy cover many key aspects of an up-to-date digital security policy framework. These include standards and norms for digital security in the public administration, awareness raising, education and skills development, research and innovation, the protection of critical infrastructure, etc. However, most of them are addressed at a very high level, and implementation measures have not yet been defined. Implementation plans are expected to fill the gap. The definition and implementation of many of these implementation plans will require collaboration across several federal government agencies, regional and local bodies, as well as non-governmental stakeholders.

The Digital Transformation Strategy and the PNSI also mention human rights, fundamental values and privacy, as well as multi-stakeholder collaboration. These areas are particularly important, and can be challenging for Brazil.

Since 2006, digital security governance has been co-ordinated by the GSI/PR, an entity that has developed a certain degree of expertise in this area but which is characterised by its national security/military culture. During this period, some have criticised

the excessive securitisation and accentuated militarisation of cybersecurity; the exclusion of non-state actors from the definition of terms relevant to the political agenda; the increasing preference for solutions which seek to block applications and remove content; and the continuous difficulty of co-ordinating action at the level of the federal public administration (Hurel and Cruz Lobato, 2018).

The GSI/PR’s Secretariat for Information Security reports to the same minister as the Brazilian Intelligence Agency.

A key challenge for the GSI/PR will be to build trust with other government agencies at different levels (e.g. federal, regional, local, etc.), businesses (including foreign companies) and other non-governmental stakeholders in order to establish a long-standing partnership to promote digital security for prosperity in Brazil.

The Department for Information Security at the GSI/PR has significantly evolved over time. It has more and diversified staff, is better recognised at the political level, in particular following its elevation to a secretariat. It has also adopted a more open culture, illustrated by the working groups organised to develop the first draft of the National Cybersecurity Strategy through the public consultation held to gather input for the document. Many stakeholders have praised this evolution, noting, however, that the consultation process could have benefited from more publicity in order to involve more stakeholders. This is definitely a step in the right direction.

A key challenge is that the GSI/PR does not have competence to regulate the private sector. Instead of regulating, it publishes standards, makes their implementation mandatory by the federal administration, and encourages their voluntary adoption by other stakeholders. This includes various means, such as requiring compliance with these standards for public procurement. The general Brazilian governance approach with respect to digital security regulation is decentralised: as illustrated by the Central Bank example above, sectoral regulators are competent to regulate digital security in their area. As there is no centralised digital security agency in Brazil, sectoral regulators are invited to build upon the standards and good practices provided by the GSI/PR. This approach is closer to that of Sweden and the United Kingdom rather than France.

There is no universal model for digital security policy governance. Centralised and decentralised approaches have different pros and cons. For example, the decentralised approach enables sectoral regulation carried out by sectoral regulators to be better tailored to the sector’s specificities. However, it raises the issue of each sectoral regulator aggregating a sufficient critical mass of expertise in order to be able to issue balanced and effective regulation, as well as to supervise its implementation. It also creates a situation where regulated entities may be reluctant to share digital security risk-related information with a government body tasked with regulating their activities more generally.

More generally, most governments have been struggling to set the most appropriate governance framework for cybersecurity, finding it difficult to strike the right balance between economic and social, national security, criminal law enforcement, and technical aspects. A good practice is to recognise the need for a whole-of-government approach co-ordinated at a high level of government with a view to balance the potentially competing objectives of each dimension. However, again, there is no one-size-fits-all model for how to implement this good practice. Governance frameworks and co-ordination mechanisms vary considerably, reflecting countries’ history, style of government and maturity in this area.

