1. Executive Summary

1. Digital transformation spurs innovation, generates efficiencies, and improves services while boosting more inclusive and sustainable growth and enhancing well-being. At the same time, the breadth and speed of this change introduces challenges in many policy areas, including taxation. Reforming the international tax system to address the tax challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy has therefore been a priority of the international community for several years, with commitments to deliver a consensus-based solution by the end of 2020.

2. These tax challenges were first identified as one of the main areas of focus of the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project, leading to the 2015 BEPS Action 1 Report (the Action 1 Report) (OECD, 2015[1]). The Action 1 Report found that the whole economy was digitalising and, as a result, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to ring-fence the digital economy. In March 2018, the Inclusive Framework, working through its Task Force on the Digital Economy (TFDE), issued Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018 (the Interim Report) (OECD, 2018[2]) which recognised the need for a global solution.

3. Since then, the 137 members of the Inclusive Framework have worked on a global solution based on a two pillar approach (OECD, 2015[1]). Under the second pillar, the Inclusive Framework agreed to explore an approach that is focused on the remaining BEPS challenges and proposes a systematic solution designed to ensure that all internationally operating businesses pay a minimum level of tax. In so doing, it helps to address the remaining BEPS challenges linked to the digitalising economy, where the relative importance of intangible assets as profit drivers makes highly digitalised business often ideally placed to avail themselves of profit shifting planning structures. Pillar Two leaves jurisdictions free to determine their own tax system, including whether they have a corporate income tax and where they set their tax rates, but also considers the right of other jurisdictions to apply the rules contained in this report where income is taxed at an effective rate below a minimum rate.

4. Consistent with the Policy Note Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digitalisation of the Economy (OECD/G20, 2019[3]), approved on 23 January 2019 and the Programme of Work (PoW) (OECD, 2019[4]), approved on 28-29 May, 2019, Members of the Inclusive Framework agree that any rules developed under this Pillar should not result in taxation where there is no economic profit nor should they result in double taxation. Mindful of limiting compliance and administrative burdens, Inclusive Framework Members further agree to make any rules as simple as the tax policy context permits, including through the exploration of simplification measures.

5. Following the adoption of the Programme of Work (OECD, 2019[4]) in May 2019, the Inclusive Framework worked on developing the different aspects of Pillar Two. A public consultation was held on 9 December 2019 (OECD, 2019[5]) which received over 150 written submissions, running to over 1,300 pages submitted by a wide range of businesses, industry groups, law and accounting practitioners, and non-governmental organisations, which provided critical input into the design of many of the aspects of Pillar Two. In January the Inclusive Framework issued a progress report on the status of the technical work. Since January, and in spite of the outbreak of COVID-19, all members have progressed the work and the engagement with stakeholders continued through digital channels including through the maintenance of digital contact groups set up by Business at OECD (BIAC).

6. This is a Report on the blueprint for Pillar Two (the “Blueprint”). It identifies technical design components of Pillar Two. It also identifies those areas linked to implementation and simplification, which would benefit from further stakeholder input, and where further technical work is required prior to finalisation. The finalisation of Pillar Two also requires political agreement on key design features of the subject to tax rule and the GloBE rules including carve-outs, blending, rule order and tax rates where, at present, diverging views continue to exist.

7. The remainder of this Section sets out the overall design consideration, before focusing on administrative and compliance considerations that were important in the design of Pillar Two. It then discusses the co-existence of the United States’ Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) regime, before providing a chapter-by chapter summary complemented by a flow chart.

8. Pillar Two addresses remaining BEPS challenges and is designed to ensure that large internationally operating businesses pay a minimum level of tax regardless of where they are headquartered or the jurisdictions they operate in. It does so via a number of interlocking rules that seek to (i) ensure minimum taxation while avoiding double taxation or taxation where there is no economic profit, (ii) cope with different tax system designs by jurisdictions as well as different operating models by businesses, (iii) ensure transparency and a level playing field, and (iv) minimise administrative and compliance costs.

9. The principal mechanism to achieve this outcome is the income inclusion rule (IIR) together with the undertaxed payments rule (UTPR) acting as a backstop. The operation of the IIR is, in some respects, based on traditional controlled foreign company (CFC) rule principles and triggers an inclusion at the level of the shareholder where the income of a controlled foreign entity is taxed at below the effective minimum tax rate.1 It is complemented by a switch-over rule (SOR) that removes treaty obstacles from its application to certain branch structures and applies where an income tax treaty otherwise obligates a contracting state to use the exemption method.

