1. SME and entrepreneurship policy in the Slovak Republic – overall assessment and recommendations

This chapter presents the overall assessment and recommendations of the OECD review of SME and entrepreneurship policy in the Slovak Republic. It summarises the key messages of the report. It covers SME and entrepreneurship performance, the business environment for SMEs and entrepreneurship, the strategic framework and delivery arrangements for policy, national SME and entrepreneurship policies and programmes, the local dimension of SME and entrepreneurship policy, SME digitalisation, and entrepreneurship for the Roma population.

The Slovak economy has a relatively large share of micro firms

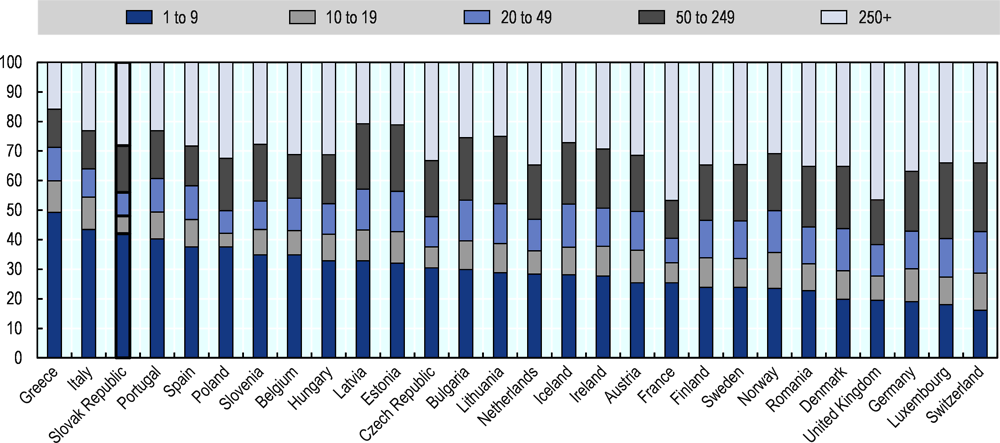

SMEs account for 99.9% of firms, 72% of jobs, and 58% of value added in the Slovak Republic. The share of micro firms is the largest among OECD countries. In 2017, 97% of firms in the Slovak Republic employed fewer than 10 employees, compared with an OECD average of 95%. For each employer enterprise, there are more than 2.5 non-employer firms, one of the highest shares in the OECD.

While the Slovak Republic has a high share of employment in micro firms, it has relatively few employees in firms in the 10-19 and 20-49 employment size bands, and employment in larger SMEs (50-249 employees) is low relative to other OECD countries (Figure 1.1). There is therefore a “missing middle” of firms of 10-249 employees in the Slovak Republic, which is instead relatively dominated by micro firms on the one hand, and large firms on the other.

In terms of output, micro firms in the Slovak Republic produce only 23% of value aded, relative to an employment share of 42%. This points to their relatively low productivity. It contrasts with the situation in some countries, notably Denmark, Luxembourg, France and the United Kingdom, where the average productivity of micro firms is not much lower than for their larger counterparts.

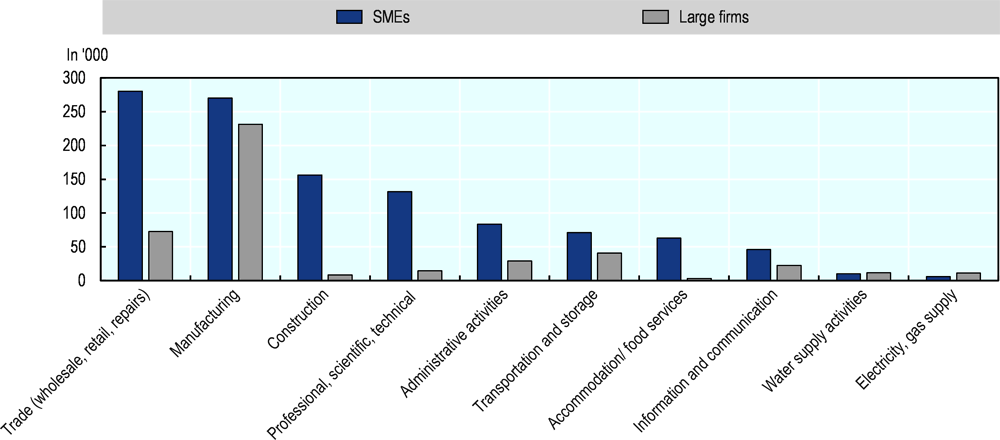

Manufacturing is the largest sector in the Slovak Republic, employing 500 000 employees, of which approximately 54% work in SMEs (Figure 1.2). However, the trade sector has the largest number of SME employees (280 000, or 80% of the sector’s total employment). Sectors with high shares of SME employees are the accommodation and food enterprises sector, which is almost exclusively composed by SMEs, which account for 95% of employment, followed by the construction sector, and professional, scientific, and technical services. There is an above average representation of SMEs in sectors particularly affected by the COVID-19 crisis, which include: transport manufacturing, construction, wholesale and retail trade, air transport, accommodation and food services, real estate, professional services, and other personal services.

The Slovak economy has very high business dynamism

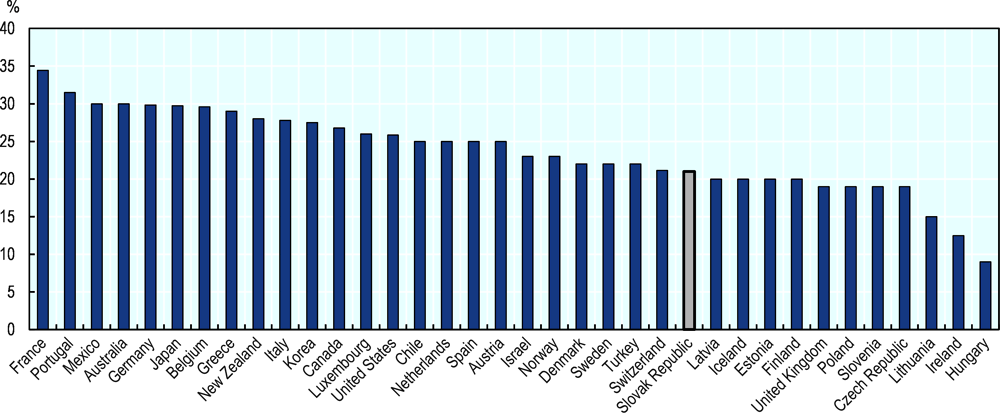

At the end of 2017, 13.8% of firms in the Slovak Republic had been created during that year. This new firms share is among the highest in OECD countries (Figure 1.3). High business creation is accompanied by a high share of enterprise deaths. In 2017, 11.1% of previously existing firms left the market. As a result, the Slovak Republic has one of the highest enterprise churn rates of OECD countries. The Slovak Republic also has a high share of medium-growth and high-growth enterprises; 13% of enterprises in industry in 2017, the third highest rate among OECD countries with comparable data. On the other hand, the new enterprise survival rate is low. Only approximately one quarter of start-ups were still operating in their 5th year in the Slovak Republic in 2017, one of the lowest new enterprise survival rates among OECD countries.

