copy the linklink copied!2. The conceptual framework

This chapter introduces the OECD conceptual framework for service design and delivery using different experiences from OECD member and non-member countries.

First, the context for design and delivery of services looks at politics, legacy channels and technology and the society and geography of a country.

Second, the philosophy for the design and delivery of services considers the leadership and vision provided, and then associated behaviours to embed these ideas within the public sector including understanding, and responding to whole problems; services that make sense from end to end; involving the public; combining policy, delivery and operations across organisational boundaries; and taking an agile approach.

Finally, the different enabling resources to facilitate the design and delivery of services. This includes sharing best practice and guidelines; governance, spending and assurance; digital inclusion; common components and tools; data governance and its application for public value and trust; and public sector talent and capabilities.

Given the context discussed in Chapter 1, there is a need to review how countries might build on previous efforts for administrative simplification or a focus on particular life events to use digital government approaches to meet the needs of citizens through designing proactive, data-driven and omni-channel services with the agility to deploy and effectively embrace emerging technologies where appropriate. To take into account and rationalise the historic context, better embed a service design culture, and mature the conversation about enabling resources the OECD proposes the conceptual framework at Figure 2.1. This provides the basis for analysing the situation facing any country in terms of thinking through its strategic approach to the needs of those interacting and engaging with the state. In presenting the framework this chapter explores different experiences from OECD member countries.

The framework consists of three elements that combine to deliver high quality and reliable services:

-

1. The context for design and delivery of services: the way in which services are designed and delivered is informed by the history of delivering services (channel strategy) in a country, political support for the agenda, and the role of legacy technology amongst other factors.

-

2. The philosophy for the design and delivery of services: the activities and practices that direct current activity and contribute to the decisions about the design and delivery of services. This focuses on leadership and vision as well as approaches to service design and delivery itself.

-

3. The enablers to support the design and delivery of services: the resources that have been developed by countries in order to facilitate teams in the design and delivery of services. This includes sharing best practice and guidelines (including guiding principles, style guides and reference manuals); governance, spending and assurance (including business cases, budget thresholds, procurement, service standards and assurance processes); digital inclusion (including digital literacy, connectivity and accessibility); common components and tools (such as digital identity, notifications, payments and design systems); data governance and its application for public value and trust; and public sector talent and capabilities (including recruitment, communities of practice, training and consultancy).

copy the linklink copied!Context for design and delivery of services

Service delivery is integral to the activity of the public sector and foundational to the experience citizens and businesses have of government. As such, any analysis of the design and delivery of services needs to consider the existing circumstances. In this way, the conversation about service design and delivery reflects the ‘contextual factors’ identified by the OECD as shaping the governance of digital government. Produced by the OECD Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials Task Force on Governance, Box 2.1 summarises a framework with which to analyse the context surrounding the entire digital government agenda. Although many, if not all, of them influence the way in which services can be delivered in a country there are some which are important in considering the breadth of channels available to the public and strategically understanding how they can work together.

During 2018-2019 the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials convened a Task Force to consider the question of the governance for digital government. Their discussions provided the basis for a handbook designed to equip governments with the necessary insights to consider how to approach the overall governance of digital government. The draft proposes framing those discussions around Contextual factors, Institutional models and the Policy levers required to support implementation.

The discussion around contextual factors identified the following themes:

-

1. Overall political and administrative culture including power structure; geopolitical situation; defence and security; legalistic versus non-legalistic system; role of elected governments; nature of regulations; political continuity; extent of autonomy in terms of regional government; the extent to which a country is centralised or decentralised; and procurement culture.

-

2. Socio-economic factors including overall economic climate; digital literacy of the population; levels of e-commerce and adoption of digital within businesses; levels of competitiveness and innovation; public sector digital skills; public trust; societal diversity; migration flows in society.

-

3. Technological context including digital connectivity infrastructure; extent to which government or the private sector has legacy technology; integration of IT and digital into business; government specific technological innovations

-

4. Environmental and geographical considerations including local economies; regional variance and geological risks and hazards

Following the 2019 meeting of the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials in Brussels, the Task Force and OECD will continue to develop these ideas and produce materials assisting governments to share and learn from the experiences of responding to the challenges they identify.

Note: Taken from the Draft E-Leaders Governance Handbook prepared for the 2019 meeting of the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials and based on discussion amongst the E-Leaders Task Force on Governance (unpublished)

Representative and organisational politics

The Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]) identifies the need to encourage engagement and participation of public, private and civil society stakeholders in policy making and public service design and delivery. That is complemented by The Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (OECD, 2017[2]) which calls on governments to move towards a “culture of governance that promotes the principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation in support of democracy and inclusive growth”.

The openness with which a government approaches the participation of those outside of government shapes the experience of services, the nature of channels provided and the ongoing design and delivery of government interventions. Although the design and delivery of services is carried out by public servants acting in an apolitical fashion, there is an unavoidable political element to this discussion. The policies that sit behind government services are shaped by the ideologies and commitments of those who have won elections and therefore hold a democratic mandate from the public.

Such dynamics have the potential to politicise the service design and delivery agenda. The emphasis of one service delivery channel or design approach during a particular government or minister’s term runs the risk of being reversed or side-lined by their successors. Efforts to depoliticise the agenda and view it as neutral should be encouraged with all sides being able to support efforts to achieve greater financial efficiency and increases in the quality of the citizen experience.

Nevertheless, with digitally enabled omni-channel service design and delivery reconfiguring how people access government, there can be implications for the public sector workforce and particular communities. The financial and user experience cases for consolidating existing channels and simplifying the landscape of service provision may well be compelling but such an analysis might show face-to-face services as most costly and thereby encourage the use of online or telephone based provision and consolidation of offline networks to reduce demand on physical locations. This will successfully reduce staff overheads but it will also narrow options for accessing physical locations. These decisions, ostensibly driven by the politically neutral ambitions of digital government or administrative simplification, are inherently political because they impact on the lives of voters, public servants and communities. As such, ‘channel shift’ efforts can prompt criticism from politicians, local communities and trades unions. The effect of that criticism can stifle the progress for which there is an ambition and constrain how radical a shift in service provision towards an omni-channel approach is possible.

A final area relates to the organisational structure of service provision in a country. Countries with a high level of centralisation face a different context to those countries with significant local and regional autonomy. However, those nuances may not be clear to the citizen or business trying to access services from ‘government’. Achieving high quality services across channels means responding to the particular contextual implications of the interplay between areas under the responsibility of central government, arms-length agencies or local and municipal government. This is particularly relevant in identifying the needs and challenges faced by smaller organisations operating with more limited resources and highlight the opportunities for collaboration or the provision of additional support (as discussed later in this chapter) to achieve a transformed approach to service design and delivery. The United Kingdom’s Local Digital Declaration, discussed in Box 2.2 presents one example of how central government and local administrations are responding to this challenge but this is not the only model. In Spain, for example, the national legal framework provides regional and local governments with great autonomy and independence while ensuring they are legally recognised as essential participants in the overall governance for digital transformation. Through a comprehensive and complex governance structure the integration of all key actors is secured the development of enabling solutions such as digital identity, managing company powers, interoperability and document exchange systems.

The UK Local Government sector is geographically and politically diverse with a wide spectrum of understanding around what digital transformation means to an organisation. To support and unite local authorities around a shared understanding of good digital practice the UK’s Government Digital Service and Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government launched the Local Digital Declaration.

Designed to help local authorities ‘fix the plumbing’ of digital The Local Digital Declaration forms the basis for local authorities to adopt guiding principles on what good looks like so that regardless of size, location or political governance, any organisation can follow them. It is because so many local authorities have tried and failed to digitally transform in isolation that there is such groundswell and support for a unified approach.

