3. Fostering local approaches to skills in Indonesia

Indonesia has achieved substantial progress in increasing access to education and skills development. That being said, there are large disparities in terms of access and relevance across Indonesian provinces. In some rural and remote areas, literacy rates are substantially lower than the rest of the country. Disparities in education outcomes risk being exacerbated by the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, as rural and remote provinces may lack the infrastructure needed to ensure access to education. This chapter outlines trends as it relates to skills outcomes across Indonesian provinces. A special focus is given to looking at local vocational education and training opportunities that provide people with skills training that directly leads to a job.

Access to basic education and participation in secondary and tertiary education have increased in Indonesia over the last decades. However, Indonesia has room to catch up with other ASEAN countries in terms of educational attainment, which will be critical for future growth and development.

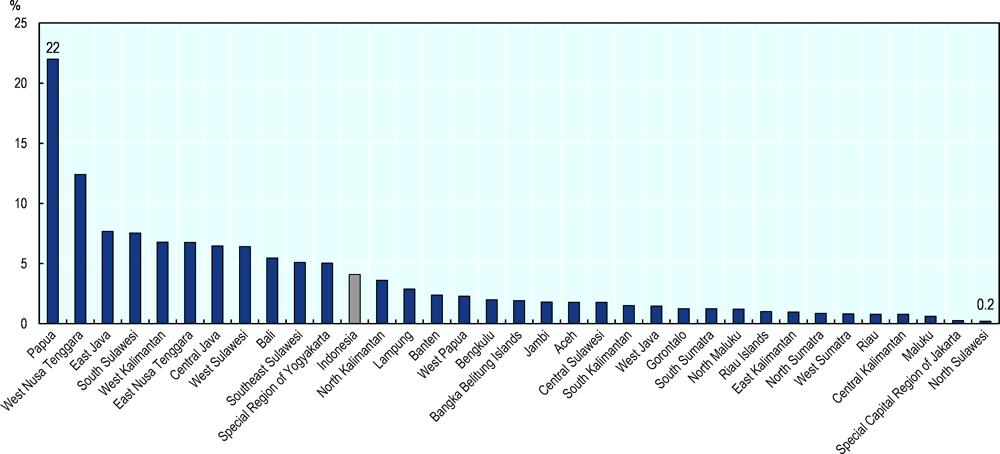

Substantial differences exist among provinces in terms of access and relevance of education and training opportunities. About one in five people in Papua are illiterate. Literacy rates are also substantially lower in West Nusa Tenggara than the rest of the country. On the contrary, in the Special Capital Region of Jakarta almost the totality of the population is literate.

The ongoing COVID-19 crisis risks negatively affecting education outcomes in Indonesia and increase disparities across provinces. The crisis is likely to lead to increased school drop-outs, hitting particularly hard disadvantaged segments of the population, who might leave education to support economically their households. In addition, provinces that are not equipped for virtual learning might face more challenges than others.

The government has invested in expanding access to vocational education and training (VET), which has resulted in higher VET student participation. VET in Indonesia is offered mainly by upper secondary education institutions (SMKs) and by work training centres (BLKs). Apprenticeships also exist in Indonesia, but they are often provided informally.

The complexity of VET governance, with many ministries and levels of government involved in the development and provision of VET, represents a challenge, often leading to fragmented local implementation. Improving teacher quality, aligning curricula with local labour market needs, and enhancing infrastructure also emerge as priorities to improve the impact of VET at the local level.

As the Indonesian economy continues its growth path, the provision of vocational education and training will be important to address potential skills mismatches, boosting job creation and supporting productivity and competitiveness. Skills are a critical driver of local economic development opportunity. Therefore, provinces in Indonesia need to look at how to develop a skilled workforce now and in the future to ensure new sources of growth and sustainable development. Indonesia has made substantial progress in expanding skills development opportunities over the last decades, and it is now close to achieving universal basic education. However, skills outcomes are uneven across provinces, with rural and remote regions in the east of the country often performing worse than their western peers. The ongoing COVID-19 crisis risks posing unexpected challenges to access to education, especially for disadvantaged groups, and increase disparities in education outcomes across provinces, as the level of readiness to the crisis of local education systems is uneven.

This chapter provides information on how Indonesia is promoting more opportunities for skills development. It provides data and analysis on the main skills development challenges facing Indonesia (sections 3.1 and 3.2), as well as recent efforts that have been introduced to promote vocational education and training (section 3.3). Finally, the chapter outlines some challenges facing the skills development system from a local development perspective and presents international good practices examples on skills development (sections 3.4 and 3.5).

Alongside poor infrastructure, skills gaps have been identified as main drivers of low labour productivity in Indonesia compared to other ASEAN countries. Recent work by the Asian Development Bank has noted that Indonesia is characterised by an oversupply of semi-skilled workers, and the education and training system is not providing students and jobseekers with the right skills needed to perform the jobs available in the country (Asian Development Bank, 2018[1]). VET can provide students and jobseekers with the skills needed in local labour markets, and it is identified as a powerful tool to address developmental challenges and inequalities in the ASEAN region (OECD, 2018[2]). Ensuring that people not only participate and achieve higher skills levels, but also access high-quality training opportunities that narrow the gap between the supply and demand of skills in the labour market, can therefore be a driver of productivity growth in Indonesia, supporting the country’s transition to higher economic performance levels.

As part of current efforts to expand access to training and skills development opportunities, the Government of Indonesia has introduced a pre-employment card, aiming to provide more than 2 million people with the skills needed in the labour market (see Box 3.1). The introduction of the card has been anticipated to early 2020, to provide support to students and jobseekers in the face of the COVID-19 outbreak. Individual learning schemes, defined as training schemes attached to individuals, have been introduced in many OECD countries to boost individual choice and responsibility concerning training and competition among providers, therefore increasing the quality and relevance of training provision. Recent OECD work shows that simplicity of use is instrumental to the success of individual learning schemes. In addition, individuals (the low-skilled in particular) also need effective face-to-face information, advice and guidance to enable them to convert their training rights into valuable training outcomes, tools that are often lacking in practice (OECD, 2019[3]).

The Government of Indonesia is placing skills development high in the political agenda, acknowledging that increasing training opportunities can promote the development of a work-ready workforce, placing people into good jobs and helping to boost productivity. To this end, the government has introduced a pre-employment card (kartu prakerja), providing access to vocational training and up-skilling opportunities for jobseekers, workers and people facing career transitions.

The programme aims to help bridge the gap between the skills that workers have and those required in the labour market. The card initially aimed to involve 2 million people in 2020 through an integrated and digital-based system, with the government allocating more than IDR 10 trillion (around USD 620 million) to the programme. Criteria for receiving the card include the possession of the Indonesian citizenship and at least 18 years of age, and not being enrolled in formal education. Benefits stemming from the card would include access to vocational training, recognised competency certificates and training incentives. Trainings accessible through the card would enable participants to obtain practical competencies, and would be aimed to address the needs of relevant industries, including food and beverages, IT, sales and marketing, banking and finance, and agriculture among others.

A well-designed pre-employment card could play an important role in providing training opportunities for those categories that already suffer from the most disadvantage, such as the unemployed and young people. The experience of OECD countries with similar financial incentives for trainings shows that such instruments should be made more generous for certain vulnerable groups as well as for training in shortage or in-demand fields.

Developments linked to the COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020 have brought the Indonesian Government to anticipate the disbursement of the card, in an effort to support workers and jobseekers. In light of COVID-19, the government has also doubled the budget allocated to the card to IDR 20 trillion and is targeting to expand its outreach and involve more than 5 million people.

Source: The Jakarta Post (2020[4]), Indonesia advances pre-employment card program to tackle pandemic impacts, https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/03/13/indonesia-advances-pre-employment-card-program-to-tackle-pandemic-impacts.html (accessed on 8 April 2020); The Jakarta Post (2019[5]), Discourse: Preemployment card all about skills, not salary for unemployed, https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2019/08/19/discourse-preemployment-card-all-about-skills-not-salary-unemployed.html (accessed on 5 February 2020); The Jakarta Post (2019[6]), Government to roll out preemployment card in early 2020, https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2019/11/13/government-to-roll-out-preemployment-card-in-early-2020.html (accessed on 5 February 2020).

3.1.1. Indonesia is working to improve access to basic foundational skills

Good skills are critical for both workers and firms. Across the OECD, adults with higher levels of skills tend to have better outcomes in the labour market and are more productive in their jobs (OECD, 2018[7]). Indonesia has achieved substantial progress in reducing adult illiteracy over the last decades. Illiteracy rates have dropped substantially across all age groups over the last decades: while 2.3% of the 15-44 aged population were illiterate in 2011, this fell to 0.8% as of 2019. Similarly, for people aged 45 and over, the rate was 18.1% in 2011 but dropped to 9.9% in 2018 (Statistics Indonesia, 2019[8]). Net enrolment in primary education has dramatically increased from around 70% in the 1970s to almost 95% today, as Indonesia is close to achieving universal basic education (OECD, 2015[9]). Compulsory education lasts nine years in Indonesia, from age 7 to age 15.

