4. Special Feature: Tax and fiscal policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis

This Special Feature takes stock of the tax measures that have been introduced to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 crisis from the beginning of the virus outbreak up to mid-June 2020. This Special Feature focuses on tax measures, but it also touches upon the broader fiscal policy responses that countries have introduced. It covers all OECD countries as well as Argentina, China, Indonesia and South Africa, based on a database compiled by the OECD on tax and fiscal policy responses to the crisis.

Governments have taken rapid and unprecedented action to address the health crisis and the drop in economic activity caused by the outbreak of COVID-19. Containing and mitigating the spread of the virus has rightly been the first priority of public authorities. With containment measures in place, the immediate policy reactions focused on alleviating hardships and maintaining the productive capacity of the economy. As the duration of the pandemic lengthens and uncertainty about its development remains high, countries have begun extending and expanding emergency policy measures. Some countries have recently relaxed their containment rules, announcing recovery and stimulus packages to forge a new path towards stronger, more inclusive and resilient economies.

This Special Feature takes stock of the tax measures that have been introduced to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, as well as early steps that countries have taken towards economic recovery. This Special Feature focuses on tax measures, but it also touches upon broader fiscal measures that countries have introduced. It covers OECD countries as well as Argentina, China, Indonesia and South Africa, based on a database compiled by the OECD on tax policy responses to the crisis.1 The first section outlines the policy phases that countries are expected to go through as they respond to the crisis. The second section gives an overview of the policy measures implemented or announced from the beginning of the virus outbreak up to mid-June 2020. The third and fourth sections provide more detail on policies to support business and households, respectively. The final section discusses the measures taken to support the healthcare sector.

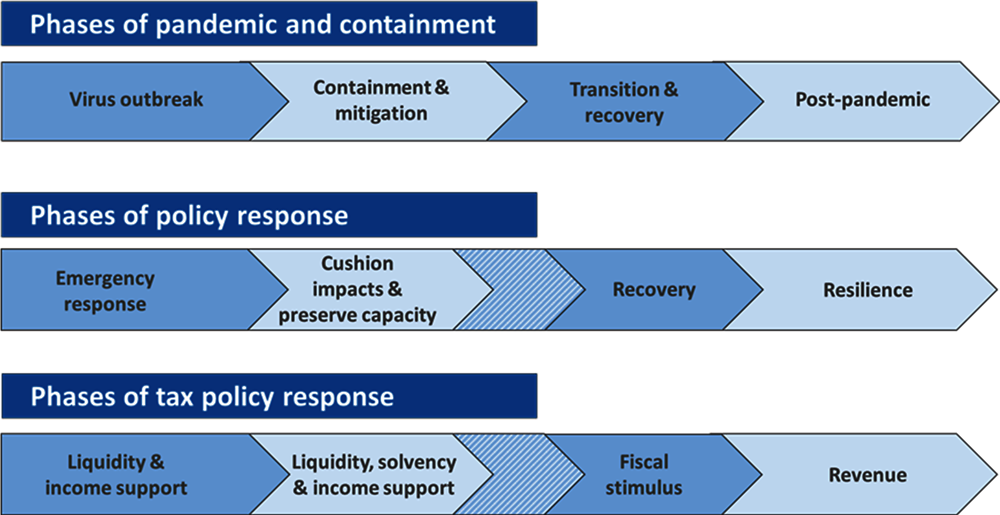

Although uncertainty about the development of the health and economic crisis is high, the crisis can be broken down into different phases, each requiring its own policy responses. While they may overlap and vary across countries, Figure 4.1 presents a schematic view of these different phases and how policy responses may be expected to evolve. In the initial phase (Phase 1), countries confronted with a virus outbreak have implemented containment and mitigation measures, where the aim has been to halt the outbreak. In this phase, tax and broader fiscal policies have tended to focus on liquidity and income support. As the health crisis continues and containment measures remain in place, tax and fiscal measures may evolve gradually into a more sustained effort to reduce the adverse impacts of containment (Phase 2).

The focus of tax and fiscal policies have shifted where containment measures have been gradually removed. As countries have begun to relax containment and mitigation measures, the focus on keeping businesses and households afloat and on limiting hardship has begun to shift towards an emphasis on economic recovery, including through fiscal stimulus policies (Phase 3). However, the progression towards recovery may not be linear. There may be some overlap with Phase 2, where containment and mitigation measures are only being removed gradually or partially. There also remains the possibility of containment measures being reinstated to respond to a second wave of the pandemic. Where this occurs, it will present policy makers with complex fiscal policy challenges given the need to limit the economic hardship from containment in conjunction with stimulating recovery. The timing of repayments or delayed payments linked to the liquidity support measures introduced in Phases 1 and 2 will also be critical and should not compromise firms’ ability to recover. Once economies have recovered, a shift towards restoring public finances can be anticipated, during which there may be renewed attention on strengthening resilience to health risks but also to other known risks, including climate change and declining biodiversity (Phase 4).

