1. Tax revenue trends 1965-2020

Revenue Statistics 2021 presents detailed internationally comparable data on tax revenues of OECD countries for all levels of government. The latest edition provides final data on tax revenues in 1965-2019. In addition, provisional estimates of tax revenues in 2020 are included for almost all OECD countries.1

In Revenue Statistics 2021, taxes are defined as compulsory, unrequited payments to the general government or to a supranational authority. Taxes are unrequited in the sense that benefits provided by government are not normally in proportion to their payments.

In the OECD classification, taxes are classified by the base of the tax:

Compulsory social security contributions paid to general government, which are treated as taxes (heading 2000)

Much greater detail on the tax concept, the classification of taxes and the accrual basis of reporting is set out in the OECD Interpretative Guide at Annex A of Revenue Statistics 2021.

All of the averages presented in this summary are unweighted.

Tax ratios for 2020 (provisional data)

New OECD data in the annual Revenue Statistics 2021 publication show that on average, tax revenues as a percentage of GDP (i.e. the tax-to-GDP ratio) were 33.5% in 2020, an increase of 0.1 percentage points (p.p.) of GDP relative to 2019. The small increase in the OECD average tax-to-GDP ratio in 2020 occurred against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to widespread falls in both nominal tax revenues and in nominal GDP; the reason for the increase is that in most countries, GDP fell by more than nominal tax revenues. Chapter 2 of this publication provides more information on the changes in tax revenues for each country, including for different types of taxes. The tax-to-GDP ratio increased in 20 of the countries for which 2020 data are available and decreased in 16; on average, the decreases and increases were of a similar magnitude (0.7 p.p.).

Country tax-to-GDP ratios in 2020 varied considerably (Table 1.1), both across countries and since 2019. Key observations include:

Denmark had the highest tax-to-GDP ratio in 2020 (46.5%), and with the exceptions of 2017 and 2018, in which France was higher, has had the highest tax-to-GDP ratio of OECD countries since 2002. France had the second-highest tax-to-GDP ratio in 2020 (45.4%). Mexico had the lowest tax-to-GDP ratio (17.9%).

Of the 36 countries for which data for 2020 are available, the ratio of tax revenues to GDP compared to 2019 rose in 20 and fell in 16.

Between 2019 and 2020, the largest tax ratio increase was in Spain, at 1.9 percentage points of GDP. This was largely due to an increase in revenues from social security contributions as a share of GDP (1.5 percentage points), following a smaller fall in SSC revenues than in GDP (see chapter 2 for more information). The second largest increase was in Mexico (1.6 p.p.), with increases in all major tax types both in nominal terms and as a share of GDP. Iceland was the only other country with an increase of over 1 p.p. (Figure 1.2).

The largest fall in the tax-to-GDP ratio between 2019 and 2020 was in Ireland, at 1.7 p.p.. The decrease in Ireland was in large part due to a fall in VAT revenues following the temporary reduction in VAT rates in 2020 and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in decreasing economic activity. Smaller falls in personal income taxes, social security contributions, property taxes and excises also contributed.

Decreases of over one percentage points were also seen in Chile (1.6 p.p.) and Norway (1.3 p.p.). In Norway, the fall was due to a sharp decrease in corporate income tax revenues (3.5 p.p.), due to temporary changes in the Petroleum Tax Act to help oil and gas companies execute planned investments as well as the opportunity to offset losses in 2020 against taxed surpluses from the previous two years. This fall was offset by increases in all other major tax types.

Over the last decade, the OECD average tax-to-GDP ratio was higher in 2020 than in 2010, when it was 31.6% of GDP on average. Across countries, the tax-to-GDP ratio was higher in 2020 than in 2010 in 30 countries. The largest increase was seen in the Slovak Republic (6.7 percentage points) and in Greece (6.5 p.p.); increases of over 5 percentage points were also seen in Korea, Spain, Japan (2019 data) and Mexico. Decreases since 2010 were seen in the remaining eight countries. The largest fall has been in Ireland, from 27.7% in 2010 to 20.2% of GDP in 2020, largely due to the exceptional increase in GDP in 2015, although the tax-to-GDP ratio has continued a slower decline since 2015. The next largest decrease was seen in Norway (3.2 percentage points), largely due to falling corporate income tax revenues (Figure 1.2).

Changes in the tax-to-GDP ratio are driven by the relative changes in nominal tax revenues and in nominal GDP. From one year to the next, if tax revenues rise more than GDP (or fall less than GDP) the tax-to-GDP ratio will increase. Conversely, if tax revenues rise less than GDP, or fall further, the tax-to-GDP ratio will go down. Therefore, the tax-to-GDP ratio does not necessarily mean that the amount of tax revenues have increased in nominal, or even real, terms.