This very high business dynamism may stimulate productivity growth through reallocation of resources from less productive existing firms to more productive new firms, or from the introduction of innovations and creative ideas in start-ups. However, there may also be negative consequences – for example in terms lack of development of economies of scale through firm growth or limited investment in employee skill development.

SME productivity is low and stagnant or falling

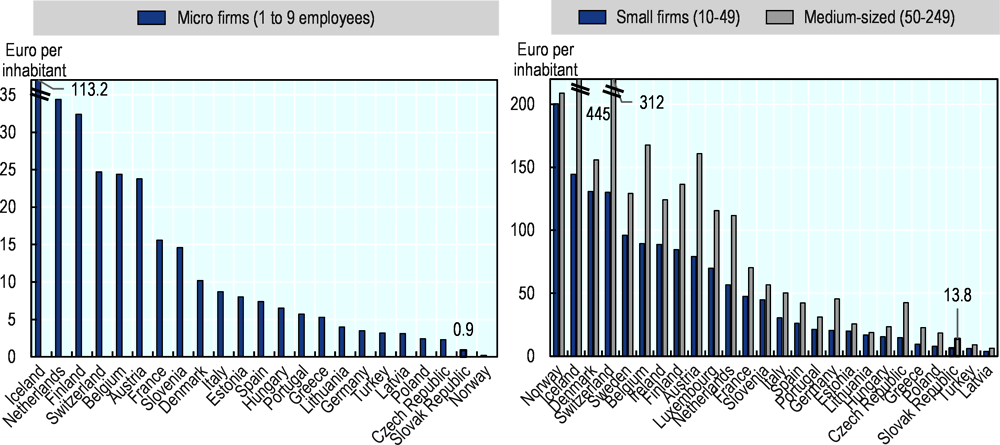

SME labour productivity is low in the Slovak Republic compared to most other OECD countries (Figure 1.4) Micro firms with less than 10 employees generate output of only EUR 13 000 EUR per person. Productivity almost doubles to EUR 24 000 for firms with 10 to 49 employees. Medium-sized firms’ productivity is higher, but also lags behind other OECD countries.

Furthermore, Slovak SME productivity has been stagnant or declining in recent years. SME productivity in the Slovak service sector fell by 18% from 2011 to 2017. SME productivity in manufacturing increased by only 6%, compared with an average increase of 42% in OECD countries. For firms with under 20 employees, productivity declined by almost 10% from 2010-2017, whereas it grew by 17% in medium-sized firms.

Causes of the poor productivity performance relate to the entry of less productive firms into the market, obstacles to growth of micro firms and untapped opportunities for SMEs to absorb technology.

Relatively few small firms export or innovate

Only 8% of Slovak Republic firms with between 10 and 49 employees export, compared with 14% across OECD countries, although the share of larger SMEs that export (50 to 249 employees) is close to the OECD average. Overall, SMEs generate only 15% of extra-European exports compared with an average of 29% in European Union countries as a whole.

Slovak SMEs also have relatively low R&D spending levels (Figure 1.5), although Slovak SME R&D spending has quadrupled over past decade, albeit from a very modest base. There is a particular R&D gap among medium-sized firms. Only 16% of medium-sized firms report that they engage in R&D spending on continuous basis compared with an EU average of approximately one-third.

Entrepreneurship rates are high

The Slovak Republic has one of the highest shares of self-employed people in the labour market among OECD countries. In addition, 12% of the adult population were starting or running a new business in 2018 (Total early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity), a high proportion by international standards (Figure 1.6). The Slovak Republic has a higher proportion of youth in entrepreneurship than most other OECD countries. Furthermore, more than half of adults declare that they possess the knowledge and skills to start, the third highest rate among surveyed OECD countries. However, a relatively high share of adults cite a scarcity of jobs as their motivation to start a business. Furthermore, women are only half as likely as men to be entrepreneurs, and their rate of business creation has fallen since 2011. In addition, the Slovak Republic has many family businesses facing the issue of how to organise business transfer to the second generation of family owners.

Policy recommendations

Take action to facilitate the process of business transition, including for family-owned businesses.

Promote policies that increase productivity in existing SMEs, especially among micro and very small firms and service sector SMEs.

Promote policies that support SMEs to become more active in foreign markets, including markets further afield than the European Union.

Consider the adoption of additional measures to stimulate innovation activities among SMEs, especially for medium-sized enterprises.

Improve the overall business environment to tackle the perception that entrepreneurship opportunities are relatively weak and that it is hard to start a business.

Adress the larger than average gap in entrepreneurship rates by gender for employer enterprises

Macro-economic conditions have been favourable but COVID-19 is having a severe impact on SMEs

Demand conditions and macro-economic stability have been favourable to SME growth and entrepreneurship in recent years. GDP grew continuously from 2009-18 at an average annual rate of over 3%. However, GDP contracted by some 6% in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite forceful public measures to contain the spread of the virus and mitigate the damage done to the economy.

Regulatory reforms need to be continued

The Slovak Republic ranked 45th among 190 economies in the World Bank “Ease of Doing Business” Index in 2020 and performs in line with many other OECD countries on overall regulatory performance indicators. An obligation to conduct regulatory impact assessments has been in place since 2010, and an SME Test was introduced in 2015. In 2018, the government adopted a whole-of-government policy for regulatory quality (the RIA 2020 Better Regulation Strategy).

However, there are also areas of business regulation that can be further strengthened. This includes business start-up regulations – the Slovak Republic ranks in only 118th place on the World Bank Doing Business indicators on Ease of Starting a Business. Furthermore, insolvency procedures take up to 4 years in the Slovak Republic, compared with an average of 2 years in the EU. In the case of SME access to public business support, a problem is “gold plating” of EU regulations, through which the government introduces additional requirements on the top of the EU requirements. Another issue is lack of stability in business regulation. Thus in 2018, 86% of SME owners declared that frequent amendments to legislation influenced the functioning and growth of their businesses.

The innovation system does not favour SME innovation

The Slovak Republic is classed as a “moderate innovator” in the European Innovation Scoreboard and ranks at the tail of OECD countries on innovation system measures. Areas for improvement include academic research performance, business investment in R&D, cooperation between public research and the private sector, and innovation within SMEs. Both lack of innovation spending and lack of business engagement with higher education institutions (HEIs) hold back commercialisation of research through SMEs and entrepreneurship.

SME development is hindered by skills shortages

As in other countries, Slovak SMEs face difficulties in obtaining skilled workers. Particular skills shortages relate to digital skills, electronics skills, science-based knowledge, administrative and management skills, and soft skills such as oral expression. Only one-quarter of adults have a university degree compared to an average of 37% across the OECD countries. There are also weaknesses in the matching of tertiary education curricula with business needs reflecting inflexibilities in HEI curricula and gaps in co-ordination with business. At vocational education level, the Slovak Republic operates a dual education system, with some 490 employers and 85 vocational schools participating in 2018. However, only two-thirds of Slovak small firms provided training in 2015, in contrast with 75% across the OECD (Figure 1.7). The formal education system provides little training in entrepreneurship.

Upgrading skills that can be used across a variety of tasks and jobs, promoting flexibility, teaching soft skills, and investing in increasing managerial capability will support productivity growth, innovation and internationalisation and help prepare the Slovak labour force for future automation challenges. Another potential source of talent is attracting returning migrants from the large Slovak diaspora living in other countries.

