copy the linklink copied!2. Innovation capacity in cities – an empirical perspective

Cities are becoming key actors in the advancement of public sector innovation. This chapter presents the findings of the OECD/Bloomberg Survey on Innovation Capacity in Cities. First, it presents the strategy and goals cities have adopted to realise innovation. Then the chapter discusses the organisational arrangements for innovation, which examines components such as leadership, innovation teams, funding and human resource management. The chapter will then move to present the findings on data management capability, which is considered a key element in enhancing innovation capacity in city government. Finally, this chapter will discuss the governance mechanisms that facilitate public sector innovation, such as citizens’ participation in policy making and partnerships with a wide range of stakeholders.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

copy the linklink copied!Strategy and goals

Formulate an innovation strategy with a clear political message

Only 9% of cities that participated in the OECD/Bloomberg Survey on Innovation Capacity in Cities indicated they have a formal innovation strategy to improve processes, service delivery or make a better management of resources. A formal “innovation strategy” is a key document that highlights the city’s priorities and objectives on pursuing innovation and the way to achieve them. It also provides a long-term approach or vision to innovation. In many cases, the strategy is the product of collaboration among city administration, community leaders, academia, private sector representatives and residents. Furthermore, it is a way of signalling that innovation does not occur suddenly or by chance, it results from a long-term iterative process that integrates inputs, procedures and outcomes.

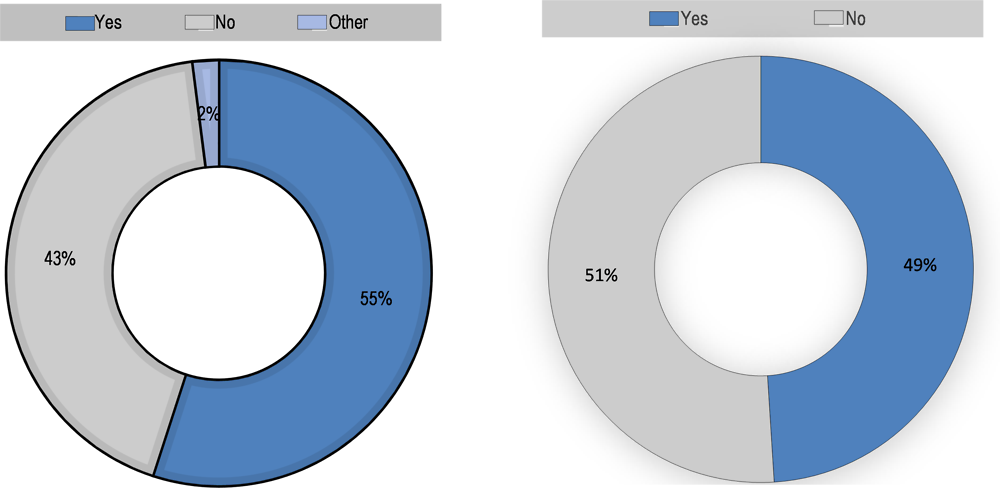

The strategy’s main advantage is that it can help encourage and justify cities’ efforts to stimulate their long-term capacity to innovate in a strategic manner. “The explicit incorporation of innovation goals and objectives of an organization is the first step to create attitudes amenable to creativity and to continuous development of new products.” (Alves et al., 2007, pp. 28-29[1]). Conversely, having innovation goals is not always akin to having an innovation strategy. Overall, 55% of cities reported having formal innovation goals, while 56% reported that they had no formal innovation strategy (Figure 2.1).

However, of the cities that reported having innovation goals, a large majority did not have a formal innovation strategy. It should be noted that the survey did not specifically assess the quality and scope of these existing innovation strategies, which may vary significantly across cities, although research suggests that an innovation strategy should consist of a high-level, long-term vision indicating the direction the organisation wants to develop and should include concrete yearly plans (Byrne et al., 2018[2]). The innovation strategy could have a three to five year vision depending on the political system and organisation of each city.

-

Kansas City, KS (United States) convened leaders from agencies and departments across the administration, resident and neighbourhood associations, and civic leaders to develop an innovation strategy resulting from an evaluation of where the city was falling short with service delivery. Kansas City’s innovation strategy focuses on operational efficiency, customer experience and citizen engagement.

-

Peoria, IL (United States) has a recently developed innovation strategy that was shaped by the Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Innovation Teams programme. This innovation plan involves a regular (every 18-24 months) alignment with the city’s overall strategic plan and assessment of evolving city challenges in order to identify priorities for the innovation team and establish partnerships both inside and outside city hall to address those challenges.

-

Stockholm’s (Sweden) innovation strategy (adopted by the Stockholm City Council in November 2015) provides an inward-looking perspective where innovation plays an important role in the improvement of city operations. It also provides an external perspective as it gives weight to the need to contribute to the overall development of the Stockholm region’s innovation capacity and work.

Source: OECD/Bloomberg Survey on Innovation Capacity in Cities 2018.

Innovation strategies help build a city’s innovation activities

Cities with a formal innovation strategy reported being more experienced with activities that foster innovation than those that do not have a formal strategy. Having a formal innovation strategy helps expose cities to innovation-related tools and activities (Box 2.2). According to the results of the survey, there are a number of tools and activities cities may rely on to strengthen their innovation capacity. However, the number of tools and activities a city is familiar with can depend on that city’s administrative culture, financing, regulation and political context.

Organisational arrangements

Reforming institutional practices entails changing the habits of municipal bureaucracy to create a more dynamic workplace. Cities are working towards this by silo busting, changing how they evaluate workers’ performance, training staff in innovation techniques and rethinking their contracting and procurement procedures (OECD, 2017[3]).

Integrating human-centred design is a framework for design and management that develops solutions by involving the human perspective in all steps of the problem-solving process. By studying the experiences of end-users, cities are developing new approaches to various public services (transportation, planning, housing, etc.). This framework includes prototyping experimental ideas to mitigate risks before scaling them up.

Rethinking approaches to finance and partnerships involves the creation of new budgetary and governance models to leverage greater funding and increase returns on public investment. Some cities are reconsidering their approach towards public-private partnerships while others are pursuing improved collaboration with neighbouring jurisdictions through the lens of multi-level governance (Taylor and Harman, 2016[4]).

Adopting foresight, prospective exercises, scenario planning refers to efforts to develop proactive, future-oriented policies. Cities are able to make dramatic long-term transformations possible by outlining general visions of their ambitions before tailoring specific, shorter term policies to transform their visions into concrete realities (Dixon et al., 2018[5]).

Data management capability

Data-driven analytics/public data management involves the use of digital systems in order to offer policy makers a more holistic understanding of urban systems and help them better analyse and evaluate the impacts of public policies. Cities are working towards this by investing in new data storage and analytic infrastructure, developing big data strategies, and launching open data platforms (Kitchin, 2014[6]).

Developing new technology-based solutions refers to the use of digital technology to more efficiently allocate resources, improve infrastructure resilience and generate a knowledge-based economy. Cities are pursuing these goals by investing in things such as fab labs and smart sensors (Buck and While, 2015[7]).

Openness to partnership

Engaging residents in new ways entails perceiving residents as active agents and valuable partners capable of offering municipalities key insights on how to improve cities. As part of this paradigm shift, cities are developing new digital communication platforms to receive constituent feedback and are co-creating public services (Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers, 2015[8]).

Sources: Brown, T. and J. Wyatt (2010[9]), “Design thinking for social innovation”, https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/1020-797X_12_1_29. Dixon, T. et al. (2018[5]), “Using urban foresight techniques in city visioning: Lessons from the Reading 2050 vision”, https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094218800677; Taylor, B.M. and B.P. Harman (2016[4]), “Governing urban development for climate risk: What role for public-private partnerships?”, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614692; OECD (2017[3]), Fostering Innovation in the Public Sector, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264270879-en.

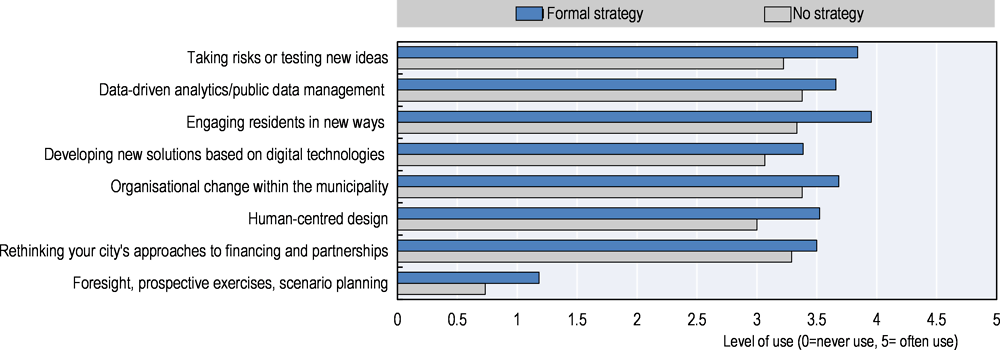

Figure 2.2 shows that cities with a municipal innovation strategy tend to use with greater frequency a wide range of innovation tools and activities. A clearly defined formal strategy can enable cities to better allocate their resources to achieve the goals of municipal leaders (Knutsson et al., 2008[10]). Yet, to be truly effective, a strategy must be known and owned by public servants. Public employees must incrementally implement the municipal strategy on a daily basis. Managed this way, a strategy can improve municipal outcomes not only by dictating resource allocation from the top, but also from the “bottom up”, by allowing municipal employees to situate their own work within the overall context of the larger organisation (Knutsson et al., 2008[10]).

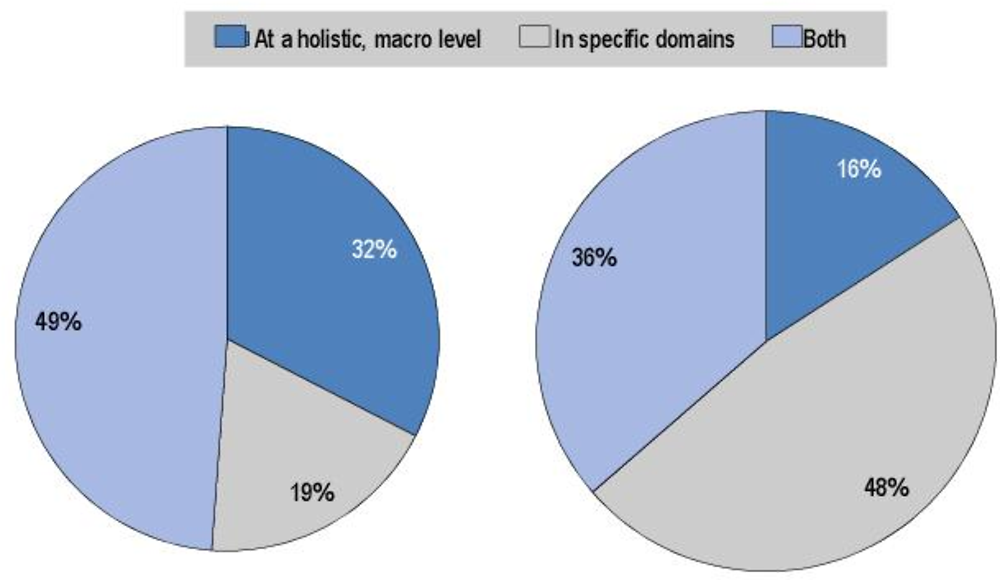

Cities with an innovation strategy tend to approach innovation much more holistically. This is a way for the local administration to see the innovation strategy as a process for problem solving that can be applied in multiple policy domains and challenges. A holistic approach ensures that every sector or area in the administration is brought into the effort to build innovation. Moreover, cities with a formal innovation strategy are more likely to have formal innovation goals. There are, however, cities with a formal innovation strategy that do not have explicit innovation goals. In these cases, cities tend to have a long-term development vision that stresses the need for innovation. A few cities have adopted a holistic approach to innovation without a formal strategy.

On the other hand, as the survey revealed, most of the cities that do not have a formal innovation strategy tend to focus on innovation efforts within specific domains – such as education, poverty or economic growth – to foster their innovation capacity. Some cities have innovation teams that focus on both specific topics and teaching innovation techniques to the whole organisation. By developing a formal innovation strategy, municipalities put themselves in a position to consider how changing practices will affect their work across departmental boundaries. Moreover, the implementation of an innovation strategy can help create the institutional space and resources for cross-cutting initiatives.

