copy the linklink copied!Chapter 1. Recent pension reforms

This chapter looks at pension reforms in OECD countries over the past two years (between September 2017 and September 2019). Pension reforms have lost momentum with both improving economic conditions and increasing political pressure in some countries not to implement previously decided measures. Over the last two years, most pension reforms focused on loosening age requirements to receive a pension, increasing pension benefits including first-tier pensions, expanding pension coverage or encouraging private savings. Some recent major policy actions have also consisted of partially reversing previous reforms.

copy the linklink copied!Introduction

Population ageing is accelerating in OECD countries. Over the last 40 years the number of people older than 65 years per 100 people of working age (20-64 years) increased from 20 to 31. By 2060, it will likely have almost doubled to 58. In particular, population ageing is expected to be very fast in Greece, Korea, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and Spain, while Japan and Italy will remain among the countries with the oldest populations.

Rapid ageing puts continuous pressure on pension systems. The legacy of the great financial crisis leaves many countries with high public debt and therefore limited room for manoeuvre. In addition, risks of increasing old-age inequality (OECD, 2017[1]), the development of non-standards forms of work (Chapters 2 and 3) and the low-growth and low-interest-rate environment present new challenges for already stretched pension systems. Low interest rates actually generate both new challenges and opportunities. Low government bond rates sharply reduce the cost of public debt, especially when they are lower than GDP growth rates (Blanchard, 2019[2]), which has been the case in many OECD countries in recent years. At the same time, low interest rates limit the returns on assets from funded pension plans and increase discounted liabilities, potentially lowering future pensions from funded defined contribution schemes and threatening the solvency of funded defined benefit schemes (Rouzet et al., 2019[3]). Low interest rates might also reflect low-growth prospects, potentially influenced by ageing itself, in which pension systems regardless of their form will struggle to deliver adequate and financially sustainable pensions.

Dealing with the challenges of ageing societies might involve increasing contributions, which could lead to lower net wages and higher unemployment, and/or cutting pension promises. Against this background, working longer is crucial to maintaining pension adequacy and financial sustainability. However, raising the retirement age has often proved to be among the more contentious pension reforms.

In the wake of the global financial crisis, many countries had taken measures to improve the financial sustainability of their pension system. Over the last two years, most pension reforms focused on loosening age requirements to receive a pension, increasing pension benefits including first-tier pensions, expanding pension coverage or encouraging private savings.

Despite the persistent needs to adjust to demographic changes, risks are mounting that countries will not deliver on adopted reforms. Pension reforms have lost momentum with both improving economic conditions and increasing political pressure not to implement previously decided measures. Some recent major policy actions have consisted of partially reversing previous reforms. With improving economic conditions, it might make sense to soften measures decided to improve short-term financial balances. However, short-term difficulties often highlight structural weaknesses. Backtracking might then raise concerns if it means not implementing reforms that actually address long-term needs such as those driven by demographic changes.

The Slovak Republic decided to abolish the link between the retirement age and life expectancy, reversing the 2012 reform and instead committing to raising the retirement age to 64, which will be reached through discretionary increases. Italy eased early-retirement conditions and suspended the link between the retirement age and life expectancy for some workers until 2026. Spain suspended the adjustment mechanism for indexation of pensions in payments, which is based on total contributions, the number of pensioners and the financial balance of pensions and of the Social Security system, in 2018 and 2019. It also suspended until 2023 the sustainability factor (meant to ensure financial sustainability), which from 2019 would have adjusted initial pensions when retiring to improvements in life expectancy. In the Netherlands, the statutory retirement age was temporarily frozen and a law to revise the link between the retirement age and life expectancy is expected to be presented to parliament soon. Looking back over the last 4 years, similar reform reversals happened in Canada, the Czech Republic and Poland.

Key findings

The main recent pension policy measures in OECD countries include:

limiting the increase in the retirement age or expanding early-retirement options (Italy, the Netherlands and the Slovak Republic);

raising the retirement age (Estonia);

enhancing work incentives (Belgium, Canada and Denmark);

increasing the level or expanding the coverage of first-tier pensions, the first layer of old-age social protection (Austria, France, Italy, Mexico and Slovenia);

increasing benefits while reducing contributions for low earners (Germany);

suspending the adjustment of pension benefits with demographic changes (Spain);

bringing public-sector pension benefits more in line with private-sector benefits (Norway);

changing the contribution rates (Hungary, Iceland and Lithuania) or expanding contribution options (New Zealand);

expanding the coverage of mandatory pensions (Chile) or developing auto-enrolment schemes (Lithuania and Poland); and,

changing tax rules for pensioners (Sweden).

Other findings:

Those aged over 65 currently receive less than 70% of the economy-wide average disposable income in Estonia and Korea, but slightly more than 100% in Israel, France and Luxembourg. On average in the OECD, the 65+ receive 87% of the income of the total population.

The relative poverty rate for those older than 65 – defined as having income below half the national median equivalised household income – is slightly higher than for the population as a whole (13.5% versus 11.8%) for the OECD on average. The old-age poverty rate is lower than 4% in Denmark, France, Iceland and the Netherlands, while it is larger than 20% in Australia, Estonia, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico and the United States.

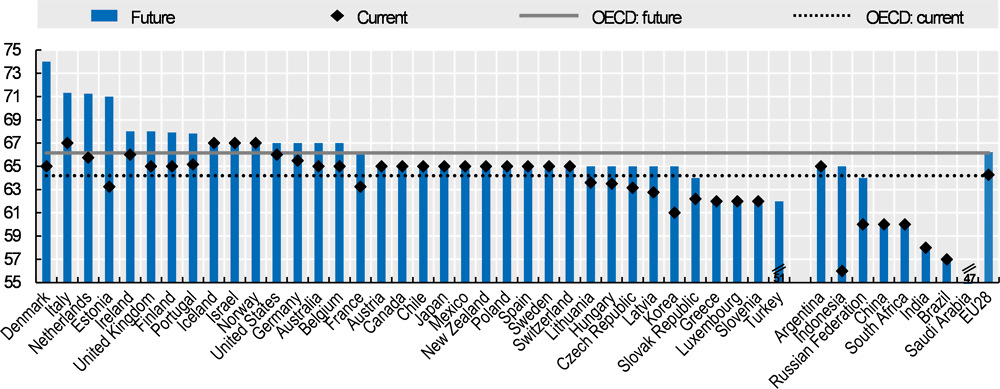

A little over half of all OECD countries will raise the retirement age. On average across the OECD countries, the normal retirement age will increase by 1.9 years by about 2060 for men from 64.2 years currently to 66.1 years based on current legislation. This represents almost half of expected gains in life expectancy at 65 over the period and compares to an average increase in the normal retirement age of about 1.5 years over the last 15 years.

In 2018, the normal retirement age – eligibility age to a full pension from all components after a full career from age 22 - for men was 51 in Turkey whereas in Iceland, Italy and Norway it was 67 for both men and women. Given current legislation, the future normal retirement age will range from 62 in Greece, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Turkey to 71 or more in Denmark, Estonia, Italy and the Netherlands.

The gender gap in retirement ages, which existed in 18 countries among individuals born in 1940, is being eliminated, except in Hungary, Israel, Poland and Switzerland.

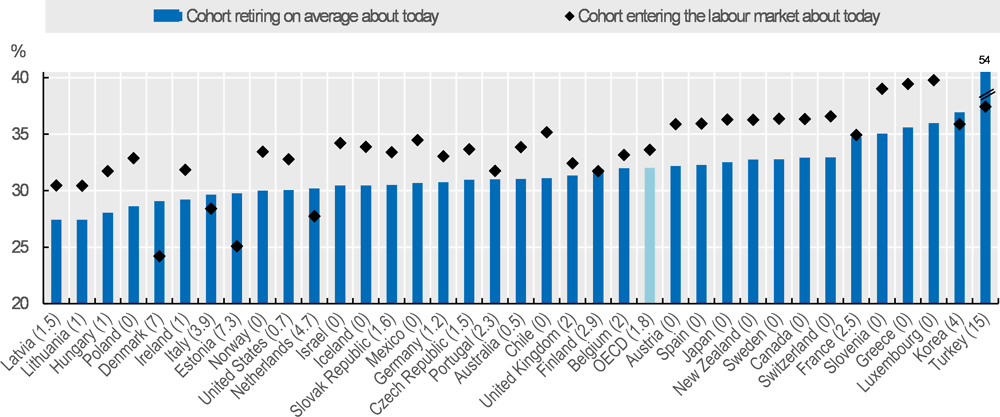

The share of adult life spent in retirement is still increasing in the vast majority of OECD countries. The cohort entering the labour market about today is expected to spend 33.6% of adult life in retirement compared with 32.0% for the cohort retiring on average today.

Future net replacement rates from mandatory schemes for full-career average-wage workers equal 59% on average, ranging from close to 30% in Lithuania, Mexico and the United Kingdom to 90% or more in Austria, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal and Turkey at the normal retirement age.

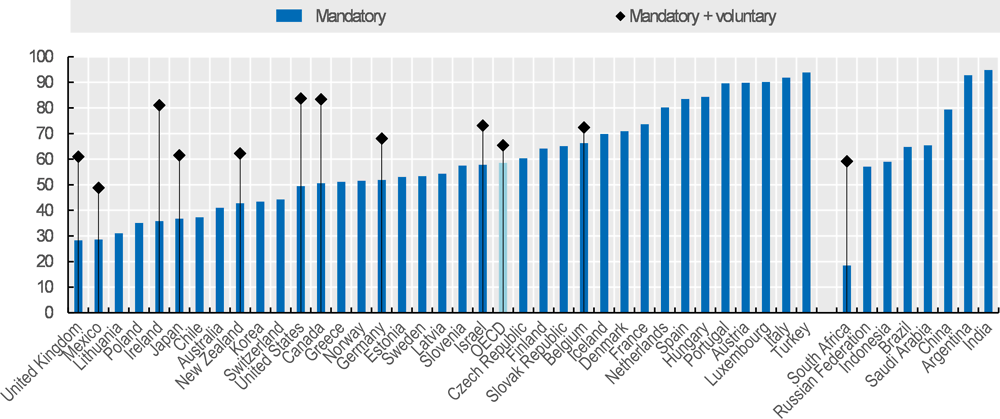

In countries with significant coverage for voluntary pensions – Belgium, Canada, Germany, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States – being covered by a voluntary pension boosts future net replacement rates by 26 percentage points on average for average earners contributing during their whole career and by about 10 percentage points when contributing from age 45 only, based on the modelling assumptions used in the OECD projections.

