2. People

The “People” theme of the 2030 Agenda aims at eradicating poverty and hunger, in all their forms and dimensions, to ensure that all human beings can fulfil their potential, in particular in terms of health and education, and including without being penalised because of their gender. Relying on the global indicator framework, this chapter assesses whether by 2030 the OECD countries are likely to achieve the SDG targets that focus on People. It shows where OECD countries are standing both in terms of their current performance and in terms of changes over time, and what part of the People theme of the 2030 Agenda currently remains unmeasurable. It also discusses some of the main impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the People targets.

The 2030 Agenda is a call to action for all countries to act for a better and more sustainable future for all. At its core is a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals balancing the three dimensions of sustainable development: the economic, social and environmental. Since the adoption of the sustainable development agenda in 2015, its broad scope has often been characterised by five broad themes, i.e. the “5Ps” (UN, 2015[1]): People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace and Partnerships.1 The People theme aims at eradicating poverty (Goal 1) and hunger (Goal 2), in all their forms and dimensions, to ensure that all human beings can fulfil their potential, in particular in terms of health (Goal 3) and education (Goal 4), and without being penalised because of their gender (Goal 5).

Making progress towards the People SDGs also provides an opportunity to empower people and ensure inclusiveness and equality in ways that are mutually reinforcing. For example, the provision of access to quality education (Goal 4) helps improve skill acquisition and promotes economic empowerment. It also enhances people’s ability to find employment (Goal 8) whilst increasing their incomes (Goals 1 and 10) (OECD, 2019[2]).

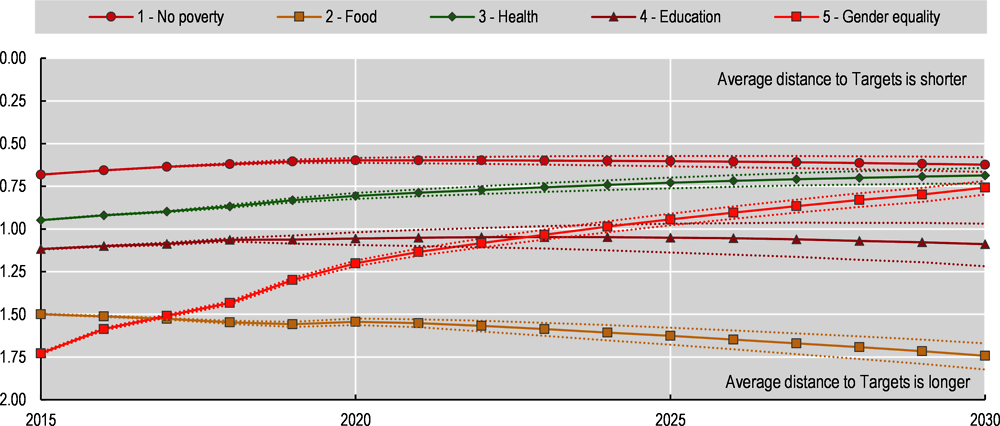

Even before the pandemic hit, OECD countries were not on track to achieve the People goals. In 2015, OECD countries were on average2 closest to reaching targets for the goals on Poverty eradication (Goal 1), followed by Health (Goal 3) and Education (Goal 4), and they were furthest from achieving the targets for Food (Goal 2) and Gender equality (Goal 5) – see Figure 2.1.

However, OECD countries have been progressing towards the SDG targets for all goals, with the exception of Food (Goal 2). The rate of progress varies among goals, with Poverty eradication (Goal 1) and Education (Goal 4) showing little improvement, while Health and most notably Gender equality (Goals 3 and 5) are showing stronger progress. Projecting trends up to 2030 suggests that all the People goals with the exception of Food (Goal 2) are likely to be closer to reaching their targets, but none of them is likely to actually reach the targets in the absence of additional measures. To overcome some of the challenges relating to composite measures, this chapter dives into the details of the underlying targets and provides an exhaustive picture of where OECD countries stand in terms of meeting the targets.

Many goals lack good quality data,3 which hampers countries’ ability to evaluate policy outcomes and determine priorities for future action. Although there is current data available on almost three-quarters of the targets pertaining to the People category, only 60% of People SDG targets can be monitored over time due to the limited availability of robust time-series data. In addition, this rate is uneven among the different goals. For instance, it is possible to track over time only two of the nine targets for Goal 5 on Gender equality.

Overall, in OECD countries, while governments have been able to buffer some of the effects induced by containment measures, the pandemic and its aftermath may have long-term consequences. Social safety nets and food assistance programmes have been able to cushion some of the short-term impacts of the crisis on poverty (see Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Goal 1 for references and details) and on hunger (Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Goal 2), but the pandemic may nevertheless have a great impact on malnutrition. In addition, given countries’ heavy reliance on support measures,4 it is much more challenging to assess the longer-term consequences of the pandemic. The tremendous disruptions faced by the systems of Health (Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Goal 3) and Education (Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Goal 4) will challenge OECD outcomes in these areas for a long time. In many countries, attempts to prevent the circulation of the virus have affected people’s ability to access health-care facilities or to attend school. As for the dimension of Gender equality, covered by Goal 5, the effects of the pandemic are more ambiguous and call for careful monitoring (Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Goal 5).

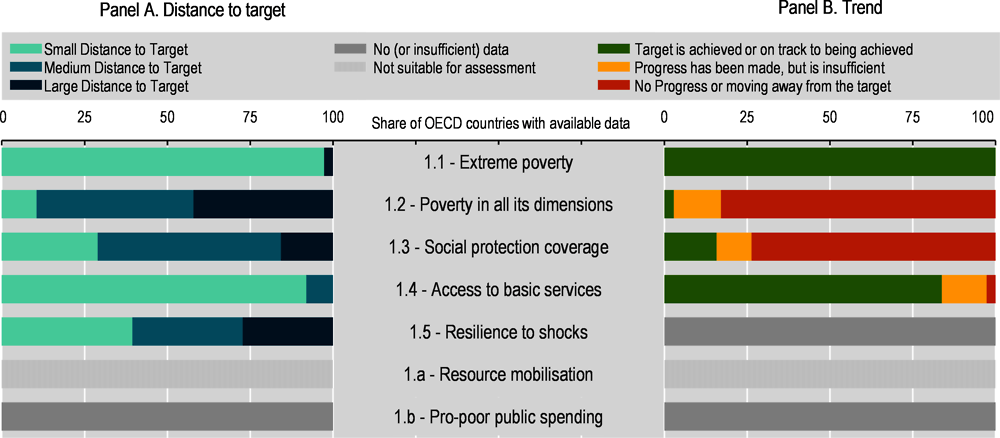

Goal 1 aims at “ending poverty in all its forms everywhere”. Overall, basic living conditions for all are (or are about to be) met in all OECD countries. However, beyond extreme poverty, Member countries show much more diverse outcomes. Relative income poverty in most OECD countries had been stagnating, while there has been limited progress on (absolute) measures of multidimensional poverty. The aggregated performance of OECD countries in terms of social protection coverage is rather anemic and may hide significant disparities – the coverage rates of cash and in-kind programmes to prevent poverty differ across countries and programme types. These overall patterns should, however, be interpreted carefully and in light of what can actually be measured.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a dramatic impact on poverty at global level. In OECD countries, however, government support measures for households seem to have buffered most of the economic impacts of COVID-19, with micro-simulation models pointing to relative stability of relative poverty rates (and even a decrease in some countries). Social protection has been key to prevent the impact of the crisis from disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations. However, heavy reliance on support measures raises the possibility that progress may be reversed, should the support measures be withdrawn.

Assessing OECD countries’ performance on Goal 1

This report uses data from the SDG Global Database together with OECD sources. Yet, the starting point always remains the global indicator framework, curated by the IAEG-SDGs. Table 2.1 shows that data allow the monitoring of five of the seven targets underpinning Goal 1, and four of them can be assessed over time. For this Goal, two data series are sourced from the OECD and do not follow the global indicator framework. Global indicator supporting Target 1.2 is the proportion of the population living below the national poverty line. To preserve cross-country comparability, this report relies on a relative income poverty rate source from the OECD Income Distribution Database. In the case of Target 1.3.1, data series from OECD databases complement the SDG Global Database. Drawing from OECD databases for this indicator allows offering longer time series and hence meeting higher statistical standards. On top of the indicators listed in Table 2.1, the database includes three additional data series under Target 1.a. Yet, those are considered to be mainly informative in the context of Goal 1 and are not assessed in this report (details and data for all indicators are available at http://www.oecd.org/wise/the-short-and-winding-road-to-2030-data-chapter-2-people.xlsx).

