7. Building future-focused and innovative mental health systems

Building higher quality and more efficient mental health care demands a focus on building the innovative and high-performing mental health systems of the future. A future-focused approach to mental health includes developing a strong mental health workforce for future generations, investments in research, a strong data infrastructure, and a commitment to innovation and integrating new ideas into mental health practice. At the same time, there is more to do to ensure that more people get access to what is already understood to be the best practice care available, and that this care is delivered in the most effective and efficient way possible. This chapter explores the approaches that OECD countries are already taking to build efficient and sustainable mental health systems, opportunities to maximise uptake of effective and innovative treatment and services, and areas where more investment of attention and resources are needed.

Just as in other areas of health care, building higher quality and more efficient mental health care, requires a focus on building the innovative and high-performing mental health systems of the future. A future-focused approach to mental health demands that steps are taken to ensure that a mental health workforce for future generations is being trained now, and that investments are made in research that will benefit populations in the years or decades to come. Innovative solutions, too, must be identified: leaps forward in health care, from the use of new technology and digital solutions, to personalised medicine and pharmaceutical advances, should be harnessed for mental health. At the same time, there is more to do to ensure that more people get access to what is already understood to be the best practice care available, and that this care is delivered in the most effective and efficient way possible. Both to maximise access to effective and efficient mental health care today, and to build innovative and sustainable systems for the future, robust information systems must be available to track progress and identify what works.

This chapter explores the approaches that OECD countries are already taking to build efficient and sustainable mental health systems, opportunities to maximise uptake of effective and innovative treatment and services, and areas where more investment of attention and resources are needed.

“A future-focused and innovative approach” is one of the six principles of a high-performing mental health system established by the OECD Mental Health Performance Framework (OECD, 2019[1]). A future-focused and innovative approach to mental health policies and care is essential for building a dynamic system today, for capitalising on the most promising new developments in health care and beyond, and looking forward to secure ever-improving mental health policies and services in the years to come. Specifically, “a future-focused and innovative approach” includes six sub-principles:

Are OECD countries investing in mental health research?

In recent decades mental health research has had low levels of attention and investment

Despite the significant and long-standing epidemiological and economic burden of mental disorders, mental health research has lagged behind many other areas, in terms of prioritisation, funding, and breakthroughs. Investment in research focused on mental and behavioural disorders has historically been low compared to overall burden of disease, and compared to other areas of health research.

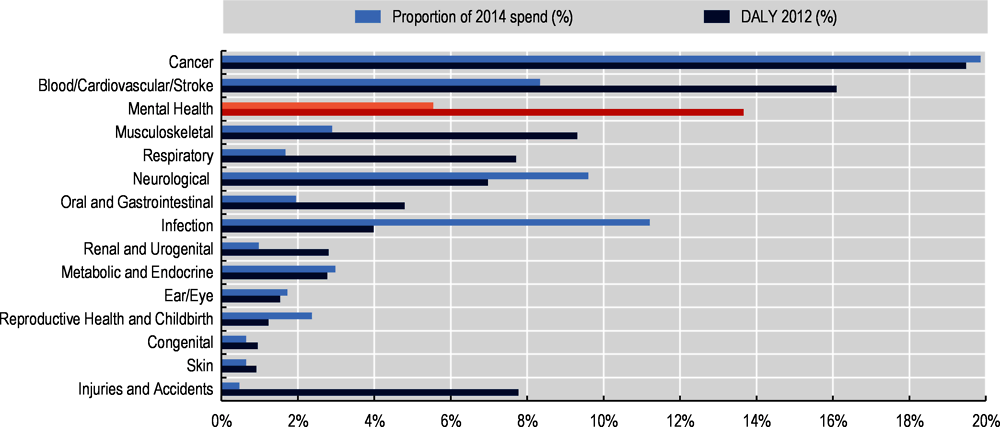

In Europe, the three year ROAMER project ran from 2015 to 2018 to create a roadmap for mental health, and found that mental health and well-being were under-represented both relative to the burden of disease, and to other health-related fields (Hazo et al., 2019[2]). As part of the ROAMER project the national research budget for mental health in 2011 in four countries, Finland, France, Spain and the United Kingdom, was identified and again a significant gap between research investment and DALY attributable to mental disorders was found (Hazo et al., 2017[3]). At the European level between 2007 and 2013 the EU spent EUR 373.3 million on mental health research, compared to EUR 802 million on neurological and neurodegenerative research, despite the epidemiological and economic burden of mental disorders being twice that of neurological and neurodegenerative diseases (Hazo et al., 2016[4]). Research in Australia also pointed to low levels of funding for mental health research (Christensen et al., 2011[5]). In the United Kingdom, a mapping of funding across areas of health research from 64 funders found that spending on mental health research as a percentage of total research spending was significantly lower than the relative DALY burden of mental health conditions in the United Kingdom, but had grown slightly from 2002 to 2014 (Figure 7.1).

While looking to establish the extent of investment in mental health, especially at an international level, it is difficult to take stock of different funders, from the governments to research institutes as well as charitable or foundation-based investors, and the pharmaceutical industry. Some national analysis from the United Kingdom in 2017 suggested that in fact mental health research investments across all actors was below the relative burden of disease (Department of Health, 2017[7]). The same analysis notes that a number of major pharmaceutical companies have withdrawn from brain research in the past decade (Cressey, 2011[8]; Nutt and Goodwin, 2011[9]).

In 2014 in the United Kingdom charity spend on mental health research (GBP 25.1 million) was about 12% of the total spend on cancer (GBP 299.2 million), and less than half the spending on cardiovascular (GBP 85.2 million), neurological (GBP 63.4 million) or infection (GBP 78.4 million) research. Government spending on mental health research (GBP 42.8 million), however, was more closely matched with other areas of health research including cancer (GBP 45.7 million) (UK Clinical Research Collaboration, 2015[6]).

There are some exceptions, notably Norway. In Norway, a 2019 report reviewing research and development efforts in mental health found significant investment in research and development in psychiatry – NOK 1.4 billion in 2017, or 4% of total research investments in Norway and more than 15% of the NOK 9 billion spent on research and development for medicine and health sciences in 2017 (NIFU, 2019[10]). The same report found that in the period 2011-17 there was an overall increase in total research in Norway including in medicine and health, and that research on mental health has kept pace with this increase, both in terms of the number of scientific publications and in terms of resources. Nonetheless, research efforts did not necessarily match the distribution of the burden of mental ill-health in Norwegian society; for example, depression and anxiety had a lower share of resource input despite being a significant driver of ill-health in Norway.

Governments are leading the push for more mental health research

In recent years, there are signs that some countries are investing more significantly in mental health research, across a range of areas from basic science to service development or service delivery. Just under half of OECD countries (11 of 29 responses) reported that they have a significant national or regional research agenda, for example focused on mental health service improvement, pharmaceutical development, or biomedical research, for mental health (OECD, 2020[11]). Many of these national research agenda have been defined by government-defined multi-year research strategies, often backed by significant national funding, though the scope of the research agenda does differ.

Several OECD countries have developed, or are in the process of developing, national mental health research strategies. These countries include the United Kingdom (Department of Health, 2017[7]), Australia (Australian Government National Mental Health Commission, n.d.[12]), and the United States (The National Institute of Mental Health, 2015[13]). Denmark is currently working on a 10-year plan for mental health which will set the long-term direction for mental health treatment in Denmark, and which will also focus on research. Across these strategies, there are some significant similarities. Notably, the strategies point to the need for further basic research to accelerate understanding of the causes and potential treatment for mental disorders, but also the significant interaction with life course, socio-economic, and cultural factors, an emphasis also made in the findings of the EU Roamer project which set six European mental health research priorities (Wykes et al., 2015[14]).

These national strategies have approaches in common including stressing the importance of research focusing on prevention, recognising different risks and needs across the life course, and the particular vulnerability of some age groups, notably children and adolescents, research developing and development and linking of data, research into new technologies and telemedicine, and interaction between risk and experience of mental disorders and socio-economic and cultural factors. The United Kingdom’s strategy also notes some of the potential for studying the genetics of mental health problems, especially at a population level. The United Kingdom is one of more than 40 countries contributing to the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium at the UNC School of Medicine in North Caroline, the United States, which has already identified over 128 genetic risk factors for mental health problems (Department of Health, 2017[7]; Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2020[15]).

