Chapter 6. Access to skills

Skilled workers are a key asset for competition in a knowledge-based economy. However, SMEs have greater difficulty in hiring and retaining skilled workers than larger firms because they lack the capacity and networks needed to identify talent and offer less attractive working conditions. Rapid digital transformation, growing globalisation and emerging skills shortages worldwide are likely to put further pressure on labour markets and increase the competition for skills, placing SMEs at an even greater disadvantage. This chapter presents recent labour market trends and discusses the implications for SMEs with respect to their access to skilled workers. It reveals that, although SMEs are reducing the training gap with large firms, relatively few SMEs support the acquisition of digital skills. Moreover, there appear to be persistent gender gaps among entrepreneurs and small business owners in entrepreneurship attitudes and access to training. The chapter also discusses recent national policy actions that improve the capacity of SMEs to upskill their workers, e.g. training and education programmes, technology extension programmes, regulatory measures that encourage upskilling, tailored support for women entrepreneurs and business owners.

-

Employment rates across OECD countries have increased for three consecutive years and SMEs face skilled labour shortages. SMEs appear to have difficulties attracting and retaining employees with management, communication or problem-solving skills, which are crucial for innovation.

-

SMEs are increasingly engaging with continuous vocational and education training programmes and catching up to large firms in the proportion that offer these opportunities to employees. Yet, there is a lack of ICT training in the workplace, which is of particular concern in light of adult skills gaps and urgent retraining needs, including to harness the digital transformation.

-

The under-representation of women among entrepreneurs and business owners is in part linked to skills. More needs to be done to help women harness the opportunities created by the digital economy, including in acquiring ICT skills, Science Technology Engineering and Math (STEM) skills, management and communication skills, and entrepreneurship skills.

-

Policy makers continue to use a mix of instruments to urge SMEs to offer upskilling opportunities for their employees. This includes measures that reduce training costs and strengthening linkages between SMEs and training providers. There is a growing focus on strengthening management skills, developing entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, and offering tailored training and support for female entrepreneurs and business owners.

Why is it important?

Skilled workers are a key asset for competition in a knowledge-based economy (Autor, 2013[1]; Grundke et al., 2017[2]). Skills development has therefore become critical in a context of a fast and irreversible digital transition and growing globalisation.

Highly skilled employees have an important role in firms because they are more likely to be involved in performing complex tasks that help drive firm competitiveness and productivity growth (Acemoglu, 2002[3]). This is confirmed by empirical studies that point to a mutually reinforcing relationship between workforce skills, and innovation and productivity (OECD, 2018[4]). Skilled employees are also vital for enhancing technology and innovation absorption, as well as breaking into new markets.

Skilled workers typically have strong cognitive (e.g. literacy, numeracy and problem solving), management and communications skills, and a readiness to learn. ICT skills are of particular relevance for making use of emerging digital technologies, such as cloud computing, the Internet of things or big data (OECD, 2017[5]). However, firms also need workers with strong social and emotional skills (e.g. communication, self-organisational skills) that complement cognitive skills. Successful employers also need employees with entrepreneurial skills and mindsets to help firms identify, create and act upon opportunities, and adapt to change (OECD, 2018[6]).

The benefits for SMEs of upskilling their workforce can be extensive. In addition to helping to close the productivity gap with large firms, improving the skills of workers can also strengthen the position of SMEs in global value chains (GVCs) by helping them specialise in high value-added activities (e.g. technologically-advanced industries, complex business services) and integrate themselves into higher value-added segments of GVCs (OECD, 2017[7]). Skilled employees are also valuable for SMEs managing organisational change encountered during company transitions such as growth or exporting for the first time (OECD, 2015[8]).

However, SMEs typically have greater difficulty in attracting and retaining skilled employees than large firms because they tend to lack the capacity and networks needed to identify and accessing talent. More importantly, they tend to offer less attractive remuneration and working conditions compared to larger firms (Eurofound, 2016[9]) and therefore have difficulty competing for highly skilled workers. Recent results from the OECD/Facebook/World Bank Future Business Survey show that as many as one-third of SMEs report that recruiting and retaining skilled employees is the most pressing challenges for their business (Facebook/OECD/World Bank, 2018[10]).

Moreover, this challenge appears to be increasing. Results from the Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE) by the European Central Bank and the European Commission show that 24% of surveyed SMEs in the Euro area reported that “labour availability of skilled staff or experienced managers” was the most important problem faced in 2017 (European Commission/European Central Bank, 2018[11]). This was nearly double the proportion that reported this as the most important problem in 2011 (13%).

