6. Investment promotion and facilitation

This chapter reviews investment promotion and facilitation policy in Bulgaria. It provides an overview of the overall institutional and regulatory framework, relevant strategic documents, available investment incentives and the role of EU funds in mobilising investment. It also analyses the activities of the national investment promotion agency, InvestBulgaria Agency, benchmarking them to the agencies of OECD countries. Finally, it discusses the progress made in facilitating investment and reducing administrative burdens.

As highlighted in the OECD Policy Framework for Investment (OECD, 2015a), investment promotion and facilitation – if adequately designed and implemented – can be powerful means to attract investment and ensure its contribution to economic development. As such, countries worldwide decide to not only remove restrictions on foreign direct investment and provide high standards of protection to investors, but also to proactively promote and facilitate investment, or certain types of investment, to maximise the benefits to the host economy. Considering that Bulgaria has removed most formal barriers to FDI, and is subject to the EU’s regulatory acquis, it can benefit from active and well-designed investment promotion and facilitation policies to help attract and retain investment that can assist its transition towards more innovation, diversification and high-quality employment.

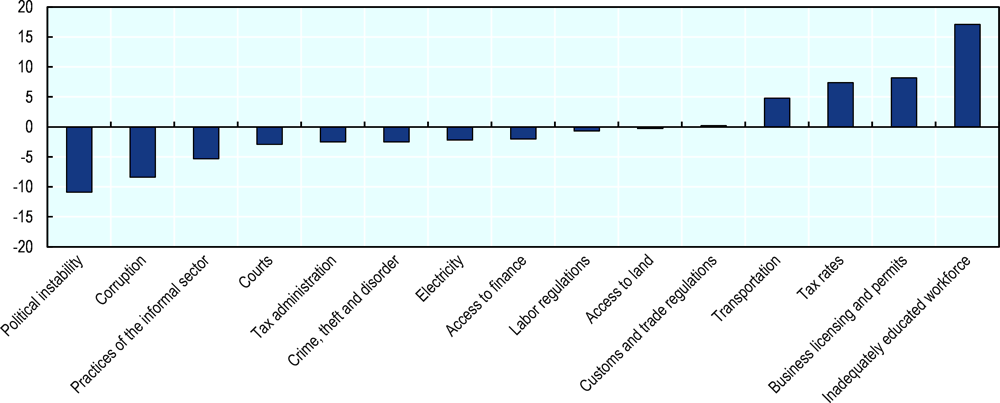

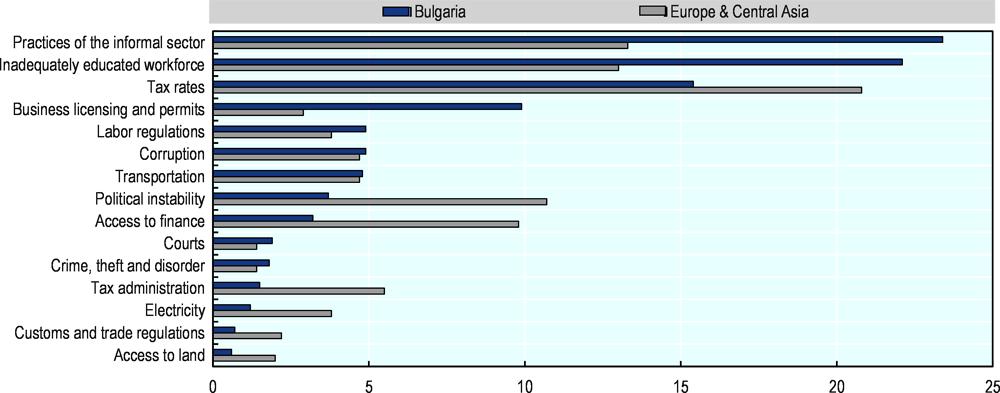

Bulgaria has made progress in improving its overall investment climate, as reflected in the existing business surveys and reports by international organisations. For example, the share of firms reporting political instability and corruption as a key barrier to firms diminished by nearly 10 percentage points in the World Bank’s Enterprise Survey between 2013 and 2019 prior to political crises that Bulgaria faced throughout 2021 and new political crisis in the aftermath of the Government’s lost of confidence vote in June 2022 (Figure 6.1). Still, firms identify certain policy areas as continuously important obstacles (Figure 6.2), such as the competition from the informal sector. According to EBRD BEEPS survey, 60% of firms reported they have to compete against unregistered firms. In addition, importance of other factors has increased – notably, the availability of skilled workforce and business licensing and permits. This is consistent with the findings of the survey by the Bulgaria Industrial Association (BIA), which also pointed to a lack of skilled labour force and bureaucracy as major obstacles to firms in 2019.1

Addressing these various challenges will require a concerted effort on the part of the government, utilising various policy tools at its disposal. This Chapter provides an overview of Bulgaria’s recent efforts to improve business climate. It first outlines the legal and institutional framework for investment promotion and facilitation and describes the main policy tools in the area, such as the use of EU funds, investment incentives, industrial zones and SME-specific support programmes. It then reviews the activities of the national investment promotion agency (IPA), InvestBulgaria, benchmarking it relative to OECD IPAs. Finally, yet importantly, it analyses the progress made by Bulgaria in reducing administrative burdens and concludes with key policy recommendations.

Bulgaria has developed elements of a national strategy for FDI attraction

Over the years, Bulgaria has developed several framework documents that provide the overall vision for the country’s medium and long-term socio-economic development and set out key priorities, including in the area of investment policy (Box 6.1). They provide a framework within which the country’s investment promotion and facilitation policy intervenes and set the national goals that FDI attraction should support. They also shape the expectations of the private sector on the type of support that investors may expect and delineate the responsibilities of different institutions.

In particular, the Act on Investment Promotion (AIP) is the main legal document outlining the type of support provided by the government to investors. It specifies the conditions, applicable procedures and requirements for obtaining state support and outlines the responsibilities of different government bodies. It is primarily concerned with regulating investment incentives. This is a relatively common approach to investment promotion acts in transition economies that have recently become EU Member States and have undertaken active steps to comply with the EU state-aid rules.2

Several strategic documents provide an overall vision for the socio-economic development and the role of investment promotion and facilitation policy in Bulgaria:

The National Development Programme: Bulgaria 2020 has served as an umbrella document for the country’s socio-economic policies until 2020. In particular, Priority 5 explicitly targeted investment and innovation policy in Bulgaria, and proposed broad measures to improve domestic productive capacity, such as expanded investment incentives, industrial parks, proactive investment marketing and support for SMEs.

The National Development Programme BULGARIA 2030 is a strategic document that elaborates the overall vision for Bulgaria’s socio-economic development for the next decade in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. While it does not explicitly refer to the role of FDI in the national development, it outlines several priority areas that will have incidence on the quality of the overall business climate (e.g. institutional strengthening, developing transport and digital infrastructure and skills upgrading).

Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation 2014-20 outlined objectives for the country’s long-term economic development. For example, it identified key sectors with a potential for growth and upgrading of the country’s innovation capacity: mechatronics and clean technologies; ICT; biotechnology; nanotechnology; creative industries; pharma; and food industry. It also outlined an institutional framework for co-ordinating the implementation of the plan as well as indicators for monitoring progress. The plan’s implementation was supported with EU funds.

The Act on Investment Promotion (AIP) is the main document setting out the specific objectives of the national investment promotion policy in Bulgaria, delineating responsibilities of different bodies and outlining the criteria for government investment support. The main objectives stipulated in AIP are: 1) raising the competitive capacity of the economy through increase in investment in science, technology, innovation, and high value-added activities; 2) improvement of the investment climate and overcoming the regional socio-economic inequalities; 3) creating new and highly productive jobs. These goals are operationalised through a series of support measures outlined in AIP.

Several other laws and documents also include relevant elements. For example, the Law on Reduction of Administrative Burden and Administrative Control on Economic Activity (adopted in 2003 with subsequent amendments) outlines measures to reduce administrative obstacles. Several specific programmes have also aimed to support the development of SMEs and entrepreneurship such as the National Strategy for Promotion of SMEs 2014-20 and since then the National Strategy for Promotion of SMEs 2021-27, adopted in 2021.

Source: OECD based on information provided by Bulgarian authorities.

Yet, in order to start addressing the remaining obstacles to doing business in Bulgaria and ensure a co-ordinated whole-of-the-government approach, a more comprehensive approach to business climate reforms may be desirable. The government could hence consider whether it would not be beneficial to formulate a detailed action plan on the implementation of different priority business climate reforms with specific measures to be implemented, responsible authorities identified and timelines set. The plan should be more detailed than the 2015 Action Plan for Improving the Investment Environment, specifying concrete steps to be taken to address bottlenecks while being more comprehensive than the AIP. It could build on the existing analysis and projects, including those realised in the framework of co-operation with the EU, or be part of the next phase of national planning to avoid duplication. By including specific projects aimed at addressing remaining barriers, such an exercise could help operationalise the objective of improving the overall business climate. The plan could be made publically available to allow for tracing of progress achieved. If the government is seeking an inspiration in international good practice, it may be interested in the way that Uruguay – which adhered to the OECD Declaration on International Investment in 2021– integrated investment climate reforms in its national planning process.

The newly established Ministry of Innovation and Growth could clearly play a role in the process, being the principal institution responsible for investment policy since early 2022. For the projects involving other ministries or agencies outside of the Innovation and Growth Ministry’s responsibilities, support at the highest levels of government and the involvement of the inter-Ministerial co-ordination mechanisms that pre-existed to the creation of the Ministry of Innovation and Growth (see below) would be beneficial to ensure co-operation.

