Self-rated health

How individuals assess their own health provides a holistic overview of both physical and mental health. Adding such a perspective on quality of life complements life expectancy and mortality indicators that only measure survival. Further, despite its subjective nature, self-rated health has proved to be a good predictor of future health care needs and mortality (Palladino et al., 2016[24]).

Most OECD countries conduct regular health surveys that include asking respondents how, in general, they would rate their health. For international comparisons, socio-cultural differences across countries may complicate cross-country comparisons of self-assessed health. Differences in the formulation of survey questions – notably in the survey scale – can also affect comparability of responses. Finally, since older people generally report poorer health and more chronic diseases than younger people do, countries with a larger proportion of older people are likely to have a lower proportion of people reporting that they are in good health.

With these limitations in mind, almost 9% of adults considered themselves to be in poor health, on average across OECD countries in 2019 (Figure 3.22). This ranged from over 15% in Korea, Lithuania, Portugal and Latvia to under 4% in Colombia, New Zealand, Canada, Ireland, the United States and Australia. However, the response categories used in OECD countries outside Europe and Asia are asymmetrical on the positive side, which introduces a comparative bias to a more positive self-assessment of health (see the “Definition and comparability” box). Korea, Japan and Portugal stand out as countries with high life expectancy but relatively poor self-rated health.

Among the few countries with data available for 2020, nearly all reported a reduction in the proportion of the population reporting themselves to be in bad or very bad health compared with 2019, with Finland reporting no change and no countries reporting an increase. While the data must be interpreted with caution – data are available for only seven countries and these include countries where the COVID-19 pandemic did not severely test health systems – it could be an indication of the influence of context on perceived health: health issues that may previously have been considered more serious may be downplayed in the context of the pandemic.

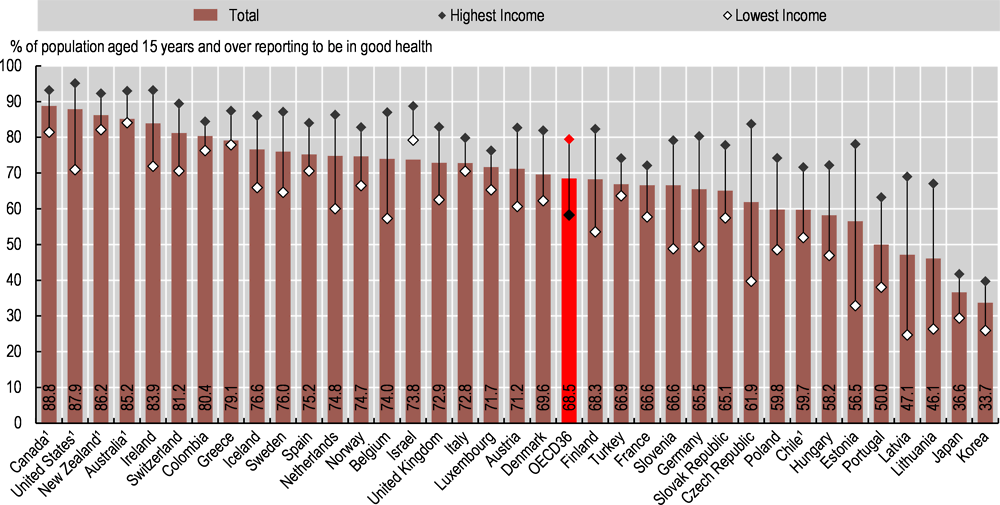

People on lower incomes are on average less positive about their health than those on higher incomes in all OECD countries (Figure 3.23). Almost 80% of adults in the highest income quintile rated their health as good or very good in 2019, compared with under 60% of adults in the lowest income quintile, on average across OECD countries. Socio-economic disparities are particularly marked in Latvia, Estonia, the Czech Republic and Lithuania, with a percentage point gap of 40 or more between adults on low and high incomes. Differences in smoking, harmful alcohol use and other risk factors are likely to explain much of this disparity. Socio-economic disparities are relatively low in Australia, Colombia, Greece, Israel and Italy, at less than 10 percentage points.

Self-rated health tends to decline with age. In many countries, there is a particularly marked decline in how people rate their health when they reach their mid-40s, with a further decline after reaching retirement age. Men are also more likely than women to rate their health as good.

Self-rated health reflects an individual’s overall perception of his or her health. Survey respondents are typically asked a question such as: “How is your health in general?” Caution is required in making cross-country comparisons of self-rated health for at least three reasons. First, self-rated health is subjective, and responses may be systematically different across and within countries because of socio-cultural differences. Second, as self-rated health generally worsens with age, countries with a greater share of older people are likely to have fewer people reporting that they are in good health. Third, there are variations in the question and answer categories used in survey questions across countries. In particular, the response scale used in the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia and Chile is asymmetrical (skewed on the positive side), including the response categories: “Excellent / very good / good / fair / poor”. In most other OECD countries, the response scale is symmetrical, with response categories: “Very good / good / fair / poor / very poor”. This difference in response categories may introduce a comparative bias to a more positive self-assessment of health in those countries that use an asymmetrical scale. In Korea, differences in survey methodology may bias self-rated health downwards compared with other general household surveys.

