copy the linklink copied!3. Coverage and inclusiveness of adult learning in Latin America

This chapter provides an overview of the most salient gaps that affect the inclusiveness of adult learning systems in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region. It also discusses the actions that can be taken to make the access more inclusive and to boost participation of adults in learning activities.

A skilled workforce is a major determinant of economic and labour market performance. Skilled workers have a higher likelihood of being employed, and, at the same time, they tend to be more productive in their jobs.

Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) countries are characterised by low level of skills, low job quality and pervasive informality (see Chapter 1). Against this backdrop, investments and participation in adult learning become of paramount importance to help adults regularly update, upgrade and acquire entirely new skills to adapt to ever-changing labour markets and societies.

copy the linklink copied!Summary of the main insights

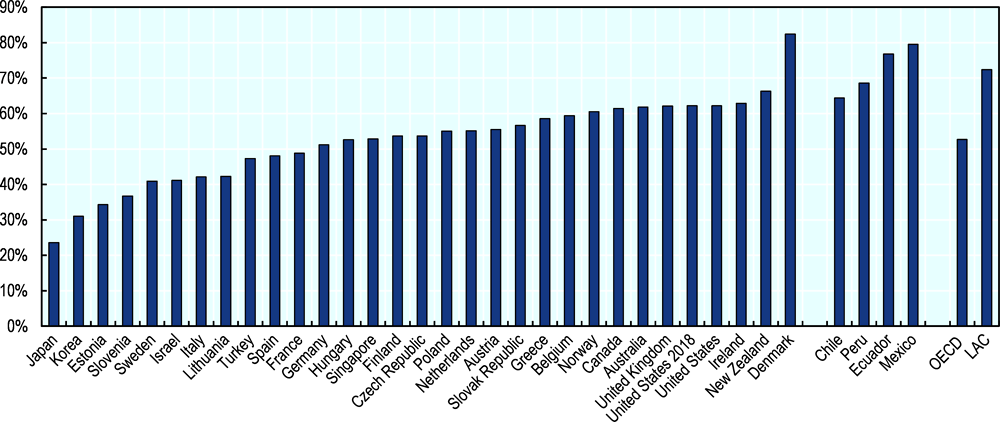

Participation in training in the LAC region stands more than 10 percentage points below the OECD average

-

In Latin America, approximately 57% of adults did not participate - and did not want to participate - in adult learning activities (compared to the OECD average of 49%). Participation in adult learning is, however, very heterogeneous. Chile and Peru for instance, show levels of participation that are similar to those of some developed economies such as Japan or Spain and even higher than those of other OECD countries such as Greece, Italy and Turkey. Other LAC countries, instead, lag much behind and too many adults are lacking willingness to participate in training.

-

The median number of hours spent on non-formal job related learning per year (an indicator of the intensity of the participation) is significantly lower in LAC countries than on average across OECD countries, suggesting that often times training programmes in Latin America are shorter than across OECD countries.

-

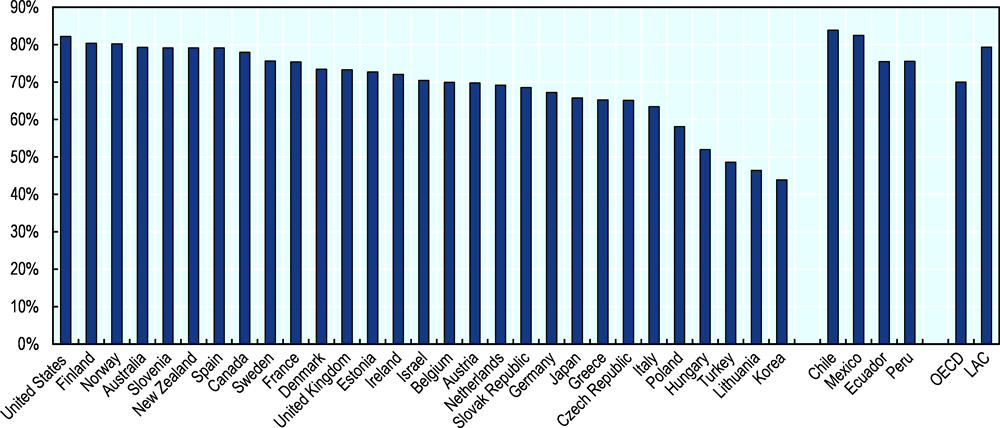

Also, the type of training differs between LAC countries and OECD countries. In LAC countries, adults participate more often in informal and less structured training than their peers across OECD countries. On average, for instance, 80% of workers in LAC countries report to learn by doing or from others, keeping their skills up-to-date with new products or services at least once per week but in an informal setting.