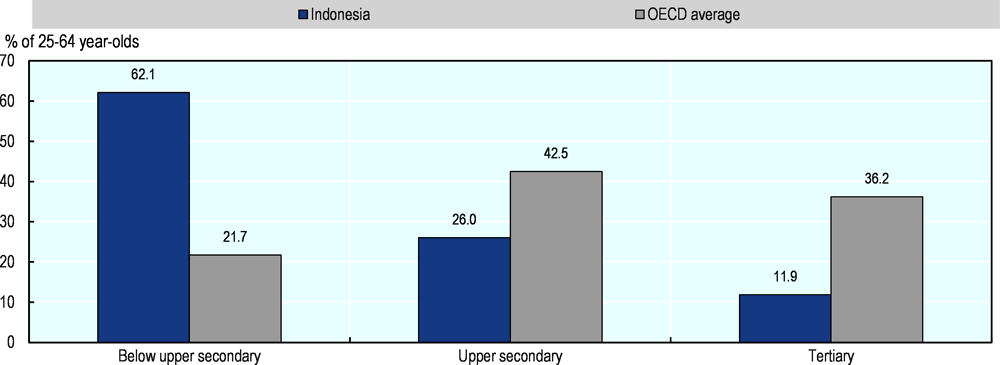

Within Indonesia, there has been a strong focus on improving secondary and tertiary educational attainment. In 2017, 26% of the Indonesian adult population had attained upper secondary education, as compared to only 14.1% in 2008. Similarly, the share of tertiary educated adults 25-64 years old has almost doubled, from 6.5% in 2008 to 11.9% in 2017. However, the majority of 25-64 year olds in Indonesia continue to possess below upper secondary education (62.1%), and there is room to catch up in educational attainment with the OECD average (see Figure 3.1). In addition, despite tertiary education enrolment almost doubled between 2000 and 2016, from 14.9% and 27.9%, Indonesia could further catch up with some ASEAN countries, such as Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines (OECD, 2019[10]).

The relevance and quality of education in Indonesia could be further improved. For example, Indonesia’s performance in the OECD Programme for International Students Assessment (PISA) 2018 shows that the competences of students in areas such as mathematics, sciences, and literacy lag behind the OECD average. There would also be room for Indonesia to catch up with other regional economies, such as Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam and Thailand. However, Indonesia performs better than the Philippines in all three areas (see Table 3.1). Since Indonesia’s first participation in PISA in 2001, performance in science has fluctuated but remained flat overall, while performance in both reading and mathematics has been hump-shaped. Reading performance in 2018 fell back to its 2001 level after a peak in 2009, while mathematics performance fluctuated more in the early years of PISA but remained relatively stable since 2009. These results need to be interpreted in the context of the vast strides that Indonesia has made in increasing enrolment in education over the past years. While in 2001, the PISA sample covered only 46% of 15- year-olds, in 2018 85% of students were covered. It is often the case that the best performing students remain in education, while new students who were not in education and were brought into the school system are weaker than those who were already included (OECD, 2019[11]).

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic poses challenges to ensure continued school participation and improvement in learning outcomes in Indonesia. While enrolment at all levels of education has been increasing over the past decades, many children and adolescents are out-of-school. The number of out-of-school children was higher in 2018 than in 2010 (1 555 014 and 763 385 children respectively), and the number of out-of-school adolescents was slightly lower in 2018 than in 2010 but remains high (2 299 116 and 2 274 037 respectively) (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2020[12]). In addition, as an answer to the virus outbreak, several regions and provinces in Indonesia restricted public events, closed schools and tourist destination as of early March. In a following public address, the government urged people nationwide to work and study from home (The Jakarta Post, 2020[13]). This risk putting further pressure on students and the school system in general, as some segments of the population and some provinces might not have the skills and infrastructure needed to undertake remote learning.

3.1.2. Differences in education attainment exist by gender and income status

Indonesian women attain slightly lower education levels than men. About 31% of the women population aged 25 and more attaining more than upper secondary education, as compared to 38.3% for men (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2020[14]). However, more young women than men are attaining a tertiary degree. Gender gaps in educational attainment in Indonesia follow the same trend as across OECD countries: 18% of 25-34 year-old women in Indonesia now have a tertiary degree compared to 14% of 25-34 year-old men (OECD, 2019[15]). Young people tend to face a challenging context in accessing skills development and labour market opportunities in Indonesia: more than one in five youth is neither in employment, nor in education or training (so-called NEETs) in Indonesia. Although this share has decreased over the last decade, it is still higher than all ASEAN countries except for Lao PDR (International Labour Organization, 2020[16]).

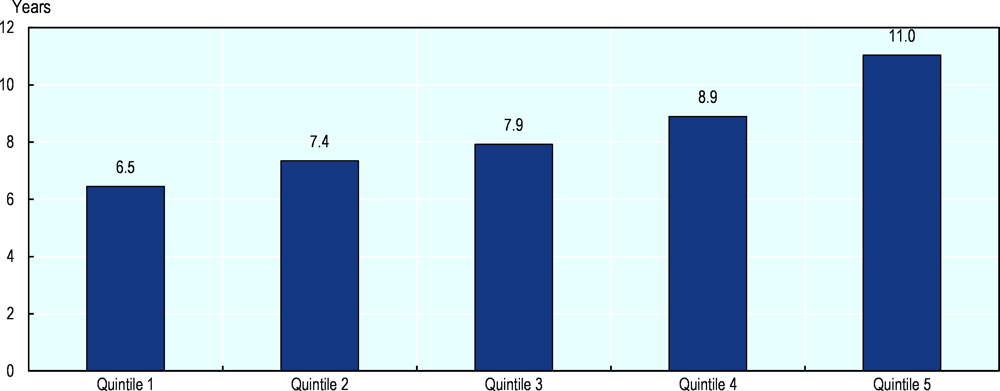

Furthermore, people with higher income levels achieve substantially higher levels of education. The average schooling years of the bottom 20% of the expenditure distribution are still almost half the schooling years of the top 20%, amounting to 6.5 and 11 years respectively (see Figure 3.2). The government has given a boost to education and skills training through the approval of a constitutional mandate in 2002, allocating at least 20% of the total government budget (APBN) and 20% of the local budget (APBD), including both provincial and district budget, to education. The large majority of the additional resources went to teacher salaries and certification, but adding teachers is not correlated with improved educational results (World Bank, 2013[17]).

Inequalities in education outcomes across segments of the population risk being further exacerbated by the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. Young and poorer people could be hit particularly hard by the economic crisis generated by the COVID-19 outbreak, as well as by related policy measures such as school closure. Disadvantaged groups might not have the means to work or study from home, and might focus on supporting their household’s income during times of crisis rather than continuing education.

3.1.3. Skills gaps and shortages represent a challenge in Indonesia

Despite substantial increases in educational attainment, the education system struggles to provide the skills needed in the labour market. From 2010 to 2015, the number of workers with senior secondary and tertiary education has risen by an annual 1 and 2 million respectively, but the quality of tertiary education is low and the learning achievement of most students is not adequate. In some sectors, the education system does not provide enough graduates, while in other sectors graduates lack the right skills needed for the job. A large share of workers with post-secondary education work in low-skill occupations, suggesting that despite holding degrees, graduates lack the right skills (Allen, 2016[18]). An ILO survey of ASEAN employers conducted in 2014 found that over 40% of respondents perceived the quality of public education as poor, higher than on average across ASEAN respondents (International Labour Organization, 2014[19]).

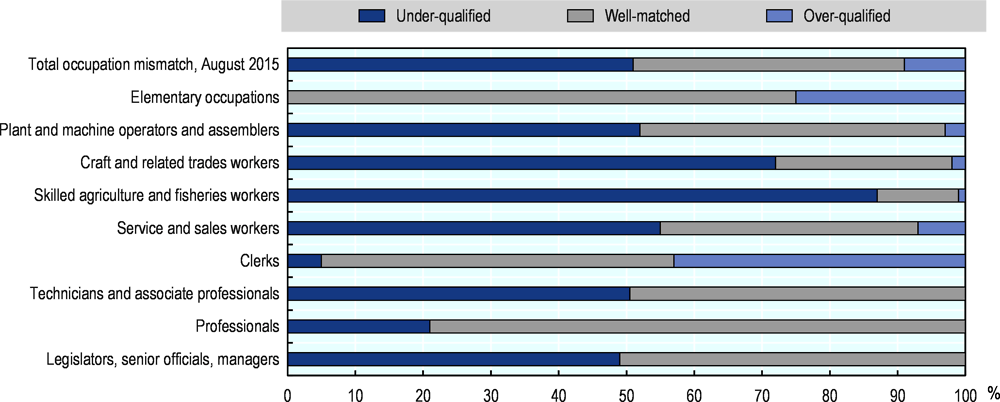

Skills shortages are also prevalent, with under-qualified workers filling many positions across sectors (see Figure 3.3). Insights from the 2015 World Bank Enterprise Survey show that the lack of required skills are the main problem when trying to fill a position for about 40% of Indonesian firms. Inadequate skills are a greater obstacle to filling managers and higher-level non-production positions, including technicians, sales associates and other professionals, than for unskilled production and non-production workers. Filling managerial position is more challenging for Indonesian firms than for firms in Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines (Calì, Hidayat and Hollweg, 2019[20]). It is estimated that, while 40% of workers are well-matched to their occupation, 51.5 % of them are under-qualified and 8.5% over-qualified (Allen, 2016[18]). Occupation mismatch in Indonesia is linked to the low education levels of production workers and agriculture labourers, as well as a large share of clerks being over-qualified for their jobs, but under-qualification is also a challenge in higher-level occupations. High levels of under-qualification and lower levels of over-qualification suggests that skills mismatches represent an issue in Indonesia. This can be an important challenge, as high levels of mismatch are typically associated with lower levels of labour productivity (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2017[21]).

