4. Stakeholder engagement and public consultations

Chapter 4 sheds light on the processes in place for consultation and dialogue with affected stakeholders and the general public and to what extent the outcomes can influence policy makers. It describes and evaluates the regulatory and institutional framework for stakeholder engagement, the practices in place for e-consultations, and the role of stakeholder engagement in ex ante and ex post regulatory impact assessment. In doing so, the chapter assesses the level of transparency of the legislative process in Croatia, which is one of the central pillars for effective regulation.

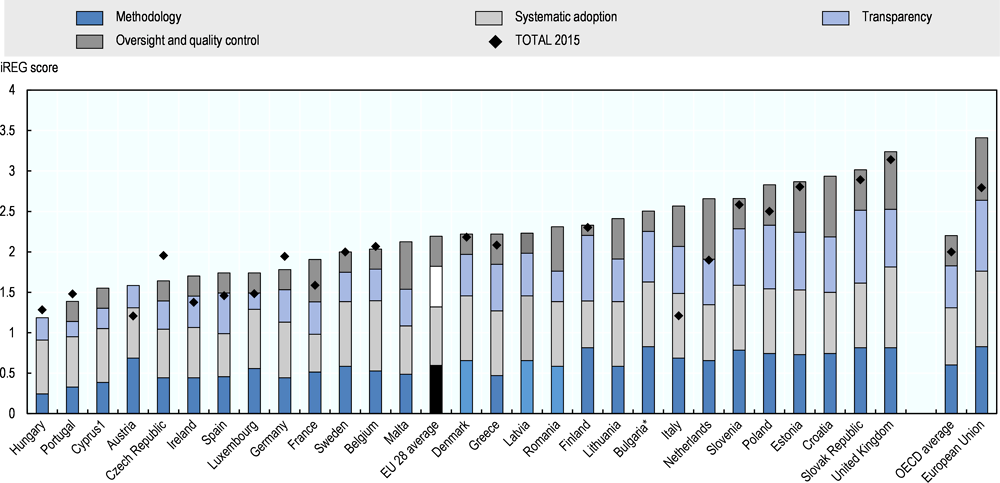

Croatia has a well-developed framework for public consultations at the central state administration level focusing mostly on web-based consultations in the later stage of the regulation-making process, with some important elements of early-based consultations, which could be developed further. As illustrated in Figure 4.1, Figure 4.2 and Figure 4.3, Croatia scores relatively high with regards to stakeholder engagement in developing both primary and secondary regulations in comparison to most of the OECD countries.

Regulatory framework for stakeholder engagement

Like many other countries, Croatia focused on transparency policies as a starting point for enhancing open government. The legislative framework for public consultations was set by the Law on the Right of Access to Information adopted in 2003, which required public bodies to disclose draft laws and to ensure that the public has an opportunity to comment.

Since the original provisions of the Law did not require that consultations actually had taken place, Croatia adopted the Code of Practice on Consultation with the interested public in the process of adopting laws, other regulations and policies in 20091 as part of reforms undertaken during the European Union accession process. The Code serves as a guidance for public consultations and sets standards, for example, for the form and duration of public consultations, ways to inform on ongoing consultations, providing feedback as well as the co-ordination of consultation procedures among the state bodies.

While the adoption of this Code was a significant step forward, it did not guarantee real change towards more inclusive and effective consultations because it is not legally binding. Achieving such change required additional implementation efforts (in terms of training, creation of institutional spaces for consultation, disclosure of information, etc.) and effective commitment from public institutions (Montero and Taxell, 2015[2]).

Detailed guidelines on how to implement the Code have been issued. These are complemented by training programmes for public servants and by creating a network of consultation co-co-ordinators (see below). Annual reports are being published on the implementation of the Code.

When the Law on the Right of Access to Information was amended in 2013,2 it finally stipulated that all public administration authorities responsible for drafting laws and subordinate regulations would be required to publish these drafts on their websites and conduct consultations with the interested public on these drafts. These drafts are published for 30 days and the dossier includes a statement on the objectives of consultations. Following the consultation process, public administration authorities are required to inform the interested public on accepting or rejecting submitted comments, remarks and suggestions. They are also required to publish reports on the conducted consultations and submit them to the Croatian Government together with the legislative draft. In exceptional cases, it is possible to shorten the period but these cases are becoming less and less frequent.