As the epicentre of the pandemic has shifted between regions, countries have moved at different paces through containment and recovery phases. The outbreak that began in China in late 2019 first spread to neighbouring Asian countries in January 2020. As the epicentre of the virus shifted to Western Europe during the months of March and April, a number of Asian countries were able to carefully ease containment measures. In an effort to flatten the pandemic curve, European countries entered into lockdowns, which they started cautiously easing in May and June. By this time, the epicentre of the virus had shifted to the United States and a number of middle-income countries, which have also taken steps to slow down the spread of the virus. In early June, a number of the countries that were easing lockdowns and gradually removing containment measures announced stimulus packages to help businesses and households recover from the crisis.

Countries initially focused on emergency responses to the crisis

The first measures introduced by countries focused on cushioning the immediate impact of the crisis. The fiscal packages have had very similar objectives across countries: cushioning households and businesses from the impact of the containment measures and ensuring that households and businesses are able to resume economic activity when the worst of the health crisis has passed. For businesses, this has generally meant providing liquidity support to help them stay afloat. For individuals, the priority has been to provide income support to the most directly affected households. A number of countries have also introduced measures to enhance the funding and functioning of the healthcare sector. These rapid responses may sometimes have been introduced based on the assumption that containment phases would be shorter than what has proved to be the case. Most of the measures introduced in the emergency phase have taken effect immediately and have been time-bound.

In that sense, initial response packages have differed from traditional fiscal stimulus measures. A traditional fiscal stimulus package to boost the economy by encouraging investment and consumption would have been ineffective while containment measures were in place, given the policy restrictions imposed upon economic activity, and could have even encouraged the spread of the virus in some countries where social distancing measures or lockdowns may have been harder to implement.

Countries have strengthened support packages as the crisis has continued

As the crisis has continued, countries have retained their focus on keeping businesses and households afloat and have often expanded their initial packages of measures. Some countries have prolonged existing crisis measures and expanded support to groups that were not covered by the initial measures. The majority of extended and expanded tax measures for businesses have included deferrals for tax filing and payment. Household support has remained centred on expanded access to social security benefits and job retention schemes. These measures, which are relatively simple to expand once implemented, have proven effective at maintaining liquidity for businesses and households.

A few countries have also clarified eligibility for emergency measures, halted tax audit activity, and delayed tax reforms. For instance, Canada has clarified who is eligible for the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS). Several countries have halted tax debt recovery and audit activity for all but high-risk cases (e.g. Canada, the United Kingdom). Some countries have also decided to wind back or delay tax reforms, in particular with a view to easing the tax burden on businesses (e.g. Poland). The United States temporarily relaxed certain provisions put in place by the Tax Cuts and Job Act, including the Section 163(j) interest expense deduction limitation and the net operating losses taxable income limitation.

Some countries have made government support conditional upon certain criteria, to address longer term issues. Several countries, including Belgium, Denmark, France, and Poland, have denied assistance or restricted the types of support available to companies that are registered in non-cooperative tax jurisdictions. Several countries have also seen the potential to address climate and sustainability goals in their pandemic response and recovery. For example, Canadian companies receiving government support have been asked to commit to future climate disclosures and environmental sustainability goals.

Discussions have begun on stimulus packages to support recovery

Recent announcements and discussions suggest that the recovery phase will be supported by expansionary fiscal policy. Discussions have begun both in countries that are removing containment measures and in countries that are still in mitigation and containment phases. Most countries have signalled that government stimulus will be a key pillar of a recovery effort that aims to be inclusive and sustainable. This includes measures to support investment and consumption and ongoing support for households and businesses.

New tax policy issues will emerge in the post-pandemic era, including the need for resilience and restoring public finances

Uncertainty around the health and economic crises remains high, but new questions are already arising. As countries enter the early stages of recovery, several have signalled a desire to strengthen their ability to absorb or respond to future shocks. This may include, but is not limited to, strengthening capacity in the healthcare sector, providing greater social protection to non-standard workers, and enhancing the resilience of supply chains.

Tax policy will also be an important part of countries’ strategies to restore public finances in a fair and sustainable way after the crisis. Countries are expected to explore a wide range of options, including revamping old tools and introducing new ones. This may include efforts to address the international tax challenges posed by the digitalisation of the economy (Pillar 1) and to introduce a minimum corporate tax (Pillar 2) (see section 3.2), to enhance the progressivity of tax systems, and to strengthen the role of carbon taxation. Some countries have already announced their intention to pursue new sources of revenue, including through schemes that price carbon. The unprecedented nature of the crisis has also prompted reflection on exceptional tax measures, as has been the case after major events in the past, like wars and economic crises (Landais, Saez and Zucman, 2020[2]).

Across countries, the types and size of fiscal packages have differed, but most have been comprehensive and significant

There have been similarities as well as differences between fiscal packages across countries. The measures introduced to support businesses have been similar across countries, with a strong focus on tax payment deferrals and other measures that support business cash flow. The introduction or expansion of job retention schemes and other employment support measures has also been common. There have been more significant differences across measures to support households. For instance, many European countries and the United States have extended support for families with children and expanded income support by enhancing eligibility and access to paid-sick leave and unemployment benefits, including for non-standard workers. The United States also provided direct cash transfers to low and middle-income households. In emerging economies, social assistance measures such as cash transfers to low-income households, informal workers, and beneficiaries of social benefits have been more common than social insurance or job retention schemes. A number of emerging countries have also introduced tax payment deferrals and tax waivers, particularly for SMEs.