Informality represents a major challenge in Latin America

-

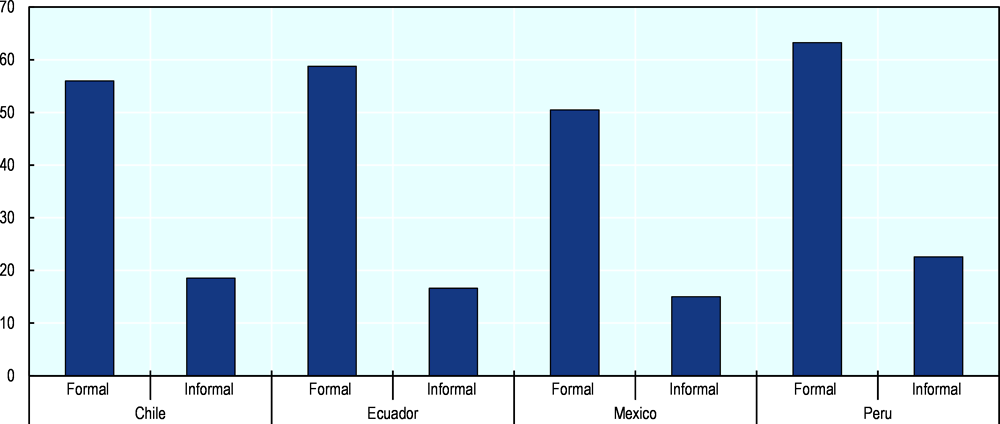

Evidence shows that informality in LAC countries is linked to weaker participation in training activities: a situation that perpetuates a vicious circle where informal workers do not train and lack of education leads to informality.

-

Evidence shows that workers employed without a regular contract are, on average, more than twice less likely to participate in learning activities than their peers who are employed formally. In some countries such as Ecuador, the difference in participation in learning activities between workers with and without an employment contract is staggering; approximately 42 percentage points.

Providing inclusive learning opportunities for all and, particularly to individuals in a region with high levels of inequalities such as Latin America is of paramount importance

-

The incidence of adults’ participation in training in the region, as across many countries, varies considerably depending on socio-economic background and/or on the employment status of the individual. Much needs to be done to make Adult Learning systems more inclusive. Low skilled individuals, who tend to be in lower-quality jobs, and often in the informal economy, participate less in training. Results show, in fact that one extra year of education increases the likelihood of participating in training by approximately 0.4% across OECD countries and slightly more (approximately 0.5%) and in Latin America.

