5. Enhancing the implementation of the State of Mexico’s administrative liability system for public officials

This chapter examines the role of the administrative liability regime for public officials in the State of Mexico and its effectiveness in ensuring accountability in its public integrity system. It illustrates the recent legal framework on administrative responsibilities, which provides for a comprehensive and solid foundation to enforce integrity rules and standards but still requires further guidance, capacity and support to favour its implementation, as well as streamlining it. The chapter also addresses existing co-operation and exchange of information mechanisms among relevant actors, emphasising the oversight role of the Office of the Comptroller of the State of Mexico (SECOGEM) on administrative liability units in public entities. It recommends leveraging on existing registries on administrative proceedings and sanctions, as well as on the Co-ordination Committee of the State Anti-corruption System, where enhanced co-ordination with criminal enforcement actors could be established. A considerable amount of information and data on administrative liability enforcement and its performance is collected, and the chapter proposes ways to further exploit them for prevention, accountability, and deterrence purposes, such as by making them available to the public and periodically communicated to the State Anti-corruption System.

Enforcing integrity rules and standards is a necessary element to prevent impunity among public officials and to ensure the credibility of the integrity system as a whole. Without effective responses to integrity violations, and the application of sanctions in a fair, objective and timely manner, an integrity system is not able to ensure accountability and build the necessary legitimacy for integrity rules and frameworks to deter people from misbehaving. Furthermore, a consistent application of rules in the public sector contributes to building citizens’ confidence in the government’s ability to tackle corruption effectively and – more generally – to fuel trust in the integrity system as a whole.

This chapter examines the role of the administrative liability regime for public officials in the State of Mexico1 and its effectiveness in ensuring accountability in its public integrity system. It assesses the strengths and weaknesses of the current framework against international standards and norms. In particular, it builds on the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity, which calls States to ensure that enforcement mechanisms – including disciplinary and administrative ones – provide appropriate responses to all suspected violations of integrity standards by public officials (OECD, 2017[1]). Applying the OECD Recommendation to the State of Mexico, this chapter analyses:

the extent to which the recently-adopted framework of administrative responsibilities is applied fairly, objectively and timely among the State of Mexico’s public officials

whether mechanisms for co-operation, exchange of information and collaboration are effectively in place among all relevant institutions such as the Ministry of Control of the State of Mexico (Secretaría de la Contraloría del Gobierno del Estado de Mexico, SECOGEM), Internal Control Bodies in public entities (Órganos Internos de Control, OIC), the Administrative Justice Tribunal, and the Anti-corruption Public Prosecutor Office

how the administrative liability system of the State of Mexico collects and uses relevant data, ensures its transparency and evaluates its performance.

The implementation of the legal framework on administrative liability of public officials requires secondary regulations to fill procedural gaps and ensure its full application

The OECD Recommendation stresses the need for fairness, objectivity and timeliness in the enforcement of public integrity standards, calling on countries to apply these key principles in all enforcement regimes, including the disciplinary and administrative ones. These three elements contribute to building or restoring public trust in both the standards and enforcement mechanisms, and should be applied during investigations, as well as at the level of court proceedings and imposition of sanctions.

In the State of Mexico the anti-corruption reform adopted to implement the State of Mexico's Anti-corruption System Law in 2017 included a regulation on administrative liability and proceedings, which is the Law of Administrative Responsibilities of the State of Mexico and Municipalities (Ley de Responsabilidades Administrativas del Estado de México y Municipios, LRAEM). It establishes sanctions for public officials who commit administrative offences, which in turn are divided between serious ones - such as diversion of resources, embezzlement and misuse of resources - and non-serious ones – such as non-compliance with functions, attributions and tasks entrusted to the person or failure to submit declarations of assets and interests in a timely manner (Box 5.1). The LRAEM also regulates the administrative liability regime of private - natural and legal - persons linked to serious offences, such as bribery, use of false information and collusion in public contracts (Article 68).

A number of typologies of sanctions are established depending on the gravity of the offence, the economic consequence and the subject committing it (Box 5.2). The responsibility to impose sanctions also depends on the seriousness of the offence, whereas for non-serious administrative offenses it is SECOGEM and the Internal Control Bodies of public entities (OIC), while for serious administrative offences it is the Administrative Justice Tribunal of the State of Mexico.

The LRAEM establishes, in its Article 79, the following sanctions for non-serious breaches of public officials:

Suspension of employment, office or commission without pay for a period of no less than 1 day and no more than 30 calendar days.

Temporary disqualification from holding public service jobs, positions or commissions and from participating in acquisitions, leases, services or public works for a period of 3 months to 1 year.

At the same time, Article 82 of the LRAEM establishes the administrative sanctions that could be imposed for the commission of serious administrative offenses, which are:

Suspension of employment, office or commission from 30 to 90 days.

Temporary disqualification from performing public service jobs, offices or commissions and from participating in public purchases, leases, services or works.

In the event that the serious administrative misconduct generates economic benefits for the public officials themselves, their business partners or relatives, an economic sanction shall be imposed amounting up to two times the benefits obtained.

The administrative sanctions that can be imposed for illegal conduct of both individuals or legal persons are established in Article 85 of the Law of Administrative Responsibilities of the State of Mexico and Municipalities as follows:

For natural persons: economic sanction; temporary disqualification from participating in acquisitions, leases, services or public works; compensation for damages caused to the State or Municipal Public Treasury, or to the assets of public entities.

