copy the linklink copied!2. National approaches to increased coherence in climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction

This chapter examines national approaches to policy development and implementation on climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction, and the potential for introducing greater coherence across the two policy areas. The chapter is structured around five potential entry points through which coherence between the two policy processes can be strengthened: i) policy and governance, ii) data and information, iii) implementation, iv) financing, and v) monitoring, evaluation and learning. Informed by the country experiences of Ghana, Peru and the Philippines, the chapter identifies good practices and lessons learned for coherence at different levels of government, across sectors and stakeholder groups. This contributes to the identification of ways through which governments can put in place enabling conditions that facilitate greater coherence between the two policy areas. The potential role of development co-operation in supporting these efforts is also highlighted.

copy the linklink copied!Aligning governance for CCA and DRR

With the adoption of both the Paris Agreement on climate change and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction in 2015, governments have been equipped with a political mandate for a more coherent approach to climate change adaptation (CCA) and disaster risk reduction (DRR). Both frameworks share the objective of increased resilience to climate-related risks. For CCA, the emphasis is on enhancing the capacity to respond to future climate change and disaster risks as well as to slow onset changes. In the context of DRR, the focus has shifted over the years from primarily being on emergency response towards a more comprehensive approach, encompassing disaster prevention, preparedness, response and recovery. This paradigm shift was initiated with the adoption of the Hyogo Framework of Action on Disaster Risk Reduction in 2005, followed by the Sendai Framework in 2015 when resilience to disaster risk was elevated as a priority, complementing the focus on reducing disaster risks (UNDRR, 2005[1]), (UNDRR, 2015[2]).

The extent to which countries are taking a coherent approach to CCA and DRR – or whether it is even a priority – depends on the political, socio-economic and environmental context and circumstances. At the same time, the priority given to enhancing the level of coherence between the two policy processes may be determined by the nature of the climate and disaster risks in a given country, and by the political priority given to each. Countries, such as the Philippines and Peru that are significantly exposed to natural hazards, have a long history in managing and responding to extreme events, with the institutional frameworks for DRR better developed and established than for CCA. The processes in place and the systematic approach to DRR offers lessons and entry points for a complementary focus on CCA. In other countries such as Ghana where the focus to a larger extent has been on CCA, but where a complementary focus on DRR may be valuable given the nature of emerging hazards, DRR can leverage systems and resources available more recently for CCA. To align policy processes in support of CCA and DRR towards joint objectives, an overview of existing institutional arrangements is needed. To increase co-ordination towards coherence also requires additional resources and capacities and must take different levels of development into account. This requires political support and strong leadership by a recognised co-ordination entity. In some cases, technical assistance by development co-operation can provide valuable support to partner countries to put in place the right co-ordination mechanisms.

In many developing countries, a central government entity oversees the formulation and enforcement of national development strategies. With increasing recognition of the potential impact of climate risks on development objectives, central co-ordination entities are increasingly mainstreaming CCA and DRR objectives into national planning processes. In Ghana, for example, the National Development Planning Commission plays a central co-ordinating role in the formulation of the country’s long-term development strategy. The Commission also provides local authorities with guidance and technical support to ensure that local development plans are aligned with national priorities. With Ghana’s adoption of the Paris Agreement, this includes guidance on the integration of the objectives of Ghana’s Nationally Determined Contribution into sectoral and local development plans by sub-national assemblies (Ghana, 2017[3]). While this, for the time being, does not include a complementary focus on DRR or coherence between the two, the current approach could facilitate this, in case it will be considered a national priority. Similarly, the Philippines’ national planning agency has been responsible for integrating DRR and CCA in the various sectoral policies and strategies in its development plan. The current Philippine medium term plan identifies ensuring safety and increasing resilience as one of the bedrock strategies for attaining inclusive growth.

A commonality of both CCA and DRR is the need for measures to be mainstreamed across sectors, including, but not limited to water, urban planning, transport, energy, infrastructure, health, and agriculture. As different stakeholders tend to use diverse terminologies for terms such as risk, impacts, vulnerability and resilience (Leitner et al., 2018[4]), strong leadership and high-level co-ordination play an important role in reaching a common understanding of what coherence in CCA and DRR means in a given country context. In Peru, this responsibility is assigned to the Presidency of the Council of Minister, and in the Philippines to the Climate Change Adaptation, Mitigation and Disaster Risk Reduction Cabinet Cluster. For coherence in policy processes to translate into coherence in implementation, key ministries such as the Ministry of Finance must also be engaged from the outset to ensure that the allocation of roles and responsibilities is matched with commensurate allocation of resources.

Institutionally, different models exist. For CCA, co-ordination usually falls under a lead ministry or agency: The Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation in Ghana, the Ministry of the Environment in Peru, and the Climate Change Commission in the Philippines. Those institutions, however, have limited capacity to encourage other line ministries or agencies to prioritise adaptation measures and ensure mainstreaming. Having said that, the same institutions oversee in some countries the NAP processes that have proven very effective in bringing a diverse set of actors to the table, and in providing a platform for dialogue, collaboration and information exchange.

For DRR, several agencies usually cover different phases of the risk management cycle, notably the prevention and the response phases, which can at times lead to institutional competition for resources. Nevertheless, all three case study countries have their central co-ordination bodies for DRR, namely the National Disaster Management Organisation in Ghana, the Presidency of the Council of Minister in Peru, and the National Disaster Risk Reduction Management Council in the Philippines.

Local governments are responsible for the bulk of CCA and DRR policy implementation, highlighting the importance of strong vertical co-ordination across levels of governments, and clear allocation of roles and responsibilities. However, DRR and CCA implementation at the local level often remains fairly disconnected from national policies. For example, in the Philippines, out of 1634 Cities and municipalities, 748 or less than 50% of local government units had integrated CCA and DRR in the Comprehensive Land Use Plan in 2018 (GOV.PH, 2017[5]). National laws mandate the formulation of Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Plans as well as National Climate Change Action Plans, however, compliance rates are still wanting.

While national guidelines on how to integrate DRR and CCA in local development plans are often in place, capacity constraints, lack of awareness, human and financial resources, knowledge and know-how, as well as high turn-over limit the ability of local governments to mainstream DRR and CCA in a coherent manner. Instead, DRR often remains response-oriented through local civil protection offices, whereas the responsibility for mainstreaming CCA often lies with local environment protection offices, which have limited implementation capacities. Empowering local initiatives through incentive mechanisms, capacity-building, knowledge-sharing and regular monitoring are ways national governments can foster coherence between CCA and DRR at the local level (see two examples in Box 2.1).

