4. Unemployment and related benefits in Bulgaria

A critical component of activation policies concerns the incentives that people face to become formally employed or to remain in employment. The tax and benefit system must strike the right balance of maintaining incentives to work and cost-effectiveness while ensuring income support for vulnerable individuals. This chapter examines how well Bulgaria’s tax and benefit system strikes this balance, with a focus on unemployment insurance, social assistance, and related benefits available to unemployed and inactive people. In addition to examining these benefits and how well targeted they are, this chapter also discusses briefly the overall effects of Bulgaria’s tax and transfer system on inequality.

The incentives people face to become employed are a critical component of activation policies. The tax and benefit system aims to redistribute income, to alleviate poverty, to reduce inequalities, and to smooth consumption in addition to the goal of collecting revenue to fund government spending. The tax and benefit system also impacts directly on incentives to work. This chapter assesses how Bulgaria’s tax and benefit system supports the out-of-work while maintaining good incentives to work.

Other factors that influence incentives for work include opportunities provided by the overall labour market situation (see Chapter 2) as well as individual’s human capital (see Chapter 3). A further, crucial consideration concerning incentives are activation related eligibility rules tied to benefit receipt. Such rules require jobseekers to search for and not refuse jobs or else face sanctions on their benefit receipt. These eligibility rules are discussed in Chapter 5.

Section 4.2 begins with an overview of Bulgaria’s benefits for those out-of-work: detailing especially the rules, durations, and amounts for unemployment insurance and social assistance while briefly describing available invalidity benefits and benefits for families. Following this, Section 4.3 examines the effects the benefit system has on incentives for work and alleviating poverty. Finally, Section 4.4 concludes with key findings.

The decisions governments make around who is entitled to claim out-of-work benefits, the amount people receive, and the duration people can claim them for, affect how well the benefit system reduces poverty and inequality while maintaining incentives to work. This section details the system of unemployment insurance, social assistance, and related benefits for those out-of-work, while the next section looks at the effects of the system on incentives and inequality.

Income-support for unemployed individuals in Bulgaria is provided primarily through a two-tiered system through the benefits of:

Contributory unemployment insurance (Обезщетение за безработица) which is not means-tested but requires a minimum period of social security contributions.

Social assistance (Социална помощ) and the heating allowance (целева помощ за отопление), which are means tested and targeted towards low income families but are not dependent on social security contributions.

4.2.1. Unemployment insurance (Обезщетение за безработица)

This section details Bulgaria’s unemployment insurance: durations, amounts, entitlement rules and coverage.

Unemployment insurance amounts are generous

Recipients of unemployment insurance receive a standard rate of 60% of contributory income (averaged over the last 24 months). The minimum amount is BGN 9.12 (EUR 4.6) per day (or BGN 195 (EUR 99.7) per month). The maximum amount is BGN 74.29 (EUR 37.8) per day (BGN 1 609.6 (EUR 823) per month. By international standards the 60% replacement rate is high and amounts to 77% net of tax and social security contributions for a single person without children (Figure 4.1). However, there are exceptions to the “standard” 60% rate. If employment ended voluntarily or as a result of misconduct, then the minimum unemployment insurance is paid.1

Unemployment insurance duration and coverage are modest

Recipients of unemployment insurance must have contributed to the scheme for a minimum of 12 out of the last 18 months to receive payments. For those with less than three years of contributions, unemployment insurance is paid for just four months and it is paid for a maximum of 12 months for those with at least 15 years of contributions. In the case of voluntary quits, the duration is also reduced to the minimum four months. The 12 month maximum duration is similar to many countries in the OECD. The approximate median entitlement duration for claimants is eight months and about a third of people have less than six months of eligibility (Table 4.1). (These durations are approximate, see note to Table 4.1).

Unemployment insurance payments cease when recipients find jobs. The one exception is for low paid part-time jobs with total earnings less than the full-time national minimum wage. In this case recipients can claim 50% of their remaining unemployment insurance benefit – which is paid out as a re-employment allowance (Обезщетение за безработица на лица наети на непълно работно време).