-

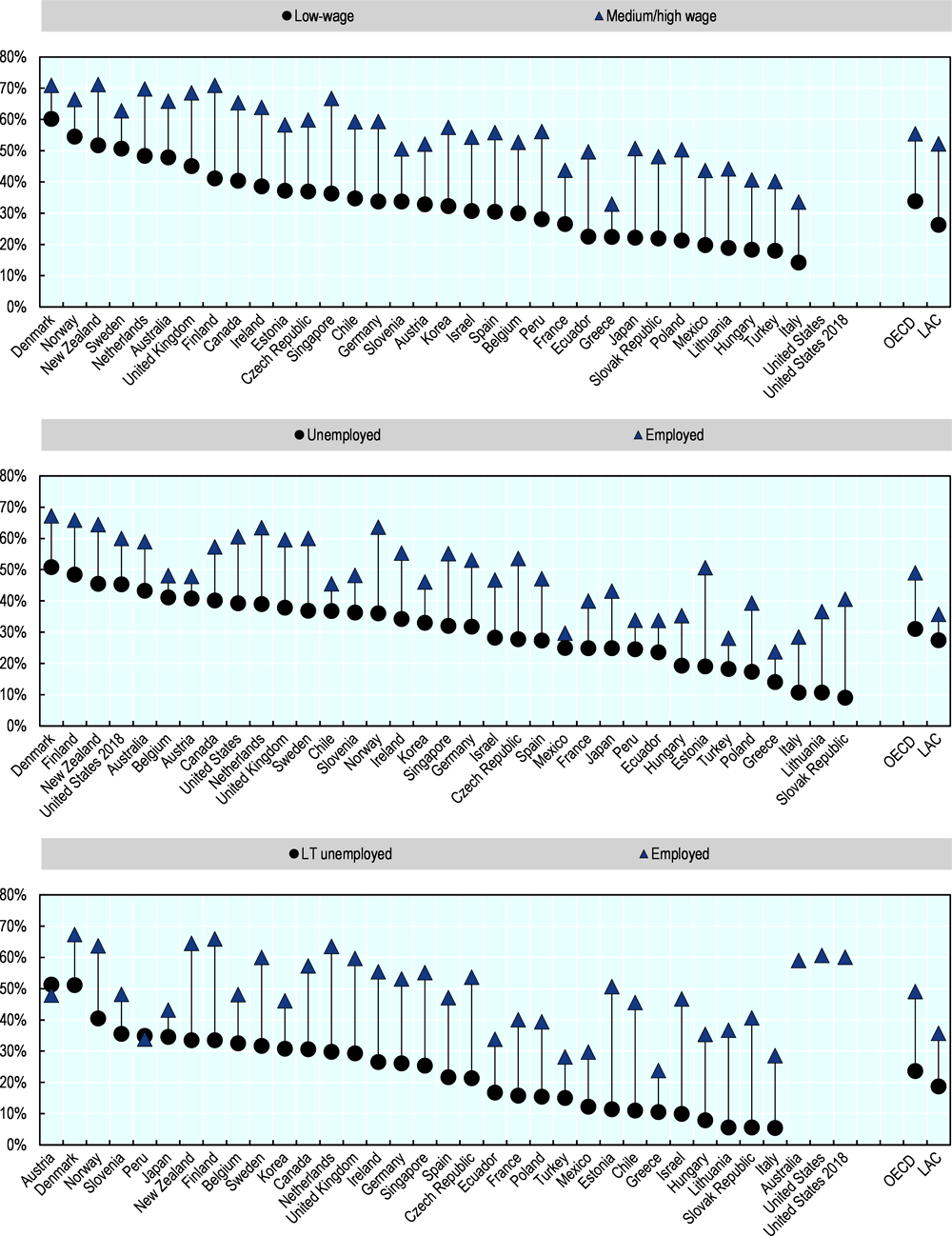

Employment status and job quality are also strongly related to the take-up of training. According to the Survey of Adult Skills, a product of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) data, on average in Latin America, the participation rate of the low-wage workers is 26 percentage points lower than that of higher-wages employees. This result is likely to be self-reinforcing, fostering a vicious circle as individuals participating less in training will also struggle the most to find high-quality and well-paying jobs.

-

Across LAC countries, the participation of women in learning activities is lower than that of men. Everything else constant, being a woman reduces the likelihood of participating in job-related training by 8% across OECD countries and by almost 19% in LAC countries. This result is driven by the large gap in participation between men and women in Chile, Ecuador and Peru.

-

Marital status play a far more important role in LAC countries than across OECD countries when it comes to the decision of participating in training. Being married reduces the likelihood to participate in training. While this probability is small and not significant in OECD countries, it is large and significant (approximately 17%) in LAC countries.

-

Perhaps surprisingly, workers with dependent children in LAC countries are significantly more likely to participate in job-related training activities than across OECD countries. One possible explanation can relate to the existence of numerous social protection training programmes implemented in the last two decades targeting vulnerable families (e.g. those where low skilled parents are in precarious jobs) in many LAC countries.

-

When focussing on demographic characteristics, the gap in participation between older and younger cohorts is relatively smaller across LAC countries than across many OECD countries. Once accounting for other individual characteristics, for instance, being ten years older is associated with only a 7% lower probability of participating in job-related training by workers in LAC countries.

-

In contrast with the majority of OECD countries, LAC countries display a very small gap in participation in adult learning between the unemployed and the employed population (only 8 percentage point differences vs. 17 percentage points across OECD countries). This result can be explained by the fact that most unemployed in LAC countries are young individuals who are also the recipients of the wide majority of public training programmes for adults (Jovenes programmes).

Firm size plays a much more important role in Latin America than in the OECD when it comes to engagement in training

-

Results show that individuals working in micro and small firms in Latin America are almost twice less likely to receive training than individuals working in firms of similar size across OECD countries. Results seem to suggest that, in Latin America, even more than in other regions, small firms may be facing greater challenges due to their limited capacity to plan, fund and deliver training.

-

Despite a widespread lack of interest to participate in training, individuals who have actually participated highly value the usefulness of training.

-

Reaching out to adults with information about the returns to training more widely should be a priority for Latin American governments. More effort should be also put in reducing barriers to participation altogether by reducing financial constraints and supporting individuals and families to find time for learning.

-

In Latin America, more than 70% of those individuals who actually participated in training found the learning activity very useful, almost 20 percentage points higher than the OECD average. Satisfaction is especially high in Ecuador and Mexico (77% and 79% of individuals who participated respectively) but very high also in Chile and Peru and still above the OECD average.

-

Lack of awareness about the effectiveness of training is likely to be at the core of the weak interest of individuals (especially the low skilled) to participate in training. These results seem to suggest that the visibility (i.e. information campaigns, career guidance etc.) and the perception around the usefulness of training activities in Latin America should be strengthened through specific policy interventions aiming at advertising more widely the benefits of learning across individuals who are, too often, lacking incentives to participate in training.

