Chapter 1. Towards sustainable development

This chapter provides an overview of economic and social development, and major policy developments in the environmental sectors, including climate, air, freshwater, waste and materials (biodiversity is covered in Chapter 2). Drawing on indicators from national and international sources, the chapter tracks progress towards achieving national goals and international commitments and targets, and looks at the environmental governance and management system. It also assesses the environmental effectiveness and economic efficiency of the environmental policy mix, including fiscal and economic instruments, regulatory and voluntary instruments, and investment in environment-related infrastructure. The chapter concludes with a reflection on opportunities for fostering a just and equitable transition to a green, low-carbon society.

1.1.1. Life in Norway

Norway is a northern European country with a small population of 5.4 million people and a large coastline of nearly 29 000 km, including fjords and bays. About 80% of Norway's population lives less than 10 km from the sea. Due to harsh climatic conditions, a large part of the country is unsuitable for settlement. Norway’s northern areas are sparsely populated, and are notably the traditional home of the Sami minority (about 20 500 registered Sami voters1). After Iceland, Norway has the second lowest population density in Europe. However, the large majority of its population lives in urban areas, with a dense population reaching nearly 2 000 people per square kilometre in the Oslo area. Norway’s population is growing slowly but steadily. It is expected to reach close to 6 million people by 2050 (Statistics Norway, 2021[1]). On average, the country also welcomes some 6 million tourists per year (2016-19, pre-COVID-19).

Life expectancy at birth is estimated at 83.2 years, higher than the OECD average. It is expected to rise another five to six years by 2050, increasing the share of people of retirement age. Norwegians have a generally good level of education and skills. Pupils in Norway scored above the OECD average in reading literacy, maths and science in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment. Girls largely outperformed boys. Norway is also among the most advanced countries in terms of gender equality. Nearly half of representatives elected to the Norwegian Parliament are women.

Norway’s population enjoys good health in general. The country has a well-developed health system with universal coverage and quality health services that are financially accessible to nearly all. Health spending per capita in Norway (about NOK 70 000 or USD 7 400) is about two-thirds higher than the EU average. Non-communicable diseases and social inequities are among the key public health challenges. The health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was significantly lower in Norway compared to other European countries. By November 2021, more than 70% of adults were fully vaccinated. However, another wave of infections hit Norway at the end of 2021, prompting the government to re-introduce containment measures.

Life satisfaction in Norway is high. The country regularly ranks among the top ten countries in terms of happiness, along with other Nordic countries. It also performs well in nearly all dimensions of well-being (Figure 1.1). Norwegians enjoy a good work-life balance and are comparatively “less stressed”. Only 3% of Norwegian employees work long hours, far below the OECD average of 11%. Norwegians also have a green lifestyle. In all, 91% of Norway’s people declared they enjoy outdoor activities (Statistics Norway, 2020[2]).

1.1.2. Economic performance

Norway has a small and open economy with a substantial petroleum sector. With USD 62 800 per capita in 2020, Norway is among the richest OECD countries. Income inequality in Norway is lower than in most advanced economies (OECD, 2021[3]). Like other Nordic countries, the country has an extensive system for social protection. While labour force participation has weakened somewhat over the past two decades, Norway’s employment rate is still largely above the OECD average.

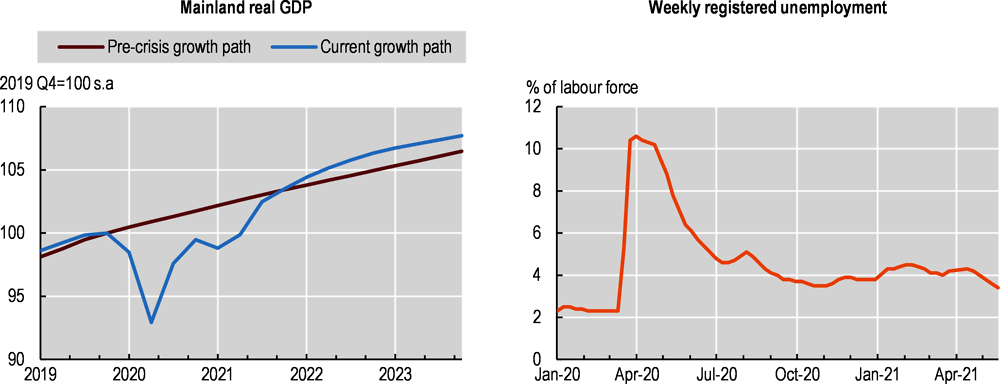

Mainland gross domestic product (GDP) annual growth contracted by 2.3% in 2020. The tourism and transport sectors were hardest hit. The government provided substantial support to people and businesses via several emergency and recovery packages (Section 1.7.1). However, Norway has been recovering comparatively quickly from the economic impacts of the global pandemic (Figure 1.2). Prior to the slowdown brought about by the Omicron variant, Mainland real GDP of Norway was projected to increase by 4.2% in 2022 (OECD, 2021[3]) (Figure 1.2). Provision estimates incorporating the slowdown suggest growth will be around 3.7%. The unemployment rate is set to fall further once the impact of the Omicron wave has passed.

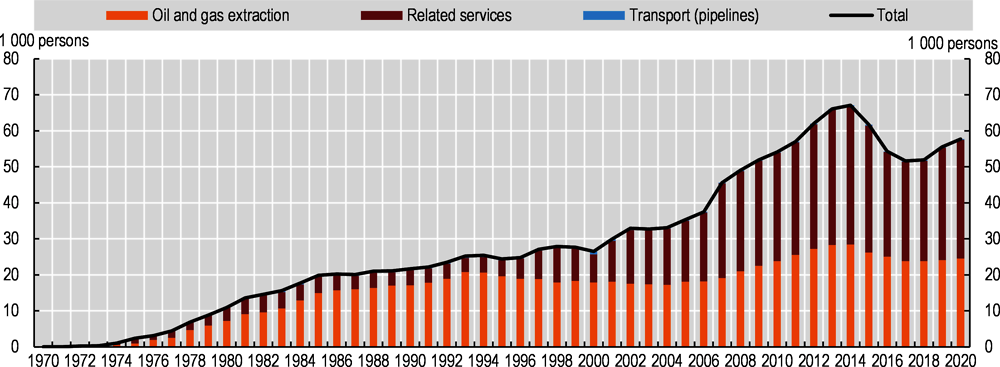

Norway’s economy has increasingly diversified. The service sector accounts for close to 66% of the economy, the industry sector represents 33% (including mining and construction) and the primary sector about 2%. The oil and gas sector accounts for a substantial share of economic activity. However, its share within national GDP is shrinking, from a peak of 25% in 2012 to 14% in 2021. To date, the petroleum sector represents 41% of total exports, 20% of total investments and 5.8% of employment (Ministry of Energy and Petroleum, 2022[4]). While a comparatively small player at the global scale (0.7% of world oil reserves and 1.7% of gas reserves), Norway is one of the world’s largest energy exporters. The vast majority of Norway’s crude oil exports is exported to other European countries. In 2020, Norway was the second largest exporter of gas within OECD member countries, following the United States. A network of subsea pipelines connects Norway to other European countries.

The European Green Deal and its climate framework will heavily impact Norway, notably in the medium and long term (2030-50) (European Commission, 2019[5]). According to EU projections, fossil fuels will still provide about half of the EU’s energy requirements by 2030. Natural gas is set to be phased out later and might still represent about 10% of Europe’s energy mix by 2050. Norway currently covers about a quarter of EU gas demand and is usually considered as an attractive and reliable business partner.

The government’s total net cash flow from the petroleum industry is estimated at NOK 272 billion in 2021 (about USD 31.6 billion). This is about NOK 90 billion (USD 10.5 billion) higher than the estimates of the National Budget 2022 thanks to high oil and gas prices (Ministry of Energy and Petroleum, 2022[4]). Despite the global recession, Norway’s main sovereign wealth fund grew by 8% in 2020. Created in 1990 to ensure sustainable, long-term management of Norway’s oil resources for current and future generations, the Government Pension Fund Global counted about NOK 12.3 trillion (USD 1.4 trillion) or close to NOK 2.3 million (USD 267 500) per inhabitant at the end of 2021. It is the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund.

Considering its large coastline of nearly 29 000 km and some 7 000 ships in Norwegian waters, Norway has a strong interest in developing a sustainable maritime sector (Section 2.5.2). Norway’s Climate Action Plan 2021-30, presented in a white paper to Parliament in 2021, includes a focus on green public procurement, green innovation and infrastructure. It aims at halving emissions from domestic shipping and fisheries by 2030, compared to 2005 levels. With a production of about 4 million tonnes per year, Norway is a net exporter of fish and fish products with a value of USD 10.8 billion (77% from aquaculture and 23% from fisheries) (OECD, 2021[6]). Over 30 000 people are employed in the seafood sector.

1.1.3. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals

For more than a decade, Norway maintained the top position on the Human Development Index. The country ranked seventh on the 2021 index of countries’ progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which was topped by three Nordic countries (Finland, Sweden and Denmark). Norway has already fully achieved six goals and is making good progress towards achieving four more (Figure 1.3). However, like many other OECD countries, the country still faces “significant or major challenges” for several goals, including climate action, sustainable consumption patterns and biodiversity protection. Most of the remaining challenges are related to the increase of environmental pressures.

In 2015, Norway adopted a national plan to implement the 17 SDGs. The government ensures annual reporting on the follow-up of the SDGs to Parliament (Storting). It is progressively mainstreaming implementation of the 2030 Agenda in sectoral policies and strategies towards 2030. According to the plan, all strategies, action plans and white papers are screened to ensure SDG-relevance, while the SDGs are systematically integrated into guidance and performance agreements with state agencies and institutions. Statistics Norway maintains a dedicated platform with facts and figures on Norway’s progress towards achieving the SDGs.

In 2020, the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, which is also in charge of regional development, became the national co-ordinating body for implementing the SDGs. It aims to promote local ownership and increase cross-sectoral co-operation. Municipalities, regional authorities and, more broadly, civil society now play a stronger role in the implementation of the SDGs. The 2021 National Action Plan promotes a whole-of-government approach and establishes measures to ensure better horizontal and vertical co-ordination, as well as stronger co-operation with the private sector, academia and civil society. Norway already submitted two comprehensive Voluntary National Reviews to the United Nations (2016 and 2021) (Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2021[7]) and another Voluntary Subnational Review (Hjorth-Johansen et al., 2021[8]).