In other countries, for example Canada, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Norway or Poland, there is not necessarily a single national research strategy for mental health but there is nonetheless a significant and broad mental health research agenda, often being led by dedicated institutes or academic departments, or a national research programme with significant backing from the government, as in the Netherlands.

In Canada, there are widely recognised knowledge gaps related to mental health prior to COVID-19; however the underlying systematic challenges to measuring mental health, mental disorders and the impact of care became more obvious when trying to determine the impacts of the pandemic. Canada is working to address these gaps by exploring initiatives that better capture of the state of mental illness in Canada (including changes over time) using valid and practical measures, and better integrate data from multiple sources to effectively assess the impact of health services, investments, and policies on mental health outcomes. For example, a longitudinal survey across 2020 by Mental Health Research Canada has tracked how the COVID-19 crisis has been impacting the mental health of Canadians, aiming to generate data that helps policy help policy makers, governments and service delivery agents tailor programmes to the need of Canadians in this crisis (Mental Health Research Canada, 2020[16]; OECD, 2021[17]). The Canadian Institutes of Health Research – Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction (INMHA) covers biomedical and clinical brain health research, alongside health system and services research, and research on the social, psychosocial, cultural and environmental factors that affect the health of populations (OECD, 2020[11]; Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2020[18]).

In the Czech Republic the National Institute of Mental Health has a research programme which spans areas including brain science, public health and social psychiatry, and international collaboration, as well as epidemiological research, economic evaluation of services, development of interventions and mental health programmes, and studies on stigma and discrimination (National Institute of Mental Health, 2020[19]).

A number of OECD countries are backing their national mental health research agenda with new and significant funding. For example in the Netherlands, the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport has funded the Dutch Association of Mental Health and Addiction Care (GZZ Netherlands) mental health research including a long-term cohort study and a range of clinically applied research (ZonMw, 2020[20]). Funding totalled EUR 10 million across 2016-17, a further EUR 5 million in 2018, and EUR 35 million for the period 2019-25 (ZonMw, 2020[20]; ZonMw, 2020[21]) (Table 7.1).

Are OECD countries promoting innovative solutions to mental health challenges?

While research investment and pharmaceutical innovation may have been sluggish in recent decades, digital tools and technology-based approaches to supporting mental well-being, and managing and treating mental ill-health, have been booming. In many cases innovation is led by private actors, for example app developers or non-governmental organisations, and disseminated or validated by governments to a greater or lesser extent. The COVID-19 crisis, and its impact on population mental health, use of digital and online platforms, and disruptions to traditional service delivery models, has accelerated the use of technology in the mental health space.

The COVID-19 outbreak has rapidly accelerated the use of digital tools in the mental health space

Online cognitive behaviour therapy has shown comparable levels of efficacy with that of face-to-face treatment, but the uptake of telemedicine in mental health has been slow (Feijt et al., 2020[22]). The COVID-19 outbreak appears to have further accelerated both delivery of mental health services via telemedicine, and availability and use of internet- or app-based mental health tools (Moreno et al., 2020[23]). Multiple countries have lifted legislative or reimbursement limits on providing mental health services through telemedicine. In mid-2020 80% of high-income countries reported to the WHO that they had used telemedicine/teletherapy to replace in-person mental health consultations, or the use of helplines (WHO, 2020[24]).

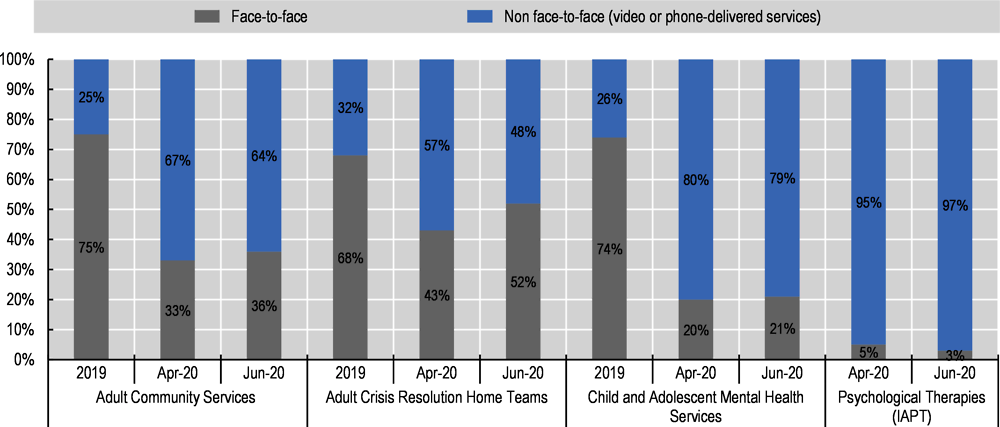

In Australia, the COVID-19 crisis rapidly accelerated the use of telemedicine, though these measures may be reviewed and service-delivery modes adapted as the COVID-19 crisis abates. As of end-April 2020, half (49.9%) of mental health services under the Medicare Benefits Schedule were being provided remotely; by the end of 2020 even as rates of face-to-face services increased again, the weekly rate of telehealth services was 76 000 in December and 60 000 in early January, compared to approximately 30 000 in late March 2020 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020[25]). In England (United Kingdom) mental health services moved significantly to non-face-to-face formats (phone and video) in 2020 (Figure 7.2); all mental health services had lower rates of face-to-face service delivery in April 2020 than the 2019 rate. Some services, for example Adult Crisis Resolution Home Team services, maintained at least some face-to-face services even during the peak of the ‘first wave’ of the outbreak in April 2020, and ratios of face-to-face: non-face-to-face started shifting back to levels more similar to 2019 patterns even from June. Other services, though – notably child and adolescent mental health services and psychological therapies (IAPT) – massively moved to non-face-to-face formats. In June 2020 only 3% of IAPT services were being delivered in-person in England.

Kaiser Permanente, the largest managed care organisation in the United States with 12 million plan members, was delivering 90% of its psychiatric care virtually as of 2020 (Gratzer et al., 2020[26]; Torous and Keshavan, 2020[27]). The Centre for Addition and Mental Health (CAMH), the largest psychiatric hospital in Canada, increased virtual care visits by 750% in March and April 2020 compared to the pre-pandemic period (Cisco Canada, 2020[28]). A study from the Netherlands showed an increase from less than half of practitioners using digital tools before the pandemic, resulting in the large majority using digital tools for therapy on a daily basis (Feijt et al., 2020[22]).

There are also signs that other mental health tools are being accessed more. In the United States, the online therapy company Talkspace saw an increase in clients of 65% between mid-February and end-April, a federal hotline for people in emotional distress say a 1 000% increase in April 2020 compared to April 2019, and use of self-screening questionnaires on the website of the non-profit Mental Health America increased 60-70% over the course of the outbreak (National Council for Behavioral Health, 2020[29]; Mental Health America, 2020[30]). The COVID-19 outbreak has also pushed governments to make more online or digital mental health resources available. In April 2020 the Canadian Government (Health Canada) launched the Wellness Together Canada (WTC) portal to provide short-term mental health and substance use supports and services to Canadians during COVID-19. Key objectives are to help address the anticipated increase in mental health and substance use service needs faced by Canadians, and to address disruptions to normal service delivery resulting from the pandemic (Government of Canada, 2020[31]). To date, the Government of Canada has invested CAN 68 million in the WTC portal, and will continue to fund the portal into 2021-22 with an additional CAN 62 million.

