copy the linklink copied!Chapter 2. Improving learning outcomes and equity through student assessment

This chapter looks at how student assessment in Georgia contributes to student learning. In Georgia, the concept of assessment is understood as giving summative marks to students in order to judge their performance. Using classroom assessment to improve student learning is not widely practiced by teachers. This understanding and approach to assessment is also reflected in the country’s recently reformed high-stakes examinations system, which previously tested students in over a dozen subjects across two examinations spanning two grades. This environment motivated students and teachers to become focused on achieving high marks rather than on acquiring key skills. This chapter suggests that Georgia should re-focus student assessment so it is designed to help students learn. For this to occur, teachers and the community will need to be supported to fundamentally change their understanding of assessment and the examinations system will have to be reconfigured to reflect a more formative approach towards student assessment.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

copy the linklink copied!Introduction

The primary purposes of student assessment are to determine what students know and are capable of doing, to help students advance in their learning, and to assist students in making an informed decision on the next step in their education. In Georgia, a range of factors has prevented assessment from being used in this way. Not only do teachers lack a strong grasp of different assessment approaches, but both teachers and the public associate assessment primarily with grading and have little understanding of its educational value. Despite several efforts to improve assessment literacy, students and teachers still focus on the importance of numeric marks, even though those marks might not accurately represent what a student can do.

Adding to the summative pressure that students and teachers feel is Georgia’s examinations system, which, until recently, has required students to take 12 subject tests over two grades at the end of upper secondary education in order to graduate. A separate test, in many of the same subjects, needs to be taken in order to enrol in higher educational institutions. The intense attention paid to these examinations leads students and teachers to focus narrowly on examinations preparation, often at the expense of students’ individual learning needs.

This chapter discusses how Georgia can strengthen its student assessment system to provide greater educational value. It recommends that formative assessment be practiced more readily in classrooms so assessment is more strongly integrated into teachers’ instruction and used to support student learning. It also recommends that the examinations system be reviewed to create a more positive backwash on learning and more accurately assess students in the most important academic areas. Finally, the assessment literacy of students, parents and teachers needs to be developed to help embed reforms and improve national understanding that assessment if not just of learning, but for learning.

copy the linklink copied!Key features of an effective student assessment system

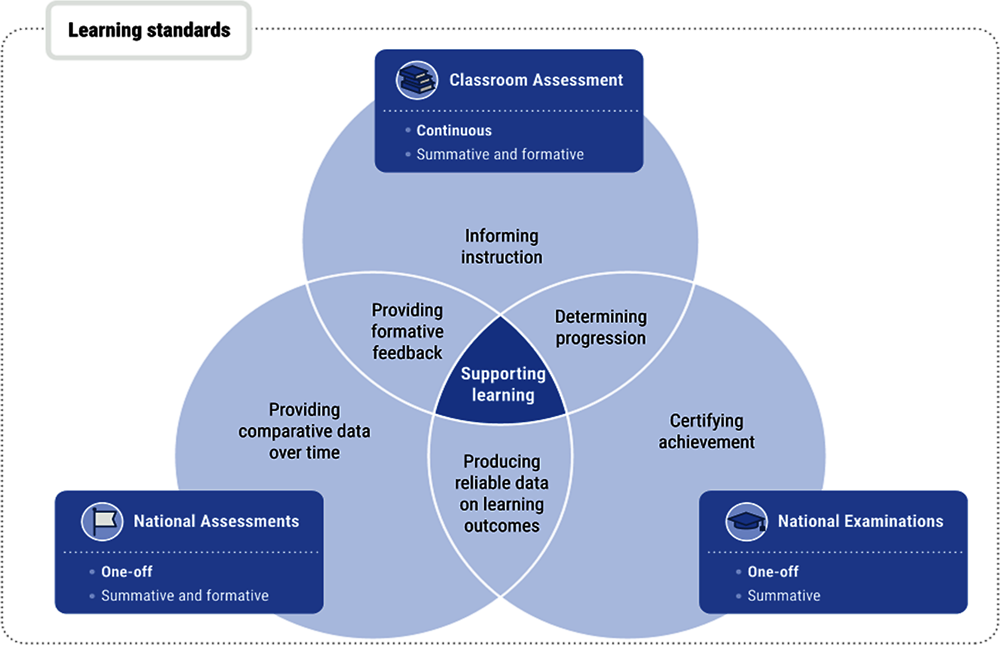

Student assessment refers to the processes and instruments that are used to evaluate student learning (see Figure 2.1). These include assessment by teachers, as part of school-based, classroom activities like daily observations and periodic quizzes, and though standardised examinations and assessments that are designed and graded outside schools.

Overall objectives and policy framework

At the centre of an effective policy framework for student assessment is the expectation that assessment supports student learning (OECD, 2013[1]). This expectation requires that national learning objectives be clear and widely understood. Regulations concerning assessment must orient teachers, schools and assessment developers on how to use assessment to support learning goals.

To these ends, effective assessment policy frameworks encourage a balanced use of summative and formative assessments, as well as a variety of assessment types (e.g. teacher observations, written classroom tests and standardised instruments). These measures help to monitor a range of student competencies and provide an appropriate balance of support, feedback and recognition to students to encourage them in improve their learning. Finally, effective assessment frameworks also include assurance mechanisms to regulate the quality of assessment instruments, in particular central, standardised assessments.

The curriculum and learning standards communicate what students are expected to know and be able to do

It is important to have common expected learning outcomes against which students are assessed to determine their level of learning and how improvement can be made (OECD, 2013[1]). Expectations for student learning can be documented and explained in several ways. Many countries define them as part of national learning standards. Others integrate them into their national curriculum frameworks (OECD, 2013[1]).

While most reference standards are organised according to student grade level, some countries are beginning to organise them according to competency levels (e.g. beginner and advanced), each of which can span several grades (New Zealand Ministry of Education, 2007[2]). This configuration allows for more individualised student instruction, but requires more training for teachers to properly understand and use the standards when assessing students.

Types and purposes of assessment

Assessments can generally be categorised into classroom assessments, national examinations and national assessments. Assessment has traditionally held a summative purpose, which aims to explain and document learning that has already occurred. Many countries are now also emphasising the importance of formative assessment, which aims to understand learning as it occurs in order to inform and improve subsequent instruction and learning (see Box 2.1) (OECD, 2013[1]). Formative assessment is now recognised to be a key part of the teaching and learning process and has been shown to have one of the most significant positive impacts on student achievement among all educational policy interventions (Black and Wiliam, 1998[3]).

-

Summative assessment – assessment of learning, summarises learning that has taken place, in order to record, mark or certify achievements.

-

Formative assessment – assessment for learning, identifies aspects of learning as they are still developing in order to shape instruction and improve subsequent learning. Formative assessment frequently takes place in the absence of marking.

For example, a teacher might ask students questions at the end of lesson to collect information on how far students have understood the content, and use the information to plan future teaching.

Source: (OECD, 2013[1]), Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment, OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264190658-en.

Classroom assessment

Among all types of assessment, classroom assessment has the greatest impact on student learning (Absolum et al., 2009[4]). Classroom assessment supports learning by regularly monitoring learning and progress; providing teachers with information to understand students’ learning needs and guide instruction; and helping students understand the next steps in their learning through the feedback their teachers provide.

Classroom assessments are administered by teachers in classrooms and can have both summative and formative purposes. Classroom assessments can be delivered through various formats, including closed multiple-choice questions, semi-constructed short answer questions and open-ended responses like essays or projects. Different assessment formats are needed for assessing different types of skills and subjects. In general, however, assessing complex competencies and higher-order skills requires the usage of more open-ended assessment tasks.

