2. Why is career guidance for adults important in Latin America?

A year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Latin American countries have experienced economic disruption and struggling labour markets. Even prior to the crisis, skills demand had been changing due to digitalisation, globalisation, population ageing and the transition to low-carbon economies. This chapter provides a brief overview of the labour market context in Latin America and suggests an increasingly important role for career guidance for adults.

The COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated existing challenges in Latin American labour markets, including high unemployment. The key findings of this chapter are outlined as follows:

Latin American labour markets face a number of challenges. Unemployment is high relative to the OECD average, and there is a large share of workers in informal employment. High inequality translates to unequal educational outcomes, and educational attainment falls below the OECD average in the four Latin American countries studied. Despite poor performance on literacy and numeracy skills relative to the OECD average, adults in Latin American countries are also less likely to participate in training, which makes adults in these countries more vulnerable to the impacts of automation and associated changing skills demand.

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to exacerbate these challenges. Unemployment rose in 2020, and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to accelerate technological adoption going forward.

Career guidance for adults is relatively rare in the Latin American context, though it could play an important role in supporting adults in finding new employment and adapting to changing skills demand. Career guidance is a set of services intended to assist individuals of all age groups to make well-informed educational, training, and occupational choices.

The world of work is changing amid globalisation, technological change, population ageing and in response to environmental pressures. Previous OECD analyses have demonstrated that Latin American countries are also affected by these trends, although with some difference from other regions (OECD, 2020[1]). With a younger population and a slower speed of adoption of advanced technologies, Latin American countries have so far been somewhat sheltered from the impacts of population ageing and technological change. That said, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to accelerate technological adoption going forward. Further, the sectoral composition of many Latin American countries – where extractive industries still play an important role – mean that policy efforts to reduce the impact of climate change may affect these countries more heavily.

In light of these changes, career guidance for adults represents a fundamental lever to help adults successfully navigate a constantly evolving labour market. In a recent cross-country review, the OECD defined career guidance as “a set of services that assist individuals in making well-informed educational, training and occupational choices” (OECD, 2021[2]). There is evidence from the literature of the positive impact of career guidance on learning outcomes, training participation, and, to a lesser extent, employment outcomes (OECD, 2004[3]; OECD, 2021[4]).

This report provides a comparative analysis of career guidance for adults in four Latin American countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico. It is based on a combination of desk research, video calls with stakeholders in each country, and policy questionnaire responses from Ministries of Labour and Education. The analysis also draws from the 2020 Survey of Career Guidance for Adults (SCGA). The SCGA is an online survey of adults’ experience with career guidance. In a first phase of fieldwork, data was collected in Chile, Germany, France, Italy, New Zealand, and the United States, and in a second phase in Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. The report sometimes refers to ‘Latin America’ when discussing data collected for the four Latin American countries mentioned above to avoid repetition.

This report includes recommendations and five chapters. Chapter 2 describes the general skills and labour market context in Latin America. It then defines the concept of career guidance for adults, and how this concept is understood in Latin America. Chapter 3 presents findings on the coverage and inclusiveness of career guidance services based on the SCGA. Chapter 4 maps the career guidance provider landscape and presents data on the different channels of service delivery. Chapter 5 reviews existing evidence on the quality and impact of career guidance services, and discusses policy options to improve them in the future. Chapter 6 discusses the stakeholders and co-ordination mechanisms in place to govern career guidance systems as well as how costs for career guidance are shared among governments, employers and adults.

Latin American countries have been hit hard by the COVID-19 crisis while facing continued structural challenges. Low productivity, high inequality and informality, combined with underfunded public services and institutions, complicate the responses to the pandemic and compromise the well-being of the population (OECD et al., 2020[5]). The demand and supply for labour and skills in Latin American labour markets have inevitably been affected by the crisis, as well as the ongoing global trends in digitalisation, globalisation, demographic change and the shift to a low-carbon economy.