When cities were asked whether they approached innovation within specific policy domains, holistically or both, only 19% of the cities that indicated having a formal innovation strategy also indicated that their innovation work was isolated to specific policies. This stands in stark contrast to cities without a formal strategy, among which almost half (48%) stated to approach innovation work only within particular policy sectors.

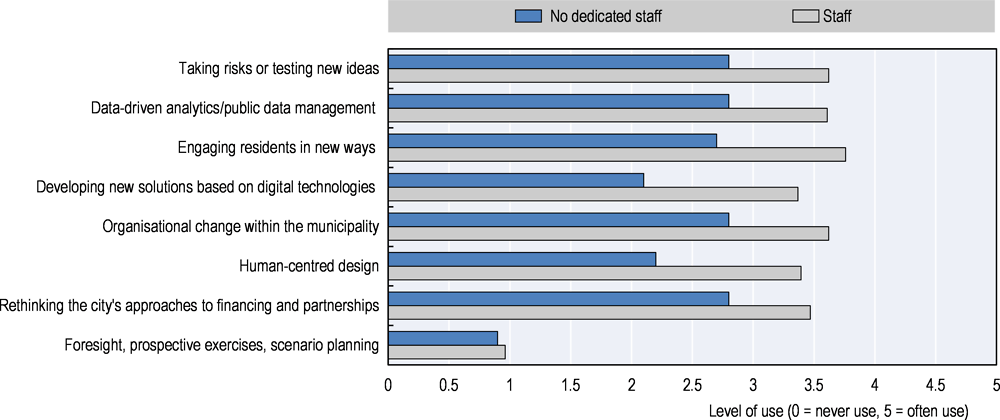

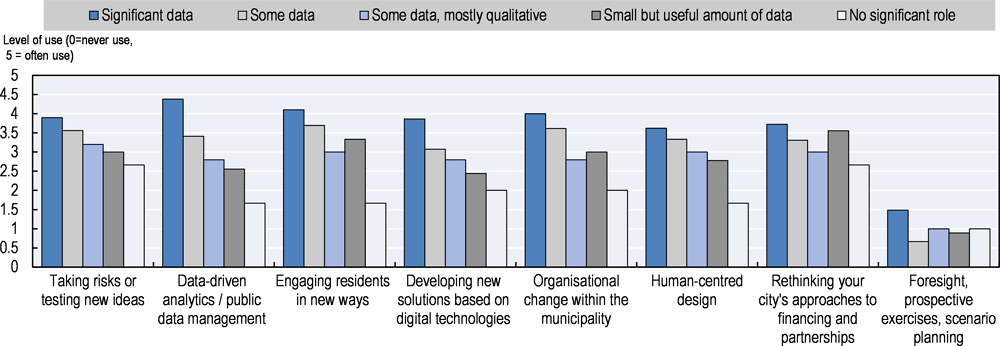

Figure 2.4 shows that the most common approaches and practices across cities related to innovation capacity are taking risks or testing new ideas; data-driven analytics and public data management; organisational change within the municipality; and engaging residents in new ways (see Box 2.2). However, this picture changes when considering the adoption of a formal innovation strategy.

Indeed, an innovation strategy may suggest a different approach to innovation. As Table 2.1 shows, cities with a formal innovation strategy tend to be more open to take risks and pursue organisational change, whereas those without a strategy are more focused on data-driven analytics and rethinking the city’s approach to finance and partnership. Interestingly, a large majority of cities reported that they are working toward finding new ways to engage residents in policy making. This is not surprising as most of the innovation strategies reported by cities refer to the need to obtain citizen input and support for designing and implementing innovative policies and projects.

One area where all cities seem to lack experience is in conducting foresight and prospective exercises. One explanation for this could be due to the political and administrative culture as urban planners have only sporadically engaged with futures studies to develop long-term city visions. For example, in some countries, mayors have short terms in office and no possibility for re-election. “Urban planning … remains a predominantly short-term and medium-term activity (or 15-20 years ahead), rather than looking to the longer-term of 2050 and beyond” (Dixon et al., 2018, p. 781[5]). Another issue may be that, because of politics or people’s demands, cities look predominately at the problems right in front of them.

Cities with a formal innovation strategy tend to associate innovation with rethinking its administrative organisation based on a human-centred design. This means that we can improve societal problems – like poverty, lack of security, access to clean water and environments – but solutions lie in the people who face those problems every day. The solutions are found by working together with the communities affected by those problems, as it allows for the creation of new solutions rooted in people’s actual needs (Byrne et al., 2018[2]). Cities without a formal strategy tend to associate innovation more frequently with technological developments. The large majority of cities acknowledge the importance of experimentation for innovation.

copy the linklink copied!Organisational arrangements

Advance new organisational structures that shape innovation capacity

Local governments’ structure and functions may affect, to a certain extent, the promotion of innovation. Individual members of staff, the teams they work in, the units where their teams are located, the organisation (agency or ministry) where they work, and the whole of the local public administration are important factors that influence the innovation capacity of the local public administration.

Table 2.2 presents some of the ways in which innovation may take place in public organisations at different levels of government. These levers should not be considered in isolation; they should be combined to achieve synergies and greater impact in the promotion of public sector innovation. Governments could take co-ordinated action across different policy levers to promote innovation. Table 2.2 is not meant to be exhaustive, as there are other elements of how the public sector, and in particular local public administration, is organised that will affect its capacity, willingness and opportunity to innovate. It should be considered that public sector innovation may be more successful, depending on the configuration of individuals, resources and personalities, and the local and national economic and socio-political context (OECD, 2017[3]).

Installation of innovation units/teams

The specific features of the workplace can largely impact innovation capacity

To effectively harness cities’ innovative capacity, it is essential to create the necessary conditions that support the inventiveness of the public workforce. The formal, codified, vertical relationships between executive authorities and the local public workforce and the horizontal relationships between the silos of different departmental agencies can strongly influence public sector innovation capacity. Yet, it is important to note that unspoken workplace habits and culture can also significantly incentivise public sector employees to either innovate or maintain the status quo. “Organisations’ cultural elements like routine behaviours, shared values and beliefs, influence the level and frequency of creative occurrences and impact on the free flow of ideas that favour innovation” (Alves et al., 2007, p. 29[1]).

The quantity and quality of human resources allocated to innovation teams and projects is likely to have a positive impact on the success of the plan. Employee motivation and involvement in the innovation process is of key relevance. Innovation capacity also depends on having public sector managers in top and middle positions with a change-oriented behaviour. For this to happen, it is very important to consider how risk taking is managed, how ideas are evaluated, and how mistakes are handled internally by middle and senior managers (Alves et al., 2007[1]; OECD, 2017[3]). The city administration’s human resource management should set incentives, such as compensation and career promotion, for employees to innovate. Moreover, innovation capacity also requires more flexibility in human resource management, allowing for job rotation and the flow of ideas, cross-departmental learning and teaming.

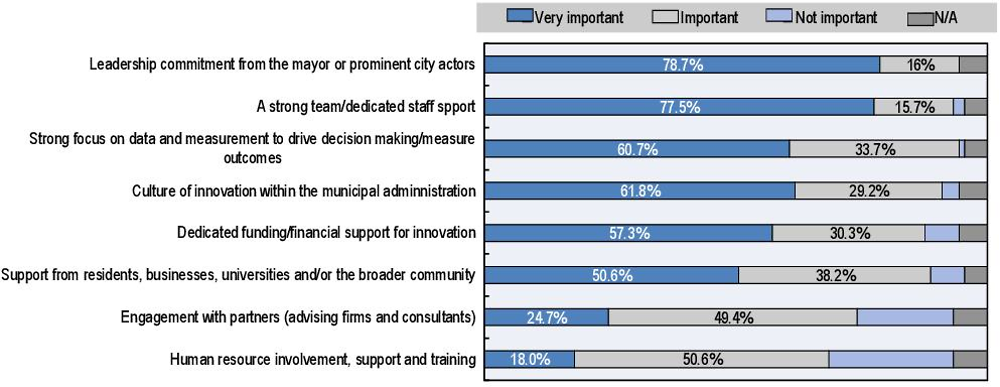

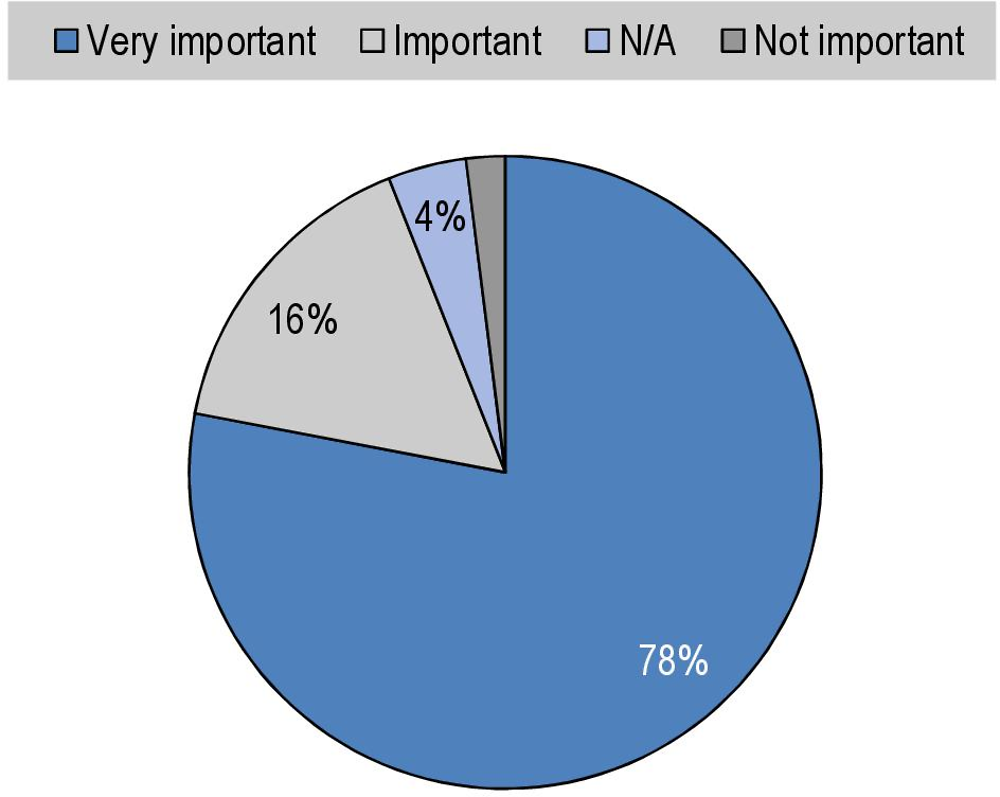

Leadership is an essential ingredient for supporting innovation capacity in cities

Political and managerial leadership has a key role to play in inspiring and supporting behaviour change in the city’s administration. According to the survey, cities rank leadership commitment as the most important determinant of successful innovation work (Figure 2.5). The role of politicians is likely to be extremely influential in the adoption of innovations as they set the political values, policy direction, priorities and decide on the allocation of resources (Walker, 2006[11]). Therefore, “… leadership buy-in and the direct support of the mayor appear to be crucial factors in how embedded innovation culture is within a city government” (Makin, 2017, p. 13[12]). In many instances, local political leaders may set their reputation on the promotion of innovation. This would not only bring prestige to the city as a reference point for other cities, but for the political leadership it could represent more legitimisation and increase citizens’ trust in their administration.

Managerial leadership is also crucial for the development of innovation capacity. City administrators, city managers or chief executives set the standards for how audacious civil servants can be in developing new approaches and projects. Executives at the head of municipalities and departments can strongly determine workplace culture in ways that human resource management may be unable. Moreover, executives play a crucial role in allocating the human and financial resources that can help implement an innovative policy agenda. There is still debate on whether managers should encourage stability to enhance institutional memory or allow mobility to bring in new ideas (Walker, 2006[11]). It seems important to have both: managers with deep historical knowledge and understanding of how the administration functions and managers who have skills gained from other institutions who can bring different perspectives to the fore. Middle managers also have a key role in developing innovation capacity by allowing for greater autonomy and flexible human resource management rules so that their teams can enhance the administration’s ability to innovate.

