Chapter 4. Rethinking donor support for statistical capacity building1

Investing in data brings returns. Development data are critical for policy making, planning, and monitoring and measuring impact nationally and globally. Yet statistical systems in developing countries are often under-resourced and under-staffed and traditional support to statistical capacity building is not fit for purpose. While political support to have and use more and better data is essential to realising the full potential of data for development, donor support needs to be increased, more effective and better co-ordinated by creating, for example, compacts for a country-led development data revolution. The chapter shows how support for building statistical capacity can be revitalised for greater impact over the long term and calls for a more comprehensive and transparent system for measuring international support to statistics. It also stresses the importance of country leadership, co-operation among providers of development co-operation for data and statistics, data literacy, and innovation. Finally, the chapter sets out priority steps in rethinking donor support for statistical capacity building.

Key facts

Investing in data brings returns, for example:

-

Farmers’ share of crop export prices in Ethiopia doubled to 70% within four years of opening the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange, which provides real-time, official price data; its dissemination mechanisms are tailored to the needs of small farmers (Vaitla et al., 2017).

-

In the United Kingdom, a study has shown that every pound (GBP) invested in producing statistics on schools’ performance leads to academic improvements equivalent to a GBP 16 increase in gross domestic product (Burgess et al., 2013).

-

Censuses conducted in Mexico and Peru in 2000 showed that the proportion of births attended by health professionals among indigenous women was lower than among non-indigenous women (38% and 45%, respectively). These data were used to promote more effective interventions; by 2012, in both countries more than 80% of births by indigenous women were attended by health personnel (UN, 2015a).

Despite the evidence, however:

-

In 2015, the share of official development assistance (ODA) dedicated to improving data for development was only 0.30% (USD 541 million) (PARIS21, 2017).

-

A large share of global support to data for development continues to come from a very small number of providers: in 2015, five providers of development co-operation (the World Bank, Canada, the United Nations Population Fund, the European Commission/EUROSTAT and the African Development Bank) accounted for 75% of official development assistance for statistics (PARIS21, 2017).

-

In 2015, USD 181 million was committed as bilateral aid for statistics. This aid accounted for one-third of total commitments to statistics. The top five bilateral providers by size of contribution are: Canada, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Korea and Australia, accounting for 78% of bilateral aid.

-

Support to statistical capacity building has been supply driven and piecemeal, with little emphasis placed on partner countries' demand for data. There is greater emphasis on the data needed by development co-operation providers for their monitoring, reporting and accountability.

Development data give insights that are critical for policy making, planning, and monitoring and measuring impact nationally and globally. The demand for more and better data has increased in recent years as UN member states step up efforts to deliver and measure the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Development data inform country strategies to attain these goals (UNJIU, 2016); at the same time, they are integral components of Agenda 2030 itself (SDGs 17.18 and 17.19).2 To build high-functioning statistical systems capable of meeting the demands of the SDGs, it is essential to increase political and financial support from the international community (see the “In my view” piece by Sarah Hendriks). Despite the recognised contribution of development data to better outcomes,3 the current levels of official development assistance (ODA) remain well below what is needed.

Statistical systems in developing countries are ofte81n under-staffed and under-resourced (see Chapter 3; UNJIU, 2016; UNECE 2016). Trends suggest that the share of ODA for data and statistics has stagnated in recent years. Many developing countries – especially the least developed countries, small island developing states and states in fragile situations – depend largely on international support to build statistical capacity. If the data revolution is to create a world of greater prosperity and sustainable development, increased and smarter investments by providers of development co-operation are needed. Effective international support can help change a vicious cycle of under-performance and inadequate resources in statistics to a virtuous one in which increased demand and improved quality lead to higher use and greater value. Better data can also help respond to the greater accountability expectation of citizens in both developed and developing countries.

Traditional support for development data has largely focused on technical assistance. Characterised by low levels of co-ordination among providers, this type of support has targeted specific sectors rather than whole-of-government approaches and has lacked country ownership; as a whole, these efforts have not yielded substantial increases in statistical capacity. In the context of the data revolution, providers must reshape their approach to statistical capacity development to promote country ownership, align support with country priorities, focus on data use and users, foster diverse public-private partnerships, utilise new funding mechanisms, and emphasise results-based support.

This chapter proposes several avenues for directing additional resources to improve statistical capacity building and in doing so, deliver on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015c).

New resources need to be raised to build statistical capacity

Developing statistical systems is a long-term process, and the results will live long beyond the SDGs. Building the statistical capacity to guide, monitor and track national development progress towards the SDGs must begin now and be reliably funded until 2030 and beyond. Calculating an aggregate cost for developing countries of building this statistical capacity is complex and a work in progress. Two recent studies (SDSN, 2015; GPSDD, 2016) have calculated the minimum cost of producing data for the SDGs in 144 developing countries to be about USD 2.8-3.0 billion per year up to 2030. The estimates include the cost of expanding the programme of surveys and censuses and of improving administrative data systems.

Sarah Hendriks, Director of Gender Equality, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Nowhere in the world are males and females truly equal. Women learn less, earn less, have fewer rights and have less control over their assets. In 155 countries there is at least one law impeding women’s economic opportunities. Women own less than 20% of the world’s land despite producing the majority of its food. They represent 1.1 billion of the world’s unbanked population and the World Economic Forum estimates that it will take 170 years to achieve economic gender equality. Harmful practices and policies around the world are grounded in the view that women and girls don’t count. Even where good laws exist, implementation often falters.

Underpinning these gaps, one challenge is particularly acute for women and girls: data.

There are many data blind spots in global development. Even the most basic information on women and girls is often lacking: when they are born, how many hours they work, if and what they get paid, whether they’ve experienced violence, how they die. In too many areas, disaggregated data don’t exist at all, or data collection is “sexist”, leaving women and girls out or undercounting them. This perpetuates the undervaluation of women and girls in society, and leaves their huge potential untapped.

