4. Promoting entrepreneurship and private sector engagement

This chapter discusses the role of entrepreneurship and private sector engagement in driving structural change and renewal in regions in industrial transition. A number of barriers to innovative entrepreneurship often persist in regions with a strong industrial heritage, notably low levels of start-up and scale-up activity, weak entrepreneurship cultures and a lack of innovation and effectively linked knowledge networks. The chapter sheds light on overcoming these barriers by making use of appropriate finance, skills and knowledge exchange policies. It identifies a suite of potential policy instruments and highlights the role of local and regional authorities in designing integrated and locally tailored policy packages. Finally, it summarises key considerations for policymakers in regions in industrial transition to make more strategic use of local innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystems in order to stimulate entrepreneurial activity and innovation-led growth.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Innovative entrepreneurship can help renew old industrial structures

Entrepreneurship and private sector engagement are key drivers of regional industrial diversification and future competitiveness. Entrepreneurial start-ups, scale-ups and entrepreneurial employees in large companies spur economic growth and new job generation in emerging fields of (industrial) activity. Economic development does not emerge automatically; entrepreneurs who experiment at the level of new and established firms are needed. While some of these experiments fail, others succeed as innovations and create wealth for society.

Regions in industrial transition are often characterised by capital-intensive, sometimes declining industry dominated by large (often multinational) companies, creating high barriers to entry for entrepreneurs and start-ups. Empowering and encouraging entrepreneurship is even more important in this type of region than in other regions because it helps diversify the local economy and move into new activities.

Start-ups and scale-ups can drive job creation

Compared to very dynamic regions, those in industrial transition are typically home to older firms in long-established industries with relatively low churn. These regions are also home to fewer young and high-growth firms. This can be problematic as it is young firms, especially, that contribute to job creation (Figure 4.1) (Criscuolo, Gal and Menon, 2014). The aggregate figures, however, mask the heterogeneity among these firms: only a small fraction of start-ups contribute substantially to job creation, while the majority either fail in the first year or remain small (Criscuolo, Gal and Menon, 2014). Addressing policy failures, such as burdensome bankruptcy regulations or weak contract enforcement, is important in order to strengthen local high growth potential in regions in industrial transition. New businesses and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) also contribute to productivity growth and play a key role in supporting innovation. They help commercialise new knowledge and contribute to breakthrough innovations (Andersson, Braunerhjelm and Thulin, 2012).

Stimulating entrepreneurship helps the emergence of new firms and boosts innovation in old firms

In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on the entrepreneurial and innovative attributes and activities of larger firms. Such businesses, whether multinational enterprises or domestic firms, are not only leading employers but also engines of economic development. Promoting entrepreneurial mindsets within large companies can help these companies reorient their future activities through inhouse process or product innovation triggered by employees with a desire to innovate.

Regions in industrial transition need to support start-up and scale-up development and entrepreneurship and innovation in large firms. Because these regions are often home to large and incumbent business in traditional and long-established industries, harnessing the entrepreneurial capacities and capabilities of employees in these firms can make an important contribution to industrial diversification. At the same time, these regions often face a decline in traditional activities that can be compensated by new economic activity arising from innovative start-ups and young firms. Such firms help transform traditional industrial activities and stimulate the emergence of new regional growth paths.

Regions in industrial transition need to support innovative entrepreneurship in a range of areas

Regions in industrial transition are home to a large range of local actors with a high potential to drive industrial modernisation and develop territorial strategies for innovation. Industrial modernisation and new industry emergence in a region are rarely due to the actions of a single individual or a single intervention. The emergence of new activities typically depends on their co-creation by many actors and the interplay of a set of factors, such as leadership, culture, capital markets and open-minded customers, that combine in a complex way to stimulate entrepreneurship.

Regions in industrial transition have a long legacy in manufacturing and are often home to large-scale companies in established industries. Given this, successful industrial modernisation should build on the knowledge and expertise acquired in these industries in order to move into new and emerging activities. It is, therefore, important to include these firms as key players in local entrepreneurial ecosystems and to build future-oriented management skills in important local employers.

Different regions in industrial transition display very different initial entrepreneurship ecosystems and drivers and barriers to innovative entrepreneurship often vary by region. This is also the case for regions that have undergone or are undergoing an industrial transition. Entrepreneurship policy needs to be responsive to local contexts, carefully targeting specific regional conditions. At the same time, innovative entrepreneurship requires well-sequenced action in a variety of areas, ranging from providing access to finance and supporting skills, to simplifying regulations, enhancing competencies and culture, and strengthening knowledge exchange (Figure 4.2).

What challenges and opportunities do regions in industrial transition face in promoting entrepreneurship and private sector engagement?

New technologies and ways of working are likely to have a profound impact on the nature of work in firms and industries (see Chapter 2). This comes with strong opportunities for entrepreneurs and small businesses to advance into new markets. However, seizing such opportunities is not self-evident for regions in industrial transition. Generating entrepreneurial skills and creating networks among firms, universities, civil society and public institutions are challenging for many of these regions. A lack of management experience and entrepreneurial skills, particularly among younger entrepreneurs, frequently pose a barrier to entrepreneurship. Businesses with scale-up ambitions need to attract and retain talent in order to continue growing and innovating and can face a lack of skilled workers. Researchers in universities often lack the necessary entrepreneurial skills, particularly in management and business, needed to transform research into promising commercial activities for the region. Lastly, more policy entrepreneurs and creative thinkers are needed in public institutions and civil society to actively engage in regional entrepreneurial discovery processes.

