copy the linklink copied!5. Case study on Korea

This chapter describes the important role of conglomerates in the Korean economy and capital markets. It notes their vital contribution to Korean economic growth, while also citing concerns related to a range of issues such as risks of unfair intragroup transactions that can impact on investor confidence, requiring governance structures that increase corporate competitiveness while not harming the interests of investors and other stakeholders. It describes the main provisions relevant to the oversight and corporate governance of company groups set out in Korea’s regulation on large business groups, the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act regulation on conglomerates, as well as the Corporate Law. It concludes with a detailed description of relevant proposed legal reforms to the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act aimed at further improving the Korean legal framework for oversight and corporate governance of company groups.

copy the linklink copied!Introduction

Once a war-torn country, the Republic of Korea has now become the seventh member of OECD 30-50 Club,1 the group of economies reaching USD 30 000 in per capita income and 50 million in population. Investors around the world are paying keen attention to the Korean companies that have achieved rapid growth, building a global presence. The remarkable accomplishment, however, has been undervalued for so long because of the “Korea Discount,” which is caused by weak corporate governance at Korean business groups.

Undeniably, large business groups have played a vital role in the nation’s economic growth. Following the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, however, Korea witnessed increased civic awareness and capital market development. Then, a range of issues at business groups such as unfair intragroup transactions, which had hidden under the growth imperative, was revealed.

In Korea, business groups are very common and make up a large portion of the economy. In an ever-changing business environment, a business group should have a governance structure that increases corporate competitiveness and does not harm the interests of investors and other stakeholders.

This paper is intended to highlight the policy measures taken by Korea in a direction towards strengthening the advantages of a business group system and preventing or at least minimising the side effects. Here, the focus lies on the Corporate Law and the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act (“Fair Trade Act”). The former deals with matters about corporate governance, and the latter disciplines the behavior of a business group.

copy the linklink copied!The state of play of business groups

Definition of a business group

Article 2 of the Fair Trade Act defines a business group as a group of companies, the business of which is substantially controlled by the same person,2 who may be a company or a natural person. The law sees that the same person controls a company if he/she and a related party owns a combined shareholding of 30% or more as the largest shareholder or can elect half or more of the directors or the representative director. A company belonging to a business group becomes an affiliate of the other companies under the same business group. According to this definition, all companies financed by investors fall under the category of a business group.

Considering the difficulty of effective enforcement, however, “business groups subject to limitations on cross-shareholding” and “business groups subject to disclosure” are separately designated as “conglomerate”, limiting the regulatory scope. The respective thresholds for the two business group types are KRW10 trillion or more3 and KRW5 trillion or more4 in total assets.

Statistics of business groups5

As of May 2019, the Korea Fair Trade Commission (“KFTC”) designated 59 business groups as a conglomerate, which collectively have 2 103 member firms under them. Among them, 34 business groups with KRW 10 trillion or more in total assets having 1 421 member companies fall under the category of a “business group subject to limitations on cross-shareholding”. Of the 59 conglomerates, a natural person is a controlling shareholder at 51 of them, and a corporate body controls the remaining eight. As at the end of 2018, 25.1% or 196 companies out of the 781 firms listed on the Korea Composite Stock Price Index (KOSPI) market6 belong to a conglomerate. Their combined market capitalisation is around KRW 914 trillion, or 70% of the entire KOSPI market capitalisation.

The controlling shareholder of a business conglomerate has maintained a controlling power by building a complex shareholding structure, including cross-shareholding. More recently, however, the pyramidal ownership structure is more commonly observed. The change was brought about by the policy efforts to convert a business group into a holding company and eliminate circular shareholding. As a result, circular shareholding has shrunk significantly from 282 cross-shareholding loops at ten business groups in May 2017 to 11 at two business groups in July 2019. As of September 2018, 22 conglomerates, about one-third of the total, elected to become a holding company. Including three intermediate holding companies, 24 holding companies belonging to a conglomerate are listed on KOSPI and own 67 subsidiaries and 21 sub-subsidiaries under them.