In recent decades, as most OECD countries have adopted more competency-based curricula, there has been a growing interest in performance-based assessments like experiments or projects. These types of assessments require students to mobilise a wider range of skills and knowledge and demonstrate more complex competencies like critical thinking and problem solving (OECD, 2013[1]). Encouraging and developing effective, reliable performance-based assessment can be challenging. OECD countries that have tried to promote this kind of assessment have found that teachers have required far more support than initially envisaged.

Effective classroom assessment requires the development of teachers’ assessment literacy

Assessment is now seen as an essential pedagogical skill. In order to use classroom assessment effectively, teachers need to understand how national learning expectations can be assessed – as well as the students’ trajectory towards reaching them ‒ through a variety of assessments. Teachers need to know what makes for a quality assessment – validity, reliability, fairness – and how to judge if an assessment meets these standards (see Box 2.2). Feedback is important for students’ future achievement, and teachers need to be skilled in providing constructive and precise feedback.

-

Validity – focuses on how appropriate an assessment is in relation to its objectives. A valid assessment measures what students are expected to know and learn as set out in the national curriculum.

-

Reliability – focuses on how consistent the assessment is measuring student learning. A reliable assessment produces similar results despite the context in which it is conducted, for example, across different classrooms or schools. Reliable assessments provide comparable results.

Source: (OECD, 2013[1]), Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment, OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264190658-en.

Many OECD countries are investing increasingly in the development of teachers’ assessment literacy, beginning in initial teacher education. In the past, teachers’ initial preparation in assessment was primarily theoretical, but countries are now trying to make it more practical, for example, by emphasising opportunities for hands-on learning where teachers can develop and use different assessments. Countries encourage initial teacher education providers to make this shift by incorporating standards on assessment in programme accreditation requirements and in the expectations for new teachers in national teacher standards.

It is essential that teachers’ initial preparation on assessment be strengthened through on-going, in-school development. Changing the culture of assessment in schools – especially introducing more formative approaches and performance-based assessments, and using summative assessments more effectively – requires significant and sustained support for teachers. Continuous professional development such as training on assessment and more collaborative opportunities when teachers can share effective assessment approaches provides vital encouragement. Pedagogical school leaders also play an essential role in establishing a collaborative culture of professional enquiry and learning on assessment.

Finally, countries need to invest significantly in practical resources to ensure that learning expectations defined in national documents become a central assessment reference for teachers and students in the classroom. These resources include rubrics that set out assessment criteria, assessment examples aligned to national standards and marked examples of student work. Increasingly, countries make these resources available on line through interactive platforms that enable teachers to engage in the development of standards, which facilitates a greater feeling of ownership over the resources and makes it more likely that they will be used.

National examinations

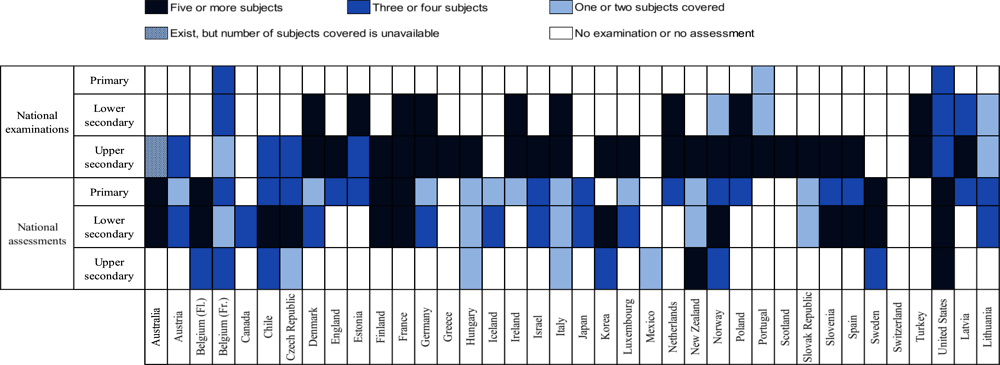

National examinations are standardised assessments developed at the national or state level with formal consequences for students. The vast majority of OECD countries (31) now have exit examinations at the end of upper secondary to certify student achievement and/or for selection into tertiary education, reflecting rising expectations in terms of student attainment as well as the importance of transparent systems for determining access to limited further education opportunities (see Figure 2.2). National examinations are becoming less common at other transition points, as countries seek to remove barriers to progression and reduce early tracking. Among those OECD countries (approximately half) who continue to use national examinations to inform programme and/or school choice for entrants to upper secondary education, few rely solely or even primarily on the results of examinations to determine a student’s next steps.

While classroom assessment is the most important assessment for learning, evidence shows that the pace of learning slows down without external benchmarks like examinations. National examinations signal student achievement and in many countries carry high stakes for students’ future education and career options, which can help to motivate students to apply themselves (Bishop, 1999[7]). They are also more reliable than classroom assessment and less susceptible to bias and other subjective pressures, making them a more objective and arguably fairer basis for taking decisions when opportunities are constrained, such as access to university or high-demand schools.

However, there are limitations related to the use of examinations. For instance, they can only provide a limited snapshot of student learning based on performance in one-off, time-pressured exercises. To address this concern, most OECD countries complement examination data with classroom assessment information, teachers’ views, student personal statements, interviews and extracurricular activities to determine educational pathways into upper secondary and tertiary education.

Another concern is that the high stakes of examinations can distort teaching and learning. If examinations are not aligned with the curriculum, teachers might feel compelled to dedicate excessive classroom time to examination preparation instead of following the curriculum. Similarly, students can spend significant time outside the classroom preparing for examinations through private tutoring. To avoid this situation, it is important that items on examinations are a valid assessment of the curriculum’s learning expectations and encourage high quality learning across a range of competencies.

Most OECD countries are taking measures to address the negative impact that the pressure of examinations can have on student well-being, attitudes and approaches to learning. For example, Korea has introduced a test-free semester system in lower secondary education, with activities like career development and physical education to develop students’ life skills and reduce stress (OECD, 2016[8]).

National assessments

National assessments provide reliable information on student learning, without any consequences for student progression. Across the OECD, the vast majority of countries (30) have national assessments to provide reliable data on student learning outcomes that is comparative across different groups of students and over time (see Figure 2.2). The main purpose of a national assessment is system monitoring and, for this reason, national assessments provide essential information for system evaluation (see chapter 5).

Countries might also use national assessments for more explicit improvement purposes, such as to ensure that students are meeting national achievement standards and identify learning gaps in need of further support. In these cases, providing detailed feedback to teachers and schools on common problems and effective responses is critical.

Many OECD countries also use national assessments for school accountability purposes, though there is considerable variation in how much weight is given to the data. This is because student learning is influenced by a wide range of factors beyond a school or teacher’s influence – such as their prior learning, motivation, ability and family background (OECD, 2013[1]).

National assessment agencies

Developing high quality national examinations and assessments requires a range of assessment expertise in fields such as psychometrics and statistics. Many OECD countries have created government agencies for examinations and assessments where this expertise is concentrated. Creating a separate organisation with stable funding and adequate resources also helps to ensure independence and integrity, which is especially important for high-stakes national examinations.

copy the linklink copied!Student assessment in Georgia

Traditionally, the Georgian education system has understood assessment of students as judgements of their performance represented by a numeric grade. However, as demonstrated in national curriculum reforms and in the Unified Strategy for Education and Science 2017-21 (Unified Strategy), Georgia recognises the need to develop more strongly the educational value of assessment and strengthen the capacity of teachers to use assessment more effectively to support student learning.