SMEs also offer fewer opportunities for employee development and skills acquisition. Employees in small firms are 50% less likely to be offered formal training than those in larger firms (OECD, 2013[12]), which is often due to the lack of dedicated internal training or Human Resources departments to organise and co-ordinate training. Moreover, SMEs tend to have lower levels of management skills and practices, which hampers the utilisation and development of skills within SMEs (OECD, 2015[13]). Thus, even when skills are increased they may not be used effectively.

In addition, direct financial costs for developing tailored training are relatively higher for SMEs than for large firms because large firms can distribute the fixed training costs over a larger group of employees. It must also be recognised that the opportunity cost of training is often greater in SMEs as they have fewer employees, leaving less scope to release people from revenue-generating activities for training.

SMEs also tend to view training differently than large firms. Some SMEs do not consider training to be a value-generating activity, but rather as part of an induction process required by the law, e.g. to familiarise new employees with health and safety requirements (OECD, forthcoming[14]). Furthermore, SMEs tend to experience higher job turnover than larger firms, constraining the capacity and willingness of SMEs to invest in the skills development of their workforces when there is a risk that an upskilled employee will leave shortly after training.

Poorly developed markets for business transfer may also play a role in holding SMEs back in renewing their skills and practices, and this is a growing policy concern in many countries.

Public policy can play a role in addressing these challenges to help boost productivity within SMEs, which would be expected to lead to job creation and growth. One under-exploited area for policy is to tap into the existing but unrealised potential for innovation and growth among certain segments of entrepreneurs and SME owners, e.g. female entrepreneurs and business owners.

It is also important for policy makers to support SMEs in adjusting to changing nature of work. Nearly one in two jobs are likely to be significantly affected by automation: about 14% of workers are at a high risk that their tasks will be automated over the next 15 years, and another 30% will face major changes in the tasks required in their job and, consequently, the skills they would need to do their job. At the same time, new jobs will be created that will likely require workers to use digital technologies and undertake more complex tasks. OECD countries where workers use ICT more intensively at the work are also characterised by a higher share of non-routine jobs (OECD, 2018[15]). This suggests that the skill requirements of many jobs will very likely change in the not-so-distant future and this trend will make training, reskilling and upskilling even more critical for workers, firms (of any size) and policy makers (Frey and Osborne, 2013[16]; Nedelkoska and Quintini, 2018[17]).

Skills, labour markets and emerging trends

There are signs of continued skilled labour shortages in SMEs

Labour market participation has been increasing in the OECD area in recent years, signalling an ongoing recovery from the global financial crisis and a return of discouraged jobseekers to the labour market. The share of the population aged 15 to 64 years old who were employed reached 68.5% in Q4 2018, above the business-cycle peak in Q4 2007 (also 66.5%) just before the crisis. Labour markets are expected to continue to tighten over the next two years but employment growth is still expected (OECD, 2018[18]). Although, recent job creation has been largely driven by SMEs, especially new enterprises, most of the new jobs in many countries have been created in low productivity sectors where skills requirements are also lower (see Chapter 1 on recent trends in SME sector and performance). The tightening labour market is likely to increase the competition for skills, which may have a disproportionate impact on the ability of SMEs to attract skilled workers.

This pressure is likely to increase on SMEs in the future given the rate of population aging, which is expected to increase competition for workers.

OECD work also shows that transversal skills are a key component of the skills mix that is needed at the worker, firm and country level to harness increased globalisation, to seize the benefits but also to face the potential negative impacts of increased global competition and fragmentation of production (OECD, 2017[5]). This increases the demand for workers who have not only strong cognitive skills (including literacy, numeracy and problem solving) but also management and communication skills, and a readiness to learn (OECD, 2018[15]). Acquiring these skills is particularly important for workers in SMEs, where employees are called on to perform a variety of tasks in a less structured fashion than in large firms.