Different factors may explain the differences in policy responses across countries. Differences in the scope, size, and type of responses across countries are due partly to available fiscal space, the existence of automatic stabilisers and the characteristics of the welfare system, as well as administrative capacity. The characteristics of country responses also relate to the severity of the containment and mitigation measures implemented by countries, which have varied from strict lockdowns to lighter measures focused on social distancing.

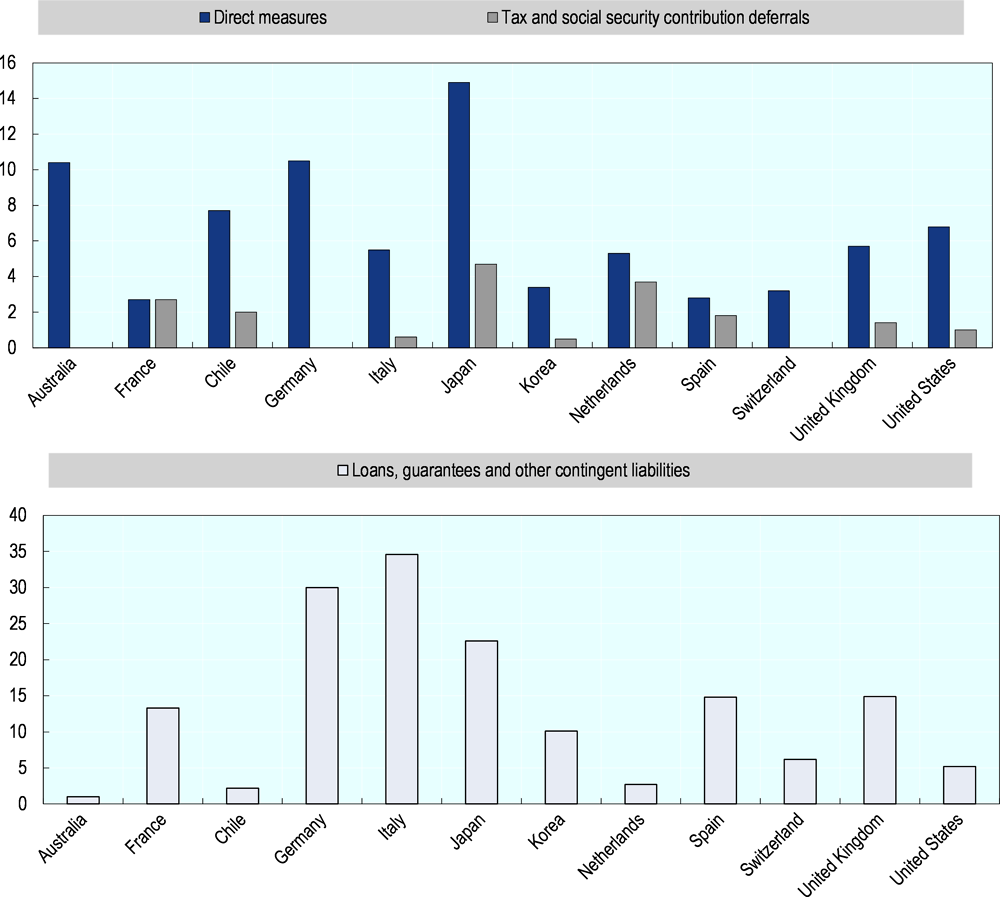

There have been large variations in the size of fiscal packages, but some countries have taken unprecedented action. The size of fiscal packages has varied across countries. Figure 4.2 shows that particularly significant packages have been introduced in Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States. It should be noted that these estimates focus on the revenue costs of the short-term relief measures, and do not take into account the lower revenues that will be collected from taxes as a result of the crisis, nor the costs of subsequent support packages and the expected fiscal stimulus measures during the recovery phase.

The budget effects of different types of measures have also varied widely. For instance, some measures involve permanent losses, even if only for one year (e.g. job retention schemes). Other measures will likely have a temporary impact on budget balances (e.g. deferrals, filing extensions) as deferred taxes should be expected to be paid later on. Finally, state loans and loan guarantees, which appear to have been among the most significant measures in fiscal packages, do not represent a direct fiscal cost. However, they create contingent liabilities which, in some cases, could turn into actual expenses either in 2020 or later.