10. The UTPR is a secondary rule and only applies where a Constituent Entity is not already subject to an IIR. The UTPR is nevertheless a key part of the rule set as it serves as back-stop to the IIR, ensures a level playing field and addresses inversion risks that might otherwise arise.

11. The Subject to Tax Rule (STTR) complements these rules. It acknowledges that denying treaty benefits for certain deductible intra-group payments made to jurisdictions where those payments are subject to no or low rates of nominal taxation may help source countries to protect their tax base, notably for countries with lower administrative capacities. To ensure tax certainty and avoid double taxation Pillar Two also addresses questions of implementation and effective rule coordination.

Income inclusion rule and undertaxed payments rule (the “GloBE rules”)

12. The IIR and the UTPR use the same rules to determine scope and the level of effective taxation. They apply to MNE Groups and their Constituent Entities within the consolidated group as determined under applicable financial accounting standards. They only apply to businesses that meet or exceed a EUR 750 million annual gross revenue threshold.2 This creates synergies with the current BEPS Action 13 Country by Country Reporting (CbCR) rules, thereby reducing compliance costs. It also avoids adverse impacts on SME’s while preserving the impact of the rules with in scope MNE Groups still earning over 90% of global corporate revenues.

13. The rules further exclude certain parent entities including investment and pension funds, governmental entities such as sovereign wealth funds and international and non-profit bodies, which typically benefit from an exclusion or exemption from tax under applicable domestic tax law. Special rules may apply to Associates, joint ventures and so called “orphan entities” that are not part of the consolidated group.

14. Both the IIR and the UTPR use a common tax base. The determination of the base starts with the financial accounts prepared under the accounting standard used by the parent of the MNE Group to prepare its consolidated financial statements. This must be IFRS or another acceptable accounting standard. The use of financial accounts as a common basis ensures a level playing field for both jurisdictions and MNEs, enhances transparency and leverages off existing systems thereby minimising compliance cost. Certain adjustments are then made to the financial accounts to eliminate specific items of income from the tax base, such as intragroup dividends and to incorporate certain expenses, such as tax deductible stock based compensation. This is necessary where the outcomes of the financial accounting rules would otherwise distort the tax policy objectives of Pillar Two.

15. The IIR and the UTPR also use a common definition of taxes. The definition of taxes, referred to as “covered taxes” is derived from the definition of taxes used for statistical purposes by many international organisations including the OECD, EU, IMF, World Bank and the UN. The definition is deliberately kept broad to avoid legalistic distinctions and accommodate different tax systems provided they substantively impose taxes on an entity’s income or profits.

16. The effective tax rate (ETR) is determined by applying the tax base and covered taxes on a jurisdictional basis. This requires an assignment of the income and taxes among the jurisdictions in which the MNE operates and to which it pays taxes. The GloBE tax computation calculation also includes two important additional adjustments; a mechanism to mitigate the impact of volatility in the ETR from one period to the next and a formulaic substance carve-out.

17. The mechanism to address volatility is based on the principle that Pillar Two should not impose tax where the low ETR is simply a result of timing differences in the recognition of income or the imposition of taxes. The GloBE rules therefore allow an MNE to carry-over losses incurred or excess taxes paid in prior periods into a subsequent period in order to smooth-out any potential volatility arising from such timing differences.

18. The formulaic substance carve-out excludes a fixed return for substantive activities within a jurisdiction from the scope of the GloBE rules. Excluding a fixed return from substantive activities focuses GloBE on “excess income”, such as intangible-related income, which is most susceptible to BEPS challenges.

19. If an MNE’s jurisdictional ETR is below the agreed minimum rate, the MNE will be liable for an incremental amount of tax that is sufficient to bring the total amount of tax on the excess profits up to the minimum rate. The ETR calculation therefore operates both as a trigger for the imposition of the tax liability and as a measure of the amount of top-up tax imposed under the rules. This design ensures a level playing field as all MNE’s pay a minimum level of tax in each jurisdiction in which they operate while the top up mechanism coupled with the common base makes sure that they face the same level of top-up tax irrespective of where they are based. The amount of top up tax is collected either by application of the IIR, or - where no IIR applies- by the application of the UTPR.