Substantial underutilisation and underdevelopment of skills

Unemployment, underemployment and poor quality jobs all undermine the opportunities for adults to use and improve their skills and harm individual well-being and the productive potential of the economy. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have increased unemployment in Latin American countries, where unemployment was already high prior to the pandemic. The average unemployment rate of the four Latin American countries rose from about 8% in 2019, to just over 10% in 2020 (Figure 2.1). This is about 3 percentage points above the OECD average. Working hours in the region also fell by 16% during 2020 (ILO, 2021[6]).

The labour under-utilisation rate is a broader measure than the unemployment rate. It measures the share of the labour force who are unemployed, marginally attached (i.e. persons not in the labour force but who wish to and are available to work), or underemployed (full-time workers working less than usual due to economic reasons or part-time workers who wanted to work full-time). Labour underutilisation is comparably high in Latin America and employment growth is expected to continue to decline (ILO, 2020[7]). Gender gaps also remain large in Latin American labour markets.

The share of young people (18-24 year-olds) neither employed nor in education or training (“NEET”), is an important indicator of the extent to which young people are not gaining additional skills either through on-the-job learning at work or through formal education and training. In 2019, it was above the OECD average (14%) in all four countries, and highest in Brazil (31%), followed by Argentina (24%), Mexico (22%) and Chile (22%) (OECD, 2020[8]).

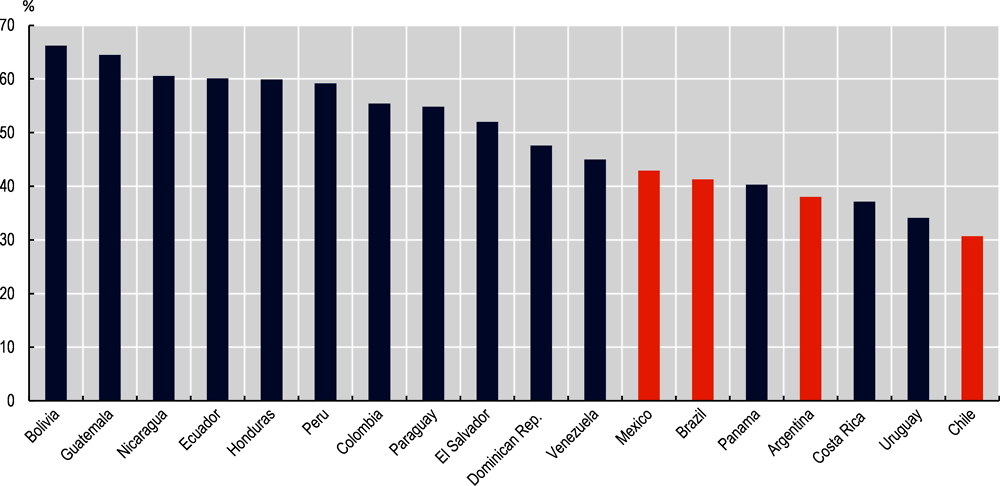

In addition, Latin American labour markets are characterised by high informality, which may limit learning opportunities. Chile, Argentina, Brazil and Mexico have among the lowest shares of informal employment in Latin America, but the shares remain high (Figure 2.2). In Mexico, 46% of the adult population were employed in the informal sector in 2018 compared with 42% in Brazil and 40% in Argentina (CEDLAS and The World Bank, 2020[9]). The lowest share of informality is in Chile (32%). In comparison, undeclared work in the private sector in the EU is around 16%1 (European Commission, 2017[10]). In all countries, informality is significantly higher in rural areas than in urban areas and higher for women than for men. High-educated workers are the least likely to work in informal employment.

As a result of the high rate of informal employment, job quality is relatively low in Latin American countries. Workers disproportionately work in low-productivity jobs that also pay comparatively low wages (ILO, 2020[7]). Earnings inequality is higher and workers in Latin America tend to be more vulnerable to labour market risks compared to OECD countries. In most emerging economies, this primarily reflects the risk of falling into very low pay. The quality of the working environment is also generally lower in Latin America, and one indication of this is the higher incidence of working very long hours (OECD, 2020[1]).

