3. Roles and responsibilities in investigating and prosecuting crimes in Latvia

This chapter analyses the roles ascribed to prosecutors and other institutions in Latvia in relation to the investigation and prosecution of crimes. It examines the role of prosecutors in bringing charges before the Courts, in pre-trial investigation and their involvement in policy making in light of comparative analysis with the OECD benchmarking countries. It emphasises the relevance of tightened co-operation between prosecutors and investigators and of making full use of the range of legal options in the Latvian legal framework to opt for simplified procedures and diversionary measures.

The role of prosecutors in society, as emphasised from the outset of the Report, is essential to uphold the rule of law and avoid a culture of impunity. It enables strengthening of public trust in institutions and has the ability to control criminality rates. These important functions, when pinned down into specific tasks, require prosecutors to perform an active role in criminal proceedings and, where provided by law, the investigation of crime or supervision of such investigation (UNODC/IAP, 2014[1]). They may also involve the protection by prosecutors of the human rights and legal precepts of all those that interact with the criminal justice system (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2015[2]).

In order to empower prosecutors in this regard, different legal systems ascribe special designations to them, such as prosecutorial discretion, the ability to decide in favour of simplified procedures or diversionary measures, or the ability to engage in criminal policy making. This chapter analyses the roles ascribed to prosecutors and other institutions in Latvia and benchmarking countries. It emphasises the relevance of tightened co-operation between prosecutors and investigators. It also highlights the importance of making full use of the range of legal options in the Latvian legal framework to opt for simplified procedures and diversionary measures.

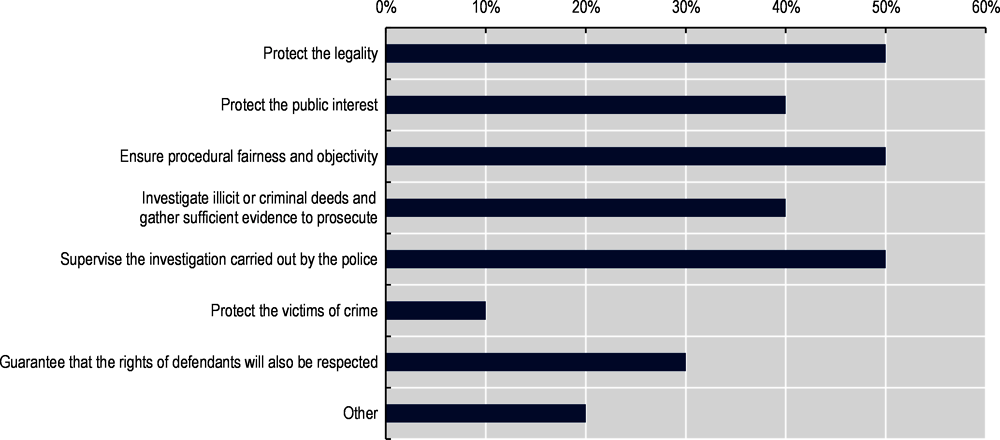

According to Article 36 (1) of the Law on Criminal Procedure of Latvia, a prosecutor supervises and carries out investigations, prosecutes, argues accusations on behalf of the state and performs other functions in criminal proceedings. Prosecutors can participate in all stages of criminal investigation. The Prosecutor’s Office may conduct pre-trial investigations and supervise investigative operations carried out by the police and other investigating institutions, initiate and conduct criminal prosecution, and supervise the enforcement of judgments. This is primarily in line with the core functions of the prosecutorial services in the benchmark countries, as shown in Figure 3.1.

The role of the prosecutor in criminal policy making and implementation

In Latvia, the Ministry of Justice plays a leading role in criminal law and criminal procedural law policy making, while the Ministry of the Interior is responsible for drafting and implementing national policy for combating crime. In addition, according to Section 65 of the Constitution of Latvia, the President of Latvia, the Cabinet of Ministers, standing committees of the Parliament, not less than five Members of the Parliament, as well as one-tenth of the electorate in cases and in accordance with the procedures provided for in the Constitution of Latvia may submit draft laws to the Parliament. Thus, in case when the performance of the Prosecution Office functions requires amendments to any of the laws, the Prosecution Office may refer a proposal for consideration of the necessity of amendments to the responsible ministry or the relevant parliamentary committee. In such a case, the ministry or parliamentary committee represents the required amendments in the form of its own proposals. The role of prosecutors in this area is thus limited to the submission of proposals to the Ministry of Justice to provide input in relation to criminal justice policies or strategies that will later be debated state-wide. The Ministry of Justice has channelled co-operation for this purpose in the form of Working Groups.1 See examples in Box 3.1.

In addition, the head of the Prosecutor’s Office (Prosecutor General) has the right to participate and engage in drafting or designing national policies and draft laws:

at the sittings of the Cabinet of Ministers by expressing his/her opinion on the issues to be considered (Section 23.5.5 of the law on the Prosecutor’s Office)

at the sittings of the Crime Prevention Council (where the Prosecutor General is a member).

The Prosecutor General is also a member of the Advisory Council of the Financial Intelligence Service (Sections 59 and 60 of the Law on the Anti-Money Laundering and Terrorist and Proliferation Financing).

The Ministry of Justice has established several working groups for drafting amendments to procedural laws to follow the procedure described above, including the permanent Working Group for Drafting Amendments to the Criminal Procedure Law (hereinafter, the “CPL”), and the prosecutors of the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Methodology Division participate in it. In addition, representatives from investigating authorities, ministries, judges (including from the Supreme Court), academia and lawyers also participate in the Working Group. At the same time, it should also be mentioned that, in the Legal Affairs Committee of the Parliament, the Prosecutor General’s Office is represented mainly by the prosecutors of the Methodology Division, that provide, if necessary, a description of the existing problem, at the same time supporting it with examples from practice, as well as respond to the questions raised by the Members of Parliament.