Virtually all OECD countries have already eradicated extreme poverty (Figure 2.3, panel A). Target 1.1 calls on countries to “eradicate extreme poverty” by 2030 – i.e. the extreme poverty rate (measured as the share of people living on less than USD 1.90 a day) is below 3%.5 In 2018, only one OECD country (Colombia) has not met this target yet, but given recent trends, all member states are expected to attain the target by 2030. This conclusion might, however, be at odds with what people with direct experience of poverty report about their lives, even in richer economies (Bray et al., 2019[5]). It might also reflect the statistical and conceptual inadequacy of this metric when applied to high-income countries.

Beyond extreme poverty, OECD countries’ performance is mixed. To overcome some of the methodological issues associated with measures of extreme poverty, Goal 1 also aims at halving “the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions”. In the global indicator framework, Target 1.2 is to be monitored with two measures: national measures of income poverty (operationalised through measures of relative income poverty in the OECD context)6 and a measure of multidimensional poverty. In 2018 (or most recent year available). Only six OECD countries are considered to be at a short distance (i.e. less than 7.5% of the population live below the relative poverty rate), while 16 of them have a relative poverty rate exceeding 12% and are thus considered to be far from the target (Figure 2.2). In particular, the United States and Costa Rica are farthest from achieving the target, with 17.8% and 20.5% respectively. On average, one in ten OECD residents is considered as relatively poor, while one in five is at the crossroads of the different dimensions of poverty.7 This means that, on average, OECD countries still have a large distance to travel to meet the target. Over time, changes in the two indicators do not show consistent trends, but no OECD country is expected to make enough progress to reach the target levels by 2030 on both indicators.8 As already underlined in the literature (Morelli, Smeeding and Thompson, 2015[6]), most OECD countries are not showing any specific improvement on relative income poverty. Data included in this report suggest that only five of them achieved some reductions over the past 15 years (Ireland, Mexico, Poland, Turkey and the United Kingdom). On the multidimensional poverty front, only a small majority of OECD countries are making some progress, but only two of them (Colombia and Iceland) at a sufficient rate to halve the level by 2030.

Even in countries with the most advanced systems of social protection, some workers and their families may not be properly covered (OECD, 2019[8]). Target 1.3 aims at "implementing nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable”. For global measurement, the IAEG-SDGs proposes to measure this through the “proportion of population covered by social protection floors/systems”. The target has been operationalised in the SDG Global Database by a series of 12 different indicators covering different aspects of social protection and for different population groups (elderly, unemployed, pregnant women, etc.); however, data are available only for nine of them. In line with previous OECD analysis of this issue, this report also includes a proxy measure of recipients of secondary out-of-work benefits (safety nets) as a percentage of the poor working-age population, sourced from the OECD. On average, over the different dimensions of social protection, around three-quarters of OECD countries can be classified as currently having a “medium” or “large” distance to the 2030 target levels for comprehensive coverage (operationalised at 97% of the respective reference population9), and more than half of them are not making any progress towards universal coverage (Figure 2.3, panel B).This implies that most OECD countries do not currently provide social protection to all vulnerable populations and that these coverage rates have been stagnating or even falling through time. However, when assessing social protection programmes that address different risks separately,10 the picture is more nuanced. While the coverage rates for family, disability and old-age benefits are, on average, quite high (relative to their population of interest), the rates are much lower when it comes to the proportion of unemployed receiving unemployment cash benefits, the proportion of the poor working-age population receiving secondary out-of-work benefits, and the proportion of the employed population covered in the event of work injury. Not all data series allow to assess changes over time; for instance, the evolution of family benefits cannot be assessed with the available data. Coverage rates for disability and old-age benefits are likely to remain above the target level,11 while the proportion of unemployed receiving unemployment cash benefits as well as the proportion of the poor working-age population receiving secondary out-of-work benefits are stagnating or even declining in most OECD countries.12 These patterns are in line with previous OECD analysis of social protection systems (OECD, 2019[9]), which have pointed to long-term declines in benefit coverage (OECD, 2018[10]).

Most OECD countries secure decent living standards for all (Figure 2.3, panel A). Target 1.4 aims at ensuring that all “have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance”. First, Target 1.4 is monitored through the proportion of population living in households with access to basic services (understood as the proportion of population with access to basic sanitation and the proportion of population with access to drinking water services). While the language of the target suggests that 100% of the population should have access to both basic sanitation and drinking water services, the threshold to consider the target as achieved were set at 97% to allow for measurement errors. On average, in 2020, almost all OECD residents already had access to basic services such as drinking water (99.6%) or sanitation (98.3%). However, as shown by Figure 2.3, panel B, projecting past trends does not suggest that a comprehensive coverage will be reached in all countries by 2030.13 In addition, as highlighted by the OECD (2017[11]), most countries already reached their economic and technical limits in terms of connection to basic services and may need to find other ways of serving small and isolated areas in order to reach complete coverage. Beyond access to basic services, the global indicator framework also includes a measure focusing on secure tenure rights to land. This is not included in this report, however, as available data do not cover enough OECD countries.

When it comes to the resilience of the vulnerable population towards shocks and disasters, the distance to target varies greatly among OECD countries (and indicators). Target 1.5 commits countries to “build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters”. Five indicators are available to assess OECD countries’ current performance on Target 1.5 on prevention and resilience towards shocks: i) the adoption and implementation of DRR strategies in line with the Sendai Framework at national and ii) at local levels; iii) the number of deaths and missing persons attributed to natural disasters as well as iv) directly affected persons and v) the direct economic loss attributed to disasters relative to GDP. Following the global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, these indicators are repeated under Targets 11.5, 11.b and 13.1. Overall, most OECD countries are considered to be at a rather short distance to the target, but available data do not allow gauging progress over time.14 On policy indicators, most OECD countries already had DRR strategies at both national and local levels in 2019. However, data from the SDG Global Database suggest that 11 OECD countries (Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, the Slovak Republic, Sweden, Turkey and Portugal) stand far from the target, with a score on the adoption and implementation of DRR strategies below 43% (100% being full adoption and implementation).15 Disasters cost lives and disrupt socio-economic activities and livelihoods, causing important economic costs each time they occur. Yet, given the large disparities existing among OECD countries, on average across three indicators on the impacts of disasters, most OECD countries (14 of 23) were at a rather short distance to the target in 2019 (or latest year); however, available data do not allow gauging progress over time. In terms of loss of life due to disasters, the OECD average is around 1 death per 100 000 inhabitants. So far, with 0.20% of total economic loss attributed to disasters in 2018, available data show a limited impact of natural disasters in most OECD countries.16

Data are not adequate to assess countries’ efforts to end poverty. Goal 1 includes two “means of implementation” targets (1.a and 1.b). Target 1.a focuses on mobilising resources to implement programmes and policies to end poverty (it is monitored through data on the share of government spending on essential services, education, health and social protection, and ODA that focuses on poverty reduction), and Target 1.b, refers to the existence of policy frameworks aiming to support investment in poverty eradication actions (it is to be monitored through a measure of pro-poor public social spending). Rather than indicators of “performance”, these indicators are useful to contextualise Goal 1 (and no data are available to monitor performance on the latter indicator). Concretely, OECD work on social data and indicators and specific publications such as (OECD, 2020[12]) provide some insights into those areas. In particular, these show that after decades of rapid growth in the 1960s and 1970s, fiscal consolidation efforts implied a lower growth of social spending after 1990 and a decline over the past decade.

Summing up

Overall, OECD countries show a mixed performance on the different targets of Goal 1 (on poverty) (Figure 2.3). Basic needs, such as eradicating extreme poverty (Target 1.1) and access to basic services (Target 1.4), are met in most OECD countries. Figure 2.3, panel A, shows that virtually all OECD countries are extremely close to eradicating extreme poverty. Similarly, on access to basic services, nine in ten OECD countries are within a short distance of meeting the target. However, more comprehensive measures, such as the relative poverty rate or multidimensional measures (Target 1.2), show more unbalanced outcomes. Nine in ten OECD countries are currently considered to be at a medium or even large distance from hitting the target on multidimensional poverty and more than three-quarters show no progress towards the target. Although social protection is an effective way to tackle poverty (OECD, 2019[13]), it is not universal even in countries with the most advanced systems. Progress towards full coverage is also insufficient, as more than half of OECD countries are expected to show no progress or move away from Target 1.3 (Figure 2.3, panel B). In addition, many OECD countries still lack the means to mitigate vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters (Target 1.5). While progress is not assessed for building resilience of the vulnerable to shocks, current distances to targets show that only two in five OECD countries can be considered close to the corresponding target.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Goal 1

At global level, the pandemic had a dramatic impact on extreme poverty, but the evidence for its impact in the OECD area is scant (Target 1.1) – see Table 2.2. Global extreme poverty is expected to have risen in 2020 for the first time in over 20 years due to COVID-19 (World Bank, 2020[14]). However, assessing the impact of the crisis on extreme poverty across OECD countries is more challenging, because of a much smaller number of studies.