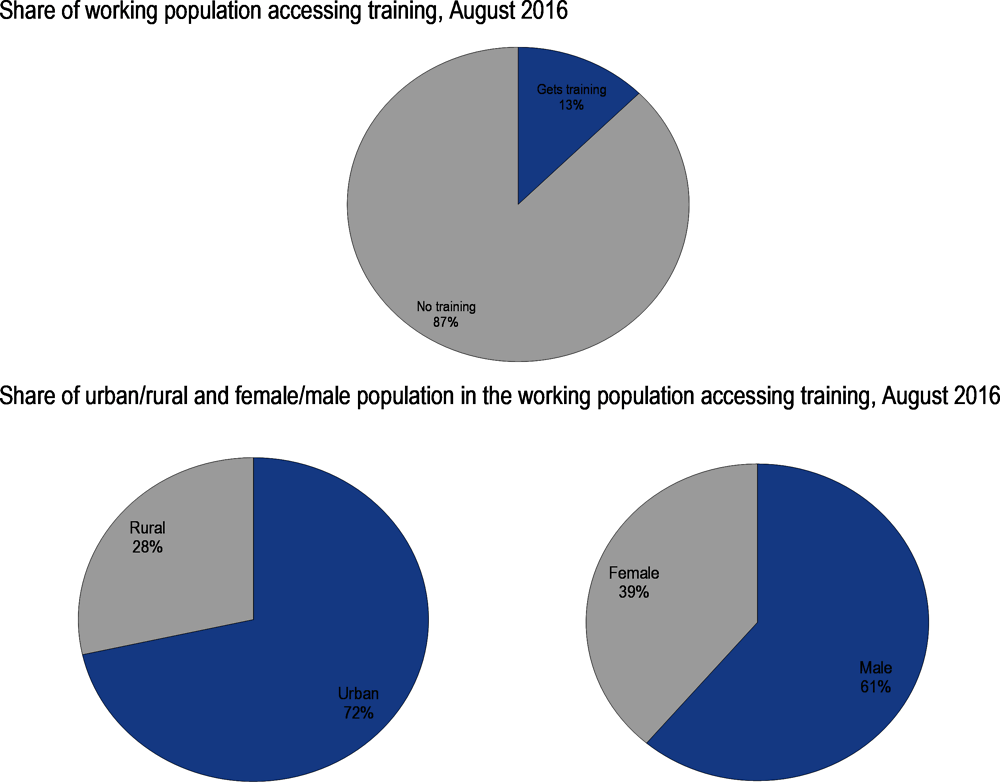

In addition, the largest majority of Indonesian workers do not have access to trainings, suggesting that workers’ skills development is rarely conducted (see Figure 3.4). Training can play an important role in upgrading people’s skills and fostering continuous skills development during adults’ work life. Substantial differences in access to trainings exist between rural and urban workers as well as between women and men. Out of the 13% of the working population who receives training, less than one third works in rural areas, and more than 60% of them are men. This suggests that not only adult skills development does not take place systematically, but also that rural workers and women are considerably less likely to undertake trainings than urban workers and men. Furthermore, access to training increases with educational attainment in Indonesia. World Bank estimates show that around 25% of the labour force attaining higher education has received training, compared to around 7% for those attaining senior secondary education, and close to zero for those with junior secondary, primary education or less (World Bank, 2019[22]). The availability of training also depends on firm size, with less than 8% of firms in Indonesia providing formal trainings to their workers, and small firms being almost ten times less likely to offer formal trainings than large firms (World Bank, 2015[23]).

3.2.1. Rural and remote provinces lack access to skills

People living in rural and remote provinces often lack basic education. About one in five people in Papua are illiterate, making it the province with by far the lowest literacy rate in the country. Illiteracy is also substantially higher in West Nusa Tenggara than the rest of the country. On the contrary, in other provinces, including North Sulawesi and the Special Capital Region of Jakarta, less than 1% of the population is illiterate (see Figure 3.5).

Enrolment in primary education has substantially increased over the last decades and is estimated today at more than 90% across all Indonesian provinces, except for Papua where the net enrolment rate in primary education stands at only 79.2% in 2019. However, enrolment gaps across provinces become wider at the secondary education levels. Net enrolment in junior high school ranges from more than 85% in the provinces of Aceh and Bali to 57.2% in Papua, and it is below 70% in several remote regions. Similarly, enrolment rates in senior high school can be higher than 70% in Bali, Riau Islands and Aceh, while they amount to 44.3% in Papua and less than 55% in Central Kalimantan, East Nusa Tenggara and West Kalimantan (Statistics Indonesia, 2020[24]).

Differences in enrolment rates generate disparities in the expectation of schooling years. In the Special Region of Yogyakarta, children of school entrance age can expect to receive more than 15 years of schooling, as compared to 10.5 in Papua and less than 12 years in the Bangka Belitung Islands, resulting in a differently skilled workforce. These different expectations reinforce regional development disparities across provinces, with poorer and more remote provinces developing a workforce with lower skills, which will in turn negatively affect local productivity and economic growth. Disparities in education are also reflected in the different performance of students across provinces. While a PISA score by province is not available, the breakdown by villages and large cities undertaken as part of the 2012 PISA survey shows that the performance difference between the two is higher in Indonesia than in other developing countries (see Figure 3.6). Acknowledging the large gaps in access to education, some cities have taken initiatives to make education accessible for all and better aligned to the labour market (see Box 3.2).

The city of Surabaya, located in East Java, faces several challenges related to poverty, with more than 164 000 people in the city living below the poverty line. The city has therefore concrete made efforts over the last years to improve learning outcomes of the population, and specifically target disadvantaged groups As an acknowledgement of the city’s efforts, Surabaya was one of sixteen cities in the world to receive the UNESCO Learning City Award in 2017. Cities were selected by an international jury based on the achievements made in promoting lifelong learning and education in their communities.

Surabaya has recently undertaken several initiatives to promote access to education and foster inclusion. For example, access to schools has been made free in the city, and the number of facilities providing learning opportunities, such as libraries, has been increased to foster accessibility to learning. Free ICT literacy and language classes are provided by the Broadband Learning Centre and the House of Languages centre in the city. The latter brings together 85 volunteer teachers who teach 13 different languages to more than 2 200 visitors per month. The provision of free online tools has also been prioritised with the creation of Wi-Fi hotspots to ensure everyone can access the internet. The Surabaya Education Department portal provides information on schools, the education system, as well as free courses and academic journals available on line. A website offering information on the healthcare system in the country as well as information on local hospitals has also been created.

Initiatives also exist to motivate students to remain and succeed in education in Surabaya. For example, a literacy competition between districts is organised every year in the context of the Surabaya Akseliterasi programme. Annual festivals, such as the Budaya Pustaka, and the Surabaya Cross Culture, Folks and Art Festival are organised to promote a lifelong reading culture, as well as local culture and arts. The city has also established community-based learning groups (Layanan Kelompok Belajar), targeting people who are unable to continue formal education. The groups receive funding from the city and, as of August 2017, there were 36 such groups operating in the city. Students undertaking informal education receive prizes and awards during the Widya Wahana Pendidikan, a fair and ceremony celebrating achievements of VET and community-based learning groups of students. Another initiative, known as Tantangan Membaca, was launched in 2015 to increase students’ interest in reading, making reading a daily habit and promoting “lifelong reading”. As part of the initiatives, students were challenged to read an amount of extracurricular books of their choice. Successful students received a certificate from the Surabaya Education Department.

Source: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2017[25]), Surabaya, https://uil.unesco.org/case-study/gnlc/surabaya (accessed on 19 June 2019); UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2017[26]), Unlocking the potential of urban communities, volume II: case studies of sixteen learning cities, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000258944 (accessed on 7 February 2020); Case study interviews.

3.2.2. The on-going COVID-19 pandemic crisis poses further challenges to access to education in rural and remote provinces

As the Government of Indonesia has established that work and study should take place from home as of mid-March 2020, in response to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, provinces are differently equipped to undertake remote learning. Indonesia’s internet penetration amounted to about 47.7% in 2019, and it is almost half that of Malaysia. Access to digital technology is uneven across provinces, with internet penetration strongly correlated with income per capita and poorer regions having lower rates. Large population centres such as Jakarta and Yogyakarta on the other hand have a penetration rate above 45% (McKinsey&Company, 2016[27]).

In addition, students in rural and remote provinces tend to be substantially less ICT-ready than their peers elsewhere in Indonesia. While in provinces such as the Special Region of Yogyakarta and the Special Capital Region of Jakarta the almost totality of 15-24 year-olds posses basic ICT skills, less than one in three do so in Papua (see Figure 3.7). The combination of lower internet penetration and ICT-readiness of youth in some areas might suggest that some provinces will struggle more than others to ensure the continuity of schooling through remote and distance learning platforms.

Vocational Education and Training (VET) can provide students and workers across Indonesian provinces with the skills needed in local labour markets, fostering inclusive growth and reducing disparities both within and across provinces. Both several ministries and local governments play a role in the development and delivery of vocational education and training in Indonesia. Table 3.2 provides an overview of the VET system in the country.

Vocational education in Indonesia can take place at different levels, and consists of both formal and non-formal tracks. Indonesian students aged 16-18 have the opportunity to take on upper-secondary formal vocational education, while non-formal vocational trainings mainly target jobseekers without formal vocational education, workers whose jobs have become obsolete or workers who may want to advance in their career (World Bank, 2019[22]). Upper-secondary vocational education is mainly provided by vocational high schools (Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan, SMKs), which are overseen by the Ministry of Education and Culture, and provide vocational education in several areas, including information and communication technology, engineering, business and management, agri-tourism, arts and crafts. Vocational education is also provided by Islamic vocational schools (MAKs). Formal vocational education is also offered by several tertiary education institutions, including academies, polytechnic universities and schools of higher learning (Bai and Paryono, 2019[28]). On the other hand, non-formal vocational education and training is mainly provided by work training centres (Balai Latihan Kerja, BLKs), supervised by the Ministry of Manpower. The ministry also oversees productivity training centres (PCTs), offering trainings to support productivity improvements within SMEs. Non-formal vocational education is provided by private institutions as well. Private work training providers (Lembaga Pelatihan Kerja Swasta, LPKS) and private courses and training centres (Lembaga Kursus dan Pelatihan, LKP) provide trainings, and they are regulated by the Ministry of Manpower and the Ministry of Education and Culture respectively (Malik, Jasmina and Ahmad, 2019[29]). Around 16 different line ministries, along with local governments, also have direct implementation control or oversight of many of these training institutions, with limited co-ordination among themselves (World Bank, 2019[22]).

