4. Governance gaps

This chapter describes the main challenges that surveyed cities and regions are facing or are likely to face when transitioning from a linear to a circular economy. There are five main categories of gaps: financial, regulatory, policy, awareness and capacity. The chapter builds on the results of the OECD Survey on the Circular Economy in Cities and Regions, as well as on the case studies of the OECD Programme on the Circular Economy in cities and Regions carried out in Groningen, (Netherlands), Umeå (Sweden) and Valladolid (Spain) and on-going in Glasgow (United Kingdom), Granada (Spain) and Ireland.

The transition to a circular economy does not come without obstacles. Matching biological and technical cycles of cities and regions and the various ways in which resources can be repurposed and reused, from water to energy and mobility, is a complex task for integrated master plans, reflecting interests and motivations within a very complex urban society. From a business perspective, there is no efficient secondary market for most of the collected household waste. Still, virgin materials are less expensive than secondary products. The uncertainties in terms of economic benefits prevent the circular economy happening on the ground. Circular economy initiatives are devoting more attention to the downstream process rather than to the upstream one, while well-designed products can reduce waste generation in the first place. Moreover, activities foreseen by a circular economy face some reluctance and scepticism, as in the case of reuse. Collaboration along a value chain, upstream and downstream, is challenging as, in reality, these actors either compete or do not interact on the market. This collaboration can be best established at a regional and urban scale, as local and regional authorities can play a very important role in launching new market interactions (OECD, 2020[1]).

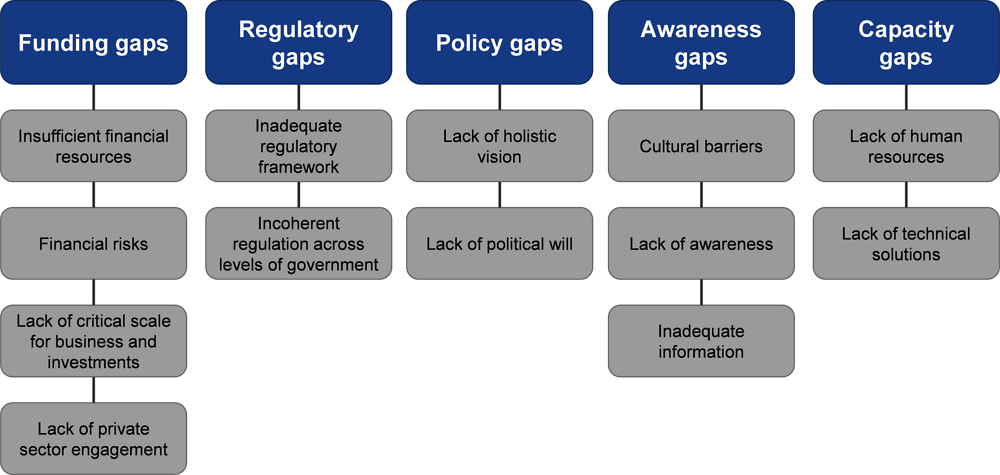

Major obstacles for surveyed cities and regions transitioning towards circular economies are not technical but of an economic and governance nature. Insufficient financial resources, inadequate regulatory frameworks, financial risks, cultural barriers and the lack of a holistic vision are amongst the major obstacles identified by more than one-third of the interviewed stakeholders in the OECD survey (2020[2]) (Figure 4.1). Technical solutions exist and are well known. However, to put them in place, the legal framework should be updated, financial resources should be adequate and data and information shared, amongst others.

Cities and regions face five major categories of gaps:

Funding gaps: The transition towards a circular economy implies investments and adequate incentives to make the economic and financial case for the circular economy. Cities and regions responding to the OECD survey (OECD, 2020[2]) face constraints in terms of insufficient financial resources (73%), financial risks (69%), lack of critical scale for business and investments (59%), and lack of private sector engagement (43%).

Regulatory gaps: Inadequate regulatory framework and incoherent regulation across levels of government represent a challenge for respectively 73% and 55% of the surveyed cities and regions.

Policy gaps: A lack of holistic vision is an obstacle for 67% of surveyed cities and regions. This can be due to poor leadership and co-ordination. Other policy gaps concern the lack of political will (39%).