Access to appropriate finance often poses a challenge for firms in regions in industrial transition

Regions undergoing an industrial transition must seize the potential of innovative entrepreneurship to successfully modernise their industries and guide the local economy towards new and emerging activities. Yet, among regions in industrial transition, there can be start-ups and SMEs that struggle to attract adequate and sustained financing. Experience among some regions in industrial transition points to finance offerings that do not always correspond to the needs of scale-ups and start-ups that rely on intangible assets or display particularly high-risk profiles. This may pose a barrier to the development of innovative entrepreneurship in these regions, as many businesses do not invest in new business models if the funding is not secured. Furthermore, in certain regions in industrial transition (Annex A), SMEs are still largely dependent on debt-based financing instruments, making them more vulnerable to shifts in credit markets.

New and alternative sources of finance and a better understanding of emerging trends and opportunities for financing start-ups and scale-ups can help regions in industrial transition improve their entrepreneurship conditions and better support their entrepreneurs. However, alternative sources of finance such as, for example, venture capital, account only for a small percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) among OECD countries, particularly its European members (Figure 4.3). This further limits companies with high growth ambitions to embark on riskier endeavours.

Unlocking entrepreneurial potential requires more investment in entrepreneurial skills and culture

Entrepreneurship is an important driver of industrial modernisation and developing entrepreneurship potential in regions in industrial transition is one role for concerned policymakers. It enables the creation of new firms and businesses and helps avoid being locked into existing and dominant industrial structures. Regions in industrial transition with a highly specialised industrial base often face more negative social attitudes towards entrepreneurship than regions where industry size has traditionally been diverse (Huggins and Thompson, 2014).

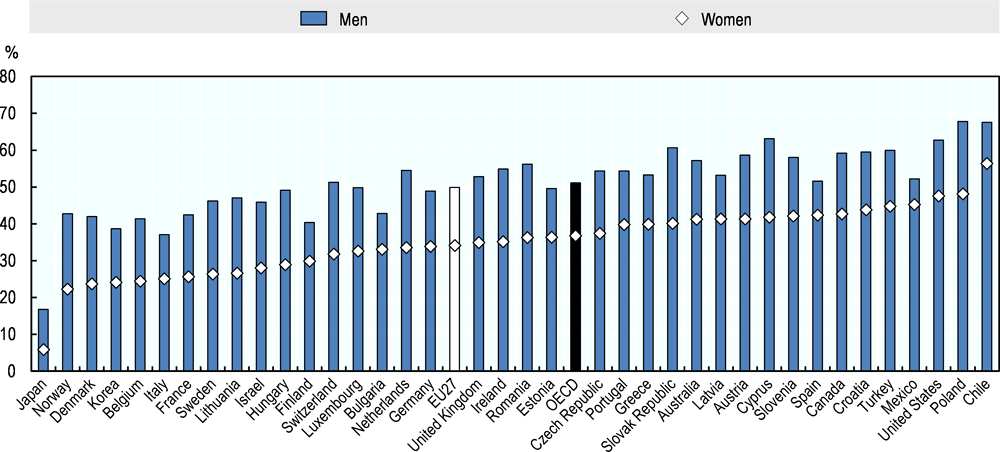

Entrepreneurial culture is also closely associated with self-perceived entrepreneurial skills. Even where people are motivated to start a business, they may be constrained by the belief that they do not have sufficient capability to do so successfully. In the European Union, about one-third of women (34.1%) reported that they had the knowledge and skills to start a business over the 2012-16 period relative to half of men (49.9%) (Figure 4.4). Given the long tradition of manufacturing and the presence of well-established companies in traditional sectors in regions in industrial transition, self-perceived entrepreneurial skills are likely to be low rather than high in many of these regions.

In addition to a lack of perceived skills, a negative attitude toward failure can affect entrepreneurial culture. Places and cultures where failure is seen as a chance to learn and improve before starting on the next venture provide better environments for entrepreneurship to flourish than those where failure is seen as a weakness or flaw. Barring the existence of an enabling culture, entrepreneurship requires clear and concise framework conditions, and empowering potential entrepreneurs by providing them with the necessary entrepreneurial skills and confidence.

How can policy (better) support entrepreneurship and private sector engagement?

Entrepreneurship policy and private sector engagement aim to address a range of concrete problems for SMEs and entrepreneurs and support creating an enabling business environment for industrial modernisation. For regions in industrial transition that face barriers to innovative entrepreneurship based on their legacy as old manufacturing regions, better access to finance for start-ups and scale-ups, higher levels of investment in entrepreneurial skills, connections and learning, as well as an improved regulatory environment helps stimulate innovative entrepreneurship.

Several policy approaches exist to support start-up and scale-up financing

Policies to support an entrepreneur’s access financing are rooted in addressing market failures such as information asymmetries and financing gaps. There are a number of policy approaches to improve access to finance for start-ups and scale-ups, including the use of traditional policy instruments, promoting alternative sources of finance and strengthening financial education (Table 4.1).