Subject to Tax Rule

20. The Subject to Tax Rule (STTR) complements these rules. It is a treaty-based rule that specifically targets risks to source countries posed by BEPS structures relating to intragroup3 payments that take advantage of low nominal rates of taxation in the other contracting jurisdiction (that is, the jurisdiction of the payee). It allows the source jurisdiction to impose additional taxation on certain covered payments up to the agreed minimum rate. Any top up tax imposed under the STTR will be taken into account in determining the ETR for purposes of the IIR and the UTPR.

Implementation

21. While the IIR and the UTPR do not require changes to bilateral treaties and can be implemented by way of changes to domestic law,4 both the STTR and the SOR can only be implemented through changes to existing bilateral tax treaties. These could be implemented through bilateral negotiations and amendments to individual treaties or as part of a multilateral convention. Alternatively the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (the MLI) (OECD, 2016[6]), emerging from BEPS Action 15, may offer a model for a coordinated and efficient approach to introducing these changes.

Rule co-ordination and next steps

22. As a next step and to ensure rule co-ordination and increase tax certainty the Inclusive Framework on BEPS will develop model legislation and guidance, develop a multilateral review process and explore the use of a multilateral convention, which could include the key aspects of Pillar Two. Dispute prevention and resolution processes can build on the existing infrastructure, but new provisions could also be included in a multilateral convention.

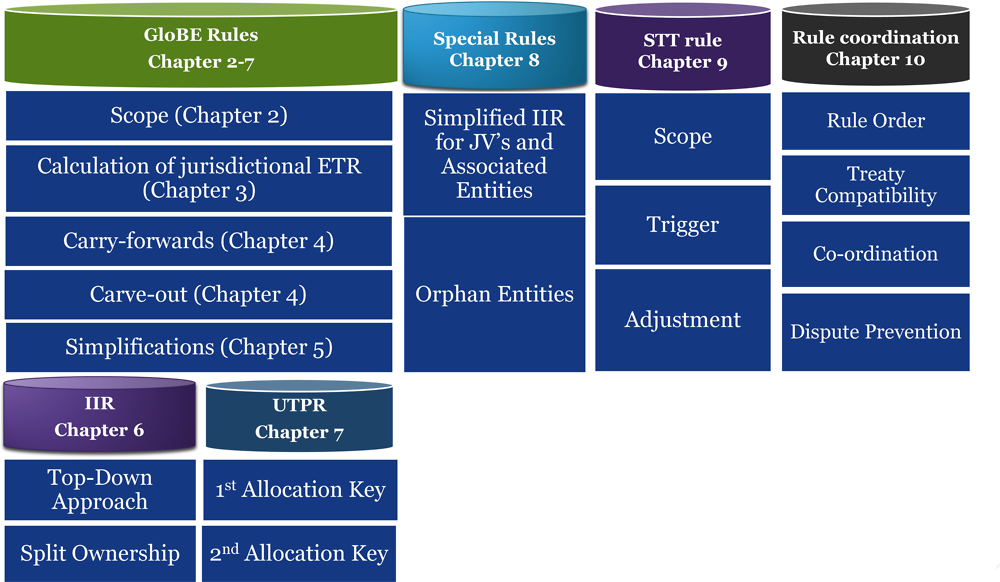

23. The graphic below shows the different components of Pillar Two and identifies the chapter where each of these components is discussed.

24. Within the context of the tax policy objectives of Pillar Two the design of each feature has been developed with the objective of minimising cost and resources for both tax authorities and taxpayers in applying and administering the Pillar Two rules. This has informed a number of design choices including the following:

Use of accounting consolidation rules for determining scope. While from a tax policy perspective there could have been reason to go beyond the consolidated group definition, to minimise cost and complexity the Pillar Two design stays with this definition and addresses particular risk areas through targeted rules only.

Reliance on Country-by-Country reporting (CbCR) thresholds and definitions. To limit compliance costs, maximise synergies, avoid adverse impacts on SME’s, while preserving the overall impact of the rules, the Pillar Two design leverages off the CbCR concepts and definitions and excludes MNE’s below the EUR 750 million consolidated gross revenue threshold.