Nevertheless, evidence suggests that there is considerable divergence between the intent of Georgia’s vision of assessment and what occurs in practice. Classroom assessment is still primarily used to make summative judgements about students, rather than to help them develop. While national examinations are widely regarded as trustworthy, the high stakes consequences associated with them create pressure for students to attend private tutoring and, similarly, encourage teachers to adapt their instruction to meet exam demands. In addition, examinations do not provide students with reliable feedback on their learning. Most students passed the upper secondary exit examination, although international assessments show that the majority are not mastering basic competencies (OECD, 2016[9]).

Types of assessment practices

Table 2.1 illustrates the different types of assessment practices found in Georgia. These practices will be discussed throughout this section.

Overall objectives and policy framework

Georgia has a well-established national curriculum that has undergone several revisions

In 2005, Georgia introduced the first national curriculum since independence, which determined academic content, established desired learning outcomes and distributed teaching hours across the week for all subjects and grades (MoESCS, 2018[10]). A revised curriculum was introduced in 2011 and another in 2018-19. Changes introduced by the third generation curriculum currently apply only to primary education (Grades 1-6). They will be applied to basic education (Grades 7-9) in 2019-2020.

Changes implemented in the 2011 and 2018-19 versions of the curriculum emphasise a more holistic approach to learning (MoESCS, 2016[12]). Education is seen not only as academic in nature, but also as a means to build student’s social and emotional skills and to develop critical, creative and responsible citizens (MoESCS, n.d.[14]). For example, curriculum goals for general education include that students sustain healthy lifestyle habits, understand and appreciate cultural diversity and are able to make independent decisions.

Georgia’s learning standards emphasise competences

Georgia has developed learning standards as part of the national curriculum. Similar to many OECD countries’ (Peterson et al., 2018[15]), Georgia’s learning standards emphasise the development of cognitive and non-cognitive competencies in real-life contexts (e.g. expressing spatial information using different resources) rather than acquiring factual knowledge (e.g. memorising the capitol of a country). The standards are organised according to subject and student grade level (recently changed to student stages).

Georgia is moving towards a stage-based curriculum, but understanding of this change varies

Unlike previous versions, the 2018-19 curriculum is organised around stages, meaning that there is one set of expected learning outcomes for Grades 1-6 and another for 7-9 (MoESCS, 2018[10]). This significant and innovative development recognises that students in the same grade might differ in acquired competences and allows teachers and schools to exercise greater flexibility in adapting the curriculum to students’ individual needs, which can lead to improved student outcomes (Dumont, Istance and Benavides, 2010[16]).

However, in countries that have transitioned to similarly structured curricula, such as New Zealand and Australia, teachers have generally had a very strong understanding of student progression and assessment. They have also been provided with immense support to implement the new curricula. In Georgia, there is concern that the rationale behind this kind of curriculum reform might not be well understood by all stakeholders. Interviews conducted by the OECD review team revealed that teachers and principals found that proposed changes to the curriculum were unclear and that many were not sure what a stage-based learning outcome was. Some were completely unaware that the reform was occurring.

Classroom assessment

Formative assessment practices are encouraged by policy but are not widely used

Like many OECD countries, Georgia has made efforts to integrate more formative assessment practices into its classrooms. The national curriculum, for example, mandates that teachers provide only oral or written feedback and not summative marks until grade 5 (MoESCS, 2016[12]). The government has also undertaken projects in partnership with international donors to develop the capacity of teachers to employ more formative assessment methods. This includes the development of 13 formative assessment tools, such as the E-Assess, an online diagnostic assessment software, under the Georgia Primary Education Project (G-PriEd). Teachers and the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport (MoESCS) staff reported to the OECD review team that they considered E-Assess to be very useful and customisable, helping them to better adapt instruction to student needs (USAID, 2018[17]).

Despite these significant efforts, formative assessment is not widely understood or practiced in Georgian classrooms. OECD interviews suggest that teachers tend to interpret formative assessment as simply providing a description of student progress instead of a numeric mark, as opposed to using assessment information for improving student learning. As part of a survey administered for this review, 43% of teachers indicated that they “never or almost never” or only “a few times” provide written feedback on student work, further suggesting that key formative assessment activities are not being practiced.

Teachers are not effectively prepared to assess students

Teachers in Georgia are not always trained in how to properly assess students. Internationally, 13% of teachers across 31 jurisdictions surveyed in the Teacher and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 indicated that they have a high developmental need in student evaluation and assessment practices. In Georgia, over 25% of teachers indicated a need in this area (OECD, 2019[18]). A large reason that this need exists in Georgia is the lack of training that teachers receive in assessment during initial teacher preparation (ITP) programmes. Many of these programmes have low entrance requirements and are not regarded as particularly rigorous. In fact, because of the age of the Georgian teacher population, almost one-third did not receive any ITP as they entered the profession before formal preparation was introduced (see chapter 3 for a more detailed discussion of ITP).

Student marks are still the focus of classroom assessment but are not reliable

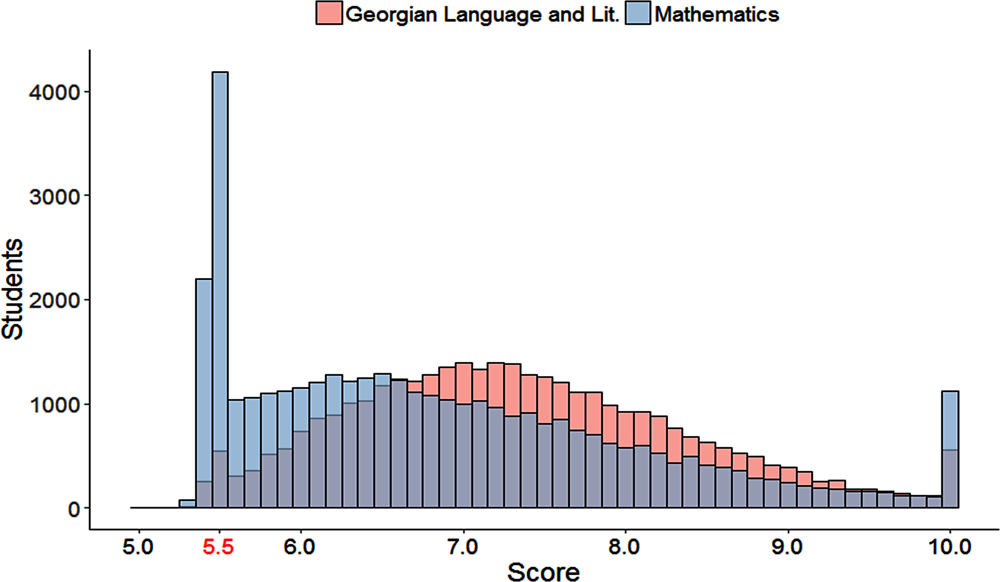

In grades 1 through 4, and partially in grade 5, students only receive descriptive feedback about their achievements. Starting in grade 5, students receive summative marks on a scale of one (lowest) to 10 (highest). Marks of one through four are considered unsatisfactory while all others are passing marks. Students who receive an unsatisfactory mark must repeat that grade, but in practice this occurs very rarely. According to PISA 2015, only 2% of 15 year-old students in the country have ever repeated a grade, compared to 12% on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2016[19]).

In Georgia, students’ summative marks represent the focal point of classroom assessment and the emphasis on using marks to label students distracts from focusing on student learning. A G-PriEd report found that teachers were reticent to use assessment methods that did not produce numeric grades and did not see the value of checking a student’s level of understanding (USAID, 2018[17]). Conversations with university faculty confirmed that classroom instruction is often oriented towards achieving certain marks and understanding the curriculum is not a primary concern of teachers. These persons suggested that being assessed in this manner inhibits students from embracing the types of autonomous learning approaches that are critical to success at higher levels of education.