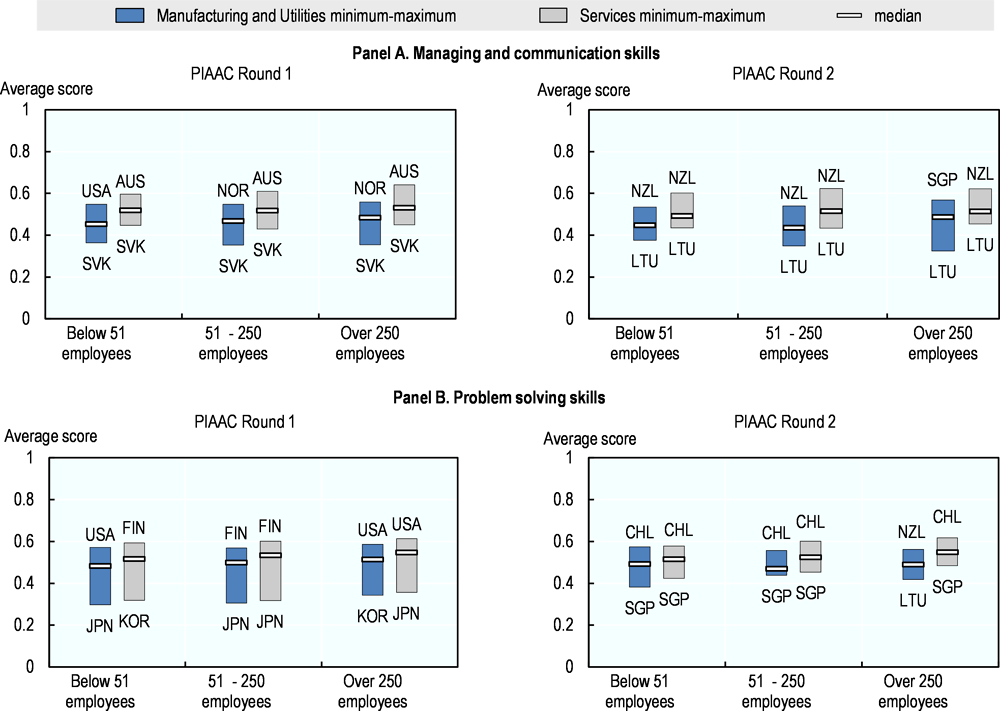

Evidence suggests that employees in SMEs are less likely to have innovation-related transversal skills than those working in large firms. For example, results from the OECD Survey on Adult Skills (PIAAC) show that workers in large firms have higher scores on questions related to management and communication skills (Figure 6.1, Panel A), and problem solving capacity (Figure 6.1, Panel B). While the maximum and minimum of test scores are approximately the same across all firm sizes, the median scores increases by firm size. Thus, SMEs appear to be just as likely as large employers to have employees that have very high and very low scores. However, on average scores appear to be higher in large employers.

Employees in service sector firms have higher scores relative to those in manufacturing and utilities sections, both in terms of the maximum and minimum scores as well as the median score. A similar firm-size pattern is observed in both sectors. Moreover, little difference in results is observed between the two time periods of the survey, i.e. Round 1 (2008-12) and Round 2 (2012-16).

SMEs continue to offer fewer opportunities to upskill but are closing the gap with large firms

In most OECD countries, the majority of SMEs offered continuing vocational education and training (CVET)1 to their employees in 2015 (Figure 6.2). Nonetheless, the proportion of employers that offer CVET increased with firm size.

However, there appears to be a growing number of small and medium-sized employers that offer CVET. While the proportion of all firms offering CVET increased between 2010 and 2015 in nearly all countries, the gains observed among small and medium-sized employers are relatively greater so the gap between small and large firms appears to be narrowing.

Within SMEs, CVET courses were the most frequently offered type of training in 2010 and 2015. External courses were offered more frequently than internal courses. Other common approaches included guided-on-the-job training; training at conferences, workshops, trade fairs and lectures; and self-directed learning.

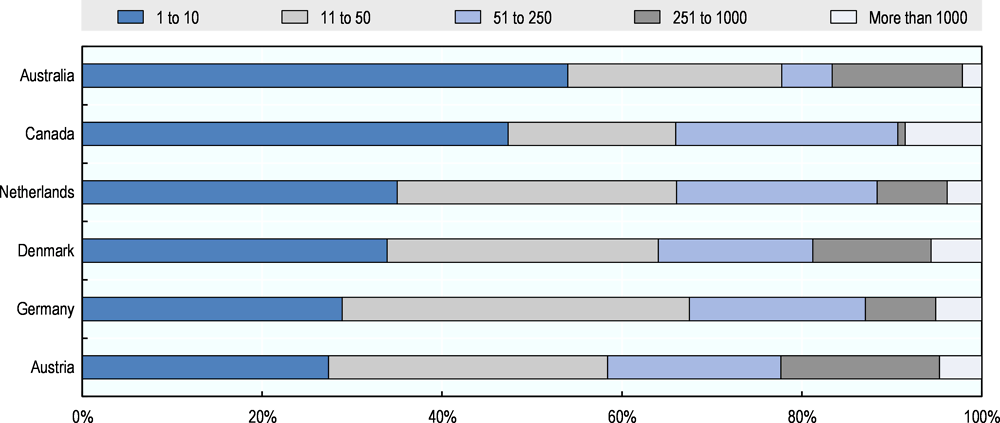

Many OECD countries are examining the role of apprenticeship programmes as a means of better linking the education system to the world of work. Apprenticeship programmes combine both school-based education and the on-the job training and result in a formal qualification or certificate (OECD/ILO, 2017[21]). Many SMEs use apprenticeship programmes because of their benefit in stimulating company productivity and profitability. In countries for which data are available, more than 50% of all apprentices work in companies with 50 employees or fewer (see Figure 6.3). Apprenticeships are more common in manufacturing, construction and engineering sectors, where employers (and often unions) are well represented and organised (Kuczera, 2017[22]).