The Declaration addresses the legacy IT contracts, isolation of procurement practices and siloed digital projects that have left local government services vulnerable to high delivery costs and low customer satisfaction for the public they serve. It challenges local and central government, their influencers and the private sector that supplies them, to support “building the digital foundations for the next generation of local public services." It sets out principles that support local authorities to follow open standards and best digital practices with view to developing a common, open approach to digital service transformation across government.

Each signatory of the declaration commits to the co-published principles of good digital and to supporting local authorities in following them. It has been written for local authority leadership to embrace and use as a central point for cultural change that supports the embedding of digital transformation within the organisations.

This is the first collective agreement that has brought central and local government together in consensus on what good digital practice is. It was developed through one-to-one engagement and relationship building. Workshops teased out an understanding of what prevented digital innovation, why procurement was isolated and why change had not been forthcoming. To begin with the Local Digital Declaration had 45 co-publishers and today has over 200 signatories, showing the demand for support and change but also offering testimony to the detailed and exemplary engagement bringing together voices from across the public sector, their influencers and suppliers.

Source: Local Digital and the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2018[3]) The Local Digital Declaration; OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (2018[4]) The Local Digital Declaration

Historic channel strategy

The evolution from analogue to digital government has left a large footprint. The processes, data flows and channels for delivering services that exist are more often than not the product of various central government or institutional channel strategies and other pressures such as those exerted by administrative simplification campaigns.

Some countries (Box 2.3) have recent histories that make it possible to consider the design and delivery of services from the ground up and ensure coordination from the outset. However, the experience for the majority is to find a patchwork of different channels with different responsibilities. While some organisations may have been able to preserve physical locations for providing face-to-face services in other contexts financial pressures and an efficiency agenda will have seen them close. Alongside those channels, the development of different digital and telephone based channels may have taken place without coordination between organisations meaning that users have to visit multiple locations to address a particular need.

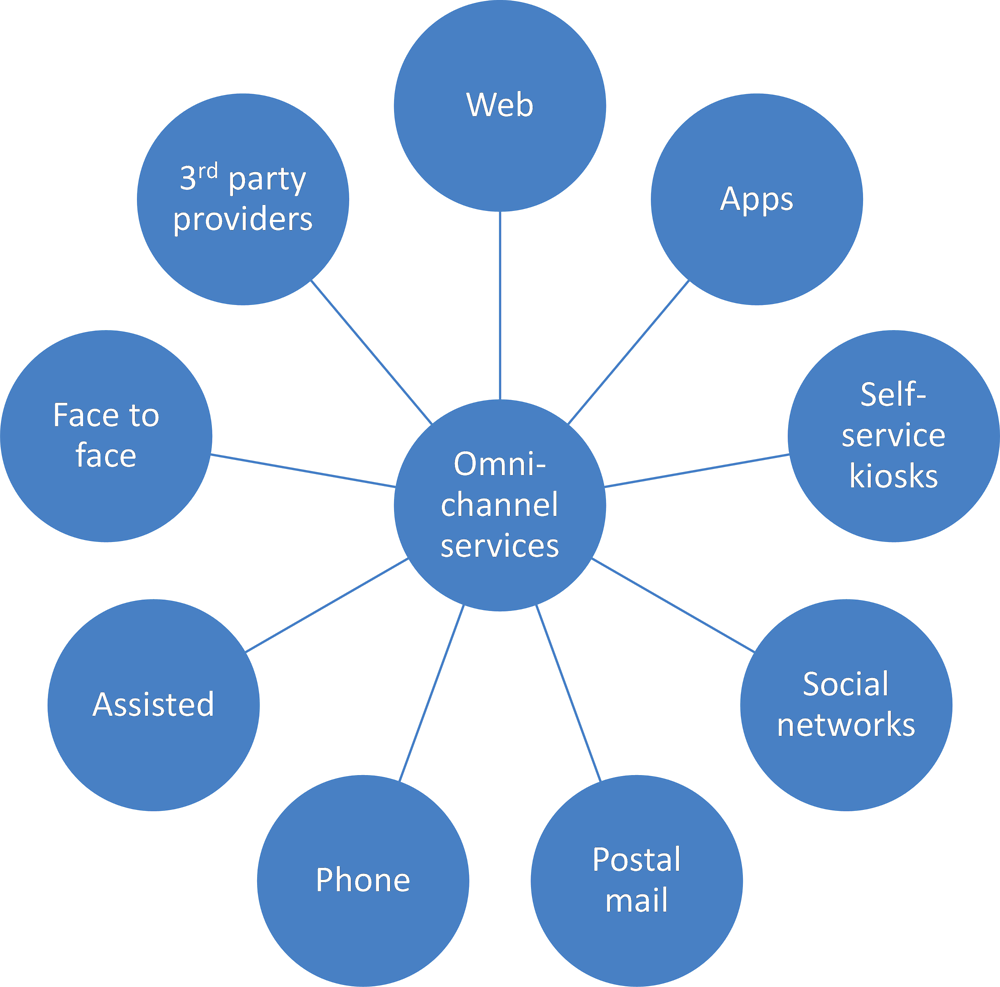

Whilst a country, or its organisations, may have a multi-channel approach the lack of synergy between web, telephone and in-person services may mean an interaction begun online cannot be completed in person and vice versa. Furthermore, contractual arrangements relating to call centres may not be compatible with the needs of physical locations or with whoever is providing the online channels. As a result, an omni-channel strategy, that is where all channels are interchangeable in terms of what they provide and the extent to which an issue can be resolved, are more challenging to implement.

Without a unifying strategy for the design and delivery of services the user experience is left confused while the scale of the challenge to rationalise and consolidate may seem insurmountable. Mapping and understanding the landscape of how different channels operate and where opportunities for partnership might be possible is critical to delivering a transformation in the quality of services which citizens and businesses can access.

Following independence from the Soviet Union in 1990, Estonia had the opportunity to approach the organisation and development of its public sector with few preconceptions to constrain its decision making and all of the benefits of an emerging digital sophistication. This digital mindset benefitted from a no-legacy culture that allowed the country to develop administrative processes and an organisational culture that exploited digital technologies to deliver services.

As such, not only is the expectation of high quality digital services embedded within the population of the country, it has created a political environment in which digital leadership is highly regarded and innovation encouraged.

Indeed, that experience has translated into the planning efforts of the Estonian government in following the idea of “no legacy” as a principle requiring the redesign of any government information system older than 13 years. It aims to sustain government agility in the longer term by continuously adapting to changes in context. The length was determined based on the length of typical information system life cycles in the private sector and allowing for a “public sector” margin.

Source: Taken from the Draft E-Leaders Governance Handbook prepared for the 2019 meeting of the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials and based on discussion amongst the E-Leaders Task Force on Governance (unpublished); OECD (2015[5]) Public Governance Reviews: Estonia and Finland

Legacy of technology and infrastructure

A third area that shapes the context for designing and delivering government services are the tangible artefacts that result from previous efforts in this area. Some of those artefacts relate to the infrastructure associated with physical locations: not only in the buildings but in the associated habits formed by citizens and communities around their use. Where this model has been adopted by several networks there can be a duplication of physical locations in the same community. In these cases, there may be efforts to consolidate all services under one roof in order to achieve twin outcomes of simplifying the experience of government and rationalising its property estate.

In realising the strategic opportunities associated with broadening service delivery that and designing responses to the needs of the public face to face service channels remain a critical bridge between the government and citizens. As such, making sense of this physical infrastructure and identifying the potential for all networks to work together in supporting access to services is critical.

Alongside the physical infrastructure there can also be a legacy of brand recognition and awareness. Whilst some parts of society may deal with government on a regular basis there will be those who perhaps interact once a year. For those who seldom deal with government the importance of brand continuity may mean that they are suspicious about any new design if the change is not well communicated. Equally, if websites are to be consolidated and services delivered through new online channels it is critical to maintain the integrity of the internet and ‘leave no link behind’ so that bookmarks can be maintained (Box 2.4).