In 2020, 20 OECD countries experienced an increase in their tax-to-GDP ratio relative to 2019. However, this was due to an increase in nominal tax revenues in only six of these countries. In the remaining 14 countries where tax-to-GDP ratios increased in 2020, both tax revenues and GDP fell (with GDP falling further). Of the 16 OECD countries that experienced a decline in their tax-to-GDP ratio in 2020, only Denmark had higher levels of tax revenues in nominal terms than the preceding year and this increase was slightly less than the increase in nominal GDP. Eleven of these countries saw declines in both nominal tax revenues and in nominal GDP, with tax revenues decreasing further; and the remaining four countries (Ireland, Chile, Hungary and Luxembourg) saw decreases in nominal tax revenues compared to increases in nominal GDP. (Figure 1.3). In Figure 1.3, changes between 2018 and 2019 are shown for Australia and Japan, where the tax-to-GDP ratio is not available in 2020. In both countries, nominal tax revenues decreased while GDP increased, leading to falls in the tax-to-GDP ratio.

The tax-to-GDP ratios shown in Revenue Statistics 2021 express aggregate tax revenues as a percentage of GDP. The value of this ratio depends on its denominator (GDP) as well as its numerator (tax revenue), and that the denominator – GDP – is subject to historical revision.

The numerator (tax revenue)

For the numerator, the OECD Secretariat uses revenue figures that are submitted annually by correspondents from national Ministries of Finance, Tax Administrations or National Statistics Offices. Although provisional figures for most countries become available with a lag of about six months, finalised data become available with a lag of around one and a half years. Final revenue data for 2019 were received during the period May-August 2021.

In thirty-five OECD countries the reporting year coincides with the calendar year. Three countries — Australia, Japan and New Zealand — have different reporting years. Reporting year 2018 includes Q2/2018–Q1/2019 (Japan) and Q3/2018–Q2/2019 (Australia, New Zealand) respectively (Q = quarter).

The denominator (GDP)

For the denominator, the GDP figures used for Revenue Statistics 2021 are the most recently available in September 2021. By that time, the 2019 and 2020 GDP figures were available for all OECD countries.

Using these GDP figures ensures a maximum of consistency and international comparability for the reported tax-to-GDP ratios.

The GDP figures are based on the OECD Annual National Accounts (ANA – SNA) for the thirty-four OECD countries where the reporting year is the actual calendar year.

Where the reporting year differs from the calendar year, the annual GDP estimates are obtained by aggregating quarterly GDP estimates provided by the OECD Statistics Directorate for those quarters corresponding to each country’s fiscal (tax) year.

The average shown in this publication is an unweighted average for all countries in which data is available. The 2020 provisional average calculated by applying the unweighted average percentage change for 2020 in the 36 countries providing data for that year to the overall average tax to GDP ratio in 2019. The historical series for the OECD average shown in this publication is lower than that shown in previous editions due to the inclusion of Costa Rica in the OECD average for the first time in this edition, after Costa Rica became an OECD member in May 2021.

Tax-to-GDP ratios for 2019 (final data)

The latest year for which tax-to-GDP ratios are based on final revenue data and available for all OECD countries is 2019 (Figure 1.4). These data show that tax ratios vary considerably across countries:

In 2019, Denmark had the highest tax-to-GDP ratio (46.6%), followed by France (44.9%). Five other countries also had tax-to-GDP ratios above 40% (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Italy and Sweden).

Mexico had the lowest ratio at 16.3% followed by Colombia (19.7%), Chile (20.9%), Ireland (21.9%), Turkey (23.1%), Costa Rica (23.6%) and the United States (25.0%). No other countries had a tax-to-GDP ratio of less than 25% in 2019 and three other countries had ratios below 30% (Australia, Korea and Switzerland).

The tax-to-GDP ratio in the OECD area as a whole (un-weighted average) was 33.4% in 2019. In 2018, it was 33.5%.

Relative to 2018, overall tax ratios rose in 18 OECD member countries and fell in 20.

The largest increases in the tax-to-GDP ratio was in Denmark (2.4 p.p.). There were no other increases over one p.p..

The largest reductions were in Iceland (1.6 p.p.) and Belgium (1.2 p.p.).

Between 2018 and 2019, the fall in the average tax-to-GDP ratio were driven by decreases in revenues from corporate income taxes and excise taxes (0.1 p.p. each), offset by an increase in personal income tax revenues (0.1 p.p.).