Alternative funding instruments can support entrepreneurs in regions in industrial transition

For regions in industrial transition, alternative financing instruments provide an important addition to traditional debt instruments, which entrepreneurs with innovative business models might not be able to access due to a high-risk profile. The spectrum of available alternative financing instruments is large and covers different financing needs, firm characteristics and risk profiles (Figure 4.5). In principle, asset-based finance and alternative debt mechanisms are available to a wide range of firms and are particularly suitable for firms that have a low risk of default, but also limited returns. Hybrid instruments combine debt and equity schemes and are most suitable to more mature or high-growth firms. Public and private equity instruments target high-growth, high-risk ventures.

New opportunities for SME financing are also found in a range of technology-enabled financial service innovations, such as Fintech, digital platforms and blockchain technologies. A basic example of a Fintech offering is the mobile banking services offered by most traditional banks. As they often drive transactions costs down, these technological developments will likely make it more profitable for financial institutions to serve a client base that includes (small) businesses in remote or rural areas (OECD, 2018a). Blockchain technology will further allow start-ups and scale-ups to undertake transactions at increased speed and transparency, offering a number of opportunities, including the development of smart contracts, reducing reliance on intermediaries and raising additional funding.

In regions in industrial transition, the availability and access to different sources of financing is constrained by a combination of barriers. Many entrepreneurs and business owners lack the financial knowledge, resources or sometimes the willingness to successfully access financing beyond debt-based resources. Public policy dedicated to financial literacy programmes can help increase the awareness and capacity of SMEs to access external financing. These programmes aim to improve the quality of loan applications and financial pitches, and to increase knowledge of different financing options.

Governments in regions in industrial transition can help increase knowledge and awareness of the range of instruments available

Governments in transition regions can help facilitate access to financing for start-ups and scale-ups by offering grants (e.g. vouchers), loans or loan guarantees. Care needs to be taken however, not to crowd out the private sector. To this end, regional governments can also promote alternative sources of financing. One technique is to help develop business angel networks. Another is to back private venture capital schemes through co-investment, particularly in the case of early-stage entrepreneurial ventures, as seen in Saxony, Germany (Box 4.1). Regional governments can also offer co-financing based on contractual arrangements.

Using state and private capital to invest in young firms and start-ups

TGFS is a venture capital fund that uses private and public funding in order to support innovative start-ups. The fund’s investors are the region of Saxony, regional saving banks and two regional investment companies. The programme offers an alternative to debt-based funding methods by providing fully liable equity. Innovative young firms may receive between EUR 100 000 and EUR 5 million, generally granted in stages. TGFS invests as a minority stakeholder, a silent partner or through subordinated loans. Companies are expected to exit the fund after three to six years.

Thus far, 56 investments have been made, with 459 jobs created and a financial leverage effect of EUR 53 million. Regional capital investment companies manage the fund and invest in Saxon SMEs that are active in emerging high-tech and innovative industries.

Source: Saxony (2018), “TGFS: The venture capital funds for Saxony”, PowerPoint Presentation for the Peer Learning in Regions in industrial transition Workshop: Promoting Entrepreneurship and Mobilising the Private Sector, 7-8 June 2018, Torino, Italy, Unpublished.

Supporting entrepreneurs with access to training, coaching, networks and partnerships

A successful industrial transformation also hinges on the ability of public authorities, companies and entrepreneurs to identify new markets and potential transition opportunities. A number of policy instruments exist to support start-ups, scale-ups and entrepreneurial employees with entrepreneurship training, skills development and knowledge transfer (Table 4.2).

Strengthening entrepreneurship through dedicated training

Entrepreneurship support typically aims to increase an entrepreneur’s knowledge about starting or growing a business and provide networking opportunities. For regions in industrial transition, entrepreneurship support programmes can increase levels of information and awareness about entrepreneurship as an alternative route to the labour market. Effective policy packages should include a suite of tools, certainly including essential information but also covering including more intense forms of support such as coaching and mentoring provided by incubators and accelerator programmes.

Entrepreneurship support programmes are often most effective when combining and tailoring intervention areas to a local context. The Ben Franklin Technology Partners programme in the state of Pennsylvania (United States) provides an example of how entrepreneurship is supported in a holistic manner (Box 4.2). Three important functions for regional governments in regions in industrial transition can be identified:

-

1. An intelligence function: In order for regional-level entrepreneurship policies to be successful, there needs to be a clear sense and vision of the nature of the challenges and opportunities that the region faces in stimulating entrepreneurship. Regions can play a role in defining economic vision and smart specialisation for their territories.

-

2. A support function: Regions can build and strengthen the local entrepreneurship system through supportive policy actions in a range of areas, such as entrepreneurship and SME policy, education and science policy, including as part of a broader regional development policy.

-

3. A linkage function: Regions as institutional entrepreneurs can also facilitate networks for enhancing knowledge spill-overs between firms, higher education institutions, civil society and government.

Ben Franklin Technology Partners is a technology-based economic development programme in Pennsylvania, United States. Launched in 1983, the programme was originally designed as a grant-giving institution to help commercialise research. Today, it consists of four regional bodies that link young companies with funding, expertise, universities and other resources to fill gaps in the entrepreneurial system that may otherwise discourage entrepreneurialism. Ben Franklin Technology Partners helps young firms in a variety of ways: by making them more attractive to different kinds of investors, providing incubator space, creating networks with colleges and universities, and helping to develop and commercialise products.