Countries are at different stages in taking advantage of the growing number of mental health apps and digital tools

Over the past decades, technological tools for remote psychological treatment have been developed, enhancing accessibility and flexibility of mental health care for people with mental health conditions, in particular for people living in rural areas. Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy has existed for more that 20 years (Andersson et al., 2019[32]). In recent years mobile technology has led to the development of multiple mobile phone apps to deliver effective mental health care, including many apps applicable for severe mental illness such as CBT2GO, PRIME, Intellicare, CBT-coach, T2 mood Tracker, PeerTech, Stop Breath and Think, mind LAMP, Mindfulness Coach and Virtual Hopebox are among many other apps for delivering mental health care for people with severe mental illness (Torous and Keshavan, 2020[27]; Firth and Torous, 2015[33]; Depp et al., 2019[34]). Indeed, in the last few years, there has indeed been considerable activity around finding innovative solutions to mental health challenges in recent years, much of which has been focused on better and broader deployment of digital tools including symptom tracking, self-help, and telemedicine. In particular there has been an explosion in apps developed by private companies, sometimes in partnership with governments or health service providers (Box 7.1).

There has been an explosion of apps and digital tools to promote mental well-being and manage mental health in OECD countries in recent years. The function of these apps ranges from tracking self-management of symptoms, for example Thrive or WorryTree for mood tracking, mindfulness apps such as Calm or Headspace, Beat Panic designed to help overcome panic attacks and anxiety or BlueIce to help young people manage their emotions (NHS, 2020[35]). Other apps, such as Ieso or Big White Wall in England (United Kingdom) or Talkspace in the United States connect people directly to licenced therapists, and in some cases access to these services are covered by employers or health insurance providers. Apps such as SAM Screener, for PTSD symptoms or MIRROR for screening for PTSD can be used as self-screening tools for mental health conditions.

A range of apps have been found to be effective in delivering mental health care. A meta-analysis covering 22 mobile apps to treat depression found positive impacts on alleviating symptoms and improving self-management, with the greatest benefits for persons with mild-to-moderate depression, while a meta-analysis of nine randomised control trials of mobile apps for anxiety contributed to improved symptoms, especially in combination with in-person or internet-based therapy (Firth et al., 2017[36]; Firth et al., 2017[37]). A systematic review of mobile apps for schizophrenia also showed positive impacts, with a high rate of app retention by users (92%) and regular daily use by users, and a range of clinical benefits (Firth and Torous, 2015[33]; Chandrashekar, 2018[38]).

In OECD countries, a range of non-government actors have established funds or platforms to boost innovation in the mental health space. The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in the United Kingdom announced a GBP 2 million fund as part of their mental health campaign Heads Together, focused on digital tools for mental health in 2017 to develop new digital tools to help people have conversations about mental health. The first tool coming out of this fund was ‘Shout’, a free crisis service for people who feel they need immediate support, staffed by trained volunteers, and available 24 hours a day (Heads Together, 2019[39]). The American Psychiatric Association also launched the Psychiatry Innovation Lab in 2020, aiming to nurture early-stage ideas and ventures by investing in them with mentorship, education, funding and collaboration opportunities within our community of mental health innovators (American Psychiatric Association, 2020[40]).

Integration of apps and digital tools – e-mental health – in broader health services is at different stages in different OECD countries, but at present appears to be ad-hoc or experimental rather than systematic. For instance in Ireland, the health service has been involved in developing an online cognitive behavioural therapy platform eWell (Health Service Executive Ireland, 2018[41]), and several Irish universities have contributed to the development mental health digital tools (for example Pesky gNATS (Pesky gNATs, 2021[42]), but the 2013 National eHealth Strategy did not make particular mention of mental health (Vlijter, 2020[43]). In Belgium, though there are some regional e-mental health initiatives and e-mental health is high on the national agenda and included in the 2019-21 eHealth Action Plan, no large-scale or national e-mental health projects are in place (Vlijter, 2020[43]). In France and Germany there is interest in e-mental health at different levels, for example a ‘health innovation hub’ to fast track innovative digital health care ideas in Germany and a e-mental health is included in a number of strategies in France – Mental Health and Psychiatry in 2018, and Accelerate the Digital Shift in 2019 (Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé, 2018[44]; Agence du Numèrique en Santé, 2019[45]) – but neither country systematically include e-mental health use in service delivery.

The Netherlands and England stand out as two countries where e-mental health has been adopted widely. The Netherlands had its first e-mental health provider in 1997, and the use of e-mental health has increased rapidly in recent years with most GPs and mental health providers now offering e-mental health tools, and e-mental health widely reimbursed by insurance companies (Vlijter, 2020[43]). In England, over 50% of GPs use e-mental health tools – primarily self-management tools – and the NHS apps library guides service users towards apps found to be effective, which they can often access without referral (Vlijter, 2020[43]; NHS, 2020[35]).

Interest in the use of artificial intelligence in the mental health field is growing

In the academic community, and in some business sectors, and in some countries, interest in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the mental health field is growing. A range of studies have found that machine learning methods can be applied to data gathered from online platforms, internet use, computer games, wearables such as smart watches, or specifically-designed apps, and that this data can be used to detect mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety or bipolar disorder (Garcia-Ceja et al., 2018[46]). In Australia, for example, the data and digital specialist unit of the Australian national science research agency CSIRO has developed a computer game and AI technology which, combined, is able to identify specific behavioural patterns linked to depression and bipolar disorder (CSIRO, 2019[47]; Dezfouli et al., 2019[48]). With further development, such technology could be used by or with mental health practitioners, and help improve diagnosis rates and accuracy of diagnoses of mental health conditioners.

Some discussion has been focused on whether analysis of patterns of internet or social media use can point to population-level mental health trends, identify persons at risk of mental ill-health or even suicide, or even direct at-risk persons towards appropriate support (Chancellor and De Choudhury, 2020[49]; Garcia-Ceja et al., 2018[46]). A 2020 study looked at Facebook messages and images of 223 participants, some of whom had schizophrenia spectrum disorders or mood disorders, and analysed content uploaded or shared in the 18 months before a hospitalisation event (Birnbaum et al., 2020[50]). This study found that using machine learning algorithms, different patterns of content shared could be distinguished between persons with a mental health condition, and healthy volunteers, using Facebook activity alone. Facebook itself has been looking to use machine learning technology applied to Facebook content to create a suicide and self-harm alert tool, using a pattern-recognition system to scan users posts and videos for key terminology (WIRED UK, 2017[51]; New Scientist, 2017[52]). The application of AI to identifying mental health risks or mental ill-health is not unique to Facebook; in the United States the Department of Veterans Affairs has applied AI technology to scanning medical records to identify suicide risks (The New York Times, 2020[53]), while a study at the KU Leuven University in Belgium found that a risk-screening algorithm could be a promising approach to identify students at the time of university entrance who may be at high risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Mortier et al., 2017[54]).

The use of AI in the mental health field may have promise, but it is not without challenges. The use of individuals’ data to identify or signal mental health risks raises important questions about privacy and consent for data usage (Business Insider France, 2019[55]; Barnett and Torous, 2019[56]).

In addition, it is not always clear how AI-led alert systems for example, can be integrated with appropriate services to support those identified as at-risk; such undertakings could also raise important questions about duty of care for persons identified as at risk – or who are not identified as at-risk – by such algorithms, including that of private companies (The New York Times, 2020[53]; Barnett and Torous, 2019[56]; The New York Times, 2018[57]).

Are care and services delivered in the most effective and efficient way, based on best available evidence?

It is extremely difficult to assess how ‘efficient’ and ‘evidence-based’ mental health systems are

All health care systems are seeking to deliver a maximum amount of effective care, with limited resources. In the mental health sector where resources are particularly tight (Chapter 6), maximising the impact of scarce resources is even more critical. However, assessing how ‘efficient’ mental health care systems are has been a long-standing challenge, limited by loose conceptualisation of efficiency in mental health systems (Lagomasino, Zatzick and Chambers, 2010[58]), heterogeneity in service design even within countries (Gutiérrez-Colosía et al., 2019[59]; Monzani et al., 2008[60]), and above all by a lack of relevant data (Moran and Jacobs, 2013[61]; García-Alonso et al., 2019[62]).

Nonetheless, promoting effective use of resources and reducing waste should remain a priority in mental health systems, and many of the key ways of improving efficiency in health care – such as reducing administrative costs, improving care co-ordination, and reducing emergency care visits (OECD, 2017[63]) – should also be considered in mental health care. In addition, some mental health services can represent opportunities for efficiency gains, for example greater investment in community-based services which can offer good value-for-money compared to inpatient services (see Box 7.2). Equally, investment in effective promotion and prevention (see Chapter 5) and integrated care (see Chapter 4) has potential to pay-off in terms of reducing mental health needs, responding to more mental health needs through lower-threshold care options, and reducing broad economic costs including disability, sickness absences, and lost productivity (OECD/European Union, 2018[64]).