Average-wage workers who experience a 5-year unemployment spell during their career face a pension reduction of 6.3% in mandatory schemes on average in the OECD compared to the full-career scenario. The loss exceeds 10% in Australia, Chile, Estonia, Iceland, Latvia, Korea, Mexico, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Turkey. In Spain and the United States, a 5-year career break does not influence pension benefits, as full benefits in the earnings-related scheme are reached after 38.5 and 35 years of contributions, respectively.

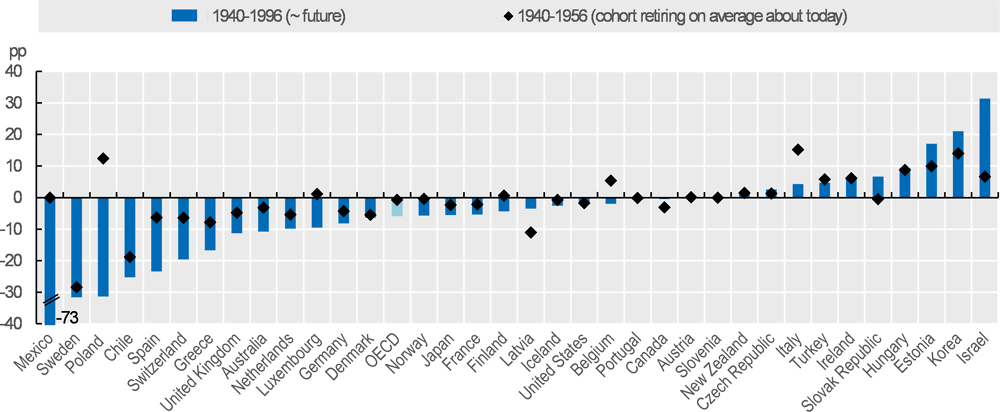

Replacement rates after a full career are projected to fall by about 6 percentage points on average (i.e. by slightly more than 10%) between those who retired about 15 years ago and those recently entering the labour market. They will fall in about 60% of OECD countries, increase in about 30% of them and be roughly stable in the remaining 10%.

The rest of the chapter is organised as follows: the second section sets the scene by providing some key indicators on population ageing. The third section details the most recent pension reforms and the fourth section focuses on the long-term trends in pension reforms.

copy the linklink copied!Population ageing: demographic trends, income and employment

Population ageing

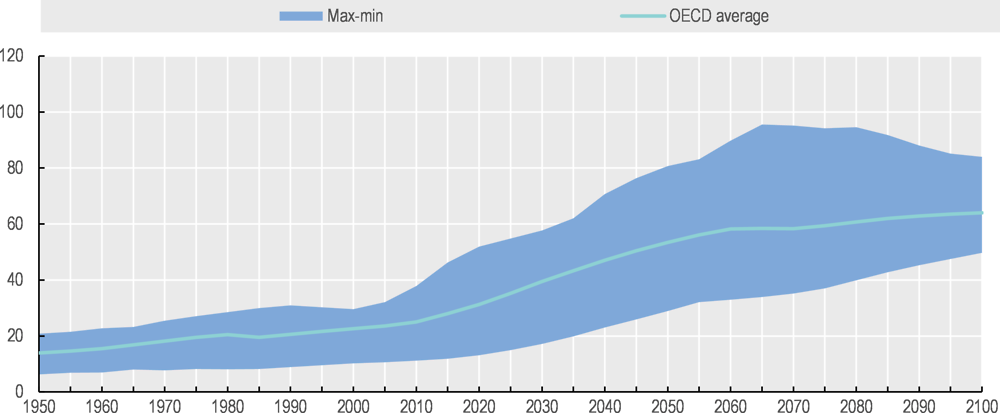

Population ageing is accelerating. Over the last 40 years, the old-age to working-age ratio – the number of people older than 65 years per 100 people of working age (20 to 64 years) – has increased by a little more than 50% in the OECD on average, from 20 in 1980 to 31 in 2020 (Figure 1.1). Over the next 40 years, it will almost double to a projected 58 in 2060. This rapid rise in the old-age to working-age ratio results from people living on average far longer and having fewer babies. A striking feature of the below chart is the growing dispersion of projected old-age to working-age ratios among OECD countries in the first half of the 21st century: while populations are getting older in all OECD countries, differences in the pace of ageing across countries are resulting in diverging population structures.

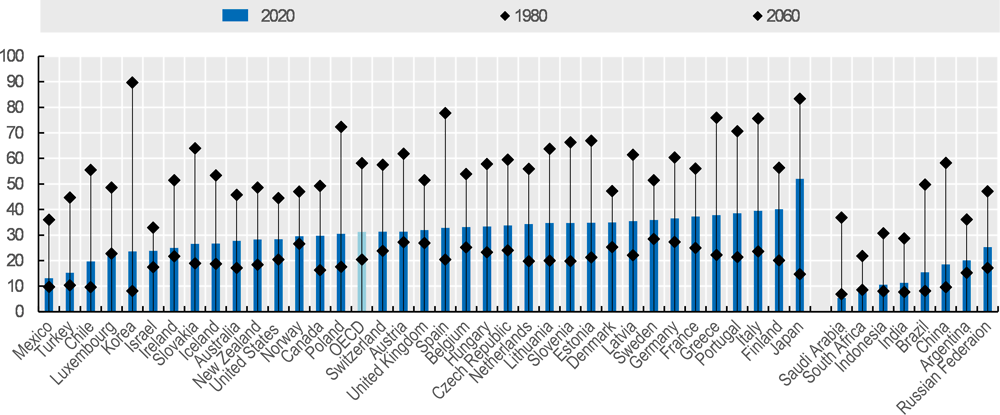

Denmark, Finland and Sweden, which currently have relatively high old-age to working-age ratios, will have below average ones in 2060 (Figure 1.2). On the other hand, in Korea and Poland the population is currently younger than average – based on this indicator – but will rapidly age and these two countries will end up having above average old-age ratios. Based on changes by 2060, Greece, Korea, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and Spain will age at the fastest pace, while Japan and Italy will remain among the countries with the oldest populations.1 Among non-OECD G20 countries, the pace of population ageing is faster in Brazil, China and Saudi Arabia than the OECD average, but they have currently younger populations.

The projected working-age population (20-64) will decrease by 10% in the OECD on average by 2060, i.e. by 0.26% per year. It will fall by 35% or more in Greece, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland, and increase by more than 20% in Australia, Israel and Mexico (Figure 1.3). This will have a significant impact on the financing of pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) systems as it is closely related to their internal rates of return. Even funded pension systems might be negatively affected by rapidly declining working-age populations through its effect on labour supply, in turn potentially lowering output growth and equilibrium interest rates.

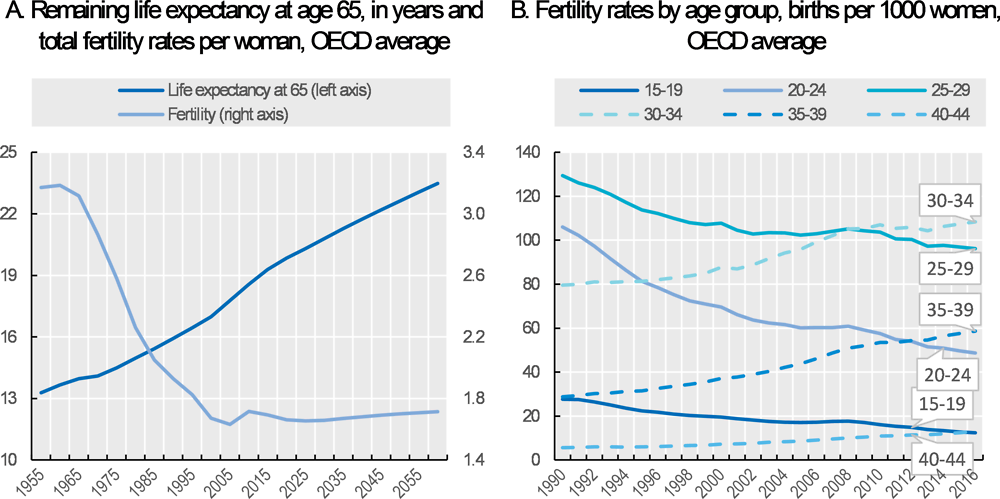

The improvement in remaining life expectancy at age 65 will slow a little. It increased from 13.7 years in 1960 to 15.9 years in 1990 before accelerating to 19.8 years in 2020 in the OECD on average (Figure 1.4). It is expected to rise further to 22.6 years in 2050. Differences in life expectancy between countries are and will remain substantial. In Hungary (having the lowest life expectancy) remaining life expectancy at age 65 is currently 17.2 years while in Japan (having the highest life expectancy) it is 22.4 years. The range of remaining life expectancies at 65 among OECD countries is expected to stay constant over time, with Latvia at 19.8 years and Japan at 25.0 years in 2050.

Fertility sharply fell from 3.2 children per woman aged 15 to 49 in 1955 to 1.6 in 2005 on average (Figure 1.4, Panel A). Since the early 2000s it has remained rather constant with average fertility rates currently at 1.7. Most of the initial drop can be attributed to lower infant mortality and rising opportunity cost of having children, which, in turn, can be linked to women’s increasing financial incentives for working and building a career (OECD, 2017[4]).

Women are also having babies later in life on average and female employment rates have risen substantially (OECD, 2017[4]). Fertility rates of women aged below 30 have roughly halved since 1990 while fertility rates of women in their 30s have increased significantly (Panel B). However, the former effect outweighs the latter. Overall, women aged 30-34 now give birth more often that those aged 25-29, and those aged 35-39 more often than the 20-24 age group. While low overall fertility can put pressure on the financial sustainability of pension systems, falling fertility rates at very young ages, rising female education levels and rising female employment rates are major accomplishments, which improve women’s well-being and reduce their old-age poverty risks (see next subsection).