3.3.1. Vocational high school (SMKs)

Upon completion of junior secondary education, students can choose whether to enrol in upper secondary vocational (SMK and MAK) or general high schools (SMAs). Both programmes last three years, but for the SMK there is also the possibility to undertake a four year programme (SMK plus). SMA/SMK/MAK graduates receive a national certificate of secondary education upon successful completion of a final exam. SMKs provide the choice among different majors, of which the most popular are technology and industry and business management, while SMAs offer majors in natural science, social science and languages. Vocational and general high school only have in common the teaching of English and Indonesian languages. Upper secondary education requires students to pay an annual fee, which changes based on whether the school is public or private. SMAs are generally more expensive than SMKs. Data from the Ministry of Education and Culture shows that there were around 14 000 SMKs in 2018, almost 75% of which were private (Malik, Jasmina and Ahmad, 2019[29]).

A stigma towards vocational schools is present in Indonesia, as SMKs are often perceived as “second class” institutions, mainly targeting poorer students who cannot afford higher general high school fees. SMA and SMK students’ characteristics differ - SMA students tend to have better results in national examinations (e.g. EBTANAS) and a higher socio-economic status. The higher applicant to entrant ratio of SMAs suggests that there is a general preference for high school compared to vocational education. Students to college educated parents tend to attend SMKs, while rural students are less likely to attend public general education (World Bank, 2010[30]). Research shows that students with high test scores are more likely to attend public general high schools, while children to highly-educated parents tend to choose private general high schools. Private vocational schools are seen as the last resort, appealing to students with low-test scores and the least educated parents (Newhouse and Suryadarma, 2011[31]). The upper secondary education system in Indonesia appears to be compartmentalised, with SMA and SMK emerging as two parallel education paths where students have difficulties in moving from one to the other. While SMA students can continue their studies with tertiary education, for SMK students it is often hard to enter university. SMAs also provide better employment prospects, with less than 8% of SMA graduates who were unemployed in 2017, as compared to more than 11% for SMK graduates. SMK students therefore find themselves in the position of not being able to enter university, as they have not attended high schools, while also having more difficulty in finding a job as compared to their SMA peers.

The comparison between SMK and SMA shows that, although the former have expanded over the last decade, graduates from the latter still achieve better education and labour market results. The number of students enrolled in SMK and SMA is quite similar, but difference emerge when looking for example at indicators of participation, retention and unemployment. The Government of Indonesia has recently stepped up efforts to expand vocational education and increase its effectiveness in providing students with the skills needed in the labour market and place them into jobs (see Box 3.3).

In September 2016, the President of Indonesia issued a “Presidential Instruction” aimed to improve the quality and competitiveness of the Indonesian workforce, called “SMK Revitalisation”. The strategy was adopted to equip the Indonesian workforce with the skills needed for an evolving labour market, where technological progress heavily affects business processes as well as skills requirements, fostering the acquisition of soft and transferrable skills. These include thinking skills, work-related skills, instrumental skills (e.g. data collection) and relational skills (e.g. integrity, discipline, responsibility).

Main objectives of the strategy include among others:

Revitalising vocational schools supporting the development of national priorities (e.g. food security, energy, business and tourism, maritime sector), with a focus on the Eastern provinces of Papua and West Papua;

Advancing the development of an SMK model which is based on strong industry-linkages;

Development of labour market skills needs assessment and adjustment of SMK curricula accordingly;

Improving the quality and infrastructure of SMKs;

Elements of the initiative include the need to better harmonise SMK curricula with competencies needed in the labour market and enhancing co-operation between public institutions involved in the development of VET and the business sector.

Source: Ministry of Education and Culture (2016[32]), Presidential Instruction Number 9 Year 2016 on Revitalizing TVET Schools (SMK) in the framework of Improving the Quality and Competitiveness of Indonesian Human Resources (Instruksi Presiden Nomor 9 Tahun 2016 Tentang Revitalisasi SMK dalam rangka Peningkatan Kualitasdan Daya Saing Sumber Daya Manusia Indonesia), https://www.kemdikbud.go.id/main/blog/2016/09/presiden-jokowi-keluarkan-inpres-tentang-revitalisasi-smk (accessed on 13 June 2019)

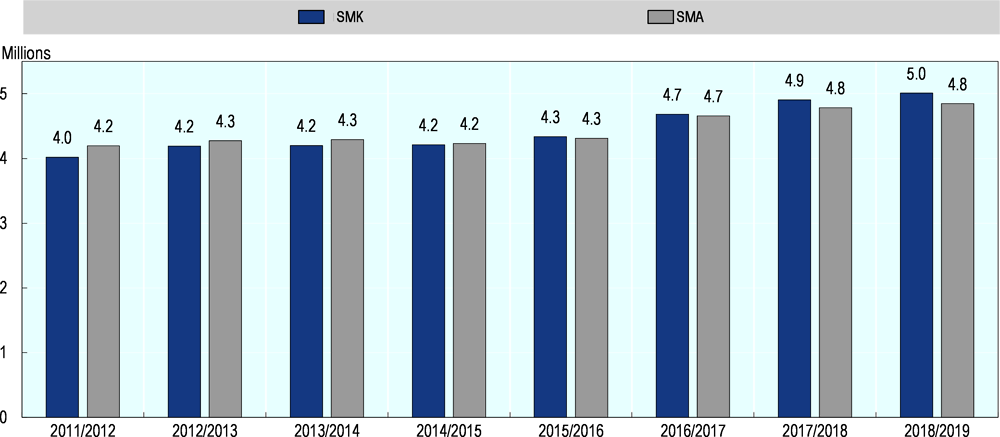

3.3.2. Participation in vocational high schools has been increasing in Indonesia

Enrolment in vocational schools has seen a constant increase over the last decade, taking over general education in enrolment numbers (see Figure 3.8). In the academic year 2018-2019, the total number of SMK students amounted to more than 5 million, up from 4 million in 2011-2012. The share of upper secondary education students enrolled in vocational education has therefore increased from 49% to 61% between the academic years 2011/2012 and 2018/2019. Also the number of SMA students has increased over the same period. Furthermore, while there were more SMA than SMK students in 2011-2012, the opposite is true for the academic year 2018-2019, where SMK students outnumber SMA students by around 200 000. The objective of the government is to increase the ratio of SMK to SMA students to 70% by 2025.

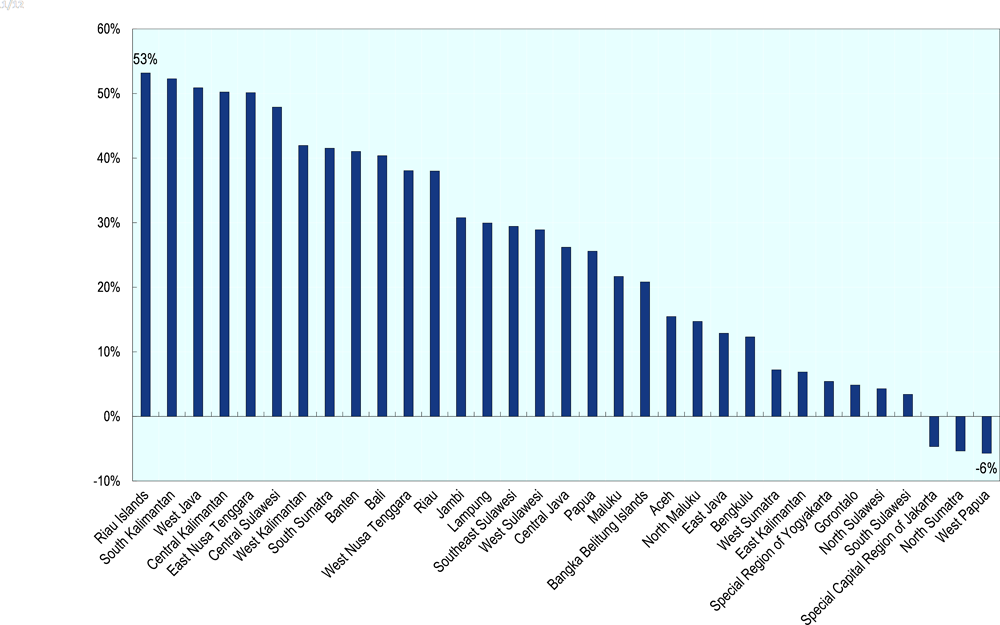

The increase in the number of SMK students has been substantial in Riau Islands, South Kalimantan, West Java, Central Kalimantan, East Nusa Tenggara and Central Sulawesi, standing at around 50% over the 2011-2012 to 2018-2019 period. On the other hand, a few provinces have seen the number of vocational students decrease over the same period. This is the case of the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (-5%), North Sumatra (-5%) and West Papua (-6%) (see Figure 3.9). The number of new entrants in the academic year 2018-2019 amounted to 1.77 million. New students mainly enrol in private SMKs as compared to public ones, which had 985 000 and 783 000 new entrants respectively in 2018-2019.

The number of repeaters, defined as students repeating more than once the same grade, is rather low. Only 19 000 out of 5 million SMK students are repeaters, corresponding to a repetition rate of 0.29%. Student drop-outs stand at 25 357, or 0.52%, between 2017-2018 and 2018-2019, down from 72 744 between 2015-2016 and 2016-2017. The number of graduates in 2018-2019 amounted to 1.5 million, up from 1.3 in 2016-2017 (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019[34]). However, repetition rates vary across provinces, with rural and remote provinces in the east, such as Papua and West Papua, where rates are nine and seven times the national average respectively. Similarly, drop-out rates in remote provinces, such as North Maluku (2.97%), Papua (2.31%) and Gorontalo (2.07%), are much higher as compared to central provinces such as Bali (0.06%), the Special Region of Yogyakarta (0.07%) and the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (0.16%). In addition, students’ performance seems to vary from public to private schools, with the latter accounting for 60% and 68.8% of total repeaters and drop-outs (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019[34]).