Whilst the physical and conceptual traces of previous networks will feature in the public consciousness of service delivery in a country the internal arrangements and technological logistics within government introduce a further layer of complexity. Institutions will have agreements and ways of working that support the delivery of services that cross organisational boundaries, perhaps through accessing data or developing bespoke technical solutions. In some cases these experiences may have been negative, or constraining. Ensuring that valuable relationships can continue while also revisiting those which have proven problematic is an integral factor in achieving greater interoperability and avoiding unintended consequences for the services that have accreted over time.

Indeed, the contractual arrangements between a government institution and the management of its web, telephone or physical service delivery channels is potentially one of the most significant barriers to transformation of the citizen experience. The legacy of existing arrangements may mean that contracts do not have break clauses or would incur significant costs around making the necessary architectural and infrastructure changes to align with a new strategic direction. Nevertheless, this can be helpful as the dates associated with contracts that reflect this sort of situation can shape a country’s roadmap and timeline towards its transformation allowing for a more effective and considered prioritisation process to take place.

Over time government web estates expand. Every organisation, each service, and even short lived campaigns might end up with their own domain. As sites decay and are closed down, little thought is given to the URLs stored in bookmarks, on printed materials or buried in other services. Many organisations decide that redirecting sites is an onerous task, so they either redirect all the old links to the front page of the new site, or simply switch the site off in its entirety. When URLs change, the ‘strands’ of the World Wide Web break and people cannot find what they are looking for.

For the United Kingdom the centrepiece of its digital government agenda is rationalising all citizen facing government websites into a single domain – GOV.UK. This meant over 1 500 domains, containing over 1 million URLs would need to be closed down with the content either being archived, or transitioned onto GOV.UK. Rather than removing those URLs, the team committed creating individual redirections for each and every page so that users either found the archived content or the equivalent page on GOV.UK. Committing to preserve URLs like this isn’t just about being good citizens of The Web but about putting users first to ensure that when people follow links and bookmarked pages they do not see ‘404, Page Not Found’.

Source: Government Digital Service (2012[6]) No link left behind (https://gds.blog.gov.uk/2012/10/11/no-link-left-behind/)

Society and geography

The final area to consider in terms of the context for understanding the appropriate blend between online, telephone and face to face based service provision in pursuit of transforming design and delivery of services is the character of the country’s population and its geography.

As countries have pursued ever greater levels of digital service provision and sought ‘digital by default’ approaches to identity or accessing other services a foundational enabler, and constraint, is the level of connectivity experienced in a country. This can either be through the provision of high speed internet to people’s homes, the extent to which there is coverage for mobile data connectivity and the affordability of those data connections themselves. Governments may take steps to enshrine access to the internet as seen in Mexico where access to the internet has been established as a fundamental right within the constitution with Mexico Conectado then supplying internet access to 250,000 public spaces including hospitals, libraries, schools and government offices (Box 2.5). Understanding the connectivity landscape and ecosystem in a country allows for a more sophisticated response to encouraging adoption of services while ensuring the discussion around face to face provision and community internet access is strategic and led by data.

A further factor that can be supported at a community level is around digital inclusion and digital literacy. Supporting citizens to increase their use of digital services and transition away from face to face locations implies that sufficient attention is also given to the needs of those who cannot use online services. In this case physical and telephone locations not only retain an important role in resolving the need of the citizen but in providing training and support to users that give them confidence to try a digital route in future. Nevertheless, some of these challenges are broader than digital literacy and touch on education in general: data from 2016 show that for OECD countries, an average of 54% of individuals with higher education submitted forms through public websites compared to 17% of individuals with lower levels of education (OECD, 2017[7]). Box 2.5 highlights through the 710 000 tablets delivered to schools across Mexico to support literacy and digital literacy that the enshrining of internet access as a right is not just about connectivity but about being able to consume it.

Aside from education, there is also evidence to show that level of income and age are further determinants of confidence in using digital services, and consequently likely to influence the extent to which face to face or telephone services are preferred. Data from 2016 show that for OECD countries, about 49% of the richest quartile of society access online services compared to 25% of the poorest and furthermore, while 42% of those aged between 25-54 went online to interact with government, only 24% of people aged 55-74 did so (OECD, 2017[7]). Consequently, a detailed understanding of age, education and income is essential to developing a national strategic approach to the design and delivery of services.

A final area to consider is that of geography. The terrain of a country may impede the ability to deliver full connectivity whilst disparate populations spread out across a wide area will mean face to face provision will never provide full coverage. In Chile, the ChileAtiende network has developed a response to this particular challenge with one in five of its locations not having a permanent office, but instead being served periodically by a mobile venue. This ensures that more remote communities are not denied the opportunities to resolve their issues with the state. In this way a digital channel strategy needs to be aligned with questions of digital inclusion and digital connectivity to ensure that nobody is left behind in the fundamental responsibility of the state to deliver services to citizens. This is well demonstrated by the experience of Portugal where the face to face approach offered through its Citizens Shops and Citizen Spots (see Box 2.18) was a necessary complement to its telephone and web-based offering due to the limited levels of internet access within the population at the time.

In April 2013 Mexico established a governance model for coordinating various activities under its Digital Strategy and later that year, on 11 June 2013 The Telecommunications Amendment was published which provided the legal basis for a complete transformation of the way in which the country approaches its digital transformation.

Central to this transformation is the recognition of access to the internet as a fundamental right, established in the Mexican constitution. Through Mexico Conectado internet access is being brought to 250,000 public spaces including hospitals, libraries, schools and government offices.

However, the approach to digital government in Mexico has a broader focus than internet connectivity:

-

The single government website, gob.mx, was launched in August 2015 to be a single point of access for all citizens. It provides access to more than 4000 government services and consolidates 5000 federal government websites.

-

A platform where citizens can provide ideas, report corruption and participate in building better services and policies.

-

A new ICT policy for improving the way that federal government acquires technology to maximise public value and access better technology. This included launching ‘Fixed-Price Contracts’ for software licensing and ICT related hiring.

-

An Action Plan for implementing the principles of Open Government with a publicly accessible dashboard detailing progress against the commitments at http://tablero.gobabiertomx.org/

-

The creation of datos.gob.mx for publishing datasets and the Mexico Open Network as a supporting network of practitioners discussing and sharing experiences with open data

-

The launch of “Innovation Agents” to identify and respond to public problems with digital and technology solutions.

-

The launch of “Public Challenges” as a means by which citizens could identify and respond to public problems with digital and technology solutions

-

A Digital Inclusion and Literacy Program delivered 710 000 tablets for the school year 2014-2015 in 6 states within the Mexican territory

Source: OECD (n.d.[8]) Digital Government Toolkit – Mexico: National Digital Strategy (https://www.oecd.org/gov/mexico-digital-strategy.pdf)

copy the linklink copied!Philosophy for the design and delivery of services

Having understood the existing context for the service agenda in a country the next area of focus are the practices that shape and direct the strategic activity associated with the design and delivery of services. This relates to the leadership for the agenda, the vision that it sets and then the way in which service design and delivery is approached.

Leadership and vision

The Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]) identifies in its 5th, 6th and 7th provisions the importance of securing the necessary leadership and political commitment to digital government strategies for them to be successful (OECD, 2014[1]). It indicates the need for this to take place through efforts to promote coordination and collaboration, providing clarity about priorities as well as to increase stakeholder engagement and ensuring that the digital government agenda complements and supports other activity within government. Finally it suggests the need for effective organisational and governance frameworks for co-ordinating implementation.