The problem is exacerbated by gaps in political will, funding and capacity. Only 13% of countries dedicate a budget to gender statistics and many lack the national strategies and training needed to ensure robust gender data collection. Data collection is often fragmented or conducted using outdated methods. Even when policies and programmes targeting women and girls are funded, they are often poorly evaluated. Consequently, policy makers don’t learn about what is working and what isn’t, making ill-informed decisions, trade-offs and resource allocations. Civil society groups are also ill-equipped to conduct data-driven advocacy.

In my view, closing the gender gap requires closing the data gap. Our foundation is investing USD 80 million in improving gender data, evidence and accountability. Critically, these resources will improve the way data and evidence are used to drive advocacy and inform policy.

Specifically, two new areas of partnership include:

-

Support for UN Women’s flagship programme initiatives on gender data, which aim to improve the production, availability, accessibility, and use of quality gender data and statistics (www.unwomen.org/en/how-we-work/flagship-programmes).

-

The Initiative for What Works, which will build a network of in-country hubs to improve evidence on programmes and policies targeting women’s economic empowerment and healthy adolescent transitions.

We call on donors and governments that care about advancing progress for women and girls to join us, prioritising and increasing investments in gender data and evidence. The needs are many – from filling data gaps; to strengthening national capacity; to gathering and tracking evidence in more timely, consistent ways; to reducing bias by harmonising approaches for data collection; to supporting access by women’s organisations to data, as well as their capacity to advocate with it.

Better data are foundational to everything else we hope to achieve. Women and girls count, and they are counting on us to step up in the years ahead.

“The state of development data funding” report (GPSDD, 2016) estimated that developing countries face an annual funding gap, once domestic budgets for statistics are accounted for, of about USD 635-685 million to produce data for the SDGs up to 2030. To fill this gap countries would need to raise external sources of financing, notably from development co-operation. Assuming that aid to statistics, which reached USD 541 million in 2015, helps produce data for the SDGs in developing countries and thus helps fill this funding gap, an additional USD 200 million per year up to 2030 is needed to respond to the minimum financing needs.

Trends in aid for statistics

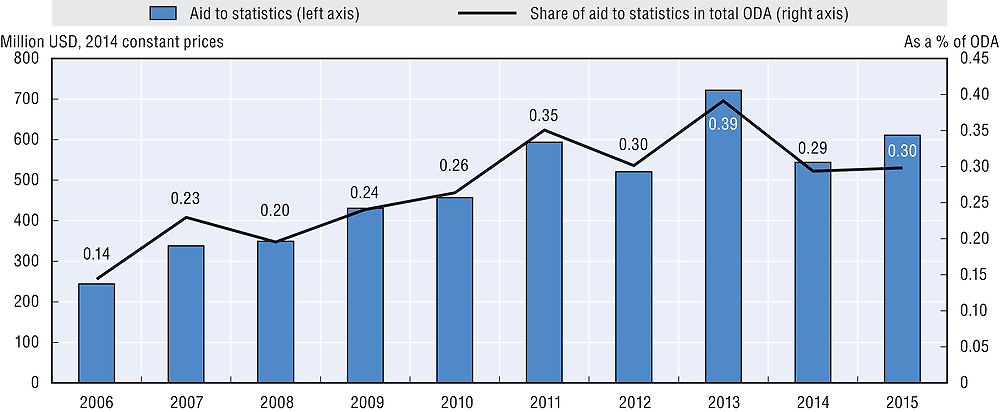

In the early 2000s, there was a clear commitment from the international development community to improve data in support of the Millennium Development Goals. This commitment was matched by a steady increase in funding between 2005 and 2013. The latest trends in aid for statistics demonstrate that international calls to improve development data are not translating into a corresponding increase in predictable financing to produce data for the SDGs. According to the 2017 PARIS21 “Partner report on support to statistics”4 – aid to statistics was USD 541 million in 2015 – this represents an increase of 12% (in real terms) compared to 2014 (PARIS21, 2017). However, at 0.30% of total ODA in 2015, aid for statistics remains a relatively low development co-operation priority for most donors. In 2015, bilateral aid for statistics (USD 181 million) was the equivalent of one-third of total support and five bilateral providers (Canada, Sweden, United Kingdom, Korea and Australia) accounted for 78% of this. Trends also show how financing fluctuates from year to year, undermining predictability for partners (Figure 4.1).

Source: PARIS21 (2017), “Partner report on support to statistics”, www.paris21.org/press2017.