For example, Australia, Japan and the United Kingdom have assigned policy co-ordination to the Prime Minister through the Cabinet Office. France established a national co-ordination agency within a pre-existing co-ordination body under the Prime Minister (ANSSI), and Israel created a national agency reporting directly to the Prime Minister (INCD); the United States established a Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) in its Department of Homeland Security; Canada, Germany and the Netherlands have placed the main responsibility for digital security under an existing ministry (respectively Public Safety, Interior, and Security and Justice). In all of these cases, there are also different arrangements with respect to which agency or agencies) is/are responsible for policy and operational matters. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Department for Culture, Media and Sports is responsible for economic and social policy while the National Cyber Security Centre is responsible for operational aspects. In contrast, both aspects are addressed in a centralised agency in France. In Germany, the Ministry of Interior has the lead for public policy making but the Federal Office for Information Security has the technical competence and responsibility. Lastly, multi-stakeholder co-ordination is also concretely carried out differently across countries. In many countries, it took a couple of new versions of the initial cybersecurity strategy to set a relatively stable governance model.

Conclusions and recommendations

The new National Cybersecurity Strategy is clearly a step in the right direction. However, as the economic and social initiatives to promote digital security need to be scaled up to match the government’s expectations reflected in the Digital Transformation Strategy, several issues arise.

Implementation of the strategy

The adoption of the strategy is an excellent first step, but it now needs to be translated into specific action items. In doing so, it is important to recognise that Brazil is at an early stage of development in this area and needs to take a step-by-step approach, distinguishing short-, medium- and long-term priorities.

Policy recommendations: To develop the agenda for the implementation of the National Cybersecurity Strategy, the government should build upon and expand the multi-stakeholder efforts undertaken to develop the strategy. For example, it could create a broad community of digital security leaders in the public and private sectors, academia, and civil society and hold annual meetings to develop the implementation plan and assess progress in its implementation over time. Such meetings would also provide an opportunity for the broader multi-stakeholder Brazilian digital security community to emerge, gather and dialogue, including through a national conference. It could aim at eventually becoming the main cybersecurity event in Brazil and Latin America, echoing, for example, the Israeli Cyber Week (Tel Aviv), the Dutch ONE Conference (The Hague), the French International Cybersecurity Forum (Lille) or the Singapore International Cyber Week.

Being at an early stage, awareness raising and education are particularly critical. In practice, Brazil should identify gaps in awareness and knowledge about digital security in society among businesses, governments and individuals. On this basis, it should develop an action plan to strengthen digital security training and education programmes at all levels (primary, secondary, higher education and vocational training), identify existing digital security experts who can teach and train the trainers, perhaps through a national register of digital security trainers; and encourage students to pursue carriers in digital security. The recently published National Cybersecurity Strategy points in this direction.

It will also be important for Brazil to periodically assess the effectiveness of its strategy, as experience from OECD countries demonstrate. Brazil would benefit from developing tools to evaluate the implementation of the strategy, assess progress and needs to revise the strategy.

Resources

To implement its National Cybersecurity Strategy and match the ambition of its Digital Transformation Strategy, Brazil will need to make a significant effort to allocate more resources to digital security. The government has doubled digital security resources at the GSI.PR in a single year. However, with only 30 staff addressing digital security, including 8 for incident response, more financial and human resources efforts will be needed over several years.

Policy recommendations: The government should consider allocating significantly more resources for digital security so as to ensure appropriate implementation of the National Cybersecurity Strategy. For example, each area covered by the implementation plan could be assigned a clear budget for a well-defined period in order to reach clear and measurable milestones. Resources should not be allocated only to technology, but also cover all other aspects. In addition, the government could work with the private sector and academia to better understand the cost of malicious digital security activities to the economy.

Co-ordination and decentralised responsibilities

According to the National Cybersecurity Strategy, the GSI/PR will continue to co-ordinate digital security at the national level. Is the GSI/PR the most appropriate institution to promote digital security risk management to the private sector, to encourage digital security innovation, to stimulate digital security education and training, etc.?