Despite being the focus of classroom assessment, the marks that teachers provide are not reliable measures of student achievement. Almost all students receive passing marks, though national results on PISA indicate that many students actually struggle to reach baseline levels of competency. One reason for the lack of reliable marking is that teachers lack resources that can help them gauge student achievement with respect to the national learning standards. Another is that societal focus on grades and ranking puts pressure on teachers to provide high marks, even if students do not demonstrate a minimum level of performance.

Reporting of classroom assessment is inconsistent

How student marks are reported in Georgia is not always consistent. Schools are required to issue a report card to document student progress, but Georgia does not have a national report card template that schools should follow. As a result, report cards are not standardised across schools and contain different information. This is unfair for students, who receive different amounts and types of information about their own learning. It can also create difficulties when students change schools as a student’s teachers might not be able to interpret the student’s previous report cards and understand where the student is in their learning. Georgia also lacks national guidelines around how students’ performance should be communicated to parents, creating a situation in which some parents rarely see evidence of their students’ performance (MoESCS, 2018[10]).

National assessments

Several national assessments are conducted by NAEC using external funding

Since 2015, the National Assessment and Examinations Centre (NAEC) has conducted regular sample-based student assessments for maths and sciences in grade 9 and a census-based assessment for Georgian as a second language in non-Georgian speaking schools in grade 7 (MoESCS, 2018[10]). The three assessments include multiple-choice items and open-ended questions. The results of these are not publicly disclosed and are only made accessible to NAEC staff for the purposes of informing policy-making (MoESCS, 2018[10]).

Georgia’s national assessments have been largely funded by the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) under an initiative to improve education in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) subjects. MCC’s funding is phasing out starting in 2019. Georgia has started developing a long-term strategy to continue administering national assessments (see chapter 5) and is considering developing standardised diagnostic assessments in primary and secondary school. These latter assessments would not focus on system monitoring, but on helping teachers identify their students’ strengths and weaknesses so they can better tailor their instruction.

National examinations

Georgia administers two national examinations, one of which, the Secondary Graduation Examination (SGE), was recently eliminated in 2019. The SGE certified students at the end of upper secondary education, while the Unified Entry Examination (UEE) selects students for entrance into tertiary education. These examinations are outlined in Table 2.2.

From 2011 to 2019 graduation from upper secondary education was based on results in a computer adaptive test

The SGE was introduced in 2011 to improve student attendance (absenteeism in upper secondary education was previously a concern) and increase school accountability (Bakker, 2014[20]). Given the large number of subjects assessed (eight), the SGE was taken by students over the course of two years. At the end of grade 11, students were tested in geography, biology, chemistry and physics. In grade 12, they took tests in their mother tongue, history, mathematics and a foreign language.

The SGE was administered using computer adaptive testing (CAT) (Bakker, 2014[20]). Through an item response theory model, students were presented with questions that varied in difficulty depending upon their previous responses. Students continued with the test until a student’s level of achievement could be determined at a specified level of statistical certainty, meaning that different students did not answer the same questions, nor did they spend the same amount of time taking each test. All questions were multiple-choice.

Passing the SGE in all subjects was necessary to graduate from upper secondary school. Roughly eight out of ten test-takers were successful, although passing rates varied significantly across the country (World Bank, 2014[21]), from over 90% in Tbilisi to 44% in Marneuli (Kvemo Kartli).

The SGE was considered trustworthy, but did not adequately certify student achievement in relation to the curriculum

The CAT format of the SGE helped instil trust in the examination. Because results were returned to students immediately, there was no concern about the integrity of the results and the exam did help to improve student attendance because attending class to prepare for the exam served as significant incentive. From an international perspective, however, using the CAT format for an upper secondary exit examination is unusual. The format does not guarantee that students must demonstrate knowledge and skills across the breadth of the curriculum because it classifies all questions from the same subject along a single continuum of difficulty, regardless of competence area. This was problematic because it meant that students were certified without necessarily showing that they have acquired basic understanding knowledge of the entire curriculum.

Since 2005 selection into higher education has been based on a standardised examination

The UEE, established in 2005, is a standardised examination used for selection into higher education institutions and scholarship allocation (NAEC, n.d.[22]). After a recent change in 2019, students must take three compulsory subjects at the end of grade 12 - Georgian language, a foreign language and either mathematics or history - along with an elective subject. This elective subject is selected according to the requirements of university programs to which the students wish to apply.

Starting in 2016, the UEE questions were presented to students electronically, though students still complete their answers on paper. Questions include multiple-choice and open-ended items. The tests are not strictly based on the curriculum. The UEE is only offered in Georgian, with the exception of the elective general aptitude test, which is offered in ethnic minority languages. Students from ethnic minority schools who take the UEE only take this test and, if successful, then enrol in a university preparation program. Upon completing the preparation program, they begin university studies.

To create items for the UEE, NAEC first sends an examination programme to MoESCS for review. Part of the approval process is determining the extent to which it is aligned with the curriculum. Previously, this part of the review was performed by the curriculum department, which was recently eliminated. It is unclear who performs this review now. After approval is granted by MoESCS, NAEC convenes subject matter groups to begin writing items. Despite this review process, interviews with Ministry officials, university faculty and teachers all suggested that the final items for UEE are not always closely aligned with the curriculum.

The UEE strengthened integrity in higher education admission

In the 1990s and early 2000s, university entrance requirements were not standardised across Georgian higher education institutions. This created space for practices such as bribing officials in order to influence student selection, which hindered equity of access and the capacity of universities to meet expected academic standards (Orkodashvili, 2012[23]).

In 2005, amidst government reform to tackle corruption, Georgia introduced the UEE. The examination was applied to all public institutions and measures were put in place to prevent cheating (test-takers’ names were coded for anonymity and administrations were under camera surveillance). Stakeholders acknowledged that this examination had a key role in increasing transparency and fighting corruption in university admission in Georgia in the following decade. Moreover, it is seen to have improved the participation of ethnic minorities in higher education and fostered greater social cohesion (Orkodashvili, 2012[23]).

Numerous high-stakes examinations had unintended negative effects

High-stakes examinations can have the consequence of creating a backwash effect, which pressures teachers to “teach to the test”, as opposed to focusing on individual student learning, and pressures students to focus primarily on preparing for the exams by seeking tutoring opportunities (OECD, 2013[1]). These effects are particularly pronounced in Georgia. Research shows that 60% of Georgian students enrolled in grade 12 in 2014 registered for private tutoring (World Bank, 2014[21]) and 39% of households with a school-age child in 2016 had a private tutor (Bregvadze, 2012[24]). Georgia’s large private-tutoring sector is also an equity-related concern. Nearly nine in ten advantaged students attend private tutoring, compared to only 36% of their disadvantaged peers (World Bank, 2014[21]).

Several factors contribute to these backwash effects. The large number of subjects tested by the SGE created significant pressure and students who wished to attend university had to take two examinations. Furthermore, because final UEE items are not always strictly aligned with the curriculum, students are unable to prepare for it through regular classroom instruction, which further motivates them to seek private tutoring.

Major changes to examinations were announced in 2019

In 2019, MoESCS announced that significant changes would be made to Georgia’s examinations. In particular, the SGE would be eliminated due to the backwash effects it was exerting on students, teachers and schools. The implementation of this policy was immediate, with graduating students in 2019 being the last cohort to take the SGE. The UEE was maintained but, as mentioned previously, its required subjects were changed to make it more flexible. While discussions have occurred regarding what should replace the SGE, no decisions have been made. In the meantime, certification from upper secondary education will be based on student grades and, depending upon school-level decision-making, internal examinations. There have been preliminary discussions about NAEC strongly supporting schools in developing these internal examinations.

