Chapter 26. Viet Nam

Support to agriculture

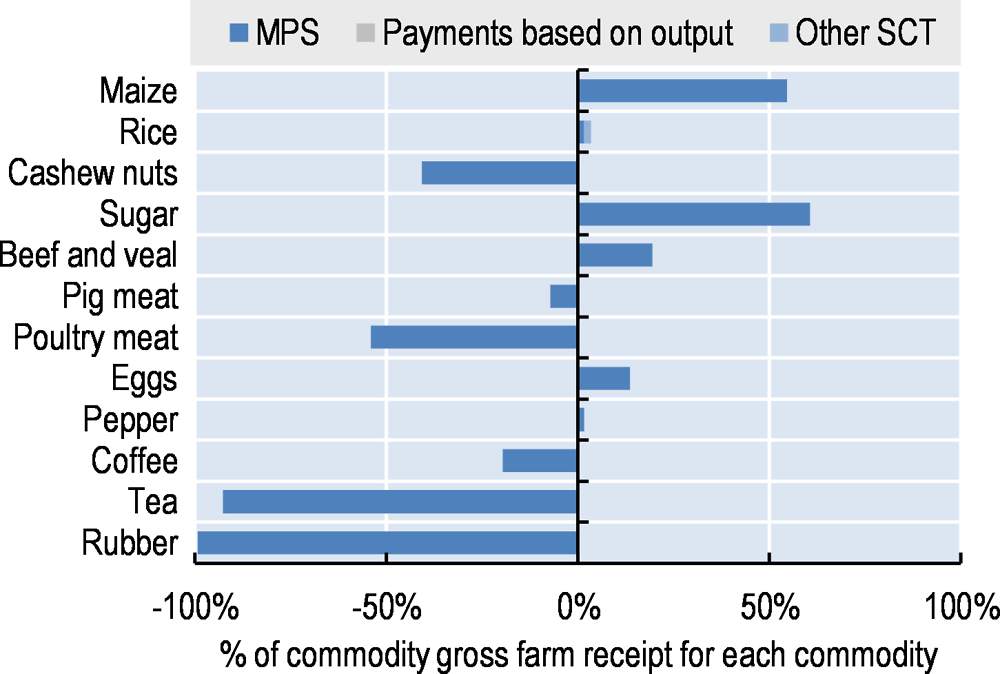

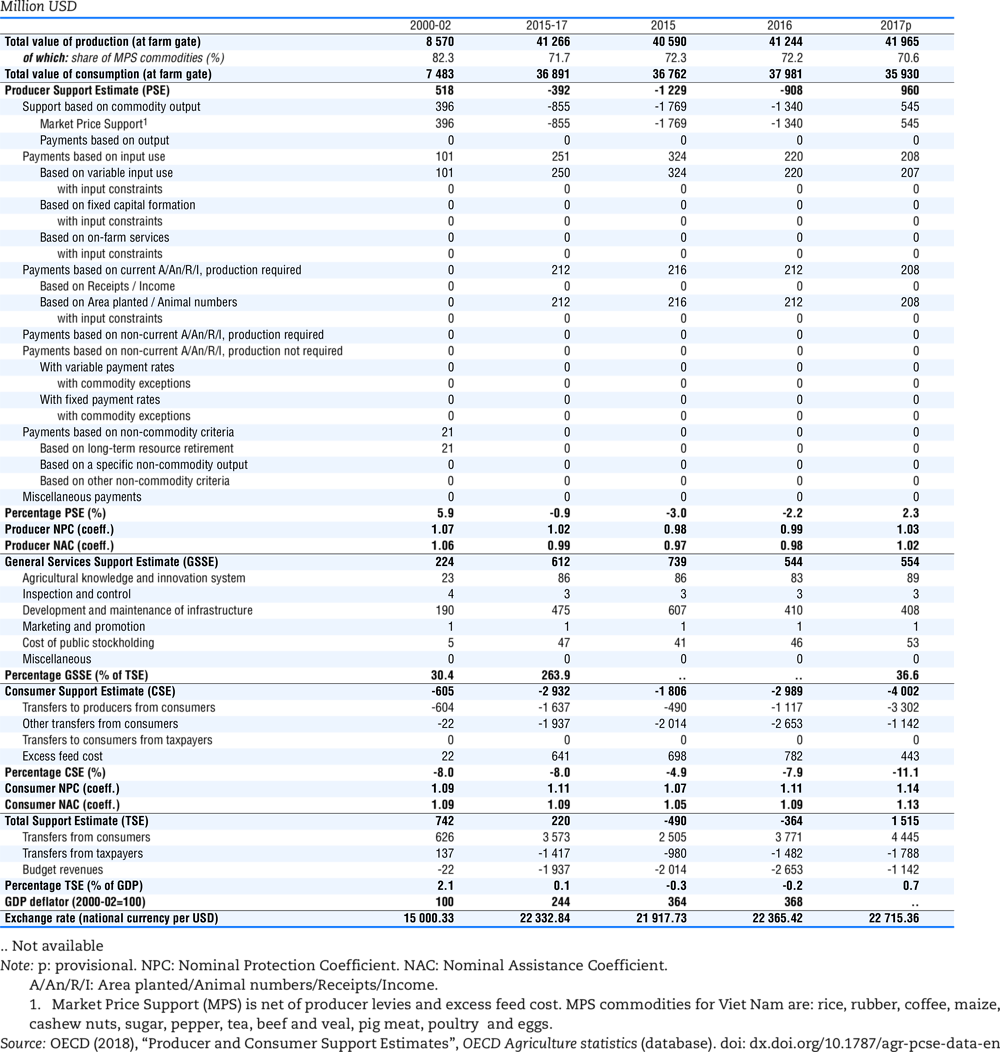

The level of support provided to Viet Nam’s agriculture sector fluctuates at very low levels, largely driven by changes in market price support (MPS). Producer support as a share of receipts varies across commodities. While producers of import-competing commodities, such as maize, sugar cane and beef, benefit from tariff protection, producers of several exported commodities are implicitly taxed. This results in a negative overall producer support estimate (PSE) in some years. Budgetary transfers are relatively small and include payments based on variable input use, primarily expenditure to subsidise an irrigation fee exemption, and direct payments to rice producers that are tied to maintaining land in rice production. Rice producers