Policy recommendations: It seems that, to achieve the best results, Brazil should follow a co-ordinated decentralised approach, where different ministries and agencies would have the lead in their area of competence, leveraging their expertise and networks, with the GSI/PR having a co-ordination role. However, there is currently limited digital security expertise that can be leveraged outside of the GSI/PR to develop more tailored initiatives led by other ministries and agencies. One option would be for Brazil to train digital security policy experts to progressively enable each ministry and agency to start developing and implementing action plans in their respective areas.

Multi-stakeholder dialogue

Will the military and national security culture inherent to the GSI/PR be appropriate in the long run to promote digital security as an economic and social challenge and to facilitate trusted relationships with all economic and social actors? Digital security is an economic and social policy priority that requires the participation of all stakeholders. Sustainable trust between the co-ordinating government agency, other parts of the government and non-governmental stakeholders is essential. It aims to: establish a constructive public-public and public-private dialogue with a large number of stakeholders; ensure that policy measures are appropriately balanced and do not create unnecessary obstacles to the use of digital technologies for innovation and growth; create the conditions to share risk-related information with businesses; facilitate the promotion and dissemination of good practice throughout society by civil society; and ensure the protection of privacy and other human rights. The organisation and simplification of digital security governance in Brazil should aim at enabling digital security to grow while engaging all stakeholders in a sustainable manner.

Policy recommendations: One option might be to build on the lessons learnt from the Brazilian Internet governance model (CGI) to create a multi-stakeholder setting to facilitate debates and co-ordination. In addition, the government should encourage the establishment of a digital security governance structure for the private sector. It should also facilitate the creation of groups bringing together chief information security officers and other security professionals throughout Brazil, without necessarily taking part in their discussions. Such groups would then become discussion partners for the government, thereby facilitating the exchange of information on digital security threats, vulnerabilities, incidents, and risk management measures in both the public and private sectors.

In order to enhance digital security, Brazil should take action in the following areas:

Implementation of the National Cybersecurity Strategy: Build upon and expand the multi-stakeholder efforts undertaken to develop the National Cybersecurity Strategy in order to build the agenda for its implementation.

Awareness raising and education: Identify gaps in awareness, knowledge and digital security among businesses, governments and individuals, and develop an action plan to strengthen digital security training and education at all levels.

Resources: Allocate significantly more resources for digital security in order to ensure appropriate implementation of the National Cybersecurity Strategy, covering all aspects rather than only technology.

Governance: Follow a co-ordinated decentralised approach, where different ministries and agencies would have the lead in their area of competence, with the GSI/PR having a co-ordination role; and train digital security policy experts to overcome the current lack of experts in each ministry and agency.

Multi-stakeholder dialogue: Build on the lessons learnt from the Brazilian Internet governance model to create a multi-stakeholder setting facilitating debates and co-ordination; encourage the establishment of a digital security governance structure for the private sector; facilitate the creation of groups bringing together chief information security officers and other security professionals.

Brazil passed the General Data Protection Law (Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados, LGPD) on 14 August 2018 (Law 13.709). It forms the main part of Brazil’s legal framework for governing the collection, storage and use of personal data. Initially developed by the Ministry of Justice, the LGPD underwent extensive public consultation with a large number of stakeholders from civil society, academia and the business community over a seven-year period. Consultations were also held within government, involving different ministries and public organisations. Preliminary hearings and national consultations on the draft law were also subject to discussions in both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies.

The LGPD was originally to become effective in February 2020. However, as a result of the enactment of the Executive Order MPV 869 of 27 December 2018, which was enacted into law as Law 18.583 of 8 July 2019, the term was extended to August 2020. On 3 April 2020, the Brazilian Senate approved a bill of law (PL 1179/2020) with several emergency measures to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. The bill includes a specific rule that postpones the LGPD’s entry into force until January 2021.

The next section examines in some detail the legal framework and how organisations (in both public and private sectors) are preparing for its implementation. In addition, it will review how the new law and existing data governance frameworks provide for the transfer of data to other countries.