The programme is funded by the state of Pennsylvania and while it is accountable to the state government, it is completely independent in its funding decisions. The majority (51%) of its board members must be from the private sector in order to avoid bringing a political dimension into investment decisions.

The programme concentrates its support on young enterprises in three main areas: capital, networks and knowledge. In addition to providing entrepreneurs and young firms with capital, the programme’s experts and mentors provide specialised support in marketing and other areas. The impact of the programme has been striking. In 2017, there were 1 900 jobs created and 189 new companies formed thanks to Ben Franklin Technology Partners. Furthermore, third-party evaluation has shown that for every USD 1 invested in the programme, there is a return of an additional USD 3.60 in state tax revenues.

Source: Glenn, R. (2018), “Entrepreneurship: An economic development strategy”, PowerPoint Presentation for the Peer Learning in Regions in industrial transition Workshop: Promoting Entrepreneurship and Mobilising the Private Sector, 7-8 June 2018, Turin, Italy, Unpublished.

Coaching and mentoring can boost entrepreneurship if the match “works”

Coaching and mentoring relationships between experienced and new entrepreneurs can offer many benefits. They help increase awareness of entrepreneurship, develop entrepreneurial attitudes and provide helpful advice during business creation and development. An important consideration in successful mentoring is the quality of the match between the experienced entrepreneur (i.e. “mentor”) and the new entrepreneur (i.e. “mentee”). Mentoring programmes can use a number of techniques to improve the quality of the match, including mentor matching software tools and personal interviews. The Start:up Slovenia initiative has successfully mobilised mentors from diverse backgrounds to support new businesses with advice (Box 4.3).

Established in 2014, Start:up Slovenia aims to raise the level of entrepreneurial talent by developing networks that encourage company growth on international markets, contribute to higher capital accessibility and activate various ecosystem stakeholders. The initiative mobilises a network of mentors from various backgrounds to provide entrepreneurs and young firms with tailored advice. Through this personal mentorship, young firms can access new networks that can help them grow and fulfil their potential. The expected outcomes on a yearly basis are to create 1 000 new jobs in start-ups, to connect at least 50 start-up companies with the most important ecosystem and to create or attract at least 150 start-up companies with global potential.

Source: Slovenia (2018), “Peer learning in regions in industrial transition: Workshops good practice template”, Start:up Slovenia, Prepared for the Peer Learning in Regions in Industrial Transition Workshop “Promoting entrepreneurship and mobilising the private sector”, 7-8 June 2018, Torino, Italy, Unpublished.

Business incubators and business accelerators provide strong support to start-ups and scale-ups

Business incubators and business accelerators provide a package of services to entrepreneurs prior to business creation and at early stages of the business life cycle. Services offered include business coaching and advice, workshops, seminars and networking opportunities. In addition, business incubators often provide facilitates for participating (potential) start-ups to operate.

For regions in industrial transition, incubators and accelerators are important policy instruments that can potentially generate substantial benefits for emerging firms and the wider economy by speeding up entrepreneurship and innovation processes. The shift in the nature of production away from manufacturing towards services may also increase the proportion of employment in activities for which co-working models such as incubators and accelerators are relevant. Shifts in employment patterns from the traditional worker’s contract to rising self-employment and sole traders may also lead to greater demand for entrepreneurship advice and training.

Evidence suggests that business incubators and business accelerators provide effective support for new and growing businesses. Businesses associated with incubators tend to have higher survival rates, create more jobs and generate more revenue (Mubaraki and Busler, 2011).

Business support can have positive impacts on productivity and output

Evaluations of whether public support to entrepreneurship, in general, has a positive impact on business activity is mixed, though tends to lean toward the positive. Often, outcomes are positive for some measurements of business outcome, but not for all. In the United Kingdom, the What Works Centre has reviewed 23 evaluation studies on the impact of support measures on business outcomes, such as productivity, employment, sales or exports. Out of the 23 evaluation studies reviewed, 14 found that business advice has a positive impact on at least 1 out of in total 12 business outcomes. However, several evaluations found that business advice has no or negative impact on the chosen 12 business measures (What Works Centre, 2016). A key theme in evaluations seems not whether to provide support but how best to provide it. The OECD has come up with several guiding principles on policy design for business support (Box 4.4).

Based on an international policy workshop conducted together with the UK Department for Business and Energy, the OECD developed several guiding design principles on the provision of business development services (OECD, 2018b). These principles serve to improve the design and delivery of business development support, including entrepreneurship training, advice, mentoring and coaching.

-

Policymakers should understand demand-side constraints in the provision of entrepreneurship support. Low uptake of support services can also indicate demand-side gaps, such as limited SME growth ambitions, lack of awareness on the services offered, doubts about the usefulness of the services, or legitimacy issues around public operators.

-

It is important to build rather than crowd out markets. While the public sector has a responsibility to diagnose a gap to be filled by public policy, policy delivery can be more effective through external experts. This helps build a private market rather than crowd it out.

-

Tapping into firm networks and trigger points helps to target firms. Existing enterprise-led networks, such as regional clusters or chambers of commerce, are effective for outreach and to help build trust.

-

Be careful in stimulating demand where the cost is high. The cost-effectiveness of programmes is likely to be greatest where businesses have ambition and potential to grow. Resistance to growth and limited demand for business support entail a risk of over-investment in public entrepreneurship support programmes.