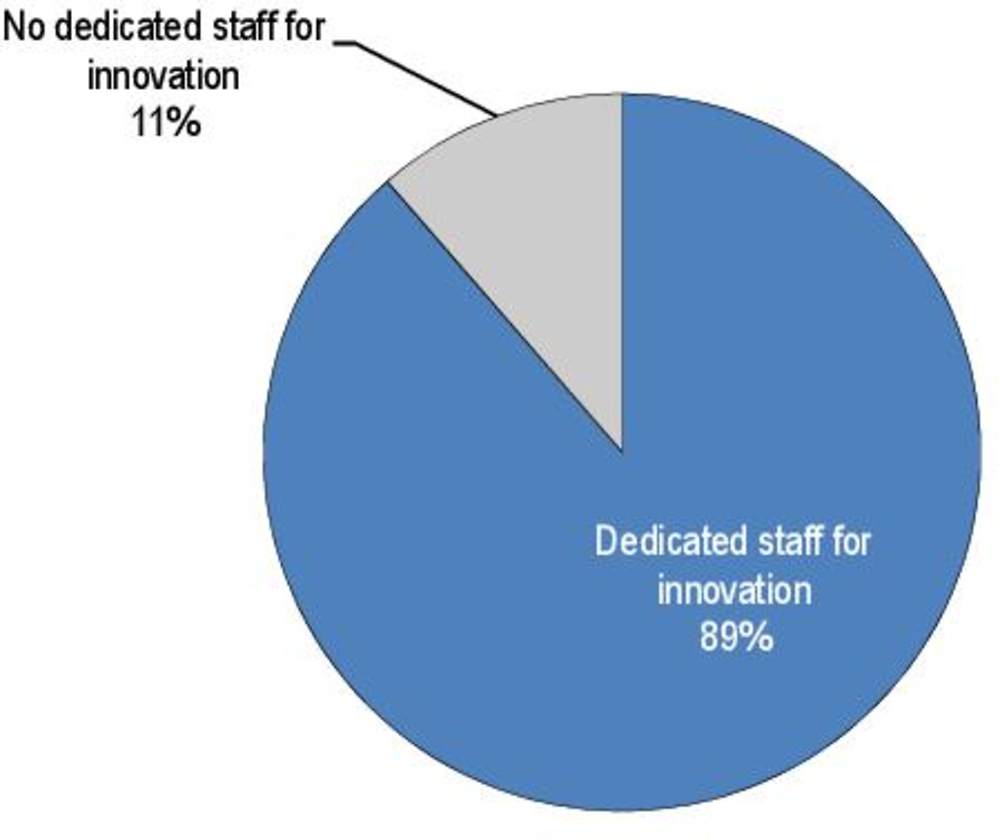

Specific innovation units may have a major impact on cities’ capacity to innovate

The creation of a dedicated innovation unit is a popular, if recent, tactic cities are deploying to help mainstream their innovation work. The large majority of cities surveyed (89%) have dedicated staff or teams to promote innovation (Figure 2.6). Survey results show that only 21% of innovation teams have been in place for more than five years. This suggests that the innovation units or teams may still require time to consolidate their job and produce results. Producing innovation is a long-term process that requires continuity and most of the innovation teams have existed for three years on average. A key challenge for cities is to ensure that the innovation teams survive changes in the administration and political leadership.1

OECD (2017[3]) research has found that innovation units can help overcome barriers to innovation through their different functions. Innovation teams have five broad functions: 1) supporting and co-ordinating the implementation of innovative solutions; 2) experimenting with different approaches to problems; 3) supporting cross-cutting and interdisciplinary projects; 4) ensuring the resources needed to give emerging ideas the space to grow; and 5) building capacity and networking support.

Survey results show that cities consider dedicated innovation units a crucial mechanism to cultivate municipal innovation capacity (Figure 2.7). These units or teams are generally thinking beyond the day-to-day to reimagine cities and the services they provide. However, a dedicated innovation team should not own innovation for the city. While their role is to facilitate and enable innovation, building capacity and skills for innovation is crucial (Makin, 2017[12]). The challenges for these teams are to transmit their energy, vision and skills to other teams throughout the administration, to build a culture of collaboration and to break down silos.

-

Cape Town’s (South Africa) Organisational and Innovation Department resides within the Corporate Services Directorate. Its purpose is to deliver strategic support to contribute to the efficiency and effectiveness of the city administration’s core mandate of service delivery.

-

Cincinnati, OH (United States) innovation function is housed within the Office of Performance and Data Analytics. The rationale is that performance management, data analytics and innovation are interdependent. This team works with the city manager to establish a comprehensive, integrated performance management programme for the city that includes performance management agreements, a CincyStat programme and an innovation lab focused on streamlining municipal processes. The five to ten person team works with departments to measure performance, evaluate success and identify areas of improvement. Its innovation lab helps agencies achieve efficiency gains through leaner and smarter operations, better and faster service delivery, and increased capacity for problem solving.

-

Jerusalem’s (Israel) Innovation Team (JLM i-team), is an independent senior consulting team that reports to the mayor directly. It works on strategic areas such as youth at risk, fostering business opportunities, education, building thriving communities and creative public space. Its independence allows it to build bridges across departments and organisations to achieve common goals. The team works with city partners to create lean and smart initiatives that, once successful, are scaled up.

-

New York, NY (United States) has set the Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity (NYC Opportunity) as an innovation lab focused on reducing poverty and increasing equity. The 60-person team conducts cross-cutting research, collects and analyses data, and formulates proposals for the city’s programme and policy development. Its work includes analysing anti-poverty approaches, facilitating data sharing across the city’s administration and assessing the impact of key initiatives. It works collaboratively with other agencies to design, test and oversee new programmes and digital products. It produces the annual Poverty Measure that provides a comprehensive picture of poverty in the city. NYC Opportunity relies on the following capacities/expertise: design, programme management, digital products, data integration, evaluation and research. It has a lot of capacity around human-centred and behavioural design.

-

Syracuse, NY (United States) has set an innovation team at the Office of Accountability, Performance and Innovation. Its aim is to help departments in the city administration to address citizen needs through data-driven decision making. Within the office, the divisions of data, innovation and accountability work interdependently. All innovation projects contribute to key strategic objectives such as: efficient, effective and equitable service delivery; increasing economic investment; providing quality constituent engagement and response; and achieving fiscal sustainability. The team uses a philosophy called Objectives+ Key Results to use data to measure change and drive innovation.

Sources: For Cape Town: Directorate Executives Summaries and Scorecards for 2018-2019. For Cincinnati: Office of Performance and Data Analytics, https://www.cincinnati-oh.gov/manager/opda. For Jerusalem: JLM i-Team, https://jlmiteam.org. For New York City: NYC The Mayor’s Office for Economic Development, www1.nyc.gov/site/opportunity/about/about-nyc-opportunity.page and presentation of Carson Hicks, Deputy Executive Director of the Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity, New York City during the webinar on “Advancing Cities’ Innovation Capacity” on 12 June 2019. For Syracuse: City of Syracuse Innovation Team, www.innovatesyracuse.com and presentation of Adria Finch, Director of Innovation, during the webinar “Accelerating Cities’ Innovation Capacity” on 12 June 2019.

Moreover, in an era of rapidly changing city environments, cities need to ensure they employ a skilled and adaptable workforce. They need to design high-quality learning and development strategies for local public servants to update, upgrade or even acquire new knowledge and skills. For example, the increasing reliance on ICT for public service delivery and on data-driven planning and decision making requires a digital skill set among the different areas of the city administration.

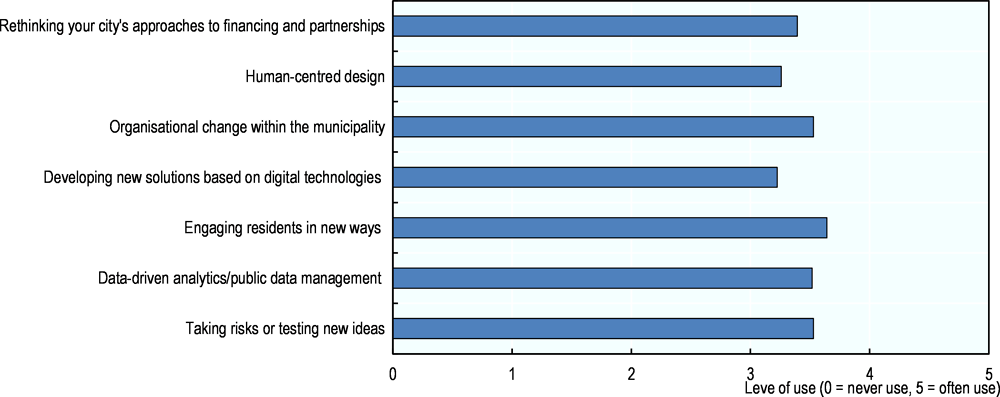

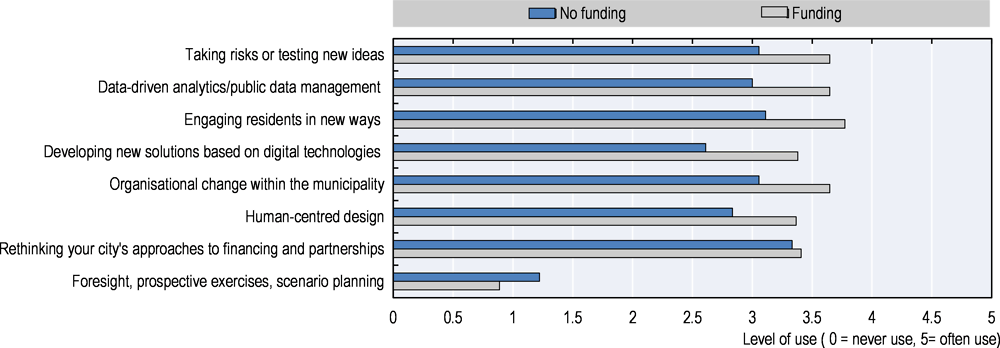

Having full-time municipal staff dedicated entirely to innovation appears to be one of the capacity-building factors that most strongly correlates with innovation work (Figure 2.8). On average, cities that hired dedicated staff reported significantly higher levels of familiarity with innovation work. The most significant differences between cities with and without dedicated staff occurred with respect to developing new solutions based on digital technology. Cities with dedicated innovation staff scored 60% higher levels of familiarity with developing new solutions based on digital technologies than cities without a dedicated innovation staff. The second-most significant domain of innovation work where staff capacity correlated with levels of use was human-centred design. Cities with dedicated staff recorded 54% higher levels of use than those of cities without any staff dedicated to innovation work.

Innovation teams generally sit at the mayors’ or city manager’s office

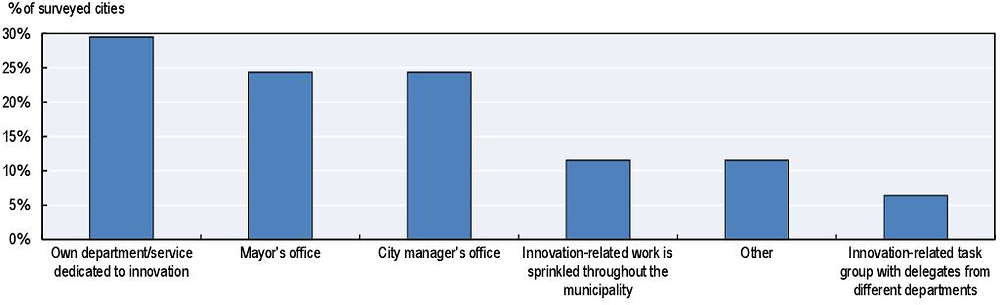

The organisation and structure of the “innovation units” vary significantly from city to city. Around half of innovation teams sit in the mayor’s or city manager’s office and nearly 30% have their own dedicated department (Figure 2.9). Yet a minority of cities have chosen to valorise peripheral knowledge in their innovation work by placing innovation units within specific departments or appointing delegates from departments to an innovation committee.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach for the location of innovation units within city administrations. It seems very dependent on the cities’ priorities and context. When cities see innovation as a powerful tool to foster cultural change in the administration and want to strengthen co-ordination, they usually establish the unit in the mayor’s office. When cities want to focus on a specific area – such as economic and social development, environment, transport, or housing – they tend to locate this unit in a specific department. Positioning the innovation unit under the mayor’s remit signals the intention to work across city departments and departmental boundaries to address city issues (Makin, 2017[12]).