Bulgaria’s national strategy for FDI attraction could provide a basis for better cross-governmental co-ordination

In Bulgaria, as in other countries, several different institutions are involved in the elaboration and implementation of the investment promotion and facilitation policy (Box 6.2). Prior to the establishment of a new government in December 2021, and pursuant to the Act on Investment Promotion, the Ministry of Economy was in charge of the development of the national investment promotion policy, aided in implementation by InvestBulgaria Agency (IBA), at the national level, and by regional governors and mayors at the sub-national level.

In addition, several bodies aim to facilitate cross-institutional co-ordination. For example, under the previous administration, the Ministry of Economy had created a high-level permanent Taskforce (composed of Deputy Ministers and Secretary Generals) to co-ordinate support measures for investors. The National Economic Council (NEC), created in 20153, has been charged with developing and proposing regulations to encourage investment activity, increase the overall competitiveness, and organise and control the interaction between the executive authorities, other state bodies and business representatives. Meeting regularly, its decisions have been published on the websites of the Ministry of Economy and the Council of Ministers. Finally yet importantly, the National Council for Tripartite Co-operation, which consists of representatives of the Council of Ministers and representative organisations of employees and employers, can also play a relevant role in providing a platform for negotiation of certain reforms (see Chapter 8 on Responsible Business Conduct).4

As highlighted in the OECD Policy Framework for Investment (OECD, 2015a), the ability to co-ordinate effectively the various activities is critical for successful business climate reforms. As such, the government could consider seeking feedback from relevant stakeholders if they deem the current co-ordination mechanisms to be sufficient. The national planning (described above), with specific deliverables and joint projects identified for different institutions could also facilitate co-ordination. While NEC by its nature could be naturally placed to co-ordinate such horizontal efforts, its technical capacity and the Secretariat may need to be strengthened further to ensure tangible progress in implementing reforms.

Responsibilities of different bodies involved in the design and implementation of investment promotion policy in Bulgaria are outlined in the Act on Investment Promotion.

1. develops a strategy for promoting investment in co-operation with the executive authorities and interested NGOs, which is adopted by the Council of Ministers

2. develops and implements programmes and measures to encourage investment in co-operation with the executive authorities and interested NGOs

3. develops and proposes draft regulatory acts to encourage investment activity in the country

4. represents the country in international organisations in the field of investments

5. makes proposals for inclusion of the necessary funds to encourage investments in the State Budget Law for the respective year under items 7 and 8

6. makes proposals for inclusion in the operational programmes co-financed by the European Union funds of measures to encourage investment

7. issues a certificate for a given investment class and for a priority investment project and submit proposals to the Council of Ministers for the implementation of investment promotion measures under this law

8. submits to the Council of Ministers proposals for the conclusion of memoranda or agreements with investors

9. submits to the Council of Ministers proposals for the designation of industrial zones or technological parks with the necessary technical infrastructure to attract investment for national sites within the meaning of the State Property Act.

1. ensures the implementation of the state policy for promoting investments in the region;

2. develops measures to encourage investment (included in the regional development strategy) and co-ordinates their implementation in line with the strategy for investment promotion

3. co-ordinates the work of the executive bodies and their administrations on the territory of the region under items 1 and 2;

4. exercises control over the legality of the acts and actions of the bodies of local self-government and local administration.

1. ensures the implementation of the policy for encouraging investments on the territory of the municipality in the development and implementation of the municipal development plan and the programme for its implementation;

2. assists in the implementation of the investment promotion measures under this law;

3. issues a certificate for investment projects of municipal importance and apply the promotion measures within its competence.

The InvestBulgaria Agency has two main functions:

1. Supports investors by providing information; acts as a one-stop-shop for contacting different authorities during the investment process; and provides aftercare services;

2. Promotes Bulgaria as an attractive investment location through different marketing activities.

Source: Act on Investment Promotion and Bulgarian authorities (2021).

Bulgaria’s reliance on the provision of investment incentives

Bulgaria has a corporate income tax (CIT) rate of 10%, which is significantly below the OECD average (Figure 6.3). It can make the country an attractive location to certain investors. There are also different kinds of investment incentives available to locally established firms, both foreign and domestic, without differentiation by the origin of capital. As an EU Member State, Bulgaria is also subject to the EU State Aid rules.5

The legal framework for regulating investment incentives in Bulgaria is well developed. Fiscal incentives are consolidated in, and regulated by, the respective tax statutes, i.e. Value-Added Tax Act (VAT Act), the Corporate Income Tax Act (CITA), the Social Insurance Code and the Law on Income Tax of Physical Persons. They involve a reduction of and exceptions from CIT payments, accelerated tax depreciation or losses carry-forward; special arrangements for VAT payment; and tax relief concerning pension funds under the Social Insurance Code, among others (see Box 6.3 for an overview). Financial investment incentives are also available to firms in Bulgaria as regulated by the AIP and its implementing regulations.6

Overall, there are four types of certified investment projects in Bulgaria – Class A, Class B, Class C and priority investment projects – that can benefit from government support (see Box 6.4). They differ in terms of the eligibility criteria, which relate to the character of the economic activity, size of investment and job creation effect, among others, and the application process. As of November 2021, applications for Class A and B investment project certificates had to be submitted to InvestBulgaria and Class C to the mayor of the municipality where the project would be implemented. Both Class A and Class B certificates were issued by the Minister of Economy; certificates for investment projects with municipal importance (Class C) were issued by the mayor of the municipality. Priority investment project certificates were issued by a Council of Ministers’ Decision, which approved either a Memorandum of Understanding or an Agreement between the Government of Bulgaria and the investor.7

The Corporate Income Tax Act (CITA)

Besides the general corporate income tax of 10%, CITA includes several fiscal incentives:

Accelerated tax depreciation of machinery, production equipment and apparatuses which are part of the initial investment or have been acquired in connection with an investment made to increase energy efficiency (Art. 55(3) and (6)): The tax incentive consists in accelerated tax depreciation. The annual tax depreciation rate is up to 50% (in the general case the annual tax depreciation rate for these assets is 30%).

Accelerated tax depreciation (100% per annum) for assets formed as a result of research and development (R&D) activities (Art. 69).

Tax losses carry forward (Art. 70-74): The right of choice regarding carrying forward of tax loss can be exercised by the persons during the first year in which they have formed positive financial result for taxation purposes before the tax loss is deducted.

Tax relief for hiring unemployed persons (Art. 177): Employers having employed an unemployed person under certain conditions are entitled to recognising for tax purposes of an amount equal to twice the expenditure on employment remuneration and social security contributions at the expense of the employer (for the first 12 months of employment). There is no restriction regarding eligible economic sectors.

Exemption of financial instruments admitted to trading on a regulated market (Art. 44 and 196) and of collective investment schemes, admitted to public offering in Bulgaria, national investment funds under the Collective Investment Schemes and Other Undertakings for Collective Investments Act, and the companies with a special investment purpose under the Companies with a Special Investment Purpose Act (Art. 174-175).

Remission of up to 100% of the corporate income tax for undertakings engaging in manufacturing activities in municipalities with high unemployment (Art. 184-189).

The Value-Added Act (VAT Act)

Special arrangements for charging value added tax upon importation and reduced 30-day period for refund of the value added tax in the implementation of an investment project (Art 57, Art. 164-167).

Special arrangements for postponed accounting of VAT upon importation (Article 57(5) and (6) and Art. 167a/b)). This regime has been in force since 1 July 2019.

The Social Insurance Code and the Law on Income Tax of Physical Persons

Tax reliefs concerning supplementary mandatory pension funds under the Social Insurance Code (Art. 160. (1), Art. 161-162).

Tax reliefs concerning supplementary voluntary pension funds under the Social Insurance Code (Art. 253-255).

Note: *In the meaning of § 1, item 24 of the Additional Provisions of the Corporate Income Tax Act, “Research activity” shall denote the activity of development, design, creating and testing of new goods, materials, production technology and technology for industrial systems and other objects of industrial property, as well as the improvement of existing products and technology.