At the regional level, the newly created county of Viken endorsed the SDGs as a holistic framework for the Regional Planning Strategy for a Sustainable Viken 2020-24 (OECD, 2020[9]). At the local level, 95% of municipalities have started working with the SDGs (Hjorth-Johansen et al., 2021[8]). Thirty municipalities monitored key performance indicators of the United for Smart Sustainable Cities. The Oslo SDG Initiative analyses transformations required for implementation of the 2030 Agenda. However, progress towards implementing the SDGs is uneven (OECD, 2021[10]). Some more advanced municipalities operationalised and integrated the SDGs into strategic plans and management processes. Others remain at the inception phase. Speed and progress in local implementation and ownership largely depend on three factors: the size of municipalities (larger ones are doing better), political commitment (higher in centrally located municipalities) and, to a less extent, budgetary constraints or capacity issues (Hjorth-Johansen et al., 2021[8]).

The role of local authorities in the implementation of the SDGs needs to be further strengthened. Counties and municipalities need to be fully involved in national decision making from early planning to monitoring and evaluation. At the same time, they must strengthen their capacity to work with the SDGs “strategically and systematically” (OECD, 2020[9]). The national government needs to further promote policy coherence, multi-level governance and multi-stakeholder partnerships to move beyond a goal-by-goal approach rooted in specific sectors. Inter-ministerial co-ordination between different policy areas could be improved. Specifically, ministerial departments should invest more in interdisciplinary expertise (e.g. internal mobility) and pay more attention to cross-sectoral spillovers to better integrate policies across sectors.

1.2.1. Key energy trends

Energy structure, intensity and use

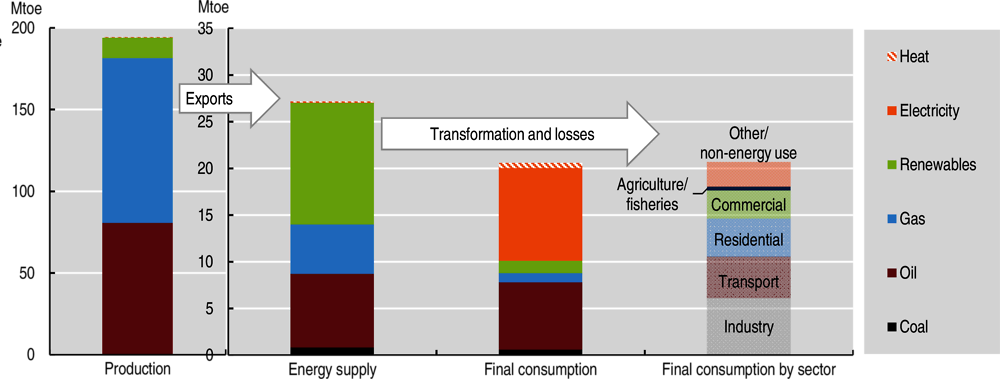

Thanks to the widespread use of clean electricity – primarily hydropower – Norway has one of the most decarbonised power sectors of Europe and of the OECD area (Figure 1.5). Primary energy supply decreased by 16.5% from a peak of 32.8 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) in 2013 to 27.4 Mtoe in 2019 (IEA, 2021[11]). Norway is energy self-sufficient with a surplus of renewable electricity in normal years. It has become Europe’s largest energy exporter (Figure 1.4).

Following recent increases,2 Norway’s oil production is set to increase until 2024 and then expected to decline by around 2% each year on average between 2025 and 2040 (IEA, 2019[12]). Gas production will peak slightly later around 2030. Production will first and foremost decline due to resource depletion rates rather than a planned transition (Sanner and Bru, 2021[13]).

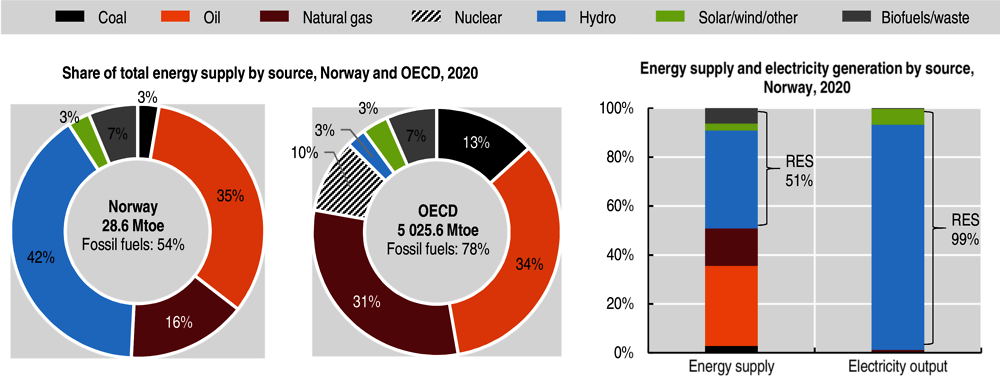

Oil, natural gas and coal together represented only about 50% of Norway’s total energy supply (TES) in 2020, compared to 78% in the OECD as a whole (Figure 1.5). Norway has reduced the share of fossil fuels since 2013 with a view to cutting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Coal made up about 3% of TES for the past few decades. In 2021, the government announced the closure of its only coal-fired power plant in Svalbard. At the same time, it released a new energy plan for Longyearbyen as part of its 2022 budget to increase the share of renewables in Svalbard. A remaining Russian coal mine is also set to close down. This is a highly symbolic, positive development with a view to protecting the Arctic area. Norway does not use any nuclear power in its energy supply.

The government’s 2021 White Paper “Putting Energy to Work” outlines objectives for a long-term value creation from Norwegian energy sources. The strategy aims at setting predictable framework conditions to help the country advance towards a low-carbon society. It defines four main goals: renewable energy resources for economic growth and job creation; electrification; establishment of new, profitable industries; and maintenance of a “future-oriented Norwegian oil and gas industry” (Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, 2021[14]). The paper outlines a series of pilot projects to develop new, cost-efficient, climate-friendly solutions and technologies in line with the objectives of its Climate Action Plan 2021-30 (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2021[15]). The government invests heavily in technological developments offered by offshore wind, renewable hydrogen, and carbon capture and storage (CCS).

However, the plan also foresees continued support for Norway’s petroleum exploration policy. This includes “regular concession rounds to ensure that new areas for exploration are made available to the industry” (Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, 2021[14]). This approach may exacerbate Norway’s petroleum lock-in and industrial path dependency (Kattel et al., 2021[16]). While the plan indicates that emissions from oil and gas production shall be cut by 50% by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050, continued oil exploration poses a risk of stranded assets given the global and, especially European, ambition of reducing fossil fuel use to reach net zero by 2050. There are concerns that it could slow down the shift from a fossil-driven to a fully green industry strategy (SEI et al., 2021[17]). On the other hand, Norway could play a crucial role as provider of transitional energy sources, notably gas, with a view to ensuring energy security in Europe and facilitating its clean energy transition. It is too early to assess the impact of the new energy strategy. The recent government change may also impact strategic orientations. The government is preparing a supplementary document. Both strategic documents were scheduled to be discussed in Parliament by mid-2022.

Renewables

Following Iceland, Norway has the second largest share of renewables, representing more than half of its energy mix and 99% of its electricity output (Figure 1.6). It overachieved its national target of a 67.5% share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption in 2020, in line with the EU Directive on renewable energy. Renewables represented a share of 26% in the transport sector, largely outperforming the 10% target set in 2012.

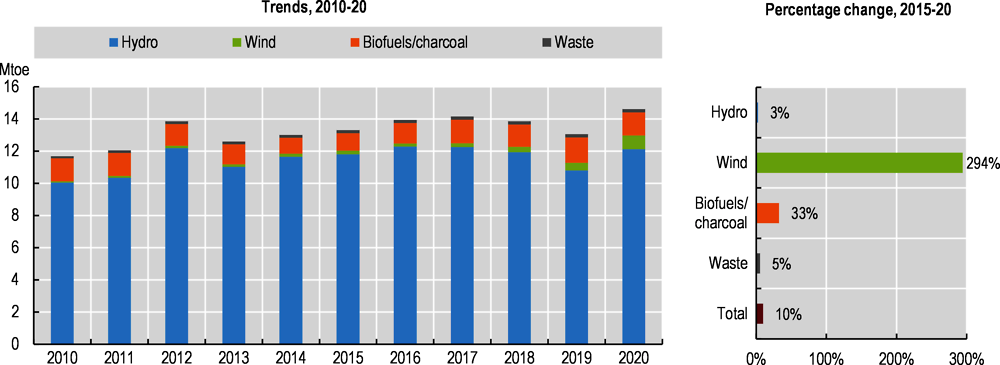

Norway is the largest hydropower producer in Europe and is among the largest worldwide. Hydropower represents the large bulk (90.2%) of Norway’s electricity production (Statistics Norway, 2021[18]). The country has significant hydropower reservoir capacity. The share of wind power has increased ten-fold from 2005 to 2019, representing about 4% of renewables (Figure 1.6). Norway installed about 1.5 GW of wind capacity in 2020. The government’s energy white paper outlines steps to facilitate offshore wind power, both floating and bottom-fixed installations (Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, 2021[14]).

Norway’s renewables sector is rapidly growing. The creation of new power lines to Germany and the United Kingdom will allow Norway to better integrate with the European electricity market. The joint Norway-Sweden green power support scheme has been the main policy instrument for increasing production of renewables. Created in 2012, the scheme has already passed its 2020 target (24.4 TWh) thanks to technological and market advancements. The governments of Norway and Sweden decided to end the support scheme by 2035, ten years earlier than planned.

