Chapter 2. Bankruptcy and second chance for SMEs (Dimension 2) in the Western Balkans and Turkey

This chapter assesses policies in the Western Balkans and Turkey that support efficient bankruptcy legislation for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and promote a second chance for failed entrepreneurs. It starts by providing an overview of the assessment framework and progress since the last assessment in 2016. It then analyses the three sub-dimensions of Dimension 2: 1) preventive measures, which assesses tools and policies to help SMEs avoid bankruptcy; 2) survival and bankruptcqy procedures, which investigates the economies’ insolvency regimes for SMEs; and 3) promoting second chance, which examines policies to help failed entrepreneurs make a fresh start in business. Each sub-dimension section makes specific recommendations for increasing the capacity and efficiency of the bankruptcy and second chance in the Western Balkans and Turkey.

Key findings

-

Mechanisms to prevent bankruptcy are still underdeveloped across the region. The assessed economies lack institutional support and mechanisms to prevent entrepreneurs going bankrupt, such as early warning systems.

-

All economies have functioning insolvency laws that govern formal procedures for financially distressed companies. Yet few of them have succeeded in reducing the time taken to resolve insolvency to below the OECD average, and the recovery rates in the region are still very low.

-

Most of the economies have a formal bankruptcy discharge procedure in their legal framework; however, almost none of the governments set a legal time limit for entrepreneurs to obtain a discharge.

-

There is a lack of publicly available bankruptcy registers; this prevents enterprises from obtaining detailed information about potential business partners – undermining the transparency and legal certainty of business activities.

-

Second chance policies for failed entrepreneurs are still absent in the region. Region-wide, no public institutions are leading efforts to reduce the cultural stigma attached to business failure.

-

The Western Balkans and Turkey (WBT) governments provide no dedicated training or information on restarting a business after failure, hampering the economic reintegration of honest bankrupt entrepreneurs.1 However, none of the economies impose civic consequences on bankrupt business owners.

Comparison with the 2016 assessment scores

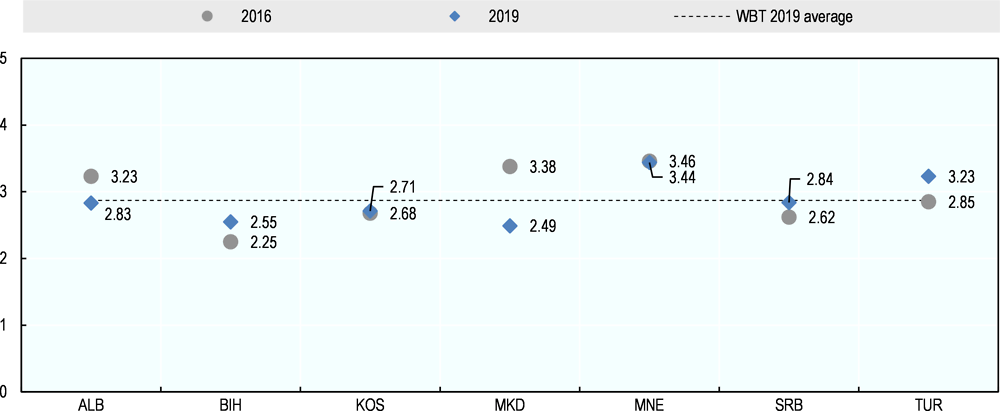

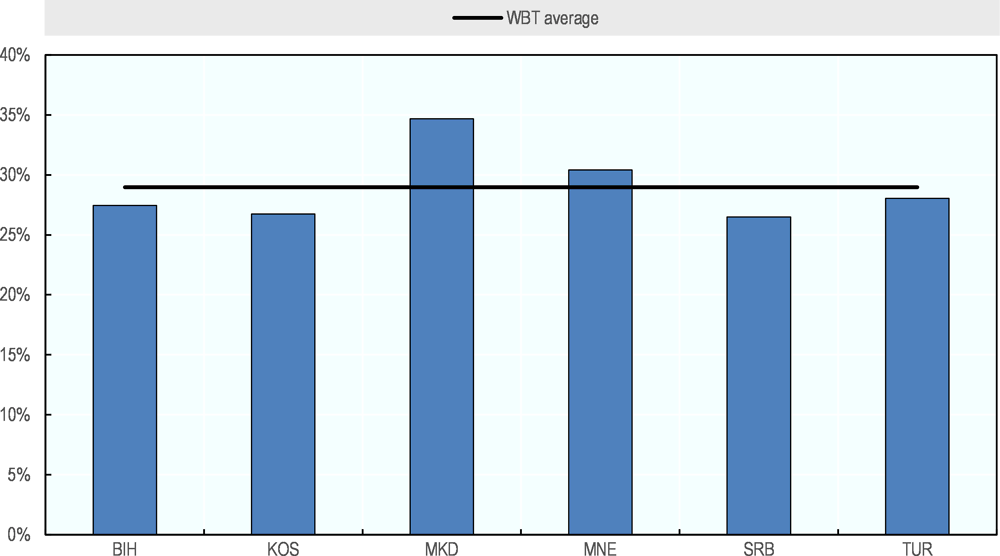

The performance of the WBT region in bankruptcy and second chance policies has shown limited progress since the last assessment. The region’s average score stands at 2.87, close to the score of 2.92 achieved in 2016 (Figure 2.1).

Nevertheless, the progress achieved by some of the economies is more pronounced than the regional average suggests. Compared with the previous assessment, Turkey has made the most significant improvement, with its newly introduced out-of-court settlements. Montenegro continues to be the regional leader as a result of its efforts to bring its bankruptcy regulation closer to international standards.

Implementation of the SME Policy Index 2016 recommendations

Implementation of the SME Policy Index 2016 recommendations on bankruptcy and second chance policies is rather limited across the Western Balkans and Turkey. While a number of changes have been implemented in legal frameworks, there have been no concrete steps to establish bankruptcy prevention mechanisms or to promote second chances for entrepreneurs (Table 2.1).

Introduction

Building a business environment conducive to growth and economic viability has long been at the forefront of policy makers’ agendas. However, the vital roles of efficient bankruptcy legislation and a culture that accepts entrepreneurial failure have been less recognised in the process of creating this enabling environment.

Generally, corporate bankruptcy has a positive impact on the economy. It allows the market to remove inefficient businesses and reallocate capital to efficient ones. It also provides a way for borrowers to get out of debt, paving the way for the possibility of re-engaging in economic activities. However, when businesses enter bankruptcy in large numbers – as they did during the financial crises – it can have a significantly negative impact on the economy and further contribute to economic depression and recession.

Companies entering and exiting the market are inherent to the business life cycle, and policies should ensure that this can occur in a smooth and organised manner (Cirmizi, Klapper and Uttamchand, 2011[1]). Efficient insolvency regimes protect both entrepreneurs2 and creditors, striking the right balance between the interests of each; protecting and ensuring support to all parties is imperative for efficient bankruptcy rules and procedures (World Bank, 2017[2]). Efficient regulations for bankruptcy recognise the complexity of the phenomenon and envisage the possibility of viable companies reorganising.

Business success or failure might be explained by internal or external circumstances. Internal causes can include managerial incompetence, overconfidence or excessive risk taking (Hayward, Shepherd and Griffin, 2006[3]). External factors can be related to inadequate economic circumstances, government policies or lack of financial resources (Liao, Welsch and Moutray, 2008[4]; Cardon, 2010[5]). However, regardless of the cause, effective liquidation and discharge procedures need to be in place to allow entrepreneurs to reintegrate into the market. Data show that entrepreneurs who go bankrupt have a higher success rate in their second attempt and, on average, their firms perform better than newcomers in terms of turnover and jobs created (Stam et al., 2008[6]). Currently, this possibility is often impeded by the stigma attached to a firm’s failure.

Appropriate measures and legal provisions should promote a positive attitude towards giving entrepreneurs a fresh start; aim to complete all legal procedures to wind up the business, in case of non-fraudulent bankruptcy, within a year; and ensure that restarters have the same opportunities in the market as they had the first time. In this context, effective bankruptcy regulations are crucial to ensuring a positive impact not only on companies’ market exit, but also on reducing the opportunity cost of entrepreneurship by creating more welcoming conditions for business creation.

Nevertheless, measures preventing bankruptcy and promoting second chances should be carefully considered, as they carry a certain level of economic risk. On the one hand, there are concerns about the survival of firms that would typically exit a competitive market, also called “zombie firms”. These might weigh negatively on average productivity and potential growth opportunities for more productive firms, by slowing the reallocation of scarce sources to the most productive use (Adalet McGowan, Andrews and Millot, 2017[7]). On the other hand, an excessive number of entrepreneurs restarting allows “serial entrepreneurs” who have not necessarily learnt from their mistakes to reintegrate into the market (Ucbasaran, Westhead and Wright, 2011[8]). This might also have a negative impact on the reallocation of resources.