Awareness gaps: Cultural barriers represent a challenge for 67% of surveyed cities and regions along with lack of awareness (63%) and inadequate information (55%) for policymakers to take decisions, businesses to innovate and residents to embrace sustainable consumption patterns.

Capacity gaps: Lack of human resources and of technical solutions represent a challenge for 61% and 39% of surveyed cities and regions.

Shifting from a linear to a circular economy is going to require a significant amount of investment, but cities and regions report inadequacy of financial resources. Investment gaps are usually bridged through public funds, as well as taxes and subsidies. In Joensuu, Finland, for example, the lack of financial resources devoted primarily to circular economy efforts represent a major obstacle in helping entities transition away from a linear economy. In Phoenix, United States, limited financial resources hinder the design and implementation of additional circular economy-related projects and programmes. In Groningen, Netherlands, due to the lack of financial resources for innovators, only small-scale low-risk projects can actually materialise with limited impacts in terms of job creation and positive environmental effects.

Funding allocation may face difficulty in relation to the fuzziness of the concept of the circular economy. Beyond the amount of funds needed, which is limited in cities in most cases, there is a lack of proper understanding of how to most efficiently use the funds. For example, start-ups boosting innovation that could spur the circular economy cannot apply to available funds as their projects are not explicitly related to “circular economy projects”, even if they could contribute to creating innovation technology or circular business models (Jonker and Montenegro Navarro, 2018[3]).

Cities and regions use public funds to start up circular projects, however, scaling them up is complex due to limited access for companies to alternative financial sources. For example, in Valladolid, Spain, the local government financed a total of 61 projects (22 and 39 respectively in 2017 and 2018), allocating a budget of EUR 960 000 (EUR 400 000 and EUR 560 000 in 2017 and 2018 respectively). The municipality financed between 40% and 85% of the project’s total cost. The beneficiaries of the grants were private companies, associations of private companies, non-profit entities or research centres based in the municipality of Valladolid. An additional EUR 600 000 are assigned for 2019-21 (this amount represents 0.17% of the annual budget of the city) (OECD, 2020[4]). Most of the projects have an experimental nature. Their profitability is uncertain. Entrepreneurs face high investment risks and access to loans is not always guaranteed. In Valladolid, innovative circular economy projects rely very much on business angels such as ethical banks (Fiare,1 Triodos)2, financial agencies (Finova)3 or private equity firms, willing to promote and finance circular-economy-related projects. However, after the initial experimental phase, the challenge for innovators is how to make their projects economically sustainable in the medium and long terms (OECD, 2020[4]). In London, United Kingdom (UK), the LWARB offers support and access to finance. The main concern is how to scale this help and make a significant impact on business creation. Companies are often reluctant in changing procedures and forms of financing related to loss of efficiency compared to the competition that continues to work in linear logic. There are difficulties in scaling up pilot projects and experimentation.

Vertical and horizontal co-ordination for funding allocation is complex. In Groningen, Netherlands, provincial and regional funds directly related to the circular economy have not been allocated yet. Possibly, the city could benefit in the future from funds from the national government, which, in 2019, allocated an additional EUR 22.5 million in total for sustainable and circular initiatives consequent to the definition of the circular economy strategy. However, it is unclear what the procedures are to access these funds. The funding is linked to the envelope of EUR 300 million that the government makes available annually for the climate. In fact, the government strongly believes that the circular economy is needed to achieve climate goals and that waste is a resource (OECD, 2020[5]). In Antwerp, Belgium, financial resources are spread across different departments. However, there is a lack of clear view on the budget allocation of different projects that might fall under the circular economy.

Shifting from a linear to a circular economy presents financial risks for economic actors. This is somehow related to the critical scale of activities taking place in cities of different sizes, due to market size, population, material flows, etc. Often, the scale at which the circular economy initiative is established does not reflect the complexity of interactions between different spheres, policies and actors. Also, de-risking circular investment opportunities requires adequate regulatory frameworks but also clarity in the project presentation and execution. It is important to strengthen the involvement of established big business players as accelerating agents for the transition. In Glasgow, UK, the city is trying to stimulate more established businesses to integrate the circular economy into their business models. Some large corporations’ leaders could further embrace end-of-life concepts, introducing ideas such as repurposing, reusing or remanufacturing. In Flanders, Belgium, for example, the need for funding projects covering the entire product/value chains has been highlighted.