In 2019, the prosecutors of the Methodology Division actively participated in the development of amendments to the CPL in order to promote the investigation of financial and economic crimes, especially the investigation of criminal offences related to money laundering. In addition, the prosecutors of the Methodology Division referred to the Working Group with a proposal to review the appeal procedures for several adjudications provided for in the CPL. Prosecutors have also been involved in the development of certain legal provisions of the “Law on the Operation of Authorities During the Emergency Situation Related to the Spread of COVID-19” in the context of the pandemic. The Methodology Division also provides official opinions on drafts of the legal acts submitted by ministries to the Cabinet. When providing such opinions, a draft of the legal act is evaluated within the scope of competence of the Prosecution Office, especially by evaluating the feasibility of practical application of the developed legal provision.

Source: Prosecutor General’s Office, 2020.

As it emerged throughout the interviews, the described engagements are not formalised through law, and thus are not mandatory. This means that no formal mechanisms for co-operation between the executive and the prosecutors exist to collaborate in criminal policy making. As an institution of the judiciary, the prosecution has the opportunity to choose whether it responds to the call of the executive power for involvement. According to the findings of the examination (Senator of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Latvia, 2019[3]) carried out by the Senator of the Supreme Court in 2019, this may have the effect to limit the understanding of the Prosecutor's Office as a leading institution in shaping a uniform law enforcement practice. The recommendations of the OECD assessment of 13 March 2019 regarding the detection, investigation, and trial of criminal offences related to money laundering (Section 7) advised the prosecutors to assume primary responsibility when drafting guidelines on effective investigations of criminal cases associated with money laundering, as well as on the evidence to be obtained during the investigation. From the materials derived during the inspection, it appears that there was a disagreement among law enforcement bodies as to which authority, namely, the Ministry of Justice, the State Police, or the Office of Prosecutor General, should co-ordinate the process.

A number of stakeholders noted limited leadership shown by PGO representatives in the referred Working Groups, which could be explained by their constitutional position and regulation, which does not allocate such responsibility on the prosecution. This perception also could also correspond to the principle of separation of powers that is, that the Prosecutor's Office, as an institution belonging to the judiciary, applies the law but does not interfere in its drafting. At the same time, the law regulating the Latvian judiciary provides for the participation of courts in the drafting of laws and regulations, compilation of practice, as well as promotion of consistent case law and other functions to ensure the efficient functioning of the court.2

Involving prosecutors in the making and implementation of state criminal policy and objectives is a usual practice in the context of the OECD benchmarked countries, as well as across European states generally. Indeed, across the benchmarked countries, prosecutors and judges are consulted on draft laws affecting them or criminal justice. Paragraph 87 of Opinion no. 10 of the Consultative Council of European Judges (CCEJ) of 2007 states (emphasis added): “All draft texts relating to the status of judges, the administration of justice, procedural law and more generally, all draft legislation likely to have an impact on the judiciary, e.g. the independence of the judiciary, or which might diminish citizens' (including judges' own) guarantee of access to justice, should require the opinion of the Council for the Judiciary before deliberation by Parliament. This consultative function should be recognised by all States and affirmed by the Council of Europe as a recommendation.” (Consultative Council of European Judges, 2007[4])

In Italy, no changes to criminal policy take place if they are not consulted with the national Associations of Judges and Prosecutors, which is formally provided for. In countries where such formalised consultation is not expressly provided for, there is nevertheless some form of general consultation on draft laws or on "general guidelines" in which citizens, including judges' and prosecutors' associations, can participate. For example, when legislation is drafted in Denmark, the experts or affected parties may be consulted in giving their view on focus points and consequences. The Danish Prosecution Service is usually consulted in matters concerning criminal and procedural penal law. In certain countries, the consultation with judicial and prosecutorial councils is institutionalised. In countries where prosecutors are part of the judicial power, as is the case in Latvia, these consultations involve prosecutors as well.

Judicial Councils, as well as other types of judicial governing bodies (such as prosecutors), have generally been awarded by law the power to render opinions to the executive and the legislative on judicial policies or legislative proposals affecting the judiciary, the citizens’ access to justice, the delivery of justice through procedural laws or the independence of courts. In some cases, they also have the power to put forward proposals on their own motion to amend existing legislation or to produce new legislation on these matters.

Judicial Councils, in virtually all EU member states that have one, are awarded advisory powers on legislation concerning the judiciary and procedural laws. This is the case of Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia (at the request of the Ministry of Justice), Denmark, France (at the request of the President of the Republic or the Ministry of Justice), Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and Spain. In countries where no judicial council exists, consultations with a prosecutorial body are less institutionalised. In many countries, the judiciary, through the High Judicial Councils, is asked for assistance and comment when laws are drafted or new policies are under consideration, but not the prosecutors. In Table 3.1, some more detailed examples of Council involvement in criminal policy making and implementation will be provided.