Education and skills supply in Latin America

The Latin American region is one of the most unequal regions in the world (OECD, 2020[11]), which is reflected in unequal education outcomes, and means that a substantial portion of low-income adults are unable to afford training and career guidance. Using the Gini index, a statistical measure of economic inequality in a population on the scale of 0 (equal) to 1 (unequal), the region has an average Gini coefficient of 0.47, compared to an average of 0.31 in non-Latin American OECD countries. In 2018, Argentina recorded the lowest Gini coefficient (below 0.40), while Brazil recorded levels higher than 0.52. In both countries, inequality was higher in 2018 than in 2014. Chile’s Gini coefficient remained stable at 0.45 in 2014 and 2018 and Mexico’s latest data (2014) are similar, at 0.48.

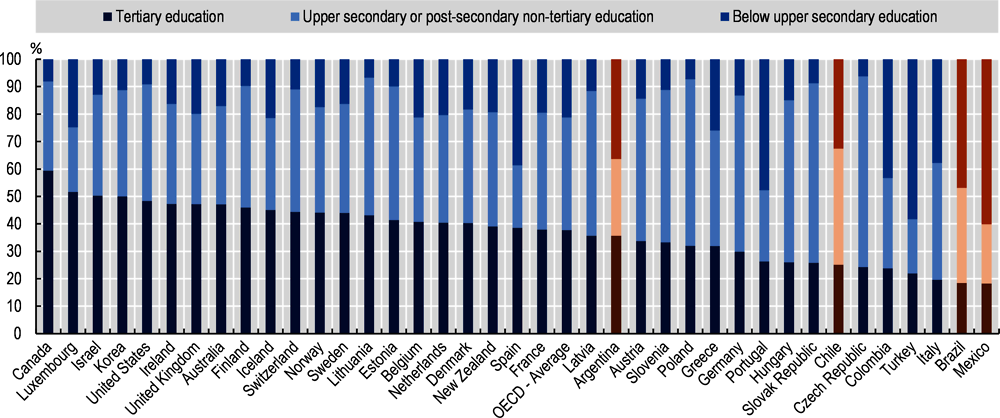

While countries in Latin America have seen important improvements over the past years, educational attainment remains relatively low. On average, 56% of individuals aged 25-64 across Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico have completed at least upper secondary education, compared with 79% on average across OECD countries. Chile has the highest share of adults who completed at least upper secondary education among the Latin American countries in this review (67%) (Figure 2.3). Argentina has the highest share with tertiary education (36%), a share close to the OECD average of 38%. A comparison to the educational attainment of the youngest adults (25-34) in this population shows a rising trend towards higher education: on average 69% of adults in this younger group have completed at least upper secondary education.

More direct measures of skills also suggest that adult skills are relatively low in Latin American countries. In Chile and Mexico, the Latin American countries covered by the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC),2 just over half of adults have low levels of literacy skills (53% and 51%, respectively) and an even higher share have low levels of numeracy skills (60% and 62%, respectively). For comparison, 20% of adults in the OECD on average have low literacy skills and less than 24% have low numeracy skills. This points to the need to boost lifelong learning, such as upskilling and reskilling opportunities for adults.