In most OECD countries, government support measures to households have helped offset some impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on relative poverty (Target 1.2). While most macro-economic measures of economic performance such as GDP or employment dramatically declined during the crisis, average household disposable income (as measured by national accounts) rose by 5.3% in the second quarter of 2020, thanks to government cash transfers (OECD, 2020[15]), though it then gradually fell until the fourth quarter of 2020 (OECD, 2021[16]). While data on average household income do not allow meaningful inferences on the impact of the crisis on income poverty, recent research using micro-simulation models tends to confirm the effectiveness of social protection systems in cushioning shocks on household incomes17 (Figari and Fiorio, 2020[17]; Brewer and Tasseva, 2020[18]; Almeida et al., 2020[19]; Lustig et al., 2020[20]; Li et al., 2020[21]; Han, Meyer and Sullivan, 2020[22]).18 Provisional estimates prepared by the OECD19 show that earning losses were heavier for the most vulnerable. Those losses were alleviated to a large extent by taxes and social transfers, and in particular by the extraordinary measures put in place by national governments. Despite that, some working-age people, particularly young workers, have experienced increases in poverty rates in some countries (Eurostat, 2021[23]).

As noted above, social protection (Target 1.3) has been key to limiting the economic impact of a crisis on vulnerable populations, as it plays a critical role in softening the drop in income as a result of the crisis. However, there is a risk that many vulnerable households will nevertheless experience a drop in disposable income, and a greater risk of poverty, as the crisis lasts longer. Entitlements to job retention schemes and unemployment benefits are often time-limited, and governments will eventually have to phase out some of the temporary emergency income support provided outside of standard social protection systems. As shown by OECD (2021[16]), the decline in real household disposable income per capita between the second and fourth quarters of 2020 reflects the decrease in government transfers to households. As stressed in OECD (2021[24]), while support remains key for sectors still heavily affected by social distancing restrictions, for others where economic activities have resumed the design of these schemes is to be progressively adjusted. In addition, supporting all vulnerable households and closing social protection gaps will remain key priorities beyond the crisis (OECD, 2020[25]), in particular for the large number of workers in non-standard jobs who are being left behind even in countries with the most advanced social protection. Overall, though, as the COVID-19 crisis and government responses affected both the number of vulnerable households as well as the number of people entitled to social protection, the actual impact on the coverage rate (Target 1.3) is still unknown (Table 2.2).

Target 1.5 on population’s resilience to economic, social and environmental shocks includes measures of both policy stance and the impact of these disasters. The excess mortality induced by the COVID-19 pandemic will dramatically impact the second part of the target. In particular, this target includes an indicator on risk reduction (a score of adoption and implementation of “national disaster risk reduction strategies in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030”), which covers risks of epidemics and pandemics.20

As underlined by the OECD (2020[26]), the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to lead to a marked increase in social spending (Targets 1.a and 1.b). Demands on health-care systems have increased, and a wide array of social support measures were put in place or expanded to help people cope with the economic effects of the pandemic (OECD, 2021[27]). Yet, given the difficulty to gauge just how informative this indicator actually is (an increase in public spending cannot be classified as progress), Table 2.2 has summarised the impact as mixed.

Goal 2 aims at achieving food security for all and ending malnutrition, but also at promoting agricultural practices that are sustainable for the environment and that preserve the living conditions of food producers. On the consumption side, severe hunger has been eradicated in the vast majority of OECD countries. Nonetheless, in many countries malnutrition and food insecurity remain an issue, and the situation is unlikely to improve by 2030. On the production side, despite progress in some dimensions, the environmental sustainability performance of agriculture is still insufficient. Making better policies for food systems will, however, require overcoming large evidence gaps on the extent, characteristics and drivers of policy issues, but also on the effectiveness of policy instruments and on some of the policy implications (OECD, 2021[28]).21

On the consumption side, the fall in household income induced by the COVID-19 crisis may have led to a dramatic rise in food insecurity, especially in poorer countries. In OECD countries, however, safety nets and food assistance programmes should have softened the main effects of the crisis on hunger. Nonetheless, income losses, unemployment, stress and more sedentary behaviours induced by the pandemic raise concerns about an increase of malnutrition. On the production side, even though food supply chains have proved remarkably resilient in the face of the pandemic, the crisis is likely to have a long-term impact on the agricultural sector, most notably on farmers’ livelihoods and greenhouse gas emissions (OECD, 2020[29]).

Assessing OECD countries’ performance on Goal 2

This report uses data from the SDG Global Database together with OECD sources. Yet, the starting point always remains the global indicator framework, curated by the IAEG-SDGs. Table 2.3 shows that data allow the monitoring of five out of the eight targets underpinning Goal 2. For this goal, two indicators sourced from the OECD complement the SDG Global Database. Relying on OECD data sources allows monitoring Indicator 2.4.1 (which is to be measured by the proportion of agricultural area under productive and sustainable agriculture), for which no data series are available in the SDG Global Database. In addition, using OECD data sources on Target 2.2 on malnutrition provides wider country coverage and allows coverage of an area that is critical for OECD countries, beyond those covered by the global indicator framework. On top of the indicators listed in Table 2.3, the database includes six extra data series to monitor Targets 2.5 and 2.a, but those are considered to be mainly informative in the context of Goal 2 (details and data for all indicators are available at http://www.oecd.org/wise/the-short-and-winding-road-to-2030-data-chapter-2-people.xlsx).

Severe hunger has been eradicated in the vast majority of OECD countries, but food insecurity remains an issue for many of them. Target 2.1 commits countries to “end hunger and ensure access …to safe, nutritious and sufficient food”. For global measurement, the IAEG-SDGs proposes to measure this through the prevalence of undernourishment (2.1.1) and the prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity (2.1.2). Overall, around three in four OECD country are close to having eradicated Hunger (Figure 2.6, panel A). In 2019, the levels of undernourishment (i.e. the proportion of the population whose habitual food consumption is insufficient to provide the dietary energy levels that are required to maintain a normal active and healthy life) and severe food insecurity (i.e. the proportion of individuals who have experienced food insecurity, as measured through the “Food Insecurity Experience Scale”) are below 3% in almost all OECD countries, and below this level measures are likely to reflect measurement errors. The only notable exceptions are the Slovak Republic and Colombia, where 4% to 9% of the population still miss the dietary energy levels required to maintain a normal active and healthy life. In addition, in Mexico, the distance to target is large for both the prevalence of undernourishment (7%) and the prevalence of severe food insecurity (6%). Beyond extreme hunger though, moderate food insecurity remains an issue for a significant share of OECD countries. Only 12 OECD countries are at a short distance from eradicating food insecurity (i.e. less than 5.2% of the population is food insecure); with more than 10% of their population suffering from severe to moderate food insecurity, nine Member countries are considered to remain far from the target. When looking at recent developments in the prevalence of undernourishment over time, the picture is positive for all countries but four (Mexico, the Slovak Republic, Chile and Colombia) (Figure 2.6, panel B). However, considering the lack of progress on moderate food security, more than three in four OECD countries may not achieve the overall target by 2030.

No OECD country is considered as being close to ending malnutrition. While Target 2.2 refers to “ending all forms of malnutrition” and “addressing the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women and older persons”, global indicators focus only on children under the age of 5 and women of reproductive age. Available data do not cover enough OECD countries to measure the prevalence of stunting among children under age 5 (Indicator 2.2.1), and relying on the SDG Global Database would restrict the assessment to the prevalence of anaemia among women of reproductive age (2.2.3). Anaemia is highly prevalent globally, disproportionately affecting children and women of reproductive age. It negatively affects cognitive and motor development and work capacity, and among pregnant women iron deficiency anaemia is associated with adverse reproductive outcomes, including preterm delivery, low-birth-weight infants and decreased iron stores for the baby, which may lead to impaired development. In OECD countries, on average 14% of women of reproductive age suffered from anaemia in 2019. While the target had been set at 3% (below this level measures are likely to reflect measurement errors), no OECD country is considered to be at a short distance to the target, and only two (Australia and Chile) are deemed to be at a medium distance. With more than one in five women suffering from anaemia, distances are particularly large in the Czech Republic, Colombia, Latvia, Estonia, Slovenia and the Slovak Republic. While blood haemoglobin concentrations can be affected by many exogenous factors, including altitude, pregnancy, age and sex, unhealthy behaviour (such as smoking or a diet lacking in certain vitamins and minerals) also plays a significant role. Over the last two decades, the prevalence of anaemia has been increasing in all but seven OECD countries (mostly from Latin America and Eastern Asia), but even in these the pace would not be sufficient to lead to significant reductions.