Regulation on large business groups

The controlling shareholder at a large business group or conglomerate exerts management control over all member companies. In the meantime, due to a complex ownership structure, the direct economic interest the controlling shareholder has at each affiliated firm varies. To take an example of a company at the lower level of the pyramid, the dividend income finally recognised by the controlling shareholder gets far less, undergoing several steps of the ownership hierarchy. It is so even if the company makes a substantial profit and pays out a handsome amount of dividends. This disparity between control and ownership has an impact on decision-making within the business group. In some cases, there may be a decision unfavorable to a particular company, an excellent example of which is unfair intragroup trading.

Korea's antitrust law attempts to tackle the cause of the problem and thereby to prevent the rise of the control-ownership disparity. Specifically, the law prohibits the business groups subject to cross-shareholding from forming circular shareholding and regulates the behavior of a holding company. The code also tries to deter the potential consequences of the control-ownership disparity by prohibiting tunneling such as intra-group trading. The following details the key provisions of the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act that deal with large business groups, holding companies, and their corporate governance:

The Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act—Regulation on conglomerates

When a member company of a conglomerate intends to conduct a transaction exceeding a particular scale with an affiliated company or the controlling shareholder, it shall first call a board meeting for a resolution and disclose the purpose of the transaction, trading party, scale and conditions, among others. The threshold is a quarterly transaction reaching 5% of the larger of the company’s total capital or capital stock, or KRW 5 billion or more (Article 11(2)).

According to the Financial Investment Services and Capital Markets Act, a listed firm shall disclose the status of the shares held by the directors and substantial shareholders and any change thereof. The Fair Trade Act goes further and imposes a duty to disclose the shares held by the largest and substantial shareholders and any change thereof even on a private member company of a large business group with KRW 10 billion or more in total assets (Article 11(3)).

The Fair Trade Act requires a member firm of a large business group to disclose matters regarding the parent group. The disclosure shall include the status of the member companies’ shareholding, their cross/circular shareholding and debt guarantees. It shall further mention whether the business group voted on the shares it acquired or owns in its domestic affiliates (limited to FIs), and transactions with a related party (Article 11(4)).

Concerning the extraction of undue private benefits of control, a member company of a large business group is prohibited from trading with an affiliated firm owned by the controlling shareholder and/or his/her family over a specific ratio7 and from transferring undue profits to them. According to the data provided by the KFTC, as of May 2018, 231 member companies of a business group were subject to the regulation on the extraction of private benefits of control. At these companies, the controlling shareholder and his/her family held an average of 52.4% of shares. The Fair Trade Act provides the following as acts of transferring undue profits to the controlling shareholder (Article 23(2)):

-

a. Making a transaction with the related party or affiliate under terms that are substantially more advantageous than terms that have been applied, or deemed to be applied to a deal between unrelated parties.

-

b. Providing the related party or affiliate with a business opportunity that will bring the company substantial benefits, if it conducts such business directly or through any company controlled by it.

-

c. Making a transaction of cash or any other financial instrument with the related party under substantially advantageous terms.

-

d. Making a transaction of a certain scale with the related party or affiliate without giving due consideration to its business ability, financial standing, credit rating and technical power, the price, terms and conditions of the transaction, etc. or without comparing with other business entities.8

At the same time, the antitrust law exempts the application of the above provisions to the cases of unquestionable efficiency where the concerned affiliate is part of the supply chain, for example. The rules mentioned above neither apply when there is a risk of technology leakage that potentially causes critical security damage if trading with a party outside the group and when there is an emergency need due to external factors such as a financial crisis.

Furthermore, a member company of a business group subject to limitations on cross-shareholding with KRW 10 trillion in total assets shall neither acquire nor hold shares of any affiliate that, in turn, acquires or holds shares of that member company.9 In case a company inevitably acquires or owns the shares of an affiliate and creates a circular shareholding to conclude a corporate merger or exercise a security right, it shall dispose of such shares within six months (Article 9).