Overall, repetition rates of SMK students are only slightly higher than for SMA students across Indonesia. On the other hand, the difference in drop-out rates between SMK and SMA is more pronounced, as drop-outs average 1.57% and 0.33% in SMK and SMA respectively. Drop-out rates are higher for SMK than SMA students in almost all provinces (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019[34]) (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019[35]) (see Figure 3.10).

3.3.3. The government has invested in increasing the number of schools to boost the overall supply of skills

While there were 10 256 vocational schools in Indonesia in 2011/2012, their number has gradually increased over the recent years. As of the academic year 2016/2017, there were more vocational than general high schools in Indonesia (see Figure 3.11). Vocational schools can be private or public organisations, with the former overwhelmingly outnumbering the latter (75% to 25%). Every year, 1.5 million students graduate from these schools. The provincial government grants a permit to eligible schools, allowing them to provide vocational courses. The development of new vocational schools has continued over the past years, with more than 1 000 new vocational schools established since 2018.

3.3.4. Work training centres (BLKs)

Non-formal vocational training in Indonesia is mainly provided by work training centres (BLKs), under the responsibility of the Ministry of Manpower. There are also private work training providers (LPKS) and private courses and training centres (LKPs). The latter are regulated by the Ministry of Education and Culture.

There are 305 BLKs in Indonesia, of which 17 are directly operated by the Ministry of Manpower, while the remaining part is operated by local governments. In addition to public BLKs, there are more than 8 900 private training providers, including LPKS as well as 245 private BLKs specialising in preparatory training for workers to go and work overseas. Finally, there are more than 19 000 LKPs, providing ad-hoc courses and trainings (Malik, Jasmina and Ahmad, 2019[29]). Training centres mainly target jobseekers without formal vocational education, workers whose jobs have become obsolete or workers who may want to advance in their career. Originally developed to serve the manufacturing industry in the 1970s and 1980s, targeting poor people with low educational attainment, BLKs today have the objective of providing relevant trainings to students and jobseekers to develop skills and competences needed in the labour market. Examples of subjects taught by BLKs include garment and apparel, automotive-related trainings and ICT, as well as welding and electronics.

Although it has increased over recent years, the popularity of BLKs across Indonesia is rather limited, considering the size of the population that could benefit from such trainings. In 2018, around 150 000 people were trained in training centres managed from the Ministry of Manpower, up from around 90 000 in 2017. The government targeted to reach around 280 000 trainees in 2019. Although efforts have been made to improve the context for BLKs, training centres often lack facilities and have outdated equipment, compromising the relevance of training provided (World Bank, 2010[30]). The number of BLK certified graduates is also reportedly reduced by the limited number of assessors and staff able to train trainers. In addition, monitoring of training outcomes does not take place in a systematic way. Efforts have been made to develop competency standards and link them to the Indonesian National Qualification Framework, but practical challenges remain. Challenges linked to accreditation and quality assurance of training institutions are often pointed out as major challenges hampering the effectiveness of trainings across provinces. Quality assurance is often identified as an issue especially for private sector-provided trainings (Malik, Jasmina and Ahmad, 2019[29]).

3.3.5. Indonesian National Work Competency Standards (INWCS)

Vocational training in Indonesia is developed based on the Indonesian National Work Competency Standards (INWCS). The INWCS have been established to describe the competency standards that underpin a range of occupations. They apply to companies within the same sector across Indonesia. Standards are reviewed periodically to determine their validity towards new developments and changes in job requirements. Reviews take place at different times for each profession and depend on the speed of change in job requirements in each field. For example, the review of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) standards takes place more often than the Metal and Machinery sector. INWCS are the reference for the development of competency-based programmes as well as for the professional competency certification system. INWCS are jointly developed with stakeholders in each sector.

In the development of INWCS, particular attention is devoted to standard requirements for professions characterised by risks linked to occupational safety and health (OSH), such as in the health sector, engineering and chemistry. Priority is also directed towards professional fields where disputes may arise, such as advocacy and accounting, as well as to professions linked to the preservation of national heritage, such as crafts, arts and culture. INWCS were initially formulated on the basis of the Regional Model Competency Standard (RMCS) format, which was introduced through the International Labour Organization (ILO) Asian and Pacific Skill Development Programme (APSDEP) in 1998. The ILO formulated the INWCS to answer the following questions: What is a worker expected to do based on his/her job duties? How should a worker’s performance be measured? How should achievement and failure to perform be measured?

The development and harmonisation of the INWCS has not been budgeted by sector yet, and some training programmes are still to be established. In addition to INWCS, Indonesian law also foresees Special Standards and International Standards. Special Standards are competency standards that only apply in the institution that sets them and/or to other institutions having direct links with it. This is the case of ASTRA and Microsoft Standards for example. Special Standards can become INWCS and therefore apply to all firms within a sector through the INWCS drafting process regulated by the Ministry. On the other hand, the International Standard is a competency standard set by international organisations/associations. International Standards apply internationally in many countries. This is the case of ISO standards and IMO standards, for example. International standards can be adopted as INWCS through a process regulated by the Ministry.

3.3.6. Indonesian National Qualification Framework (INQF)

The Indonesian National Qualification Framework (INQF) provides standards for graduates as well as education and training institutions to assess learning outcomes. It aims to equalise outcomes resulting from formal, non-formal and training education, as well as self-learning and learning acquired through on-the-job experience. Following the example of the European Qualification Framework (EQF), it also recognises and translates international workforce and students qualifications into the Indonesian qualification system. The INQF includes nine qualification levels (see Table 3.3). The incorporation of INWCS into the INQF is important to ensure harmonisation between education and employment outcomes. It is also important to facilitate the mutual recognition of qualifications with other countries.

3.3.7. Competency-based Training (CBT)

There are three types of Competency-based Training (CBT) programmes in Indonesia:

Qualification programmes. These programmes contain a number of competency units that correspond to a certain level of qualification, according to the INQF. Qualification programmes are mainly undertaken by low skilled workers aiming to upgrade their skills.

Occupational programmes. They contain competency units that relate to particular occupations or positions. The content of such units corresponds to the job description of a specific occupation. Such programmes can be general or specific, in case they only apply to certain companies and organisations. Occupational programmes are mostly undertaken in the context of job placement and career development.

Competency Cluster programmes. These programmes contain a mix of qualification and occupational competency units. These programmes are mostly done in the context of upgrading skills or meeting special needs.

CBT programmes can take place in both public and private BLKs. An accreditation process grants formal recognition to BLKs, enabling them to carry out CBT. Accreditation is voluntary and carried out by an independent Training Institute Accreditation (TIA) established by a Ministerial Regulation. Trainees who have successfully completed a CBT programme are entitled to receive a Training Certificate from BLKs as proof that they have successfully completed the training.

3.3.8. Competency certification

Competency certification is carried out through standardised tests following INWCS, international or special standards. The purpose is to provide recognition of competencies and skills to ensure quality. Certificates can be obtained by participants and/or graduates of job training programmes or workers who have acquired significant on-the-job experience. The following principles guide the competency certification process:

Measurability, providing clear benchmarks for competency certification. Therefore, competency certification can only be done for certain fields, types, and professional qualifications that have been set according to the applicable regulations;

Objectivity, ensuring that competency certification is carried out without bias. For this reason, it must be avoided as far as possible, the possibility of a conflict of interest in the implementation of competency certification;

Traceability, ensuring that the entire certification process from the beginning to the end must be clearly defined and can be easily, quickly and accurately be traced for surveillance and audit purposes. For this reason, competency certification must refer to certain rules or guidelines and the process must be well-documented;

Accountability, with the issuer of certifications who are responsible to the public both technically, administratively and juridically for the issuance of certifications.

Based on these principles, several institutions are involved in the competency certification process, including:

The National Agency For Professional Certification (NAPC), that works as the "Authority Body";

Professional Certification Institutions (PCI) that have obtained licenses from the NAPC, as executing institutions for competency certification (Executing Agency);

Competency Test Sites (CTS) that have been verified by PCI, as the place for conducting competency tests / assessments;

Competency assessors who have competency assessor certificates from NAPC, as competency test / assessment implementers.

Competency certification can take place with any of the above-mentioned CBTs. Depending on the needs and characteristics of the sector concerned, certification can be carried out through three different schemes:

First Party Certification Scheme (PCI-1), which is granted by an organisation or company to its own employees, on the basis of special standards and/or INWCS;

Second Party Certification Scheme (PCI-2), i.e. a competency certification carried out by an organisation or company towards employees of another company that is the supplier or agent of the organisation or company in question. It is usually done to guarantee the quality of supply of goods or services. This certification can use special standards and/or INWCS;

Third Party Certification Scheme (PCI-3), carried out by a Professional Certification Institution (PCI) which has obtained from NAPC the licence to issue national quality certifications. This certification uses INWCS or international standards.

Clarity of the process and certainty of the value of the certification are needed to ensure that competency certification further develops in Indonesia. Competency certification constitutes an important advantage for holders in the labour market, as it represents a fast track to access new jobs, advance in the career and obtain better remuneration in Indonesia. The Mutual Reconciliation Agreement ensures that competencies are recognised in other countries as well. Competency certification represents an important guarantee of work competences. Therefore, the implementation of competency certification must be subject to the rules of an internationally valid quality assurance system.

3.3.9. Apprenticeship training in Indonesia

Apprenticeship is a vocational education pathway that, combining both workplace and classroom-based learning, can play an important role in tackling informality in emerging economies and placing people to good jobs (OECD/ILO, 2017[36]) (see Box 3.4). Quality apprenticeships resulting from robust social dialogue and public-private partnerships can support young people to transition from education to employment, tackling the work-inexperience trap (International Labour Organization, 2012[37]). Apprenticeships take place in most sectors in Indonesia, across different enterprise sizes.