Surveyed cities and regions claim the need to develop and adapt the regulatory framework to enable the transition towards the circular economy. A range of stakeholders, from waste operators to constructors, finds regulations related to material reuse inadequate for the transition from a linear to a circular economy. There is uncertainty around the categorisation of waste streams and how materials can be reinserted in production processes when they are still reusable but by law qualified as waste. One of the biggest obstacles for implementing circular economy is the definition of “waste” in national legislations. Other regulatory barriers are related to second-hand materials, land allocation, water reuse, demolition material reuse, especially to allow pilots and experimentations. Examples of barriers concern, for instance, the lack of clear rules for the use of sludge, reclaimed water and recycled waste (according to the type) in accordance with health and ecological standards. In Europe, the current eco-design directive strongly focuses on energy-related areas and to a lesser extent on materials and typology of products in a broader perspective. During the implementation of the BRICK-BEACH Project on beach regeneration in Vélez-Málaga, Spain, one of the biggest obstacles that emerged was the inadequacy of local regulation to manage waste and reuse/recycle materials.

Some national governments are taking actions towards adapting existing regulations to emerging needs related to the circular economy. In the Netherlands, the legal and regulatory framework at the national level is expected to be adapted in order to make the country an economy without waste in 2050, as defined by the National Circular Economy Strategy. For example, since 2016, the national government adopted a flexible approach for amendments of the National Waste Management Plan to anticipate the changes required by the transition. Another example is the national Smart Regulation programme (Ruimte in Regels) that runs up to 2020, according to which the government co-operates with entrepreneurs to promote sustainable innovations within the current legislation (Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment/Ministry of Economic Affairs, 2016[6]). For example, in 2017, companies in the wind energy sector contacted the Smart Regulation programme helpdesk specialised in the chemistry sector to raise the issue of the restrictive regulations regarding the inability to reuse plastic turbine blades for windmills after their replacement. This plastic is now used as an input in the car and ship industry (Ministry of Economic Affairs, 2017[7]; OECD, 2020[5]).

Survey results point to the need to strengthen national-level legislation in enhancing the circular economy transition in public procurement. For example, in Ireland, setting mandatory requirements for green public procurement (GPP) could represent an opportunity for the public sector to lead by example. GPP represents 10% of Ireland’s gross domestic product (GDP) (OECD, 2020[8]). In other cases, while environmental criteria have been added to the selection process, in practice, the price is still the prevailing selection method. In Valladolid, Spain, the city approved “Municipal Ordinance 1/2018 to Promote Social Efficient Procurement: Strategic, Exhaustive and Sustainable". The ordinance incorporated environmental dimensions in municipal procurement that entail that the subject and pricing of municipal contracts should consider life cycle criteria or the most innovative, efficient and sustainable solutions. Nonetheless, the award criteria in public procurement procedures in Valladolid are the following: 60% driven by price and 40% driven by an “improvement criterion” (of which 20% is related to social aspects). Moreover, when introducing environmental criteria, there is the risk for tenders to go empty or that participating companies would complain about the possible threat of anti-rivalry clauses, claiming that only big companies can meet some of the specific requirements. There is also a difficulty in verifying the information provided by the participants in tenders when it comes to environmental dimensions (OECD, 2020[4]). In Ljubljana, Slovenia, legal constraints public procurement hinder innovative projects to occur.

The variety of actors, sectors and goals makes the circular economy systemic by nature. It implies a wide policy focus through integration across often siloed policies. When interactions and complementarities are overlooked, the lack of a systemic approach might lead to the implementation of fragmented projects in the short to medium run, rather than sustainable policies in the long run. In many cases, the transition is mainly focused on enabling niche-level techno-economic experimentations, while more systemic socio-economic agendas have not yet been connected to circular economy debates.