Assessment framework

Structure

This chapter focuses on bankruptcy and second chance policies for SMEs. The assessment framework is divided into three sub-dimensions:

-

Sub-dimension 2.1: Preventive measures analyses the tools and policies that the economies use to help SMEs avoid bankruptcy.

-

Sub-dimension 2.2: Survival and bankruptcy procedures focuses on legislation and practice. It looks at whether survival procedures exist and how they operate; out-of-court pre-bankruptcy procedures; and laws and procedures for distressed companies, receivership and bankruptcy. It assesses policy performance, first in design and implementation and then in performance, monitoring and evaluation.

-

Sub-dimension 2.3: Promoting second chance examines how the economies facilitate a second chance for failed entrepreneurs, assessing their attitude towards giving entrepreneurs a fresh start and restrictions imposed on them during the period of bankruptcy.

The assessment was carried out by collecting qualitative data using questionnaires filled out by governments, and statistical data from national statistical institutes. The quantitative indicators used in the assessment include the recovery rate of distressed companies after the prevention phase, the average time to obtain full discharge from bankruptcy (a court order releasing the failed business owner from certain debts) and the average period of time taken for a negative score, such as the credit score, to be removed after discharge.

The data collected through the questionnaire were complemented by interviews with SME owners and managers.3 These entrepreneurs were asked their opinion on the effectiveness of the institutional support provided to avoid financial distress or bankruptcy. The entrepreneurs gave their views on the functioning of the bankruptcy process and its fairness. Finally, they evaluated the effectiveness of second chance mechanisms and how well they are promoted.4

Figure 2.2 shows how the sub-dimensions and their constituent indictors make up the assessment framework for this dimension. For more information on the methodology see the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A.

Key methodological changes to the assessment framework

Since the 2016 assessment, several changes have been introduced to the assessment framework (Table 2.2). This dimension has been expanded in order to better capture new practices and changes in this policy area. A new sub-dimension (Sub-dimension 2.1, on preventive measures) has been introduced to distinguish between before and after bankruptcy procedures. This new sub-dimension assesses the preventive measures in place to support entrepreneurs who risk failure. The sub-dimension on survival and bankruptcy procedures has also been expanded. In its new form, this sub-dimension puts a stronger emphasis on out-of-court settlements and discharge procedures.

Other sources of information

Statistical data from the World Bank Group’s 2019 Doing Business report (World Bank, 2018[9]) were also used to assess the efficiency of bankruptcy regimes in the Western Balkans and Turkey. The report provided statistical indicators on insolvency such as time and cost (measured as a percentage of the estate) to resolve insolvency and recovery rate. The data presented in the report allowed the information on resolving insolvency to be compared across economies, as well as over time. In addition, to better capture entrepreneurs perceptions’ and behaviours in the WBT region, the assessment looked at the fear of failure rate measured by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitoring report (see Annex 2.A) and the actions taken by entrepreneurs to resolve an overdue payment based on the business opinion survey from the Balkan Barometer 2018 (RCC, 2017[10]) (GEM, 2018[11]).

Analysis

Performance in bankruptcy and second chance

Outcome indicators play a key role in examining the effects of policies, and they provide crucial information for policy makers to judge the effectiveness of existing policies and the need for new ones. Put differently, they help policy makers track whether policies are achieving the desired outcome. The outcome indicators chosen for this dimension are designed to assess the Western Balkan economies and Turkey’s performance in resolving insolvency (Figure 2.2). This analysis section starts by drawing on the indicators to describe this performance.

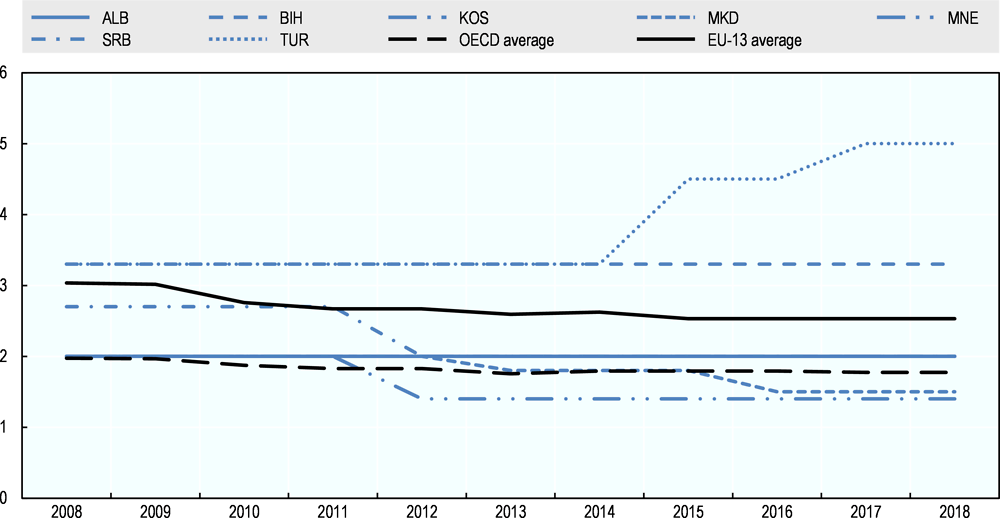

The region’s performance in resolving insolvency has, on average, not improved since the previous assessment. The Republic of North Macedonia is the only WBT economy where the time taken to resolve insolvency has fallen since the previous assessment (Figure 2.3). This improvement is directly linked to a reform in 2016, which introduced voting procedures for reorganisation plans into the legislation. This reform made procedures faster by allowing different groups of creditors to participate in insolvency procedures (World Bank, 2017[2]). In both Montenegro and North Macedonia, insolvency is resolved faster than the OECD average.

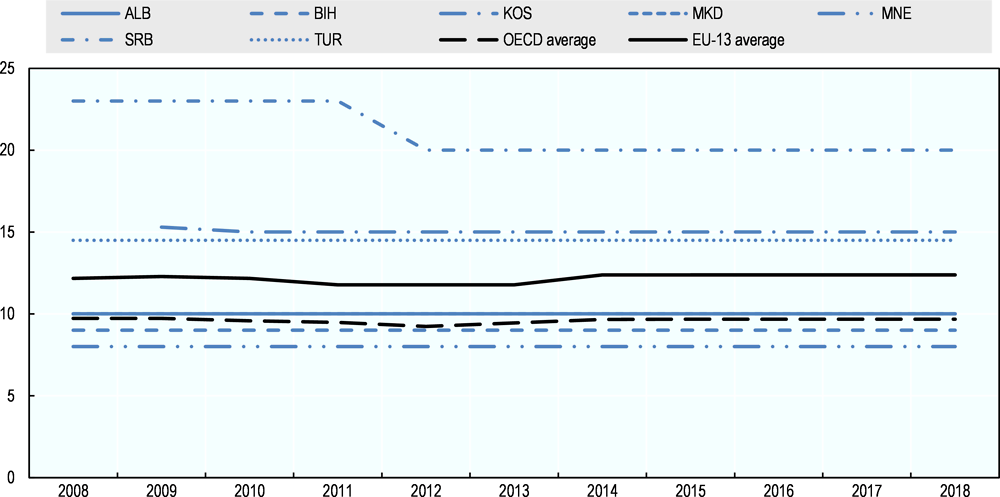

None of the economies in the region has managed to lower the cost of resolving insolvency since the last assessment (Figure 2.4). However, two economies – Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro – perform better than the OECD and EU-135 averages. Meanwhile, Serbia is the regional outlier, with a cost for resolving insolvency that is twice as high as the OECD average.