Overview of Brazil’s General Data Protection Law

Before the publication of the LGPD, Brazil’s approach to privacy and data protection was either sector-specific or too broad. Privacy and data protection were regulated by different laws covering, for example, financial services, healthcare, telecommunications and consumer protection. At the same time, the Brazilian Constitution provides for a general level of protection. Enforcement was left to the discretionary powers of the national and local regulatory authorities and agencies.

The LGPD was drafted to create the conditions for greater consistency and uniformity in privacy and data protection legislation and the way individuals could exercise their privacy rights across the Brazilian territory. The law is largely based on the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the 1980 OECD Recommendation of the Council concerning Guidelines Governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data (hereafter “OECD Privacy Guidelines”; amended on 11 July 2013) (OECD, 2013), as well as in Convention 108 of the Council of Europe.

The LGPD takes a broad view of what data qualify as personal data, even more expansive than the GDPR and the OECD Privacy Guidelines. For example, the Brazilian law has a specific provision (Article 12, Paragraph 2) by which anonymous data may fall within the scope of the law if they are used to evaluate certain aspects of a natural person and create behavioural profiles (e.g. price discrimination methodologies).

Notably, the LGPD covers the collection and processing of personal data and information for both the public and private sectors. The processing of personal data has to be conducted in good faith and in accordance with the principles listed below, which are consistent with the principles of the OECD Privacy Guidelines:

purpose specification

suitability

necessity

free access

data quality

transparency

secure safeguards

prevention

non-discrimination

accountability.

Furthermore, the LGPD is concerned not only with an extensive qualification of consent, but also with empowering data subjects with meaningful control and choice regarding their personal information. The LGPD lists nine fundamental rights that data subjects have, which are essentially the same rights the GDPR mentions. Another similarity with the GDPR is that the LGPD applies to any business or organisation that processes the personal data of individuals in Brazil, regardless of where that business or organisation itself might be geographically located.

While the GDPR has six legal basis for processing personal data, Article 7 of the Brazilian LGPD lists ten (Box 4.4). There are, therefore, more legal authorisations for data processing, making it possible to interpret, at least theoretically, the LGPD as more flexible and less restrictive than the GDPR in relation to the processing of personal data.

1. With the consent of the data subject.

2. To comply with a legal or regulatory obligation of the controller.

3. To implement public policies provided in laws or regulations or based on contracts or agreements.

4. To conduct studies by public research entities that ensure whenever possible the anonymisation of personal data.

5. To execute a contract or preliminary procedures related to a contract of which the data subject is a party, at the request of the data subject.

6. To exercise rights in legal, judicial, administrative or arbitration procedures.

7. To protect the life and physical safety of the data subject or a third party.

8. To protect health.

9. To fulfil the legitimate interest of the controller or a third party.

10. To protect credit (referring to a credit score).

Data portability

One of the new data subject rights in the GDPR is the right to portability, which has also been imported into the Brazilian law. Such a right mandates the controller to transfer, at the request of the data subject, their personal data to other controllers. In the Brazilian law, this right is not limited to data provided based on the data subject’s consent, making it different from the GDPR.

The right to data portability is not a new right under the legal framework of Brazil. Portability is also present in other instances in Brazilian law. In the telecommunication services sector, for example, this right is currently regulated under Resolution 460/07,26 better known as the General Portability Regulation of Anatel. Under this resolution, users of telecommunications services have the right to request the portability of their contracts (and, therefore, the related personal data) in relation to land and mobile telephone lines from telecommunication service providers of collective interest.

The LGPD imported the right to data portability from Article 20 of the GDPR, defining that the data subject may exercise this right through an express request to the provider of goods or services, according to further regulation to be provided by the ANPD. Nevertheless, there are major differences. One of them is that the GDPR establishes a major threshold that requires the specific consent of the data subject or that the request to data portability be based on an existing contractual relation in order to be able to request this right from a data controller, and as long as this is technically feasible. Further, the GDPR establishes an exemption to exercise this right when the processing of personal data is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of an official authority vested in the controller.

