Chapter 5. Creating a stronger framework to monitor and evaluate national progress in education

The system evaluation of the Republic of North Macedonia is at a nascent stage of development and, despite progress, still lacks basic components, such as clear objectives for improving learning outcomes and a national assessment that would support efforts to raise achievement. This chapter suggests that North Macedonia enhance its data collection and management to provide timely and high quality data with which to feed information into decision-making. The chapter also suggests how the assessment can be developed to monitor educational progress and provide formative information for improvement. Another priority is to elevate system evaluation to a key function in North Macedonia’s education system, by creating greater institutional capacity.

Introduction

System evaluation is central to education reform. It is important for holding the government and other stakeholders accountable for meeting national education goals. It also provides the information needed to define better policies and make sure that they have their intended impact. In the Republic of North Macedonia (referred to as “North Macedonia” hereafter), system evaluation is at a nascent stage of development. Recent years have seen some important steps towards establishing the institutions and instruments that can support system evaluation. However, many basic components are still lacking, and data systems and the processes for feeding information into decision-making are weak. Among the significant gaps are the absence of clear objectives for improving learning outcomes and a national assessment that would support efforts to raise achievement. These are notable gaps in a context where over half of 15-year-old students in North Macedonia lack the baseline level of skills required for productive participation in society (OECD, 2016[1]).

This chapter suggests several measures that North Macedonia can take to build stronger foundations for system evaluation. It suggests how data collection and management can be enhanced. Reliable, timely and high quality data provide the foundations for understanding what is happening in the education system and where improvements can be made. A central focus of this chapter is a discussion on how the country might develop its new national assessment. The chapter suggests how the assessment can be developed to monitor educational progress and provide formative information for educational improvement. Finally, the chapter looks at how system evaluation can be elevated to a key function in North Macedonia’s education system, by creating greater institutional capacity for this function.

Key features of effective system evaluation

System evaluation refers to the processes that countries use to monitor and evaluate the performance of their education systems (OECD, 2013[2]). A strong evaluation system serves two main functions: to hold the education system, and the actors within it, accountable for achieving their stated objectives; and, by generating and using evaluation information in the policy-making process, to improve policies and ultimately education outcomes (see Figure 5.1). System evaluation has gained increasing importance in recent decades across the public sector, in part because of growing pressure on governments to demonstrate the results of public investment and improve efficiency and effectiveness (Schick, 2003[3]).

In the education sector, countries use information from a range of sources to monitor and evaluate quality and track progress towards national objectives (see Figure 5.1). As well as collecting rich data, education systems also require “feedback loops” so that information is fed back into the policy-making process (OECD, 2017[4]). This ensures goals and policies are informed by evidence, helping to create an open and continuous cycle of organisational learning. At the same time, in order to provide public accountability, governments need to set clear responsibilities – to determine which actors should be accountable and for what – and make information available in timely and relevant forms for public debate and scrutiny. All of this constitutes a significant task, which is why effective system evaluation requires central government to work across wider networks (Burns and Köster, 2016[5]). In many OECD countries, independent government agencies like national audit offices, evaluation agencies, the research community and sub-national governments, play a key role in generating and exploiting available information.

A national vision and goals provide standards for system evaluation

Like other aspects of evaluation, system evaluation must be anchored in national vision and/or goals, which provide the standards against which performance can be evaluated. In many countries, these are set out in an education strategy that spans several years. An important complement to national vision and goals are targets and indicators. Indicators are the quantitative or qualitative variables that help to monitor progress (World Bank, 2004[6]). Indicator frameworks combine inputs like government spending, outputs like teacher recruitment, and outcomes like student learning. While outcomes are notoriously difficult to measure, they are a feature of frameworks in most OECD countries because they measure the final results that a system is trying to achieve (OECD, 2009[7]). Goals also need to balance the outcomes a system wants to achieve, with indicators for the internal processes and capacity throughout the system that are required to achieve these outcomes (Kaplan, R.S. and D.P. Norton, 1992[8]).

Reporting against national goals supports accountability

Public reporting of progress against national goals enables the public to hold government accountable. However, the public frequently lacks the time and information to undertake this role, and tends to be driven by individual or constituency interests rather than broad national concerns (House of Commons, 2011[9]). This means that objective and expert bodies like national auditing bodies, parliamentary committees and the research community play a vital role in digesting government reporting and helping to hold the government to account.

An important vehicle for public reporting is an annual report on the education system (OECD, 2013[2]). In many OECD countries, such a report is now complemented by open data. If open data is to support accountability and transparency, it must be useful and accessible. Many OECD countries use simple infographics to present complex information in a format that the general public can understand. Open data should also be provided in a form that is re-usable, i.e. other users can download and use it in different ways, so that the wider evaluation community like researchers and non-governmental bodies can analyse data to generate new insights (OECD, 2018[10]).

National goals are a strong lever for governments to direct the education system

Governments can use national goals to give coherent direction to education reform across central government, sub-national governance bodies and individual schools. For this to happen, goals should be specific, measurable, feasible and above all, relevant to the education system. Having a clear sense of direction is particularly important in the education sector, given the scale, multiplicity of actors and the difficulty in retaining focus in the long-term process of achieving change. In an education system that is well-aligned, national goals are embedded centrally in key reference frameworks, encouraging all actors to work towards their achievement. For example, national goals that all students reach minimum achievement standards or that teaching and learning foster students’ creativity are reflected in standards for school evaluation and teacher appraisal. Through the evaluation and assessment framework, actors are held accountable for progress against these objectives.

Tools for system evaluation

Administrative data about students, teachers and schools are held in central information systems

In most OECD countries, data such as student demographic information, attendance and performance, teacher data and school characteristics are held in a comprehensive data system, commonly referred to as an Education Management Information System (EMIS). Data are collected according to national and international standardised definitions, enabling data to be collected once, used across the national education system and reported internationally. An effective EMIS also allows users to analyse data and helps disseminate information about education inputs, processes and outcomes (Abdul-Hamid, 2014[11]).

National and international assessments provide reliable data on learning outcomes

Over the past two decades, there has been a major expansion in the number of countries using standardised assessments. The vast majority of OECD countries (30), and an increasing number of non-member countries, have regular national assessments of student achievement for at least one level of the school system (OECD, 2015[12]). This reflects the global trend towards greater demand for outcomes data to monitor government effectiveness, as well as a greater appreciation of the economic importance of all students mastering essential skills.

The primary purpose of a national assessment is to provide reliable data on student learning outcomes that are comparative across different groups of students and over time (OECD, 2013[2]). Assessments can also serve other purposes such as providing information to teachers, schools and students to enhance learning and supporting school accountability frameworks. Unlike national examinations, they do not have an impact on students’ progression through grades. When accompanied by background questionnaires, assessments provide insights into the factors influencing learning at the national level and across specific groups. While the design of national assessments varies considerably across OECD countries, there is consensus that having regular, reliable national data on student learning is essential for both system accountability and improvement.

An increasing number of countries also participate in international assessments like the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the two programmes of the International Energy Agency (IEA), Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS). These assessments provide countries with periodic information to compare learning against international benchmarks as a complement to national data.