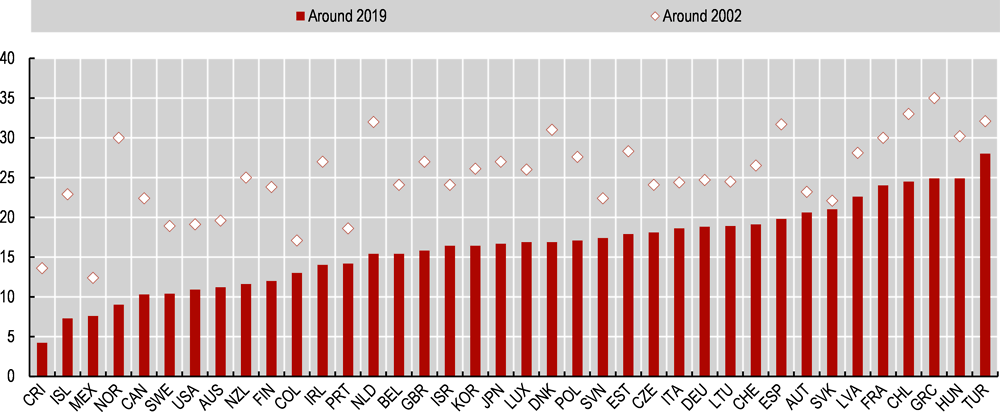

In addition, other types of malnutrition, beyond those covered by the global indicator framework, prevail in OECD countries. In particular, obesity, which was already high in the vast majority of OECD countries, had been increasing in virtually all of them over the past two decades (Figure 2.4) not expected to be eliminated in any of them. With less than 6% of the population classified as obese, Japan and Korea are the only OECD countries that can be considered as close to the aspirational target of eliminating obesity, which is operationalised at 3% of the resident population. With more than 15% of their resident population being obese, distances to target are considered to be large for 31 OECD countries. For six of them, including Australia, Chile, Hungary, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States, the prevalence of obesity even exceeds 30% of adults. Being overweight, including obese, is a major risk factor for various non-communicable diseases (NCD) such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and certain cancers (see Target 3.4 for further details).

Beyond food consumption, hunger and malnutrition, Goal 2 also includes targets pertaining to the inclusiveness and the environmental impacts of the food production sector. Target 2.3 for instance, aims at fostering agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers. While data exist for some OECD countries, thus far, they cover only European countries and Canada and are thus not available for enough OECD countries to be included in this report.

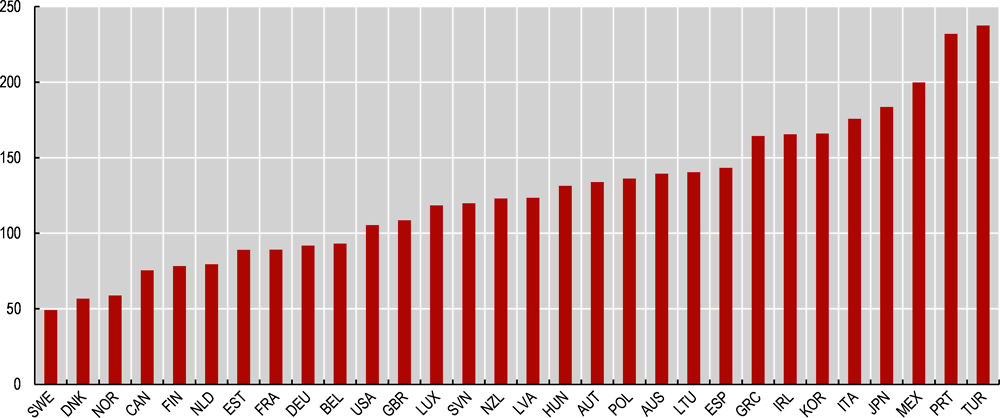

The agricultural sector’s pressure on the environment is high in several OECD countries, and, despite some progress, concerns remain. Target 2.4 aims at “ensuring sustainable food production systems and implementing resilient agricultural practices”. At global level, Target 2.4 is measured by the share of agricultural area under productive and sustainable use, but there is no agreement as to how to measure it among OECD countries (OECD, 2019[31]). To overcome this problem, and in line with previous OECD analysis on this issue, this report measures the environmental pressure of the agricultural sector through data on the nitrogen surplus associated to agricultural production.22 Nitrogen surpluses contribute to water and air pollution, while, conversely, agricultural areas with sustained nutrient deficits may suffer reductions in soil fertility (zero surplus can thus be considered as an aspirational target for 2030). Based on data for the latest year available (around 2018), only six OECD countries (Iceland, Colombia, Australia, Estonia, the Slovak Republic and Canada) can be considered as being “close to the 2030 target” (i.e. less than 25 kg of nitrogen per hectare of agricultural land), while nine OECD countries (Denmark, the United Kingdom, Norway, the Czech Republic, Luxembourg, Belgium, Japan, the Netherlands and Korea) report more than 70kg/ha and are thus considered as having a large distance to the target (Figure 2.5). Beyond the static snapshot, progress towards reduced nitrogen balances is mixed. While declining on average across OECD countries, balances have been stagnating or even increasing in more than half of them, including in some countries with already high levels of nitrogen surplus. Figure 2.6, panel B, shows that despite some progress in a few countries, none of them is expected to achieve a nitrogen balance by 2030. In addition, recent analysis has shown that the decline in nitrogen surpluses has slowed almost everywhere, raising concerns about the ability of OECD countries to attain their target by 2030 (OECD, 2019[32]).

Despite the fact that Target 2.5 is one of the very few with an earlier (i.e. 2020) deadline, a very high share of local livestock breeds are at risk of extinction, with very few countries making progress. Target 2.5 commits countries to “maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species” and “promote access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge”. One of the measures to monitor Target 2.5 is the proportion of local breeds classified as being at risk of extinction (Indicator 2.5.2). While the natural target is zero, the target level had been set at 3% to allow for measurement errors. Even though the deadline to meet the target has passed, no OECD country had been able to make enough progress. On average, across OECD countries, in 2021, 80% of local breeds are still classified by the FAO as being “at risk” (as a share of local breeds with known level of extinction risk), and only one country (Mexico) can be considered as being close to the target (i.e. less than 15% of local breeds at risk of extinction). Yet, caution should be taken when interpreting the results, as for the majority of local breeds around the world, the risk status remains unknown due to a lack of data. For instance, even though Mexico is considered to be the only country to achieve the target level based on available data (Figure 2.6, panel B), the actual status of only 6% of local breeds was known in Mexico in 2021. While the deadline has already passed, overall trends are not encouraging, and, with the exception of three countries (Austria, Colombia and Germany), no OECD country is expected to make any further progress towards the target in the absence of specific policies (Figure 2.6, panel B). Beyond reducing the risk of extinction, this target also aims at developing facilities for the conservation of plant and animal genetic resources for food and agriculture. Available data are, however, expressed as the total number of secured resources and do not allow any comparative assessment.

The distance to target is not assessed for two of the three “means of implementation” targets under this goal (2.a and 2.b). Target 2.a focuses on investment in rural infrastructure and agricultural research and is monitored through data on government spending and ODA going to the agriculture sector. While the type and impact of government spending in agriculture and food may be gauged, the amount of spending is a contextual indicator, rather than an indicator of performance. Therefore, it is not used to measure distance to target. In addition, as most recent agricultural policy developments have been dominated by responses to the impact of the COVID pandemic, the trend of this indicator is further discussed in the section below (Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Goal 2). Similarly, ODA flows are not used to monitor progress. ODA flows are conditioned by both the donor’s and recipient’s context and cannot be benchmarked properly. Yet, OECD data show that, driven by a shift away from bilateral aid that finances infrastructure and production, with aid focusing more on social sectors, aid to agriculture in developing countries has fallen from nearly 25% of total ODA in the mid-1980s to only 5% in 2019 (OECD, 2021[34]). Whilst the share of aid to agriculture has hovered around 5%, in volume terms it more than doubled since 2002. Part of this trend is due to the increase in total ODA since 2002, as well as to increased food security concerns and to a renewed interest in agricultural technology for the poor.

The indicator supporting the assessment of Target 2.b on trade restrictions and distortions in agricultural markets (monitored through agricultural export subsidies) is also considered as providing contextual information. Agricultural export subsidies are reported in millions of USD and do not take into account the different sizes of agricultural economies. Using a wide range of measures of support to agriculture, OECD work on agricultural policies shows that about two-thirds of support to farmers is provided through measures that strongly distort farm business decisions – thereby distorting global agricultural production and trade (OECD, 2020[35]; OECD, 2021[36]).