-

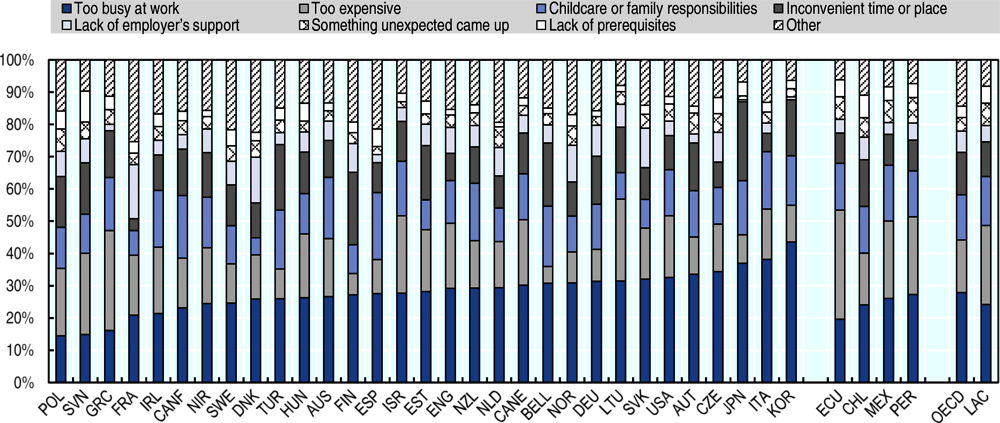

According to the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) data, the most common barriers to participation in learning activities in Latin America was the cost of training (24.5%), being too busy at work (24%) and childcare or family responsibilities (17%), hinting that lack of time can be an important barrier to participation. Financial constraints are particularly relevant for individuals in Ecuador, Mexico and Peru, while in Chile, being too busy at work is the main reason preventing participation in training.

copy the linklink copied!Participation in adult learning

Despite the importance that training plays in the context of rapidly changing societies and labour markets, evidence for the LAC countries that participated in the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) shows that less than 1 out 3 adults (29%) actually participate in formal or non-formal job-related training.

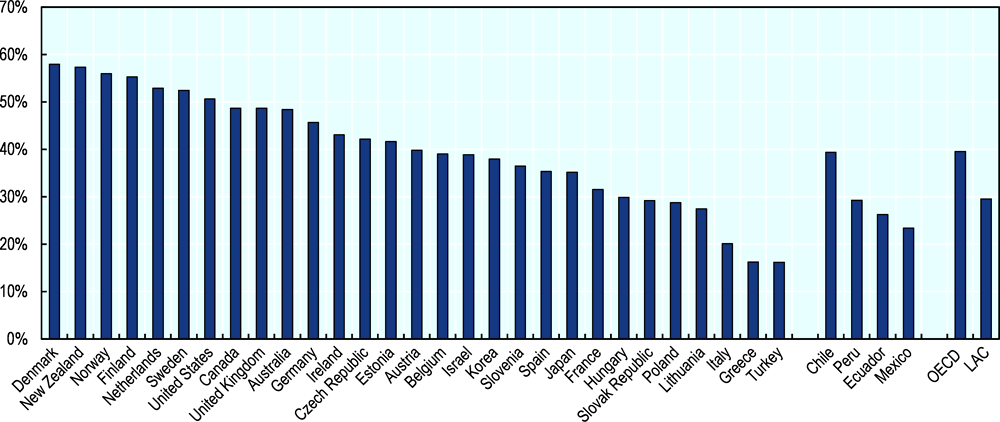

While low levels of participation in adult learning are a common problem across many countries, participation in training in the region still stands more than 10 percentage points below the OECD average (40%). According to the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) data, however, results are fairly heterogeneous across countries and some LAC economies, Chile and Peru for instance, show levels of participation that are similar to those of developed economies such as Japan or Spain (Figure 3.1) and even higher than those of other OECD countries such as Greece, Italy and Turkey.

One explanation of the relatively high levels of participation in training in some countries in the region can be traced back to the numerous public training programmes offered in those countries (see Chapter 4 for more details). That being said, while head-count participation in some countries may seem to be fairly good, the median number of hours spent on non-formal job related learning per year (an indicator of the intensity of the participation) is significantly lower in LAC countries than the OECD average. This suggests that often times training programmes in Latin America are shorter than across OECD countries.

Other differences between LAC countries and OECD countries relate to the type of training received by adults. In LAC countries, for instance, adults participate more often in informal (Box 3.1) and less structured training than their peers across OECD countries. On average, for instance, 80% of workers in LAC countries report that they learn by doing or from others, keeping their skills up-to-date with new products or services at least once per week (Figure 3.2).

Formal, non-formal and informal learning are measured according to standard definitions, and most of the analysis is restricted to learning that is job-related and that was undertaken in the previous 12 months. In particular:

Formal learning is defined as institutionalised, intentional and planned learning that leads to recognised qualifications.