Thematic reports complement data to provide information about the quality of teaching and learning processes

Qualitative information helps to contextualise data and provide insights into what is happening in a country’s classrooms and schools. For example, school evaluations can provide information about the quality of student-teacher interactions and how a principal motivates and recognises staff. Effective evaluation systems use such findings to help understand national challenges – like differences in student outcomes across schools.

A growing number of OECD countries undertake policy evaluations

Despite an increased interest across countries in policy evaluations, it is rarely systematic at present. Different approaches include evaluation shortly after implementation, and ex ante reviews of major policies to support future decision-making (OECD, 2018[13]). Countries are also making greater efforts to incorporate evidence to inform policy design, for example, by commissioning randomised control trials to determine the likely impact of a policy intervention.

Effective evaluation systems requires institutional capacity within and outside government

System evaluation requires resources and skills within ministries of education to develop, collect and manage reliable, quality datasets and to exploit education information for evaluation and policy-making purposes. Capacity outside or at arms-length from ministries is equally important, and many OECD countries have independent evaluation institutions that contribute to system evaluation. Such institutions might undertake external analysis of public data, or be commissioned by the government to produce annual reports on the education system and undertake policy evaluations or other studies. In order to ensure that such institutions have sufficient capacity, they may receive public funding but their statutes and appointment procedures ensure their independence and the integrity of their work.

System evaluation in North Macedonia

North Macedonia has established several components that are integral to perform system evaluation. For example, several independent bodies collect valuable data and the Ministry of Education and Science (MoES) has developed an EMIS in order to store information related to students, teachers and schools. Nevertheless, many of these components and processes are not fully exploited, and other aspects of the evaluation framework are still in latent stages of development. As a result, evaluation in the country does not provide the information and analysis that are essential for better understanding and improving the education system. Table 5.1 shows some of the basic components of system evaluation in North Macedonia and main gaps.

There is a national vision for education, but goals should be more specific and measurable

The Comprehensive Education Strategy 2018-25 provides a vision for education that is inclusive, focused on the student and aims to enable future generations to acquire the necessary competencies to meet the needs of a modern, global society (MoES, 2018[15]). The strategy also sets out important policy objectives to improve teaching and learning in North Macedonia, such as reforming curricula, expanding infrastructure and improving teaching quality.

While the strategy sets concrete actions and specifies indicators to measure the outcomes, the indicators are not sufficiently specific, nor are they accompanied by quantifiable targets that can allow for effective monitoring. Given the low performance of students in North Macedonia compared to their international peers (see Chapter 1), the absence of measurable student learning goals is notable. Many countries make learning outcomes a prominent focus of national education goals because this creates a strong lever to direct the system towards improving student achievement.

There are also concerns with how the strategy is being used. Few actors that the review team met perceived the strategy to be a central reference for policy. This may reflect the fact that it does not draw clearly on evidence and evaluations of previous reforms; for example, there is no explicit link to the previous strategy documents from 2005-15 (MoES, 2004[16]) and from 2015-17 (MoES, 2014[17]). The strategy is accompanied by an annex that sets out expected outcomes, indicators of implementation, the year of implementation and the body responsible. However, the document does not provide greater precision on resourcing, implementation steps and detailed timeline delineating how the strategy will translate into action.

The strategy was developed in broad consultation with key stakeholders in the sector, including national and international actors. However, further stakeholder engagement is necessary to advance implementation of the strategy. It seems that the strategy’s development was influenced by the change in administrative sectors and European Union’s (EU) requirements for accession.

Tools to collect evaluation information are unco-ordinated

The country has tools to collect data about the education system, but the collection is unorganised and some instruments, in particular a national assessment, are still being developed. This situation creates overlapping data collection in some domains and no data collection in other crucial areas.

Administrative data collection does not always follow standard definitions and unified procedures

The State Statistical Office (SSO) has started to align collection with international standards set by the joint United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), OECD and the European Statistical Office (Eurostat) data collection. However, international reporting of North Macedonia’s data reveals key gaps, notably on education expenditure, suggesting incomplete national administrative data. In comparison with other countries in the Western Balkans, North Macedonia has more data gaps than others, signalling significant challenges around the quality and availability of data.

In 2010, North Macedonia launched its EMIS, which holds data about students (enrolment, attendance), teachers (employment history, professional development) and schools (maintenance, funding). EMIS does not hold data on the national examination - the state matura - that are stored separately by the National Examination Centre (NEC). Schools are responsible for entering their own data into EMIS. Currently, roughly 1 000 people in the country are authorised to access EMIS. These individuals include school staff who input the data and government officials who might need to view the data.

The quality of data stored in EMIS is sometimes an issue. For example, the review team was told that, in the past, unique student identification numbers were not generated according to the agreed upon format. Instead, schools generated the numbers randomly, making retrieving data difficult and inaccurate. In addition, despite EMIS’s official status as a central source of education data, parallel data collections exist. The information collected by the SSO and reported internationally is requested directly from schools, and it was reported to the review team that MoES staff often bypass EMIS and conduct their own data collections. The parallel data collections do not always follow nationally agreed definitions, creating inconsistencies. For example, how a satellite school is classified (as an individual school or not) according to the SSO and EMIS might differ. This not only leads to problems regarding data accuracy, but also creates an unnecessary administrative burden for schools.

Public reporting of education data are limited

The SSO website offers electronic access to education indicators, which can be downloaded, analysed and re-used. However, the public has little access to EMIS data, as it cannot access and retrieve data from EMIS. Currently, the only front-end portal that allows the public to view portions of EMIS data is e-dnevnik, an electronic gradebook service that mirrors EMIS data and presents student marks. Authorised EMIS users can access EMIS through a back-end interface, but the review team was told that this interface is not user-friendly and even authorised users have difficulties finding data.

A new national assessment is being developed

National assessments in North Macedonia were first introduced in 2001 in the form of a large-scale, sample-based test. The purpose was to identify how students performed compared to established performance standards prescribed in the subject curricula at the end of the grades 4 and 8 in mother language (Macedonian and Albanian) and mathematics (UNICEF, 2017[18]). Sciences and humanities (grade 4) and civic education (grade 6) were also assessed in grade 4. The assessment was implemented until 2006, when it was ended by a new administration.

From 2013 to 2017, a new assessment was administered annually in every grade in randomly selected subjects from grade 4 until the end of secondary school. The purpose of the assessment was to compare teachers’ internal classroom marks with student results on the assessment. Teachers were supposed to be ranked based upon how closely their internal marks corresponded to students’ assessment results (see Chapter 3). The initial intent was that those who ranked highly would receive a financial bonus, while teachers at the bottom would lose some of their salary. However, this reward system was never implemented, and the assessment was abolished, largely on the grounds that it placed too much pressure on teachers and had a negative impact on teachers’ classroom activities.

Currently, North Macedonia is not administering a national assessment, but plans to introduce a new assessment for system monitoring soon. The MoES has established an independent group to develop the assessment, however final decisions such as the subjects and grades to be assessed had not been made at the time of the review team’s visit. According to the newest draft Law on Primary Education, currently under discussion, the assessment will be a sample-based national assessment, with no stakes for student progression or teachers. However, it is suggested that results will be used to rank and reward participating schools.