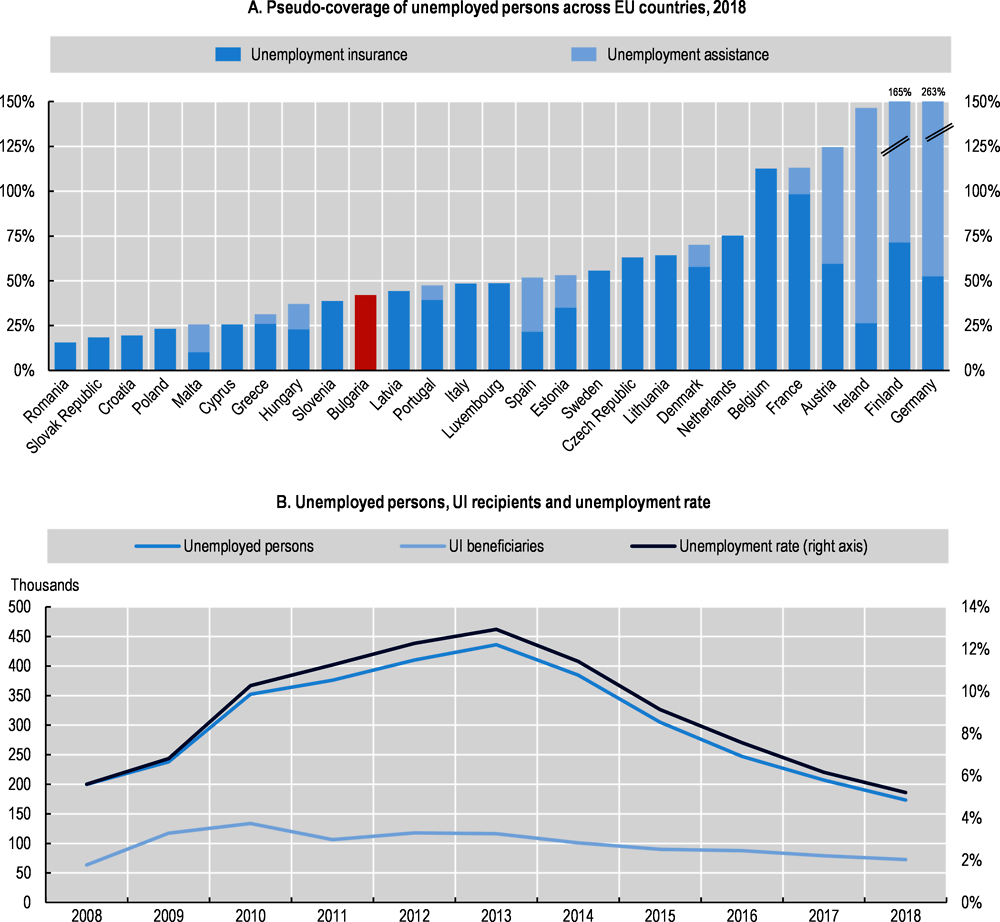

Benefit durations and entitlement criteria are challenging to compare across countries. One way to compare entitlement and duration generosity is to look at “pseudo-coverage”. Pseudo-coverage is defined as the total number of people on unemployment benefits over the total number of unemployed people (as measured by the Labour Force Survey). Because the numerator and denominator come from different data sources and do not fully overlap “pseudo-coverage” provides only a rough approximation of the percentage of unemployed people who receive unemployment support. For example, some people who are not actively searching for employment (i.e. not identified as unemployed in the LFS) may receive unemployment benefits, while others who are unemployed may not receive benefits either because they are not entitled to such benefits or because they do not claim benefits they are entitled to. The degree of these issues can vary across countries for various reasons including policy settings (e.g. in Finland and Germany pseudo-coverage rates exceed 100% reflecting that many people who are not actively searching for work are able to claim benefits). However, pseudo-coverage is still useful as it can be easily calculated and compared across countries.

Bulgaria’s pseudo-coverage rate is below the median EU country (Figure 4.2, Panel A). Panel B of Figure 4.2 shows that unemployment insurance claimants in Bulgaria rose during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) but not nearly by as much as unemployment rates did. This likely reflects that many people who were out of work following the GFC were not eligible for or had exhausted their unemployment insurance before finding a job.

Disadvantaged groups get less unemployment insurance and for less time

As discussed above, the amount and duration of unemployment insurance depends on contributions lengths and the level of prior earnings, as well as the reason for leaving a job and prior unemployment insurance claims. Rules of this type are the nature of an unemployment insurance scheme. However, they also entail that those with less stable employment, as well as those who have only recently joined the labour force, can get lower amounts of unemployment insurance for less time. These groups will then be more reliant on means-tested social assistance, which is discussed in the next section.

By analysing detailed micro-data provided by the National Employment Agency (NEA) on more than 244 000 people claiming unemployment insurance between January and September 2020 it is possible to quantify the different amounts different groups receive. Table 4.1 shows the daily amount in BGN that people from different groups actually receive. The analysis provides a detailed understanding of unemployment insurance receipt by looking across many different demographic groups defined by ethnicity, education, health status, age, and gender. Table 4.1 also shows how frequently the minimum and maximum payments are applied and whether people are eligible for at least six months of unemployment insurance.