Virtually all OECD countries are (or will be) able to limit food price anomalies. Target 2.c focuses on ensuring the functioning of food commodity markets and facilitating timely access to market information. It is monitored through an indicator of food price anomalies (IFPA)23 that aims at identifying market prices that are abnormally high.24 In 2019, as shown in Figure 2.6, panel A, no OECD country reported a large distance on this indicator (with scores ranging between 0.90 and 1.20, only three OECD countries including Australia, the Netherlands and Poland are considered to be at a medium distance). Past trends suggest all countries are likely to remain in a “normal range” by 2030 (Figure 2.6, panel B). This suggests that in OECD countries, existing institutions and mechanisms allowed preventing high volatility in food prices in the long-run.

Summing up

Overall, while most OECD countries have alleviated severe hunger and limited extreme food price volatility, few of them will be able to meet most Goal 2 targets on eradicating hunger and malnutrition. As stressed by the OECD, food systems need to meet the triple challenge of ensuring food security and nutrition, providing livelihoods for farmers and others in the food chain, and improving the environmental sustainability of the sector (OECD, 2021[28]). Food security remains an issue, particularly for the most vulnerable (Placzek, 2021[37]), but a vast majority of OECD residents have access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food (Target 2.1). Yet, beyond hunger, more and more people are experiencing malnutrition and obesity (Target 2.2). On the environmental sustainability front, despite progress in some dimensions, the performance of agriculture is still unsatisfactory. Most OECD countries lack the mechanisms to maintain diversity of seeds and livestock (Target 2.5), and despite nearly half of OECD countries showing some progress, none is expected to relieve the environmental pressure of the agricultural sector by 2030 (Target 2.4). While the impact of climate change and the rise in extreme weather conditions may impact food security and price stability, for now no OECD country is experiencing high food price volatility. Target 2.c on the functioning of food commodity markets is actually the only target that virtually all OECD countries are likely to reach by 2030 (if previous trends materialise).

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Goal 2

The biggest risk for food security in OECD countries (Target 2.1) is not limited food availability but rather consumers’ lack of access to food due to income limitations. Despite many factors adversely affecting agricultural and food markets during the pandemic, including a lack of seasonal labour and disruption of air freight, shortfalls in the availability of food have so far been limited. Food supply chains have demonstrated resilience in the face of the stress induced by the pandemic, and a food-price crisis similar to the one experienced in 2007-08 has been avoided (OECD, 2020[38]). However, a persistent gulf between supply and demand for some goods, together with rising food costs, has led to higher and more enduring price increases than expected (OECD, 2021[39]). In addition, the rise in unemployment triggered by containment measures has resulted in unprecedented numbers of people relying on social protection programmes or food handouts delivered by charities and anti-poverty associations. As noted in the previous section, social safety nets and food assistance programmes have helped to mitigate the main effects of the crisis on food insecurity in most OECD countries. Yet, even in countries with the most advanced social protection, some, such as workers with non-standard jobs and their families, young people not in education, employment or training, students, etc., may have missed out. In addition, while food assistance usually provides staple food, low-income people may lack proteins and vitamins and suffer from malnutrition (Placzek, 2021[37]). As food insecurity is associated with increased risk for chronic diseases, changes in the depth and breadth of food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic could have serious and long-lasting health consequence (Leddy et al., 2020[40]).

In addition, the pandemic may have increased the risk of obesity (Target 2.2) – see Table 2.4. The COVID-19 crisis and lockdowns have led to dramatic changes in people’s behaviours, prompting people to cut back on physical activity and to increase sedentary behaviours (Stockwell et al., 2021[41]). In parallel, as research (Torres and Nowson, 2007[42]; Adam and Epel, 2007[43]) shows that higher stress and anxiety are likely to influence eating behaviour (leading to greater consumption of foods that are energy and nutrient dense, i.e. high in sugar and fat). While no definitive evidence exists on the impact on the risk of obesity, the risk is expected to have significantly increased following the pandemic (Mattioli et al., 2020[44]).

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to significantly affect the agricultural sector over the next decade. Beyond food consumption, Goal 2 also aims at ensuring the livelihoods of people working in food production (Target 2.3) and preserving the sustainability of agriculture. In particular, recent OECD analysis (OECD, 2020[29]) highlights how falling incomes at global level would have had a cascade effect on many different aspects of the food sector in the absence of government intervention. Yet, most recent analysis suggests that average farm incomes rose in 2020 for a majority of OECD countries (OECD, 2021[45]).

Support to agriculture (Target 2.a) may be distortive (Target 2.b), inefficient, inequitable and harmful (Target 2.4). Substantial resources – USD 75 billion – were earmarked for COVID-19 sectoral support in OECD countries – but actual disbursements have so far been much lower, partly reflecting the overall resilience of agriculture to the COVID-19 shock. Yet, most of this support was provided through potentially distorting instruments (market price support and payments linked to output or the unconstrained use of inputs) that are inefficient at transferring income to farmers (a large share of the benefits is capitalised into land values or leak in the form of higher prices for inputs). They also tend to be inequitable, to the extent that support is linked directly to production, and not targeted to producers with low incomes. Finally, through direct incentives to increase production, these instruments contribute to increasing resource pressures, including through impacts on water quality, and can raise GHG emissions. Given also a lack of complementary environmental policies, fewer countries have managed to combine productivity growth with lower resource pressures and reduced emissions (OECD, 2021[45]).

While the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic are strongly visible in international trade, food prices remained robust (Target 2.c). Many governments moved swiftly to keep agricultural supply chains functioning, including by designating agriculture and food as an essential sector. As a result, policies were generally successful in maintaining the overall functioning of food supply chains. After dropping by 7% in the second quarter of 2020, average international food prices increased towards the end of the year, and annual averages ended 3% higher than in 2019, with contrasting movements between crop and livestock markets (OECD, 2021[45]). Yet, more recently, global food prices have risen to their highest level in a decade, amidst strong demand and weather-related disruptions to production in key food-exporting economies (OECD, 2021[46]). In October 2021, annual food price inflation rose to 4.5%, from 1.5% in May 2021. While inflation is expected to fade through 2022-23, it could continue to surprise on the upside (OECD, 2021[39]).

Since the onset of the pandemic, more than 2 million people have died from COVID-19 in OECD countries. This has had a dramatic impact on Goal 3, which aims at ensuring “healthy lives and well-being for all and at all ages”. While combatting non-communicable disease had been the most salient health-care challenge for OECD countries for long, the pandemic is bringing back the combat against infectious diseases as a major challenge for OECD countries. In this context, more than ever, Goal 3 is a central piece in reaching the targets of the 2030 Agenda.

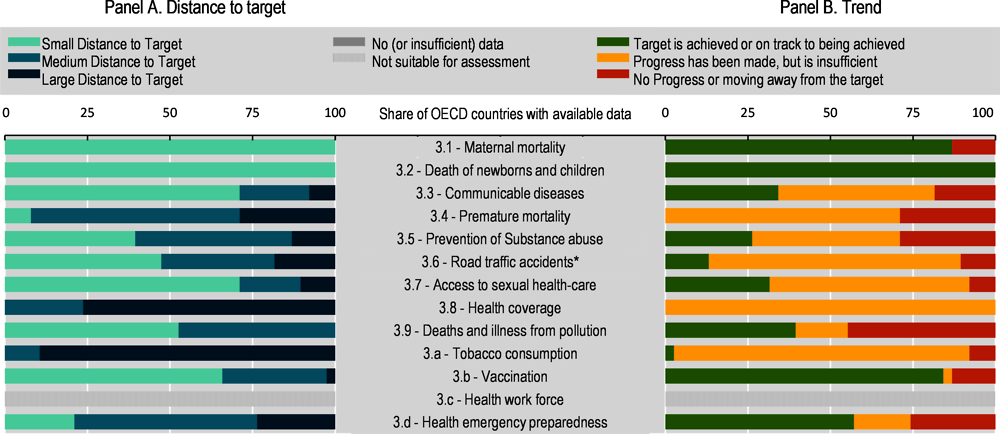

Before the pandemic hit, OECD countries were progressing on the vast majority of targets relating to Goal 3. However, the pace of progress would not have allowed achieving the targets underpinning Goal 3 by 2030. While nearly all OECD countries greatly reduced maternal and infant mortality, significant challenges remain in other fields. Among those, combatting non-communicable diseases was probably the major challenge for OECD countries before the pandemic hit. Fuelled by unhealthy lifestyles, including smoking, drinking and obesity, but also by environmental factors, like air pollution, and demographic changes, non-communicable diseases were the leading cause of death in OECD countries. While the toll imposed by communicable diseases had significantly declined, a range of factors – lower confidence in the safety and efficacy of vaccines, the diffusion of antibiotic-resistant infections and new viral outbreaks such as COVID-19 – are about to undo part of the progress achieved. To overcome those persistent changes, strong and inclusive health-care systems are essential. While most OECD countries have achieved universal coverage for a core set of health services, the range of services covered and the degree of coverage vary substantially across countries. Effective access to different types of care can also be limited because of shortages of health workers, long waiting times or long travel distances to the closest health-care facility.