North Macedonia participates intermittently in international assessments

North Macedonia has participated in TIMSS (1999, 2003, 2011 and 2019), PIRLS (2001 and 2006) and PISA (2000, 2015 and 2018). The country has produced national analysis and reports on the results – most recently in 2016, which was developed by the NEC in collaboration with the World Bank. – but they have not been shared with the public. This kind of national analysis provides the opportunity to exploit the rich datasets that international assessments offer. The experience of administering international assessments has also helped build national expertise that the country can draw on as it develops its own national assessment.

However, the ministry could make greater use of results by communicating them more widely and using them for national goal setting to help galvanise change. It will also be important to ensure more consistent participation to ensure reliable trend data.

Evaluation and thematic reports

There is no annual report on the education system

The MoES does not publish regular reports about the education system. However, the SSO has recently started to release statistical education information at the beginning and end of academic years (State Statistical Office, 2017[19]; State Statistical Office, 2017[20]). On occasion, the MoES also sends data to the SSO for reporting. For example, in 2016 the SSO has published an ad hoc report about the condition of schools in the country (State Statistical Office, 2016[21]). However, the SSO reports do not provide disaggregated data, for example by students’ ethnicity.

Some information from school evaluation is made available for system evaluation

The SEI produces annually a “Report on the quality of the education process in schools” that aggregates information from all integral evaluations (State Education Inspectorate, 2017[22]). This report identifies general trends gathered through school external evaluations, such as what common school needs are and the state of facilities, but the report does not focus strongly on student learning or system-level factors (e.g. what might be associated with common challenges). The review team was told that this report is rarely made public.

As part of integral school evaluations, satisfaction and perception surveys are administered to the students, parents, teachers and support staff. However, the data are not entered into EMIS and thus cannot be accessed by individuals outside of SEI. Consequently, these data, which contain valuable information about the conditions of schools and the attitudes of students and parents, cannot be used for system evaluation purposes.

Donors and non-governmental organisations have undertaken valuable analysis

Donors and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have, on occasion, provided valuable analysis that has contributed to system evaluation. For example, in 2016 Step-by-Step, an NGO undertook the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) and Early Grade Mathematics Assessment (EGMA) in grades 2 and 3, providing reliable information about learning outcomes in the early grades (see Chapter 1). In 2015, the World Bank undertook analysis of North Macedonia’s PISA data, as part of a regional review. While the work of external actors can provide important insights, it can also direct national capacity away from national bodies and focus on priorities determined by external actors.

Evaluation institutions

North Macedonia does not have an agency dedicated to research and analysis of the entire education system. The Bureau of Education Development (BDE) has an explicit research role, but it does not have a mandate to conduct comprehensive system evaluation. The BDE also lacks access to the data that it would need to develop evidence-based policy recommendations as the NEC does not grant it direct access to its databases. The NEC has staff with research capacity, but they also serve other functions within the NEC and their research roles are primarily limited to responding to ad hoc requests for information. Within the ministry, there is limited analytical capacity to evaluate education information and exploit it for policy-making purposes. Notably there is currently no unit or staff dedicated to this purpose.

Outside government, there are no well-established national research organisations that study the education system. The ministry does establish periodic relationships with higher education institutions to analyse policy reforms. For example, as part of the on-going pilot of the new curriculum in grades 1-3, the ministry is working with higher education institutions to develop an evaluation tool. However, higher education institutions do not have a permanent relationship with the ministry to analyse data. It was reported to the review team that this is in part because of the difficulty in acquiring data from the ministry. The absence of research activity makes it difficult to ensure that education policy is informed by a strong evidence base.

There is little oversight of how municipalities use resources and no evaluation of how they set and achieve education goals

Municipal governments are responsible for allocating funds from the central government to schools and for overseeing the hiring of school staff. However, there are no systematic mechanisms for reviewing or auditing these activities. Little oversight of school funding at the municipal level means that it is not possible to ensure that resources are used efficiently. Despite their role in education delivery, municipal governments are not expected to set objectives or evaluate their performance.

Policy issues

The primary obstacle to developing system evaluation in North Macedonia is the absence of high quality data that is accessible from a unified source. This review strongly recommends that collecting and accessing education data be centralised around EMIS and that EMIS itself be further developed to meet the evaluation needs of the country. A second priority for the country is to design a national assessment system that collects information about student learning, which can then be stored in EMIS alongside student and school contextual data. Finally, with these components in place, the country can work towards institutionalising system evaluation such that research and analysis of education data become established practice and government officials rely on evidence to inform their policy making.

Policy Issue 5.1.. Centralising the use of EMIS and improve its capacity

As data are integral to system evaluation, the ministry must ensure that EMIS has the capacity to support all evaluation efforts. The regulations and processes around data collection and access also need to ensure that EMIS is the central, unified source for all education data and that relevant information can be extracted easily. Without greater functionality and a stronger mandate for EMIS, the country will not have the systems in place to study and improve its education system.

Recommendation 5.1.1. Formalise EMIS as the central source of data

EMIS has been operational since 2010 and contains data about students, teachers and school staff. However, despite holding this information, EMIS is not used by North Macedonian policy makers to its full extent. When the ministry’s Sectors of Primary and Secondary Education require data about the system for example, instead of retrieving the information from EMIS they contact schools directly to collect data themselves. Several departments within MoES engage in this type of data collection on a regular basis and compile their own databases, usually stored in spreadsheets, at the beginning of each academic year.

From the perspective of the schools, providing data to numerous requestors, often the same data, can be burdensome and detract from other responsibilities. Furthermore, multiple data collection endangers the quality of data as different data might be provided to different requestors. Especially in the absence of a national indicator framework, this situation might create confusion around what the “true” information is. To alleviate the repetitive data reporting requirements on schools and ensure consistent data collection, EMIS should be recognised and used as the primary source of education data. Secondary data collection should be discontinued and those requestors should instead look to EMIS for their education data needs.

Raise the prominence of EMIS by positioning it closer to central leadership

Administration of EMIS is currently the responsibility of a small team of two individuals in the Department of Informatics in the ministry. These individuals are not involved in the policy-making processes or in systems to regularly report and monitor education data. That EMIS does not have a prominent role within the organisational structure of the ministry likely contributes to its under-utilisation by policy makers and other actors.

The ministry should consider making EMIS more prominent by moving it to the research unit that this review recommends North Macedonia establish (see Recommendation 5.3.1). A stronger institutional position for EMIS would give it greater authority to mandate who can collect data from schools and deter ministry staff from its bypassing rules. Furthermore, the director of EMIS, or the director of the agency responsible for EMIS, should be involved in policy-making processes, which would help solidify the relationship between data and its use in policy making.

Improve staff capacity

A staff of two individuals is likely insufficient to manage a fully functioning EMIS and does not convey a position of organisational significance. In Georgia, for example, EMIS employs five statisticians solely for responding to data and research requests, in addition to department leadership, administrative support and software developers who manage the system. In Fiji, a far less developed country, EMIS employs eight full-time staff and two part-time staff who are responsible for producing training materials and procedural manuals (World Bank, 2017[23]). North Macedonia’s EMIS would be well served by employing additional staff who could help the current two individuals develop the system, respond to data analysis requests and systematise rules and procedures.

