1. Context and background

This chapter provides information about the two international assessments – the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) – the analysis in this report is based on. It also gives details on the students the two assessments assess, the assessment frameworks, how performance is reported and the background information about students and their schools that each assessment collects.

This report presents analysis of Türkiye’s international assessment data to better understand how students in the country perform throughout schooling. It focuses on student performance in Türkiye as measured by two international assessments – PISA and TIMSS. It aims to understand how student performance has evolved over time and analyse whether factors related to student background – such as gender or socio-economic information – are associated with performance. In particular, through the analysis of PISA and TIMSS data, it seeks to answer the following questions:

How do students in Türkiye perform in the main domains of mathematics, science and reading across schooling, compared to other countries?

How has the student performance in Türkiye changed over time and across different levels of schooling?

Are there certain student characteristics that are associated with lower (or higher) performance in Türkiye? How do these associations change and develop as students progress through school?

How are school-level characteristics and features associated with performance? Do these associations change depending on the level of schooling?

Are there certain domains or aspects of learning in specific domains on which students in Türkiye excel? What are the weaknesses of students in Türkiye across the main domains?

To answer these questions, the report analyses key aspects related to student and school background. Not all of the information collected by both international assessments, such as teaching and learning practices or student well-being, are explored in this report.

Türkiye participates in two international assessments – PISA since 2003 and TIMSS Grade 8 since 1999 and TIMSS Grade 4 since 2007 (Table 1.1). PISA takes place every three years (although the 2021 assessment was pushed back to 2022 because of disruption related to the COVID-pandemic) and covers mathematics, science and reading. TIMSS takes place every four years and covers mathematics and science.

While this report makes observations about student performance in Türkiye across different levels of schooling based on PISA and TIMSS data, the data are not directly comparable because each assessment differs in its design. Most importantly, the assessments assess different knowledge and skills – mastery of an international, school-based curriculum in TIMSS compared with the application of competencies to real-life contexts in PISA. Contextual variables, such as students’ socio-economic status or school resources, also differ.

Both PISA and TIMSS employ rigorous and professionally recognised sampling techniques to ensure that the sample of students selected represents the full target population in the participating countries (15-year-old students in PISA and students enrolled in Grades 4 and 8 in TIMSS) (OECD, 2018[3]; IEA, 2020[4]).

Who is assessed by PISA and TIMSS?

TIMSS, Grade 4

For the Grade 4 assessment, TIMSS assesses students in their fourth year of formal schooling, provided that the mean age of students at the time of testing is at least 9.5 years. Since education systems differ in structure and starting ages, some countries assess students in different grades (Martin, von Davier and Mullis, 2020[5]). In 2019, Türkiye chose to assess students in Grade 5 for the first time to provide a better match between the curricula that students are expected to cover in Türkiye and what is assessed by TIMSS (Table 1.2).1 This meant that students in Türkiye’s sample had an average age of 10.6 years. In previous rounds of TIMSS, Türkiye assessed students in the last grade of primary school, Grade 4, which meant that students in Türkiye’s sample were on average, 9.9 years (Martin, Mullis and Hooper, 2016[6]). In this report, the terminology of “TIMSS, Grade 4” is used throughout since this is the official name of the assessment. However, the data from 2019 refer to Grade 5 students in lower secondary education in Türkiye.

In Türkiye, like in all countries, certain categories of students and schools were excluded from the TIMSS assessment. This included students with functional or intellectual disabilities and schools that cater solely to those students, as well as students not proficient in the Turkish language.

TIMSS, Grade 8

For the Grade 8 assessment, TIMSS assesses students in their eighth year of formal schooling, provided the mean age at the time of testing is 13.5 years. In 2019, Türkiye chose to assess students in Grade 8, as in previous years, with a mean age of 13.9 years (Martin, von Davier and Mullis, 2020[5]).