Some transport and digital infrastructure gaps need to be addressed

The quality of transport infrastructure varies across the country, with eastern and southern regions lagging behind. This has affected the extent to which different regions have been able to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), which is a potential driver for SME development. There are also some weaknesses in digital infrastructure. Only 13% of small firms and 17% of medium-sized firms had a connection where the download speed was at least 100 Mb/s in 2019, despite high adoption of cloud services among SMEs that ideally require higher download speed. For medium-sized firms, this is the lowest value among European countries. This is a constraint to SME digitalisation.

Relatively high social security payments may hinder small firm growth

Corporate taxes are low on average in the Slovak Republic (Figure 1.8). The standard corporate income tax rate in the Slovak Republic was 21% in 2020 for corporate taxpayers with taxable revenues above EUR 100 000. The rate is lower than in most OECD countries, where the average tax rate was 24% in 2018. In 2020, a reduced corporate income tax of 15% was introduced for all self-employed, entrepreneurs and corporations with income of less than EUR 100 000. Only a handful of countries have preferential rates for very small enterprises. A less distortive alternative could be a preferential tax rate for the first part of business income, and higher rate after a threshold.

An important feature of the Slovak business taxation system is a high share of revenues from social security contributions rather than corporate taxation. Social security contributions represent 44% of the tax receipts in the country, compared to about one-quarter in the OECD. This emphasis on taxing employment may constrain employment growth in SMEs.

The volume of R&D tax credits doubled between 2018 and 2020. In 2020 the tax credit available was double the R&D costs incurred. This is a significant incentive to SME R&D activity.

Equity finance and alternatives to debt finance are limited

Slovak entrepreneurs rely heavily on traditional means of financing, including savings, family funds, reinvested capital and bank loans. New forms of financing are underdeveloped and, at 0.0046% of GDP, the share of venture capital investments in GDP is among the lowest in the OECD, where venture capital investment is 0.06% of GDP on average (Figure 1.9). Tax incentives or credits for investors in start-ups and support for public-private venture capital funds could favour the growth of venture capital and business angel activity.

The spillovers from trade and foreign direct investment openness are currently limited

The Slovak economy is very open to exports and imports, which account for 90% of GDP. It is also highly integrated in global value chains through inward FDI, which employed more than half of the workers in the manufacturing sector in 2016, a larger share than any other OECD country. However, success in attracting FDI fails to translate into productivity spillovers for SMEs, reflecting limited supply linkages with domestic SMEs. For example, transport equipment, the main exporting industry in the Slovak Republic, adds only 40% of value locally. The relatively low skill and knowledge content of current FDI also limits opportunities for SME innovation spillovers.

Policy recommendations

Regulatory environment

Fully implement the RIA 2020 Strategy to improve the overall evaluation culture.

Streamline and centralise oversight and provide training faciltities to improve regulatory management practices.

All governmental proposals, including initiatives of members of parliament, should undergo the same legislative procedures and involve engagement with stakeholders, allowing enough time for discussion and collection of comments.

Review existing regulations and their usefulness on a systematic basis.

Adopt simplification procedures to decrease administrative burden by continuing to upgrade electronic documentation procedures.

Carefully monitor the impact of the recent modifications to the insolvency procedure and consider taking additional action to reduce the time required and cost of bankruptcy.

Limit gold-plating by ensuring all new legislation introduces only the necessary amount of regulations.

Education/skills

Establish skills councils to assess skills needs, ensure the representation of SMEs within them, and create a mechanism for SMEs to influence the curriculum to address skills shortages.

Minimise costs and barriers to participation of SMEs in vocational education and training programmes and boost the variety of course offerings to include digital skills training, management capabilities training, and improving soft skills such as communication.

Engage with diaspora communities and develop outreach programmes to attract back skilled Slovaks living abroad

Taxation

Carefully review possible unintended consequences of lower corporate tax rates for micro firms.

Reduce the tax incentive for self-employment by ensuring a similar tax burden from social security contributions on self-employed income as on employment income.

Assess the impact of the recent expansion of the R&D tax credit and adjust if necessary, increase awareness among SMEs of available R&D tax credits and ensure administrative clarity in the application and follow-up process for the tax credits.

SME access to finance

Establish investment readiness programmes to prepare entrepreneurs to access finance at all stages in the development of their firm.

Introduce tax incentives or exemptions for early stage equity investors to support the development of alternative forms of financing for innovative and growth potential SMEs and start-ups.

Improve financial education in the population with appropriate financial training initiatives.

Trade and foreign direct investment

Strengthen the emphasis of FDI attraction efforts on more knowledge- and skill-intensive investments with greater potential for domestic innovation spillovers.

Increase the capacity of domestic firms to participate in global value chain networks by ensuring the availability of a qualified workforce and strengthening management capabilities in SMEs.

There is no overarching SME and entrepreneurship policy document

The legal framework for SME and entrepreneurship policy in the Slovak Republic is set out in the Law on Supporting SMEs, adopted in 2017. This defines the beneficiaries – start-ups, existing micro, small and medium enterprises – and the types of support to be provided by the Ministry of Economy or its delegates, including a section on better regulation. However, there is no national SME and entrepreneurship policy strategy document setting out policy directions across different ministries, action areas and funding sources. The largest single source of SME and entrepreneurship support is the Operational Programme for Research and Innovation 2014-20 (OP R&I 2014-2020), which includes priority axes on “Enhancing the Competitiveness and Growth of SMEs” and “Developing Competitive SMEs in the Bratislava Region” with allocated spending of EUR 401 million for the 2014-20 period. However, this document does not cover regulatory improvements, entrepreneurship education or public procurement for SMEs and start-ups for example, or relevant SME and entrepreneurship actions in national thematic strategies such as the Digital Transformation Strategy and the Regional Development Strategy.

An overarching, cross-government SME and entrepreneurship strategy could improve co-ordination of policy action and implementation. It would lay out the vision, strategic objectives, quantifiable targets, policy pillars (e.g. access to finance, access to markets), related programme actions, responsible actors, institutional structure for implementation, and a monitoring and evaluation framework for SME and entrepreneurhsip policy. It would also clearly distinguish support to different kinds of SMEs (e.g. start-ups, micro-enterprises, traditional SMEs, innovative SMEs, growth-oriented SMEs) and to addressing different challenges.

SME and entrepreneurship policy lacks a lead unit, a cross-government co-ordination mechanism and an SME advisory council

A number of ministries are directly or indirectly involved in SME and entrepreneurship policy. The Ministry of Economy is the lead ministry. It is responsible for implementation of the SME Support Law and implementation of the OP R&I 2014-2020 through its support agencies, the Slovak Business Agency (SBA), the Slovak Investment and Trade Development Agency (SARIO), and the Slovak Innovation and Energy Agency (SIEA). The SBA also plays a role in developing policy by analysing barriers to SME and entrepreneurship development and proposing policies.

However, the Slovak Ministry of Economy does not have an SME and Entrepreneurship Policy Unit that could take responsibility for ensuring that policies affecting SMEs and entrepreneurship are adequately integrated across the various departments and sections of the ministry and in other ministries. A high-level inter-ministerial SME and entrepreneurship policy committee or council is also lacking. This could define the role of different ministries and the mechanisms by which policies and programmes will be co-ordinated. The Ministry of Economy has established a Working Group for Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe Principles, with the participation of the SBA and nine ministries, but this does co-ordinate SME and entrepreneurship more generally.