Tax ratio changes between 1965 and 2019

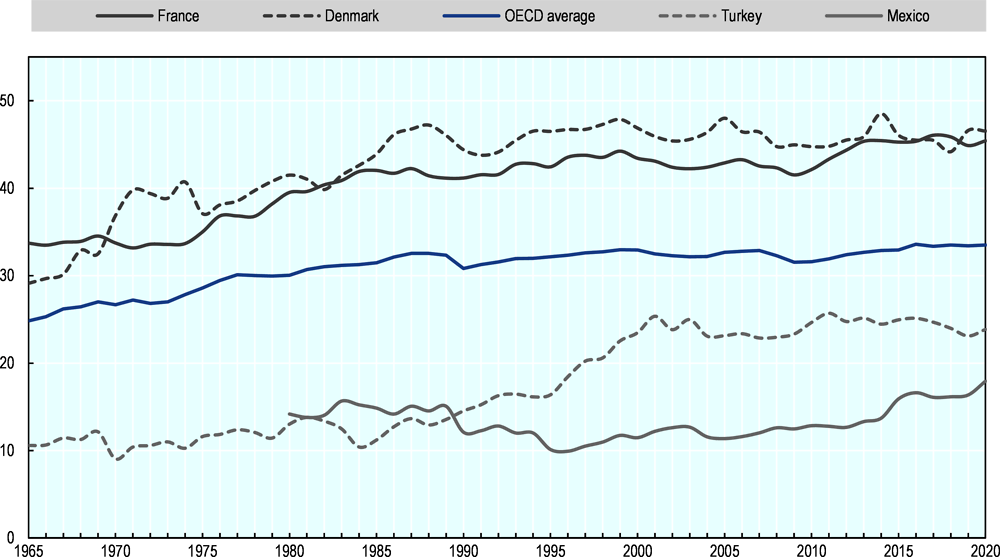

Between 1965 and 2019, the average tax-to-GDP ratio in the OECD area increased from 24.8% to 33.4% (an increase of 8.6 percentage points, with the difference due to rounding) (Figure 1.1).

Before the first oil shock (1973 to 1974), strong, almost uninterrupted income growth enabled tax levels to rise in all OECD countries. In part, tax levels rose automatically through the effect of fiscal drag on personal income tax schedules. From 1975 to 1985, the tax burden in the OECD area increased by 2.9 percentage points. After the mid-1970s, the combination of slower real income growth and higher levels of unemployment apparently limited the revenue raising capacity of governments. But during and after the deep recession following the second oil shock (1980), countries in Europe saw tax levels rise further, to finance higher spending on social security and rein in budget deficits.

After the mid-1980s, most OECD countries substantially reduced the statutory rates of their personal and corporate income tax, but the negative revenue impact of widespread tax reforms was often offset by reducing or abolishing tax reliefs. By 1999, the average OECD tax-to-GDP ratio had risen to 33.0%, the highest recorded level at that time. It fell back slightly between 2001 and 2004, but then rose again between 2005 and 2007 before falling back following the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009. Taking these changes together the average tax level in the OECD area increased by 1.3 percentage points between 1995 and 2019 (Figure 1.1).

The OECD average conceals the great variety in national tax-to-GDP ratios. In 1965, tax-to-GDP ratios in OECD countries ranged from 10.6% in Turkey to 33.7% in France. By 2019 the corresponding range was from 16.3% in Mexico to 46.6% in Denmark. The trend towards higher tax levels over this period reflects the need to finance a significant increase of public sector outlays in almost all OECD countries.