Across OECD countries reform efforts have been moving mental health services, including services for severe and enduring mental health conditions, away from inpatient settings and towards community-based care delivery. That services ‘be developed close to the community’ is one of the key sub-principles in the principle ‘High Quality and Accessible Services’ in the OECD Mental Health System Performance Framework, as discussed in Chapter 3 of this report (OECD, 2019[1]). Community-based services for mental health care can also represent better-value-for money as compared to inpatient services (Knapp et al., 2010[65]; Winkler et al., 2018[66]). While most OECD countries see a key role for inpatient mental health services even in strongly community-orientated systems (Thornicroft and Tansella, 2002[67]; Thornicroft, Deb and Henderson, 2016[68]), prioritising investment in community-based services can represent good value-for-money.

The cost of care for an individual in a community setting, compared to an inpatient setting, can be significantly lower. In Australia in 2018-19, the average cost per acute mental health admitted patient day was AUD 1 328, compared to the average cost per community mental health treatment day of AUD 353 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021[69]). In Australia, there is a comparatively low rate of mental health beds and inpatient care and community-based services are well-developed, and Australia’s mental health spending has reflected the growing importance of community-based care services over the past three decades. In 1992-3 spending on psychiatric care in hospitals represented (AUD 82.01 per capita) more than twice the spending on community mental health services (AUD 29.93 per capita), but by 2018-19 spending on community services (AUD 97.2 per capita) was close to the same as spending on hospital services (AUD 112.42 per capita) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021[69]).

In countries where inpatient care still represents a significant proportion of mental health care, increasing investment in community-based services can represent a cost-effective way to shift care away from hospital settings, and/or increase the availability of mental health services. For example, in the Czech Republic, where the rate of psychiatric beds (0.93 per 1 000 population) is above the OECD average (0.68 per 1 000 population) and well above the bed rate in countries with a long history of community-based services such as Australia (0.42), Ireland (0.36), the United Kingdom (0.35) or Italy (0.09) (OECD, 2020[70]), a cost-effectiveness analysis of care of people with psychosis has found good economic evidence for deinstitutionalisation (Winkler et al., 2018[66]). In the Czech Republic, the total societal cost of discharge into community services was EUR 8 503, nearly twice the cost of no discharge and continued inpatient care which was EUR 16 425, while the annual QALY was 0.77 for patients receiving community care at baseline compared with 0.80 in patients in hospital at baseline.

To deliver good outcomes for people using mental health services, it is critical that mental health services are based on best available evidence, and are not shaped only by historical practices or determined by existing service infrastructure. ‘Evidence-based practice’ or ‘evidence-based medicine’ are “… the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” (Sackett et al., 1996[71]; Guyatt et al., 1992[72]) and have become the standard expectation for health care in OECD countries. When it comes to mental health care, uptake of evidence-based practices (EBPs) in mental health seemed to lag behind the rest of the health care sector. For example in the early 2000s, as EBPs increased throughout the health care sector in the United States, relatively few accounts of the implementation of EBPs were found in mental health care (Magnabosco, 2006[73]). Concerns have also been raised about how ‘evidence’ for mental health interventions is developed and whether this approach overlooks the importance of the skill and experience of the practitioner to adapt to the individual service users’ needs, and whether an EBP-approach overlooks interventions, for example in psychology, that may be less well-adapted to testing through randomised control trails (Psychiatric Times, 2008[74]; Tanenbaum, 2005[75]).

However, even when mental health services are available – and in most OECD countries 50% or more of the population have reported at least some unmet need for mental health care (see Chapter 3 of this report) – it is very difficult to assess the extent to which services are well-aligned with best available evidence. To ensure quality of care and deliver evidence-based practices, countries have increasingly developed clinical guidelines to stimulate the uptake of dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices. For example, the Netherlands has developed protocols to deliver evidence-based practices, and to strengthen compliance with these protocols and guidelines, care providers and health care insurances have agreed to only cover psychological practices in basic health insurance that are seen as evidence-based and effective (Kwaliteitsontwikkeling GGZ, 2017[76]). An international comparison of the use of evidence based clinical guidelines for eating disorders in Australia, New Zealand, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States shows that although clinical guidelines are increasingly disseminated amongst care providers and main treatment approaches have strong commonalities across countries, there still remains large differences amongst additional recommendations on evidence-based treatments (Hilbert, Hoek and Schmidt, 2017[77]). Even where tools to move services towards evidence-based practice are well in place, such as clinical guidelines being widely available, it is challenging to assess how well services adhere to guidelines or best available evidence (Nguyen et al., 2020[78]; Van Fenema et al., 2012[79]; Joosen et al., 2019[80]; Van Dijk et al., 2013[81]).

Do countries have strong mental health information systems?

With a few exceptions, countries are unable to comprehensively measure the dimensions of mental health performance that they defined as most important

The OECD Mental Health Performance Framework (OECD, 2019[1]) was defined by stakeholders from across OECD countries, including government policy makers, experts-by-experience, academic experts, and workforce representatives. This Framework defined the ultimate goals of a high-performing mental health system – that the system be person-centred, deliver accessible and high quality care, promote good mental health and prevent mental ill-health, be cross-sectoral and integrated, have good governance and leadership, and be future-focused and innovative. At this point, few if any countries are able to comprehensively measure performance at the national level across all of these high-priority areas of performance.

Tracking and comparing health system data across settings and services, across time, and across countries are powerful tools for understanding performance (OECD, 2019[82]; OECD, 2019[83]). Availability of mental health data, in countries and internationally, has long lagged behind broader health data development (Hewlett and Moran, 2014[84]). Over the past six years there has been a clear increase in availability, including at an international level, of mental health data. Since their introduction in 2013-15 country coverage of the OECD’s three indicators on mental health care quality has increased markedly: from 7 countries reporting excess mortality in 2013 to 12 in 2019; 14 countries reporting inpatient suicide in 2015 and 21 in 2019; and 10 countries reporting suicide after discharge in 2015, to 14 in 2019 (OECD, 2020[70]).

Responses to the OECD Mental Health Benchmarking Data Questionnaire were promising (Table 7.2). However, the majority of data that was available or broadly available to be reported to the OECD in 2020 covered inputs (beds, spending), or processes (length of stay, admissions, contacts with specialist care). For items which gave more insights into continuity of care, quality, or outcomes – such as repeat admissions, follow up after discharge, repeat emergency department visits – far fewer countries were able to report data. This means that even when appropriate quantitative indicators to measure performance for some of the performance subprinciples identified in the OECD Mental Health Performance Framework – continuity of care measured by follow-up, timeliness measured through waiting times for services, involvement of social protection systems or improvement of individual’s condition measured through employment status or unemployment claims for mental health conditions – few countries are able to report them. Under the Data Questionnaire all data were requested with deliberately broad definitions; for those items where there are sufficient countries reporting data, a further phase of review by the Secretariat is being undertaken to assess the similarity of the sources and methods for the items, and their potential for comparability.

There are a number of countries, including Australia, England, Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Norway, where extensive mental health data is available. In the Netherlands, mental health indicators include prevalence, service availability and contact rates as well as staff assessment of services, workforce flows, waiting times and absenteeism due to illness (Ministry of Health Netherlands, 2020[85]). In Norway, available indicators include experiences after a 24 hour inpatient stay, rate of individual care plans, involuntary admissions rates and waiting times (Directorate of Health, 2020[86]). Some countries – Australia, Canada and New Zealand – also stand out as countries where there has been notable mental health data innovation, including patient-reported, data to understand outcomes and recovery, tracking mental health outcomes across sectors, and data frameworks to understand mental health performance in a comprehensive way.

The New Zealand Mental Health and Addictions KPI Programme (KPI Programme) is a provider-led initiative, designed to bring about quality and performance improvement across the Mental Health and Addiction sector.