The Croatian Government’s Rules of Procedure adopted in 2011 and amended several times3 also contain important provisions with regard to public consultations. They confirm that public consultation and reporting on the results of consultations are an integral part of decision-making process on the level of the Croatian Government. Namely, a provision was added to the Rules of Procedure in 2012 obliging central government bodies to submit to the Government relevant reports on the conducted consultations together with drafts laws, other draft regulations and acts, provided that such consultations were conducted, in line with the special regulation or the Code of Practice on Consultation.

The Rules of Procedure also contain relevant provisions pertaining to the procedure of adopting general acts by the local and regional self-government units as well as legal persons vested with public authority to regulate issues in connection with the direct exercise of citizens’ rights and other issues of interest for the public good of citizens and legal persons in their area or in the area of their activity (e.g. urban design and physical planning, housing issues, public utilities and other public services, environmental protection, etc.). For those bodies, public consultations should be carried out online, through their respective websites. However, since local administration authorities are independent, it is difficult to enforce these provisions in reality.

Electronic consultations

Since 2015, public consultations are conducted through the central state consultations portal “e-Consultations” (e-Savjetovanja).4 The portal presents a unique single access point to all open public consultations of all laws, other regulations and acts carried out by public administration bodies. It was developed in co-operation with civil society organisations as well as the private sector. The system is continuously updated based on the input of all users. Civil servants are trained in using the portal and providing expert support in conducting consultations.

The portal has a simple and user-friendly interface and is searchable by the topic, institution responsible for the draft, date of issue or specific text. Anyone may submit comments after a simple registration on the portal. All submitted comments are then visible to other users and users can “like” other users’ comments. The portal also enables to group similar comments.

The responsible public administration authority is obliged to respond to all submitted comments individually. The form of response is not prescribed, so, in theory, it can only present a simple ‘duly noted’ statement. The reactions are visible to all users of the portal.

More than 2 000 legislative drafts were published for public consultations on the portal between April 2015 and September 2018 by 51 different public administration bodies. The portal had almost 20 000 registered users including more than 16 000 citizens, 1 200 companies and 790 CSOs. During this period, more than 40 000 comments were received through the portal. 5 821 legal and physical persons submitted one or more comments during 2017.

While in 2012, only 144 public consultations on draft laws, other regulations and acts were carried out, in 2017 there were already 706 public consultations taking place. This means a 490% increase in the number of consultations, also thanks to the introduction of the electronic portal.

According to the 2017 Annual report published by GOfCNGO, 22 566 comments were analysed during this year; 4 288 fully accepted, 2 382 partially accepted, 7 545 rejected, 6 430 duly noted and 1 132 unanswered.

The number of comments often varies depending on the “attractiveness” of the topic discussed but also on the level of activity of the responsible ministry in advertising consultations, for example through mass media.

Public consultations and RIA

When a regulation is foreseen to undergo the regulatory impact assessment procedure (see Chapter 5), the consultation process is also prescribed in the RIA Law. The responsible administrative bodies responsible for drafting regulations are then required to consult the public and stakeholders on the draft law and the RIA Statement.

Also in this case, consultation lasts a minimum of 30 days whereby a draft law and the RIA Statement are published on the central government consultation site. If the body responsible for drafting the regulation deems necessary, depending on the complexity of the matter, the period might be extended.

During the consultation period, the authority responsible for drafting the regulation is supposed to carry out one or more public presentations of the matter which is the subject of the consultation for the stakeholders.

Similarly to the standard consultation process, after the consultation is completed, the responsible body examines all the comments, proposals and opinions of the public and interested parties and notifies the public and the stakeholders about the accepted and rejected remarks and proposals by posting the information on the central e-government consultation site.

In the changes to the RIA Law, which entered into force in May 2017, an obligation was set regarding consulting the public in the earliest stages of the regulatory impact assessment process. Namely, the responsible body carries out the initial RIA assessment for each draft law set out in its Plan of Legislative Activities. The Plan as well as the initial RIA assessment for each of the proposed law is published for consultation on the central government consultations site in the period from 1 to 30 September, lasting at least 15 days.

Early stage consultations

Early-stage consultations (i.e. stakeholder engagement before a legislative draft is ready, usually aiming at identifying a problem and gathering initial ideas on its potential solutions) can be helpful in giving stakeholders an opportunity to provide input into the regulatory process at a stage where other options could be put forward by affected parties and assessed by policymakers. Stakeholders are likely to have far less influence once a regulatory decision has been made.

Early-stage consultation are not yet firmly embedded in the regulation-making process in Croatia. Nevertheless, examples of good practice exist across the administration. These examples could be built on to make early-stage consultations systemic.