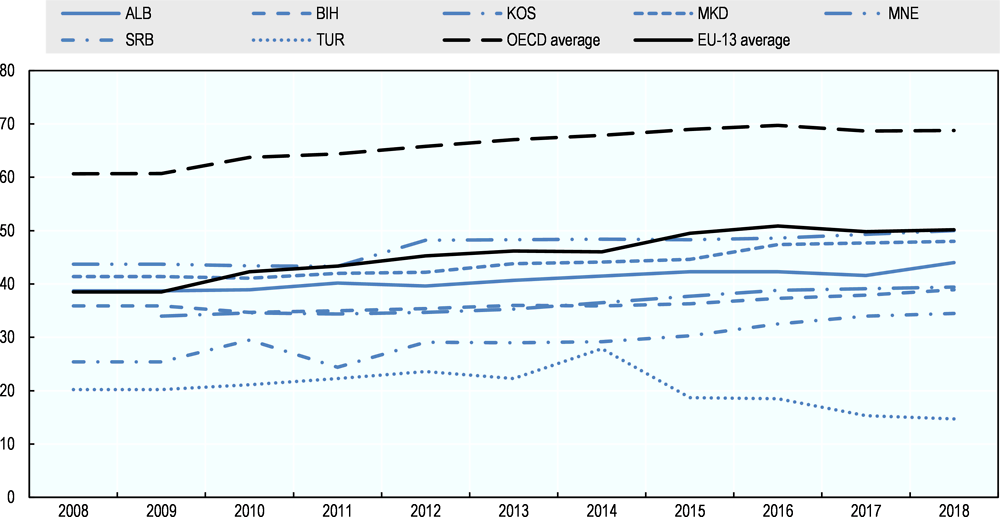

For the recovery rate6 of secured creditors, all the WBT economies perform below the OECD and EU-13 average (Figure 2.5). Since the previous assessment, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia have all increased their recovery rates. Serbia has seen the greatest increase, at 35.8% since 2016; however, it still has the second lowest rate in the region after Turkey. Moreover, Turkey is the only economy where the recovery rate has fallen (by 27.2%) since the last assessment. This change was due to the suspension of bankruptcy postponement applications, which resumed in March 2018 (World Bank, 2017[2]) and were replaced by concordat applications (see section on Survival and bankruptcy procedures (Sub-dimension 2.2) below).

Preventive measures (Sub-dimension 2.1)

The earlier a possible failing business is detected, the greater its chance of survival – this is the rationale behind preventive measures. If effectively applied, these measures can protect firms from entering bankruptcy, helping them to save on the cost of consultants specialising in insolvency and bankruptcy (EC, 2011[13]). Preventing bankruptcy is not only crucial from the perspective of enterprises and their owners, but it is also in the economies’ interests to save jobs and preserve economic value. Moreover, it helps economies to reduce the administrative burden on the judicial system and the economy overall.

Government intervention is crucial in providing active assistance to entrepreneurs who fear failure or are in financial difficulties. Therefore, initiatives such as diagnostic tools and information services are the backbone of a successful government strategy to prevent bankruptcy. Moreover, limited information on the existence of such initiatives has a negative impact – not only on failed entrepreneurs, but also on potential entrepreneurs who might be discouraged from starting a business, as well as on the job market in general (EC, 2011[13]).

This section gauges whether bankruptcy preventive measures and policy frameworks address the issues faced by entrepreneurs who encounter financial difficulties. It examines services (such as information campaigns, call centres, websites, self-tests or training) provided by governments to entrepreneurs who fear failure or are already in financial difficulties. It also assesses whether early warning systems exist to help initially identify financially distressed businesses, and then support entrepreneurs to reorganise their companies, if deemed viable.

Overall, preventive measures are still limited in the region (Table 2.3). While there are some initial signs of government activity, there is much room for improvement. North Macedonia scores the highest, followed closely by Montenegro and Turkey.

Mechanisms to help entrepreneurs overcome difficulties are underdeveloped

Business owners fearing failure or facing financial difficulties are not likely to ask for help, for three main reasons. First, they are afraid of losing control of their business. Second, they are concerned about the social stigma and the arduous process associated with bankruptcy. Finally, as entrepreneurs tend to be risk-prone individuals who are characterised by a high rate of optimism, they are often convinced that they will eventually be able to overcome the difficulties themselves (EC, 2011[13]). For this reason, information campaigns, training, call centres and anonymous self-assessment websites might be useful tools for entrepreneurs who fear failure and would like to have targeted information, learn or receive a discreet objective assessment of their situation.

These tools can also be helpful for potential entrepreneurs who would like to improve or assess their aptitude, skills and motivation to run their own business. As detailed in Annex 2.A, according to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, almost 30% of potential entrepreneurs fear failure across the WBT region (GEM, 2018[11]), hampering entrepreneurial activity.

Despite their potential positive impact, these tools remain undeveloped in the region, as was confirmed by interviews with SME representatives from the Western Balkans and Turkey. The only economy which currently has websites or call centres for entrepreneurs who fear failure is Turkey, where the SME Development and Support Organisation provides information on support programmes for SMEs.

North Macedonia has a project funded by the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance on strengthening the administrative capacities for implementing the legal framework for the bankruptcy and liquidation of companies (Ministry of Economy, 2017[14]). It proposes developing a self-test website, but this has not yet been established. The aim of the website would be to detect financially distressed companies early on, in order to help them in a timely manner. The project offers training for entrepreneurs who fear failure, organised in co-ordination with the Ministry of Economy, Economic Chambers, and the Chamber of Bankruptcy Administration. However, active entrepreneurs not in financial distress were reluctant to attend these courses, demonstrating that entrepreneurs do not seek help and advice before financial problems emerge.

Fully fledged early warning systems for distressed SMEs still do not exist

Company bankruptcy and liquidation can often be prevented if financially distressed companies are identified at an early stage. The earlier the problems are recognised, the better the chance the business will restructure successfully and continue to operate. Early warning systems identify enterprises that are financially distressed and in need of assistance. Among EU Member States, 14 countries have established early warning and help-desk mechanisms to prevent or coach entrepreneurs before going into bankruptcy (EC, 2017[15]); France has been one of the front runners in designing them (Box 2.1). Efficient early warning systems help regulate relations between companies and creditors, increasing SME owners’ awareness and helping them to identify and fix potential problems at the right time.

Such early warning infrastructure remains almost completely undeveloped in the WBT region. The current system adopted by the WBT economies only identifies distressed companies when they are already in the red zone, while ideally an early warning system should identify distressed companies in time to carry out a customised and solution-oriented reorganisation based on identified weaknesses. However, when firms are grappling with financial difficulties, it is sometimes central banks or tax administrations that take responsibility and react swiftly. In Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey, these public institutions have established initiatives that act as early stage warning systems, detecting warning signs through financial tools such as tax declarations or bank loans.

In some cases, the tax administration, banks or private credit registries assign a risk classification. For instance, regulations oblige Montenegro’s Central Bank to collect data from different banks on entrepreneurs whose accounts are blocked, and to publish them on their website. While this system allows financially distressed companies to be identified before they file for bankruptcy, it does not provide enough time or a solution for reorganising the firm and the debt to prevent bankruptcy. The regulations also oblige the Central Bank to publish data on forced collection procedures, specifically by revealing the names of legal entities/entrepreneurs, their registration numbers, blocked accounts, as well as the number of uninterrupted days the account has been blocked.

In Kosovo, the detection of distressed companies relies on assessments conducted by the tax administration, which are based on companies’ tax declarations. The system identifies financially distressed companies by analysing all businesses’ corporate tax returns.

In Albania, the Central Bank publishes data on entrepreneurs’ blocked accounts from different banks on its website, allowing financially distressed companies to be identified before they file for bankruptcy. In addition, some banks and private credit registries have developed their own mechanisms to assess customers’ credit performance, by drawing on information from multiple sources such as tax declarations, social security declarations and balance sheets. These mechanisms have been designed with a view to reducing the number of non-performing loans.

While the mechanisms described above identify companies which are already in financial distress and are therefore not proper early warning systems, they could constitute a base on which governments could build more effective prevention policies.

France is one of the few EU Member States and OECD countries that offers an early warning process to identify financially distressed companies. A 2005 amendment of the French Commercial Code1 provides a warning procedure (procedure d’alerte) to draw a manager’s attention to anything that might signal a threat to the company’s survival. This process has two main steps:

The warning procedure: the warning procedure can be triggered by the company’s external auditors, staff representatives or shareholders who own at least 5% of the capital. One of these stakeholders can warn the manager in writing about concrete identified problems. The manager must then respond within 15 days with a solution to address these difficulties. In the absence of a formal response from the manager (or if the answer confirms the difficulties or is considered insufficient), the account auditor and the commercial court or the district court is alerted.

Court involvement: if the warning has been triggered in a timely manner by the debtor, the commercial court will mandate a mentor to assist the entrepreneur to carry out a reorganisation without going to an in-court phase (mandat ad hoc). If the warning has not been triggered in time, the commercial court can follow up with:

-

A safeguard proceeding (if the debtor is solvent but meets difficulties that it is not able to overcome on its own). For a period of up to 6 months (which can be exceptionally extended to 18 months), a court-appointed receiver and a court-appointed agent will observe the company to evaluate whether recovery is possible, according to its organisation, economic performance, costs and external factors. At the end of the observation period, if the company is found to be viable the court will launch a reorganisation plan; if not, a liquidation procedure.