Old-age income

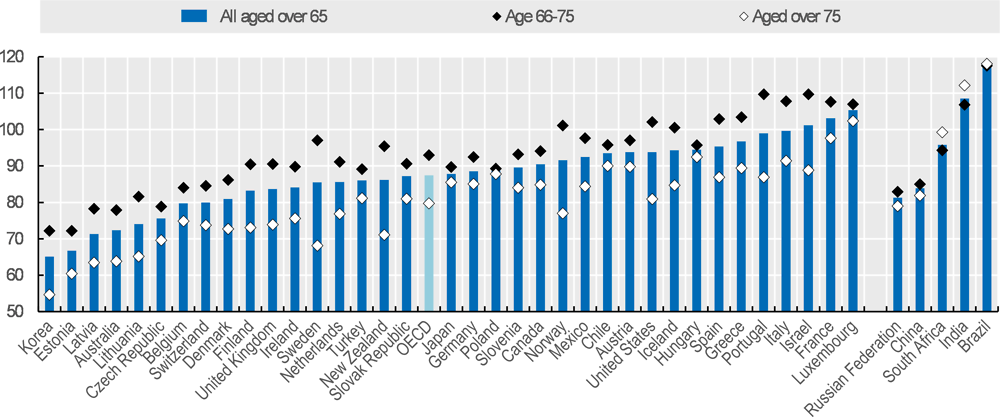

On average among OECD countries, people older than 65 have a disposable income equal to 87% of the total population. It is less than 70% of the economy-wide average in Estonia and Korea, but slightly more than 100% in France, Israel and Luxembourg (Figure 1.5). Moreover, income drops further with age in old age, and those older than 75 have a significantly lower income than the 66-75 in all OECD countries, with an average difference of 14 percentage points. In most non-OECD G20 countries it is the other way around, old-age income rises slightly with older ages, except in China and the Russian Federation.

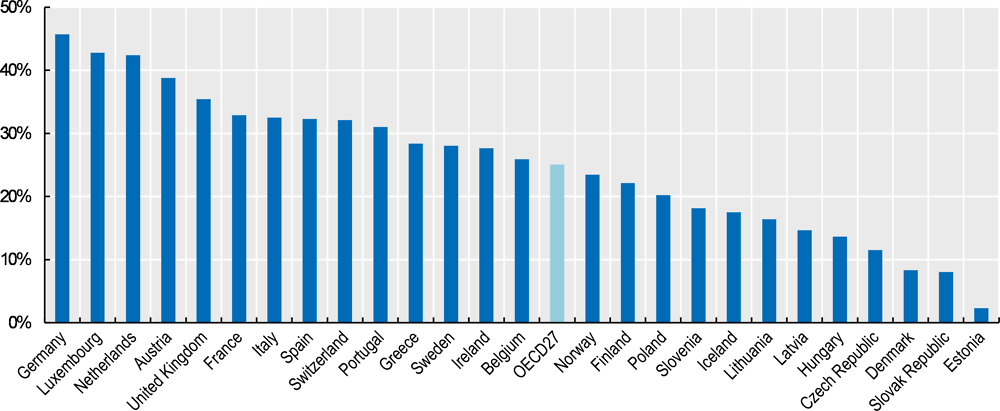

Women’s pensions are lower than men’s (Lis and Bonthuis, 2019[5]). Older women often had short careers and lower wages than men’s, resulting in low benefit entitlements. In the EU-28, women’s average pensions were 25% lower than the average pension for men in 2015 (Figure 1.6). The gender gap stood at over 40% in Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands and below 10% in Denmark, Estonia and the Slovak Republic. This also translates into a disproportionate share of poor elderly people being women (Table 7.2 in Chapter 7). On the one hand, with recent moves towards tighter links between labour income and pensions in many countries (see Section 4), the gender pension gap might remain persistently high. On the other hand, women’s improved labour market positions will contribute to lowering that gap.

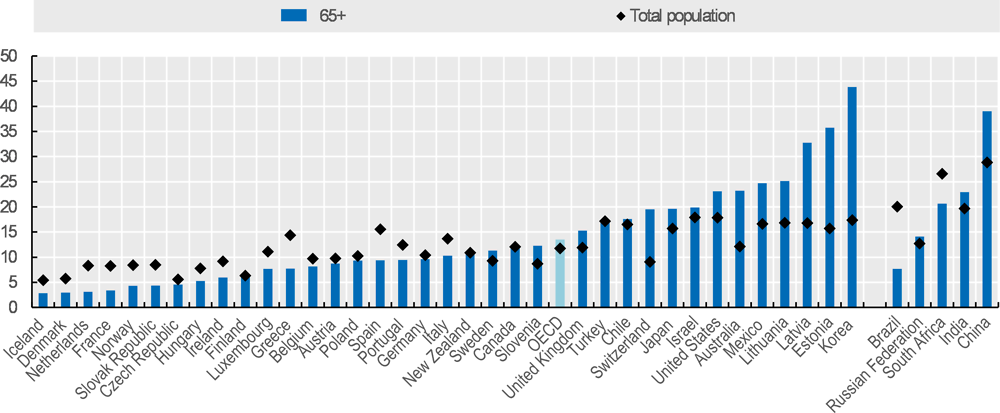

Poverty risks have shifted from older to younger groups in most OECD countries since the mid-1990s (Table 7.3 in Chapter 7). Some indicators such as the European Commission (2018[6])’s at-risk-of-poverty-or-social-exclusion indicator even show that poverty among older age groups is lower than poverty among the working-age population in the EU.2 However, the relative old-age (65+) poverty rate defined as having income below half the national median equivalised household income is still higher among the 65+ than for the population as a whole, at 13.5% vs 11.8% (Figure 1.7) as the old-age poverty rate is very high in some countries. More than one in five people above 65 are relatively poor in Australia, Estonia, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico and the United States.3 For non-OECD G20 countries this is also the case in China, India and South Africa. Conversely, less than 4% of the 65+ live in relative poverty in Denmark, France, Iceland and the Netherlands.

Older age groups (75+) still have significantly higher poverty rates (Table 7.2 in Chapter 7). There are several reasons for this. First, a larger share of the 75+ age group is female: women’s lower pensions than those of men combine with higher life expectancy. Second, in some countries pension systems are still maturing, meaning that currently not all older people have been covered during their entire working lives. And third, pension benefits are often price-indexed, meaning that they are likely to fall relative to wages.

Employment of older workers

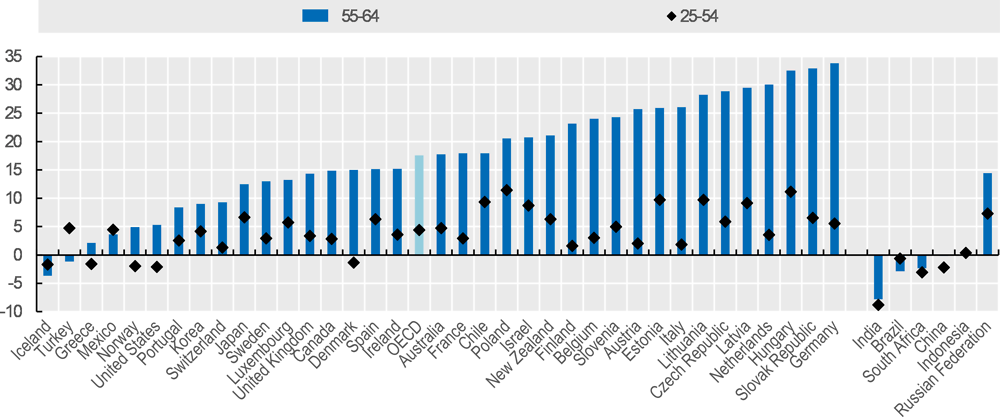

Since 2000, labour market participation among older individuals has increased significantly while unemployment among this group has remained low in most OECD countries. This is a major achievement. The employment rate among individuals aged 55 to 64 grew by more than 17 percentage points, from 43.9% in 2000 to 61.5% in 2018, on average in the OECD, while in emerging economies it increased much less (Figure 1.8). The increase has been substantial, larger than 28 percentage points, in the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands and the Slovak Republic. During the same period, the employment rate among people aged between 25 and 54 increased by far less – from 76.8% to 81.2%. Older workers are therefore catching up, although employment falls very sharply after age 60 in many countries – more than 22 p.p. between the 55-59 and 60-64 age groups on average and more than 40 p.p. in Austria, France, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia (Figure 6.6 in Chapter 6).

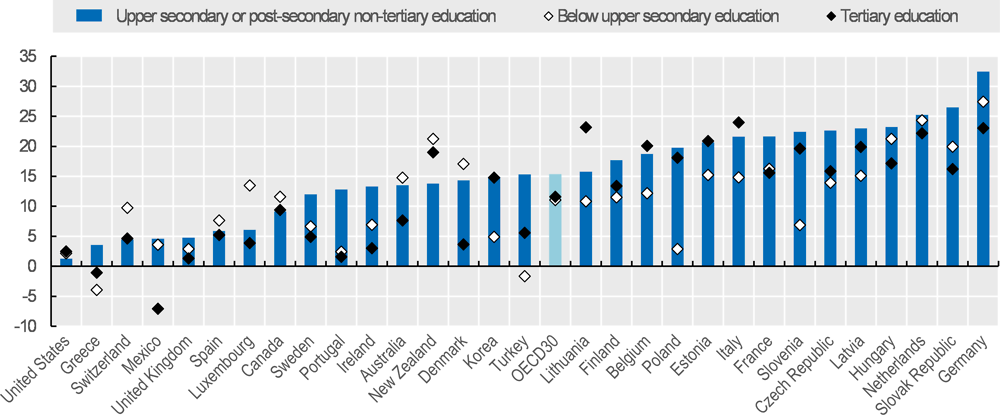

On average, 55-64 year-olds at all levels of educational attainment have experienced a marked increase in employment between 2000-2017, with those with a medium level of education doing better on average than those with low or high levels of education (Figure 1.9). In terms of changes in employment rates, low-educated older workers have lagged significantly behind their high-educated peers in Belgium, Italy, Korea, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia and Turkey, while it is the opposite in Australia, Denmark, Luxembourg and Mexico.

copy the linklink copied!Pension reforms over the last two years

Pension reforms in OECD countries have slowed since the large wave of reforms following the economic and financial crisis. Several measures legislated between September 2017 and September 2019 have even rolled back previous reforms which had aimed at improving the financial sustainability of the pension system.

Overview of recent reforms

Overall, most pension reforms over the last two years focused on loosening age requirements to receive a pension, increasing pension benefits including first-tier pensions, expanding pension coverage or encouraging private savings. The main recent reforms in OECD countries include:

limiting the increase in the retirement age or expanding early-retirement options (Italy, the Netherlands and the Slovak Republic);

raising the retirement age (Estonia);

enhancing work incentives (Belgium, Canada and Denmark);

increasing the level or expanding the coverage of first-tier pensions, the first layer of old-age social protection (Austria, France, Mexico and Slovenia);

increasing benefits while reducing contributions for low earners (Germany);

suspending the adjustment of pension benefits with demographic changes (Spain);

bringing public sector pension benefits more in line with private sector benefits (Norway);

changing the contribution rates (Hungary, Iceland and Lithuania) or expanding contribution options (New Zealand);

expanding the coverage of mandatory pensions (Chile) or developing auto-enrolment schemes (Lithuania and Poland); and,

changing tax rules for pensioners (Sweden).