There is a high degree of consultation with SMEs on legislative and regulatory proposals in the Slovak Republic (OECD 2020c), which is one of the key activities of the SBA Better Regulation Centre. However, there is not a broader mechanism for gathering SME inputs on broader SME and entrepreneurship policy issues. A formal SME Advisory Council could play this role.

A policy portfolio examination would help assess the mix of spending

It is not straightforward for policy decision makers in the Slovak Republic to assess the distribution of SME and entrepreneurship policy spending by main policy area (e.g. entrepreneurship and business management training, access to finance, market expansion, innovation, etc.) and target populations (e.g. potential and nascent entrepreneurs, new start-ups, micro-enterprises, innovative SMEs, high-growth firms, etc.). Although much programme data is provided by the Antimonopoly Office and the SBA annual reports, the information is not presented by area of policy intervention. A policy portfolio accounting approach could be introduced to present and monitor government SME and entrepreneurship policy expenditures, activities and impacts by policy type and target group.

Use of business identification number information could support evaluation

The Slovak Government has made various arrangements for the monitoring and evaluation of SME and entrepreneurship policies. For example, the OP R&I 2014-20 identifies output-related key performance indicators and targets for annual reporting, including numbers of SMEs supported by different programmes, as well as macro outcome indicators such as employment, value added, SME exports and new firm survival rates. However, the Slovak Republic is less developed in the conduct of formal impact evaluations. The SME Support Law stipulates that applicants to each support programme must provide their business identification number and the Central Register for the Registration and Monitoring of de Minimis Aid records data on the value of support provided. Although not designed for this purpose at the outset, these data could be used as a tool for impact evaluation of programmes and as a tool to support policy makers in guiding SMEs to relevant programme supports given their pathway of programme use.

A connecting hub would strengthen the policy delivery system

Several organisations deliver business support to SMEs and start-ups. Key agencies for access to finance are the Slovak Guarantee and Development Bank (SGDB) (direct loans, guarantee products, micro-credit, venture capital), EXIMBANK (export credits, guarantee, and insurance products), and the SBA (micro-credits, venture capital investments). Business advice is provided by the SBA, the Slovak Investment and Trade Development Agency (SARIO) and the Slovak Innovation and Energy Agency (SIEA), but business advice centres are also operated by the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport, the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, and the Europe Enterprise Network. Co-ordination of business support is therefore an issue, including securing awareness of the different sources of business support among SMEs and entrepreneurs and ensuring that appropriate cross-referrals are made to clients from one organisation to another.

The SBA has set up National Business Centres in the eight regions of the country as an entry point for new entrepreneurs and SMEs, and there is some evidence of collaboration among some of the delivery actors. Furthermore, a proposal has been made to create a “Connecting Hub” in the start-up support ecosystem to act as an umbrella and a service to the different business support organisations. This would be a useful addition to the policy delivery arrangements. It would provide brokering of links with clients and across organisations as well as joint resources. The development of such a hub could be undertaken in co-ordination with the proposal for the establishment of a Digital Innovation Hub in the Digital Transformation Strategy to provide a support ecosystem to build the digital capacity of businesses. Futhermore, there is not a comprehensive, integrated and interactive web portal showing SME supports by stage of entrepreneurship/SME development and organisational provider, as is common in many OECD countries. The administrative requirements in applications for programme support could also be simplified in some cases.

Policy recommendations

Develop a national SME and entrepreneurship development strategy setting out policy objectives, targets, strategic pillars addressing the major challenges facing new entrepreneurs and existing SMEs, tailored approaches to fostering start-ups and enterprise scaling-up, and a monitoring and evaluation framework.

Establish a higher-level inter-ministerial council to oversee development and implementation of a national policy to support SME and entrepreneurship development.

Create an SME and Entrepreneurship Policy Unit in the Ministry of Economy with responsibility for co-ordinating policy development and measures among other relevant ministries and agencies.

Establish a higher level inter-ministerial Council on SME and Entrepreneurship Development.

Establish an SME Advisory Committee or Council including SMEs and entrepreneurs and their representative organisations, SME support organisations, and independent experts to provide policy input to the Minister of Economy and the higher level inter-ministerial Council on SME and Entrepreneurship Development.

Formulate a regularised public-private policy dialogue mechanism inclusive of SMEs and entrepreneurs that expands beyond the issue of better regulation.

Adopt a policy portfolio approach towards the management and evaluation of SME and entrepreneurship policy and support across state ministries and agencies, identifying policy expenditures and impacts by type of policy intervention and type of SME and entrepreneurship target group.

Establish connecting hubs in the entrepreneurship support ecosystem to bring together the various organisations offering support to SMEs and start-ups.

Design and publish an integrated, and interactive SME and entrepreneurship policy web portal to inform SMEs and entrepreneurs about support possibilities.

A business diagnostic tool and client management approach would strengthen business development services

The SBA is the main agency providing publicly-supported business development services for SMEs and entrepreneurship in the Slovak Republic. It implements a range of advisory and consulting programmes. This includes the Acceleration, Incubation, Internship, and Growth programmes delivered by the National Business Centres in each region. It also operates a start-up support scheme, a family business support scheme, a national project on SME internationalisation and supports the European Enterprise Network.

SMEs and entrepreneurs obtain support by responding to calls for participation in the various programmes. This puts the onus on the firms to identify and apply for the support most relevant for them. Introduction of an online business diagnostic tool could be made available for firms that wish to use it, with the benefits of increasing awareness of business development services among SMEs and entrepreneurs, increasing their understanding of areas for improvement and helping to orient them to the right services. In addition, an approach based on client management of a portfolio of companies identified for their growth potential or other characteristics (such as entrepreneurs from disadvantaged groups, SMEs in regional clusters or national priority sectors) would also increase policy targeting and effectiveness.

SME innovation support should include actions to strengthen university-SME links

The Slovak Innovation and Energy Agency (SIEA) plays a key role in directing resources from the OP R&I 2014-20 and the Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation of the Slovak Republic (RIS3 SK) to SME innovation. Priority Axes 3 and 4 of the OP R&I allocated EUR 357 million for SME innovation and competitiveness projects up to the end of 2018, focused on technology transfers, product and process innovations by SMEs and national projects for the business environment. These schemes have been well run and are met with significant interest by potential applicants. SIEA also supports creative vouchers for SMEs and innovation workshops and mentoring for entrepreneurs. However, there has been little support to stimulate various forms of university engagement with SME innovation.

Internationalisation programmes are at a basic level

A number of State agencies support SMEs with exporting, international technology transfer, and participation in global value chains. EXIMBANKA, the export credit agency, offers banking, guarantees and insurance products and consulting services to Slovak companies regardless of their size. However, it cannot support companies that are less than three years old, i.e. potential “born globals”. SARIO maintains a portal providing comprehensive information on state support for exporters, and offers a range of supports to assist companies to export and link with foreign direct investors. This includes support for participation in events, capacity building in companies, support through Trade Points in Slovak regions, and support for use of e-commerce tools. The SBA provides business advisory services to support SMEs to internationalise. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Affairs also operates a ‘Business Centre’ and supports the internationalisation of businesses through the network of Slovak embassies.