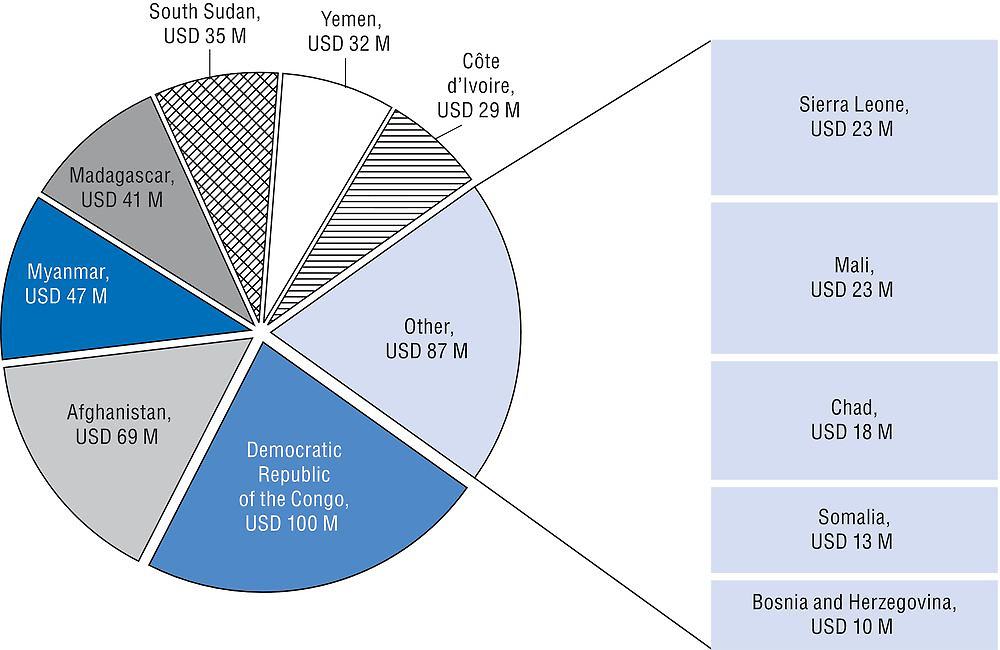

More detailed analysis of aid financing for statistics reveals interesting funding trends. For example, a large share of total ODA comes from a very small number of providers: five bilateral and multilateral providers accounted for 75% of total aid commitments to statistics in 2015 (PARIS21, 2017).5 Between 2013-15, the countries with the lowest statistical capacity received the most support from members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC). The 2017 PRESS report found that when aid commitments were matched with the World Bank’s Statistical Capacity Indicator (World Bank, 2017), low-capacity countries received on average more funding per capita (USD 0.87) than countries with high capacity (USD 0.36) (PARIS21, 2017). It is also promising to note that states with fragile situations receive considerably more support from the statistical development community: reported commitments for the 36 states with fragile situations included in the 2017 PRESS report were USD 507 million between 2013 and 2015 (Figure 4.2). This represents nearly one-third of global country-specific commitments during this period.6

Source: PARIS21 (2017), “Partner report on support to statistics” www.paris21.org/press2017.

The general trend for donor support is positive, as new providers of development co-operation beyond the DAC increasingly see the value of investments in development data. The United Arab Emirates, for examples, will host the second World Data Forum planned to take place in 2018. In 2016-17, donor support is expected to pick up, primarily driven by the changing donor landscape, with improved commitments from private foundations. The Bill & Melinda Gates and Hewlett Foundations are leading these efforts with commitments in 2016 of USD 13.2 million and USD 3 million, respectively (GPSDD, 2016). While these commitments are not yet reflected in the figures for 2015, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is now one of the major providers for statistical development (see the “In my view” piece by Sarah Hendriks). According to the 2017 PRESS report (PARIS21, 2017), it ranks among the top nine global providers in 2015 with a total commitment of USD 14 million.

It is not only a question of how much support, but also of how it is given

The way development co-operation providers deliver their support is also critical. PRESS 2016 shows that while grants are the main financing instrument used, the choice between grants and loans or credit differs widely from region to region. While Open Data Watch’s “Aid for statistics: 2016 inventory of financial instruments” also finds that trust-fund grants are the predominant type of funding used, its review of funding modalities notes that providers have several options for the delivery of increased funding (ODW, 2015). Table 4.1 summarises the strengths and weaknesses of each type of funding.

Traditional support to statistical capacity building is out of date

Statistical capacity building is described as a “process of changes at the levels of individuals, organisations, and enabling environments in a national statistical system through which the system obtains, strengthens, and maintains its capacities to set and achieve its own statistics development objectives over time” (UNJIU, 2016). Yet past efforts have not always yielded such outcomes. One of the main lessons of the past 20 years has been that top-down initiatives do not lead to sustained increases in capacity (Kiregyera, 2013). Today, the breadth and ambition of the SDGs have rendered past patterns of support outdated (Keijzer and Klingebiel, 2017).

What has gone wrong? Traditional efforts have been characterised by supply-driven, piecemeal approaches, with little emphasis placed on the endogenous demand for data. Rather, the emphasis was on the data needed by development co-operation providers for their monitoring, reporting and accountability. For instance, capacity building often prioritised making estimates of missing data values, such as HIV/AIDS prevalence rates, over building capacity in the national statistical office; or poverty lines were calculated by an external consultant that were impossible for anyone in the country to update or further analyse (Taylor, 2016). With this type of data production – driven by the desire to generate an immediate output needed by the external funder – short-term needs crowd out long-term effectiveness and sustainability.

What is needed is a demand-driven, holistic approach designed to strengthen the entire statistical system.

The results of a survey of DAC members’ policies and practices to support national statistical capacities and systems in developing countries show that DAC members provide support to improve developing countries’ statistical production mainly in the form of technical assistance (e.g. conducting training, designing surveys, building data management systems) (Sanna and Mc Donnell, 2017). While approaches such as these may identify and fix a broken piece in the data machine, they fail to consider the broader enabling environment or to reinforce the ability of the system to self-repair in the future. An approach addressing technical bottlenecks is not enough; what is needed is a demand-driven, holistic approach designed to strengthen the entire statistical system.

This is not to say that all previous efforts failed to yield results. The World Bank Statistical Capacity Indicator database shows slow but upward global and regional progress over the past 15 years. Yet the pace of this progress is not adequate if the global community is to match the scope and ambitions of the 2030 Agenda. Providers of development co-operation need to rethink how they provide support for statistics to address the remaining challenges and accelerate the pace.

To enable progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, data need to be managed as a cross-cutting priority

In the context of the data revolution, two forces drive the need for donors and their partners to re-evaluate past methods. First, the data ecosystem is expanding to include new producers and users of development data. Second, the SDGs place increased demands on national and international statistical agencies, including robust disaggregation of data on vulnerable populations or collection of new data for the SDG indicators. Co-ordination, innovation and funding are essential if the global community is to measure and track progress towards the 232 SDG indicators. By recognising development data as a strategic cross-cutting priority, similar to the environment and gender equality and women’s economic empowerment, and providing adequate funding, the international community can help to achieve this.

To be excluded from civil registration is, in many cases, synonymous with exclusion from public services.