National Data Protection Authority

Provisional Measure 86927 of 27 December 2018 created rules for co-ordination within the government, mandating the creation of a permanent communication forum for technical co-operation between governmental bodies responsible for sectoral regulation. According to the provisional measure, the National Data Protection Authority (Autoridade Nacional de Proteção de Dados, ANPD) is considered the central governmental body of the public administration responsible for interpreting the LGPD and in enforcing the sanctions created by the law.

Provisional Measure 869 was voted into law by the Senate and by the House of Representatives and became Law 13.853 of 8 July 2019. It creates the ANPD in charge of the oversight of the LGPD. The ANPD is an entity of the federal public administration created as part of the Presidency of the Republic, with “technical and decision-making autonomy” guaranteed by the law (Article 55-B). It is composed of six main entities:

a) Board of Directors

b) National Council for the Protection of Personal Data and Privacy (Conselho Nacional de Proteção de Dados e Privacidade, CNPDP)

c) Internal Affairs

d) Ombudsman

e) legal advisory body

f) administrative specialised units.

The Board of Directors will be composed of five directors, which are appointed by the President after approval by the federal Senate. Until the LGPD’s entry into force, technical and administrative support will be provided by the Executive Office of of the Presidency of the Republic (Casa Civil).

The CNPDP will be composed of the representatives of 23 organisations and bodies from the public, private and academic sectors. Its main activities will include proposing strategic guidelines and providing inputs for the preparation of the National Policy for the Protection of Personal Data and Privacy and for the activities of the ANPD, and preparing annual reports to assess the implementation of the actions of the national policies for the protection of privacy and personal data in Brazil.

Article 55-J grants the ANPD a wide range of responsibilities, from handling complaints, enforcing the law and applying sanctions to producing educational materials and guidance. The ANPD’s main competencies and regulatory powers under the LGPD are listed in Box 4.5.

1. Ensure the protection of personal data, in accordance with the legislation.

2. Elaborate guidelines for the National Policy for the Protection of Personal Data and Privacy.

3. Supervise and apply sanctions for the processing of data in violation of the legislation.

4. Promote knowledge among the population of norms and public policies on the protection of personal data and of the security measures.

5. Stimulate the adoption of standards for services and products that facilitate the exercise of data subjects regarding their personal data.

6. Promote international co-operation with the data protection authorities of other countries.

7. Prepare annual activity reports.

8. Amend regulations and procedures on the protection of personal data and privacy, and conduct privacy impact assessments on the protection of personal data in cases where the processing represents a high risk to the guarantee of the general principles of personal data protection.

9. Conduct audits, or determine their performance, within the scope of the inspection activity.

10. Enact simplified and differentiated rules, guidelines and procedures, including deadlines, so that micro and small enterprises, as well as incremental or disruptive business initiatives that declare themselves to be start-ups or innovation companies, can adapt to this law.

11. Communicate any criminal offences they become aware of to the competent authorities.

12. Implement simplified mechanisms, including by electronic means, to register complaints on the processing of personal data in violation of the law.

13. Maintain a permanent forum for communication, including through technical co-operation, with entities of the public administration responsible for regulating specific sectors of economic and governmental activity, in order to facilitate the regulatory, oversight and punitive powers of the National Data Protection Authority.

It is worth pointing out that the executive branch has vetoed certain sections of the LGPD. Specifically, Law 13.853 of 8 July 2019 that creates the ANPD contains a total of nine vetoes, most of them related to the administrative sanctions dealing with the processing of personal information to be imposed by the ANPD.

In addition to the above competencies, Articles 55-J, VI, and 58-B, V of the LGPD (as worded by Law 13.853, from 8 July 2019), attribute responsibility to the ANPD and its NDPPC for disseminating knowledge regarding policies and norms on personal data protection and privacy to society.