For legal persons: economic sanction; temporary disqualification from participating in acquisitions, leases, services or public works; suspension of commercial, contractual or business activities; dissolution of the respective company; and compensation for damages caused to the State or Municipal Public Treasury, or to the assets of public entities.

Source: OECD based on materials provided by the State of Mexico.

As for the scope of application of the regulation, according to the Mexican Constitution, a public official is considered to be any person who performs an employment, position or commission in any of the branches of the State, autonomous bodies, in municipalities and auxiliary bodies, as well as the incumbents or those who act in companies of state or municipal participation, societies or associations assimilated to these and in public trusts (Article 130). The LRAEM applies to public officials at the state and municipal levels, but also to the Legislative Power and the autonomous bodies of the State of Mexico. Individuals linked to serious administrative breaches can also be sanctioned, whether natural or legal person, and those who are in a special situation, such as candidates for election, members of electoral campaigns’ teams or transition team between administrations of the public sector and leaders, directors and employees of public sector unions.

The legal framework provides for a comprehensive and solid foundation to enforce integrity rules and standards, which is also coherent with the national framework. However, the significant amount of new procedures and mechanisms requires further efforts to facilitate their implementation and eventually the enforcement of sanctions. Interviews during the fact-finding mission noted that in some ministries there has not been any sanction yet because of the complexity and novelty of the legal framework. In particular, it was stressed that secondary regulation is still needed to implement some aspects of the new legal framework, such as on the possibility to request a public defender,2 as well as on the structure of the internal control bodies that should all count with areas that investigate, conduct and take decisions in administrative liability cases. By duly implementing all the processes and aspects of the LRAEM, SECOGEM would not only avoid impunity or carrying out weak files that could then be annulled, but would also provide guidance and better understanding of mechanisms and legal concepts in the current transition process into the new system of administrative liability. In doing that, efforts should also aim at addressing another challenge highlighted during the fact-finding mission, which is the high degree of formalisation brought by the new legal framework, for instance with respect to the mandatory translation of all documents that are not written in Spanish. The over-formalisation of the legal framework burdens and delays the enforcement activity, thereby undermining the accessibility and fairness of justice but also leading to cases annulled or not be dealt with on the substance for formal requirements that are difficult to meet in practice. To address this challenge, secondary regulation could help streamlining formalistic procedures and requirements identified in the first phase of the LRAEM’s application by authorities taking part in the proceedings such as SECOGEM and the Administrative Tribunal. Should this prove insufficient to overcome some of the rigidities of the new framework, those actors could consider discussing legislative amendments within the State of Mexico Anti-corruption System and then bringing them to the consideration of Congress.

SECOGEM could scale up capacity-building efforts to address novelties of regulation and provide continuous guidance

A key dimension of fair disciplinary and administrative enforcement is ensuring that staff in charge of various phases of proceedings have adequate tools, skills and understanding. This includes providing continuous training and building the professionalism needed to master the relevant legal framework. Indeed, providing guidance, ensuring training and building professionalism of officials in charge of enforcement limits discretional choices, helps addressing technical challenges, ensures a consistent approach of disciplinary and administrative liability action and contributes to reducing the rate of annulled sanctions due to procedural mistakes and poor quality of legal files. For this purpose, guidance material and training programmes are common ways to develop capacity of the relevant staff and to strengthen technical expertise and skills in fields such as administrative law, IT, accounting, economics and finance, which are all necessary areas to ensure effective investigations.

These efforts are particularly needed in the State of Mexico in light of the legal framework adopted in 2017, which envisages proceedings encompassing new roles (Table 5.2), procedures, standards and mechanisms. In particular, administrative liability investigations may be initiated:

by report/complaint (denuncia) through the State of Mexico’s Alert System (Sistema de Atención Mexiquense, SAM) (Box 5.3)

as a result of an audit carried out by the competent authorities or, where appropriate, by external auditors.

In order to strengthen the reporting mechanism for misconducts, SECOGEM put in place the State of Mexico’s Alert System (SAM), a tool that allows citizens to submit their reports/complaints about acts or omissions of public officials who do not comply with their obligations or that affect a public service. This system has been updated and harmonised with the Anti-corruption System of the State of Mexico and Municipalities and the LRAEM, in order to also receive complaints against individuals and companies linked to acts of corruption. The SAM also allows those who submit a report to follow up on its progress as well as the presentation of suggestions for the improvement of public services, or recognising the performance of a public official.

Source: OECD based on materials provided by the State of Mexico.

The investigation procedure begins when the investigating authority (autoridad investigadora), which is either a unit of SECOGEM or the investigative unit in the entities’ internal control bodies, becomes aware of the existence of an alleged breach, which is then assigned a file number, and orders the investigation until its completion, the investigative authority analyses that the findings evidence an administrative fault or presumed responsibility, prepares a report of alleged administrative liability (Informe de Presunta Responsabilidad Administrativa) and sends it to the authority in charge of building the case until the decision (autoridad substanciadora), which may also be within SECOGEM or the unit conducting administrative liability cases in the entities’ internal control bodies.