The proliferation of ICT offers growing opportunities for SMEs to further close the training gap with large firms. Online training platforms decrease the costs of delivering training. These approaches typically use a modular approach, which increases the flexibly for employers and employees to manage the time needed for training with work responsibilities.

Few SMEs support the acquisition of digital skills

The level of ICT skills in the workforce has a strong relevance in the context of the general trend towards job automation which, with the advent of robotics, machine learning algorithms and artificial intelligence, is becoming increasingly pervasive both in manufacturing and in services.

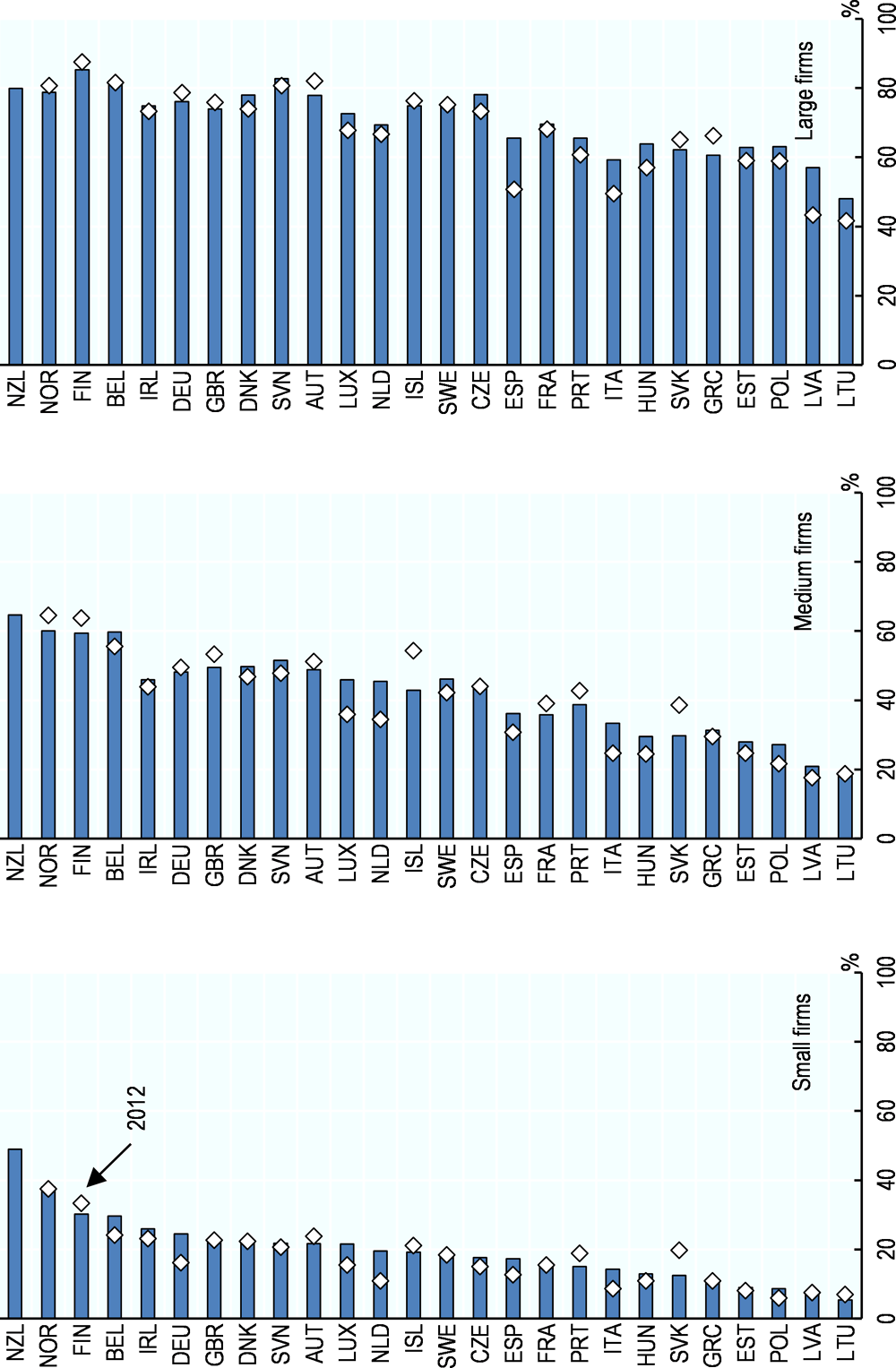

Results from the OECD Survey on Adult Skills (PIAAC) reveal that two-thirds of adults in the OECD area lack core ICT skills to succeed in technology-rich environment. Thus, strengthening of the provision of digital training in SMEs appears to be crucial but there are wide cross-country differences in firms’ participation in ICT training (Figure 6.4). Whereas 48.9% of firms in New Zealand with fewer than 50 employees trained their employees in 2017 with a view to developing their ICT-related skills, only 6.7% of small firms in Latvia did. While a similar pattern is also observed in medium-sized and large firms, the relative gap between the high and low performers decreases as firm size increases.

Nevertheless, the proportion of businesses supplying ICT training has not increased substantially since 2012. This observation holds across all firm size classes (Figure 6.4). Belgium, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands and Spain are the few countries where small firms have engaged more actively in training their employees in 2018 than they did in 2012. The share of medium-sized firms providing ICT training also slightly increased in Belgium, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland and Spain over the period. But changes remain limited overall and the situation has even worsened in Finland, Portugal and the Slovak Republic for all SMEs, and in Norway and the UK for medium-sized firms.