Overall, the services are of a relatively basic level and some more sophisticated and intense supports could be added. Furthermore, both the links among the different supports and organisations and the management of client relations could be strengthened. More impact could be obtained through a more focused approach built around developing clusters or supporting supply chain development by providing services to groups of SMEs working to target jointly new markets.

Entrepreneurship training and skills programmes lack a co-ordinated approach

Various business associations support entrepreneurship skills development in the general population. For example, the Entrepreneurs Association of Slovakia is co-operating with the SBA on supporting entrepreneurship education. Similarly, the SIEA supports a number of activities promoting innovation and entrepreneurship, including innovation prizes for students. However, the support is dominated by ad hoc projects delivered across a number of different various organisations and there is an absence of a clear nationwide strategy and coordinated approach to entrepreneurship education and training.

New sector skills councils and changes to the dual training system are strengthening SME skills

The Operational Programme for Human Resources (OP HR), managed by the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family, is the main source of financing for programmes that help upgrade skills and address skills gaps for SMEs. Recent strengthening of the skills policy includes the establishment of 24 sector skills councils, which mobilise representatives of ministries, regions and business federations in making skills needs assessments which can be used to stimulate the supply of appropriate training for SMEs. In addition, improvements have been made to the dual training system to increase the participation of SMEs, including simplified administrative requirements for participating firms, an increased share of practical training, the possibility to undertake practical training in other certified employers, direct payments (complementing tax exemptions) to employers providing practical training, increased funding to VET schools, and the possibility for employers to increase the student payment to above the minimum wage to attract more students. However, more could be done to increase the portability of training qualifications across employers, including through increased flexibility of apprenticeship schemes and further development of the national qualification system. It is also important to ensure that the outputs of the sectoral skills councils are fed into improved training programmes.

Access to finance programmes are now supporting a wider range of instruments

Since 2016, the Government has increased the emphasis on loan guarantees and risk capital relative to grant finance in its access to finance support for SMEs and start-ups. This helps to increase the range of finance options available and the efficiency and effectiveness of support. The Slovak Guarantee and Development Bank (SGDB) now provides substantial loan guarantees for companies. It had an outstanding guarantee portfolio in 2018 of EUR 78.4 million, guaranteeing up to 55% of loan values. The SGDB is also a significant player in micro-finance support, with a total outstanding micro loan portfolio of EUR 303 million at the end of 2018, and the SBA made microloans of EUR 9.6 million between 2013 and 2018. However, the Government could seek some rationalisation in the number of venture capital and equity funds it supports in order to ensure that each fund has sufficient scale to manage efficiently and professionally. For example, Slovak Investment Holding (SIH), a subsidiary of SGDB, made only three new investments in 2018, for a value of EUR 0.45 million, and Innovation and Technology Fund and Eterus Capital also have small deal flows.

The Office for Public Procurement promotes SME participation

The Office for Public Procurement is the central State body with oversight of public procurement. It monitors procurement procedures across government for legal compliance, provides training and guidance to the various contracting authorities, including on how to facilitate SME access to procurement, and offers advisory services to SMEs interested in tendering. In compliance with the EU directive on public procurement of 2014, the procedure has several features that facilitate SME participation, for example the practice of digitalising most of the application process and breaking large contracts into smaller lots. Several procedures, such as the low value contract procedure, were also simplified in recent years. Possibly as a result, SMEs increasingly participate in public procurement, in terms of the number and value of contracts. In 2018, 94.3% of public procurement contracts and 62.7% of contract values were awarded to SMEs. However, it is estimated that there are 3 000 contracting authorities in total, many operating at the regional and municipal level. This may adversely affect the level of professionalisation in some instances. The procurement office could therefore encourage more joint public procurement tenders on a voluntary basis, introduce a certification system to those contracting authorities assessed as following appropriate procedures, and increase the standardisation of tendering documents and procedures. Furthermore, tendering processes in the Slovak Republic often select winner bidders on a price-only basis and the procurement office could encourage the inclusion of some qualitative criteria.

There is scope for more dedicated entrepreneurship programmes for women and youth

There are relatively few entrepreneurship support programmes in the Slovak Republic that are specifically targeted to population groups with special needs and barriers, aside from the mainstream programme of start-up grants for the unemployed.

A small number of dedicated and tailored programmes for female entrepreneurship have recently been launched but more could be done. For example, the SBA is participating in an international project to support new women business angels and runs an annual Woman Entrepreneur of Slovakia contest to promote a positive image of female entrepreneurship. It also conducts targeted outreach to attract women entrepreneurs to incubator and entrepreneurship training programmes, although the programmes themselves are not typically tailored to the needs of women entrepreneurs. The gap in tailored advice could be filled by strengthening entrepreneurship networks and peer-learning opportunities for women, particularly outside of Bratislava.

There is also scope to create a stronger offer of support for young people interested in starting a business. Most of the current support is part of entrepreneurship education in the formal education system. This is complemented with more hands-on entrepreneurship training offered by non-governmental organisations (e.g. Young Entrepreneurs Association of Slovakia) and on university-based incubators. While often high quality offers, these initiatives tend to be located only in large cities, or near universities.

Policy recommendations

Business development services

Consider introducing an online business autodiagnostic tool to help increase SME awareness of available business development services and orient them to the right support.

Introduce a client management approach to business development services to identify and monitor support impacts on a portfolio of companies identified for their growth potential or other characteristics (such as entrepreneurs from disadvantaged groups, SMEs in regional clusters or national priority sectors).

Innovation support

Strengthen innovation support provided by universities to SMEs, for instance by expanding the Support of Research and Development programme, including outside of the capital region.

Make the R&D tax credit more SME-friendly by simplifying the administrative procedures and introducing specific provisions for SMEs and start-ups.

Internationalisation programmes

Access to finance programmes

Change programme entry criteria to enable Eximbanka to provide financial support to companies on the market for less than three years.

Scale up the activities of the Slovak Investment Holding, especially its equity and quasi-equity operations.

Select a qualified fund manager for the activities of the Central Europe Fund of Funds overseen by the asset management subsidiary of the Slovak Guarantee and Development Bank.

Rationalise public venture capital and private equity funds.

Stronger SMEs and entrepreneurship are needed to drive transition in regions lagging economically

There are major regional income and employment inequalities between Bratislava, and to a lesser extent the whole of the west of the Slovak Republic, and the centre and east of the country. An important cause of these inequalities has been regional structural economic changes, in terms of industrial decline in Košice, Žilina, Trenčín, Prešov and reductions in the agricultural workforce in Nitra, Banská Bystrica and Košice. Where there are strong SMEs and healthy entrepreneurship, regions can respond more effectively to declines in traditional specialisations, since new and small firm development generates jobs in new sectors and transforming existing sectors towards niche activities aimed at growing parts of the market. The problem to be addressed in the Slovak Republic, however, as in many other OECD countries, is that small business and entrepreneurship activity is currently weak in those regions with the greatest structural challenges and hence the greatest need for SMEs and entrepreneurship.