Source: OECD (2018b), Leveraging Business Development Services for SME Productivity Growth: International Experience and Implications for UK Policy, http://www.oecd.org/industry/smes/Final%20Draft%20Report_V11.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2019).

Entrepreneurial networks are key sources of expertise and knowledge

Governments in regions in industrial transition can help connect innovative and new entrepreneurs to existing local and global networks and value chains and support cross-fertilisation between existing networks. Innovative entrepreneurship is largely influenced by knowledge spill-overs and networks accessible to start-ups and small firms, as well as by the broad innovation system in which they are embedded. As innovation increasingly involves collaboration among a variety of players such as suppliers, customers, competitors and universities – as well as government and entrepreneurs – a key challenge for start-ups and small businesses is to connect to appropriate knowledge networks at the local, national and global levels.

Engagement in entrepreneurial networks provides start-ups and scale-ups with access to business partners, ideas, clients, financing, and help to share knowledge and expertise (OECD, 2017a). Start-ups, in particular, might have smaller and less well-developed networks and thus less access to important business resources and clients. It is, therefore, important for policymakers to increase the scale of resources available to new and potential entrepreneurs by helping them expand their networks, for example by creating networking events and developing online platforms to connect entrepreneurs with the wider business community. Entrepreneurship centres, such as that established in Cantabria, run a range of entrepreneurship training programmes to diffuse an entrepreneurship culture and provide an important platform for networks amongst future and established entrepreneurs (Box 4.5).

The Cantabria Entrepreneurship Centre (CISE) was started in 2012 as part of the Cantabria International Campus of the University of Cantabria. Its mission is to encourage creative, entrepreneurial and innovative skills among students interested in entrepreneurship and to promote a comprehensive entrepreneurship culture through the creation of networks among entrepreneurs. For this purpose, the centre operates in co-operation with programmes sponsored by public and private organisations to stimulate entrepreneurship. The programmes cover entrepreneurship training classes, individual mentoring support and networking events to facilitate connections between future and current entrepreneurs. The Government of Cantabria supports the different programmes carried out by the entrepreneurship centre as part of their strategy to promote entrepreneurship in the region.

Sources: Presentation for the Peer Learning in Regions in industrial transition Workshop: Promoting Entrepreneurship and Mobilising the Private Sector, 13-14 September, Orleans, France, Unpublished; OECD (2018c), OECD Science, Technology and Innovation Outlook 2018: Adapting to Technological and Societal Disruption, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/sti_in_outlook-2018-en.

Universities can act as knowledge brokers for start-ups and SMEs

In addition to their teaching and research obligations, generating and maintaining ties with entrepreneurs and young companies could be considered a “third mission” for universities (OECD/EU, 2018). Experience among some regions in industrial transition shows that start-ups and SMEs in regions in industrial transition can have difficulties in participating in university research and cannot usually afford to divert human resources to organise and manage collaborations. In such cases, universities can contribute to improving the conditions for innovation diffusion in SMEs and in overcoming absorptive capacity problems. Policy instruments that can support and promote the relationship between SMEs and universities through instruments include SME innovation vouchers, and start-up and SME integration in science parks.

Higher education institutions also provide a regional economy with new knowledge that can be exploited through university spin-offs. A university spin-off is an entirely new business formed around a university innovation and can be owned by the university or created by outside partners (Shane and Stuart, 2002). A unique feature of these spin-offs is that they are often very closely aligned with public research, thus providing a mechanism to transfer tacit knowledge from the research team to those responsible for the daily operations of a firm. The creation of spin-offs, however, often requires considerable financial and human capital. Such capital can be built through such targeted policy interventions as supporting the entrepreneurial competencies of researchers and providing business advice. For regions in industrial transition, this can be of particular interest in future-oriented sectors such as information and communication technology (ICT) or smart manufacturing, as also illustrated by the support scheme for innovative start-ups and spin-offs in Piemonte, Italy (Box 4.6).

Piemonte is supporting innovative start-ups and spin-offs with origins in public research. The initiative is managed by Finpiemonte, a regional development agency and investment firm, and is implemented by university incubators. The aim is to support the creation of new enterprises in three sectors: i) knowledge and technology-intensive manufacturing; ii) ICT; and iii) tourism and culture. The target groups, i.e. potential entrepreneurs, are academic researchers, youth and/or unemployed people with innovative ideas and a secondary-school diploma.

The programme revolves around four specific services or sub-schemes. First, there are preliminary advisory services to stimulate entrepreneurial attitude and identify promising entrepreneurial ideas. Second, training and tutoring services are available to candidate entrepreneurs to verify the validity of the entrepreneurial idea and to prepare the business plan. Third, ex post consultancy and tutoring services are also available in order to move from business plan to enterprise creation. Lastly, the scheme provides financial support in the first stages of business creation.

Source: Piemonte (2018), “Peer learning in regions in industrial transition: Workshops good practice template”, Prepared for the Peer Learning in Regions in industrial transition Workshop “Promoting entrepreneurship and mobilising the private sector”, 7-8 June 2018, Torino, Italy, Unpublished.

Ensuring a friendlier regulatory environment encourages entrepreneurial activity

Stimulating a generally positive entrepreneurial environment has a determinative influence on future entrepreneurs. Healthy entrepreneurial activity requires an enabling regional environment – one that is business-friendly and supportive of the unique challenges entrepreneurs and their young companies face (Table 4.3).