The vast majority of apprenticeships are informal agreements between employers and apprentices, although the number of formal apprenticeship agreements following the Ministry of Manpower’s regulation has steadily increased (ILO and APINDO, 2015[38]). Statistics on apprentices can also be limited, as apprenticeships are very widespread in micro and small, usually informal, enterprises (Smith and Kemmis, 2013[39]). While there is no clear information on the scope and objectives of informal apprenticeships, a 2011 ILO internal paper reported that 11 out of 13 MSMEs were training a total of 22 apprentices (ILO and APINDO, 2015[38]). Between 2007 and 2013, it is reported that a total of only 100 000 apprenticeships were registered according to the Ministry of Manpower regulation (Skjaerlund and Van Der Loop, 2015[40]). A common definition of apprenticeship does not exist in Indonesia, and the term used (pemagangan) could be applied to apprenticeships, internships and traineeships. The Ministry of Manpower defines apprenticeships as “A part of a training program that is conducted based on the combination of mentorship at training institutions and guidance by senior employees (in the workplace) in the process of production of goods or services at companies with the goal to master a certain set of skills” (APINDO, 2015[41]).

The International Labour Organization (ILO) defines apprenticeships as a form of “systematic long-term training for a recognised occupation that takes place substantially within an undertaking or under an independent craftsman and should be governed by a written contract… and be subject to established standards”. Given growing interest in apprenticeship programmes and broader work-based learning as a success factor in school-to-work transitions, it is worth noting that the term “apprenticeship” is increasingly used to describe a range of programmes that might be alternatively referred to as “traineeships”, “internships”, “learnerships” and “work placements”, depending on the country context.

As noted by the G20, “apprenticeships are a combination of on-the-job training and school-based education. In the G20 countries, there is not a single standardised model of apprenticeships, but rather multiple and varied approaches to offer young people a combination of training and work experience” (G20, 2012[42]). The common feature of all programmes is a focus on work-based training, but they may differ in terms of their specific legal nature and requirements. Apprenticeships in modern industrialised economies typically combine work-based training with off-the-job training through a standardised written contract that is regulated by government actors. These programmes usually result in a formal certification or qualification. The nature of apprenticeships necessarily differ based on the institutional and structural features of the local, regional, national and supra-national vocational education and training system. Throughout this report, we will refer to apprenticeships that occur both during and following compulsory secondary education. The case studies depict employment programmes that are regulated by law and based on an oral or written apprenticeship contract, where apprentices were provided with compensatory payment and standard social protection coverage.

Source: OECD/ILO (2017[36]) Engaging Employers in Apprenticeship Opportunities: Making It Happen Locally, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264266681-en.

Apprenticeships have taken a more prominent role in Indonesia. In 2016, a National Apprenticeship Program Movement was launched, aiming to tackle skills mismatch and improve school-to-work transitions by promoting apprenticeships. The Ministry of Manpower is in charge of developing policies to regulate apprenticeship at the national level. Provincial/city-level governments raise awareness of apprenticeships across companies in their area of competence and provide training and supervision to companies implementing apprenticeships. The Employers’ association of Indonesia (APINDO), which brings together labour unions, companies and professionals, shares information among its members, promotes good practices and participates in tripartite dialogues and co-operates with the Ministry of Manpower and the Apprenticeship Forum. Other stakeholders involved in the development of apprenticeships include trade unions, vocational training institutions and professional certification bodies. The Government has established a funding scheme to encourage companies to implement apprenticeship programmes, aimed to cover the basic needs to implement apprenticeship programmes. To apply for the subsidy, companies have to contact the local government division in charge of employment by submitting the companies’ apprenticeship programmes or becoming members of Apprenticeship network co-ordination forums (FKJP) that are available in several provinces and regencies/cities (APINDO, 2015[41]).

3.4.1. The governance of the vocational education and training system is complex and managed by a number of ministries and local governments

The decentralised governance structure in Indonesia has placed substantial responsibilities for vocational education in the hands of local governments. However, the central government retains an important role given that the ministries of Manpower and Education and Culture are directly involved in the development of education and training curricula as well as qualification standards. This results in a complex multi-governance structure, where roles and responsibilities for vocational education and training are sometimes not clearly defined or overlapping. In addition, vertical and horizontal co-ordination, between different levels of government and different ministries is often challenging, as a systematic co-ordination mechanism for vocational education and training is not in place.

A challenge for Indonesia is to transform the current skills training system, characterised by various skills training providers operating according to their own systems, into a national skills development system (World Bank, 2011[43]). The absence of a clear distinction between vocational programmes and the weak co-operation between SMKs and BLKs results in an overall VET system that is not coherently harmonised. Recent efforts have been made to foster co-ordination and improve the quality of vocational education and training initiatives in Indonesia. The Skills Development Centres (SDCs), piloted in several cities and provinces in Indonesia, bring together different actors involved in the development and provision of vocational education and training, as well as jobseekers and the business community, to improve co-ordination and develop better programmes (see Box 3.5).

The Ministry of National Development Planning (BAPPENAS), in collaboration with the Ministry of Manpower, the Ministry of Industry and the Ministry of Education and Culture, has set-up pilot Skills Development Centres (SDCs), bringing together industry representatives, policy makers, academia, vocational schools and training centres to map local labour market needs, available trainings and vacancies. The objective of such centres is to enhance co-ordination among different actors to tackle labour market issues, facilitating matching between labour demand and supply, enhance productivity and lower the share of jobseekers. SDCs are forums for communication, co-ordination and synchronisation of programmes and activities to improve workforce skills, improving workforce quality across provinces. The SDC model was developed by Bappenas in response to the President Joko Widodo's policy to revitalise vocational education and training.

SDCs have been piloted in three cities (Surakarta, Denpasar and Makassar) and four provinces (North Sumatra, Banten, East Java and East Kalimantan). Several SDC meetings took place in 2017 and 2018 to discuss and map vocational schools and training centres, gather the feedback from industries, develop a database of jobseekers and identify competency standards to be used in trainings. Each SDC met around 10-15 times in 2017 and 2018, but only three and seven times in East Kalimantan and North Sumatera.

The number of vocational schools and training centres participating in SDCs varies substantially from one province to the other. For example, in the city of Surakarta, in Central Java, the SDC gathers 15 schools and training centres and almost 50 companies are being engaged, of which 7 from the textile industry, 11 from the tourism and hospitality sector, 10 operating in trade and finance, 5 from the furniture sector, 4 from the food and beverage industry and 2 operating in the automotive sector.

Source: Information provided by the Ministry of National Development Planning (BAPPENAS).

Local governments play a relevant role in education policy in Indonesia. Primary and secondary education falls under the responsibility of the city-level government, while provincial governments are responsible for upper secondary education. Public universities are managed by the central government. The responsibility for managing SMKs was moved from cities to provinces in 2017. However, the central government is directly involved in the development and delivery of vocational education. The Ministry of Education and Culture transfers more than 60% of its budget to local governments, both at the provincial and city level. For provinces, the transfer is operational for SMAs, SMKs, teacher allowances and salaries as well as physical infrastructure. Cities autonomously decide how to allocate their overall education budget. The central governments devolves the budget based on indicators such as number of students and schools per province. Local governments directly manage the large majority of training centres in Indonesia. Several ministries and institutions are involved in the development and delivery of vocational training programmes. The Ministry of Manpower plays a leading role, by directly managing 17 BLKs and 2 productivity training centres (PTCs), while several other ministries manage training centres in their respective area of competence. In addition to public VET, thousands of private institutions spread across the country offer trainings.

Within the Ministry of Manpower, VET is managed by the Directorate General of Training and Productivity (DGTP), which is in charge of overall formulation and implementation of policies aiming to increase labour competitiveness and productivity in Indonesia. The Directorate directly implements policies in the field of job training and is responsible for monitoring the quality of training institutions across the country. It also develops norms, standards and regulations, and provides technical guidance as well as monitoring and evaluation on competency standardisation. The DGTP consists of one Secretariat, supported by five Directorates. Vocational training is carried out within the National Job Training System, whose stated objective is the creation of a competent, professional and productive workforce. Every worker can take part in job trainings based on their initial skills level, and acquire new competencies. The main components of the National Job Training System are the INWCS and the INQF, the CBT programmes, and the Professional Competence Certification.

3.4.2. The employment outcomes of vocational students have remained uneven

Despite the increased government investment in vocational education, the employment outcomes for vocational students is worse than for people attaining other levels of education (see Figure 3.12). Data from Statistics Indonesia show that SMK graduates have higher unemployment rates than SMA graduates, with 11.4% and 8.3% of the economically active population with such degrees being unemployed in 2017 (Statistics Indonesia, 2018[33]). The figure for SMK graduates also worsened over the last decade, as in 2012 SMK graduates accounted for 10% of total unemployment, slightly higher than 9.7% for SMA graduates.