also benefit from a price support system based on target prices designed to provide farmers with a profit of 30% above production cost. In some years this price support system results in implicit taxation of rice producers when domestic prices are below international levels.

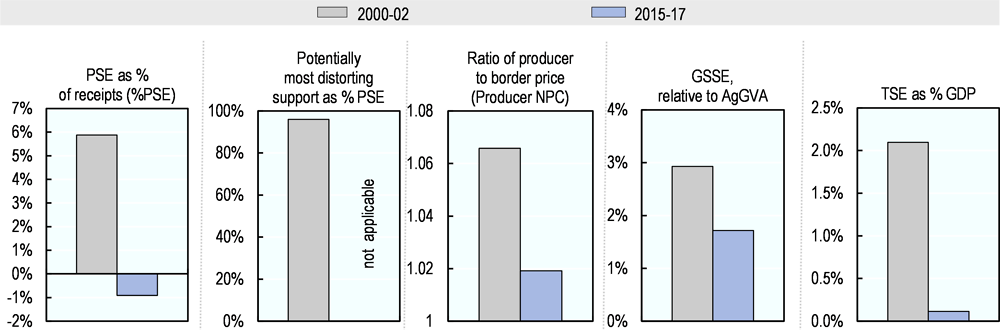

In 2015-17, Viet Nam’s producer support estimate (PSE) was slightly negative at –0.9%, despite a return to positive support in 2017. Support for general services for the agricultural sector is dominated by expenditure on the development and maintenance of infrastructure, in particular irrigation. Total support to agriculture (TSE) varies between positive and negative values, as in some years budgetary transfers to producers and expenditure on general services do not compensate for negative MPS. In 2017, the TSE was positive at 0.7% of GDP.