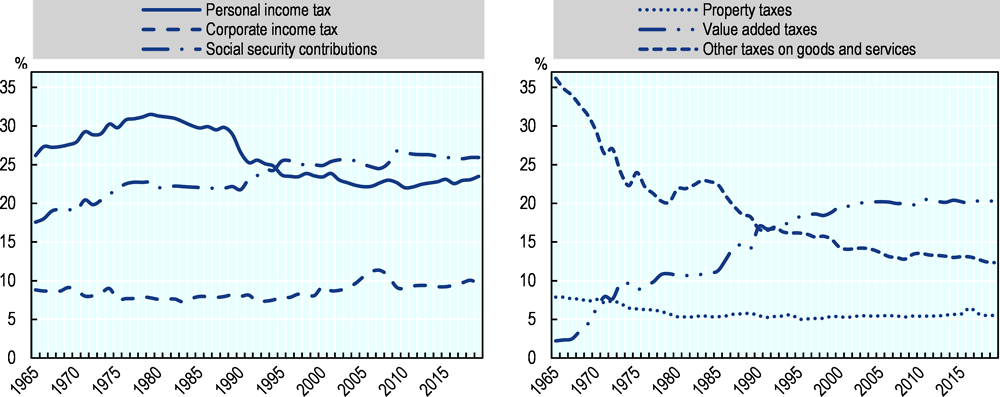

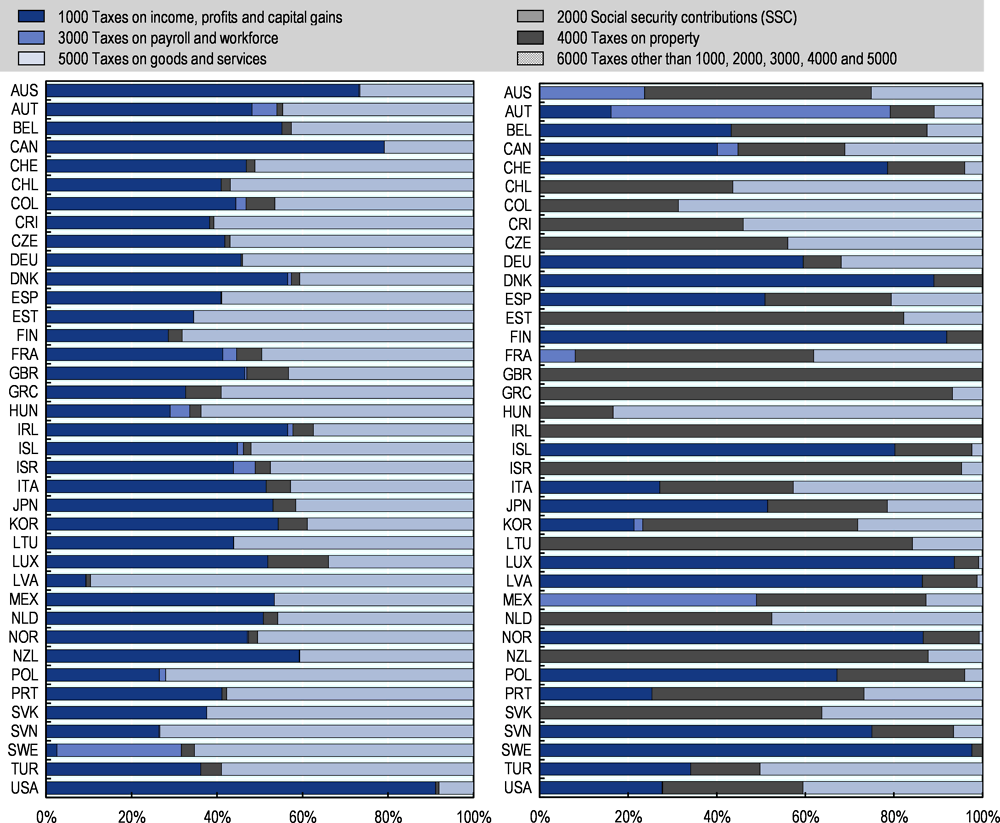

Tax structures are measured by the share of major taxes in total tax revenue. In 2019, the tax structures of OECD countries varied. Seventeen countries raised the largest part of their revenues from income taxes (both corporate and personal), ten countries raised the largest part of their revenues from SSCs, and 11 countries raised the largest part of their revenues from consumption taxes (including VAT). Taxes on property and payroll taxes played a smaller role in the revenue systems of OECD countries in 2019, both on average and within most countries (Figure 1.5).

While on average tax levels have generally been rising, the tax structure or tax ‘mix’ has been remarkably stable over time. Nevertheless, several trends have emerged up to 2019 – the latest year for which data is available for all 38 OECD countries. These trends are discussed further below.

Taxes on income and profits

On average, in 2019, OECD countries collected 33.1% of their tax revenues through taxes on income and profits (personal and corporate income taxes taken together). Taxes on personal and corporate incomes remain the most important source of revenues used to finance public spending in 17 OECD countries, and in ten of them – Australia, Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland and the United States – the share of income taxes in the tax mix in 2019 exceeded 40%.

Within taxes on income and profits, the share of PIT and CIT varies:

Revenues from personal income taxes are 23.5% of total taxes on average in 2019 compared with around 30% in the 1980s. About two percentage points of this reduction can be attributed to the impact on the average of a number of relatively new entrants to the OECD from Eastern Europe and Latin America for which tax revenue data is only available from the 1990s onwards. These countries tend to have relatively low personal income tax revenues and high revenues from social security contributions or corporate income taxes, but this impact is observed in the post 1990 data only.

The variation in the share of the personal income tax between countries is considerable. In 2019, it ranged from a low of 6.8% in Colombia to 42.0% in Australia and the United States, and 52.1% in Denmark (Figure 1.5).

Corporate income tax revenues represented between 7% and 9% of total tax revenues, on average, throughout the period 1965 to 2003. They then increased to a high of 11.3% in 2007, before dropping to 9.0% in 2010, directly after the financial crisis. They remained at between 9.0% and 10.0% of total revenues until 2018, and dropped back to 9.6% of revenues in 2020.

The share of the corporate income tax in total tax revenues varied considerably across countries from less than 5% (France, Hungary, Italy and Latvia) to over 20% in Mexico (20.1%), Chile (23.4%) and Colombia (24.0%) in 2019. Apart from the spread in statutory rates of the corporate income tax, these differences are at least partly explained by institutional and country specific factors, for example:

the breadth of the corporate income tax base, for example some narrowing may occur as a consequence of generous depreciation schemes and of tax incentives,

the degree of cyclicality of the corporate tax system, for which one of the important elements are loss offset provisions,

the extent of reliance upon tax revenues from the exploitation of oil and/or mineral deposits, and

other instruments to postpone the taxation of earned profits.