Source: Government of Bulgaria, 2021

To be certified as a supported investment project in Bulgaria, investment needs to meet several criteria. First, it must relate to the establishment of a new enterprise, extension of an existing enterprise, diversification of the output into new products, or a material change in the overall production process. For Class A, B and C projects, investment must be implemented in specific economic activities, according to the Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community (NACE Rev. 2), i.e.: manufacturing (with certain exceptions) or in specific high value-added services sectors (i.e. high technology activities in computer technology, R&D, accounting, tax and audit services, education and health care and storage of goods).8 The project also needs to satisfy the minimum investment and job creation requirements; and needs to comply with other conditions related to the project’s realisation, duration, source of financing, and purchases of inputs, among others.9 Priority investment projects do not need to belong to a particular sector and are those that are considered essential for the economic development of the country or its regions and are required to have at least EUR 51 million of investment or 200 newly created jobs, unless other conditions apply.10

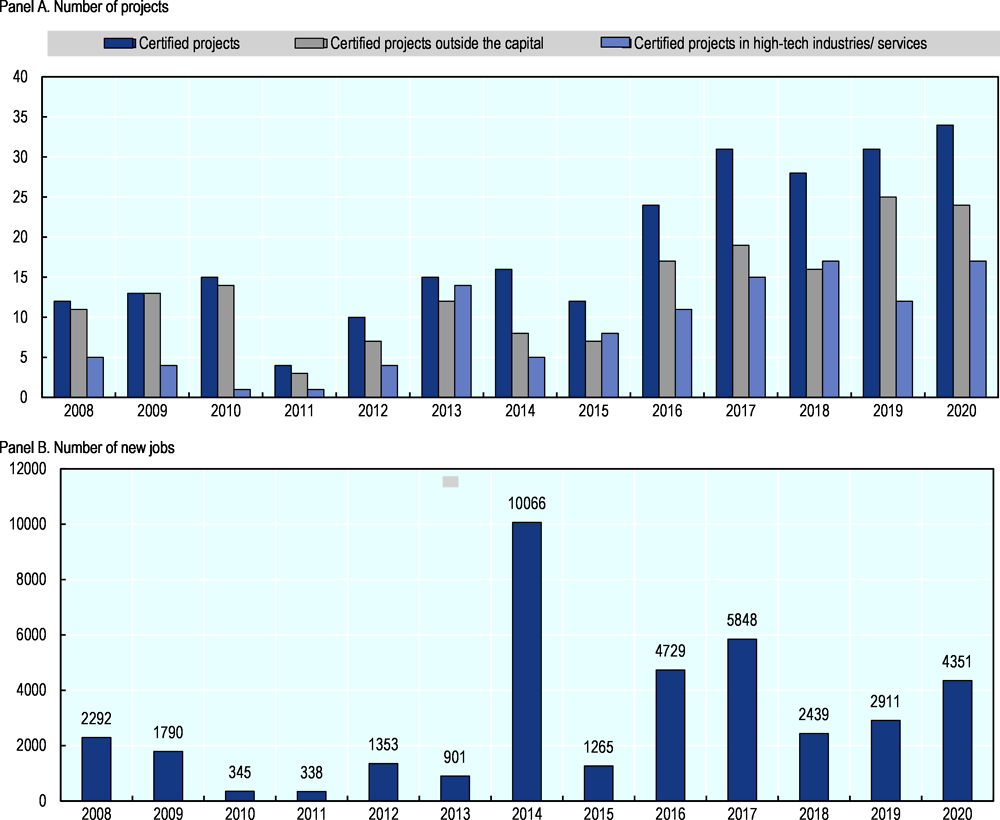

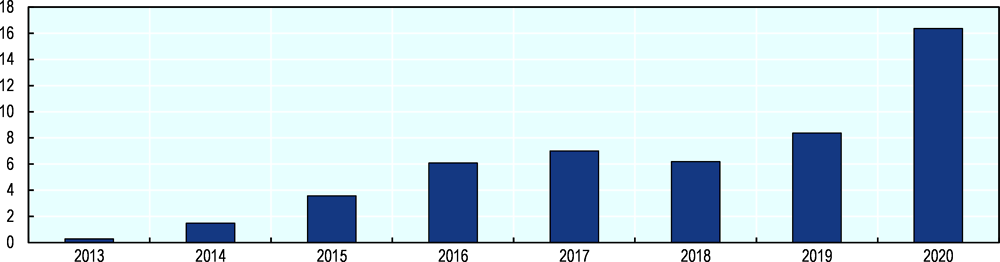

Under the previous administration, the information on certified investment projects in Bulgaria was collected by the Ministry of Economy.11 According to the data provided by Bulgaria’s Ministry of Economy, between 2008 and 2020 a total of 245 certificates were issued under the Investment Promotion Act and the Regulations for its implementation, which resulted in the creation of 38 628 new jobs (Figure 6.4). In addition, according to the data on IBA’s website, most of the supported projects were Class A projects and a handful of priority investment projects during that time. Between 2013-20 the Ministry of Economy of Bulgaria allocated BGN 49.4 million (approximately EUR 25.2 million) from its budget to financial incentives dedicated for investment projects certified under the AIP (Figure 6.6).

The Act on Investment Promotion stipulates the type of financial incentives available of firms in Bulgaria as well as outlines the eligibility criteria and explains the application process. These include Class A, B and C and priority certified investment projects explained in turn below.

Class A and Class B Investment Certificates allow for the following incentives:

Administrative services delivered in one-third of usual time (Class A and B);

Individual administrative service provided by InvestBulgaria Agency (Class A);

Acquisition of property rights or establishment of limited rights to real estate state or municipal property without tender or competition after market price determination by two independent assessors (Class A and B);

Financial support for construction of public infrastructure, i.e. local roads, water supply and sewerage (Class A or for two projects within one industrial zone);

Financial support for training for attainment of professional qualification for investments in high technology activities or municipalities with high unemployment (Class A and B);

Financial support for partial reimbursement of the obligatory social insurance contributions made by the investor for the new jobs created with the investment project for a certain period of time (Class A and B).

Class C Investment Certificate allows for the following incentives:

Administrative services delivered in one-third of usual time provided by the mayor of the municipality in which the investment project is implemented;

Individual administrative service provided by the mayor of the municipality in which the investment project is implemented;

Acquisition of property rights or establishment of limited rights to real estate municipal property without tender or competition after market price determination by two independent assessors (the incentive is provided in case that it was not requested by an investor upon the issuing of a certificate for Class A and B or for a priority investment project for the same real estate).

Priority Investment Project Certificate allows for the following additional incentives (in addition to all Class A incentives):

Acquisition of property rights or establishment of limited rights to real estate could take place at prices lower than the market price (but not below tax assessment) and exemption from state fees for changing the land use;

Institutional support by an inter-ministerial working group for administrative assistance (convened on an ad hoc basis);

Public-private partnership with regional authorities and municipalities, with universities and other organisations from the academic community, including for acquisition of real estate (see above) or for technological park development.

Source: Act of Investment Promotion and the Government of Bulgaria (2021).

Industrial zones

Besides investment incentives described above, Bulgaria also offers investors advantages associated with locating in one of its industrial zones. According to IBA’s website, there were in 2021 about a dozen of functional industrial zones in Bulgaria and another dozen with the infrastructure ready and available for investment or being under development. Through the catalogue of industrial zones available on IBA’s website and the website of the National Company Industrial Zones (NCIZ), detailed information on over 30 such zones is available (Table 6.2). The Bulgarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry also provides information on the different industrial zones and parks available in the country.12

There are both private and publically managed industrial zones in Bulgaria. At the time of writing this Review, the NCIZ was a company under the guidance of the Bulgarian Ministry of Economy, whose mandate was to design, develop and manage industrial and free zones. In 2021, the company managed 12 industrial zones, seven of which were in operation (Sofia, Burgas, Vidin, Ruse, Svilengrad, Stara Zagora and Varna) and five under development (Kardzhali, Karlovo, Telish, Suvorovo and Varna). According to the information provided by IBA, NCIZ and the National Institute of Statistics of Bulgaria, these zones jointly accounted for a sizable share of the national territory and about 60% of them were located in regions above the national level of poverty.13

Importantly, industrial zone users in Bulgaria do not benefit from a reduced profit tax rate. Instead, there are free zones used not only for custom purposes but also aiming at providing investors with high-quality infrastructure. Technological parks also need to satisfy the conditions of an industrial zone and additionally host predominantly scientific research and development activity, education, information technologies or advanced manufacturing, among others.14 According to AIP, investment projects aiming to create an industrial zone or a technological park are eligible to become certified investment projects. The draft proposal of Industrial Parks Act that aims to regulate the legislative framework for the creation and management of such parks, was adopted by the Bulgarian Parliament in February 2021 and later promulgated in March 2021.15

Overall, considering the number of industrial zones in Bulgaria, the pace of creation of new ones and the share of territory that they occupy, they appear to be an instrument that has been encouraged by the government. Yet, creating areas of such type of good quality and that deliver broad-based development impacts for the local economy can be a difficult task. For example, according to a UNCTAD survey (2019), over half of the special economic zones globally are deemed underused. Based on data on the territory available in different zones, the utilisation rate of industrial zones in Bulgaria also appears low.16

The government could reflect on the factors needed to increase attractiveness of the existing zones and ensure a good governance framework. While zones in Bulgaria do not offer other benefits than customs duty exceptions and access to infrastructure, thus minimising the amount of tax revenue forgone, the costs associated with creating and maintaining their infrastructure need to be weighed against the benefits of (additional) investment attracted. As a first step, the government could ensure that the information on available facilities and the associated investment and number of jobs is available and monitored in a systematic fashion – for example, via consolidated reports to the responsible ministry, which can be made publically available. In addition, a cost-benefit analysis of zones that benefit from state’s involvement and investors’ surveys could also be helpful in deciding about the zones current value-added and potential reforms needed.

EU funds’ role in mobilising investment

Another aspect influencing Bulgaria’s investment attraction policy is the availability of EU funds. Bulgaria is one of the countries that benefits most from the EU support. Under the funding framework for 2014-20, Bulgaria was allocated EUR 9.9 billion via several programmes under the European Structural and Investment (ESI) funds (Box 6.5). This represented an average of EUR 1 363 per person from the EU budget in 2014-20. This means that an additional source of financing is available for eligible investors operating in Bulgaria. As these funds also support and mobilise additional private financing in certain priority areas, they can increase financial liquidity of firms. In the medium and long run, they can also support building of necessary infrastructure and educating the labour force required by investors to consider Bulgaria an attractive investment destination.