Main policy changes

In 2018, Viet Nam will introduce a fee for irrigation services under a new Law on Irrigation. According to the new law, irrigation service fees should include management costs, operation and maintenance expenses, depreciation charges, and other reasonable actual costs, and allow for profits matching those of the market. Decrees and circulars are currently under development that will outline the rate and type of fees.

The Government introduced a number of incentives and policies to promote the development of high-tech agriculture. In particular, state-owned commercial banks were directed to allocate at least VND 100 trillion (USD 4.4 billion) to a lending programme for high-tech, clean agriculture that offers interest rates 0.5% to 1.5% lower than market interest rates.

In June 2017, the Prime Minister approved a rice export development strategy for 2017-2020, with a vision to 2030, which aims to develop new markets and asks the rice industry to reorganise production and focus on improving quality. Also in 2017, the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT) began drafting a new decree on rice export activities to replace Decree No. 109/2010/ND-CP on rice export business. The revision is expected to remove bottlenecks for rice traders, especially small-and medium-sized enterprises.

Assessment and recommendations

-

In the last two years, Viet Nam has implemented a number of reforms that will enable improvements in the competitiveness and sustainability of the agro-food sector. In particular, the easing of restrictions on rice exporters will help to improve the competitiveness and quality of rice exports. Introducing a fee for irrigation services will encourage greater water use efficiency.

-

However, domestic and international conditions should become more challenging going forward. Agriculture is affected by Viet Nam’s deeper integration into the global economy, for example, as tariffs within preferential trade agreements are reduced. Moreover, most of the easy sources of lifting production – expanding the agricultural land area and using higher rates of fertilisers – have been fully exploited, and negative environmental impacts are increasingly seen. While these conditions are challenges for Viet Nam, they also open opportunities to adopt new technologies, create incentives for larger farms and to focus attention on quality and higher value products.

-

To improve the allocation of scarce land resources, farm consolidation could be encouraged, including through various forms of co-operation between farmers, and restrictions on crop choice should be removed. Moreover, the scope of compulsory land conversions should be limited and compensations for such conversions should be based on open market land prices. To limit the scope of social conflicts and corruption in the land administration, participatory land use plans could be encouraged and direct transactions between land users without state involvement should be allowed.

-

To improve the competitiveness and quality of Viet Nam’s rice exports, additional reforms could be considered to further ease restrictions on rice exporters, in particular, deregulating the export floor price. The current system risks cutting-off potentially profitable rice exports and creates uncertainty in engaging in export transactions if the minimum export price is likely to be changed.

-

Water overuse is exacerbated by the low cost of water, and increases the agricultural sector’s vulnerability to drought. While introducing a fee for irrigation services is a positive step, a fee based on a per unit of water charge – rather than on area or crop type as previously applied – would encourage greater water use efficiency.