List of excluded entities. To provide certainty and translate the policy intent, the Pillar Two design includes a list of expressly excluded entities, including those that may, in certain circumstances, already be excluded under the operation of the consolidation rules.

Use of parent financial accounting standards, no book-to-book and limited book-to-tax adjustments. The reliance on accounting information avoids the cost and complexity of having to re-compute the income and profits of each foreign group member in accordance with domestic tax accounting rules, which in practise is not something MNEs are often required to do to even where they are subject to CFC rules. In particular, a requirement to re-compute using domestic tax accounting in connection with the application of the UTPR would have resulted in disproportionate compliance burdens. Furthermore, the Pillar Two design accepts a range of accounting standards without requiring book to book adjustments, for instance between IFRS and US GAAP. The use of the accounting standards at the parent level – rather than local entity level – further reduces compliance cost. Finally, book to tax adjustments have been kept at a minimum in part to maintain the benefit of simplicity in using financial accounting standards in the first place.

Reliance on entity level financial information. The Pillar Two design accepts that entity level financial information that is used in the preparation of the parent’s financial accounts may not be in perfect accord with the parent’s accounting standard, but considering cost and benefits, it allows MNE’s to rely on such entity level information subject to certain conditions.

Timing differences simplifications. The rules provide for a simplified mechanism to address timing differences that applies on a jurisdictional basis and includes mechanisms for calculating pre-regime losses and excess taxes.

Rule order. The Pillar Two design has the IIR as the primary rule with the UTPR acting as a backstop. Both rules use the same computational rules for determining low taxed income, but the primacy of the IIR is largely driven by simplicity and lower compliance costs, including the ease of obtaining the necessary income and tax information required to make an ETR determination; the fact that the IIR will generally require only one adjustment to be made by a single taxpayer and the availability of mechanisms to avoid the risk of double taxation. Equally, the general decision to use a top-down rather than a bottom-up approach for the use of the IIR in connection with multi-tier MNE Groups is driven in significant part by compliance and simplicity considerations. The top-down approach will limit the number of jurisdictions applying the IIR thereby reducing the need for co-ordination and, by extension, complexity, administrative burden, and the risk of double taxation under the rules.

Subject to Tax Rule using a nominal tax rate test. The Subject to Tax Rule is limited to certain categories of payments made between members of a controlled group and is based on a nominal tax rate test, thereby avoiding the conceptual and administrative challenges of using an effective tax rate test.

Bright line and mechanical rule design. Wherever possible, within the context of the tax policy objectives, Pillar Two uses bright line rules (e.g. on scope and for the determination of the tax base including any permanent adjustments) and more mechanical, formulaic approaches (e.g. the design of a formulaic substance based carve-out and in the mechanics for allocating top-up tax under the IIR and UTPR) which should make compliance easier and avoid the types of disputes that often result from more subjective rules with significant reliance on facts and circumstance tests.

Further simplification options in particular in light of jurisdictional blending. During the December 2019 Public Consultation (OECD, 2019[5]), many MNEs stressed that simplification measures are needed to reduce the complexity and administrative burden associated with complying with the GloBE rules, particularly in the context of jurisdictional blending. Several submissions pointed out that large MNEs often operate in more than 100 jurisdictions and would be required to undertake the same number of ETR calculations under a jurisdictional blending approach. Other submissions expressed concern that, under jurisdictional blending, it would be necessary to compute the ETR in jurisdictions that are likely to be above the agreed minimum rate year-after-year, given the base and tax rate in these jurisdictions. These inputs informed a number of the design features already discussed above, but also led to the exploration of several further simplification measures, as set out in Chapter 5 of the Report. These simplification measures would benefit from further public consultations with stakeholders and business in particular and therefore no decision has yet been taken on which, if any, of these simplification measures to incorporate into the final design of the rules.

25. The United States enacted the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) regime in 2017 as part of a substantial reform of the US international tax rules. The GILTI regime, which draws on elements of the BEPS Action 3 Report, provides for a minimum level of tax on the foreign income of an MNE Group. While the GILTI and GloBE rules as described in this Blueprint have a similar purpose and overlapping scope, the design of GILTI differs from GloBE in a number of important respects.