The investigating authority may file an appeal against the decisions taken by the body conducting the case or deciding authority (autoridad resolutora), which is SECOGEM, a specific unit in the entities’ internal control bodies (in case of non-serious breaches) or the Administrative Tribunal of the State of Mexico (for serious breaches). If the case stems from a complaint from individuals, they may also appeal the classification of the administrative fault and the lack of action to initiate the administrative procedure.

The new legislation spells out a number of legal principles which should be observed throughout the investigative and case-building phases, namely to observe the principles of legality, impartiality, objectivity, congruence, material truth and respect for human rights. On top of these principles, the LRAEM introduced greater procedural guarantees to those undergoing administrative liability proceedings, emphasising that they have the right to an ex officio defender, to be given certified copies of all the documents in the file for the preparation of their due defence, to present arguments, as well as to have their legal situation resolved within a period of no more than 30 working days, which may be extended only once for an equal term when the complexity of the matter so requires, having to justify and motivate the causes for it.

Interviews during the fact-finding mission pointed out that many cases were accumulated because of the formalism of the new legal framework pointed out earlier, which required an update of regulations to align them with the Anti-Corruption System of the State of Mexico and to modify the structure of the internal control bodies and SECOGEM itself. At the same time, the backlog of cases was also due to insufficient expertise and professionalisation of the staff in charge of administrative liability proceedings, such as the preparation of solid legal files. Building skills, experience and professionalism minimises the chance of mistakes through proceedings that endanger the effectiveness and fairness of the whole enforcement system. These weaknesses are particularly meaningful at the municipal level, where interviews highlighted the lack of staff and skills to carry out administrative liability cases. The OECD experience suggests that institutions in charge of co-ordinating disciplinary or administrative liability bodies are usually best placed to strengthen their capacity and to support them in building and sustaining cases, for instance through in-person training programmes or e-learning courses. Hence, SECOGEM could scale up existing training efforts for staff working in administrative liability offices – including at municipal level – focusing on the correct and uniform interpretation and application of procedural rules, including those stemming from the current legal framework.

Currently, the Manual for case-building of administrative procedures (Manual de Substanciación del Procedimiento Administrativo) is under review and will be applicable by the responsibilities units of SECOGEM and the internal control bodies and serve as a guide for case-building in administrative responsibility procedures, from the admission of the report of alleged administrative liability to the corresponding resolution. SECOGEM could accelerate the review process and/or develop tools, manuals and channels of communication to guide and support investigative bodies in preparing cases and respecting the due process rights of the officials under investigation (Box 5.4). In parallel, SECOGEM could also organise more general awareness-raising activities targeting all public officials, whose understanding of the administrative liability system is equally crucial to support, legitimise and adhere to the new regime. The Administrative Justice Tribunal of the State of Mexico should also be involved in these efforts, as it contributes to applying and providing authoritative interpretation to the legal framework.

The United Kingdom’s Civil Service Management Code recommends compliance with the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS)’s Code of Practice on Disciplinary and Grievance Procedures and notifies departments and agencies that it is given significant weight and will be taken into account when considering relevant cases. The ACAS, an independent body, issued the code in March 2015, which encourages:

clear, written disciplinary procedures developed in consultation with stakeholders

respect for rights of the accused: right to information, legal counsel, hearing and appeal.

Australia’s Public Service Commission (APSC) has also published a comprehensive Guide to Handling Misconduct, which provides clarifications of the main concepts and definitions found in the civil service code of conduct and other applicable policies/legislation, as well as detailed instructions to managers on proceedings. The guide also contains various checklist tools to facilitate proceedings for managers such as: checklist for initial consideration of suspected misconduct; checklist for employee suspension; checklist for making a decision about a breach of the Code of Conduct; checklist for sanctioning decision making.

The Comptroller General of the Union (CGU) in Brazil provides various tools for guidance to disciplinary offices including guides, manuals, questions and answers related to the most recurrent issues, as well as an email address to clarify questions related to the disciplinary system.

Source: (ACAS, 2015[2]); (APSC, 2015[3]); (CGU, n.d.[4]);

The oversight role of SECOGEM over offices in charge of administrative liability could be leveraged to promote mutual learning and exchange of good practices

Oversight on and co-ordination among offices responsible for disciplinary or administrative liability in public entities contributes to ensure uniform application of the integrity framework, allows to address common challenges and promotes the exchange of best practices. This requires establishing the legal and operational conditions for sharing information and ensuring co-ordination among entities which could be potentially involved. An oversight body can support such co-ordination efforts.

In the State of Mexico, SECOGEM is the main institution in charge of co-ordinating administrative liability activity in the government entities through the General Directorate of Administrative Responsibilities and the Internal Control Bodies. For this purpose, it has a budget of approximately MXN 27 million for fiscal year 2019, as well as 78 people assigned to the area, 43 of which carry out functions related to administrative liability procedures.

Ensuring dialogue and co-ordination among offices responsible for disciplinary or administrative proceedings is key to improve the coherent implementation and enforcement of the integrity framework. In this context, interviews during the fact-finding mission confirmed that there is no formal mechanism promoting horizontal dialogue among offices in charge of administrative liability, which only get together on an occasional basis. Considering the responsibility of SECOGEM over those offices, its oversight function could be enhanced by developing an on-line platform and promoting regular meetings among relevant areas and units in internal control bodies (OIC) of public entities, along the practice of the Ministry of Public Administration at the federal level (SFP), which organises plenary meetings for OICs of federal entities. Both the platform and the meetings would enable discussing common challenges, proposing improvements and exchanging good practices.