The annex provides more details about the measures enacted country by country.

Retirement ages and work incentives

Over the last 2 years, Estonia, the Netherlands and the Slovak Republic decided to change the statutory retirement age. Estonia is the only country that raised it, from 63 and 4 months currently to 65 in 2026, and then linking it to life expectancy.

By contrast, the Slovak Republic, which had passed a law in 2012 to start linking the retirement age to life expectancy in 2017, decided to abolish the link, instead committing to raising the retirement age to 64, which will be reached through discretionary increases. In Italy, the 2019 reform introduced the so-called “quota 100” until 2021, i.e. the possibility to retire from age 62 with 38 years of contributions. Combining work and pensions is possible but subject to a labour-income ceiling, which limits work incentives of pension recipients.

In the Netherlands unions and employers struck a deal in June 2019 to reform the pension system, temporarily halting the increase of the retirement age. This means that until 2021 the retirement age will remain 66 years and 4 months. After that its increase will resume, reaching 67 years in 2024 instead of 2021. However, the increase would be slower after 2024, but this part of the deal still needs to pass parliament. More precisely, the link between the retirement age and life expectancy would be limited to an 8-month rather than a one-year increase per year of life-expectancy gains at age 65. In Sweden, the age at which employers can terminate the contracts of older workers according to the Employment Protection Act – the so-called mandatory retirement age – will be raised from age 67 to 68 in 2020 and 69 in 2023. The government has also presented a plan to encourage later retirement, by introducing a recommended retirement age. The recommended retirement age will be linked to the average life expectancy at age 65 and serve as a benchmark for deciding when to retire in order to receive an adequate level of pension. The recommended retirement age will be calculated yearly starting from 2020. In addition, the government has also proposed raising the minimum retirement age for earnings-related pensions from 61 to 62 in 2020 and 63 in 2023, and to then link it to the recommended retirement age, indirectly linking it to life expectancy. From 2026, all other ages in the old-age social security system are also to be linked similarly to the recommended retirement age, which is projected to be close to 67.

Among G20 countries, Russia has raised the statutory retirement age. It will increase by one year every year starting in 2019, from age 60 to 65 for men and from age 55 to 60 for women. The new law also allows men with at least 42 years of contributions and women with at least 37 years of contributions to retire with a full pension 2 years before the statutory retirement age (but not earlier than age 60 for men or age 55 for women). In Brazil, a pension reform passed a final vote in the Senate in October 2019. The reform seeks to increase the pension contribution rate, reduce pension benefits for some workers and establish a minimum age of retirement of 65 for men and 62 for women.4

Some countries boosted incentives to work longer or extended flexible retirement options. Belgium abolished the maximum limit of accrual years. Previously no accrual occurred after 45 years of contributions. Canada increased the earnings exemption for the income-tested component of their first-tier benefit (GIS), to allow low-income seniors to work without reducing their entitlement. Denmark decided to grant a one-off lump sum of DKK 30,000 (7% of the average wage) if someone is employed for a minimum of 1560 hours during 12 months after reaching the statutory retirement age, which is currently 67 years. Estonia expanded flexible retirement options, allowing combining pensions and labour income three years before the legal retirement age.5 It is also possible to take out only half a pension, which makes later pension payments higher compared to taking the full pension.

Raising the statutory retirement age is typically one key measure to enhance financial sustainability without lowering pensions despite improvements in longevity. Depending on the design of each system, it can even increase retirement income relative to past earnings, or at least limit its decrease. In defined benefit (DB) systems, for example, higher retirement ages lead to more contributions and tend to lower pension expenditure by shortening retirement periods. At the same time, prolonging working lives typically enables people to accrue additional pension entitlements, raising benefits.

Normal retirement ages – the age at which individuals are eligible for retirement benefits from all pension components without penalties, assuming a full career from age 22 – differ significantly among OECD countries. In 2018, the normal retirement age was 51 for men and 48 for women in Turkey whereas it was 67 in Iceland, Italy and Norway for both men and women (Figure 1.10 and Figure 4.4). Given current legislation, the future normal retirement age (for men) will range from 62 in Greece, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Turkey to 74 in Denmark.6 On average across OECD countries, it will increase from 64.2 in 2018 to 66.1 in the future – i.e. for someone having entered the labour market in 2018 and therefore retiring after 2060 (Figure 4.6 in Chapter 4). Over the same period, life expectancy at 65 is expected to grow by 4.1 years.

The normal retirement age for people entering the labour market now is set to increase by more than 5 years, in Denmark, Estonia and the Netherlands (and Turkey but from a low level) compared to individuals retiring now (Figure 1.10). Meanwhile, sixteen OECD countries have not passed legislation that will increase the normal retirement age. Based on current legislations, the future normal retirement age is below 65 years only in Greece, Luxembourg, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and Turkey. Moreover, all non-OECD G20 countries will have retirement ages of 65 years and below. In Saudi Arabia the normal retirement age will be as low as 47 years.

Taking a long-run perspective, retirement ages followed a slow downward trend from the middle of the 20th century, reached a trough in the mid-1990s and have been drifting upward since then, recovering their 1950 level only recently. In the meantime (i.e. since the middle of the 20th century) period life expectancy at age 65 increased by about 6½ years on average, resulting in pressure on pension finances. For men with a full, uninterrupted career born in 1940 and those born in 1956 (who retire about now), the OECD average normal retirement age has increased by 1.3 years (OECD, 2019[7]), implying that those who are born one year later have a normal retirement age which is 1 month higher.

In half of OECD countries, the normal retirement age has been the same for men and women, at least for people born since 1940. In the 18 countries where there was a gender difference, 6 have already eliminated it and 7 are in the process of eliminating it (Austria, the Czech Republic, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Slovenia and the United Kingdom). Only Hungary, Israel, Poland, Switzerland and Turkey will maintain a lower retirement age for women now entering the labour market, based on current legislations, although Turkey will phase out the gender difference for those entering the labour market in 2028 (Chapter 4).7

Even with rising retirement ages, the time spent in retirement as a share of adult life is expected to increase in the vast majority of OECD countries. The cohort entering the labour market about today is expected to spend 33.6% of adult life in retirement compared with 32.0% for the cohort retiring on average today (Figure 1.11). The only countries in which the share of time spent in retirement is expected to decrease based on current legislation are Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Italy, Korea, the Netherlands and Turkey. In all other countries the retirement length increases by 3.1 percentage points on average, representing about 10% of the share spent in retirement.

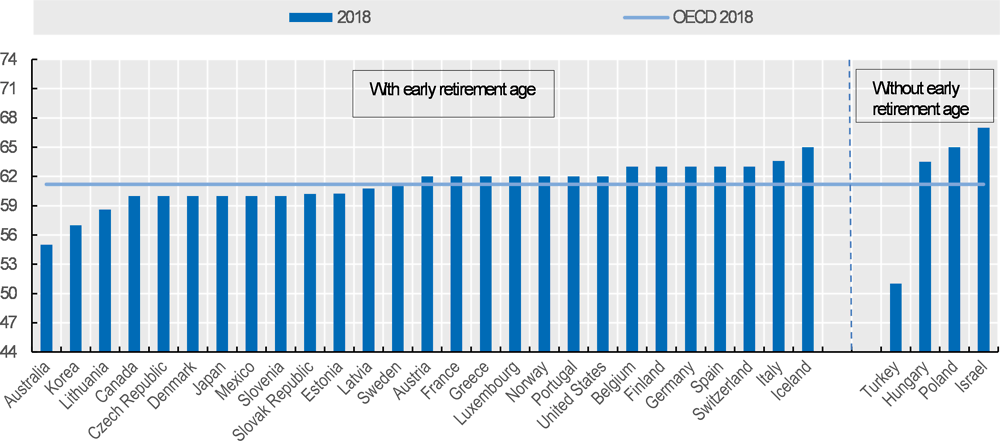

Reforming early retirement options also significantly influences effective retirement ages. For someone entering the labour market at age 22 the early retirement age was 61.2 years in 2018 on average among the 31 OECD countries that have a specific minimum retirement age for mandatory earnings-related pensions (Figure 1.12). Twenty-seven countries had an early retirement age lower than the normal retirement age. Tightening eligibility conditions for early retirement either by increasing the minimum retirement ages or by making early retirement more penalising has been one major pension policy trend over the last decades. Early retirement ages have been rising by a little over one year between 2004 and 2018.

Over the last two years, two countries, Italy and Portugal, have eased early-retirement conditions.8 In 2019, Italy suspended until 2026 the automatic links with life expectancy of both career-length eligibility conditions for early retirement (42.8 and 41.8 years for men and women, respectively), and the statutory retirement ages for some workers only, including those in arduous occupations. In addition, the reform introduced the “quota 100” (see above) and the so-called ”women’s option” which allows women to retire at age 58 with 35 years of contributions if they fully switch to the NDC (notional or non-financial defined contribution) benefit calculation.9 These measures partially and temporarily reversed the 2011 reforms that substantially tightened conditions to access pensions (see Section 4).

Portugal expanded the eligibility of penalty-free early retirement from age 60 to individuals with long career who began contributory employment at age 16 or younger and have at least 46 years of contributions while the statutory retirement age is 66 years and 4 months. France and Germany adopted similar measures previously (OECD, 2017[11]). In addition, from 2019, the sustainability factor which specifically and heavily penalises early retirement in Portugal – beyond the normal penalty for early retirement of 0.5% per month of early retirement – will not be applied for workers aged 60 or more and having a contribution record of at least 40 years at age 60.

First-tier pensions

Mexico reformed its old-age safety net by introducing a new universal pension programme (Programa Pensión para el Bienestar de las Personas Adultas Mayores) for those aged 68 or older. The programme replaces the targeted old-age social assistance programme for those aged 65 or above who do not receive a contributory pension above MXN 1,092 (Programa Pensión para Adultos Mayores, PPAM). Those aged 65-67 who have been receiving the PPAM pension will automatically receive the new universal pension. Compared with PPAM, the benefit level was substantially increased, by almost 120% and is no longer means-tested against pension income. The objective is to expand the eligible part of the population, reaching 8.5 million people in 2019 against 5.5 million people in 2018 with PPAM. However, the increase in the benefit level and the elimination of the means-testing comes with the increase in the eligibility age.