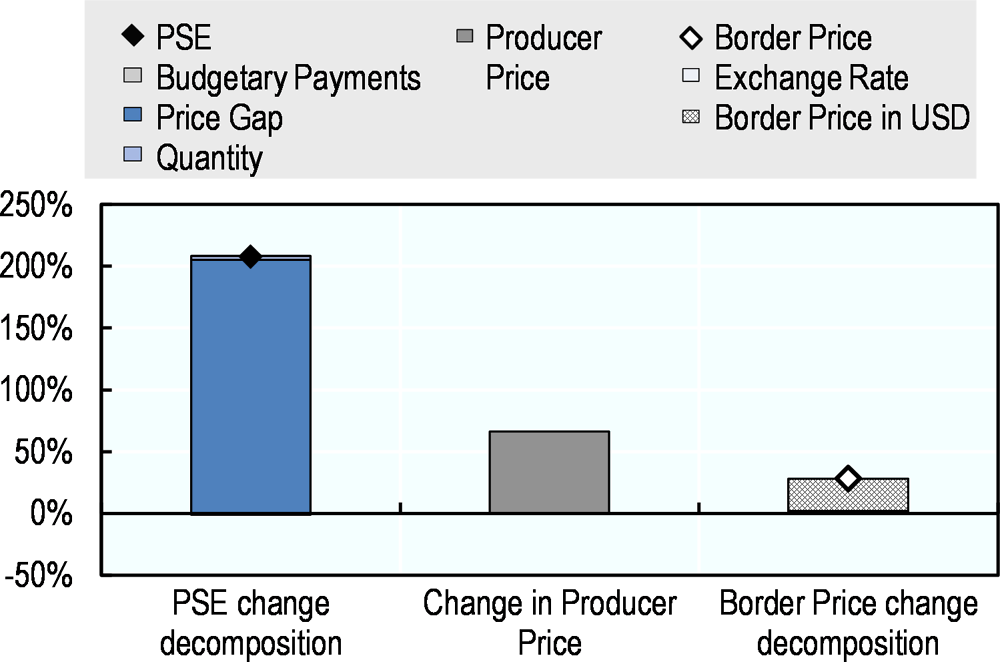

Support to farmers (%PSE) was -0.9% in 2015-17, implying an implicit overall taxation, compared to a relatively low, but positive level of support in 2000-02. Due to a negative market price support for the majority of commodities, the value of potentially most distorting support was also negative in 2015-17. Therefore, its share in total PSE is not shown (Figure 26.1). Expenditures for general services (GSSE), which focus largely on irrigation systems, were equivalent to 1.7% of agricultural value added in 2015-17, among the lowest across countries covered by this report, and down from 2.9% in 2000-02. Total support to agriculture as a share of GDP has declined significantly over time. The level of support increased significantly in 2017, as positive MPS for some commodities offset negative MPS for others. This increase in MPS resulted from a larger price gap, as domestic prices increased by more than world prices (Figure 26.2). On average during 2015-17, effective prices received by farmers (including output payments) were 2% higher than world prices, though this hides large differences between commodities. Transfers to single commodities vary widely, with maize, sugar, beef and veal, and eggs receiving positive MPS, while cashew nuts, pig and poultry meats, coffee, tea and rubber are implicitly taxed (Figure 26.3).

Contextual information

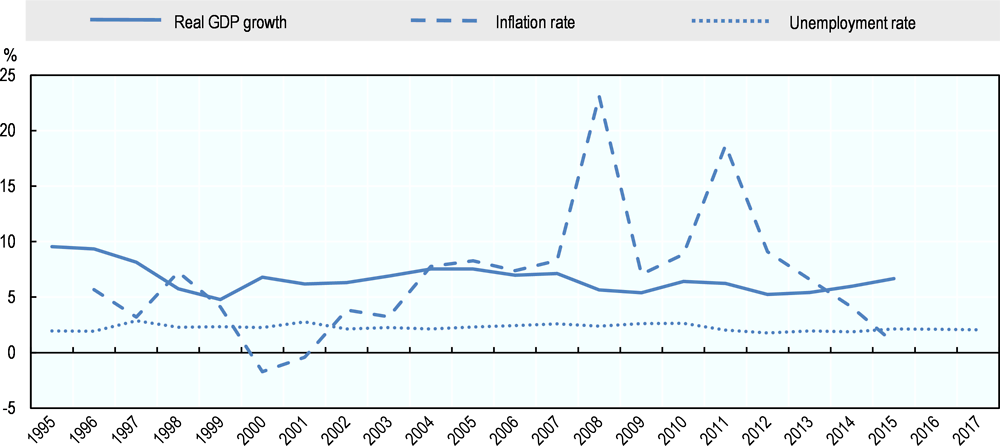

Viet Nam is a mid-size country in terms of area, but its population of 95 million makes it the 15th most populous country in the world. Around two-thirds of the population live in rural areas. Since the mid-1980s a long series of reforms have moved the economy, including the agricultural sector, in the direction of open markets for trade and investment. The economy boomed and agricultural production more than tripled in volume terms between 1990 and 2015. Strong economic growth lifted real incomes in both urban and rural areas, and poverty was alleviated as much as in any other country in the world, with the exception of China. The incidence of undernourishment fell from 46% in 1990-92 to 11% in 2014-16.