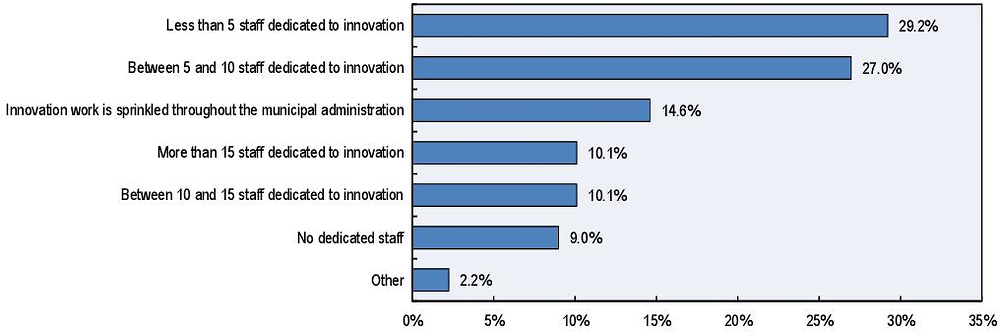

Innovation units are generally understaffed and are led by project managers

The large majority of responding cities have staff dedicated to innovation work. However, more than half (56%) have innovation departments with 10 employees or less; only 10% have more than 15 staff dedicated to innovation (Figure 2.10). The generally limited size of municipal innovation departments indicates that cities primarily view innovation work as complementary to the conventional work of city agencies.

Innovation teams can provide municipalities with a variety of key functions to bolster innovation capacity. They can serve as liaisons between departmental silos by creating networks to share best practices or by working to co-ordinate the implementation of cross-cutting innovation projects, such as digitisation. Dedicated innovation units can also serve as spaces for policy experimentation, where projects are conceptualised and prototyped on a small scale before expanding into other departments. The capacity of innovation departments to foster innovation depends on their relationship to municipal centres of authority. The closer the team is to the central executive power, the greater their capacity to effect change when leadership is bold and strong (Cohen, Almirall and Chesbrough, 2016[13]). The more in the periphery the team is, the more open to radical innovation it will tend to be (OECD, 2017[3]).

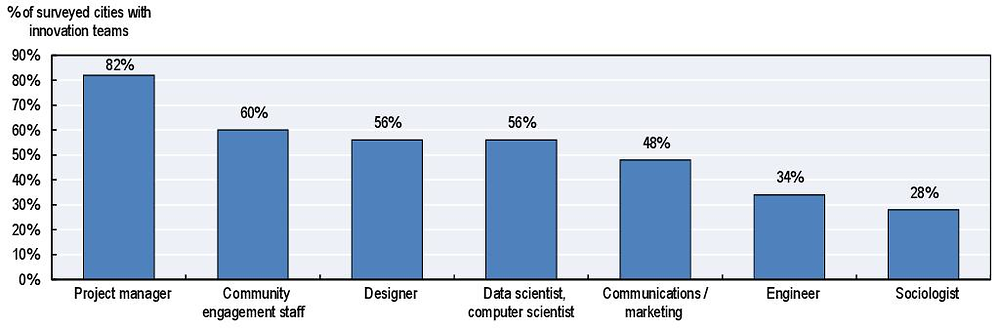

Innovation teams are, most often, led by people with project management skills. Indeed, survey results show that project manager (82%) and community engagement staff (60%) are the most common positions on innovation teams (Figure 2.11). It seems logical to have project managers leading innovation teams as their task is to co-ordinate the work of teams. Innovation requires giving more opportunities to city staff working in different service areas and departments to meet regularly to share ideas and work together towards a common goal (Makin, 2017[12]).

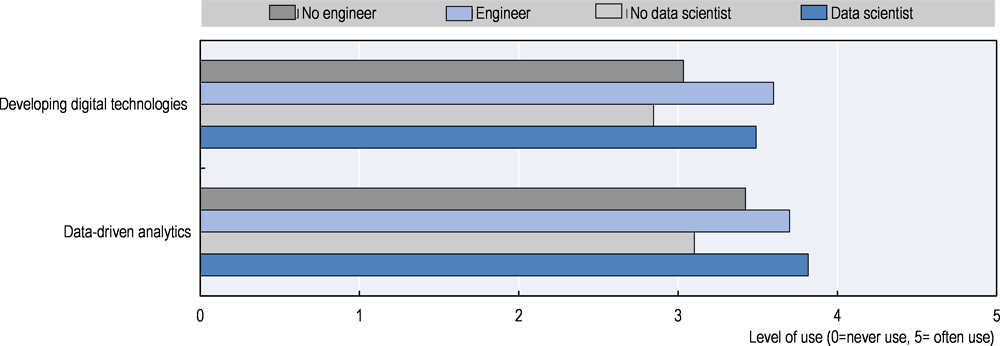

A comparison of cities’ levels of familiarity with innovation work according to the profiles of their staff members suggest that cities with computer scientists and engineers reported being significantly more familiar with innovations in municipal data analytics and digital technologies (Figure 2.12). Moreover, cities with engineers on staff had the highest levels of familiarity with implementing new digital technologies.

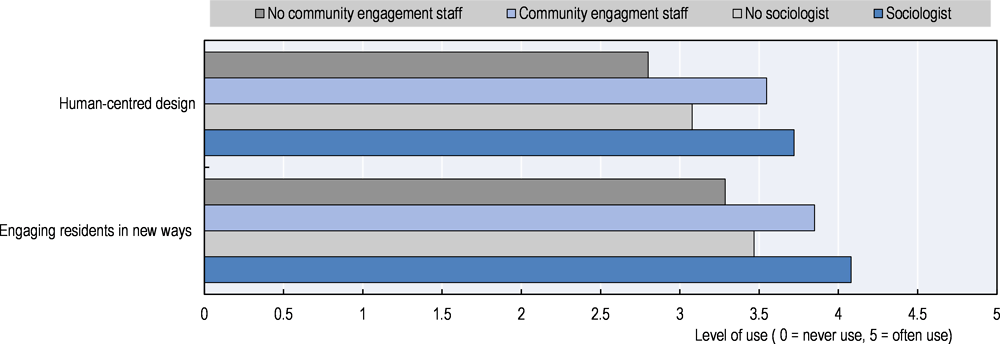

Similarly, cities that hired innovation staff with qualitative skills, such as human-centred design, proved much more effective than their counterparts at engaging residents in new ways (Figure 2.13). Cities that hired sociologists were correlated with the highest levels of familiarity with these two categories of work. Meanwhile, cities that lacked community engagement staff were 27% less familiar on average with human-centred design than their counterparts with dedicated staff for community engagement. Notably, cities with community engagement staff also scored 17% greater familiarity with risk taking than cities that lacked such staff.