The Philippines and Ghana both provide examples of practices that foster coherence in CCA and DRR at the local level, which have the potential to be applicable elsewhere:

-

The Philippines demonstrates the efficiency of sharing human resources across DRR and CCA. Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Councils (LDRRMC) are tasked with preparedness activities, such as information dissemination and raising public awareness at the local level by, for example, displaying hazard maps in community spaces and disseminating printed information materials. Where robust LDRRMCs are in place, they can also act as a focal point for mainstreaming climate considerations into DRR plans. Stakeholders interviewed for this study noted that LDRRMCs often act as climate change champions, for example, by communicating sea-level rise risk maps at the community-level.

-

Together with other agencies, Ghana’s National Development Planning Commission has developed guidelines that provide a checklist to enable local assemblies to integrate Ghana’s NDC into their development plans. While there remains scope to better integrate DRR considerations, the checklist specifies that climate actions must be addressed in an integrated manner through the local assemblies’ policy planning and implementation. On adaptation, it identifies priority actions across six sectors with the overarching objective being to “increase climate resilience and decrease vulnerability for enhanced sustainable development” (Ghana, 2017[3]).

Beyond government, the engagement of the whole-of-society in CCA and DRR efforts often lacks appropriate governance arrangements. Adopting an inclusive approach to policy-making on both CCA and DRR is fundamental to address the needs of the most vulnerable populations, integrate local knowledge and solutions, and ultimately facilitate policy implementation. Dialoguemos in Peru, for example, is an initiative whereby the Ministry of the Environment holds large consultations with civil society for the development of its climate change adaptation policy. During the development of Peru’s Climate Change Law and the NDC that frames DRR as a cross-cutting issue for adaptation, 2 000 people from indigenous communities, academia, youth, private sector and other forms of civil society organisations participated in and contributed to Dialoguemos.

copy the linklink copied!Development of climate services in support of coherence in CCA and DRR

Coherence in CCA and DRR policy and practice relies on useful, relevant, credible and legitimate weather and climate data and information being accessible to policy makers as well as other state- and non-state actors (UNFCCC, 2017[6]) (Street, 2019[7]). Such information, also referred to as climate services, is defined as:

“[T]he transformation of climate-related data and other information into customised products such as projections, trends, economic analysis, advice on best practices, development and evaluation of solutions, and any other service in relation to climate that may be of use for the society at large.” (European Commission, 2015[8]).

There are important synergies between CCA and DRR to be explored through the development of climate services. In fact, the shift in focus of the Sendai Framework from managing disasters to managing risks provides a strong basis for coherence and mutual reinforcement between CCA and DRR. For example, a good understanding of the climate-related risks is essential when defining the priorities of a DRR policy at the national level and designing resilience measures at the local level. This must take into account the deep uncertainty of climate change projections (see Box 2.2 for examples) while at the same time recognising the broader drivers of risks, such as interactions between human and environmental systems, and social and cultural contexts (Ford et al., 2018[9]). This in turn can help increase the acceptability of CCA and DRR measures by local stakeholders.

1. Countries have made significant advances in strengthening climate services over the past decade with a move away from assessing hazards towards assessing risks. This involves collecting information on exposure and vulnerability – two key dimensions of risk. There are, nonetheless, a number of persistent challenges. First, accessing available information is often challenging or even not possible due to poor data quality (e.g. as a result of lacking or inadequate infrastructure for meteorological stations) and the format of the information (e.g. data being recorded on paper rather than electronically). In some cases, data is only available at a fee or not at all due to confidentiality constrains, further limiting use. Second, beyond hazard analysis, information on exposure and vulnerability to climate-related hazards is often more difficult to obtain, as this requires updated geospatial information on land use and social data and information, which tend to be spread across ministries and levels of government. Third, methodologies to develop risk assessments, when they exist, are often too complex for local users, who lack capacities to develop such analysis. As a result, efforts to strengthen the quality and availability of climate and weather-related data and information is progressing faster at the national than at the local level, despite the recognised need for good information at all levels.

To overcome these challenges, incentives must be in place to encourage owners of data to make it accessible, e.g., through financial compensation from the national budget rather than through user fees from different ministries and agencies. This must be matched by a good understanding of what information is needed and can credibly be provided, and to tailor that information to the respective user needs (Street, 2019[7]). Centralised platforms with access to data and information, including risk models, observation systems (meteorological offices) and academia can facilitate robust risk assessments tailored to user needs. The case study countries are starting to explore such an information sharing approach with the Climate Change Data Hub in Ghana, the Geospatial Information and Analysis System for Hazards and Risk Assessment in the Philippines and the Spatial Data Infrastructure in Peru.

Availability of climate services must be matched by capacity of stakeholders to use the services to conduct risk analysis. Many countries have separate risk assessment processes for CCA and DRR, and in some cases by individual ministries or sources of finance, which can be an inefficient use of the resources available. There remains scope to streamline relevant tools for climate and disaster risk assessments. In the Philippines the Department of the Interior and Local Government is working with the Global Initiative on Disaster Risk Management on harmonising risk-assessment approaches across different government bodies in an effort to overcome current practice where different ministries use different climate and disaster risk assessment (CDRA) tools for their respective planning processes (GIDRM, n.d.[10]). Finally, climate services are most effective when matched with tools that can translate climate information into a format that can guide decision-making processes, such as tools for costing adaptation options relative to estimated impacts avoided and for data visualisation, such as GIS-based tools (Palutikof et al, 2019[53])

In the face of deep uncertainties, assessing future climate risks to inform policy or financial decisions in a probabilistic manner will remain extremely challenging, despite enhanced availability and accessibility of climate services. Efforts should therefore be made to combine climate information with other ecological, economic and social factors that drive risks. Such an approach, also known as a storyline (or narrative) approach, uses descriptions of plausible future evolutions, characteristics, general logic and developments underlying a particular quantitative set of scenarios.

Storylines may be developed based on, for instance, particular types of (historical or plausible) events with high societal impacts, or particularly dangerous physical pathways of the climate system (e.g., tipping points). Such storylines can be used to help improve risk awareness, strengthen decision-making, explore the boundaries of plausibility of certain climate projections, provide a physical basis for partitioning uncertainty, and link physical climate information with human aspects of climate change.