An (electronic) case management tool could improve existing mechanisms for co-operation and exchange of information throughout administrative liability proceedings

Enforcement systems rely heavily on the proactive collaboration of a wide range of actors within and outside any public entity, for instance, to get to know allegations of integrity breaches (e.g. audit reports, asset declarations, human resources management, whistleblowing reports, etc.). This is particularly the case for systems, such as the one in the State of Mexico, which envisage two procedural paths – partly involving different institutions – depending on whether the alleged offence is qualified as serious or non-serious.

The sequencing and complexity of disciplinary and administrative liability enforcement procedures demand efficient co-ordination mechanisms as they leave room for inconsistent application of the legal framework. While some of the causes of inconsistency, such as the lack of implementing regulation, guidance and venues for mutual learning, have been addressed already, this also crucially depends on the existence of mechanisms to smoothly handle cases among all potentially involved actors in a co-ordinated manner.

In this context, interviews during the fact-finding mission highlighted that the State of Mexico Alert System is a helpful tool to effectively manage the complaints from citizens and public officials, which are submitted to SECOGEM and then turned to the relevant internal control body (Box 5.3). The persons submitting the complaint have access to the file and can be contacted to review the information on the acts reported when strictly necessary to collect their statements. When requested, they can also maintain anonymity. Beyond that, the State of Mexico has a system in place to collect data on administrative proceedings and sanctions (Box 5.5), but it does not have a comprehensive mechanism to manage all the steps of cases and allowing all relevant actors to follow, access, or submit relevant information for swift advancement of administrative liability cases.

Pursuant to the “Agreement establishing the guidelines for the registration of administrative procedures and follow-up of sanctions" of 24 March 2004, the State of Mexico’s Comprehensive System of Responsibilities (Sistema Integral de Responsabilidades) keeps records of the procedures of administrative liability and sanctioned public officials.

With regards to sanctions, the register contains the following data:

The agreements and decisions issued at the beginning, during and at the conclusion of administrative liability proceedings by SECOGEM, the Internal Control Bodies of the central sector and auxiliary bodies, as well as the state public trusts.

Administrative liability sanctions imposed on public officials of the State and municipalities.

Payments made as a result of compensatory liability and economic sanctions.

Decisions by administrative jurisdictional authorities that impose, confirm, modify or invalidate a sanction.

Decisions of criminal courts that impose as a sanction the removal or disqualification of a person from public service.

For the informative purposes indicated in the respective agreements, the list of disqualified subjects sent by SFP.

As for administrative liability procedures, the following data are recorded:

Federal Taxpayer Registry Number or the Unique Identification Number of the person subject to the procedure.

The position occupied by the person subject to administrative procedure.

Where appropriate, indication of the type and origin of the appeal in question.

The type of sanction that has been imposed, specifying, where appropriate, the time limits and amounts of the sanction.

The date on which the sanction has been notified in the case of suspensions, dismissals or disqualifications, or the date on which it would have caused enforcement in the case of reprimands, economic sanctions and compensation liability.

The databases also provide information on disqualifications or on-going administrative liability proceedings of the public officials entering the state or municipal public administration of the State of Mexico. They can be accessed by entering:

Upon request of the human resources department or the heads of Internal Control Bodies of the entity where a person intends to work as a public official, certificates of non-disqualification containing the following information can also be generated:

Whether or not the person is subject to an administrative procedure.

For information purposes, the sanctions imposed by the federal authority or another federal entity.

Source: OECD based on materials provided by the State of Mexico.

Building on existing mechanisms and the current plan to revise its Comprehensive System of Responsibilities in view of its alignment with the National and State Digital Platform, SECOGEM could consider developing a case management system in close collaboration with SFP, whose “Comprehensive System of Administrative Responsibility” (Sistema Integral de Responsabilidades Administrativas ̧ or SIRA) shares information with the Comprehensive System of Citizens' Complaints and Report (Sistema Integral de Quejas y Denuncias Ciudadanas), the National Population Registry (Registro Nacional de Población) and the Single Registry of Public Officials (Registro Único de Servidores Públicos). Additional relevant practices that SECOGEM could take into consideration are Brazil CGU’s Disciplinary Proceedings Management and Estonia’s Court Information System, which provide examples of electronic case management tools in relation to disciplinary and civil enforcement, respectively (Box 5.6).

One of the pillars of CGU’s co-ordination function is the Disciplinary Proceedings Management System (Sistema de Gestão de Processos Disciplinares, CGU-PAD), a software allowing to store and make available, in a fast and secure way, the information about disciplinary procedures instituted within public entities.

With the information available in the CGU-PAD, public managers can monitor and control disciplinary processes, identify critical points, construct risk maps and establish guidelines for preventing and tackling corruption and other breaches of administrative nature.