The analysis demonstrates that many of those from groups with high activation potential – such as those identified in Chapter 2 – get less unemployment insurance and for a shorter time. While the overall median daily amount of unemployment insurance is BGN 16.5, Roma receive only about BGN 12 and nearly half receive the minimum. Youth and persons with low education are also more likely to receive the minimum. Almost all people who are on the minimum amount receive it because of a “reduction” (e.g. because they voluntarily quit their job or lost if due to misconduct). About one-third of those on the minimum rate get it because it is their second spell of unemployment and about 62% of those on the minimum receive it because they voluntarily quit their job or were dismissed for misconduct (OECD calculations on NEA micro data, figures not shown in Table 4.1)

4.2.2. Social assistance (Социална помощ) and the heating allowance (целева помощ за отопление).

Bulgaria’s social assistance (Социална помощ) is a means tested, family-level benefit designed to support families suffering from long-term unemployment and is available for unlimited duration.2 In addition to the social assistance benefit, there is also a heating allowance (целева помощ за отопление). The heating allowance is a means tested family-level benefit targeted towards lower income households. The heating allowance is paid to recipients for the five months from November to March. This section details Bulgaria’s social assistance and heating allowance: including entitlement rules, amounts, and coverage.

Social assistance is available to households with very low income

Total family income is taken into account to calculate entitlements according to a means test. Social assistance tops up family income to a certain level known as the family’s Differential Minimal Income (DMI). The family’s DMI is based on a complex formula dependant on family type but the levels are low (see, for example, the policy descriptions from the OECD tax-benefit model for further details). For a family of four with two school aged children the DMI is just BGN 235.5 (EUR 120.4) well below the minimum wage of BGN 610 (EUR 311.9) per month for one full-time earner.

In addition to low income, families must not have another home or property, capital, or assets that might be a source of income. In most cases, adults are expected to be registered as unemployed, searching for a job and not have declined trainings offered by the NEA. Finally, the house lived in must have sufficiently few rooms for a family of their size.

The heating allowance is also based on a similar formula as that for social assistance. However, the income thresholds for the heating allowance are typically higher, so that there are people who may qualify for the heating allowance but not for social assistance.3 For the 2019/20 heating season the base allowance was BGN 93.18 (EUR 47.6) per month or BGN 465.9 (EUR 238.2) over the whole heating season (although this amount can change depending on the price paid for electricity). Again, this level is well below the minimum wage of BGN 610, and so the heating allowance is also targeted only towards very low income households.

Social assistance payments are too low to alleviate relative poverty

By supporting people with enough money to live on, people can focus their efforts on searching for sustainable employment. Without such support people may need to resort to wider family support or seek work in informal economy (which is especially large in Bulgaria at close to one-third of GDP – see Chapter 1). Moreover, activating inactive individuals through outreach (discussed further in Chapter 4) is easier for the Public Employment Service (PES) if jobseekers themselves have incentives to register with the unemployment agency in order to claim benefits.

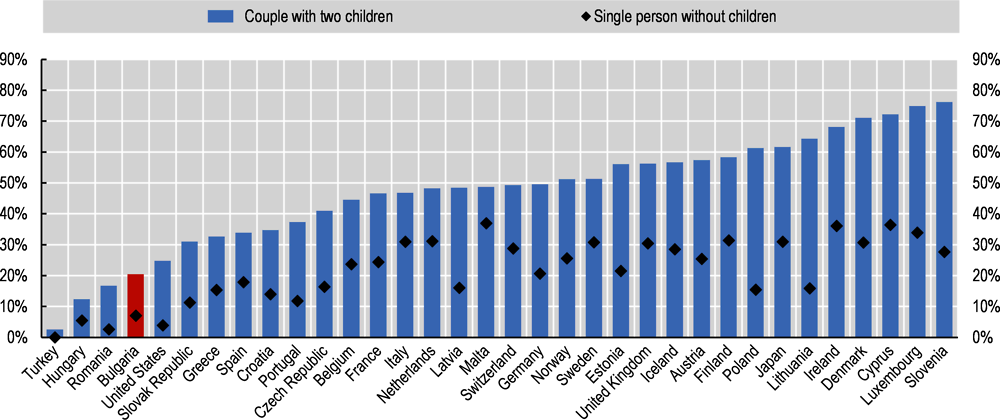

However, unlike unemployment insurance, Bulgaria’s minimum income benefits are not generous and are very low by international standards (Figure 4.3). Taking social assistance and the heating allowance together, a couple with two children would receive benefits equal to 17% of median disposable income, compared with 40% for the OECD average.