To make the best use of information generated by climate change modelling and projections, climate information can also be complemented by community-based assessment of vulnerability and options of CCA and DRR measures. Multi-level stakeholder engagement from national governments to local communities can enhance complementarity between climate services and local knowledge and techniques, while also contributing to the development of local-level capacity in CCA and DRR.

Source: (CICERO, 2019[11]) (IPCC, 2018[12]) (Shepherd et al., 2018[13]) (Butler et al., 2015[14])

National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) are in many countries an important source of weather and climate data. Areas of responsibility include the design, operation and maintenance of national observation systems, data management including quality analysis and control, development and maintenance of data archives, and dissemination of climate products. NMHSs are well positioned to collaborate with academia, government departments, and other stakeholders, including the private sector and international and civil society organisations. Such partnerships can be crucial in enhancing data coverage and quality, and in facilitating the process of gathering and sharing data to make it accessible in a timely and cost efficient manner (WMO & GFCS, 2016[15]).

Across the three case study countries, the respective NMHSs – Philippines Atmospheric Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration, the Ghanaian Meteorological Service, and the National Institute for Hydrology and Meteorology in Peru – have all seen their capacities improve over the past decade. They have invested in monitoring networks, computing capacities for hydro-meteorological modelling and forecasting, as well as in the development of climate projections, in some cases, with the support of development co-operation. This enables them to produce relevant weather and climate information, from historic databases of hazard events, climate projections, or early warnings. On the hazard side, there are still opportunities to improve the coverage of hydro-meteorological monitoring networks and to further develop hazard modelling, to downscale climate models, and to increase the lead-time for early warnings.

copy the linklink copied!Implementing risk reduction measures for the climate-related risks of today and the future

Coherence in governance arrangements and information should translate into increased resilience on the ground through the implementation of risk reduction measures which take both CCA and DRR into account. Addressing existing and future exposures and vulnerabilities to floods, droughts, storms, forest fires, and other climate-related hazards through risk reduction measures requires a mix of structural and non-structural measures. The former includes protective infrastructure, and the latter measures, such as early-warning systems, the provision of risk information, land use and building codes or regulation to incorporate disaster risks and climate change into other investments. An integrated approach to CCA and DRR can help to avoid counterproductive investments, such as flood management measures that decrease exposure in the short term but may serve to increase development and associated future vulnerability (OECD, 2019[16]).

Prioritising for and designing structural measures should consider climate change projections, as these investments might otherwise not produce their foreseen benefits over their life cycle, resulting in increased costs. Examples include adjusting protection standards with a safety margin accounting for sea level rise or designing multi-purpose infrastructure (e.g. a dam for both floods, droughts and other uses). Across the three case studies, there is a recognition of the importance of mainstreaming climate risks into structural protection investments; however, this is not yet a consistent practice. In both the Philippines and Peru, guidelines are currently being developed on how to incorporate resilience considerations into general infrastructure investments.

In the context of the rapid urban development taking place in the Philippines, Peru, and Ghana, incorporating disaster risks and climate change into land-use decisions to avoid creating new risks should be a priority. To avoid or limit locking in future risks, public and private investments in urban development should factor in climate-related risks and the potential impacts of climate change under different scenarios. In Peru, while both CCA and DRR legal frameworks call for integration of climate resilience in municipal plans, there is still limited implementation of these provisions: with 70 of 18691 municipalities having indicated that they integrated DRR into their development plans in 2017 (CENEPRED, 2017[17]). Capacity gaps at the local level as well as an absence of enforcement mechanisms are cited as key barriers.

Healthy ecosystems play a key role in reducing risks and supporting adaptation over the long term. As the evidence base grows, nature-based solutions (NBS) are becoming an increasingly prominent tool to manage climate-related risks, either on their own or as a compliment to structural measures. Land-use planning can facilitate the use of NBS, by maintaining restrictions or creating incentives that protect ecosystems (e.g. wetlands, forests, mangroves) and ensure the ongoing provision of ecosystem services such as flood defence and erosion control. In Peru, for example, a key advance can be in the mainstreaming of NBS into national investment practices. The public investment programme Invierte.pe explicitly establishes that natural infrastructure can be considered part of the public infrastructure projects. This leadership at a central level opens up financial resources to support the implementation of NBS and between 2015 and 2018, public investments projects in NBS reached USD 300 million in Peru in 209 projects.

The Forestry Committee of Ghana has conducted an agroforestry initiative to promote plantation of trees and cocoa in the same geographical areas, which has led to mitigating farmers’ vulnerability to climate change (Kalame et al., 2011[18]). The Committee’s agroforestry initiative has promoted equitable land-sharing and free access to fertile lands within forest reserves for crop cultivation and subsequent commercial marketing. The Committee provides the seedlings to farmers in rural communities and then buy regenerated seedlings to plant in vulnerable areas to implement, for instance, flood protection measures.

In Peru, the Ministry of Environment, along with other agencies, has worked to restore water channels and reservoirs to increase resilience to drought in the high Andean region. This area of Peru is particularly vulnerable to variability in seasonal patterns and reduction in surface water run-off, as well as frost and extreme events such as hailstorms (Kapos et al., 2019[19]).

Capacity limits at the local level is a crosscutting issue which can create challenges for implementation on the ground. In all three countries, local governments face significant capacity constraints, meaning limited resources (human, technical, financial) needed to cover a wide range of priorities. CCA and DRR investments must compete against the demand for funding other development priorities, which often have more immediate visibility and pay-off. In Ghana, for example, important progress has been made in enhancing capacity at the national level, e.g. to collect and use climate data and for this to inform national planning and reporting processes. The National Climate Change Policy, however, notes the need for further capacity-building at the district level, where policy implementation takes place (MESTI, 2015[20]). This includes greater awareness of the climate policy, what it requires of local governments, and the associated resource needs (Asante et al., 2015[21]).Box 2.1 provides examples of approaches to local capacity building.

Capacity constraints at the local level illustrate the importance of policy coherence between CCA and DRR. In the Philippines, for example, laws under multiple government agencies require the preparation of a plethora of plans, estimated to be over 30 in total (GOV.PH, 2017[5]). The sheer number of requirements often leads to low absorption of guidelines coming from the national level. Instead, new and separate requirements for planning and reporting can impose significant administrative burdens and pressure on already stretched local government units. In addition, confusion can arise in implementation when national guidance lacks technical coherence. For example, in Peru, the DRR and the CCA communities use different definitions for the word “exposure”. In the Philippines, different national institutions promote slightly different versions of the same tool, such as the Climate Disaster Risk Assessment. This in turn impairs subsequent planning and implementation processes, including efforts to access domestic CCA and DRR funds.