For example, a large share of EU funding goes towards greening of the economy (i.e. increasing resource efficiency, environmental protection and climate change adaptation and risk-prevention) as well as educational and vocational training initiatives, research and innovation and high-quality employment. Programmes related to improving local infrastructure that would increase connectivity, improving competitiveness of SMEs and social inclusion are also important (accounting jointly for nearly 30% of funding). Finally, technical assistance and support to public administration can also support the process of professionalising and improving the capacity of government authorities. The creation of the Technology and Innovation Network (T+IN) or “Sofia Tech Park” – the first science and technology park in Bulgaria – is an example of a project created with EU co-financing, which supports the creation of foundational infrastructure for investment attraction in high-value activities.17 While recent evaluations show that the park grapples with several governance and management challenges (European Commission, 2018b), its creation marks an important step in the process of strengthening the local technological ecosystem.

The financial allocation from the EU Cohesion Policy funds* for Bulgaria amounted EUR 9.9 billion in the framework of the Multiannual Financial Framework 2014-20. By the end of 2019, some EUR 7.4 billion (about 85% of the total amount planned) was allocated to projects, while EUR 3.6 billion was reported as spent with implementation levels in line with the EU average.

EU Cohesion policy funding significantly supports structural challenges in Bulgaria. The Cohesion Policy programmes for Bulgaria have allocated EU funding of EUR 1.1 billion for smart growth, EUR 4.1 billion for sustainable growth and sustainable transport and EUR 1.9 billion for inclusive growth. In 2019, following a performance review, EUR 386 million were made available for Bulgaria for these priorities; and EUR 126 million (including national co-financing) need to be reprogrammed by the authorities within the above priority areas.

EU Cohesion policy funding provides investment in research, technological development and innovation, competitiveness of enterprises, sustainable transport, education, employment and social inclusion, among others. According to the Ministry of Finance of Bulgaria, the estimated effect of EU Funds boosted GDP by 7.7% and helped generate approximately 12.5% higher employment by 2020.

Agricultural and fisheries funds and other EU programmes also contribute to addressing the investment needs, such as the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund. Bulgaria has also benefitted from other EU programmes such as the Connecting Europe Facility and Horizon 2020.

Note: *European Regional Development Fund, Cohesion Fund, European Social Fund, Youth Employment Initiative, including national co-financing. ‡ Data available on the website of the Ministry of Finance: https://www.minfin.bg/bg/1168 Δ European Regional Development Fund, Cohesion Fund, European Social Fund, European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development Fund and European Maritime and Fisheries Fund.

Source: EU Commission (2020a)

According to the EU, nearly 5 000 firms have benefitted from support under the ESI funds and nearly twice more are planned to benefit from the support in the future (European Commission, 2020b/d).18 In addition, EUR 0.14 billion in private match grant aid has already been implemented. In terms of the impact on infrastructure, the EU funds are planned to lead to a reconstruction of 665 km of roads and 166 km or rail as well as the creation of 67 km of new roads. It will also involve a creation of new water supply, waste treatment and flood protection facilities, among others. Finally, it will offer training and improved working prospects to participants. The allocation of EU funds is centralised at the Ministry of Regional Development, and, at the time of writing of this Review, there were discussions towards a possible reform.19 Overall, the allocation of EU funds and additional private financing facilitated through this channel can offer new business opportunities both to domestic and foreign-owned firms interested in locating Bulgaria.

Specific programmes to support small and medium-sized enterprises

SMEs play an important role in the Bulgaria economy. They generate two-thirds of total value added and three-quarters of total employment, above the EU average (European Commission, 2019). Meanwhile, their annual productivity, calculated as value added per person employed, is approximately one-fourth of the EU average. Unsurprisingly, as discussed above, a sizeable share of EU structural and investment funds in Bulgaria is allocated to SME development. The SME Initiative is an example of an EU-co-financed programme designed to facilitate SME financing. Moreover, in reaction to COVID-19, additional funds from the “Innovations and Competitiveness” programme were made available to support SMEs (European Commission, 2020c).

The importance of EU funds and policies in shaping the overall framework for supporting SMEs in Bulgaria is evident in the institutional and policy set-up in this area. The main strategic document in this domain until 2021 was the National Strategy for Promotion of SMEs 2014-20, which was based on the Small Business Act for Europe (SBA). In 2021, a new strategy for 2021-27 was adopted with financial support from the European Commission.

At the end of 2021, the main institutions responsible for supporting SMEs, including their internationalisation and access to finance, were: the Bulgarian Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Promotion Agency (BSMEPA); the responsible body for the Operational Programme “Innovation and Competitiveness” under the Ministry of Economy; the responsible body for the SME Initiative Operational Programme; the Bulgarian Development Bank; and the Fund of Funds, managing four operational programmes co-financed by the EU.

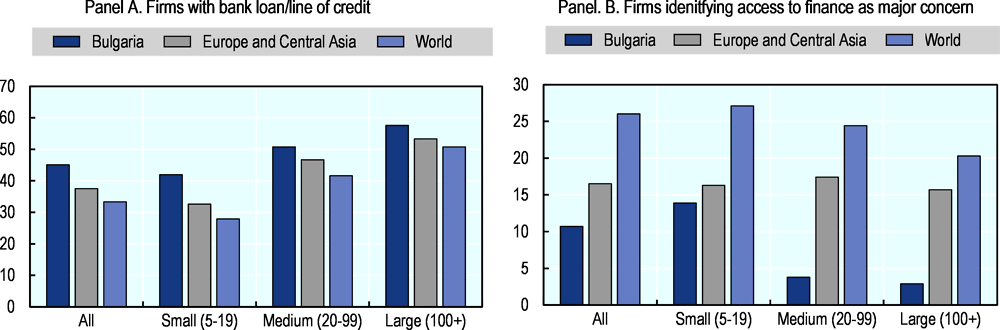

According to the European Commission, in 2019 Bulgaria was lagging behind in several areas related to implementing the SBA (European Commission, 2019a). The main challenges for Bulgaria lie in upskilling its workforce, encouraging SME investment in innovation and fostering growth in entrepreneurship as discussed earlier in this Review. According to the 2018 survey on SMEs conducted by the European Commission and the ECB, almost 30% of SMEs surveyed identified availability of skilled staff or experienced managers as their biggest challenge (EBRD, 2020). Slow progress in simplifying administrative procedures, discussed in the last section of this chapter, has also been pointed out as affecting SMEs adversely. Meanwhile, Bulgaria has made significant progress in improving the access to finance of SMEs, including through the use of different programmes co-funded by the EU. This is consistent with the results of the World Bank Enterprise Survey (2019) that showed that many firms had access to credit lines in Bulgaria and only 11% of local firms considered access to financing as major concern, which is significantly below the regional and world averages (Figure 6.7). In the recent years, the government offered several additional financial instruments available to SMEs (Box 6.6).

The overall progress in reducing administrative burdens on all firms will be reviewed later. Nevertheless, some initiatives aimed specifically at SMEs are worth highlighting here. For example, the Ministry of Economy and Industry developed a “Business Guide for SMEs”, available since 2019, aiming to explain in simple terms the steps that entrepreneurs need to take in commonly encountered situations, ranging from starting a company, hiring staff to resolving insolvency, to comply with 120 most complex and common regulations.20 The information, organised by themes, was made available online, in both Bulgarian and English. In addition, as part of the overall process of improving the quality of new regulations in the country – discussed in the next chapter – the government has made more systematic use of the “SME Test”, i.e. considering ex ante the possible impact of proposed regulations on SMEs.

Supported by EU funds, the Bulgarian Government announced creation of several financial instruments and other measures to ease SMEs’ access to finance in the last few years, e.g.:

The voucher scheme for the provision of securities-issuing services in the capital markets connecting SMEs with service providers in the field of securities issuance.

The “Risk-sharing micro-finance facility” funded through the Operational Programme Human Resource Development 2014-20, co-financed by EU finds, that provides micro loans of up to EUR 25 000 to support the establishment and development of start-ups.

The “BrightCap Ventures capital fund” in which EU co-financed JEREMIE invests EUR 20 million and BrightCap Ventures raise additional private capital. The fund will invest in early stage companies with the potential for significant growth in the global market. The investments will be in the range of EUR 0.5 to EUR 3 million. Part of the fund will be dedicated to supporting newly created companies (accelerator).

The Venture Capital Fund is making available EUR 24.4 million in public funds for management under another programme, co-financed by EU funds. The Fund provides financial support to start-ups/SMEs during their first five years. The investment in each selected start-up or SME will range from EUR 750 000 to EUR 3.5 million.

Innovation Accelerator Bulgaria of EUR 15.6 million, co-financed by EU funds, has the mandate to provide access to equity and quasi-equity funding to Bulgarian start-ups. The financing targets entrepreneurs at the earliest stages of business development. Mentoring and strategic support to companies will be provided.

Finally, the Fund for the support of innovative start-ups will provide financial support (equity and quasi-equity investments) and business support to early stage entrepreneurs.

Source: European Commission (2019).

Overall, further progress in reducing administrative burdens, proposing simplified solutions and e-services can have an important impact on SMEs. Due to important knowledge and skills gaps identified in local SMEs, BSMEPA can play an important role by providing capacity-building support and help local firms reach foreign markets. Its network of regional offices can help it reach firms in different regions.21 Given the potential learning and upgrading opportunities offered by business linkages between domestic and locally established foreign firms, new programmes and collaboration with the IBA (see next section) could be beneficial in this regard. Moreover, considering the importance of difficulties in hiring skilled labour locally, faced by both foreign enterprises and domestic SMEs, BSMEPA and IBA could consider offering specific services in this area.

