Annex C. Description of proposed rebate system for WSS in Moldova

The text below is an extract from (OECD, 2017[1]).

A rebate system can provide the most flexibility, targeting and cost-efficient way to establish a social measure in WSS. It may also be applied to the cost of connection. The rebate system intends to support low-income customers by providing a lump sum discount on the WSS bill. It has been chosen because it:

-

may be designed to target low-income groups more specifically than its alternatives (in particular Increasing Block Tariffs)

-

may be designed to leave room for local customisation

-

is relatively simple to administer

-

has a high degree of flexibility so it can be adjusted or abolished over time

-

gives incentives for customers to pay bills on time

-

may be designed so it does not affect the ability of the Apacanal to recover its costs.

It is called the rebate system because it provides a lump sum discount for some or all household customers i.e. between 0% and 100% of households may be made eligible for the system.

The rebate system does not change the average value of the household bill because it is an internal subsidy from households to households. It is paid for by households that are better off. The decision on the design of the rebate system stands apart from the affordability percentage. If tariffs are unaffordable for the population at large, the rebate system cannot solve that. If tariffs are unaffordable for a part of the population, the rebate system can address that, but only insofar as other customers can be obliged to compensate for the discount provided to the eligible group.

Therefore, the Apacanal will not be worse because of the rebate system. On the contrary, it may lead to a better payment discipline because the rebate can be realised only upon payment of the bill. To the extent that rebates cannot be fully realised, they even provide extra revenue to the service provider. First, rebates cannot be realised in case of late payment i.e. the rebate expires. Second, by definition, the rebate cannot lead to negative income for the Apacanal provider on a particular bill. If someone’s bill is lower than the size of the rebate, then one can realise only up to the amount of the bill. The rebate may be realised only against the pure revenue of the service provider. Other taxes and charges remain payable. Because such taxes and charges may be levied on top of the revenues of the service provider, a complication may occur. However, since a discount for rapid payment is widely used in other sectors of the economy, it is expected that fiscal authorities can accept this instrument.

First, the percentage of redistribution for the Apacanal must be decided. This discretion may be left to the Apacanal, to the municipality or to the Apacanal with a requirement for consultation.

The regulator should set an appropriate maximum to protect well-off customers from paying a too large part of the total household utilities water bill. Table A F.1 sets this maximum percentage at 25%. At this level, the invoiced tariff per cubic metre will get very large. This may incur political acceptability issues. Let us suppose the Apacanal wants to use 15%.

This means the following:

-

The revenue requirement is increased by 15%.

-

The household tariff goes up by 15%.

-

The resulting extra amount of revenue is distributed among customers as a discount.

The rebate is provided to 0%-100% of customers. Those customers that receive the rebate, AND pay their water bill on time AND consume a relatively small amount of water pay less per cubic metre than other customers. This achieves exactly the intended effect of Increasing Block Tariffs, but more efficiently and effectively. Instead of providing a full rebate, certain households may receive a partial rebate, for instance linked to income level. In this way, poverty traps can be mitigated. One may also link the size of the rebate to the number of inhabitants in the households (as is done in the Netherlands). Local customisation to specific circumstances is possible as well.

Apart from setting a maximum percentage for redistribution, the regulator may leave freedom to the local community to decide on the size of the rebate and conditions for eligibility. This is more a social question that can be resolved in the given framework of the rebate system (whereby individual metering is a key condition).

-

Some communities may want to structure the rebate as a lifeline and make the first cubic metres of water virtually free. This requires only a small rebate percentage.

-

Others want to target the instrument to a wider group of vulnerable people. This requires a higher percentage and wider eligibility.

-

Yet others may want to use it as an instrument for water conservation. In that case, everyone may be eligible.