One important opportunity for avoiding the re-creation of existing risks or the creation of new risks is the recovery and reconstruction phase following a disaster. The Sendai “building back better” principle is “the use of the recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction phases after a disaster to increase the resilience of nations and communities through integrating disaster risk reduction measures into the restoration of physical infrastructure and societal systems, and into the revitalization of livelihoods, economies, and the environment” (UNDRR, 2017[22]). In short, the recovery and reconstruction phase after a disaster should be used to rebuild in a way that prevents the same hazards from leading to the same impacts. This can be done through changes in land-use planning (e.g., deciding not to rebuild in an area of high vulnerability), the application or renewed enforcement of regulation (e.g., ensuring building codes account for risks, such as earthquakes), or rethinking organisational measures, such as early warning systems and evacuations routes (Hallegatte, Rentschler and Walsh, 2018[23]). For example, in the Philippines, improvements in early warning systems were made after Typhoon Yolanda. As the Philippines has so many regional languages, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) did not have a local term to properly communicate the phenomenon of a storm surge to all areas hit by the disaster. After the disaster, PAGASA has worked with linguists to craft simpler meteorological terms to ensure that the dangers from disaster risks are fully understood by all.

A tension that can hinder the implementation of the “build back better” principle is the need for rapid recovery needs versus the time required for undertaking proper risk analysis. This tension was visible in Peru, where the Authority for Reconstruction with Changes (ARRC) was created in 2017, with the goal of implementing a resilient reconstruction process in the aftermath of the damaging 2017 El Niño Costero. Created as an autonomous authority to implement a comprehensive reconstruction plan in the 13 regions affected by this climate-related disaster, ARRC was allocated a significant budget of USD 7.8 billion to rebuild public infrastructure and housing in a more resilient way, which included a comprehensive flood control project in 19 coastal rivers (PCM, 2019[24]). However, despite the well thought out process, time delays, political pressures and capacity gaps have not allowed a comprehensive analysis of where and how to rebuild in a more resilient way. For example, the identification of very high and non-mitigatable risk zones, which would require relocation, was particularly politically challenging. The disbursement of funds has also been slow - with only 36% of the allocated budget transferred, by mid-2019. This has led to questioning of its effectiveness.

One way to overcome this tension is for governments to put ex-ante measures in place that ensure clarity around the reconstruction process. For example, governments should have a contingency plan that allocates responsibility among government agencies (Hallegatte, Rentschler and Walsh, 2018[23]). This plan should also clearly set out how climate change and overall resilience should be considered in the reconstruction process. In addition, contingent financial arrangements—such as contingent credit lines or insurance products can ensure that financing is immediately available and is not delayed by budgetary procedures. This is described further in the following section.

copy the linklink copied!Financing DRR and CCA at the national level

Determining the amount of resources to be allocated towards managing climate-related disaster risks depends on what level of residual risk the country considers acceptable and what resource constraints it faces. It is neither technically nor financially feasible to aim to achieve a “zero risk” level, as there are usually competing demands and more productive allocation choices for available resources (OECD, 2014[25]). Complex decisions regarding the acceptability of risk are routinely faced in decisions on managing disasters, such as setting flood safety standards or defining flood zones (OECD, 2013[26]). Often it is large-scale disasters that prompt countries to revisit the acceptable levels of risks implicit in their policies and measures (OECD, 2013[27]). For example, countries commonly revisit flood defence standards following a hurricane or major storm. A reactive approach such as this, however, may lead to areas recently affected by disasters receiving the bulk of financing, rather than it being used for investments in risk reduction, or in defining an evidence-based policy at the national level (OECD, 2014[28]).

Investments in CCA AND DRR measures can come from a diverse set of funding mechanisms and it is often difficult to get a clear picture on total budgets available. The resources are spread across different budget lines and levels of governments in most countries (OECD, 2018[29]). With the growing demand for risk prevention investments in a changing climate, improved mapping of national resource mobilisation for DRR and CCA should be a priority. Ghana, Peru, and the Philippines all have measures in place to track spending on CCA, DRR, or both, as described in Table 2.1.

There is evidence of general under-investment in ex ante risk reduction and a bias towards reliance on ex-post response. Although the recording of expenditures for ex-ante risk reduction spending versus ex-post expenditures is incomplete (OECD, 2018[29]), existing evidence suggests that countries tend to allocate significantly more funds to disaster response than disaster risk reduction. Reasons for the ex-post bias in spending include:

-

lack of incentives (investments to build resilience often do not produce visibility or immediate gains or benefits);

-

low levels of risk awareness coupled with lack of willingness to pay upfront;

-

moral hazard coupled with capacity gaps (expectations of government compensation ex-post impedes upfront investments by subnational governments, households and businesses);

-

high political visibility for ex-post assistance (OECD, 2014[25]).

Both Peru and the Philippines have made great efforts in recent years to counter the ex-post bias by increasing investments in prevention. In Peru, over two thirds of all disaster management funds go to ex-ante prevention and preparedness measures compared to post-disaster response. In 2010, the Philippines introduced the Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) Act. This led to the creation of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Fund, 30% of which is put aside in a Quick Response fund for relief and response, and 70 % for recovery programmes (GOV.PH, 2010[30]). At the same time, the national government has encouraged agencies to incorporate programmes and projects for disaster resiliency – mitigation and preparedness – in their respective agency budgets. The National Budget Priorities Framework, issued annually by the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) has, since 2014, included resilience building and climate change adaptation among the priorities. Overall allocations for disaster risk reduction and management in the Philippines have been steadily increasing over the past decade, which in part can be explained by an increasing political focus on DRR and by the growing expenses from damages from increasingly intense typhoon events.