A member company of a business group subject to limitations on cross-shareholding shall not have any shareholding in any affiliate that forms any circular shareholding. The foregoing also applies to additional shareholdings in an affiliate that has already formed a circular shareholding.10 Similar to the case of cross-shareholding, if a company has acquired and created a circular shareholding in proportion to the shares involved in a corporate merger or stock transfer, the company shall dispose of the shares within a specified period. Unlike the rule on cross-shareholding, however, the provision governing circular shareholding does not require the elimination of the circular shareholding that had existed before the business group became subject to the regulation (Article 9(2)).

A member company of a business group subject to limitations on cross-shareholding that is engaged in financial business or insurance business shall not exercise its voting rights with respect to the shares acquired or held by it in its domestic affiliates.11 It can still vote at the general meeting of shareholders of a listed affiliate, limited to the election and/or dismissal of directors, the amendment of the articles of incorporation, a corporate merger, and the transfer of business. For this purpose, the member company and a related party’s combined number of shares eligible for voting shall not exceed 15%. If a member company acquires or holds the shares to engage in the finance or insurance business, it can exercise voting rights even at an affiliate (Article 11).

The Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act—Restrictions on behavior of the holding company

In 1986, the government prohibited the holding company system out of the concern that corporates might take advantage of the governance structure to concentrate economic power. In more than ten years, it was reinstated in 1999 for the enhancement of the ownership transparency and management efficiency such as through restructuring, along with a few measures to mitigate the risk of economic power concentration. It lacked, however, the incentives for a conglomerate to convert to a holding company when it already had a controlling power such as through circular shareholding, which led to ongoing deregulation of the holding company system.

According to the existing antitrust provisions, a holding company shall hold a minimum of 40% of the shares of a subsidiary. The threshold is lower at a minimum of 20% if the subsidiary is a listed firm. The same applies to a sub-subsidiary, while a sub-sub-subsidiary shall be entirely owned by a sub-subsidiary. A holding company shall not hold the shares of an affiliate that is not its subsidiary or sub-subsidiary. It shall neither hold any shares of a non-affiliate exceeding 5%. Meanwhile, the Fair Trade Act does not allow a holding company to own a financial institution and a non-financial institution at the same time, to separate financial and industrial capital (Article 8(2)). Of business conglomerates subject to regulations, three are financial holding companies, and 19 are non-financial ones.

Also commonly observed is a business conglomerate that is not a holding company and holds the shares of a financial company, which raised the need for comprehensive supervision of financial conglomerates. Notably, in advanced financial markets, including the EU, discussions are underway on how to supervise financial conglomerates. In the past, Korea witnessed risk contagion to a financial company affiliated with a business group.12 Against this backdrop, the Financial Services Commission and the Financial Supervisory Service published in June 2018 the Guidelines of Best Practices for Supervision of Financial Conglomerates, which is now in the pilot implementation stage.

The Guidelines define that if a business group has two or more financial companies in it, the financial companies collectively form a financial conglomerate. The new supervisory rule applies to the financial companies whose combined aggregate assets amount to KRW 5 trillion or more. The company at the top rank of the financial conglomerate becomes a representative company, which must disclose the matters concerning the financial conglomerate’s ownership/governance structure, group-level risk management system, capital adequacy, related party transactions, and risk concentration, among others. A financial conglomerate that is a member of a business group shall assess and control the contagion risk where the financial or management risk of the industrial companies is transferred to the financial firms due to the issues like credit exposure, related party transactions and corporate governance. A representative company is subject to an annual risk management assessment comprising 18 assessment items under four categories of the risk management system, capital adequacy, related party transaction/risk concentration and governance/conflict of interests. A bill currently pending at the National Assembly captures the points mentioned above.

The Corporate Law

The Corporate Law neither defines a business group nor cites the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act. Instead, the code applies to an individual company. The harmful effects of a large business group such as damage to minority shareholders occur as a consequence of the actions taken by a specific company. In this sense, not only the regulations against business groups but also those against individual companies may prove useful when it comes to rectifying the problems posed by a large business group. The following details specific company-level regulations outlined in the Corporate Law but relevant to corporate governance of a conglomerate:

The controlling shareholder of a business group exerts influence at all member companies even if he/she does not hold a director position at any of them. For this reason, the Corporate Law recognises that a person who is not a director is still liable for damages against the company and/or a third party if he/she exerted influence, and ordered the execution of business activity or executed the same himself/herself. Shareholders are also entitled to the right to file a derivative suit (Article 401(2)).