PISA

In contrast to TIMSS, PISA assesses students based on their age, rather than grade. The students assessed by PISA are aged between 15 years 3 months and 16 years 2 months at the time of the assessment, and they have completed at least 6 years of formal schooling. To be eligible for the PISA assessment, students must also be enrolled in at least Grade 7 in an educational institution (OECD, 2019[8]). In Türkiye, most of the students who sit the PISA assessment are in Grade 10, as is the case in the majority of OECD countries. A minority of students in Türkiye were still in Grade 9 when the assessment took place, while an even smaller minority were already in Grade 11 (Table 1.3). These differences might reflect misalignment between PISA testing and cut off dates for entry into formal schooling or grade retention or advancement policies.

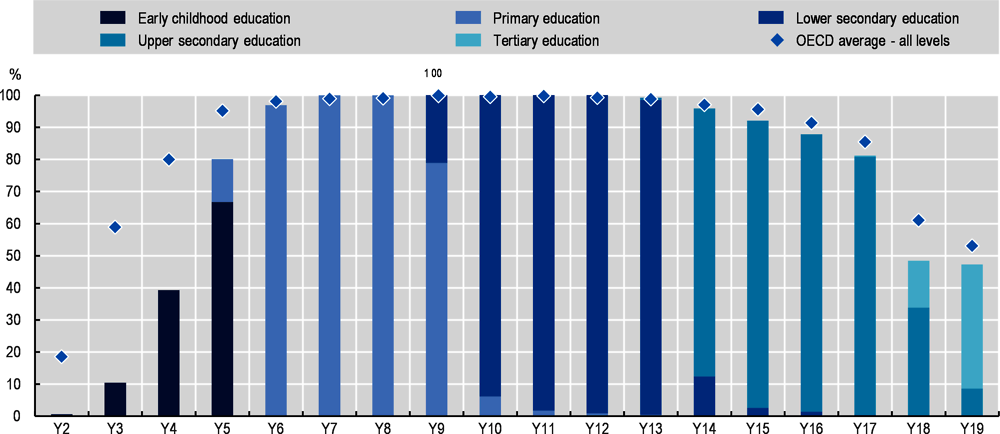

Türkiye’s PISA coverage index in 2018 was 73%. The coverage index is the proportion of 15-year-olds in a country or economy that were covered by the PISA sample (OECD, 2019[8]). Türkiye’s PISA coverage index is almost 20% lower than the share of 15-year-olds who are enrolled in school at this age (Figure 1.1). There are a number of reasons why the PISA coverage index is lower than national enrolment rates. First, because countries may exclude up to 5% of otherwise-eligible 15-year-old students enrolled in Grade 7 or above for various reasons, including the remoteness and inaccessibility of their school, intellectual or physical disability, a lack of proficiency in the test language or a lack of test material in the language of instruction. In 2018, Türkiye excluded 5.66% of students (OECD, 2019[8]), including students with special learning needs and who do not speak Turkish fluently.

Second, the large difference in the PISA coverage index and the share of 15-year-olds enrolled at school according to national and international administrative data in Türkiye is likely explained by students who are enrolled in open high schools.2 In Türkiye, open high schools provide distance learning programmes and offer an alternative for students to complete their compulsory education, such as those who have had to repeat two school years or have been unwell for an extended period (Kitchen et al., 2019[7]). Since PISA only assesses students attending physical schools, those attending open high schools are not covered by the assessment. However, open high schools are included in Türkiye’s school enrolment statistics which explains the discrepancy between the PISA coverage index and enrolment rates in upper secondary education.

Türkiye’s coverage index has increased significantly over PISA cycles (Figure 1.2). However, the country continues to have one of the lowest coverage indices of all OECD countries, after Colombia, Costa Rica and Mexico (OECD, 2019[8]). The low coverage index has important implications for interpretations of Türkiye’s PISA results because it means that the analysis of the PISA results presented in this report does not reflect the full population of 15-year-olds in the country.