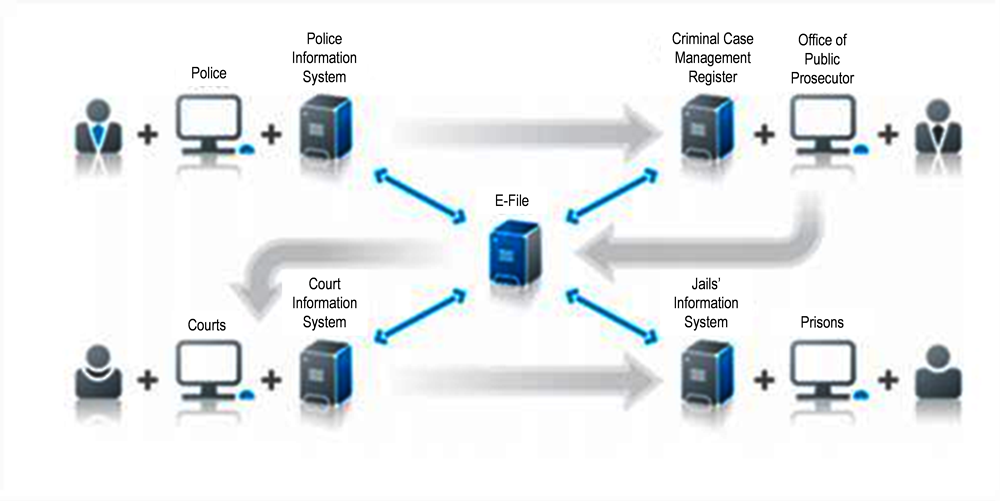

As for the Estonian Court Information System (KIS), when a court uploads a document to it, it is sent via a secure electronic layer for data exchange (the X-Road) to the e-File, a central database and case management system. The e-File allows procedural parties and their representatives to electronically submit procedural documents to courts and to observe progress of the proceedings related to them. The document uploaded to the e-File is then visible to the relevant addressees, who are notified via email. After the addressee accesses the public e-File and opens the uploaded document, it is considered as legally received. KIS then receives a notification that the document has been viewed by the addressee or his representative. If the document is not received in the public e-File during the concrete time-period, the court uses other methods of service.

Data related to disciplinary or administrative liability of public officials not only contribute to identify challenges and areas for further improvement of such accountability mechanisms but also to monitor and evaluate the broader integrity and anti-corruption system (see sub-section “Encouraging transparency about the effectiveness of the administrative liability system and the outcome of cases” in Chapter 5). Relevant information from the proposed electronic case management system could thus be connected with the State Digital Platform to promote identification of the administrative liability system shortcomings and to enhance the understanding of corrupt practices and risk areas. The State Digital Platform is envisaged by the Law on the Anti-corruption System of the State of Mexico and Municipalities to integrate diverse electronic databases - such as on asset, interest, and tax declarations; public officials involved in public procurement procedures; public officials and individuals sanctioned; public complaints of administrative misconduct and acts of corruption and; public contracts - into a specific portal. This platform will be managed by the State of Mexico Anti-corruption System and accessible by its members. While some of these databases are existing already (Box 5.5), information collected during the fact-finding mission evidenced partial progress in developing the Platform, although the State of Mexico is one of the most advanced among all Mexican States. Indeed, in 2019 two relevant databases were fully interconnected in the State and National Platforms (“public officials involved in public procurement procedures” and the public officials’ section of “public officials and private individuals sanctioned”) while in 2020 a 75% of interconnection was reached between two others (“asset evolution, declaration of interests and evidence of tax declaration’s submission" and the private entities’ section of the "public officials and private individuals sanctioned”.

Establishing a mechanism to enhance enforcement collaboration, such as an ‘enforcement working group’ within the State of Mexico’s Anti-corruption System, would promote co-ordination between criminal and administrative liability authorities

The disciplinary and administrative liability systems do not work in isolation from other enforcement mechanisms, in particular the criminal one. They are actually mutually relevant and supportive. Authorities under one of those enforcement regimes may become aware of facts or information that are relevant to another regime, and they should swiftly notify them to ensure potential responsibilities are identified. Indeed, cross-agency collaboration is particularly important during the investigative phase, where relevant information is often detected by agencies whose activity may be a source of both disciplinary and criminal liability. (Martini, 2014[5]). Indeed, a single act by a public official may be the source of both criminal and disciplinary or administrative liability that could then lead to civil law consequences, so all relevant institutions should count on each other’s collaboration in order to bring their proceedings forward following the respective procedures.

In the State of Mexico, the Law of Administrative Responsibilities of the State of Mexico and Municipalities establishes the rules and procedures to sanction public officials’ administrative breaches in the performance of their functions, as well as those of private individuals involved in corruption cases. The Criminal Code of the State of Mexico – together with the Federal Criminal Code – establishes crimes and sanctions for corruption-related conducts (e.g. abuse of authority, illegal use of powers, extortion, intimidation, abusive exercise of functions, influence peddling, bribery, embezzlement, and illicit enrichment). In the event of two proceedings taking place in parallel in relation to the same conduct – one of criminal and one of disciplinary or administrative nature – these run in parallel, without affecting each other.