COVID-19 is directly affecting the health of millions of people, but the pandemic also has an indirect effect on many other dimensions of health. The pandemic revealed and amplified vulnerabilities in health-care systems. In many countries, attempts to prevent the circulation of the virus largely disrupted normal health-care services. By limiting people’s ability to go to health-care facilities to seek services such as check-ups, vaccinations and even urgent medical care, the pandemic is affecting the prevention, early diagnosis and treatment of many diseases. Conversely, in the very short term, some of the protective measures put in place to limit the pandemic have had a positive impact. For instance, the substantial drops in mobility resulted in a large decrease in road accidents and in temporary reductions of air pollution.

Assessing OECD countries’ performance on Goal 3

This report uses data from the SDG Global Database together with OECD sources. Yet, the starting point always remains the global indicator framework, curated by the IAEG-SDGs. Table 2.5 shows that data allows the monitoring of 12 of the 13 targets underpinning Goal 3 (all of which can be monitored over time). For this goal, 12 indicators sourced from the OECD complement the SDG Global Database. In most cases, they align with the global indicator framework. In some cases, drawing from OECD databases also allows for a longer time span (3.3.4 and 3.7.2), being timelier (3.a.1), or mirroring specific conditions in OECD countries. For instance, using OECD data to assess mortality indicators (3.1.1, 3.2.1, 3.2.2, 3.4.2, 3.6.1 and 3.9.3) allows greater accuracy, as mortality rates are age-standardised based on the structure of the OECD population. Therefore, drawing from OECD databases prevents country comparisons from being disproportionately influenced by country differences in the population’s age structure. Finally, while the SDG Global Database has available data series on new HIV infections (3.3.1), since it does not cover enough OECD countries, an indicator of new incidences of AIDS is included from OECD sources. On top of the indicators listed in the table, the database includes eight extra data series (under Targets 3.b and 3.c), but these are considered to be contextual indicators rather than measures of performance and cannot be included in the assessment of Goal 3 (details and data for all indicators are available at http://www.oecd.org/wise/the-short-and-winding-road-to-2030-data-chapter-2-people.xlsx).

Figure 2.9, panel A, shows that all OECD countries already have greatly reduced both maternal mortality (Target 3.1) and deaths of newborns and children (Target 3.2). Target 3.1 calls on countries to “reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100 000 live births”, which is supported by two distinct indicators: the maternal mortality ratio and the proportion of births attended by skilled heath personnel. In 2018 (or latest year available), all OECD countries already exceeded the target level for both indicators.25 However, Figure 2.9, panel B, also shows that, in the absence of additional measures, around 15% of OECD countries may fail to reach the target for maternal mortality (Target 3.1). While no OECD country is expected to fail in achieving the target on maternal mortality, past trends suggest that a few may not be able to reach the target on the proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel (including France, Denmark, Iceland, the Slovak Republic and New Zealand).

Through Target 3.2, the 2030 Agenda aims at “ending preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age neonatal”. It even proposes numerical targets to be reached by 2030 for both mortality rates: below 12 per 1 000 live births for neonatal mortality and below 25 per 1 000 live births for under-five mortality. All OECD countries were already well below those rates in 2019, and none of them is expected to exceed those rates in 2030. This report also includes measures of infant mortality (i.e. below one year of age) for which the target had been set at 15 per 1 000 live births to be consistent with the targets for neonatal and under-five mortality. Similarly, all OECD countries are already below target level for the infant mortality rate (or will be by 2030).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, most OECD countries had achieved strong progress in reducing the incidence of communicable diseases, yet these diseases remain a threat to the health of OECD citizens. Target 3.3. refers to “ending the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases” and “combatting hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases”, which is to be monitored by six measures, each corresponding to a different disease (target levels are set at 3 per 1 000 000 population).

On HIV/AIDS, relative to the OECD average in 2018, distance to the target on the number of new AIDS26 cases are short in a vast majority of countries. Distances are longer in Colombia, Costa Rica and Mexico and to a lesser extent in Chile, the United States, Latvia and Estonia. As progress in HIV/AIDS therapy has allowed decoupling HIV infection from its progression to AIDS (Gaind, 2016[47]), a majority of OECD countries (20 of 38) show declining rates of new AIDS infections. However, this should not hide the lack of progress on the rates of new HIV infections in many OECD countries. In addition, only 11 OECD countries are expected to reach the target level for AIDS incidences by 2030.

On tuberculosis, in 2018, distances to target are short for both new reported cases and deaths for more than half of OECD countries, but they are long in Colombia, Korea, Lithuania and Latvia. Death rates are stable or declining in all OECD countries, and available data does not suggest any progress on the front of new cases in seven OECD countries. While some countries already have rather low rates (Australia, Iceland, Norway and Sweden), other countries show high rates and no progress (Colombia, Korea and Mexico).

On hepatitis B, in 2019, distances are short in all OECD countries besides Chile, Belgium and Canada (and to a lesser extent in Costa Rica and Colombia) when the assessment is based on incidence. However, using surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence among children under age five suggests that in 2015 fewer than half of OECD countries can be considered to be at a short distance to the target (14 of 38). While trends cannot be assessed for HBsAg prevalence, hepatitis B incidence is likely to remain at a low rate or even be decreasing in most OECD countries. Yet, for eight countries, incidences had been on an upward trend over the past few years (Canada, Belgium, Chile, Costa Rica and Colombia but also Portugal, Korea and Japan, where incidences are rather low).

Target 3.3 also refers to tropical diseases and malaria. Yet, tropical diseases are negligible in all OECD countries other than Colombia and Mexico, and no data are available on malaria for any OECD country.

Overall, while seven in ten OECD countries are considered to be at a short distance from Target 3.3, in the absence of further measures, only four in ten countries will be able to reach the target by 2030 (Figure 2.9, panel B).

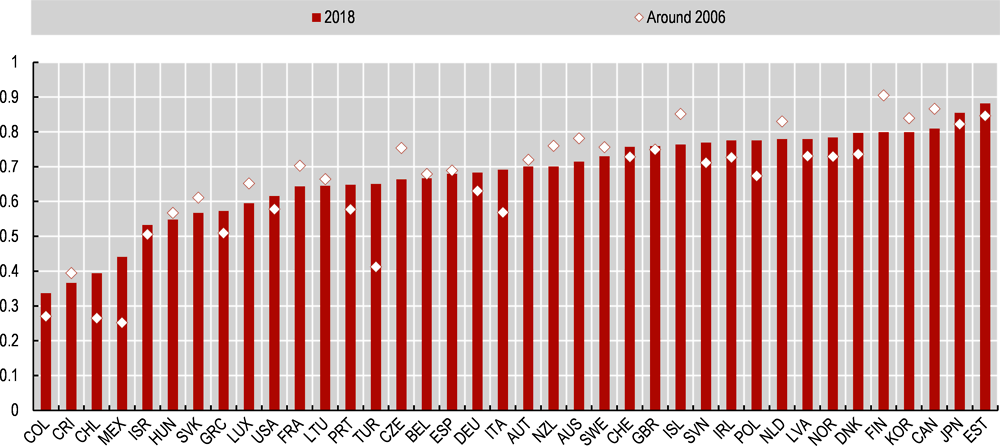

Despite current downward trends in mortality rates attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and suicide rates in most OECD countries, countries are not on track to meet target levels by 2030. Target 3.4 calls countries to “reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being”. Accordingly, the global indicator framework encompasses both deaths from non-communicable diseases as well as deaths from suicide. Regarding the former, as a result of both unhealthy living conditions (see Targets 2.2, 3.5 and 3.a) and population ageing, non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory disease, had been by far the leading cause of death in most OECD countries (OECD, 2019[48]). Figure 2.7 shows that, in 2019, most OECD countries are considered to be at a medium or long distance from the 2030 target (i.e. the probability of dying between the ages of 30 and 70 from cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes or chronic respiratory disease is higher than 10%).27 At the same time, over the last two decades, all OECD countries have experienced declines in the probability of dying from such diseases. However, in the absence of further measures, the current pace of progress would be insufficient to reach the 2030 target for 28 of the 38 OECD countries.

The second segment of Target 3.4 covers quite a different aspect of premature mortality: death from suicide.28 On average across OECD countries in 2018, 11 people per 100 000 die each year from suicide, but large cross-country disparities exist. Overall, despite minor differences between data from the OECD and from the SDG Global Database, Turkey, Greece and Mexico and to a lesser extent Israel and Italy can be considered to be close to target (i.e. suicide rate is below 6 in 100 000 people).29 Conversely, death rates from suicide are twice as high in the vast majority of OECD countries. This conclusion is further strengthened when considering that death registries are likely to under-represent the phenomena due to different reporting practices and stigma (OECD, 2020[49]).