National investment promotion agency can be an important and relevant actor in the institutional landscape for investment promotion and facilitation. The economic literature shows that IPAs help bridge information asymmetries and attract investment into the local economy (Volpe Martincus et al., 2020; Harding and Javorcik, 2011/ 2012/2013; Alfaro and Charlton, 2007). Yet, agencies differ substantially in their characteristics and the type of and quality of services provided to investors, which in turn can affect their effectiveness in FDI attraction (OECD, 2018; Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska, 2019). In the case of Bulgaria, the InvestBulgaria Agency, serves this function. As the agency participated in the OECD-IDB survey of IPAs (Box 6.7), its characteristics and activities have been compared to agencies in the OECD countries.

The OECD and the IDB have partnered to design a comprehensive survey of IPAs. The questionnaire provides detailed data that reflect the recent policy developments and provide rich and comparable information on the work of IPAs in different countries. The survey was shared with IPA representatives from OECD and Latin America and Caribbean countries in the form of an online questionnaire, covering nine areas:

National IPAs from 32 of the 38 OECD countries participated in the OECD- IDB survey. The detailed data gathered through the survey has allowed rich cross-country analysis and served as a basis for a preparation of a mapping report of IPAs in OECD countries (OECD, 2018) as well as benchmarking with other regions, including Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa and South-Eastern Europe.

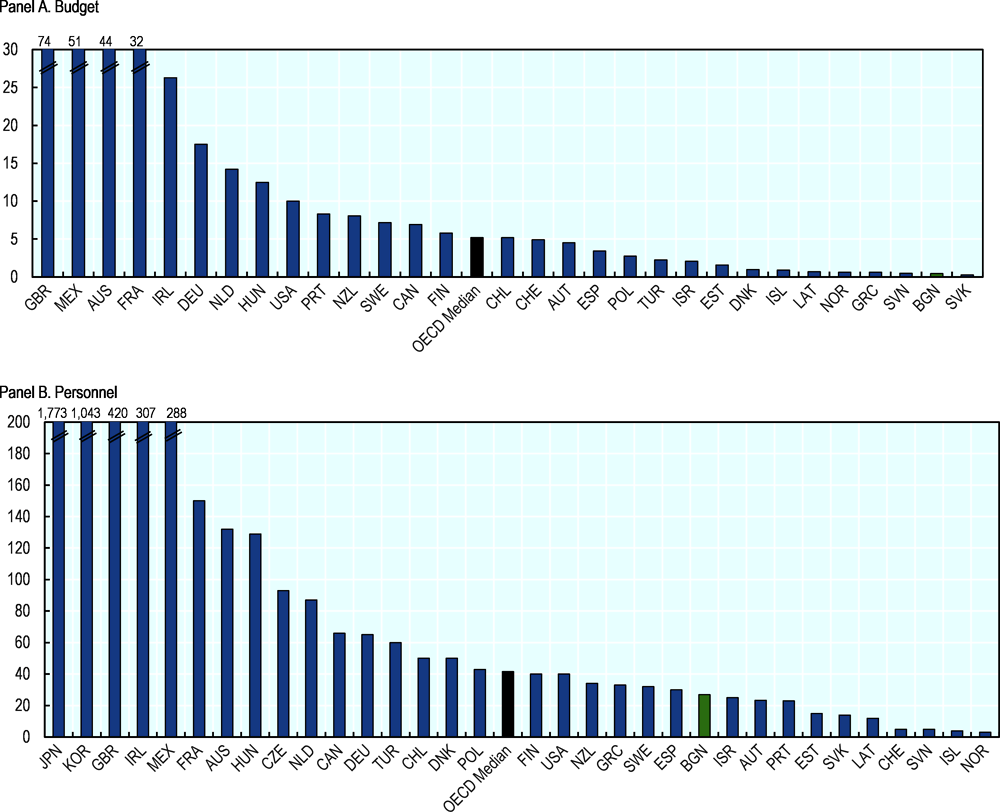

Invest in Bulgaria: Mandate, governance, and accountability

InvestBulgaria Agency (IBA) is an executive agency public agency, reporting to the government. Its overall objective is to provide free-of-charge information, contacts and project management support services to potential investors (Box 6.8). In 2021, with a total budget of approximately EUR 0.47 million and 27 employees, IBA was one of the smallest agencies across the OECD countries (Figure 6.8).22 The agency’s budget has been increasing progressively in 2014-18 with a small downward adjustment in 2019 (Panel A in Figure 6.8). In 2021, all of the agency’s budget came from the state’s budget and was allocated by the Ministry of Economy to which it reported. The minister also appointed the Head of IBA. It had annual targets in terms of assisted projects and provided quarterly and annual reports to the Minister of Economy on the completion of its objectives. Unlike most of the OECD IPAs (OECD, 2018), at the time of writing of this Review, IBA did not have a Board overseeing its activities. Therefore, based on the different components of the OECD-IDB IPA Institutional Independence Index, IBA showed a relatively low degree of independence (Volpe Martincus and Sztajerowska, 2019).23 Since early 2022, the new Ministry of Innovation and Growth has been responsible for managing all key state agencies in charge of promoting strategic investments, including IBA.

InvestBulgaria Agency (IBA) is a government body providing free-of-charge information, contacts and project management support to potential investors. Its services include:

Visa and other administrative support for potential investors

Identification of potential project location, including identification of facilities for Brownfield projects or office locations for outsourcing and IT projects

Identification of potential suppliers, clients and other business partners

Administrative support with permits and regulations with regards to hiring personnel, purchasing or renting facilities, etc.

Source: IBA (2021)

In 2021, most IBA’s staff and budget were devoted to investment facilitation and retention (Panel B in Figure 6.9). This is a common pattern in OECD agencies where investment generation and facilitation account for two-thirds of resources of a typical IPA (OECD, 2018). It also reflects IBA’s role in facilitating the process of investors’ applications to become a certified investment project, described earlier. The agency also provided support to other potential investors by linking them with local consulting and legal firms, providing information on applicable regulations or facilitating contact with other authorities, for example. In a typical year, IBA assisted about 300 firms, 20 of which were certified investors.24

At the time of this Review, the agency had several mandates. Besides inward FDI attraction, IBA also assisted domestic investors interested in investment opportunities at home and in foreign markets. As such, it had more official functions than the OECD average (Figure 6.10). Some of them, such as granting of incentives and negotiations of international agreements, were not typically found in OECD IPAs (Figure 6.11). Yet, as explained earlier, IBA’s role regarding the former relates mostly to processing of investors’ applications, while the ultimate decision regarding state support resided in the Ministry of Economy. While most OECD IPAs perform both investment and export promotion functions, in case of Bulgaria, this task was performed in another agency, BSMEPA, as discussed earlier. BSMEPA also reported to the Ministry of Economy, and, according to IBA, the two organisations co-operated well together.25 This type of arrangement is also practiced by OECD IPAs, where some agencies merge these two functions and others prefer keeping them apart (OECD, 2018).

Unlike many OECD similar institutions, at the time of writing this Review, IBA did not have an explicit regional development mandate. It still rendered some services that support provision of information about investment opportunities across Bulgaria’s different regions. For example, it provided a list of all available investment projects and vacant land for investment projects across the country.26 Yet, in the framework of this Review, IBA reported to the OECD Secretariat not to collaborate with regional bodies responsible for investment promotion. It explained that it consulted them or intervened only as necessary, for example to facilitate investor’s landing or when a firm encountered a particular problem. As a result, at the time of writing this Review, no rules and procedures appeared to be in place to facilitate co-operation between IBA and existing subnational bodies, and the agency did not seem to be fully aware of IPAs operating at the sub-national level. Meanwhile, various major cities have their own municipal-level investment promotion bodies, some of which have well-developed websites and offer investors various services. The lack of explicit co-operation may lead to a duplication or discoordination of efforts, reducing their overall impact.27

Considering that the reduction of social and territorial inequalities is one of the government’s priorities, as expressed in the NDP BULGARIA 2030, this area may merit the government’s attention. Most OECD IPAs considers regional agencies as strategic partners and report to have frequent contact with them. As such, the ministry in charge of promoting investments could consider if and how to best systematise co-operation between IBA and bodies responsible for investment promotion at the sub-national level. Possible approaches include the use of common guidelines, joint participation in events, access to common information systems, exchanges of staff and incentives for agencies (OECD, 2018).28 Feedback from regional partners, business and other stakeholders could provide useful inputs in this regard.

The agency’s prioritisation strategy is shaped by the provision of investment incentives

In the case of Bulgaria, the process of prioritisation of investors by the IPA appears to be largely determined by EU state aid regulations and the associated national regulations.29 The AIP, described earlier, establishes IBA as the agency assisting eligible firms in the application process for state support. Yet, some strategic documents, such as the past “Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialization of the Republic of Bulgaria 2014-20”, have provided further guidance on potential sectors where Bulgaria may have a competitive advantage. As such, they could provide insight as which activities IBA could usefully target as part of its prioritisation efforts in investment attraction.30 These sectors broadly correspond to those which were listed on IBA’s website at the time of writing this Review, and for which the agency provided detailed information and brochures.31 In order to increase its impact as an IPA, IBA could consider boosting proactive investment generation activities in high-potential sectors.