While criminal and disciplinary or administrative enforcement systems have different objectives and functions, additional mechanisms should be in place to strengthen enforcement collaboration and the exchange of relevant information that are mutually helpful to scrutinise all typologies of liability related to suspected violations of integrity breaches. For instance, establishing working groups, either ad-hoc or in the framework of broader mechanisms to ensure co-operation across the public integrity system as a whole, creates the conditions for standardised processes, timely and continuous communication, mutual learning, dialogue and discussions to address challenges and to propose operational or legal improvements (Box 5.7). Working groups can also operationalise bilateral or multilateral protocols or memoranda of understanding to clarify responsibilities or to introduce practical co-operation tools between relevant agencies. In the context of the State of Mexico, a key role could be played by the Co-ordination Committee of the State of Mexico’s Anti-corruption System, which can recommend mechanisms for effective co-ordination allowing for the exchange of information among administrative and investigative authorities (Article 93 of the LRAEM). In particular, it could create a working group with relevant institutions such as SECOGEM, the State Supreme Audit Institution, the Administrative Justice Tribunal of the State of Mexico and the Public Prosecutor Office of the State of Mexico to discuss and agree on concrete tools to improve exchange of relevant information and effective communication. Considering the potential sensitivity of corruption cases and the need to ensure the independence of law enforcement activity, any co-ordination mechanism between criminal investigators and other government agencies should give due consideration to the constitutional role, competence and confidentiality limits of each institution involved.

Inter-agency agreements, memoranda of understanding, joint instructions or networks of co-operation and interaction are common mechanisms to promote co-operation with and between law enforcement authorities. Examples of this include various forms of agreements between: the prosecutors or the national anti-corruption authority and different ministries; the financial intelligence unit and other stakeholders working to combat money-laundering; or between the different law enforcement agencies themselves. These typologies of agreements are aimed at sharing intelligence on the fight against crime and corruption or carrying out other forms of collaboration.

In some cases, countries have launched formal inter-agency implementation committees or information-exchange systems (sometimes called “anti-corruption forum” or “integrity forum”) among various agencies; others hold regular co-ordination meetings.

In order to foster co-operation and inter-agency co-ordination, some countries have initiated staff secondment programmes among different entities in the executive and law enforcement agencies with an anti-corruption mandate, including the national financial intelligence unit. Similarly, other countries placed inspection personnel of the anti-corruption authority in each ministry and at the regional level.

Source: (UNODC, 2017[6]).

Dedicated co-operation efforts between SECOGEM, the State Administrative Tribunal and the Ministry of Finance are needed to identify and address challenges in the system for the recovery of economic sanctions

Consequences of serious breaches of the administrative liability framework in the State of Mexico include economic sanctions and compensations for damages caused to the public treasury or assets (Box 5.2). According to the LRAEM, these are determined by the Administrative Justice Tribunal of the State of Mexico and the payment is guaranteed through precautionary seizure of assets (embargo precautorio), which may be executed through the administrative procedure established by the State Financial Code (Código Financiero del Estado) to collect tax credits. In particular, the Ministry of Finance of the State of Mexico, which is the authority executing tax credits, may issue a precautionary embargo to ensure the reparation of the damage caused by public officials or private entities.

According to information in the Comprehensive Responsibilities System (Sistema Integral de Responsabilidades, SIR), from 1 January 2016 to 17 June 2019, the amount paid following economic and compensatory sanctions imposed is equivalent to 4.37%, of the total, which raised to 5.08% as of September 2020. The low amount of such activity reflects the presence of serious challenges in the sanction’s collection system and, according to interviews during the fact-finding mission, they do not seem to be fully addressed by the new regime established in the LRAEM.

Recovering economic and compensatory sanctions does not only contribute to restore the economic loss and damages to the public administration, but also promote credibility of the system and deter against future illicit conduct. In order to improve the current rate of collection, entities issuing sanctions, such as SECOGEM and the State Administrative Tribunal, could engage with the Ministry of Finance within the proposed working group on enforcement collaboration of the State Anti-corruption System’s Co-ordination Committee and create a Task Force to identify and propose measures to address the shortcomings of the system. In particular, such a Task Force should closely monitor the performance of the recovery system, identify risks and causes leading to the low rate of recovery and elaborate an action plan to address those weaknesses with concerted action, such as introducing procedural policies. One measure which could be considered by the Task Force and has been adopted by OECD countries is to increase the recovery rate by providing for direct deduction of sanctions from salaries and pensions. (OECD, 2017[7])

Selected data on administrative liability enforcement could be made available to the public in an interactive and user-friendly way and should be put at the disposal of the State Anti-corruption System

Generating, using and communicating data on disciplinary or administrative liability enforcement can support the integrity system in many ways. First, statistical data on sanctions issued following the breach of the integrity framework provides insights into key risk areas and sectors, which can thus inform more focused and tailored-made preventive interventions, policies, and strategies. Second, data can feed indicators and support the performance assessment of the disciplinary or administrative liability system as a whole. Third, data can inform institutional communications, giving account of enforcement action to other public officials and the public in general (OECD, 2018[8]). Lastly, consolidated, accessible and scientific analysis of statistical data on enforcement practices enables the assessment of the effectiveness of existing measures and the operational co-ordination among anti-corruption institutions. (UNODC, 2017[6]).

The data-collection activity on disciplinary or administrative liability enforcement should aim to have a clear understanding of issues such as the number of investigations, typologies of breaches and sanctions, length of proceedings, intervening institutions, in a manner that would facilitate analysis and comparability through time. Efforts in the State of Mexico seem to go in this direction since SECOGEM has put in place two registries that collect information on administrative liability proceedings and sanctions (Box 5.5). The Administrative Justice Tribunal of the State of Mexico also keeps statistics on breaches and sanctions, although this is not publicly accessible.