The early-stage consultations usually take place through working groups formed by particular ministries consisting of representatives of the ministry, civil servants from other parts of the administration and other affected stakeholders. The process for the establishment and composition of these working groups is not formally prescribed by any of the guiding documents, although the Code for Consultations provide some guidance on early stage consultations. In particular, the Code says that “[d]uring the procedure for drafting laws, experts, as representatives of the interested public, may be appointed members of expert working groups … in an attempt to ensure the representation of interest groups and natural and legal persons who may be directly affected by the law or other regulation to be adopted, or who are to be included in its implementation. When members of expert working groups are appointed from the ranks of the representatives of the interested public, account should be taken of criteria such as: expertise, previous public contributions to the subject-matter in question, and other qualifications relevant to the matters regulated by the law or other regulation, or established by the act of the state administration body.”

For example, in the case of the process of preparing the draft Law on the State Inspectorate (see Chapter 7), the Ministry of Economy has established a working group with some 30 members, including representatives of businesses, trade unions, academics and citizens. Meetings of the working group were held regularly and substantively informed the new law.

There are no rules of procedure for how the discussions should be organised in the working groups. In some cases during the interviews conducted as part of the fact-finding mission, participants complained that the establishment of working groups was rather a box-ticking exercise and that their meetings were rather used to inform the external stakeholders than to have a proper discussion with them and use their input.

If a ministry or another body drafting a regulation decides to include representatives of civil society organisations in a working group, it should inform through an official letter the Council for Civil Society Development, which performs selection procedure for CSOs representatives in working groups.

In addition, some ministries use other means of stakeholder engagement at the early stage, such as roundtables, focus groups, public events, etc. but this is not regular practice. The Ministry of Economy, Crafts and Entrepreneurship has well-established relations with business representatives, such as the Chamber of Commerce, Association of Crafts, Association of Foreign Investors, etc. and tires to communicate with them on a regular basis through working lunches, hearings, workshops, etc.

In some cases, working groups are established also by the Parliament when developing new laws. For example, Parliament’s constitutional committee organised consultations on the draft regulation on electronic media. They used mixed methodologies for consulting with the public, and presented a good quality report on the outcomes of the consultation process.

On the contrary, subnational level institutions hardly implement any public consultations. The autonomy of local government units affects the limited implementation at the sub-national level. In addition to the 40 state level institutions that GOfCNGO co-ordinates and oversees, there are 575 local government units and several hundred legal persons with public authority, which should also follow the legal obligations when it comes to public consultations. Developing a central consultation portal for local levels of the administration would be useful. Discussions with the local administrations are under way on setting up a similar platform to the national one for local levels, sharing know-how and providing support.

Institutional set up for overseeing the quality of stakeholder engagement

The Information Commissioner5 and his Office (OIC) is responsible for overseeing the quality of the public consultations process. Mostly, the office checks whether consultations took place through the consultation portal and whether the 30 days consultation period was complied with. The Office also controls whether a report on the consultation process was produced and published on the portal.

The Information Commissioner also conducts regular inspections of administration authorities on the implementation of the Law on the Right of Access to Information, which focus, inter alia, on individual public consultations and consultation plans of individual ministries.

Any member of the public can complain to the Information Commissioner about public consultations not being carried out in line with the law (or at all) and the OIC has a right to issue a warrant on extending the consultation period in case of found irregularities.

The Council for Civil Society Development is an advisory body to the Government of the Republic of Croatia acting towards developing co-operation between the Government with the civil society organisations in Croatia in the implementation of the National Strategy for Creating an Enabling Environment for Civil Society Development; the development of philanthropy, social capital, partnership relations and cross sector co-operation.

The Council has 37 members out of which 17 representatives of relevant state administrative bodies and the Croatian Government offices, 14 representatives of nongovernmental, non-profit organisations, 3 representatives of civil society from foundations, trade unions and employers’ associations and 3 representatives of national associations of counties, cities and municipalities. The logistics and administrative work for the Council are carried out by the Government Office for Cooperation with NGOs of the Croatian government (GOfCNGO).

The following belong among the tasks of the Council for Civil Society Development:

-

participation in constant monitoring and analysis of public policies referring to or affecting civil society development in Croatia and cross sector co-operation and

-

participation in expressing opinions to the Government on legislation drafts affecting the development of civil society in the Republic of Croatia as well as participation in the organisation of an apt way to include and engage civil society organisations in discussions about regulations, strategies and programmes affecting the development and functioning of civil society and co-operation with the public and private sector on the national and European level.

The task of the GOfCNGO is to co-ordinate the work of ministries, central state offices, Croatian Government offices and state administrative organisations, as well as administrative bodies at local level in connection with monitoring and improving the co-operation with the non-governmental, non-profit sector in the Republic of Croatia.