The Corporate Law stipulates under Article 397-2 that no director shall use business opportunities of the company that are likely to be of present or future benefit to the company, on his/her own account or on the account of a third party, without the approval of the board of directors13. It further requires a board approval when a director, his/her spouse, his/her lineal ascendant or descendant, or a company they own 50% or more of the shares wishes to conduct a transaction with the company. Both cases require two-thirds of affirmative votes from the board (Article 398).

Disclosure by business groups

As mentioned above, a member company of a conglomerate shall disclose the matters about the business group to which it belongs. The disclosure shall include individual member companies’ respective ownership details, cross-shareholdings or transactions between affiliates. Nonetheless, it is not enough to wholly understand the business group as an entity and track any changes. To provide the missing group-level picture, the KFTC has disclosed the ownership landscape, the percentage of shares owned by corporate leaders and related parties, circular shareholding details and governance structure since 2012.

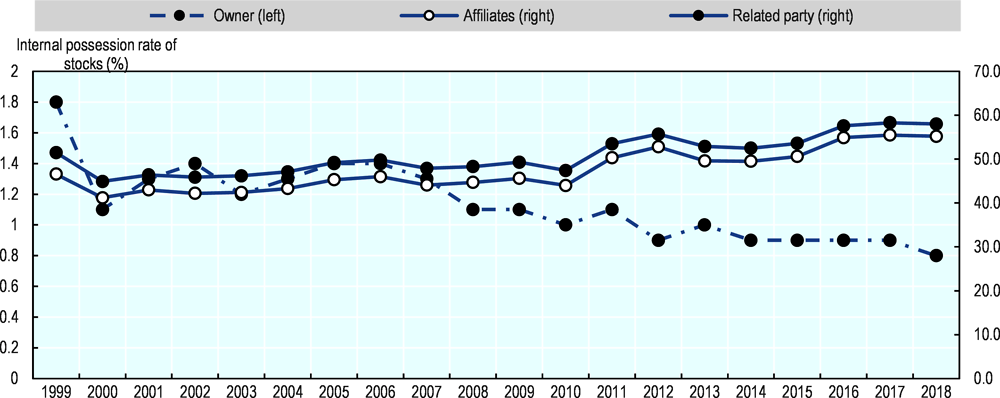

The antitrust watchdog revealed that the shares held by all the related parties14 at the 52 conglomerates controlled by a natural person reached 57.9%, and the shares owned by the natural person and his/her family15 was 4%. Over the last 20 years, the top ten business groups saw the shares owned by their related parties grow while the shares held by the natural person controlling shareholder continued dropping, widening the control-ownership disparity (See Figure 5.1 and Table 5.1).

The KFTC’s report on corporate governance details the portion of the member companies whose controlling shareholder serves as a director, the operation of the board of directors and the tools to protect minority shareholders such as cumulative voting. According to the 2018 report, 21.8% of the member companies had the controlling shareholder or his/her family as a director. In a further breakdown, 46.7% of them were core businesses, 86.4% holding companies and 65.4% subject to the regulation on tunneling. As for the second or third generation of a controlling shareholder, 75.3% of the firms they served as director were subject to the rule on tunneling or out of the law’s boundary.

The report continued that more conglomerates had in place a non-mandatory related-party committee and a compensation committee under the board, but it was questionable whether deliberation got underway faithfully. The KFTC’s report further said that more than 99.5% of the proposals put to the vote at these board committees received support by the directors. 81.7% of the proposals to approve a private agreement with a related-party did not even mention the rationale. Lastly, listed member companies of a conglomerate did not reach the averages of the entire listed companies in terms of the adoption of cumulative voting, written voting and electronic voting.