-

A reorganisation process (if the company cannot meet payment deadlines) aims to settle debts and, ideally, retain employees. For 6 to 18 months, the court will observe the company to evaluate its viability. At the end of the observation period, the court will make one of the following four decisions: 1) to totally or partially cease the enterprise’s activities; 2) to open a judicial liquidation, if the court considers that the company’s health cannot improve; 3) to end bankruptcy proceedings if it appears that the company actually has sufficient funds to meet its claims; or 4) to set out a recovery plan, detailing the steps that need to be taken to improve the company’s viability and retain the maximum number of employees.

-

Liquidation of the company (if the company is clearly unable, permanently, to meet its claims and a reorganisation is obviously impossible). Judicial liquidation signals the end of the company’s activities, but also stops any lawsuits filed against the company owner. A liquidator is appointed who will be responsible for selling the company’s assets.

← 1. Commercial Code Article L234-1 al 4, www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichCode.do?idSectionTA=LEGISCTA000006146054&cidTexte=LEGITEXT000005634379&dateTexte=20060608.

Sources: Service-Public-Pro (2018[16]), Alertes pour la prévention des difficultés des entreprises, www.service-public.fr/professionnels-entreprises/vosdroits/F22321; OECD (2017[17]), Observatoire consulaire des entreprises en difficultés, www.oced.cci-paris-idf.fr/; CCNC (2018[18]), La Prévention, www.cncc.fr/prevention.html.

The way forward for preventive measures

To enhance the insolvency regime and support enterprises in difficulties, policy makers should:

-

Step up efforts to mitigate fear of failure. One of the ways entrepreneurs can overcome their fear of failure is by gaining more knowledge. Learning can strongly contribute to easing entrepreneurs’ fears, by diminishing their doubts about their own personal abilities. Therefore, creating new mechanisms or linking existing ones to disseminate information – such as web-based tools or call centres – would help entrepreneurs find sources where they can easily access information and improve their entrepreneurial skill sets. Canada’s Business Development Bank self-test is a good example of how potential entrepreneurs can be helped to identify their weaknesses and be linked to adequate support programmes (Box 2.2).

The Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) is the only bank devoted exclusively to Canadian entrepreneurs. With its 123 business centres, BDC provides businesses in all industries with financing and advisory services. Its investment arm, BDC Capital, offers equity, venture capital and flexible growth and transition capital solutions.

To help entrepreneurs to start or grow their business, BDC offers more than 1 000 online articles, business templates, and other publications on issues connected to entrepreneurship and managing businesses. It also provides interactive tools such as e-learning modules, business assessments and financial calculators.

One of these interactive tools is the entrepreneurial potential self-assessment. Created in 2002 by a professor from Laval University, Quebec City, this tool uses a comparison model that draws on a dataset of 2 000 to 3 000 interviews with Canadian entrepreneurs.

The core of the self-assessment is a set of 50 statements on which entrepreneurs give their opinion. Answers to these statements measure motivation, aptitude and attitude. The results allow a comparison between the individual’s results and the mean of Canadian entrepreneurs’ scores. The questionnaire was completed almost 50 000 times in BDC’s last fiscal period (2017/18).

After completing the test, entrepreneurs receive customised advice about what content can help them improve their skills as business leaders in BDC’s Entrepreneur’s Learning Centre. Courses in the centre are grouped by categories, including business strategy and planning, money and finance, operations or entrepreneurial skills. The format of the courses also varies depending on the subject, from short videos and games to online classes.

Source: BDC (2018[19]), Business Development Bank, www.bdc.ca.

-

Develop a fully fledged early warning system in order to effectively protect companies from bankruptcy. SME owners have a tendency to underestimate their financial difficulties and resist taking action to alleviate them. Therefore, governments should consider introducing a system which would convince entrepreneurs to initiate recovery measures without delay. This system might take different forms, but should include certain essential features. First, it should include special detection procedures to screen and monitor early signs of SMEs in financial difficulties. Second, these identified SMEs need to be approached and provided with advice on objectively assessing their financial situation, as well as on the different options available to them to recover. Once they are better informed, SMEs would be able to take the required steps at an earlier stage, increasing their chances of survival. To that end, Early Warning Europe (Box 2.3) offers a blueprint of how economies can build a customised early warning system, advise entrepreneurs in financial distress and reintegrate them into the economy.

The international project Early Warning Europe (EWE) was developed with the objective of promoting SMEs’ growth across Europe by assisting them during financially difficult periods. In 2016, Early Warning Europe applied for funding through Europe’s Competitiveness of Enterprises and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (COSME) programme and obtained almost EUR 5 million. The first wave of the project ran for three years and focused on setting up a full-scale early warning mechanism in Poland, Italy, Greece and Spain.

The consortium is comprised of 15 partners in 7 countries including mentor partners Early Warning Denmark, TEAM U in Germany, Dyzo in Belgium, authority partners such as the Danish Business Authority, the regional government of Madrid and the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development, as well as EU-level associations such as the, European Small Business Alliance, Eurochambres and SMEunited. The Early Warning Europe project is financed by COSME and aims to provide assistance to businesses and entrepreneurs in trouble, as well as those who wish to better anticipate problems. The project builds new best practice and draws on existing experience from these 15 organisations. EWE is open to all COSME countries, and the expansion in phases gives access to the early warning mechanisms foreseen in the upcoming EU Directive on preventive restructuring frameworks, second chance and measures to increase the efficiency of restructuring, insolvency and discharge procedures.

The consortium is composed of three groups of organisations: 1) mentor organisations with substantial experience in providing support to companies in distress; 2) national or regional organisations that intend to implement early warning mechanisms; and 3) organisations that are responsible for supporting the pan-European communication and dissemination activities of the project.

Through EWE, entrepreneurs can receive help from consultants to get a clear overview of the company, identify the areas which are causing problems, and propose further remedial activities. The second step of the restoration process is collaboration with a mentor. Mentors work closely with the entrepreneur providing expertise, knowledge and support to get the enterprise back on the right track. Alternatively, they can guide companies toward a quick, organised closure when this is the best option for the company. This also contributes greatly to the company owner’s chances of a second start and reduces the loss for the owner, the creditors and society as a whole.

Independent evaluations show a highly positive impact on society of the Early Warning system in terms of jobs saved and savings for the public treasuries. Evaluations show a general saving of 20% for the public treasuries on company closures under the Early Warning mechanism, a high level of job preservation and significantly better first-year turnover and growth after the Early Warning intervention.

An innovative element of the project is the introduction of artificial intelligence and the processing of big data in detecting early signs of distress in companies. Early Warning Europe has developed a data model that identifies the probability of distress in companies in Poland, Italy, Greece and Spain based on publicly accessible data, allowing the network partners to proactively assist companies that may not otherwise realise their problems before it is too late.

Currently the project has the support of more than 500 mentors. The support provided is impartial, confidential and free-of-charge. In the first wave, EWE provided support to 3 500 companies in distress in Poland, Italy, Greece, and Spain. In its second wave (2017-19) the project will support the establishment of early warning mechanisms in five additional EU Member States, with the ultimate goal of establishing early warning mechanisms in all EU Member States.

Source: Early Warning Europe (2018[20]), Early Warning Europe website, www.earlywarningeurope.eu/.

Survival and bankruptcy procedures (Sub-dimension 2.2)

Survival and bankruptcy proceedings are crucial for SMEs to function. They do not only regulate the smooth market entry and exit of new firms, but they can also stimulate the region’s entrepreneurial spirit on a more general level. Transparent and well-defined legislation translates into efficient bankruptcy proceedings, creating less of a burden on the judiciary system, and leading to a higher number of reorganisations instead of filed bankruptcies.

This section focuses on measures for survival and bankruptcy procedures in the region, using two thematic blocks (Figure 2.2). First, under design and implementation, it investigates changes in the assessed economies’ regulations for insolvency regimes, as well as the existence of alternative ways for financially distressed SMEs to file for bankruptcy. Since legislative frameworks have a significant impact on these procedures, this section also examines the framework for creditor protection and business restructuring/reorganisation (initiated by debtors, creditors or bankruptcy administrators).

Second, under performance, monitoring and evaluation, the section reviews the monitoring and evaluation of bankruptcy proceedings, as well as limitations in the administrative capacities of WBT economies.

The WBT economies have achieved a solid legal framework for survival and bankruptcy procedure regulations (Table 2.4). The overall weighted average reflects governments’ efforts in improving legislative frameworks and the introduction of out-of-court settlements. Montenegro is the regional leader, followed by Turkey, Serbia and Albania. Higher scores in design and implementation than monitoring and evaluation suggest that there is still room for improvement in the WBT region.