A holistic view at the city strategy level may help break these silos to some extent. The city of Groningen, Netherlands, set up environmentally sustainable initiatives that can help build a narrative on the circular economy, from waste to mobility and energy. However, these initiatives are still fragmented and would benefit from greater inter-relations with the aim of achieving common socio-economic and environmental objectives (OECD, 2020[5]). As such, there is room to maximise synergies and opportunities related to the use of natural, financial and human resources. In Valladolid, Spain, three main challenges were identified that reflect those of many other European cities (OECD, 2020[4]):

Coherence across existing policies and plans: Valladolid is implementing different policies and programmes (e.g. Smart City programme, urban sustainable mobility, green infrastructure, district heating, circular economy) that would benefit from a more holistic approach and greater co-ordination to close loops. Currently, it is not clear how the mentioned policies coherently connect to one another. For example, the New General Urban Plan (2019) that promotes a compact city model could be linked to various actions in complementary sectors that foster circularity in the city, from mobility to infrastructure.

Coherence across current and future circular projects: At the moment, there is the risk of delivering isolated circular economy actions while missing the long-term vision. It is not clear how the selected projects will be contributing to the overall vision of the city of Valladolid.

Coherence across EU funded projects and circular economy planned initiatives: The city heavily relies on European funds for policy innovation. However, initiatives can result in fragmented actions, which could be short-medium-term oriented. The municipality conceives the European projects as a way of experimenting with new policies without using local taxpayers’ money and as an opportunity to foster public-private partnerships under the “consortium agreement” model. For example, the REMOURBAN project that focused on improving buildings’ energy-efficiency was applied to the FASA district but was not integrated into a city level strategy. The same happened with the biomass district heating system that the municipality installed in the FASA neighbourhood that was not part of a broader plan. The municipality would benefit from clarifying how to maximise synergies between these initiatives and those planned within the circular economy approach.

In some surveyed cities, the mandate in terms of who is responsible for the design and implementation of a circular economy strategy amongst the city administration is not clear. A lack of leadership could lead to fragmented initiatives on the circular economy and weak accountability. Therefore, clarifying “who will do what” would serve as a reference for various stakeholders in identifying the focal point (office/departments) to go to for projects and investments. In many cases, roles and responsibilities in setting and implementing long-term visions for the circular economy are allocated to waste management or environmental departments, once again missing the multi-dimensional perspective of the circular economy. Several departments are likely to be involved in circular-economy-related activities, therefore co-ordination should be strengthened. The challenge is how to create more uniform policies in order to promote circular solutions throughout the city organisation.

Cultural barriers are an important obstacle, prevalent within the business community, among governments and residents, that prevent the necessary behavioural shifts required to transition to a circular economy. Some circular-economy-related activities, for example reuse, are barely conceived as valuable options to reduce consumption and therefore waste generation. There is a problem of acceptance that is due to lack of awareness but also trust in terms of quality of the reused products and goods. Many cities and regions have for this reason put in place a system of quality certificates. For example, the programme Revolve Re-use by Zero Waste Scotland set up reuse quality standards for reuse shops, which are endowed with a dedicated logo that is recognisable by consumers (Zero Waste Scotland, 2020[9]).

Embracing circular economy principles still represents an exception. Changing “business as usual” is not an easy task. To accelerate the circular economy transition, there is the need to build knowledge and understanding of the concept, costs and benefits of the circular economy and what it would entail for various activities and sectors. Poor awareness of circular economy practices amongst key players can hinder opportunities for scaling them up. One of the main issues is to involve a great number of people and not only the “happy few”. Attitudes and resistance to change is also a major challenge (OECD, 2020[5]). For example, although the city’s strategy and the Carbon-neutral Helsinki 2035 Action Plan includes targets and actions regarding circularity, not all actors are prepared to start implementing them (City of Helsinki, 2018[10]). The city of Milan, Italy, believes that such changes have to be human-centred.

The concept of the circular economy is not yet clear to many. In Umeå, Sweden, many stakeholders use the circular economy as a synonym for recycling. There is a form of scepticism across stakeholders that have been implementing environmental and sustainable practices and do not see the value-added in the circular economy approach. In Valladolid, Spain, more than 70% of companies from a total of 70 companies surveyed in 2018 declared that they do not know the meaning of the circular economy. They associate the term with minimising waste production, recycling and reusing and state that they are already implementing these processes in a regular way (EDUCA, 2018[11]). On the other hand, 85% of consumers in Valladolid do not know what the circular economy means and only 52% of consumers expressed they “always” or “regularly” separate waste (EDUCA, 2018[11]). While separate waste collection is compulsory, there is no enforcement on waste collection. The lack of waste separation generates extra costs to the municipality at the collection and treatment steps. In Ireland, only 50% of business leaders were acquainted with the term circular economy according to the survey launched in 2019 by the Environment Protection Agency and the Irish Business Employers Confederation (IBEC, 2019[12]).