26. While GILTI results largely, but not completely, in a global blending of foreign income and taxes, in a number of other respects, the GloBE rules, as described in this Blueprint, would be more permissive than GILTI, depending also on their final design. These include the carry-forward of losses and excess taxes, a broader definition of covered taxes and a carve-out based on a broader range of tangible assets and payroll. Furthermore, GILTI applies without threshold limitations and incorporates expense allocation rules in the calculation of foreign tax credits which can result in effective rates of taxation above the minimum rate. Finally, the GILTI effective rate is currently set at 13.125% and will increase to 16.4% in 2026.

27. Given the pre-existing nature of the GILTI regime and its legislative intent there are reasons for treating GILTI as a qualified income inclusion rule for purposes of the GloBE rules provided that the coexistence achieves reasonably equivalent effects.. This treatment would need to be reviewed if subsequent legislation or regulations in the US would have the effect of materially narrowing the GILTI tax base or reducing the legislated rate of tax. The Inclusive Framework recognises that an agreement on the co-existence of the GILTI and the GloBE would need to be part of the political agreement on Pillar Two.

28. At a technical level further consideration will be given to how the interactions between the GILTI and the GloBE rules would be coordinated. That includes the coordination with the application of the GILTI to US intermediate parent companies of foreign groups headquartered in countries that apply an IIR. Moreover, considering the role of the undertaxed payments rule as a back-stop to the IIR, the Inclusive Framework on BEPS strongly encourages the United States to limit the operation of the Base Erosion and Anti-abuse Tax (BEAT) in respect of payments to entities that are subject to the IIR.

29. This Pillar Two report consists of ten chapters that set out the overall design of the rules and includes an Annex with examples illustrating the operation of the rules.

30. Chapter 1 is this executive summary and introduction.

31. Chapter 2 contains the rules that determine the scope of the GloBE rules and includes the relevant definitions for in scope groups and Constituent Entities, as well as excluded entities. It also explains the application and computation of the consolidated revenue threshold.

32. Chapter 3 covers the rules and explanations relating to the calculation of the ETR and top-up tax under the GloBE rules. The starting point for applying the GloBE rules is the consolidated financial statements prepared by the MNE Group. A limited number of adjustments are then made to the financial accounts to add or eliminate certain items in order to arrive at the GloBE tax base. The Chapter then defines the covered taxes that can be taken into account in determining the ETR on a jurisdictional basis.

33. Chapter 4 sets out a number of adjustments that may be made to the top-up tax calculation either through the carry-over of losses or excess taxes from other periods or through the application of a formulaic substance based carve-out. The carry-forward adjustments are intended to ensure that Pillar Two does not result in the imposition of additional tax where the low ETR is simply a result of differences in the timing for recognition of income or the imposition of taxes while the formulaic substance-based carve-out is intended to exclude a fixed return for substantive activities within a jurisdiction from the scope of the GloBE rules.

34. Chapter 5 explores a number of simplification measures designed to reduce the compliance burden in particular from the use of a jurisdictional ETR calculation. As noted in that chapter these simplifications would benefit from further public consultations with business in particular and therefore no decision has yet been taken on which, if any, of these simplification measures to incorporate into the final design of the rules.

35. Chapter 6 describes the operation of the IIR including how the IIR is applied in the context of a multi-tiered ownership structure, where Pillar Two uses a top down approach except in cases where the ownership is split with a minority holder outside the group. In the latter case the split-ownership rules require the intermediate parent entity to apply the income inclusion rule to the controlled subsidiaries of the sub-group. This chapter also explains the need for a treaty based switch over rule that would allow a jurisdiction to override the exemption method to the extent necessary to apply the IIR to the profits of a permanent establishment.

36. Chapter 7 contains a detailed discussion of the UTPR. The UTPR only applies to those Constituent Entities in the MNE Group that are not controlled by an entity further up the chain that applies an IIR. Where the UTPR applies top-up tax is allocated proportionately among Constituent Entities applying UTPR in a co-ordinated way first to those entities making direct payments to the low-tax Constituent Entity and then amongst all entities in the group that have net intra-group expenditure.