The KFTC analyses ownership and governance structures that investors find it hard to understand intuitively and provides quality information for them. By doing so, the Commission contributes to increased market scrutiny and incentivises voluntary improvements on the part of large business groups.

Related-party dealings

Transactions between companies under the same business group can raise the competitiveness of the involved companies by acting as a substitute for an external market in the absence of an efficient outside market. At the same time, it may cause an undue wealth transfer from minority shareholders to the controlling shareholder. The Corporate Law has provisions on the use of corporate opportunities and requires board approval before a transaction if the directors and the company have conflicting interests. The rules are directed at preventing potential problems while acknowledging the merit of a related-party deal. The Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act also has provisions that allow related-party dealings for efficiency, security and emergency purposes. The same code sets forth the conditions that constitute a related party transaction involving the taking of private benefits of control and prohibits such transactions. The following is a high-profile example where the involved companies were levied a fine after the provision banning tunneling became effective. The case is now with court over the legitimacy of the fine.

Enforcement of the regulation on extraction of private benefits of control

In 2016, the KFTC fined Company A engaging in the transportation business and its affiliates Company B and C around KRW 1.4 billion, saying that the transactions between the three companies provided unjust benefit for the controlling shareholder and his family. The Commission also brought charges against the CEO/president of Company C named D, who is a child of the concerned business group’s controlling shareholder.

The children of Company A’s controlling shareholder wholly owned Company B, which engages in in-flight duty-free sales. The regulator saw that Company A did not receive a sales commission from Company B without a proper agreement and thereby transferred undue profits to the controlling shareholder and his family. The children of the controlling shareholder had the most shares of Company C as well, whose revenues mainly came from the operation of a call center on behalf of Company A. Since a telecommunications service provider invested in and offered Company C system equipment and maintenance service for the call center operation at no cost, Company C did not incur any expenses for equipment or maintenance support. Nonetheless, Company A paid Company C for system usage and maintenance service. The KFTC believed that the act constituted a dealing that transferred undue benefits to the controlling shareholder and his family.

It was a representative action taken by the KFTC on the undue transfer of private benefits between affiliates since the regulation on the act was first adopted, and it drew much attention from the public. The three companies involved in the case challenged the KFTC’s action and filed administrative litigation. The court made a decision favorable to the plaintiff, citing that the competition authority failed to prove the illegality of the dealing. The case is now pending with the Supreme Court.

The Inheritance Tax and Gift Tax Act

Not only the Corporate Law and the Fair Trade Act but also the Inheritance Tax and Gift Tax Act regulates the extraction of private benefits of control. In 2011, the inheritance and gift tax law added a new provision, recognising that the profit generated by an intragroup transaction constitutes a gift given to the controlling shareholder and his/her family when such transaction exceeded the percentage prescribed by law. Specifically, when the revenues originating from an intragroup transaction account for more than 30%16 of the total revenue of the concerned company and the controlling shareholder and his/her family collectively own more than 3%17 of the shares at the company, the after-tax operating profit multiplied by the respective excess percentages is recognised as a gift.

The tax law does not prohibit the undue private interest taking by the controlling shareholder outright. It instead taxes the benefit coming from an intragroup dealing as a disincentive. Meanwhile, an issue has arisen that intragroup transaction might drop below the legal threshold through a corporate merger, division, business transfer, and the like. Then, it is no longer subject to the regulation even if the problematic transaction continued.

A full amendment to the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act

On 16 March 2018, the KFTC set up a special committee to overhaul its antitrust law with view to effectively responding to rapid changes in the economy and tidying up the code that underwent piecemeal amendments on an ongoing basis for years. The special committee consisted of 23 specialists including 22 from the private sector, with three sub-committees covering competition law, conglomerate regulation, and procedural law, respectively.

The sub-committee covering conglomerate regulation, which has relevance to this report, proposed to reform i) the conglomerate designation rule; ii) the restriction on voting rights at financial and insurance companies and the regulation on public-service corporations; iii) the ban on circular shareholding; iv) the law on the extraction of private benefits of control; v) the disclosure about overseas affiliates to make it more stringent; and vi) the holding company system. Based on the special committee’s proposals, the KFTC made an announcement of the upcoming legislation in August the same year. The bill currently awaits the approval of the National Assembly.