Creating a level playing field

Lengthy and costly company registration procedures are a major business constraint. Their impact is most heavily felt by micro- and small-sized enterprises, and they can discourage entrepreneurial activity by acting as a significant barrier for new start-ups (van Stel and Stunnenberg, 2006). Although most regulatory policy for business is designed and enacted at the national level, there is room for regional actors to play a role in managing the administrative and regulatory burden that entrepreneurs in their areas might face. Regional governments can help entrepreneurs navigate the regulatory system and often ensure that regional-level regulations are sufficiently simple but still in line with national regulatory requirements. Among the policy approaches that can be adopted at the regional level are:

-

Consultation with the business sector: Consultations support regional policymakers in identifying what regulatory requirements firms perceive as burdensome.

-

Applying regional Regulatory Impact Assessment: Regulatory Impact Assessments (RIA) at the regional level can contribute to reducing the regulatory burden on local SMEs.

-

Creating one-stop-shops: One-stop-shops offer entrepreneurs information about national and regional regulations as well as public support programmes. They can be accessed via the Internet (i.e. as a web portal) and potentially backed up by a call centre.

-

Introducing e-government services: National- and regional-level ICT solutions can cut transaction costs for entrepreneurs, improving the efficiency of public administration, generating savings on data collection and transmission, providing of information to and communicating with businesses, and enhancing government information and its accessibility (thereby increasing transparency).

Entrepreneurship is hard and failure should be encouraged

Many businesses fail and there is often a stigma attached to this. The importance of giving entrepreneurs a second chance stems from the notion that failure should be considered a learning experience rather than a disgrace. Business failure can be an opportunity for an invigorated restart. Existing evidence suggests that countries and regions favouring second chances for failed entrepreneurs and encouraging the risk-taking needed for a successful second start of business activities also have higher levels of entrepreneurship (Burchell and Hughes, 2006). Businesses set up by restarters also grow faster and create more turnover and jobs than first-time starters (Audretsch, 2007). For regions in industrial transition, particularly those with a strong culture of risk-aversion, policies that support or are tolerant of failure are important to help create an enabling environment for entrepreneurs. Several public policy mechanisms can promote a second chance; notable among them are:

-

Discharge from bankruptcy. Discharge procedures in bankruptcy laws are important mechanisms to release an entrepreneur from bankruptcy debt following a final court decision.

-

Promoting a positive attitude towards giving entrepreneurs a fresh start. Regional governments encourage potential restarters through information campaigns and training on second chances.

Supporting entrepreneurial mindsets through entrepreneurship education

Young people with entrepreneurship education are more likely to set up their own companies and businesses started by individuals with entrepreneurship training are more ambitious (Galloway and Brown, 2002). However, entrepreneurial competencies are not only vital for business innovation and business growth. Entrepreneurship education can also be understood as a journey providing individuals at every age with skills and attitudes to develop a “can do” confidence, proactivity and flexibility. For regions in industrial transition, entrepreneurship education can contribute to successful industrial modernisation. These regions tend to be home to firms with traditional business and operational models and a risk-averse attitude to innovation. Supporting entrepreneurship education in regions in industrial transition can help trigger new business models and allow entrepreneurs and established companies to move into new markets.

Entrepreneurship competencies can be acquired either through entrepreneurship education in the formal education system, starting from a young age, or through entrepreneurship training programmes at the workplace or at the university. In the workplace, entrepreneurship education enables potential entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial employees in established companies to provoke and adapt to change. Building local entrepreneurship education systems includes engaging teachers and school administrations in teaching entrepreneurship skills. Experimental and hands-on-learning can also be provided by locally organised extracurricular activities, such as business plan competitions. There is also a role for local universities to help take the entrepreneurial skills and spirit learned to a higher level. Higher education institutions (HEIs), such as research universities and universities of applied science, have become important contributors to the development of entrepreneurial mindsets (Box 4.7).

Higher education institutions (HEIs) play an important role in promoting entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial mindsets. Engaged, entrepreneurial HEIs represent important partners for innovative firms, including SMEs and start-ups. They help individuals develop and update their skills in order to match the evolving requirements of employers and be more resilient on the labour market – by providing students with an entrepreneurial mindset, and helping universities to promote creativity, problem-solving capacities, teamwork attitude and other important soft skills. HEIs can also help their regional ecosystems take advantage of cultural and natural amenities to create job opportunities and development.

In order to support entrepreneurship and innovation in HEIs, the OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Cities and Regions (CFE) and the European Commission have launched a joint action, HEInnovate, to help HEIs be innovative, foster entrepreneurship and generate value for society and the economy.

Since 2013, CFE and the European Commission have been developing an HEInnovate Guiding Framework that encompasses three components:

-

1. An online self-assessment tool, which has been used by approximately 1 000 HEIs aiming to measure their own performance in terms of “engagement”.

-

2. HEInnovate country reviews, which focus on a national case study to support governments and HEIs adopting the entrepreneurial and innovation agenda – the country reports produced in 2015-18 represent an important source of information about successful practices and stakeholder networks.

-

3. A Policy Learning Network (PLN) that gathers governments and HEI representatives from countries that have hosted a country review process. PLN meetings are organised to discuss successful practices and help their dissemination at the international level. The first PLN meeting was held in Vienna in November 2018.