Most countries have implemented successive fiscal packages, as the scale of efforts required to combat the crisis has become clearer. Initial support packages were implemented at a time when uncertainty about the development of the pandemic and the duration of the efforts needed to contain and mitigate the virus was large. As mentioned above, as the crisis has continued, many countries have expanded the size and scope of their fiscal packages. An escalating policy response has necessarily been accompanied by rising costs. In some cases, however, lower-than-expected numbers of claimants have resulted in lower costs. For example, Australia’s short-time work scheme will cost less than forecast, as fewer businesses claimed the support than projected.2

The main priority for countries has been to support business cash flow

The majority of measures in OECD and partner economies have sought to ensure that businesses have sufficient cash flow. Many businesses experienced a sharp decline in liquidity during the immediate virus response, particularly in countries that imposed a lockdown, and their ability to return to pre-crisis activity has been limited by physical distancing measures that are a core part of safely reopening economies. The decline in liquidity has hindered businesses’ ability to pay for wages, rents, intermediate goods, interest on debt, and taxes. Measures have therefore focused on alleviating cash flow difficulties at each stage of the pandemic response, to help avoid escalating problems such as the laying-off of workers, the temporary inability to pay suppliers or creditors, and, in the worst cases, closure or bankruptcy. Cash flow issues can also cause the failure of connected businesses through a domino effect and could ultimately impact countries’ abilities to recover from the pandemic. Overall, around half of the measures reported by countries in the emergency response phase have been aimed at enhancing business cash flow.

Liquidity support has been provided through a mix of tax and non-tax measures. The most common non-tax instrument used by OECD and partner economies throughout the crisis has been loan guarantee schemes, where the government guarantees all or part of the value of loans granted to eligible businesses. Other measures have included small interest-free loans and cash grants, typically targeted toward small businesses or businesses in the most affected sectors. Other non-tax measures have included the deferral of payments of wage and non-wage business costs such as rent or interest (e.g. the Slovak Republic, Sweden, and the United States). A number of governments have required that companies receiving support and major banks refrain from paying dividends, undertaking share buy-backs or paying bonuses to senior staff.

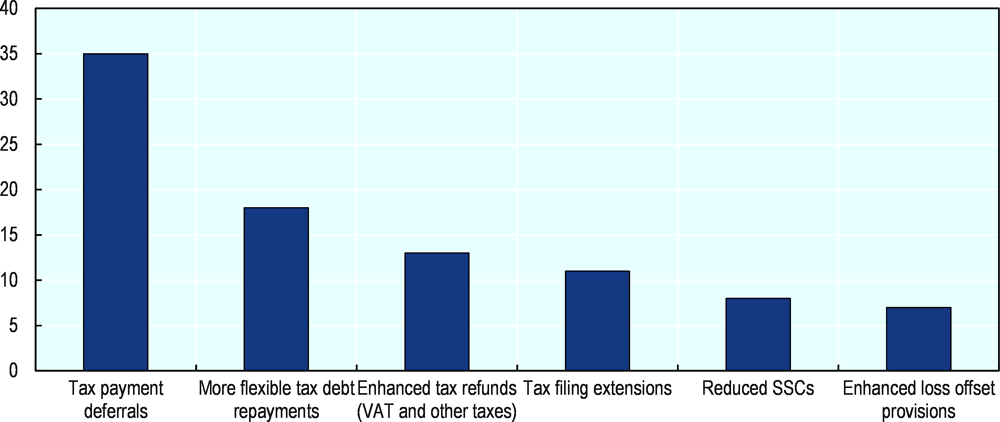

The most common type of tax measure to enhance business cash flow has been the deferral of tax payments (Figure 4.3). Over three quarters of OECD and partner economies have introduced deferrals of tax payments. These measures have generally applied to taxes that require frequent (monthly or quarterly) payments, including advance payments of corporate income tax (CIT) or personal income tax (PIT), value added tax (VAT) and social security contributions (SSCs). In some cases, the tax liability has been calculated based on present revenue estimates, rather than relying on tax returns from previous years that could have led to overpayment (e.g. Spain). There are also a number of cases where property tax payments have been deferred. During the first stage of the pandemic response, around a third of countries also introduced measures to provide business taxpayers with additional time to file tax returns. Additional time to file tax returns may be particularly helpful where taxpayers require the assistance of intermediaries or specialised staff and systems to file returns.

Other administrative measures have been introduced. A common measure, introduced in a third of countries, has been the acceleration of tax refunds (VAT and other taxes) where taxpayers are owed money (e.g. Colombia). A few countries have halted audit activity for all but high-risk cases and around half of the countries have introduced more flexible tax debt repayment plans. Less common measures have included lifting the threshold for access to VAT simplification (e.g. Korea) and increasing the threshold for income tax prepayments (e.g. New Zealand).

Changes to loss-offset provisions have been another important tax policy tool. Some countries have introduced or have announced measures allowing loss carry-back for the 2020 tax year, which will allow taxpayers to carry back their 2020 tax losses against profits earned in previous fiscal years (the Czech Republic, Norway, Poland, and the United States). Other countries have increased the loss-carry forward period for losses incurred in 2020 (China, the Slovak Republic).