Assessment frameworks

The PISA assessment framework

In each round of PISA, three domains are assessed – mathematics, reading and science – one of which is the major domain and focus of each cycle. The major domain rotates with each cycle. In the most recent PISA assessment, 2018, reading was the major domain. The PISA assessments are not designed to examine whether students can reproduce knowledge of a particular curriculum but rather if they can apply the knowledge and skills they have acquired in real-life settings.

The PISA 2018 framework for reading guided the development of the PISA 2018 reading literacy assessment. It conceptualises reading as an activity where the reader interacts with both the text that he or she reads and with the tasks that he or she wants to accomplish during or after reading the text. To be as complete as possible, the assessment covers different types of texts and tasks over a range of difficulty levels (OECD, 2019[8]).

The assessment also requires students to use a variety of processes or different ways in which they cognitively interact with the text. The PISA 2018 framework identifies processes that readers activate when engaging with a piece of text (Table 1.4). Information on the assessment of mathematics and science can be found in the report PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework (OECD, 2019[12]).

The TIMSS assessment framework

The TIMSS assessment frameworks are based on a curriculum model that is updated each cycle by participating countries that review the frameworks describing the mathematics and science content to be assessed and take part in item development (Mullis et al., 2020[13]). The mathematics and science frameworks include content domains, which specify the content to be assessed, and cognitive domains, which specify the thinking processes to be assessed. Within each of these areas, further sub-domains are set out depending on the grade and subject (Table 1.5).

Measuring performance

Performance in PISA

PISA reports performance in various ways. The most straightforward way is through the mean performance of a country’s students. PISA also reports students’ performance in terms of proficiency levels (Table 1.6). Summaries of the proficiency levels in mathematics and science can be found in the OECD report PISA 2018 Results (Volume 1): What Students Know and Can Do (OECD, 2019[8]). The scale summarises both the proficiency of a person in terms of his or her ability and the complexity of an item in terms of its difficulty. Level 2 is usually considered the minimum level of competency that students need for success in life and work, and students who perform below Level 2 are considered “low performers”. In contrast, high performers are defined as students who attain Levels 5 or 6 of proficiency. Türkiye’s average performance and share of students across proficiency levels are discussed in Chapter 2.

Performance in TIMSS

TIMSS also reports average scale scores by country, grade and subject. The TIMSS achievement scale centre point of 500 is located at the mean of the combined achievement distribution (TIMSS 2019).

TIMSS also describes achievement at four points along the scale as international benchmarks (Tables 1.7 and 1.8) Descriptions of benchmarks for mathematics and science for Grade 8 can be found in the report TIMSS 2019 International Results in Mathematics and Science (Mullis et al., 2020[13]). Türkiye’s average performance and share of students across proficiency levels are discussed in Chapter 2.

Background questionnaires

Both PISA and TIMSS include questionnaires that collect information about students’ backgrounds, their schools and learning contexts to understand how these factors are associated with performance. TIMSS collects data on national and community, home, school and classroom contexts through questionnaires that are completed by students, teachers and school principals. For students participating in the Grade 4 assessment, TIMSS also asks parents or caregivers to complete a questionnaire (IEA, 2020[14]). PISA collects contextual information through questionnaires that are distributed to students and school principals. The questionnaire to students asked questions about the students themselves, their attitudes, dispositions and beliefs, their homes and their school and learning experiences. The questionnaire to school principals covered school management and organisation, and the learning environment (OECD, 2019[8]). PISA also has optional questionnaires which countries can distribute if they wish. Data from the optional questionnaires are not analysed in this report.

This report has selected a number of benchmark countries, whose performance is reported alongside Türkiye’s throughout the report. The benchmark countries help to contextualise Türkiye’s performance and provide more specific insights on country-level performance than international averages. The benchmark countries in this report are – Germany, Poland and Russia and were selected in 2020.3

These countries were selected based on similarities with Türkiye in terms of a number of demographics, socio-economic indicators and performance on international assessments (Table 1.9). Their participation in the same cycles of PISA and TIMSS as Türkiye also influenced the choice of benchmark countries (Table 1.10).