Out-of-court settlements are available, but not automatically linked to formal bankruptcy proceedings

Out-of-court settlements can resolve disputes between debtors and creditors, or avoid company insolvency, reducing the burden on economies’ judicial systems. This offers a speedy, less expensive and less formal solution than court proceedings and avoids damaging the failed entrepreneur’s reputation. Economy-specific research has shown that insolvency reforms that encourage debt restructuring and reorganisation reduce both failure rates among SMEs and the liquidation of potentially profitable businesses (Hart, 2000[21]). According to the Balkan Barometer, in 2017 nearly one-seventh of entrepreneurs in the WBT region launched a court action to resolve an overdue payment issue (RCC, 2017[10]). One can imagine the burden on the judiciary systems of processing this number of cases.

Most WBT economies have introduced appropriate measures to provide honest entrepreneurs with alternative settlement procedures that allow them more time to restructure their businesses. However, none of them have a clear link which allows formal bankruptcy proceedings to be triggered automatically if the debtor and creditors cannot reach a full agreement.

In some of the assessed economies, out-of-court settlements are loosely regulated, as they are not prohibited. This is the case in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the Law on Bankruptcy Proceedings in the entity of the Republika Srpska does not prohibit out-of-court procedures.7 However, the law specifies that out-of-court settlements can take place if one of the creditors is a bank, and that they must be mediated by the chamber of commerce.

Montenegro has a similar approach to regulating out-of-court settlements. The legislation states that having accepted a petition to initiate bankruptcy procedures, the court might refer the petitioner to a mediation procedure. This approach can involve debtors, creditors, banks and the mediation centre in the whole process. This legislation seeks a compromise between the survival of financially distressed companies and macroeconomic stability.

The Serbian legal framework allows entrepreneurs to go into mediation as a pre-bankruptcy alternative to settle debts. However, bankruptcy proceedings need to be initiated first. Then, the creditors or the bankruptcy administration, with the consent of the creditors’ committee, may propose resolving a dispute through mediation, which cannot take more than 30 days.

Some of the economies opt for having a more strictly regulated approach to the out-of-court settlement alternatives. North Macedonia offers two schemes that provide protection from creditors. First, the distressed business is protected by the Law on Out-of-Court Settlement, which grants a preventive concordat period of 120 days, during which the debtor has the time to draft and negotiate a restructuring plan with creditors. This pre-bankruptcy measure can have one of three outcomes:

-

1. If all the creditors approve the debtor’s plan, it leads to an effective new debt settlement.

-

2. If creditors holding more than 51% of the total debt approve the debtor’s plan, it will allow for a fast-track in-court bankruptcy reorganisation.

-

3. If only those creditors holding less than 51% of the total debt approve the debtor’s plan, it leads straight to simple in-court bankruptcy liquidation.

Second, SMEs encountering financial difficulties in North Macedonia are also protected by the Law on Bankruptcy, which provides them with three more options for reorganisation: 1) debtor-initiated bankruptcy reorganisation via a short-track procedure of 60 days; 2) regular creditor-initiated in-court bankruptcy reorganisation; and 3) the bankruptcy administrator’s proposal for a reorganisation plan, with the consent of the creditors.

Albania’s regulations offer SMEs the option of a reorganisation plan which needs to be reviewed and voted on by the creditors’ board. Out-of-court procedures can start when this plan is approved by a court judgment. Importantly, SMEs are liquidated if their reorganisation proposals are rejected. Turkey has recently introduced the concordat regime, which gives the debtor a maximum of two years’ protection following the acceptance of the reorganisation plan by the creditors’ board and a final validation from the insolvency officer.

In Kosovo, the law states that the reorganisation process may take different forms, such as debt forgiveness, debt rescheduling, debt-equity conversions or the sale of the business or parts of it.

Insolvency regimes have been strengthened in most of the economies

Insolvency laws lay out the necessary legislative framework to give certainty over how insolvency proceedings are to be dealt with. They ensure that the liquidation of assets and distribution of the proceeds are done in a fair and orderly way among creditors. By doing so, they allow for better financial inclusion, and reduce the cost of obtaining credit (World Bank, 2018[22]). Moreover, insolvency laws offer legal protection to viable businesses by allowing them to negotiate arrangements with their creditors. Therefore, as the European Commission (EC) recommendation of March 20148 also stresses, having clear, simple and non-rigid insolvency laws are crucial for improving the business environment and supporting businesses’ long-term survival.

Since 2016, the WBT economies have made a number of amendments to their insolvency laws (Table 2.5). Kosovo has made significant changes to its insolvency regime. In 2016, the government simplified the process of insolvency by introducing a legal framework for corporate insolvency. It also allowed debtors and creditors to benefit from liquidation and reorganisation procedures (World Bank, 2017[2]). Another exemplary development occurred in North Macedonia, where the government has reformed the voting procedures for reorganisation plans and allowed more participation by creditors in insolvency proceedings (World Bank, 2017[2]).

Overall, the reforms have improved the economies’ legal frameworks to protect the interests of both debtors and creditors, as the Montenegrin case shows (Box 2.4).

Montenegro introduced the latest changes to its insolvency laws in 2016, even though the initial 2011 Insolvency Law already closely followed the provisions set out in the United Nations Commission on International Trade’s Legislative Guide on Insolvency Law (UNCITRAL, 2013[23]).

These amendments have harmonised the laws further with international standards, as well as with commercial law and practices, by promoting the reorganisation of businesses that are in financial difficulties and liquidating non-viable companies. The reorganisation procedure has the dual purpose of ensuring debtors’ financial recovery and settling creditors’ claims. The procedure includes a reorganisation plan that needs to be submitted to the judiciary body along with the petition to initiate insolvency proceedings. If sent after insolvency proceedings have begun, the reorganisation plan should be delivered within 90 days of the proceedings opening. The reorganisation plan may be submitted by:

-

the debtor

-

the receiver

-

creditors holding at least 30% of the aggregate amount of the secured claims

-

creditors holding at least 30% of the aggregate amount of the unsecured claims

-

persons owning at least 30% of the share capital of the debtor.

The legislation also contains detailed provisions for the more complex areas of insolvency law, such as the avoidance of transactions or insolvency set-off.

This legislation is an example of good practice as the Insolvency Law also applies to state-owned enterprises which do not receive funding from the budget. Overall, these changes not only bring Montenegro closer to EU regulations, but also make the insolvency regime more efficient. Shorter deadlines and clearer provisions for certain cases make the system more transparent and limit the possibility for different interpretations.

Source: Babić and Branović (2016[24]), Insolvency / Restructuring in Montenegro, www.schoenherr.eu/publications/publication-detail/insolvency-restructuring-in-montenegro-1/.

Legal frameworks on secured transactions are in place, but some lack time limits for automatic stay

While a clear legal framework on secured transactions9 is necessary to protect all parties involved in a transaction and to make transactions more efficient, the law should strike a balance between creditors’ rights and debtors’ interests when regulating the automatic stay10 on debt collection. While an automatic stay helps the debtor to recover and allows creditors to collect their claim during the reorganisation process, the EC recommends there should be a time limit (EC, 2014[25]).

Although all the assessed economies have established frameworks to support SMEs and creditors if a company becomes insolvent, the approaches in their regulatory frameworks differ and not all of them fix a time limit for automatic stays.

The legislation covers all aspects of secured transactions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Turkey. These economies regulate secured creditors’ ability to satisfy their secured claim in reorganisation, as well as their right to be paid first out of proceeds from the sale of assets on which they have lien11 or collateral. The bankruptcy legal framework for secured transactions in these economies also includes restrictions, such as the requirement for creditors’ consent to conduct the reorganisation of a debtor’s bankruptcy case opened in court, and the appointment of a bankruptcy administrator to replace the company management until the approval of a reorganisation plan. However, none of them has defined a time limit for the automatic stay during the process.

In Albania, the legal framework regulates restrictions such as the requirement for creditor’s consent when a borrower files for bankruptcy, or that secured creditors are to be paid first from the liquidation proceeds of a bankrupt firm – it provides a contractual stay of 90 days, binding only on the parties that have agreed to it. However, the regulations do not cover areas such as the seizure of collateral by the secured creditors (after reorganisation) nor on the management of administration of the property awaiting the resolution of the organisation.

In North Macedonia, the regulation specifies several aspects of dealing with secured transactions, but does not legislate on the stay. Secured creditors have the right of a separate settlement out of the bankruptcy proceedings. The judge grants this right if the asset is not subject to a reorganisation plan. With the secured creditors’ consent, the collateral on assets subject to reorganisation may be transferred on assets from the estate that are not vital to the debtor’s reorganisation. In any event the secured creditors have a right to be paid first from the sale proceeds of the assets over which they have secured right (collateral). The bankrupt debtor’s reorganisation plan must be approved by vote by a majority of the creditors.

Monitoring and evaluation of bankruptcy proceedings remain weak in the region

It is crucial for economies to have a well-developed set of performance indicators to better monitor the efficiency of insolvency regimes. The OECD has developed insolvency indicators (see Box 2.5 and also Annex 2.B) to obtain policy indicators that evaluate the differences between countries, to facilitate further research on exit policies and productivity growth.