In 2019, Italy introduced the so-called citizen’s pension on top of the existing safety-net benefits for older people. This new safety-net level comes at EUR 630 (24.2% of the average wage compared to 18.8% previously, i.e. a large increase of almost 30%) for a single person. In France, from April 2018 to January 2020, the old-age safety net (ASPA) will be increasing by about 12.5% in nominal terms. Austria decided to introduce a top-up for long contribution periods (generally referred to in OECD wording as a minimum pension scheme except that the Austrian scheme is means-tested). Single insured persons with 30 (40) years of contribution will receive at least EUR 1.080 (1.315), i.e. 29% (36%) of the gross average wage. Couples will receive a higher top-up. Slovenia introduced a new minimum pension level for workers with a full career (40 years). The benefit was EUR 516 per month (31.5% of the average wage) in 2018 compared to EUR 216 per month (13.2% of the average wage) for workers with a 15-year history.

Pension benefits from earnings-related schemes

A few countries decided to adjust benefit levels in earnings-related schemes. In Spain, measures decided in the 2013 reform to ensure the financial sustainability of the system were suspended. The Revalorisation Pensions Index (IRP), which indexed pensions in payments since 2014 based on the financial balance of pensions and of the Social Security system, was suspended. Pensions in payment were increased in line with the CPI at 1.6% in both 2018 and 2019 while they would have only increased by 0.25% had the IRP formula been applied. The sustainability factor, which was supposed to start being applied in January 2019 to adjust initial pensions based on changes in life expectancy, was suspended until 2023. In addition, the replacement rate for survivor pensions was raised from 52% to 60% of the deceased’s pension for beneficiaries aged 65 or older. A commission will determine how to proceed with both the sustainability factor beyond 2023 and the new indexation mechanism.

Germany took measures in favour of low earners. It lowered the effective contribution rates for low earners, by increasing the ceiling of monthly earnings, from 21 to 32% of gross average wages (EUR 850 to EUR 1300), below which reduced contributions apply. At the same time, the reduced contributions generate full pension entitlements compared with partial entitlements before. In France, social partners agreed to rules for the indexation of the value and cost of points until 2033 within the mandatory occupational scheme. The point cost used to determine the number of points acquired by contributions will be indexed to wage growth, while the point value which directly determines the benefit levels will be indexed to price inflation until 2022 and to wage growth minus 1.16 percentage points between 2023 and 2033.

Norway now better aligns pensions for public-sector workers with the rules applying to the private sector. Norway applied a new rule to the Contractual Early Retirement Schemes (AFP) for public-sector employees born from 1963. The AFP in the public sector, which had been a subsidised early-retirement scheme for those aged between 62 and 66, was changed into a lifelong supplement to the old age pension, in line with the private sector.10 In addition the public-sector pensions will be based on life-time earnings instead of last earnings and of achieving a full pension after 30 years of contributions. Over the last decades, OECD countries have been closing down special regimes, and, for example, schemes covering public-sector and private-sector workers are fully integrated or will progressively be in Israel, Japan, New Zealand and Southern European countries (OECD, 2016[8]).

Future theoretical replacement rates are computed by the OECD in order to distinguish key output of pension systems across countries. One main indicator is the net replacement rate for the best-case scenario assuming a full career starting at age 22 in 2018 until reaching the country-specific normal retirement age. The normal pensionable age is defined as the age at which individuals can first withdraw their full pension benefits, i.e. without actuarial reductions or penalties. This theoretical replacement rate is equal to the pension benefit at the retirement age as a percentage of the last earnings.

Looking ahead, pension replacement rates display a large dispersion across countries. Figure 1.13 shows theoretical net pension replacement rates across OECD and G20 countries for an average-wage worker. Net replacement rates from mandatory schemes are on average 59% and range from close to 30% in Lithuania, Mexico and the United Kingdom to 90% or more in Austria, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal and Turkey at the normal retirement age. Based on standard OECD assumptions used for pension projections (Chapter 5), future net replacement rates will be low even for the best case - under 40% - also in Chile, Ireland, Japan and Poland. Among countries with significant coverage from voluntary private pensions – Belgium, Canada, Germany, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States – contributing to a voluntary pension for the whole career boosts future replacement rates for average earners by 26 percentage points on average based on the modelling assumptions used in the OECD projections (see Chapter 5 for more detail). Contributing to voluntary pensions from age 45 would increase them by about 10 percentage points on average.

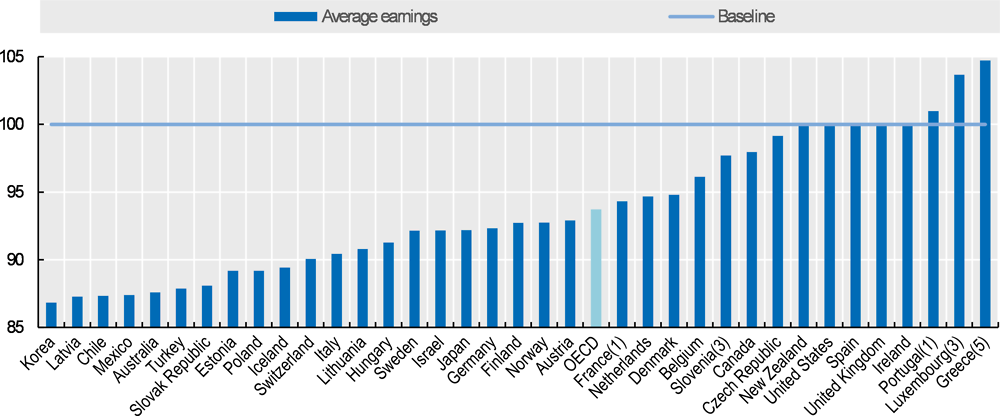

Interrupted careers usually lead to lower pensions, but entitlements are not equally sensitive to career breaks across the OECD. Average-wage workers who experience a 5-year unemployment spell during their career face a pension reduction of 6.3% in mandatory schemes compared to the full-career scenario discussed above on average in the OECD (Figure 1.14). A one-to-one relation between earnings and entitlements would imply the impact to be around 13% (Chapter 5). This means that instruments such as pension credits for periods of unemployment cushion slightly more than half of the impact of the employment shock on pension benefits on average. The loss exceeds 10% in Australia, Chile, Estonia, Iceland, Latvia, Korea, Mexico, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Turkey. Conversely, in Ireland, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, there is no impact of such career breaks on pensions from mandatory schemes, which only include a basic pension in these countries.11 In Spain and the United States, a 5-year career break does not influence pension benefits either, as full benefits in the earnings-related scheme are reached after 38.5 and 35 years of contributions, respectively.

Contributions

Contribution rates have been raised in Iceland and Switzerland over the past two years. Iceland increased the contribution rate paid by employers in mandatory occupational pensions from 8% to 11.5%. Switzerland increased the contribution rates of public pensions (AVS) by 0.3 points. In addition, government subsidies to its financing were increased from 19.6% to 20.2% of total revenues.

On the other hand, Hungary gradually reduced the pension contribution rate paid by employers from 15.75% in January 2018 to 12.29% in July 2019. Lithuania has shifted social security contributions from the employer to the employee. The employer’s contribution rate was reduced from 31% percent of monthly payroll to 1.5% percent, and the employee contribution rate rose from 9% of monthly earnings to 19.5%, while the remaining shortfall will be financed by taxes. At the same time the earnings ceiling is slowly lowered from 10 times the average wage in 2019, to 7 times in 2020 and to 5 times from 2021. Germany set new minimum and maximum pension contribution rates. The total contribution rates cannot rise above 20% or fall below 18.6% through 2025, while before the maximum contribution rate was 20% until 2020 and 22% from 2020 to 2030.

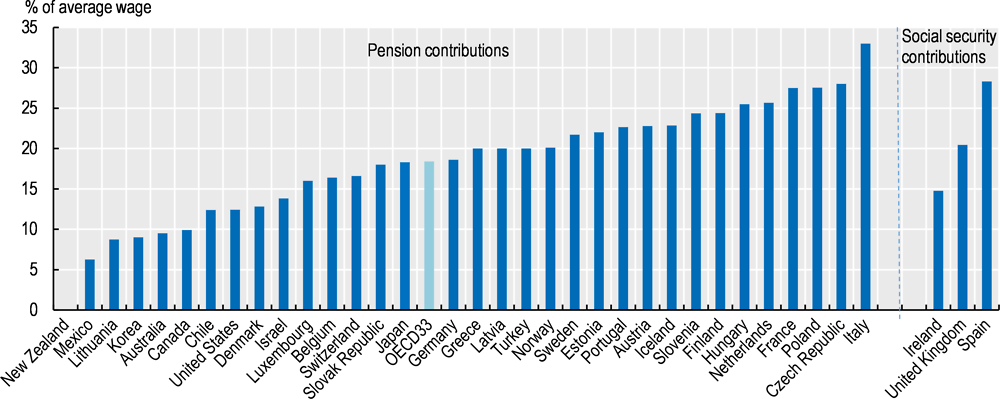

Mandatory pension contribution rates differ widely among OECD countries. New Zealand finances its basic pension through taxes and therefore the mandatory pension contribution rate is zero. At the average wage, in 2018, total effective pension contribution rates equal 18.1% on average in the OECD (Figure 1.15). Contribution rates are the lowest, below 10%, in Australia, Canada, Korea, Lithuania and Mexico while the Czech Republic, France, Italy and Poland have contribution rates of 27% or higher. Spain also has high contribution rates, but these contributions extend beyond pensions and cover all social security schemes except unemployment insurance.

As for voluntary pension plans, New Zealand expanded the choice of contribution rates for KiwiSaver. From April 2019, people may choose a contribution rate of 6% or 10%, adding to the existing options of 3%, 4% and 8%. Similarly, Norway introduced a new scheme with stronger incentives for retirement savings by allowing individuals to pay more contributions while receiving an income tax deduction.

In Estonia a plan has been presented to parliament in August 2019 to replace mandatory private pensions by auto-enrolment schemes. If a participant opts out of the private pension plan, the employer’s contributions will go to the PAYGO points scheme, generating a higher total value of accumulated points, while the employee will keep his or her contributions. This means that in that case net wages will increase while both total mandatory contribution rates and total pension entitlements will be lower. On opting out someone can ask to be paid all the previously accumulated assets of the private pension plan as a lump sum.12

Coverage

Over the last two years, only Chile expanded the coverage of mandatory earnings-related pension schemes. Between 2012 and 2018, Chile has tried to include the self-employed through auto-enrolment into the scheme that is mandatory for employees, but the majority of them opted out. Hence, since 2019 pension contributions have been made compulsory for the self-employed who issue invoices, except for older workers and low-income earners (Chapter 2).