The agriculture sector in Viet Nam has undergone significant structural changes in recent decades, reflecting a shift away from staple foods to other commodities, in particular perennial crops such as coffee and rubber, and to livestock production, in particular pig meat. Nevertheless, crops dominate with rice accounting for around 35% of the value of agricultural production. While the relative importance of agriculture in the economy has declined over time, agriculture remains an important sector, contributing 18% to Viet Nam’s GDP and employing 44% of the labour force.

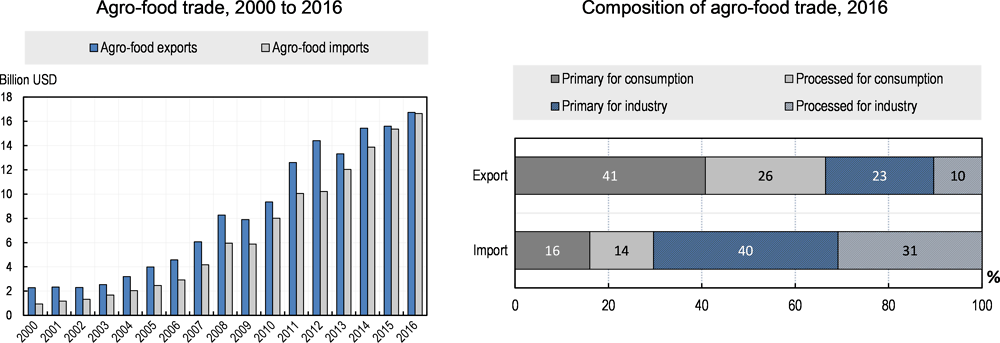

The agro-food sector is well integrated with international markets. Agro-food exports have increased eight-fold since the early 2000s, and Viet Nam is now one of the world’s largest exporters of a wide range of agricultural commodities, including cashews, black pepper, coffee, cassava and rice. Two-thirds of Viet Nam’s agro-food exports are delivered to foreign consumers and not used for further processing. Agro-food imports have also increased significantly. The majority of agro-food imports form intermediate inputs into Viet Nam’s processing sectors.

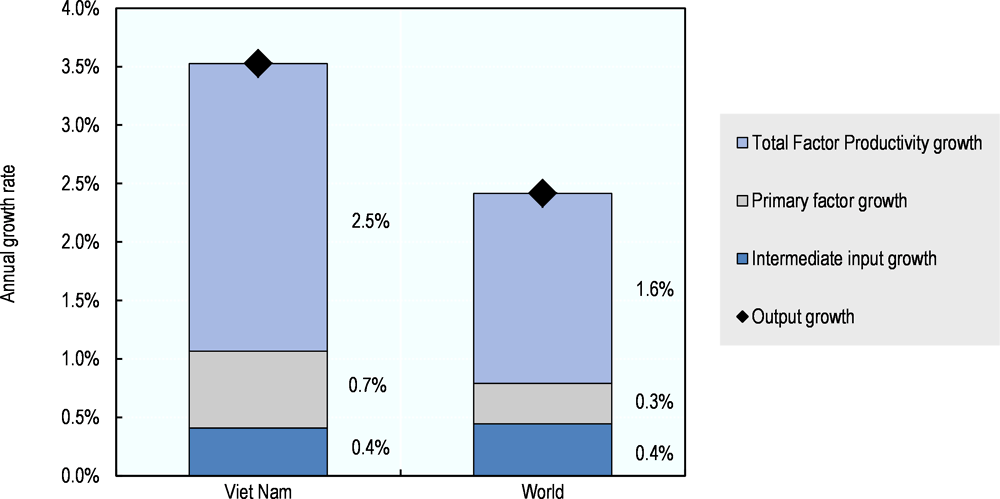

Agricultural production increased by 3.5% p.a. on average between 2005 and 2014, driven by total factor productivity growth of 2.5% p.a. and greater use of primary factors and intermediate inputs. However, agriculture exerts significant and growing pressure on natural resources. As a result of excessive use of fertilisers, pesticides and other chemicals, the sector has contributed to a gradual degradation of water and land quality. Together with climate change, this poses a significant risk to agricultural production and the capacity of the sector to maintain current, strong rates of productivity growth. The sector accounts for around a third of Viet Nam’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Description of policy developments