Set up a specific financing framework

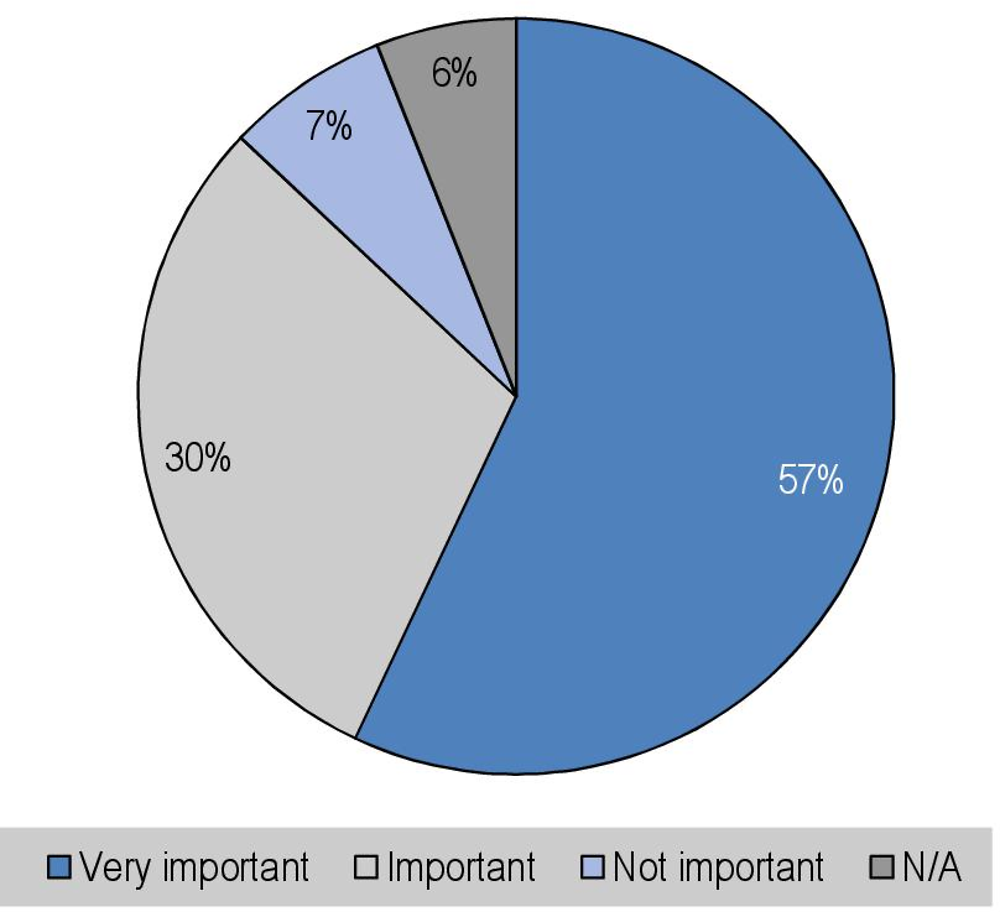

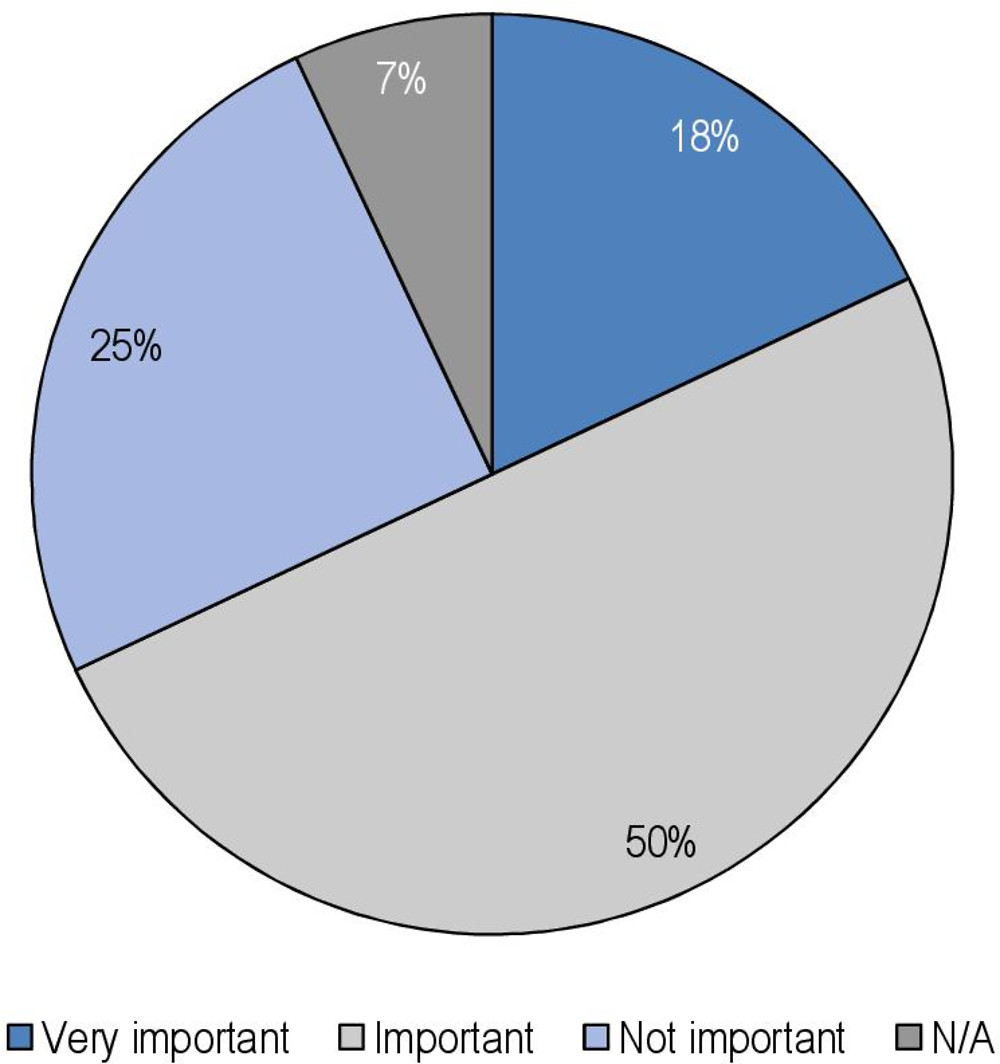

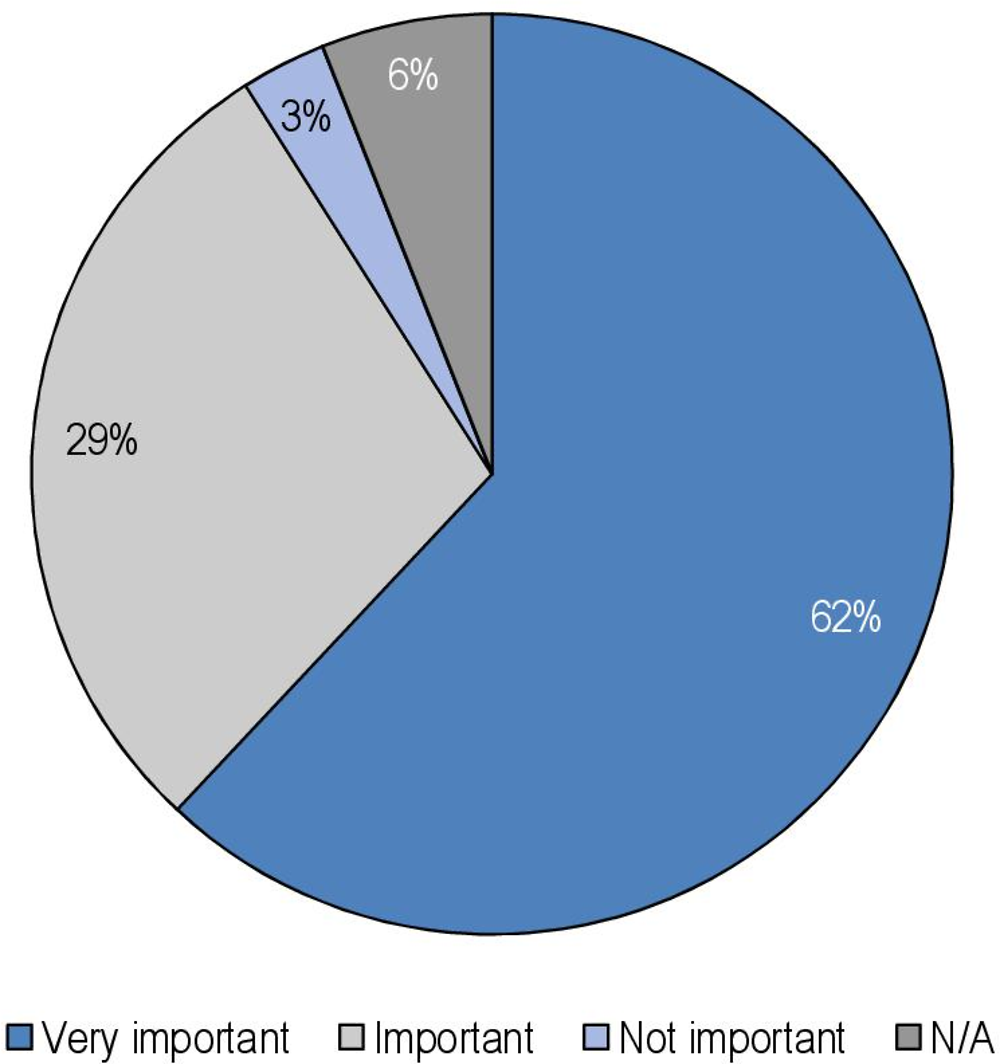

Although the large majority of responding cities (80%) have specific funding to support innovation, it does not necessarily mean that their resources are sufficient to finance innovation. This is particularly the case when cities need to deliver more with less. Yet, in many cities, budget reductions and cuts may be creating the conditions for innovation to occur. The way that a municipality finances innovation work can also strongly determine the implementation of new ideas. A large majority (87%) claimed that dedicated funding is at least somewhat important in determining innovation capacity (Figure 2.14). Sound sources of funding allow cities to conduct research, prototype or test new ideas, implement ideas on a larger scale, and recruit highly qualified staff. The city of Los Angeles, in its answers to the OECD/Bloomberg Survey on Innovation Capacity in Cities, suggests that dedicated funding for innovation projects is essential to feel comfortable trying new things. It is then easier for government officials to use taxpayer money to continue or scale the work. At the same time, it is also much easier for residents to appreciate government experimentation and support innovation and transformation. In the experience of the city of Los Angeles, it can be hard for government to budget for innovation and specific tools and projects until they are proven.

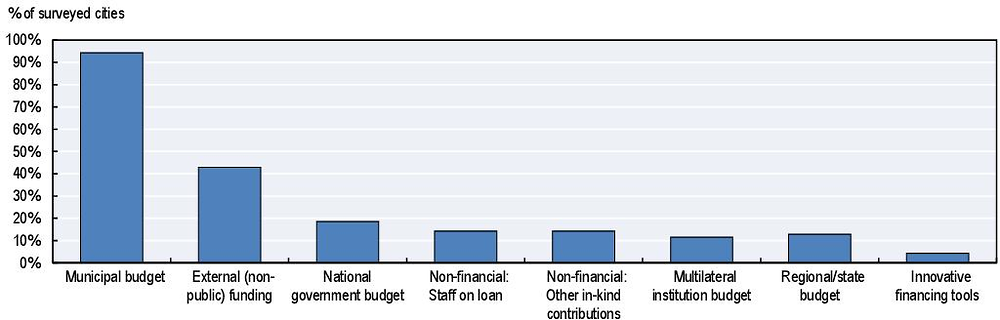

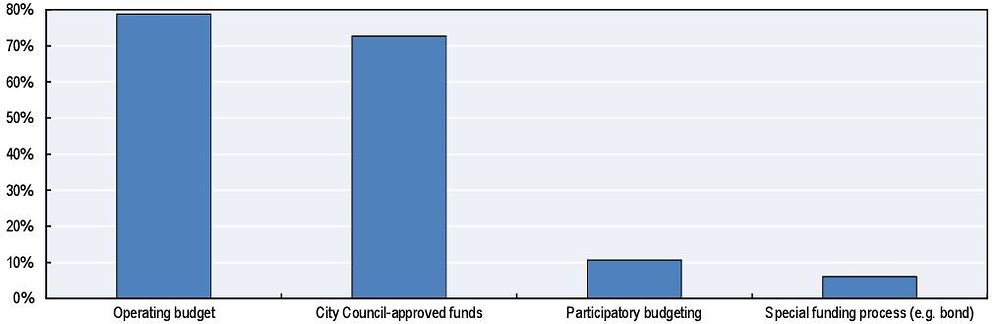

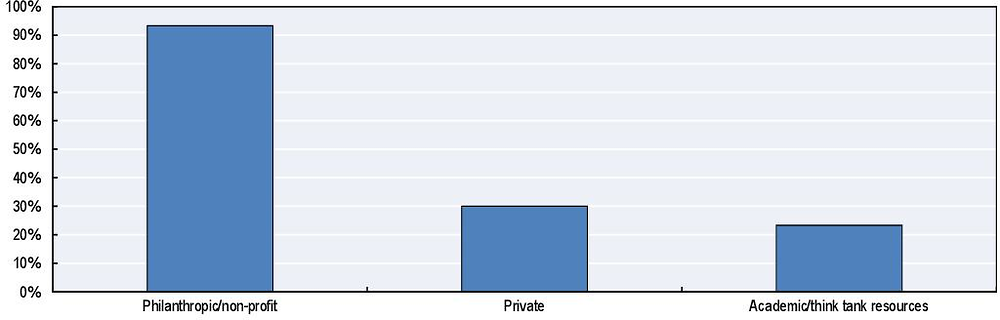

Among the cities with dedicated funding for innovation, the vast majority (94%) have— set aside resources from the municipal budget to fund part of their innovation work (Figure 2.15). This occurs through the operating budget and by funds approved through the city council. The next largest source of municipal innovation funding is external partners from outside the public sector. Cities rely on non-profit organisations (i.e. foundations, philanthropy) for this funding, with relatively few relying on private sector investments or support from a national government budget.

Municipal budget

-

Madrid (Spain) is funding innovation teams across departments in the city hall through the municipal budget to help them solve problems in new ways. Citizens and associations can propose ideas through participation platforms and the implementation is done via the municipal budget.

Municipal budget + external (non-public) funding

-

Louisville, KY (United States) is earmarking one part of the operating budget for innovation work, whereas innovation pilots and initiatives are funded through private and philanthropic partners.

-

Memphis, TN (United States) innovation team is made up of an external organisation called Innovate Memphis, whose funding is essentially a third of the core city budget for innovation capacity, a third the support of local foundations, and a third earned revenue projects or other programme-specific grants. The grant is from the general fund, funded by property taxes, and is 50% for personnel and 50% for programme support and tech development.

Municipal budget + external (non-public) funding + non-financial contributions

-

Philadelphia, PA (United States) Office of Innovation Management holds an allocated budget approved by the city council and the mayor under the Office of Innovation and Technology. GovLabPHL, a multi-agency team centred on embedding evidence-based and data-driven methods into city programmes and services, is funded through the mayor’s office and receives grant dollars for pilot projects. Swarthmore College and the University of Pennsylvania have been instrumental in providing financial and in-kind support to GovLabPHL initiatives, including an annual conference, year-round policy fellows and funding for randomised control trial pilot projects.

National government budget

-

Stockholm (Sweden) launched the Hub for Innovation, a three-year project funded by Sweden’s National Innovation Authority, Vinnova, in 2017. The hub supports a more innovative working culture within the city hall.

National budget + municipal budget + non-financial

-

San Francisco, CA (United States) innovation team receives funding from the city and, until recently, had a grant from the US Commerce Economic Development Agency to scale up Startup in Residence, a programme connecting start-ups with government agencies to co-develop technology solutions for government challenges. The city has also partnered with the State Department to host a foreign service officer as a member of the team for one year.

International sources

-

Ljubljana (Slovenia) hires its innovation team using EU co-funding.

Source: OECD/Bloomberg Survey on Innovation Capacity in Cities 2018.

There are several issues to consider in financing innovation in cities. First of all, municipalities need to allow innovative projects the budgetary flexibility to scale-up if successful, without removing oversights on how public funds are spent. For instance, the budget office in the municipality may allow and approve administrative units to reallocate funds within or across appropriations accounts to direct them to areas where innovation projects are taking place. It may be that different departments co-fund innovation work. Moreover, channelling funding for cross-cutting innovation work through dedicated innovation teams can help overcome the barriers that result from an inability to co-ordinate funding through distinct departmental silos. Another way to enhance flexibility is to allow unused funds to be carried over across fiscal years, with the approval of the budget office. Effective innovations in the internal operations of municipalities that deliver gains in efficiency will ideally in turn produce budgetary savings. In order to bolster long-term innovation capacity, these savings should be reinvested into scaling up promising experimental projects, deepening existing innovation efforts more broadly or developing new innovative projects (OECD, 2017[3]).

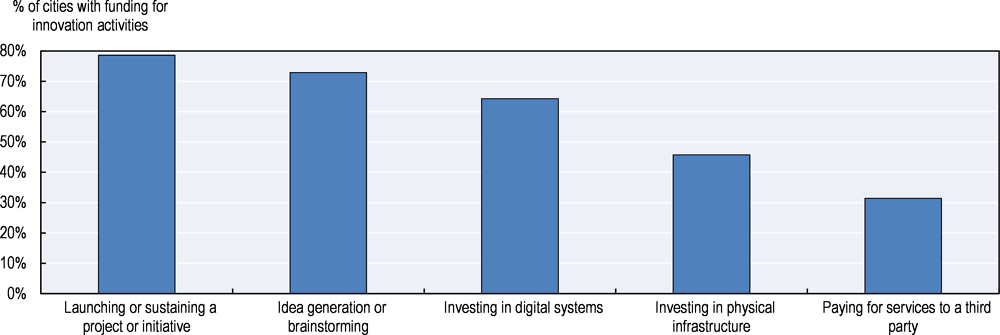

Cities are putting their dedicated funding for innovation to different uses. Most frequently (79%), innovation funding goes directly towards specific projects. Yet a majority of cities with funding for innovation are also investing in capacity building alongside specific projects, such as cross-cutting idea-generating sessions and skill-building workshops to build innovation methods. Cities also fund staff dedicated to innovation work.