VET upper secondary schools use an examination to select students

The Vocational Education and Training (VET) sector in Georgia enrols less than 2% of upper secondary students (OECD, 2016[9]). A particular concern with the sector is what has been termed “dead ends,” in which students who complete VET upper secondary education are unable to enrol in general education tertiary programmes.

While underdeveloped, there is still demand for VET education and demand often exceeds the very limited supply. In response, NAEC began administering a VET admissions examination in 2013 to select students into in public institutions (passing an examination is not necessary for private VET schools, unless required by individual institutions). The exam assesses Georgian language and literature, mathematics and general aptitude. Students who achieve a 25% of the exam have their student fees fully paid for by the government (Livny, Eric; Stern, Paul, Maridashvili, Tamta; Tandilashvili, 2018[25]).

National student assessment agencies

NAEC oversees examinations and assessments in Georgia

The National Assessment and Examinations Centre (NAEC), established in 2002, was responsible for developing and administering the SGE and currently administers the UEE, VET examination and the national assessments in grades 7 and 9. NAEC also facilitates Georgia’s participation in international assessments, such as PIRLS, TIMSS and PISA.

NAEC is known for its strong technical capacity. Its team of over 200 people (as of early 2018) includes experts in statistics, psychometrics and information technology. Interviews with national stakeholders show that NAEC is recognised in Georgia as a trusted and competent institution, given the credibility of the administration of the examinations as well as the timeliness with which SGE results were released (Bakker, 2014[20]). Reports suggest that the success of the SGE’s introduction was partly due to its association with NAEC and the credibility of the institution (Bakker, 2014[20]). In 2018, changes in NAEC’s leadership led to some staff turnover and, as a result, some technical capacity is being rebuilt.

Teacher Professional Development Centre supports teachers’ assessment literacy

The Teacher Professional Development Centre (TPDC) is a body at arms-length from the Ministry and is responsible for developing teachers in Georgia. Included in its remit is developing teachers’ assessment capacity. To this end, it has provided a professional development module on learning and assessment strategies for over 7 000 teachers between 2016 and 2018 and works closely with programmes such as G-PriEd to further develop teachers (TPDC, 2018[26]).

copy the linklink copied!Policy issues

Georgia has made efforts to strengthen the use of assessment to improve student learning, though the results of these efforts have been mixed. This review recommends several initiatives to achieve greater progress in this area. First, MoESCS should link teachers’ use of formative assessment to the curriculum in order to encourage teachers to assess students for the purposes of improvement. The OECD also suggests that Georgia move towards a one-examination system that will both certify completion from upper secondary education and select students to enter universities. This would help reduce the negative backwash effects that Georgia has experienced in the past while introducing a flexible examinations structure that can assess students from vocational and general education tracks. Finally, the assessment literacy of educators and the public should be improved through the development of digital resources so all stakeholders are aware of and embrace the goals of the reforms that Georgia is enacting.

copy the linklink copied!Policy issue 2.1. Enhancing the educational value and use of teachers’ classroom assessment

In addition to improving student outcomes, effective classroom assessment, in particular formative, can positively affect students’ attitudes towards learning and their engagement with school. Georgia has made considerable strides to embed formative assessment practices into classrooms, but the impact has been less than hoped for due to a lack of alignment between assessment and the curriculum, and inadequate resourcing to support teachers in their efforts. In order for classroom assessment to better support learning, it is imperative that efforts to embed formative assessment receive more support.

Additionally, assessment in Georgia should exert less pressure on teaching and learning process. This can be accomplished through reviewing the country’s marking system so it is less frequent, but more accurate and reliable. Lastly, there is a need to give students and their teachers more information about the progress that students are making so their instruction can be tailored specifically for their needs. This can be achieved by creating tools and procedures that systematically document what students are able to do as they advance through different levels of the education system.

Recommendation 2.1.1. Make formative assessment a central focus of teacher practice

Embedding formative assessment practices is challenging and attempted interventions in most countries have yielded varying results (Black and Wiliam, 1998[27]; Assessment Reform Group, 1999[28]). Obstacles that countries have encountered, and that Georgia is encountering, include a lack of alignment between the curriculum and assessment practice and a lack of support for teachers who are trying to implement changes in their classroom.

On the other hand, successfully embedding formative assessment practices requires that its practice be explicitly encouraged in high-level materials, such as the curriculum, which helps communicate its importance and hold teachers accountable for their use of it. Teachers must also be asked to perform tasks that make using formative assessment seem feasible and valuable, such as introducing student portfolios, and be provided with the necessary guidance to help them do so.

Use the new curriculum as a policy lever to encourage the use of formative assessment

The recent introduction of a new curriculum represents an opportunity to engage teachers in new pedagogical methods, especially those related to formative assessment. Teachers need motivation to change their practices and confidence to believe that they can do it. A demanding and modern curriculum can help make the case for formative assessment and act as a catalyst to support teachers in changing their practices.

Introducing a new curriculum necessitates addressing several aspects of instruction, such as how to help students develop different skills and how to assess if students have acquired those skills. It is important that these instructional aspects be integrated into the curriculum, in relation to its content and expected outcomes, as opposed to being add-ons. This type of integration weaves an assessment structure throughout the curriculum and reinforces the idea that formative assessment is inextricably tied to student learning and that its practice is mandatory. Box 2.3 explains how Norway explicitly integrates formative assessment into its national curriculum.

Georgia can similarly build in formative assessment into the curriculum by, for example, specifying what types of feedback teachers should provide (see Table 2.3). This information could be adapted and expressed in curricula for different domains, units of study and stages of education (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2007[29]). Importantly, the curriculum and accompanying materials then need to be made available to all teachers. An online portal would be an ideal solution so teachers can access the curriculum and related instructional resources in one place (Recommendation 2.2.1).

In Norway, the curriculum for general upper secondary education is underpinned by an explicit assessment structure. The text of the curriculum specifies that:

-

Students shall be given six-month evaluations for each subject and for order and conduct. These might be exams, written tasks and practical assessment depending on the subject.

-

Continuous classroom assessment and feedback be given to the student using a range of formative assessments including observations, peer assessment and weekly reviews.

-

Student self-assessment is a part of regular formative assessment. The regulations require the student to actively participate in the assessment of his or her own work, abilities and academic development.

-

Follow-up of results from different types of tests occur through discussion with the teacher and parents.

These specifications, contained within the curriculum itself, help to embed the practices into classrooms, as teachers who are using the curriculum must also use these activities.

Source: Eurydice (n.d.[31]), Assessment in General Upper Secondary Education, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/assessment-general-upper-secondary-education-39_en (accessed on 3 January 2019).

Consider the introduction of portfolio assessment in the curriculum to anchor more formative assessment practices in the classroom

As well as establishing an assessment structure as part of the curriculum, it is important to give teachers guided tasks that they can use in their classrooms to embed key formative assessment practices. There are several ways this can be done, but a particularly effective method is the use of student portfolios, which are collections of a student’s selected work that demonstrates evidence of the student’s progress and learning (Dysthe and Engelsen, 2004[32]; Messick, 1994[33]; Paulson, Paulson and Meyeter, 1991[34]). Using student portfolios is appropriate in Georgia’s educational context because the country wishes to focus student assessment on providing feedback to individual students in order to improve their learning. Using student portfolios requires that teachers continuously provide feedback to students and that students and teachers reflect upon the portfolios to determine what the student’s strengths and weaknesses are.