A network of “consultation co-coordinators” has been established in all ministries and government offices. These contact points are providing assistance and methodological help in organising stakeholder engagement activities run by their ministries. They meet annually with the GOfCNGO to exchange experience and good practice examples and to ensure the harmonised application of the Code. The network has helped routinise public consultations by strengthening the skills of the public officials responsible for implementing consultations at national level institutions.

In 2012, the GOfCNGO trained consultation co-ordinators within state bodies and government offices. In accordance with the Code of consultation, consultation co-ordinators were appointed as permanent contact points for both public stakeholders and the body drafting the legislation. Corresponding guidelines were published in 2010. GOfCNGO continued providing trainings together with Information Commissioner to civil servants on preparing and conducting efficient consultations with the interested public in procedures of adopting laws, other regulations and acts through the State School for Public Administration. Approximately 150 officials have been trained annually on both conducting efficient consultations and the use of the e-Savjetovanja. The GOfCNGO has been also responsible for preparing annual reports on the implementation of the Code of consultation since 2010. The Information Commissioner also provides online webinars on public consultations to approximately 50 civil servants per year and education for civil servants in local administration.

The tripartite also plays an important role in public consultations. Tripartite social dialogue in Croatia is institutionalised through economic and social councils which are established primarily at the national and county level, and a few have been established at the level of a city. The Economic and Social Council of the Republic of Croatia is composed of representatives of the government, employers’ associations and five trade union associations of a higher level. The Government and the social partners have an equal number of representatives.

When the Croatian government approves its Legislative Plan, it sends the Plan to the Council for opinion. The Council can then either ask to be a member of a working group if it is going to be established, or demand that the proposal is discussed in one of its committees or directly at the tripartite meeting.

The employers’ and employees’ associations also receive legislative proposals directly, however, they often complain that the time provided for comments is insufficient. When interviewed, representatives of the trade unions expressed their discontent with their level of involvement, arguing that their comments are often disregarded. They also did not see too much use in submitting comments through the consultation portal.

The discussions in the tripartite might often come too late in the decision making process. In fact, this is also something representatives of trade union were complaining about during interviews.

Stakeholder engagement in reviewing regulations

There is no policy on how to involve stakeholders in the process of reviewing regulations. It is left to the discretion of the ministries and government agencies whether they consult the regulated subjects and discuss potential issues with the quality of the regulatory framework. Some ministries have regular contact with stakeholders, especially businesses operating in the sectors regulated by those ministries (i.e. the Ministry of Economy, Entrepreneurship and Crafts). It is not, however, a general rule.

Most of the contact with stakeholders in reviewing the existing stock of regulations is limited to measuring administrative burdens (see Chapter 6). The citizens also have a right to report excessive administrative burdens via e-mail to [email protected].

Access to regulations

According to the Constitution, all laws and regulations issued by government bodies are published in the Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia before they enter into force. This process is taken care of by the director of the Government Legislation Office who is also the editor-in-chief of the Official Gazette. The Official Gazette is available both in the printed and electronic form.6 A law shall enter into force no earlier than the eighth day after its publication in the Official Gazette, unless otherwise specifically determined by law for particularly justified reasons (e.g. on a specific day or the day after publication).

Central government bodies responsible for drafting laws and regulations are obliged to apply rules that oblige them to write laws and other regulations in a clear style, simple words and in precise and clearly expressed intentions.

Access to all official documents including international treaties, regulations issued by local self-government bodies and is also ensured electronically via the Central catalog of official documents of the Republic of Croatia.7

Assessment and recommendations

The legal and policy framework in Croatia creates conditions for efficient stakeholder engagement in regulatory policy, especially with regard to developing new regulations and their amendments. Croatia is comparing well even with many OECD countries, especially in the field of late-stage consultations, thanks to the use of the electronic consultations portal. Evidence suggests that strong political support, the process of adoption of commitments, the role of the co-ordinating unit, and an informal network of consultation co-ordinators are among the most important factors that explain the successful implementation of consultation commitments in Croatia.

While the number of public consultations carried annually is increasing and so is the number of comments received and stakeholders involved in the regulation-making process, there is still room for improvement, especially in terms of increasing awareness of the consultation process among some groups of stakeholders.

Most institutions rely exclusively on online consultations rather than combining several consultation methodologies, including early-stage consultations.8 While some ministries engage with stakeholders early in the regulation-making process, few of them are doing it systematically and this practice has not yet been fully embedded.