Too often, support to statistics has been seen as an add-on to other sectoral projects. Over the years, the area of administrative data and civil registration has been neglected. For example, by one estimate, 83% of Africans live in countries without a complete and well-functioning birth registration system (Mo Ibrahim Foundation, 2016). There is a need to move beyond periodic surveys to continuous production of the data that enables countries to maintain complete records of births and deaths; these, in turn, dictate formal civic, personal, professional, business, and political activities and transactions. In many countries, civil registration enables individuals to be admitted into schools and hospitals, gain nationality and formal employment, vote or present themselves for electoral office, buy and transfer properties, or access financial and legal services. To be excluded from civil registration is, in many cases, synonymous with exclusion from public services.

The Cape Town Global Action Plan proposes a revitalised approach to statistical capacity development

There is international consensus around the principles that should guide a revitalised approach to statistical capacity development. In 2005, the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness7 stressed the importance of country ownership and harmonisation among providers of development co-operation. More recently, the Nairobi outcome document of the Second High-Level Meeting of the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC, 2016) committed aid providers to strengthening the statistical capacity of developing countries. Several recent international commitments include a clear call to put these development principles into practice in their support to statistics as a sector in itself and a cross-cutting issue.

These pledges signal strong international support for data and lay the ground for concrete operational steps. Yet the question remains of whether the pledges are being translated into practice. Table 4.2 summarises the degree of delivery against goals for a sample of high-level commitments on statistics. Success is measured in different ways: some have generated increased financial or political support while others have championed innovation and collaboration.

The United Nations (UN) Cape Town Global Action Plan for Sustainable Development Data (UNSC, 2017) is the most recent roadmap for improving global data for sustainable development and defining the role of development co-operation providers. The Global Action Plan provides a framework for planning and implementing statistical capacity building to achieve the scope and intent of the 2030 Agenda. The plan acknowledges that this work will be country-led and will occur at the subnational, national and regional levels. It aims to fully communicate and co-ordinate existing efforts, as well as to identify new and strategic ways to efficiently mobilise resources from international organisations, national governments and other partners.

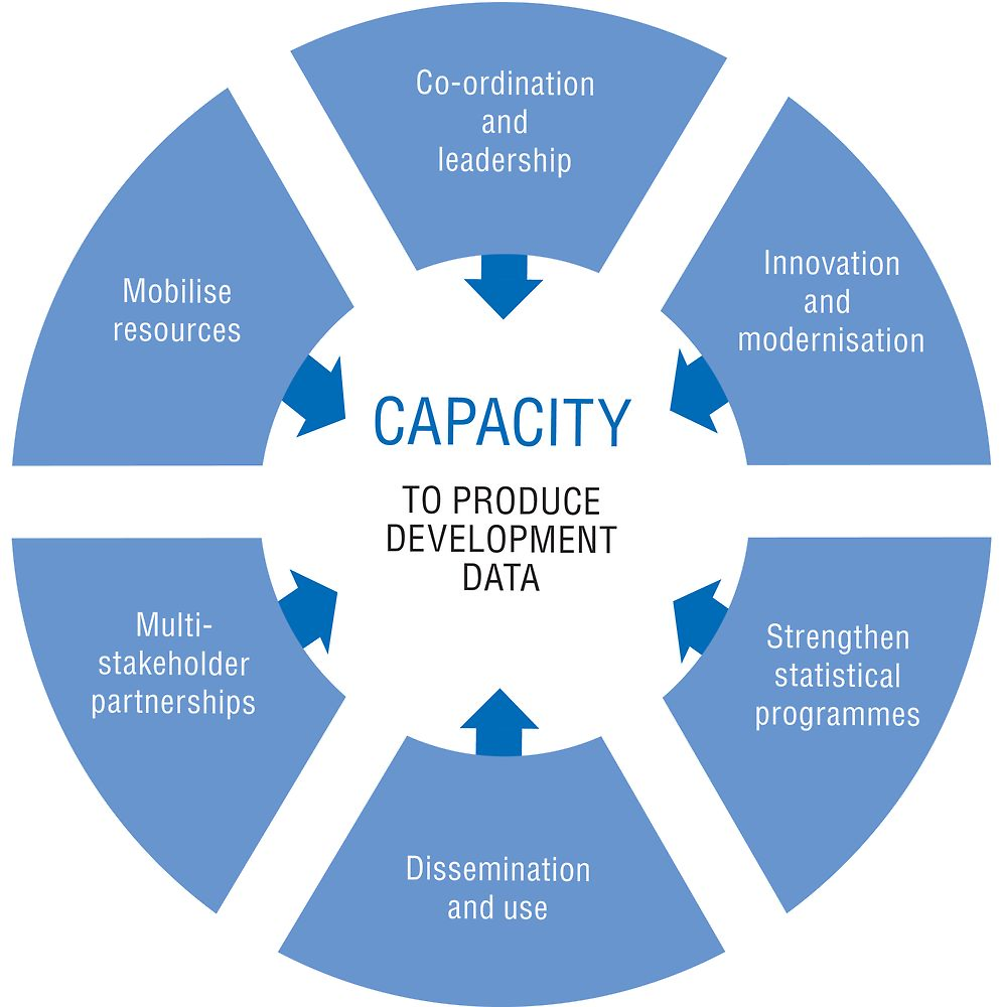

The Global Action Plan proposes action in six strategic areas, each associated with several objectives: 1) co-ordination and strategic leadership on data for sustainable development; 2) innovation and modernisation of national statistical systems; 3) strengthening of basic statistical activities and programmes; 4) dissemination and use of sustainable development data; 5) multi-stakeholder partnerships; and 6) mobilisation of resources and co-ordination of efforts for statistical capacity building. All of these aspects are integral to the capability to produce and use development data (Figure 4.3).

Source: Open Data Watch.