Introducing student portfolios in Georgia will require strong support to teachers so they understand not only on how to use them, but also why they matter. As part of the survey conducted for this review, teachers were asked to what extent they believe certain methods accurately assess the performance of their students. Student portfolios were considered to be less accurate than question-and-answer, oral presentations and open-ended test questions. These data suggest that teachers in Georgia are not aware of how different methods of assessment can help students learn. They will need to gain this awareness in order to successfully use new practices.

There are several steps that Georgia can take to embed the use of student portfolios. An essential starting point would be to include examples of age and subject-appropriate portfolios as part of the new curriculum. These materials should be made available online so all teachers can access them (see Recommendation 2.2.1). They should also be accompanied with expectations as to when they might be undertaken and submitted, such as at the end of a grading period. Requiring that the portfolio be submitted at this point would help to ground summative judgements in a wider range of evidence and ensure that teachers and students take the portfolio exercise seriously. During regular reviews of portfolio materials, however, teachers should focus on an individual student’s strengths and challenges in relation to standards, rather than making a judgement of their performance.

Georgia will also need to build teachers’ confidence that they can successfully use student portfolios in their own classrooms. In-school support can help accomplish this. As part of the regular, school-based appraisal processes that this review recommends in chapter 3, teachers should be provided with feedback on their use of student portfolios. The feedback would not only help them improve their portfolio-related practices, but also help ensure that all make an effort to use those practices in the first place.

While portfolios can be used at all levels of education, in Georgia they would be particularly helpful in grades 8 and 9 as they could act as evidence to help inform a student’s decision about entering a general or vocational programme (see also Recommendation 2.1.3). If, for example, a student selects material for his/her portfolio that demonstrates an inclination towards a certain vocational field, a teacher can discuss with the student if that would be an appropriate path.

An example of this kind of practice exists in Finland, where students receive on-going, formal feedback about their performance throughout their schooling, which then feeds into the decisions that they make regarding future choices. Students might, based on the feedback they receive, enter a vocational stream, the workforce or higher education (Eurydice, n.d.[35]; Finnish National Agency for Education, n.d.[36]).

Recommendation 2.1.2. Reduce the pressure around summative marking and make it more educationally meaningful

Summative assessment is an important part of classroom assessment. However, in Georgia, it weighs too heavily on students and teachers. This not only displaces formative practices, which have a greater proven impact on learning (Black and Wiliam, 1998[3]), but can also distort approaches to teaching and learning. Specifically, a heavy focus on summative assessment can:

-

lead teachers to disregard the subtle and explicit changes that happen as students learn

-

compel teachers to label students as being of a particular level of capacity

-

make students believe that their capabilities are fixed and erode their motivation to learn (OECD, 2013[1]).

In order to orient teachers and students to focus on student learning and not student marks, Georgia will have to lessen the frequency with which some teachers are conferring marks. Furthermore, students should also receive information about their learning from external assessment sources, such as standardised assessments. This would give students a broader indication about their progress and give teachers a reliable reference point with which to evaluate their own marking.

Discontinue the practice of continuous log grading

In Georgia, teachers are assigning class work, homework and a range of other tests and recording the grades continually. Though not mandatory, some teachers even report a numeric grade for every child for every lesson, which requires a large investment of time. These grades provide a snapshot summary of student activities at one point in time but do not help teachers understand how their students are learning. Furthermore, these grades do not help the students establish where they are in their learning and, crucially, where they need to go (Stobart, 2008[37]). Discontinuing the practice of daily grading would give teachers more time to dedicate to other activities and reduce the pressure that students feel around receiving a judgement every day.

Help teachers align their summative marking with the new curriculum

The introduction of the new curriculum presents opportunities for embedding formative assessment, but also challenges for determining students’ summative marks. Teachers must understand not only how to discern accurately student learning according to the curriculum, but also how grades correspond to students’ levels of learning.

A substantial amount of training and resources (see Recommendation 2.2.1) will need to be provided for teachers to assess students properly against the curriculum. It will be important that this training engage teachers in the definition of grading criteria so they are not simply told what the criteria are, but are involved in their development. This is important because involving teachers in education reforms increases their “buy in” and the likelihood that the reforms are sustained (Barber, 2009[38]; Persson, 2016[39]).

Moreover, teachers’ judgements will need consistent calibration with respect to their grading. However, the review team was told that teachers rarely meet systematically to talk about examples of marked student work or how each teacher awards grades. Georgia should thus give more support to schools to introduce school-based moderation, which provides time for teachers to convene to discuss how they mark student work and determine student learning (OECD, 2013[1]). Chapter 3 of this review mentions that there is excess time in teachers’ schedules – MoESCS can require schools to use this time to conduct moderation. During these meetings, teachers should come together to learn from each other’s practices, such as using student portfolios.

Providing adequate resources to teachers will be critical to help them align their marking and understand student progress with respect to the standards. Countries that wish to reform their teachers’ assessment practices have invested heavily in resourcing. Box 2.4 describes how the state of Rhode Island in the United States created an assessment toolkit to help its teachers decide on grading criteria and moderate their scoring of student work. Georgia, through TPDC, should consider producing similar materials (e.g. examples of student portfolios) to assist teachers with their marking.

The Rhode Island Department of Education has created a comprehensive assessment toolkit (Rhode Island Department of Education, 2012[40]) to assist teachers in assessing students against the expected student learning outcomes. The toolkit contains the following materials:

-

Guidance on developing and selecting quality assessments – This document explains different types and purposes of assessments and the advantages and challenges of different assessments (Rhode Island Department of Education, 2012[41]).

-

Using baseline data – This guide clarifies how baseline data can be collected with respect to the expected student learning outcomes and also includes a worksheet that teachers can use when analysing baseline data (Rhode Island Department of Education, 2012[42]).

-

Assessment review tool – This tool provides a framework to teachers that can be used to evaluate different assessments. It asks educators to consider assessment type, alignment, scoring, administration and bias. This tool is intended to be used by a team of teachers, perhaps organised according to grade or subject (Rhode Island Department of Education, 2012[43]).

-

Student work analysis protocol – This tool helps teachers examine student work in order to understand what students know and are can do according to the student learning outcomes. With this information, the protocol then helps teachers make instructional decisions to improve student learning (Rhode Island Department of Education, 2012[44]).

-

Calibration protocol for scoring student work – This document is intended for teams of teachers and is designed to be used by each member to arrive at similar conclusions. It is accompanied by several samples of student work from different subjects (Rhode Island Department of Education, 2012[45]).

Recommendation 2.1.3. Systematically record assessment results in order to track student progress and inform key decisions

Recording student progress is an important component of assessment. The Department of Education in the United Kingdom defines student records as information about pupils that are processed by the state education sector, including academic work, extracurricular pursuits, records of specific needs and records of behaviour and attendance (Department of Education, 2015[46]). Accurate records provide a global view of student performance and help educators and parents make decisions about how individual students should be educated, particularly when students transfer between schools (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.[47]).

In Georgia, records about student learning, particularly descriptive feedback, are not kept in a standardised manner. Schools are not issued a national report card template to follow nor are they given instructions on how to disseminate the report cards to parents. As records of student learning are not uniform across schools, they cannot be easily entered into a central data system. These circumstances can lead to students, particularly those from vulnerable populations, being left behind without teachers and parents being aware.