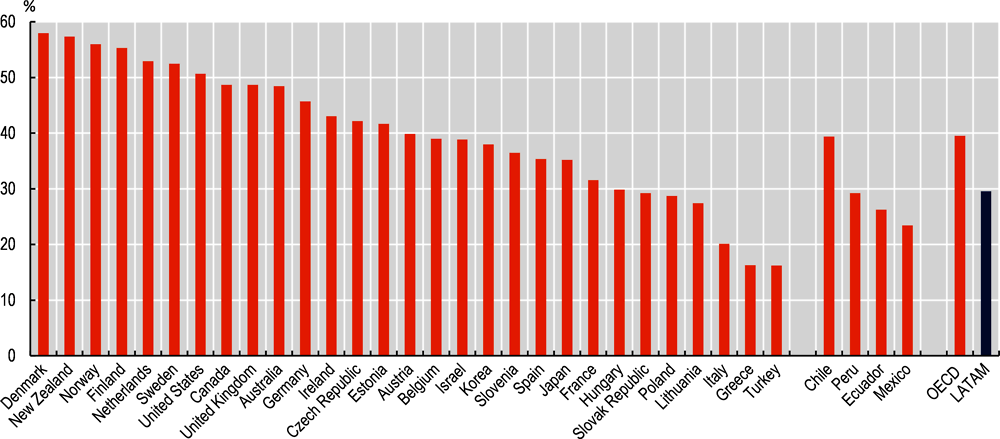

Despite the poor performance in terms of skill levels, participation in training is generally lower in Latin American countries than the OECD average. According to the PIAAC data, one out of three adults (30%) participate in formal or non-formal job-related training in the Latin American countries covered by the PIAAC survey, 10 percentage points below the OECD average of 40% (Figure 2.4). Approximately 57% of adults did not participate, and did not want to participate, in adult learning activities, compared to 49% in the OECD. However, levels of participation in adult learning in the region vary considerably, with Chile showing participation levels on par with the OECD average. Training intensity is also generally lower in Latin American countries, with a significantly smaller number of hours spent on non-formal job-related training per year than on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2020[1]).

Within Latin American countries, some groups participate in training less than others. Women participate significantly less in adult learning than men with a gap of 14 percentage points (pp) in Chile and 11 pp in Mexico. The gap in participation between low-wage and medium/high wage workers is even larger at 25 pp in Chile and 24 pp in Mexico. A sizeable gap is also found between workers with and without an employment contract, which strongly suggests that employment status and job quality are related to the take-up of training. Finally, a crucial factor influencing participation in training in Latin America is firm size: individuals working in micro and small firms (less than 250 employees) participate far less in training than those in larger firms with a gap of 27 pp in Chile and 32 pp in Mexico (OECD, 2020[1]).

Skills imbalances in Latin America

A range of indicators confirm larger gaps between labour market needs and workers’ skills in Latin American countries, compared with the OECD average. Over-qualification, i.e. the share of workers whose education level is higher than that required by their job, is almost twice as high as the OECD average (17%), ranging from around 30% in Chile, Argentina and Brazil to 38% in Mexico. Under-qualification is also substantial in Argentina (21%) and Chile (17%), similar to in the OECD average (19%). In Brazil and Mexico this seems to be less of a concern, with only 9% and 13% of workers underqualified, respectively (OECD, 2017[12]).

In line with these imbalances, shortages of highly skilled professionals are relatively low in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico, as measured by employer surveys. Less than two out of ten jobs in shortage are high-skilled and the majority of jobs in demand are found, instead, in medium and to a lesser extent in low-skilled occupations. The highest demand for low-skilled employment among the four countries is found in Mexico (34%) and the highest demand for high-skilled labour is in Argentina (almost a third) (OECD, 2020[1]). Also, the share of firms that believe an inadequately educated workforce (either too high, too low or lacking the right set of skills) is a major constraint on their operations is high in the four countries, at more than half in Brazil (69% in 2012), 39% in Argentina (2017), 41% in Chile (2012) and 31% in Mexico (2012) (The World Bank, 2021[13]).

A major trend that is expected to further disrupt labour markets and amplify skills imbalances is automation. The adoption of digital and automation technologies is likely to accelerate in the future and will alter the world of work, as well as the skills needed for economies to thrive. Already the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be speeding up the use of digital technologies (McKinsey&Company, 2020[14]; The World Bank, 2017[15]; Reuters, 2020[16]). OECD estimates, using data from Chile, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru, suggest that an average of 24% of jobs in these countries face a high risk of automation, which is almost 10 percentage points higher than the OECD average of 15% (Nedelkoska and Quintini, 2018[17]). Across these Latin American countries, another 35% of jobs are estimated to experience significant changes in the tasks that workers carry out daily, a figure that is approximately 5 percentage points higher than the OECD average. Other studies find similar results (The World Bank, 2016[18]; Weller, Gontero and Campbell, 2019[19]; McKinsey Global Institute, 2017[20]).

Career guidance is a set of services intended to assist individuals of all age groups to make well-informed educational, training, and occupational choices (Box 2.1). In many countries, career guidance policy focuses on assisting young people to make their first entry into the labour market. But given the changing world of work, adults can benefit from career guidance too.