Specific capacities that would have to be recruited or developed include software development for maintaining and improving EMIS and quantitative analysis skills for processing data and creating thematic reports. EMIS would also be well served by having permanent leadership that liaises between EMIS and other departments and agencies within ministry. Having more and better-trained staff work in EMIS would help communicate the message that EMIS is an important entity that should be used properly and relied upon.

Establish protocols for data definition, collection and retrieval from schools

Many countries have established strict protocols regarding the definition of data points and who can retrieve data from schools. In the United States, for instance, each state has developed and oversees its own education database and schools are required to enter information directly into this database. To ensure consistency for national-level reporting and analysis, the United States Department of Education has created the Common Education Data Standards that defines education data around the country (Department of Education, n.d.[24]). By implementing common data standards, national education policy makers can be confident that data from different states have the same meaning and can be relied upon to inform federal decision making.

In addition to commonly defining data, the United States also regulates who can collect data from schools. For example, if government parties wish to contact schools to collect information, they must undergo a rigorous screening process that is regulated by data sharing legislation (US Department of Education, 2018[25]). These procedures help restrict outside access to school information, funnel data retrieval to the education database and limit direct collection from schools to data that cannot be found in the education database (e.g. interviews with teachers or students).

In North Macedonia, such data definition and collection protocols have not been created. The result is that schools might have different definitions for indicators or data points (e.g. how student identification numbers are created). They are also forced to exercise discretion about to whom they provide information. While schools could deny third party requests, if a government body contacts a school for information, school leaders might not feel they have the mandate to refuse, though the data they supply might not even match a common definition. A formal data dictionary and sharing protocol would provide schools with guidance on how to define data and give them the mandate to reject external requests, thus encouraging the requestors to turn to EMIS for their desired information. Ensuring that data definitions are consistent with international definitions would help to fill the gaps in North Macedonia’s internationally reported data.

Standardise the collection of data across agencies and link those data to EMIS

Storing different types of data in different places, as is the case in North Macedonia between EMIS and the NEC, without a common linkage also presents problems. While some countries do hold data in different locations, these data are easily linked by a common variable, usually unique identifications numbers for students, teachers and schools (Abdul-Hamid, 2017[26]). This allows for seamless integration and analysis of data across several sources, such as student demographic information vis-à-vis their assessment results. In North Macedonia, such integration is currently not possible because not only are student’s demographic data stored in EMIS while test results are stored in NEC, but student identification numbers are not consistent across the systems. In-depth analysis using these two valuable sources of data, therefore, is also not possible.

Most EMIS systems do not create student identifiers, but instead use the students’ national/civil identification numbers (Abdul-Hamid, 2014[11]). Using this identification has several advantages. It is inherently standardised and therefore will follow a standard structure across all education databases. Moreover, because it exists at the national level, it can be used to conduct research across different sectors (e.g. if one wishes to study education outcomes and labour market success). Finally, by using this identifier, much student information can be retrieved automatically into EMIS by linking EMIS with the national registry, which greatly improves data quality and reduces the data entry burden on schools. Box 5.1 describes how EMIS in Georgia identifies students, regulates data entry procedures and makes data accessible.

Data collection in North Macedonia exists across several databases. In addition to EMIS, the NEC collects data from the state matura and SEI inspectors use forms to collect information during integral evaluations. These systems, however, are not interoperable. The unique identification of each student in EMIS is their national/civil identification number, but NEC’s database identifies students differently. SEI inspection forms are currently organised and filed, but their data are not always entered into a digital format. When they are, the data are stored locally at the SEI. Data from these different systems, therefore, cannot be easily retrieved or analysed in conjunction with each other.

Standardising government data collection would allow for greater interoperability between databases. Two key actions to enable this will be to use the students’ national identification in all databases, perhaps by passing a regulation, and to ensure that all data are digitised.

Georgia’s EMIS was created in 2012 with significant financial investment. Currently, two data centres store all data related to education in Georgia. The main databases themselves are administered internally by EMIS staff. All students are identified using their civil identification numbers and their personal demographic information is automatically populated in EMIS from the national civil registry. Examinations data are collected and stored separately at the office of the National Assessment and Examinations Centre, but these two databases are linked through the students’ identifiers.

Data entry is conducted directly by schools. School staff were trained by EMIS staff in how to enter data properly. EMIS staff have also created monitoring procedures that are used to perform quality checks on the data. The parties responsible for conducting these checks are education resource centres that are located throughout the country and have close relationships with the schools themselves. Within the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science and Sport, EMIS has established data sharing agreements with other departments and agencies, who must abide by the agreements in order to access EMIS data. Through these agreements, schools are protected from having to respond to unauthorised data requests because the data sharing agreements expect requestors to access data directly through EMIS.

Two front-end portals allow users to interact with information stored in EMIS. E-School provides immediate access to data about students, teachers and schools according to an individual’s user level (e.g. a principal can only view his/her school while ministry staff can view more). Another portal, E-Flow, operates as the primary mode of communications for all staff affiliated with the ministry. When sending a message through E-Flow, users can immediately see the school affiliation of recipients and information about their schools.

Sources: (Ministry of Education/UNICEF, 2015[27]), Country Background Report: Georgia, and OECD review team interviews in Georgia.

Establish quality assurance procedures to verify the accuracy of data that is entered

Internationally, countries implement strict data validation and auditing procedures to ensure that data are of the highest quality (Abdul-Hamid, 2014[11]). In North Macedonia, these types of quality assurance procedures are not fully developed. While ad hoc validation, such as validating student identification numbers has occurred, these mechanisms have not been systematised.

Creating regular quality assurance procedures for EMIS data would help to verify its accuracy and encourage more individuals to use the system. Such procedures could include visiting a sample of schools to check if independent data collection aligns with the school’s data collection, and if the school’s data collection aligns with the information they input into EMIS (Mclaughlin et al., 2017[28]). These procedures would not only improve the data found in EMIS, but also increase the level of trust in EMIS. This role should be undertaken by a national or central government body. One option would be for the State Audit Office to take on this role. In the past, the national audit body conducted a performance audit of EMIS, however there are questions on whether it has the capacity and resources to do so on a regular basis. Another would be to create a small team within the SEI, separate from school inspections, with a specific mandate for quality assurance of EMIS data.

Recommendation 5.1.2. Enhance the functionality of EMIS

One reason why EMIS is not used more widely is that its functionality is limited to data entry and storage. Effective EMIS systems also have strong analysis and reporting functionalities that can aid research and inform policy making (Villanueva, 2003[29]). These features should be available to all interested parties, and not just the small number of users who currently have accounts. Without this critical functionality, EMIS cannot be used to its full capacity.

Create regular reporting procedures

Reporting is one of the integral features of an EMIS. It is the vehicle through which the system transforms from being a receptacle of data to a provider of information. All EMIS systems have the inherent capability to generate reports using their stored data. It is the responsibility of administrators, however, to instruct EMIS how to process raw data, create reporting templates that display processed data and regularise reporting procedures (Abdul-Hamid, 2014[11]).