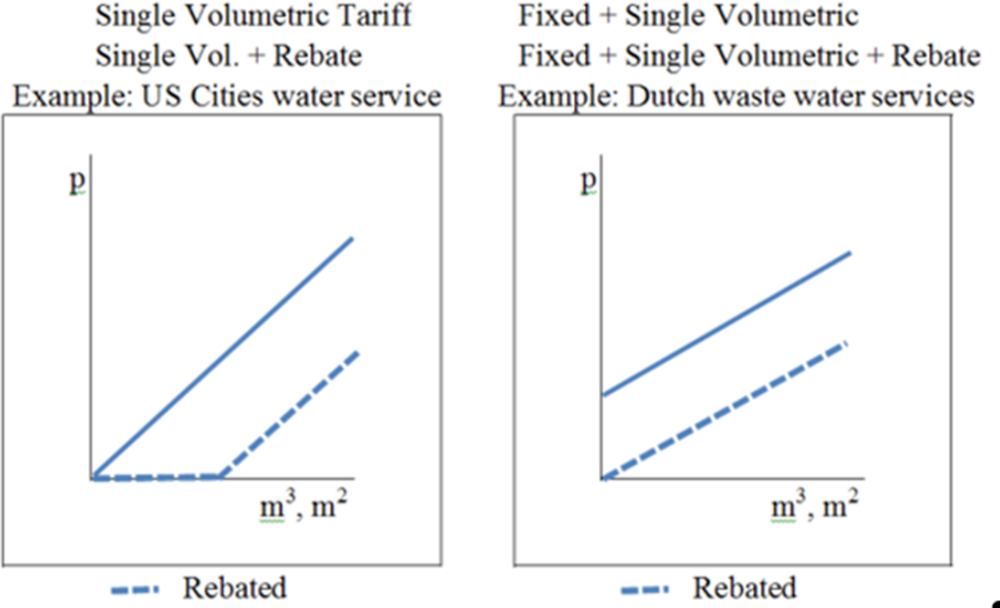

Neither the average tariff, nor the affordability criterion, nor the average value of the bill are affected through the rebate. Because of its progressive effect, the rebate will increase the number of people for whom water services are affordable. There will always be people who cannot afford water services or need additional social assistance. Through the rebate, such cases are reduced rapidly and efficiently. It is therefore a very good first step in the process of building up social WSS measures. As a result of the rebate, everyone that keeps water consumption to an absolute minimum will have a low water bill. Table A C.1shows the rebate mechanism works in a fictitious numerical example. In this case, the rebate is phased out over a number of years; communities may also opt for a permanent rebate. Figure C.1 compares volumetric tariff with and without rebate.

If local governments are given limited discretion in setting the rebate percentage, they should be made aware of policy instruments available. They also know about the room for local customisation (the percentage of projected household revenues that will be redistributed and the eligibility criteria for a rebate).

If the rebate is made available to specific groups, local government will have to set the criteria, inform local community and take responsibility for verification.

References

[23] ANSRC (2014), Presentation of National Regulatory Authority for Municipal Services of Romania, http://www.danube-water-program.org/media/dwc_presentations/day_0/Regulators_meeting/2._Cador_Romania_Viena_ANRSC.pdf.

[6] Berg, S. et al. (2013), “Best practices in regulating State-owned and municipal water utilities”, http://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/4079/S2013252_en.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 8 February 2018).

[13] CASTALIA (2005), Defining Economic Regulation for the Water Sector, https://ppiaf.org/sites/ppiaf.org/files/documents/toolkits/Cross-Border-Infrastructure-Toolkit/Cross-Border%20Compilation%20ver%2029%20Jan%2007/Resources/Castalia%20-%20Defining%20Economic%20%20Regulation%20Water%20Sector.pdf.

[12] Demsetz, H. (1968), “Why Regulate Utilities?”, Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 11, pp. 55-65.

[25] EAP Task Force (2013), Business Models for Rural Sanitation in Moldova, https://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/Business%20models%20for%20rural%20sanitation%20in%20Moldova_ENG%20web.pdf.

[19] Eptisa (2012), Republic of Moldova’s Water Supply and Sanitation Strategy (Revised Version 2012), http://www.serviciilocale.md/public/files/2nd_Draft_WSS_Strategy_October_final_Eng.pdf.

[4] Geert Engelsman, M. (2016), Review of success stories in urban water utility reform, https://www.seco-cooperation.admin.ch/dam/secocoop/de/dokumente/themen/institutionen-dienstleistungen/Review%20of%20Successful%20Urban%20Water%20Utility%20Reforms%20Final%20Version.pdf.download.pdf/Review%20of%20Successful%20Urban%20Water%20Utility%20Reforms%20Final%20Version.pdf.

[29] Massarutto, A. (2013), Italian water pricing reform between technical rules and political will, http://www.feem-project.net/epiwater/docs/epi-water_policy-paper_no05.pdf.

[17] Ministry of Environment of Republic of Moldova (n.d.), Reports on Performance in 2010-2015, http://mediu.gov.md/index.php/en/component/content/article?id=72:fondul-ecologic-national&catid=79:institutii-subordonate.