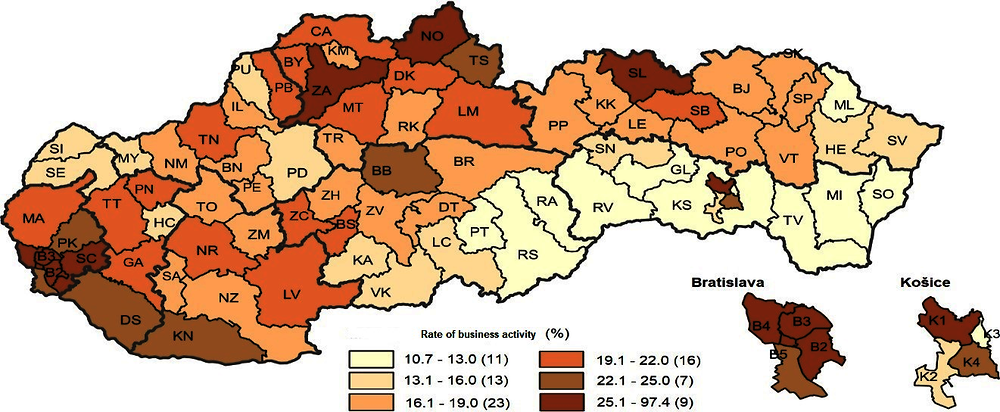

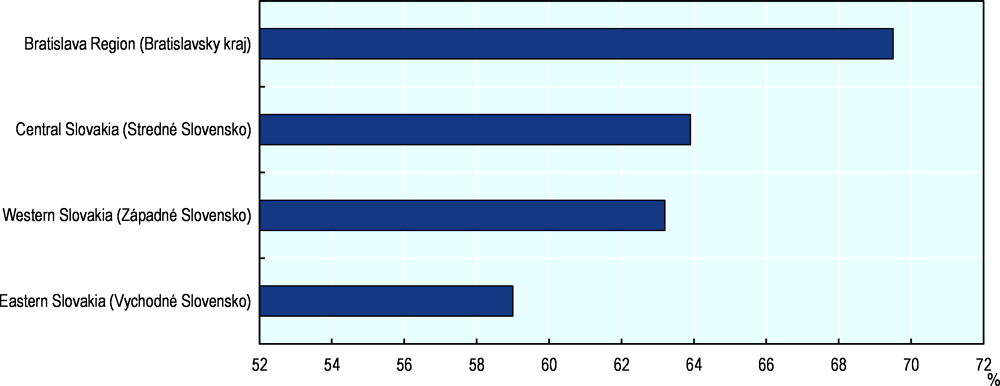

At the regional level, the stock of active SMEs per 10 000 inhabitants in Bratislava is more than three times than that in the region of Košice as well as outstripping all the other regions. At local level, there is a broad east-west gradation in the share of SMEs, roughly the mirror image of the prosperity of the local areas, as shown in Figure 1.10.

Underlying these differences, are important east-west differences in entrepreneurial attitudes, capabilities and aspirations, as summarised in the Regional Entrepreneurship Development Index (Figure 1.11).

Overall, there is a need for a set of regional level actions that can strengthen conditions for entrepreneurship and SME development throughout the country. Clearly there is a priority to improve SME and entrepreneurship performance in lagging regions, but it is also important not to hold back development in the stronger areas of the country, which face different kinds of constraints. Bratislava has developed into a secondary European hub for the technology sector and has strong potential as a motor for the Slovak economy, but is facing constraints in talent generation and retention in the face of international competition. The city of Košice is also starting to emerge as a second national entrepreneurial hub, with new co-working spaces opening up and new market developments, and is likely to face some of the same issues as Bratislava. Policy therefore needs to identify and respond to region-specific constraints to SME and entrepreneurship development in different regions of the country. This can be supported by assessment of SME and entrepreneurship development issues in the country’s regional smart specialisation strategies.

Gaps in finance, advice and support infrastructure need to be addressed

One of the requirements to improve start-up performance and SME development in weaker regions is to ensure that public support for access to finance, access to business advice, and access to an infrastructure of co-working spaces, business incubators and scale-up office space is evenly provided across the country and covers all regions. The regional innovation infrastructure and the “institutional thickness” of intermediary organisations needs to be strengthened, particularly outside of Bratislava, where the number and quality of incubation centres, counselling centres, enterprises with venture capital, and technological centres and parks is relatively limited.

Regional universities can play a greater role in supporting SMEs and entrepreneurship

Cultural barriers affecting attitudes to entrepreneurship are having adverse impacts on business start-up rates and SME growth rates in the poorer regions of the Slovak Republic. This is combined with a lack of start-up skills in the population. Regional universities can play a greater role in building entrepreneurial attitudes and skills among young people by offering high-quality entrepreneurship education and providing start-up support for graduates, such as co-working spaces. There is also scope for the regional universities to strengthen their collaboration with local SMEs on SME innovation projects, for example through consulting and internships.

Cluster organisations can be anchors for regional entrepreneurial ecosystem development

A number of promising regional industry cluster initiatives have emerged from the bottom up in the Slovak Republic and could become platforms for developing stronger regional entrepreneurial ecosystems. There are currently 16 certified cluster initiatives, such as ‘IT Valley’ in Košice, the ‘Slovak Automotive Cluster’ in Trnava, the ‘Electrotechnical Cluster’ in Galanta, and the ‘Slovak Plastic Cluster’ in Nitra. These fledgling regional clusters need policy support to develop coherent management and strategies and to undertake operational activities. They could become a focus of local initiatives for SME and entrepreneurship development such as sector-specific skills and innovation projects involving groups of SMEs, new local centres of expertise and technology development, and joint marketing and brand building for the clusters. As well as funding for operational activities in these areas, the cluster organisations could be supported by a framework to promote capacity-building and mutual learning across cluster organisations in the country and internationally on effective local and sector-specific SME and entrepreneurship support actions.

SME and entrepreneurship development should be integrated into effective regional smart specialisation strategies

Assessments of regional entrepreneurial ecosystem weak links are important to prioritising local policy actions to support start-ups and scale-ups and mobilising and co-ordinating national and regional public, private, research and education actors in addressing regional weaknesses. There is an established framework for regional strategy development into which these assessments and stakeholder consultations and engagements can be integrated, namely the process of preparing and implementing regional smart specialisation strategies for the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) actions. The current system of multi-level governance is overly bureaucratic and involves too many players, which has had a negative impact on policies such as Smart Specialisation and makes the formulation and implementation of regional and local level policies complex and difficult. The formation of local enterprise partnerships involving groupings of employers together with education and training institutions and government representatives could support the creation of regional SME and entrepreneurship development strategies.

Policy recommendations

Strengthen business support across the regions

Ensure the availability of adequate financial, training, mentoring and other business support for entrepreneurs and SMEs in each region, especially with regard to establishing start-ups with growth potential and introducing innovative products and processes.

Increase the provision of co-working spaces, business incubators and scale-up office space across the regions.

Strengthen cluster organisations

Support existing and new cluster initiatives by the provision of resources for cluster management organisations, strategy development processes and operational activities.

Bolster networking activities both within and across cluster initiatives through the organisation of purpose-driven and goal-oriented events and meet-ups.

Ensure that cluster initiatives are fully integrated into policy support for SMEs and entrepreneurship, and are not considered as standalone activities.

Involve local actors in regional entrepreneurial ecosystem development strategies

Establish regional entrepreneurial ecosystem assessments and development strategies for each of the eight regions, and integrate the assessments and strategies with the regional smart specialisation process.