In North Macedonia, EMIS administrators have created some data processing instructions and reporting templates. However, they have not created regular reporting procedures, such as an annual statistical report at the end of each school or calendar year. Instead, EMIS reporting occurs in an ad hoc manner, mainly in response to individual requests. This system can be inefficient as requests for information tend to be submitted at similar times (around reporting deadlines) and thus require time to fulfil. This also limits the use of information, since it requires that users know what data are contained in EMIS and take the initiative to request it.

It would be helpful if EMIS administrators identified the most commonly used templates (e.g. data related to participation and completion), created a timetable for regular production of the reports and made those reports publically available. Interested parties can then retrieve the data instantly without needing to request the information from EMIS. After the most commonly used templates start to be reported regularly, EMIS staff can then turn their attention to producing regular reports on specific themes of national interest, such as the education of linguistic minorities (see Recommendation 5.3.3). These procedures would further encourage policy makers to rely on EMIS as a data source and make fuller use of the data in setting goals and designing policy interventions.

Develop a user-friendly portal to quickly retrieve contextual data

In addition to regular reporting, real-time access to data through a web portal is a common method of extracting information from EMIS and presenting it in an accessible manner. At the most fundamental level, users will be able to learn how many students attend a school and how they perform on a national assessment. More sophisticated systems aid research and analysis by facilitating comparison across schools, aggregation at different levels (e.g. regional or national) and providing a set of data visualisation tools (Abdul-Hamid, Mintz and Saraogi, 2017[30]). Box 5.2 explains the functionality of the Florida’s PK-20 Education Information Portal, an online EMIS portal from the Florida Department of Education, United States.

In Florida, United States, the Florida’s PK-20 Education Information Portal provides access to public schools from kindergarten through grade 12, public colleges and universities, a statewide vocational and training program and career and adult education. Through an online interface, any individual can view data that are aggregated at school-, district- and state-levels. Comparisons can be made across different schools and districts.

The Florida’s PK-20 Education Information Portal is powerful in that it allows data to be organised not only to the level of governance, but also subject matter. Florida’s state assessments test students in English, mathematics and science, with further delineation of different mathematics and science domains. Users who navigate the portal can choose to view all data according to a single domain (instead of viewing all data according to a single school) and make further contextualised comparisons according to the domain. This saves users from having to navigate to through different schools or districts in order to find the same indicator for each one of those entities.

Along with providing access to data, the portal provides simple tools for users to perform their own analysis. Users can, for example, format the data into tables that they define themselves (some standard tables are already provided). Custom reports that contain several tables can then be generated according to users’ specifications. The portal also has a strong data visualisation component. Different types of graphs and charts can be created based on the data. District-level analysis can even be plotted as maps that display indicators according to the geographic location of the districts within the state.

Source: (FL Department of Education, n.d.[31]), Florida Department of Education – PK-20 Education Information Portal, https://edstats.fldoe.org/SASPortal/main.do (accessed on 12 July 2018).

In North Macedonia, the e-dnvenik service was created to allow teachers, parents and students to view, through an online portal, relevant data that is stored in EMIS in addition to student grades. However, e-dnevnik is primarily used as a student monitoring service, not to access EMIS data for broader, analytic purposes. Users of e-dnevnik cannot, for instance, look at schools across the country and filter those schools by certain characteristics. Furthermore, access to e-dnevnik is limited to individuals with direct interaction in the education system, such as parents of students and school staff. Research organisations or higher education institutions cannot access e-dnevnik.

The ministry should create an online platform that allows public access to EMIS data through a dashboard interface. All users of the platform would be able to browse national education data and select schools and municipalities for comparison based upon chosen criteria (for example, location or language of instruction). The platform should also contain features to create dynamically generated charts and figures and export data for further analysis. Importantly, the online platform must be user-friendly such that members of the public can easily navigate it and use these features. Creating such a platform would help schools benchmark their performance in a contextualised manner, assist researchers in analysing system information and help policy makers base their decisions on stronger evidence.

Recommendation 5.1.3. Improve the articulation of national education goals and align future EMIS development with them

In North Macedonia, national education goals could be more clearly expressed and accompanied by clear targets. The Comprehensive Education Strategy 2018-25 lists some national objectives in terms of activities to be undertaken, but these are difficult to distil into a small number of high priority goals. Furthermore, the wording of the objectives is not specific enough, making measurement difficult. An EMIS system is designed to support the monitoring of national goals through the collection and reporting of data. Without measurable goals, however, EMIS cannot accomplish this task and the country cannot achieve accountability for education outcomes and the system. The lack of clear goals with measureable objectives also risks policy misalignment and unco-ordinated policy initiatives, reducing the impact of reforms.

Clarify national goals and create measureable targets

The Comprehensive Education Strategy 2018-25 is focused on achieving outputs, such as curriculum reform and textbook usage. It does not however focus on outcomes, notably improvement in student learning. Internationally, countries use national goals and targets to give visibility to national priorities and direct the education system towards their achievement. Given the evidence that the majority of students in North Macedonia do not master basic competencies, setting an ambitious target to raise learning outcomes would help to ensure that the education system and society in general, recognises this as a national and urgent priority.

This chapter strongly recommends that the government establish specific goals for improving student achievement and associates those goals with measurable, achievable targets. Since the national assessment is still in development, using data from international assessments such as PISA to monitor student performance over time would be an effective method to track changes in student learning. For example, reducing the share of low performers in PISA to below 15% by 2020 in line with European Union (EU) targets (European Commission, 2018[32]). The government can also consider setting interim benchmarks to ensure that the country is progressing towards the long-term goal. Given the evidence of inequity in learning outcomes, such as the gap between rural and urban students, or between students of Macedonian, Albanian and other ethnicities, other goals to improve equity might also be included. For example, goals might be set to reduce the performance difference between different groups of students by 10 score points in all three core domains. North Macedonia could then use these targets to steer attention and accountability towards student learning.

To support the achievement of these student-learning goals, the ministry will need to make sure that it develops clear plans that set out how its goals will be supported. Critically, this should include plans for establishing a new national assessment and prioritise consistent participation in international assessments to provide trend data.

Develop a national indicator framework and use it to co-ordinate data collection and reporting procedures

The absence of a national indicator framework is inhibiting systematic data collection, reporting and monitoring of student outcomes in North Macedonia. A national indicator framework not only specifies the measurable targets associated with goals, but also the data sources that will be used to measure progress and the frequency of reporting around the indicator. Without this valuable document, system evaluation in North Macedonia loses co-ordination around what data points to pay attention to, which results in a general loss of systematic direction and fragmented goal setting.

Developing an indicator framework would not only support accountability vis-à-vis national learning goals, but would also help orient the future development of EMIS. Through the national indicator framework, data gaps can be easily identified. If, for example, a target is to improve the retention of students from ethnic minority groups, the national indicator framework would indicate that EMIS is the data source to be used to monitor this indicator, and that it would need to collect data about students’ ethnicities. If EMIS currently does not hold such data, or if such data are poorly collected, EMIS staff would prioritise developing capacity and data collection procedures to support the monitoring of this indicator. Reporting against indicators from the framework in an education report would also support public accountability and create pressure to ensure that any data gaps are addressed.