[1] OECD (2017), Improving Domestic Financial Support Mechanisms in Moldova’s Water and Sanitation Sector, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252202-en.

[22] OECD (2017), Improving Domestic Financial Support Mechanisms in Moldova’s Water and Sanitation Sector, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252202-en.

[20] OECD (2016), OECD Council Recommendation on Water, https://www.oecd.org/environment/resources/Council-Recommendation-on-water.pdf.

[24] OECD (2016), Sustainable Business Models for Water Supply and Sanitation in Small Towns and Rural Settlements in Kazakhstan, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264249400-en.

[28] OECD (2015), “Regulatory Impact Analysis”, in Government at a Glance 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2015-39-en.

[32] OECD (2015), The Governance of Water Regulators, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264231092-en (accessed on 7 February 2018).

[5] OECD (2014), The governance of regulators..

[21] OECD (2010), Innovative Financing Mechanisms for the Water Sector, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264083660-en.

[30] OECD (2010), Innovative Financing Mechanisms for the Water Sector, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264083660-en.

[3] OECD EAP Task Force (2013), Adapting Water Supply and Sanitation to Climate Change in Moldova, https://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/Feasible%20adaptation%20strategy%20for%20WSS%20in%20Moldova_ENG%20web.pdf.

[10] OECD EAP Task Force (2007), Proposed system of surface water quality standards for Moldova: Technical Report, http://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/38120922.pdf.

[18] OECD EAP Task Force (2003), Key Issues and Recommendations for Consumer Protection: Affordability, Social Protection, and Public Participation in Urban Water Sector Reform in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia, http://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/14636760.pdf.

[14] OECD EAP Task Force (2000), Guiding Principles for Reform of the Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Sector in the NIS.

[16] Pienaru, A. (2014), Modernization of local public services in the Republic of Moldova, http://www.serviciilocale.md/public/files/prs/2014_09_18_WSS_RSP_DRN_FINAL_EN.pdf.

[27] Popa T. (2014), “A smart mechanism for financing water services and instrastructure” IWA, https://www.iwapublishing.com/sites/default/files/documents/online-pdfs/WUMI%209%20%281%29%20-%20Mar14.pdf.

[35] Programme, U. (ed.) (2015), Human Development Report 2015: Work for Human Development, Communications Development Incorporated, Washington DC, https://doi.org/978-92-1-057615-4.

[31] Rouse, M. (2007), Institutional Governance and Regulation of Water Services | IWA Publishing, IWA, London, https://www.iwapublishing.com/books/9781843391340/institutional-governance-and-regulation-water-services.

[7] Smets, H. (2012), “CHARGING THE POOR FOR DRINKING WATER The experience of continental European countries concerning the supply of drinking water to poor users”, http://www.publicpolicy.ie/wp-content/uploads/Water-for-Poor-People-Lessons-from-France-Belgium.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2018).

[8] Trémolet, S. and C. Hunt (2006), “Water Supply and Sanitation Working Notes TAKING ACCOUNT OF THE POOR IN WATER SECTOR REGULATION”, http://regulationbodyofknowledge.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Tremolet_Taking_into_Account.pdf.

[9] Tuck, L. et al. (2013), “Water Sector Regionalization Review. Republic of Moldova.”, http://www.danubis.org//files/File/country_resources/user_uploads/WB%20Regionalization%20Review%20Moldova%202013.pdf.

[34] UN (2015), Sustainable Development Goals, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

[15] UNDP (2009), “Climate Change in Moldova”, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/nhdr_moldova_2009-10_en.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

[11] UNECE (2014), Environmental performance review, Republic of Moldova. Third Review Synopsis., UNECE, https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/epr/epr_studies/Synopsis/ECECEP171_Synopsis.pdf.

[33] UNEP (2014), Environmental strategy years 2014-2023, https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/report/environmental-strategy-years-2014-2023.

[26] Verbeeck, G. (2013), Increasing market-based external finance for investment in municipal infrastructure, https://www.iwapublishing.com/sites/default/files/documents/online-pdfs/WUMI%208%20%284%29%20-%20Dec13.pdf.

[2] Verbeeck, G. and B. Vucijak (2014), “Towards effective social measures in WSS”, Towards effective social measures in WSS, https://1drv.ms/b/s!Anl6ybs2I7QGhdUX96FsaFC6JTUpIA.