Quality career guidance entails an involved interaction that goes beyond quickly matching a person with a job or a training programme. Ideally, career guidance helps individuals to reflect on their strengths and interests, and empowers them to make good decisions about their lifelong career development and learning. It helps to bridge transitions between learning and work, by assisting individuals to identify promising career paths and to plot the necessary next steps in terms of training and development to achieve those career goals. In an ideal system, services offer individuals more than one-off encounters; instead, individuals meet more than once with a career guidance advisor who assists them before, during and after a career move or training decision.

Career guidance for adults, as conceived above, is relatively rare in the Latin American context. Dedicated career guidance activities directed at adults remain marginal and tend not to be set out as an explicit policy priority. Career guidance for adults is usually one component of a broader set of services, such as active labour market programmes, training programmes or labour intermediation services more generally.

While career guidance for adults has not received significant policy attention in Latin American countries, career guidance for youth has received more. Youth training programmes are widespread in the region, and mostly target disadvantaged young people. Often, these programs include a dedicated career guidance component.

The way that career guidance is conceived in Latin America has been influenced by factors such as the health of the labour market, pre-existing institutional structures, and their funding capacity. While labour intermediation services and active labour market policies have been strengthened considerably in the last decades, the Latin American region still lags behind other OECD countries in terms of public resources as well as institutional capacity for career guidance services. In addition, many Latin America countries do not have unemployment insurance and only very limited forms of income support for the unemployed. As a result of these resource constraints, the providers of labour intermediation services, and often individuals themselves, place a higher priority on matching individuals with jobs quickly, rather than supporting them in finding good long-term matches.

Strengthening career guidance for adults in Latin America has the potential to improve adults’ career prospects and reduce inequality. An investment in personalised advice and guidance with a holistic perspective on the lifelong career development of individuals can assist them to make informed training and occupational choices. Career guidance helps align lifelong learning opportunities to both individual preferences and needs and labour market demand. This is especially important in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic as many adults need to upskill and retrain in a changed labour market. By improving the alignment of skills development with demand in the labour market, career guidance also empowers individuals, promotes social inclusion, and ultimately supports economic development through better skills matching.

Career guidance, as defined in this report, refers to services to assist individuals of all age groups to make well-informed educational, training and occupational choices (OECD, 2021[4]; OECD, 2004[3]). Focussed on lifelong career development and learning, career guidance informs individuals about the labour market and education systems, and relates them to their own situation and available resources. It helps individuals to reflect on their strengths and abilities, as well as their qualifications and interests. Comprehensive career guidance provides assistance and advice to people to empower them to make good choices about lifelong career development and learning.

Across the globe, career guidance is known by different terms, including career development, career counselling, lifelong guidance, educational and vocational guidance and vocational psychology. In the Spanish-speaking Latin American countries, different terms are used: orientación vocacional, orientación profesional, orientación laboral, orientación a lo largo de la vida desarrollo de carrera.

Who delivers career guidance and how it is delivered vary. People offering career guidance can have training of different length and intensity. While face-to-face interviews are still a dominant channel, the provision of career guidance services has diversified in the last decades to include group discussions, printed information, advice via telephone or video call and online resources. Career guidance can be provided by educational institutions, public employment services, or companies. Services may be targeted to particular groups of adults, such as the unemployed or low-skilled, or may be open to anyone regardless of employment status.

Labour intermediation (intermediación laboral) is a related concept. The Inter-American Development Bank defined labour intermediation as “activities undertaken to improve the speed and quality of the match between available jobs, jobseekers and training. In this way, such services “intermediate” between labour supply and demand” (Mazza, 2003[21]). Labour intermediation may or may not entail speaking with a career guidance advisor or other career guidance components, such as skills assessments or training referral. As dedicated career guidance services are rare in the Latin American countries studied, this report also considers labour intermediation as a related concept that overlaps with career guidance.

References

[9] CEDLAS and The World Bank (2020), SEDLAC Statistics, https://www.cedlas.econo.unlp.edu.ar/wp/en/estadisticas/sedlac/estadisticas/#1496165509975-36a05fb8-428b (accessed on 3 December 2020).