As can be observed from the above, involvement in the drafting or design of criminal policies of the prosecution is regular practice in a majority of the benchmarked countries. If such engagement were to be increased in Latvia, it could possibly benefit the prosecution by enabling it to have a voice in the proceedings as first-hand expert practitioners, on the one hand; and to increase a sense of ownership in the achievement of criminal policy goals by prosecutors, on the other. During the interviews, it emerged that prosecutors would like to have a stronger say in particular in the reforms carried out of the criminal procedural code, in which they find several roadblocks to their daily work. A more formalised and sustained engagement of the prosecution as a stakeholder in criminal policy reforms could benefit overall efficiency and performance of the prosecution in Latvia. In addition, further detailing of the law with regard to co-operation principles with the executive and introduction of some mechanisms for engaging of the Prosecutor’s Office in achieving strategic goals of crime prevention policy could be a step considered by Latvia.

Management roles of prosecutors

In relation to self-management, there are a variety of instruments: some countries have them in the laws establishing public prosecutor's offices, others in the laws regulating the judicial and fiscal governing bodies, others in the procedural laws, etc.

With regard to the management of resources by the public prosecution services, in most countries, it is not the case, as it is the Ministry of Justice (or Interior) that is responsible for management. The exceptions are Italy and Portugal, where the Council of the Judiciary is responsible for management (Italy) or the Prosecutor General in tandem with the Council of the Public Prosecutor's Office (Portugal) manages existing resources. In France, it is the Ministry of Justice, especially the Directorate General of Justice, which manages resources, with the Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature playing a very secondary role. In the rest of the countries, the predominant role is played by the Ministry of Justice. In the Latvian institutional system, the resources of the Prosecutor’s Office (that is, the resources of prosecutors are not separated and cannot be separated from the resources of the institution) are managed directly by the Prosecutor’s Office, with the head of the institution, the Prosecutor General, being fully accountable. Following Section 19.6 of the Law on Budget and Financial Management, the Ministry of Justice compiles budget requests submitted by courts and forwards them to the Ministry of Finance, whereas the Prosecutor General’s Office compiles and forwards budget requests submitted by prosecution services.

It should be borne in mind that the Council of Europe Recommendation (2000)19 safeguards national traditions in the organisation of the public prosecutor's office. It should also be taken into account that this Recommendation, and many others from the Council of Europe, originate from recommendations of prosecutors and judges. A highly influential model has been the Italian Council of the Magistracy, which has been widely adopted as the "European model" and entails a strong self-management component for resources of judicial and prosecution systems. As such, it has grown in importance, including by recommendation of the Council of Europe and through it to the European Commission and the new member countries of the European Union from the east, except for the Czech Republic. Despite its growth, some systems are experiencing difficulties with this model that have included corruption, nepotism, arbitrary appointments, and patronage, as they came from a tradition of management by the Ministry of Justice. Despite its issues, it is worth noting that the Italian model originated in a system where not only judges but also prosecutors have complete individual independence, including at the vertical level with no hierarchical control. In some cases, this model has been transferred to a country where the system is hierarchical, without taking full account of this difference. As such, to be effective, this model should be accompanied by sound mechanisms ensuring transparency and accountability.

Roles and responsibilities in pre-trial investigation in Latvia

Criminal investigations in Latvia are mainly the responsibility of three criminal investigation bodies:

The State Police, under the authority of the Ministry of Interior.

The Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau (usually known as “KNAB”, per its Latvian acronym), under supervision of the Cabinet of Ministers executed by the Prime Minister.

The Tax and Customs Police Department, which is a unit of the State Revenue Service (which is, in turn, an institution of direct administration under the supervision of the Minister for Finance).

The Financial Intelligence Unit of Latvia (hereinafter “FIU Latvia”) should also be mentioned in this context, despite the fact that it does not carry out investigations. It is an institution especially established under the supervision of the Cabinet of Ministers through the Minister of Interior which receives, processes, and analyses reports on suspicious financial transactions as well as, in cases provided for in the law, provides this information to control, pre-trial investigation, and court authorities as well as to the Prosecutor’s Office. In addition, according to Section 386 of the Criminal Procedural Law, the Security Police, the Internal Security Department of the State Revenue Service, the Military Police, the Latvian Prison Administration, the State Border Guard, the captains of seagoing vessels at sea, the commander of a unit of the Latvian National Armed Forces located in the territory of a foreign country, and the Internal Security Bureau are also charged with certain criminal investigation functions.

The work carried out by the Ministry of Finance coincides across several areas with that of the prosecutors, in particular in relation to anti-money laundering and the “AFCOS” programme (a programme established under the responsibility of OLAF to protect the financial interest of the European Union in Member States).

On the other hand, functions of the Prosecutor's Office in Latvia in a pre-trial investigation are laid down in article 2 of the Law on the Office of the Public Prosecutor whereby the Office of the Public Prosecutor:

supervises the compliance with legal enactments of the preliminary investigation and intelligence activities, reconnaissance and counterintelligence processes of the national security institutions and of the system for protection of state secrets

conducts the pre-trial investigation (only if the case is very complex or the police fails)

protects the rights and legitimate interests of persons and the State in accordance with the procedure prescribed by law

submits a complaint or a motion to the Court in cases provided for by the law

takes part in the court hearings in cases provided for by the law.

On the other hand, State Police investigators are in charge of specific criminal cases, being able to prescribe the investigative actions to verify that a criminal offence has occurred and who has committed it, obtains evidence that gives grounds for indicting an offender for a crime, and chooses a type of criminal procedure that ensures a fair resolution of criminal justice, along with any specific criminal procedural steps. A similar role and tasks are associated with the specialised bodies including KNAB (which carries out such investigation for corruption-related offenses), The Tax and Customs Police (investigating tax crimes), and finally the FIU, which specialises in sensitive investigations including suspicious financial transactions on money laundering and terrorism financing. Table 3.2 provides a summary of the responsibilities of each of the actors described above.