Main policy instruments

Market price support is the dominant form of support provided to Vietnamese producers with border protection being the main tool used to support prices. In particular, producers of import-competing commodities such as beef and veal, and sugar cane, are protected by tariffs. Farm gate rice prices are supported by a subsidy to rice purchasing enterprises for the temporary storage of rice during harvest and establishment of target prices which vary between regions and crop season with the objective of providing farmers with a profit of 30% above production cost. Producers of export-competing commodities such as natural rubber, coffee, cashew nuts and tea are implicitly taxed, in that they are paid prices for their outputs that are lower than world prices.

The simple average MFN applied tariff on agricultural imports decreased from around 25% in the mid-2000s to 16% in 2013. Applied tariffs are much lower on imports originating from countries or regions with which Viet Nam signed free trade agreements. For example, the average tariff is just 3.4% on agricultural imports from ASEAN members and 5.4% from China.

Until 2016, the government maintained a large degree of control over rice exports. Exporters had to meet specific milling and storage requirements, the minimum export price had to be respected, and certain administrative functions were given to the Viet Nam Food Association (VFA). However, in January 2017, in line with the Investment Law of 2014, Viet Nam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT) abolished Decision No. 6139/2013/QD-BCT, which had stipulated strict conditions for becoming a rice exporter.

Budgetary transfers to producers are relatively small. Expenditure associated with subsidising the irrigation fee exemption is the dominant payment. An area payment with the objective of keeping about 4 million ha in paddy rice production has been provided since 2012. In 2016, direct payments for rice growers were doubled to VND 1 million (USD 44)/ha/year for land under paddy cultivation, and increased fivefold to VND 500 000 (USD 22)/ha/year for other rice land, except upland fields not under paddy land-use plans. The decree also provides support for land reclamation for rice cultivation at VND 10 million (USD 440)/ha/year, except for upland fields, and VND 5 million (USD 220)/ha/year for wet paddy land reclaimed from one-crop paddy land or other crop land.

Other programmes that provide payments based on input use include programmes that provide plant genetic and animal breeding material to farmers at subsidised rates. At the national level, these are often provided as part of the package for farmers recovering from natural disasters or disease outbreaks. Since 2009, a number of policy packages have been introduced to provide farmers with subsidised credit to purchase machinery, facilities and materials. Since 2003, most farming households and organisations have been exempt from paying agricultural land use tax or benefited from tax reduction.

General services for the agricultural sector are dominated by expenditures on irrigation systems. Expenditures on some general services such as extension services, research and development, inspection and control and marketing and promotion are relatively limited.

All land is owned by the state and administered by it on behalf of the people. Farmers have land user rights, and benefit from a wide range of rights, including the right to rent, buy, sell and bequeath land and to use land as collateral with financial institutions for mortgages.

Since joining the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2007, Viet Nam has made some progress towards implementing the requirements of the Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement. However, the regulatory regime still suffers from limited enforcement capacity, poor co-ordination and a large number of overlapping documents.

Viet Nam implements trade liberalisation through multilateral, regional and bilateral trade agreements. It is a member of the WTO, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), and supports trade liberalisation between ASEAN members and their major trading partners in the region, including China, Japan, India, Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

Viet Nam ratified the Paris Agreement on Climate Change in 2016. Viet Nam’s Nationally-Determined Contribution (NDC) includes the commitment to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 8% between 2021 and 2030 compared to Business-as-Usual (BAU) levels using domestic resources, and up to 25% conditional on receiving international support. The Action Plan to Implement the Paris Agreement on Climate Change is outlined in Decision 2053/QD-TTg dated 28 October 2016, and includes activities for adaptation and mitigation in the agricultural sector.