Alcohol consumption has been declining in a (small) majority of OECD countries, but consumption patterns remain high in many of them. Target 3.5 is about substance abuse, a leading driver of higher mortality. For global measurement, the IAEG-SDGs proposes monitoring the coverage of treatment interventions for substance abuse and alcohol per capita consumption (aged 15 years or older). When measured through sales data, alcohol consumption in individuals aged 15 or over was estimated at around 10 litres of pure alcohol per person in 2019 – this is equivalent to two bottles of wine, or nearly 4 litres of beer, per week per inhabitant in OECD countries. Yet, this average masks significant variations both across countries and, within the same country, across different population groups (OECD, 2021[50]).

Alcohol intake is a major risk factor for many non-communicable diseases (Target 3.4) and significantly contributes to road traffic accidents (Target 3.6), violence and homicide (Target 16.1), suicide and mental health disorders (Target 3.4) – see (OECD, 2021[50]). While there is no international benchmark to gauge alcohol consumption, in 2013, countries worldwide have agreed nine voluntary global NCD targets, among which one aims to achieve at least a 10% reduction in the harmful use of alcohol by 2025 against a baseline in 2010. Applying this 10% reduction to alcohol consumption set the target for 2030 at 8.5 litres of pure alcohol per person and per year. Using this benchmark, 23 OECD countries are considered close to target (i.e. consumption is lower than 10 L per capita), while Latvia is the only country considered to be far from the target, with an average annual alcohol consumption of 12.9 litres of pure alcohol per person in 2019. Over the past two decades, average alcohol consumption has been declining in 23 OECD countries, but only 10 of them are progressing fast enough to reach the target by 2030.

Note that data on alcohol consumption per capita help to assess long-term trends but do not identify the risk from harmful drinking patterns, which account for an important share of the burden of disease (OECD, 2019[48]). Alcohol use disorders are of particular concern: more than one in ten adults suffer from disorders attributable to the consumption of alcohol in 12 OECD countries, particularly in Latvia (16%) and Hungary (21%). While substance abuse goes beyond alcohol (for instance, the global indicator framework aims at including coverage of treatment interventions for substance abuse), available data prevent a comprehensive assessment.

All OECD countries (except Colombia) experienced fewer deaths from road traffic accidents over the past two decades, but very few would have managed to halve the 2015 ensuing death rate by the end of 2020, as per Target 3.6 (Figure 2.9, panel B).30 While the available data on death rates due to road traffic injuries do not cover 2020 yet, 2019 data suggest that the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Sweden are the only countries that may reach that target.

Target 3.7 focuses on access to sexual and reproductive health care, but available data only allow tracking the adolescent fertility rate. Adolescent fertility rates have been declining in almost all OECD countries. While the 2030 Agenda does not set any numerical target, this rate is benchmarked against the distribution of OECD outcomes in 2015.31 This implies that the target is set at 3 per 1 000, and the distance to target is considered to be long when this rate exceeds 27 per 1 000. In 2018, very few OECD countries (Mexico, Chile, Costa Rica and Colombia) showed high adolescent fertility rates relative to those standards. Figure 2.9, panel B, shows that over the past two decades, adolescent fertility rates declined in all countries (i.e. progressing towards the target) with the exception of only four countries (the Slovak Republic, Mexico, Hungary and Czech Republic).

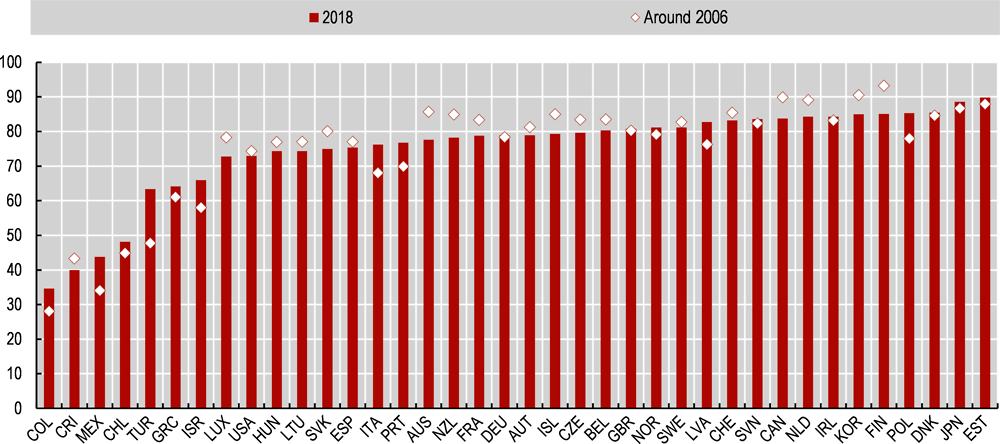

Despite high coverage rates for core services in all OECD countries, barriers to access to health care persist (Target 3.8). In the global indicator framework, the coverage of essential health services is the first measure proposed to monitor access to universal health care. Most OECD countries have universal (or near-universal) coverage for a core set of health services, but while the share of a population covered offers an initial assessment of access to care, it is only a partial measure of accessibility and coverage. The notion of universal health coverage also depends on the range of services covered and the actual provision of such services (OECD, 2019[48]). Yet, these additional factors are not covered by the measure included in the global indicator framework. For global monitoring, the IAEG-SDGs proposed to use the Universal Health Service Coverage Index. This measure of service coverage (defined as people receiving the service they need)32 shows that, despite constant progress in all OECD countries, none have yet been able to reach top scores, nor are they expected to meet them by 2030 (operationalised at 97%). In addition, barriers to access persist, particularly amongst the less well-off (OECD, 2019[48]). The second measure proposed in the global indicator framework is the proportion of population with large shares of household expenditures on health. On average, health expenditures exceed 10% of total household expenditures for around 8% of OECD residents. For the latest year available,33 this share exceeds 10% of the population in Belgium, Estonia, Poland and Chile and is above 15% in Latvia, Greece, Portugal, Switzerland and Korea.

Overall, while mortality attributed to unsafe water is not an issue for OECD countries, air pollution is a major cause of death, and its impact is likely to be even greater in the future. Target 3.9 aims at reducing the number of deaths due to pollution and contamination. For global monitoring of Target 3.9, the IAEG-SDGs proposes three measures: mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution; mortality rate attributed to unsafe water, unsafe sanitation and lack of hygiene; and mortality rate attributed to unintentional poisoning.34 In 2016, among OECD countries, mortality rates from unsafe water were on average close to 0, but ambient (outdoor) and household (indoor) air pollution caused about 40 deaths per 100 000 people (crude death rate). On the latter, distances are short (i.e. less than 9 deaths per 100 000) in Sweden, Canada, Finland, New Zealand, Australia and Iceland, but longer (above 20 deaths) in 15 OECD countries and above 30 deaths in Lithuania, the Slovak Republic, Mexico, Colombia, Poland, Hungary, Latvia and Turkey. While the data included in this report do not allow to track progress for premature deaths from exposure to ambient air pollution over time, projections suggest that by 2060 outdoor air pollution may cause 6 to 9 million premature deaths a year worldwide and cost 1% of global GDP as a result of sick days, medical bills and reduced agricultural output (OECD, 2015[51]). Target 3.9 also includes deaths from accidental poisoning. In this area, results are mixed. Deaths from accidental poisoning are on average rather low (at 4 per 100 000 in 2018), and more than half of OECD countries are likely to maintain low death rates or even reduce them. Yet, four OECD members report more than 9 deaths per 100 000 population (Canada, the United States, Estonia and Finland), and 19 of them did not achieve any progress towards the eradication of deaths from poisoning in the recent past. In many of these countries, deaths from accidental poisoning have been driven by overdoses from opioids (OECD, 2019[52]).

Whilst smoking rates are declining in most countries, too many OECD adults still smoke every day. Target 3.a, which refers to “strengthening the implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control”, is to be monitored by the prevalence of current tobacco use. With more than one in ten adults smoking daily, most recent data (2018 or latest) suggest that distances to target are long in all OECD countries except Costa Rica, Mexico, Iceland and Norway. Smoking rates even exceed twice this rate in Latvia, France, Switzerland, Hungary, Greece and Turkey (Figure 2.8). Daily smoking rates have decreased in most OECD countries over the last two decades, but the current pace of progress will not allow eradicating tobacco use by 2030. Using OECD data, the only country that is expected to meet the target is Costa Rica, where only 4% of the adult population were smoking every day in 2018.35 Overall, smoking rates have not declined significantly in five OECD countries (including France, Portugal, Austria, Turkey and the Slovak Republic) in at least one of the data sources.