The current allocation of responsibilities between prosecutors and investigators primarily appear to be the result of the amendments to the Criminal Procedural Law carried out in 2005, specifically through article 27-2, which stipulates that the supervising prosecutor is obliged to give instructions only if the investigator does not ensure a purposeful investigation and allows unjustified interference in the life of an individual or delay. Prior to that, the Criminal Procedure Code stipulated that the supervising prosecutor instructed the investigator on the progress of the investigation and the performance of specific investigative actions. Therefore, the 2005 law amendment appears to have given the prosecutor a vicarious character regarding the investigators, which, in the course of time, may have contributed to a relative distance of the prosecutors from the investigation.

At the same time, article 12 of the Prosecutors’ Office Law highlights the supervisory functions of the prosecutor over the compliance with legal enactments of the preliminary investigation and intelligence activity.3 The Order of the Prosecutor General determining the roles of the police and prosecutors also states that from the first day of an investigation the supervising prosecutor must ensure the control of the investigation. The Order also determines that the prosecutor can annul an act or decision of the investigator, whereas this latter can appeal to a higher prosecutor. The appeal by an investigator to a higher prosecutor may not necessarily be the way to solve the issue, as it may in fact cause further delays. An investigator who is overruled has no personal interest to defend the case, without prejudice to the possibility to raise concerns when an investigation is unlikely to be fruitful, or to propose to resume it if further evidence should come to light. Thus, it would be preferable to possibly limit the right to appeal decisions of prosecutors by investigators, while at the same time ensuring an early involvement of the prosecutor in pre-trial investigations, so necessary guidance can be given. In sum, the legal framework leaves relative ambiguity with regard to the level of involvement of the prosecutor in the pre-trial process.

There is a need to clarify the scope of prosecutor involvement in pre-trial investigation to align with practices in benchmarking countries

In view of the above institutional design described, the Latvian prosecution system seems well placed in regards to its overall structure to act effectively. The existing institutions and teams do not display dysfunctionalities in relation to their OECD benchmarked counterparts. Some aspects offer scope for improvement, which the following analysis will focus on. In particular, the creation of an increased co-ordination and clarification of responsibilities and burden of proof standards between prosecutors and investigators could significantly improve efficiency and effectiveness in pre-trial investigation - as identified by a wide range of interviewed stakeholders, including both prosecutors and investigators themselves.

Given that the current legal framework appears to encourage prosecutors to intervene in the pre-trial investigation process only as necessary, it creates a situation where investigators often work autonomously and prosecutors appear detached, especially from the beginning of the investigation, despite having the supervisory authority from the outset. Such authority includes a possibility to rule on the admissibility of evidence and on the need for additional/different investigative actions. This creates a co-ordination and co-operation challenge when the prosecutorial supervision is often perceived to be formalistic and intermittent, with often unclear roles and responsibilities during the pre-trial investigation. This can lead to the loss of time on investigations which have little or no prospect of a successful outcome. It also creates limited opportunities for the co-operation between prosecutors and investigators, except on serious criminal offenses, thus possibly undermining the effectiveness of the Latvian criminal justice system. Recommendations to improve co-ordination between the prosecutors and KNAB were also part of the Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in Latvia Phase 2 (recommendation 9(a) (OECD, 2015[5]) and Phase 3 (recommendation 6(a) (OECD, 2019[6])) Reports.

From the benchmarking perspective, in countries where investigative magistrates (judges) conduct the pre-trial investigations (known as ‘instructions’), they are involved in the investigation from the very beginning, since the end of the habeas corpus term (usually 36 or 48 hours from the arrest of the suspect, moment when the police become fully subordinated to the investigating judge). On the other hand, in countries where a total split exists between investigation and prosecution prosecutors do not intervene at all in investigation beyond some occasional co-operation. But prosecutors do not have any supervisory role of the investigation. Finally, in countries where only prosecutors lead the investigation, the police are subordinate to the prosecution direction from the very beginning of the investigation. The situation in Latvia is ambiguous concerning the distribution of responsibilities between prosecutors and investigators, which can hamper the functioning of the criminal justice system. Table 3.3 illustrates the relationship between investigation and prosecution in the benchmark countries in conducting pre-trial investigations:

There is also scope to enhance the quality of the broader pre-trial investigation process

More broadly, a number of stakeholders, including the State Audit Office, identified several additional considerations for pre-trial investigations, such as the insufficient qualification of the involved parties, relatively negative attitude of prosecutors to providing instructions to investigators, unclear distribution of roles of the officials participating in criminal proceedings, and the heterogeneous understanding of the criminal procedures by investigators and prosecutors.

For example, investigators and their immediate superiors tend to highlight the fact that supervising prosecutors are often insufficiently knowledgeable about the specifics of economic and financial crimes, while they are to decide whether the evidence gathered is enough or not to write the arraignment. The interviewed stakeholders identified the need for more joint training of investigators, prosecutors and judges as well as informal venues where to discuss and building a shared understanding of substantial and procedural issues. Indeed, in 2017, the State Audit Office proposed an enhanced co-operation between police and prosecutors, especially in financial crimes, which are very sophisticated and complex. This proposal has not been fully heeded.