Proactive prioritisation could also take place by type of investor. The business consultations conducted by IBA when preparing a report on the possible impact of COVID-19 revealed that some firms believed that a successful attraction of one large corporate player could help locate Bulgaria on the radar of foreign investors and facilitate the process of reducing the existing obstacles to doing business. To increase the probability that an investor of such calibre establishes locally, IBA could consider explicitly targeting large or “lead” investors as part of its prioritisation strategy. For example, some OECD IPAs explicitly target companies on “Forbes 2000” list or established brands (OECD, 2018). Considering IBA’s small size, it could usefully be supported in this task by the ministry in charge of investment promotion and other government bodies. For example, planned state visits at the highest level could be used to hold relevant meetings with the private sector in a given destination.

Last but not least, to assist it further in fine-tuning of its prioritisation effort, the agency could improve its monitoring and evaluation system. While the agency did have in 2021 an internal data collection system, it was still rudimentary. Unlike most OECD IPAs, the agency, at the time of writing this Review, did not have a Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system. Designing and implementing a CRM could help improve the agency’s internal data management, facilitate systematisation of investors’ information for proactive targeting and facilitate internal resource management (Sztajerowska, 2019). As development and tailoring of CRM systems takes time and often is a reiterative process, the agency may need to consider future resources required for the upkeep and adjustments of the system and any possible training of staff. The implementation of a high-quality CRM could also help the agency track better the quality and effectiveness of its services. It could also consider undertaking more systematic surveys of firms to gain insights on how to adjust its services and help identify key obstacles to investment attraction and retention.32 Publishing surveys’ results or using them in conversations with the government can be a potent policy advocacy tool (de Crombrugghe, 2019).

Investment facilitation and aftercare is important, especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis

Studies suggest that the impact of IPAs is strongest when such agencies bridge information asymmetries, for example by providing high-quality and timely information to firms (Volpe Martincus et al. 2020). This is critical for new investors not familiar with the local conditions and those already operating locally that wish to expand their operations encounter difficulties, or face changed business conditions. As such, OECD IPAs give particular attention to investment facilitation and aftercare services (OECD, 2018).

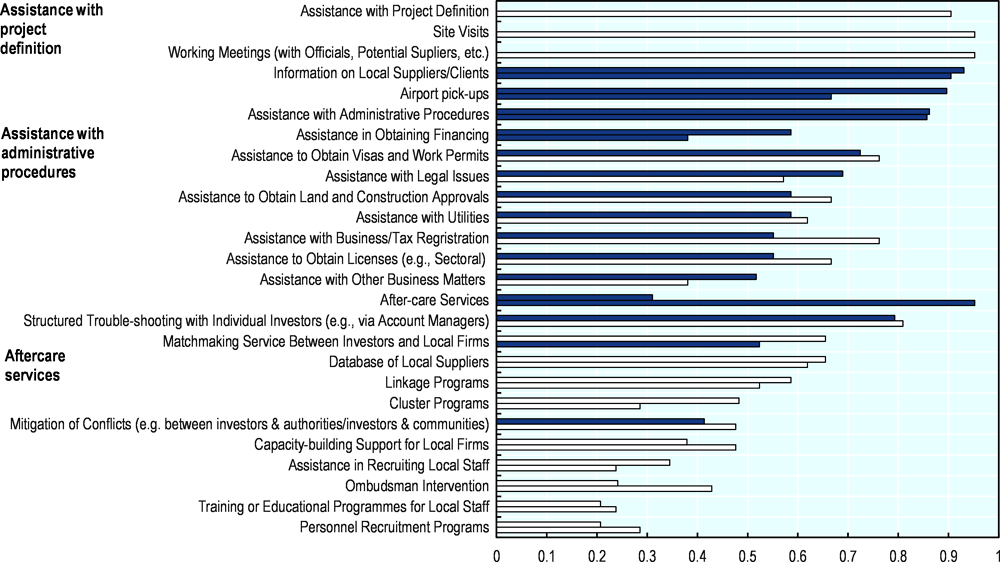

Overall, IBA reported in the framework of this Review to provide all standard investment facilitation services associated with project definition and obtaining administrative procedures offered by OECD IPAs (Figure 6.12). In case of certified priority investment projects, IBA can also create ad hoc working groups with the relevant government authorities to resolve a particular issue encountered by an investor (upon request). Yet, unlike OECD IPAs, IBA at the time of writing this Review, provided a rather limited array of aftercare services to all established investors. For example, it did not provide any matchmaking, linkage, cluster-development, or capacity-building support to local firms. Nor did it offer any personnel recruitment or training support or educational programmes to local staff. Considering the importance of local skill shortages in Bulgaria, as highlighted by business surveys quoted earlier in this chapter and as fully recognised in Bulgaria’s most recent development strategies, IBA could consider if it could not usefully support initiative of this type. The experience of the IPA of Costa Rica (CINDE) could provide a useful example in this regard (Box 6.9). Projects designed together with BSMEPA could ensure that such programmes are tailored to SME needs.

CINDE Invest in Costa Rica is the national investment promotion agency of Costa Rica established in 1982. Its official mandate is the. attraction of foreign direct investment into the local economy. Yet, through its activities, it is also supports broader objectives of sustainable development and improving competitiveness of the local economy. Among others, it aims to strengthen the links between the enterprises it attracts and the local economy, and improve the level of skills and labour market outcomes of the local population through several programmes:

For example, CINDE helped create an online platform, “The Talent Place” (www.thetalentplace.cr) that provides detailed up-to-date information regarding most in-demand occupations, current vacancies in the companies located Costa Rica, skills required to apply and links to resources to build them and obtain needed certification, including though free-of-charge online courses.

Aiming at directly linking employers with employees, CINDE also organises, on an annual basis, “CINDE Job Fair” (www.cindejobfair.com), allowing for matching available vacancies in MNEs that were attracted by CINDE with potential jobs seekers. During the 15 years of the fair’s operation, 10 000 people assisted the fair and 24% of which have completed the recruitment process.

Together with the Ministry for Science, Technology and Telecommunications and “Essential Costa Rica”, responsible for the country brand, CINDE has also designed a programme for innovation and human capital development (Programa de Innovación y Capital Humano, PINN). The initiative provides Costa Rican nationals with access to scholarships funding educational opportunities in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). The programme is supported by the Inter-American Development Bank, and CINDE serves as a certification and capacity-building body under one of its pillars.

In light the COVID-19 crisis, in April 2020, CINDE also created an online platform that offers information on job vacancies available in MNEs located in the country. The goal has also been to facilitate a transfer of employees from sectors most affected by the pandemic (e.g. tourism) to other sectors that have remained relatively intact as well as more generally support worker mobility. As of April 2020, 950 jobs were on offer on the platform.

While being important in normal times, effective investment facilitation has become a critical capacity of an IPA during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Unsurprisingly, the majority of OECD IPAs rapidly reoriented their services towards facilitation and policy advocacy support during the COVID-19 outbreak (OECD, 2020a). In 2020, nearly two-thirds of OECD IPAs had a dedicated and regularly updated COVID-19 section in English on their website and many more provided information in other forms. A number of agencies had also readapted their activities to focus on existing clients. For example, they had dedicated most of their staff’s time to informing firms about government programmes and support their ongoing investments and operations. In this context, having a list of locally established firms and well-designed CRM have proven useful to identify and prioritise investors quickly. IPAs also activated their existing business networks, particularly in the health sector, to help the government fight the crisis.33 Both in the immediate aftermath of the crisis and in the medium to long term, many OECD IPAs have also scaled up the use of digital tools for the delivery of services and are rethinking their priority sectors to adapt to the new market reality.34

IBA has undertaken many similar steps in face of COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the agency – that also entered a teleworking mode as many other European IPAs – continued operating and servicing clients through digital means during the pandemic. For example, it made use of social media (e.g. YouTube, Twitter, Instagram) to communicate with clients on the applicable regulations, government support measures and other relevant issues. It also prepared a report on the likely impact of COVID-19 on FDI and projects assisted by IBA and a newsletter.35 IBA also played an active role in policy advocacy during the pandemic. For example, as a result joint efforts with the Ministry of Economy, a regulation issued by the Ministry of Health allowed certified investors to cross borders without the usually applicable quarantine requirements (Regulation No. RD01 274). Finally yet importantly, in 2020, the agency actively considered potential implications of the crisis for competitive niches available to Bulgaria. In particular, IBA aimed to position Bulgaria as an attractive business location, offering low production costs in close proximity of the EU market, to benefit from potential near- and offshoring opportunities that may arise after the pandemic.36

Building on these initiatives, IBA could consider following the examples of OECD IPAs to further adjust its services beyond the COVID-19 crisis. For example, it could follow the example of several OECD IPAs to provide investors with all the relevant information on its website.37 It could also reflect more systematically how its prioritisation strategy may need to change in light of a projected drop in FDI and its uneven sectoral impact (OECD, 2020b; UNCTAD, 2020).

Bulgaria could reduce administrative burden to further improve business climate

The quality of regulation has a significant influence on the climate for business and investment. Poorly designed or weakly applied regulations can slow business responsiveness, divert resources away from productive investments, hamper entry into markets, reduce job creation and generally discourage entrepreneurship (OECD, 2015a). In this context, the challenge for governments is, on one hand, to balance their need to use administrative procedures as a source of information and a tool for implementing public policies, and on the other, to minimise the interferences implied by these requirements in terms of the resources required to comply with them (OECD, 2009). There are various tools at the disposal of the governments achieve this objective. These include periodic reviews of the stock of regulations, simplifying administrative procedures and introducing e-government services on top of developing better rules on creating new regulations and oversight of regulatory processes, discussed in more detail in the next chapter on public governance.