Whilst focused on providing a holistic framework within which to achieve the digital transformation of government as a whole, these ideas are relevant in considering the specifics of service design and delivery. Nowhere is this clearer than at the highest level for elected representatives, their appointees and the senior government officials who lead institutions to recognise the value of putting the application of digital, data and technology at the heart of their country’s future. Individuals throughout the public sector can provide localised leadership and inspire their colleagues to deliver value. However, there is no substitute for the momentum that follows from a clear vision that is owned and shared throughout government for understanding the needs of citizens and including them in the design of their resolution.

Political leadership

From the perspective of political leadership this includes having a clearly expressed vision for the role of digital in the future of the country and as an extension, the implications for service design and delivery. The experience of Estonia (Box 2.3) recognised the value of having a commonly understood role for digital amongst a country’s political leadership from an early stage. In Panama, during the 2019 Presidential election, each candidate made it clear that digital, data and technology were a priority (OECD, 2019[9]).

Having such leadership from the top helps to show that the application of digital, data and technology is not optional but sits at the heart of what a country will be trying to do. As a result, it makes it easier to establish an agenda supported by appointed minsters and that will consequently spread throughout government because there is a mandate from the very top (as seen in Norway Box 2.6). In Chile, several important aspects of the digital government agenda have been enshrined in the Digital Transformation of the State Law (MINSEGPRES, 2019[10]).

As discussed earlier in this chapter (Representative and organisational politics) there can be challenges in having too visible a political champion but this needs to be set against the importance of having the political capital and influence to be able to effect the necessary changes in support of rethinking and redesigning services. Without a clear mandate to address the patchwork of different channels and organisational fiefdoms arriving at a consensus may prove difficult. It is not always sufficient for government leaders to provide funding and other incentives to change the status quo.

The Digitalisation Memorandum (Digitaliseringsrundskrivet) in Norway established that the government should communicate with citizens and businesses through digital services that are comprehensive, user-friendly, safe, and designed to ensure everyone can access them.

In order to achieve this the Memorandum set out specific delivery criteria:

-

By the end of 2017, ministries were required to map the potential for digitalising services and processes with supporting plans for how all appropriate services would then be made available digitally.

-

By the end of 2018, ministries would look at their services in relation to those provided by other organisations and consider whether it is possible to develop ‘service chains’ offering end to end user journeys and solving whole problems. As part of this expectation, plans and strategies for developing those combined services would be developed.

As part of the mapping exercise Norwegian organisations were to identify whether or not services were already digitalised and, if not, assess their level of suitability. The exercise was also designed to assess the quality of existing services in terms of the extent to which they were user-driven, user-centred and user-friendly and judge whether they needed to be re-designed, simplified or even eliminated.

Furthermore, the Digitalisation Memorandum required not only that services were analysed but that the relevant regulatory framework and legislation be reviewed.

Source: OECD, (2017[11]) Digital Government Review of Norway: Boosting the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector

Organisational leadership

While elected representatives set the political direction and high level vision, responsibility for implementing that intent and delivering on the ambitions of government belongs to the civil service. The OECD’s previous work concerning the governance of digital government in Chile (OECD, 2016[12]) highlighted the importance of clearly identifying leadership from an institution to coordinate the strategy and priorities for transformation. Given the relevance of the digital government agenda to the transformation of government services in a country there are benefits to this leadership coming from the same organisation, or if that is not possible, ensuring close coordination.

Indeed, it is critical that leadership of the service design and delivery agenda is understood as a coordinating role and works closely with leaders across the public sector to embed the importance of designing and delivering high quality services in the day to day work of the civil service as a whole. This is particularly important in securing the overall commitment to transforming cross-cutting services that involve multiple parts of the public sector to decrease the potential for duplicated effort.

Civil servants collectively need to embrace the importance of digital transformation in respect of service delivery and work together to open up data, and contribute to the discussions about shared, reusable resources. Nevertheless, inadequate institutional coordination among relevant agendas, such as those on the digital transformation, public services and regulatory reform, can impede a shift of approach towards a coherent use of existing and emerging opportunities to deliver improved service experiences to users.

External leadership

Finally, there is an important leadership role provided by those who are neither elected by the public, nor employed by government. Government cannot choose its users or market services to only a subset of the population and so non-government experiences come with certain caveats but an external perspective can help identify priorities for the service design and delivery agenda, highlight areas that might otherwise be missed and consider how to encourage greater adoption in society. The strategic discussion about services in a country, and digital government itself, will benefit from the insight of academia, civil society and the private sector, as well as the experiences of other countries, to ensure a rounded view of the issues.

Behaviours of service design and delivery

With the necessary leadership identified and strategic direction provided it becomes necessary to think about the characteristics of a service design and delivery culture and how associated good practices might be established and nurtured throughout the public sector. For some parts of government, this will mean making the transition from analogue government straight to digital government approaches whilst in others there will already be a track record in providing e-government services perhaps through administrative simplification efforts or a focus on individual life events. Both situations present their own challenges for subsequently framing desired behaviours around service design and delivery.

This section will consider several of the behaviours of service design and delivery whose presence in a country can contribute to better meeting the needs of the public and transforming their experience of interacting with government. It will look at understanding, and responding to, a whole problem; services that make sense of the end to end experience; involving the public in design and delivery; combining policy, delivery and operations to work across organisational boundaries; and taking an agile approach.

Whether government is considering the renewal of a single service or looking to transform the entirety of government services the scalability of service design and delivery is critical. In doing so it is important to start from a clear and effective definition of ‘services’ and to consequently prioritise those working practices that help deliver against that vision. Box 2.7 presents the work of the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) Thematic Group on Service Delivery and a summary of principles to underpin the design of good services proposed by Lou Downe, one of the leading voices in government service design.

Proposed General Principles for Digital Service Delivery

Under the auspices of the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders), OECD member countries have been considering what constitutes best practice in this area for several years. At the 2017 meeting in Lisbon, Portugal, the Thematic Group on Digital Service Delivery presented a set of General Principles that both member countries and other governments could follow. These principles emerged from the experiences of member countries in implementing their digital agendas.

-

1. User driven - Optimize the service around how users can, want, or need to use it, including cultural aspects rather than forcing the users to change their behaviour to accommodate the service.

-

2. Security and privacy focused - Uphold the principles of user security and privacy to every digital service offered.

-

3. Open standards - Freely adopted, implemented and extended standards.

-

4. Agile methods - Build your service using agile, iterative and user-centred methods

-

5. Government as a platform - Build modular, API enabled data, content, transaction services and business rules for reuse across government and 3rd party service providers

-

6. Accessibility - Support social inclusion for people with disabilities as well as others, such as older people, people in rural areas, and people in developing countries.

-

7. Consistent and responsive design - Build the service with responsive design methods using common design patterns within a style guide

-

8. Participatory process updating - Design a platform to take into account civic participation in the services updates.

-

9. Performance measurements - Measure performance such as Digital take-up, User satisfaction, Digital Service Completion Rate and Cost per transaction for a better decision-making process.

-

10. Encourage Use - Promote the use of digital services across a range of channels, including emerging opportunities such as social media.