Energy intensity and efficiency

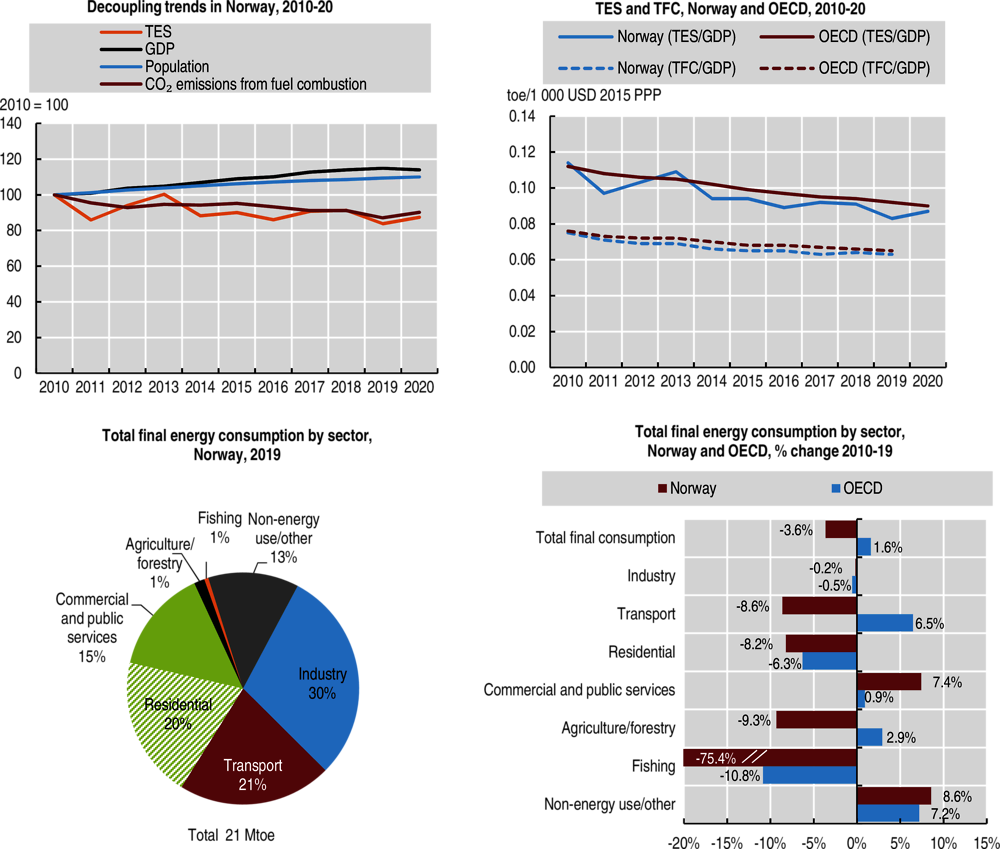

Norway has increasingly decoupled energy demand and related environmental effects from growth. Over the past decade, it has accelerated deployment of renewables and improved energy efficiency thanks to enhanced technology and electrification of the transport and residential sectors. Nevertheless, Norway’s energy consumption per capita, which historically has been among the highest in the OECD, is still slightly above the average. This is due notably to high energy consumption in the industry sector, as well as household heating needs due to the cold Scandinavian climate. Improving energy efficiency thus needs to remain a priority for such an energy-intense economy.

Norway’s total final energy consumption curve has been relatively flat over the years (Figure 1.7). The country is close to reaching the level of 2005. Further efficiency gains will allow Norway to pursue this downward trend despite increasing economic activity. Industry remains the largest energy-consuming sector but already consumes less than in 2005, primarily due to the continuing shift to services. The biggest reduction in fossil fuel energy consumption will come from the transport sector (Section 1.3.5). This is due in large part to Norway’s large-scale rollout of electric vehicles (EVs), which are about three times as energy efficient as internal combustion engine vehicles (IEA, 2021[19]).

The country has high energy-efficiency standards for building performance that were effective at reducing energy consumption and CO2 emissions from using energy, and in particular from heating dwellings. According to government calculations, Norwegian energy efficiency policies led to a reduction of 16 TWh between 2014 and 2020, largely exceeding the 2016 target of 10 TWh by 2030. In 2016, the government tightened threshold standards for new homes and major renovations to “passive house” level. As of 2020, it became the first country that formally prohibited use of fossil oil for heating in existing buildings and in new buildings altogether. Energy consumed by the residential sector is thus increasingly carbon-free. Moreover, there is scope for greener housing construction and building materials (OECD, 2022[20]). Building homes, and associated production and disposal of building materials, has significant environmental costs. A stronger focus on the life cycle of buildings could help Norway further decarbonise the building sector (e.g. reduced use of materials, use of low-carbon materials, re-use of materials).

1.2.2. Atmospheric emissions and air quality

Norway’s pollutant emissions and intensities of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen oxide (NOx), sulphur oxide (SOx) and black carbon have all decreased over the past decade. Norway reached its air emission targets for 2020 (Figure 1.8) except for ammonia (NH3) and a recent increase in emissions of non-methane volatile organic compounds due to increased use of disinfectants during the pandemic. The largest emissions of black carbon originate from the transport sector and wood combustion in residential heating; both emission sources have been considerably reduced. While Norway had failed to meet the Gothenburg Protocol target on NOx emissions in 2010, the country reduced its NOx emissions by 29% from 2005 to 2020 (Norway Statistics, 2021[21]). NOx emissions related to road transport achieved an above-average reduction of 40%. Moreover, the NOx tax and the Business Sector’s NOx Fund contributed to reducing NOx emissions in the business sector, while supporting the phasing-in of new technology. Both measures helped Norway meet the 2020 Gothenburg Protocol target.

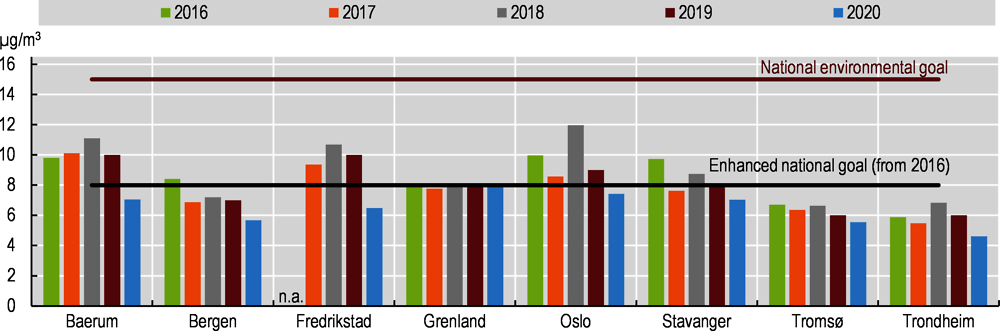

Norwegians enjoy good overall air quality (Figure 1.9). Premature death attributed to PM2.5 exposure in Norway is less than one-third the OECD average. Norway complies with EU directives on air quality standards and will continue to follow the EU zero pollution agenda closely. In addition, the country has set more ambitious local and national targets, supported by excellent nationwide air quality monitoring services. Norway’s four major cities rank in the top 20 of the European City Air Quality Index.

Nevertheless, nearly all larger cities in Norway face localised air pollution problems and periodic worsening of air quality with high peak PM10 concentrations during winter and into spring. Thanks to measures such as the zero-growth goal, EVs and replacement of wood stoves, local air quality in urban areas is expected to further improve in the coming years. Fees for studded tyres, an important source of airborne particulates, helped reduce their use in urban areas. Beyond health impacts and noise, air pollution also threatens biodiversity, which requires targeted solutions for protected areas. For example, Parliament adopted a resolution in 2018 to stop emissions from cruise ships and ferries in world heritage fjords by 2026 at the latest. This would transform these fjords into the world’s first zero-emission zones at sea.

1.2.3. Water resources management

Water quantity and quality

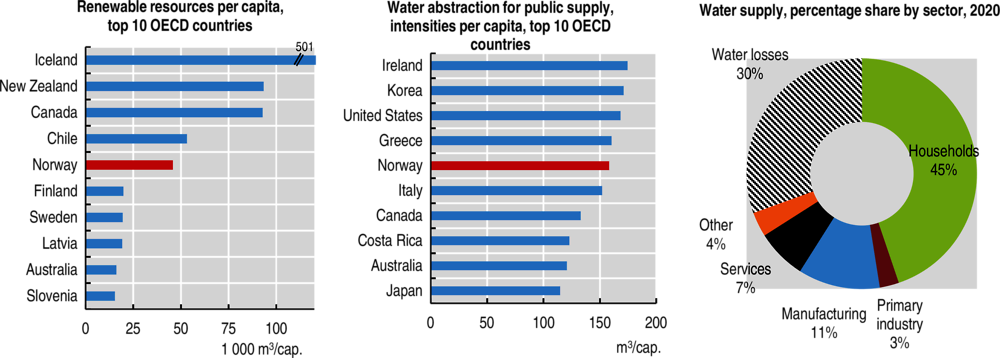

Norway has abundant water resources and is endowed with a large number of lakes and river habitats. This is why the intensity of water use (withdrawal as a percentage of available resources) continues to be low. At the same time, water abstraction for public supply (intensities per capita), is among the highest within the OECD area, due to high water consumption and significant water losses (Figure 1.10).

Freshwater ecosystems are threatened by human activities (e.g. pollution and hydropower production) and other pressures such as acid rain, the spread of alien species and high numbers of salmon lice. Fish farming and lice are identified as the main threats to wild salmon in the 2021 Red List for Species. More than two-thirds of Norway’s largest rivers are zoned for hydropower production, which was partly responsible for reducing the salmon population in affected streams. According to the Norwegian Environment Agency, river regulation schemes have negatively affected 23% of Norway’s salmon rivers. However, several initiatives aim to reduce these negative impacts. Agriculture, municipal sewage and fish farming are the main sources of water contamination in Norway. Norway has one of the highest nitrogen balances per hectare among OECD countries due to widespread application of fertilisers (OECD, 2021[22]).

Norway has implemented the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) since 2007 with a view to achieving good ecological and chemical status for all inland, transitional and coastal waters and groundwater bodies. Norway counts 15 river basin districts (RBDs), including cross-border basins that share water courses with Finland and Sweden. Each RBD has its own management plan, including environmental objectives for water bodies and associated action plans. Norway completed – under formal WFD obligations – its first full cycle of river basin management plans from 2016-21 and will start a new one from 2022-27.3

According to national assessments, about one-third of Norway's freshwater bodies do not meet the WFD criteria for good ecological status, including 12% categorised as “heavily modified” (Environment Norway, 2021[23]). Norway is doing overall better than most European countries, but the ecological status of water bodies has deteriorated over the past decade (Table 2.1). Ecological conditions are generally better in central and northern parts of Norway, and poorer in more densely populated areas of the south. Norway needs to redouble efforts to reach its target of restoring 15% of degraded ecosystems by 2025, including water-related ecosystems. While Norway has made progress towards integrated water resource management, it still has a way to go to fully meet its obligations under the WFD.