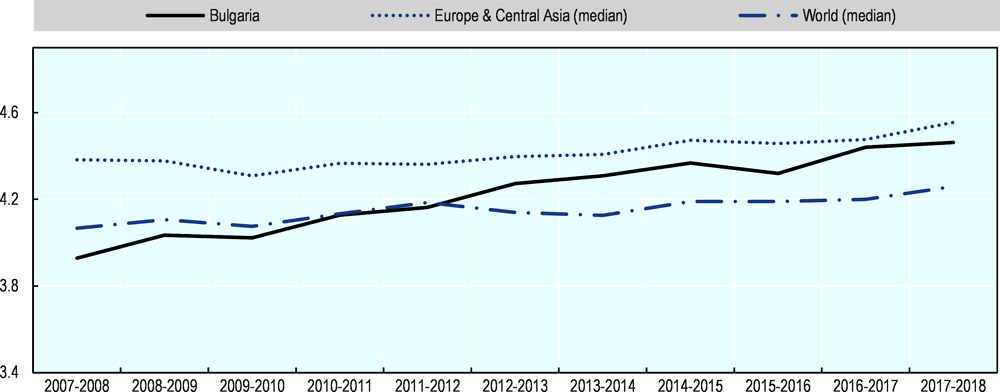

While the country has made progress in reducing the administrative burden, as captured by the change in its ranking on the World Economic Forum’s Global Competiveness Index over the past ten years (Figure 6.13), the ease of obtaining licenses and permits, as perceived by businesses, apparently remains a challenge to doing business in Bulgaria. Bulgaria scored 61 out of 190 economies on the World Bank’s Doing Business 2020 and 49 out of 141 economies on the World Economic Forum’s Global Competiveness Index. While these types of rankings should not be taken at face value, they may point to general tendencies and areas that require government’s attention.

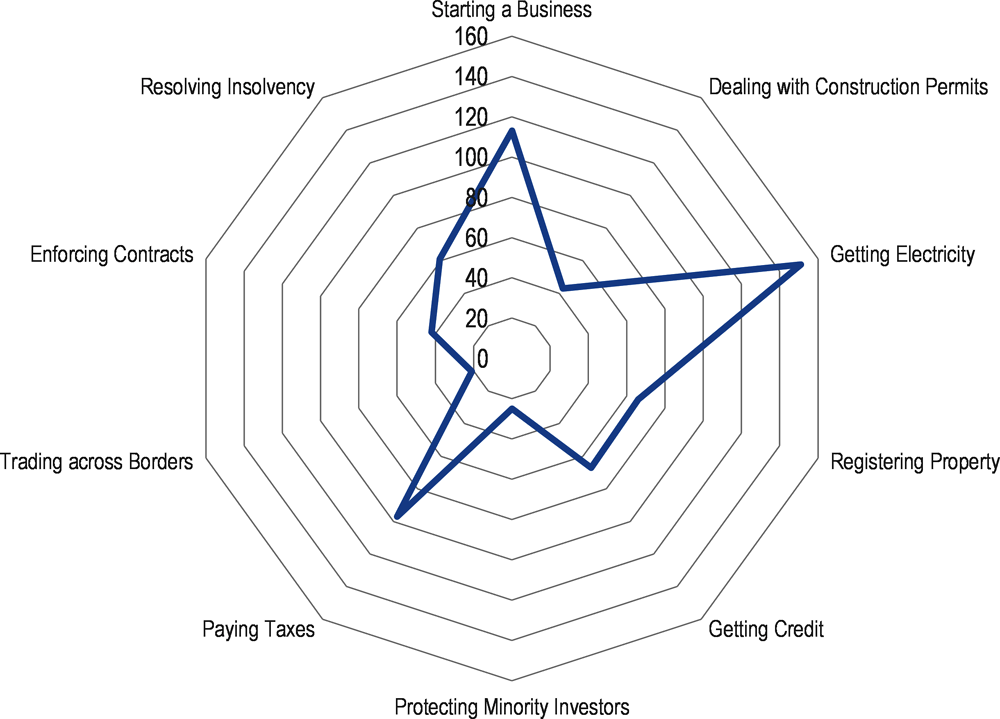

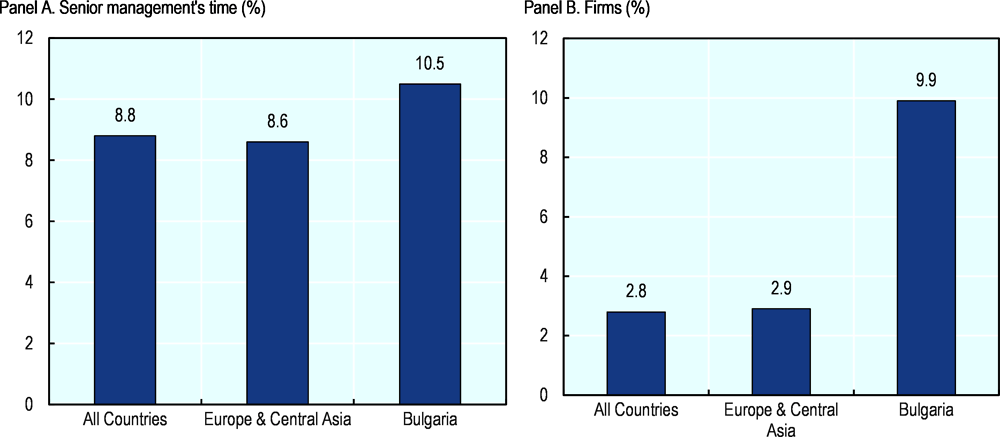

For example, the distribution of scores for different aspects covered by the Doing Business indicators shows that Bulgaria performs relatively better in trading across borders (21) and protection of minority stakeholders (25), and relatively worse in regards to getting electricity (151), starting a business (113) and paying taxes (97) (Figure 6.14). The average times obtained via interviews of firms through the World Bank’s Enterprise Survey 2019 also point in a similar direction, in particular in regards to the time it takes to obtain a construction permit, electricity connection or an operating license.38 Surveyed firms also report that over one tenth of senior management’s time is, on average, spent dealing with the requirements of government regulation and 10% of firms select business licensing and permits as their biggest obstacle (Figure 6.15), i.e. a share higher than those in other countries. As there are large differences across the regions, in some places these shares are higher.39

According to the government, the actual time required to complete administrative procedures and obtain permits is shorter than suggested by Doing Business.40 Yet, its internal analysis identified similar priority areas.41 As highlighted earlier, while in absolute terms other issues are considered more important barriers to doing business in Bulgaria by firms – notably, the lack of adequately educated workforce and competition from the informal sector; in relative terms, reducing administrative burdens has increased in importance (Figure 6.1). In addition, as the country has transposed significant amount of common EU regulations and will be subject to new ones in the future, this has also increased the importance of effectively reviewing and streamlining the growing stock of regulations. The EC, while recognising progress made by Bulgaria in this area, has repeatedly highlighted the need for further reforms (e.g. European Commission, 2018-20).

Responding to these concerns, the government has implemented three consecutive plans for the reduction of administrative burdens between 2009 and 2018. The first and second plan involved a target to reduce the administrative burdens placed on businesses by 20% each, and the third by 30%. According to the government, the targets have been reached.42 The Council of Ministers also sought feedback from the private sector on the impact of these changes on business. Yet, the authorities have highlighted that quantifying and reaching targets have been resource-intensive and feedback obtained from firms has suggested that these actions may not have led to improved perception by business (Renda, 2019).

The government has maintained its efforts in this area to achieve tangible progress. For example, in 2017 and 2018, new measures were adopted to ease administrative burdens on SMEs. The Decision 338/2017 of the Council of Ministers (“Reduction of Administrative Burden”) withdrew the requirement for presenting notarised documents to the public administration. By Decision of 5 October 2018, the Council of Ministers also approved a new package of 1 528 measures aimed at changing and improving administrative services for citizens and businesses.43 In addition, as part of the regulatory impact assessment (RIA), introduced in Bulgaria in 2016 – and discussed in more detail in the following chapter – an “SME Test” has been implemented, which aims to explicitly consider the possible impact of regulations on smaller firms, mentioned earlier.

Patents (www.bpo.bg)

Description: The website gives information on multiple services regarding patents (only in Bulgarian). It provides sample templates and information for paid services.

Electronic Signature Certificate for Businesses (www.crc.bg).

Description: The website gives information on registered providers of certified services in Bulgaria, from whom electronic signature certificate can be requested.

Registration of a new company (www.registryagency.bg).

Responsibility: Central Government, Ministry of Justice, Registry Agency

Description: An online commercial register enables the establishment and reorganisation, restructuring and liquidation of a business. Applications in paper form still apply, especially for businesses that do not possess an eSignature certificate. An option to pay electronically is provided. It is necessary to own an electronic signature.

Corporate tax: declaration, notification (www.nap.bg).

Responsibility: Central Government, Ministry of Finance, National Revenue Agency

Description: Online information and forms can be downloaded, submitted and signed electronically, allowing for the online submission of corporate taxes.

VAT: declaration, notification (www.nap.bg).

Responsibility: Central Government, Ministry of Finance, National Revenue Agency

Description: Online information and forms can be downloaded, submitted and signed electronically, allowing for the online submission of VAT declarations.