Source: Proposed General Guidelines for Digital Service Delivery prepared for the 2017 meeting of the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (Unpublished)

15 principles of good service design

Lou Downe was the Head of Design for the United Kingdom government during the expansion of its service design profession into an established part of the digital, data and technology professional framework for civil service. In that role they encountered lots of teams wanting to know what a good service looked like but found that the service design profession had not developed a language for talking about the purpose of designing services. That prompted them to define that a good service must:

-

1. Enable a user to complete the outcome they set out to do

-

2. Be easy to find

-

3. Clearly explain its purpose

-

4. Set the expectations a user has of it

-

5. Be agnostic of organisational structures

-

6. Require the minimum possible steps to complete

-

7. Be consistent throughout

-

8. Have no dead ends

-

9. Be usable by everyone, equally

-

10. Respond to change quickly

-

11. Work in a way that is familiar

-

12. Encourage the right behaviours from users and staff

-

13. Clearly explain why a decision has been made

-

14. Make it easy to get human assistance

-

15. Require no prior knowledge to use

Source: Downe, (2019[13]), Good Services: How to Design Services that Work; Downe, (2018[14]), 15 principles of good service design

Understanding, and responding to, a whole problem

“Public-facing services allow citizens or their representatives to achieve a desired outcome” (Pope, 2019[15]) and as such the act of designing, and then delivering those services is not a theoretical pursuit but a practical exercise in working with the affected people and adding value to their lives. In order to do that, the first characteristic is to understand the problem in order to respond to what is found rather than setting out to implement what has been imagined.

The starting point for services will be either a newly identified policy intent, or an existing approach to a long-standing problem. In both cases, service design approaches will help to understand the opportunities to deliver value against the policy intent and how the service might practically make sense of the existing landscape. In contrast to sectoral or organisation focused administrative simplification developing that understanding will require looking across the whole of government to understand how different activities are contributing to, or detracting from, the desired policy outcome. Responding to what has been found in order to better meet needs may then require a fundamental redesign of the service, or more minor tweaks to the way in which government is working. Service design involves working out how the existing landscape of government provision fits together, analysing the extent to which needs are being met through them and then identifying how to reconfigure or redesign the approach to improve things.

Taking this approach is important because if a service (whether newly developed, or existing) isn’t immediately understood then people can get confused, make mistakes, or decide not to use it. When that happens it increases the effort government has to invest in order to resolve any issues, and the burden on the citizen to deal with the issue they had in the first place.

In Argentina, an estimated 3 million people have some disability. To certify this disability, the Medical Evaluation Boards (MEB) distributed throughout the country issue a Certificado Único de Discapacidad (disability certificate, CUD) that allows people to access the rights and benefits provided by the Government. According to the National Agency for Disability, 1,405,687 certificates have been issued to the present.

However, despite being a right, the process for obtaining a CUD was a painful and difficult process. There was no digital service to support it with the result that the process could last up to seven months as it involved four steps that required the user to go to a public office in person to:

-

1. Find out what documentation would be required according the disability and age of the person

-

2. Submit the documentation and make an appointment to be evaluated;

-

3. Attend the evaluation by the MEB;

-

4. Receive a paper certificate.

Not only was the turnaround slow but the process itself was adding extra burdens and complexity to people’s lives at a point where they needed increased levels of support.

Having identified that this was a service in need of transformation the National Agency for Disability paired with the team at Mi Argentina, Argentina’s platform for providing citizen centred services to carry out a rediscovery and transformation of the service. This multi-disciplinary team was made up of not only software engineers and designers but also psychologists, political scientists, anthropologists and sociologists. Together the team set out not only with the intent of simplifying and speeding up the process but in coming alongside people as they carry out a difficult process and providing them with the service they deserve.

To do this the team carried out user research by interviewing people with disabilities, their families and health workers. As they built up a picture of the challenges people faced they identified opportunities for simplifying the process and designing an approach that could be carried out online in one step (as opposed to the previous 4).

A wizard now guides citizens through the requirements of their application rather than requiring them to attend a physical meeting to establish what documentation is required. The physical meeting is still required but an online appointment system schedules the interview, meaning that users can avoid hours of waiting in queues. Finally, the service proactively provides notifications in the citizen’s digital profile ensuring the user knows when the CUD is expiring and offering to help with its renewal.

Developing the solution was only part of the challenge because the solution needed to work with the 453 separate MEBs. This is a challenge because of the political structure surrounding MEBs as well as practical considerations like availability of internet access, furthermore the service delivery culture of the MEBs is not guaranteed to be citizen centred. In response the team developed a strategy that would address the relationship between central government and the MEBs, support the practicalities of connectivity and focus on developing the necessary skills through training whilst iterating the CUD service as they learn more about it.

Source: OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, (2018[16]) Redesign of the Unique Certificate of Disability

Services that make sense of the end to end experience

Because government services have often evolved over time with different policy initiatives leading to different interactions a user’s journey can often be somewhat fragmented and hard to trace across different parts of government and different channels. The most effective citizen experiences should not require a detailed knowledge of the inner workings of government or involve the burden of working out how best to meet a need across a myriad of different websites, call centres and service delivery locations. They should instead lead users through a simple to complete process and where possible reuse data to anticipate and proactively address aspects that might otherwise have involved further interactions.

In addition to successfully achieving the impression of seamless government, regardless of the messy reality ‘behind the scenes’, a service design approach prioritises handling the transition between physical, offline and digital elements of a service. Ultimately, a service should be understood:

-

from when someone first attempts to solve a problem through to its resolution (from end to end)

-

on a continuum between citizen experience and back-office process (external to internal)

-

across any and all of the channels involved (omni-channel).

One of the unintended consequences of a ‘digital by default’ agenda was to create situations where difficulties were introduced for those who had a preference, or a need, to access services in person. Following a ‘digital by design’ approach recognises the value that can be added to face to face channels when services are developed in a channel agnostic way that enables users to access a given service at any point in the end to end process of meeting their need, according to their most convenient channel.

In 2012, Panama’s National Authority for Government Innovation (Autoridad Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, AIG) began working with the country’s Justice system to rethink the experience of justice across its several branches of government.

The collaboration involved all the necessary stakeholders and saw a transformative approach taken to the end to end experience in delivering the Accusatory Penal System (Sistema Penal Acusatorio, SPA), which provides the foundation to the way in which courts operate.

AIG’s designers took the existing, complex process and broke it into its constituent parts in order to arrive at an understanding of the needs of both those accessing the services and those providing them. This made it possible to prioritise particular elements of the journey and address different elements over time. By 2018, this resulted in transforming not only existing digital elements but also the issues related to physical infrastructure and analogue interactions in the entire experience of justice. There is no longer any paper involved and it has reduced the time involved by 96%.

Source: OECD (2019[9]) Digital Government Review of Panama: Enhancing the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector

Involving the public in design and delivery

In order to understand the whole problem, teams working on designing and delivering services need to work with the people who need to use the service. Digitally transformed public services need to engage their users as early in the process as possible. This allows the design process to reflect their views, needs and aspirations from the outset. Such an approach is in line with principle 2 of the Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]).

The principles of digital government change the way in which services can be designed and implemented. They create opportunities for citizen-driven activity and civic participation in terms of sharing views, collaborating with peers and expressing dissatisfaction. Service teams that stimulate opportunities for citizens to work with them can embrace innovation and rapidly normalise emerging technology where it can add most value. Having a deep understanding of user needs and an openness to citizen involvement in the process of policy design and service delivery, as seen in Box 2.10, mean teams are well positioned to consider all possible opportunities to apply technology and be agile enough to take advantage when new things arrive.

Partnerships can be developed with community groups and other stakeholders to meet the community and ensure that their experiences shape how government services operate. This approach is exemplified by the experiences of Canada and Portugal in travelling throughout their countries to engage with the community of their users. In Portugal, updating the Simplex model of service delivery (discussed in more detail under Channel Strategy) involved a tour of the regions covering 10 000 kms, speaking to 2 000 people and collecting 1 400 contributions focused on improving the lives of Portuguese citizens (Welby, 2019[17]).

Face to face opportunities not only provide tangible evidence of a responsive government seeking to include the voices of their citizens in the design and application of digital government they can introduce new opportunities to enhance the technical skills and confidence of the public in using online channels, as well as increase their awareness. Supporting citizens to use the internet to access government services has broader benefits in empowering and enabling them to take advantage of other online services.