Conglomerate Designation Rule

The full amendment revised the threshold for the designation as a “business group subject to limitations on cross-shareholding” from KRW 10 trillion to 0.5% of the gross domestic product (GDP), so that the threshold may flexibly move in line with economic growth. The new rule applies from the year after the year when 0.5% of the GDP exceeds KRW 10 trillion.

The government expects that the change will ease difficulties on the part of companies that may be caused by the constancy and unexpected turn of the threshold and raise the predictability of the designation.

In the meantime, as for the business groups subject to disclosure, the existing threshold remains unchanged at KRW 5 trillion. Since the disclosure requirement was adopted for the sole purpose of curbing the extraction of private benefits of control, apart from the economic concentration concern, the need for tying it to the size of the economy is minimal.

Restrictions on financial/insurance companies’ voting rights and public-service corporations

In principle, the full amendment prohibits a public-service corporation belonging to a “business group subject to limitations on cross-shareholding” from exercising voting rights on the shares it holds at an affiliate. Same as the financial and insurance companies forming a business group, a public-service corporation is allowed to exercise voting rights at a listed affiliate on the agenda of electing/dismissing directors and conducting a corporate merger, among others. Still, it cannot vote to exceed 15% of the shares held by it and its related party combined. For the soft-landing of the new rule, the authorities will give a grace period, and reduce the maximum limit of the voting rights in stages over three years (30% → 25% → 20% → 15%).

If a public service corporation which is a member of a “business group subject to disclosure” intends to trade shares and engages in a transaction with an affiliate over a particular level, which shall be determined by the relevant Presidential Decree, it is required to obtain board approval and disclose the details.

The special committee mandated to revise the antitrust code advised that the newly amended law lowers the maximum limit of the voting rights that financial and insurance companies can exercise to 5%, and removes corporate mergers and transfer of business from the agenda list they can vote. The final amendment proposal did not accept the 5% limit, but it eliminated a merger and business transfer between affiliates from the agenda list available for voting.

Ban on Circular Shareholding

The special committee agreed that there is a benefit in keeping the ban on circular shareholding against potential business group candidates, even though the shareholding type has mostly disappeared in Korea. It then concluded that restricting voting rights instead of forcing the disposal of a circular shareholding is more in line with the principle of minimised damage or proportionality principle.

The full amendment requires that the voting right restrictions apply even to the existing shareholdings of a newly designated “business group subject to restrictions on cross-shareholding.” The requirement is intended to discourage a business group candidate from creating or building up circular shareholding before being designated as a business group.

Regulation on Extraction of Private Benefits of Control

The proposal to fully amend the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act requires that a company whose controlling shareholder owns 20% or more of its shares be subject to the regulation on the extraction of the private benefit of control, regardless of whether the company is listed or not. The rule also applies to an affiliated company more than 50% owned by a company subject to the concerned regulation. The special committee’s proposal was accepted without any conflicting view.

Strengthened disclosure of overseas affiliates

The special committee proposed that the controlling shareholder of a business group disclose the shareholdings or circular shareholding that an overseas affiliate has at the domestic affiliated companies, either directly or indirectly. The disclosure shall also include the matters about a foreign affiliate 20% or more owned by the controlling shareholder and its subsidiaries. The full amendment did not accept the part requiring disclosure about subsidiaries.

The Holding Company System

The special committee advised raising the ownership ratio thresholds at subsidiaries and sub-subsidiaries. It also proposed that joint ownership of a sub-subsidiary be prohibited and disclosure of related-party transactions by holding companies be strengthened to prevent the transfer of profits for private interest other than dividends. The full amendment raised the ownership thresholds at subsidiaries and sub-subsidiaries by ten percentage points to 30% for listed firms and 50% for unlisted firms. The new rule applies to a holding company that is newly incorporated or converted. Although the amendment does not apply to an existing holding company and its subsidiaries and sub-subsidiaries, a current holding company acquiring a new subsidiary or sub-subsidiary is subject to the regulation. The rule does not apply to a venture holding company to promote investment in the sector. As for the strengthened disclosure requirement on a holding company’s related-party transactions, the Enforcement Decree shall specify it.