Many stakeholders interviewed for this study expressed the potential of targeted grants in facilitating a focus on CCA and DRR across sectors and levels of government, especially when demand for competing resources is high. With some consistency, they provide valuable opportunities for relevant stakeholders to build capacity and to identify examples of good practice. In the Philippines, the People's Survival Fund (PSF) is a targeted grant for projects that address the impacts of disasters and climate change. The annual PHP 1 billion (USD 22.2 million) fund was established as a long-term financing stream to support local governments in their adaptation efforts, and in turn, support DRR activities. However, despite the amount of funding available in the PSF, only 6 projects have been approved so far. It is currently technically challenging to get a proposal approved, as applicants need to demonstrate a stringent vulnerability assessment and the effectiveness of their proposed interventions before submitting a proposal. At the same time, projects that receive funding must be well thought through and include a clear adaptation component.

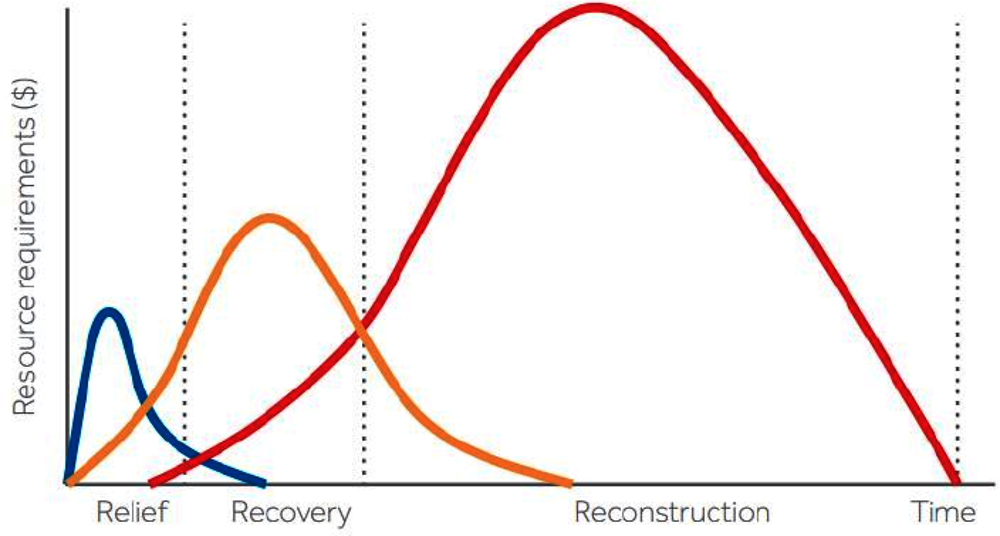

Even with the best investments in disaster prevention or climate change adaptation, no government can fully protect itself from the costs of extreme events. In addition to clear funding for ex-ante prevention, a wide disaster risk-financing toolkit is becoming more largely available to governments to facilitate post-disaster relief, recovery and reconstruction and limit related fiscal risks. The financial requirements for these phases will not be the same and they will not always be needed at the same time, as seen in Figure 2.1. For example, relief activities such as rescue and provision of temporary shelters, are not the largest component of post disaster spending, however funds need to be available immediately.

Governments can ensure liquidity after disasters by (1) maintaining sufficient reserve funds, (2) arranging for contingent credit facilities, or (3) using insurance schemes to transfer risk (Ghesquiere and Mahul, 2010[32]). This difference in timelines and costs for the relief, recovery and reconstruction raises the issue of whether it is more efficient for the government to retain the risk (e.g. reserve funds) or transfer the risk to the private sector (e.g. insurance). In many cases, the answer is that a combination of different risk retention or risk transfer instruments compatible with the financing requirements of each phase is preferable. For lower risk layers, risk retention instruments are more cost efficient while risk transfer instruments are more appropriate for higher risk layers (Ghesquiere and Mahul, 2010[32]) (OECD, 2015[33]). The expected increase in the severity and frequency of extreme disaster events as a result of climate change requires countries to examine their approaches to disaster risk financing with the aim of encouraging the availability and affordability of disaster insurance coverage (Wolfrom and Yokoi-Arai, 2016[34]).

Financing DRR and CCA is a long-term process, and the piloting of various financing mechanisms, in some cases with support from development partners, can support the development of solid disaster risk financing strategies. For example, in the Philippines, technical assistance from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has allowed the Ministry of Finance to explore the feasibility of a Philippine City Disaster Insurance Pool. Initial coverage includes earthquakes and typhoons, with the possibility of expanding this to also include floods. One of the advantages of such an insurance pool is that upon the occurrence of a triggering event, payments are made to governments within 15 business days (ADB, 2018[35]). For vulnerable groups, this means that they can bounce back much quicker from a disaster as they do not have to wait for the oftentimes lengthy release of disaster aid by the international community. This in turn prevent these communities from falling into a spiral of poverty. However, for insurance pilots to translate into sustained strategies, they must include clear exit, replication or scale-up plans. In addition, across the case studies further sensitisation and education of the general public on micro risk insurance products is needed before coverage can be increased.

Insurance instruments should be part of an integrated approach to climate and disaster risk financing. Public funds used for climate and disaster risk finance and insurance can leverage substantial amounts of private capital. For example, funds made available to countries to finance insurance premiums can secure a much larger amount of private capital to compensate for damage, thereby contributing to transfer the risks to the private sector. However, in many countries, both public and private insurance coverage is limited, with insurance payments seen as competing for investments in other development priorities. Political attention on climate change can potentially be leveraged to make instruments more largely available and reduce their costs

All countries have contingency reserves in place, however, they vary in structure. In Peru, the contingency reserve managed by the Institute of Civil Defence has quick disbursements channels to finance emergency recovery and immediate preparedness for major disasters. It has disbursed around USD 12 million on average per year since 2003. In addition, a Fiscal Stabilisation Fund can be utilised when a major emergency is declared, and a macroeconomic assessment demonstrates an impact on the country’s fiscal stability. In the Philippines, there is funding set aside for quick response. A challenge noted by both countries is that these response instruments are currently ill suited to cover costs associated with the recovery from slow-onset events such as drought. In addition, amounts set aside is informed by the cost of past events, but this does not consider potentially more damaging impacts due to climate change.