In January 2018 the Australian government appointed an independent Expert Advisory Panel to advise on the future of employment services in the country. The panel considered it was fundamental for the design of future employment services to centre on users. With this focus, the panel heard from around 1 400 unique users across a range of different methods from face-to-face consultations, a public discussion paper and user-centred design research.

Users were engaged to prototype and test policy options through design research workshops, focus groups and one-on-one interviews. The process involved 550 users of employment services including job seekers and employers. User research was conducted across six metropolitan and regional locations with panel members attending sessions to engage with users first hand.

Those experiences shaped the publication of the department’s discussion paper which was followed by an extensive consultation across Australia in all the capital cities and selected regional centres. The consultation process involved both roundtables and community forums reaching 540 people (Figure 2.2). Alongside the consultation process 451 unique written submissions were received with 328 of those coming from individuals, more than 50% of whom identified as job seekers.

Ultimately, the proposed new employment services model was endorsed and pilots began in March 2019. The service involves a new digital platform that will provide personalised support to all job seekers, with many intended to self-service online. Additional support is available to more disadvantaged job seekers with incentives available to those providing support to them in person.

The new model is being piloted in two regions before being rolled out nationally in 2022. During that period consultation and user-design efforts will continue.

Source: OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (2018[19]), Design and implementation of a citizen centric employment services system; Department of Jobs and Small Business (2018[18]), Employment Services 2020: Consultation report, Commonwealth of Australia (2018[20]), I want to work: Employment Services 2020 Report

Combining policy, delivery and operations to work across organisational boundaries

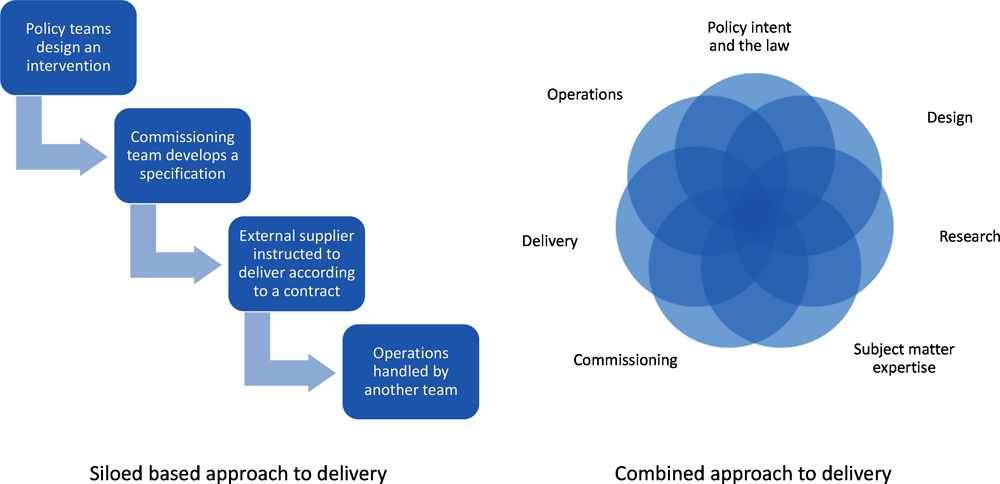

Successfully transforming service delivery necessitates changes to approaches to both policy making and implementation processes. The status quo has been for policy teams to develop an approach which is then handed over to a commissioning team that instructs an external supplier to deliver against a specification and who, in turn, hand the delivered service over to a fourth team to operate.

When policy decisions are taken in isolation from delivery realities, and operational teams have no ongoing relationship with either, then siloes form. Such a disconnected approach causes problems for both the people accessing the service and government itself. Badly designed services benefit neither political objectives, or meet the needs of the public.

The digital government approach recognises the importance of bringing policy, delivery and operations together throughout the implementation lifecycle to ensure a common vision and coordinated development process. As such, it should be an ambition for those designing and delivering services to unite what might otherwise be siloed as a single team, focused on solving a particular problem together, shown in Figure 2.3.

Transformed services rely on diverse, multi-disciplinary teams of designers, developers, subject matter experts, policy officials, lawyers, operational staff, user researchers and content professionals that bring together different perspectives and commit to working across organisational boundaries. Taking a cross-discipline approach and involving those from across government helps to better understand the needs of all users. This idea includes the needs of civil servants within government with the responsibility for administering a service and sits behind the creation of the One Team Government movement (Box 2.11).

Developing cross-government service communities help to create a clear mission that unites all those involved with solving a particular problem for citizens or businesses. In doing so, they help to address several of the other behaviours discussed earlier in the chapter. In the United Kingdom, this approach has seen the creation of 4 different communities involving 236 members from 15 organisations with results ranging from simplifying content and user journeys for members of the public through to the redesign of internal procurement processes (Government Digital Service, 2019[21]).

In the summer of 2017 a conversation between two civil servants in the United Kingdom planted the seed for the idea of a gathering that wasn’t structured around existing tribes of ‘policy makers’ and ‘service designers’ but was focused on bringing civil servants together to talk about shared problems and common goals.

Three months later, 186 people gathered together for an event called One Team Government. It was expected that this would be a one-off but after the success of the event meant those who arranged it were inspired to see it become a community of practitioners shaping the conversation in government.

The community has seven principles:

-

1. Work in the open and positively

-

2. Take practical action

-

3. Experiment and iterate

-

4. Be diverse and inclusive

-

5. Care deeply about citizens

-

6. Work across borders (professions, departments, sectors and countries)

-

7. Embrace technology

Following that first event in London in 2017, these principles have been adopted by chapters in countries and governments around the world. July 2018 saw the first global event with 700 public servants from 43 countries coming together in London in an unconference format to explore how they might share their knowledge and work together to better meet the needs of their users.

In a demonstration that the movement is now truly international and not simply reliant on the original team in London, the 2019 global event took place in Canada where another global gathering discussed 40 different topics with a common theme emerging around improved communication and effective talent management.

Note: A summary of discussions from the 2019 unconference is available here: https://medium.com/oneteamgov/the-2019-oneteamgov-global-report-2fa952dfb37d

Source: Welby (2019[17]), The impact of Digital Government on citizen well-being

Taking an agile approach

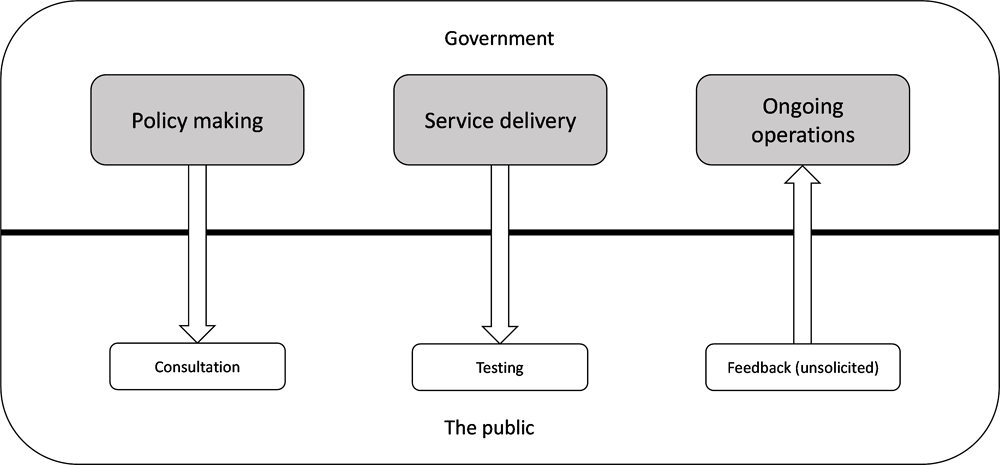

Both the Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]) and the Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (OECD, 2017[2]) place a high premium on ensuring that as governments develop policies and services the public should be involved. Nevertheless, there are different ways and extents to which the ideal of user-driven approaches might be approached during the policy making, service delivery and ongoing operational lifecycle.