Social security contributions

Social security contributions as a share of total tax revenues on average across the OECD accounted for 25.9% in 2019. They were highest in the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic (44.2% and 43.4%, respectively). In contrast, Australia and New Zealand do not levy social security contributions.

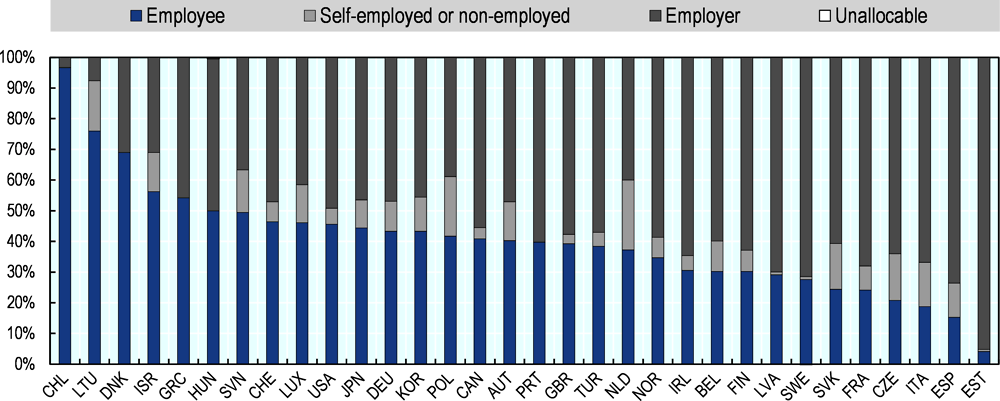

There is also wide variation across OECD countries in the relative proportions of social security contributions paid by employees and employers (Figure 1.7):

Nine countries (Chile, Denmark, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, and Slovenia) raise more revenues from employee SSCs, whereas the remainder raise more from employer SSCs.

The highest share of employee SSC revenues are found in Lithuania, at 24.2% of total revenues. Germany, Greece, Hungary, Japan, Poland and Slovenia also have employee SSC revenues of over 15% of total tax revenues. Denmark had the lowest share, at 0.1% of total revenues. Apart from Denmark, only Estonia had revenues from employee SSCs of less than 5% of total revenues.

The highest share of employer social security contribution revenues are found in Estonia, at 33.3% of total revenues. The Czech Republic (28.3%), the Slovak Republic (26.3%) and Spain (26.0%) also had employer SSC revenues of over 25% of total tax revenues. Denmark and Chile had the lowest shares, at 0.03% and 0.2% of total revenues respectively.

The highest share of self-employed or non-employed social security contribution revenues are found in the Netherlands and Poland, at 7.8% and 7.3% of total revenues respectively.

Property taxes

Between 1965 and 2019, the share of taxes on property fell from 7.9% to 5.5% of total tax revenues on average across the OECD (Figure 1.6). Canada, Israel, Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States had property tax revenues that amounted to more than 10% of total tax revenues. By contrast, property taxes accounted for less than 1% of total revenues in Estonia and Lithuania.

Consumption taxes

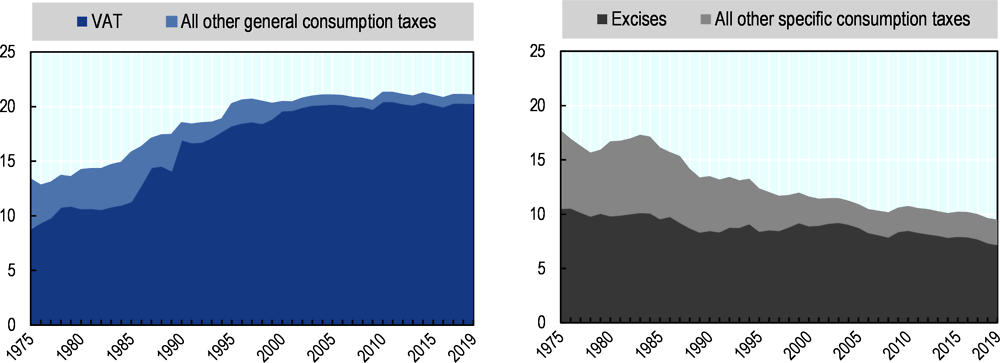

The share of taxes on consumption (general consumption taxes plus specific consumption taxes) fell from 38.4% to 32.6% between 1965 and 2019 (Figure 1.6).

During this period, the composition of taxes on goods and services has fundamentally changed. A fast-growing revenue source has been general consumption taxes, especially the value-added tax (VAT) which is imposed in thirty-seven of the thirty-eight OECD countries.3

General consumption taxes presently account for 21.0% of total tax revenue, compared with only 11.9% in the mid-1960s. In 2019, the vast majority of this was from VAT (20.3% of total tax revenues) (Figure 1.6)

The substantially increased importance of the value-added tax has served to counteract the diminishing share of specific consumption taxes, such as excises and custom duties.