Drinking water supply

The supply of drinking water is good: nearly 90% of Norwegians have access to treated drinking water from waterworks with high quality standards. Surface water provides 90% of drinking water. About half a million people (or 10%) get water from private wells or other small water plants for which the quality is largely unknown. Leakage from the drinking water supply system is estimated at 30% (Environment Norway, 2021[23]). This represents not only a significant loss of water resources but also a potential risk for microbiological contamination in drinking water. Water supply systems are often more vulnerable in small municipalities, notably in terms of water supply stability and the ability of drinking water utilities to prepare and respond to emergencies (bedreVANN and Norsk Vann, 2020[24]). Information on drinking water quality could be made accessible directly on websites of municipalities. This would enable consumers to easily consult relevant information on their drinking water sources as well as inspection reports.

Wastewater treatment

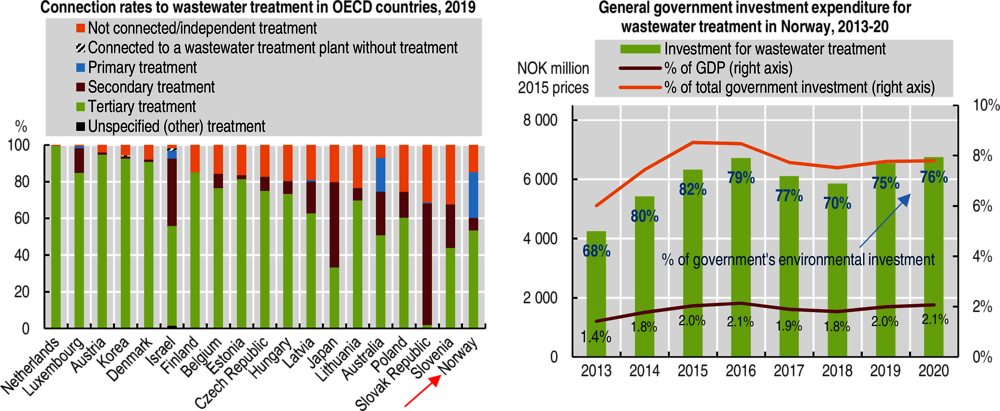

Most people are connected to municipal wastewater systems. However, only 60% of Norway’s population is connected to advanced wastewater treatment plants with biological or chemical treatment methods. This is one of the lowest shares in the OECD area (Figure 1.11). The share of primary wastewater treatment is particularly high in remote areas.

Norway counts about 2 700 municipal wastewater treatment plants (Norwegian Environment Agency, 2021[25]). The county governor is the pollution control authority for about 330 larger plants that treat wastewater from the vast majority of the population (3.9 million people). Meanwhile, municipalities manage most of the small wastewater treatment plants, which serve a small percentage of the population. In addition, some 350 000 treatment plants deal with wastewater from about 800 000 people who live in sparsely populated areas. New treatment systems are also being built for individual houses and cabins, while other buildings are connected to the public sewerage system.

Many municipalities have sewage systems that do not comply with pollution regulations and permits. According to national statistics from 2020, more than half of the population was connected to wastewater facilities that do not comply with pollution permits (Onstad, 2021[26]). This calls for regular inspections and the use of coercive fines.

As noted in the previous OECD EPR of Norway (OECD, 2011[27]), the country’s ageing water infrastructure requires urgent upgrades. It also needs to adjust to new climate challenges, such as increased precipitation, floods and rising sea levels. The rate of infrastructure improvement has been slow despite quite substantial investment (Section 1.6). There is scope for improving operational efficiency of water services and co-ordination between different administrative levels.

1.2.4. Transition to a resource-efficient economy

Waste management

Norway is not on track to meet its objective of decoupling waste generation from economic growth. Waste generation in Norway reached a record high in 2019. According to national statistics, Norway generated 12.2 million tonnes of waste in 2019 (+3% compared to 2018). At the same time, it recovered 71% of waste and recycled about 41% of collected municipal waste; recycling remained fairly stable overall. The construction sector bypassed the industry sector for the largest waste volume (26%). While the industry managed to considerably reduce waste generation, the shares of private households and service industries have been steadily increasing, representing 20% and 18%, respectively (Figure 1.12).

The average Norwegian produced 772 kg of municipal waste, among the highest amounts in Europe (OECD Europe average = 499 kg per capita). However, the definition of municipal waste has been changing over the years, which makes it difficult to compare data. The Waste Management Plan for 2020-25 includes a waste prevention programme and proposals for changes in waste infrastructure to prepare for tightened directives within the EU Zero Waste Strategy. The government reiterates its national goal that growth in waste generation should be significantly lower than economic growth. Some municipalities also prepared local waste management plans.

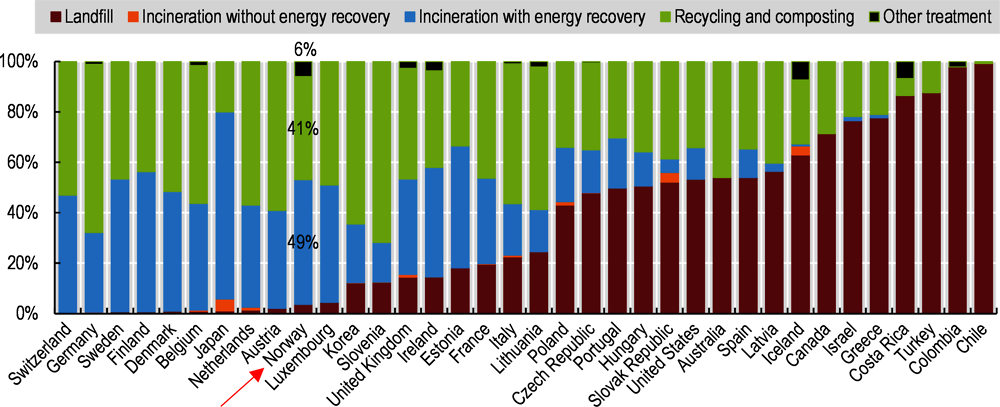

Norway’s waste treatment profile is similar to its Scandinavian neighbours, Finland and Sweden; nearly half of Norway’s municipal waste is treated by incineration with energy recovery, while landfilling has almost disappeared following a landfill ban in 2009 (Figure 1.13). The country will need to significantly increase its recycling capacity. Norway transposed the EU directive of 2018 and still has a way to go to prepare at least 55% of municipal waste for re-use or recycling by 2025; 60% by 2030 and 65% by 2035.

The country has excellent waste treatment facilities, with cutting edge technology for waste sorting. While more flexible regulations are needed, extended producer responsibility schemes and better incentives are key to creating demand for secondary raw materials, notably in the construction sector. Technical building standards need to be adjusted to enable increased use of recycled building materials.

Bio-waste collection in Norway was introduced in the 1990s. Today, about 70% of Norwegians live in municipalities with source separation of bio-waste and door-to-door collection of food waste. The collection rate from households is estimated at 69%. To fill the gap, collection of “household-like” food waste could be made mandatory as suggested by the Environment Protection Agency in 2017. Collected food waste is increasingly used for biogas production. For example, a biogas plant has been producing green fuel for Oslo’s city buses since 2014.

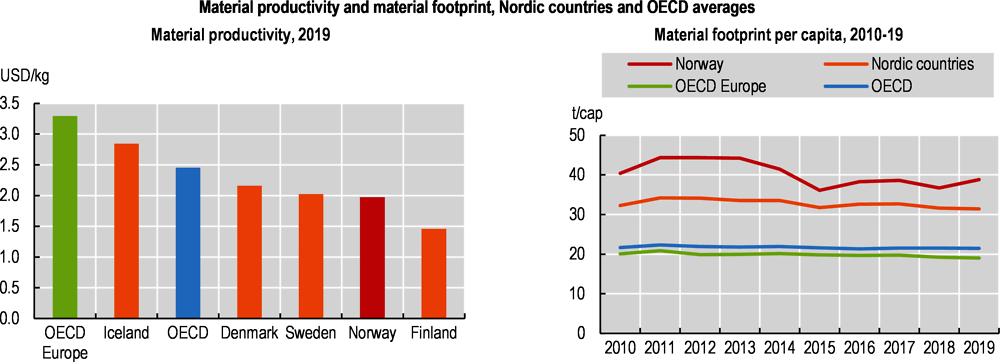

Circular economy and global material footprint

Promoting sustainable consumption patterns is a key challenge for Norway. The country has one of the world's highest material consumption rates, a high material footprint per capita and low material productivity (Figure 1.14). The government released its first strategy for developing a green, circular economy in July 2021. The strategy sees the transition to a circular economy as an opportunity to foster value creation and sustainability (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2021[28]). It has broad scope and largely applies the new EU Circular Economy Action Plan 2020 (European Commission, 2020[29]). The linear pattern of “take-make-use-dispose” does not provide producers with sufficient incentives to make their products more circular. Only a small share of products is cycled back into the Norwegian economy (Circular Norway, 2020[30]).

As the European Union sets global standards in product sustainability, Norway could benefit from a stronger focus on life cycle thinking, eco-design, the right to repair, etc. Policy makers need to create an enabling environment to facilitate the transition towards a circular economy. Typically for many developed economies, material footprint originates in part from outside Norway. A more holistic strategy would allow Norway to better understand and consider global environmental impacts. Actions should tackle all economic areas to reduce Norway’s material footprint (e.g. construction, forestry and wood products, energy transition, circular food systems). They should focus on reducing absolute levels of resource consumption. This involves further educating and empowering consumers to make informed decisions (e.g. use of sustainability labels).

1.3.1. Main policies and measures

Norway is a frontrunner in advancing climate action. Already in 2007, Norway pledged to be the first country to become carbon-neutral by 2050. Parliament approved a proposal in 2016 to accelerate carbon emission cuts and carbon offsetting to reach this ambitious goal by 2030. In parallel, Norway also committed to zero deforestation, making it the first nation to ban public procurements that contribute to rainforest destruction. In 2021, Norway’s government presented the comprehensive “Climate Action Plan for the Transformation of Norwegian Society as a Whole by 2030” as a way towards a carbon-neutral future (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2021[15]).

Norway’s climate policy builds on the objectives of the global climate agenda. The country participates in the implementation of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. Participation in the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) was a major factor in achieving Norway’s commitments under the Kyoto Protocol (2008-12 and 2013-20), along with carbon credits under the Clean Development Mechanism and domestic measures. The 2017 Climate Change Act, the 2020 Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement and the Climate Action Plan 2021-30 lay out the framework of Norway’s climate action. The government provides annual reporting on both mitigation and adaptation efforts to Parliament.