The public might be engaged by governments through consultation during the policy design process, in seeking the experience of those affected during pilots during the initial implementation phase and gathering feedback once something is operational. However, as shown in Figure 2.4, these are usually independent of one another, do not feed from one into the next and are generally reactive rather than reflecting and mutual ongoing discussion. A result of this is that policy consultation is siloed from the insights derived from both testing a service before it launches and operational feedback once it is live. As a result, the public end up being secondary to the views and activities of public service teams who are not empowered to understand or deliver against outcomes that transform the wellbeing of citizens.

This situation contributes to the siloed delivery approaches discussed in the previous section (Figure 2.3) and as a symptom of Waterfall approaches to delivery. The traditional Waterfall approach is built around a sequencing of activities or phases that must be completed before moving on to the next. This approach attempts to manage uncertainty by creating a plan up front. In this way requirements are identified as a distinct phase before any work is undertaken. There is then no interaction with the solution or any opportunity to provide feedback until the final product is delivered. You only have one chance to get each part of the project right, because you do not return to earlier stages. Should any change want to be made there are high costs associated with what may need to be the revisiting of fundamental decisions.

In contrast, the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) Thematic Group on Service Delivery advocates for governments to adopt an Agile methodology (Box 2.7). The core values of Agile were first set out in the context of software engineering in the Agile Manifesto below.

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others to do it. Through this work we have come to value:

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more (Beck et al., 2001[22])

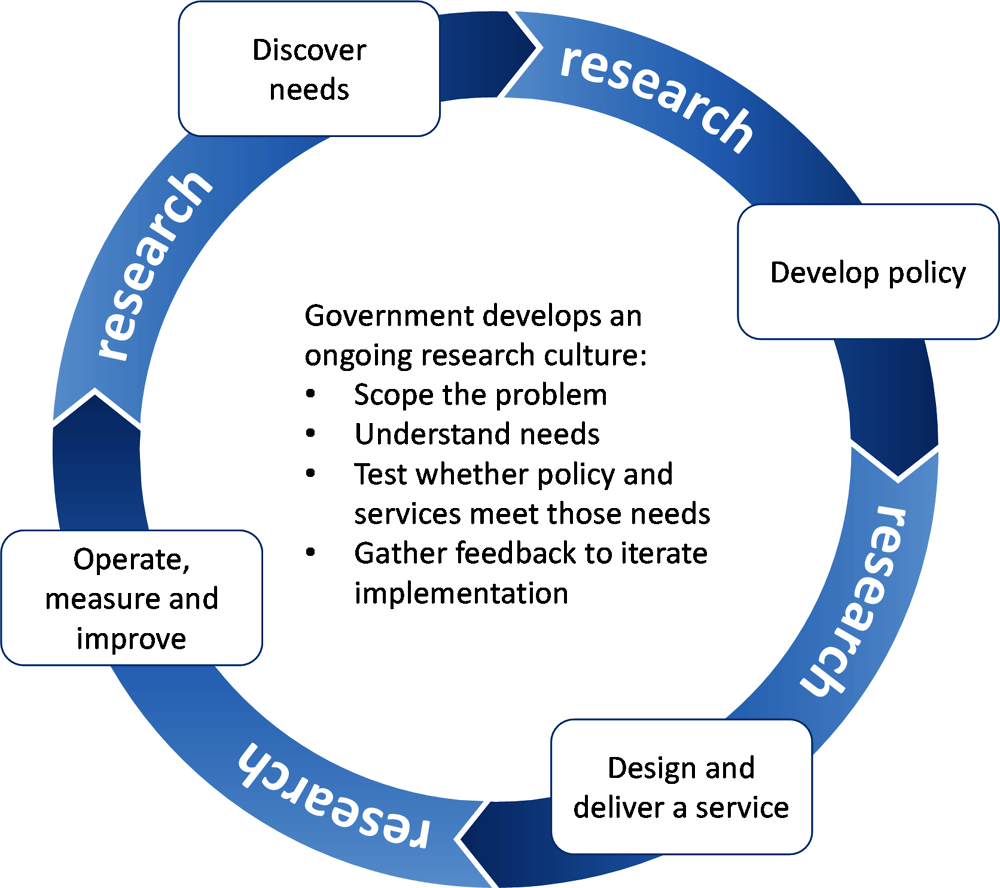

These ideas are increasingly a staple of digital government. Agile involves embracing uncertainty and expecting to continuously learn and improve approaches based on what is learnt in order to prioritise adding value to users as quickly as possible. All the elements found in a Waterfall process are instead carried out concurrently: the activity associated with gathering requirements, planning, designing, building and testing. By starting small with Discovery and Alpha phases teams can research, prototype, test and learn about the needs of their users before committing to building a real service allowing them to fail quickly and correct course in response to what they find. The development of that real service only goes live when enough feedback has been gathered to demonstrate that needs are met and the service works.

Fundamental to this change in approach is the importance of ongoing research and a cyclical model of delivery, Figure 2.5. The separation between the public and government in Figure 2.4 is replaced with government engaging the public on an ongoing basis to explore user-driven approaches and carry out research.

As a result, instead of being initiated in government, policy responds to an understanding of citizen needs based on research conducted with them, reflecting views expressed across a wide sample of the population and informed by insights available from societal data. Having knowledge of the problem in this way allows for the development of policy to be guided and led by the needs of the public rather than the implementation of assumed or paternalistic solutions devised by public servants at their desks. With policy development taking place in close proximity to those carrying out the delivery of the service, research findings can be incorporated into the design and delivery of the service itself. Experimental, hypothesis led interventions involving the public further confirm whether or not a given approach will be effective. At launch, when the policy and any associated services are impacting on real lives, the agile, research-led approach emphasises the continued understanding of the user’s experience to establish impact and respond to any insights in understanding whether the policy is having its desired outcomes.

copy the linklink copied!Enablers to support the design and delivery of services

Simply taking into account the contextual factors influencing the way in which services will be designed and delivered, and setting out a vision for doing so may create a situation that feels daunting in terms of putting transformation into action. Countries may have upwards of 3 000 individual services and it will be slow, expensive and inefficient to redesign and rethink each of those from scratch. Therefore, the provision of ‘Government as a Platform’ enablers are fundamental for helping all those designing and delivering public services to meet the needs of their users at scale, and with pace, while protecting quality and trust.

The OECD considers Government as a Platform to be one of the foundational characteristics of digital government approaches. As a concept there are several ways in which it can be understood whether in supporting service teams, stimulating a marketplace for public services, or rethinking the relationship between citizen and state. These approaches are not mutually exclusive and represent something of a sequential, iterative approach towards creating the conditions for open and innovative government.

Taking the steps to build an ecosystem which supports and equips public servants to make policy and deliver services whilst also encouraging collaboration with citizens, businesses, civil society and others is critical to transforming the process by which services are designed and delivered. The idea of technical shared platforms is not new. The history of e-government contains many examples of shared services and technical interventions designed to offer common solutions to common problems. As a result, enablers can be thought of simply as technology driven interventions. However, this is to overlook the model imagined by Government as a Platform of creating a more holistic ecosystem that provides the resources that can create the conditions in which service design and delivery flourishes and where technology choices are secondary to a focus on the problems facing a particular subset of the public.