Despite some examples of positive changes, the monitoring and evaluation of bankruptcy and insolvency procedures are still very weak in the assessed economies. Most of the WBT economies do not collect basic indicators, such as the average time it takes to receive a full discharge from bankruptcy, the number of backlogged court cases related to bankruptcy or the number of years a bankrupt entrepreneur has a negative score after discharge.

Only Albania collects information on the average time taken for an entrepreneur to get a full discharge and the average number of years afterwards that the entrepreneur has a negative score. The ministries of justice in both Serbia and Turkey monitor the size of their court case backlogs every year.

The assessed economies also sporadically monitor the implementation of bankruptcy and insolvency regulation. For example, the Albanian Bankruptcy Supervision Agency monitors bankruptcy administrators’ implementation of the bankruptcy laws and procedures. Montenegro conducts monitoring via the Judicial Council, which publishes yearly reports on its activities and results, including information on insolvency procedures.

Market imperfections prevent the orderly market exit of firms that are experiencing financial difficulties. To address this, economies need efficient insolvency regimes which are able to restructure viable firms and liquidate non-viable ones; but distinguishing between the two categories can be difficult. Insolvency regimes can be assessed through various indicators which help reveal the pros and cons of specific regimes. The following are the most widely used indicators:

World Bank Doing Business Report

The indicators in the World Bank Doing Business Report on resolving insolvency are based on a questionnaire. Respondents provide the estimates for a specific case study for the time the insolvency procedures would take and the cost borne by all parties. The report only refers to corporate insolvency and looks at outcome-based indicators such as the time and cost to close a business. It also assesses the strength of insolvency frameworks; however, it misses some of the policy design features that can be relevant for productivity. The indicators are based on four sub-indices: commencement of proceedings, management of debtors’ assets, reorganisation proceedings and a creditors’ rights index.

European Commission data

The European Commission data on the different features of insolvency frameworks are based on a survey conducted by the European association of insolvency professionals (INSOL Europe). The collected data are grouped into 12 dimensions and used to create an index of the efficiency of insolvency regimes. However, this indicator is limited in its coverage of both time and countries.

OECD insolvency indicators

The OECD insolvency indicators (see Annex 2.B) are based on a questionnaire that was designed to fill the gaps left by the World Bank and European Commission indicators. They focus on corporate and personal insolvency, taking into account international best practice and the existing literature. The OECD insolvency indicators also take into account various policy design features linked to inefficiencies in the market exit margin. They assess:

-

The treatment of failed entrepreneurs: measuring opportunities for a fresh start in terms of the time taken for discharge from bankruptcy and exemptions of entrepreneurs’ personal assets from insolvency proceedings.

-

Prevention and streamlining: summarising information on early warning mechanisms, pre-insolvency regimes and special simplified procedures for SMEs.

-

Restructuring tools: creditors’ ability to initiate restructuring.

-

Additional data: these include the role of courts, provisions distinguishing between honest and fraudulent bankruptcies, and the rights of employees.

The limitation of these indicators is their focus on ex-post efficiency incentives. They do not address trade-offs between credit availability and experimentation, or capture the quality of resolution and complementarities with other policies (e.g. judicial efficiency).

Sources: Adalet McGowan and Andrews (2016[26]), “Insolvency regimes and productivity growth: A framework for analysis”, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlv2jqhxgq6-en; OECD (2018[27]), Economic Policy Reforms 2018: Going for Growth Interim Report, https://doi.org/10.1787/18132723; World Bank (2018[12]), Doing Business 2019: Training for Reform, www.doingbusiness.org.

The way forward for survival and bankruptcy procedures

In order to enhance their legal framework on insolvency regimes, all WBT economies should:

-

Conduct entrepreneurial awareness campaigns about alternative forms of liquidation. Most of the economies have established out-of-court settlement options as a less expensive and faster way to liquidate than filing for bankruptcy. Settlements through mediation or concordats are less expensive for the state and impose a smaller burden on the judiciary system. However, according to private sector interviews, entrepreneurs know little about the options offered by alternative settlement procedures such as mediation or concordats – and sometimes are not even aware of their existence. Consequently, their use by enterprises remains limited. Promotion campaigns should highlight the benefits of the alternative liquidation methods in terms of cost, time and administrative procedures for enterprises. This could reduce the number of bankruptcy procedures, lessening the administrative burden on courts, and help to overcome the fear of failure among entrepreneurs.

-

Link out-of-court settlement systems to formal bankruptcy proceedings. The outcomes of out-of-court settlement procedures should automatically trigger formal bankruptcy proceedings if a full agreement between debtor and creditors is not reached. Put differently, if the majority of the creditors are strictly against the debtor’s proposed reorganisation plan, then this case should automatically go for liquidation, with an option for debt discharge and restart. In cases where there is partial support for the debtor’s proposed reorganisation plan (e.g. more than 50% of creditors), then the company should automatically proceed to reorganisation, with the chance of shortening the formal approval procedures.

-

Reduce the time and cost of bankruptcy by simplifying formal bankruptcy proceedings. The experiences of high-income OECD economies show that those with simple streamlined procedures have fewer appeals on court verdicts, the average proceedings are quicker, the average cost as a percentage of the bankrupt estate is less than 10% and the overall recovery rate is greater than 60% (OECD, 2018[27]; World Bank, 2018[28]). The frameworks in Finland, the United Kingdom and the United States have separate formal proceedings for liquidation and reorganisation, as well as a variety of preventive measures in place. Slovenia has developed a good process for simplifying the link between out-of-court settlements and formal bankruptcy proceedings (Box 2.6).

-

Maintain the administrative capacities of the bodies implementing the insolvency framework to keep up with framework changes in all WBT economies. For bankruptcy administrators, bankruptcy judges, appraisers and creditors’ associations, governments could consider formal training and limited-duration licensing of implementation bodies to ensure high-quality services. Constant monitoring and audits of their work should provide for higher professional standards and ensure that the quality of their services is maintained.

-

Step up efforts on monitoring and evaluation. Proper monitoring and evaluation leads to well-informed evidence-based policy making, helping to improve national credit registries. By enhancing co-ordination between the various public institutions, such as the ministry of justice and national statistical offices, governments could increase the number of relevant indicators collected and better evaluate the impact of insolvency policies.

Having joined the EU in 2004, Slovenia adopted a new insolvency law in 2007. However, this coincided with the financial crisis and the newly introduced regulations were not enough to deal with the high number of non-performing loans and failed entrepreneurs. The previous regulations were found to be one of the main causes of creditors’ low recovery rates (EBRD, 2014[29]). To improve the situation, the Slovenian government amended the insolvency law in 2013. The main changes included:

-

a new pre-insolvency restructuring procedure

-

mechanisms to facilitate restructuring.

The restructuring mechanisms included debt-equity swaps, giving priority to restructuring plans proposed by major creditors, and giving shareholders control of business operations. The new system is based on compulsory settlement, simplified compulsory settlement (solely for micro and small enterprises and individual entrepreneurs), pre-insolvency restructuring proceedings, and bankruptcy.

This reform quickly began to have a positive impact on Slovenia’s business environment. Within two years of its adoption, the percentage of companies using one or more of the procedures doubled, rising to almost 15% of cases in 2015. Furthermore, the recovery rate of secured creditors increased from 50.1 cents on the dollar in 2013 to 88.2 cents in 2015. The level of entrepreneurship and company formation also increased, having a clear impact on the SME ecosystem in general.

These changes also brought the Slovenian insolvency regime in line with best international practice, with the economy joining the trend of facilitating debt/equity swaps in order to conduct debt restructuring (IMF, 2015[30]).

Sources: EBRD (2014[29]), Commercial Laws of Slovenia: An Assessment by the EBRD, www.ebrd.com/documents/legal-reform/slovenia-country-law-assessment.pdf; IMF (2015[30]), “Republic of Slovenia: Selected issues”, www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2015/cr1542.pdf;https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2015/cr1542.pdf World Bank (2017[2]), Doing Business 2018: Reforming to Create Jobs, www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2018.

Promoting second chance (Sub-dimension 2.3)

According to a report published in 2011 by the European Commission, only 4-6% of bankruptcies are fraudulent (EC, 2011[13]).12 Despite this relatively low rate, public opinion usually associates business failure with fraud. This leaves many failed entrepreneurs feeling discouraged, suffering from social stigma and facing more obstacles to accessing finance than first-time starters, resulting in difficulties re-entering business and social life (EC, 2016[31]). A culture of fostering second chances for failed entrepreneurs is therefore crucial, since it has a positive impact on the number of entrepreneurs who are willing to start a business (Bezegova et al., 2014[32]).