Funding for innovation capacity may differ from year to year. In some cities, the innovation units need to send their budgetary requests to the management or budget office and funding may be given on a project-by-project basis. Therefore, funds could vary depending on the availability of resources.

In Houston, TX (United States), funds cover innovation staff and overhead and the city relies heavily on grants from academia and the city tech community.

In Jerusalem (Israel), the city’s i-team received ILS 10 million (New Israeli shekels) from the national government for its innovative projects; now the i-team receives 50% funding from a philanthropic organisation and 50% from the municipality.

Source: OECD/Bloomberg Survey on Innovation Capacity in Cities 2018.

Budgetary pressures are driving some cities to prioritise reactive measures instead of proactive activities, including innovation. OECD research has found that the budgeting routine in the public sector solves many problems for government, but it is certainly not calculated to prompt policy innovation (OECD, 2017[3]). Moreover, innovation in cities is only recently being legitimised as an area for investment within city administrations. However, cities’ investment in innovation is largely marginal in comparison to other expenses. In some cases, multi-level governance co-operation and international collaboration help to overcome budgetary constraints. Table 2.3 provides a general overview of public expenditure in subnational levels of government across OECD countries. It shows that compensation of government employees is, by far, the largest expenditure category. By area, education and health consume most of the resources.

Survey results indicate that cities that have dedicated funding for innovation are more familiar with implementing new ideas (Figure 2.19). The category of innovation work that most strongly correlated with dedicated funding was the use of digital technology to develop new solutions. Cities with dedicated funding were, on average, 21% more familiar with engaging residents in new ways and data-driven analytics than cities without funding.

It is also noteworthy that, apart from foresight exercises, the domain of innovation work that correlates the least with the presence of dedicated funding is rethinking approaches to financing. Cities with dedicated funding for innovation reported only an average of 2% greater familiarity with rethinking their finances than cities without dedicated funding. This is likely a result of the fact that cities facing budget shortfalls and conditions of austerity may also be incentivised to reconsider their finances, despite the fact that they lack the resources to consistently fund innovative projects.

Human resource management and administrative culture

Invest in the capacity and capability of local public servants

Cities can help create a climate for new ideas by ensuring a dynamic management of the public workforce, especially senior policy makers. For that, at least three aspects should be considered: 1) ensuring that the workforce has the right skills and competences needed (talent); 2) ensuring the workforce is representative of the population it serves (diversity); 3) creating a climate that motivates public officials to engage in innovation. The way these factors are managed may create positive change or inhibit the creation of a culture of innovation (OECD, 2011[15]; 2019[16]).

The survey results show that almost 70% of responding cities considered human resource (HR) management important in improving their capacity and capability to innovate (Figure 2.20). Interestingly, 25% of cities claimed that HR involvement was unimportant to their innovation work, but this may be because some cities are unaware of the impact human resource management has on innovation. Across the literature, there seems to be agreement that staff determines the success or failure of innovation in the public service (Makin, 2017[12]; Walker, 2006[11]; OECD, 2017[3]; De Vries, Tummers and Bekkers, 2016[17]). The key question is how to motivate staff to innovate and create the right conditions to harness innovation processes within the city administration.

Survey results show that cities believe that workplace culture is a significant factor in supporting their innovation efforts (Figure 2.21). However, that culture depends largely on the combination of the aspects analysed above: committed political and managerial leadership, HR practices, and the importance given to innovation in the budget.

Promote a culture of reasonable risk taking

Cities looking to foster innovation should ensure that their managerial strategies also serve to empower civil servants and create a culture of creativity. Municipal employees should be encouraged to take risks. One strategy to promote this cultural shift might involve positive evaluation in performance reviews, award and recognition programmes for individuals working on new practices and programmes, or the creation of innovation-oriented networks and mobility programmes to bring people together across organisational boundaries (OECD, 2017[3]). A risk management strategy can help ensure the success of an innovation initiative by stating what the initiative is trying to achieve, whether it is changing an established practice or introducing a new solution, and where its mandate lies.

Create or engage in networks that allow learning

Similarly, collaboration and communication – both horizontally and vertically – may incentivise the generation of innovative ideas. Horizontally, new networks across departmental silos can bring specialists in different domains into discussion and encourage joint project implementation. Vertically, municipalities can implement systems of upward feedback and forums for interaction between policy makers and employees working in the field with constituents. Literature shows that innovative risk takers are often at the “fringes’’ of bureaucracy and these forms of collaborative networks can help to balance central authority and understanding of improvements needed in particular contexts (Sørensen and Torfing, 2011[18]).

The workplace culture has a large impact on employee motivation to innovate. There are some elements that could reinforce the workplace culture in cities to make it fit for innovation:

-

Create a learning environment – innovation cannot take place without learning, thus city authorities need to create an environment that is receptive to sharing ideas and discussions that allow for idea generation. For this purpose it may be useful to: formalise training and development plans; give recognition to employees who have developed new skills; evaluate the benefits of training; and formalise the process of knowledge and information sharing.

-

Promote a culture of trust – public employees need to perceive that there is trust in their abilities and decision making. This is the foundation for building strong teams and producing results. It is incumbent for a manager/supervisor to set the example and build trust in the workplace. Some key actions: protect the interests of all employees, develop the skills of staff, and listen and treat people with respect.

-

Encourage diversity in the workforce – fostering inclusiveness and diversity in the workplace is a way to develop an open-minded culture. Diversity can take many forms, from nationality and culture to gender and educational and socio-economic background. The recruitment process should be revised to attract people from different backgrounds.

-

Stimulate experimentation – any city that is looking to innovate will need to give its staff the freedom to try new things and fail. The most successful organisations are those that are unafraid of failure and prioritise learning, growing and development from those experiences.

Sources: Mroz, D. (2013[19]), How to Invigorate Innovation in a Stagnant Organization, https://www.wired.com/insights/2013/10/how-to-invigorate-innovation-in-a-stagnant-organization; OECD (2011[15]), Public Servants as Partners for Growth: Toward a Stronger, Leaner and More Equitable Workforce, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264166707-en.

copy the linklink copied!Data management capability

Produce and use data for decision making

When a city provides greater access to and makes better use of public data, it contributes to economic development and growth because it allows the creation of value. Cities are an important user, but also a key source of data. “Data-driven innovation is the use of data and analytics to improve or foster new products, processes, organisational methods and markets” (Martin et al., n.d.[20]). By making data regarding numerous aspects of urban life widely and freely available, cities can enable competition to flourish as entrepreneurial citizens create new solutions that bring down the marginal costs and inefficiencies of urban services (Cohen, Almirall and Chesbrough, 2016[13]). Data help cities to balance what citizens perceive on service delivery and quality of life.

The OECD’s Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) has established a four-phase typology for the use of data and information. It consists of: 1) sourcing – the origin of data, information and knowledge; 2) exploiting – preparing information and data to be used to meet organisational challenges; 3) sharing – the information and data to support decision making elsewhere in the city; and 4) advancing – learning and generating knowledge from the organisation’s own experience (OECD, 2015[21]; 2017[3]). Considering data and technological innovation capacities through this lens can help municipalities improve their internal operations and enable citizen innovation.

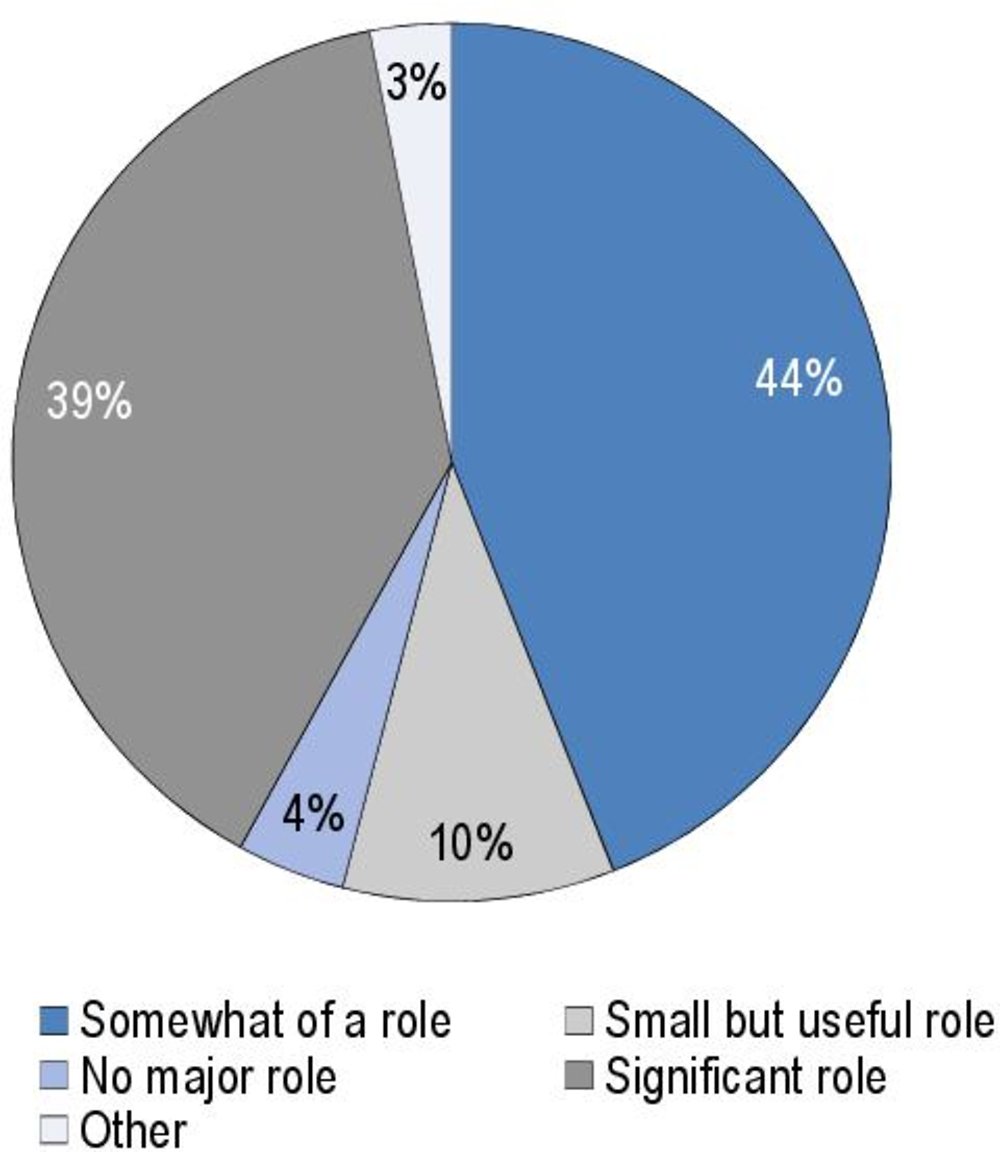

Effectively using data is important to strengthen cities’ capacity to innovate. According to the survey results, data play a significant or somewhat significant role in decision making and policy making in 85% of the cities (Figure 2.23). Many cities have placed digital technologies and improved use of data at the heart of their innovation strategies (Box 2.7).

Cities need to consolidate the practice of evidence-based policy making. Surprisingly for some cities, the importance of data in policy making and innovation work is not that evident.

-

Chelsea, MA (United States) has recently launched an open data portal to further increase its effectiveness and accountability. The portal offers information on property values, demographics, crime and expenditures that is being employed for operational performance and citizen engagement. The city acknowledges the need to equip city administration staff with the ability to manage and analyse data.

-

Chattanooga, TN (United States) has automated its data collection, cleaning and posting to reduce the barrier of entry for data-driven decisions. This has made for a more sustainable data programme and makes data more accessible. Now the city’s priority is data maintenance.

-

Cincinnati, OH (United States) developed a data analytics infrastructure, including a robust central data warehouse, to facilitate standardised, quality, up-to-date data analysis and publication.

-

Chicago, IL (United States) has developed several innovative initiatives seeking to harness the power of data. One of these is Chideas.org, which enables the city to elicit new ideas from external sources. Another is WindyGrid, an internal system that brings together siloed information to foster co-ordination across departments and support data analysis. The city’s biggest data-related challenge is developing the skills and capacity to conduct data analysis.

-

Paris (France) has made considerable investments in boosting its data capacity. Between 2014 and 2020 the municipality plans to invest EUR 1 billion in smart city technologies, such as the Internet of Things, that will allow it to harvest real-time information about its service delivery. The city has also created a chief data officer role tasked with mainstreaming data analysis throughout the municipality. To gather and analyse a wider range of data, it has cultivated multiple partnerships with public and private actors, such as Etalab. The city has also created a centralised data platform (opendata.paris.fr) to allow citizens to boost their innovations using publicly available information. However, work on data repositories and training of civil servants to make them more aware of the importance of data needs to be enhanced.