Bulgaria also requires social assistance recipients to do compulsory community service (for example environmental or sanitation work). This requires four hours of work per day for 14 days each month, though there are exemptions including for participating in an active labour market programme (ALMP). Such obligations make the already low levels of social assistance less attractive to participants and provide a disincentive to claim such benefits. In addition, it may make participating in informal work more attractive and can hinder outreach and opportunities to activate this group.

Social assistance payments begin only after six months of unemployment registration

No other country in the OECD’s tax-benefit policy tables reports requiring social assistance recipients to wait as long for benefit payments as Bulgaria (OECD, 2020[2]). Social assistance clients in Bulgaria must normally register with the unemployment agency for six months before they become eligible for social assistance. There are exceptions to this six month waiting/unemployment registration period for social assistance receipt. These exemptions, however, only cover narrow cases.4 Registration with the employment agency is a requirement for all family members (again with some exclusions e.g. children and others not expected to find work).

For social assistance recipients who are entitled to six months or more unemployment insurance there will not be a gap between the end of unemployment insurance payments and the start of social assistance. However, those ineligible for unemployment insurance must spend six months without support before they can receive social assistance. This is potentially a long time to live without income replacement, especially so given that all these households are low-income (middle income households are ineligible for social assistance). Indeed, even out of those who qualify for unemployment insurance roughly a third have less than six months of eligibility and this share rises to nearly two-thirds for Roma and youth aged 18-29 (Table 4.1).5 This implies that many people who have some unemployment insurance coverage may still face several months between unemployment insurance ending and social assistance payments beginning.

Social assistance misses many of those who live in relative poverty

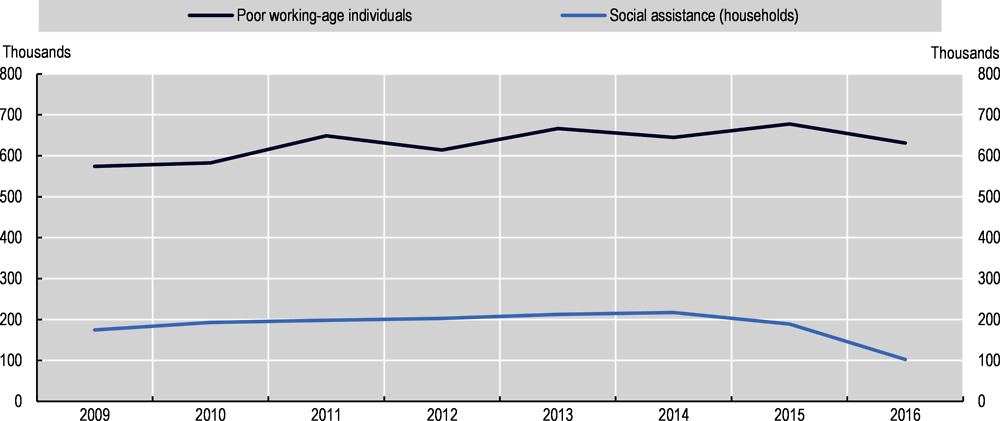

There were about 100 000 households receiving social assistance in 2016, the latest year for which data is available in the OECD Social Benefit Recipients (SOCR) database (Figure 4.4). Prior to this, in 2015 the number of households on social assistance was closer to 200 000. While these figures refer to households (rather than individuals) receiving payments, these figures are well below the number of people living in relative poverty (there are around 600 000 working age individuals living in household with less than 50% of median equalised income Figure 4.4).

Social assistance recipient numbers are most likely low in part due to the very low minimum income threshold but another reason for their low number could be a limited take-up. Earlier work showed that benefit take-up in Bulgaria is low with 40% of intended recipients not taking up benefits that they were entitled to (Tasseva, 2016[3]). In addition, 60% of people surveyed said they received benefits that they were not eligible for (with eligibility based on the author’s calculations using other survey questions).

More generous social assistance could reduce poverty risks and foster improved outreach to the inactive

While the exact numbers here should be treated with much caution – the data Tasseva (2016[3]) uses is from 2007 – it is likely that a non-trivial number of people do not claim social assistance they are entitled to. Increasing the amount social assistance pays while decreasing or removing requirements to participate in compulsory work could increase incentives to claim social assistance and thus increase incentives to register with the NEA. More generous social assistance could, hence, be part of activation strategy to reach a higher number of inactive people and activate them and integrate them into sustainable employment.