Some countries have introduced tax cuts for businesses. These measures have typically focused on tax categories where the tax base does not necessarily vary with the immediate economic cycle (e.g. property taxes) and where, in the absence of tax cuts, the outcomes could be unduly punitive for businesses facing sharp losses in revenue. About one fifth of countries have introduced a waiver or reduction of employer SSCs (e.g. Greece, Hungary, Spain), in some cases restricted to sectors or businesses affected by the crisis. Other examples have been waivers of property taxes and presumptive taxes for small businesses. A few countries have also waived specific levies on tourism and airline companies, and some have reduced or exempted inputs used in certain sectors (including tourism and manufacturing) from import taxes. Other measures to reduce the tax burden on companies have included a tax credit for workshops and shops in Italy amounting to 60% of rental fees related to the month of March, April and May 2020.

The process for obtaining relief and the degree of policy targeting have varied across countries. In some countries, measures have been made available automatically to all firms (e.g. Israel). In other countries, the measures are granted to specific sectors (e.g. tourism, commercial air travel). Some countries have required businesses to apply for relief and to prove to the tax authority that they have experienced a significant drop in revenues or have a reasonable justification (e.g. Finland). Instead of targeting the sectors or businesses that have been most affected by COVID-19, some countries have targeted small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) or self-employed businesses as it is expected that these businesses will face higher liquidity constraints than others.

As the crisis has continued, countries have expanded initial emergency measures and introduced new measures for businesses, some of which have been targeted at specific sectors. To deliver more support during the ongoing crisis, some countries have expanded eligibility to a wider group of companies including larger businesses, allowing a larger portion of taxes to be deferred, and permitting more categories of taxes to be deferred. For example, the United Kingdom has expanded tax deferrals to include import duties and South Africa has doubled the turnover threshold for a Pay As You Earn (PAYE) deferral, so that larger businesses are eligible for the tax relief. Countries have also extended the roll-back date of emergency policies and the due date for deferred tax filing and payment. For example, Italy initially extended some tax payment dates to June, but has since pushed this back to September and Austria has automatically extended tax deferrals for businesses to January 2021. Among the new measures for businesses are policies targeted at sectors that have been badly impacted by the crisis, such as the tourism and hospitality sectors, airlines, and extractive industries. These targeted measures include tax filing and payment deferrals but also sector-specific measures like higher limits for tax-free meal vouchers in restaurants (Austria), payroll support for air carriers and contractors (United States), and tax credits for providers of vacation accommodation when low-income families holiday with them (Italy). Non-tax measures have included loan programmes targeted at large businesses who are big employers (e.g. Canada, the United Kingdom), or small businesses, to provide pay check protection and enhance liquidity (United States).

The protracted crisis and prolonged liquidity shortages could lead to solvency risks, which a few countries have already moved to address. The nature of the risks caused by the pandemic are evolving due to the ongoing nature of the crisis. In addition to collapsing revenues, the pandemic has led to growing debts, both loans and deferred taxes, which may create problems for firms’ solvency. As with liquidity constraints, insolvency could affect not just individual firms but also connected businesses through a flow-on effect. Some countries have shifted support to addressing business solvency challenges. In their second support package, the Netherlands allowed companies to create a “corona reserve” and deduct their expected losses in 2020 against profits made in 2019. Under normal rules, companies would be able to carry back their 2020 losses to 2019, but only after the 2020 tax return is filed, in early 2021. Belgium will support companies rebuilding the equity lost during the crisis by allowing them to allocate part of their profits to a tax-exempt “reserve fund for equity reconstruction”, capped at the size of losses in 2020 or EUR 20 million.

Some countries have delayed tax reforms that were due to be implemented. This has included delaying the implementation of e-filing, the introduction of new taxes and changes to existing taxes. For example, small retailers in Italy have until next year to begin reporting their daily sales electronically and Poland pushed back an excise tax increase on novelty tobacco products and liquids used in electronic cigarettes and the collection of its retail sales tax.

In contrast, some countries have implemented new taxes to fund the pandemic response effort. These typically target large businesses that are expected to fare well during the pandemic due to sustained demand for their products. For example, Hungary has introduced a levy on large retail firms and Indonesia will tax the value added on digital products sold by foreign platform services with a significant economic presence in the country.

As countries have started easing restrictions, measures to support economic recovery and investment have been announced and introduced. In the early stages of the health crisis and during confinement periods, a few measures to support investment were introduced. For instance, temporary increases in thresholds for asset write-offs were introduced in Australia and New Zealand, Italy introduced a corporate tax credit for sanitation costs in workplaces, and Norway accelerated deductions for investments in the oil industry for investments decided by the end of 2021. As countries have started easing restrictions, a few countries have announced new measures to encourage investment and boost economic recovery. For instance, Denmark will temporarily increase R&D tax credits in 2020 and 2021. Some countries are also encouraging or directly funding environmentally sustainable investments. For instance, Denmark has announced plans to frontload energy renovation of social housing and France has announced funding for local investment in construction projects that support environmental transition. France and Germany have announced generous subsidies for purchases of electric vehicles. In Chile, a national agreement between the government and political parties has led to a new emergency plan to support economic recovery for the forthcoming two years. The plan includes a reduction in the SME CIT rate from 25% to 12.5% for years 2020 to 2022, a transitory immediate expensing regime applicable to the whole territory for investments in new or imported fixed assets acquired between 1 June 2020 and December 31 2022, the payment by the Treasury of the new one-time contribution on investment projects (see section 3.3.9), the accelerated refund of accumulated VAT credits for SMEs, the immediate amortisation of investments in certain intangibles acquired between 1 June 2020 and 31 December 2022, a hiring tax credit, and the extension of the suspension of monthly advance CIT payments.