The KPI Framework was developed as a quality and performance improvement tool, to improve outcomes for people who use mental health and addiction services. The indicators are designed to be used as tools to promote greater understanding about the differences between services in different regions and to prompt discussion about the activities that lead to improved outcomes.

The specific goals of the KPI Programme are to implement the New Zealand KPI Benchmarking Framework into all district health boards (DHBs) and partnering non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to ensure sustainable benchmarking across the sector, in order to:

maintain and strengthen clinical ownership and responsibility for provider performance.

enable continued learning and innovation through the availability of comparative performance data and opportunities to actively challenge, question and share information between providers to achieve performance improvements.

develop NGO capacity and capability to contribute to performance improvement in the broader system of care as well as the NGO sector.

There are also requirements for DHBs to report against a range of performance measures. These are reviewed every year; however, they often include one or more mental health service-related measures.

Source: OECD (2020[11]), OECD Mental Health Benchmarking Data and Policy Questionnaires.

However, available mental health measures – especially at the international level – still do not map fully onto the domains of performance that matter to OECD countries. The OECD Mental Health Performance Benchmarking project began by asking mental health stakeholders from across OECD countries, ‘when it comes to mental health, what matters?’, and in answer to this question the OECD Mental Health System Performance Framework was developed. Having started by identifying the performance principles that should be measured, rather than what already could be measured using available data, the gaps in available indicators were made clear. For example, it was not possible at even a single-country level to identify measures that track the Framework Principles and Sub-Principles such as how effective the mental health system or services empower individuals to realise their own potential, or prioritise efficient and effective distribution of resources, or ensure that services are based on best available evidence.

Do countries have mental health workforce capacity for future generations?

There is significant variation in mental health workforce capacity, between and within countries

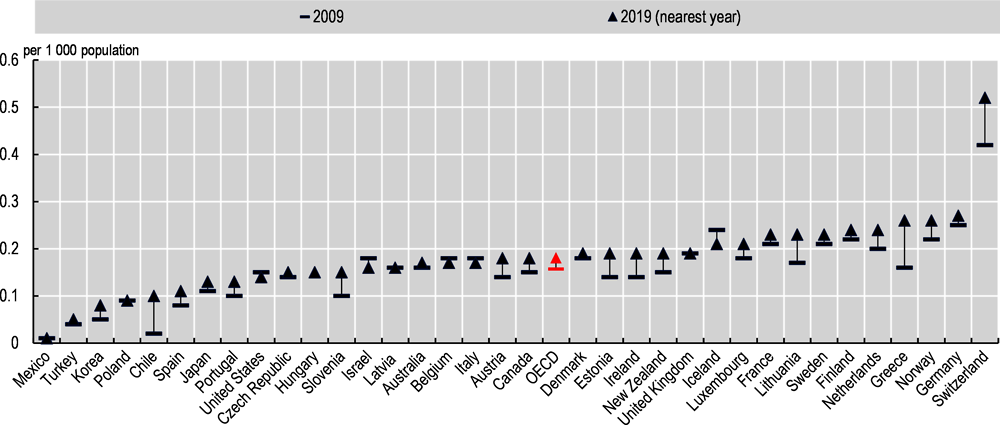

There is significant variation in the mental health workforce across OECD countries. For workforce categories for which data is most easily available, specifically psychiatrists, there is wide variation across countries. The number of psychiatrists per 1 000 population in 2019 ranged from 0.01 in Mexico, 0.05 in Turkey, 0.08 in Korea or 0.09 in Chile, to 0.25 or more in Greece, Norway and Germany, and 0.52 in Switzerland (OECD, 2020[70]), (Figure 7.3).

On average, the rate of psychiatrists increased between 2009 and 2019, from 0.16 per 1 000 population to 0.18; in some countries the increase was even more significant, more than 30% in Korea, Chile, Portugal, Estonia, Ireland, Lithuania and Greece. In a few countries – the Czech Republic, Iceland, Israel, the United States – the rate of psychiatrists fell. In Israel the overall number of doctors has fallen over recent decades, but in other countries falls in the rate of psychiatrists do not reflect overall workforce trends (OECD, 2019[82]; OECD, 2020[70]). In the United States, the overall number of physicians per 1 000 population increased from 2.44 in 2009 to 2.61 in 2018, with other categories of physician such as primary care physicians and neurologists also increasing, while the rate of psychiatrists fell by 7% (OECD, 2020[70]; Bishop et al., 2016[87]). Challenges around recruitment of medical students into psychiatry which contribute to overall shortages have also been reported in Australia (although the overall rate of psychiatrists increased by 5.6% between 2014 and 2018 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018[88]; Stampfer, 2011[89]), Canada (Lau et al., 2015[90]), and the United Kingdom (Goldacre et al., 2013[91]).

Within countries, psychiatrists (and other mental health specialists) are not necessarily well-distributed across the population. In 2013, analysis of the rate of physicians per population in the United States suggested that psychiatrists were particularly unequally geographically distributed (Bishop et al., 2016[87]). 2018 analysis found that rural countries had a significantly lower proportion of psychiatric residents in training, with likely long term workforce implications as psychiatrists are found to be likely to practice in the state they completed their residency (Beck et al., 2018[92]). In Australia, access to mental health care in rural and remote areas is a longstanding challenge, and workforce shortages in these areas contribute to the difficulties. In 2018 86.4% of psychiatrists in Australia were employed in major cities (where 72.0% of the population live), with 16.0 psychiatrists per 100 000 population in major cities, compared to 6.7 in remote areas and 3.1 in very remote areas (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018[88]). Though there was a higher rate of psychiatrists in major cities, the location of psychiatrists was more skewed towards less remote locations than all medical practitioners, for who there is almost double the workforce in major cities compared to remote areas.

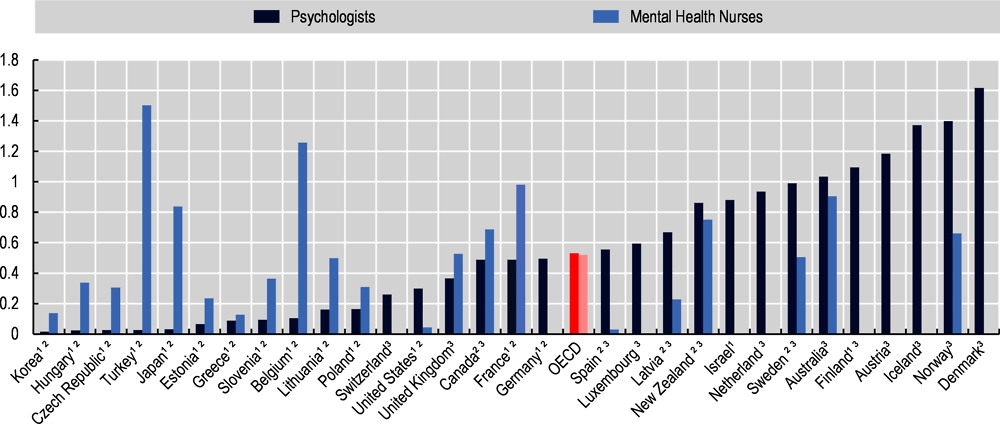

Other categories of mental health workforce play a critical role in delivering mental health services, including mental health nurses and psychologists, but also social workers, counsellors, General Practitioners or family doctors, occupational therapists, paramedics, and more. In many countries diverse teams of mental health professionals work together to deliver care. However, it is extremely difficult to collect workforce data for these diverse categories of mental health workforce; at the national level, this data is not routinely reported in all countries, and internationally there are significant comparability challenges. There are differences between countries in terms of how workforce data is reported (for example, full-time equivalent, all registered professionals, including or excluding private sector or non-hospital workers), as well as in terms of how mental health professionals are classified. For example, when it comes to psychologists there is significant variation in how psychologists are accredited, with some countries having single national accreditation systems for psychologists, and other countries having multiple accreditations or no nationally endorsed accreditation.

These comparability issues are a significant challenge for understanding the capacity and sustainability of the mental health workforce in OECD countries. However, given the diversity of different workforce categories involved in delivering mental health care, it is clear that reporting the rate of psychiatrists alone does not give a sufficiently good picture of the mental health workforce.