High levels of out-of-work benefits can lead to disincentives to work. Disincentives to work are discussed in more depth in the next section. However, it is important to note that there is little risk (except in the case of an extreme rise) that increasing social assistance would lead to excessively high disincentives as social assistance is currently set very low relative to other countries (Figure 4.3). Any disincentives to work can be offset by imposing time limits to more generous assistance or by increasing and the requirements for active job search by jobseekers in order for individuals to receive payments. These activation requirements are discussed further in Chapter 5, which shows that Bulgaria’s activation requirements are relatively lenient. Further, provided sufficient checks can be put in place to prevent people claiming social assistance while working in the informal economy, then a more generous level of social assistance would reduce people’s incentives to work in the informal economy.

Recent reforms in other countries have also provided examples of more generous benefits that are also tied to activation policy. For example, when recently Italy introduced a new social assistance scheme “Reddito di Inclusione” on 1 January 2018, it was combined with activation efforts including requirements for job-search, ALMP participation, and the drawing up of individual action plans. Likewise, Spain’s new Minimum Income Scheme (MIS), introduced in June 2020, also comes with activation requirements including requirements to register as job-seekers and the provision of individualised “inclusion itineraries”. In addition the MIS has a “making work pay” incentive scheme that allows recipients to temporarily receive a (reduced) amount of MIS while starting work. Details of both the Spanish and Italian changes can be found in the policy descriptions of the OECD’s tax benefit model.

4.2.3. Invalidity benefits and benefits for families

The analysis above examined the unemployment insurance and social assistance benefits which are both work tested and require job-search. This section now turns to the multitude of other benefits Bulgaria has, none of which require employment agency registration.

People with a reduced health capacity of more than 50% can claim invalidity benefits

Invalidity benefits are available in Bulgaria for people whose work capacity is assessed to be reduced by 50% or more for an extended period (European Commission, 2021[4]). These people do not need to register with the NEA in order to receive social assistance or an invalidity benefit. The main invalidity benefit is the invalidity pension for general illness (пенсия за инвалидност поради общо заболяване) which had about 385 000 recipients in 2018 (OECD Social Benefits Recipients Database). The invalidity pension is an insurance benefit and not means tested. The amount received depends on the length of social insurance contributions and average earnings prior to disability as well as the degree of work incapacity.

The lack of job search requirements potentially explains why so few people with disabilities are registered with the NEA. On the other hand, people with disabilities (50% reduced capacity) are eligible for a tax free allowance of BGN 7 920 (EUR 4 049.4) per year which increases work incentives.

In total, people with disabilities are less likely to work in Bulgaria than in many other countries (see Chapter 2). This suggests more could be done to support people with disabilities into employment where appropriate.

Benefits for families are numerous

Bulgaria has myriad benefits available to families. Indeed, in the next section, Table 4.2 shows Bulgaria spends nearly two-and-a-half times as much on families and children as it does on unemployment benefits, social assistance, and the heating allowance combined. For comparison, the comparable ratio for the EU average is closer to 1.2.6 However, Bulgaria’s high ratio of expenditures on families and children relative to expenditure alleviating unemployment and social exclusion is driven by low expenses on the later rather than above average spending on the former.

The main benefit available for families with children aged less than 18 (or less than 20 but still in school) is a means-tested family benefit (Месечни помощи за дете). Family income averaged over the last 12 months must be below BGN 410 (EUR 209.6) per month or if it is between BGN 410 and BGN 510 then families may receive 80% of the entitlement. The amounts start at BGN 40 (EUR 20.5) for the first child and go up to BGN 145 (EUR 74.1) for four children and an additional BGN 20 (EUR 10.2) for each child after that.