They also note the instructions to investigators to carry out additional investigative actions late in the process, thus possibly contributing to the unnecessary delay of the pre-trial investigation. Discrepancies between prosecutors and investigators on the “sufficiency of the evidence” gathered appear to serve as another important hindrance for the smooth performance of the Latvian criminal justice system. According to the stakeholder interviews, prosecutors seem reluctant to prosecute if there are not enough guarantees (i.e. enough evidence) to reach a conviction. There is manifest operational discrepancy between investigators and prosecutors on the interpretation of article 401 of the Law on Criminal Procedure on when an investigation should be considered as completed from the point of view of the necessary amount of evidence to reach the burden of proof that would achieve conviction. Likewise, discrepancies also reach the extent of article 394 on tasks prosecutors can demand from investigators. There is limited regulatory base to determine when the evidence gathered by investigators is enough. This leads to many cases being suspended and remain so for a long time, as the principle of legality prevents prosecutors from dropping the case. As a result, it appears that the ratio of cases being brought to the court by prosecutors appears is low in comparison to those being investigated (see for example in Annex B, the available statistics for the Prosecutor’s Office for investigating financial and economic crimes, whereby 288 investigations are being supervised by prosecutors, only 2 are being prosecuted and 8 have reached the accusation stage), being cited by interviewees as achieving a 99% conviction rate. Harmonisation of practice on the evidentiary threshold and steps to perform for each type of offense could support enhanced co-operation (see the discussion on standardisation in Chapter 4).

In addition, whereas a number of domestic actors in the Latvian criminal justice system tend to highlight the role of the legislation as the main cause for the uneven performance of the criminal justice system, external observers often note that while some improvements in the legal frameworks could be helpful, the primary efforts for improvement should focus on strengthening the application of the law and implementation of the legal framework by the Latvian State (i.e. police, prosecutors and judges).

While a number of stakeholders highlighted that investigators and prosecutors should be working in unison from the commencement of investigations, nevertheless, from the interviews held by the OECD, it is unclear at this point whether the role of prosecutors in pre-trial investigations should be increased or decreased. More involvement was requested by investigators, including the obligation to co-operate or to be involved at an earlier stage, to better guide them and avoid cases sent back and delays. On the contrary leaving investigation responsibilities primarily to the police in certain cases could ensure the prosecutors will focus on prosecuting crimes, and on investigating the most complex crimes only. An optimal balance, but one that should include an initial meeting between the supervising prosecutor and the investigator assigned to a given case to co-ordinate on the steps to be taken and calculate a timeframe for the investigation, may bear combination of both. This could be useful to reduce workloads based on supervision, and allowing the necessary space for prosecutors to actually prosecute complex crimes. It could also allow to enhance efficiency, as was the case in a number of OECD countries represented in the benchmark. In any event, it appears essential to clarify and adjust the current approach or focus of the prosecutor in pre-trial investigations in Latvia. The Danish, Finnish and Norwegian models of prosecutions conducted by the police, as highlighted in the table above, could offer relevant practices for Latvia.

Considerations for determining prosecutor’s discretion to prosecute

Increasingly, decisions in criminal justice systems in OECD countries are being brought out of courts to prosecutorial-made settlements, which often is due to the fact that traditional court designs cannot cope with the increased criminality in terms both of numbers and sophistication. The thrust is solving problems as quickly and cheaply as possible.

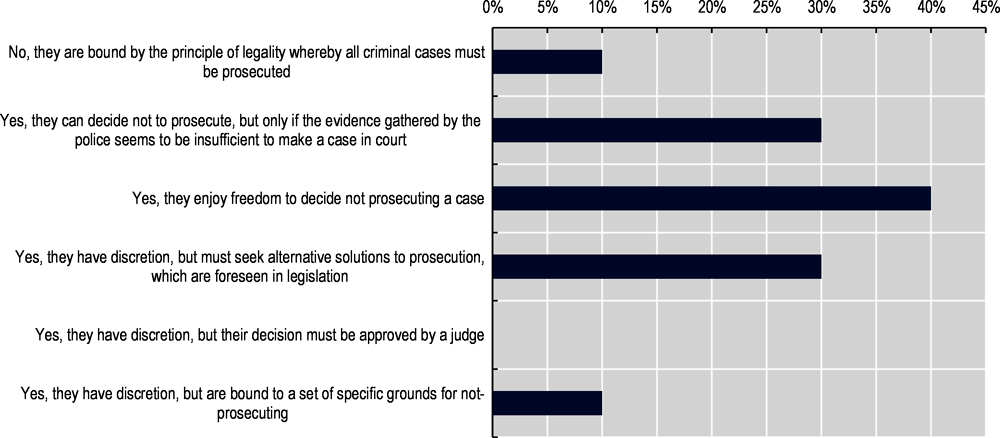

The finalisation of pre-trial investigation may have many forms and carried out in many ways. Whatever the modalities of ending the investigation it has deep impacts on the efficiency and economy of the criminal justice system. In Latvia, the Criminal Procedure Law (Section 6) enshrines the mandatory nature of criminal proceedings, otherwise known as the principle of legality. It enshrines the task of the Prosecution Office to respond to any violation of law and to ensure the review of the case related to the said violation in accordance with the procedure laid down by the law. Thus, pre-trial investigations may end in the ways described below, apart from lodging the arraignment in court. As in other countries in which the principle of legality in criminal proceedings prevails, the principle of opportunity (prosecutors have discretion to prosecute a case or not depending on various factors, including the likelihood of conviction or the relevance of the case) appears in use under some circumstances.