According to the information provided by the State of Mexico, statistical information on administrative liability enforcement is made public through SECOGEM’s SIR (www.secogem.gob.mx/sir/ConsultaSancionados.asp). The SIR portal is a search tool that allows to identify public servants sanctioned by making them ineligible for public service (inhabilitación). The user can search by name and last name or by accessing the full list of sanctioned officials. For each sanctioned official, SIR provides the following information:

Despite the usefulness of this information to identify “black-listed” officials, the SIR does not allow the user to aggregate information and generate data for decision making

On top of that, the website of the State of Mexico’s Transparency, Access to Public Information and Personal Data Protection (https://www.ipomex.org.mx/ipo/lgt/indice/secogem/sanciones.web) publishes the following information for each public official with a final administrative sanction:

archive of the resolution containing the approval of the sanction

hyperlink to the corresponding Registering System of Public Officials Sanctioned

While making administrative liability information public is a key step to make it a tool for accountability, the State of Mexico could further exploit its potential in two ways. First, it could make key parts of the considerable data and statistics collected transparent and accessible to the public in an interactive and user-friendly way, aiming to provide them in appropriate forms for its re-use and elaboration. In this context, the State of Mexico could consider the practice of Colombia, which elaborated corruption-related sanctions indicators (Observatorio de Transparencia y Anticorrupción, n.d.[9]) and Brazil, which periodically collects and publishes data on disciplinary sanctions (in pdf and xls format, which are not machine-readable formats) (CGU, n.d.[10]) Secondly, it could bring these data in the discussion and development of integrity and anti-corruption policies, for instance, by providing periodic reports to the State Anti-corruption System’s Co-ordination Committee with focus on areas, sectors and patterns emerging from on-going investigations and sanctions imposed. This could be a crucial input in the update of the State Anti-corruption Policy, as well as in monitoring and evaluation activities that will be undertaken. More generally, data on integrity enforcement can be part of the broader monitoring and evaluation of the integrity system. Korea, for example, develops and considers two indexes related to disciplinary and criminal corruption cases - the corrupt public official disciplinary index and the corruption case index – within the annual integrity assessment of public organisations. (Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission, n.d.[11])

The performance assessment mechanism of the administrative liability system could be complemented with additional indicators and its key results made publicly available

An additional use of enforcement data is to assess the effectiveness of enforcement mechanisms themselves, as well as to help identify challenges and areas for further improvement. For instance, they can in fact feed key performance indicators (KPIs) identifying bottlenecks and the most challenging areas throughout the procedures.

SECOGEM has various mechanisms in place to continuously measure the performance of the activities and functions of the areas in charge of administrative liability, which are:

Quality Management System: The administrative liability procedure is certified under ISO 9001:2015, which implies continuous improvement in the attention and processing of cases, always in line with the applicable regulations, the permanent training of personnel who carry out activities related to the matter, as well as the guarantee of due process, transparency and legal security.

Matrix Indicators: It is a planning tool that establishes the objectives of the General Directorates of Administrative Responsibilities and of Investigations, incorporating the indicators that measure their objectives and expected results, aligned to the fulfilment of the Development Plan of the State of Mexico 2017-2023.

With regards to the General Directorate of Administrative Responsibilities, they are:

percentage of public officials trained in compliance with the LRAEM

percentage of compliance in the presentation of the asset declaration by year, declaration of interests and presentation of the fiscal declaration

the report on compliance with these indicators is prepared on a monthly basis.

The Indicators for the General Directorate of Investigations are:

percentage of responses to complaints, suggestions and acknowledgements submitted

drafting of reports of alleged administrative responsibility.

Performance Evaluation: It is the structural and systematic procedure to measure, evaluate and improve the features, behaviours and results related to the activities of the personnel assigned to the General Directorate of Administrative Responsibilities, as well as the rate of absences, in order to calculate productivity, and to improve their future performance.

These tools developed by SECOGEM allow for a continuous and comprehensive assessment of the administrative liability system. However, they do not seem to consider key indicators on effectiveness, efficiency, quality and fairness developed by organisations, such as the Council of Europe, for the justice system (e.g. share of reported alleged offences taken forward, and average length of proceedings), (Council of Europe, 2018[12]) which could be also applied with respect to the State of Mexico’s administrative liability proceedings. SECOGEM could also consider making key results of its assessments publicly available to demonstrate a commitment to accountability and instil trust in its integrity enforcement system. Lastly, it could leverage performance assessment to promote improvements and legal changes of the administrative liability system within the State of Mexico’s Anti-corruption System, in view of addressing challenges and shortcomings emerging from its results.

Ensuring fairness, objectivity and timeliness

SECOGEM could adopt secondary regulation to implement some aspects of the LRAEM, such as the structure of the internal control bodies, that should all count with areas that investigate, conduct and take decisions in administrative liability cases.

SECOGEM could scale up existing training efforts for staff working in administrative liability offices – including at municipal level – focusing on the correct and uniform application of procedural rules and interpretation.

The review process of the Manual for case-building of administrative procedures could be accelerated and/or tools, manuals and channels to guide and support responsible entities in carrying out administrative liability proceedings could be developed, including on due process rights of the officials under investigation.