37. Chapter 8 discusses two special rules, one dealing with Associates and joint ventures and another dealing with so-called “orphan entities.” The first rule applies a simplified IIR to the income of an MNE Group attributable to ownership interests in entities or arrangements that are reported under the equity method. The second rule is designed to extend the application of the UTPR to “orphan” entities or arrangements that could otherwise be used to extract profit from the MNE Group for the benefit of the controlling shareholders, giving rise to a BEPS risk.

38. Chapter 9 addresses the subject to tax rule. It sets the framework for a development of a treaty-based rule that specifically targets risks to source countries posed by BEPS structures relating to intragroup payments that take advantage of low or nominal rates of taxation in the other contracting jurisdiction (that is, the jurisdiction of the payee). The effect of the rule will be to allow the payer jurisdiction to apply a top-up tax to bring the tax on the payment up to an agreed minimum rate.

39. Chapter 10 deals with implementation and rule co-ordination. This chapter is forward looking and explains how the Inclusive Framework will ensure rule co-ordination and increase tax certainty including through the development of model legislation and guidance, a multilateral review process and the exploration of a multilateral convention, which could also include new provision on dispute prevention and resolution.

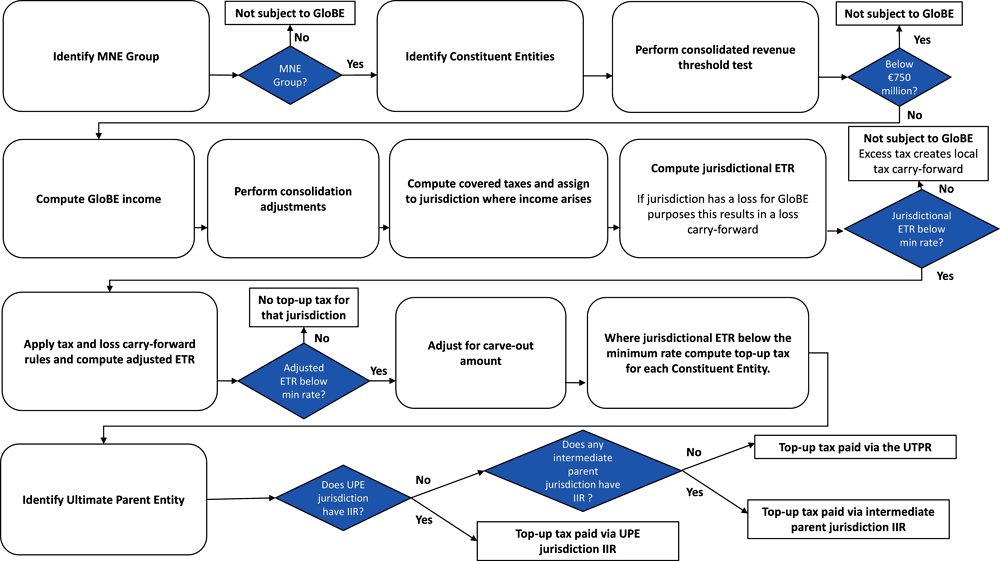

40. The flow diagram below is intended to provide a high-level overview of the process steps for applying the GloBE rules to wholly-owned Constituent Entities of an MNE Group.

References

[5] OECD (2019), Global Anti-Base Erosion Proposal (“GloBE”) - Pillar Two, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/public-consultation-document-global-anti-base-erosion-proposal-pillar-two.pdf.pdf.

[4] OECD (2019), Programme of Work to Develop a Consensus Solution to the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy, OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/programme-of-work-to-develop-a-consensus-solution-to-the-tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy.pdf.

[2] OECD (2018), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293083-en.

[6] OECD (2016), Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/treaties/multilateral-convention-to-implement-tax-treaty-related-measures-to-prevent-BEPS.pdf.

[1] OECD (2015), Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, Action 1 - 2015 Final Report, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264241046-en.

[3] OECD/G20 (2019), Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digitalisation of the Economy – Policy Note, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/policy-note-beps-inclusive-framework-addressing-tax-challenges-digitalisation.pdf.

Notes

← 1. Although similar in operation, the IIR and CFC rules can co-exist because they have different policy objectives.

← 2. For a further discussion of the revenue threshold see Section 2.4 and 10.3 below.

← 3. As discussed in Section 9.1, the STTR may not in all instances be limited to intra-group payments.

← 4. See Section 10.5.3 on the consideration of a multilateral convention to ensure co-ordination of the IIR and UTPR.