Create a common report card template and procedures around dissemination

Internationally, student record-keeping tends to be explicitly prescribed. In the United Kingdom, legal regulations require that student progress be reported annually and that specific information about their children be included in the information that parents receive (Department of Education, 2015[48]). The Finnish National Agency for Education requires that students receive progress reports at least once a year based on the results of continuous assessments that are administered by teachers (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2017[49]).

Creating a common report card template, specifying what should be included in them and requiring that the report cards be disseminated would ensure that Georgian schools are recording the most vital information about student learning and that parents are made aware of their students’ progress. Importantly, the report card template should make space for, and require, descriptive, formative feedback, especially in grades 1 through 4 (and partially in grade 5), during which students only receive descriptive feedback. This information can help students and parents understand where a student is in their learning more effectively than stand-alone, numeric grades.

Integrate the standardised report card template into the EMIS E-Journal

EMIS has developed an E-Journal in which students’ grades are recorded and can be viewed online by themselves, their parents and their teachers. E-Journal has the advantage of transferability. As the grades are stored in the EMIS database, they can be retrieved when students switch schools and/or teachers. Currently, E-Journal is used by private schools in Georgia and its delivery is being planned for public schools.

With a standardised report card template, student data in E-Journal could then reflect what appears on their report cards, including the descriptive, formative feedback. This information would then be accessible to, and could be used by, a student’s teachers in each school that the student attends. In time, the E-Journal could replace the need for physical report cards, which would allow students and parents to more easily and quickly monitor student progress over their academic career.

Use student assessment information to support vulnerable students

Accurate and complete student records can be helpful in making learning risks more visible. Without consistent record-keeping, struggling students might not be identified as such and are vulnerable to becoming “lost,” especially as they change teachers and/or schools (OECD, 2012[50]). Such information would be particularly useful to principals, who need an efficient way of identifying students who need assistance. For example, a principal might not know what is happening in every classroom every day, but they can review student records to identify at-risk students, bring together teachers around the student’s report cards and together identify a strategy to help the student.

Internationally, several countries rely on student records to feed into early warnings systems, which analyse information about students’ attendance, learning progress and other factors to identify students who might be at risk of dropping out or under-performing (European Commission, 2013[51]; Borgonovi, Ferrara and Maghnouj, 2018[52]). With consistent student record keeping, Georgia can begin implementing such systems, which would help identify at-risk students and address equity gaps in student outcomes.

Develop and record external measures of student performance at key moments to inform decision-making

At present, most students in Georgia complete primary and secondary education without any external measure of their performance except for the UEE in grade 12. This configuration carries many risks. For example, students do not receive reliable indicators on their learning; teacher bias has an outsized effect on student assessment with no moderating measure; and school marks might make students think they have mastered a domain when, in fact, there is still much they can learn (OECD, 2013[1]). These concerns are heightened in Georgia because many students remain in the same school and are assessed by a limited number of teachers.

Over time, improving the quality of teacher’s assessment judgements will help to mitigate some of these risks. Nevertheless, it is equally important to introduce external measures at key points in order to help moderate teachers’ judgements. Many OECD countries regularly administer national assessments, which help improve the reliability of teacher judgements in relation to national standards (OECD, 2015[6]). As Georgia has developed national assessment capacity through its current national examinations system and through partnership with MCC, the OECD recommends that Georgia administer standardised, full-cohort assessments at key stages in a student’s education to help assess student performance (see chapter 5 for more details about the national assessment).

Consider making the external assessment in grade 9 (or grade 10 if compulsory education is extended) a certification examination

Though testing in early years would not be associated with stakes, this review suggests that Georgia consider administering an examination at the end of grade nine (or grade 10, if compulsory education is extended) that would, alongside teachers’ continuous assessment, help inform student choice with respect to the programme of study in upper secondary education. Internationally, there is considerable variety, related to the structure of national school systems, in how countries examine students at the end of lower secondary education. However, considering the structure of schooling in Georgia and the country’s goals to further develop VET, the review team suggests introducing an examination that would help select students into upper secondary pathways. Box 2.5 describes such an examination from Ireland, a country that also requires education through the second cycle of education, after which students can continue in general education or move to a more vocationally oriented track. Ireland’s examination also relies on a wide range of assessment practices, such as a project, which help the examination serve formative as well as summative purposes.

Georgia would be well-positioned to develop such an exam, as it could be based on the existing VET examination. Having such an examination for all students would better inform student choice and support Georgia’s national goal of strengthening the VET sector in upper secondary education. Administering an examination later in a student’s education (as opposed to during primary grades) helps to mitigate the risk of labelling young students while generating positive effects, such as incentivising students to apply themselves and helping students identify their interests. Some teachers told the OECD review team that they would welcome a national examination at this stage to alleviate the pressure of determining student pathways solely via their marks.

In 2015, Ireland introduced a new framework for the Junior Cycle of education (lower secondary level, three years in total). An assessment model called the Junior Cycle Profiles of Achievement is included in the framework. According to this reform, students will be assessed continuously throughout junior cycle and at the end by an external examination.

As part of continuous assessment, students must take two classroom-based assessments, one in their second year and one in their third year. These assessments might include oral presentations, written work, practical activities, artistic performances and scientific experiments. Related to the second classroom-based assessment is a written assessment task, which requires that students demonstrate an understanding of the knowledge and skills covered in the second classroom-based assessment. This task is completed in class but marked centrally.

At the end of their third year, students take external examinations in most subjects. All exams are created, administered and marked centrally. Most subjects have only one common level of difficulty, though English, Mathematics and Irish have two levels (ordinary and higher).

As education in Ireland is compulsory up to age 16, or three years of secondary education, students who receive their junior cycle certification must choose whether to continue with schooling or pursue other training opportunities. Their assessment results in junior cycle – continuous, classroom-based and external – act as key pieces of information that help them make this important decision.

Sources: Ireland Department of Education and Skills (2015[53]), Framework for Junior Cycle 2015, www.education.ie (accessed on 3 January 2019); Eurydice (n.d.[54]), Assessment in Lower Secondary Education – Ireland, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/assessment-lower-secondary-education_en (accessed on 3 January 2019).

copy the linklink copied!Policy issue 2.2. Building understanding that the goal of assessment is to improve student learning

Having a high-level of assessment literacy, defined as what stakeholders (teachers, students and parents) understand about education assessment, is an important aspect of contemporary education (Plake, 1993[55]; Fullan, 2000[56]). In Georgia, improving teacher assessment literacy is a critical need. This review has proposed specific reforms that MoESCS should consider introducing in order to orient teachers towards using formative assessment and enhance the educational value of summative classroom assessment and examinations. However, changing assessment practices in classrooms, schools and even the system will not achieve the desired outcomes unless a collective understanding of the achievability and value of those reforms is reached (Fullan, 2006[57]; Fullan, 1992[58]). This is particularly important in Georgia, where efforts to strengthen assessment practices have lacked sufficient explanation for the rationale of the change and many stakeholders remain unclear about why change is needed. Without understanding why the proposed changes are valuable, students, teachers and parents will simply comply with the new requirements without fully embracing the intent of the reforms.

Recommendation 2.2.1. Provide teachers with assessment resources to improve student learning

For most teachers in Georgia, re-orienting their assessment practices to promote student learning represents a radical departure from what they are used to. They will not be able to understand the value of, much less implement, these practices without consistent support and reinforcement, which research shows is one of the primary factors associated with sustaining the use of effective assessment practices in the classroom (Harrison, 2005[59]; Wilson, 2008[60]). In Georgia, what teachers learn about assessment during ITP can be improved, but an immediate challenge is to develop the assessment literacy of in-service teachers. As mentioned previously, regular, in-school support is an effective method of building confidence and capacity for new approaches, especially when teachers are also encouraged to work together and are given access to a range of high quality assessment resources.