Development partners have provided significant assistance in terms of climate and disaster risk financing and insurance. Peru, for instance, has agreed on several contingent credit lines with different development co-operation providers such as Development Bank of Latin America (CAF), the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Japan and the World Bank, totalling about USD 4 billion between 2010 and 2015 (OECD/The World Bank, 2019[36]). The Philippines has also benefited from a CAT-DDO (i.e. Disaster Risk Management Development Policy Loan with a Catastrophe-Deferred Drawdown Option). The World Bank disbursed the first CAT-DDO to the Philippines in December 2011 after Tropical Storm Sendong (Washi), and approved the second Cat-DDO (CAT-DDO 2) in December 2015 following Typhoon Ompong (Mangkhut). The Philippines can access the new credit line upon “a state of calamity” declared by the President.

copy the linklink copied!Coherence in monitoring and evaluation frameworks

For national approaches in CCA and DRR to achieve set objectives and be sustainable, mechanisms must be in place to monitor progress and assess whether the approach taken is the right one. This should also guide any adjustments needed. This can for example be in response to changes in the nature of the climate or disaster risks, in the exposures to those risks, or in emerging good practice in addressing them. All countries have a diverse set of reporting mechanisms in place to monitor domestic policy processes. Most countries also have auditing mechanisms to assess whether and to what extent domestic expenditures are in compliance with national and international policy goals, are allocated in accordance with existing rules, regulations and principles of good governance, and if they are allocated in a cost-effective manner (OECD, 2015[37]). A wealth of data is therefore available that can inform domestic reporting processes for CCA and DRR. The objective of this section is to examine the potential for coherence in the approaches commonly applied for monitoring, evaluating and learning for CCA and DRR.

International and domestic reporting mechanisms for DRR

Accountability is a key component of the Sendai Framework, reflected by a set of 38 global indicators to track progress towards the seven targets of the Framework. The indicators aim to measure progress in preventing the creation of new risks, reducing existing risks, and increasing resilience to withstand residual risk. While global progress is assessed biennially by UNDRR, this is informed by national progress reports. Complementing reporting on the 38 global indicators, custom targets and indicators allow Member States to measure domestic progress against their own Sendai Framework priorities. This can include input indicators such as public policy measures in place that support the implementation of the Sendai Framework priorities, or output indicators to measure the reduction of risk or increase in resilience. The information collected is also used to monitor disaster risk-related indicators of SDG 1 End poverty in all its forms everywhere, SDG 11 Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable and SDG 13 Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. The extent to which this data is differentiated by disaster type, it can also provide a valuable information when measuring progress on CCA (see Table 2.2. ).

The Sendai Framework Monitor, an online monitoring system, provides a set of common standards and principles for reporting on the 38 indicators. Given the reliance on countries self-reporting to assess global progress, the platform ensures that data submitted by Member States is comparable in nature. Differing levels of technical and human capacities nonetheless result in variable quality of the data and subsequent reporting. In fact, the Sendai Framework Readiness Review 2017 found significant diversity in the capacity of countries to report against the agreed indicators (UNDRR, 2017[38]).

Launched in March 2018, the Sendai Framework Monitor provides an online platform for UN Member States to report on progress against the seven global targets of the Sendai Framework, corresponding SDGs 1, 11 and 13, as well as on customised national indicators. It highlights progress made in implementing the Sendai Framework, while at the same time providing a tool to guide risk-informed policy decisions and the subsequent allocation of resources.

The platform is organised into three modules:

-

Module 1: Data entry related to the seven global targets of the Sendai Framework, agreed by all Member States.

-

Module 2: Data entry related to custom targets and indicators, as defined by individual Member States to support the monitoring of their National Strategies for Disaster Risk Reduction.

-

Module 3: An analytics module, which allows validated information to be filtered for comparison by target, indicator, year and/or region and accessed as charts, maps and tables. Only this module is publicly available and facilitates comparison across countries and over time.

Complementary Technical Guidance Notes outline the reporting methodology for each target and indicator, including minimum dataset requirements as well as the recommended optimal dataset (including disaggregation by gender, age, etc.).

Finally, UNDRR has regional offices that provide comprehensive capacity development support in their respective regions targeted at nationally-nominated Sendai Framework Focal Points, and as appropriate, also representatives from National Statistical Offices and other stakeholders.

Source: (UNDRR, 2019[39])

International and domestic reporting mechanisms for CCA

The Paris Agreement establishes a global goal on adaptation of enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change, with a view to contributing to sustainable development and ensuring an adequate adaptation response in the context of the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015[40]). Compared to the Sendai Framework, there are no agreed indicators to monitor progress. Instead, each Party to the UNFCCC can undertake monitoring, evaluation and learning as appropriate given country circumstances. Parties are encouraged to include this information in voluntary adaptation communications to the UNFCCC. Reporting, monitoring and review is also one out of four elements included in the technical guidelines for the national adaptation plan process (UNFCCC, 2012[41]).

Despite monitoring and evaluation not being a requirement for CCA under UNFCCC, many countries such as Kenya (Mutimba et al., 2019[42]) and Colombia (Cruz, 2019[43]) have developed domestic reporting systems. The objective of such systems is commonly twofold: i) continuous learning to understand the country’s climate change risks and vulnerabilities that in turn can inform which approaches are effective in reducing climate risks; and ii) accountability to ensure that resources allocated for adaptation are effective in achieving set objectives (OECD, 2015[37]). Faced with resource constraints, countries tend to draw on domestic sources of data already available (OECD, 2015[37]) (EEA, 2015[44]).

In Ghana, for example, regulatory measures in place mandate every government implementing agency to monitor and evaluate their respective policies, programmes and projects, guided by national indicators, baselines and targets identified in the National Medium Term Policy Framework and in the Sector and District Planning, a process overseen by the National Development Planning Commission (NDPC). As a result, Ghana’s NDC, National Climate Change Policy, National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy, as well as the NAP Framework all refer to the reporting frameworks already in place rather than propose additional adaptation-specific reporting processes. While guidelines have been developed to integrate NDC priorities in local medium term development plans, a process that ensures that climate issues are monitored and evaluated through standard NDCP processes, it does for the time being not include a complementary focus on DRR. Including a complementary focus on DRR in the guidelines could help identify areas of coherence between CCA and DRR.

Areas of convergence in reporting for CCA DRR

At the international level, the policy processes are guided by different reporting framework that have been negotiated through their separate processes. Table 2.2. reveals that there already is considerable overlap and further scope for coherence. In practice, countries are also building coherence into their reporting.

Despite the different approaches and focus of DRR and CCA reporting at domestic and international levels there is considerable scope for coherence across the respective monitoring, evaluation and learning frameworks. For example, both processes require a good understanding of risks, exposures and vulnerabilities. While the scope of CCA and DRR risk assessments will vary, both consider weather-related risks. There will also be some overlap in the associated policy processes and areas of implementation given the joint focus on climate risks. When developing reporting frameworks for CCA and DRR, a starting point can therefore be to review what information is already available on CCA and DRR respectively. A similar link to SDG planning and implementation processes may also be encouraged as noted in Table 2.2.