Policy Issue 5.2.. Designing a national assessment that supports national learning goals

Currently, there is no national assessment administered in North Macedonia. In the past, the country has used national assessments to monitor learning outcomes, from 2001 to 2006, and more contentiously for teacher accountability, from 2013 to 2017. Using national assessment results for teacher accountability is very difficult to do fairly and accurately because students’ learning outcomes are influenced by a range of factors beyond an individual teacher’s control (such as previous learning, home environment, motivation, ability, etc.) (OECD, 2013[2]). As a result, very few OECD countries use national assessment results for individual teacher accountability.

In North Macedonia, a well-designed, national assessment would provide valuable information to monitor student performance at key stages of their education against national goals (see Recommendation 5.1.3). The results can also be used to inform policies and future system planning and help to improve the quality of teachers’ professional judgement at the classroom level as well. The extent to which the assessment might be used for school accountability, another common use of national assessment data in OECD countries, is currently under discussion in North Macedonia. This review provides suggestions of how school-level outcome data can be employed to support constructive reflection on school quality, while avoiding the high stakes that might undermine effective teaching and learning practices and have a negative impact on teacher and school behaviour.

Recommendation 5.2.1. Determine the purpose of the national assessment and align its design to the purpose

According to the draft Law on Primary Education, the purpose of the new national assessment in North Macedonia is to assess the quality of education and the results are to be used by schools in their development plans. The Law also foresees using the assessment results to rank participating schools according to student performance (Recommendation 5.2.2). The government might also consider whether the national assessment should provide formative feedback, so that teachers can better tailor teaching and learning to student needs. The purpose that is decided for the assessment will closely impact its design and implementation. The following section discusses the key decisions that North Macedonia is facing as it develops its national assessment.

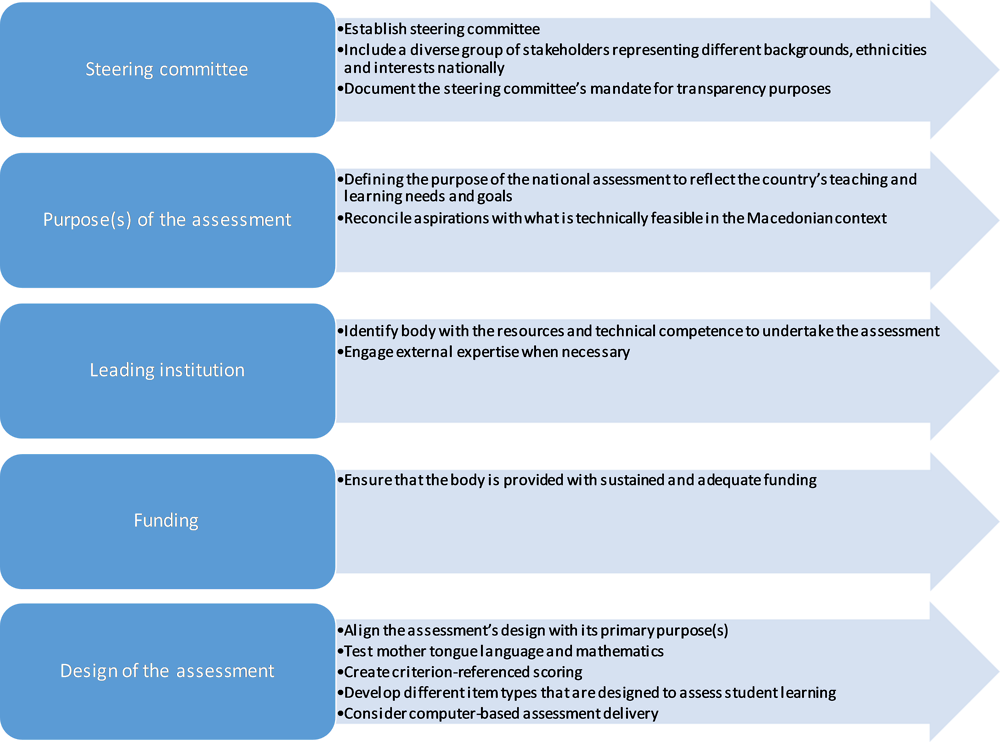

Establish a steering committee to define the purpose of the assessment

Carefully defining the purpose of the national assessment to reflect the country’s teaching and learning needs is critical. It will also be important that the MoES take steps to achieve systemic buy-in, so that the results are trusted and used. Towards this end, this review recommends establishing a steering committee comprising a diverse group of stakeholders representing different backgrounds, ethnicities and interests nationally. This should include, for example, representatives from the Vocational Education and Training Centre (VETC). The steering group should also include technical expertise on the development and use of national assessments.

The steering committee will need to take into account not only the goals of the education community, but those of the political administration and reconcile these aspirations with what is technically feasible in the North Macedonian context. International experts can be enlisted to lend a global perspective to the steering committee’s deliberations.

The MoES has recently created an independent group to review Slovenian’s National Assessment of Knowledge (NAK), with a view to incorporating elements into North Macedonia’s national assessment (see Box 5.3). If practical, the steering committee can be formed by building upon the membership of this group. However, it will be important that the mandate of the current group be clearly documented and that transparency around its activities increased, if it is to become an official steering committee that guides the development of the national assessment. During the OECD review visit, many important stakeholders remained unclear as to the purpose of group, creating some concern and potential mistrust in the process.

To inform the development of its new national assessment, North Macedonia is currently studying the Slovenian example. The official objective of the National Assessment of Knowledge (NAK) is to improve the quality of teaching and learning in Slovenia. As such, the NAK is low-stakes and does not affect students’ marks or their progression into higher levels of education. A notable exception to this regulation is that student results can be used to determine secondary school enrolment if spaces are limited at certain schools.

As of 2006, the NAK is administered annually to students in grade 6 and grade 9. Students in grade 6 take mother tongue, mathematics and a foreign language, while students in grade 9 take mother tongue, mathematics and a subject selected by the minister from a pre-defined list. The Slovenian National Examinations Centre is responsible, through various committees, for creating the guidelines, items and materials of the assessment. A separate organisation, the National Education Institute, is responsible for creating the marking procedures, training the markers and performing research and analysis using the results.

Results from the NAK are reported at the student-, school- and national-levels. Students receive an individual report that can be accessed electronically. The report identifies the student’s performance in terms of how many questions were answered correctly, the percentage of questions that were answered correctly and classifies students into one of the four proficiency levels. Students’ results are compared to his/her school average and the national average. Item-level analysis, showing how the student performed on different types of questions, is also provided.

Schools receive a report that shows the average performance of the students in their school compared to regional and national averages. At the national level, a report that summarises the results of the country is produced every year. The results are disaggregated by grade, subject, gender and region. All annual reports are published on line. National surveys reveal that over 90% of head teachers consider their students’ national assessment results in their future work, and over 80% of all teachers believe that the assessment results give them useful information about their work.