Many countries have introduced measures to help businesses keep their workers

Among OECD and partner economies, many countries have introduced, extended or expanded eligibility for job retention schemes. A major concern throughout the crisis has been the threat of considerable job losses. Many countries have been helping businesses retain their workers by introducing or enhancing the generosity and availability of job retention schemes (OECD, 2020[3]), which proved successful in reducing job losses during the global financial crisis (Hijzen and Venn, 2011[4]). These measures typically provide public income support to workers whose working hours have been reduced or who are temporarily not working because of the crisis, but where firms maintain their connection with the employee. This is intended to allow employers to hold on to workers’ talent and experience and enable them to quickly ramp up production once economic conditions improve. The generosity and duration of job retention schemes varies widely across countries. Many European countries have particularly generous, ongoing schemes, while schemes in some Anglo-Saxon countries are set to expire after several months. Job retention schemes typically cover a certain percentage of wages, are often capped, and have strict rules around businesses’ use of workers during this time.

Some countries have encouraged labour retention by expanding unemployment benefits to those who are still employed but may be working reduced hours. On the condition that employees remain employed by their employers, firms in Iceland and the Netherlands, for example, can request unemployment benefits for their workers. Like job retention schemes, expanding unemployment benefits to employees that are not working but that remain employed by their employees allows firms and workers to maintain contact throughout the crisis.

As is the case for liquidity support measures, in some countries, these measures have been broadly applied, while in others they have been more targeted. In a number of countries, the measures have been targeted at small employers (e.g. Canada). In other countries, these measures have been targeted at the most-affected businesses (e.g. Lithuania, Sweden).

Job retention schemes and other employment support measures have been far less common in emerging market economies. This may be related to these schemes’ high cost and administrative complexity. However, there have been some exceptions: in South Africa, for instance, an existing tax credit allowing businesses hiring young workers to reduce the amount of Pay-As-Your-Earn (PAYE) tax payable, has been expanded to include all workers below 65 and conditions for accessing the scheme have been relaxed.

Job retention schemes have been maintained or extended during the ongoing crisis and some countries have begun adjusting the schemes for the recovery period. Several countries that introduced job retention schemes during the initial phase of the crisis have extended the date that the scheme was due to be rolled back (e.g. Italy, the United Kingdom). Countries that already had job retention or partial unemployment schemes have maintained expanded access, which in some cases includes self-employed workers (e.g. Belgium, the United Kingdom). Countries looking to the recovery period have announced adjustments to short-time work schemes. In some cases, rules guiding businesses’ use of workers have been loosened, allowing businesses to gradually bring their workers back without losing the full wage subsidy. For example, the United Kingdom will allow furloughed workers to return to work part-time from July, with firms paying the hours worked and the job retention scheme covering the remaining hours.

Measures to enhance households’ cash flow

A number of countries have introduced measures to enhance households’ cash flow. Several countries have extended tax filing deadlines, tax payment deferrals or extended payment plans for households unable to make their tax payments. These measures are provided mostly for personal income taxes (PIT), but in some countries have involved property taxes. In some cases, tax payment deferral measures are targeted at low-income households or property below a certain value (e.g. Chile). Other tax measures have included accelerated refunding of excess payments from PIT, and flexible arrangements for tax debt repayments (sometimes targeted at low-income households). Non-tax measures have included the early release of superannuation in Australia and the deferral of interest payments on mortgage debt for primary residences (e.g. Spain). Some deferrals for tax filing and payment have been extended as the crisis has continued, but tax deferrals have remained less common at the household level than at the business level.

Most income support for households has taken the form of increased cash benefits for households directly affected by the crisis

Most countries have introduced measures to provide income support to households, generally through enhanced cash benefits targeted at the most vulnerable households. Many OECD and partner economies have social protection systems in place that provide income replacement for households affected by sickness or job loss. These systems cushion income losses for many workers and act as automatic stabilisers. Given the severe nature of the crisis, many countries have taken steps to expand these systems, to cover groups of individuals that were not covered previously (independent workers, families with unexpected caring needs including parents that had to stay at home to take care of their children because of school closure), to simplify access, and to increase levels of protection.

Support to households has largely been provided through direct transfers rather than through the tax system. While the choice between providing income support through direct cash transfers or through the tax system will typically depend upon the architecture of each country’s tax and transfer systems, most countries rely primarily on transfers to redistribute income. Given the immediate need to provide financial support to the most vulnerable households in the crisis, transfers have generally been preferred as payments can be made more quickly and are often easier to target.