The coverage of voluntary schemes was expanded in Belgium, Germany, Lithuania, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway, Poland and Turkey. In Belgium and Luxembourg, the extension applies to the self-employed. In Belgium, a new private pension was introduced for the self-employed in 2018 on top of the two that have existed based on a relatively low ceiling on pensionable earnings. Participants will receive a 30% tax credit on their contributions, with no explicit ceiling. A similar option is provided for employees who do not have access to an occupational pension provided by their employer. In Luxembourg, access to voluntary pension schemes previously only available to dependent employees has been extended to the self-employed with similar conditions to employees.

From 2018, Germany allowed employers to offer defined contribution plans without guaranteed minimum retirement benefit if employees agree as part of the collective bargaining process. New Zealand allowed people aged over 65 to join the voluntary saving scheme (KiwiSaver) from 2019, while Turkey extended automatic enrolment of private pensions (introduced in 2017) to smaller employers (with 5-99 employees). Poland introduced a new defined contribution occupational pension plan with auto-enrolment, which will fill part of the gap that emerged after the multi-pillar pension system was dismantled in 2014. Employers that do not already provide a voluntary scheme to their employees are required to offer such a plan. Lithuania transformed the previously voluntary funded pension scheme, introduced in 2004, into an auto-enrolment scheme for employees younger than 40 years.13

Finally, in July 2019 the European Union established a voluntary retirement savings programme (the Pan-European Personal Pension Product) in order to boost retirement savings and strengthen capital markets across the EU. The programme allows EU residents to participate in individual accounts that are governed by the same basic rules and are portable across all member countries.

Others

Two countries changed the tax rules for pensioners. In 2019, Sweden extended the earned-income tax-credit threshold to pensions from SEK 17000 to SEK 98000 (between about 45% and 260% of the gross average wage). In 2018, France raised an income tax (CSG) rate applying to pensioners from 6.6% to 8.3% - the normal rate applying to wages increased from 7.5% to 9.2% - while deciding in 2019 to exempt about 30% of retirees with the lowest income.

In September 2018 the Swedish Pension Agency tightened the regulations for pension funds administering the mandatory earnings-related funded part of the system (PPM funds). The new regulations require, among other things, at least SEK 500 million of funds outside the PPM and a minimum of 3 years of relevant experience. The funds that do not meet the new requirements were to be removed from the PPM platform. As a result, in January 2019, 553 funds remained available while 269 were deregistered. Furthermore, the investment rules for the four main pension buffer funds were eased.14 In private pensions in Turkey, in order to spur competition and raise performance among asset management companies, a 40% cap has been introduced on the portion of a pension company's portfolio that an asset management company can manage.

To reduce administrative costs for pension providers, the Netherlands introduced new pension rules in occupational schemes that allow pension providers to automatically transfer total entitlements of certain participants, who have limited pension entitlements, to the new pension provider in case of a change of employer and pension provider. In addition, a large overhaul of the occupational pension system is planned to be introduced by 2022. A deal between unions, employer organisations and the government has been struck in June 2019 aiming to: introduce more defined contribution (DC) elements in the occupational pension system (i.e. pension entitlements will be more sensitive to pension funds’ returns), limit the increase in the retirement age while maintaining the link to life expectancy; and, introduce special rules for people in arduous jobs.

The French government created the High Commission for Pension Reform in September 2017. Its mission is to prepare the reform introducing a universal pension points system (Boulhol, 2019[9]). The High Commission published its recommendations for the implementation of the new pension system in July 2019. The proposed system would constitute a major overhaul of the French pension landscape, which is highly fragmented. It would be based on common rules for contributions and the calculation of pension entitlements, would drastically simplify the current system while reducing the sensitivity of financial balances to trends in labour productivity. Concertation with the main stakeholders is continuing to prepare the legislative phase, with the objective of having a law voted in 2020.

Mounting pressure to backtrack and not deliver on previous reforms

Among the most salient pension policies over the last two years are reforms backtracking and not implementing previously legislated policies. These include measures decided by Italy, the Netherlands, the Slovak Republic and Spain to alter automatic adjustments to life expectancy or other demographic changes. More precisely, as discussed above, Italy introduced the “quota 100” measure, facilitated early retirement and suspended automatic links. The Slovak Republic has stopped the link between the retirement age and life expectancy in 2019 and put a cap at 64 years on the former instead, while Spain suspended the automatic adjustments affecting the initial pension at retirement and indexation of pensions in payment. The Netherlands deferred the increase in the retirement age in the medium term and plans to opt for a slower link in the long term. The new link would avoid that all life expectancy gains translate into increases in the retirement age. In Denmark too, discussions to revise the link between the retirement age and life expectancy are ongoing. However, neither Denmark nor the Netherlands plan to completely abolish the link.

Over the last four years, Canada, the Czech Republic and Poland also decided to reverse previously adopted reforms (OECD, 2017[10]). Canada chose not to implement the planned increase to age 67 for the basic pension and the old-age safety net, while the Czech Republic decided to no longer increase the pension age beyond 65. Poland reversed the planned increase to 67, with retirement ages dropping back to 65 for men and 60 for women.

During and right after the economic crisis, improving public finances was at the centre stage. For example, between 2011 and 2014, most pension measures in European countries consisted in the containment of pension spending and the prolonging of working life through raising the retirement age or tightening early-retirement rules. When the economic situation improves, public finance pressure eases and there might be no or less need to maintain measures dictated by short-term difficulties. Of course, the situation is not always that simple as in some cases short-term difficulties are an impetus for needed long-term reforms. In some countries, tensions generated by the global financial crisis actually exacerbated and highlighted structural weaknesses.

Not implementing legislated measures might raise serious concerns when the initial reforms are meant to address issues related to long-term developments. Ageing trends are a prime example of a long-term phenomenon, which are not only here to stay but as shown in Section 2 have started to accelerate in many countries. To face this challenge, many measures were taken to improve financial sustainability. That is, backtracking might threaten macroeconomic stability. In these instances, not implementing the corresponding reforms generates a need for alternative measures, as there are indeed different ways to ensure financial sustainability. Increasing retirement ages is always unpopular, for reasons that everyone understands well. Some recent backlashes have arisen because applying the agreed rules is raising discontent. However, to simplify the matter, in PAYGO pensions, dealing with increasing longevity requires working longer, lowering pension benefits, raising financial resources or a mix of these; each alternative typically receives limited public support.

The backlash against passed reforms also potentially reflects reform fatigue or changing political landscapes. The sometimes strong impact of measures tightening social programmes and the dramatic rise of anti-establishment parties have further contributed to the growing opposition against fiscal discipline and the related pension reforms, which in turn alters the political equilibrium and could destabilise the compromise that supported pension reforms in earlier stages. Pension policy is always at risk of being used as a tool for short-term political gain, leading to a demand for an increase of pension benefits or a reversal of previous reforms (Natali, 2018[11]).

However, there should be a long-term strategy to secure retirement income. Governments have to take steps constantly and steadily to ensure that pension policies deliver secured retirement incomes in financially sustainable and economically efficient ways irrespective of the economic and political conditions.

In particular, opposition against automatic adjustment mechanisms has been on the rise. Demographic, economic and financial trends affect the financial sustainability of standard PAYGO pensions and the solvency of funded DB schemes. They require recurrent discretionary adjustments, which hurt confidence in the pension system and are politically costly. While pension systems cannot be put on autopilot, linking some parameters to key variables can drastically reduce the need for repeated measures. Moreover, automatic rules help resist the temptation to make decisions that might be popular but ultimately unsustainable, such as lowering the retirement age from not a particularly high level while life expectancy increases.

As an example, the link to life expectancy provides a predictable rule for adjusting future benefits at a given age or for raising the retirement age as longevity increases. Also, while life expectancy trends are predictable they are subject to some uncertainty, and such rules are attractive because their effects are conditional on actual demographic changes.

One main criticism usually made against automatic adjustment mechanisms is that they would be anti-democratic: they would prevent future governments from adopting different measures according to their popular mandate than the one implied by the automatic rules that are in place. This is a limited interpretation of the objective of automatic adjustment mechanisms. If a government has the political capital to do so, it can always change the rules in order for them to better fit its political agenda. In addition, subjecting pension decisions to frequent policy changes could also result in very low benefits in times of budgetary pressure, making the adjustment path more erratic and potentially amplifying the magnitude of economic cycles.

copy the linklink copied!Long-term trends in pension reforms

Over the last 50 years, pension rules have changed in all OECD countries. Countries have moved to improve financial sustainability given the challenges triggered by population ageing. Some reforms were systemic, changing the whole nature of a system, while others were parametric. Pension systems have become more individualised with pension benefits becoming more tightly linked to earnings. The reforms may cause marked differences in pension eligibility and benefit levels across generations.

From defined benefits to defined contributions

Pension systems in the past were dominated by PAYGO DB schemes where pension benefits typically depend on the number of years of contributions, rates at which pension entitlements accrue (accrual rates) and a measure of individual earnings (reference wage). Especially in the second half of the 20th century, OECD countries established or extended PAYGO DB schemes. At the time, population growth was fast and the economy developed quickly, both of which increase internal rates of return of PAYGO systems. One attractive feature of PAYGO pension systems is that they allow for providing pension benefits to older people who did not contribute.

In a number of OECD countries, including Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States, funded occupational pensions built up over time in addition to PAYGO schemes. With the exception of Denmark, these schemes were also DB, or as in Switzerland had elements of DB schemes incorporated in DC plans.

Over the last decades, however, there had been a paradigm shift from DB to DC schemes, as a way of dealing with the financial sustainability issues of PAYGO pensions, especially given population ageing. Chile in 1981 and Mexico in 1997 replaced their public PAYGO DB schemes by private funded mandatory DC schemes. More recently, as a complement to their public pension schemes, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Sweden introduced mandatory private funded DC schemes or raised the contribution rates that fund them. In the Netherlands, consecutive adjustments of pension rules have rendered the funded DB scheme more of a hybrid DB-DC system; as discussed in the preceding section there are far-reaching plans to further individualise accounts.15 In other countries, like the United States, the share of DB plans among occupational pensions has slowly declined in favour of more DC plans (OECD, 2016[8]).