Between 1975 and 2019 the share of specific taxes on consumption (mostly on tobacco, alcoholic drinks and fuels, as well as some environment-related taxes) have almost halved from 17.7% to 9.5% of total revenues. In 2019, excises were the largest single category of total revenues in this heading, accounting for 7.2% of total revenues (Figure 1.8).

Rates of taxes on imported goods were considerably reduced across all OECD countries, reflecting a global trend to remove trade barriers.

Nevertheless, countries such as Costa Rica, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia (between 11-15%) and Turkey (19.3%) still collect a relatively large proportion of their tax revenues through taxes on specific goods and services.

This section discusses the relative share of tax revenues attributed to the various sub-sectors of general government in 2019. The different sub-sectors are:

The guidelines for attributing these revenue shares to the different levels of government are based on the final version of the 2008 System of National Accounts. These guidelines are discussed in the special feature S.1 in the 2011 edition of OECD Revenue Statistics.

Revenues of sub-national governments in federal and unitary countries

Eight OECD countries have a federal structure. Among these countries, central governments received 53.0% of total revenues in 2019 on average. The second-highest share of revenues on average was received by social security funds, which are a sub-sector of general government, at 21.4% of total revenues, followed by 17.7% at the state level and 7.7% at the local level (Table 1.3). However, within countries there was considerable variation around these means:

In 2019, the share of central government receipts in the eight federal OECD countries varied from 29.3% in Germany to 80.8% in Australia.

In 2019, the share of the states varied from 2.0% in Austria, 4.1% in Mexico and 10.6% in Belgium to 39.5% in Canada. The share of local government varied from 1.7% in Mexico to 14.6% in the United States and 15.7% in Switzerland.

Between 1975 and 2019 the share of federal government revenues declined by over fourteen percentage points in Belgium and by between five and six percentage points in Canada and the United States.

The share of federal government revenues increased in Austria by around 13 percentage points. There was little change in Australia and Mexico.

Of the seven federal countries with social security funds, five increased the share of revenue between 1975 and 2019. The exceptions were Canada and Mexico, where the share slightly declined between 1975 (1980 for Mexico due to data availability) and 2019.

Colombia and Spain are classified as regional rather than unitary countries because of their highly decentralised political structure, and have very different compositions by level of government. In Colombia, the share of central government receipts was 73.0% in 2019, with regional governments receiving 5.0% of total revenues and local governments receiving 12.5%. In Spain, the share of central government receipts in 2019 was 40.2% compared with 15.4% for regional governments and 9.2% for local governments.

The remaining twenty-eight OECD countries have a unitary structure. In these countries, an average of 63.2% of revenues were derived at the central level, with 25.5% accounted for by social security funds. A further 10.9% were raised by local governments. Among unitary OECD countries:

The share of central government receipts in 2019 varied from 32.6% in France to 93.1% in New Zealand.

The local government share varied from 0.8% in Estonia to 35.5% in Sweden.

Between 1975 and 2019 there have been shifts to local government of 5 percentage points or more in six countries – France, Iceland, Italy, Korea, Portugal and Sweden. Shifts of 5 percentage points or more in the other direction occurred in three countries – Ireland, Norway and the United Kingdom.4

Between 1975 and 2019, there were increases in the share of social security funds of 7 or more percentage points in four countries – Finland, France, Japan and Korea and corresponding decreases in four other countries – Italy, Norway, Portugal and Sweden.

Composition of central and sub central revenues

Figure 1.9 shows the revenues from each major category of tax revenue for central and sub central governments. For federal and regional countries, the sub central level includes revenues received by both state and local governments. Figure 1.9 demonstrates that:

Central government revenues in almost all OECD countries are predominantly derived from income and goods and services taxes, with a negligible share from property taxes.

At the subnational level, revenue from property taxes provides a much larger share of revenues than at the central level, and accounts for over 90% of revenues in four countries (Israel, Ireland, Greece and the United Kingdom).

By contrast, the share of income taxes and goods and services taxes is lower at the sub-central level, the exceptions being Finland, Luxembourg and Sweden, where over 90% of sub-central revenues are derived from income taxes.

Revenues paid to a supranational authority

The twenty-two EU member states that are also members of the OECD collect taxes on behalf of the European Union (EU), as did the United Kingdom prior to 2020. These taxes primarily consist of customs duties and Single Resolution Fund contributions.5 Both taxes are collected on behalf of the EU by national tax administrations and are included in the total tax figures under headings 5123 and 5126 at the SUPRA level of government. In addition, they are shown as a memorandum item separately from the main figures since they represent a tax imposed by the EU and collected by national administrations.6

Table 1.5 shows the level of taxes collected on behalf of supranational governments in EU countries that are also OECD members, divided into those countries in the Euro area and other EU member countries.