The households targeted and the design of tax and transfer measures have varied across countries. In some countries, cash transfers have been specifically targeted to those households that have been directly affected by the virus (e.g. sick workers) or its immediate economic consequences (e.g. temporarily unemployed workers). Countries have also introduced measures for certain workers, for example, a PIT exemption for overtime workers in critical sectors (Belgium). Some measures have specifically provided support to the self-employed (e.g. Italy, Lithuania, and the United Kingdom). Other countries have provided cash payments to low- and middle-income households more broadly, as these may be the most severely affected by the crisis and will likely have less savings to draw from to support themselves. Chile has introduced a cash bonus for people without formal work, which is expected to benefit two million people, and the United States has provided a broadly based cash payment to work-eligible U.S. residents, in the amount of USD 1 200 for singles, USD 2 400 for married couples, and USD 500 per dependent, which is phased out at higher income levels. Some benefits have also been aimed at families (e.g. Slovenia). In some cases, benefits have been provided as one-off payments, while in other cases they have been provided as temporary increases in regular benefits. New Zealand made a temporary change to its in-work tax credit by removing the hours’ threshold, so that workers who see their hours in work reduced below the hours’ threshold will still be able to claim the payment. Australia has added a temporary coronavirus supplement to some social benefits, including unemployment benefits.

In emerging market economies, some countries have reported cash transfers for households including individuals who operate in the informal economy. Some have been targeted at households directly affected by the pandemic (e.g. Argentina) and at vulnerable households via existing social programmes (e.g. Indonesia).

Most ongoing payments implemented in the emergency phase are yet to expire, but some countries that made one-off emergency payments have provided additional support. During the initial phase of the crisis, several countries implemented special benefit payments or supplements to existing benefit payments. As these programmes were implemented for a period of months, many will still be available during the transition and early recovery phase. For example, the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) will be available until October 2020. Other programmes have been extended, such as the Pandemic Unemployment Payment (PUB) in Ireland. Due to the lengthening crisis, some countries that opted for cash payments have extended these benefits to provide even more support. For example, Poland initially provided a one-off cash benefit to self-employed workers who had experienced a decrease in turnover, but later increased this to three payments.

While a few countries implemented measures to guarantee the affordability of consumer goods during confinement, measures to support consumption may become more common during the recovery phase. In the early stages of the crisis, support for consumption had the potential to undermine the health objectives of confinement, so very few temporary reductions in VAT rates were implemented (e.g. China, Norway). Other tax measures have included the doubling of the tax deduction rate for personal credit and debit card spending in Korea. Emerging countries have favoured non-tax measures to support affordability, such as preventing unjustified price hikes and ‘panic buying’ (e.g. Argentina, South Africa). Measures to encourage consumption may gain greater momentum as countries ease confinement restrictions. Several countries have announced (mostly) temporary reductions in consumption taxes, including VAT, to stimulate consumption. For example, Austria, Germany and the United Kingdom have introduced temporary VAT rate cuts set to expire at the end of 2020 or the beginning of 2021. While Germany temporarily lowered its standard and reduced VAT rates, Austria and the United Kingdom have targeted their VAT rate reductions, particularly towards the hospitality sector and cultural activities.

Many countries have expanded access to paid sick leave and unemployment benefits

Around a quarter of OECD and partner economies have expanded sick leave benefits. Some countries have introduced less restrictive access conditions, such as eliminating or reducing the waiting period before becoming eligible to receive benefits (e.g. Canada, Ireland, Sweden), or removing the need for medical certificates (e.g. from the 8th day of illness in Sweden). Eligibility has also been expanded in a few countries, including to self-employed workers (e.g. Finland, Ireland) and employees who self-isolate (e.g. Latvia, some states in the United States) (OECD, 2020[3]). Some measures have been targeted to specific sectors where many workers are self-employed or informal and lacking social insurance, such as domestic workers. In some countries, governments have covered a larger portion of benefits, reducing the burden on employers, who usually cover the initial period of sick leave. For example, in Slovenia, sick pay for all workers will be covered by the state, not the employer, from the first day of sick leave. Where there are no generally applicable obligations for employers to provide sick leave, new requirements have in some cases been imposed on employers. For example, in United States, public agencies, and small and mid-sized private sector firms (with some exceptions) are temporarily required to provide employees with paid sick leave or expanded family or medical leave for specific reasons related to COVID-19. The federal government has provided employers and the self-employed with refundable tax credits to offset the cost of providing this leave.

More than a third of OECD and partner economies have expanded the coverage of unemployment benefits. A common measure in response to the crisis has been to expand the coverage of unemployment benefits to self-employed workers. Workers in non-standard forms of employment (e.g. temporary, part-time or self-employment) are often significantly less well protected against the risk of job or income loss than workers in standard forms of employment. Some countries have also expanded unemployment benefits to workers in quarantine (e.g. Canada, Switzerland). Many countries were already exploring how to shore up access to out-of-work benefits for non-standard workers before the crisis, and many have done so on a temporary basis in response to the crisis.

On the other hand, emerging market economies outside of the OECD have not reported any expansions in sick leave or unemployment benefits. This may be explained by the fact that these countries tend to have less well-developed social protection systems and primarily rely on cash transfers to provide income support to households.