It is important to note that such job-related formal training might have been undertaken in the context of a previous job or to improve outside opportunities. In other words, participation in job-related formal training does not necessarily refers to formal training provided by the current employer with direct application to the current job. Only individuals in paid work who have left the first cycle of formal studies are included in the sample. Hence, formal learning does not refer to initial education but rather to certified courses undertaken by adults while in paid work.

Non-formal learning is also institutionalised, intentional and planned, but typically includes shorter or lower-intensity courses, which do not necessarily lead to formal qualifications. This includes on-the-job training, open and distance education, courses and private lessons, seminars and workshops.

Two important facts are worth stressing. Firstly, as it is the case for formal training, the fact that this activity in job-related does not necessarily mean that it is directly related to the current job. Secondly, if the individual took part in more than one non-formal activity, the job-related nature of non-formal training will only refer to the latest activity taken in the last 12 months.

Informal learning is defined as intentional learning that is less organised and structured. In the context of this report it includes learning by doing or from colleagues (learning new work-related things from co-workers or supervisors) or keeping up to date with new products and services.

Source: Fialho, P., G. Quintini and M. Vandeweyer (2019[2]), "Returns to different forms of job related training: Factoring in informal learning", OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 231, https://doi.org/10.1787/b21807e9-en.

Chapter 1 already discussed the prevalence of informality in LAC countries and how informal employers may be less keen to provide training to their workers than formal ones. Official statistics on the participation of workers in learning generally struggle to capture the activities of informal workers. New evidence obtained for this report using the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) data on workers declaring to be employed without a formal contract (de facto, working informally) show, however, that participation in learning activities differ substantially between formal and informal1 workers in all the LAC countries for which this information is available (Figure 3.3). In particular, workers employed without a regular contract are, on average, more than twice less likely to participate in learning activities than their peers who are employed formally. In Ecuador, the difference in participation in learning activities between workers with and without an employment contract is staggering; approximately 42 percentage points.

copy the linklink copied!Inclusiveness of adult learning systems in Latin America

Vulnerable groups generally participate less in training

Ensuring broad-based coverage of adult learning is key to address the challenges of the future of work. Providing inclusive learning opportunities for all - and particularly to individuals in a region with high levels of inequalities such as Latin America - is of paramount importance. However, evidence shows that individuals most exposed to changes in skill needs, those with few and lower qualifications, the long-term unemployed and those at high risk of job automation are least likely to participate in training and are often under-represented in adult learning (OECD, 2019[4]). In Latin America, as across most OECD countries, the incidence of adults’ participation in training varies considerably also depending on socio-economic background and/or on the employment status of the individual.

Older workers, women and lower skilled workers in Latin America are, across most other OECD countries, less likely to engage in training. When focussing on demographic characteristics, the gap in participation between older and younger cohorts is, however, relatively smaller across LAC countries than across many OECD countries. Conversely, while the participation of women in learning activities is lower than that of men in both OECD and LAC countries, the gap is more pronounced in favour of men’s participation in Latin America, a result that seems to be driven by the relatively large gap in Chile, Ecuador and Peru.

Perhaps not surprisingly, low skilled individuals, who tend to be in lower-quality jobs, and often in the informal economy, participate less in training (see Chapter 1).

Employment status and job-quality (see Chapter 1) are also strongly related to the take-up of training. According to the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) data, on average in Latin America, the participation rate of the low-wage workers2 is 26 percentage points lower than that of the higher-wages employees. This result is likely to self-reinforce in a vicious circle as individuals participating less in training will also struggle the most to find high-quality and well-paying jobs.

Surprisingly, and in contrast with the majority of OECD countries, LAC countries display a very small gap in participation in adult learning between the unemployed and the employed population (8 percentage-point differences vs. 17 percentage points across OECD countries).

This result can be explained by the fact that most unemployed in LAC countries are young individuals3 who are also the recipients of the wide majority of public training programmes for adults (i.e. Jovénes programmes, see Box 3.2).

Since the 1990s, so-called Jóvenes programmes (youth training programmes) have been widely used in Latin America and the Caribbean to improve youth employability. The model, started in Chile, has been replicated in several countries across the region including Argentina, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Panama, Paraguay and Peru. This model targets disadvantaged youth - poor youth, usually from 16 to 24, with low levels of education and experience, unemployed or underemployed - providing them with a combination of vocational training and an internship at a firm in the private sector. Some programmes include socio-emotional skills training. The most generalised version of these programmes lasts in between three to six months only and both employers and participants receive financial incentives such as wage subsidies and daily stipends, respectively. In many cases, training is competitively offered through a public bidding system that ensures quality and fosters the participation of private training centres.