References

[4] IEA (2020), Methods and Procedures: TIMSS 2019 Technical Report, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2019/methods/ (accessed on 6 December 2021).

[14] IEA (2020), TIMSS 2019 Context Questionnaires, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2019/questionnaires/index.html (accessed on 25 July 2021).

[1] IEA (2020), TIMSS 2019 International Results in Mathematics and Science, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2019/international-results/ (accessed on 21 May 2021).

[7] Kitchen, H. et al. (2019), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Student Assessment in Turkey, OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5edc0abe-en.

[6] Martin, M., I. Mullis and M. Hooper (eds.) (2016), Methods and Procedures in TIMSS 2015, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/publications/timss/2015-methods.html (accessed on 24 July 2021).

[5] Martin, M., M. von Davier and I. Mullis (eds.) (2020), Methods and Procedures: TIMSS 2019 Technical Report, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education and Human Development, Boston College and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2019/methods/pdf/TIMSS-2019-MP-Technical-Report.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2021).

[13] Mullis, I. et al. (2020), Highlights from TIMSS 2019, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, https://timss2019.org/reports/ (accessed on 24 July 2021).

[10] OECD (2021), “Education Database: Enrolment by age”, OECD Education Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/71c07338-en (accessed on 21 July 2021).

[11] OECD (2021), “Education Database: Population data”, OECD Education Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/ccca3172-en (accessed on 21 July 2021).

[2] OECD (2021), “PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment”, OECD Education Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00365-en (accessed on 21 May 2021).

[17] OECD (2020), Education at a Glance 2020: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en.

[12] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b25efab8-en.

[9] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Online Education Database, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/.

[8] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en.

[3] OECD (2018), PISA 2018 Technical Report, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/pisa2018technicalreport/ (accessed on 6 December 2021).

[20] Turkish Ministry of National Education (2021), National Education Statistics - Formal Education 2020-21, http://sgb.meb.gov.tr/www/icerik_goruntule.php?KNO=424 (accessed on 26 November 2021).

[18] World Bank (2020), GDP Per-capita (current US$) (dataset), World Bank, Washington, DC, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed on 20 July 2021).

[16] World Bank (2020), Population, Total (dataset), World Bank, Washington, DC, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL (accessed on 20 July 2021).

[19] World Bank (2019), Gini Index (World Bank estimate) (dataset), World Bank, Washington, DC, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI (accessed on 20 July 2021).

[15] World Bank (2018), Land Area (sq.km) (dataset), World Bank, Washington, DC, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.TOTL.K2?end=2018&start=2018 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

Notes

← 1. The Ministry of National Education in Türkiye examined the match between the TIMSS evaluation framework and the mathematics and science curricula for Grades 4 and 8 in Türkiye. The match with the Grade 4 science curriculum was low and as a consequence MoNE decided that Grade 5 in Türkiye would participate for the Grade 4 TIMSS assessment in 2019. The change also brought the average age of students in Türkiye’s sample closer to the average age across other countries participating in TIMSS 2019 Grade 4 (10.2 years). Norway and South Africa also chose to participate at Grade 5 for the TIMSS 2019 Grade 4 assessment (IEA, 2020[1]).

← 2. In Türkiye, students can pursue their education through distance learning courses in the open school system. Open schools enable students to continue their education in formal education institutions when they cannot attend a physical high school for various reasons. Reasons for attending an open high school include: being over 18 years which means that students can no longer enrol in physical high schools; students who are required to repeat a grade more than once; students who are expelled from physical high schools; and married students.

← 3. This report was sent for comments to the Education Policy Committee at the OECD between 29 April and 20 May 2022. It should be noted that the Russian Federation no longer participates in the work of the Committee.