In many cities, there is room for more systematic data collection that could allow taking circular decisions, measuring progress and improving implementation. For example, data on material consumption are available both at the global and national levels and less at local level. It is often difficult to account for consumption-based emissions within the city’s administrative boundaries. Circular economy indicators have a tendency to focus on materials, solid waste, energy flows and environment, but there is less emphasis on the economic and social dimensions. Evaluation and monitoring frameworks for the circular economy are common challenges for cities. Only a few existing strategies are accompanied by a monitoring framework (see Chapter 5).

Capacities in many municipalities should match the needs of the circular economy transition, in terms of skills and human resources. Antwerp, Belgium, highlighted in the survey the lack of human resources dedicated specifically to the circular economy, which is a challenge to advance with the transition. The Metropolitan Area of Barcelona, Spain, reports the need for technicians with specific knowledge of the circular economy. In Umeå, Sweden, where the circular economy is a relatively new concept for the city, major activities relied so far on external consultants for carrying out investigations and ad hoc studies. There are several initiatives in place to build capacity and knowledge on the circular economy, organised by not-for-profit and public organisations (Chapter 2). However, while informative, workshops and events may often remain generic, while some actors, such as in the business sector, would benefit from more specific and practical input, including through peer-to-peer learning.

References

[10] City of Helsinki (2018), The Carbon-neutral Helsinki 2035 Action Plan.

[13] EC (2020), Life-cycle Costing, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/lcc.htm (accessed on 4 August 2020).

[11] EDUCA (2018), Asociación de Empresas y Profesionales EDUCA, http://www.educavalladolid.es (accessed on 4 August 2020).

[12] IBEC (2019), “New Ibec survey shows just half of businesses understand the Circular Economy”, http://www.ibec.ie/connect-and-learn/media/2019/08/14/new-ibec-survey-shows-just-half-of-businesses-understand-the-circular-economy (accessed on 4 August 2020).

[3] Jonker, J. and N. Montenegro Navarro (2018), “Circular city governance - An explorative research study into current barriers and governance practices in circular city transitions in Europe”.

[7] Ministry of Economic Affairs (2017), Better Regulation: Towards a Responsible Reduction in the Regulatory Burden 2012-2017, Government of the Netherlands, http://www.government.nl/documents/reports/2017/08/22/better-regulation-towards-a-responsible-reduction-in-the-regulatory-burden-2012-2017 (accessed on 4 August 2020).

[6] Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment/Ministry of Economic Affairs (2016), Accelerating the Transition to a Circular Economy, Government of the Netherlands, http://www.government.nl/topics/circular-economy/accelerating-the-transition-to-a-circular-economy (accessed on 4 August 2020).

[1] OECD (2020), “OECD - Nordic Innovation webinars on the circular economy in cities and regions”, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/highlights-2nd-OECD-roundtable-circular-economy.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2020).

[8] OECD (2020), “OECD interviews with the local team of Ireland”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[2] OECD (2020), OECD Survey on Circular Economy in Cities and Regions, OECD, Paris.

[14] OECD (2020), OECD Survey on Circular Economy in Cities and Regions, OECD, Paris.

[5] OECD (2020), The Circular Economy in Groningen, the Netherlands, OECD Urban Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/e53348d4-en.

[4] OECD (2020), The Circular Economy in Valladolid, Spain, OECD Urban Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/95b1d56e-en.

[9] Zero Waste Scotland (2020), Establishing Re-use and Repair in Scotland, https://www.zerowastescotland.org.uk/circular-economy/establishing-reuse-repair (accessed on 5 August 2020).

Notes

← 1. For more information: www.fiarebancaetica.coop/ (accessed on August 2020).

← 2. For more information: www.triodos.es/es (accessed on August 2020).

← 3. For more information: http://web.finnovaregio.org/ (accessed on August 2020).