Source: OECD/EU (n.d.), HEInnovate Hompage, www.heinnovate.eu.

Promoting a positive attitude to entrepreneurship through role models and ambassadors

The importance of role models for entrepreneurial motivation is well supported by research. Role models can help develop positive collective mindsets with respect to entrepreneurship and signal that entrepreneurship is a favourable career option. Several studies have shown that children of self-employed (entrepreneurial) parents are more likely to become self-employed themselves (Dunn and Holtz-Eakin, 2000; Laspita et al., 2012). For regions in industrial transition, role models can contribute to industrial modernisation by helping improve entrepreneurship cultures and stimulating innovative entrepreneurship activity. Channels to promote entrepreneurship are numerous and can include positive representations and stories in newspapers and online media, exposure to direct interaction with successful entrepreneurs, award programmes and entrepreneurship campaigns.

More needs to be done to develop monitoring and evaluation capacity

Monitoring and evaluation are needed to assess the economic efficiency of SME and entrepreneurship policies and to inform the design and mix of SME and entrepreneurship programming. Creating effective monitoring and evaluation frameworks can be challenging for all regions, but especially those with limited experience or capacity in the design and implementation of performance measurement systems, as is the case for some regions in industrial transition. Common challenges include clearly identifying policy objectives, establishing targets and indicators, making better use of existing data and collecting new data, and capitalising on the possibilities offered by Big Data. A further challenge is evaluating the impact of policy interactions and their outcomes.

Across the OECD, data and methodologies available to monitor and evaluate SME and entrepreneurship policy has improved dramatically over the last decade. However, high-quality evaluations remain rare and there is little evidence that a comprehensive approach to evaluating entrepreneurship and innovation policies is evolving (OECD, 2018b). The OECD Framework for the Evaluation of SME and Entrepreneurship Policies and Programmes established a “six steps to heaven” approach to monitor and evaluate SME policy. This approach suggests different methods of monitoring and evaluation. It starts with the monitoring of the take-up of schemes, through surveys for example, and ends with sophisticated quantitative evaluation methods (Table 4.4).

The framework can guide policymakers and programme implementers in charge of monitoring and evaluating SME and entrepreneurship policies and programmes. For the exercise to be effective, however, some critical elements need to be in place, including:

-

Clear policy objectives: many policies do not have a clear objective and they often have more than one objective, which makes evaluation difficult.

-

A good understanding of the full policy mix: a clear overview of all policies implemented and their potential interactions; and how some instruments may potentially complement or offset each other.

-

Good data: studies often fail to find a statistically significant effect when evaluating policies because of poor quality data. More and better data helps widen the scope of evaluations and improve their precision.

-

Going beyond outcomes: Policymakers should consider different variables that could affect evaluation effectiveness. These include the selected eligibility criteria, the targeted sample, the spatial unit of reference (e.g. regions or municipalities), how policy is communicated to stakeholders, etc.

-

A commitment to evaluation: A monitoring and evaluation culture should permeate all stages of the policy cycle, from defining the problem and setting the vision to evaluating results and adjusting if necessary.

Key considerations and conclusions

Support to entrepreneurship in regions in industrial transition needs to build on the region’s existing strengths and capacities. Regional policymakers have an important role in connecting, developing and supporting the regional innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystem, organising the mapping of available capacities and involving different stakeholder groups in a collaborative approach to setting future industrial goals.

Local decision-making is crucial

The local environment plays a large role in encouraging entrepreneurship. Regional governments and development agencies in regions in industrial transition need to contribute to a healthy environment for entrepreneurship by promoting an entrepreneurial culture and creating a level playing field for new start-ups vis-a-vis incumbents. In addition, the availability and quality of resources that entrepreneurs need, such as financing, premises, human resources, networks and communication infrastructure, are often locally determined. Policy should, therefore, be tailored closely to the specific needs, capabilities and institutional structures of each region and innovation system.

A holistic approach to entrepreneurship is essential

Businesses do not evolve in a vacuum and specific interventions targeted at companies need to be complemented with holistic policy action. Such action usually focuses on developing networks, building new institutional capacities, aligning priorities and fostering synergies between different stakeholders. Boosting entrepreneurship also requires a combination of policies targeting entrepreneurship, SMEs, innovation, education and science, and regional development. Often, these policy areas are not yet sufficiently integrated in regions in industrial transition and greater effort is necessary to break policy silos and support entrepreneurship and innovation in an integrated manner.

Industries, technologies and generations change

Technology is developing at an exponential rate and will continue to change business operations. At the same time, lifestyles and preferences change with every generation, and so do the products and processes developed and introduced to meet them. Businesses need to adapt to ongoing trends such as the rise of customer-centric business models, mobile solutions and digital footprints. Policy initiatives promoting entrepreneurship in regions in industrial transition – which often are home to traditional businesses with limited implementation capacity for new technologies and market demands – must take account of ongoing changes in industries and technologies and continuously review their financial and advice package in line with technological and societal developments.

Substitute density with networks in rural and remote areas

Diversification of rural or remote economies and the creation of job opportunities is a key challenge for regional regions in industrial transition, particularly those with low population density. It might not always be possible in these areas to build all elements of a functioning entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem. Against this backdrop, local SME and entrepreneurship policy in small and remote local areas may benefit from a combination of inward- and outward-looking policy strategies. One strategy is to compensate remoteness and a possible lack of resources by connecting local entrepreneurs to resources and strategic actors in larger cities or urban areas, for example through start-up boot camps, innovation hubs or similar activities.