Strengthen the emphasis on improving assessment practices during initial teacher education

Teachers who complete ITP should be expected to have a minimum level of competence in the area of student assessment. In Georgia, ITP programmes struggle to provide teacher candidates with a strong basis in student assessment. There are no standards for graduated teachers in general, and none on assessment in particular. These standards would specify the types of skills graduated teachers would be expected to acquire and demonstrate. Georgia should develop these standards and use them to help guide the design of ITP programmes and the pedagogy examination recommended in chapter 3 of this review.

The planned introduction of a new consecutive ITP programme and the review of the extant one-year programme that this review recommends provide an opportunity to improve how teachers are trained to assess their students. Georgia should integrate into these programmes practices that have been internationally recognised to be effective in developing teachers’ assessment literacy. In Finland, which is recognised for having strong ITP programmes, teacher candidates are trained to assess students using a range of approaches. These might include group tasks, individual presentations, quizzes, practical assessments and performances and, crucially, the focus is on involving students in their own assessment (Niemi, 2015[61]; Kumpulainen and Lankinen, 2012[62]). Box 2.6 further identifies research about effective initial teacher education practices related to student assessment. They include mentorship and exposure to several types of assessment during teacher practicums.

A university in Victoria, Australia has established the Assessment Mentoring Program (AMP) as part of its initial teacher education. Through AMP, fourth year physical education teacher candidates were assigned to mentor second year physical education teacher candidates. The mentors helped mentees throughout their student teaching and developed, tested, implemented and moderated an assessment tool for the mentees with the assistance of program lecturers. A study of the program focused on the mentors and found that they believed they developed valuable assessment experiences that would be transferrable to their work in schools (Jenkinson and Benson, 2016[63]).

Research into teacher candidates in Spain focused on the use of formative assessment practices in initial teacher education. Results show that, despite being encouraged to employ formative assessment when they become teachers, teachers are infrequently taught using formative assessment techniques during their ITP training. When such methods are used, they are valued by teacher candidates and some graduates have implemented the practices themselves after being exposed to them during their training. This suggests that incorporating formative assessment practices into teachers’ own education might be advisable (Hamodi, López-Pastor and López-Pastor, 2017[64]).

In the United States, researchers studied teacher candidates who enrolled in a semester-long, senior-level course specifically about assessment. The focus of the course was on learning about measurement theory and developing and interpreting student assessment information. Results showed that teacher candidates who enrolled in the course changed their perspective from assessment being about testing to assessment being about a formative process that can be achieved through different types of tools. Course participants also expressed greater confidence in employing formative approaches in their teaching. This research indicates that explicitly emphasising student assessment during initial teacher education might lead to teachers’ employing more sophisticated assessment techniques in their own practice (DeLuca, Chavez and Cao, 2013[65]).

Sources: Jenkinson and Benson (2016[63]), “Designing Higher Education Curriculum to Increase Graduate Outcomes and Work Readiness: The Assessment and Mentoring Program (AMP)”, Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, Vol. 24/5, pp. 456-470, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2016.1270900; Hamodi, López-Pastor and López-Pastor (2017[64]), “If I experience formative assessment while studying at university, will I put it into practice later as a teacher? Formative and shared assessment in Initial Teacher Education (ITE)”, European Journal of Teacher Education, Vol. 40/2, pp. 171-190, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1281909; DeLuca, Chavez and Cao (2013[65]), “Establishing a foundation for valid teacher judgement on student learning: the role of pre-service assessment education”, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, Vol. 20/1, pp. 107-126, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2012.668870.

Orient school-level professional development towards improving student assessment

Providing effective school-level supports can help teachers adopt new educational practices. With respect to student assessment, teachers can improve their own understanding and methods by observing each other, discussing how to design assessment and reviewing student work and reaching consensus around how to mark it (Harrison, 2005[59]; Tang et al., 2010[66]).

An important ingredient in supporting teachers in schools is allocating time for teachers to develop themselves. In Georgia, teachers currently have a surplus of non-instructional time in school and chapter 3 of this review recommends that this be used more effectively. This time could be used to help teachers collectively understand the curriculum’s assessment requirements and to organise the aforementioned moderation activities.

In addition to allocating time for the purpose, having strong school leadership that recognises the value of supporting teachers is highly important for helping teachers develop. Georgian principals are not accustomed to fulfilling this type of instructional leadership role and will need some guidance in how to best support their teachers. For this reason, the review team recommends that the several MCC sponsored programmes that are dedicated to improving assessment be continued and expanded. These programmes will provide principals with an established structure to follow in support of their teachers until they feel comfortable enough to determine independently how to best help their teachers develop.

Facilitate the development of teacher networks about assessment to support teachers, especially those in smaller and more rural schools

Along with support organised by schools, research shows that peer-to-peer collaboration can help teachers feel confident in appropriating new pedagogical methods (Wilson, 2008[60]). In Georgia, peer-to-peer activities do not occur frequently. In the survey administered as part of this review, 35% of teachers indicated that never, or only once a year or less, do they engage in discussions about the learning development of specific students. When asked if they work with other teachers to ensure common standards for assessing students, 21% said that they never do, or do so once a year or less.

Teacher collaboration in Georgia should be expanded, especially between experienced and less experienced teachers. Although schools have a responsibility to facilitate this collaboration, teachers themselves should also be encouraged to work with each other. While mentor and lead teachers would be suitable candidates to lead collaborative efforts and share their expertise, there are few teachers at these levels and most are concentrated in certain areas of the country (see chapter 3). Georgia also has a large number of small schools with few teachers. These circumstances limit the extent to which constructive collaboration can occur within Georgian schools.

One way of addressing these challenges is to use technology to expand the pool of potential teachers with whom teachers can collaborate. In Georgia, all school communications is already facilitated through EMIS E-Flow, which allows users to see the school and other information about message senders and recipients. While it is designed for sending and receiving messages, E-Flow can be given expanded functions to ease formal collaboration between teachers around topics such as assessment. For example, groups can be formed comprised of a lead teacher and several practitioner teachers from different schools with the expressed purpose of discussing assessment. E-Flow’s link to EMIS data can be harnessed to identify teachers in similar contexts, thus increasing the relevance of their collaboration.

Create an online repository of assessment resources

The OECD review team was told that Georgian teachers are using a limited repertoire of assessment types, such as multiple-choice quizzes, that mostly assess student’ ability to memorise and recall facts. Teachers have expressed a desire to use different types of assessments, such as more complex quizzes and ideas for class projects, but do not know where to access these resources.

An online repository represents an effective way of providing resources to schools, particularly rural ones who might not be able to access universities or even the nearest ERC. Many OECD countries have developed such repositories. For example, Ireland makes available online thousands of assessment resources that are explicitly linked to the national curriculum (Department of Education and Skills, 2019[67]). The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership has created a website to house a comprehensive collection of teaching resources (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, n.d.[68]). These include lesson plans, guidance on providing feedback and video examples of how to use different methods to assess students.

Georgia has already begun to create an online repository of teaching materials (www.el.ge). Presently, however, this website only contains teaching stimuli, such as books, articles, and videos. It does not include pedagogical materials, such as tests, worksheets, lesson plans or student portfolios examples. It also does not include key strategic documents, such as the curriculum. Adding all such materials to this website would provide teachers with more resources and enable them to relate those resources to learning outcomes, which would increase the likelihood that the resources are used. Enhancing the online portal would also help improve equity as teachers in rural areas would be able to access the same resources as teachers in urban areas.

Recommendation 2.2.2. Communicate that the goal of student assessment is to improve learning