[10] European Commission (2017), An evaluation of the scale of undeclared work in the European Union and its structural determinants, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/8c3086e9-04a7-11e8-b8f5-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 27 January 2021).

[6] ILO (2021), ILO Monitor. COVID-19 and the world of work. Seventh edition, ILO Monitor, http://moz-extension://d0d98d2f-49ef-4138-9d5f-c5fd7a7ce929/enhanced-reader.html?openApp&pdf=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ilo.org%2Fwcmsp5%2Fgroups%2Fpublic%2F---dgreports%2F---dcomm%2Fdocuments%2Fbriefingnote%2Fwcms_767028.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

[7] ILO (2020), World Employment and Social Outlook – Trends 2020.

[21] Mazza, J. (2003), Labor Intermediation Services: Considerations and Lessons for Latin America and the Caribbean from International Experience, Inter-American Development Bank, https://publications.iadb.org/en/publication/11518/labor-intermediation-services-considerations-and-lessons-latin-america-and (accessed on 25 January 2021).

[20] McKinsey Global Institute (2017), A future that works: Automation, employment and productivity, http://moz-extension://b065121f-d7a2-4bbc-af7f-0e8bdc61c772/enhanced-reader.html?openApp&pdf=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mckinsey.com%2F~%2Fmedia%2Fmckinsey%2Ffeatured%2520insights%2FDigital%2520Disruption%2FHarnessing%2520automation%2520for%2520a%2520future%2520that%2520works%2FMGI-A-future-that-works-Executive-summary.ashx (accessed on 7 December 2020).

[14] McKinsey&Company (2020), How COVID-19 has pushed companies over the technology tipping point--and transformed business forever, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/how-covid-19-has-pushed-companies-over-the-technology-tipping-point-and-transformed-business-forever (accessed on 5 February 2021).

[17] Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), “Automation, skills use and training”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/2e2f4eea-en.

[2] OECD (2021), Career Guidance for Adults in a Changing World of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/career-guidance-for-adults-in-a-changing-world-of-work_9a94bfad-en (accessed on 8 January 2021).

[4] OECD (2021), Career Guidance for Adults in a Changing World of Work, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9a94bfad-en.

[8] OECD (2020), Education at a Glance 2020: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en.

[1] OECD (2020), Effective Adult Learning Policies: Challenges and Solutions for Latin American Countries, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f6b6a726-en.

[11] OECD (2020), Latin American Economic Outlook - Digital Transformation for Building Back Better, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/publications/latin-american-economic-outlook-20725140.htm (accessed on 1 December 2020).

[12] OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: Skills for Jobs Indicators, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264277878-en.

[23] OECD (2016), OECD Employment Outlook 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2016-en.

[22] OECD (2015), Latin American Economic Outlook 2015: Education, Skills and Innovation for Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/leo-2015-en.

[3] OECD (2004), Career Guidance and Public Policy. Bridging the Gap, http://www.SourceOECD.org, (accessed on 25 January 2021).

[5] OECD et al. (2020), Latin American Economic Outlook 2020: Digital Transformation for Building Back Better, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/e6e864fb-en.

[16] Reuters (2020), Coronavirus accelerates European utilities’ digital drive, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-utilities-tech-foc-idUSKCN2560OK (accessed on 5 February 2021).

[13] The World Bank (2021), Workforce / Percent of firms identifying an inadequately educated workforce as a major constraint - GovData360, https://govdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/h8f847a5a?country=BRA&indicator=257&viz=bar_chart&years=2009 (accessed on 3 February 2021).

[15] The World Bank (2017), How countries are using edtech (including online learning, radio, television, texting) to support access to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/edutech/brief/how-countries-are-using-edtech-to-support-remote-learning-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 5 February 2021).

[18] The World Bank (2016), World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2016 (accessed on 7 December 2020).

[19] Weller, J., S. Gontero and S. Campbell (2019), Cambio tecnológico y empleo: una perspectiva latinoamericana, Cepal, http://www.cepal.org/apps (accessed on 7 December 2020).