Support the creation of local partnerships involving local authorities, strategically important enterprises, universities and business support providers to provide local intelligence and consultation for the formation of regional entrepreneurial ecosystem strategies and support the implementation of the strategies.

SMEs face challenges in digitalisation

Digitalisation reaps benefits for SME productivity and performance, including offering a route for small firms to upscale and increase efficiency, with large potential aggregate benefits for the wider economy. However, digitalisation is low in the Slovak Republic in general. In 2016, Slovak companies spent only 1.74% of gross fixed capital investment on computer hardware, for example, below most other OECD countries. In 2019, the European Union Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) ranked the Slovak Republic 21st among the 28 EU member states. At the same time, SMEs have lower digitalisation levels on average than larger firms. Low SME take up of digital technologies in the Slovak Republic reflects a number of challenges, in particular with respect to managing IT security issues, availability of workforce skills and IT specialists, availability of financing for digital investments and low connection speeds available through digital infrastructure.

Digital skills and other digitalisation framework conditions need to be strengthened

An important strand of Slovak government policy to support SME digitalisation needs to involve horizontal policy actions to improve digitalisation framework conditions. There should be a particular emphasis on tackling skills shortages. The Slovak Republic scores below the OECD average on “problem solving in technology-rich environments”, which is a measure of ease of use of digital technology in the adult population provided by the OECD Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). It also faces significant shortages of ICT specialists. However, only 12% of small firms in the Slovak Republic provided ICT training for their workforces in 2019, compared with 20% in the OECD area. The Slovak Government has taken some action to improve digital skills in recent years. For example, the dual education platform set up in 2016 aims to make the education system more attuned to the needs of the labour market, including digital needs. However, more needs to be done.

Additional important improvements to framework conditions for SME digitalisation should be made in the areas of upgrading digital infrastructure and improving regulations. In addition, the Slovak Government has made significant progress in e-government services over the last few years, for example by passing a law on “guaranteed” electronic invoicing for public tenders in 2019. The growth of e-government can be a further important stimulus for SME digitalisation by offering platforms, technologies, standards and demonstration effects for SMEs.

Business advice and financial support for SME digitalisation should be reinforced

Another strand of policy support for SME digitalisation should involve introducing targeted support to those SMEs and entrepreneurs that are highly motivated to embrace digitalisation and to specific sectors or clusters. This can catalyse their development and provide demonstration effects to the economy as a whole. In particular support for advice and finance on digitalisation is needed.

Access to finance can be a significant obstacle to digitalisation for some SMEs, particularly for those taking larger scale and riskier investment projects in more sophisticated technologies. Although access to credit is relatively easy in the Slovak Republic in general, it can be more difficult for intangible investments, while the Slovak Republic does not have a well-developed risk capital market. At the same time, public support for financing SME digitalisation has not been strong. Reinforcing this support could therefore have important impacts.

This should be combined with expanded business development services in the form of training, mentoring and coaching for SME digitalisation. Although the SBA has establised a network of National Business Centres, there appears to be no dedicated business advice programme to support SMEs with ambitious digitalisation plans.

Online business diagnostic tools can be an important entry point for businesses in need of support and advice, enabling SME users to benchmark their performance, identify areas for improvement, obtain guidance and links to support on how to address weak points. A number of business diagnostic tools internationally focus on SME digitalisation issues, as stand-alone tools or as part of broader diagnostic assessments of business operations. However, there is not currently such a tool aimed at Slovak SMEs.

Digitalisation actions could be better co-ordinated across government and with non-government actors

The Office of the Prime Minister has taken the lead in policy for digitalisation by developing the Strategy of the Digital Transformation of Slovakia 2030 and the Action Plan for the Digital Transformation of Slovakia 2019-2022. However, it is unclear how other ministries and government bodies will contribute towards its implementation. Moreover, there are a range of other strategies and players in this field, including the National Action Plan for Smart Industry 2018, which includes strategic goals related to SME digitalisation, and the National Coalition for Digital Skills and Occupations of the Slovak Republic, which was established in 2017 to propose measures to strengthen digital skills. Given the involvement of a large number of policy actors and actions, it is important to have strong cross-government co-ordination. This could include mapping of current initiatives affecting SME digitalisation, identification and scaling up of initiatives that work well, and filling gaps in support measures. High-level political leadership for this agenda will be important as well as an effective working-level co-ordination mechanism.

It is also important to strengthen government partnerships with non-government stakeholders. For example, working in partnership with government, Chambers of Commerce and business associations could do more to raise awareness of SME digitalisation needs, provide peer learning opportunities, and support the design and implementation of SME digitalisation policies.

Digital Innovation Hubs are not yet fully on-stream

One of the proposed initiatives of the Government’s Action Plan for the Digital Transformation of Slovakia is the creation of a network of Digital Innovation Hubs. These would act as one-stop shops to help companies expand their use of digital technologies. In April 2020, three Digital Innovation Hubs were under preparation (two in Bratislava and one in Kosice), but none were yet active. Making the network of Digital Innovation Hubs fully operational is an objective that should be pursued and is one of the measures proposed in the Government’s Smart Industry Action Plan.

Policy recommendations

Stimulate on-the-job training activities to acquire digital skills, possibly through the introduction of a tax allowance for SMEs investing in an approved training course for their personnel.

Pilot a finance support programme for digitalisation for relatively risky or advanced SME digitalisation projects.

Expand business development services (training, mentoring, coaching) to selected high-potential SMEs, and more basic services for firms in their early stages of digitalisation.

Develop an online business diagnostic tool for SME digitalisation in the Slovak Republic.

Include quantifiable and well-defined objectives related to SME digitalisation in the Strategy of the Digital Transformation of Slovakia 2030.

Create a cross-government coordination mechanism to design and implement policy responses related to SME digitalisation.

Improve collaboration with non-government bodies to provide support for SME digitalisation projects.

Establish Digital Innovation Hubs across the country, as foreseen in the Action Plan for the Digital Transformation of Slovakia, embedded within the smart specialisation strategy, and provide financial, logistical and human resources support to make them fully operational.

The Roma population experiences high labour market exclusion

It is estimated that there are between 400 000 and 500 000 Roma people in the Slovak Republic, accounting for 7-9 per cent of the country’s population. Approximately half of the Roma population live dispersed among the majority population and approximately half live in a Roma settlement (with a minimum threshold of 30 people). The regions with the highest shares of Roma in the population are in the east and south-east (Košice, Prešov and Banská Bystrica), which are relatively weak regions in economic performance.

The Roma community in the Slovak Republic suffers from very poor levels of labour market attachment. The majority of the Roma population are at risk of poverty, suffer from housing exclusion, have low life expectancy and weak upward social mobility between generations (see Table 1.1). For example, the probability of Roma born in concentrated residential areas becoming unemployed or earning less than a minimum wage in irregular work is almost 70% (OECD, 2019).

A number of issues are affecting Roma labour market participation, including low Roma education and skill levels, weakening demand for unskilled and low skilled workers as a result of structural economic change away from agriculture and heavy industry, stigmatisation of the Roma community and poor transport links to sources of jobs from Roma settlements.