Norway defined the following climate goals:

Climate target for 2030: reduce GHG emissions by at least 50% and towards 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels (enhanced target, initially: 40%).

Climate neutrality by 2030: emissions must be offset by climate action through emissions trading systems or other international co-operation.

A low-emission society by 2050: reduce GHG emissions by at least 90-95% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels (enhanced target, initially 80-95%).

These national targets are among the most ambitious worldwide, going beyond the commitments of many other OECD countries. They are closely aligned with the enhanced ambition of the EU-wide 2030 Climate and Energy Framework under the EU Green Deal (European Commission, 2019[5]) (Table 1.1). Moreover, many counties, cities and municipalities have set net zero goals and contribute to fulfilling Norway’s national ambitions. The city of Oslo has an ambitious climate action plan and climate budget covering all relevant sectors. Norway benefits from broad political consensus and popular support for climate action. According to one report, 61% of Norwegians believe that on a global scale their country will succeed in reducing climate gas emissions, while 39% believe that climate change is the greatest challenge of our time (Kantar, 2020[31]).

June 2016: Government ratifies the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.

June 2016: Parliament adopts climate neutrality target for 2030.

June 2017: Climate Change Act sets legally binding long-term goal of a low-carbon society by 2050.

October 2019: Government adopts EU agreement to expand co-operation for 2021-30, notably covering non-ETS sectors.

February 2020: Government submits enhanced Nationally Determined Contribution to the UNFCCC.

September 2020: Government launches Longship project on CCS (Box 1.6).

January 2021: Government presents Climate Action Plan 2021-30.

April 2021: Government launches Strategy for Climate Adaptation, Prevention of Climate-related Disasters, Fight against Hunger.

1.3.2. Close co-operation between Norway and the European Union

Norway plans to fulfil its climate commitment in close collaboration with the European Union, drawing on its long-standing climate partnership within the European Economic Area (EEA) Agreement (Table 1.1). Norway has participated in the EU ETS since 2008, which covers about half of Norwegian emissions. Moreover, the European Union, Norway and Iceland adopted a new co-operation agreement in 2019, covering 2021-30 and expanding the scope of the climate partnership. Under the EU Effort Sharing Regulation, Norway commits to reduce GHG emissions in sectors outside the scope of EU ETS (agriculture, transport, waste, building sectors and small industrial/commercial facilities) by 40% compared to 2005 levels. Norway also committed to applying the no-debit rule under the EU regulation on land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF). By participating in all three pillars of EU climate policies, Norway contributes to achieving the EU’s ambition to become the first climate-neutral continent.

1.3.3. Greenhouse gas emissions trends and projections

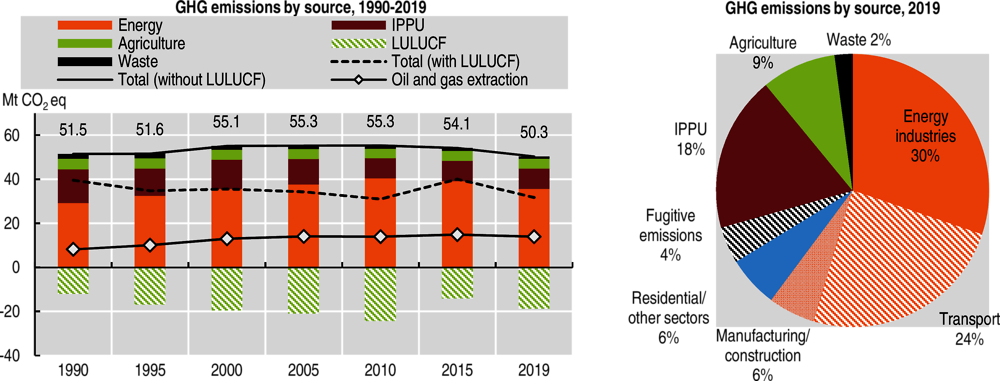

Norway is a small GHG emitter with absolute emission levels similar to other Nordic countries. Despite its small population size and significant oil and gas production, Norway’s emission level per capita (9.4 tonnes of CO2-eq) remained below the OECD average of 11.3 tonnes in 2019. In terms of emission intensity, Norway recorded one of the lowest levels in the OECD area (OECD, 2022[32]). Similar to other OECD countries, energy industries, dominated by oil and gas production, are the largest emitting sector (Figure 1.15). They contribute to nearly a third of the country’s GHG emissions. Despite targeted climate action, the transport sector still contributes about a quarter of Norway’s emissions. It is followed by industrial processes and product use, agriculture, residential and other sectors and fugitive emissions from fuel. The structure of emissions is expected to remain substantially unaltered by 2030 (Figure 1.16).

Norway has decoupled emissions from GDP growth. Since 1990, Norway’s emission levels varied between 47.5 million (1992) and 56.9 million tonnes of CO2-eq (2007) (Figure 1.15). After peaking in 2007, domestic GHG emissions have declined, albeit more consistently in the second half of the 2010s. In 2020, they were about 10% lower than in 2010 but only about 4% lower than in 1990 (Statistics Norway, 2021[33]).

The starting point for emissions reductions in Norway was low because its energy mix was already largely decarbonised, leaving few remaining quick wins. The expansion of offshore oil and gas resources over the past decades also contributed to increasing GHG emissions (Figure 1.15). These emissions have been relatively decoupled from production since 2016. The Norwegian petroleum industry has comparatively high environmental and climate standards. Many oil and gas companies committed to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Despite the economy-wide decarbonisation efforts, Norway is far from reaching its initial goal of cutting 40% of emissions by 2030, and even more so from its enhanced goal of 50% and towards 55%. According to projections of the 2022 National Budget (Ministry of Finance, 2021[34]), Norway will emit around 41.2 million tonnes of CO2-eq by 2030 (Figure 1.16). This represents a reduction of 20% of emissions compared to the 1990 level. These estimates do not yet include measures of the Climate Action Plan 2021-30 or the effects of Norway’s participation in the EU ETS. There is also some uncertainty regarding calculation methods of the effects of Norway’s EU ETS participation. However, Norway will likely face a gap to achieve the 2030 emissions reduction target.

The government intends to accelerate domestic emission cuts. The Climate Action Plan 2021-30 sets out detailed targets and policy measures for each sector with a view to reaching a 45% reduction in the non-ETS sector (exceeding the EU target of 40%). However, promoting low-carbon technologies is costly in the short term. Norway needs to further analyse impacts of policies to improve the cost effectiveness of existing measures (Section 1.5.3). With high marginal costs of reducing domestic GHG emissions, the purchase of foreign emission credits often makes economic sense. Moreover, Norway’s large forest areas – about a third of total land area – provide a substantial carbon sink, representing nearly half of annual GHG emissions. Natural carbon stocks of mainland Norway are more than twice as large as the average for the world’s land areas. Norway is on track to increase forest cover and enhance carbon sinks (Climate Action Tracker, 2021[35]). Ongoing efforts are needed.

1.3.4. Norway’s global carbon footprint

As Norway is a small and open economy, the focus on national GHG emissions alone provides only a partial picture of Norway’s global carbon footprint. While the country is not legally responsible for GHG emissions outside Norway, implicit emissions from its oil and gas used abroad are significant. However, as most Norwegian oil and gas are exported to Europe, embodied emissions are largely covered by ETS or non-ETS European carbon-pricing mechanisms (OECD, 2022[20]).

In today’s interconnected world, as do other OECD countries, Norway needs to look for a more coherent approach to climate and environmental policies. Such policies should better reflect the country’s global carbon footprint and spillover environmental impacts. These impacts include transboundary pollution flows; environmental impacts embedded in traded goods and services; and exploitation of international common pool resources.

International institutions are developing indicators and new metrics to better capture international spillover effects. Norway could usefully develop national indicators using environmentally extended multi-regional input-output, material flow analysis and life cycle assessment to better understand its economy-wide global footprints. This could help better track the environmental impact of trade. Such results could inform environmental impact assessments (EIAs) during the permitting and licensing process.

1.3.5. Decarbonising transport

Transport demand is growing, and emission cuts in the transport sector thus play a key role in achieving Norway’s climate and environmental goals. It is difficult to make robust projections on future transport demand. This is especially the case given uncertainty related to long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. teleworking, demand for air travel, reduction of unnecessary travel, challenges related to social distancing in public transport, etc.).

Norway has set ambitious transport decarbonisation policies. Its Climate Action Plan 2021-30 sets out key objectives for the transport sector, which aims at halving emissions in 2030 compared with 2005 levels, beyond the EU target of 40%. The government’s transport goals, strategies and priorities are detailed in the National Transport Plan 2022-33 (Ministry of Transport, 2021[36]). A broad range of economic instruments and regulatory instruments is used to decarbonise all transport sectors (Section 1.5).

Norway has comparatively high levels of short-distance, infra-national air traffic due to the large number of fjords, offshore islands and sparsely populated mountainous areas. Domestic aviation contributed to 9% of GHG emissions in the transport sector (Figure 1.17). The EU ETS has so far been the main policy instrument for the aviation industry.

For a long time, the rapidly growing demand for mobility has outpaced progress in decarbonising the transport sector. Transport emissions peaked in 2012 (15 million tonnes of CO2-eq) and decreased by 8.9% from 2005 to 2019. The impacts of Norway’s EV rollout and related emission cuts became strongly visible as of 2016 (Figure 1.17). According to national projections, transport emissions are projected to decrease by nearly one-third from 2019 to 2030. Nevertheless, Norway needs to further accelerate electrification of the transport sector to halve transport GHG emissions by 2030.

1.3.6. Towards sustainable transport systems

Road transportation remains the privileged mode in Norway. In 2020, of 5.7 million registered vehicles, some 2.8 million were passenger cars (Statistics Norway, 2021[37]). Norway has more vehicles than people. It will be important to take a broader approach to electric mobility and promote structural changes towards shared mobility and integrated sustainable services.

The implementation of the zero-growth goal through Urban Growth Agreements has helped reduce car traffic volumes, cut emissions and improve the quality of life in Norway’s major cities. Such agreements should be rapidly extended to medium-sized cities and smaller urban areas.