SECOGEM – together with the Administrative Justice Tribunal of the State of Mexico – could organise awareness-raising activities on administrative liability enforcement, targeting all public officials to support and legitimise the new legal framework.

Promoting co-operation and exchange of information among institutions and entities

SECOGEM could promote regular meetings with all the public entities’ administrative liability offices (OICs) and design an on-line platform to discuss common challenges, propose improvements and exchange good practices.

SECOGEM could develop a case management system building on existing mechanisms to register administrative liability proceedings. Relevant information from the electronic case management system could then be connected with the State Digital Platform.

The Co-ordination Committee of the State of Mexico Anti-corruption System could create a working group with relevant institutions, such as SECOGEM, the State Supreme Audit Institution, the Administrative Justice Tribunal of the State of Mexico and the Public Prosecutor Office of the State of Mexico to discuss and agree on concrete tools to improve exchange of relevant information and effective communication between administrative liability and criminal enforcement authorities.

SECOGEM and the State Administrative Tribunal could create a Task Force with the Ministry of Finance of the State of Mexico, as part of the proposed working group on enforcement collaboration, to closely monitor performance of the recovery system, identify the causes of the low rate of recovery and elaborate an action plan to address those weaknesses.

Encouraging transparency about the effectiveness of the administrative liability system and the outcomes of cases

SECOGEM could make key parts of the considerable data and statistics collected on the administrative liability system transparent and accessible to the public in an interactive and user-friendly way, but also in an appropriate format for its re-use and elaboration.

SECOGEM could bring administrative liability data in the discussion and development of integrity and anti-corruption policies, for instance, by providing periodic reports to the State Anti-corruption System’s Co-ordination Committee with a focus on risk areas, sectors and patterns emerging from on-going investigations and sanctions imposed.

The tools developed by SECOGEM to assess and monitor administrative liability enforcement could be complemented by introducing the measurement of key indicators on effectiveness, efficiency, quality and fairness developed for the justice sector, such as the share of reported alleged offences taken forward and the average length of proceedings.

SECOGEM could make key results of the administrative liability enforcement’s performance assessment publicly available to demonstrate a commitment to improving accountability mechanisms and instil trust in its enforcement system.

SECOGEM could leverage the results of the administrative liability enforcement’s performance assessment to promote improvements and legal changes to the administrative liability system in the State of Mexico Anti-corruption System.

References

[2] ACAS (2015), Code of Practice on disciplinary and grievance procedures, http://www.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=2174 (accessed on 27 November 2017).

[11] Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (n.d.), Assessing Integrity of Public Organizations, http://www.acrc.go.kr/en/board.do?command=searchDetail&method=searchList&menuId=0203160302.

[3] APSC (2015), Handling misconduct: A human resource manager’s guide, Australian Public Service Commission, http://www.apsc.gov.au/publications-and-media/current-publications/handling-misconduct-a-human-resource-managers-guide-2015 (accessed on 27 November 2017).

[4] CGU (n.d.), Manuais e Capacitação, https://corregedorias.gov.br/utilidades/conhecimentos-correcionais (accessed on 27 November 2017).

[10] CGU (n.d.), Relatórios de Punições Expulsivas, http://paineis.cgu.gov.br/corregedorias/index.htm (accessed on 30 July 2019).

[12] Council of Europe (2018), European judicial systems: Efficiency and quality of justice - Edition 2018 (2016 data), Council of Europe, https://rm.coe.int/rapport-avec-couv-18-09-2018-en/16808def9c (accessed on 30 July 2019).

[5] Martini (2014), “Investigating Corruption: Good Practices in Specialised Law Enforcement”, Anti-corruption Helpdesk, Transparency International, https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/assets/uploads/helpdesk/Investigating_corruption_good_practice_in_specialised_law_enforcement_2014.pdf.

[9] Observatorio de Transparencia y Anticorrupción (n.d.), Indicador de Sanciones Disciplinarias, http://www.anticorrupcion.gov.co/Paginas/indicador-sanciones-disciplinarias.aspx (accessed on 30 July 2019).

[8] OECD (2018), Integrity for Good Governance in Latin America and the Caribbean: From Commitments to Action, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201866-en.

[7] OECD (2017), OECD Integrity Review of Mexico: Taking a Stronger Stance Against Corruption, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264273207-en.

[1] OECD (2017), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/Recommendation-Public-Integrity.pdf.

[6] UNODC (2017), State of Implementation of the United Nations Convention against Corruption Criminalization, Law Enforcement and International Cooperation, United Nations, Vienna, http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/corruption/tools_and_publications/state_of_uncac_implementation.html (accessed on 27 May 2020).

Notes

← 1. While the focus of the chapter is the State of Mexico’s administrative liability system for public officials, reference is often made to disciplinary liability, which is a similar accountability mechanism used by OECD countries to sanction integrity breaches of public officials based on the employment relationship with the public administration and the specific obligations and duties owed to it. Breaching disciplinary obligations and duties commonly leads to sanctions of an administrative nature, such as warnings or reprimands, suspensions, fines or dismissals.

← 2. According to the information provided by SECOGEM, as of October 2020, administrative proceedings have been initiated against 568 public servants. For those cases, 7 public defenders have been requested, while the rest of public officials had their own lawyers or have decided to defend themselves.