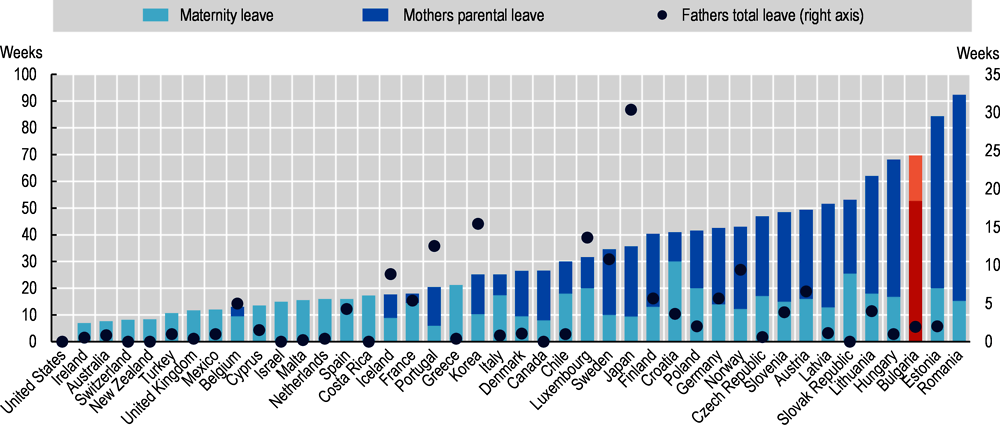

In addition to payments to families with children, Bulgaria’s paid maternity leave is notably generous. Indeed, at 58.6 weeks (52.7 full-rate equivalent weeks), it is higher than any EU or OECD country (Figure 4.5). This maternity leave is paid at 90% of prior earnings averaged over the last 24 months (European Commission, 2021[5]).7 Following maternity pay, mothers are eligible for a further 51.9 weeks of less generous paid parental leave, paid at an average rate of about 33% of prior earnings (OECD Families database date for 2018). Father’s specific leave is much less generous at 2.1 weeks though still above the average for the EU of 1.7 weeks. After the first six months of leave, the mother can return to work and transfer her leave to the father. This allows the father to take paid maternity/parental leave for a period up to 1 year and 6 months (from the age of 6 months to the age of 2 years of the child).

Chapter 2 highlighted that a high number of inactive women cite care responsibilities as a reason for inactivity. The group has great activation potential, especially as many of them no longer have young children under three years in the household. Hence, supporting women back into the labour force after maternity leave is important.

Strikingly more than 99% of those citing care barriers as their main reason for not seeking employment are women (see Chapter 2). This suggests that fathers could play a greater role in caring for children and alleviate some of the burden on mothers. To further increase the labour market participation of women and to re-balance norms around how care responsibilities are shared between fathers and mothers, some countries such as Korea, Sweden and Iceland, have increased the amount of father-specific leave (that cannot be transferred to the mother) (OECD, 2016[6]). Such policies create incentives for fathers to “use it or lose it” when it comes to taking parental leave.

There are many additional benefits and tax free allowances available (for additional details see the OECD’s Tax-Benefit model’s description of policy rules for Bulgaria (OECD, 2020[2])). Indeed, taking all benefits together (including those described above) there are at least 15 different transfers in Bulgaria, governed by different rules and managed by a number of different agencies (OECD, 2021[7]; World Bank, 2019[8]). Large numbers of these benefits often target the same or similar groups, (especially many benefits targeting families and child raising, but the social assistance and the heating allowance are also separate benefits that target similar groups). Such a large number of similarly targeted benefits increases paperwork and administrative costs associated with many separate applications for both citizens and the government. Such administrative costs are likely proportionately larger for smaller one-time benefits – where paperwork may make up a larger burden relative to the size of the transfer. Further, having many benefits for the same target group, potentially increases information costs for eligible participants. This could increase the time people spend acquainting themselves with their entitlements and in the worst cases may mean some miss out on benefits they do not know they are eligible for. Hence, simplifications to Bulgaria’s benefit system offers benefits to both the government as well as recipients.

Picking up on this aspect earlier reviews have recommended simplification of Bulgaria’s benefit system much of which is yet to occur (Dimitrov and Duell, 2014[9]; World Bank, 2019[8]; OECD, 2021[7]). However, one positive example is Bulgaria’s aggregation of benefits for families with children who have disabilities. Several benefits were replaced with one benefit launched in 2017 (World Bank, 2019[8]). This consolidation saved paperwork and benefit distribution costs to the government and recipients. Meanwhile the cost to the government, for most recipients, did not increase, as except for a small group of recipients, people did not receive larger payments than before the reform (World Bank, 2019[8]). This example could perhaps be considered in the case of other benefits and application processes for families.

The previous section reviewed the benefits available in Bulgaria: their entitlement rules, the amounts and the duration they are given for, and the coverage the benefits achieve. This section now turns to the effects of these benefits: how well the benefits alleviate poverty and whether they manage to do this without stifling incentives to work.

4.3.1. Low spending on social protection and a flat tax rate do little to reduce inequality

Spending on social protection in Bulgaria is low compared to other EU counties (Table 4.2). Bulgaria also makes much less use of means testing than the EU average. Indeed, expenditure on the means-tested social assistance and heating allowance (classified in Table 4.2 under the “social exclusion not classified elsewhere” category) represents just 0.2% of GDP. Spending on alleviating unemployment is also low making up just 0.5% of GDP which is less than half of the EU average.