There appears to be a correlation between the offer of ICT training and the adoption of digital technologies. European countries where firms more actively offer ICT training show higher business adoption rates of cloud computing (CC) (Figure 6.5).2 Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden lead the ranking while SME digital transformation appears less advanced in Southern and Central European countries. The same data show greater country dispersion in the uptake of CC among small firms than medium-sized firms, and conversely greater country dispersion in training practices among medium-sized firms than small firms. Furthermore, firms in countries with higher adult digital literacy tend to invest more in ICT training and have higher CC adoption.

Female entrepreneurs and business owners have great potential but face barriers to acquiring skills

The formal education levels attained by women, on average, increasingly exceed those of men. However, women still tend to have less experience in self-employment (Marlow and Carter, 2004[26]; Collins-Dodd, Gordon and Smart, 2004[27]) and continue to have fewer opportunities than men in management positions, which acts as a barrier to gaining management experience and skills that can be used in entrepreneurship (Boden Jr. and Nucci, 2000[28]).

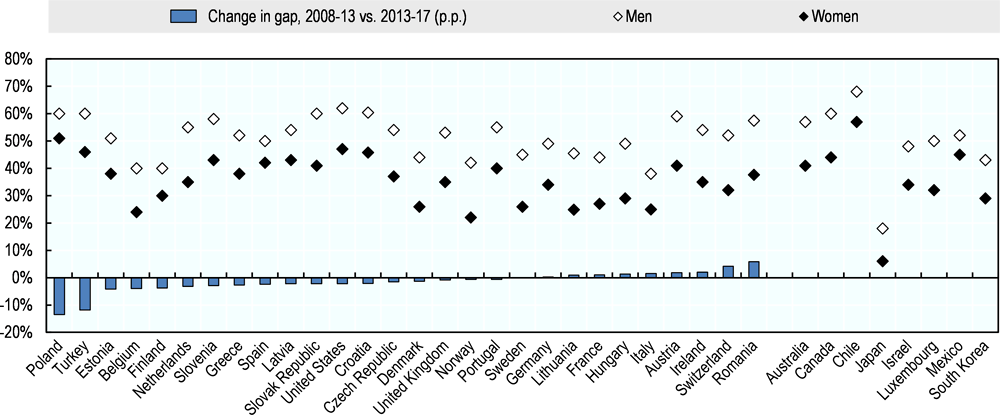

Women are also less likely than men to feel that they have the skills, knowledge and experience to start a business. Across OECD countries, 37% of women indicated that they had sufficient skills, knowledge and experience to start a business over the 2013-17 period. However, more than half of men did (51%) and this gender gap holds across all OECD countries (OECD/EU, 2017[29]). Relative to the 2008-13 period, the gender gap has closed slightly in most countries, notably in Poland (9 percentage points) and Turkey (12 p.p.) (Figure 6.6). The gender gap only increased slightly in Switzerland (4 p.p.) and Romania (6 p.p.), driven by more improved perceptions in the male population.