-

Tulsa, OK (United States) created the Urban Data Pioneers programme to improve the use of data throughout the city. By putting subject-matter experts – from inside and outside city hall – together in teams, the programme promotes learning data analysis techniques and informs the mayor’s team with analysis of data that leads to policy.

-

Wellington (New Zealand) has developed a data governance structure that allows the city to deploy the Internet of Things and enable its field staff to collect data. The data are shared with constituents to engage them in developing solutions to meet the citizens’ needs. The city’s modulation and standards approach has allowed it to work across multiple jurisdictions, cities and levels of government and with non-governmental organisations.

Source: Answers to Question 4.6 “Is there anything more you would like to tell us about data, communications or other tools your city uses in relation to innovation?” of the OECD/Bloomberg Survey on Innovation Capacity in Cities 2018. For Paris: https://www.paris.fr/services-et-infos-pratiques/innovation-et-recherche.

Cities need to improve their data management capability

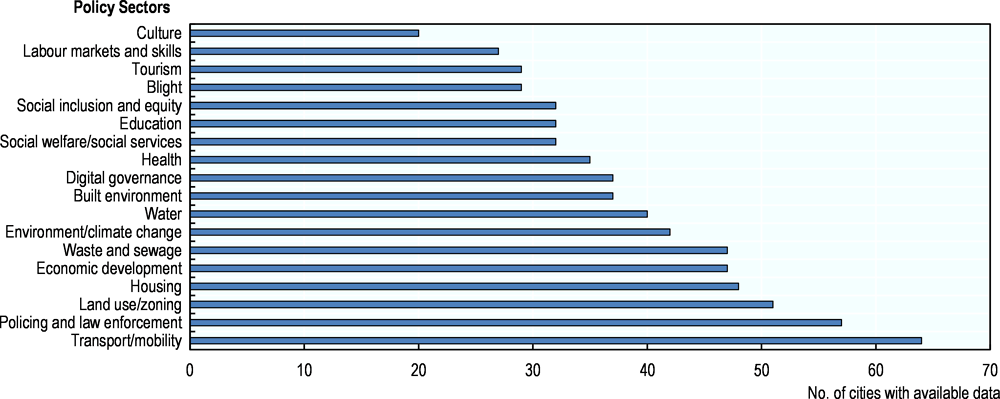

Making data actionable remains a concern for cities. Cities produce a large amount of data, and these data have the potential to improve the way cities operate. However, survey results show that data availability by policy sector remains uneven (Figure 2.24). Cities collect more data on areas such as transport (64%), policing and law enforcement (57%), land use/zoning (51%), and housing (47%). Cities collect less data on areas such as social welfare and inclusion (32%), blight (29%), tourism (29%), and culture (20%). This is likely due to the differing natures of these policy sectors, since law enforcement and transportation are more easily quantified according to statistical metrics than cultural work, which is likely to produce qualitative assessments.

Some cities reported being in the early stages of improving their methods of data collection and analysis (Box 2.8). Others reported that they needed to consolidate the practice of evidence-based policy making.

-

Houston, TX (United States) is expanding its in-house resources to make data available for external consumption and to use external data internally.

-

Chelsea, MA (United States) has recently launched an open data portal and is working to build staff capacity to analyse data and mainstream data analysis into its daily work.

-

Inverness (United Kingdom) is raising awareness among its staff on the importance of data production and use. Currently, data are typically stored, retrieved and analysed under the initiative of a project leader or because of reporting needs.

-

Seattle, WA (United States) is working to build its municipal staff’s comfort with data and its importance for evidence-based policy in order to maintain focus on desired outcomes.

Source: Answers to Question 4.6 “Is there anything more you would like to tell us about data, communications or other tools your city uses in relation to innovation?” from the OECD/Bloomberg Survey of Innovation Capacity in Cities 2018.

An increased reliance on data tends to increase cities’ familiarity with innovation practices

The use of data to enable policy work was the most clearly correlated with a city’s familiarity with innovation work of all the variables considered in the survey. Strong linear correlation between the amount of data used by cities in their decision making and their familiarity with the eight categories of innovation work can be seen in Figure 2.25.

Notably, the two domains of innovation work, apart from data analytics, that most strongly correlated with a city’s level of data use were “engaging residents in new ways” and “human-centred design”. Cities with a high level of data showed greater average familiarity with innovative approaches engaging residents than cities that reported that data played no role in their decisions. Similarly, cities with consistent use of data were more familiar with human-centred design than cities lacking data in their operations.

Municipalities that use data consistently demonstrate improved capacity to rethink their challenges holistically and to tackle them. The results of the survey show that thorough use of data analysis can foster innovation at all stages of the policy cycle. Cities with a high-level use of data seem to be more familiar with innovation practices. The cross-cutting benefits of consistent use of data become even more apparent when considering that cities with thorough data also had twice the average familiarity with organisational change than cities without any data capacity. They are more capable of engaging externally with constituents as well as of reorganising internally to improve the operations of their bureaucracies. For example, Los Angeles (CA) focused on using data to increase resident engagement. As a result, the city was able to create an open data portal that now greets visitors with an invitation to “find the data useful for you”, while its GeoHub online platform empowers residents with quick access to mapped sets of open data related to health, safety, schools and more. As a top performing city in the “What Works Cities Certification” programme, it demonstrates what “good” looks like in terms of gathering and using data to improve resident engagement.

Create collaborative partnerships with external actors to strengthen data management capability

In order to keep pace with rapid technological advancement and to improve their data collection capability, analysis and sharing, most cities build partnerships outside the public sector. These partnerships also help cities overcome knowledge and skill gaps with private developers and researchers. Indeed, co-operation within the public sector allows cities to access resources and competences they do not have, long-term innovation perspectives, idea generation activities, and, in some cases, share the risks inherent to innovation (Alves et al., 2007[1]). Partnerships are not for cities to outsource some of their capacities, but to help them build their capacity.

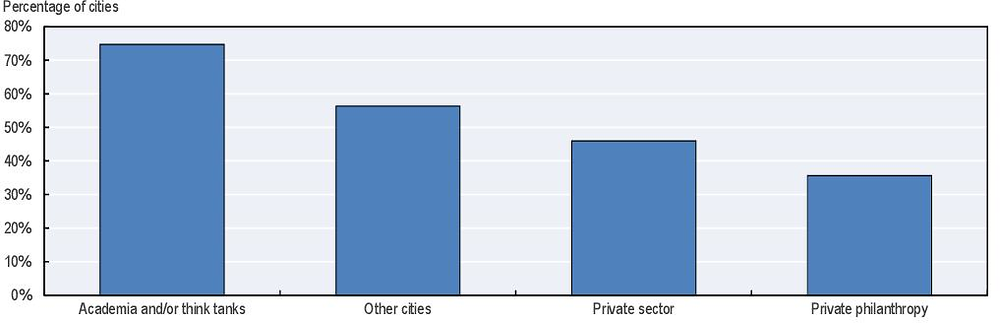

Survey results show that 75% of cities that reported that data play at least some role in their work have built relationships with academia and think tanks to gather and analyse data (Figure 2.26). A total of 56% of surveyed cities that said data play a major role in policy making have also reported that they have built partnerships with other cities. This could be because cities need to create economies of scale as data management may be expensive and complex, thus creating partnerships with other cities is a way to share costs, particularly if they belong to the same metropolitan area. Forming partnerships could be a win-win situation for large and small cities as it increases efficiency and accuracy.

-

Bilbao (Spain) has partnered with private companies, academic institutions, think tanks and cities in other countries through informal meetings, formal co-operation agreements and the European co-funded projects (Interreg, Horizon 2020, Urbact) to improve data management capability.

-

Stockholm (Sweden) created Digital Demo Stockholm as a long-term collaboration partnership to conduct research for innovation. The partnership includes the city of Stockholm, the region of Stockholm, the Royal Institute of Technology and leading corporations (Ericsson, Scania, Skanska, ABB, Telia, etc.). Their aim is to become the world’s smartest city by 2040, finding solutions to improve citizens’ lives and creating the best climate for entrepreneurs. The partnership works on four areas: 1) access to clean water; 2) digital locks for the elderly; 3) technology for equal opportunity; and 4) efficient healthcare. In addition, Stockholm has recently moved from having its own statistical unit to partnering with SWECO, a statistical consulting company that now delivers all major statistics and analyses data on behalf of the city.

-

Arlington, TX (United States) partnered with online retailer Amazon to allow residents to ask city-related questions to Alexa-enabled devices. Alexa is a virtual assistant developed by Amazon that is capable of responding to voice requests. Alexa is connected to the city’s open data and can answer questions ranging from “what is my garbage pickup day?” to “where is my voting location?”.

-

Louisville, KY (United States) developed the Open Government Coalition to help other cities take advantage of private sector data-sharing agreements and deploy built-in solutions to make data actionable. It has partnerships with the University of Pennsylvania to analyse the data and provide additional insights for the Vision Zero project which promotes a different way to approach traffic safety.

-

Sao Paulo (Brazil) has created partnerships with the Inter-American Development Bank and other cities to develop big data capability.

-

Chicago, IL (United States) – Tech Plan has helped the city build partnerships across sectors to drive innovation. For instance, the project called the Array of Things (AoT) is a collaborative effort among leading scientists, universities, local governments and communities to collect real-time data on urban environment, infrastructure, and activity for research and public use. The AoT measures factors that impact liveability in cities, such as climate, air quality and noise.

-

Kansas City, KS (United States) is placing significant emphasis on the expanded use of geospatial analysis and mapping tools to improve its efficiency. Thus, the city has implemented an enterprise agreement with ESRI, a mapping company, to make the software available to anyone in the organisation.

Sources: OECD/Bloomberg Survey of Innovation Capacity in Cities 2018. For Stockholm, information complemented through the presentation of Gunnar Björkman during the webinar on “Accelerating Cities’ Innovation Capacity” on 12 June 2019. For Arlington (TX), information provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies. This city did not participate in the survey.

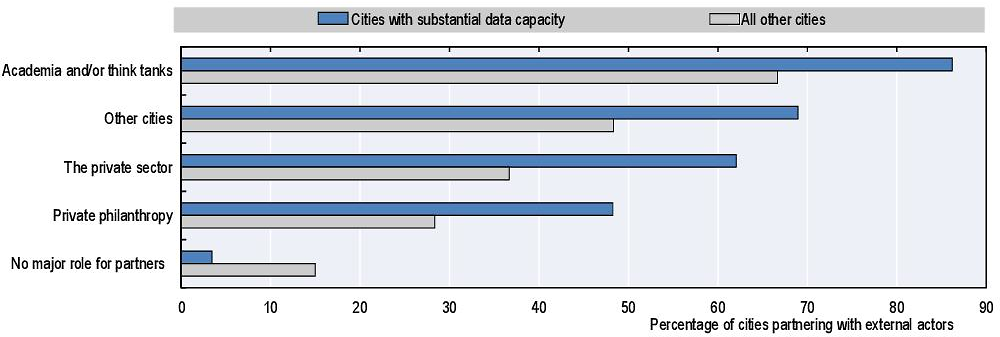

Academia and the private sector constituted the most common sectors for data-related partnerships in all responding municipalities. Survey results show the importance of building strong and diverse knowledge networks to enhance innovation capacity. Figure 2.27 shows how cities that reported using data thoroughly in their decision-making processes are far more likely to have partnerships with external data providers than all other cities. Only 3% of survey respondents claimed to use data consistently for innovation. In contrast, an overwhelming 86% of cities with strong data usage also reported having partnerships with academic institutions to help source and process their data.

The private sector was the domain with the largest percentage difference in partnerships between cities that consistently use data. Survey responses showed that 62% of cities that consistently use data have partnerships with the private sector, compared with 36% of all other municipalities that do. Private sector enterprises possess a great deal of data that could be of use informing policy makers. Moreover, there is the related issue that municipalities, when compared to the private sector, tend to have difficulty attracting the human capital needed to process these data. Both of these factors help explain why cities that establish partnerships with private sector firms may be more capable of incorporating data across their municipal operations.