In 2019, the combined total of payments collected for the EU was highest in Belgium and the Netherlands, at over 0.4% of GDP. Levels above 0.2% of GDP were also seen in Estonia, Greece, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Spain and Germany. All other EU countries that are also members of the OECD collected revenues on behalf of the EU equivalent to between 0.1 and 0.2% of GDP. In all countries except Finland, France and Luxembourg, customs duties were the majority source of these revenues.

There are two kinds of tax credits that apply to income taxes (both personal and corporate):

Non-payable or wastable tax credits are those that can only ever be used to reduce or eliminate a tax liability. They cannot be paid out to either taxpayers or non-tax payers as a benefit. They are, therefore, the same as a tax allowance or relief.

In contrast, payable or non-wastable tax credits can be partitioned into two parts. One part is used to reduce or eliminate a tax liability in the same way as a wastable tax credit. The other part can be paid directly to recipients as a benefit payment, when the benefit exceeds the tax liability.

The OECD methodology for classifying non-wastable tax credits is set out in paragraphs 25 and 26 of the Interpretative Guide. This states that only the part of a non-wastable tax credit that is used to reduce or eliminate a taxpayer’s tax liability should be subtracted in the reporting of tax revenues. This is referred to as the ‘tax expenditure component’ of the credit. In contrast, the part of the tax credit that exceeds the taxpayer’s tax liability and is paid to that taxpayer is treated as an expenditure item and not subtracted in the reporting of tax revenues. This part is referred to as the ‘transfer component’.

Table 1.6 provides information on the non-wastable tax credits in 2019 for those countries reporting them in the Revenue Statistics 2021 (though it may be that some countries with non-wastable tax credits do not appear in the table). It shows the amounts of the non-wastable tax credits and their two components together with the results of using the figures to calculate tax revenue values and the associated tax-to-GDP ratios. Table 1.6 also shows two alternative treatments:

The ‘net basis’ which treats non-wastable tax credits entirely as tax provisions, so that the full value of the tax credit reduces reported tax revenues, as shown in columns 4 and 7.

The ‘gross basis’ is the exact opposite, treating non-wastable tax credits entirely as expenditure provisions, with neither the transfer component nor the tax expenditure component being deducted from tax revenue, as shown in columns 6 and 9. This is the approach followed by the GFSM and the SNA.

Table 1.6 shows that, with some exceptions, the choice of method for reporting non-wastable tax credits has only a small impact on the ratio of total tax revenue to GDP. For the countries with available data, the differences between the ratios on a net basis and on a gross basis are one percentage point or more in only France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States, and between half a percentage point and one percentage point in Australia, Canada, Czech Republic, Italy, New Zealand.

A memorandum item7 in Revenue Statistics 2021 describes the financing of social security-type benefits in OECD countries. Unlike social assistance benefits, which are funded from general government revenues, social security-type benefits are funded via contributions to social security or to private insurance schemes, or by other earmarked sources of funding. These sources of financing include:

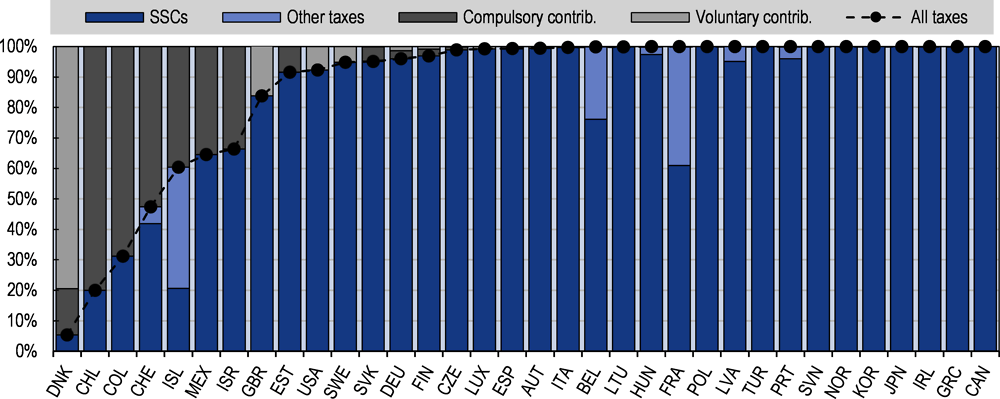

Figure 1.10 shows the relative contribution of each of these sources to financing for social security-type benefits in OECD countries, based on data provided by countries for inclusion in the memorandum item in Revenue Statistics 2021.

Taxes represent the largest source of earmarked financing for social security-type benefits, predominantly via social security contributions. Together, SSCs and other earmarked taxes account for over 90% of the financing of social security-type benefits in 26 OECD countries and 100% in 11 countries. In the remaining nine OECD countries that provide this data, compulsory contributions to the private sector play a larger role, at 80.0% in Chile, 68.8% in Colombia and 52.6% in Switzerland, with smaller shares in Iceland, Mexico and Israel. Few countries received significant shares of voluntary contributions: only in the United Kingdom and Denmark do these exceed 10% of financing.