The review team believes that the regularity, grade levels and subjects assessed by Slovenia’s national assessment would transfer well to the North Macedonian environment. Furthermore, Slovenian reporting procedures around its national assessment are comprehensive and the review team supports efforts to adopt a similar reporting scheme in North Macedonia. However, the use of the assessment as a criteria for selection into secondary school, even in limited circumstances, would not be advised in the North Macedonian context given the aforementioned need to separate the national assessment from student consequences.

Sources: (Eurydice, n.d.[33]), Assessment in Single Structure Education – Slovenia, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/assessment-single-structure-education-35_en (accessed on 10 January 2018); (Brejc, Sardoc and Zupanc, 2011[34]), OECD Review on Evaluation and Assessment Frameworks for Improving School Outcomes: Country Background Report Slovenia, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/48853911.pdf, (RIC, n.d.[35]), Državni Izpitni Center (RIC), [National Examinations Centre], https://www.ric.si/ (accessed on 13 November 2018).

Determine who will be responsible for the national assessment

One of the first decisions for the steering committee is who will be responsible for the national assessment. In the past, responsibility for national assessments has moved between the BDE and the NEC. Above all, it is important that the responsible organisation has the technical competence and resources to undertake the assessment.

This review recommends that, as the NEC has experience in administering the matura and international assessments, it is best positioned to be responsible for the new national assessment. It already has test administration, marking infrastructure and staff who are familiar with these processes. In order to take on this new task, the NEC will need sustained and adequate funding. In the short term, this may require drawing on an external source. One possible source discussed with the review team is the European Commission. This could provide essential support for the assessment’s design and development in the early stages. However, it will be important that North Macedonia plans for the assessment’s sustainability well before such external funding ends.

Consider making formative feedback to educators the primary function of the assessment

This review recommends that North Macedonia’s national assessment serve primarily a formative function. In other words, it should provide detailed information on how students are performing vis-à-vis the nation’s learning standards and this information should be used by the education system to improve student learning.

Using the national assessment in this way would help to address key teaching and learning challenges in North Macedonia. International data suggests that national outcomes are low and not improving (see Chapter 1). The review team’s interviews suggested that teachers’ classroom assessments are not always an accurate indication of what students know and can do, which is essential to improve learning (see Chapter 2).

At the same time, North Macedonia is progressively implementing a more competency-based curriculum. International experience shows that teachers require significant guidance to adapt teaching to this approach, so that students are assessed in ways that are valid and reliable according to new benchmarks for learning. In this context, the country will require meaningful assessment results about student learning that can help teachers better understand where students are in their learning and tailor teaching to students’ individual needs.

If the ministry decides to use the assessment for primarily formative purposes, care will need to be taken in terms of how results are used for accountability purposes. While all national assessments provide a broad accountability function for the education system overall – by monitoring learning outcomes nationally against standardised expectations –using results for accountability purposes at the level of individual schools and teachers can encourage schools and teachers to attach stakes to an assessment. This can result in distortive practices like teaching to the test, which involves disproportionally focusing on assessed content or repeated assessment practice (OECD, 2013[2]). Such stakes would also undermine the assessment’s formative purpose that this review recommends. The education system in North Macedonia is even more vulnerable to these tensions, given the recent practice of using the national assessment for teacher accountability. Careful steps will need to be taken to avoid that the assessment is perceived to carry high stakes (Recommendation 5.2.2).

Align the assessment’s design with its primary purpose(s)

Once North Macedonia has agreed on the assessment’s primary purpose(s), this should guide subsequent decisions on key aspects of the assessment’s design. Table 5.2 illustrates several components about national assessments that will need to be decided upon. The suggestions in the discussion below are intended to support a prominent formative function.

Combine census and sample-based testing

National assessments can be census-based, in which all students from the population of interest are tested, or sample-based, in which a representative sample of the population is assessed. A census-based design yields more accurate results, can be used for monitoring individual students and can be aggregated into higher-level results, such as school and municipality. Given concerns around teaching and learning in North Macedonia, a census assessment would be particularly valuable since it could provide formative information to help all teachers adapt instruction to their students’ needs.

However, census assessments can easily acquire high stakes, and this risk needs to be addressed. Census assessments are also considerably more expensive to implement and require more time to ensure that all students are tested and all tests are marked. To manage these costs in the immediate to medium term, North Macedonia might consider implementing a hybrid model in which both census- and sample-based testing designs are used in different grades. This review recommends the following configuration:

-

Census assessments in grades 3 and 6

Currently, there is no standardised measure of performance in the early grades of school. Having more information about student learning and school performance at this level would allow for the identification of struggling schools and students, and the provision of more relevant support to them. An assessment at this stage is important since children who do not master basic competencies, like reading in early grades, are more likely to struggle later on (National Research Council, 2015[37]). At the same time, support to address difficulties or learning needs is more effective the earlier it begins. These considerations are especially important in North Macedonia, given the evidence from EGMA and EGRA that suggests that younger students lack essential literacy and numeracy competencies.

Once the new curriculum is piloted for grades 1 through 3, the MoES could use student performance data at the end of grade 3 to help decide whether, and how, to expand the adoption of the new curriculum. Grades 3 and 6 are also the end of the first and second curriculum cycles, so the assessments would provide information about student performance at key stages.

-

Sample assessment in grade 9

Grade 9 represents the end of the third curriculum cycle and would be a logical point to re-administer the national assessment. Since grade 9 also marks the transition to high school, to avoid confusing the national assessment with an entry examination (which North Macedonia had in the past), this review recommends that the national assessment be administered in grade 9 as a sample.

As a sample-based assessment is quicker and cheaper to administer, it can also be used for experimental and research purposes. For instance, the MoES could introduce new domains into the grade 9 assessment in order to assess student performance in subjects outside those that appear in the grade 3 and 6 assessments. Sample-based assessments do not provide sufficient information on each school to provide statistically robust and reliable school-level results that are comparable.

Recording student results using the student identity document (ID) would make it possible to link the assessment results to students’ background data in EMIS (such as their mother tongue language, gender, etc.). This would enable initial analysis of how contextual factors impact student-learning outcomes. In the future, once the national assessment is well developed, North Macedonia might consider developing background questionnaires in order to enable further analysis of the contextual factors shaping learning.

Test mother tongue language and mathematics

Among OECD countries with national assessments at the primary level, a third (ten) assess just mathematics, and reading and writing in the national language, which represent core skills (OECD, 2015[12]). Focusing on these two subjects in the assessments at the primary level (grades 3 and 6) would be especially constructive in North Macedonia given the EGRA and EGMA results.

In grade 9 and even perhaps grade 6, additional subjects, e.g. science and/or national history, may be added to the core of language and mathematics. For students whose first language is not Macedonian, Macedonian as a second language could be added given the equity concerns with respect to outcomes by ethnicity (see Chapter 1).

Create criterion-referenced scoring

The vast majority of OECD countries with national assessments use criterion-referenced scoring. For example, among 27 countries with a national assessment in lower secondary, 21 reported using criterion-referenced tests (OECD, 2015[12]). A criterion-referenced test assesses the extent to which students have reached the goals of a set of standards or national curriculum, while a norm-referenced test compares students’ results to each other (OECD, 2011[38]).