Keeping in mind the comparability challenges, a scan of available workforce data, drawn from national sources and the WHO 2017 Mental Health Atlas, suggests wide variations. Based on national sources, the number of psychologists per 1 000 population ranged from 0.095 in Estonia, to 1.4 in Norway and more than 1.6 in Denmark (Association of Estonian Psychologists, 2019[93]; Statistics Norway, 2020[94]; The Ministry of Health, 2017[95]).

Workforce projections show that action is needed to increase the numbers of mental health professionals

Mental health workforce shortages are reported in numerous OECD countries. However, due to weak workforce data and many countries not preparing workforce projections for the mental health sector, it is difficult to estimate the scale of the shortage, or the gap in workforce that would need to be filled. When workforce projections are prepared, they often focus on just a few categories of staff – notably psychiatrists, sometimes mental health nurses – and do not account for the diversity of workforce roles in mental health such as psychologists, social workers, occupational therapists, and General Practitioners.

Workforce projections take stock of the range of factors influencing workforce capacity in a sector, such as average age of the professionals, rate of training, recruitment of foreign workers, capacity for ongoing training or workforce retention rates. Making workforce projections means that steps can be taken to anticipate eventual workforce shortages. Given the time it takes to train and recruit new health professionals, workforce projections need to look at a multi-year or even multi-decade time horizon (Ono, Lafortune and Schoenstein, 2013[97]). Only 16 out of 29 countries that responded to the OECD Mental Health Performance Benchmarking Policy Questionnaire indicated that they prepare mental health workforce projections, or include mental health workforce in overall workforce projections (OECD, 2020[11]). In some countries, such as Canada, workforce planning is de-centralised responsibility, and workforce projections are not undertaken nationally but by professional associations.

Where countries have undertaken workforce projections for the mental health sector, they tend to highlight both existing and escalating workforce shortages. The Association of American Medical Colleges has identified an escalating shortage of psychiatrists, driven by factors including lower reimbursement rates for mental health providers, and the fact that more than 60% of psychiatrists are over the age of 55, one of the highest proportions of older physicians across all specialties (AAMC, 2018[98]). A 2016 report from the Australian Government Department of Health identified that workforce shortages for psychiatry are focused in the public sector, with acute psychiatry and adolescent psychiatry particular areas of concern (Department of Health, 2016[99]). The same report projects a future undersupply of 125 psychiatrists by 2030 based an anticipated 2% increase per year in Australia (Department of Health, 2016[99]); between 2014 and 2018 the mental health workforce trend was already towards an increase in Australia, with an increase in psychiatrists (+ 5.6%), mental health nurses (+ 4.0%) and psychologists (+ 5.5%) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018[88]).

Some workforce plans also target increases in the mental health workforce, and in some cases a diversification of staff roles in mental health. In England, ‘Stepping forward to 2020/21: the mental health workforce plan for England’ set the target of establishing a total of 21 000 new mental health workforce posts between 2017 and 2021 (Health Education England, 2017[100]). This same strategy also takes stock of a greater diversity of staff roles. For example, in England the 2020/21 workforce plan included establishing a significant number of new posts, including 11 000 ‘traditional’ posts such as nurses, occupational therapists or doctors, and 8 000 posts in diverse roles such as peer support workers, personal well-being practitioners, or call handlers (ibid).

Prioritising mental health workforce growth, new workforce categories and models

As this chapter has identified, there are significant variations in the availability of mental health workforce across OECD countries, and many countries are confronted with – or will be confronted with – workforce shortages in key professions. There is a clear need for countries to undertake their own workforce projections for the mental health system, and at the same time international understanding of mental health workforce levels and distribution would be greatly helped by more consistency in workforce data reporting, which is a real challenge currently.

At the same time, there are ways that workforce capacity in the mental health field could be increased alongside ‘traditional’ workforce categories such as psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, and psychologists. Some countries are looking to integrate a wider range of different workforce categories in their mental health workforce planning. In England’s ‘Stepping forward to 2020/21: the mental health workforce plan for England’ which set the target of increasing the mental health workforce, the strategy also takes stock of a greater diversity of staff roles. For example, in England the 2020/21 workforce plan included establishing a significant number of new posts, including 11 000 ‘traditional’ posts such as nurses, occupational therapists or doctors, and 8 000 posts in diverse roles such as peer support workers, personal well-being practitioners, or call handlers (Health Education England, 2017[100]). Many countries are also increasingly offering mental health training to key front line actors, such as police, emergency departments, and teachers, as well as for the general population; while such training does not replace specialised mental health care, it can provide crucial low-threshold support to people experiencing mental distress, or in need of directing towards appropriate services (see also Chapter 4).

Some OECD countries are actively promoting the involvement of mental health service users, or former service users, in the delivery of mental health services. In England, the mental health strategy “No Health Without Mental Health” called for staff with experience and expertise to deliver individualised mental health care in resource-limited settings (Department of Health and Social Care, 2011[101]). Since then, England has been actively pursuing research into more extensive use of peer workers (people with personal experience of mental health issues) within the mental health system following evidence that peer support can bring benefits such as enhanced feeling of empowerment, better social support and increased personal recovery (Gillard, Edwards, Gibson, Owen, & Wright, 2013). In both Ireland and Australia evaluations of the impact on Peer Support Worker (in Ireland), and peer workers (in Australia) users found overwhelmingly positive feedback from mental health service users (see also Chapter 2). In Australia, peer support workers also reported that their work had positive impacts on their own mental health (Health Workforce Australia, 2014).

Digital apps and tools offer the possibility of massively increasing access to mental health support, but need to be integrated into the mental health system

The COVID-19 crisis has rapidly accelerated the use of digital mental health care, most notably telemedicine-delivered services, openly accessible phone and online support services, and app-based or online tools for self-screening, self-management, or treatment, and blended treatment integrating self-help and practitioner-led therapies. These services have the potential to respond to some of the significant unmet need for mental health care, have scope to support better outcomes, and in the case of app-based technologies could help massively scale-up access at a relatively low cost (Moreno et al., 2020[23]; Naslund et al., 2017[102]). Preliminary results have also shown that clinicians and clients have been positive about the uptake of digital services for the delivery of mental health during COVID-19, with service users reporting high levels of satisfaction with video-delivered services, good levels of adherence to treatment and some practitioners reporting more frequent check ins with clients (Torous et al., 2020[103]; Feijt et al., 2020[22]; Ramaswamy et al., 2020[104]).

Sustaining the positive growth of digital tools in mental health care will require efforts to integrate digital tools and technologies into the broader mental health system. Increasing access to telemedicine services for mental health has, for example, demanded changes to privacy regulations around use of online technologies, or reimbursement schedules. For example, the United States made changes around telehealth with federal regulations temporarily permitting unprecedented access across state lines and non-secure platforms (Gratzer et al., 2020[26]).

When it comes to the use of more diverse digital tools such as apps developed by private companies, the issues of ensuring integration with the mental health system, maintaining user privacy, and assuring quality are key issues. For example adherence to digital tools for health tracking is supported by support from an in-person practitioner (Moreno et al., 2020[23]; Simblett et al., 2018[105]), but privacy concerns or legislative structures can limit practitioners’ access to the self-monitoring data generated by the app user.

The European-level ‘eMEN’ project looks at how digital health solutions and specifically e-mental health can be used to improve quality and access to mental health services, and scaling-up safe and effective implementation of e-mental health technologies in European Union member states. Currently, eMEN is running e-mental health pilots in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, the United Kingdom, France and Ireland, and the challenge of health system integration is a recurring theme (eMEN, 2020[106]).

There are also ways that countries can take a more proactive role in quality checks for freely available mental health support tools. In England, NICE has been assessing digital therapies to be accepted under the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Programme (IAPT) (NICE, 2020[107]), while England’s NHS apps library guides service users towards apps found to be effective, which they can often access without referral (Vlijter, 2020[43]; NHS, 2020[35]). In Australia, too, the government has developed a digital mental health gateway which aims to guide people towards trusted information and digital tools (Box 7.4).