Local governments’ autonomy, and limited resources and capacities at the local level make consultation very rare, with only few examples of good practice.9

There is no systematic policy on engaging stakeholders in the process of reviewing existing regulations. While some ministries are in regular contact with regulated subjects, it is not a general rule. Most of the contacts with external stakeholders is limited to the process of calculating administrative burdens. This is related to the lack of experience with systemic ex post reviews of regulations.

The access to regulation is in line with the OECD best practice, all regulations in force are available both in the printed form and electronically through the Official Gazette with free access.

While there has been a significant progress in stakeholder engagement, especially regarding public consultations through the government portal, ministries and other government bodies should be more proactive in reaching out to external stakeholders to improve opportunities for all groups of stakeholders to get involved. Promoting the consultation process as well as individual consultations through the media, social networks and other channels might be useful.

More emphasis should be given to systematically conducting public consultations prior to a preferred solution being identified – the early-stage consultations. Guidance and training might be strengthened on establishing working groups, including their composition, rules of procedure and transparency of their work. Conclusions from the work of the working groups should be systematically published. Good practice examples mentioned above might serve as an example.

Stakeholders’ engagement in reviewing existing regulations should be strengthened. A permanent discussion and collaboration forum between the administration and external stakeholders (e.g. businesses) could be established to strengthen the dialogue (a good example of such body is the Danish Business Forum – see Box 4.1). This would enable that stakeholders systematically provide input on problematic and excessively burdensome areas of regulations. Potentially, the National Competitiveness Council could form a basis for creating such forum.

The Business Forum for Better Regulation was launched by the Danish Minister for Business and Growth in 2012. It aims to ensure the renewal of business regulation in close dialogue with the business community by identifying those areas that businesses perceive as the most burdensome, and propose simplification measures. These could include changing rules, introducing new processes or shortening processing times. Besides administrative burdens, the Forum’s definition of burdens also includes compliance costs in a broader sense as well as adaptation costs (“one-off” costs related to adapting to new and changed regulation).

Members of the Business Forum include industry and labour organisations, businesses, as well as experts with expertise in simplification. Members are invited by the Ministry for Business and Growth either in their personal capacity or as a representative of an organisation. The Business Forum meets three times a year to decide which proposals to send to the government. So far, the proposals covered 13 themes, ranging from “The employment of foreign workers” to “Barriers for growth”. Interested parties can furthermore submit proposals for potential simplifications through the Business Forum’s website. Information on meetings and the resulting initiatives is published online.

Proposals from the Business Forum are subject to a "comply or explain" principle. This means that the government is committed to either implement the proposed initiatives or to justify why initiatives are not implemented. As of October 2016, 603 proposals were sent to Government, of which so far 191 were fully and 189 partially implemented. The cumulated annual burden reduction of some initiatives has been estimated at DKK 790 million. Information on the progress of the implementation of all proposals is available through a dedicated website. The results are updated three times a year on www.enklereregler.dk. The Business Forum publishes annual reports on its activities. The Danish Minister for Business and Growth also sends annual reports on the activities of the Business Forum to the Danish parliament.

Source: (OECD, 2016[3]), “Pilot database on stakeholder engagement practices in regulatory policy”, http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/pilot-database-on-stakeholder-engagement-practices.htm; www.enklereregler.dk.

References

[2] Montero, A. and N. Taxell (2015), Open government reforms The challenge of making public consultations meaningful in Croatia, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/sites/default/files/U4-Report-2015-03-221215a.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2019).

[3] OECD (2016), Pilot database on stakeholder engagement practices in regulatory policy, http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/pilot-database-on-stakeholder-engagement-practices.htm.

[1] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

Notes

← 1. Official Gazette 140/2009.

← 2. Official Gazette no. 25/2013.

← 3. Official Gazette no. 54/11, 121/12, 7/13, 61/15, 99/16, 57/17.

← 4. https://esavjetovanja.gov.hr/.

← 5. The Information Commissioner protects, monitors and promotes the right of access to information and reuse of the information provided by the Constitution of the Republic of Croatia. The Commissioner is independent, reports to the Parliament and is elected by the Parliament for a term of five years with the possibility of re-election.

← 6. https://narodne-novine.nn.hr.

← 8. For example, in 2013, public agencies conducted 344 online consultations but only 84 public hearings, 97 consultation meetings and several focus groups and informal consultations; in 2014, there were 499 online consultations, 61 public hearings, and 354 advisory meetings (Croatia 2014, 2015).

← 9. For example a local e-consultation platform https://ekonzultacije.rijeka.hr/.