copy the linklink copied!Conclusion

The Korean government has made efforts from diverse angles towards the improvement of corporate governance of large business groups since the early 2010s when economic democratisation emerged as a hot topic. Notably, the Corporate Law adopted a rule on the taking of corporate opportunities, and the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act added a provision on the extraction of private benefits of control. It is also notable that a mandatory disclosure requirement was imposed on large business groups, and the scope of the disclosure was expanded to include their ownership structure, among others.

The various policy measures that the Korean government has adopted over the years or is currently pushing for legislation testify to the fact that the government is undoubtedly aware of the concerns local and global investors have about business conglomerates in the country. Although it is not radically fast-paced, the reform is progressing step by step in the right direction that is in line with the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance.

The government is equally aware that forceful regulation is not a proper solution when it comes to corporate governance. Instead, it takes a prudent and market-friendly approach of raising market awareness and asking companies for their voluntary efforts. A good example is the KFTC’s action to induce market scrutiny by mandating companies to disclose their ownership structure and the matters about corporate governance, their transactions involving a related party and the matters about a business group.

In addition to the regulatory measures to improve corporate governance that this report highlighted, the government has also tried to provide support for sharpening the competitiveness of the companies and invigorating their business activities in an ever-changing business environment. The Corporate Law reduced the liability to be borne by directors to incentivise creative and entrepreneurial decision-making. For increased flexibility in the large business group regulation, the law also raised the threshold for the designation of a business group subject to limitations on cross-shareholding. The government has worked hard to strike the right balance between keeping the merits of a business group system and minimising the side-effects. Going forward, it will continue this endeavor and spare no effort to create an environment where companies, investors, and all stakeholders communicate more and better.

References

OECD (2015), G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264236882-en.

FSC and FSS (2018), Plan for Comprehensive Supervision of Financial Conglomerates, 1 February, https://www.fsc.go.kr/downManager?bbsid=BBS0048&no=123601

KFTC (2019), The 2019 list of business groups subject to disclosure, 15 May.

Korea.net (2019), Korea sees the highest growth among OECD’s 30-50 club members, http://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Business/view?articleId=168953

Notes

← 1. Korea sees the highest growth among OECD’s 30-50 club members, 11 March 2019 Cheong wa dae

← 2. Translation provided by the Korea Law Translation Center.

← 3. For non-financial companies, a sum of total assets as of the end of the previous business year; for financial companies, an amount of the larger of the capital stock and total capital.

← 4. Until 2016, the threshold for the business group restricted for cross-shareholding stood at KRW5 trillion. Following an amendment to the Fair Trade Act in 2017, the threshold rose, and the category of business groups subject to disclosure was newly installed.

← 5. The 2019 list of business groups subject to disclosure, announced by the KFTC on 15 May 2019.

← 6. Exclusive of the special purpose companies such as SPAC.

← 7. 30% for listed firms and 20% for non-listed firms.

← 8. Translation provided by the Korea Law Translation Center.

← 9. Translation provided by the Korea Law Translation Center.

← 10. Translation provided by the Korea Law Translation Center.

← 11. Translation provided by the Korea Law Translation Center.

← 12. Plan for Comprehensive Supervision of Financial Conglomerates, published by FSC and FSS, 1 February 2018

← 13. Translation provided by the Korea Law Translation Center.

← 14. Out of the total capital stock of an affiliate, the portion of the combined stock value held by the controlling shareholder and related parties including family members and affiliates.

← 15. The percentage of the shares held by the controlling shareholder and his/her family.

← 16. 50% for small companies and 40% for stable mid-sized companies. Up to the ratios, the law recognizes intra-group trading without having an issue of private-benefit taking.

← 17. 10% for small and mid-sized companies. This includes indirect shareholding via an affiliate, and the law uses the term "marginal percentage of shareholding."

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/859ec8fe-en

© OECD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.