Viet Nam’s 2011 National Strategy on Climate Change tasks the agricultural sector with reducing GHG emissions by 20% every ten years, while increasing gross production by 20% and reducing the poverty rate by 20% (Decision 2139/QD-TTg). MARD subsequently issued an action plan to adapt to climate change in the agricultural sector, most recently in Decision No. 819/QD-BNN-KHCN. The action plan prioritises research on, selection and production of plant varieties and animal breeds able to minimise GHG emissions and adapt to climate change; minimum tillage and techniques for reducing the use of water and fertilisers to minimise methane gas emissions in rice fields; the reduction of plants contributing to GHG emissions; and an increase in the production of bioenergy crops.

The commitment to reduce agricultural GHG emissions has also been affirmed in more recent decisions. In 2017, MARD issued Decision No. 932/QD-BNN-KH approving the Green Growth Action Plan of the agriculture and rural development sector for the period 2016-2020. This plan outlines 10 prioritised tasks and policy measures to reduce GHG by 20% in 2020, compared with the BAU scenario. Key activities include applying: organic farming; efficient use of agricultural inputs; short duration, high quality rice varieties; water saving practices (AWD); climate smart agriculture (CSA) practices; integrated crop management practices to reduce GHG emissions from rice and crop production; and enhancing animal feed mixing and animal waste (biogas) and crop residues management to reduce CH4 and other GHG emissions.

Domestic policy developments in 2017-18

On land use, in January 2017 the government issued Decree No. 01/2017/ND-CP, which amends the procedure that applies when land use is converted from rice to a perennial crop. Households require the permission of the People's Committee of the commune, which decides on the types of perennial crops that can be grown, in conformity with its plan for converting land use from rice to perennial crops. Land that is converted to a perennial crop must stay in a condition that allows rice to be grown in the future, e.g. irrigation systems for rice production cannot be damaged and soil cannot be degraded. In September 2017, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE) issued further guidelines on changes to land use. Circular No. 33/2017/TT-BTNMT adds cases in which a change of land use requires registration only (rather than permission from the relevant state agencies), including: conversion from land for planting annual crops into other types of agricultural land; conversion from other land for planting annual crops and land for aquaculture into land for planting perennial crops; and conversion from land for planting perennial crops into land for aquaculture or land for planting annual crops.

In June 2017, Viet Nam issued a new Law on Irrigation (Law No. 08/2017/QH14) that reintroduces a fee for irrigation services, including for irrigation products or services under the jurisdiction of the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development. According to this new Law, which comes into force on 1 July 2018, fees should cover management costs, operation and maintenance expenses, depreciation charges, and other reasonable actual costs, and allow for profits matching those of the market. Decrees and circulars are currently under development that will outline the rate and type of fees, although for agriculture this will likely vary according to crops grown and surface area (OECD, 2017). The Law also outlines the funding sources for small-scale and inter-field irrigation projects, which includes government support.

Also in January 2017, the Government issued Decree No. 02/2017/ND-CP on the support mechanism and policies for restoring agricultural production in areas suffering damage from natural disasters and epidemics. The Decree regulates support for plant varieties, livestock and aquaculture products, and support for part of the initial cost for restoring agricultural production lost due to natural disasters and epidemics, where the level of support depends on the extent of damage and on the commodity.

In March 2017, the Government issued Resolution No. 30/2017/NQ-CP, which includes a number of incentives and policies to promote the development of high-tech agriculture. On credit policy, state-owned commercial banks were directed to allocate at least VND 100 trillion (USD 4.4 billion) to a lending programme for high-tech, clean agriculture that offers interest rates 0.5% to 1.5% lower than market interest rates. On land policy, the Government assigned MONRE to coordinate with MARD and the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) to review and propose amendments to land policies in order to create favourable conditions for land consolidation and accumulation for large-scale agricultural production.