The National Transport Plan sets a long-term goal of a 20% share of cycling in urban areas and 8% nationwide. Some 173 km and 322 km of cycle-friendly infrastructure was created in 2019 and 2020, respectively. However, Norway does not have a targeted strategy to translate its national commitment into practice; investment priorities remain mostly focused on the road sector. While acknowledging specific needs of its sparsely populated areas,4 Norway could make it a stronger priority to develop more and cheaper alternatives to private vehicle use. The government could further re-orient investments in more sustainable transport systems and public transport. This would also bring broader societal benefits for people’s health while improving accessibility.

Despite its great achievements in the EV sector, Norway needs to redouble efforts and make more structural changes to establish sustainable transport systems to meet its 2030 target. This involves promoting behavioural changes, placing a stronger focus on shared mobility services and shifting from increased mobility towards improved accessibility. The rail system needs to be further modernised and become a cheaper alternative to road and air transport. Airport expansion is counterproductive to reducing GHG emissions and environmental concerns need to be better reflected in any new plans. This is an opportune moment to rethink mobility and develop a socially fair and spatially balanced transport system.

1.3.7. Climate change adaptation

Annual mean temperature for mainland Norway has increased by about 0.8°C and annual precipitation by nearly 20% over the past 100 years (OECD, 2013[38]). Future climate risks mainly include increasing exposure to extreme weather events and related risks, as well as multiple threats to ecosystems. Northern Norway is likely to experience the greatest changes in annual mean temperature, where the median warming estimates varies between 2-6°C by the end of the century (Hanssen-Bauer et al., 2017[39]).

Norway has so far proven to be relatively climate resilient. According to the Global Climate Risk Index 2020 (Eckstein et al., 2019[40]), Norway was among the least climate-vulnerable countries in terms of fatalities, material damage and related economic losses (ranked 94 in 2018). The country has developed early warning systems drawing on various specialised agencies and monitoring programmes. It has good capacity to adapt to climate-related hazards and natural disasters.

The government facilitates knowledge sharing to make society less vulnerable to climate change via an online platform (Klimatilpasning.no) targeting municipalities. Adaptation is an integral part of municipal responsibilities. Local authorities can draw on planning guidelines aimed at improving coherence in the application of instruments in local adaptation work. KLIMAFORSK, a ten-year climate programme of the Research Council of Norway, aims to raise knowledge and awareness of climate change. Norway also contributes to the EU-wide knowledge-sharing platform Climate-ADAPT and to the implementation of the EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change.

1.4.1. Institutional framework

Norway is a unitary state with an administrative structure composed of three levels: national (central government), regional (counties) and local (municipalities) (Figure 1.18). Municipalities and county authorities have the same administrative status. The central government supervises municipal and county administrations. The county governor is the main representative of the central government in charge of supervising local authorities. Governors can also receive appeals against many municipal decisions. This makes governors an important link between local and national levels.

All decisions on environment-related legislation and taxation are made by the 169-seat unicameral Parliament (Storting), which is elected every four years. The Norwegian government is responsible to Parliament. Reports on the state of the environment are included in the annual state budget for the Ministry of Climate and Environment. The Sami Parliament (Sametinget) promotes the language and the interests of the Sami population.

Local authorities are responsible for most aspects of environmental management. Municipalities manage local pollution control, while county governors and the Norwegian Environment Agency control pollution at the regional and national levels, under the guidance of the Ministry of Climate and Environment. Academics and advisory bodies are closely involved in policy formulation. The short distance between research and policy-making bodies is a clear asset of the Norwegian system. Policy making is transparent and public consultations are conducted for all draft laws. Norwegian citizens place a high level of trust in public institutions and the judiciary system in particular. Norway reported the second highest confidence in national government among OECD members in 2020 (83%, compared to 68% in 2006) (OECD, 2021[41]).

With about 700 000 inhabitants, the capital city of Oslo is the largest municipality and also has the status of a county. Oslo has a dedicated climate strategy along with comprehensive plans for land use, housing and transportation for the whole Oslo area (City of Oslo, 2020[42]). However, only ten municipalities have more than 50 000 inhabitants and most have fewer than 5 000.

The government initiated a major reform in 2014 to strengthen local democracy by transferring power and responsibility to larger, more robust municipalities and regions. The reforms aim to secure professional welfare services throughout the country, develop sustainable entities and advance local planning. In 2017, the government decided to reduce the number of counties from 19 to 11 and encouraged municipalities to merge voluntarily. In line with the European trend of municipal amalgamation, the number of Norwegian municipalities has progressively decreased since the early 1960s. As of 2020, Norway is divided into 11 counties and 356 municipalities (down from 428). The mergers created six new counties. With more than 1.2 million inhabitants, the new county of Viken is the most populous, accounting for nearly a quarter of total population. Some county mergers have been controversial, but counties may be able to undo them.

Norway needs to capitalise on existing spatial development dynamics. This can help improve the quality of public services and promote balanced regional development. While mergers provide opportunities for efficiency gains, they also need to make sense for people and maximise societal well-being. Building trust and improving well-being are both critical prerequisites to gain social acceptance for territorial reforms. Cost-benefit analysis and ex post evaluations of recent mergers could help better understand short- and long-term impacts and inform a healthy public debate about the future.

National government and horizontal co-ordination

Norway was among the first countries to establish a Ministry of Environment in 1972 (renamed the Ministry of Climate and Environment in 2014). Over time, it has developed an extensive framework for environmental policy. The ministry initiates, develops, implements and monitors measures to protect the environment. It also seeks to mainstream green policies and influence sectoral ministries. In addition, it co-ordinates the government’s environmental policy objectives. Its core tasks include formulating government policies; preparing white papers, national plans and guidelines; and issuing regulations. A large number of decentralised advisory bodies and implementation agencies support its work (Box 1.2).

Many sectors contribute to achieving Norway’s environmental objectives by incorporating environmental concerns and measures. The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy manages energy resources (oil, gas, hydropower and renewables), while the Ministry of Transport implements sustainable mobility policies. For its part, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food is responsible for sustainable agriculture and forest management. The Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development oversees many management tasks under the Planning and Building Act and has shared responsibility for EIAs. It also co-ordinates the government’s work on sustainable development.

Decision making in Norway is strongly consensus-oriented, benefiting from close ministerial co-operation. The country also uses extensive informal co-ordination between cabinet and parliamentary committees and party organisations, which further smooths the decision-making process. A line ministry usually leads on a specific process and co-ordinates with other relevant ministries and stakeholders. If other ministries agree, the government can move forward with a new law, white paper or guidelines. In case of disagreement, a consensus is built in cabinet meetings. The recent transfer of some agencies to the Ministry of Climate and Environment reflects Norway’s commitment to bring stronger attention to climate and environmental issues (Box 1.2).

Enova

The Trondheim-based state-owned enterprise helps reduce GHG emissions and develop new energy and climate technology. In 2018, the responsibility for Enova was transferred from the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy to the Ministry of Climate and Environment. This reflects Enova's growing importance as a climate instrument and favours a more holistic approach to climate policy development.

Norwegian Environment Agency

The Norwegian Environment Agency plays a key role in ensuring implementation of environmental policies, managing nature and preventing pollution. It serves as Norway’s regulatory authority, conducts inspections, monitors the state of the environment and advises the ministry on key environmental challenges. It was created in 2013, following a merger of the former Climate and Pollution Agency and the Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management, and is professionally independent. The Norwegian Nature Inspectorate (SNO) is part of the agency.

Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre

The Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre develops and spreads knowledge on biodiversity. Work draws on close co-operation with the scientific community, as well as with policy makers, managers and other data users.

The Norwegian Meteorological Institute (MET Norway)

Created in 1866, MET Norway is Norway’s oldest environmental institute. It provides weather forecasts, climate monitoring, emergency preparedness and research in meteorology, oceanography and climatology. In 2018, MET Norway was transferred from the Ministry of Education and Research to the Ministry of Climate and Environment.

Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI)

Established in 1948, the Norwegian Polar Research Institute is a directorate under the Ministry of Climate and Environment that focuses on environmental management needs in the Arctic and Antarctic. It is in charge of scientific research, mapping and environmental monitoring of the polar regions, and operates research stations in Svalbard and in the Antarctic.

Directorate for Cultural Heritage and Norwegian Cultural Heritage Fund

The directorate acts as the advisory and executive body of the Ministry of Climate and Environment for the management of the cultural environment. As of 2020, counties are in charge of most management tasks in the cultural environment area. The Norwegian Cultural Heritage Fund is a subordinate agency of the Department of Cultural Heritage.

Svalbard Environmental Protection Fund

The fund’s resources initiate promising projects to conserve and protect the rich natural environment and cultural heritage on the Svalbard islands in line with the Act on Protection of the Environment in Svalbard.

Norwegian Centre against Marine Litter

The centre was established in 2018 as a subordinate agency of the Ministry of Transport, known as Norwegian Centre for Oil Spill Preparedness and Marine Environment. From January 2022, it became a government agency under the Ministry of Climate and Environment. It is located in northern Norway on Lofoten Island. As of 2022, it will provide, among others, expertise on marine litter prevention and management, and will co-ordinate and provide financial support for clean-up activities.

Source: Country submission.

Local government and vertical co-ordination

Norway applies the subsidiary principle to perform tasks at the lowest effective level. A general trend towards decentralisation has been observed over the past decades. Norway has emphasised local democracy, acknowledging that challenges and opportunities vary from place to place. It has highlighted the value of locally tailored solutions in the context of great geographic dispersion.

Every four years, the central government sets national expectations regarding regional and municipal planning with a view to promoting sustainable development throughout the country. The 2019-23 national expectations document (Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2019[43]) provides an overview of the relevant central government planning guidelines to support county and municipal planning (Section 2.5).

Counties are mainly responsible for regional development policies, secondary education, regional roads and environmental issues, including those related to the cultural environment. The county municipality, governed by a council, is the democratically elected body for the region. Responsibilities of county municipalities are largely defined by government rules and regulations. Recently, they took over all tasks related to secured outdoor recreation areas in order to pool resources and promote more efficient and predictable management. The new government intends to further strengthen their role as a community developer.

Municipalities provide a large number of welfare services and are responsible for most aspects of environmental management. They also increasingly participate in the management of protected areas and play an important role in reaching Norway’s ambitious climate goals. Some municipalities have a dedicated environment officer.