However, cities should consider that private sector data and tech firms might seek to profit from their asymmetric information. Because firms often will not benefit financially from releasing their data and human capital publicly, the private sector is likely more reluctant than other sectors to engage in pro bono partnerships with municipalities. Therefore, economic interests might explain why municipalities have a greater likelihood of collaborating with academia than with the private sector (Kitchin, 2014[6]).

Foster the move to open data

A big question for many cities is how to exploit their data to optimise public management and service delivery. Data by themselves have no intrinsic value; it depends on how to extract the information (Martin et al., n.d.[20]). If implemented effectively, new smart infrastructure and the big data that it produces have the potential to improve local service delivery and efficiency, enable urban resilience, and cultivate a vibrant knowledge-based economy (Buck and While, 2015[7]). The open data movement is important for a couple of reasons. First, transparency. It is essential to let citizens know what data the government has – and how it is using it – so they can hold the right people accountable. Second, open data fosters greater interdepartmental collaboration and drives innovation through sharing data with third parties (Ende, n.d.[23]).

copy the linklink copied!Leveraging partnerships for innovation

Promote collaboration with a diverse set of stakeholders

Strengthening cities’ innovation capacity requires building partnerships with external stakeholders. Due to the complexity of contemporary decision making in the public sector and the economic, cultural and social dynamics, no level of government can govern without the collaboration of external stakeholders. Enhancing the innovation capacity of local governments may be possible by structuring better collaboration across disciplines and the establishment of governance innovation networks (Sørensen and Torfing, 2011[18]). External players could include the private sector, academic organisations, other local governments and citizens.

Innovation capacity also depends largely on how city administrations engage the private sector, the non-profit sector and citizens, as well as how they are made active players in the process of decision making and implementation. “The level of innovation in the public sector depends on how well it can manage collaboration, internally and externally, to create value, reduce barriers, and harness resources within co-operating organizations” (Wagner and Fain, 2017, p. 1210[24]). Collaboration between the public and private sectors has a greater potential for creating better and more effective public and private services and products (Setnikar Cankar and Petkovsek, 2013[25]).

The creativity of the local public sector may be bolstered by interacting with a multi-disciplinary environment where people from different professional and socio-economic backgrounds coexist and collaborate. A multi-disciplinary environment refers to organisations from different sectors and science and technology institutions. “The linked organizations combine multidisciplinary competences and localized complementary productive activities, integrating the diverse knowledge sets and skills …” (Alves et al., 2007, p. 30[1]) needed for new public products and services.

Ensuring the participation of a diverse array of constituents (and indirectly of competencies, skills and ideas) is also more likely to support and lead to successful innovation. This entails seeing diversity as equal opportunities by which people from different backgrounds, levels of income, gender, race, age, religion or belief, political views, and disability are able to participate in the policy-making process. Moreover, individuals have stronger incentives to engage in public policies that visibly and tangibly affect the environment in which they interact on a daily basis (Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers, 2015[8]).

Partnering with citizens for innovation

Cities give great importance to engaging with citizens

A majority of municipalities viewed community engagement as very important in developing their innovation capacity, whereas only 25% of cities claimed consulting firms and other partnerships were key to their innovation work. According to the survey results, municipalities place a much higher emphasis on engaging with community members and constituents than with external consultants. The widespread perception by municipalities that constituents represent valuable partners capable of contributing to innovative policy work can be seen in the fact that 80% of respondents have established partnerships with residents. Engaging civil society and non-profit organisations as partners in the design, production and delivery of services has the purpose of increasing users’ satisfaction and reducing operational costs in a context of fiscal constraint (OECD, 2011[26]).

In a context of increased budgetary pressure and growing demand for public services, user-centred collaborative approaches in service design and delivery (also referred to as “co-production”) can be a source of innovation. This is where citizens or service users design, commission, deliver or evaluate a public service in partnership with service professionals. This collaboration could lead to greater individual and community empowerment, increased user satisfaction, reduced production costs, and even new products and services.

-

Tulsa, OK (United States) has created a “Civic Innovation Fellowship” to convene six innovative Tulsans to deeply understand and propose solutions to long-standing civic challenges; the team works for six months and learns the basics of city government so it can make proposals to enhance citizen participation.

-

Atlanta, GA (United States) has a “Center for Civic Innovation” to find solutions to social inequality in the city by empowering residents to design local policy from the ground up. To support these efforts, the city makes sure that information about inequality and on the current interventions is readily available and accessible.

-

Peoria, IL (United States) developed a community engagement programme, Help Shape West Main, that focuses on building the innovation capacity of residents and other community stakeholders to foster the economic vitality of neighbourhoods. The programme is based on the premise that the city does not always have the resources to tackle community challenges alone, it needs the assistance of residents and stakeholders.

-

Reykjavik (Iceland) implemented the “My Neighbourhood” programme, which is a collaborative initiative between the city and citizens for prioritising and allocating funds for new, smaller scale projects and maintenance in the different districts.

-

Madrid (Spain) has implemented over 800 projects in areas such as social policy, environmental protection and health through projects defined in partnership with citizens via consultations, proposals and participatory budgeting.

Source: OECD/Bloomberg Survey on Innovation Capacity in Cities 2018.

Improving engagement with citizens may require organisational and operational changes

There are several mechanisms available to cities to improve their engagement with citizens in order to tailor public services to constituent needs, improve trust in government and generate a vibrant urban environment conducive to social innovation. One way of facilitating engagement with citizens for innovation is by tapping into new technologies (e.g. social media, mobile government or open data) to better align engagement with the rapid pace of policy making. While this option is not new, comparative analysis suggests that more can be done (OECD, 2016[27]).

-

Chattanooga, TN (United States) created a local “Enterprise Center”, a non-profit organisation, to establish itself as a hub of innovation and improve people’s lives through digital technology. The organisation helps manage the “innovation district” as a space for start-up entrepreneurs to work collaboratively. The centre also works to promote digital equity through programmes such as “Tech Goes Home”. It offers underprivileged community members skills, hardware and connectivity in order to close the digital divide. For more information see: www.theenterprisectr.org.

-

Curridabat (Costa Rica) implemented a mobile application called Yo Alcalde (I, Mayor) that empowers citizens to be a part of data generation. Through the application, citizens can report problems with garbage collection, traffic-related issues, etc. All data are geo-referenced and fed to the municipality’s Territorial Intelligence Centre. The city aims to use the application to generate and aggregate citizen demands and take evidence-based decisions. For more information see: www.curridabat.go.cr/yo-alcalde.

-

Paris (France) is using digital technology as a central axis of its participatory budgeting programme. Between 2014 and 2020, the city plans to allocate EUR 500 million to the programme. Residents from all backgrounds are invited to submit their proposals on line for how this money should be invested in their neighbourhoods. After the projects are developed and expanded by volunteers, citizens can then vote on line to decide which projects eventually receive public funding for implementation. Parisians can also track the implementation of participatory budgeting projects on line. For more information see: https://budgetparticipatif.paris.fr/bp.

-

Stockholm (Sweden) launched TechTensta, a digital project that seeks to motivate and engage young people to explore together and see the practical value of knowledge through technology. TechTensta contributes to raising knowledge about ICT for young people in Järva, a socially exposed area in north-western Stockholm with a high proportion of immigrants. TechTensta seeks to help young people in their personal development, abilities, initiatives and driving forces through mentoring. For more information see: www.digitaldemostockholm.com/en/demo-projects/techtensta.

Sources: Answer to Question 4.6 “Is there anything else you would like to tell us about data or other tools your city uses in relation to innovation?” from the OECD/Bloomberg Survey of Innovation Capacity in Cities 2018.

Another possibility is to engage agents (citizens or organisations) capable of acting as intermediaries between distinct organisations. These agents fulfil a variety of functions. They can support efforts to gather, develop, control and disseminate outside knowledge within distinct organisations, including community organisations. They can also play key roles as brokers that connect innovation seekers with municipalities providing the space and resources for collaborative innovation work to occur. Over the course of a project’s lifespan, intermediaries can be crucial in providing support by orchestrating technical or stakeholder knowledge and supporting implementation or commercialization (Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers, 2015[8]). This was the case of the city of Busan, in Korea, where the participation of the community and a few dedicated artists who acted as activists or facilitators for the regeneration of a village, were central to the successful regeneration of the district (Box 2.12).

In Busan Metropolitan City (Korea), the so-called Gamcheon Culture Village is an example of social innovation that led to the economic development of the district via culture. In the past, the region had a reputation as having fallen behind with its development under the name of Taegeukdo Village. At the end of the 20th century, Gamcheon region was gradually becoming a slum; people were leaving the town due to new city development and industrialisation, and the number of vacant houses was rapidly increasing.

In 2009, Gamcheon Culture Village began to transform itself through art projects and through a series of cultural projects which transformed the village. As a result, the village came to be known as Gamcheon Culture Village as small cafés and shops opened in the village. The village’s selection for the village art promotion project of the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism in 2009 was a key moment for Gamcheon Culture Village. Following the selection, artists and residents in the Busan area who lived in Gamcheon Culture Village collaborated to revitalise the region by harmonising the existing facilities as part of an urban reconstruction project. A few dedicated artists acted as activists or facilitators for the regeneration of the village. Residents were encouraged to participate early in the planning process through the implementation stage.

Source: OECD (2019[28]), The Governance of Land Use in Korea: Urban Regeneration, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/fae634b4-en.

Having staff dedicated to co-creation projects can serve to break down the barriers between the municipal administration and constituents. This approach also allows public officials a greater amount of discretionary autonomy, which is key in implementing the innovative and unorthodox solutions proposed by constituents.

Without robust, dedicated and flexible resources, collaborative initiatives risk fitting into the logic of austerity by foisting public services onto unpaid constituents rather than empowering constituents with new resources to innovate. Yet resource flexibility should not be equated with a complete lack of accountability. There is a need for qualitative and quantitative assessments of co-production efforts in order to better quantify the results they generate (Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers, 2015[8]).

Other “[i]mmediate strategies include the reduction of physical and informational barriers to participation, coupled with the enhancement of the capacity, skills and knowledge of citizens to be able to contribute meaningfully to policy deliberations and actions” (Kim, 2011, p. 89[29]). For that, the government has to increase opportunities for engagement; gain a better understanding of who participates; enhance the focus on evaluating the quality of outputs and outcomes (i.e. cost-benefit analysis); and broaden the scope and scale of engagement efforts.

OECD research suggests that there seems to be an imbalance between the resources (time, money and energy) that authorities invest in engaging with citizens and civil society organisations and the amount of attention they pay to evaluating the effectiveness and impact of such efforts (OECD, 2005[30]). Despite growing awareness of citizen engagement in boosting innovation, one of the main weaknesses is the lack of evaluation of the government’s action to enhance citizens’ participation in policy making. Cities still need to: evaluate, in a systematic way, the effectiveness of public participation exercises; and develop the tools and capacity to evaluate its performance in providing information, conducting consultation and engaging citizens in order to adapt to new requirements and changing conditions.

Collaboration with the private and non-profit sectors

Enhancing capacity in the local public administration requires new forms of governance that facilitate collaboration between the cities/municipalities and the private and non-profit sectors. Innovation can be developed and implemented through “innovation co-operation” (Setnikar Cankar and Petkovsek, 2013[25]). Cities may establish partnerships with private organisations for data management or even service delivery. However, new ways and modes of interacting with the public, business and non-profit organisations are needed. Possible partners for collaboration are private enterprises, research institutions, other public organisations, non-profit organisations and citizens as users. This collaboration could come at any stage of the innovation process. “When actors of different experiences, insights and ideas interact through processes in which ideas are circulated, challenged, transformed and expanded, the generation of ideas is accelerated and enriched” (Setnikar Cankar and Petkovsek, 2013, p. 1603[25]). Cities need to exchange ideas and resources within their organisational boundaries. And if they are to increase their capacity to innovate, they need to do so with external actors. Some actions cities can take to collaborate with external actors may include: administrative simplification and reduction of barriers arising from regulation and overly bureaucratic practices (Cunningham and Karakasidou, 2009[31]); and multi-sectoral and multidisciplinary networks that allow for openness and dynamic contact between individuals and teams from different organisations (Alves et al., 2007[1]). Several cities reported having created partnerships with external actors for innovation. Another organisational strategy cities have deployed to improve their collaborative initiatives has been to appoint a policy entrepreneur. These could be elected politicians, leaders of interest groups, or even non-governmental organisations or consultants who use their knowledge to propose solutions to emerging problems.

-

Athens (Greece) has included civil society in decision making, but it is expanding collaboration with the untapped capacity of the wider city by including universities, the private sector and philanthropic foundations.

-