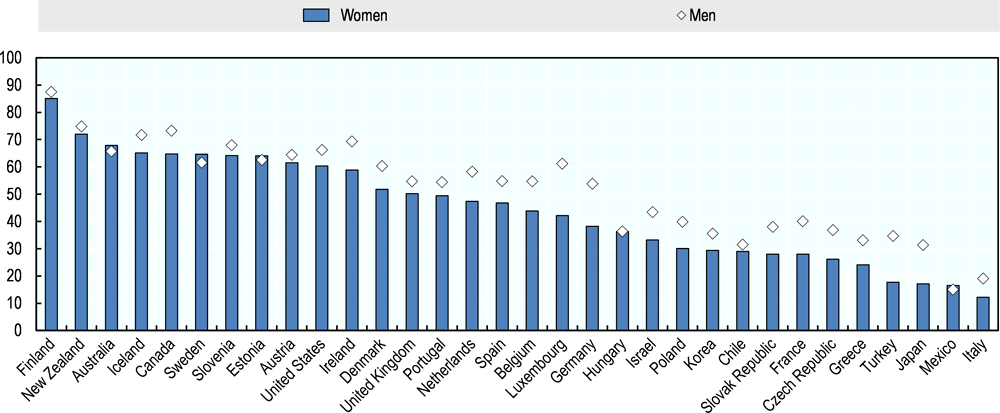

Moreover, women are less likely than men across OECD countries to report that they have access to training on starting and growing a business (OECD, 2016[31]). Figure 6.7 confirms that in all but three OECD countries (Australia, Sweden and Mexico), women were less likely to have access to entrepreneurship training in 2013. This gap can be explained by several factors, including low levels of awareness of available support, unappealing training programmes (i.e. the content is less relevant for the types of businesses that women operate), selection bias in programme in-take, or issues of accessibility (e.g. childcare services are not offered as part of the support programme).

There are substantial economic gains to be realised from female participation in the labour market, entrepreneurship and business ownership. For example, estimates suggest that cutting the gap in labour market participation in half by 2025 would result baseline GDP growth by 2.5 percentage points per year (OECD, 2017[33]).

Main policy approaches and recent policy developments

Engaging SMEs in training and education

There are several types of policy initiatives that can be deployed to support the development of workforce skills in SMEs (OECD, 2012[34]), mainly focusing on reducing training costs for firms and promoting the benefits of workplace training (Table 6.1).

Many OECD countries offer tax incentives to reduce the cost firms incur for training their employees. Training costs can be, partially or fully, deductible from annual corporate profits in the form of tax exemptions. Such schemes may specifically target smaller firms by offering them enhanced deductions.

Smaller firms are also frequently targeted by direct training subsidies schemes. Training vouchers, for example, help SMEs purchase training hours from accredited individuals or institutions.

In addition, countries aim to raise awareness of the importance of training and skills development in SMEs through various channels, including public and stakeholder organisations.

An option for awareness raising is to leverage local employer networks to promote skills upgrading in the workplace. Employer networks and associations can also foster trust-based relationships between firms that support knowledge-sharing and pooled investments in training. Collaborations across firms can also foster innovative diffusion within regional supply chains, potentially integrating firms into GVCs, which also reduces regional vulnerability to automation (OECD, 2018[35]).

Countries are also investing more in “brokers” or intermediator bodies such as group or collective training offices to organise training for groups of SMEs to shift the burden away from individual employers. These organisations often sign apprenticeship contracts with government while also providing pastoral care and practical assistance to individual apprentices. They are particularly useful for SMEs who would not otherwise be able to meet the national minimum standards for training apprentices and upholding apprenticeship training quality standards.

Regulation can also encourage skills development. Some countries have introduced statutory rights for employees for training leave. However, their take-up is generally not high (less than 2% of employees benefitting from the measure).

Using technology extension policies and programmes to provide tailored support to SMEs

Government-funded technology extension programmes seek to expand the absorption and adaptation of existing technologies (e.g. equipment, new managerial skills) in firms, and to increase their absorptive capacity. While this type of support is not new, the use of technology extension programmes that are targeted at SMEs has expanded over the last decade (Shapira, Youtie and Kay, 2011[36]).

Technology extension programmes typically start with an assessment of the firm’s operations and processes, followed by a proposed plan for improvement and implementation assistance. Key services include information provisions (e.g. opportunities to improve use of existing technologies, trends, best practices); benchmarking to identify areas for improvements; technical assistance and consulting; and training.

Technology extension services are often offered by networks of technical specialists (e.g. engineers) who proactively reach out to firms to organise visits and consultations. However, firms can also reach out for assistance to technology extension programmes.

This type of support is typically offered individually to interested firms, but may also be provided simultaneously to groups of firms with common needs. The first stages of review and diagnosis are generally free of charge, while more intensive projects often require co-financing by the firm, although at lower than market prices for consulting services (Table 6.2).