However, more recently, some countries, like Poland and Hungary, abolished their mandatory funded DC pension schemes, while the Slovak Republic has switched between mandatory funded DC pension, auto-enrolment and voluntary pensions (currently it can be decided before age 35 whether one-third of mandatory contributions go to the points or funded DC scheme). Starting from a PAYGO system, building up a funded component involves high transition costs (Boulhol and Lüske, 2019[12]). Pension funding needs to be sufficiently high not only to pay current pensions within the PAYGO scheme, but also to accumulate new entitlements through savings in the funded component. Especially in times of public finance pressure, such transition costs can become problematic as neither current workers nor current retirees can carry such a high financial burden without major sacrifice while the governments’ capacity to finance the transition through higher debt levels may be limited. While diversifying the sources of financing pensions remains a key argument supporting multi-pillar systems, the current context of low long-term yields might call for revisiting the trade-offs between PAYGO and funded components (Boulhol and Lüske, 2019[12]).

Akin to the switch to funded DC plans, in the 1990s, Italy, Latvia, Poland and Sweden radically reformed their public PAYGO pension system, shifting from defined benefit (DB) to notional (non-financial) defined contribution (NDC). Norway did so in 2011. The move to NDC has been part of the trend towards more individualised pension benefits. The core of the NDC design mimics funded DC schemes with strong links between individual lifetime contributions and benefits. Moreover, incentives to work longer with increasing longevity are embedded in the schemes: for given accumulated contributions, rising life expectancy reduces pensions at any given age.

Tightening the link between earnings and benefits

Some countries have also tightened the link between earnings and benefits within their PAYGO DB schemes. For example, Estonia, Lithuania and the Slovak Republic switched from traditional DB to points systems, in which benefits are proportional to lifetime contributions. As discussed above, France plans to introduce a universal points system, while in Belgium the government made plans to investigate the implementation of separate points schemes for private-sector workers, public sector-workers and the self-employed.

One additional factor that greatly influences the link between lifetime earnings and pensions is the measure of individual earnings used in the benefit formula. The exact way this reference wage depends on the past earnings of individuals varies among countries; while a generic DB scheme uses lifetime average earnings, with past earnings uprated in line with the average-wage growth, other measures could be used such as a the last or best years of earnings. Some countries including Austria, Finland, France, Hungary, Portugal and Spain lengthened the reference earnings periods. Currently most countries use lifetime earnings for calculating pension benefit, with only Austria, France, Slovenia, Spain and the United States, and Portugal to a lesser extent, not taking into account the whole career – although Austria will do so progressively from the cohort born in 1955 (Figure 1.16).16

Automatic adjustment mechanisms

Automatic adjustment mechanisms, in which pension system parameters are automatically adjusted to changes in various indicators such as life expectancy, other demographic ratios or funding balances, have become part of a standard toolset in pension policies. Automatic adjustment mechanisms are present in half of OECD countries (Table 1.1). In some cases, they do not cover all the components of a pension system. Hence, their overall significance in a given country depends on the structure of the pension system (last column in the table).

Funded defined contribution schemes

Funded defined contribution (FDC) schemes automatically transfer to pensioners the risk of the impact of changes in longevity across generations as accumulated pension investments have to cover longer average retirement periods at a given retirement age. These schemes thus include built-in automatic adjustments of pension levels to life expectancy. When pension entitlements are annuitised longer lives mean more expensive annuities, and therefore lower monthly benefits even if individual longevity risks are still shared among all recipients. In the case of lump-sum payments all individual longevity risk is born by the individual. With longer lives, these lump sums have to finance consumption over a period which length is longer on average and uncertain individually.

Nine OECD countries have mandatory FDC schemes (Table 1.1, column 1). While financial sustainability is typically ensured in funded DC schemes, pension adequacy might be at risk without further automatic adjustments. The level of benefits is likely to fall gradually if people are allowed to retire at the same age unless workers choose by themselves to postpone retirement. In addition, many people tend to retire as early as possible and might make mistakes in assessing their future financial needs, especially in times when lives become longer. Hence, even in FDC schemes, either the minimum retirement age or pension contributions should be linked to life expectancy to help achieve adequate pensions over time.

Notional defined contribution schemes

While NDC schemes are PAYGO, the computation of pensions are very similar to the pricing of annuities in funded DC plans, which generates an automatic link between benefits and life expectancy. NDC schemes typically do not allow withdrawing pension entitlements in the form of lump sums. Italy, Latvia, Norway, Poland and Sweden are the five OECD countries with NDC schemes, thus incorporating this automatic link (Table 1.1, column 2).17 However, these countries differ in terms of the chosen notional interest rate used to uprate entitlements. If the notional interest rate does not account for long-term trends in the number of contributors, as in Sweden, an additional balancing mechanism might be needed to ensure financial sustainability (see below).

Linking benefits to life expectancy in defined benefit schemes

Relatively recently, Finland, Japan and Spain have introduced sustainability factors in their DB pensions (Table 1.1, column 3) to ensure financial sustainability and in some cases to prevent a large drop in pension levels. These sustainability factors are automatic adjustment mechanisms, linking pension benefits to life expectancy (OECD, 2017[10]). In Finland and Spain this only affects initial benefits while in Japan it also affects pensions in payment. Portugal also has a sustainability factor, but it only applies to early retirement (OECD, 2019[13]).

In Finland, since 2010 the initial level (at retirement) of PAYGO earnings-related pensions has been adjusted to take into account changes in life expectancy at age 62. The life expectancy coefficient lowers initial pensions by the ratio of average life expectancy at 62 in 2005-2009 to average life expectancy at 62 in the 5 years prior to retirement. The life expectancy coefficient was 0.957 in 2019, and is projected to be equal to 0.867 in 2064 (the year in which someone entering the labour market now will be allowed to retire).

In Spain the sustainability factor was supposed to adjust new pension benefits by a factor based on life expectancy at the age of retirement, measured two years prior to retirement, divided life expectancy at the same age in 2012. This measure was planned to go into force in 2019. However, it has been suspended until 2023. A commission will determine how to proceed with the sustainability factor beyond 2023.

In Japan, the adjustment mechanism of pension benefits, introduced in 2004, is based on changes in both the number of contributors and life expectancy, called macroeconomic indexation. The sustainability factor is the sum of two components: a life-expectancy index (currently -0.3%) and the average change in the number of contributors over the past 3 years (0.1% in 2019). However, this adjustment mechanism is not applied at times of negative inflation. Hence, a catch-up system was introduced in 2018, which carries over downward benefit revisions in years of negative inflation to later years. In 2019, as both price and wage increased, the macroeconomic indexation was applied, and in addition the unrealised benefit reduction in the previous year was reflected through the carryover mechanism.18

Linking benefits to the financial balance, demographic ratios or the wage bill

In Estonia, Germany, Japan (as explained above), Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden, benefits are linked to the financial balance of the pension system, to demographic ratios or the wage bill. All pensioners, and not just new pensioners, are affected.

In Germany the sustainability factor measures the change in the number of contributors relative to the number of pensioners.19 It has been in place since 2005 and is used to index the pension point value (Table 1.1, column 4). The sustainability factor in 2018 was positive, increasing pensions by 0.3%. From 2020 it is projected to be negative with an average reduction of pensions by 0.5% per year until 2032.20 However, benefits cannot be reduced in nominal terms as a result of the adjustments. In that case, the downward adjustment from the sustainability factor is only applied if other factors in the pension point value (such as wage growth) are positive. Unapplied negative adjustments are, however, carried over to later years as it happened in the past. In Lithuania both the value of the pension point and of the basic pension are linked to changes in the wage bill. If the wage bill falls in nominal terms (which will cause a drop in contributions) the indexation of pension benefits and entitlements does not apply. In Estonia, the value of the pension point is also linked to contribution revenues.

In Sweden, there is also an automatic adjustment of pensions to the balance ratio of the NDC scheme as the embedded automatic link to life expectancy is not enough in itself (Boulhol, 2019[9]). The Swedish Pensions Agency calculates a balance ratio dividing notional assets (the assets of the buffer fund plus contribution revenues) by liabilities (accrued notional pension entitlements and pensions in payment). If a deficit is identified a brake is activated, reducing the notional interest rate below the wage growth rate in order to help restore solvency by both limiting accumulation in notional accounts and reducing indexation of pensions in payments.21 When rebalancing is achieved, any surplus can be used to boost the interest and indexation rates during a catch-up phase. Sweden experienced some difficulties in applying the brake rule during the Great Recession, and revised it to avoid sharp adjustments. Overall, while the Swedish mechanism was put to the test, it proved resilient to such a huge economic shock, only requiring a small adjustment, with its broad principles remaining largely unchallenged.

In the Netherlands a similar mechanism is in place for funded defined-benefit schemes. The uprating of pension entitlements and indexation of pensions in payment are directly linked to the funding ratio. In case of persistent underfunding even pension benefit levels are directly linked to the funding ratio. A pension fund can decide to increase pension benefits and past pension entitlements in nominal terms only if it has a funding ratio of more than 110%.22 Funding ratios below 110% lead to a freeze in pension benefits and pension entitlements. Funding ratios below 104.2% for more than 5 years lead to cuts in entitlements and benefits. The funding ratio in that case should be brought back to 104.2%, with associated cuts being spread up to 10 years. In Luxembourg pensions in payment are typically indexed to both prices and wages. However, indexation is limited to prices if the share of annual expenditure divided by the contribution base exceeds 24%.23 In Spain, the Revalorisation Pensions Index (IRP), which indexed pensions in payments since 2014, based on total contributions, the number of pensioners the financial balance of the Social Security system, was suspended. Pensions in payment were increased in line with CPI inflation at 1.6% in both 2018 and 2019 while they would have only increased by 0.25% had the IRP formula been applied.

Linking the retirement age to life expectancy

Rather than increasing retirement ages according to a predetermined schedule, as is done in some countries, some other countries have gone further and linked retirement ages to life expectancy. This is the case in Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands and Portugal (Table 1.1, column 5). Greece also linked its statutory retirement age to life expectancy. However, it will still be possible to claim a full pension (i.e. without penalty) at any age with 40 years of contribution, implying the normal retirement age projected by the OECD is fixed at 62. Italy and the Slovak Republic had linked their retirement ages to life expectancy but recently backtracked on those reforms with the Slovak Republic abolishing the link altogether and Italy temporarily suspending it for some occupations.