Lessons from research and evaluation on strengthening statistical systems

It is too soon to gauge the success of the Cape Town Global Action Plan. Nonetheless, several formal evaluations and other research conducted in recent years sheds light on some good practices for capacity building that link closely with strategic areas of the Cape Town Global Action Plan.8 Some lessons include the following:

-

National strategies for the development of statistics should be the starting point for designing capacity building, ensuring that providers of development co-operation do not follow a one-size-fits-all approach. As new approaches to strengthening statistical systems are explored it will be important to focus on comprehensive, co-ordinated interventions delivered through modalities that are appropriate for the entire set of stakeholders (Klingebiel, Casjen Mahn and Negre, 2016) and at the same time are aligned with the strategy and circumstances of the host country. The 2016 “Partner report on support to statistics” (PARIS21, 2016) showed good alignment of commitments with national strategies for the development of statistics and this alignment remains at an overall high level. Taking this good practice a step further, countries such as Sierra Leone are testing the idea of a “data compact” among all stakeholders in support of a well-articulated, results-based national plan (Box 4.1).

-

There is scope to increase focus on data literacy and use. A United Nations Population Fund evaluation of its census work found that the 2010 census “had a pre-eminent focus on enhancing the production of census-related data, placing disproportionally less attention on data dissemination, analysis, and use in policy making” (UNFPA, 2016). The full potential of census data is not realised because of an over emphasis on data production rather than use. A recent survey conducted by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe found that many national statistical offices actively promote user education – for example through publications and booklets tailored to specific user groups; seminars; user-friendly guides; and awareness campaigns such as National Statistics Month. Yet all of the developing countries participating in the survey reported that they lack resources for user education (UNECE, 2016).

-

Co-ordination of statistical capacity building reduces transaction costs. Evaluations conducted by the World Bank Trust Fund for Statistical Capacity Building flagged the small size of individual stand-alone grants and the resulting loss of cost effectiveness (ODW, 2015). Methods such as pooling of resources among various providers reduce transaction costs and enable greater effectiveness and efficiency. One of the main challenges listed by DAC members in relation to making data work for sustainable development is the lack of systematic co-ordination among providers of development co-operation to support statistical capacity building (Sanna and Mc Donnell, 2017). An evaluation of capacity-building efforts by the International Monetary Fund found that giving responsibility for co-ordination to a single government institution was highly effective in increasing harmonisation among providers. In this way, a “lead donor” is identified by each country with the responsibility for the overall work strategy remaining with the country (ODW, 2015).

-

Multi-stakeholder partnerships can mobilise more resources for sustainable development data. While domestic resources mobilised by individual countries can help close the funding gap for statistics (SDSN, 2015) public-private partnerships offer more room for innovation and risk-taking than traditional funding modalities. Innovative funding mechanisms – such as peer-to-peer support (e.g. the twinning partnership between the Japan International Cooperation Agency and Cambodia) and incentive funds (i.e. the World Bank’s innovation fund) – can also offer valuable alternatives.

In developing countries, data compacts can incite governments to:

-

Commit to and implement a national strategy for the development of statistics that, as far as possible, meets the disaggregated data needs of the 2030 Agenda and explores the integration of non-traditional data providers and users.

-

Ensure that statistical legislation is up to date and in line with the UN Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics.

-

Ensure that the skills required to perform the data-related activities are available.

-

Promote the effective co-ordination of data-related activities and ensure a proper scheduling of surveys to guarantee a regular data flow.

-

Promote access to and use of data and statistics based on open data principles.

-

Ensure data-related activities are adequately funded.

In turn, external funders – including bilateral providers of development co-operation, multilateral agencies, development banks and others – can be required to:

-

Incentivise results-based financing and improve support for data-related activities, including funding based on demonstrated impact from or progress towards the production of high-quality data and the promotion of data use.

-

Provide funding or in-kind support for technical assistance to strengthen the capacity of data providers and users.

-

Ensure activities are aligned with the national strategy for the development of statistics and/or the national development plan, and that they are co-ordinated with other providers.

-

Provide support in ways that minimise the burden on countries and make use of local processes and data.

-

Support funding initiatives that increase domestic resources in support of statistics (e.g. new taxes, a national fund).

-

Undertake research and development to promote and support innovation.

Moving from traditional to revitalised support

In addition to the Cape Town Global Action Plan, the revitalisation of statistical capacity development has been reinforced by recent international fora.9 Table 4.3 compares the principles of a traditional donor approach to statistical capacity development with a vision of what a revitalised approach would entail.

The way forward for supporting statistical capacity building

The 2030 Agenda to end poverty, build sustainable growth and prosperity, and improve lives while leaving no one behind, combined with the untapped power of the data revolution, put us at an exceptional pivotal moment. To advance using the framework articulated in the Cape Town Global Action Plan, the shortcomings of donor support for development data outlined in this chapter must be addressed. In short, we need to raise the level of political support for the sustainable development data agenda; align donor support and country ownership; build a stronger culture of focus on results; and tackle donor co-ordination issues in the statistics sector. Among many possible actions, this chapter prioritises three sets of recommendations, largely motivated by the potential of these changes to yield high returns, combined with a focus on goals that are achievable in three to five years.

1. Raise the level of political support for sustainable development data

Policy and technical discussions on data to support sustainable development occur mostly within the statistical community. Technical discussions have been fruitful in articulating the data infrastructure needed at the national level, highlighting the capacity challenges in developing countries, estimating the required level of investment and reviewing the support mechanisms for data for development. While this information is invaluable for understanding the current state of affairs within the data revolution, deliberations need to move to the political sphere.

In developing countries, senior officials from the Finance and Planning Ministries as well as central government units such as the Chancellery or Office of the President need to be more involved and engaged in national data production discussions. The SDG data indicator debate, which has just started to unfold, offers a good opportunity for the heads of national statistical offices to “step up, step forward and step on the gas”, as John Pullinger, the National Statistician for the United Kingdom, has eloquently put it, raising data in the public debate. Most senior government officials will understand the need to engage in data for development debates, in particular if they have seen concrete examples of how national data can be instrumental in demonstrating the impact of their policies.

The “data” topic is universal, cross-cutting and highly underrated.