A second chance policy provides an opportunity for failed honest entrepreneurs to start up businesses again. The policy core is based on the premise that the economy needs entrepreneurs who are willing to undertake a fresh start after failure, generating more jobs and growth. Promoting second chances for previously bankrupt entrepreneurs allows for their quick reintegration into society, and as the evidence shows, they can use their lessons learnt to create businesses which grow faster in terms of jobs and turnover (Bezegova et al., 2014[32]).

Another challenge is that discharge periods and sanctions for failed entrepreneurs are at times so lengthy or strict that bankruptcy effectively bars them from a quick second start, or sometimes even results in a “life sentence” away from business altogether. Even if an entrepreneur can obtain a quick discharge from debts, tailor-made support to help them start a new business is often lacking.

This section measures the extent to which governments promote second chances among failed entrepreneurs who want a fresh start. It investigates national strategies and information campaigns to promote a second chance, and civic consequences imposed on entrepreneurs during the period of bankruptcy.

The scores of the assessed economies show that promoting a second chance is still undeveloped in the region. Despite the lack of an institutional framework, the average score of close to 2 is directly related to the fact that governments do not sanction or impose civic consequences on failed honest entrepreneurs following bankruptcy (Table 2.6).

Formal bankruptcy discharge procedures exist in most economies

Bankruptcy discharge procedures are extremely important as they allow entrepreneurs to reintegrate into the economy. A discharge is a court order that releases the debtor from personal liabilities for certain specific debts covered by the legal framework. According to EU recommendations, discharge processes should be as quick as possible, ideally automatic and take no more than a year, in order to preserve the failed entrepreneur’s resources for a possible restart. Nevertheless, it should be noted that while all the EU Member States allow discharges, it is still not possible to complete legal bankruptcy proceedings within a year in most of them, or to be discharged from bankruptcy within three years. Similarly, most of the EU Member States offer honest entrepreneurs no possibility of an automatic discharge after liquidation (EC, 2018[33]).

In the WBT region, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro and Turkey have established formal discharge procedures for entrepreneurs. In Montenegro the law sets a maximum limit of three years to obtain a discharge. However, in North Macedonia there is no discharge from debt rules for natural persons13 and in Serbia entrepreneurs are liable for all obligations incurred in connection with the pursuit of the business.

Programmes to promote second chance among failed entrepreneurs are still lacking

In the WBT there is a region-wide lack of government-supported programmes both to promote a second chance among entrepreneurs who have gone bankrupt and to fight against the cultural stigma associated with bankruptcy. Information campaigns to raise awareness about second-chance opportunities are almost non-existent in the region, failing to promote second chances. Turkey is the only economy that mentions second chances clearly in its Turkish Entrepreneurship Strategy and Action Plan. The action plan aims to facilitate a second chance for bankrupt entrepreneurs; however, the strategy does not provide details on the specific measures to realise this target.

As for the rest of the assessed economies, although it is usually claimed by governments that their relevant insolvency laws are in line with the Small Business Act principles, their strategies or action plans do not make any direct or clear reference to promoting a second chance. For example, second chance policies in Serbia are briefly mentioned in the SME Development Strategy and Action Plan 2015-2020 in the section on “Relationship between the Strategy and the Act on small-sized enterprises” (Ministry of Economy, 2015[34]). Linked with the second principle of the Small Business Act,14 the strategy foresees the “improvement of the legal framework for the establishing, the operating and the closing of business entities” without providing any further details. The action plan planned one activity (a promotional campaign) for 2016, but it did not happen. The situation is similar in Montenegro, where the recently adapted Strategy for the Development of Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Montenegro 2018-2020 does not include the second principle of the Small Business Act in its strategic goals. The strategy highlights the importance of second chance policies, which are currently lacking. However, no concrete measures have so far been included in the strategy’s action plan.

The lack of specific programmes to promote second chance policies means that entrepreneurs are left alone to interpret insolvency laws and figure out their rights. In some cases, failed business owners can count on technical and emotional support provided by some sporadic initiatives organised by non-government organisations. Box 2.7 illustrates how sharing information and knowledge among entrepreneurs can give them a better chance to restart and use their entrepreneurial potential.

The lack of initiatives promoting second chances among previously bankrupt entrepreneurs is, however, not unique for the Western Balkans and Turkey. Even most EU Member States do not offer tailored support programmes for entrepreneurs looking to start afresh. Instead, governments often direct restarters to general support programmes, although these are less targeted. Annex 2.C summarises the second chance promotion programmes available in selected EU Member States.

The Fuckup Night movement was launched in 2012 in Mexico by a group of business colleagues who sought to bring stories of failure, rather than just success, into the limelight. They decided to organise an event at which guests would share their stories of business failure with the public. The initial idea captured significant attention and quickly spread to other cities and countries. To date, Fuckup Nights have active chapters in 93 countries and 304 cities, giving a platform to more than 3 000 stories, and more than 120 000 attendees just in 2018. These events have also taken place in the Western Balkan region, notably in Tirana in Albania, Banja Luka and Sarajevo in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Pristina in Kosovo, and Belgrade in Serbia.

The format of the events allows each speaker to deliver a 7-minute long presentation using 10 images. Speeches are followed by a question-and-answer session. At times, the list of speakers includes representatives of the local administration, ministers, artists and other individuals who wish to share their stories of business and professional failure.

In 2014, the Fuckup Nights initiative took a step further and founded the Failure Institute, focusing on the study of failure. The institute’s publications document cases of business failure and aim to support decision makers in making more informed decisions. Its flagship publication, the Global Failure Index (GFI), consists of 33 factors that cause businesses to close. While distinguishing between business failure and business closure, the GFI includes information on business profiles, entrepreneurs’ profiles, external support and closure details. Today, the publications describe 3 000 failed businesses.

The volume of collected data is still growing, together with the number of attendees at various Fuckup Nights. The platform allows entrepreneurs to share their valuable experience, put it into perspective and fight the stigma which is often associated with business failure.

Sources: Failure Institute (2018[35]), Global Failure Index, https://thefailureinstitute.com/global-failure-index/; Crunchbase (2018[36]), Fuckup Nights, www.crunchbase.com/organization/fuck-up-nights; Fuckup Nights (2018[37]), Fuckup Nights website, https://fuckupnights.com/.

Entrepreneurs still have obstacles to overcome before starting afresh

A second chance for entrepreneurs depends not only on cultural aspects of the economy, but also on the laws regulating the time needed to obtain a discharge (as explained in the previous section), as well as supporting legislation allowing honest entrepreneurs to make a new start. In other words, honest entrepreneurs who have failed need supportive regulations to allow them to make a fresh start.

All the economies have a forgiving approach towards entrepreneurs who have failed: none impose any civic consequences such as the loss of the right to vote or to hold elected office. However, the situation is different when it comes to economic consequences. As discussed in the previous section, in North Macedonia and Serbia the legal framework does not allow an automatic discharge from debt rules, forcing entrepreneurs to open a court case to obtain a discharge, and consequently creating obstacles to a fresh start. In the entity of the Republika Srpska in Bosnia and Herzegovina, natural or legal persons cannot establish a company or participate in the share of another company until they have settled their debts (e.g. social security contributions) in the register of fines, a measure primarily aimed at protecting workers’ rights. These regulatory obstacles and legislative gaps can harm failed entrepreneurs who wish to start again, and prevent them from using the expertise gained through their previous business endeavours.

The way forward for promoting second chance

In order to enhance second chance policies, governments in the region should:

-

Introduce policy measures granting a second chance for honest entrepreneurs. Governments need to clear the way for entrepreneurs who wish to restart. Introducing automatic debt discharge rules and setting a maximum time limit for the discharge process in the legal framework is essential to build effective second chance policies.

-

Make efforts to reduce the cultural stigma of failure. Despite the fact that there are no civic consequences for filing for bankruptcy in the WBT region, failed entrepreneurs still suffer from social stigma. To achieve a healthy entrepreneurial culture, the economies should recognise honest bankrupt entrepreneurs as a source of new enterprises and jobs. Therefore, a clear distinction has to be made between measures or regulations that apply to fraudulent bankruptcies and those that apply to honest ones. Such a distinction can be instrumental in changing society’s attitude towards debtors. However, amendments in the legal framework alone will not be enough: they should be complemented with initiatives promoting fresh starts and a culture that is receptive and tolerant of failures. To that end, workshops and seminars aimed at sharing the lessons learned from previously bankrupt entrepreneurs can break the stigma surrounding bankruptcy and failure. A notable example is the work of the French organisation, 60 000 Rebonds (Box 2.8).