Self-rated health by income level is reported for the first quintile (lowest 20% of income group) and the fifth quintile (highest 20%). Depending on the survey, the income level may relate to either the individual or the household (in which case the income is equivalised to take into account the number of people in the household).

References

[18] Euro-Peristat Project (2018), European Perinatal Health Report: Core indicators of the health and care of pregnant women and babies in Europe in 2015.

[13] GLOBOCAN (2018), Cancer Today, https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home.

[9] Health System Tracker (2021), COVID-19 continues to be a leading cause of death in the U.S. in June 2021, https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/covid-19-continues-to-be-a-leading-cause-of-death-in-the-u-s-in-june-2021/.

[14] International Diabetes Federation (2017), IDF Diabetes Atlas, 8th edition, International Diabetes Federation, Brussels.

[1] James, C., M. Devaux and F. Sassi (2017), “Inclusive growth and health”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 103, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/93d52bcd-en.

[25] Lumsdaine, R. and A. Exterkate (2013), “How survey design affects self-assessed health responses in the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe”, European Economic Review, Vol. 63, pp. 299-307, https://doi.org/I:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2013.06.002.

[8] Mackenbach, J. et al. (2015), “Variations in the relation between education and cause-specific mortality in 19 European populations: A test of the ‘fundamental causes’ theory of social inequalities in health”, Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 127, pp. 51-62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.021.

[5] Morgan, D. et al. (2020), “Excess mortality: Measuring the direct and indirect impact of COVID-19”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 122, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/c5dc0c50-en.

[4] Murtin, F. et al. (2017), “Inequalities in Longevity by Education in OECD Countries: Insights from New OECD Estimates”, OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2017/02, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6b64d9cf-en.

[15] NCD Risk Factory Collaboration (2016), “Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants”, Lancet, Vol. 387, pp. 1513-1530, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8.

[19] OECD (2021), A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems: Tackling the Social and Economic Costs of Mental Ill-Health, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4ed890f6-en.

[21] OECD (2021), “Supporting young people’s mental health through the COVID-19 crisis”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/84e143e5-en.

[20] OECD (2021), “Tackling the mental health impact of the COVID-19 crisis: An integrated, whole-of-society response”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0ccafa0b-en.

[26] OECD (2019), Health for Everyone? Social Inequalities in Health and Health Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3c8385d0-en.

[17] OECD (2018), “Children & Young People’s Mental Health in the Digital Age”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Children-and-Young-People-Mental-Health-in-the-Digital-Age.pdf.

[11] OECD (2015), Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes: Policies for Better Health and Quality of Care, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264233010-en.

[23] OECD (2015), Recommendation of the Council on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy, http://legalinstruments.oecd.org (accessed on 22 October 2018).

[27] OECD (2013), Cancer Care: Assuring Quality to Improve Survival, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264181052-en.

[22] OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2019), Lithuania: Country Health Profile 2019, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/35913deb-en.

[10] OECD/Eurostat (2019), “Avoidable mortality: OECD/Eurostat lists of preventable and treatable causes of death”, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Avoidable-mortality-2019-Joint-OECD-Eurostat-List-preventable-treatable-causes-of-death.pdf.

[12] OECD/The King’s Fund (2020), Is Cardiovascular Disease Slowing Improvements in Life Expectancy : OECD and The King’s Fund Workshop Proceedings, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/47a04a11-en.

[24] Palladino, R. et al. (2016), “Associations between multimorbidity, healthcare utilisation and health status: Evidence from 16 European countries”, Age and Ageing, Vol. 45/3, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw044.

[3] Parmar, D., C. Stavropoulou and J. Ioannidis (2016), “Health Outcomes During the 2008 Financial Crisis in Europe: Systematic Literature Review”, British Medical Journal, p. p. 354, https://www.bmj.com/content/354/bmj.i4588.

[2] Raleigh, V. (2019), “Trends in life expectancy in EU and other OECD countries: why are improvements slowing?”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 108, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/223159ab-en.

[6] Rossen, L. et al. (2020), “Excess Deaths Associated with COVID-19, by Age and Race and Ethnicity — United States, January 26–October 3, 2020”, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, Vol. 69, pp. 1522–1527, https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6.

[7] Roth, G. et al. (2018), “Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017”, The Lancet, Vol. 392/10159, pp. 1736-1788, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32203-7.

[16] Smylie, J. et al. (2010), “Indigenous Birth Outcomes in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States - an Overview”, The Open Women’s Health Journal, Vol. 4/2, https://doi.org/10.2174/1874291201004020007.