In countries that provide development co-operation, the heads of aid agencies and ministries need to be made aware that the “data” topic is universal, cross-cutting and highly underrated – comparable to gender equality some ten years ago. In many DAC countries the issue of “data” is dealt with either in the “sector” department – much as health, education or agriculture – and/or are part of the “governance/public sector” portfolio. In the new age of data, data for development have an intrinsic and instrumental value, and development co-operation needs to adjust to this reality. DAC countries could make an important contribution to improving the production of data that matters for people; for example, a work stream within the OECD DAC could look at good practices and develop guidelines for how to best engage in this new field.

Data for development should be recognised as part of the essential infrastructure for delivering on national, regional and global development commitments. The OECD DAC, the G20, the UN General Assembly, and other high-level strategic and political fora can lead efforts to build awareness of and support for the data for development agenda. Data for development discussions at high-level fora can also be used to review the status of work towards existing commitments.

2. Establish co-ordinated and effective donor support for development data

A business-as-usual approach will not suffice to enable the urgent changes needed in national statistical capacity and the related support systems. Analyses of how ODA is distributed for development data projects show that statistics are in fact underfunded despite the widespread discussions of their central role in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Furthermore, the evidence suggests that funding for data for development is not strategically allocated or efficiently used. Rather, it is largely concentrated among a few providers and goes to a relatively small number of countries (PARIS21, 2017).

Build an alliance for improved effectiveness of assistance for development data

One way of responding to the need for increased donor co-ordination would be to build a formal alliance among providers in support of development data. A Development Data Donors’ Alliance (hereafter referred to as “the Alliance”) could share strategic plans as well as information on focus countries, sectors, support for specialised activities, tools and portals. Such an alliance could produce marked improvements in the distribution, sequencing and monitoring of support for development data. Providers would need to remain flexible and open to make needed adjustments over time in setting their priorities.

An alliance could produce marked improvements in the distribution, sequencing and monitoring of support for development data.

The Alliance could also help to bring in new partners and ways of delivering support. The data revolution includes many new players who have much to contribute to the functioning of official statistical systems. The private sector, particularly information and communications technology firms, have unique datasets and technical expertise to share. As users of official statistics, businesses can be incentivised to join with traditional providers in funding improvements in statistical systems.

Create data compacts for a country-led development data revolution

Improved management of aid for data and statistics in the form of a data compact, where both parties agree on a set of criteria, could address some of the current stumbling blocks to ensuring holistic demand-driven support. A data compact can facilitate such interactions, allowing all the stakeholders involved in a country’s statistical development – national governments, external funders, citizen groups, media and technical agencies – the opportunity to come together at an early stage of planning and jointly establish a development data action plan (Box 4.1). By signing and committing to a data compact they establish a performance agreement based on the individual country’s own national plans. Through the data compact, the plan is underpinned by financing from domestic and international sources and can build in incentives for data quality improvements, open data, promoting data use and data impact. The agreement can also create momentum for bringing new stakeholders, partners and providers of development co-operation into the data compact discussions.

The data compact idea has been discussed in several studies of development data funding and capacity-building needs (PARIS21, 2015; GPSDD, 2016; CGD, 2014; UNECA, 2016). However, the concept has not been fully tested or implemented. This is mainly because no one development agency so far has been able to take on the convening role among the diverse group of stakeholders. PARIS21 is in a good position to pilot data compacts in a few countries and, based on the outcome, help to scale up the concept as a natural next step for countries that are updating an older national strategy for the development of statistics or establishing a new one.

Improve monitoring and establish a marker for development data

Measuring support to statistics comes with many methodological challenges. The PARIS21 Secretariat has identified best practices in reporting and begun to promote their implementation. If followed by more aid providers, their use would result in considerable improvements of current reporting and co-ordination, for example:

-

To circumvent the issue of double counting that arises when providers and implementing agencies report the same activity twice, multilateral reporters to the PRESS questionnaire indicate their role as “implementer” (rather than “donor”) when they manage or implement a project financed by another donor. Such reporting allows the PARIS21 Secretariat to ensure that these commitments appear only once in the global number, resulting in a more accurate estimate.

-

To solve the problem of counting project totals for multi-recipient projects, some OECD-DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS) reporters already split their projects into sub-projects – one per recipient country – with each specifying the respective share of the total project commitment that goes to statistics. PARIS21 has incorporated this practice in its methodology and encourages its use.

-

Finally, with the current call for a substantial increase in support to statistics, it is important to assess each country’s absorptive capacity, ensuring that it can make effective use of an increase in funding. To this end, ODA reporting needs to go beyond commitments, also recording actual disbursements of funding as well as domestic resources invested in statistics. The PARIS21 Secretariat provides technical support to countries in producing complete budgets.

To establish a fully functional system that measures the real support to statistics, however, a marker for development data in the CRS will be indispensable. Although there is a CRS sector code for statistical capacity building, it fails, for example, to identify multi-sector projects that comprise only a small statistics component. Aside from improving the identification of the many related projects in ODA reporting, this would also acknowledge the strategic importance of statistical capacity building. A marker would also help systems that build on the CRS system, such as the International Aid Transparency Initiative and AidData, to track aid data. At the same time, it is important that there be wide participation in efforts to increase the transparency of funding for development data. This includes the participation of philanthropic organisations, which should follow the example of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation by providing data on their funding. A task force could be established to consider ways for funding agencies to make data on support to statistics more open and accessible.

3. Support the 2030 Agenda through the 2020 census round

Developing countries require prompt action on many fronts, and needs vary from country to country. One area, however, requires immediate global support: the preparation of the 2020 census round. The 2020 global census is critical for the implementation of the SDGs.

The Millennium Development Goals created global momentum behind planning and financing the 2010 census round, and this was one of their significant successes. Without a concerted global effort to replicate this success in 2020, many people will be left behind. Censuses yield population numbers, and these are the denominator of a large portion of the 232 agreed-upon SDG indicators. However, no one community or organisation alone, be it senior development policy makers, providers of development co-operation, technical specialists, non-governmental organisations or operational teams, can move the needle on this agenda. It requires collective action by all stakeholders (Box 4.2).