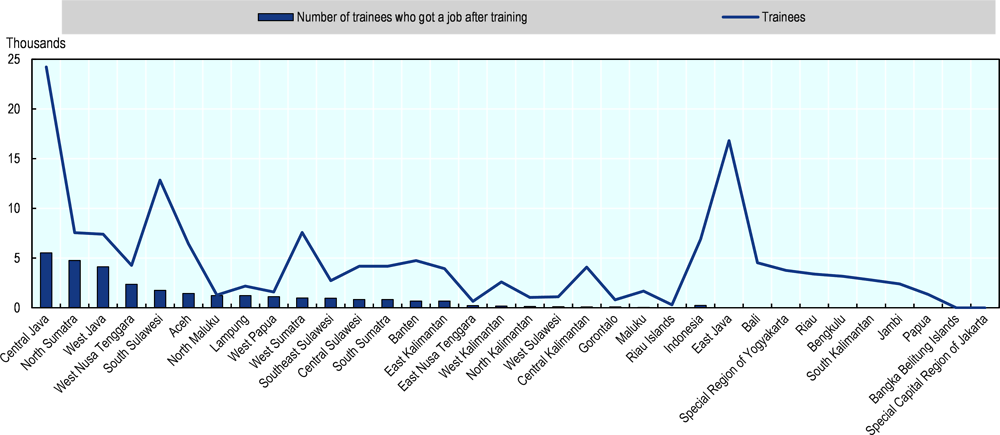

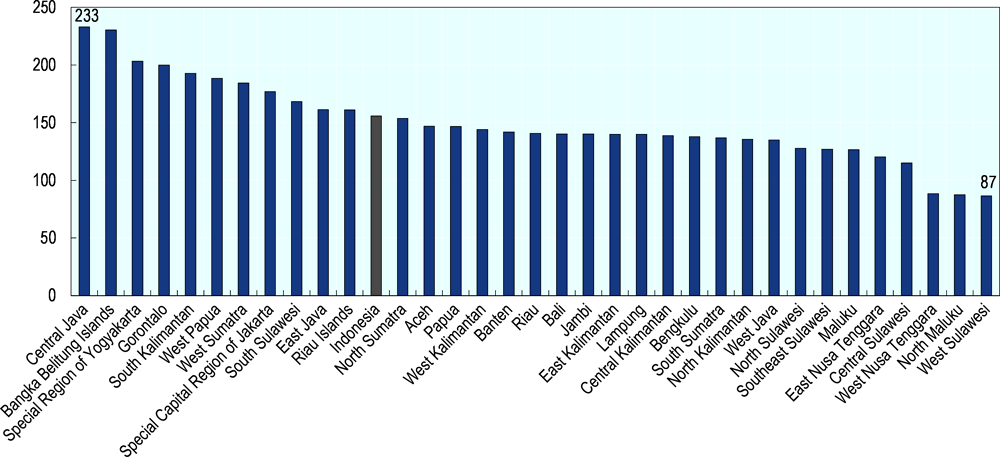

A challenge for monitoring the trends and impact of vocational training centres across provinces in Indonesia is that some of them do not report data on the number of trainees and their employment outcomes. According to the data provided by the Ministry of Manpower, there was a total of 149 087 trainees in public BLKs in 2018, up from 91 425 in 2016. The largest number of trainees are based in Central and West Java. The number of people who find a job after receiving a training in a BLK averages 20% at the national level, slightly lower than in 2017, when it amounted to 26%. Vocational training centres in the province of North Maluku have the highest share of trainees who get a job after training, amounting to 95% in 2018, while only 3% of trainees got a job in Maluku and Central Kalimantan in the same year (see Figure 3.13). Data on several provinces, including East Java, DKI Jakarta, Bali, Papua and West Papua, are not available.

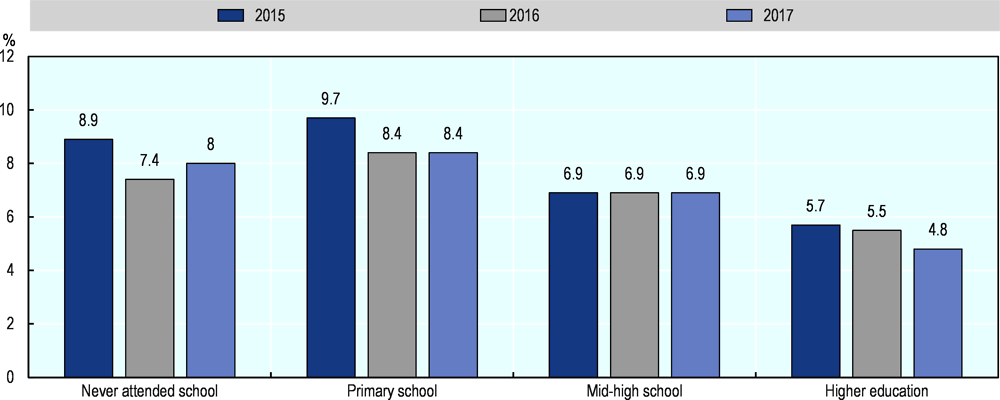

In addition, Indonesian youth also struggle with chronic levels of underemployment, as captured by the number of people working fewer hours than desired. Underemployment is pervasive among 15-19 and 20-24 year olds (Gunawan, 2018[44]). Around 7% of middle-high school graduates are underemployed, lower than those who never attended school or attended primary education, but higher than those attaining higher education (see Figure 3.14). Underemployment risks trapping young people in low-paid, informal jobs which fail to fully utilise their skills, and can result in significant social and economic costs.

3.4.3. Apprenticeships are viewed as a negative training pathway

A challenge hampering apprenticeships from leading to the development of a skilled and job-ready workforce in Indonesia is the fact that they tend to be still perceived as “cheap labour” rather than an investment in future workforce productivity. Apprenticeships usually last between one and three months, and apprentices are paid around 75% of the minimum wage salary. The provision of apprenticeships in Indonesia varies across provinces. The Ministry of Manpower collects data from each province on the number of official apprenticeship agreements, although reporting from the provinces might not always be accurate (ILO and APINDO, 2015[38]).

The Special Capital Region of Jakarta is the province with the largest number of apprenticeship agreements signed, amounting to 5 253 in 2013, followed by West and East Java with 2 826 and 2 168 respectively. In more rural and remote provinces, the number of apprenticeship provided is very low, for example only 19 and 46 in Maluku and Gorontalo in 2013. In the Province of East Java, APINDO started targeted programmes involving 880 apprentices in 2018, as a result of the collaboration between the Ministry of Manpower and the Province, consisting of a month of training following by five months on the job. Training programmes are jointly developed by local SMKs as well as local industry associations to define standards and competences needed (see Box 3.6).

The Employers’ Association of Indonesia (APINDO) is an employers’ organisation under the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce (KADIN), overseeing employment and industrial relations issues (Beson, Zhu and Gospel, 2017[45]). APINDO is the only organisation authorised by the Chamber of Commerce to do capacity building around human resource development. It is composed of individual enterprises and associations, which can be regular or extraordinary members. APINDO also provides inputs to the provincial government concerning human resource planning.

Since 1996, the East Java branch of APINDO has been active in promoting the development of apprentices among its members. It reported almost 900 apprentices across sectors in the province in 2018. The apprenticeship programme lasts six months, of which a month dedicated to trainings and five months on-the jobs. To set-up the training offer, APINDO works with local SMKs, and defines standards and competences needed with its members.

Despite relevant efforts to motivate members and bring together stakeholders to establish apprenticeships, a challenge for APINDO is its limited budget and membership, resulting in limited capacity to develop apprenticeships. Case study interviews with the Head of the APINDO East Java office led to the identification of the high cost for businesses as a constraint preventing them from investing in apprenticeships, as well as the lack of a culture of apprenticeships among businesses.

Source: Beson, Zhu and Gospel (2017[45]), Employers’ Associations in Asia : Employer Collective Action., Taylor and Francis, https://books.google.fr/books?id=YjwlDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 17 May 2019); Case study interviews.

3.4.4. Local VET curricula is often not aligned with employers skills needs

Local VET institutions often remain supply-side oriented (International Labour Office, 2015[46]). While initiatives have been launched over the years to increase the involvement of employers and industry organisations in the design, development and delivery of training, their actual involvement remains limited, resulting in programmes that do not provide students with the skills needed in the labour market.

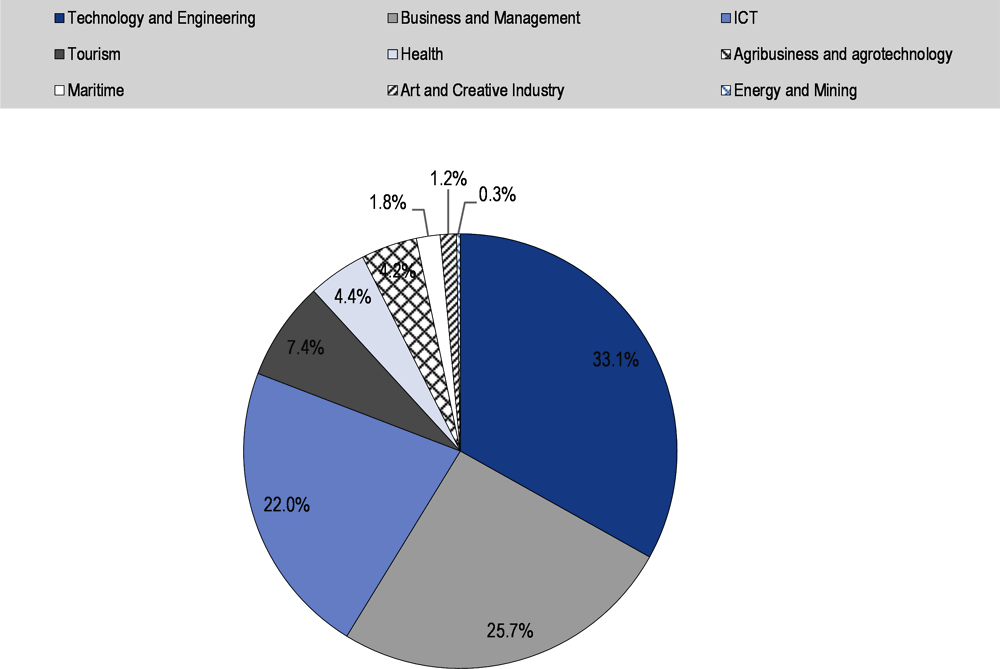

Vocational education curricula are designed and developed by the Ministry of Education and Culture in consultation with the Ministry of Manpower and the Ministry of Industry. About 144 different specialisations exist within the vocational high school system, across 9 general fields of study which include technology, energy, tourism, social care, agriculture, maritime studies, creative industries and business management. Provincial governments can then adapt the national curriculum to the specific local characteristics. The specific focus of each school is generally determined based on the demands of local students. In 2018, the large majority of SMK students were enrolled in technology and engineering (1.6 million), business and management (1.3 million) and information and communication technology (1.1 million), accounting for 33.1%, 25.7% and 22% of the total SMK student population respectively (Bakrun, 2018[47]) (see Figure 3.15).