60 000 Rebonds is a French non-profit association that aims to help failed entrepreneurs to “rebound professionally”. Philippe Rambaud, a previously failed entrepreneur himself, founded the association in 2012. Having undergone liquidation, and experienced financial and professional trauma, Rambaud decided to act in order to help other post-liquidation entrepreneurs.

The association offers free support services on a voluntary basis, which can be initiated up to 24 months after the company’s liquidation procedure. The support is available to all entrepreneurs, regardless of the sector they used to work in, who show a substantial determination to rebound, and have the capacity to engage in a process of personal and professional growth. The support programme consists of 3 main levers:

-

Executive coaching

-

Mentoring

-

Co-development workshops

After passing initial interview and being enrolled into the programme, the entrepreneur receives seven coaching sessions. These sessions help the entrepreneur to regain self-confidence, make the difference between personal talents/vulnerabilities vs venture failure, accept the company’s liquidation and find new professional perspectives. At the same time, the entrepreneur is assigned a mentor: an entrepreneur/manager who helps the participant to rebound by helping to determine the direction of new professional engagements and co-ordinating exchanges with experts throughout the process. Participants can also count on the support of co-development workshop, made up of volunteers who help develop new professional projects. Additionally, participants can take part in conference workshops to gain new competences and develop new skills. Finally, the association co-ordinates a network, which sets up exchanges between entrepreneurs who share similar experiences.

The organisation currently operates in 2 French cities and helps around 600 entrepreneurs on an annual basis, free of charge. Based on the beneficiaries’ feedback, the programme is considered to be effective in helping entrepreneurs regain confidence, and grow into more professional leaders in order to rebound and reintegrate into the market.

Source: 60 000 Rebonds (2018[38]), 60 000 Rebonds website, https://60000rebonds.com/.

Conclusions

Overall, all the economies have taken steps to strengthen their legal frameworks for insolvency. All the insolvency legislation covers the legal framework on secured transactions and provides alternative methods of dispute settlement between debtors and creditors. The region is making slow but steady progress in reducing the time and cost of insolvency procedures.

However, the assessment also found that preventive measures and second chance mechanisms in the WBT region are still underdeveloped. There is a region-wide lack of institutional measures to prevent the bankruptcy of entrepreneurs, through mechanisms such as early warning systems. The lack of monitoring and evaluation of bankruptcy proceedings also remains an ongoing challenge. Addressing the recommendations put forward in this chapter will help governments increase their institutional capacities as well as the entrepreneurial ecosystem in general.

References

[38] 60 000 Rebonds (2018), 60 000 Rebonds website, https://60000rebonds.com/.

[26] Adalet McGowan, M. and D. Andrews (2016), “Insolvency regimes and productivity growth: A framework for analysis”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1309, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlv2jqhxgq6-en.

[7] Adalet McGowan, M., D. Andrews and V. Millot (2017), “Insolvency regimes, zombie firms and capital reallocation”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1399, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5a16beda-en.

[39] Adalet McGowan, M., D. Andrews and V. Millot (2017), “The walking dead? Zombie firms and productivity performance in OECD countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1372, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/180d80ad-en.

[24] Babić, N. and J. Branović (2016), Insolvency / Restructuring in Montenegro, Schoenherr website, https://www.schoenherr.eu/publications/publication-detail/insolvency-restructuring-in-montenegro-1/.

[19] BDC (2018), Business Development Bank, http://www.bdc.ca.

[32] Bezegova, E. et al. (2014), Bankruptcy and Second Chance for Honest Bankrupt Entrepreneurs, Publications Office of the European Union, https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/24f281f2-9b0a-44d0-8681-af8bd7657747.

[5] Cardon, M. (2010), “Misfortunes or mistakes? Cultural sensemaking of entrepreneurial failure”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 26/1, pp. 79–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.06.004.

[1] Cirmizi, E., L. Klapper and M. Uttamchand (2011), “The challenges of bankruptcy reform”, World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 27/2, pp. 185-203, https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1093/wbro/lkr012.

[18] CNCC (2018), La Prévention, Compagnie Nationale des Commissaires aux Comptes, https://www.cncc.fr/prevention.html.

[36] Crunchbase (2018), Fuckup Nights, Crunchbase website, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/fuck-up-nights.

[20] Early Warning Europe (2018), Early Warning Europe website, http://www.earlywarningeurope.eu.

[29] EBRD (2014), Commercial Laws of Slovenia: An Assessment by the EBRD, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, https://www.ebrd.com/documents/legal-reform/slovenia-country-law-assessment.pdf.

[33] EC (2018), 2018 SBA Fact Sheet and Scoreboard, European Commission, Luxembourg.

[15] EC (2017), 2017 SBA Fact Sheet, European Commission, Luxembourg, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/29489/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

[31] EC (2016), Proposal for a Directive of the European Parlaiment and of the Council, European Commission, Strasbourg, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=SWD:2016:0357:FIN:EN:PDF.

[25] EC (2014), Comission Recommendation of 12 March 2014 on a New Approach to Business Failure and Insolvency, European Commission, Brussels, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014H0135&from=EN.

[13] EC (2011), A Second Chance for Entrepreneurs: Prevention of Bankruptcy, Simplification of Bankruptcy Procedures and Support for a Fresh Start, EC Enterprise and Industry, European Commission, Luxembourg, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/10451/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

[35] Failure Institute (2018), Global Failure Index, Failure Institute website, https://thefailureinstitute.com/global-failure-index/.

[37] Fuckup Nights (2018), Fuckup Nights website, https://fuckupnights.com/.

[11] GEM (2018), Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Attitudes, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor website, https://www.gemconsortium.org/data/key-aps (accessed on 1 September 2018).

[21] Hart, O. (2000), “Different approaches to bankruptcy”, NBER Working Paper, No. 7921, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, https://www.nber.org/papers/w7921.

[3] Hayward, M., D. Shepherd and D. Griffin (2006), “A hubris theory of entrepreneurship”, Management Science, Vol. 52, pp. 160-172, https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0483.

[30] IMF (2015), “Republic of Slovenia: Selected issues”, IMF Country Report, No. 15/42, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2015/cr1542.pdf.

[4] Liao, J., H. Welsch and C. Moutray (2008), “Start-up resources and entrepreneurial discontinuance: The case of nascent entrepreneurs 1”, Journal of Small Business Strategy, Vol. 19/2, p. 1, https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-1680693201/start-up-resources-and-entrepreneurial-discontinuance.

[14] Ministry of Economy (2017), Project: Strengthening the Administrative Capacities for the Implementation of the Legal Framework for Bankruptcy and Voluntary Liquidation of Companies, Ministry of Economy, Republic of North Macedonia, http://www.economy.gov.mk/page/strengthening-administrative-capacities.

[34] Ministry of Economy (2015), SME Development Strategy & Action Plan 2015-2020, Ministry of Economy, Republic of Serbia, http://www.privreda.gov.rs/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Strategija-I-Plan_eng_poslednje.pdf.

[17] OCED (2017), Observatoire Consulaire des Entreprises en Difficultés, https://www.oced.cci-paris-idf.fr/ (accessed on 1 November 2018).

[27] OECD (2018), Economic Policy Reforms 2018: Going for Growth Interim Report, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/18132723.

[10] RCC (2017), Balkan Barometre 2017: Business Opinion Survey, Regional Cooperation Council.

[16] Service-Public-Pro (2018), Alertes pour la prévention des difficultés des entreprises, Service-Public-Pro website, https://www.service-public.fr/professionnels-entreprises/vosdroits/F22321.

[6] Stam, E. et al. (2008), “Renascent entrepreneurship”, Journal of Evolutionary Economics, Vol. 18, pp. 493-507, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-008-0095-7.

[8] Ucbasaran, D., P. Westhead and M. Wright (2011), “Why serial entrepreneurs don’t learn from failure”, Harvard Business Review 04, https://hbr.org/2011/04/why-serial-entrepreneurs-dont-learn-from-failure.

[23] UNCITRAL (2013), UNCITRAL Legislative Guide on Insolvency Law, United Nations Commission on International Trade Law, https://uncitral.un.org/en/texts/insolvency/legislativeguides/insolvency_law.

[9] World Bank (2018), Doing Business 2019: Training for Reform, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30438.

[12] World Bank (2018), Doing Business website, World Bank, http://www.doingbusiness.org.

[28] World Bank (2018), Resolving Insolvency: Good Practices, World Bank Doing Business website, http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploretopics/resolving-insolvency/good-practices (accessed on 27 July 2018).

[22] World Bank (2018), Resolving Insolvency: Why it Matters, World Bank Doing Business website, http://www.doingbusiness.org/en/data/exploretopics/resolving-insolvency/why-matters.

[2] World Bank (2017), Doing Business 2018: Reforming to Create Jobs, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, http://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2018.