Vaccination levels are high in all OECD countries, but some have experienced significant reductions over the last decade. Target 3.b aims at supporting research and development of vaccines and medicines and providing access to them. As such, this target includes three types of indicators: the proportion of the target population covered by vaccines, ODA to medical research and basic health sectors, and proportion of health facilities that have a core set of essential medicines available. Based on 2019 data, most OECD countries comply with the WHO recommendation of vaccinating more than 90% of the target population against DTP (36 OECD countries), measles (36) or pneumococcus (33). Immunisation rates are, however, much lower for human papillomavirus, and distances are considered to be short in only eleven OECD members (i.e. more than 78% of the population is vaccinated). However, over the last decade, vaccination rates did not progress or have fallen in around one-third of OECD countries. As discussed in OECD (2019[48]), eroding public confidence in the safety and efficacy of vaccination, despite the lack of scientific evidence to support this loss of confidence, may have played a role in declining coverage in some countries.

Beyond vaccination, Target 3.b also aims at boosting development assistance to poorer countries for medical research, but, as detailed in previous sections, while there is a clear international benchmark for total ODA provided by donor countries, the ideal sectoral breakdown of this aid depends on the needs of each recipient and the priorities of each donor. OECD data nonetheless show that ODA for basic health has increased significantly over the past decade (with more than half of the total coming from the Global Fund, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the United States government). Finally, Target 3.b aims at fostering the creation of health facilities that offer a core set of essential medicines at affordable prices, but the lack of data prevents assessing this dimension of the target.

Target 3.c focuses on increasing the health workforce and is monitored through indicators on the number of health workers per 10 000 population (including dentists, nurses, midwives, pharmacists and physicians). These indicators are considered as contextual and therefore are not included in the measure of performance. Some OECD reports (e.g. (OECD, 2019[48]) provide background information on current levels and trends in the health and social care sector. They show that, in OECD countries, health and social systems employ more workers now than at any other time in history (about one in every ten jobs is found in health or social care).

Overall, performance under the International Health Regulations (IHR) is very unequal among OECD countries. Target 3.d aims at strengthening the capacity for “early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks”. A country’s progress in this area is measured through two sets of indicators: International Health Regulations capacity and health emergency preparedness, and measures of antimicrobial-resistant organisms. Yet, available data only allows assessing the first segment of the target. While disease outbreaks and other acute public health risks are often unpredictable and require a range of responses, IHR provide a legal framework defining people’s rights and governments’ obligations when handling public health events and emergencies. This legally binding instrument is used to monitor progress towards Target 3.d on preparedness for health emergencies. The indicator is defined as the percentage of attributes of core capacities,36 with 100% as the implicit target (operationalised at 97%). Based on 2020 observations, performance on this indicator is diverse among OECD countries, with three groups of similar sizes: 11 countries are at a short distance from the target (i.e. more than 91% of the core capacities has been attained), 15 countries are at a medium distance, and 12 are considered to be at a long distance (i.e. attainment of less than 78%). Current trends show that while most OECD countries have been making progress at a pace that would allow them to reach 97% coverage by 2030, six are progressing at an insufficient pace, and nine do not show any progress towards the target level.37

Summing up

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, while most OECD countries made significant progress in many areas of health, the pace of progress has been insufficient to meet all Goal 3 targets (Figure 2.9). Before the pandemic hit, countries were closest to meeting the targets relating to reproductive, maternal and child health, with virtually all OECD countries achieving very low maternal and infant mortality rates and most on a decreasing trend for adolescent fertility (Targets 3.1, 3.2 and 3.7). However, most OECD countries also experienced difficulties in the other areas covered by Goal 3. For instance, despite significant progress over the last two decades, unhealthy behaviours (Targets 3.5 and 3.a) and poor environmental conditions (Target 3.9) have been fuelling premature mortality (Target 3.4). While most OECD countries made significant progress towards Target 3.3 on ending the epidemics of AIDS and tuberculosis and reducing hepatitis B, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a painful reminder that communicable diseases may pose unpredictable challenges. As OECD countries confront lower public confidence in the safety and efficacy of vaccines and the spread of antibiotic-resistant infections, it remains more important than ever to build inclusive and effective health-care systems. While the majority of OECD countries have universal or near-universal coverage for a core set of essential health services, providing universal health coverage also depends on the range of services covered and the degree of cost-sharing for these. Some issues persist on these fronts, and no OECD country is expected to achieve true universal coverage by 2030 (Target 3.8).

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Goal 3

While no reductions of child mortality (Target 3.2) have been reported so far, several studies reported significant declines of preterm births (the leading cause of child mortality) occurring during lockdowns. These declines were observed in many different countries, including Israel, Italy, Denmark, Ireland, the United States and Japan (Philip et al., 2020[54]; Been et al., 2020[55]; Meyer et al., 2021[56]; De Curtis, Villani and Polo, 2020[57]; Maeda et al., 2020[58]; Hedermann et al., 2020[59]). Some of these studies also reported significant reductions in the numbers of admissions to neonatal intensive care units. The reasons for these declines are unclear. However, the COVID-19 lockdown has drastically changed our lives by changing our working environment (including commuting), reducing physical interactions and increasing our focus on hygiene. This unusual situation is likely to have influenced several risk factors for premature birth.

COVID-19 is a communicable disease and, as such, it has a direct impact on the achievement of Target 3.3. More broadly, by disrupting the continuity of care, the COVID-19 pandemic also had a knock-on effect on the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of both communicable (Target 3.3) and non-communicable (Target 3.4) diseases (Table 2.6). First, to absorb the pressure put on health systems and to handle the influx of patients during the pandemic, routine and non-emergency medical care was temporarily interrupted in many countries (OECD, 2021[60]). In addition, early surveys suggested that patients had been delaying or even avoiding essential care out of fear of contracting the virus or concern about overstressing the health-care systems (American College of Emergency Physicians, 2020[61]; Lazzerini et al., 2020[62]; Van Mol et al., 2020[63]). These two factors led to significant delays in or even avoidance of medical treatments, which might have increased the morbidity and mortality risk associated with treatable and preventable health conditions, thereby contributing to excess deaths in the short, medium and long-term. In addition, some evidence suggests that unhealthy lifestyles and increased anxiety associated with the lockdowns may have long-term effects on cardiovascular disease (Mattioli et al., 2020[64]). Conversely, protective measures put in place during the crisis led to fewer fatalities from other communicable illnesses, such as seasonal flu (Jones, 2020[65]). In addition, although in the early periods of the pandemic suicide rates were expected to increase due to a decline in the population’s mental health, a deepening economic crisis and lack of access to mental health services, data from 2020 and 2021 do not show any considerable change compared to previous years (OECD, 2021[16]).

The anxiety induced by the pandemic and its aftermath is nevertheless likely to impact significantly on the consumption of addictive substances (Targets 3.5 and 3.a). The potential effects of stress and isolation on alcohol misuse (Target 3.5), tobacco consumption (Target 3.a), substance abuse and other addictions has been largely documented (Dubey et al., 2020[66]). The COVID-19 pandemic and its associated government measures to limit mobility have impacted pre-pandemic patterns and sites of alcohol consumption (OECD, 2021[67]). Some of the problems associated with harmful alcohol consumption were intensified by the crisis, such as engaging in harmful drinking to cope with stress or domestic violence (OECD, 2021[67]). Looking at preliminary data on government tax receipts, alcohol sales rose by 3% to 5% in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States in 2020 compared to 2019 (OECD, 2021[67]). Early evidence based on household final consumption expenditure (System of National Accounts) suggests a significant increase in the aggregate, “Alcoholic beverages, tobacco and narcotics”. Focusing on the different items separately suggests that most of this surge is led by a rise in the consumption of alcoholic beverages (while the decrease in the consumption of tobacco seems to be milder than it used to be in many countries, suggesting that either fewer smokers than usual quit tobacco in 2020 or that those who did not quit smoked more).

The substantial drops in mobility observed during lockdowns resulted in large decreases in road accidents (Target 3.6). The most recent data collected by the International Transport Forum (ITF, 2020[68]) show significant reductions in the number of road fatalities during the first few months of 2020.38 However, ITF (2020[68]) also highlights that that the number of road deaths has not fallen in proportion to the decrease in traffic. Furthermore, country evidence (e.g. France (ONISR, 2020[69])) suggests an increase in motor vehicles’ average speed and in the severity of road accidents. Fewer road fatalities reflect, however, the strict containment measures and are not likely to last as more cars come back on the road and economic activity resumes.

The disruption of health services induced by the COVID-19 crisis may have short-term effects on access to reproductive health care (Target 3.7) and vaccinations (Target 3.b). Stringent and lengthy lockdown measures adopted to avoid health systems being overwhelmed have resulted in significant disruption of essential services. Based on a survey conducted among 105 countries at various levels of development from different world regions, WHO (2020[70]) suggested that routine immunisation services and family planning and contraception services had been among the most impacted.