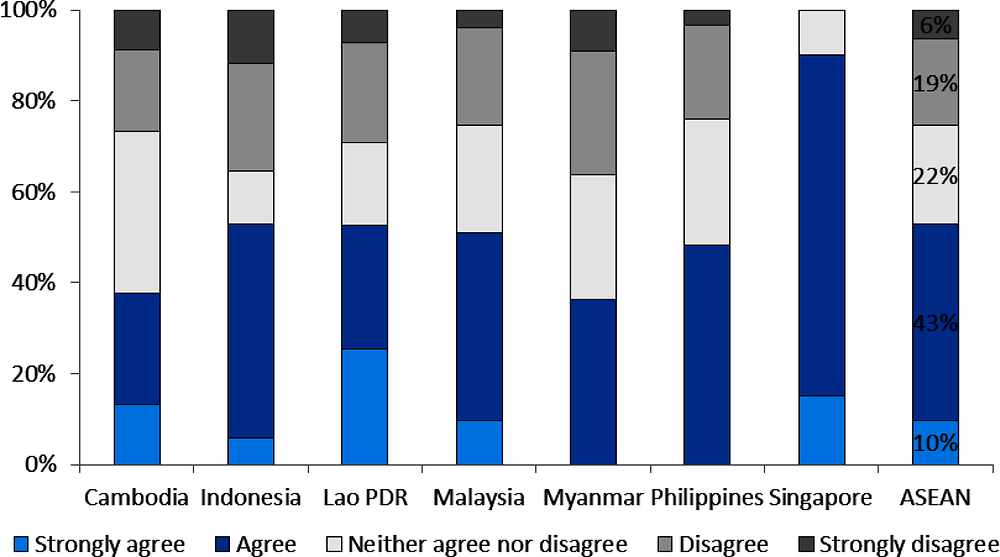

Furthermore, employer skills survey analysis shows that employers report large gaps in workforce skills. Looking at the ASEAN region overall, only around half (53%) of employers across the region agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that, “vocational education and training adequately matches their needs” (see Figure 3.16). Variation across countries in terms of employers’ agreement with the statement partly reflects wealth differences. For example, 90% of employers in Singapore agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, compared to just over one-third in Myanmar and Cambodia. In Indonesia, about 50% of firms agree or strongly agree with the statement that the TVET system meets their needs. About 10% firms reported that they strongly disagree that the TVET system meeting their needs, a higher proportion relative to the results from other ASEAN countries in the survey.

The poor quality and relevance of trainings has been identified as one of the main challenges hampering the potential of SMKs in Indonesia (OECD/ADB, 2015[48]). Employer surveys conducted by the World Bank in 2010 reported that SMK curricula were not based on industry needs and not keeping pace with industry needs, while facilities are often outdated (World Bank, 2010[49]). The private sector is rarely involved in the development of curricula, with collaboration taking place on an ad-hoc basis and left to the initiative of local school leadership. In addition, neither students nor businesses have a clear perspective on the skills that will be needed in the labour market once students graduate. Therefore, this results in uninformed vocational education decisions by students, and a lack of clarity for businesses concerning the characteristics of the workforce they will actually need. This can partly explain that more than 60% of the total SMK student population is enrolled in technology and engineering, business and management and ICT courses, while only a small share of students chooses to take courses in sectors such as tourism, agribusiness and marine studies. Pilot programmes have been introduced in several provinces in Indonesia to ensure that vocational education provides the skills students need in the local labour market, and to better match people to jobs (see Box 3.7).

The Link and Match programme was developed to foster co-operation between vocational schools and industries, with the objective of providing students with the skills needed in the labour market. The programme was founded in 1989, and refined over the years.

The programme integrates educational programmes in schools and skills development in the workplace, therefore supporting the development of a Dual Education System in Indonesia. Internships and industrial work practice programmes, which include activities such as curriculum validation, guest teachers from industries and competency tests, are examples of activities that take place as part of the Link and Match programme.

As of 2018, 1 537 SMKs had been linked to 568 industries in the provinces of East Java, Central Java, West Java, Aceh, North Sumatra, West Sumatra, Riau, Riau Islands, Jakarta and Banten.

Source: The Jakarta Post (2018[50]), Government continues to expand “link and match” program: Minister, https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2018/03/05/government-continues-to-expand-link-and-match-program-minister.html (accessed on 13 June 2019); Ministry of Education and Culture (2016[32]), Presidential Instruction Number 9 Year 2016 on Revitalizing TVET Schools (SMK) in the framework of Improving the Quality and Competitiveness of Indonesian Human Resources (Instruksi Presiden Nomor 9 Tahun 2016 Tentang Revitalisasi SMK dalam rangka Peningkatan Kualitasdan Daya Saing Sumber Daya Manusia Indonesia), https://www.kemdikbud.go.id/main/blog/2016/09/presiden-jokowi-keluarkan-inpres-tentang-revitalisasi-smk (accessed on 13 June 2019).

3.4.5. The quality of professional staff and teachers with local VET schools is under-developed

The number of vocational education teachers has doubled in Indonesia over the last decade. In 2011-2012, there was a total of 164 074 teachers, while in 2018-2019 the number of teachers in vocational schools amounted to 300 081. General high-schools have a slightly higher number of teachers, amounting to 310 906 in the 2018/2019 academic year. SMA teachers have better qualifications than their SMK peers, with 98% of them having a graduate degree or higher, as compared to 73.4% of SMK teachers. The majority of SMK teachers are employed in private vocational schools, while the opposite is true for SMA teachers (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019[35]) (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019[34]).

The recruitment process imposes the same requirements for both SMA and SMK teachers in order to be able to teach. This often results in better qualified teachers preferring to teach in high schools rather than vocational schools, due to higher salaries and reputation. On the other hand, industry and private sector representatives with no Bachelor’s Degree but extensive job experience are rarely involved in teaching in vocational schools. For vocational schools to improve their effectiveness, it will be crucial to ensure a good balance between teachers with an academic background and practitioners (Di Gropello, Kruse and Tandon, 2011[51]). Vocational teachers often lack teaching and work experience and their education is not as relevant as the workplace would require (OECD/ADB, 2015[48]). There are three categories of teachers in Indonesia: normative, teaching religion and history, adaptive, focusing on mathematics and science, and productive teachers, who have competency certificates for teaching vocational subjects. Only 22% of vocational teachers in Indonesia are qualified as productive teachers, while the majority of vocational teachers are normative and adaptive (Komariah et al., 2018[52]). Graduates from academic degrees are often recruited upon graduation to teach in SMKs. As they lack both in teaching and industry experience, and therefore resulting in teaching lacking pedagogical, didactical and occupational competences (Kadir, Nirwansyah and Ayasha Bachrul, 2016[53]). Programmes are being implemented across Indonesia to ensure that vocational teachers get the practical experience and skills needed to be able to teach effectively (see Box 3.8).

In addition, teachers in rural and remote provinces are often less qualified and absent from school. The supply of quality teaching and the lack of appropriate infrastructure are among the main factors contributing to regional disparities in education. Indonesia’s poorer and remote areas are characterised by higher teacher absenteeism, which is linked to higher student absence, drop-outs and lower learning outcomes. The challenge of providing access to education in remote areas compounds the issue of young people’s participation in schooling, particularly in communities characterised by low educational aspirations (OECD/ADB, 2015[48]). While the availability of teachers does not seem to represent an issue across Indonesia, as teacher recruitment continues to outpace student enrolment at all levels, the right incentives might not be in place to ensure quality teaching across provinces. The central government sets the number of teachers per province based on the number of students and schools, but recruitment and salaries are set by local governments, who are fully compensated by central governments transfers. This might create an incentive for local governments to increase the number of teachers regardless of their qualifications and competences (OECD, 2016[54]). Underdeveloped infrastructure hampers school participation in provinces characterised by lower population density. The shortage of school facilities in remote areas, such as the eastern provinces, makes the distance to school rather high for many communities.

The Swiss Foundation for Technical Cooperation (SWISSCONTACT), a Swiss non-profit-organisation, has launched a teacher internship programme to equip vocational teachers in the tourism sector with practical experience and understanding of tourism-related jobs, which they can better transmit to students. The tourism sector in Indonesia is characterised by labour shortages: compared to 707 600 vacancy needs, tourism SMK graduates amounted to only 82 171 in 2016. The WISATA Teacher Internship Programme (WITIP) was launched with the goal of updating teaching materials, aligning teaching methods with industry’s standards and building closer linkages with the tourism industry.

In 2015, the programme involved 14 teachers, 7 partner schools and 8 corporate partners from the tourism sector, while in 2016 it expanded to involve 23 teachers, 9 partner schools and 5 model schools and 10 corporate partners, and received government support. The programme allows participating teachers to spend one month in Bali. During the week, teachers undertake internships in one of the corporate partners in the tourism sector. Saturdays are instead devoted to discussion and sharing of experiences, capacity building trainings and outdoor trainings. Once finished the internship programme, teachers are evaluated by industry partners, and the results of the programme shared in schools.

Teachers who participate in the programme change every year to ensure most of them can participate. As a result of the programme, teachers are able to develop teaching materials using the experience gained during the internship.

In 2018, there were a total of 22 industries supporting the programme, consisting of ten well-known 4-5 star hotels in Bali and three in Makassar, as well as a national airline in Bali, and seven tour operators in Bali and one in Makassar. The WITIP programme generated a positive impact on the relationship between teachers, SMKs and industries. Some hotels in Bali participating in the programme contributed room and restaurant amenities to several SMKs to improve their in-house training.