It is important to recognise that ‘Government’ is not a single entity but a collection of organisations and teams who work on designing, implementing and operating policy and the services it produces. Consequently, we start with the practical implications of delivering Government as a Platform with the service teams responsible for meeting the needs of citizens. Those teams may consist entirely of in-house capability, they may be outsourced, they may be a hybrid of the two or they may even be delivered independently of government by charities or private companies. Nevertheless, it is their activity which forms the intermediary between government and users and it is in support of their delivery that an ecosystem focused on common needs can abstract away many of the issues which people would otherwise have to do. This section considers eight areas of enabling practices and activities that fit within this Government as a Platform model and can prove transformative in simplifying and accelerating the design and delivery of services. They are:

-

Best practices and guidelines (including style guides and service manuals)

-

Governance, spending and assurance (including business cases, budgeting thresholds, procurement and service standards and assurance processes)

-

Digital inclusion focused activities (including digital literacy, accessibility and connectivity)

-

The channel strategy (emphasising an omni-channel model)

-

Common components and tools (including design systems, hosting and infrastructure, digital identity, notifications, payments, and low code)

-

Data-driven public sector approaches (including strategic, tactical and operational activities)

-

Talent (including recruitment and professions, communities of practice, consultancy and coaching, skills training and skills transfer)

Best practice and guidelines

The first way of enabling teams to deliver high quality services that meet the needs of their users is in providing guidance and materials that can offer insight into the practical steps that can be taken.

Style guide and language

The shift from analogue, via e-government, to digital government has often resulted in a separation of responsibility for serving information to the public and delivering transactions completed by the public. However, to develop services in line with the behaviours discussed earlier in this chapter it is important to recognise the important role that content and language play in the understanding the public might have and therefore the consequent effectiveness of any services that they are consuming.

One way of supporting this is to develop style guides that create consistency and set standards in terms of written communication, whether that is found in letters received through the post, forms completed as part of a transaction, emails triggered by completing a step in process workflow or the web content arrived at from searching the internet. A selection of these are presented in Box 2.12.

The Norwegian Clear Language Project (Norway)

The Norwegian Agency for Public Management and eGovernment (Difi) collaborates with the Norwegian Language Council to encourage user-friendly language in the delivery of public services:

-

The Golden Pen: an online course helping editors in the public sector to write in ways that citizens can understand.

-

klarspråk.no: a website containing practical tools, advice and tips on how to make the language used in service delivery processes clear and user-friendly.

-

Funding Schemes: agencies can apply for financial support for clear language work. In 2016, two support schemes were made available: one for textual vision and one for measuring the effects of language proficiency.

-

Clear Language Prize: an annual award given to public agencies that make an extraordinary effort to use clear and user-friendly language in communicating with citizens and businesses.

Source: OECD, (2017[11]), Digital Government Review of Norway: Boosting the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector

Style Guides by Government Agencies (United States of America)

In the United States, https://digital.gov catalogues 25 different style guides in use across the public sector and encourages public servants to participate in a plain language community of practice. One of the most notable style guides belongs to 18F. It not only covers questions relating to grammar and spelling but also provides guidance in developing ‘user-centred content’ built around five principles:

-

1. Start with user needs.

-

2. Write in a way that suits the situation.

-

3. Do the hard work to make it simple.

-

4. Use plain language and simple sentences. Choose clarity over cleverness.

-

5. Write for everyone.

-

6. Respect the complexity of our users’ experiences.

-

7. Build trust.

-

8. Talk like a person. Tell the truth. Use positive examples and concrete examples

-

9. Start small and iterate.

-

10. Make sure your content works for users. Don’t be afraid to scrap what’s there and start over. Write a draft, test it out, gather feedback, and keep refining

Source: Digital.gov, (n.d.[23]), Style Guides by Government Agencies (https://digital.gov/resources/style-guides-by-government-agencies/)

The Government Digital Service Style Guide (United Kingdom)

The Government Digital Service style guide covers style, spelling and grammar conventions for all content published on GOV.UK. It helps to set standards on how to write using "plain English", bringing consistency to the way government talks to its users and making it as inclusive and simple as possible, across all government services.

Source: GOV.UK, (2016[24]), A to Z – Style Guide – Guidance – GOV.UK (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/style-guide/a-to-z-of-gov-uk-style)

Service manuals

It is not only in the area of content that the shift to digital government introduces a completely different paradigm in terms of the design and delivery of services as discussed in the previous chapter. Blurring the distinctions between historically separated siloes while also introducing skills around user research and agile delivery mean that several countries have developed resources that act as reference materials to embed and establish a particular design culture.

In addition, the development of strategic approaches to the delivery of common technology (discussed later in this section) has also seen countries develop centralised references for architectural decisions and the documentation of associated APIs and integrations. A selection of these are discussed in Box 2.13.

Arquitectura TI (Colombia)

The Colombian IT Architecture Knowledge Base contains all the materials for ensuring that teams deliver against the provision of the country’s Reference Framework for digital government. It includes strategic documents to provide overall understanding, standards identifying technical specifications, step by step guidance materials for engendering a common approach to delivery, shared best practices, the necessary legal underpinnings and a proposed management model to align delivery and strategy within Colombian public sector organisations.

Source: https://mintic.gov.co/arquitecturati/630/w3-propertyvalue-8061.html

GOV.UK Service Manual (United Kingdom)

The United Kingdom’s Service Manual is actively maintained by a team of content designers who work with the different professional communities (design, delivery, product, research, etc.) to establish best practice and document it to resource other teams throughout the government, and the wider public sector.

Source: https://gov.uk/service-manual

Wikiguías (Mexico)

The Wikiguías are a series of recommendations for implementing standardised digital services on Mexico’s single government website gob.mx. The content consists of the framework for contributing to the single government website as well as the guidelines for implementing according to the provisions of Mexico’s Digital Services Standard.

Source: https://www.gob.mx/wikiguias

Governance, spending and assurance

The Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]) identifies that when it comes to digital government strategies countries should “establish effective organisational and governance frameworks to co-ordinate the implementation of the digital strategy within and across levels of government”. Such an approach is also valuable in the context of designing and delivering services and builds on the development of style guides and guidance. This section will consider the importance of business cases and budget thresholds, procurement and commissioning activity, and service standards and assurance processes in enabling the design and delivery of services.

Because government consists of hundreds of organisations delivering hundreds of services, it is impossible for one organisation to manage the design and delivery of all those things directly. As a result, it is essential that countries establish a clear definition of ‘good’ in respect of services and develop a credible approach to quality assurance. Such governance models need to be built around identifying clear coordination responsibilities complemented by visibility and controls covering spending and delivery activity associated with digital and technology interventions.

Business cases and budget thresholds

The Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]) identifies business cases as a critical element in securing the sustainability of digital government approaches through ensuring funding is available. Part of this exercise is to ensure a clear value proposition for all projects that can identify economic, social and political benefits as well as a process that involves all actors throughout government to ensure buy in and recognition of those benefits.

In the context of designing and delivering services such business case processes have important echoes of the need to carry out the research to understand a set of users, their needs and the potential ways in which government might respond. The business case and approval process needs to find ways to encourage experimentation by making funding available for research and prototype activities through a process that is lighter weight and less cumbersome than what might be expected for a full project implementation. Moreover, with an agile approach anticipating a continuous iteration of a service it is important for business case and funding processes to anticipate the need for delivery approaches that are continuously learning and as a result may pivot away from the original proposal having better understood the problem on an ongoing basis.

In the United Kingdom, a very early decision by the Government Digital Service was to make it possible for departments and agencies to carry out discovery and alpha activity without the need for a HM Treasury business case (HM Treasury and Government Finance Function, 2014[25]). In France, the team at beta.gouv.fr have developed a similar ‘pre-incubation’ phase where funding is available for teams to scope a problem and demonstrate the potential for a response without requiring a business case (beta.gouv.fr, n.d.[26]). The advantage of this approach to meeting well understood needs rather than spending time and energy on responding to assumed, but mistaken, needs can be seen in the way in which the United Kingdom developed GOV.UK Notify, as discussed in Box 2.14.