Despite large differences in geography, area and population size, municipalities have the same rights and responsibilities. Smaller municipalities often have limited capacity and face many challenges to fulfil all required functions. Differences in implementation capacity, the influence of local interests and greater institutional autonomy have led to uneven application of environmental regulations and national guidelines. Limited local capacity has also contributed to developing increased inter-municipality co-operation, particularly on waste management. However, it is crucial to further strengthen the capacity of small municipalities, especially in remote areas. They often face trade-offs between economic, social and environmental objectives. Norway could benefit from stronger inter-municipal learning to share expertise and good practices.

1.4.2. Regulatory framework for environmental management

As a member of the EEA, Norway applies many environment-relevant EU directives (e.g. the WFD, EU Waste Framework, EU air quality directives, chemicals regulations). On climate action, Norway has been part of the EU ETS since 2008. In 2019, Norway, Iceland and the European Union agreed to strengthen their co-operation to fulfil the 2030 climate target. Norway committed to applying the Effort Sharing Regulation and the LULUCF Regulation in 2021-30. Substantial parts of legislative proposals related to the European Green Deal will fall within the scope of the EEA Agreement. Norway has also developed its own national regulatory frameworks in areas outside the scope of the EEA (e.g. for agriculture, fisheries, biodiversity).

Environmental assessment

Norway has more than 30 years of experience with environmental assessments. EIAs – a vital tool for integrating environmental concerns into project approval – have contributed to an orderly planning process and strengthened public engagement in Norway. Planning is further supported by strategic environmental assessment (SEA), which focuses on potentially significant environmental impact of proposed plans, programmes or policies.

Norway incorporated EU directives of 2014 on EIA and SEA into its legal system in 2017. The country’s environmental assessment system has three separate processes: one for land-based projects, one for maritime projects and a dedicated process for projects on Svalbard.5 An EIA decision is mandatory for all category 1 operations (major industrial and infrastructure projects); without a validated EIA, no permit can be issued. For facilities with lower environmental impacts, permits are sometimes granted without an EIA. The Norwegian Environment Agency maintains a dedicated web portal that offers guidance and examples of good practices on EIA and SEA.

Since 2013, the Ministry of Climate and Environment and the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation have shared responsibility for environmental assessments. These processes are primarily integrated into the ordinary procedure for land-use planning and applications for licences and permits. The Norwegian system applies an integrated approach involving “competent authorities” – either the relevant municipality or a sectoral authority. For example, road authorities take decisions on major road transport infrastructure; energy authorities examine energy-related projects. The competent local, regional or sectoral authority makes the final decision, which interested parties can challenge in court.

While environmental assessments are conducted at national level for major projects (e.g. national infrastructure, renewable energy projects), local municipalities are responsible for EIA in most cases. The local authority may be both the applicant and the competent authority. This double role creates a potential conflict of interest, particularly in smaller municipalities, as there is no independent authority in the approval process. The local authority is required to act objectively and the “two roles shall as far as possible be kept administratively separate” (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2017[44]). In practice, however, local interests may sometimes lead to sub-optimal decisions as regards environmental outcomes: EIAs may address only direct and immediate on-site effects. Limited local capacity can also undermine the quality of the EIA process. Every municipality should benefit from the expertise of a dedicated environmental officer. More room should be given to independent, critical, interdisciplinary voices in local decision-making processes.

The Arctic region is characterised by sparse population, unique biodiversity, fragile ecosystems and slow flora and fauna recovery rates from disturbance. The Norwegian Arctic is home to close to half a million people. On average, about 10% of the population is indigenous. The Arctic EIA project – involving members of the Arctic Council* – gathered examples of good practices from across the Arctic. Findings are presented in a report that identified three broad areas for improvement: i) meaningful engagement; ii) use of different types of knowledge – indigenous, local and scientific; and iii) transboundary environmental impacts. Public participation in the early planning phase is a key feature of the EIA process. It is especially relevant for the fragile Arctic areas where impact assessments must be better informed by people with knowledge and expertise of local livelihoods. This can be a lengthy process and requires a lot of flexibility. The report recommends building a relationship and trust among the affected communities at the earliest possible stage. Competent authorities “need to talk to scientists and locals at the same time – not scientists first and locals after” (SDWG, 2019[45]). Some members of the Sami Reindeer Herders’ Association of Norway suspect consultation processes are undermined by asymmetric information, unequal negotiation power and lack of transparency. Investors might be tempted to strike a deal with locals that may neither benefit all members of affected communities nor allow protection of biodiversity and fragile ecosystems. Promoting effective and meaningful engagement and incorporating indigenous knowledge remains a common challenge in the Arctic region. The report stresses that dialogue has to be seen to help find better solutions and more strongly influence project design at an early stage. This requires continuous dialogue, beyond one-off consultations. As in other countries, EIAs need to better inform the project design and decision-making process; the engagement needs to be pursued throughout the mitigation and monitoring phases. The follow-up component is nearly always missing.

Note: *Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, Sweden and the United States.

Source: (Arctic Council, Sustainable Development Working Group, 2019[46]).

Environmental permitting and licensing

Environmental permitting is a key instrument for reducing industry’s environmental impacts while also promoting technological innovation. Norway has integrated environmental permits. Applications for pollution control permits for businesses must be submitted to the Norwegian Environment Agency or to the environmental department of the pertinent county governor, depending on risk and the scale of projected environmental impacts. The Norwegian pollution control system has a high degree of transparency. Within the Pollution Release and Transfer Register (Norwegian Environment Agency, 2021[47]), all permits, inspection and annual compliance reports are available on line. The website provides access to permitting and inspection information accompanied with data visualisation tools on reported emission and plant-specific information such as production outputs. This helps users visualise the plant’s impact on the environment. The European Environmental Bureau commended Norway for “offering citizens industrial pollution permitting information of a high standard and in a user-friendly manner” (EEB, 2017[48]). Norway’s information sharing system on industrial pollution ranked the best in Europe (EEB, 2017[48]).

1.4.3. Compliance assurance

Norway has a solid compliance assurance system using a combination of compliance promotion, monitoring and enforcement. The Norwegian Environment Agency and the respective county governors, who conduct inspections, have a joint compliance monitoring strategy for 2016-20 and share a corporate database of inspection results across all sectors. The strategy aims to ensure quick and strict follow-up on serious breaches of regulations; uniform practices through good routines, tools and clear job descriptions; and better and faster communication on inspection results.

Compliance monitoring and promotion

In line with international trends, Norway uses risk-based targeting of compliance monitoring. This approach means that high-risk installations with major environmental impacts and installations with risk for non-compliance are inspected more often. The frequency depends on various factors (emission levels, results from previous inspections and audits, recidivism, etc.). As a consequence, non-compliance detection is higher and does not necessarily represent the general compliance behaviour in the regulated community. In addition, approximately 30% of site inspections are conducted without prior notice. The threat of unannounced site visits has a dissuasive effect and encourages businesses to take steps to ensure compliance throughout the year.

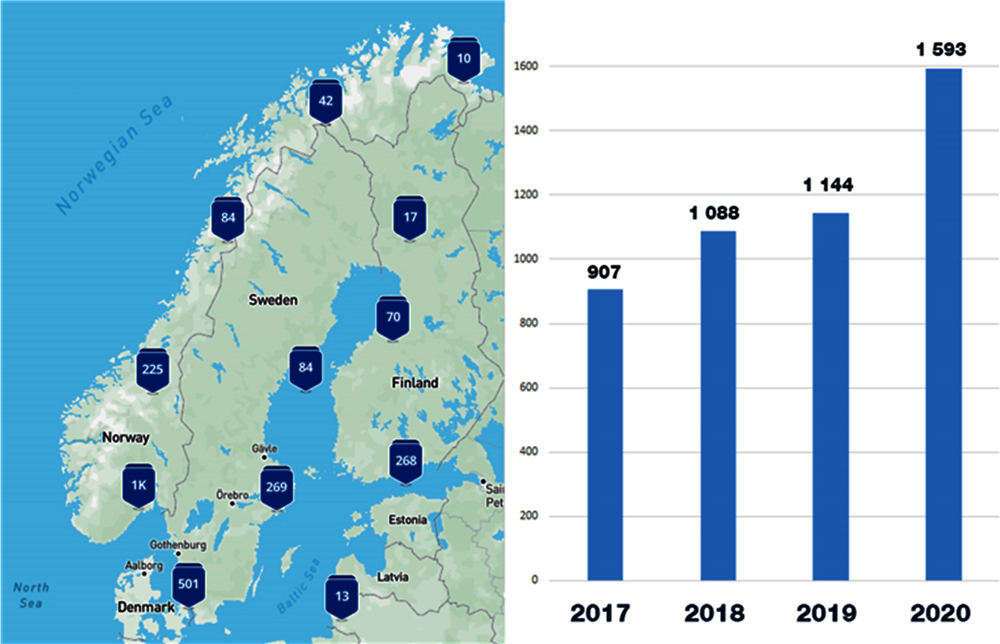

Between 2015-20, Norway conducted about 5 500 inspections of land-based industry; offshore petroleum industry; products and chemicals; regulated species; and various municipal activities. Compliance monitoring also includes desk verification of self-monitoring reports and online checks of products. E-commerce non-compliance is particularly high and requires continued attention.6 There are fewer inspections than a decade ago (about 2 000 inspections per year) but still more than in the 1990s (about 275 inspections per year) (OECD, 2011[27]). Due to mobility restrictions related to COVID-19, the number of inspections decreased in 2020 (Table 1.2). Businesses fully cover the costs related to the preparation, implementation and follow-up of inspections. Standard rates are specified in the Pollution Control Act.

Norway has a high rate of non-compliance (60-70% of the checks, including 10% of serious violations). About two-thirds of breaches are related to weaknesses of self-monitoring systems. The high non-compliance rate confirms the quality of Norway’s monitoring system and its capacity to detect violations. However, it also underlines a need for stronger compliance monitoring. Moreover, Norway’s inspection results need to be interpreted in light of more in-depth compliance monitoring. Such monitoring checks the performance of company-internal environmental management systems whose elements are mandated by law. This makes the Norwegian system unique in the OECD area. The requirements are challenging for smaller companies; many have not sufficiently invested to meet them. They still lack routine checks and knowledge about safety standards and environmental requirements, including for chemical management for imported products. This underlines the importance of inspection campaigns and compliance promotion, which need to be pursued.