Head to Health is the Australian Government’s digital mental health gateway and lists quality digital mental health resources delivered by trusted Australian service providers. Head to Health aims to help people more easily access information, advice and free or low cost mental health services and supports, that most suit their needs. Currently, as part of a quality assurance mechanism, only digital resources funded by the Commonwealth or state/territory governments are listed on Head to Health.

In early 2018, an internal assessment was undertaken to evaluate the implementation of Head to Health post launch. This assessment has informed future considerations around ongoing operations of the site, and has also been of value in informing the development of new IT-enabled products the Department of Health (the Department) has undertaken. It also provided a comparison against the predecessor to Head to Health, mindhealthconnect.

While funding has not been available to support an independent review of the effectiveness and performance of Head to Health, the Department routinely collects data and analytics on how the site is performing and resonating with end users, including through a monthly Digital Activity Report. Visits to the site increased significantly as the COVID pandemic emerged. Current statistics (from launch in October 2017 to March 2021) indicate:

a low bounce rate of 25.47% (a bounce is where a user views only one page and then leaves the site);

A total of 247 166 conversions including search completions, decision support tool completions (Sam the Chatbot), email resources, and print resources requests;

An average of 6 500+ outbound referrals per month to the resources listed on Head to Health.

The Department conducted a general survey of Head to Health users in the second half of 2019. This survey aimed to measure people’s satisfaction with Head to Health, gather feedback to inform future enhancements and improve the user experience. Responses to the survey indicated that the:

Majority of users (62%) found it easy or very easy to find what they were looking for on Head to Health;

Majority of users (88%) trust the information and resources on Head to Health a moderate amount, a lot, or a great deal;

Majority of users (81%) find the resources on Head to Health somewhat relevant, relevant or extremely relevant;

Majority of users (88%) rate their experience on Head to Health as okay, good or great;

Majority of users (81%) are likely to recommend Head to Health to someone else.

Source: Department of Health (2021[108]), Head to Health, https://headtohealth.gov.au/, accessed 15 May 2021.

Evidence shows that a significant number of mental health treatments are efficient and effective, and should be prioritised in mental health systems

While it is extremely difficult to assess the overall efficiency and effectiveness of mental health systems, there is both good and growing evidence of which mental health interventions are effective and efficient, and countries have been taking steps to ensure that these interventions are prioritised. The evidence-base for effective mental health services is significant even if significant scope for further research remains (see Chapter 3 of this report, as well as the WHO guidelines on mental health and substance abuse (WHO, 2020[109]), and the forthcoming WHO menu of mental health ‘best buys’ (WHO, 2019[110])).

Clinical guidelines are one way that evidence-based practices can be disseminated and widely used in OECD in countries. Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and management of mental health conditions were used in 21 OECD countries in 2012, and since then the availability of clinical guidelines for mental health conditions – covering more conditions, covering more specific patient groups – has grown (Hewlett and Moran, 2014[84]). For example, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom now has at least one set of clinical guidance – often accompanied by a care pathway, quality standard, or less formal ‘NICE advice’ – across 15 broad categories of mental health and behavioural conditions (NICE, 2020[111]).

Some countries are also taking steps to ensure that investments in mental health are directed towards evidence-based services, and that mental health system reforms make evidence-based services a priority. In the Czech Republic, a mental health system reform that began in 2013 which included the aim of supporting evidence-based mental health care development. Together with the WHO, the Czech Government has assessed the quality of care in Czech psychiatric hospitals to improve care, and developed a system for evidence-based decision making and monitoring of the quality and performance of the Czech mental health care system. The system to support evidence based mental health care development in the Czech Republic consists of both macro and micro level indicators: macro level indicators look at mental health care structure and performance (such as structure of care, or mortality), and micro-level indicators are based on outcome measurement in psychiatry with the Global Assessment of Functioning, Health of the Nation Outcome Scale, and Assessment of Quality of Life in order to evaluate existing services as well as new innovative programs. As part of this ongoing reform work, a comparison of cost-effectiveness of different types of care for people with chronic psychotic disorders, comparing discharged into community services, with inpatient psychiatric care for at least three months, was undertaken (Winkler et al., 2018[66]). This study found that discharge into community services for people with psychosis represented similar outcomes in terms of Quality Adjusted Life Years (QUALYs), but that the costs of discharge to the community were around half the cost of ongoing inpatient care, and underscored how discharge to community care is cost-effective compared with care in psychiatric hospitals in the Czech Republic.

Further data development is needed to make international mental health benchmarking more effective

In some areas of mental health system performance, with the input of experts participating in the Virtual Workshops on Mental Health Performance Benchmarking held in September 2020, indicators which would be important tools for understanding performance but are not yet available across multiple countries were identified. In particular, more robust indicators are needed on: on well-being, positive mental health and social cohesion; prevalence of mental ill-health, unmet need for care, and health care coverage; on mental health workforce and diverse care providers, and workforce training; on research; on integrated care including integration with somatic care, and physical health outcomes; and on disparities within national population groups. The COVID-19 context, in which significant amounts of mental health care were moved to non-face-to-face formats, also highlighted the importance of indicators on changing care delivery methods, for example the rate of services delivered through telemedicine formats, preferably broken down by format (e.g. video, phone, app-based or chat-based).

Recognising some of these gaps, several indicators where data is not yet available across multiple countries, but where there is a critical importance for understanding mental health performance, were included in the Mental Health System Performance Benchmark. Specifically, these are: patient-reported outcomes (PROMs), population attitudes towards mental health for example mental health literacy or levels of stigma, and use of telemedicine in mental health care. These are areas where further development of internationally comparable indicators is warranted,

Additionally, there is clear scope to continue to focus on strengthening the availability of internationally measures of mental health system quality and outcomes. Across the indicators included in the data collection for this report (OECD, 2020[11]), it was by far measures of ‘inputs’ – service contacts, admissions – that were the most consistently reported across countries, while expert stakeholders engaged with the project consistently stressed the importance of focusing on quality and outcomes as priorities for understanding performance.

There are some newly collected indicators – follow-up after discharge, repeat readmissions to inpatient care, repeat emergency department contact for mental health reasons – that bring more insights into care quality and processes, and which several countries were able to report (Chapter 3). Other indicators which could have been promising, for example on restrictive practices (seclusion and restraint), or involuntary admissions, showed significant variation across countries in terms of definition and practice guidelines, and do not currently appear adept for routine international comparisons.

More measures of quality and outcomes are warranted, even as important gaps in ‘input’ measures remain

In some areas of mental health system performance, with the input of experts participating in the Virtual Workshops on Mental Health Performance Benchmarking held in September 2020, indicators which would be important tools for understanding performance but are not yet available across multiple countries were identified. In particular, more robust indicators are needed on: on well-being, positive mental health and social cohesion; prevalence of mental ill-health, unmet need for care, and health care coverage; on mental health workforce and diverse care providers, and workforce training; on research; on integrated care including integration with somatic care, and physical health outcomes; and on disparities within national population groups. The COVID-19 context, in which significant amounts of mental health care were moved to non face-to-face formats, also highlighted the importance of indicators on changing care delivery methods, for example the rate of services delivered through telemedicine formats, preferably broken down by format (e.g. video, phone, app-based or chat-based).

Recognising some of these gaps, several indicators where data is not yet available across multiple countries, but where there is a critical importance for understanding mental health performance, were included in the Mental Health System Performance Benchmark (OECD, 2020[11]) (see ‘Key Findings’ chapter in this report). Specifically, as a minimum these are: patient-reported outcomes (PROMs), population attitudes towards mental health for example mental health literacy or levels of stigma, and use of telemedicine in mental health care. These are areas where further development of internationally comparable indicators is warranted.

Additionally, there is clear scope to continue to focus on strengthening the availability of internationally measures of mental health system quality and outcomes. Across the indicators included in the data collection for this project (OECD, 2020[11]), it was by far measures of ‘inputs’ – service contacts, admissions – that were the most consistently reported across countries, while expert stakeholders engaged with the project consistently stressed the importance of focusing on quality and outcomes as priorities for understanding performance.