There is evidence that the Jóvenes programmes in Latin America and the Caribbean have had a positive impact on labour insertion and conditions. In particular:

In Colombia, Jóvenes en Acción, a programme that involved three months of classroom training and three months of apprenticeship in a private company. A randomised-controlled trial found the programme increased the probability of employment and wages for participants, especially for women (Attanasio, Kugler and Meghir, 2011[5]). Additionally, the gains have been found to be long-lasting. The programme had also a positive and significant effect of working in the formal sector (Attanasio et al., 2015[6]).

In Argentina, Entra21, a programme providing technical and life-skills training and internship with private sector employers. An experimental evaluation of the programme found that participants increased their probability of working in formal employment and also exhibited earnings about 40% higher than those in the control group (Alzua, Cruces and Lopez, 2016[7]).

In the Dominican Republic, Juventud y Empleo, is a training programme focused on improving vocational skills followed by a short internship in a private-sector firm. A randomised evaluation found positive effect on wages but not on employment, one year after training (Card et al., 2011[8]). A more recent study estimated the long-term effects found that a widening of the formal employability gap between treatment and control groups (Ibarraran et al., 2015[9]).

In Chile, Chile Jóven, a programme targeted at a group of urban youth considered to be “at risk” of social exclusion. The training was offered in two successive stages: a stage of working training lectures conducted by a training institution and a stage involving on the-job-learning in firm (an internship for a period of 3-6 months). Evaluations of this programme suggest that employment effects range from modest to meaningful –increasing the employment rate up to 5 percentage points with impact of 6 to 12 percentage points in the employment rate. In most cases results show a larger and significant impact on job quality, measured by getting a formal job, having a contract and/or receiving health insurance as a benefit (González-Velosa, Ripani and Rosas-Shady, 2012[10]).

Source: Busso, M. et al (2017[11]), Learning Better: Public Policy for Skills Development, https://doi.org/10.18235/0000799; J-PAL (2017[12]), J-PAL Skills for Youth Program Review Paper.

The drivers of training participation in Latin America and across OECD countries

According to data from the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), only 41% of adults in the surveyed OECD countries participate in formal or non-formal job-related training in a given year. Out of the remaining 59% of adults who did not participate in training, up to 49% declared not to be interested in doing so, fundamentally being disengaged or not motivated.

Disentangling the different drivers associated to the lack of participation in adult learning in LAC is of key importance to provide insights to policy makers on how to make their adult learning systems more effective and promote a culture of learning. Econometric analysis carried out for this report focuses on the various potential drivers of participation in training and confirms the descriptive statistics presented above while it also sheds light on some interesting differences between OECD and LAC countries.

First, the analysis corroborates the existence of a relationship between likelihood of participation in training and age, gender as well as years of education. Importantly, those relationships maintain statistical significance despite the inclusion of a large set of individual, job and employer characteristics controls in the regression. For instance, when looking at demographic characteristics, regression results show that holding everything else constant, being ten years older is associated with a 10% lower probability of participating in job-related training across OECD countries and 7% in LAC countries.

Education also plays an important role in explaining participation in training. Results show, in fact that one extra year of education increases the likelihood of participating in training by approximately 0.4% across OECD countries and slightly more (approximately 0.5%) in Latin America.

Regression analysis also shows that, holding other individual characteristics constant, gender and marital status play a far more important role in LAC countries than across OECD countries when it comes to the decision of participating in training. Notably, women in Latin America are much less likely to participate in training than men. Everything else constant, being a woman reduces the likelihood of participating in job-related training by 8% across OECD countries and by almost 19% in LAC countries. Being married also reduces the likelihood to participate in training, but while this probability is small and not significant across OECD countries, it is large and significant (approximately 17%) in LAC countries.

Interestingly, workers with dependent children in LAC countries are significantly more likely to participate in job-related training activities than across OECD countries. One possible explanation can relate to the existence of numerous social protection training programmes implemented in the last two decades targeting vulnerable families in many LAC countries (see Chapter 4).

Interestingly, and partly linked to the result highlighting the higher propensity of skilled workers to participate in training, regression analysis also shows that individuals employed in relatively more complex jobs (i.e. jobs requiring three or more years of experience) are twice more likely to engage in training activities in Latin America countries than across OECD countries. Workers in part-time jobs are also less likely to engage in learning activities across OECD countries, as well as in LAC countries.

Finally, employers and firms’ characteristics also matter a great deal for training participation. The size of the firm, for instance, plays a much more marked role in Latin America than across OECD countries. In particular, results show that individuals working in micro-small firms in Latin America are almost twice less likely to receive any training than individuals working in firms of similar size across OECD countries. Results seem to suggest that, in Latin America, even more than in other regions, small firms may be facing greater challenges due to their more limited capacity to plan, fund and deliver training.