In Latvia, the prosecutor may terminate criminal proceedings after the receipt thereof without the initiation of criminal prosecution if there are specific circumstances provided for by law (there was a minor offense committed, a settlement has been concluded, etc.). The Criminal Procedure Law allows for simplified criminal proceedings such as the prosecutor’s penal order without court approval for less serious crimes (article 420) or urgent procedures for flagrant crimes (article 424). These allow a prioritisation of resources, as opposed to the longer ordinary procedure, which is largely used in practice. Likewise, the Law provides for summary procedures for investigations if completed within ten days and if the perpetrator is identified (article 428). Plea bargaining (called “agreement in pre-trial criminal proceedings”) concluded by the prosecutor and approved by the court is also admitted by article 433 of the Latvian Criminal Procedural Law. In addition, there are provisions allowing terminating criminal cases – Section 392 of the Criminal Procedure Law: if proving guilt of a specific suspect in committing a criminal offence has not been successful in pre-trial proceedings, and gathering additional evidence is not possible, the investigator, with a consent of the supervising prosecutor, or the higher-level prosecutor, can make a decision to terminate the criminal proceedings. If the proceedings are terminated in the part against a person, the pre-trial proceedings continue. An investigator may also, with the consent of the supervising prosecutor, terminate criminal proceedings for a minor criminal offence if he has failed to identify the person who committed it (entered into force on 6 July 2020). On 1 January 2021, a new provision will enter into force (Section 392 2.2 of the Criminal Procedure Law) stipulating that an investigator may, with the consent of the supervising prosecutor or with the agreement of a senior prosecutor in criminal proceedings for money laundering, make a decision on the termination of criminal proceedings if confiscation of crime proceeds has been achieved, the guilt of the person committing the criminal offence has not been proven in the pre-trial proceedings, and gathering additional evidence will not ensure economic pre-trial criminal proceedings, or costs will be disproportionately high.

After the initiation of criminal prosecution, the prosecutor is provided with an even wider range of possibilities to complete the criminal proceedings without forwarding cases to court. Across the OECD countries benchmarked, half of the systems make use of the principle of opportunity, while the rest are bound by the one of legality (the one applied in Latvia), as follows:

The deployment of both principles is constitutionally legitimate and there is not a clear positive or negative effect on performance of using one or the other across the benchmarked countries. However, some argue that the opportunity principle does not ensure equality before the law. Nonetheless, and for both types of systems, the UN Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors (18) advise that, in accordance with national law, prosecutors should give due consideration to waiving prosecution, discontinuing proceedings conditionally or unconditionally, or diverting criminal cases from the formal justice system. For this purpose, States should fully explore the possibility of adopting diversion schemes not only to alleviate excessive court loads, but also to avoid the stigmatisation of pretrial detention, indictment and conviction, as well as the possible adverse effects of imprisonment. The IAP Standards (4.3 h) contain a very similar encouragement to prosecutors to give due consideration to waiving or diverting prosecution where such action is appropriate and with due respect for the victims. What may be interesting for Latvia are some the particularities of each system and the way that cases can be closed without following a full ordinary procedure. Examples may be drawn from these systems to integrate reforms in Latvia that enable seamless diversion of cases towards different dispute resolution avenues, or speedier closing of non-promising procedures (See Box 3.2).

The Italian criminal system is bound by the principle of legality, as stated in article 112 of the Constitution. Nevertheless, room for discretion of the prosecutor is opened for cases in which the penalty can be imposed without trial: the sentence agreement (patteggiamento) where an agreement between the prosecutor and the offender on the sentence to be imposed and the penal order (procedimento per decreto), when the proceeding ends with the issuing of a penal order to pay a fine.

In Portugal, an investigation can terminate if sufficient evidence is lacking, the perpetrator is unknown, or the crime was not committed. The use of alternatives to punishment in view of the country’s criminal structure (about 70% of which small and less serious crime) is gaining currency and diversionary measures are being progressively introduced. There are simplified and consensual forms of proceedings laid down in the Criminal Procedure Code. These are: sumário (summary proceeding), sumaríssimo (highly summarised proceeding), abreviado (shortened proceeding) and suspensão provisória do processo (provisional suspension of the criminal proceedings).

In Sweden, there are four different ways in which prosecution of offences can be terminated (or not initiated at all) before the case would reach the court, i.e. cases in which the conviction of the suspect could be expected:

The police refrain from prosecution of petty offences which is allowed by the Law on Police.

A preliminary investigation may be discontinued by the prosecutor if continuing the inquiry would incur costs unreasonable regarding the importance of the matter and, at the same time, the offence, if prosecuted, would not lead to a penalty more severe than a fine. Even if the public interest is not named expressis verbis in this provision, the public interest is the main rationale of the provision.

The waiver of prosecution (åtalsunderlåtelse) is possible a) if it may be presumed that the offence would not result in any other sanction than a fine; (b) if it may be presumed that the sanction would be a conditional sentence and special reasons justify waiver of prosecution; and (c) if, in view of the circumstances, it is manifest that no sanction is required to prevent the suspect from further criminal activity or the institution of a prosecution is not required for other reasons. The decision to waiver prosecution is recorded in the criminal register of the suspect. The number of waivers of prosecution is also recorded in criminal statistics as successfully finished prosecutions of persons who committed crime, alongside the number of judgments and penal orders. The waiver requires the offender to plead guilty.

Sanctioning offences through decisions of the prosecutor or the police. These are the penal orders (imposed by the prosecutor) and the summary fines order (imposed by the police). These instruments also require the offender to plead guilty. These instruments are controversial but have been successful in significantly reducing the workload of the courts. A satisfactory balance is still to be achieved.1

Useful experience from opportunity principle systems

Denmark applies the principle of opportunity or expediency and therefore priorities in investigation and prosecution may be established, but neither the Procedural Code nor the Penal Code allow prosecutors the option of settling cases by agreement (plea bargaining and its equivalents). However, it remains for the prosecution to decide which cases warrant being brought before the courts based on the likelihood of achieving a conviction and also on the rational use of available resources, both by prosecution authorities and by the police authorities.