Enhancements to benefits that were implemented during the emergency phase are still available in many countries, while some measures have been extended and some new measures introduced. Countries that broadened availability of unemployment benefits and sick leave during the emergency phase of the crisis typically implemented these measures for several months. In many cases, these measures will still be in place during the transition and early recovery period, though several countries have publicly discussed ending or gradually withdrawing this support. For example, New Zealand announced a permanent increase in benefit payments in April and Australia will continue paying the coronavirus supplement to unemployed workers until September. The roll-back date of some measures has been extended, such as the sickness benefit for the care of children and the disabled in Lithuania. The scope of some measures has been expanded during the ongoing crisis, including the Temporary Employer and Employee Relief Scheme (TERS) in South Africa, previously restricted to employees that had contributed to the unemployment insurance scheme, but since expanded to all workers affected by the lockdown.

Beyond measures to mitigate the impact of the crisis, countries have adopted responses to strengthen patient care and reduce the pressure on healthcare systems (OECD, 2020[1]). Several OECD and partner economies have introduced measures to facilitate imports of medical inputs to combat COVID-19. A common measure has been the temporary removal of import duties on medicines and health devices and equipment (e.g. Colombia). These exemptions have often been accompanied by measures to simplify and expedite customs clearance procedures.

Some OECD and partner economies have also provided preferential tax treatment to stimulate health-related spending and investment, including measures to safeguard the deduction of input VAT on items donated by businesses (e.g. Belgium, China, Slovenia), to avoid a donation triggering any VAT or income tax liability, and the full or increased deductibility for CIT and PIT purposes of donations made by enterprises or households to healthcare institutions (e.g. Belgium, China, Italy). China has also introduced specific CIT incentives for enterprises engaged in producing key supplies related to COVID-19 protection and containment. This includes 100% expensing for investment in equipment to expand production capacity. In contrast to standard tax rules, there is no limit to the scale of the investment such that larger scale investments also benefit from immediate expensing. China has also introduced PIT exemptions for bonuses and subsidies paid to medical staff working in combatting COVID-19. The United States has issued a technical amendment that enables businesses, especially in the hospital industry, to write off immediately costs associated with improving facilities.

Measures to support the healthcare sector have been common in emerging market countries. Most of the measures have consisted in removing or lowering import duties and other taxes on medical equipment. Additional measures have included a reduction of the bank debt tax for companies that provide healthcare-related services (Argentina) and a higher tax-deductible limit for donations to the Solidarity Fund (South Africa).

A few countries have announced investment and funding packages for the healthcare sector, as part of measures to strengthen resilience. For example, Germany has announced a stimulus package that includes investments in health, accompanied by measures to allow for a swift investment of these funds by fast-tracking projects and simplifying of public procurement law. The United States has provided funds for hospitals to prepare for and respond to the coronavirus, and funds for expenses to research, develop and expand capacity for COVID-19 tests.

Overall, this Special Feature has shown that countries have acted decisively to support businesses, households, and the healthcare sector during this crisis. In addition to enacting measures to contain and mitigate the spread of COVID-19, countries have focused on alleviating hardship and preserving the productive capacity of the economy. Although the severity and duration of the health crisis and the accompanying drop in economic activity remain highly uncertain, countries can now draw on several months of experience of delivering support in unprecedented times.

The OECD will keep monitoring countries’ responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Monitoring tax policy measures is crucial to informing tax policy discussions and assisting governments in their response to the crisis. Regularly updating the OECD database of COVID-19 tax measures and providing timely information on the measures that countries introduce as they move into new phases of the crisis is all the more important given the high degree of uncertainty and the need for agile and rapid policy response.

References

[4] Hijzen, A. and D. Venn (2011), “The Role of Short-Time Work Schemes during the 2008-09 Recession”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 115, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kgkd0bbwvxp-en.

[2] Landais, C., E. Saez and G. Zucman (2020), A progressive European wealth tax to fund the European COVID response | VOX, CEPR Policy Portal, https://voxeu.org/article/progressive-european-wealth-tax-fund-european-covid-response (accessed on 21 July 2020).

[3] OECD (2020), Supporting people and companies to deal with the COVID-19 virus - OECD, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=119_119686-962r78x4do&title=Supporting_people_and_companies_to_deal_with_the_Covid-19_virus (accessed on 24 June 2020).

[1] OECD (2020), Tax and fiscal policy in response to the Coronavirus crisis: Strengthening confidence and resilience, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/tax-and-fiscal-policy-in-response-to-the-coronavirus-crisis-strengthening-confidence-and-resilience-60f640a8/ (accessed on 24 June 2020).

Notes

← 1. The information has been collected through delegates from the Inclusive Framework on BEPS and delegates to Working Party No.2 on Tax Policy and Statistics and WP2 No.9 on Consumption Taxes of the Committee of Fiscal Affairs. The OECD Centre for Tax Policy and Administration will continue to update the database regularly.

← 2. https://www.ato.gov.au/Media-centre/Media-releases/Joint-Treasury-and-ATO-statement---JobKeeper-update/