Given that much learning takes place in the workplace, the engagement of employers in the design, implementation and financing of skill development opportunities is key to the success of adult learning systems. This result, coupled with the fact that small and micro firms are the vast majority of firms in LAC countries poses the fundamental challenge of finding policy mechanisms to spur a more effective engagement of small employers in the delivery of adult learning.

copy the linklink copied!Barriers to training participation in Latin America

In a world that is rapidly changing, those who do not engage in lifelong and adult learning are likely to suffer poor labour market outcomes and the risk of being left behind. Against this backdrop, however, too many adults still do not engage in training and show little interest in doing so altogether.

Results from the OECD Survey of Adults Skills (PIAAC) show that in LAC countries for which information is available, 57% of adults did not participate and did not want to participate in adult learning activities (compared to the already very high OECD average of 49%).

Despite the widespread lack of interest to participate in training, the perceived usefulness of training among individuals who have actually participated is considerably high. In Latin America, according to Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) data, with more than 70% of those individuals who participated in training found the learning activity very useful, almost 20 percentage points higher than the OECD average. Satisfaction is especially high in Ecuador and Mexico (77% and 79% of individuals who participated respectively) but very high also in Chile and Peru and still above the OECD average.4

Providing information and guidance can spur stronger participation in training

Lack of awareness about the effectiveness of training is likely to be at the core of the weak interest of individuals (especially the low skilled) in participating in training. These results seem to suggest that the visibility (i.e. information campaigns, career guidance, etc.) and the perception around the usefulness of training activities in Latin America should be strengthened through specific policy interventions aiming at advertising more widely the benefits of learning across individuals who are, too often, lacking incentives to participate in training.

Reaching out to the people excluded from adult learning provisions and raising awareness on the benefits of learning as well as providing high-quality information, advice and guidance is an important step to engage them proactively in training.

Public awareness campaigns may come in many forms. For instance, outreach through the workplace can be effective, particularly in engaging low skilled adults. In this context, trade unions can act as a bridge functioning between employers and employees with low skills who might be hesitant or unable to express their training needs (Stuart et al., 2016[13]; Parker, 2007[14]). In the United Kingdom, for instance, Unionlearn, supports workers in acquiring skills and qualifications to improve employability by using Union Learning Representatives (ULRs) to reach out to workers and help them identify their needs and arrange learning opportunities.

A community-based approach can also operate as a bridge between low-skilled adults and training opportunities. In Argentina, for example, community leaders share information on available training courses under the Hacemos Futuro programme. This programme aims at supporting school dropouts in gaining primary and secondary qualifications and providing access to vocational training. Potential participants receive the information via mobile phone and bring together people in their community to pass the information (OECD, 2019[4]).This is particularly relevant in a context with low digitalisation and internet connectivity, as it can often be the case in many LAC countries or, for instance, in rural areas (see Chapter 3).

Career guidance is another tool that allows individuals to assess one’s skill set and plan her/his skills development plan as well as the training programmes that are most appropriate to achieve the result. It is, however, very difficult to get career guidance right and in many countries these activities are under-funded and non-effective. In order for career guidance to be effective, this needs to be based on timely labour market information and on the outputs of skill assessment and anticipation exercises (see Chapter 3).

Financial constraints are significant barriers to participation in training, but well-designed financial incentives could help overcome these obstacles

Among those who did not engage in training, a non-negligible share of adults (14%) wanted to participate but were not able due to a variety of obstacles. According to the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) data, the most common barriers to participation in learning activities in Latin America were financial barriers (the cost of training, 24.5%), being too busy at work (24%) and childcare or family responsibilities (17%). Financial constraints are particularly relevant for Ecuador, Mexico and Peru, while in Chile, being too busy at work is the main reason preventing participation in training (Figure 3.7).

Financial constraints seem to be particularly important in Latin America in preventing individuals from participating in training. This issue is particularly severe for low-skilled individuals, who often end up holding low-quality informal jobs with limited opportunities for employer-sponsored training or alternate between work and periods of unemployment.

Many workers may also feel disengaged as there is substantial uncertainty about whether participating in training will actually lead to positive labour market returns or have a clear impact on their career progression.5

Designing policy incentives aimed at strengthening the linkages between labour market and career progression and the participation in training (making the former conditional on the latter, for instance) could go a long way in providing robust incentives to individuals to engage in learning and address financial constraints hindering participation. More training, in turn, would lead to obvious benefits spreading to firms and employers who could count on a more skilled workforce able to increase productivity and adopt new technologies.

Targeted financial incentives may help adult learning systems becoming more equitable and preventing underinvestment. Many OECD countries have implemented measures such as training vouchers, allowances, wage and training subsidies, tax incentives and individualised learning account schemes to encourage training participation (OECD, 2017[15]).