In France, when an offense is committed and its perpetrator is identified, the prosecutor can decide: 1) to close the case, relying on the opportunity principle (because of the little amount of the prejudice, situation of the perpetrator, and so forth); 2) various modalities of alternative measures to prosecution 3) penal composition measures for offences punishable with less than 5 years imprisonment (the penal composition may consist of a penal order, fine, or other measures such as courses related to the crime in order to be sensitised of consequences of it, care obligation, prohibition to meet someone or go somewhere, giving for a determined period his driving licence or hunting licence, or execution of unpaid work), that needs to be accepted by the defendant and approved by a judge. It is a criminal settlement foreseen in the article 41-2 and 41-3 of the Code of Criminal Procedure; 4) Deferred Prosecution Agreement, known in French as Convention Judiciaire d’Intérêt Public (CJIP), a non-criminal financial penalty for corporate corruption-related criminal offences, approved by a judge; 5) prosecution against the perpetrator in simplified terms: without a hearing, by penal order (on a proposal for a sentence from the prosecution); by appearance on prior admission of guilt, known in French as Comparution sur reconnaissance préalable de culpabilité (with a hearing to approve the proposed sentence negotiated by the prosecution and it has to be approved by a judge); 6) ordinary proceedings before the criminal court; 7) Referral to an Investigating Judge in order to open a Judicial Information.

In Ireland, the principle of opportunity is applied too. Discretion includes not only the power to decide whether to initiate a prosecution but the power to terminate it at any stage of the proceedings before the verdict is announced, including a summary prosecution commenced by the Garda (police) in the DPP’s name which is now the only manner in which the police may prosecute. The DPP has, however, no power either to require or to prevent the police from carrying out a criminal investigation. In the case of indictable offences brought at the suit of the Director, the decision to prosecute or not is taken by the Director personally or by an officer of the Director who is authorised to take such a decision. As in other common law systems, a fundamental consideration when deciding whether to prosecute is whether to do so would be in the public interest. A prosecution should be initiated or continued if prosecuting it is prima facie in the public interest. A prosecution should not be brought forward where the likelihood of a conviction is effectively non-existent. Where the likelihood of conviction is low, other factors, including the seriousness of the offence, may come into play in deciding whether to prosecute. However, this does not mean that only cases perceived as ‘strong’ should be prosecuted. The assessment of the prospects of conviction should also reflect the central role of the courts in the criminal justice system in determining guilt or innocence (Department of Public Prosecutions of Ireland, 2019[7]). “Deferred prosecution agreements” are not allowed but lobbying for introducing them is mounting (Dillon Eustace, December 2018[8]). The Law Reform Commission also recommends that a statutory scheme of deferred prosecution agreements should be introduced in Ireland, under the control of the Director of Public Prosecutions.2 Two main diversionary programmes exist: the Garda Síochána Adult Caution Scheme and the Irish Youth Justice Service.

In addition for the case of Ireland, because the country lacks a system of administrative law, much of the enforcement which would be done through the use of administrative penalties in much of the rest of Europe is in Ireland carried our through the creation of minor offences most of which are tried summarily and prosecuted by Government Departments or specialised agencies rather than by the prosecution, who concentrates on core indictable crime. Thus, most environmental offences are prosecuted by the Environmental Protection Agency or by planning authorities, and competition law is enforced by the Competition Authority; and road traffic offences are the responsibility of the Department of Transport. Where serious offences in these areas are involved, the prosecution takes charge.

In the Netherlands, prosecutors enjoy freedom to decide not prosecuting a case. The expediency or opportunity principle is established in article 167-2 of the Criminal Procedure Code: “a decision not to prosecute may be taken on grounds of public interest”. A prosecutor thus has various options for disposing of a criminal case because of the opportunity principle which governs the Dutch prosecutorial policy and law. These options are: 1) Imposing a sanction or ‘penal order’. The prosecutor can dispose of minor criminal cases, such as criminal damage, vandalism, shoplifting and traffic violations, by imposing a sanction (strafbeschikking). Accordingly, the case is not brought before the court, but sanctioned by the prosecutor. 2) Payment in lieu of prosecution (transactie). This is a proposal from the prosecutor. If the person agrees and pays, the prosecution will not proceed any further. Failure to pay means the person will have to appear in court after all. If the person wants to bring the case before court, he or she can decline the proposal. This mechanism of transaction is applicable to crimes punishable with less than a six-year prison sentence. 3) Decision not to prosecute: Sometimes, the public prosecutor decides not to prosecute a case (sepot). This may occur if there is, for instance, insufficient evidence to achieve a conviction or if the suspect has not been identified. A victim may object to a decision not to prosecute by lodging a complaint with the Court of Appeal. 4) Conditional decision not to prosecute: The public prosecutor may also attach conditions to the decision not to prosecute, and the perpetrator must abide by these conditions. A person may, for example, agree not to enter the street where his victim lives. If they do not stick to the agreement a sanction will be imposed after all. This mechanism is equivalent to a suspension of the prosecution. If the public prosecutor decides that none of these options are applicable, the suspect must appear before a criminal court. The Board of Prosecutors General has established guidelines (Instructions, or Aanwijzingen) for prosecutors to waive (sepot) prosecution for reasons of public interest (article 167-2 of the Penal Procedural Code).