As part of the process of formulating Peru’s National Adaptation Plan, a complementary monitoring and evaluation system is being developed that includes a detailed set of indicators, goals and baselines. The proposed outcome indicators all include a DRR component. While the reporting system will be managed by the Environment Information National System, there are efforts to ensure that it builds on DRR indicators and reporting process, but also aligns with Peru’s SDGs reporting process being developed in parallel by the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics. In the Philippines, the responsibility for reporting on CCA and DRR is assigned to different government units, with a focus on progress in implementation rather than results. The possibility of bringing the management of climate change (adaptation and mitigation) and DRR together in one ministry is, however, being discussed. This would facilitate greater coherence in many aspects of CCA and DRR, including monitoring and reporting.

Capacity constraints can present a barrier to the implementation of reporting frameworks (OECD, 2015[37]). This includes the capacity to collect, record and report information across all levels. Co-ordinating bodies at the global level (e.g. UNDRR or UN Statistics Division) can play an instrumental role in promoting potential areas of coherence by, for example, encouraging consistencies in the baselines and indicators used to monitor international frameworks. Clear guidance on data collection and use for monitoring and evaluation can ensure that the data available is at a certain standard, more easily facilitating multiple uses of it (Clarke et al., 2018[47]) (IEAG, 2014[48]).

Complementing efforts to report on outcomes and impacts, it is important to also monitor progress in aligning institutional mechanisms with the objective of policy coherence. The OECD Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development (PCSD) Framework identifies eight building blocks that represent key institutional dimensions that underpin coherent SDG implementation. While this framework was developed with a focus on the SDGs, it has also been applied to other contexts such as water governance (OECD, 2018[49]) and long-term low emission development strategies (Aguilar-Jaber et al., forthcoming[50]). It can also inspire an assessment of the level of coherence in planning and implementing CCA and DRR (see Table 2.3).

Finally, for the information generated by monitoring and evaluation to inform subsequent policy processes, feedback mechanisms must be in place that facilitate the exchange of information. Since the implementation of monitoring, evaluation and reporting frameworks for CCA and DRR are still in their relatively early stages in many countries, the extent to which such feedback mechanisms are in place is not clear yet. This is not unique to the context of CCA and DRR. The uncertain nature of climate and disaster risks, and the importance of a flexible approach, however, highlight the need for continuous learning. Development co-operation can, for example, play a valuable role in supporting partner countries in strengthening data governance and the capacity of national statistical offices, both crucial for monitoring, evaluating and reporting CCA and DRR.

References

[35] ADB (2018), Philippine City Disaster Insurance Pool: Rationale and Design, Asian Development Bank, Manila, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/479966/philippine-city-disaster-insurance-pool-rationale-design.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[50] Aguilar-Jaber, A. et al. (forthcoming), Long-term low emissions development strategies: cross-country experience, OECD Publishing.

[21] Asante, F. et al. (2015), Climate change finance in Ghana, Overseas Development Institute (ODI), London, http://www.odi.org.uk/projects/2537-climate-finance-climate-change-fast-start-finance (accessed on 27 August 2019).

[14] Butler, J. et al. (2015), “Integrating Top-Down and Bottom-Up Adaptation Planning to Build Adaptive Capacity: A Structured Learning Approach”, Coastal Management, Vol. 43/4, pp. 346-364, https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2015.1046802.

[17] CENEPRED (2017), “Implementación del Plan Nacional de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres : Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Gestión de Riesgo de Desastres - ENAGERD 2017” 01, p. 123, https://dimse.cenepred.gob.pe/src/informes_grd/Informe2017_2.pdf (Accessed on 27 August 2019).

[11] CICERO (2019), Report on Workshop on Physical modeling supporting a storyline approach, https://www.wcrp-climate.org/images/grand_challenges/climate_extremes/Documents/report_workshop_Oslo_24-26April2019.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2019).

[47] Clarke, L. et al. (2018), “Knowing What We Know – Reflections on the Development of Technical Guidance for Loss Data for the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction”, PLOS Currents Disasters, Vol. 1, https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.dis.537bd80d1037a2ffde67d66c604d2a78 (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[43] Cruz, L. (2019), sNAPshot: Colombia’s Progress in Developing a National Monitoring and Evaluation System for Climate Change Adaptation, NAP Global Network, http://napglobalnetwork.org/resource/snapshot-colombias-progress-in-developing-a-national-monitoring-and-evaluation-system-for-climate-change-adaptation/ (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[44] EEA (2015), “National monitoring, reporting and evaluation of climate change adaptation in Europe”, EEA Technical report, Vol. No 20/2015, https://doi.org/10.2800/629559.

[8] European Commission (2015), A European research and innovation roadmap for climate services, European Commission, https://doi.org/10.2777/702151.

[9] Ford, J. et al. (2018), “Vulnerability and its discontents: the past, present, and future of climate change vulnerability research”, Climatic Change, Vol. 151/2, pp. 189-203, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2304-1.

[3] Ghana (2017), Mainstreaming Ghana’s Nationally Determined Contributions (GH-NDCs) into National Development Plans, https://www.gcfreadinessprogramme.org/sites/default/files/NDC%20Mainstreaming%20Guidance%20Report.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[32] Ghesquiere, F. and O. Mahul (2010), Financial protection of the state against natural disasters : a primer, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/227011468175734792/Financial-protection-of-the-state-against-natural-disasters-a-primer (accessed on 17 October 2019).

[10] GIDRM (n.d.), Coherence in Practice: Philippines, https://www.gidrm.net/en/coherence/coherence-in-practice/pilot-country-philippines (accessed on 19 November 2019).

[5] GOV.PH (2017), Local Planning Illustrative Guide: Preparing and Updating the Comprehensive Development Plan (CDP), https://dilg.gov.ph/PDF_File/reports_resources/dilg-reports-resources-2017110_298b91787e.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2019).

[30] GOV.PH (2010), R.A. No. 10121, “Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010”, https://www.lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra2010/ra_10121_2010.html (accessed on 25 July 2019).

[23] Hallegatte, S., J. Rentschler and B. Walsh (2018), Building Back Better: Achieving resilience through stronger, faster, and more inclusive post-disaster reconstruction, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29867 (accessed on 5 April 2019).