Lack of time is a major obstacle to participate in training

Another key obstacle for adult participation in training that emerged from analysis with the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) data is the lack of time, for both family and work-related reasons. Being too busy at work and childcare or family responsibilities were mentioned to be important barriers in 24 and 17% of the cases respectively. The delivery of flexible adult learning courses can greatly help overcome some of these barriers. Modular training, which divide a learning programme into self-contained modules, can allow adults to learn at their own pace and reduce constraints related to lack of time to follow the courses. A good example of a modular learning programme is the Modelo Educación oara la Vida y el Trabajo - MEVyT (Model for Life and Work Programme), in Mexico. MEVyT allows adults to obtain qualifications through different modules at initial, intermediate (primary education) and advanced (lower secondary education) level. The programme allows individuals to choose their own learning programme and gives them choice on the learning mode (i.e. if studying on their own or in group setting in community learning centres, on line or in a mobile learning space) (OECD, 2019[4]).

Digital and online training programmes (e.g. e-learning) can also help enhance flexibility in learning, broadening access to training while keeping the costs low. These training, however, come with important drawbacks that are especially important in the LAC region. In particular, use of digital technologies can limit, the access of low-skilled and digital illiterate individuals and it can be out of reach for those who do not have access to broadband or digital infrastructures (see Chapter 3). Finally, education and training leaves are other policy options that enhance flexibility allowing adults to take time for learning (OECD, 2019[4]).

References

[7] Alzua, M., G. Cruces and C. Lopez (2016), “Long‐run effects of youth training programs: experimental evidence from Argentina.”, Economic Inquiry, Vol. 54, pp. 1839-1859, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12348.

[6] Attanasio, O. et al. (2015), “Long term impacts of vouchers for vocational training: Experimental evidence for Colombia”, NBER Working Paper Series, No. 21390, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge MA, https://doi.org/10.3386/w21390.

[5] Attanasio, O., A. Kugler and C. Meghir (2011), “Subsidizing vocational training for disadvantaged youth in Colombia: Evidence from a randomized trial”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 33/3, pp. 188-220, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.3.3.188.

[11] Busso, M. et al. (2017), Learning Better: Public Policy for Skills Development, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, D.C, https://doi.org/10.18235/0000799.

[8] Card, D. et al. (2011), “The labor market impacts of youth training in the Dominican Republic”, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 29/2, pp. 267-300.

[2] Fialho, P., G. Quintini and M. Vandeweyer (2019), “Returns to different forms of job related training: Factoring in informal learning”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 231, https://doi.org/10.1787/b21807e9-en.

[10] González-Velosa, C., L. Ripani and D. Rosas-Shady (2012), How Can Job Opportunities for Young People in Latin America be Improved?, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington D.C., https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/How-Can-Job-Opportunities-for-Young-People-in-Latin-America-be-Improved.pdf.

[9] Ibarraran, P. et al. (2015), “Experimental Evidence on the Long-Term Impacts of a Youth Training Program”, IZA Discussion Paper Series, No. 9136., IZA.

[12] J-PAL (2017), J-PAL Skills for Youth Program Review Paper, Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, Cambridge, MA.

[4] OECD (2019), Getting Skills Right: Future-Ready Adult Learning Systems, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264311756-en.

[1] OECD (2019), Priorities for Adult Learning dashboard, http://www.oecd.org/employment/skills-and-work/adult-learning/dashboard.htm.

[15] OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: Skills for Jobs Indicators, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264277878-en.

[3] OECD (2017), Survey of Adults Skills (PIAAC) (2012, 2015, 2017), (database), http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/.

[16] OECD/CAF/UN ECLAC (2016), Latin American Economic Outlook 2017: Youth, Skills and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/leo-2017-en.

[14] Parker, J. (2007), Policy Brief Workplace Education: Twenty State Perspectives, National Commission on Adult Literacy, http://www.caalusa.org/content/parkerpolicybrief.pdf.

[13] Stuart, M. et al. (2016), Evaluation of the Union Learning Fund Rounds 15-16 and Support Role of Unionlearn, University of Leeds, https://www.unionlearn.org.uk/sites/default/files/publication/ULF%20Eval%201516%20FINAL%20REPORT.pdf.

Notes

← 1. While the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) data do not allow to exactly identify informal workers using the common legal or productive definition of informality, they allow to identify workers that, despite being employed, do not have a contract.

← 2. Low wage workers are those who earn less than two-thirds of median wages.

← 3. Unemployment rates are almost three times higher for youth aged 15-29 (11.2%) than for adults aged 30-64 (3.7%) in all countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (OECD/CAF/UN ECLAC, 2016[16]).

← 4. These results should, however, taken with caution as self-reported satisfaction may, in some cases, respond to cultural and subjective biases.

← 5. Results from probit regression analysis run on the probability of non-participating in training and not wanting to participate confirm findings in the literature that those who would benefit the most from training – i.e. the least skilled workers, most vulnerable workers – tend not to participate (and to be under-represented). These results are not shown but available upon request.

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/f6b6a726-en

© OECD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.