Compliance promotion is critical for closing the implementation gap. While the Norwegian Environment Agency primarily monitors compliance, it also publishes various guidelines and provides advice. Inspection activities also contributed to improving the enterprises' knowledge on regulations and compliance. The impact of these activities could be more systematically monitored, beyond the annual reporting of the Norwegian Environment Agency.

Enforcement

Enforcement authorities usually give the offender time to correct the violation before considering sanctions. Administrative penalties are applied in only 2% of inspected cases. Depending on what is considered to be most effective, a combination of administrative and criminal sanctions may be applied. Norway is one of the few OECD countries using coercive fines. This means the fine is only payable if the operator fails to implement prescribed corrective action in a mandated timeframe. This has proven to be an effective enforcement instrument. Over 2016-20, on average, only about 10% of fines need to be paid (13 out of 130 fine notifications); in 90% of cases, operators complied in time.

The government intends to sharpen focus on crime prevention. New measures have been proposed to strengthen criminal prosecution through better review practices, higher penalties, increased use of confiscation and digital solutions. Severe violations are subject to criminal sanctions, including imprisonment. They are handled by the police districts and Økokrim, Norway’s specialised agency for combating economic and environmental crime. Established in 1989, Økokrim is being reformed to remove organisational silos and make it more flexible and reactive. It will also have a stronger focus on crime prevention. New measures are also put forward in a white paper (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2019[49]), which aims at strengthening criminal prosecution through better review practices, higher penalties, increased use of confiscation and digital solutions.

1.5.1. Greening the tax system

Like other Scandinavian countries, Norway is a high tax country with a broad tax base, which allows it to finance its broad social safety net with universal health care and higher education. Norway has a high tax-to-GDP ratio of 38.6% in 2020 and a high value-added tax (VAT) rate of 25% (OECD, 2021[50]).

Norway is a pioneer in using economic instruments for environmental protection to encourage innovation and internalise some of the environmental costs of harmful activities in line with the polluter-pays principle. It was among the first countries to introduce a carbon tax in 1991. Since then, the country has introduced many other environment-related taxes in response to recommendations from green tax commissions and inter-departmental working groups. All per-unit rates of excise duties are adjusted annually in line with estimated inflation, reflecting good practices to maintain their incentive function and revenue. Relevant ministries help design taxes within the annual budget proposals.

According to preliminary 2020 data, the government collected environmental tax revenue of NOK 67.5 billion (USD 7.2 billion), representing 2% of GDP and 5.1% of total government revenue from taxes and social contributions (TSC) (Figure 1.19). This is relatively low compared to the OECD Europe average because of the high weight of other sources of tax revenue, as well as to the environmental tax incentives for EV uptake. However, if environmental taxes work as intended, environmental tax revenue as a share of GDP (and total taxes) should decrease and gradually approach zero. In Norway’s case, environmental taxes contributed effectively to reducing environmentally harmful activities. This success, however, undermined the tax base, as illustrated in the example of forgone tax revenues in relation to EVs (Section 1.5.3). As in other OECD countries, energy-related taxes, including taxes on road transport energy, make up the bulk of environment-related taxes (65%), followed by transport taxes (30%); only a small portion comes from waste and other pollution and resource taxes (5%).

The share of green taxes in Norway’s TSC declined over the past decade from 6.7% in 2005 to 5.1% in 2020 (Figure 1.19). However, a closer look at the breakdown of environmental tax revenue reveals that energy and pollution-related taxes have both increased since 2005. In contrast, transport-related taxes declined slowly from about 50% in 2005 to 42% in 2016, and then recorded a sharp drop reaching about 30% in 2020. This reflects forgone tax revenues in relation to Norway’s generous tax incentives for EVs (Table 1.3). While policy measures triggered a strong increase in the purchase of EVs, the related tax revenue losses represented close to a third of environmental tax revenue (Section 1.5.3).

1.5.2. Carbon pricing and taxes on energy use

Norway applies a series of taxes on GHG emissions and energy use. The former include a CO2 tax on mineral products, a tax on CO2 emissions from petroleum activities on the continental shelf and taxes for other GHG emissions (e.g. hydrofluorocarbons and perfluorocarbons).7 Energy taxes include excise taxes on engine fuel, a base tax on mineral oil, a tax on lubricating oil and an electricity tax. In addition, Norway has fully taken part in the EU ETS since 2008 and intends to align with EU measures for the non-ETS sector, with sometimes more stringent targets.8 According to national assessments, CO2 taxes and emissions trading cover approximately 85% of national GHG emissions, including offshore production.

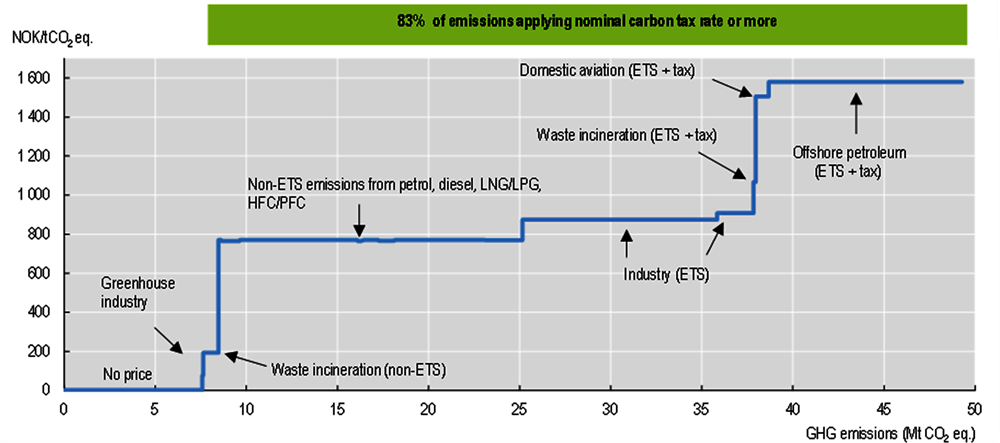

Norway’s nominal carbon tax rate is among the highest in Europe (NOK 766 [about USD 89]/tonne of CO2-eq as of 2022) covering 83% of national emissions. Figure 1.20 provides an overview of how energy and carbon taxes apply across the economy. Effective tax rates are high compared to other European OECD countries, especially outside the road transport sector.

Norway ranks among the top OECD countries in carbon pricing. In 2018, it was ranked third on the OECD Carbon Pricing Score based largely on three factors. It has a highly decarbonised electricity supply. It also charges significant taxes on fossil fuels in the residential and commercial sector. Finally, it double taxes emissions from petroleum extraction and aviation via a national carbon tax and the EU ETS (OECD, 2021[51]).

Nevertheless, it should pursue efforts to ensure uniform application of the carbon tax across all sectors. The recent abolishment of several exemptions in the maritime sector, notably the introduction of a CO2 tax on diesel used in coastal fisheries and antique vessels and machinery, heads in the right direction. Norway has also introduced a carbon tax on waste incineration and abolished the exemption for the use of natural gas and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) in the greenhouse industry in 2022. Norway needs to pursue efforts to remove inappropriate exemptions in environmentally related taxes and harmful subsidies.

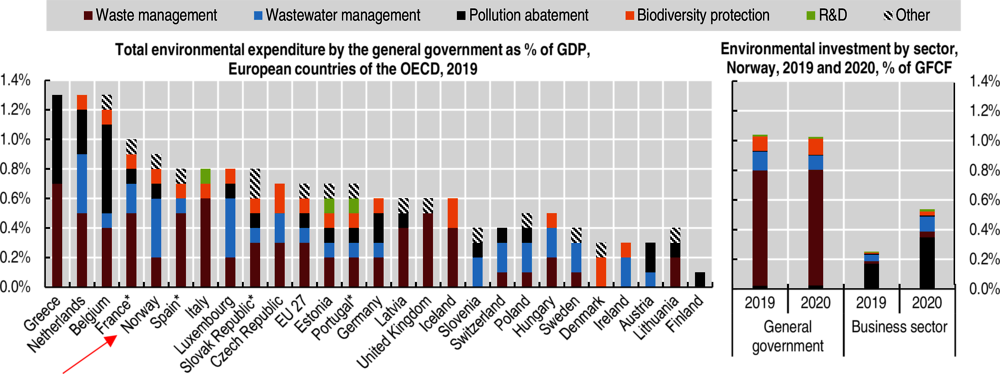

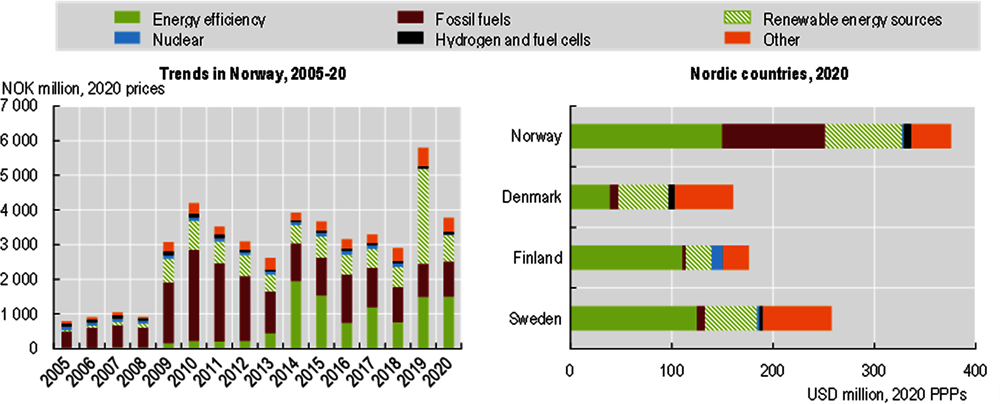

Norway’s Climate Action Plan 2021-30 proposes to gradually raise the carbon tax on non-ETS emissions from NOK 590 per tonne of CO2-eq in 2021 to NOK 2 000 by 2030 (from USD 69 to USD 234). The precise arrangements to operationalise the required tax shift will be part of a negotiation process and are expected to be approved by Parliament within its annual budget cycle. A first step was taken in 2022, when the general tax rate on non-ETS emissions was increased by 28% (in real value). By 2030, the scheduled increase in carbon prices is expected to reduce emissions by an estimated 8 million tonnes of CO2-eq. Norway’s gradual carbon tax increase would provide a long-term perspective on carbon pricing and a strong price signal to encourage increased investments in renewable energy and low-carbon technologies.