Established principles can guide the 2020 census to ensure its effectiveness in contributing to the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

-

Collect the data once – use it many times: Tap into existing data sources; build data analysis skills nationally and regionally; focus on improving the frequency of updating and the level of disaggregation of the existing data.

-

Focus on filling core gaps: Make sure that all countries produce core statistics for monitoring their economic, social and environmental progress.

-

Ensure essential rights: Make data part of the right to be counted; to access information; to participate (through citizen-generated data); and to privacy and ownership of personal data (anonymity and quality standards).

-

Support co-ordination: Ensure new data ecosystems (new collaborative and co-operative arrangements) do not disrupt the governance of data at the country level; fund alternative data collections in co-ordination with national representatives.

-

Uphold diversity: Each country has a unique national data ecosystem, depending on its socio-economic, political and legal environment.

-

Leverage innovation: New data technologies can help to fill the data gaps identified in national strategies.

-

Move away from projects and programmes: Manage for development results by investing in whole-of-government approaches through national strategies.

-

Look beyond the SDGs: Promote systemic improvement by embedding action in national statistical systems and not only generating information on specific indicators.

-

Focus on outcomes: Make sure issues are monitored from a results-based perspective (for instance, that school enrolment rates are accompanied by learning assessments).

Priority steps in rethinking donor support for statistical capacity building

-

Raise the profile of data for development at the highest political level.

-

Treat data for development as a cross-cutting priority, viewing it as both a key means of achieving the SDGs and as an integral goal in itself.

-

Revitalise support to development data; acknowledge the need for building the statistical capacity of developing countries.

-

Increase domestic, international and private support for statistics and align support with national statistical plans and priorities.

-

Ensure that strengthening of national systems is country driven.

-

Focus on data use and users, as well as on dissemination and format.

-

Establish co-ordinated and effective donor support for development data; build partnerships and co-operation.

-

Increase the use of new funding mechanisms with a result-based focus.

-

Improve monitoring, tracking and transparency of investments in development data.

-

Contribute to the 2030 Agenda by supporting preparations for the 2020 census round.

References

Burgess, S. et al. (2013), “A natural experiment in school accountability: The impact of school performance information on pupil progress”, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 106, pp. 57-67, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.06.005.

CGD (2014), Delivering on the Data Revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa: Final Report of the Data for African Development Working Group, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC, www.cgdev.org/publication/delivering-data-revolution-sub-saharan-africa-0.

GPEDC (2016), “Nairobi outcome document” of the Second High-Level Meeting of the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation, Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation, http://effectivecooperation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/OutcomeDocumentEnglish.pdf.

GPSDD (2016), “The state of development data funding 2016”, Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, http://opendatawatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/development-data-funding-2016.pdf.

IEAG (2014), “A world that counts: Mobilizing the data revolution for sustainable development”, Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development, United Nations, New York, www.undatarevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/A-World-That-Counts.pdf.

Keijzer, N. and S. Klingebiel (2017), “Realising the data revolution for sustainable development: Towards capacity development 4.0”, PARIS21 Discussion Paper, No. 9, Partnership in Statistics for Development in the 21st Century, Paris, www.paris21.org/sites/default/files/CapacityDevelopment4.0_FINAL_0.pdf.

Kiregyera, B. (2013), “The emerging data revolution in Africa: Strengthening the statistics, policy and decision-making chain”, Sun Press.

Klingebiel, S., T. Casjen Mahn and M. Negre (eds.) (2016), “Fragmentation: A key concept for development cooperation”, in: The Fragmentation of Aid: Concepts, Measurements and Implications for Development Cooperation, Palgrave Macmillan, United Kingdom, www.palgrave.com/de/book/9781137553560.

Mo Ibrahim Foundation (2016), “Strength in numbers: Africa’s data revolution”, Mo Ibrahim Foundation, http://s.mo.ibrahim.foundation/u/2016/05/16162558/Strength-in-Numbers.pdf.

ODW (2015), “Aid for statistics: An inventory of financial instruments”, Open Data Watch, Washington, DC, http://opendatawatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Aid-For-Statistics-An-Inventory-of-Financial-Instruments.pdf.

PARIS21 (2017), “Partner report on support to statistics: PRESS 2017”, Partnership in Statistics for Development in the 21st Century, OECD, Paris, www.paris21.org/press2017.

PARIS21 (2016), “Partner report on support to statistics: PRESS 2016”, Partnership in Statistics for Development in the 21st Century, OECD, Paris, www.paris21.org/sites/default/files/PRESS-2016-web-final.pdf.

PARIS21 (2015), A Road Map for a Country-led Data Revolution, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264234703-en.

PARIS21 (2011), Statistics for Transparency, Accountability, and Results: A Busan Action Plan for Statistics, Partnership in Statistics for Development in the 21st Century, OECD, Paris, www.paris21.org/sites/default/files/Busanactionplan_ nov2011.pdf.

Sanna, V. and I. Mc Donnell (2017), “Data for development: DAC member priorities and challenges”, OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers, No. 35, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6e342488-en.

SDSN (2015), “Data for development: A needs assessment for SDG monitoring and statistical capacity development”, United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network, New York, http://unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Data-for-Development-Full-Report.pdf.

Taylor, M. (2016), “The political economy of statistical capacity: A theoretical approach”, Inter-American Development Bank Discussion Paper, IDB-DP-471, Inter-American Development Bank, https://publications.iadb.org/bitstream/handle/11319/7794/ThePolitical-Economy-of-Statistical-Capacity-A-Theoretical-Approach.pdf?sequence=2.

UN (2015a), “Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development (Addis Ababa Action Agenda)”, United Nations, New York, www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/AAAA_Outcome.pdf.

UN (2015b), The Millennium Development Goals Report, United Nations, New York, www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf.

UN (2015c), “Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, United Nations, New York, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication.

UNECA (2016), “The Africa data revolution report 2016: Highlighting developments in African data ecosystems”, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, www.africa.undp.org/content/rba/en/home/library/reports/the_africa_data_revolution_report_2016.html.