Strengthening management skills in SMEs

Governments have several tools at their disposal to help build management skills in SMEs, ranging from the provision of digital diagnostic tools to help SMEs identify their management deficiencies, training and workshops, and more intensive approaches such as management coaching. Most programmes and initiatives tend to cover business strategy; operating models; process management; performance management; leadership; governance; agility; and innovation (Table 6.2).

One of the greatest challenges for governments is to create a demand for existing support services since many programmes have low take-up rates due to a lack of awareness of existing programmes; legitimacy issues around public support operators; doubts on the usefulness of the advice; and limited ambitions for business development and growth.

Some countries also combine management training and consulting with support in ICT adoption and use. This approach can help stimulate innovation and boost productivity (OECD, 2016[37]).

An important component of management skills is financial planning and management. The need to enhance financial skills and strategic vision of entrepreneurs and small business owners is recognised in the G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Finance. This includes the ability to conduct financial and risk planning, keep track of financial transactions, respond to disclosure requirements and provide relevant financial information in start-ups’ business plans and SME investment projects (G20/OECD, 2015[38]).

Creating an adaptive and entrepreneurial workforce

Many OECD countries have recently developed strategies, programmes and initiatives to develop transversal skills that allow individuals to be creative, take initiative, act as problem-solvers, effectively manage resources, and build financial and technological knowledge. Initiatives include entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship training programmes, as well as workplace training on innovation and change management. These competencies enable entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial employees to provoke and adapt to change and are thus crucial for innovation and business growth in SMEs.

Building entrepreneurship skills and entrepreneurial mindsets has become a central mission of education policies. In many OECD countries, schools, vocational education and training (VET) institutions and higher education institutions (HEIs) have been enriching their study programmes with education activities to develop entrepreneurship competencies, either as self-standing modules or embedded into curricula. Developing countries are also becoming more active in this policy area (Table 6.3).

Tapping into the potential of women entrepreneurs and business owners

Traditional policy supports for women’s entrepreneurship have included women’s enterprise centres, tailored entrepreneurship training programmes, loan guarantees and microcredit. In recent years, new approaches have been implemented to stimulate growth aspirations among women entrepreneurs and help them acquire the tools needed to seize the benefits of the digital transformation, including tailored entrepreneurship training for women operating in the digital economy and greater use of women-dedicated business incubators and accelerators.

Women entrepreneurs need to acquire the skills demanded by the digital era, including ICT skills, numeracy and STEM-quantitative skills, as well as self-organisation and management and communication skills (OECD/EU, 2017[29]) (Table 6.3). While the gender gap in the use of software at work is small in most OECD countries, men are more likely to be working in the platform economy and are four times more likely than women to be ICT specialists (OECD, 2017[40]). Smart education policies can help ensure women benefit from digital technologies in the workplace, and as entrepreneurs. In addition, national connectivity policies can enable women access to and use of new technologies.

A growing number of countries are setting up women-dedicated business incubators to help them start quality businesses with growth potential (Table 6.3). Although they account for fewer than 3% of incubators globally, international evidence shows that women-only incubators are more effective than mainstream incubators that rely on male-centric networks and have male-dominated selection panels (OECD/EU, 2017[29]).

-

Institutional and regulatory framework: e.g. competition for enabling an optimal reallocation of resources including skills, taxation of labour and wages, especially of the highly skilled, tax exemptions on hiring highly skilled, etc.;

-

Market conditions: e.g. integration into GVCs and knowledge transfer and staff mobility within the value chain; access to public procurement and lead markets, etc.;

-

Infrastructure: e.g. broad and equitable access to high speed broadband and affordable ICT services;

-

Access to finance: e.g. loans and subsidies for retraining, mentorship and training services provided as a complement of financial support, etc.;

-

Access to innovation assets: e.g. collaborative open innovation networks, transfer of data and knowledge, learning-by-doing innovative approaches, etc.

References

[3] Acemoglu, D. (2002), “Technical change, inequality, and the labor market”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 40.1, pp. 7-72.

[1] Autor, D. (2013), “The ‘task approach’ to labour markets: An overview”, Journal of Labour Market Research, Vol. 46/3, pp. 3-30.

[28] Boden Jr., R. and A. Nucci (2000), “On the survival prospects of men’s and women’s new business ventures”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 15/4, pp. 347-362.

[27] Collins-Dodd, C., I. Gordon and C. Smart (2004), “Further evidence on the role of gender in financial performance”, Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 42/4, pp. 395-417.

[9] Eurofound (2016), Sixth European Working Conditions Survey – Overview Report, https://doi.org/eurofound.link/ef1634.