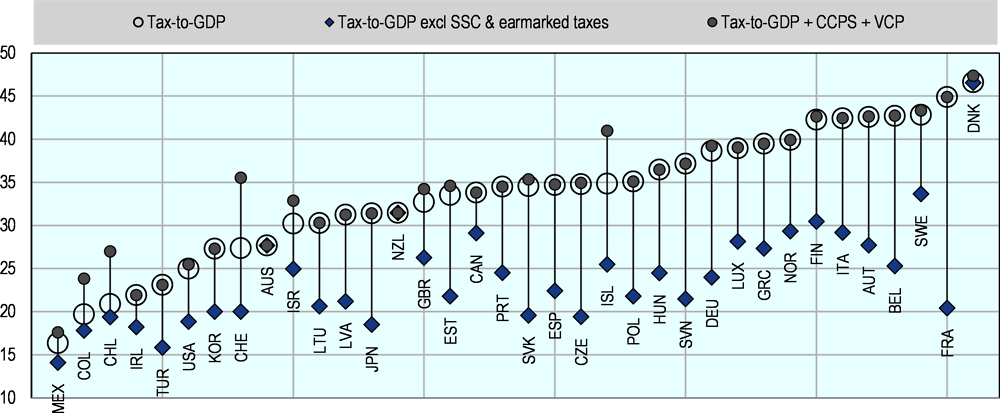

Figure 1.11 shows tax-to-GDP ratios (as in Table 1.1 and Figure 1.4) both exclusive of earmarked funding for social security-type benefits (i.e. tax-to-GDP ratios less SSCs and other earmarked taxes) and inclusive of all non-tax earmarked financing for social security-type benefits (i.e. tax-to-GDP ratios - including SSCs and other earmarked taxes - plus compulsory contributions to the private sector and voluntary contributions to government).

Countries with the largest share of social security-type schemes financed by non-tax earmarked contributions are Switzerland (8.2% of GDP), Chile and Iceland (6.1% in both cases), which materially affects their rankings:

Switzerland has a relatively low tax-to-GDP ratio among OECD countries, at 27.4%, but its combined ratio is above halfway in the OECD distribution;

Iceland has a tax-to-GDP ratio of 34.8%, in the top-third of OECD countries, and a combined ratio of 41.0%, which is the eighth-highest in the OECD.

Chile has the third-lowest tax-to-GDP ratio and the sixth-lowest combined ratio.

Excluding earmarked financing for social security benefits from the tax-to-GDP ratio does not affect Australia, Denmark and New Zealand, where benefits are funded out of general taxation. Figure 1.11 highlights that the largest share of earmarked funding for social security-type benefits is seen in France, at 24.5% of GDP, as indicated by the difference between the highest and lowest points on the figure. Belgium, Iceland, the Slovak Republic and Switzerland have the next highest shares, at between 15% and 18% of GDP.

Notes

← 1. Provisional 2020 figures are not available for Australia and provisional figures on social security contributions in Japan are also not available as at the time Revenue Statistics 2021 was published.

← 2. In 2016, Iceland received revenues from one-off stability contributions from entities that previously operated as commercial or savings banks and were concluding operations. The revenue from these contributions led to unusually high tax revenues for a single year and consequently, Iceland’s tax-to-GDP ratio rose from 35.1% in 2015 to 50.3% in 2016, before dropping to 37.1% in 2017. This led to an artificial high in the OECD average tax-to-GDP ratio in 2016 of 33.6%. Without these one-off revenues in Iceland, the OECD average tax-to-GDP ratio would have been 33.2%, an increase of 0.3 p.p. relative to 2015.

← 3. The terms “value added tax” and “VAT” are used to refer to any national tax that embodies the basic features of a value added tax by whatever name or acronym it is known e.g. “Goods and Services Tax” (“GST”).

← 4. For 1975, please see Table 1.4 of Revenue Statistics 2021.

← 5. The Single Resolution Fund (SRF) has been in place since 2015 and countries in the Eurozone are required to make SRF contributions under the Single Resolution Mechanism (Regulation (EU) No 806/2014). Contributions are paid on an ex-ante basis and contributions are transferred from the national authorities to the SRF. So far, contributions have been collected for the years 2015 to 2020.

← 6. In addition, EU civil servants pay income taxes and social security contributions directly to the EU. These revenues are not included in the data or total tax revenues in this publication as they are not paid to or collected by a national government. However, for two of the countries with the highest number of EU civil servants (Belgium and Italy), a memorandum account at the end of the respective country table in Chapter 5 provides information on the scale of these payments.

← 7. The financing of social security-type benefits is shown in Table 4.77 on a comparable basis (percentage of GDP) and in Table 5.39 on a national currency basis.