UNECE (2016), “Value of official statistics – interim report”, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/documents/ece/ces/2016/mtg/CES_11_-ENG_G1602756.pdf.

UNFPA (2016), “Evaluation of UNFPA support to population and housing census data to inform decision-making and policy formulation 2005-2014”, Evaluation Brief, Evaluation Office, United Nations Population Fund, New York, www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/admin-resource/Evaluation_report_-_Volume.pdf.

UNJIU (2016), “Independent system-wide evaluation of operational activities for development: Evaluation of the contribution of the United Nations development system to strengthening national capacities for statistical analysis and data collection to support the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals and other internationally agreed development goals: Technical appendix”, United Nations Joint Inspection Unit, www.unjiu.org/en/reports-notes/CEB%20and%20organisation%20documents/Technical%20Appendix_JIU_REP_2016_5_Final.pdf.

UNSC (2017), “Cape Town Global Action Plan for Sustainable Development Data”, United Nations Statistics Commission, New York, http://undataforum.org/WorldDataForum/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Cape-Town-Action-Plan-For-Data-Jan2017.pdf.

UNSD (2015), UN Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics – Implementation Guidelines 2015, United Nations Statistics Division, United Nations, New York, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/dnss/gp/Implementation_Guidelines_FINAL_without_edit.pdf.

Vaitla, B. et al. (2017), “Phone records track malaria”, in: Data Impacts: Case Studies from the Data Revolution, Data Impacts, http://dataimpacts.org/project/malaria.

World Bank (2017), Statistical Capacity Indicators (database), http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=statistical-capacity-indicators#.

World Bank (2016), Global Financing Facility website, www.globalfinancingfacility.org.

World Bank (2004), “Marrakech Action Plan for Statistics”, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, www.worldbank.org/en/data/statistical-capacity-building/marrakech-action-plan-for-statistics.

Further reading

GPSDD (n.d.), “Data roadmaps for sustainable development guidelines”, webpage, Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, www.data4sdgs.org/data-roadmaps-for-sustainable-development-guidelines.

GWG (2015) , “Principles for Access to Big Data Sources”, United Nations Global Working Group on Big Data for Official Statistics, United Nations, New York, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/trade/events/2015/abudhabi/gwg/GWG%202015%20-%20item%202%20(ii)%20-%20Draft%20Access%20Principles%20-%20TTAP%20deliverable%202.pdf.

Klein, T. and S. Verhulst (2017), “Access to new data sources for statistics: Business models and incentives for the corporate sector”, PARIS21 Discussion Paper, No. 10, Partnership in Statistics for Development in the 21st Century, Paris, www.paris21.org/sites/default/files/Paper_new-data-sources_final.pdf.

Robin, N., T. Klein and J. Jütting (2016), “Public-private partnerships for statistics: Lessons learned, future steps: A focus on the use of non-official data sources for national statistics and public policy”, OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers, No. 27, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jm3nqp1g8wf-en.

UN (2016), Framework for the Development of Environment Statistics (FDES 2013), United Nations Statistics Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/ENVIRONMENT/FDES/FDES-2015-supporting-tools/FDES.pdf.

UN (2014), “Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics”, United Nations General Assembly, New York, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/dnss/gp/FP-New-E.pdf.

Notes

← 1. Shaida Badiee, Deirdre Appel and Eric Swanson from Open Data Watch; and El Iza Mohamedou and Thilo Klein from PARIS21.

← 2. Target 17.18: “By 2020, enhance capacity-building support to developing countries, including for least developed countries and small island developing states, to increase significantly the availability of high-quality, timely and reliable data disaggregated by income, gender, age, race, ethnicity, migratory status, disability, geographic location and other characteristics relevant in national contexts.” Target 17.19: “By 2030, build on existing initiatives to develop measurements of progress on sustainable development that complement gross domestic product, and support statistical capacity-building in developing countries.”

← 3. The United Nations Secretary-General’s report, “A world that counts”, says “Data are the lifeblood of decision-making and the raw material for accountability. Without high-quality data providing the right information on the right things at the right time, designing, monitoring and evaluating effective policies becomes almost impossible” (IEAG, 2014). More recently, the Cape Town Global Action Plan for Sustainable Development Data calls for a “global pact or alliance that recognises the funding of national statistical system modernisation efforts is essential to the full implementation of Agenda 2030” (UNSC, 2017).

← 4. The 2017 PARIS21 “Partner report on support to statistics” uses data from an annual donor survey and from the OECD-DAC Creditor Reporting System to report on commitments to statistical capacity building from 2006 to 2015. It measures financial support from multilateral and bilateral providers covering all areas of statistics, from national accounts to human resources and training (PARIS21, 2017).

← 5. The top five providers of support for statistics in 2015 were the African Development Bank, Canada, the European Commission/EUROSTAT, the United Nations Population Fund and the World Bank. The International Monetary Fund, which was one of the top five donors in 2014, did not make the deadline to report to PRESS 2017. Its commitments to statistical development will be included in PRESS 2018.

← 6. For the purposes of this report, the definition for fragility and the identification of countries satisfying those criteria are drawn from the World Bank’s harmonised list of fragile states, available at: http://go.worldbank.org/BNFOS8V3S0.

← 7. See: www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/parisdeclarationandaccraagendaforaction.htm.

← 8. In 2015, Open Data Watch released a report highlighting lessons learnt from 27 evaluations of statistical capacity programmes (ODW, 2015). The UN has also published a document on the implementation of the Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, which helps illustrate the needs of national statistical offices and highlight what they find works well (UNSD, 2015). Another evaluation looks at lessons learnt from international statistical capacity building during the era of the Millennium Development Goals and applies these lessons to the 2030 Agenda (UNJIU, 2016).

← 9. These include the Capacity Development track at the 2017 United Nations World Data Forum in Cape Town, the 2017 PARIS21 Annual Meeting on “Revisiting Capacity Development to Deliver on the SDGs”, and several events during the 48th Session of the United Nations Statistical Commission.