Bulgaria operates a flat low income tax of 10% with no basic tax allowance (i.e. no portion of income is exempt from taxation except for some deductions related to children and disabilities). While income taxes are low, social security contributions are substantive at 13.8% for employees and 19.2% for employers. This leads to a high average tax wedge of 43% on labour income. There are maximum limits to social security contributions – employees do not pay contributions on income over 3 000 BGN (1 533.9 EUR) per month. Overall then, the system is slightly regressive. With this set up, high wage earners in Bulgaria pay a very low level of tax relative to other countries (Figure 4.6). By contrast low-income earners face rates that are much closer to the OECD average. Taxes on capital earnings, while they vary by asset class, are also much lower than on labour earnings which further favours wealthier households. A tax neutral shift that places more of the burden on high income earners and less on low income earners, for example by introducing a basic tax allowance, could improve incentives to work for low-wage workers without introducing extraordinarily high taxes on high earners (OECD, 2021[7]).

Income inequality in Bulgaria is the highest in the EU as measured by the Gini coefficient. Indeed, Bulgaria’s tax and transfer system reduces income inequality by less than any EU country (Figure 4.7). The 13% reduction in the Gini coefficient that is achieved (from pre- to post-tax-and-transfers) is driven entirely by cash-transfers (including pensions). Effectively none of the reduction is achieved by taxation, a rarity among EU and OECD countries where income inequality reductions are usually achieved by a combination of taxes and transfers (Figure 4.7). By definition, those on low incomes are taxed by more than they would be if, all else equal, a more progressive tax system was adopted.

Aside from taxation, increasing the generosity of transfers targeted towards people in poverty, such as social assistance, would also reduce income inequality. At present, the amount of social assistance families receive is well below the relative poverty lines.

4.3.2. Transitions from unemployment insurance and social assistance to work

As people move from unemployment into a job they gain employment income while losing support from benefits. Participation Tax Rates (PTRs) measure the proportion of additional income lost in taxes or through benefit reductions when people transition into full time employment. For those on social assistance PTRs are low at about 29% for a single person (calculations using the OECD tax benefit model for a transition to work from social assistance to the average wage for a single person). Unemployment insurance, on the other hand, is more generous (Figure 4.1), so when people forgo unemployment insurance to take up work, the PTRs can be higher – with around 82% of earned income lost (calculations using the OECD tax benefit model for a transition to work from unemployment insurance to the average wage for a single person).8

These disincentives are mitigated by benefit eligibility requirements that require participants to search for and not refuse jobs, with sanctions on benefit receipt for non-compliance. These eligibility requirements are discussed further in Chapter 5.

The above discussion described simple PTRs faced by a single person transitioning from social assistance or unemployment insurance to work. An alternative approach is look at every family type in Bulgaria by combining survey data with a tax model. In this way, the incentives facing every person/family can be calculated and results representative of the population reported. Jara, Gasior and Makovec (2017[10]) conduct this exercise for 2015 using the EUROMOD microsimulation model making comparisons across nine countries. Their more sophisticated analysis is consistent with the findings here. They show average PTRs in Bulgaria are modest compared to other countries when people have access to unemployment insurance and low compared to other countries once people lose access to unemployment insurance.

Bulgaria’s out-of-work benefits comprise a relatively generous unemployment insurance scheme and an ungenerous social assistance scheme, which is available only to very low income households. This means that once unemployment insurance claims are exhausted, people face the prospect of living in relative poverty on social assistance or resorting to the informal economy or wider family support (including remittances from abroad).

Bulgaria requires jobseekers to be registered with the NEA for at least six months before they can claim social assistance. This is a harsh requirement in an international context, and potentially entails a long wait for low-income families who do not have access to unemployment insurance or their unemployment insurance entitlement is less than six months. In addition, claimants of social assistance are expected to perform community service work, which makes the already low levels of social assistance even less attractive.

These features of social assistance, low payment amounts, a long six month registration requirement, and compulsory community work, contribute to low incentives to claim social assistance and potentially higher incentives to engage in the informal economy. Indeed, many people living in relative poverty do not receive social assistance. When people do not claim benefits it is harder for the PES to outreach and engage with them (see Chapter 4). Hence, an opportunity is missed for the PES to reach more jobless individuals and activate them (including through job search assistance and other employment services, as well as targeted ALMP provision, see Chapter 5).