The exact way countries link their retirement age to life expectancy differs. Denmark, Estonia, Italy and the Netherlands link their retirement age one-to-one to life expectancy, meaning that a one-year increase in life expectancy at 65 (60 for Denmark) leads to a one-year increase in the retirement age.24 This might be needed to ensure financial sustainability, but it basically implies that all additional expected life years are spent working, while the length of the retirement period is constant: this leads to a steady decline in number of years in retirement relative to those spent working. Italy suspended until 2026 the automatic links with life expectancy of both career-length eligibility conditions for early retirement (42.8 and 41.8 years for men and women, respectively), and the statutory retirement ages for some workers only, including those in arduous occupations. In Denmark parliament has to vote every 5 years to uphold this link.

In Finland and Portugal the statutory retirement age increases with two-thirds of life expectancy at 65; Sweden plans to implement a similar link. In Finland, this is done with the expressed goal of keeping the ratio of expected time in retirement to time spent working constant. In addition in Portugal, someone with more than 40 years of contributions can retire 4 months earlier for each year over 40 years of contributions. This implies that only half of life expectancy gains are reflected in the normal retirement age (OECD, 2019[13]).

Not all links to life expectancy are by themselves ensuring the financial sustainability of PAYGO DB systems of course. First, for example, working-age population growth driven by past fertility rates matter irrespective of longevity. Second, in most countries additional years of work also mean additional pension entitlements. Yet, in DB schemes, these additional entitlements are typically not actuarially neutral, implying that in the long term increasing the retirement age tends to generate net savings for the pension provider. As long as the pensioner-to-contributor ratio stays constant, a stable replacement rate can be financed by a stable contribution rate in a sustainable way. However, not raising the retirement age in line with improvements in life expectancy tends to lead to a deterioration of the financial balances due to the increase in that ratio, unless lower replacement rates or higher contribution rates offset the impact of demographic changes.

In addition, inequality in life expectancy raises complex issues for pension policy. It is important here to distinguish static and dynamic considerations. A generic pension system without obvious redistributive features (e.g. a simple DB system based on a given accrual rate or a funded DC system with annuitisation based on common mortality tables) might look neutral but is actually regressive: people with higher incomes tend to have longer lives and therefore to benefit from higher pensions for a longer time; this is financed in part by those who die early, who tend to be those with lower lifetime income. This effect is potentially large given the level of socio-economic differences in life expectancy (OECD, 2017[1]). It implies that inequality in life expectancy strengthens the case for redistributive components within pensions systems.

The same mechanism means that increasing the retirement age is by itself regressive: as low-income workers tend to have shorter lives, a one-year increase in the retirement age represents a larger proportional cut in their total pension benefits paid during retirement than it does for higher-income people. OECD (2017[1]) shows that this effect is likely to be quantitatively small.

However, linking the retirement age to life expectancy is a policy that mainly aims at responding to overall longevity gains. Broadly shared longevity gains with unchanged retirement ages is progressive based on the same argument: they tend to benefit those with shorter expected lives relatively more. In that sense, increasing the retirement age to accompany well-shared life-expectancy gains goes towards restoring neutrality (OECD, 2017[1]).

One important question for the relevance of linking the retirement age to life expectancy relates therefore to how socio-economic differences in life expectancy evolve. If gains in life expectancy are not evenly distributed and favour higher-income groups, further exacerbating inequality in life expectancy, a higher retirement age would raise equity concerns. There is conflicting evidence about trends in life-expectancy inequality. In some countries, however, such as Denmark and the United States, it has risen. In any case, whether one focuses on the static or the dynamic side, first-best health policies should tackle inequality in life expectancy.

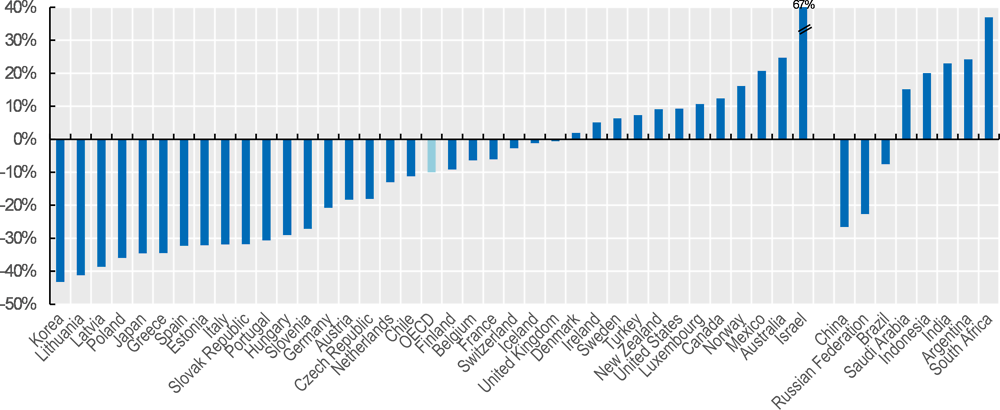

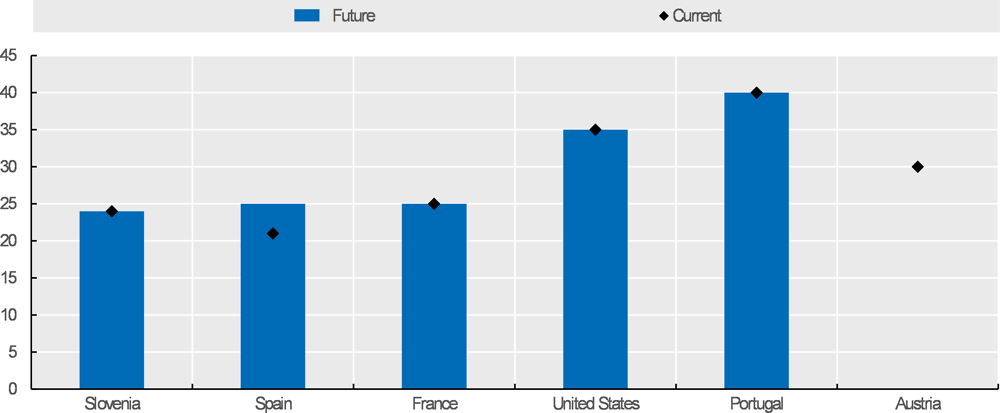

Changes in pension replacement rates

Pension reforms over the past decades have led to about a small one percentage-point decline for the OECD on average in pension replacement rates between individuals born in 1940 and those retiring about today (1956 birth cohort), but to significant changes in a few countries (OECD, 2019[7]). According to current legislation, larger changes will affect those born in 1996 - which enter the labour market about today. Replacement rates will be lower for full-career workers born in 1996 relative to those born in 1940 in about 60% of OECD countries, but higher in about 30%; they will be stable in the remaining 10%. The OECD average is expected to fall by 5.8 percentage points (i.e. by slightly more than 10%) for the cohort born in 1996 compared to the cohort born in 1940 (Figure 1.17).

There are large drops in replacement rates of more than 30 percentage points in countries that started from a relatively high levels for the 1940 cohort, such as Mexico, Poland and Sweden. While the old DB scheme in Mexico pays high pensions, ensuring almost a full replacement of past earnings for those born before 1977 with a full career, the current DC scheme would yield low replacement rates given low contribution rates.

The introduction of NDC schemes in Sweden and Poland has substantially lowered replacement rates for cohorts of retirees affected by the reform while it has had a much smaller impact in Norway (6 p.p.). In Latvia, the impact of the new NDC pensions was large as well, but the 1940 cohort was already affected. As NDC schemes are by design supposed to ensure actuarial fairness, the fall in replacement rates mostly reflects the extent of the financial unsustainability of the pre-reform systems. In Italy, the other OECD country having introduced an NDC pension system, a fall in the replacement rate at the normal retirement age is only avoided by the sharp increase in the retirement age due to the link to life expectancy.

On top of the countries listed above, the baseline replacement rate will fall by more than 15 p.p. in Chile, Greece, Spain and Switzerland. Chile replaced its complex public DB scheme by a privately managed fully funded DC scheme based on low contribution rates while issuing recognition bonds to account for accrued entitlements in the DB scheme. Greece lowered the accrual rates in the DB system and changed the indexation of basic pensions from wage growth to price inflation. In 2013, Spain introduced a sustainability factor that would automatically reduce pensions with increasing longevity.25 In Switzerland, basic pension components and pensionable earnings thresholds are indexed to the average of wage growth and price inflation, thereby falling relative to wages over time. Moreover, in occupational pensions increasing longevity combined with the low interest rate environment led to a reduction in the legal minimum rates of return, which are now binding.

Replacement rates have increased by more than 15 percentage points for countries with a relatively low replacement rates for the 1940 cohort. In particular, Estonia, Israel and Korea have expanded their pension system. Israel and Estonia introduced mandatory funded DC schemes in the 2000s while Korea introduced a mandatory public DB scheme in 1988.

Absolute changes in replacement rates between the 1940 and 1996 cohorts are lower than 5 p.p. in 13 OECD countries. This is because pension reforms have been more limited in these countries or, like in the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Latvia, Portugal or the United States, because the increase in retirement ages have at least partly offset the impact of reforms affecting generations born after 1940. Actually, in Denmark, Italy and Turkey the comparatively small changes in the replacement rate go along with large increases in the normal retirement age, implying that younger generations can expect similar benefit levels as older generations in percent of last wages, only if they work longer and retire at a much later age.

References

[2] Blanchard, O. (2019), Public debt and low interest rates, American Economic Association, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.109.4.1197.

[9] Boulhol, H. (2019), “Objectives and challenges in the implementation of a universal pension system in France”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1553, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5a476f15-en.

[12] Boulhol, H. and M. Lüske (2019), “What’s new in the debate about pay-as-you-go vs funded pensions?”, in Nazaré, D. and N. Cunha Rodrigues (eds.), The Future of Pension Plans in the EU Internal Market: Coping with Trade-Offs Between Social Rights and Capital Markets, SPRINGER, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29497-7.

[6] European Commission (2018), The 2018 Pension Adequacy Report, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

[5] Lis, M. and B. Bonthuis (2019), “Drivers of the Gender Gap in Pensions: Evidence from EU-SILC and the OECD Pension Model”, SOCIAL PROTECTION & JOBS DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES, No. 1917, The World Bank, Washington, http://www.worldbank.org (accessed on 26 May 2019).

[11] Natali, D. (2018), “Recasting Pensions in Europe: Policy Challenges and Political Strategies to Pass Reforms”, Swiss Political Science Review, Vol. 24/1, pp. 53-59, https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12297.