Electronic Payments (www.inetdec.nra.bg).

Customs declarations (www.customs.bg/wps/portal).

Responsibility: Central Government, Ministry of Finance, National Customs Agency

Description: There are model forms to download, complete and submit.

Public procurement (www.minfin.bg/bg/procurement)

The government has made strides in digitising administrative procedures and offering e-government services online, including to businesses (see Box 6.10).44 For example, the “Strategy for the development of electronic government in Bulgaria 2014-20” aimed to define broad strategic objectives for the delivery of improved e-services; while the roadmap for its implementation listed specific measures for the realisation of strategic orientations. In addition, the State e-Government Agency (SEGA), established in 2016 pursuant to the Electronic Governance Act,45 has been providing relevant government services via a centralised platform. The number of e-government users has increased since 2018. Yet, many of the e-services provided remain limited to the delivery of information. Further reforms may be considered to facilitate widespread use of e-services and improve the necessary IT infrastructure. One constraint to the e-government expansion has been the challenge to retain IT specialists (European Commission, 2019).

It is worth noting that recognising that complying with administrative requirements may take time. One type of service that allows delivery of different licenses and permits in a streamlined and faster fashion for a large number of firms is an establishment of a one-stop solution (OSS) or a single window for investment. While the specific functionality of OSS will determine which aspect of the investment decision it can simplify, effective instruments of such type provide investors with an ability to issue a whole array of permits beyond the sheer business registration (see e.g. World Bank, 2009). Still, progress in speeding up business registration itself is a welcome step.

Despite recent developments such as the 2019 introduction of a free of charge electronic service under the VAT Act, allowing to submit simultaneously an application for registration with the Commercial Register and a request for VAT registration, it currently takes two times longer to start a business in Bulgaria than in the comparator region and over three times longer than in OECD countries (Table 6.4). While some of the steps in the registration process can already be undertaken online, such as the registration with the Commercial Register at the Registry Agency and registering employment agreements with the National Revenue Agency, potentially in the future all steps could be integrated into one platform.

Going forward, the government could consider if it could not build on international good practices to establish an OSS for investors. An OSS solution for investment can be a physical facility where investors can complete all the required procedures or an online service (Table 6.5). While comparative cross-country data on this issue comes from 2009, already then more than a half of countries worldwide had an OSS solution for investment in place (World Bank, 2009). In addition, such countries tended to have over 30% less procedures and over 50% less time spent dealing with them, according to the World Bank’s Doing Business than countries without OSS solutions. Regardless of a particular form that such solution could take, the most important component is ensuring that it can successfully integrate the processes of issuing different permits to effectively cut the steps in the process, instead of adding an additional layer. Potentially, a capacity-building project with support of the EU or other international organisation could assist Bulgaria in this task.

Bulgaria has achieved noticeable progress in improving its investment climate and increasing overall political stability. The proximity of the EU market and availability of EU funds, which have improved financing conditions for firms and can help transform the country’s infrastructure and train local workforce, can also be advantageous for investors. The country also has a relatively low rate of corporate taxation and provides a well-developed framework for provision of state support that can be attractive for some projects.

Still, several obstacles hinder the country’s investment attraction potential. While Bulgaria has made strides in improving the overall planning and co-ordination of its investment policy, a detailed plan with clearly identified priority reforms and allocated responsibilities of different government bodies and applicable timelines appears to be lacking. The institutions aiming to co-ordinate cross-cutting initiatives and reforms to improve the overall competiveness and business climate are also relatively new and may require further strengthening. In some areas, the rules outlining procedures for co-operation are sometimes lacking, as in the case of IBA’s co-operation with subnational bodies. A publically available list of specific initiatives involving different institutions aiming to address key obstacles could help in achieving progress in difficult horizontal reforms – including reduction of administrative burdens – and ensure that the public is aware of the efforts made.

In regards to the investment promotion agency’s activities, IBA is primarily responsible for managing applications of investors wishing to be certified as a supported investment project under AIP. It is a relatively small agency with low levels of institutional independence. For example, at the time of this Review, it did not have a Board of Directors to oversee its functions, unlike is the case in most OECD IPAs. In the area of investment facilitation, IBA performs most standard services performed by other agencies in OECD countries with a notable exception of aftercare services. For example, it does not offer any linkage or matchmaking programmes between foreign and domestic firms nor personnel recruitment support. Given the skilled labour shortages in the country and potential spillovers from SME-MNE links, IBA could consider designing and implementing initiatives in this area in collaboration with relevant government bodies. Strengthening its prioritisation and monitoring and evaluation capacities could also be beneficial as could greater co-operation with sub-national level bodies.

Besides potentially strengthening aftercare capacities of its IPA, the government could usefully focus on achieving further progress in reducing administrative burdens as foreseen. Considering that the experience with setting and reaching quantitative targets for burden reduction has been mixed, existing diagnostics and feedback from business could be used to identify high-impact reforms. Given the time it takes to establish a business and obtain electrical connection, these could be natural areas of focus. In this context, the government could consider if an OSS solution for investment could be feasible and useful, especially building on the progress made in introducing e-services. Considering the importance of competition from the informal sector, facilitating business registration could potentially contribute to formalisation, in particular if coupled with additional incentives, and be particularly beneficial to SMEs.

Policy recommendations

Establish a list of priority investment climate reforms and specific projects to assist their implementation with clearly identified timelines and responsible institutions. The plan should build on the existing strategic planning documents and diagnostics. It could be made publically available and periodically updated. The NEC and the ministry responsible for investment promotion could play a lead role in this regard, supported by high-level of government.

Strengthen regional component in investment promotion and develop terms of reference for co-operation across agencies at the central and sub-national level. Differentiate investment promotion according to regional comparative advantages. Use the EU Smart Specialisation framework to aid in this exercise. Rules for engagement with sub-national investment promotion bodies appear limited to processing of certified investment projects. For example, InvestBulgaria Agency (IBA) does not have a regional development mandate and lacks terms of reference for engaging with sub-national bodies. The development and implementation of such rules could help ensure complementarity of efforts and attraction of FDI into different regions.

Consider strengthening the aftercare services and technical capacity of IBA. While IBA performs all standard investment facilitation functions in the pre-establishment stage, it does not offer many aftercare services to firms (outside of certified investors). In particular, considering importance of skilled labour shortages in Bulgaria and potential spillover from SME-MNE links, the agency could consider developing such programmes. Specific projects, supported by international donors, could also help strengthen IBA’s monitoring and evaluation and prioritisation capacity.

Continue reducing administrative burdens. Administrative burden may be necessary for fair taxation, health, safety, environmental stewardship and other governmental commitments in line with the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises to improve social progress and the overall quality of citizens’ life (see Chapter 8). Still, from the perspective of business, administrative burdens can be a cost, delay and source of uncertainty with respect to operations and projects. Given the time it takes to establish a business in Bulgaria, these could be natural areas of focus in the short run. In the medium term, the government could consider whether establishing an one-stop solution for investment would help businesses deal with government regulations. In the long run, progress in improving the quality of regulations (discussed in the next chapter) will also help reduce the stock of burdensome requirements.

References

De Crombrugghe, A. (2019), “Supporting Investment Climate Reforms Through Policy Advocacy”, OECD Investment Policy Insights, www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/Investment-Insights-Supporting-investment-climate-reforms-through-IPA-policy-advocacy.pdf.

EBRD (2019), Bulgaria Diagnostic, www.ebrd.com/documents/comms-and-bis/country-diagnostic-paper-bulgaria.pdf?blobnocache=true.

European Commission (2018a), “Reshaping the functional and operational capacity of Sofia Tech Park”, Report by an Independent Panel of International Experts, www.ec.europa.eu/knowledge4policy/sites/know4pol/files/report_reshaping_the_functional_and_operational_capacity_of_sofia_tech_park_2018.pdf.

European Commission (2018b), “Country Report Bulgaria: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation No 1176/2011”, Commission Staff Working Document, SWD(2018)201.

European Commission (2019a), SBA Fact Sheet: Bulgaria, www.ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/38662/attachments/4/translations/en/renditions/native.

European Commission (2019b), “Country Report Bulgaria: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation No 1176/2011”, Commission Staff Working Document, SWD(2019)1001.

European Commission (2019c), Digital Government Factsheet 2019, www.joinup.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Digital_Government_Factsheets_Bulgaria_2019_1.pdf.

European Commission (2020a), “Country Report Bulgaria: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011”, Commission Staff Working Document, SWD(2020) 501.

European Commission (2020b), “Planned European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) 2014-12”, www.shorturl.at/lADGJ

European Commission (2020c), “Extra cash for COVID-19 measures in Bulgaria” www.ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/newsroom/news/2020/05/22-05-2020-extra-cash-for-COVID-19-measures-in-bulgaria.

European Commission (2020d), “European Structural and Investment Funds: Country Data for Bulgaria”, www.shorturl.at/imHOW.

Government of Bulgaria (2015), Innovation strategy for smart specialisation of the Republic of Bulgaria 2014-20, www.mi.government.bg/files/useruploads/files/innovations/ris3_26.10.2015_en.pdf.

Harding T. and B. Javorcik (2012), “Investment Promotion and FDI Inflows: Quality Matters,” Economics Series Working Papers 612, University of Oxford, Department of Economics.

Harding T. and B. Javorcik (2011), “Roll Out the Red Carpet and They Will Come: Investment Promotion and FDI Inflows,” Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society, Vol. 121(557), pp. 1 445- 1476.