[48] IEAG (2014), A World that Counts: Mobilising the data revolution for sustainable development, The United Nations Secretary-General’s Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development, https://www.undatarevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/A-World-That-Counts.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[12] IPCC (2018), Global warming of 1.5°C An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 16 December 2019).

[18] Kalame, F. et al. (2011), “Modified taungya system in Ghana: a win–win practice for forestry and adaptation to climate change?”, Environmental Science & Policy, Vol. 14/5, pp. 519-530, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2011.03.011.

[19] Kapos, V. et al. (2019), The Role of the Natural Environment in Adaptation, Background Paper for the Global Commission on Adaptation, Global Commission on Adaptation, Rotterdam and Washington, D.C., https://cdn.gca.org/assets/2019-10/RoleofNaturalEnvironmentinAdaptation_V2.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2019).

[4] Leitner, M. et al. (2018), Draft guidelines to strengthen CCA and DRR institutional coordination and capacities, PLACARD project, https://www.placard-network.eu/wp-content/PDFs/PLACARD-Insitutional-strengthening.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[20] MESTI (2015), Ghana National Climate Change Master Plan Action Programmes for Implementation, The Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation, Republic of Ghana (MESTI), https://www.un-page.org/files/public/ghanaclimatechangepolicy.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[42] Mutimba, S. et al. (2019), sNAPshot: Kenya’s Monitoring and Evaluation of Adaptation - Simplified, integrated, multilevel, Nap Global Network, http://napglobalnetwork.org/resource/snapshot-kenyas-monitoring-and-evaluation-of-adaptation-simplified-integrated-multilevel/ (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[16] OECD (2019), Responding to Rising Seas: OECD Country Approaches to Tackling Coastal Risks, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264312487-en.

[29] OECD (2018), Assessing the Real Cost of Disasters: The Need for Better Evidence, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264298798-en.

[49] OECD (2018), “Implementing the OECD Principles on Water Governance: Indicator Framework and Evolving Practices”, OECD Studies on Water, https://doi.org/9789264292659-en.

[51] OECD (2018), Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development 2018: Towards Sustainable and Resilient Societies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301061-en.

[33] OECD (2015), Disaster Risk Financing: A global survey of practices and challenges, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264234246-en.

[37] OECD (2015), National Climate Change Adaptation: Emerging Practices in Monitoring and Evaluation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264229679-en.

[25] OECD (2014), Boosting Resilience through Innovative Risk Governance, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264209114-en.

[28] OECD (2014), Seine Basin, Île-de-France, 2014: Resilience to Major Floods, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264208728-en.

[26] OECD (2013), Water and Climate Change Adaptation: Policies to Navigate Uncharted Waters, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264200449-en.

[27] OECD (2013), Water Security for Better Lives, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264202405-en.

[36] OECD/The World Bank (2019), Fiscal Resilience to Natural Disasters: Lessons from Country Experiences, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/27a4198a-en.

[53] Palutikof, J.P., Street, R.B. & Gardiner, E.Pet al. (2019), Decision support platforms for climate change adaptation: an overview and introduction, Climatic Change 153, 459–476 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02445-2.

[24] PCM (2019), Plan Integral para la Reconstrucción con Cambios (PIRCC), Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros (PCM), http://www.rcc.gob.pe/plan-integral-de-la-reconstruccion-con-cambios/ (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[31] Pillay, K. (2016), “Climate Risk Management: Opportunities and Challenges for Risk Pooling”, Small States Digest, No. 2016/2, Commonwealth Secretariat, London, https://dx.doi.org/10.14217/5jln4p72226b-en.

[45] PreventionWeb (n.d.), Sendai Framework Indicators, https://www.preventionweb.net/sendai-framework/sendai-framework-monitor/indicators (accessed on 10 October 2019).

[13] Shepherd, T. et al. (2018), “Storylines: an alternative approach to representing uncertainty in physical aspects of climate change”, Climatic Change, Vol. 151/555–571 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2317-9.

[7] Street, R. (2019), “How could climate services support disaster risk reduction in the 21st century”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol. 24/March, pp. 28-33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.12.001.

[39] UNDRR (2019), United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: 2018 Annual Report, UNDRR, Geneva, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/64454_unisdrannualreport2018eversionlight.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[38] UNDRR (2017), Disaster-related Data for Sustainable Development: Sendai Framework Data Readiness Review 2017. Global Summary Report, UNDRR, Geneva, https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-data-readiness-review-2017-global-summary-report (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[22] UNDRR (2017), Terminology - UNDRR, UNDRR, Geneva, https://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology (accessed on 4 July 2019).

[2] UNDRR (2015), Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, UNDRR, Geneva, https://www.unisdr.org/we/coordinate/sendai-framework (accessed on 17 October 2019).

[1] UNDRR (2005), “Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters”, UNDRR, Geneva, https://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/publications/1037 (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[46] UNDRR (n.d.), The Sendai Framework and the SDGs, https://www.unisdr.org/we/monitor/indicators/sendai-framework-sdg (accessed on 10 October 2019).

[6] UNFCCC (2017), Opportunities and options for integrating climate change adaptation with the Sustainable Development Goals and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, UNFCCC, Bonn, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/techpaper_adaptation.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2020).

[40] UNFCCC (2015), Paris Agreement, UNFCCC, Bonn, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 26 March 2020)

[41] UNFCCC (2012), National Adaptation Plans: Technical guidelines for the national adaptation plan process, Least Developed Expert Group, UNFCCC, Bonn, https://unfccc.int/topics/adaptation-and-resilience/workstreams/national-adaptation-plans-naps/guidelines-for-national-adaptation-plans-naps (accessed on 26 March 2020)

[15] WMO & GFCS (2016), Climate Services for Supporting Climate Change Adaptation: Supplement to the Technical Guidelines for The National Adaptation Plan Process, World Meteorological Organization (WMO), Geneva, https://library.wmo.int/doc_num.php?explnum_id=7936 (accessed on 26 March 2020)

[34] Wolfrom, L. and M. Yokoi-Arai (2016), “Financial instruments for managing disaster risks related to climate change”, OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends, Vol. 2015/1, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/fmt-2015-5jrqdkpxk5d5.

← 1. Survey responses, and to note that 497 municipalities did not respond to the question and 637 did not participate in the survey

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/3edc8d09-en

© OECD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.