[11] European Commission/European Central Bank (2018), Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises in the euro area: October 2017 to March 2018, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/ecb.accesstofinancesmallmediumsizedenterprises201806.en.pdf?f710aadd09e7d0036678df8612df9104.

[20] Eurostat (2018), Continuing Vocational Training Survey, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/education-and-training/data/database.

[10] Facebook/OECD/World Bank (2018), Future of Business Survey, https://eu.futureofbusinesssurvey.org/manager/storyboard/RHViewStoryBoard.aspx?RId=%c2%b3&RLId=%c2%b3&PId=%c2%b1%c2%ba%c2%b4%c2%ba%c2%bd&UId=%c2%b5%c2%b6%c2%b3%c2%b3%c2%b9&RpId=3&slide=0 (accessed on 31 May 2018).

[16] Frey, C. and M. Osborne (2013), “The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation”, Oxford Martin School Working Paper, https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/publications/view/1314.

[38] G20/OECD (2015), High-Level Principles on SME Financing, http://www.oecd.org/finance/G20-OECD-High-Level-%20Principles-on-SME-Financing.pdf.

[30] GEM (2018), Special Tabulations of the 2013-17 Adult Population Survey, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor.

[2] Grundke, R. et al. (2017), “Skills and global value chains: A characterisation”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2017/05, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cdb5de9b-en.

[22] Kuczera, M. (2017), “Striking the right balance: Costs and benefits of apprenticeship”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 153, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/995fff01-en.

[26] Marlow, S. and S. Carter (2004), “Accounting for change: Professional status, gender disadvantage and self-employment”, Women in Management Review, Vol. 19/1, pp. 5-16.

[17] Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), “Automation, skills use and training”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers 202.

[24] OECD (2019), ICT Access and usage by Businesses Database, OECD, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/58897a61-en.

[6] OECD (2018), “Developing entrepreneurship competencies”, http://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/ministerial/documents/2018-SME-Ministerial-Conference-Parallel-Session-3.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2018).

[4] OECD (2018), Enhancing Productivity in SMEs, OECD, Paris.

[32] OECD (2018), “Entrepreneurship: Access to training and money to start a business, by sex”, OECD Gender Portal, OECD, Paris.

[15] OECD (2018), Job Creation and Local Economic Development 2018: Preparing for the Future of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264305342-en.

[18] OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2018 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_outlook-v2018-2-en.

[35] OECD (2018), Productivity and Jobs in a Globalised World: (How) Can All Regions Benefit?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264293137-en.

[40] OECD (2017), Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/entrepreneur_aag-2017-en.

[23] OECD (2017), ICT Access and Usage by Businesses Database, OECD, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/58897a61-en.

[7] OECD (2017), OECD Skills Outlook 2017: Skills and Global Value Chains, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273351-en.

[25] OECD (2017), OECD STI Scoreboard 2017, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/sti/scoreboard.htm.

[5] OECD (2017), The Next Production Revolution: Implications for Governments and Business, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264271036-en.

[33] OECD (2017), The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264281318-en.

[31] OECD (2016), Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/entrepreneur_aag-2016-en.

[37] OECD (2016), Increasing Productivity in Small Traditional Enterprises: Programmes for Upgrading Managerial Skills and Practice, OECD, Paris.

[19] OECD (2016), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Database 2012, 2015), OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/publicdataandanalysis/.

[13] OECD (2015), “Skills and learning strategies for innovation in SMEs”.

[8] OECD (2015), The Innovation Imperative: Contributing to Productivity, Growth and Well-Being, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264239814-en.

[12] OECD (2013), Skills Development and Training in SMEs, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264169425-en.

[34] OECD (2012), Upgrading Workforce Skills in Small Businesses: International Review of Policy and Experience, OECD LEED Programme, Paris.

[14] OECD (forthcoming), Enhancing Productivity in SMEs, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[29] OECD/EU (2017), The Missing Entrepreneurs 2017: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264283602-en.

[21] OECD/ILO (2017), Engaging Employers in Apprenticeship Opportunities: Making It Happen Locally, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264266681-en.

[36] Shapira, P., J. Youtie and L. Kay (2011), “Building capabilities for innovation in SMEs: A cross-country comparison of technology extension policies and programmes”, International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development , Vol. 3, pp. 254-272.

[39] UNIDO (2017), Youth in Productive Activities.

Notes

← 1. CVET includes training in the form of courses, but also activities such as attending conferences, workshops, lectures and seminars; job rotations and secondments; learning and quality circles; self-directed learning; and training at workstations.

← 2. See also the chapter on access to innovation assets for a broader discussion on cloud computing and SME use of new digital technologies.