Results from criterion-referenced tests are preferred for national assessments because they produce results that are comparable over time. As the purpose of North Macedonia’s national assessment is to understand what students are learning linked to national learning expectations and to monitor progress over time, the assessment should be created as a criterion-referenced test. North Macedonia’s national learning standards represent natural reference points for the assessment.

Develop different item types that are designed to assess student learning

In OECD countries, the most popular types of items that appear on national assessments are multiple-choice responses and closed-format, short answer questions (e.g. true/false, selecting a word of providing a solution to a mathematics problem) (OECD, 2013[2]). These item types are the most common because they are easier and quicker to develop and administer. Moreover, their marking and scoring is more reliable, and therefore test results are more comparable (Hamilton and Koretz, 2002[39]; Anderson and Morgan, 2008[40]). Less frequently used item types include open-ended questions, performing a task, oral questions and oral presentations. Though less common, these types of items are increasing in use due to their ability to assess a broader and more transversal set of skills than closed-ended items (Hamilton and Koretz, 2002[39]).

In interviews with education stakeholders, the review team learnt that one of the primary concerns with the national assessment conducted between 2013 and 2017 was that the questions encouraged memorisation. Therefore, a key consideration for the new national assessment is to ensure that concerns about cost and reliability are balanced with the national need to assess learning in ways that do not encourage memorisation.

Given these trends and considerations, this review recommends that the:

-

Grades 3 and 6 assessments consist primarily of multiple-choice and closed-format responses. These are the most common types of questions among OECD countries with assessments at this level of education (OECD, 2015[12]). While there are natural limitations to multiple-choice and closed-format responses, these types of items, when developed well, do have the capacity to assess complex student learning (Anderson and Morgan, 2008[40]). The majority of questions from both PISA and TIMSS represent these two types. Care will need to be taken to ensure that these items are measuring student learning instead of memorisation, and that proper item-writing convention is followed, such as reviewing items for potential bias and varying the placement of distractor choices (Anderson and Morgan, 2008[40]). In grade 3, North Macedonia can also draw on international models for assessing literacy and mathematics in the early grades of school, such as EGRA and EGMA.

-

Grade 9 assessment includes multiple-choice questions, closed-format responses and can begin to incorporate more open-format questions. At this age, students are more capable of responding at length, and the sample-based nature of this test produces fewer responses to mark, thus limiting the added costs that these items would create.

Consider computer-based assessment delivery

In most OECD countries, the delivery of the national assessment is through a paper-and-pencil format. Nevertheless, this trend is changing and computer-based administration is becoming more common, particularly in countries that introduced a national assessment relatively recently (OECD, 2013[2]).

Compared to paper-based delivery, computer-based testing has several advantages. It tends to be cheaper to administer (aside from the initial capital investment), less prone to human error in the administrative procedures and the results are delivered more quickly. Given these advantages, and because the ministry in North Macedonia is already dedicated to enhancing the use of technology in education, this review recommends that the national assessment be delivered as computer-based assessments. Importantly, given the intent of the assessment to provide meaningful, formative information to teachers and schools, the faster speed with which results can be delivered through a computer-based test would certainly support this aim.

Recommendation 5.2.2. Pay careful attention to the dissemination and use of national assessment results to enhance their formative value

How the results of the national assessment are reported is critical to achieving the purpose of the assessment. According to the draft Law for Primary Education, schools are to be ranked according to their students’ results on the assessment. Such a measure, however, would make teachers and schools fearful that the assessment be used for disciplinary purposes and discourage them from embracing it as a tool for learning. Therefore, North Macedonia should abstain from using the test results for ranking schools and ensure that the reports generated from the national assessment contain detailed information that is to be used to improve student learning.

Avoid decontextualised ranking of individual schools and any judgements on individual teachers

Research shows that concentrating excessively on numerical ranks with respect to students, teachers and schools can have negative consequences on teaching and learning. Especially when coupled with punitive consequences, such a system encourages educators to focus on reporting high marks as opposed to focusing on student progress (Harlen and James, 1997[41]) (OECD, 2013[2]).

The ministry’s intent to hold schools accountable for their assessment results is positive in some respects, since it reflects a desire to encourage schools to focus more on the quality of the teaching and learning environment they provide. Nevertheless, in North Macedonia the history of using assessment data to penalise teachers and principals is fresh in the memory of the education community. Furthermore, international evidence shows that student learning outcomes are influenced by a range of factors that are beyond the control of the individual school or teacher, the most influential of which is a student’s socio-economic background (OECD, 2013[2]). Ranking schools by assessment results alone risks that schools with the greatest concentration of students from more advantaged backgrounds are continually being ranked at the top.

Based on the body of international evidence and the education environment in North Macedonia, this review recommends that schools are not ranked according to their results on the national assessment or any other decontextualised criteria. Such a measure would not provide an accurate judgement of quality or educationally valuable information and would undermine the assessment’s formative function. Instead, information about schools can be presented according to several educational indicators (see Box 5.4). These might include a school’s results on the national assessment, the socio-economic status of a school’s students and their linguistic background. Using this information, the ministry could even publicly recognise schools whose students are performing well in the face of difficult circumstances. Given the recent experience of national assessments, it will be important to communicate clearly that the new assessment will not be used to form a judgement on individual teachers and it will not carry any consequences for them.

Sweden

In Sweden, an online portal, with data from the SIRIS (Swedish abbreviation for a database called “Information System on Results and Quality” [Skolverkets Internetbaserade Resultat- och kvalitetsInformations System]) and SALSA (Swedish abbreviation for a database called “Local Relationship Analysis Tool” [Skolverkets Arbetsverktyg för Lokala Sambands Analyser]), operated by the National Agency for Education provides contextualised data on student and school performance. Along with results from grade 9 national tests and upper-secondary course examinations, SIRIS provides basic statistical figures of schools, such as numbers of students and teachers, student-teacher ratios, teacher qualification levels and spending, as well as figures on grades and promotion, such as the number of students achieving the basic level and eligible for admission into upper secondary schools.

SALSA, a statistical model, provides performance data on specific schools and municipalities through the calculation of an “expected value” of the proportion of pupils who have passed the minimum level in 9th grade. This is displayed alongside the actual value and allows for an estimate of the value added performance for a given municipality or school with data from grade 9. SALSA uses and displays certain background information utilised in the calculation of the “expected value”: parents’ level of education, the percentage of students who are boys and the percentage with foreign background.

Australia

In December 2008, all Australian Education Ministers committed to a variety of goals and actions under the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young. In the area of national public reporting, the Declaration noted the need to provide information on the performance of schools, as well as information regarding a school’s enrolment profile and contextual information. The Declaration sought to ensure that public reporting would focus on improving performance and student outcomes, be locally and nationally relevant and be timely, consistent and comparable.

The Declaration was followed by the release of protocols and eight guiding principles on the use of data and reporting. The protocols are designed to promote meaningful and comparable reporting across Australia and to provide safeguards against simplistic comparisons being made among schools, in particular by providing contextual information. The principles underscore, among other aspects of quality reporting, the need for using data that is valid, reliable and contextualised, including school and student outcome and performance data.