There are some newly collected indicators – follow-up after discharge, repeat readmissions to inpatient care, repeat emergency department contact for mental health reasons – that bring more insights into care quality and processes, and which several countries were able to report. It is suggested that these indicators are further discussed in the context of the HCQO Expert Group, and considered for more routine collection. Other indicators which could have been promising, for example on restrictive practices (seclusion and restraint), or involuntary admissions, showed significant variation across countries in terms of definition and practice guidelines, and do not currently appear adept for routine international comparisons.

Patient-reported measures should be at the centre of policy making and service-monitoring

The continuing gaps in availability of meaningful indicators of the dimensions of mental health performance that matter, as identified in the OECD Mental Health Performance Framework, underscore the importance of developing new measures. In particular, there is clearly space for more internationally comparable reporting on mental health service users’ experiences (PREMs) and outcomes (PROMs). At present, systematic patient reporting in mental health is in its infancy. As of 2018, a survey from the OECD showed that only five of the 12 countries surveyed (Australia, Israel, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom) reported PROMs and PREMs collection on a regular basis in mental health settings. Only Australia, the Netherlands and England reported that they collected and routinely reported both. Furthermore, patient-reported data in mental health covers a wide and diverse range of conditions, settings, interventions and patient populations.

Since May 2018, the OECD has been working with patients, clinicians and policy makers in a Working Group to develop mental health PREM and PROM data collection that enable international comparisons with 17 countries involved. The main objective is to develop PREM and PROM data collection standards in mental health for international benchmarking of patient-reported outcomes. Three domains which have international coherence have been identified for PREMs (respect and dignity, communication and relationship with health care team and shared decision making), and PROMs (relief of symptom burden, restoring well-being/social function and recovery support). The Working Group is looking towards a pilot PROM data collection, beginning with hospital care, focused on the domain of well-being, drawing on the OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being and the WHO-5 Well-Being Index questionnaire that measures current mental well-being (time-frame of the previous two weeks). For a pilot PREM data collection, again beginning with hospital care, the items already collected through the OECD’s HCQO’s regular PREM data collection is underway, with an additional item on courtesy and respect adapted from the Commonwealth Fund Questionnaire. It is expected that some pilot data will be available to be reported in Health at a Glance 2021.

References

[98] AAMC (2018), “Addressing the escalating psychiatrist shortage”, AAMC, https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/addressing-escalating-psychiatrist-shortage (accessed on 13 January 2021).

[45] Agence du Numèrique en Santé (2019), Feuille de route - Accélérer le virage numérique en santé, Agence du Numèrique en Santé, Paris, https://esante.gouv.fr/virage-numerique/feuille-de-route (accessed on 9 February 2021).

[40] American Psychiatric Association (2020), Psychiatry Innovation Lab, https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/education/mental-health-innovation-zone/psychiatry-innovation-lab (accessed on 6 May 2020).

[32] Andersson, G. et al. (2019), “Internet‐delivered psychological treatments: from innovation to implementation”, World Psychiatry, Vol. 18/1, pp. 20-28, https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20610.

[93] Association of Estonian Psychologists (2019), Eesti Psühholoogide Liit, http://www.epl.org.ee/wb/ (accessed on 10 May 2020).

[12] Australian Government National Mental Health Commission (n.d.), National Mental Health Research Strategy, 2019, https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/Mental-health-Reform/National-Mental-Health-Research-Strategy (accessed on 24 April 2020).

[69] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021), Mental health services in Australia - Key Performance Indicators for Australian Public Mental Health Services, AIHW, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/mental-health-indicators/key-performance-indicators-for-australian-public-mental-health-services (accessed on 10 February 2021).

[25] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2020), Mental health services in Australia - Mental health impact of COVID-19, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/mental-health-impact-of-covid-19 (accessed on 11 February 2021).

[88] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2018), Mental health services in Australia- Mental health workforce, AIHW, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/mental-health-workforce (accessed on 20 January 2021).

[56] Barnett, I. and J. Torous (2019), Ethics, transparency, and public health at the intersection of innovation and Facebook’s suicide prevention efforts, American College of Physicians, https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0366.

[92] Beck, A. et al. (2018), Estimating the Distribution of the U.S. Psychiatric Subspecialist Wor kforce Project Team.

[50] Birnbaum, M. et al. (2020), “Identifying signals associated with psychiatric illness utilizing language and images posted to Facebook”, npj Schizophrenia, Vol. 6/1, pp. 1-10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-020-00125-0.

[87] Bishop, T. et al. (2016), “Population Of US Practicing Psychiatrists Declined, 2003–13, Which May Help Explain Poor Access To Mental Health Care”, Health Affairs, Vol. 35/7, pp. 1271-1277, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1643.

[55] Business Insider France (2019), Inside Facebook’s suicide algorithm: Here’s how the company uses artificial intelligence to predict your mental state from your posts, Business Insider France, https://www.businessinsider.fr/us/facebook-is-using-ai-to-try-to-predict-if-youre-suicidal-2018-12 (accessed on 10 February 2021).

[18] Canadian Institutes of Health Research (2020), Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction Strategic research priorities, https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/27108.html (accessed on 24 April 2020).

[49] Chancellor, S. and M. De Choudhury (2020), Methods in predictive techniques for mental health status on social media: a critical review, Nature Research, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-0233-7.

[38] Chandrashekar, P. (2018), “Do mental health mobile apps work: evidence and recommendations for designing high-efficacy mental health mobile apps”, mHealth, Vol. 4, pp. 6-6, https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2018.03.02.

[5] Christensen, H. et al. (2011), “Funding for mental health research: the gap remains”, Medical Journal of Australia, Vol. 195/11-12, pp. 681-684, https://doi.org/10.5694/mja10.11415.

[28] Cisco Canada (2020), CAMH enhances virtual capacity to respond to demand for mental health services, https://newsroom.cisco.com/press-release-content?articleId=2072576 (accessed on 22 February 2021).

[8] Cressey, D. (2011), “Psychopharmacology in crisis”, Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/news.2011.367.

[47] CSIRO (2019), Computer game to assist clinicians in diagnosing mental health disorders, CSIRO.au, https://www.csiro.au/en/News/News-releases/2019/Computer-game-mental-health (accessed on 11 February 2021).

[108] Department of Health (2021), Head to Health, https://headtohealth.gov.au/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

[7] Department of Health (2017), A Framework for mental health research, Department of Health, London.

[99] Department of Health (2016), Australia’s Future Health Workforce - Psychiatry, https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/597F2D320AF16FDBCA257F7C0080667F/$File/AFHW%20Psychiatry%20Report.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2021).

[101] Department of Health and Social Care (2011), No Health Without Mental Health: a cross-government outcomes strategy, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/no-health-without-mental-health-a-cross-government-outcomes-strategy (accessed on 25 October 2019).

[34] Depp, C. et al. (2019), “Single-session mobile-augmented intervention in serious mental illness: A three-arm randomized controlled trial”, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Vol. 45/4, pp. 752-762, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby135.

[48] Dezfouli, A. et al. (2019), Disentangled behavioral representations, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, https://doi.org/10.1101/658252.

[86] Directorate of Health (2020), Mental health for adults - indicators, https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/statistikk/kvalitetsindikatorer/psykisk-helse-for-voksne (accessed on 6 May 2020).

[106] eMEN (2020), eMEN: Main achievements and Reflections 2016-2020, https://keep.eu/projects/18190/e-mental-health-innovation--EN/ (accessed on 9 February 2021).

[22] Feijt, M. et al. (2020), “Mental Health Care Goes Online: Practitioners’ Experiences of Providing Mental Health Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic”, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, Vol. 23/12, https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0370.

[33] Firth, J. and J. Torous (2015), “Smartphone apps for schizophrenia: A systematic review”, JMIR mHealth and uHealth, Vol. 3/4, p. e102, https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.4930.

[36] Firth, J. et al. (2017), “Can smartphone mental health interventions reduce symptoms of anxiety? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials”, Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 218, pp. 15-22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.046.

[37] Firth, J. et al. (2017), “The efficacy of smartphone-based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials”, World Psychiatry, Vol. 16/3, pp. 287-298, https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20472.

[62] García-Alonso, C. et al. (2019), “Relative Technical Efficiency Assessment of Mental Health Services: A Systematic Review”, Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, Vol. 46/4, pp. 429-444, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00921-6.