Turning to the tax system, Bulgaria does not have a basic tax allowance, meaning that low income earners face the same flat 10% tax rate as high income earners. While such a simple system does have advantages, it also leads to high income earners paying relatively low amounts of combined tax and social security contributions compared to other countries. At the same time, low income earners face a relatively higher tax burden compared to other countries. Any reforms in this area would, however, need to undergo careful cost-benefit analysis and wait until recovery from the COVID-19 crisis is well underway (OECD, 2021[7]).

References

[9] Dimitrov, Y. and N. Duell (2014), Activating and increasing employability of specific vulnerable groups in Bulgaria: a diagnostic of institutional capacity, The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

[5] European Commission (2021), Bulgaria - Maternity and paternity, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1103&langId=en&intPageId=5037 (accessed on 2021 November 16).

[4] European Commission (2021), Bulgaria - Persons with disabilities, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1103&langId=en&intPageId=4434 (accessed on 7 September 2021).

[1] National Social Security Institute (2020), СТАТИСТИЧЕСКИ БЮЛЕТИН ЗА РЕГИСТРИРАНИТЕ БЕЗРАБОТНИ ЛИЦА С ПРАВО НА ПАРИЧНО ОБЕЗЩЕТЕНИЕ ПРЕЗ 2020 г., National Social Security Institute, https://www.nssi.bg/images/bg/about/statisticsandanalysis/statistics/bezrabotica/unempl_2020.pdf.

[7] OECD (2021), OECD Economic Surveys: Bulgaria 2021: Economic Assessment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1fe2940d-en.

[2] OECD (2020), TaxBEN Policy tables, https://taxben.oecd.org/policy-tables/TaxBEN-Policy-tables-2020.xlsx (accessed on 6 September 2021).

[6] OECD (2016), “Policy Brief: Parental leave: Where are the fathers?”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/policy-briefs/parental-leave-where-are-the-fathers.pdf.

[3] Tasseva, I. (2016), “Evaluating the performance of means-tested benefits in Bulgaria”, Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol. 44/4, pp. 919 - 935, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2016.02.003.

[8] World Bank (2019), Harmonizing services for inclusive growth: Improving access to essential services for vulnerable groups in Bulgaria.

[10] Xavier Jara, H., K. Gasior and M. Makovec (2017), “Low incentives to work at the extensive and intensive margin in selected EU countries”, EUROMOD Working Paper series, Vol. 3/17.

OECD Income Distribution Database www.oecd.org/social/income-distributiondatabase.htm

OECD Social Benefit Recipients Database www.oecd.org/els/soc/recipients-socr-by-country.htm#programme-level

OECD Social Expenditure Database, www.oecd.org/social/expenditure.htm

OECD Families Database, https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm

ESSPROS https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/social-protection/overview

Tax and Benefit Systems: OECD Indicators Database, www.oecd.org/social/benefits-and-wages.htm

Notes

← 1. Similarly, those claiming the benefit a second time within three years receive the minimum amount.

← 2. As a note on terminology some countries offer unemployment assistance (distinct from unemployment insurance and social assistance) for those who have exhausted or are not eligible for unemployment insurance. Unemployment assistance is an often generous benefit than unemployment insurance, it is usually means tested and it aims to support people’s labour market integration once they have exhausted their unemployment insurance. Bulgaria does not offer unemployment assistance but does offer social assistance. Social assistance, is similar to unemployment assistance in that it is usually means tested and designed to support those who do not have access to unemployment insurance, however social assistance differs to unemployment assistance in that its main goal is to alleviated risks of income poverty.

← 3. In principle, the reverse can also be true too: with some social assistance beneficiaries not eligible for the heating allowance. This is because social assistance is assessed on the last month of income whereas the heating allowance is assessed on the last six months of income.

← 4. For example, parents of young children (up to three years old), people with disabilities, people caring for unwell family members, and pregnant women all do not need to register as unemployed while others must register but are exempt from the six month waiting period (e.g. when children leave school, when a mothers child turns four, when people are released from prison and when people finish trainings).

← 5. Note that these calculations are approximate as the estimated duration of time receiving unemployment insurance does not always adequately account for multiple spells of unemployment insurance or for time spent participating in ALMPs (which results in them being de-registered from the unemployment register).

← 6. Social assistance and the heating allowance are included under social exclusion not elsewhere classified in Table 4.2. Hence, the comparison ratio for the EU average divides expenditure on families and children by the sum of expenses on unemployment benefits and social exclusion not elsewhere classified.

← 7. This amount must not be less than the minimum monthly full-time wage which for 2021 is BGN 650 (European Commission, 2021[5]).

← 8. Once unemployment insurance payments cease there is a sharp drop in income to the social assistance level. Unemployment insurance last at most 12 months so there is, in this respect, strong incentives to find a job within this period.