Self-employment and business creation rates are also low

Low levels of labour market attachment are reflected in very low levels of formal self-employment among the Roma population in the Slovak Republic. UNDP (2012) estimated that only 1.8 per cent of the Roma working population were self-employed compared with 7.1 per cent of the general population living in nearby geographic areas. Whereas minority and disadvantaged communities frequently have higher rates of formal entrepreneurship than the population as a whole, since self-employment enables people to generate earned income in the face of barriers to employment, this route out of unemployment and poverty is not being fully exploited in the case of Roma in the Slovak Republic.

Policy needs to address a number of inter-related constraints that impact on the numbers of Roma people successfully operating in self-employment. These include:

discrimination in the market, which can make it difficult for Roma people to obtain suppliers and customers;

low education and skill levels among the Roma population, including language barriers, which affect entrepreneurial ambitions, opportunities, and networks and engagement with administrative and legal processes;

lack of labour market experience, which reduces the ability of Roma people to build entrepreneurship skills and networks and develop successful business ideas;

lack of finance, including lack of savings, credit history and bank credit;

the welfare trap, whereby people in receipt of welfare benefits could experience a reduction of net income from starting work as a result of losing welfare benefits.

At the same time, however, there are a number of successful Roma entrepreneurs, who could provide role models for other Roma people interested in self-employment. Some of them could also provide mentoring

There are only scattered public interventions for promotion of entrepreneurship by Roma people

The national government has developed a Strategy for the Integration of Roma, which is co-ordinated by the Office of the Slovak Government Plenipotentiary for Romani Communities and depends on the budgets of individual ministries. In 2018, expenditure was almost EUR 120 million, targeted especially at employability and employment (EUR 75 million), education (EUR 30 million) and housing (EUR 7 million) activities. No specific element of the strategy was dedicated to self-employment or entrepreneurship measures. Furthermore, the SBA (the main provider of support to entrepreneurs) has no tailored start-up programme dedicated to the Roma community. Dedicated microfinancing and business development advice for the Roma community could be very important in helping launch Roma entrepreneurship.

Social enterprises play a significant role in Roma labour market attachment

Several Slovak municipalities are active in supporting the labour market attachment of the Roma community in their areas through creation and operation of municipal firms offering fixed-duration employment to people without work. One of the common approaches of these social enterprise initiatives is the development of housing for the Roma community by the Roma community, but there are also many other product/service models. Work integration social enterprises such as these offer an important route for supporting Roma people to move from unemployment into employment or self-employment. They offer a period of supported employment that provides an employment history, new work skills, networks, role models and other benefits for moving into employment or self-employment. There is great potential to scale up and spread social enterprise initiatives run by municipalities and non-profit sector actors with national government support, as part of both the entrepreneurship and labour market policy agendas. Since the Slovak Republic’s adoption of the Social Economy and Social Enterprise Act in 2018, it is possible to provide public financial instruments, demand-support and compensatory forms of aid to social enterprises and this route can be exploited to strengthen support for Roma entrepreneurship.

NGOs are also providing support that can be built on

A number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are also involved in addressing Roma issues in the Slovak Republic. Very few offer specific support for employment or self-employment but some that are involved in training and skills development. These include the Association for a Better Life, Pontis Foundation and the Young Roma Association in the Slovak Republic, and the Brussels-based Roma Entrepreneurship Development Initiative (REDI), which operates internationally. There is an opportunity to expand thes training and finance programmes offered to Roma communities for self-employment and entrepreneurship by offering public financial support to NGOs for this purpose. Furthermore, Roma community centres are provind to be effective locations for social services in many municipalities, and there is an opportunity to deliver some custom-designed entrepreneurship training for Roma through these community centres.

A network of Roma entrepreneurship support organisations could be established

A key overall priority for government should be to identify successful types of social enterprises initiatives for the Roma and initiatives that are supporting Roma entrepreneurship and support them to upscale, including by working in collaboration with relevant municipalities and NGOs and participating in international initiatives. It would also be useful to create a network of organisations supporting Roma entrepreneurship and employment that can share good practice and organise peer-to-peer learning activities.

Policy recommendations

Labour market attachment through social enterprises

The Office of the Slovak Government Plenipotentiary for Romani Communities should introduce into its planning a strategy for the introduction of 40 additional municipal social enterprises by 2025. The Office should identify key stakeholders to provide detail to the plan and determine key targets to be achieved.

The Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic should be responsible for securing the required funding to achieve the strategy and dispersing the ring-fenced funds dependent upon the municipalities achieving agreed targets.

Conferences and government meetings where the Mayors of municipalities gather should be targeted by the Office of the Plenipotentiary to provide awareness, training and promotional support for the establishment of municipal social enterprises. A network of participating municipalities should also be established to enable peer-to-peer learning across the duration of the strategy.

The Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family of the Slovak Republic should review the amount of money that people on welfare benefits receive when they participate on a social enterprise programme to ensure that they will not be disadvantaged financially because they participate in such a programme. Any anomalies whereby a person entering a social enterprise programme is financially worse off should be identified and addressed.

Programme participants should be paid their salaries through formal bank accounts to help build a personal credit history.

Business creation and self-employment by Roma people

The Office of the Plenipotentiary should invite a small number of successful Roma entrepreneurs to create an ‘Association for Roma Entrepreneurs’ to help identify and promote Roma entrepreneurs as role models within the community.

The Association of Roma Entrepreneurs should be supported to introduce initiatives such as job shadowing and mentoring whereby nascent Roma entrepreneurs can learn from established entrepreneurs.

A microfinance programme should be introduced for Roma entrepreneurs, potentially managed by the Association for Roma Entrepreneurs. The Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic should be responsible for securing the required funding to achieve the strategy and dispersing the ring-fenced funds dependent upon the Association achieving agreed targets.

A one-stop shop or telephone line should be made available to provide access to business and legal support for nascent and established Roma entrepreneurs. This could be provided either through the labour offices or by the Association of Roma Entrepreneurs.

References

EU (2016), Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey, Roma – Selected findings, European Union, Agency for Fundamental Rights.

Eurostat (2020a), “BERD”, in Science, Technology and Innovation (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/science-technology-innovation/data/database.

Eurostat (2020b), “Continuing vocational training in enterprises” in Eduation and training (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/education-and-training/data/database.

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2020), Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (database), accessed on 5 March 2020, https://www.gemconsortium.org

OECD (2020a), “Structural and Demographic Business Statistics (SDBS)”, OECD, accessed on 10 Feburary 2020.

OECD (2020b), Revenue Statistics 2020-the Slovak Republic, OECD, accessed on 15 May 2020, https://www.oecd.org/tax/revenue-statistics-slovak-republic.pdf.

OECD (2020c), Regulatory Policy in the Slovak Republic: Towards Future-Proof Regulation, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ce95a880-en

OECD (2019) OECD Economic Surveys: Slovak Republic 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-svk-2019-en

SBA (2018), Report on the State of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the Slovak Republic in 2018, Slovak Business Agency (SBA), Bratislava.

Szerb, L., Vörös, Z., Komlósi, É., Acs, Z. J., Páger, B., and Rappai, G. (2017), The Regional Entrepreneurship and Development Index: Structure, Data, Methodology and Policy Applications. Pecs, Hungary (FIRES project).

UNDP (2012). Report on the Living Conditions of Roma households in Slovakia 2010. UNDP Europe and the CIS, Bratislava Regional Centre.