Policy evaluation matters

Regions in industrial transition must strengthen their monitoring and evaluation systems for entrepreneurship and SME policy to better capture the impact of policies on businesses and provide justification for policy calibration where needed. This requires comprehensive monitoring and evaluation tools to evaluate the effectiveness of support schemes. Efforts need to be stepped up to look at the whole policy mix.

References

Andersson, M., P. Braunerhjelm and P. Thulin (2012), “Creative destruction and productivity: Entrepreneurship by type, sector and sequence”, Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, Vol. 1/2, pp. 125-146, https://doi.org/10.1108/20452101211261417.

Audretsch, D. (2007), “Entrepreneurship capital and economic growth”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 23/1, pp. 63-78, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grm001.

Burchell, B. and A. Hughes (2006), “The stigma of failure: An international comparison of failure tolerance and second chancing”, No. 334, Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge, http://www.cbr.cam.ac.uk (accessed on 03 February 2019).

Criscuolo, C., P. Gal and C. Menon (2014), “The Dynamics of Employment Growth: New Evidence from 18 Countries”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 14, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jz417hj6hg6-en.

Dunn, T. and D. Holtz-Eakin (2000), “Financial capital, human capital, and the transition to self‐employment: Evidence from intergenerational links”, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 18/2, pp. 282-305, https://doi.org/10.1086/209959.

Galloway, L. and W. Brown (2002), “Entrepreneurship education at university: A driver in the creation of high growth firms?”, Education+ Training, Vol. 44/8-9, pp. 398-405.

GEM (2017), Special Tabulations of the 2012-16 Adult Population Surveys, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor.

Glenn, R. (2018), “Entrepreneurship: An economic development strategy”, PowerPoint Presentation for the Peer Learning in Regions in industrial transition Workshop: Promoting Entrepreneurship and Mobilising the Private Sector, 7-8 June 2018, Turin, Italy, Unpublished.

Huggins, R. and P. Thompson (2014), “Culture, entrepreneurship and uneven development: A spatial analysis”, Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, Vol. 26/9-10, pp. 726-752, https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2014.985740.

Laspita, S. et al. (2012), “Intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial intentions”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 27/4, pp. 414-435, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.11.006.

Mubaraki, H. and M. Busler (2011), “Critical activity of successful business incubation”, International Journal of Emerging Sciences, Vol. 1/3, pp. 455-465, http://go.galegroup.com/ps/anonymous?id=GALE%7CA273715593&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=22224254&p=AONE&sw=w (accessed on 03 February 2019).

OECD (2019), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/34907e9c-en.

OECD (2018a), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2018: An OECD Scoreboard, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/fin_sme_ent-2018-en.

OECD (2018b), Leveraging Business Development Services for SME Productivity Growth: International Experience and Implications for UK Policy, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/industry/smes/Final%20Draft%20Report_V11.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2019).

OECD (2018c), “Promoting entrepreneurship and mobilising the private sector”, PowerPoint Presentation for the Peer Learning in Regions in industrial transition Workshop: Promoting Entrepreneurship and Mobilising the Private Sector, Presented 7-8 June 2018, Turin, Italy, Unpublished.

OECD (2018d), “Enhancing SME access to diversified financing instruments”, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/ministerial/documents/2018-SME-Ministerial-Conference-Plenary-Session-2.pdf.

OECD (2017a), The Geography of Firm Dynamics: Measuring Business Demography for Regional Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264286764-en.

OECD (2017b), Small, Medium, Strong. Trends in SME Performance and Business Conditions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264275683-en.

OECD (2008), OECD Framework for the Evaluation of SME and Entrepreneurship Policies and Programmes, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264040090-en.

OECD/EU (2018), Supporting Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Higher Education in The Netherlands, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, European Union, Brussels, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264292048-en.

OECD/EU (n.d.), HEInnovate Hompage, www.heinnovate.eu.

Piemonte (2018), “Peer learning in regions in industrial transition: Workshops good practice template”, Prepared for the Peer Learning in Regions in industrial transition Workshop “Promoting entrepreneurship and mobilising the private sector”, 7-8 June 2018, Torino, Italy, Unpublished.

Saxony (2018), “TGFS: The venture capital funds for Saxony”, PowerPoint Presentation for the Peer Learning in Regions in industrial transition Workshop: Promoting Entrepreneurship and Mobilising the Private Sector, 7-8 June 2018, Torino, Italy, Unpublished.

Shane, S. and T. Stuart (2002), “Organizational endowments and the performance of university start-ups”, Management Science, Vol. 48/1, pp. 154-170, https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.48.1.154.14280.

Slovenia (2018), “Peer learning in regions in industrial transition: Workshops good practice template”, Start:up Slovenia, Prepared for the Peer Learning in Regions in Industrial Transition Workshop “Promoting entrepreneurship and mobilising the private sector”, 7-8 June 2018, Torino, Italy, Unpublished.

What Works Centre (2016), Evidence Review 2 Business Advice, https://whatworksgrowth.org/public/files/Policy_Reviews/16-06-15_Business_Advice_Updated.pdf (accessed on 03 February 2019).