The Government continued to implement its two rural development programmes for the period 2016-2020. Under the National Target Program for New Rural Construction (Decision No. 1600/QD-TTg), the State provides partial support for infrastructure investments, including roads leading to commune centres, intra-field irrigation systems, investments to improve the rural environment, markets and rural commercial infrastructure, and to support the development of co-operatives. The maximum support available for communes in poor districts, listed under the National Target Program for Rapid and Sustainable Poverty Reduction, will be 100%.

Viet Nam continued to implement Decision No. 1956/QD-TTg approving the scheme on vocational training for rural workers labourers up to 2020. The budget for vocational training over the period 2016-2020 is VND 12 723 billion. This scheme also supports 100% of the cost to communes of implementing some measures for the National Target Program for New Rural Construction (above).

In 2017, Viet Nam launched the National Adaptation Plan in Agriculture (NAP-Ag). As part of the NAP-Ag, a climate change vulnerability assessment was carried out in the agricultural sector (crop, livestock and aquaculture production) together with a stocktake of climate change adaptation measures and CSA practices in use in the sector. A salinity monitoring and early warning system was also piloted in some provinces of the Mekong River Delta to keep farmers informed about salinity levels. Moreover, a pilot mapping of land slide disaster risk was carried out in 13 mountainous provinces of Viet Nam, to be scaled-out to the whole country in 2018.

Viet Nam is developing a unified climate change adaptation policy framework as part of the NAP-Ag to guide the identification, prioritisation and scaling-out of an enabling policy environment for NAP-Ag, in line with the tasks assigned to MARD in the Prime Minister’s Decision No. 2053/QD-TTg.

Trade policy developments in 2017-18

Viet Nam and ten other countries reached agreement on the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP was signed in March 2018 but remains to be ratified before entering into force. Negotiations on the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA) concluded on 2 December 2015. EVFTA is expected to be signed in 2018 and take effect from 2019.

In June 2017, the Prime Minister approved a rice export development strategy for 2017-2020, with a vision to 2030. The strategy lays out an annual export target of 4.5-5.0 million tonnes of rice for the period 2017 to 2020, valued at USD 2.2-2.3 billion. Between 2021 and 2030, Viet Nam will increase the annual value of rice exports to USD 2.5 billion while gradually reducing volumes shipped to 4 million tonnes a year by focusing on high value rice. The strategy also aims to reduce the share of Asian shipments in overall exports to 50% by 2030, while raising its market share in all other regions, especially the Americas, Africa and the Near East (FAO, 2018). The strategy asks the rice industry to reorganise production and focus on improving quality, to improve export competitiveness (News VietNamNet, 2018).

In 2017, Viet Nam’s Government, Ministries and localities increased support for trade promotion in agriculture, to help farmers and enterprises find new export markets. The National Trade Promotion Programme (Decision No 137/QD-BCT) provides support for enterprises and co-operatives to participate in domestic and international trade fairs. Under this programme, the State supports 50% of the cost of a stand for enterprises that register for this programme, to a maximum of VND 10 million/enterprise.

In March 2017, Viet Nam renewed a bilateral agreement with Cambodia under which 300 000 tonnes of paddy or husked rice may be imported annually duty free, effective until 31 December 2017.

References

FAO (2018), FAO policy developments website: http://www.fao.org/economic/est/est-commodities/commodity-policy-archive/en/ (accessed 20 March 2018).

Government of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (2016), Intended Nationally Determined Contribution of Viet Nam, Submission to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change by the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Hanoi, Viet Nam.

News VietNamNet (2018), “Vietnamese rice earns high export in 2017”, 8 January 2018, http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/business/193509/vietnamese-rice-earns-high-export-in-2017.html (accessed 21 March 2018).

OECD (2017), “Policy approaches to droughts, floods and typhoons in Southeast Asia”, TAD/CA/APM/WP(2017)17/FINAL.