In Norway, where the principle of legality prevails, police prosecutors and public prosecutors may drop a case on grounds of lack of or insufficient evidence, unknown perpetrator, that the described deed in the complaint is not punishable, absence of reasonable ground to start an investigation, that the perpetrator is under 15 years, and that the deed is not punishable due to qualified provocation. The district police must decide in accordance with the general instructions in circulars and directives from the Director of Public Prosecutions and the local public prosecutor’s office. It is the public prosecutor’s task to supervise the activities through control and inspections. Administrative decisions on to prosecute or not can be appealed. Plea bargaining is not recognised in the Norwegian criminal justice system. The mediation has gained currency within the criminal justice system. The idea of a mediation board emerged in the late 1970s and the first pilot project was implemented in 1981. After this, the scheme has evolved and is currently the main supplier of "restorative justice", while the prosecuting authority is the main supplier of cases to the mediation board.3 It has become a most effective diversionary measure from prosecution. Key elements of the concept are that the parties affected by a conflict or an offence participate in a process where the offenders will be encouraged to understand the consequences of their actions and to take responsibility for them, and that the victim should be able to tell the perpetrator directly how the crime has impacted him/her. With the mediator’s help, together they will find the best way of repairing the harm. The prosecuting authority's transfer of cases to the mediation board is a prosecution decision pursuant to Section 71-a of the Criminal Procedure Act. One condition is that the case is suitable for mediation and that a more severe reaction is not called for in the interests of acting as a general deterrent. Furthermore, there must be a victim or injured party.

In New Zealand, prosecutors may decide not to prosecute, but that decision must be justified through the evidence test and the public interest test, as established in the Solicitor-General’s Prosecution Guidelines. Once a prosecutor is satisfied that there is sufficient evidence to provide a reasonable prospect of conviction (evidence test), the next consideration is whether the public interest requires a prosecution (public interest test). It is not the rule that all offences for which there is sufficient evidence must be prosecuted. Prosecutors must exercise their discretion as to whether a prosecution is required in the public interest. The Police Prosecution Service may also decide to divert the cases to one of the alternative action schemes administered by the police such as the Adult Diversion Scheme or options under the Youth Justice system.

← 1. See (Zila, J., 2006[9]). The author states that “The combination of wide discretion together with the already mentioned fact that drawing up a penal order is labour-saving in comparison with prosecution in court requires high personal integrity among prosecutors” (page 406).

← 2. The Commission, appointed by the Government, is an independent body established under the Law Reform Commission Act 1975, which states that the Commission's role is to keep the law under review and to conduct research with a view to the reform of the law. See Issues Paper on Suspended Sentences.

← 3. See http://www.justicereparatrice.org/www.restorativejustice.org/editions/2001/Dec01/Norway. See also Recommendation No. R (99) 19 adopted by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on 15 September 1999 and explanatory memorandum (https://www.euromed-justice.eu/en/system/files/20100715121918_RecommendationNo.R%2899%2919_EN.pdf).

In sum, the criminal justice legal framework in Latvia offers a broad spectrum of procedural choices that can be used to increase efficiency. These include the use of simplified procedures, the employment of diversionary measures and ways to terminate investigations that are foreseen to be fruitless if, for instance, suspects are not identifiable and no more evidence can be discovered. There are also opportunities in Latvia’s legal framework to benefit from the principle of opportunity in order to strengthen prioritisation, which could become part of the standard prosecutorial work procedure. The police and prosecutorial services can fully avail themselves of these options to improve efficiency of the system.

References

[4] Consultative Council of European Judges (2007), “Opinion no. 10”, p. para. 87, https://rm.coe.int/168074779b.

[7] Department of Public Prosecutions of Ireland (2019), “Guidelines for Prosecutors, 5th edition”, https://www.dppireland.ie/app/uploads/2019/12/Guidelines-for-Prosecutors-5th-Edition-eng.pdf.

[8] Dillon Eustace (December 2018), “Regulatory Investigations Quarterly Update No. 9”, http://financedublin.com/pdfs/Dillon_Eustace_Regulatory_Investigations_Quarterly_Update_9.pdf.

[6] OECD (2019), Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention. Phase 3 Report: Latvia, https://www.oecd.org/corruption/anti-bribery/OECD-Latvia-Phase-3-Report-ENG.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2020).

[5] OECD (2015), “Phase 2 Report on Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in Latvia”, http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/Latvia-Phase-2-Report-ENG.pdf.

[3] Senator of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Latvia (2019), “Report of Senator of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Latvia Ms Marika Senkāne of on the results of the inspection of the grounds for dismissal of the Prosecutor General”.

[2] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2015), “United Nations Convention against Corruption: article 11 implementation guide and evaluative framework”, Vol. para. 161, https://www.unodc.org/documents/corruption/Publications/2014/Implementation_Guide_and_Evaluative_Framework_for_Article_11_-_English.pdf.

[1] UNODC/IAP (2014), The Status and Role of Prosecutors: A United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and International Association of Prosecutors Guide, United Nations, https://www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-prison-reform/HB_role_and_status_prosecutors_14-05222_Ebook.pdf.

[9] Zila, J. (2006), “The Prosecution Service Function within the Swedish Criminal Justice System. In: Coping with Overloaded Criminal Justice Systems.”, pp. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-33963-2_9.

Notes

← 1. Latvia answers to the questionnaire. This collaboration is not established by law.

← 2. See, for example, Clauses 3, 4.2, Part 3, Section 33 and Part 3, Section 40 of the Law on Judicial Power.

← 3. Prosecutor shall exercise supervision over the compliance with legal enactments of the preliminary investigation and intelligence activities, reconnaissance and counterintelligence processes of the national security institutions and of the system for protection of the state secret.